1. Introduction

Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging (qMRI) is essential for accurately evaluating tissue properties and detecting early pathological changes across various anatomical regions before the development of morphological changes [

1,

2,

3]. Traditional qualitative MRI imaging, used in clinical practice, often lacks the sensitivity and specificity required for such early detection [

4]. qMRI overcomes this problem by acquiring multi-contrast images with controlled variations in MRI pulse sequence parameters [

5]. It enables the estimation of tissue relaxation properties, and the non-linear least squares (NLS) methods are usually the reference approaches to compute quantitative parameters [

6,

7,

8].

NLS methods are fundamental tools in inverse problems and statistical estimations, particularly in parameter fitting. These methods extend linear regression to handle problems where the variables have a non-linear relationship. They aim to minimize the sum of squared differences between observed and predicted values [

9,

10]. Theoretical support and soundness of NLS methods such as Jacobian-based approaches (like Gauss-Newton and Levenberg-Marquardt) and derivative-free algorithms (like Nelder-Mead) are strong, making them the preferred choice in multiple applications, but they are generally slow for large multi-dimensional datasets, among other problems [

11,

12,

13].

Gauss-Newton methods are efficient for those problems where models are nearly linear. To achieve better convergence speed, it utilizes the Jacobian matrix to approximate the Hessian [

9,

10]. The Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm refines the Gauss-Newton method by using the concept of a damping factor. Thus, it enhances convergence stability and performance in more complex non-linear problems when the Hessian is ill-conditioned [

11,

12]. Powell’s Dog Leg method integrates Gauss-Newton and the steepest descent directions to effectively manage substantial curvature in the error surface. In contrast, hybrid approaches that combine the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm with Quasi-Newton methods use adaptive step sizes and approximate Hessians to achieve robustness and efficiency in large-scale optimization problems [

9,

10,

11]. Approximation-based versions of these methods, (i.e., adaptations of the Levenberg–Marquardt and Dog Leg approaches) replace exact derivative computations with approximations [

12,

13]. This substitution reduces computational complexity and improves efficiency [

14,

15]. Trust Region Conjugate Gradient (TRCG) [

9,

45] combines trust-region methods with iterative inversion of Hessian or its approximation, being a good choice for parameter fitting. Therefore, these approximation-based methods may perform better on high-dimensional and large-scale optimization problems.

However, these methods come with significant computational demands and the risk of converging to local minima, especially in complex parameter spaces. The accuracy of these methods is significantly dependent on the quality of initial parameter estimates. Thus, poor initialization potentially results in suboptimal solutions.

From the literature, it is found that NLS methods are effective for T1ρ mapping but are hampered by slow computational speeds. As a result, NLS is typically applied only to specific regions of interest (ROIs), such as cartilage voxels in the knee joint. NLS can also be unstable when dealing with multi-component relaxation. To address these issues, researchers have developed variants like non-negative least squares (NNLS) [

16,

17,

18] and regularized NLS (RNLS) [

18,

19].

NNLS adds a non-negativity constraint to stabilize estimations, ensuring real-valued, monotonically decreasing relaxations [

16,

17,

18]. RNLS extends NLS by incorporating regularization penalties to improve stability and accommodate independent (in-voxel) or multi-voxel (spatial) regularization functions [

18,

19]. Thus, RNLS is more suitable for recovering all voxels in imaging applications. Improved stability makes RNLS somewhat faster than NLS, but it still requires many iterations.

1.1. Research Motivation

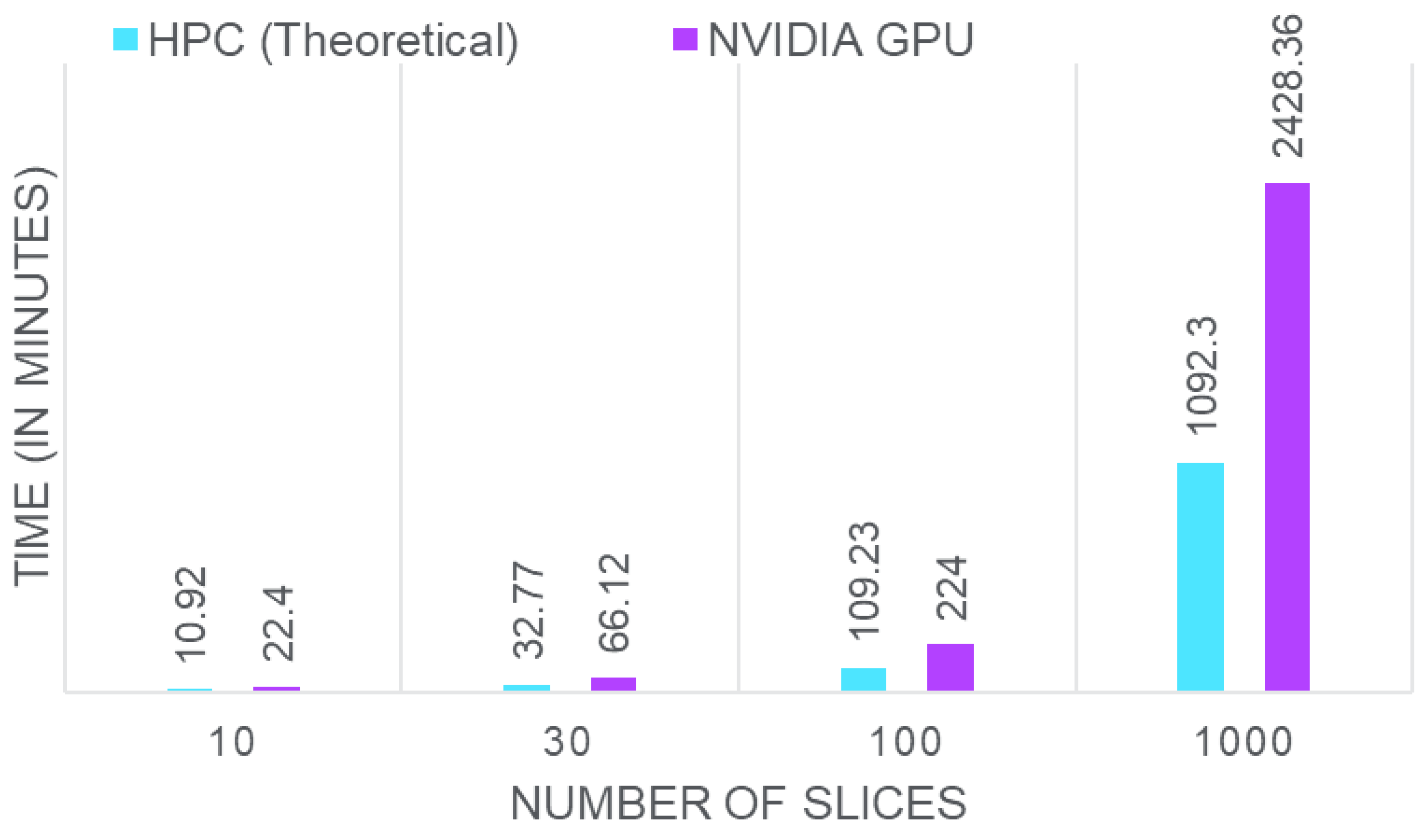

Considering an MR image slice of size 256 × 256 = 65,536 voxels, NLS fitting requires approximately 1 millisecond per voxel on high-performance computing (HPC) systems. Thus, fitting all 65,536 voxels would take about 65.54 seconds for a single slice. Extending this to 4D-MRI data or higher-dimensional scans, such as 512 × 512 or 1024 × 1024, results in exponential increases in computational time.

Figure 1 illustrates the time required by our NLS fitting implementation for varying numbers of MRI slices on HPC systems and NVIDIA GPUs. For a single slice, the theoretical time on HPC is 1.09 minutes, while the NVIDIA GPU takes 2.24 minutes. Assuming a linear increase in time with the number of slices in a dataset, one can easily reach the HPC requirement of 1092.3 minutes, and NVIDIA GPU requirement of 2240 minutes for 1000 images. This data highlights the substantial computational demands of NLS fitting.

Due to the time-consuming nature of NLS methods, they are often limited to knee cartilage ROIs. However, recent research highlights the importance of the relaxation map of the full knee joint MRI for assessing osteoarthritis (OA) progression and detecting subtle changes in tissue properties beyond just the cartilage [

20]. Therefore, researchers have started exploring artificial intelligence (AI) models as faster alternatives to NLS.

1.2. AI-Based Exponential Fitting

Recent advancements in AI offer suitable alternatives to traditional NLS methods. AI models, such as random forest regression, neural networks (NNs), and deep NNs have been extensively utilized to enhance exponential model fitting [

21,

22,

23,

24]. These models benefit from rapid training and deployment, thus providing stable and accurate curve fitting that is usually faster than existing NLS methods [

26,

27,

28]. By utilizing advanced function approximation abilities, AI models can efficiently address the issues of slow convergence and suboptimal solutions associated with traditional NLS methods [

23,

24,

25,

26].

By incorporating AI into the fitting process, researchers have achieved significant improvements in parameter mapping [

29,

30,

31,

32]. Additionally, AI models can be trained in an end-to-end manner, i.e., learning optimal mappings from raw k-space or undersampled multi-contrast MRI data to T1ρ maps without the need for explicit MRI reconstruction and NLS fitting [

33].

Therefore, researchers are actively exploring faster methods for obtaining quantitative MRI values of the knee joint, including deep learning (DL) approaches [

34,

35,

36,

37,

49,

50,

51,

52]. However, most supervised DL methods [

34,

35,

36,

37] rely on reference values produced by NLS methods. This requires applying NLS to thousands of voxels in each 3D image, and this process must be repeated for every image in a large dataset.

Moreover, the integration of AI-based models with traditional NLS methods has led to the development of hybrid approaches that utilize the strengths of both methods. For example, DL models can provide initial parameter estimates or refine results from NLS methods, thus, enhancing accuracy and robustness in T1ρ estimation.

Table 1 presents a description of existing AI-based exponential fitting methods. The table highlights that the majority of AI-based solutions predominantly focus on ME fitting, leaving SE and BE relaxation models relatively underexplored. This limitation creates a significant gap in addressing the diverse relaxation dynamics present in different tissues. Additionally, most existing approaches are often sensitive to noise and prone to inaccuracies in parameter estimation, not providing similar goodness of fit properties as NLS-based techniques.

This gap underscores the importance of hybrid approaches, which integrate the strengths of DL and NLS. Such integration ensures improved parameter estimation, enhanced robustness to noise, and better handling of complex multi-component T1ρ mapping tasks. Thus,

Table 1 further emphasizes the need for methods that go beyond ME fitting and utilize hybrid strategies to overcome the limitations of AI-based or traditional approaches.

1.3. Proposed Solution

Although AI-based exponential fitting models have demonstrated remarkable performance, most researchers have primarily focused on mono-exponential (ME) fitting, with limited exploration of bi-exponential (BE) and stretched-exponential (SE) fitting. Additionally, many AI-based exponential fitting methods require actual MRI data as a reference for training. To address these gaps, this paper proposes the HDNLS, a hybrid model for fast multi-component fitting, dedicated in this work for T1ρ mapping of the knee joint. In HDNLS, we initially designed a DL model that uses synthetic data for training, thus, eliminating the need for reference MRI data. However, the estimated map may be sensitive to noise, particularly in the short component of the BE model. To address this, the results from the proposed DL model are further refined using NLS with an optimized number of iterations. To optimize the number of iterations, this paper presents an ablation study in which we analyze the trade-off between the number of NLS iterations and the mean normalized absolute difference (MNAD), as well as between the NLS iterations and normalized root mean squared residuals (NRMSR).

1.4. Contributions

The key contributions of the paper are as follows:

a) Initially, a DL-based multi-component T1ρ mapping method is proposed. This approach utilizes synthetic data for training, thereby eliminating the need for reference MRI data.

b) The HDNLS method is proposed for fast multi-component T1ρ mapping in the knee joint. This method integrates DL and NLS. It effectively addresses key limitations of NLS, including sensitivity to initial guesses, poor convergence speed, and high computational cost.

c) Since HDNLS's performance depends on the number of NLS iterations, it becomes a Pareto optimization problem. To address this, a comprehensive analysis of the impact of NLS iterations on HDNLS performance is conducted.

d) Four variants of HDNLS are suggested that balance accuracy and computational speed. These variants are Ultrafast-NLS, Superfast-HDNLS, HDNLS, and Relaxed-HDNLS. These methods enable users to select a suitable configuration based on their specific speed and performance requirements.

2. Proposed Methodology

The measured signal

s of the relaxation of a voxel in position

x, at TSL specified by

t, can be expressed as:

where

v is the noise, and

is the relaxation model with parameters

. For simplicity, we will omit the spatial position

x, assuming it corresponds to the relaxation process in one voxel. Note that the parameters

are also related to that specific voxel.

2.1. Multi-Component Relaxation Models

Generally, ME, BE, and SE models are commonly used for fitting the T1ρ map.

Table 2 presents the mathematical formulations, associated parameters, descriptions, and applicable ranges for these three models. The ME model assumes a homogeneous tissue environment, while the BE model introduces two compartments with distinct relaxation times, and the SE model accounts for heterogeneous environments with distributed relaxation rates.

Table 3 highlights the key features, advantages, and disadvantages of each multi-component relaxation model. The choice of the specific model depends on the tissue characteristics and the requirements of the analysis. While the ME model is simple and suitable for homogeneous tissues, the BE model provides a more detailed representation of tissues with two relaxation components but is computationally more demanding. The SE model offers a balance by modeling complex tissue environments with fewer parameters and greater stability, though its physical interpretation can be less intuitive.

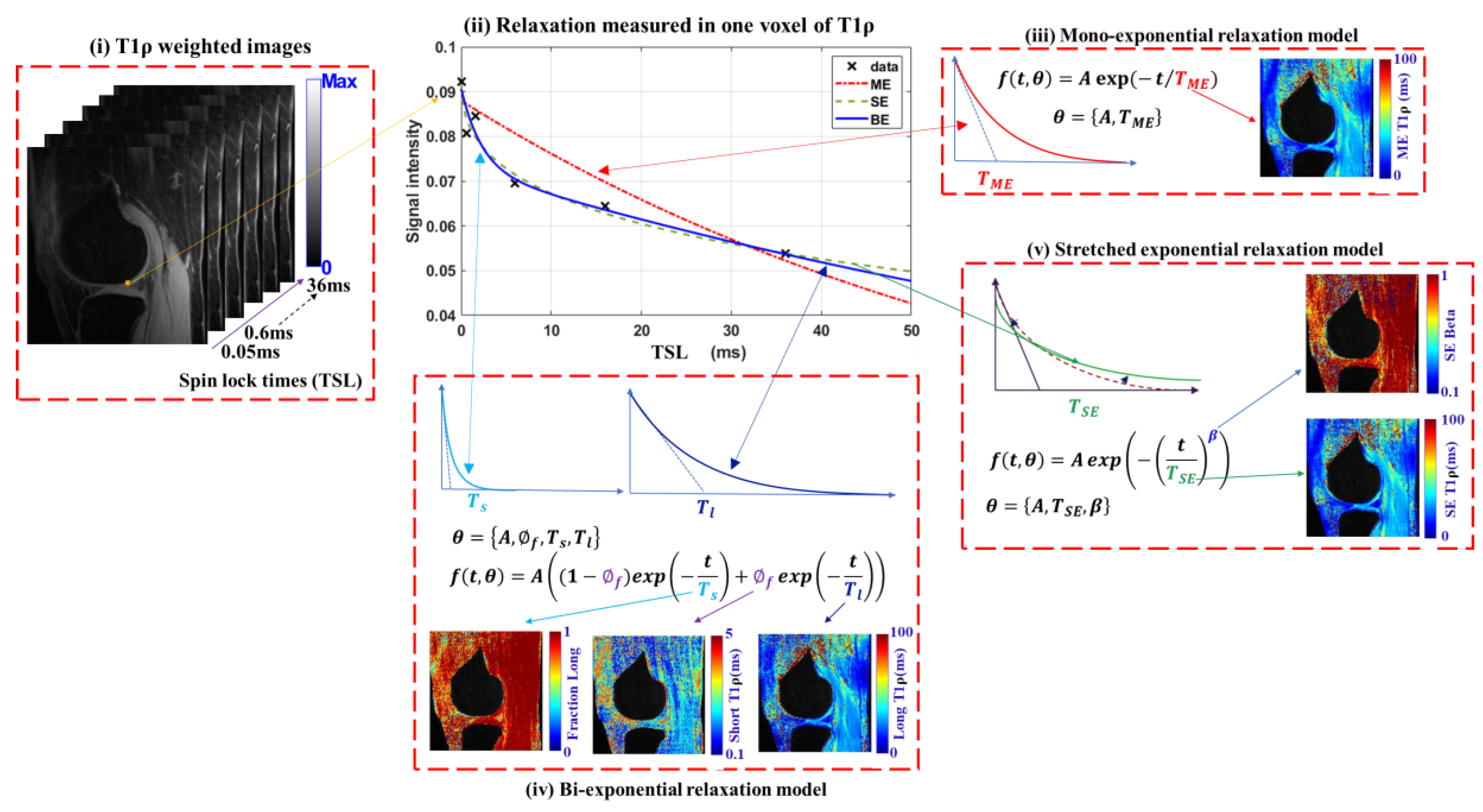

Figure 2 illustrates the working of multi-component relaxation models and their respective outputs. It includes T1

weighted images with six TSLs and voxel-wise relaxation measurements. It presents the expected T1ρ maps obtained from ME, BE (long component, fraction of long component, and short component), and SE models (SE-T1ρ map and Beta (β) parameter).

The NLS approach fits the parameters voxel-wise minimizing the squared Euclidean norm of the residual, using:

where

is the number of TSLs. This is solved using iterative algorithms such as in [

9].

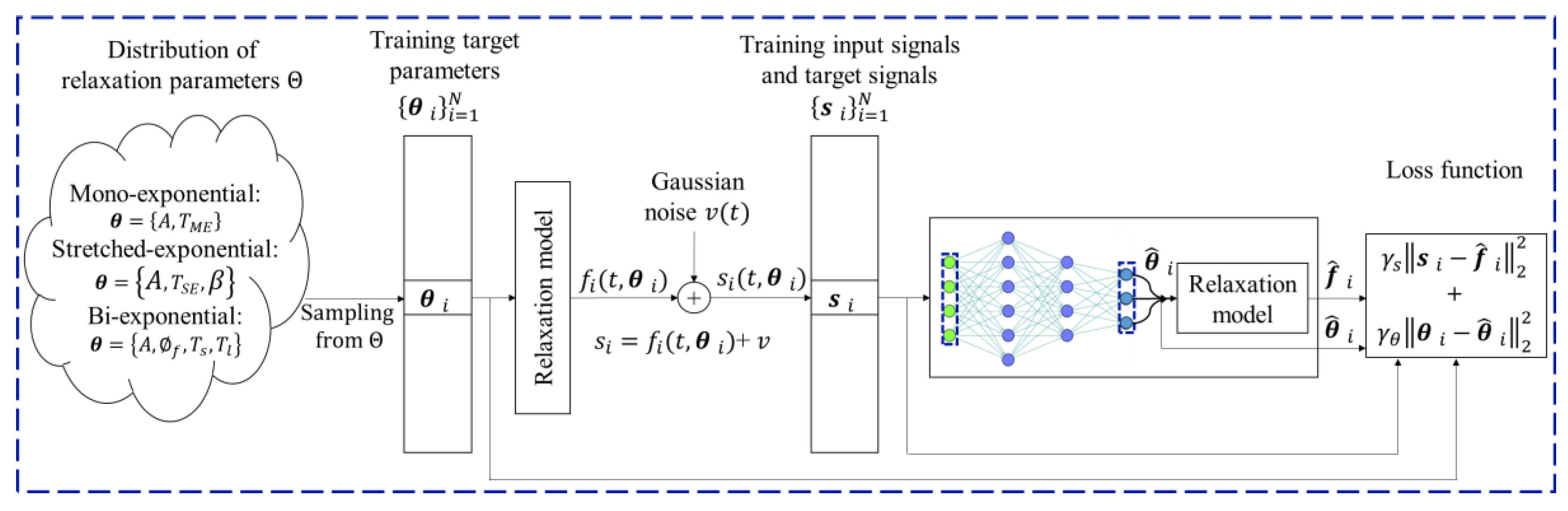

2.2. Deep Learning-Based Multi-Component Relaxation Models

Figure 3 shows the diagram of the voxel-by-voxel working of the DL model for fitting multi-component T1ρ relaxation models. Typically, NNs are trained by minimizing the squared error of the target parameters. However, to achieve data consistency, as in NLS estimations, we used a customized loss function, designed as:

where

is the index of the data elements in the training dataset,

, being

, a column vector with the measured relaxation signal,

the fitting network with learning parameters

, and

is the relaxation signal produced with the estimated parameters

, using any of the equations presented in

Table 2. Target parameters

are sampled from a known distribution

, and

are synthetically generated using equation (1) and equations presented in

Table 2 and the sampled parameters.

The first term of the loss function tries to reduce the residue, as in NLS approaches, producing a relaxation curve consistent with the synthetically generated measured values at the voxel. The second term tries to reduce the error against the ground truth values. This term also acts as a regularization in the NLS sense. We used and .

The NN architecture comprises 7 repeated blocks of fully connected layers, each containing 512 intermediate elements followed by a nonlinear activation function and dropouts. Thereafter, we utilize customized layers to evaluate the relaxation values for the customized loss, as described in equation (3). Finally, the regression layer is used to predict the T1ρ maps. This network estimates the relaxation parameters voxel-wise, like any of the NLS-based approaches.

2.3. Sensitivity Analysis of DL Model

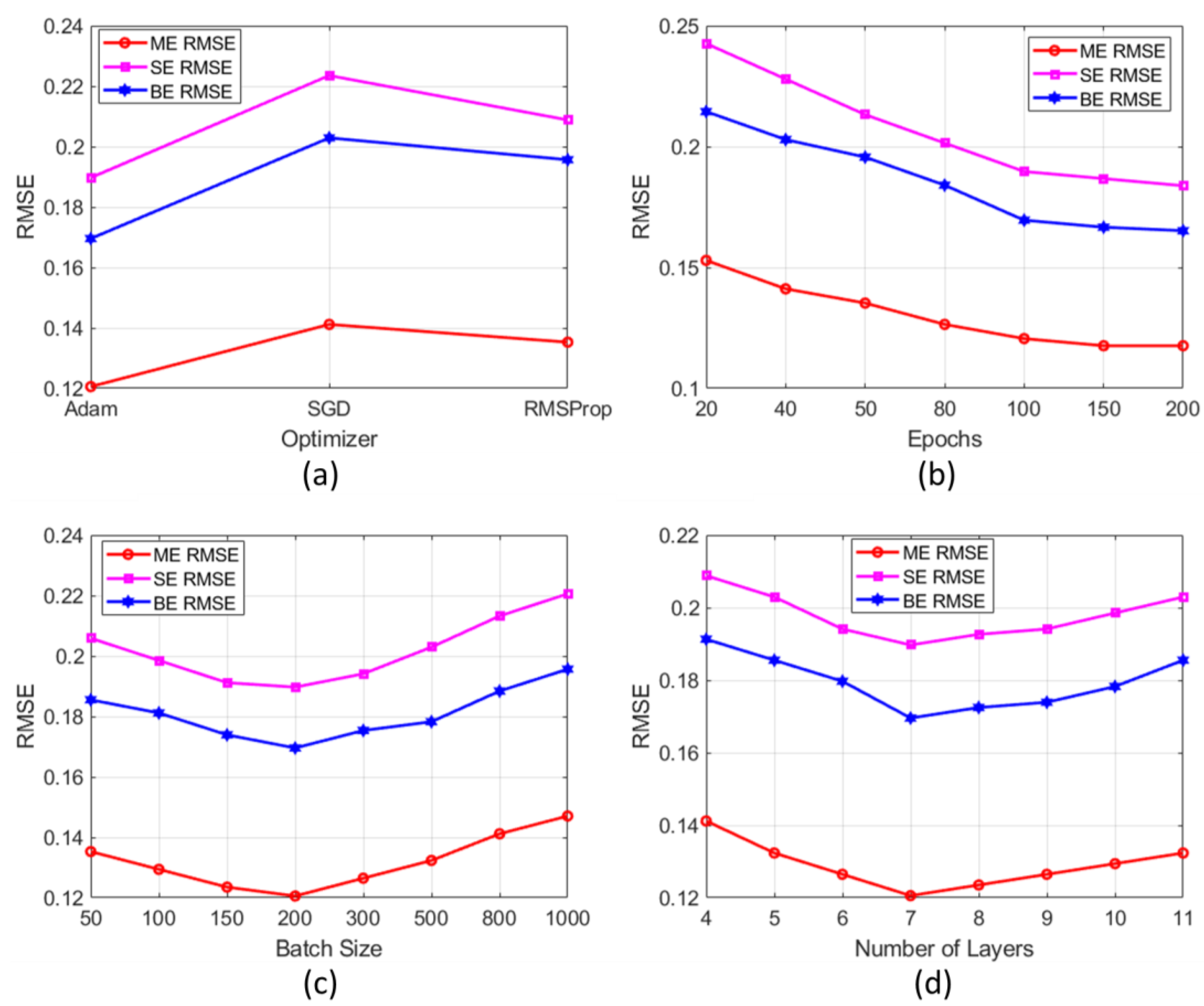

We performed a sensitivity analysis of the proposed DL model to determine the optimal configuration of hyperparameters. Initially, multiple trial-and-error experiments were conducted using various hyperparameter values commonly reported in the literature. The final configuration comprised 7 fully connected layers, each containing 512 intermediate elements. Five different activation functions are also evaluated such as Gaussian Error Linear Unit (GELU), Leaky ReLU, hyperbolic tangent (Tanh), Swish, and ReLU. The model was trained using the Adam optimizer, with a learning rate initialized at 1.0e-3, over a maximum of 100 epochs. Each epoch processed mini-batches size of 200 samples. We selected = 10 and = 1 as the optimal weights for the proposed customized loss function. During the sensitivity analysis, we varied only the specific parameter under evaluation while keeping all other parameters fixed.

Figure 4 illustrates the impact of (a) optimizer selection (Adam, SGD, and RMSProp), (b) number of epochs (20 to 200), (c) batch size (50 to 1000), and (d) number of layers (4 to 11). From

Figure 4 (a), it is evident that the RMSE shows a decreasing trend as the number of epochs increases. It eventually stabilized around 100 epochs. Adam outperformed SGD and RMSProp by achieving significantly lower RMSE values (see

Figure 4 (b)). Smaller batch sizes achieved lower RMSE values with performance stabilizing beyond a batch size of 200 (see

Figure 4 (c)). Finally, seven fully connected layers achieved noticeably lower RMSE values compared to other configurations (see

Figure 4 (d)).

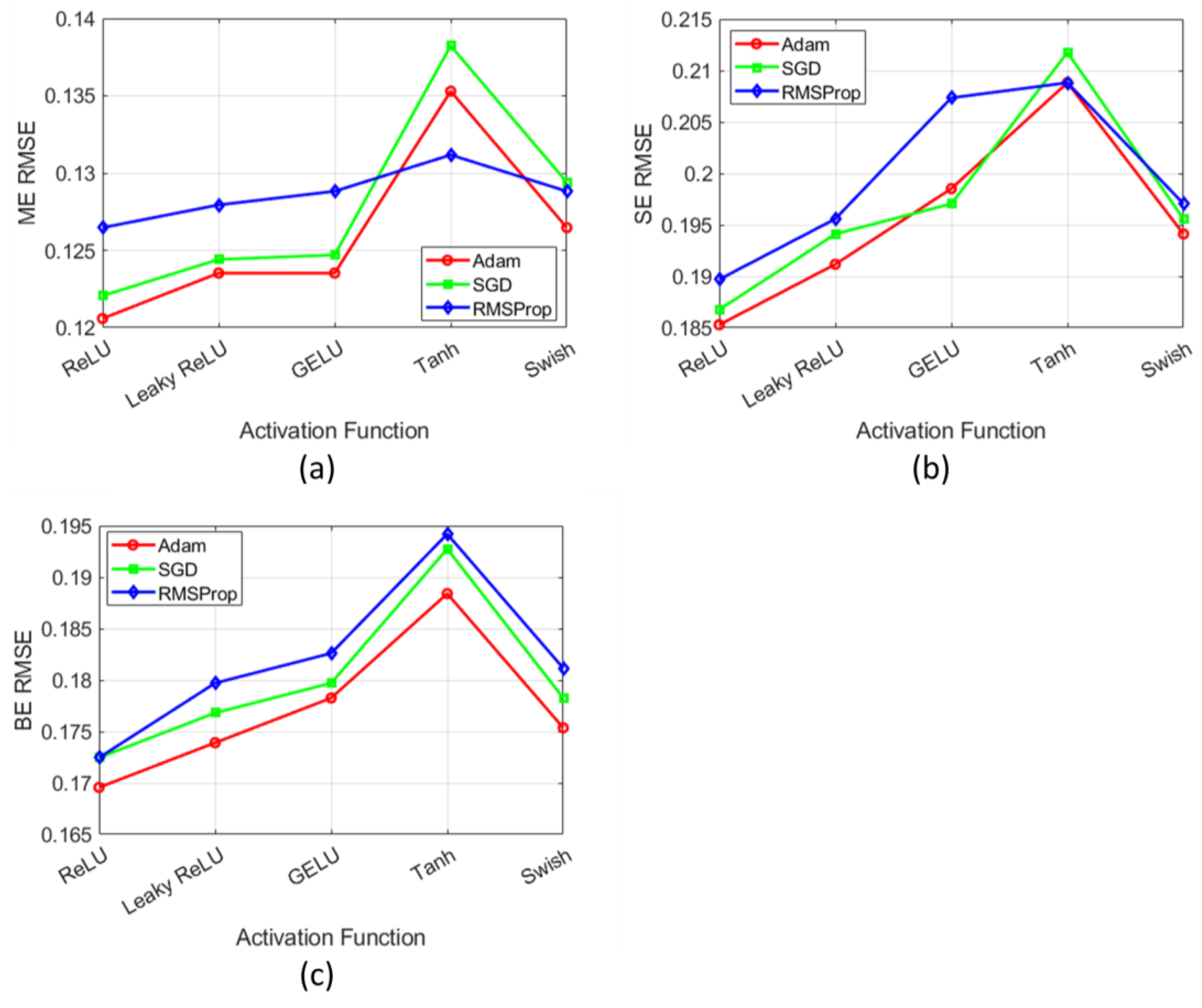

Figure 5 presents the sensitivity analysis of activation functions (ReLU, Leaky ReLU, GELU, Tanh, and Swish) for the DL model. The analysis evaluates these functions across three optimizers such as Adam, SGD, and RMSProp. It shows RMSE variations for ME, SE, and BE components under different activation function-optimizer combinations. Among these, the Adam optimizer combined with the ReLU activation function achieves significantly lower RMSE values across all ME, SE, and BE components.

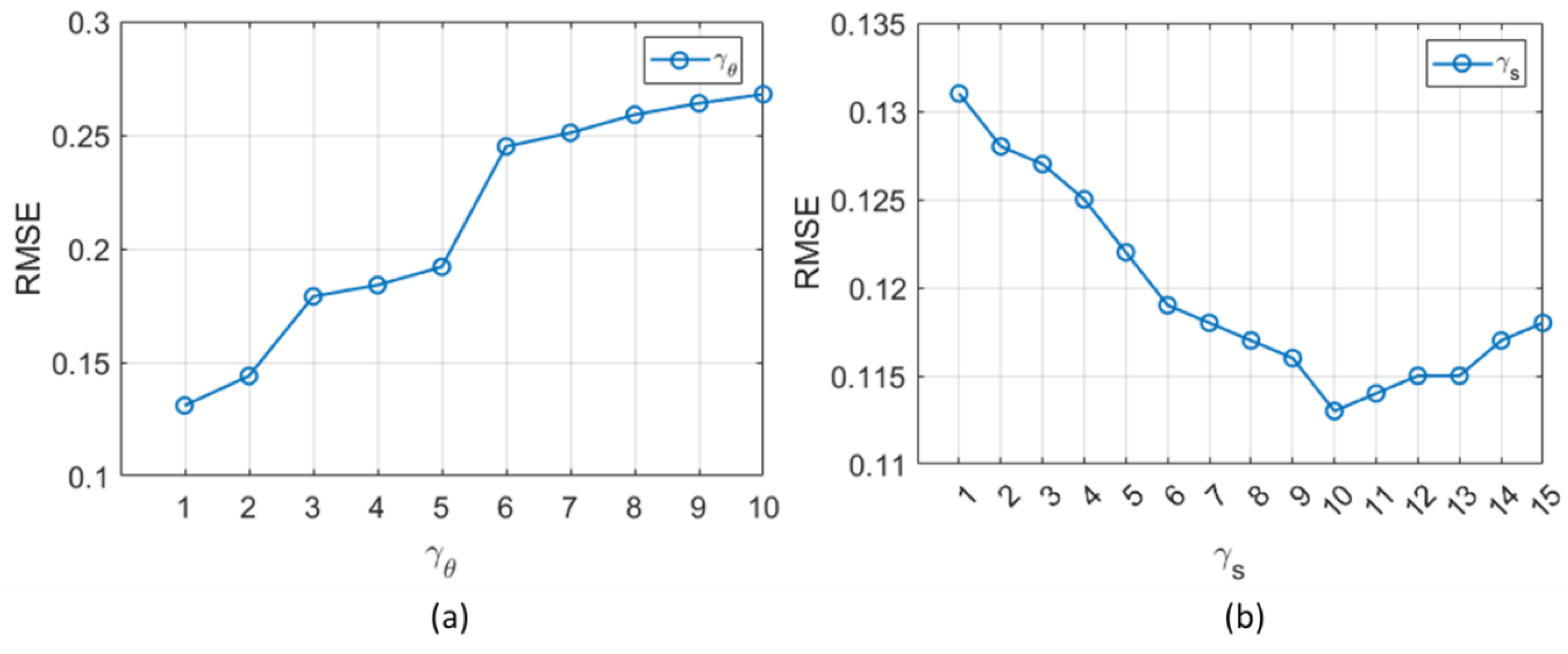

Finally, the sensitivity analysis is conducted to evaluate the impact of varying

and

in the customized loss function on validation data. For better analysis, we evaluated the average RMSE values across all ME, SE, and BE components.

Figure 6 (a) shows that increasing

from 1 to 10, with

= 1, results in a rise in RMSE. This emphasizes the importance of keeping

relatively low. In contrast,

Figure 6 (b) demonstrates a decreasing trend in RMSE as

increases from 1 to 15, with

= 1. This indicates the benefits of assigning a higher weight to

. However, continually increasing

in the loss function places an increasingly higher emphasis on minimizing the discrepancy between the measured relaxation signal

and the model-predicted signal

. While this might improve the consistency of the relaxation curve with the synthetic measurements, it can increase the error in the estimated parameters. The model prioritizes signal fitting at the expense of accurately estimating the parameters

, as the second term in the loss function becomes relatively low, diminished the impact of the regularization term in stabilizing the parameter estimation. As shown in

Figure 6 (b), RMSE increases when

exceeds 10, indicating a poor balance between signal consistency and parameter accuracy. Based on these observations, we selected

= 10 and

= 1 as the optimal weights for our loss function.

and on validation data. (a) Impact of on RMSE with fixed at 1, demonstrating an increase in RMSE as rises from 1 to 10. (b) Influence of on RMSE with fixed at 1, showing decreasing RMSE values as increases from 1 to 15. However, RMSE starts to increase beyond = 10.

2.4. Training and Validation Analysis

To ensure a robust evaluation of the proposed DL model, the synthetic dataset was divided into three subsets: training, validation, and test data, in an 80:10:10 ratio. The training subset (80% of the data) was used to train the DL model and optimize its parameters. To prevent overfitting, the validation subset (10% of the data) was employed to monitor the model’s performance during training and fine-tune hyperparameters.

Figure 7 illustrates the training and validation loss curves for 10 and 100 epochs, respectively. In

Figure 7 (a), the difference between training and validation loss values is more apparent, reflecting the initial stages of model training. In contrast,

Figure 7 (b) shows that, with 100 epochs, it is difficult to distinguish between the loss values for both training and validation converge. This convergence indicates that the DL model does not suffer from overfitting.

This partitioning strategy also ensures efficient training of the DL model while providing a fair and unbiased assessment of its generalization capability. Data for each subset was randomly selected in a stratified manner. Therefore, the used data also preserves the distribution of key features across all subsets. This approach guarantees consistency and reliability in the evaluation process.

Finally, the test subset, comprising 10% of the data, was reserved for the final evaluation of the model’s performance on unseen data (see analysis in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 and

Table 7).

2.5. HDNLS

Figure 8 illustrates the proposed HDNLS-based fitting of multi-component T1ρ relaxation models. The estimated map obtained from the DL model may be sensitive to noise, particularly in the short component of BE. To mitigate this issue, the results from the DL model are further refined using NLS iterations. The DL results serve as an initial guess for NLS. This helps to address both the initial guess dependency and poor convergence speed associated with NLS.

In this paper, TRCG [

9,

45] is used to solve the NLS problem. At each iteration

, the parameters are estimated using:

This update aims to minimize the residuals as:

Here, represents the observed data, and denotes the model predictions based on the updated parameters. TRCG ensures that each step effectively refines the parameter estimates. Thus, it enhances the convergence of the optimization process to achieve an optimal fit to the data.

2.6. T1ρ -MRI Data Acquisition and Fitting Methods

All the experiments were performed on a 3T MRI scanner with the magnetization-prepared angle-modulated partitioned k-space spoiled gradient echo sequence snapshots (MAPSS) [

44], using six spin-lock times (TSL) values 0.05, 0.6, 1.6, 6, 16, and 36 ms. We scanned a total of 12 healthy volunteers, with a mean age of 38 and SD=12.4 years old (n=7 males and n=5 females). The MRI scans have a voxel size of 0.7mm×0.7mm×4mm, with an FOV of 180mm×180mm×96mm. This study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of New York University Langone Health and was compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). All volunteers provided their consent before MRI scanning.

For NLS-based fitting, we used 2000 iterations of the TRCG method [

45]. The ME model assumes the T1ρ values can be in the range of 1-300 ms. The SE model assumes the T1ρ values can be in the range of 1-300 ms and β can be in the range of 0.1-1. Because we observed no ME relaxation below 5ms, we assume that the long component of the BE model can be in the range of 5-300 ms, the short component can be in the range of 0.5-4 ms, and the BE fraction can be in the range of 0.01-0.99.

The DL model is trained using the Adam optimizer with a maximum of 100 epochs, and each epoch processes mini-batches of 200 samples. The initial learning rate is set to 1.0e-3. The dropout value is set to be 0.1. The proposed model is tested on 3D-T1ρ MRI data from five different healthy subjects. The DL model was trained on 5 healthy data sets.

2.7. Performance Metrics

For comparative analysis, four performance metrics are employed: the median of normalized absolute difference (MNAD), normalized root mean squared residuals (NRMSR), fitting time, and normalized root mean squared error (NRMSE).

Table 4 provides detailed descriptions and mathematical formulations of these metrics.

3. Optimal Selection of NLS Iterations for HDNLS

The main objective of this section is to evaluate and compare the performance metrics of NLS and HDNLS on synthetic data by varying the number of NLS iterations. Specifically, the focus is on assessing the convergence speed of both methods and determining whether HDNLS can achieve similar performance to NLS with improved speed.

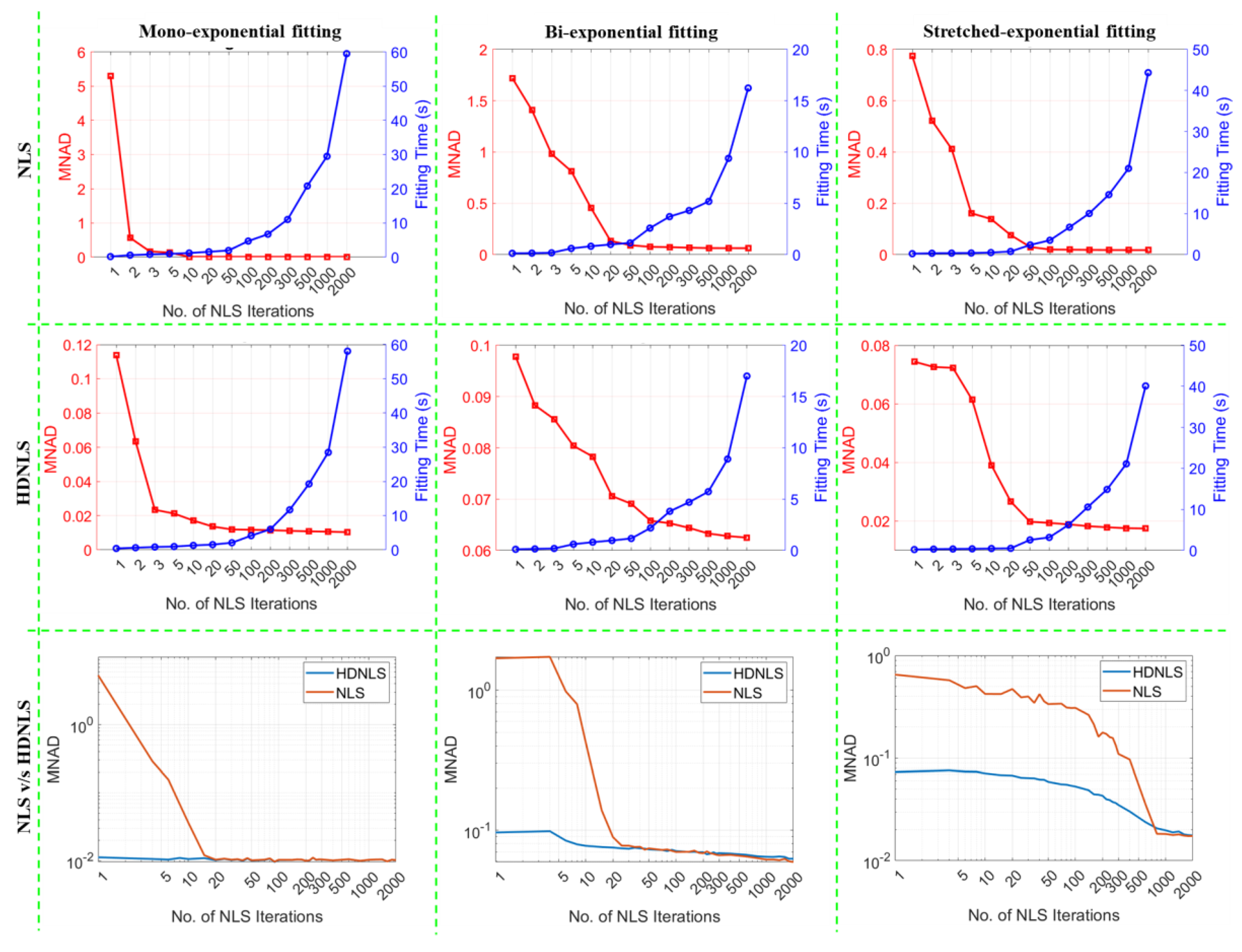

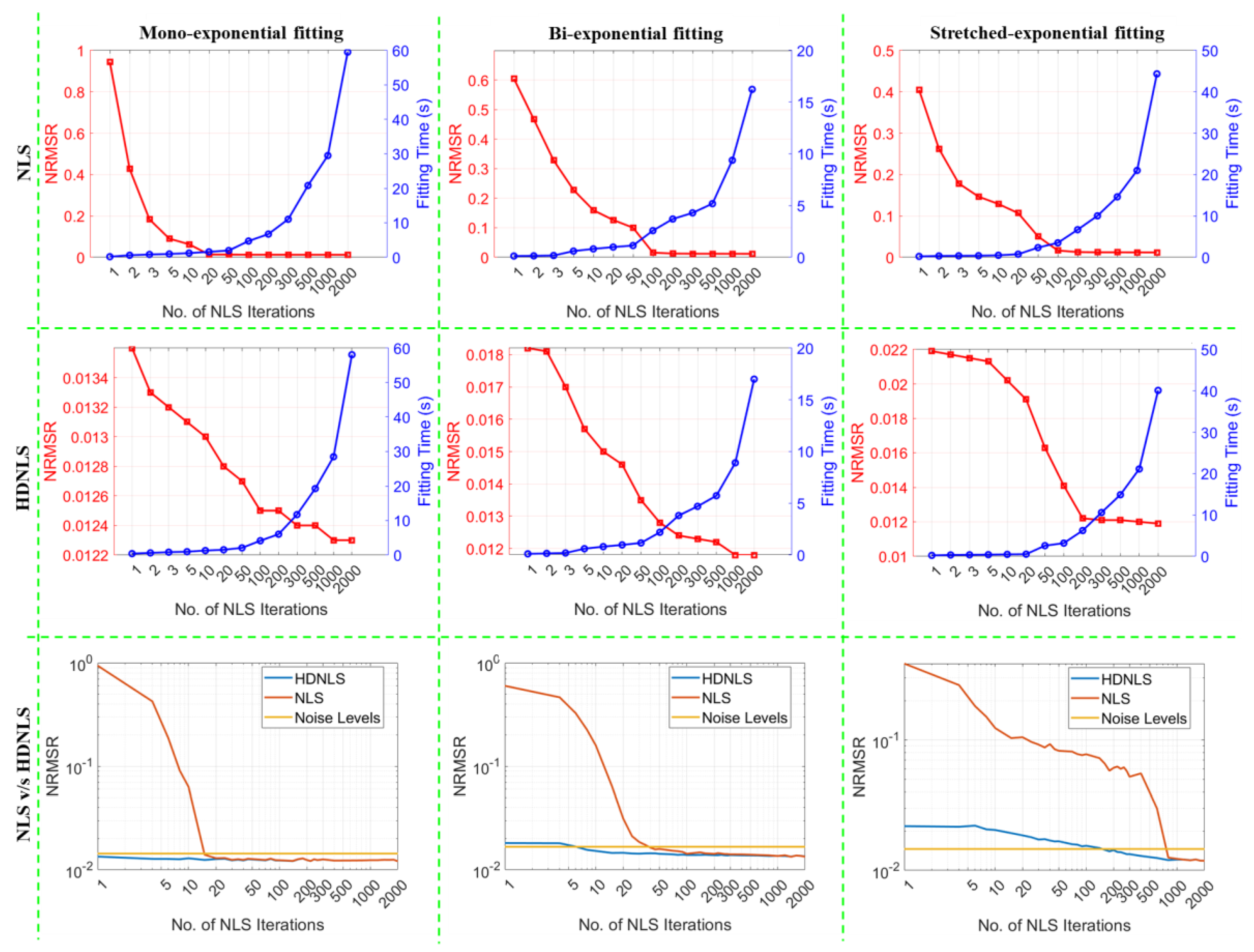

Figure 9 shows the comparison between NLS and HDNLS on synthetic data in terms of MNAD across three different fitting models such as ME, SE, and BE. Row 1 shows the trade-off between fitting time (blue) and MNAD (red) for NLS as the number of NLS iterations increases. For each fitting model, MNAD decreases initially with more iterations but eventually shows a minor reduction, while the fitting time increases at a rapid rate. Row 2 shows the performance trade-off between fitting time and MNAD for the HDNLS approach. It also shows that as the number of NLS iterations increases, the HDNLS achieves significantly lesser MNAD values. However, after 500 iterations, the improvement in MNAD becomes marginal compared to the increase in fitting time. Row 3 provides direct comparisons between NLS and HDNLS. It shows that HDNLS takes significantly less time compared to NLS when the number of NLS iterations is less than 300. Thereafter, both NLS and HDNLS show almost similar MNAD values with no significant difference.

Similarly,

Figure 10 presents the performance of NLS and HDNLS across ME, SE, and BE fitting models on synthetic data in terms of NRMSR. The yellow line represents the NRMSR of noise only. The primary goal of NLS and HDNLS is to reduce the NRMSR to levels just below the noise-level. It is found that in the case of HDNLS, there are little or no benefits in exceeding 500 iterations, except for the SE component. Please note that due to the significant variations in the scale of values for both NLS and HDNLS, it becomes difficult to observe changes in NLS when the number of iterations exceeds 100, 500, and 1000, respectively for ME, BE, and SE components. To better illustrate this, we present the comparison of NRMSR between NLS and HDNLS in row 3, clearly demonstrating the improved convergence speed of HDNLS over NLS. Additionally, the difference in NRMSR for HDNLS after 500 iterations is minimal and can be disregarded.

Figure 9.

Comparison of NLS and HDNLS across mono-exponential, bi-exponential, and stretched-exponential fitting models on synthetic data. Row 1 illustrates the trade-off between fitting time and MNAD for NLS. Row 2 shows the trade-off between fitting time and MNAD for HDNLS. Row 3 shows the convergence of NLS and HDNLS in terms of MNAD.

Figure 9.

Comparison of NLS and HDNLS across mono-exponential, bi-exponential, and stretched-exponential fitting models on synthetic data. Row 1 illustrates the trade-off between fitting time and MNAD for NLS. Row 2 shows the trade-off between fitting time and MNAD for HDNLS. Row 3 shows the convergence of NLS and HDNLS in terms of MNAD.

From Row 3 of both

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, it is evident that HDNLS converges significantly faster than standard NLS in terms of MNAD and NRMSR, respectively. This makes HDNLS an efficient choice for determining the number of NLS iterations based on specific requirements. For scenarios where speed is the highest priority and small performance compromises are acceptable, 10 iterations, referred to as Ultrafast-NLS, provide quick results with minimal computational cost. Superfast-HDNLS, with 50 NLS iterations, strikes a balance between speed and performance, offering a faster alternative with acceptable accuracy. HDNLS with 200 iterations achieves an optimal middle ground, delivering both rapid convergence and higher performance. However, for SE, we observed that the results at 200 iterations are not as desirable as those for ME and BE; therefore, we selected HDNLS with 300 iterations for SE map fitting only.

For those who prioritize performance over speed, 500 iterations, termed Relaxed-HDNLS, provide the best results while tolerating slower computation times. Thus, HDNLS allows users to select a suitable configuration based on their specific speed and performance requirements.

Figure 10.

Performance metrics comparison of NLS and HDNLS in terms of fitting time and normalized root mean squared residual (NRMSR) across ME, SE, and BE fitting models. Row 1 shows the trade-off between fitting time and NRMSR for NLS. Row 2 shows the trade-off between fitting time and NRMSR for HDNLS. Row 3 presents the convergence of both NLS and HDNLS with respect to log (NRMSR).

Figure 10.

Performance metrics comparison of NLS and HDNLS in terms of fitting time and normalized root mean squared residual (NRMSR) across ME, SE, and BE fitting models. Row 1 shows the trade-off between fitting time and NRMSR for NLS. Row 2 shows the trade-off between fitting time and NRMSR for HDNLS. Row 3 presents the convergence of both NLS and HDNLS with respect to log (NRMSR).

To check the performance of these HDNLS variants, we further tested them on real MRI data (see

Section 2.4 for dataset details). Due to the unavailability of ground truth T1ρ maps, we used the NLS-based estimated T1ρ map as the ground truth. The estimated ME and SE T1ρ maps of the whole knee from NLS and HDNLS variants are presented in

Figure 11, along with their respective squared error compared to the NLS-based ME T1ρ map. Similarly,

Figure 12 shows the ME and SE T1ρ maps for the knee cartilage only. Both figures demonstrate that HDNLS and Relaxed-HDNLS achieve significantly better results, with notably lower errors, compared to Ultra-HDNLS and Super-HDNLS.

Although it is challenging to visually distinguish differences between the obtained T1ρ maps, the evaluated squared error differences provide a clear distinction. Higher squared error values indicate poorer performance. From

Figure 11 and

Figure 12, the squared error maps for HDNLS and Relaxed-HDNLS show significantly lower errors. This highlights their superior performance and closer alignment with the NLS-based T1ρ maps.

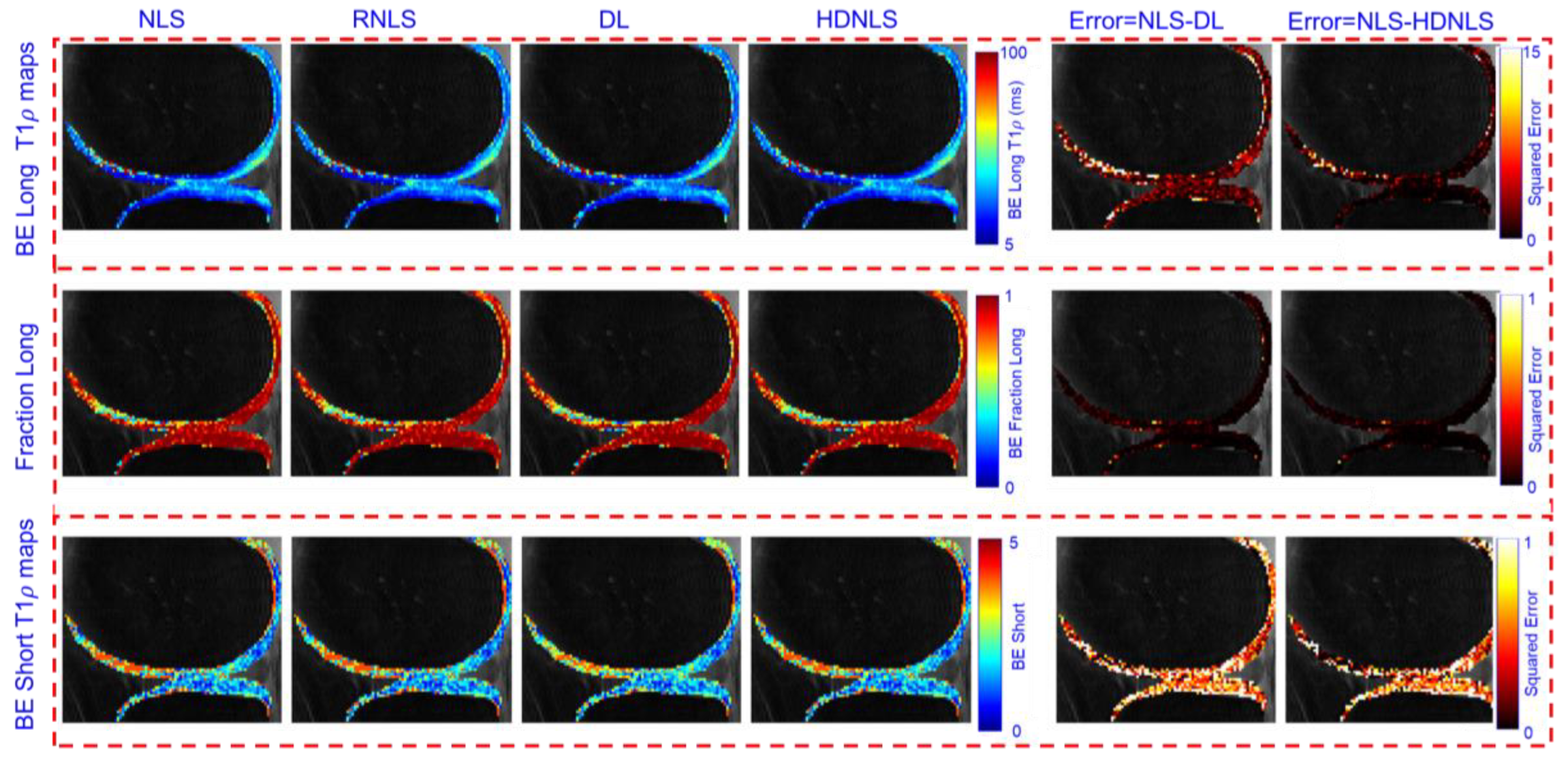

Figure 13 presents the estimated BE long T1ρ component, the fraction of the long T1ρ component, and short T1ρ maps of the whole knee from NLS and HDNLS variants, along with their respective squared errors compared to the ground truth, i.e., the NLS-based ME T1ρ map. Similarly,

Figure 14 shows the estimated BE long T1ρ component, the fraction of the long T1ρ component, and short T1ρ maps for knee cartilage only. Both figures demonstrate that HDNLS and Relaxed HDNLS achieve significantly better results with much lower errors compared to Ultra-HDNLS and Super-HDNLS.

Table 5 and

Table 6 provide a quantitative analysis of HDNLS variants, i.e., Ultra-HDNLS, Super-HDNLS, HDNLS, and Relaxed-HDNLS, for estimating ME, SE, and BE T1ρ maps using real data for the full knee and knee cartilage, respectively. The Relaxed-HDNLS variant outperforms the others by achieving the minimum MNAD and NRMSR values. In contrast, Ultra-HDNLS provides the fastest fitting time for the estimation of all ME, SE, and BE T1ρ maps, but has higher MNAD and NRMSR values. Therefore,

Table 5 and

Table 6 highlight a trade-off in selecting the best approach. Faster fitting times come at the cost of performance. This necessitates careful consideration of whether to prioritize speed or accuracy when estimating T1ρ maps.

4. Performance Analysis

Based on the visual and quantitative analysis presented in

Section 3, we have identified a trade-off in selecting the best approach. Faster fitting times come at the cost of performance, necessitating careful consideration of whether to prioritize speed or accuracy when estimating T1ρ maps. Therefore, we have selected an optimized HDNLS variant named HDNLS. For ME and BE, it will use 200 NLS iterations, while for SE, we have chosen 300 iterations. The idea is to select a solution that is around 30 times faster than NLS with significantly fewer errors on synthetic data. For ME and BE, when NLS iterations are 200, we achieve around 34 times better fitting speed with comparable performance to NLS. However, with 200 iterations for SE fitting, we observed slightly more errors compared to when NLS iterations were set to 300. Due to this, for SE fitting, HDNLS (NLS iterations=300) shows a speed improvement of approximately 27 times better than NLS, with similar results compared to NLS.

The main objective of this section is to compare the performance of HDNLS against NLS, RNLS, and DL.

Figure 15 and

Figure 16 present the estimated ME and SE T1ρ maps for the full MRI joint and knee cartilage, obtained using NLS, RNLS, DL, and HDNLS, respectively. The error is also computed between NLS and DL, and NLS and HDNLS for the full knee joint and knee cartilage ROIs. The analysis shows that the error between NLS and HDNLS is lower compared to that between NLS and DL. This indicates that, compared to DL, the proposed HDNLS method can more effectively serve as an alternative to NLS and RNLS for estimating ME T1ρ, SE T1ρ, and SE beta maps.

The higher error observed in the BE short component is due to its susceptibility to noise caused by low signal intensity and rapid decay dynamics. This fast decay can lead to insufficient signal sampling, negatively affecting accurate fitting. Furthermore, short components exhibit increased sensitivity to minor variations in model parameters, resulting in escalated errors during the fitting process.

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 show the predicted BE long T1ρ maps, the fraction of the long BE T1ρ component, and the short T1ρ maps for the full knee joint and knee cartilage ROIs, generated using NLS, RNLS, DL, and HDNLS, respectively. The error between NLS and DL, and between NLS and HDNLS, is also calculated for both the full knee joint and knee cartilage ROIs. The analysis demonstrates that the error between NLS and HDNLS is lower than that between NLS and DL. Thus, it is revealed that, compared to DL, the HDNLS method is a more effective alternative to NLS and RNLS for estimating BE components.

Table 7 presents a quantitative analysis of NLS, RNLS, DL, and HDNLS methods for multi-component T1ρ mapping (ME, SE, and BE) on synthetic data in terms of MNAD, fitting time (in seconds), and NRMSR. It indicates that though, NLS outperforms RNLS, DL, and HDNLS, but compared to RNSL and HDNLS this difference is not significant. Additionally, DL achieved better speed compared to the other approaches, but it also achieved the poorest performance. Overall, the HDNLS achieved comparable performance to NLS and RNLS and significantly better performance over DL.

Table 7.

Quantitative analysis of NLS, RNLS, DL, and HDNLS for ME, SE, and BE T1ρ maps on synthetic data.

Table 7.

Quantitative analysis of NLS, RNLS, DL, and HDNLS for ME, SE, and BE T1ρ maps on synthetic data.

| Method |

Metric |

NLS |

RNLS |

DL |

HDNLS |

| ME |

MNAD (%) |

3.65 |

3.69 |

4.29 |

3.70 |

| Fitting time (sec) |

37.48 |

32.83 |

0.79 |

4.94 |

| NRMSR |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

| SE |

MNAD (%) |

6.18 |

6.27 |

7.61 |

6.32 |

| Fitting time (sec) |

41.9 |

37.75 |

0.61 |

4.17 |

| NRMSR |

0.15 |

0.15 |

0.18 |

0.16 |

| BE |

MNAD (%) |

16.19 |

16.36 |

18.37 |

16.47 |

| Fitting time (sec) |

11.73 |

11.16 |

0.52 |

2.48 |

| NRMSR |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

Table 8 presents a comparison of MNAD and NRMSE for DL, and HDNLS methods for multi-component T1ρ mapping (ME, SE, and BE) on real data for both the full knee joint and knee cartilage ROI. The results show that HDNLS significantly outperforms DL by achieving lower MNAD and NRMSE values across all ME, SE, and BE categories. This indicates that HDNLS is a better alternative to NLS than DL for T1ρ mapping.

Table 9 presents a computational speed (in seconds) analysis of NLS, RNLS, DL, and HDNLS methods for multi-component T1ρ mapping (ME, SE, and BE) on real data for both the full knee and knee cartilage ROI. The results indicate that HDNLS significantly outperforms the traditional methods (NLS and RNLS) in terms of computational speed, although it is slower than DL. Though DL demonstrates substantial speed improvements over NLS, RNLS, and HDNLS, it also results in greater error compared to HDNLS (see

Table 8). As stated in

Section 3, our objective was to find a suitable trade-off between performance and computational speed. Therefore, while HDNLS takes more time than DL, it also shows significant performance improvements over DL. Thus, HDNLS achieves comparable performance to NLS and RNLS. Compared to NLS, it provides approximately 13 to 14 times better speed for each ME, SE, and BE component for the full knee joint. Additionally, for the knee cartilage ROI, it offers about 11, 12, and 11 times better speed over NLS, respectively.

6. Conclusion

This paper introduced HDNLS, a hybrid model that combined DL and NLS for efficient multi-component T1ρ mapping in the knee joint. HDNLS effectively addressed key limitations of NLS such as sensitivity to initial guesses, poor convergence speed, and high computational costs. By utilizing synthetic data for training of DL model, we eliminated the need for reference MRI data and enhanced noise robustness through NLS refinements. We conducted a comprehensive analysis of NLS iterations on FastNL and proposed four variants. These variants were Ultrafast-NLS, Superfast-HDNLS, HDNLS, and Relaxed HDNLS. Among these, HDNLS achieved an optimal balance between accuracy and speed. HDNLS achieved performance comparable to NLS and RNLS with a minimum 13-times increase in fitting speed. Although HDNLS is slower than DL, it significantly outperformed in terms of MNAD and NRMSE. Therefore, HDNLS serves as a robust and faster alternative to NLS for multi-component T1ρ fitting.

Author Contribution: Conceptualization, methodology, and writing—original draft preparation D.S.; visualization, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition M.V.W.Z and R.R.R

Figure 1.

Computational time for NLS fitting across different MRI slice counts on HPC (theoretical) and NVIDIA GPU systems.

Figure 1.

Computational time for NLS fitting across different MRI slice counts on HPC (theoretical) and NVIDIA GPU systems.

Figure 2.

Representative visualization of multi-component T1ρ relaxation models in the knee joint.

Figure 2.

Representative visualization of multi-component T1ρ relaxation models in the knee joint.

Figure 3.

Voxel-by-voxel framework of the DL model for fitting multi-component T1 relaxation models with a customized loss function.

Figure 3.

Voxel-by-voxel framework of the DL model for fitting multi-component T1 relaxation models with a customized loss function.

Figure 4.

Sensitivity analysis of the DL model: (a) optimizer selection, (b) epochs, (c) batch size, and (d) number of layers, on RMSE.

Figure 4.

Sensitivity analysis of the DL model: (a) optimizer selection, (b) epochs, (c) batch size, and (d) number of layers, on RMSE.

Figure 5.

Sensitivity analysis of the combination of activation functions (ReLU, Leaky ReLU, GELU, Tanh, and Swish) with optimizers (Adam, SGD, and RMSProp) for the DL model: (a) ME component, (b) SE component, and (c) BE component.

Figure 5.

Sensitivity analysis of the combination of activation functions (ReLU, Leaky ReLU, GELU, Tanh, and Swish) with optimizers (Adam, SGD, and RMSProp) for the DL model: (a) ME component, (b) SE component, and (c) BE component.

Figure 6.

Sensitivity analysis of the loss function with varying

Figure 6.

Sensitivity analysis of the loss function with varying

Figure 7.

Training and validation loss analysis: (a) For 10 epochs and (b) For 100 epochs.

Figure 7.

Training and validation loss analysis: (a) For 10 epochs and (b) For 100 epochs.

Figure 8.

Proposed HDNLS-based fitting of multi-component T1ρ relaxation models in the knee joint.

Figure 8.

Proposed HDNLS-based fitting of multi-component T1ρ relaxation models in the knee joint.

Figure 11.

Estimated HDNLS variants-based ME and SE-T1ρ maps for the full knee joint.

Figure 11.

Estimated HDNLS variants-based ME and SE-T1ρ maps for the full knee joint.

Figure 12.

Estimated HDNLS variants-based ME and SE T1ρ maps for the knee cartilage ROIs only.

Figure 12.

Estimated HDNLS variants-based ME and SE T1ρ maps for the knee cartilage ROIs only.

Figure 13.

Estimated HDNLS variants-based BE long T1ρ, the fraction of the long T1ρ, and short T1ρ maps for the full knee joint.

Figure 13.

Estimated HDNLS variants-based BE long T1ρ, the fraction of the long T1ρ, and short T1ρ maps for the full knee joint.

Figure 14.

Estimated HDNLS variants-based BE long T1ρ, the fraction of the long T1ρ, and short T1ρ maps for knee cartilage ROIs only.

Figure 14.

Estimated HDNLS variants-based BE long T1ρ, the fraction of the long T1ρ, and short T1ρ maps for knee cartilage ROIs only.

Figure 15.

Estimated NLS, RNLS, DL, and HDNLS-based ME and SE T1ρ maps for the full knee joint.

Figure 15.

Estimated NLS, RNLS, DL, and HDNLS-based ME and SE T1ρ maps for the full knee joint.

Figure 16.

Estimated NLS, RNLS, DL, and HDNLS-based ME and SE T1ρ maps for the knee cartilage ROIs only.

Figure 16.

Estimated NLS, RNLS, DL, and HDNLS-based ME and SE T1ρ maps for the knee cartilage ROIs only.

Figure 17.

Estimated NLS, RNLS, DL, and HDNLS-based BE long T1ρ component, the fraction of the long T1ρ component, and short T1ρ maps for the full knee joint.

Figure 17.

Estimated NLS, RNLS, DL, and HDNLS-based BE long T1ρ component, the fraction of the long T1ρ component, and short T1ρ maps for the full knee joint.

Figure 18.

Estimated NLS, RNLS, DL, and HDNLS-based BE long T1ρ component, the fraction of the long T1ρ component, and short T1ρ maps for knee cartilage ROIs only.

Figure 18.

Estimated NLS, RNLS, DL, and HDNLS-based BE long T1ρ component, the fraction of the long T1ρ component, and short T1ρ maps for knee cartilage ROIs only.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of the existing AI-based exponential fitting methods.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of the existing AI-based exponential fitting methods.

| Ref. |

Year |

Method |

Features |

Open Challenges |

| [21] |

2017 |

Monte Carlo simulations and a random forest regressor |

-Established a robust mapping from diffusion-weighted MR signal features to the underlying microstructure parameters of brain tissue.

-Estimated water residence time in brain white matter. |

-Did not estimate multi-component T1ρ map.

-Did not provide uncertainty estimates for predictions.

-Used a very basic representation of white matter. |

| [22] |

2019 |

Deep Neural Network (DNN) |

- Employed non-supervised DNNs to fit the Intravoxel Incoherent Motion (IVIM).

-Does not rely on priors

-Parameter maps were smooth and consistent within homogeneous tissues. |

-DNN may require retraining for different acquisition protocols.

-Training and testing on same data.

-Did not improve Bayesian convergence in low SNR regions. |

| [24] |

2020 |

DNN |

-Used a DNN to directly estimate myelin water fraction (MWF).

-Can produce whole-brain MWF maps in approximately 33 seconds.

-Better voxel-wise agreement was observed between DNN-based MWF estimates and NNLS-based ground truths. |

-DNN relied on NNLS-generated ground truths, so it inherited the NNLS method’s vulnerability to noisy data

-DNN are sensitive to noise and artifacts in the input data |

| [33] |

2019 |

MANTIS |

- Integrated a model-augmented neural network with incoherent k-space sampling for efficient MR parameter mapping.

-Combined physics-based modeling with DL for accelerated image reconstruction.

- Reduced noise and artifacts in reconstructed parameter maps |

-Generalization to diverse datasets may need further validation due to dependency on sampling patterns.

-Performance depends on the quality of its training data, which could lead to overfitting and limited generalizability. |

| [49] |

2020 |

Model-based deep adversarial learning |

-Employed a generative adversarial network (GAN) for enhanced reconstruction quality.

-Achieved rapid parameter mapping with high fidelity and robustness.

-Effectively removed noise and artifacts. |

-Adversarial training is computationally demanding and sensitive to hyperparameter tuning.

-GANs may generate outputs that appear realistic but deviate from the true underlying signal. |

| [50] |

2021 |

MoDL-QSM |

-Combined model-based reconstruction with DL for quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM).

-Used iterative model unrolling with DL modules to improve QSM accuracy.

-Produced high-quality susceptibility maps with reduced streaking artifacts. |

-Model unrolling introduces computational overhead.

-Requires careful hyperparameter optimization to ensure convergence. |

| [51] |

2021 |

DOPAMINE |

integrated model-based and deep learning techniques for fast T1 mapping

Used variable flip angle (VFA) method for efficient data acquisition

Reduced dependency on large training datasets by incorporating physics-based modeling.

Handled noise and artifacts effectively |

-Dependent on specific acquisition protocols (VFA), limiting flexibility for other methods.

-Computationally intensive due to the integration of model-based techniques. |

| [37] |

2021 |

RELAX |

-Utilized two physical models, such as the MR imaging model and the quantitative imaging model, in network training to fit the parameters.

-Eliminated the need for fully sampled reference datasets

-Directly reconstructs MR parameter maps from undersampled k-space data. |

-Tested only on simulated and coil-combined data

-Only a residual U-Net was used

-RELAX's performance relies on the precision of its physical models, limiting its robustness to inaccuracies. |

| [35] |

2023 |

SuperMAP |

-Achieved mapping with acceleration factors up to R = 32.

-Generate relaxation maps from a single scan using optimized data acquisition.

-Directly convert undersampled parameter-weighted images into quantitative maps.

-Performed well on both retrospectively undersampled and prospective data, demonstrating adaptability. |

-Performance relies on the quality and diversity of retrospectively undersampled training data.

-Heavily reliant on the quality of the undersampling patterns, suboptimal patterns may degrade performance. |

| [52] |

2024 |

RELAX-MORE |

-Used self-supervised learning, eliminating the need for large, labeled datasets.

-Unrolled an iterative model-based qMRI reconstruction into a DL framework.

-Produced accurate parameter maps that correct image artifacts, remove noise, and recover features even in regions with imperfect imaging conditions. |

-The unrolling of iterative processes and subject-specific training could still be computationally intensive.

-Subject-specific training might require more careful convergence monitoring, as the self-supervised framework relies on single-subject data. |

Table 2.

Multi-component relaxation models: Mono-Exponential (ME), Bi-Exponential (BE), and Stretched-Exponential (SE).

Table 2.

Multi-component relaxation models: Mono-Exponential (ME), Bi-Exponential (BE), and Stretched-Exponential (SE).

| Model |

Equation |

|

Description |

Range |

|

ME[20,46,47,48] |

|

|

Assumes tissue is homogeneous with a single relaxation time. is the complex-valued amplitude and is the real-valued relaxation time. |

(for knee cartilage ≥ 5 ms) |

| BE [38,39,40] |

|

|

Accounts for two compartments with distinct relaxation times (short) and (long). is the fraction of the long compartment. |

|

| SE [41,42,43] |

|

|

Models heterogeneous environments with distributed relaxation rates. is the relaxation time, and is the stretching exponent. |

|

Table 3.

Features, advantages, and disadvantages of different relaxation models (ME, BE and SE).

Table 3.

Features, advantages, and disadvantages of different relaxation models (ME, BE and SE).

| Model |

Features |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

| ME |

• Fundamental model for single-component relaxation. |

• Simple and easy to implement.

• Suitable for homogeneous tissues with a single relaxation component. |

• Limited in handling tissues with multiple relaxation components. |

| BE |

• Extends the ME model by introducing two compartments (short and long). • Represents two-component decay systems.

• Accounts for two non-exchanging compartments in tissues, each with distinct short and long relaxation times.

|

• Better representation of tissues with two relaxation components, e.g., free water and water bonded to macromolecules. |

• Requires more parameters and is computationally expensive.

• May face convergence issues during fitting.

• The short component is usually sensitive to noise. |

| SE |

• Reduces to ME when β=1. • Can be used as an alternative to BE for describing tissue heterogeneity.

• Can approximate a broad distribution of relaxation rates with fewer parameters, simplifying complex tissue modeling. |

• Suitable for heterogeneous tissues.

• More stable and requires fewer parameters than BE.

• Can describe multi-component relaxation. |

• Less straightforward physical interpretation compared to BE. |

Table 4.

Mathematical Formulations of Performance Metrics Used for Comparative Analysis.

Table 4.

Mathematical Formulations of Performance Metrics Used for Comparative Analysis.

| Metric |

Description |

Equation |

Symbols |

| MNAD |

Measures the median of the normalized absolute difference between estimated and reference T1ρ parameters across voxels. |

|

and are the estimated and reference parameters p of the voxel indexed by i that belongs to the region of interest or set of voxels I, and |

| NRMSR |

Assesses the size of the residual between MR measurements and predicted MR signals. |

|

is the measured MR signal at voxel indexed by i, and isThe predicted MR signal at the same voxel with , and |

| NRMSE |

Assesses the normalized value of the root mean squared error (RMSE) across the reference parameters. |

|

and are the estimated and reference parameters p of the voxel indexed by i that belongs to the region of interest or set of voxels I, and . |

| Fitting Time |

Represents the time required by models (e.g., NLS, RNLS, HDNLS, DL) to compute the T1ρ map for one MRI slice, measured on the same hardware. |

|

Start time of the fitting process. End time of the fitting process |

Table 5.

Quantitative analysis of HDNLS variants for ME, SE, and BE T1ρ maps on real data for full knee joint. Bold quantitative values indicate the outperforming parameter for the specific model.

Table 5.

Quantitative analysis of HDNLS variants for ME, SE, and BE T1ρ maps on real data for full knee joint. Bold quantitative values indicate the outperforming parameter for the specific model.

| Method |

Metric |

Ultra-HDNLS |

Super-HDNLS |

HDNLS |

Relaxed-HDNLS |

| ME |

MNAD (%) |

4.68 |

4.22 |

4.03 |

3.82 |

| Fitting time (sec) |

0.99 |

1.76 |

5.13 |

10.96 |

| NRMSR |

0.03 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

| SE |

MNAD (%) |

13.49 |

8.92 |

7.18 |

6.75 |

| Fitting time (sec) |

1.12 |

1.85 |

3.42 |

7.12 |

| NRMSR |

1.09 |

0.70 |

0.18 |

0.15 |

| BE |

MNAD (%) |

21.38 |

20.26 |

19.87 |

19.24 |

| Fitting time (sec) |

1.22 |

2.14 |

3.96 |

7.73 |

| NRMSR |

0.03 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

Table 6.

Quantitative analysis of HDNLS variants for ME, SE, and BE T1ρ maps on real data for knee cartilage ROI only. Bold quantitative values indicate the outperforming parameter for the specific model.

Table 6.

Quantitative analysis of HDNLS variants for ME, SE, and BE T1ρ maps on real data for knee cartilage ROI only. Bold quantitative values indicate the outperforming parameter for the specific model.

| Method |

Metric |

Ultra-HDNLS |

Super-HDNLS |

HDNLS |

Relaxed-HDNLS |

| ME |

MNAD (%) |

4.36 |

4.16 |

3.86 |

3.74 |

| Fitting time (sec) |

0.52 |

0.95 |

2.38 |

5.73 |

| NRMSR |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

| SE |

MNAD (%) |

13.24 |

8.73 |

7.12 |

6.67 |

| Fitting time (sec) |

0.51 |

0.87 |

2.28 |

3.71 |

| NRMSR |

1.09 |

0.70 |

0.18 |

0.14 |

| BE |

MNAD (%) |

20.34 |

19.77 |

19.28 |

18.94 |

| Fitting time (sec) |

0.46 |

0.87 |

1.85 |

3.26 |

| NRMSR |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

Table 8.

Quantitative analysis of NLS, RNLS, DL, and HDNLS for ME, SE, and BE T1ρ maps on real data for both full knee joint and knee cartilage ROI only.

Table 8.

Quantitative analysis of NLS, RNLS, DL, and HDNLS for ME, SE, and BE T1ρ maps on real data for both full knee joint and knee cartilage ROI only.

| Method |

Metric |

Full Knee |

Knee Cartilage |

| DL |

HDNLS |

DL |

HDNLS |

| ME |

MNAD (%) |

22.36 |

18.93 |

19.32 |

17.20 |

| NRMSE (%) |

24.05 |

21.25 |

21.20 |

19.31 |

| SE |

MNAD (%) |

26.38 |

23.94 |

23.38 |

21.64 |

| NRMSE (%) |

25.81 |

22.94 |

22.46 |

19.85 |

| BE |

MNAD (%) |

17.70 |

13.02 |

14.09 |

12.24 |

| NRMSE (%) |

20.16 |

16.36 |

18.37 |

14.85 |

Table 9.

Computational speed analysis of NLS, RNLS, DL, and HDNLS for ME, SE, and BE T1ρ maps on real data for both full knee joint and knee cartilage only.

Table 9.

Computational speed analysis of NLS, RNLS, DL, and HDNLS for ME, SE, and BE T1ρ maps on real data for both full knee joint and knee cartilage only.

| Method |

Metric |

NLS |

RNLS |

DL |

HDNLS |

| ME |

Full Knee |

274.68 |

234.22 |

1.35 |

19.32 |

| Knee Cartilage |

76.37 |

65.82 |

0.92 |

6.78 |

| SE |

Full Knee |

293.49 |

262.92 |

1.78 |

22.50 |

| Knee Cartilage |

91.12 |

88.39 |

1.67 |

7.51 |

| BE |

Full Knee |

257.38 |

229.13 |

1.21 |

18.14 |

| Knee Cartilage |

70.26 |

67.14 |

0.84 |

6.13 |