1. Introduction

Surgical site infection (SSI) in elective orthopedic foot and ankle surgery are frequent complications ranging from 1.9% up to 4.2% [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5], or 9.4% respectively [

2]; including for patients with concomitant diabetes mellitus [

1]. Serum inflammatory markers such as the C-reactive protein (CRP) are widely used as a supplementary tool in the therapeutic follow-up of infected patients, next to the clinical diagnosis and its microbiological (and histological) confirmation of infection, although no clinical thresholds exist on that matter. The infectious diseases experts emphasize that no therapeutic decision depends on the serum CRP level

per se. The reasons for this surgical tradition may be to monitor of a good evolution, to estimate a prognosis, or the anticipation of problems. The scientific benefit remains unclear, since the clinical evaluation provides all the information needed; and the CRP peak always lags behind by two days after the triggering event [

6,

7].

Undoubtfully, postoperative CRP levels can correlate with new problems such as progredient ischemia, fracture, or thrombosis, but the CRP does not really help whenever these problems are recognized visually. On the contrary, in cases of a surprisingly elevated CRP, the responsible clinicians may perform unnecessary radiological and laboratory exams (X-rays or even Magnetic Resonance imaging (MRI), superficial microbiological wound swabs, urinary cultures); all of which ultimately increase cost or lead to a precautional antibiotic use without benefits for the patients.

Several studies have highlighted the limitations of these routine (control) and iterative CRP monitoring in orthopedic surgery [

8,

9,

10]. Specifically, regarding the ischemic and implant-free community-acquired diabetic foot infections (DFI), Pham et al. denied the utility of such routine CRP measurement during antibiotic therapy for DFI, as it fails to predict treatment failures [

9] Similarly, Furrer et al. found no benefits of other routine serum laboratory controls (leukocytosis, platelets and CRP) in the practical management of operated, community-acquired DFIs [

10]. In both studies, the CRP reflected both, the infection, and a large part of non-infectious postoperative inflammation.

In this actual study, we evaluate this widespread practice of CRP sampling in adult orthopedic patients with SSI in non-ischemic diabetic) orthopedic foot surgery. Importantly, we do not aim to associate a high postoperative CRP level with various complications such as thrombosis, ischemia, new infections, mortality or fractures, for which a broader literature is available [

11]. By focusing on acute SSIs, we limit the CRP reasons to its infectious parts and question the utility of a routine CRP monitoring in anticipating therapeutic failures. We believe that our findings could significantly impact clinical practice by reducing futile testing and (antibiotic) costs, without compromising outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

We retrospectively analyzed all SSI after elective (diabetic) foot surgery in our tertiary (diabetic) foot center at the Balgrist University Hospital in Zurich, Switzerland, from January 2014 to August 2022 [

1]. We used data mining from the hospital’s own medical databases and confirmed the presence of SSI by controlling the electronic files. We included all SSI (first time episode) in adult elective foot and ankle surgeries in our patients older than 18 years with a minimum surveillance of two years after the start of therapy; and with detailed information available during database closure (August, 31st 2024).

2.1. Study Definitions, Costs and Criteria

The definition of SSI based on international criteria [

1,

2,

3,

4,

12]. Exclusion criteria were described in a previous study [

1] and briefly resumed as recurrent infections, amputations without residual infection, infection episodes with prior emergency index surgery, external patients that we treated only partially, open fractures, foot infections extending beyond the ankle (e.g. gas gangrene, necrotizing fasciitis and other rapidly spreading severe soft tissue infection), insufficient documentation, atypical pathogens such as

Actinomyces spp., fungi or mycobacteria, concomitant severe and remote infections such as endocarditis or brain abscesses, and, most importantly, the presence of a community-acquired DFI with ischemia, infected foot ulcers, and/or severe neuropathy. In contrast, a patient with a well-regulated concomitant diabetes mellitus was allowed to be included in the study if he/she had developed a non-ischemic SSI [

1]. We equally excluded all cases with any postoperative complication during SSI. Postoperatively, the CRP measurement and its timing were at the discretion of the treating surgeons. One CRP sample costs approximatively 10 Swiss Francs, equaling 10 US

$. A CRP value <10 mg/L was considered as normal according to our laboratory (ZLZ; Zentral Labor Zürich). We avoided intraarticular CRP measurements.

2.2. Statistical Analyses

The primary outcome was remission, and/or inversely failure, after the End of Treatment for SSI after orthopedic (diabetic) foot surgery. The secondary outcomes were dynamic changes of the CRP during therapy. For group comparisons we used the Pearson-χ

2 or the Wilcoxon-ranksum-test. For the large case-mix and to compare the different CRP values within the entire inhomogeneous study population, we performed a multivariate unconditional logistic regression analyses with the outcome “Failure”. We included 5-8 predicter variables per number of outcome variable. As this was a side study of a prior publication [

1], we had no formal sample size requirements. We used STATA

™ software (Version 15.0; College Station, Texas, USA).

P-values <0.05 (two-tailed) were significant.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

We retrospectively analyzed a cohort of foot surgeries between 1st January 2014 and 31th August 2022 [

1]. Overall, we assessed 6138 elective surgeries with an overall SSI risk of 1.88%. For the final analysis, we kept 36 SSI cases in 36 different adult foot patients with complete data. The median age was 60 years (interquartile range (IQR), 48-77 y), and fifteen patients were female (42%). The median body mass index was 28.7 kg/m

2 (IQR, 24-33) and the number of co-morbidities was high (diabetes n=5, sarcoidosis n=1, rheumatic arthritis n=1. Half of the patients (18/36; 50%) yielded an American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Score over 2 points and 5 (14%) a superinfected Charcot foot arthropathy. The median length of hospital stay in acute care surgery was 12 days (IQR, 7-19 d).

3.2. Surgical Site Infections, Pathogens, Therapies and Outcomes

We detected sixteen different microbiological SSI constellations, of which one third was polymicrobial (12/36; 33%). The both most frequent mono-infections were due to

Staphylococcus aureus (17%) and

S. epidermidis (6%). Two-thirds (67%) of the SSI involved bone and in seven cases (19%), the infected (or contaminated) implant was left in situ. Among 36 different antibiotic regimens, the bulk of antimicrobial therapy was orally. Intravenous agents were applied during only the initial postoperative days. We equally renounced on using local (intraosseous) antimicrobial deliveries [

13] or topical superficial agents [

13], as they were reserved for recurrent and/or ulcerated foot infections. The median duration of postoperative antibiotic use was 42 days (IQR, 27-84 days) and determined by Infectious Diseases Physicians with experience in orthopedic infections. The three most frequently used antibiotics were co-amoxiclav, clindamycin and co-trimoxazole. The median number of surgical debridement for infection was 1 (IQR, 1-2 debridement). The surgical management was supported by use of casts in 12 (33%) episodes, postoperative wounds with negative-pressure devices [

15] in eight (22%) cases, and partial off-loading in all episodes. In terms of treatment outcomes, 29 out of 36 patients (80.56%) achieved full remission and remained in remission after a median active surgical follow-up time of 4.3 years (IQR, 2.6-6.6 y). Seven episodes (19%) failed at the same anatomical localization, but eventually with new pathogens. None of them yielded a microbiologically-identical infectious relapse with the same pathogen(s) as in the index infection.

3.3. C-Reactive Protein Levels Associated to Outcomes

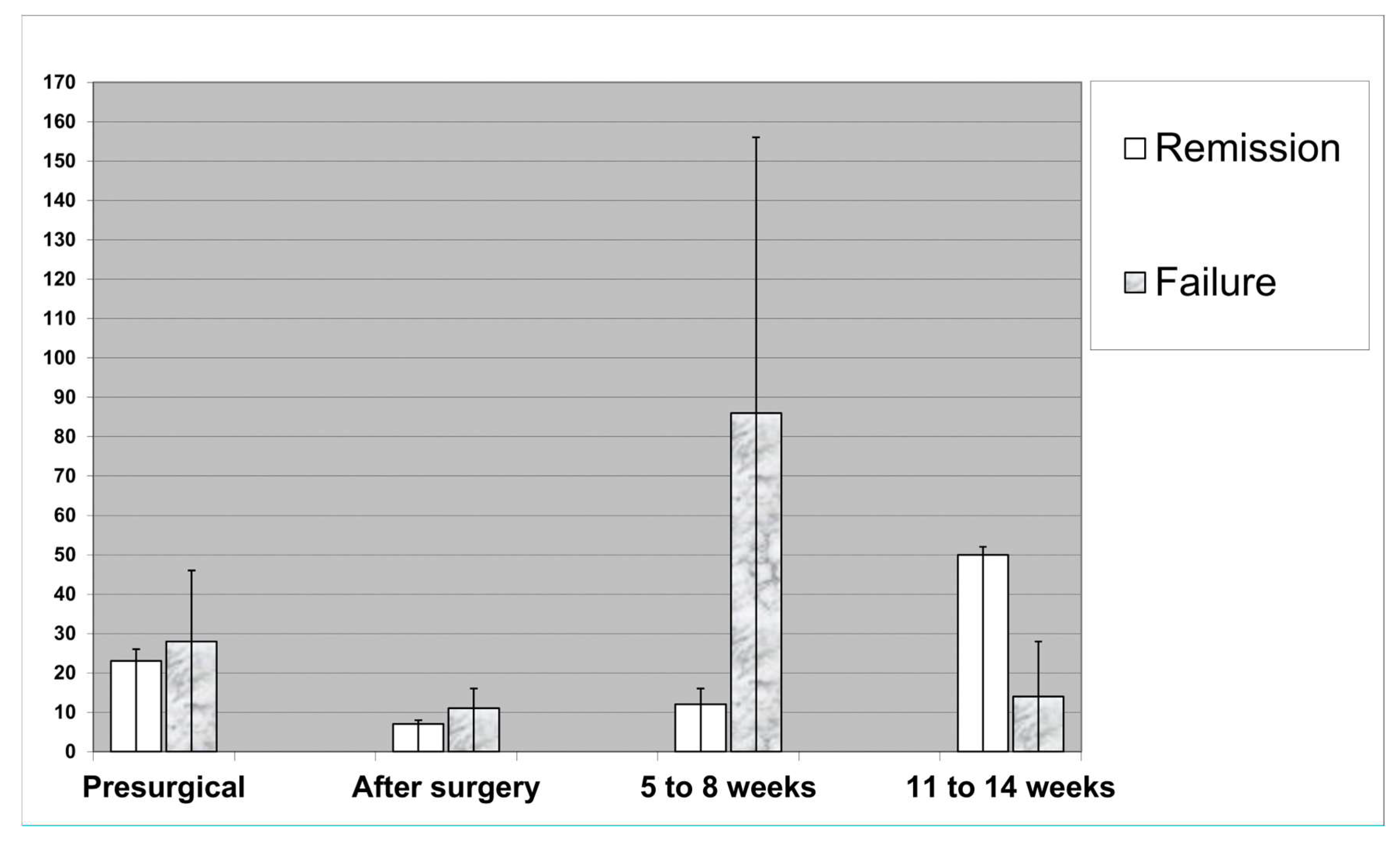

Overall, the median preoperative CRP levels were 25 mg/L (IQR, 8-48 mg/L). The postoperative median CRP levels on Days 6-13 were 8.9 mg/L (IQR, 4-22 mg/L). The median CRP levels on Weeks 5 to 8 were 28.2 mg/L (IQR, 8-70 mg/L). The median CRP levels on Weeks 11 to 14 were 37.5 mg/L (IQR, 11-93 mg/L). The median relative drop (ratio) of the CRP values between the presurgical values and the first postoperative levels was 75% (IQR, 1%-94%). At the end of therapy, five patients (14%) could not normalize their CRP levels to baseline and/or ≤ 10 mg/L; however, without continuing the antibiotics.

Table 1 compares key variables and serum CRP levels between remissions and failures.

The CRP levels showed a very large dispersion and variance, both between the individual patients and over time for a given SSI episode (

Figure 1). Whereas the immediate drop after surgery was parallel between the groups of “Remission” and “Failure”, the further course became much more aleatory. For example, at Week 5 to 8, the CRP levels seemed more dispersed among those who failed (with the occurrence of important outliers), the situation was even inversed at week 11 and 14 when the local visual aspects "calmed down"(

Figure 1). However, as a clinical consequence, the medical records indicate a high medical activity after the detection of a unsurprisingly high CRP values. For example, these values were contributing in delaying the postsurgical transfer to a rehabilitation center, or postponing the change from parenteral to oral antibiotic prescription; or performing unplanned and costly examinations such as urine cultures in asymptomatic patients, unplanned X-rays or other radiological examinations for the exclusion of hidden abscesses, and, eventually, might even prolong the individual length of hospital stay. As a strict minimal consequence of a surprising finding, high CRP values motivated for consecutive sampling, increasing at least the costs of laboratory examinations.

3.4. Multivariate Adjustment

Due to the large case-mix, we adjusted with a logistic regression analysis and its outcome “treatment failure”. In this multivariate analysis, the pre- and postsurgical CRP values oscillated around an odds ratio of 1.0. The 95% confidence intervals were narrow (

Table 2), the goodness-of-fit-test insignificant, and the Receiver under the Curve (ROC) value 0.83; representing a more than adequate accuracy of our final statistical model. These results represent a very limited influence of the iterative CRP on the ultimate fate of therapy.

4. Discussion

We cannot display a significant association of routine, singular or serial, serum CRP samplings in the aftermath of surgical debridement for orthopedic foot SSIs. Our results are in line with our own clinical experience and underlines by experts in orthopedic Infectious Diseases. Existing literature almost exclusively investigates the accuracy of the serum CRP in the diagnosis of a suspected infection; which is beyond the topic of our study. Rarely, serial serum CRP controls have been investigated in orthopedic surgery.

There are very few prospective studies examining the performance of iterative CRP measures during the follow-up of already infected orthopedic patients. Dupont et al. sampled different serum inflammatory markers after one week, three weeks, and three months of treatment [

6]. All values declined after initiation of antibiotics. The serum CRP values returned to near-normal levels at Day 21. However, it remained unclear what was the clinical benefit of the routinely CRP monitoring (or what would have missed by clinical evaluation alone) [

6]. To cite another clinical example, a French study monitored arthroplasties. The authors concluded that a clinical, local visual discharge, a fever >38°C and local/persistent pain were more informative indicators of postoperative infection complications than the measured evolution of the CRP [

16]. In another British study with 260 infected arthroplasties, the serial sampling of 3732 serum CRPs turned out to be a very poor predictor of general outcome and, thus, not recommended by the authors themselves [

17]. Of note, their area-under-the-ROC curves for CRP levels predicting a good outcome, only ranged from 0.55 to 0.65; which performed only slightly better than the coin [

17]. A German group compared the diagnostic value of serum CRP and the serum white blood cell (WBC) count during a two-stage revision surgery of infected hip arthroplasties. The postoperative courses of the mean CRP values were similar between those who remained reinfection-free or witnessed a re-infection [

18]. The authors concluded that the CRP and WBC count are not helpful to guide decision making in individual cases [

18]. In the elderly DFI population, the quantitative serum CRP is dynamic and influenced by many inherent co-morbidities such as gout, cancer, rheumatic diseases, thrombosis, statin drugs, Charcot foot arthropathy [

19], hematoma, ischemia, dialysis, cirrhosis, trauma, obesity, or postoperatively [

9,

20]. Furthermore, the CRP peak always lags 2-3 days behind the event with a long recovery time; making its timely interpretation impracticable [

7,

21].

The CRP level

per se is not decisive or predictive enough to change an antibiotic treatment, or to prolong a scheduled therapy principally basing on its values. The serum CRP is probably not better than the clinical surgical decisions, e.g. regarding a second look. In contrast, the routine sampling of the serum CRP has a high potential to cause unexpected troubles. At a minimum, many clinicians become disturbed by surprisingly high laboratory finding and often recur to additional examinations; e.g. bacterial urine culture in asymptomatic patients, X-rays or other costly examinations to exclude hidden abscesses (local or remote ones) or thrombosis, embolism. Besides new examinations and the compulsory repetition of CRP sampling, the clinical consequences are diverse. Sometimes, clinicians might delay the hospital discharge or the transfer to rehabilitation, only for precautional surveillance and hoping to know what happens. Or they might delay the planned switch from intravenous to oral antibiotic therapy; hoping that a parenteral treatment would decrease the control CRP values faster than oral agents [

22]. In the worst case, they (empirically) broaden the antibiotic spectrum; especially in polymicrobial DFIs. In the best case, they require an Infectious Diseases’ consultation [

23], which they would not have done for the same patients if his/her CRP levels were low. The authors of this article strongly advocate to abandon (to de-implement entirely) the routine serum CRP measures during the treatment of infected orthopedic patients for routine purposes.

Our study has a major strength and several limitations. We focus on uneventful postoperative courses after the first debridement for SSI; without new events that might mix up the indications of CRP measurement for new complications such as lung embolism, ischemia (especially in the diabetic foot), or nosocomial urinary tract infections [

24]. The major limitations are the retrospective nature of our study. A randomized-controlled trial, assessing the decisional benefit of the routine, would link the antibiotic stop in orthopedic patients with the normalization of the serum CRP. We ignore if any trial in the orthopedic field would investigate this. In many other fields of Infectious Diseases, the stop of systemic antibiotic use after the achievement CRP normalization is debated since decades and research regularly denies its practicability or benefit. For instance, according to the latest trial in Gram-negative bacteremia, the investigators randomized adult hospitalized patients receiving microbiologically efficacious antibiotic(s) between 14 days of antibiotic therapy, 7 days of therapy, or an individualized duration determined by clinical response and a 75% reduction in peak CRP values [

25]. Preliminary results indicate no differences between all three randomization arms. Generally speaking, in orthopedic infections, the total duration of antibiotic treatment is determined by expert opinion and few randomized data, and not on a single laboratory parameter.

Secondly, we sampled the serum CRP. Our findings cannot apply to other inflammatory markers such as pro-calcitonin [

9], the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, interleukins 2, 6 or 8, serum leukocyte counts, tumor necrosis factors, monocyte chemotactic proteins, macro-phage inflammatory proteins, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratios, procollagen type 1 N pro-peptides, high-resolution CRPs or genetically altered CRP peptides [

26]. These latter markers are very seldomly used in daily clinical practice and all are more expensive than the standard CRP [

9].

Lastly, we investigated the pertinence of serial serum CRP levels in infected foot patients. There are also surgical groups that measure in (not yet) infected orthopedic surgeries (especially in arthroplasties [

17]), which is a distinct entity. Follow-up CRP measurements during treatment are informative, but complete normalization is not a mandatory requirement for successful outcome [

27,

28], while, in turn, a normalized C-reactive protein does not rule out chronic periprosthetic joint infections [

29].

5. Conclusions

According tom our single-center composite foot database and two analogue studies [

9,

10] in the diabetic foot, routine CRP samples, at different time points during ongoing therapy for operated SSI in orthopedic foot surgery, failed to predict failures during and after therapy. This practice should be abandoned, because the unnecessary samples are waste of money, inutile phlebotomies for patients and nurses, excessive work-ups, delays in patient transfers, and delayed switch to (more convenient) oral antibiotic medication.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.S.-B. and I.U.; methodology, L.S.-B.; formal analysis, L.S.-B.; investigation, L.S.-B., I.U., R.P.F. and I.Y.; resources, A.V. , P.J. , I.Y., P.R.F. and S.W..; data curation, L.S.-B. , P.J., I.Y. and I.U.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L. and I.U.; writing—review and editing, J.L., P.J., I.U, A.V., and S.W.; visualization, J.L. L.S.-B., I.U, I.Y., A.V, S.W., and I.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific funding. L.S.-B. was supported with a grant from the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (FPU (18/02768)) and by a mobility grant provided from the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee of Zurich (BASEC 2022-01755 on 28.10.2022).

Informed Consent Statement

A general informed consent had been obtained from all patients involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

We might provide anonymized key variables upon a justified scientific request to the last author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank to the Unit for Clinical Applied Research (UCAR; Ms. Nathalie Kühne and Ms. Corina Früh) for providing the necessary resources for the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Soldevila-Boixader, L.; Viehöfer, A.; Wirth, S.; Waibel, F.W.A.; Yιldιz, I.; Stock, M.; Jans, P.; Uçkay, I. Risk Factors for Surgical Site Infections in Elective Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Surgery: The Role of Diabetes Mellitus. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modha, M. R. K.; Morriss-Roberts, C.; Smither, M.; Larholt, J.; Reilly, I. Antibiotic prophylaxis in foot and ankle surgery: a systematic review of the literature. J Foot Ankle Res 2018, 11, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhães, J. M.; Zambelli, R.; Oliveira-Júnior, O.; Avelar, N. C. P.; Polese, J. C.; Leopoldino, A. A. O. Incidence and associated factors of surgical site infection in patients undergoing foot and ankle surgery: a 7-year cohort study. Foot (Edinb) 2024, 59, 102092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, J.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, T.; Zhang, F.; Qin, S.; Zhao, H. Incidence and risk factors for surgical site infection following elective foot and ankle surgery: a retrospective study. J Orthop Surg Res 2020, 15(1), 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tantigate, D.; Jang, E.; Seetharaman, M.; Noback, P. C.; Heijne, A. M.; Greisberg, J. K.; Vosseller, J. T. Timing of Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Preventing Surgical Site Infections in Foot and Ankle Surgery. Foot Ankle Int 2017, 38(3), 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michail, M.; Jude, E.; Liaskos, C.; Karamagiolis, S.; Makrilakis, K.; Dimitroulis, D.; Michail, O.; Tentolouris, N. The Performance of Serum Inflammatory Markers for the Diagnosis and Follow-up of Patients With Osteomyelitis. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2013, 12, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uçkay, I.; Garzoni, C.; Ferry, T.; Harbarth, S.; Stern, R.; Assal, M.; Hoffmeyer, P.; Lew, D.; Bernard, L. Postoperative serum pro-calcitonin and C-reactive protein levels in patients with orthopedic infections. Swiss Med Wkly 2010, 140, 13124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.H.; Ahmed, S.; Barakat, A.; Mangwani, J.; White, H. Inflammatory response in confirmed non-diabetic foot and ankle infections: A case series with normal inflammatory markers. World J Orthop 2023, 14(3), 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.; Wetzel, O.; Gariani, K.; Kressmann, B.; Jornayvaz, F.R.; Lipsky, B.A.; Uçkay, I. Is routine measurement of the serum C-reactive protein level helpful during antibiotic therapy for diabetic foot infection? Diabetes Obes Metab 2021, 23(2), 637–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furrer, P.R. , Schömni, M.; Waibel, F.W.A.; Berli, M.C.; Lipsky, B.A.; Uçkay, I. Lack of Benefit of Routine Serum Laboratory Control Samples during Treatment of Diabetic Foot Infection. Arch Microbiol Immunology 2022, 6(1), 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Jung, Y.C.; Jeon, D.O.; Cho, H.J.; Im, S.G.; Jang, S.K.; Kang, H.J.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, J.H. High serum C-reactive protein level predicts mortality in patients with stage 3 chronic kidney disease or higher and diabetic foot infections. Kidney Res Clin Pract 2013, 32, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horan, T.C.; Gaynes, R.P.; Martone, W.J.; Jarvis, W.R.; Emori, T.G. CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections, 1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. Am J Infect Control 1992, 20(5), 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldevila-Boixader, L.; Fernández, A.P.; Laguna, J.M.; Uçkay, I. Local Antibiotics in the Treatment of Diabetic Foot Infections: A Narrative Review. Antibiotics (Basel) 2023, 12(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uçkay, I.; Kressmann, B.; Malacarne, S.; Toumanova, A.; Jaafar, J.; Lew, D.; Lipsky, B.A. A randomized, controlled study to investigate the efficacy and safety of a topical gentamicin-collagen sponge in combination with systemic antibiotic therapy in diabetic patients with a moderate or severe foot ulcer infection. BMC Infect Dis 2018, 18, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, S.; Çιkιrιkcιoğlu, M.; Uçkay, I.; Kalangos, A. Comparison of negative-pressure-assisted closure device and conservative treatment for fasciotomy wound healing in ischaemia-reperfusion syndrome: preliminary results. Int Wound J 2011, 8(3), 229–236. [Google Scholar]

- Dupont, C.; Rodenbach, J.; Flachaire, E. The value of C-reactive protein for postoperative monitoring of lower limb arthroplasty. Ann Readapt Med Phys 2008, 51, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejon, P.; Byren, I.; Atkins, B.; Scarborough, M.; Woodhouse, A.; McLardy-Smith, P.; Gundle, R.; Berendt, A.R. Serial measurement of the C-reactive protein is a poor predictor of treatment outcome in prosthetic joint infection. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011, 66, 1590–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mederake, M.; Hofmann, U.K.; Benda, S.; Schuster, P.; Fink, B. Diagnostic Value of CRP and Serum WBC Count during Septic Two-Stage Revision of Total Hip Arthroplasties. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hingsammer, A.M.; Bauer, D.; Renner, N.; Borbas, P.; Böni, T.; Berli, M.C. Correlation of Systemic Inflammatory Markers With Radiographic Stages of Charcot Osteoarthropathy. Foot Ankle Int 2016, 37, 924–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund Håheim, L.; Nafstad, P.; Olsen, I. C-reactive protein variations for different chronic somatic disorders. Scand J Public Health 2009, 37, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, S.; Kushner, I.; Samols, D. C-reactive Protein. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 48487–48490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sendi, P.; Lora-Tamayo, J.; Cortes-Penfield, N.W.; Uçkay, I. Early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotic treatment in bone and joint infections. Clin Microbiol Infect 2023, 29(9), 1133–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uçkay, I.; Vernaz-Hegi, N.; Harbarth, S.; Stern, R.; Legout, L.; Vauthey, L.; Ferry, T.; Lübbeke, A.; Assal, M.; Lew, D.; Hoffmeyer, P.; Bernard, L. Activity and impact on antibiotic use and costs of a dedicated infectious diseases consultant on a septic orthopaedic unit. J Infect 2009, 58, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansorge, A.; Betz, M.; Wetzel, O.; Burkhard, M.D.; Dichovski, I.; Farshad, M.; Uçkay, I. Perioperative Urinary Catheter Use and Association to (Gram-Negative) Surgical Site Infection after Spine Surgery. Infect Dis Rep 2023, 15(6), 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huttner, A.; Albrich, W.C. ; Bochud, P-Y.; Gayet-Agéron, A., Rossel, A., von Dach, E., Harbarth, S., Eds.; Kaiser, L. PIRATE project: point-of-care, informatics-based randomised controlled trial for decreasing overuse of antibiotic therapy in Gram-negative bacteraemia. BMJ Open 2017, 7 (7), 017996. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Xu, H.; Zhou, N.; Zhao, W.; Wu, D.; Shen, B. Combined Effects of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) within C-reactive Protein (CRP) and Environmental Parameters on Risk and Prognosis for Diabetic Foot Osteomyelitis Patients. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2020, 28(8), 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.; Soares, D.; Aido, R.; Sousa, R. The value of monitoring inflammatory markers after total joint arthroplasty. Hard Tissue 2013, 2(2), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohe, S.; Böhle, S.; Matziolis, G.; Jacob, B.; Wassilew, G.; Brodt, S. C-reactive protein during the first 6 postoperative days after total hip arthroplasty cannot predict early periprosthetic infection. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2023, 143(6), 3495–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, B.; Schlumberger, M.; Beyersdorff, J.; Schuster, P. C-reactive protein is not a screening tool for late periprosthetic joint infection. J Orthop Traumatol 2020, 21(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).