1. Introduction: AR in Fashion and Textile Retail

Augmented Reality (AR) technology has been increasingly utilised in retail due to advancements in the telecommunication industry, which have reduced device prices and enabled widespread AR access through smartphones [

1]. The relatively low cost of AR implementation compared to other immersive technologies like Virtual Reality (VR) has further accelerated this adoption [

2]. AR is traditionally defined as a real-time, direct, or indirect view of a physical, real-world environment enhanced by virtual, computer-generated information [

3]. This enhancement is always mediated through an electronic device, providing an augmented experience to the user. While AR applications span various retail fields, including furniture [

4] and electronics [

5], this discussion focuses on the fashion and textile industries.

In the fashion and textile sector, the primary objectives of using AR have been to enhance the shopping experience for consumers, reduce uncertainties and product risk perceptions, assist consumers with their purchase decisions, increase store attractiveness, brand engagement, and intentions to visit and recommend the store [

6]. AR is considered an effective technology for remote shopping in-store and online shopping experiences. It supports consumers’ mental intangibility via realistic product presentations and interaction possibilities that can produce several different cognitive, affective, and behavioural outcomes. Previous research highlights the application of AR in branding and marketing, emphasising its role in engaging customers through emotional interactions and establishing brands as technologically innovative and creative [

7]. AR applications, such as virtual try-ons and smart mirrors, have improved conversion rates and reduced return rates by allowing consumers to realistically visualise products, thereby increasing their confidence in purchasing them [

2,

8]. Furthermore, AR improves after-sale customer services by providing complementary product-related information in context, which increases customer satisfaction and loyalty [

9]. In workflow management, AR is employed in warehouse planning and order picking, increasing logistics operations’ efficiency and accuracy [

10].

AR has shown the potential to extend the lifespan of materials by offering after-purchase information and helping consumers make better purchase decisions through product visualisation [

11]. However, its primary goals are centred around boosting sales and driving consumption rather than intentionally supporting the principles of the Circular Economy (CE) [

12]. CE strives to minimise waste and optimize resource use, but AR applications in the fashion and textile industries have not fully integrated these principles.

An AR application that incorporates and promotes circular practices by design can be a valuable asset for brands that want to strengthen their sustainability strategies. For fashion and textile consumers, this tool can help them better understand and value the materials and processes that make their clothes, emphasise the importance of circular practices, and how they can be part of a fashion and textile CE.

This paper will demonstrate the use of AR to connect fashion and textile consumers with the materials and techniques used to construct their clothes. For this purpose, first, a conceptual model that suggests the promotion of circularity through material knowledge will be proposed. Next, the methodology of development and analysis of the AR tool that follows this conceptual model will be explained, and the study will be analysed. The final section will present the discussion, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

The contribution of this paper is threefold. First, it introduces the Biofibre Explorer, an AR tool designed to enhance consumer understanding of biobased textiles by visualising the wet spinning process. Unlike existing AR applications in fashion, which primarily focus on retail engagement and product visualisation, this tool reorients AR towards sustainability education, bridging the knowledge gap between consumers and circular material innovations. Second, it expands the application of the [Anonymised Theoretical Framework] by integrating AR with key dimensions such as Enjoyment & Pleasure, Playfulness, Bodily & Sensory, Learning, and Future-self. Third, the paper contributes empirical insights into the design and evaluation of AR for material storytelling, offering practical design guidelines based on user studies conducted in real-world settings. These insights can inform future developments in AR-driven consumer experiences for fashion, textiles, and other material-intensive industries.

2. Promoting Circularity Through Material Knowledge

The transition to a circular textile economy requires a range of interconnected activities. Research from the

[Centre name removed for anonymity] argues that a successful shift to circularity in the fashion and textile industries can benefit from strategies that align human wellbeing with material resource flow

([publication Anonymised for review]). This alignment can be structured through the

[Anonymised Theoretic Framework for review]. The

[Anonymised Theoretic Framework for review] is a holistic model that integrates hedonic (short-term pleasure) and eudaimonic (long-term fulfilment) aspects of well-being within the circular textile economy. It comprises three overarching elements: Feeling Well, Doing Well, and Being Well, encompassing 16 interconnected dimensions. In this article, we focus on how the well-being factors of learning, attachment, competence, playfulness, and future-self were applied to create the AR Biofiber Explorer—a tool designed to enhance consumer interaction with and understanding of bio-based materials. These concepts, summarised in

Table 1, are part of the

[Anonymised Theoretic Framework for review]. For a more detailed account of the framework, see

[publication Anonymised for review].

One way to support circular practices in fashion and textile retail is through experiences that reconnect consumers with the different stages of the life cycle of their clothing, including origin, production and performance. Consumers often lack knowledge about the materials used in their clothing, a gap that significantly limits informed material choices and negatively impacts purchasing decisions [

13]. This limited awareness has negative implications for meaning-making and the creation of value. For instance, previous research found that when consumers become aware of the components and labour involved in producing a shirt, they are more likely to appreciate the garment and adopt better care practices (

[Anonymised publication], in preparation). This disconnection is further complicated by introducing new bio-based materials as an alternative to conventional textiles. Biobasedmaterials have the potential for a smaller carbon footprint and more sustainable fabrication methods [

14]. However, many new circular bio-based materials are still in the research and development phase. Also, when these materials enter the market, they often come at a higher price point and may not match traditional textiles’ performance. For consumers to consider these circular bio-based materials as viable alternatives, they need to understand the environmental significance and the extensive research and development invested in their creation [

15]. By bridging this knowledge gap, consumers can better appreciate bio-based materials as sustainable options, making them more likely to prioritise these alternatives in their purchasing decisions now and in the future.

For circular bio-based materials to gain broader acceptance and thus contribute more to reducing environmental impact, consumers must appreciate their value and understand how they contribute to a better textile economy. This calls for a shift in consumer perception—moving beyond cost and immediate performance comparisons to a more holistic recognition of the long-term benefits of a circular fashion and textile industry [

16].

The AR Biofiber Explorer aims to reconcile consumer knowledge and sustainable material practices, making bio-based materials more understandable and desirable in the market and empowering consumers with the knowledge they need to make better material choices when purchasing a garment. This approach in consumer experience design contributes to a variety of strategies necessary for transitioning to a circular fashion and textile industry and promoting sustainable consumption [

17]. Our approach is meaningful for consumers both materially and experientially, driving broader engagement and long-term (eudaimonic) satisfaction.

3. Current Ways to Help Consumers Make Meaning Around New Materials

One effective method for communicating material properties is through material narratives, which utilise storytelling techniques and play a critical role in fostering material acceptance [

18,

19]. Material narratives enable designers, companies, and consumers to understand the materials conceptually before physically interacting with them, especially in cases where material samples are not readily accessible. Rognoli et al. [

20] introduced the concept of materials biography to communicate and explore the lifecycle, origins, processes, temporality, and identity of new materials. This approach enhances the understanding of bio-based and bio-fabricated materials, enabling designers, manufacturers, and consumers to appreciate their unique qualities and sustainability potential. Additionally, there appears to be a link between knowledge of how garments are made and the value attributed to the material or finished product (

[Title Anonymised for review], in preparation).

In a case study on how biobased material development companies communicate their innovations, D’Olivo and Karana [

21] introduced the concept of material framing as a strategy to accelerate the adoption of new bio-based materials. They identified three key categories companies use to frame their products: material origins, fabrication processes, and material outcomes.

While these approaches enhance the understanding and appreciation of bio-based materials, they would benefit from a clearer connection with human wellbeing, as proposed by the [Anonymised Theoretical Framework]([Anonymised publication], forthcoming). This gap is critical, as meaningful consumer engagement with materials should not only inform but also enrich consumer’s wellbeing and foster authentic connections with circular practices. The significance of integrating consumer experience with human wellbeing is further discussed in [Anonymised Theoretical Framework]([Anonymised publication], forthcoming).

Building on these existing storytelling strategies and aligning them with the [Anonymised Theoretical Framework ]([publication Anonymised for review], forthcoming), we developed the AR Biofibre Explorer. In the following section, we outline the design process behind this application.

4. Methodology

The research methodology followed a structured, multi-phase approach to develop and evaluate an AR tool to enhance consumer understanding of bio-based textiles. We hypothesise that improving people’s knowledge of bio-based materials’ origins, uses, and qualities contributes to purchasing decisions more aligned with human and planetary wellbeing. First, a literature review on the use of AR within fashion and textiles, alongside consumer behaviour insights from the [Anonymised research platform], informed the design of the initial prototype. The [Anonymised research platform] is an innovative "living lab" and speculative retail environment designed to explore sustainable fashion consumption. It offers alternative circular consumer experiences—such as interactive stations for material exploration, co-design, and garment repair—explicitly crafted to enhance human wellbeing while promoting circular textile practices, linking personal and collective wellness with sustainable material use throughout a garment’s lifecycle.

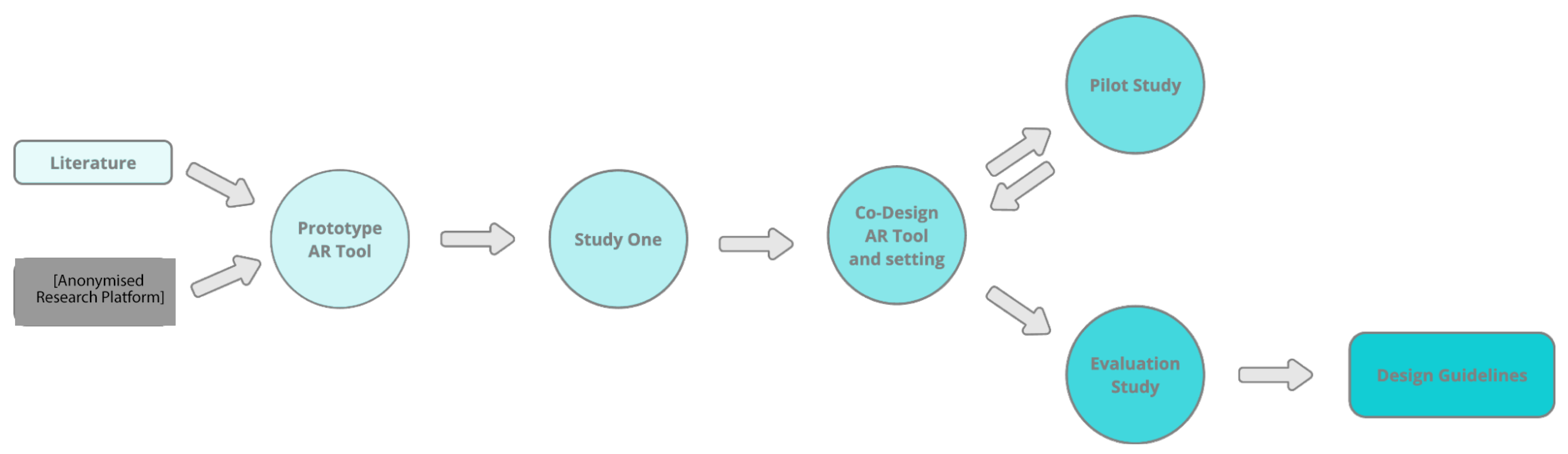

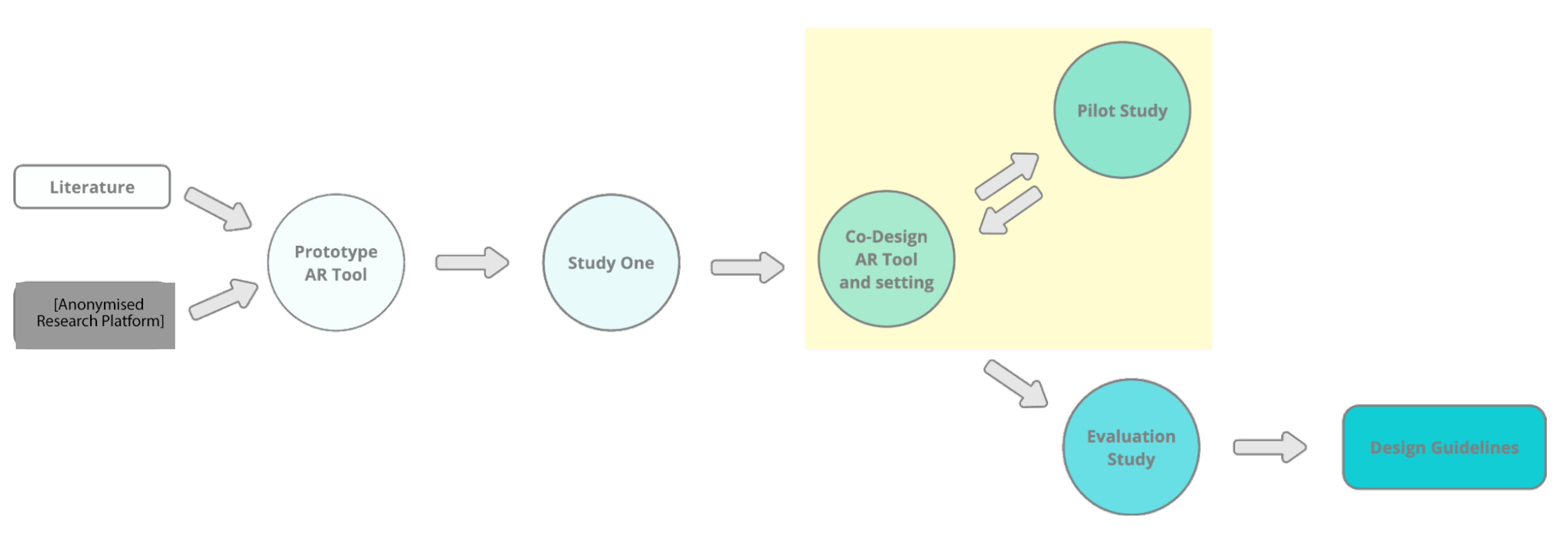

Figure 1.

Diagram illustrating the methods employed in this study.

Figure 1.

Diagram illustrating the methods employed in this study.

An initial study (Study One) evaluated the prototype, identifying key characteristics that guided the tool’s refinement. Following this, a co-design process was conducted with design researchers, materials scientists, a digital design studio, and a retail designer to ensure alignment with research goals, scientific rigour, production feasibility, and retail integration. Next, a pilot study was conducted to test the situational deployment of the AR tool within a simulation of a retail space. Insights from this stage informed adjustments to the setting of the experience, arriving at its final configuration. A final study (evaluation study) assessed the tool’s effectiveness. The data was analysed through the lens of existing literature and the [Anonymised Theoretical Framework]. The research concludes with the development of a set of design specifications intended to assist designers and researchers in exploring the integration of AR in the context of circular fashion and material storytelling.

4.1. Prototype AR

The [Centre Name Anonymised for review] is an interdisciplinary research initiative comprising three research strands: [Research Strand name Anonymised for review], each addressing different aspects of the CE in fashion and textiles. [Centre Name Anonymised for review] showcased their research in a public-facing event titled the [Anonymised research platform], held at [Place Name Anonymised for review].

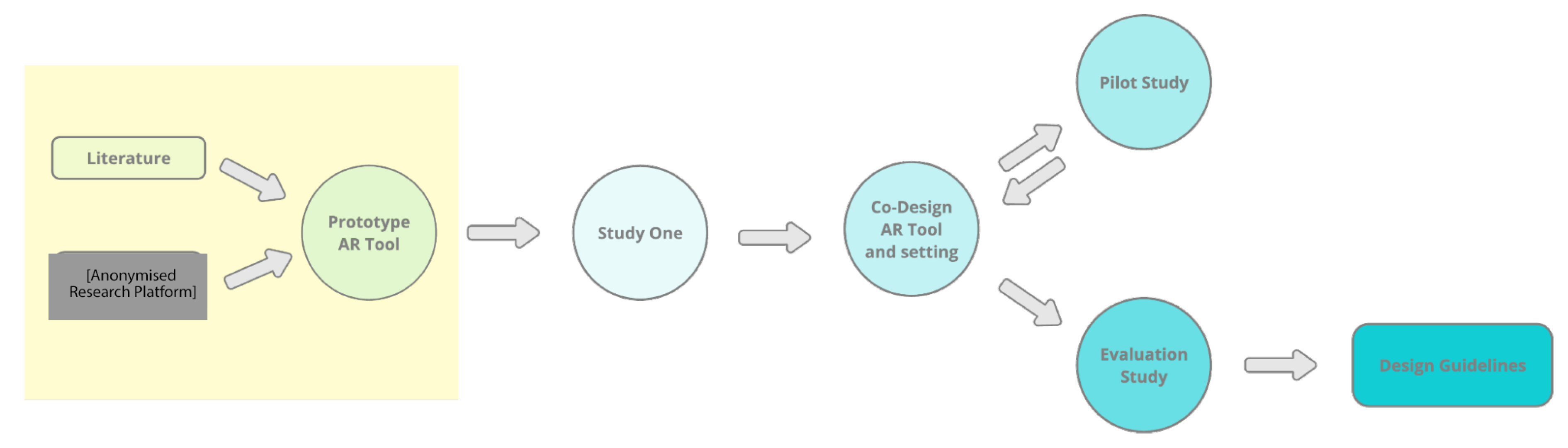

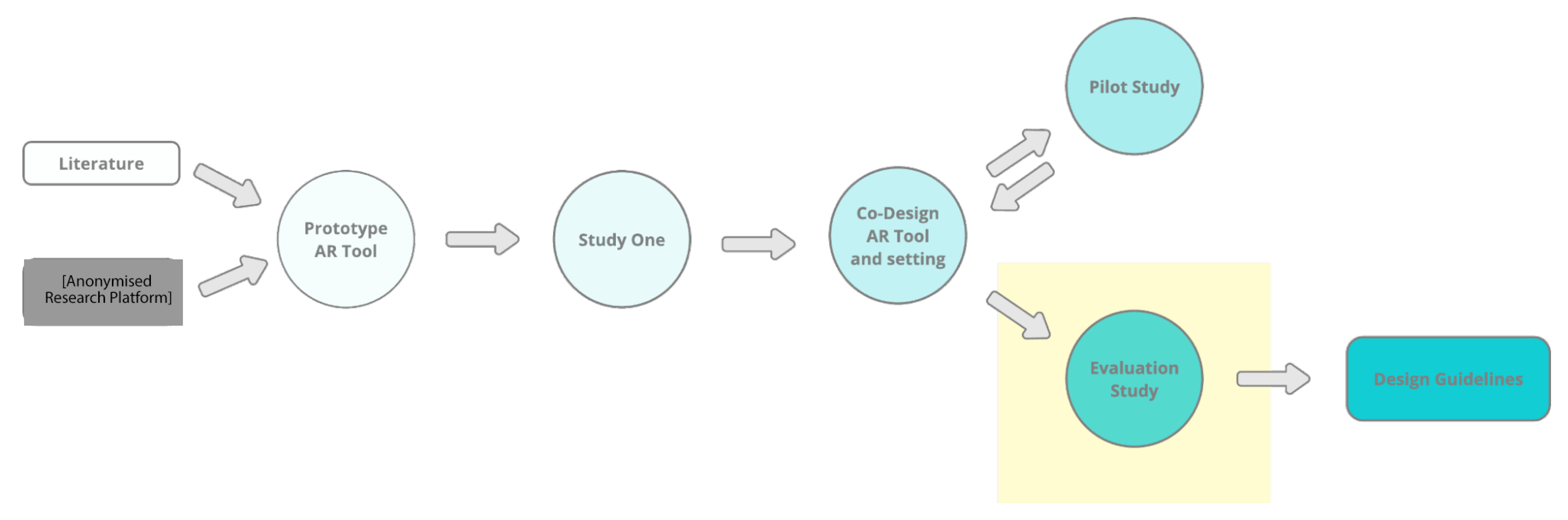

Figure 2.

Diagram illustrating the methods employed in this study, highlighting its initial phase.

Figure 2.

Diagram illustrating the methods employed in this study, highlighting its initial phase.

Within the

[Anonymised research platform], the

[strand name anonymised for review] strand presented their research on textiles made from bacterial cellulose through an installation titled the Material Showcase (

Figure 3). This installation displayed physical samples and prototypes produced via various advanced textile manufacturing processes. Although the Material Showcase effectively communicated the visual aspects of the bacterial cellulose textiles, its ability to convey the complexity and inherent qualities of the material was limited. To fill this gap, a card-based tool - the Materials Library - was available, and visitors could check technical information in the form of illustrations, images, and text about advanced circular bio-based materials, including the one exhibited in the Material Showcase. Although the Materials Library and the Material Showcase were technically integrated, our goal was to better integrate them through storytelling for future

[Anonymised research platform] iterations. It became clear that translating these resources into an accessible version for consumers was necessary to integrate materials circularity innovations with the design of consumer experiences.

This insight led to the hypothesis that integrating a digital layer—displaying information from the Materials Library directly onto the samples exhibited in the Material Showcase—would enhance consumer understanding by adding context, fostering participation, and introducing playfulness to the static display. Drawing on the storytelling concepts of material narratives and material framing, we proposed that AR could more effectively communicate materials’ origins, fabrication processes, and applications. We developed an initial AR application prototype and conducted a preliminary study using a survey to capture participants’ perceptions of the AR’s effectiveness in increasing their understanding of the bio-based textile and its circular production process. In this first iteration, we have chosen to display two types of information. In one sample, the digital layer will show the Materials Library card related to that sample (

Figure 4 left). In another sample, the digital layer will display a shirt made from that material (

Figure 4 right).

4.2. Study One: Generating Initial Design Specifications

The study adopted a comparative approach to evaluate participants’ experiences of the Materials Showcase in two conditions: without implementing the AR layer (

Figure 3) and with the AR layer integrated into the material samples’ visualisation (

Figure 4). The AR Layer consisted of a representation in 3D of a shirt made out of the material presented and another with information about the fabrication process similar to the one available in the Materials Library (

Figure 4). During the experimental procedure, participants could interact with the material samples in both conditions successively. Following these interactions, participants were requested to complete a survey to capture their qualitative feedback, enabling the systematic evaluation and comparison of their perceptions and understanding of the materials in the presence and absence of the AR intervention.

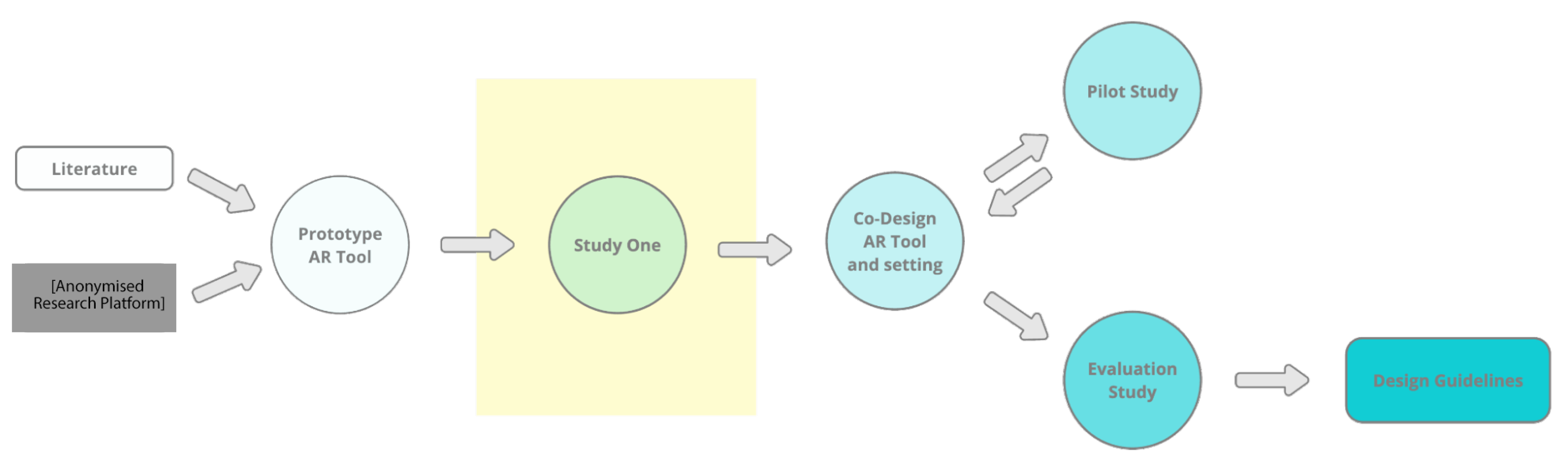

Figure 5.

Diagram illustrating the methods employed in this study, highlighting the first study.

Figure 5.

Diagram illustrating the methods employed in this study, highlighting the first study.

The study was conducted at the [Anonymised sustainable textiles fair], the largest dedicated showcase for sourcing certified, sustainable material solutions. It was approved by the local ethical committee, counted 15 participants who were visitors to the fair and recruited in situ.

Participants offered a range of evaluations on the AR experience, with ratings spanning from “poor”(3 participants) to “good” (7 participants) and “excellent” (3 participants). For nine participants, AR provided an engaging way to explore biomaterials, particularly enhancing their understanding of these materials’ appearance and potential texture when used in garments. Six respondents noted that AR reinforced their interest and curiosity in biomaterials, and for ten participants, it increased their confidence in the feasibility of biomaterials for real-world applications. However, five participants indicated that the AR layer did not significantly alter their initial perceptions, suggesting that the impact of AR on understanding bio-based materials may vary depending on prior interest and expectations.

Participants found AR helpful in visualising garment fit and drape, which led them to imagine potential applications they had not previously considered, as expressed by Participant Three: “The garment showed the fabric is strong enough to form a jacket, rather than fragile.” It was suggested that a more dynamic approach—such as animations of the garment being worn or a virtual hand manipulating the fabric—could enhance the user experience by showcasing the fabric’s physical properties in a lifelike manner, as expressed by Participant Five: “It would be better if each step could appear on the screen one after the other … I find 3D simulations of garments always a bit stiff, so maybe a video of the material being handled could be nice.”

Feedback included the need for more detailed information about the materials, with participants recommending additional zoom functionality, larger and more detailed images, and even videos to illustrate material properties better. For example, Participant Two stated that “A zoom for the samples or pop-up graphic – it’s too small”, and Participant Four expressed that “the quality needs to be greatly enhanced: image quality, try-on applications, easier to see/read/zoom in.” Also, the AR experience could further benefit from showing the step-by-step processes in biomaterial fabrication through sequential pop-up visuals and more contextual information about what is being displayed, allowing for a more intuitive understanding, as expressed by Participant Thirteen: “1. This example (cards) - pop-up interactivity to show steps in a more dynamic way - playfulness missing. 2. if you show the shirt vertically, you are engaged directly. Should be able to zoom + carry with you (should not disappear so easily).”

Based on the data collected, the following initial design specifications were established:

Present fabrication processes and complex information in a step-by-step, interactive format to support incremental learning and user engagement;

Integrate more interactive elements, such as animations, gamification, or a virtual manipulation feature, to enrich engagement and convey the materials’ qualities more realistically;

Ensure larger text, clearer graphics, and zoom functionality to enhance readability and enable close examination of material details;

Provide accessible explanations that contextualise the material properties within practical applications, using simple, user-friendly language to ensure inclusivity.

4.3. Collaborative Design Process: Consumer Experience + Materials Circularity + [Design Agency Name Anonymised for review]

The design specifications suggest demonstrating fabrication processes and complex information through a step-by-step, interactive format to support incremental learning and engagement. Enhanced interactivity, including animations, gamification, and virtual manipulation, will help convey material qualities more realistically. Improved readability will be ensured through larger text and clear graphics. Additionally, accessible explanations using simple, user-friendly language will contextualise material properties within practical applications, promoting inclusivity. Based on these design specifications from the initial study, we collaborated with a design agency and materials scientists from [Centre’s name anonymised for review] to develop the final AR application, which should integrate the material samples with AR simulations of their fabrication and potential uses.

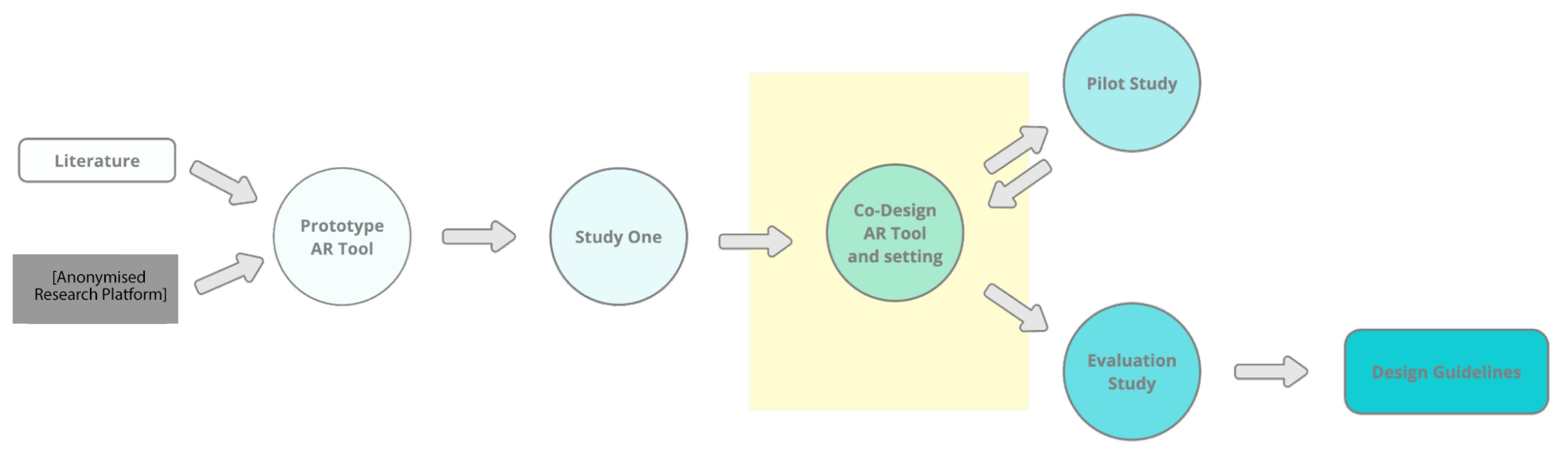

Figure 6.

Diagram illustrating the methods employed in this study, highlighting the co-design process.

Figure 6.

Diagram illustrating the methods employed in this study, highlighting the co-design process.

To better understand the steps involved in Wet spinning, one of the researchers visited the laboratory setting (

Figure 7), where the process took place to identify critical steps in the fibre production process. This stage provided foundational knowledge that informed the design of a virtual simulation for the wet spinning method. Wet spinning is a fibre manufacturing process in which a polymer solution is extruded through a syringe into a coagulation bath (which selectively removes the cellulose solvent), solidifying the fibre as it emerges [

22]. This laboratory observation and documentation phase grounded the AR simulation in scientifically accurate practices. Together with the researchers from the

[Anonymised for review], the key steps of fibre fabrication were identified.

4.3.1. Scene 1: Introduction

The design agency and the researchers decided to illustrate the wet spinning process by creating an AR laboratory experience. This virtual laboratory showcases the devices used in the process (see

Figure 8). The experience includes four AR markers, each serving as a trigger for a specific step in the process (see

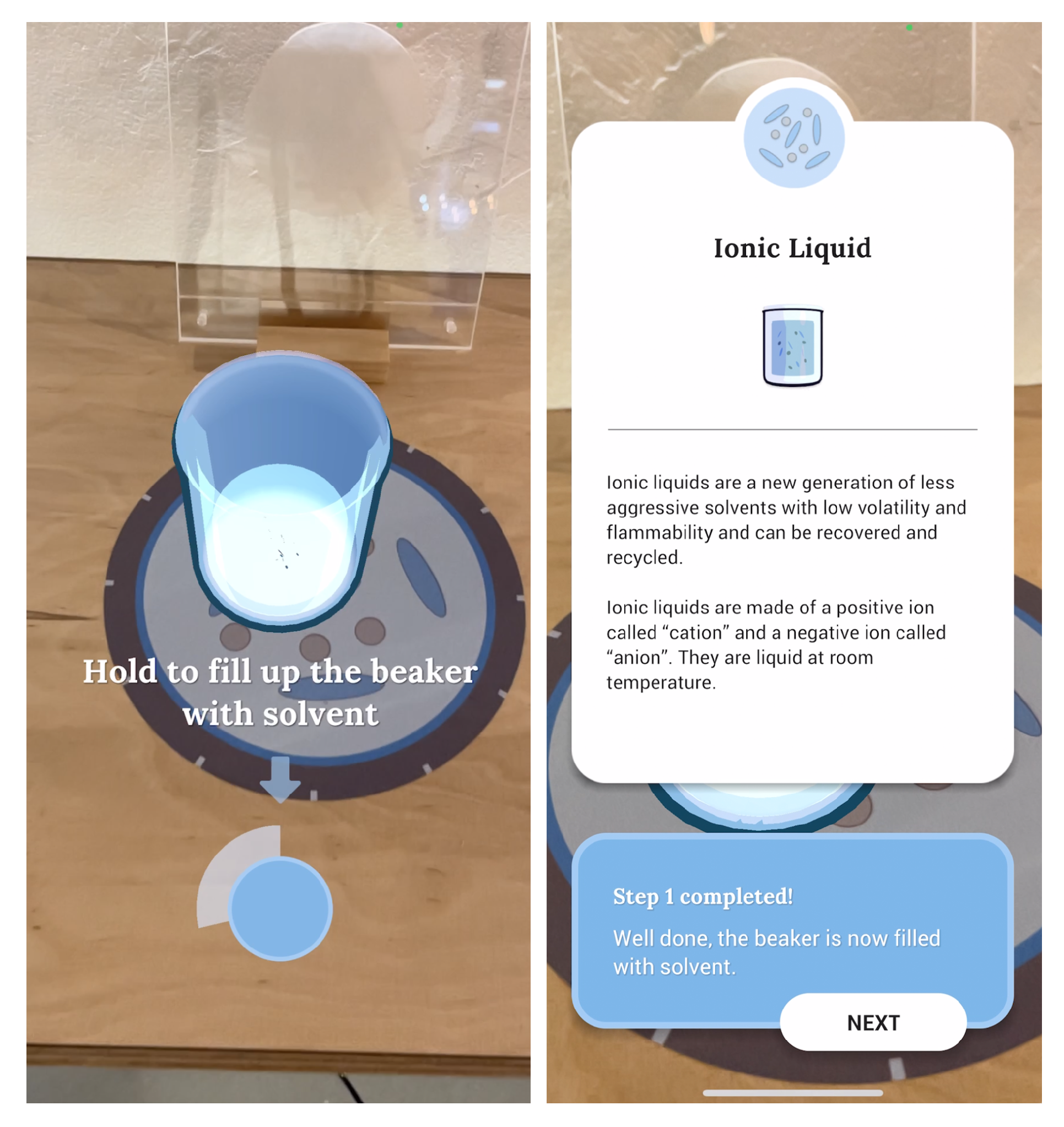

Figure 9). The first AR marker activates a virtual beaker; users must press and hold a button to fill it with solvent (see

Figure 10).

This interaction was designed to be playful and engaging, as the user controls the pace of the filling action, adding a dynamic element to the experience. A vibration accompanies this action to enhance sensory involvement, engaging the sense of touch and reinforcing interactivity beyond the visual aspect. This feature aligns with the initial design specifications aimed at using interactive elements to boost engagement. In discussions with the design agency, it was decided that due to the limitations of AR, the haptic feedback would be restricted to a uniform vibration.

4.3.2. Discovering Bacterial Cellulose

In this scene, the user interacts with a virtual representation of bacterial cellulose, the foundational material for the

[Centre’s name Anonymised for review] biobased textile [

22]. Through the AR interface, the user lifts the virtual cellulose sample and drops it into the beaker, which visually sinks into the liquid, simulating a chemical reaction. Once the beaker fills, an informational pop-up window offers further insights into bacterial cellulose (

Figure 11).

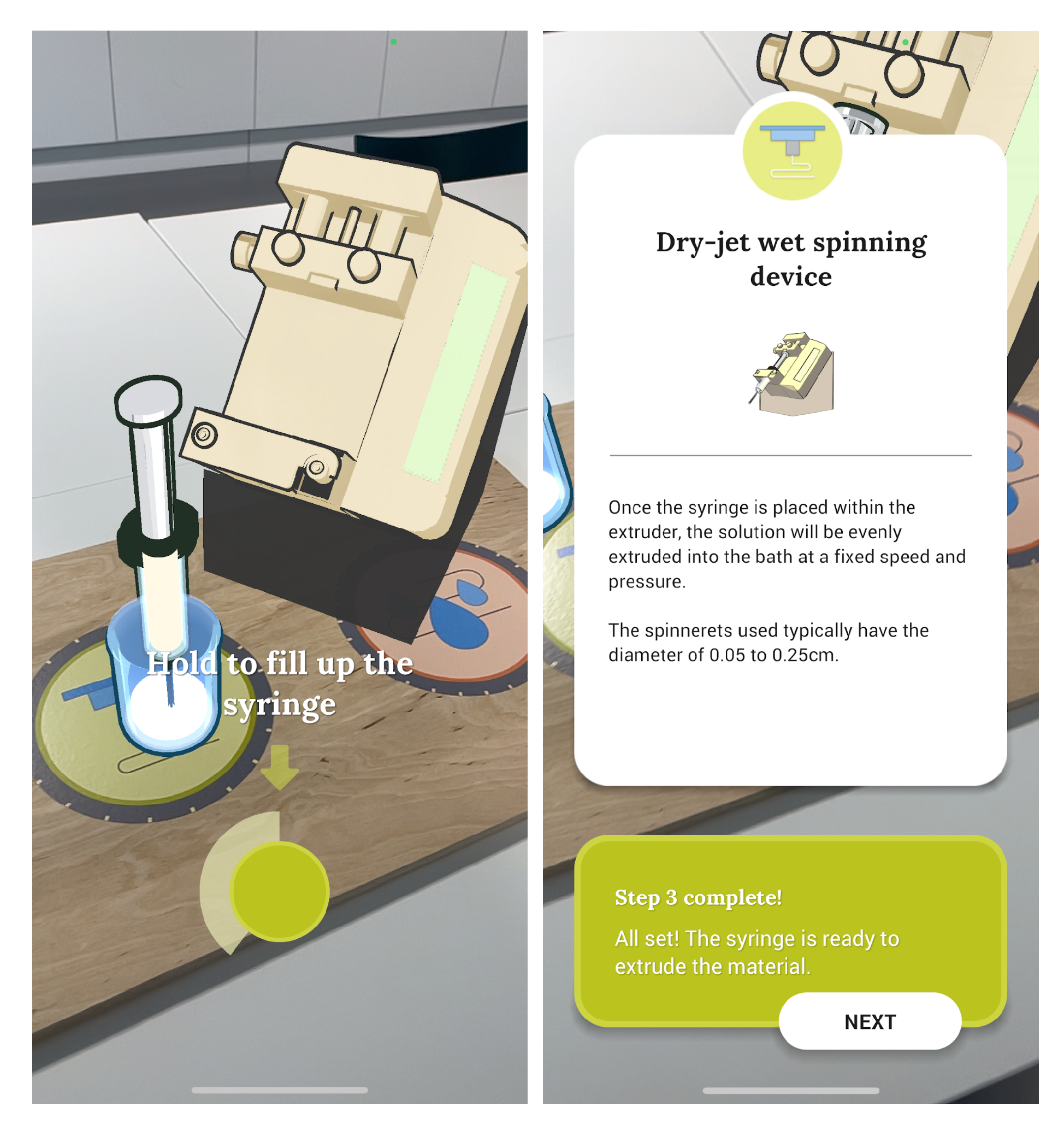

4.3.3. Scene 3: Preparation of the syringe

In this scene, a virtual syringe appears beside the beaker (

Figure 12). The user’s task is to draw the reacted liquid into the syringe. As the user presses and holds a button, the syringe gradually fills. This interactive step simulates the preparation of the material for the next phase in fibre production. Again, a textual explanation of the process. The text was initially written by the materials scientists and simplified through an iterative process to simplify it and remove jargon, as determined by the design specification.

4.3.4. Scene 4: Manual Task Simulation

This scene focuses on engaging users with simulated physical tasks. By pressing and holding a button, the user controls a pair of virtual tweezers that take the material from the syringe and navigate it through a series of virtual gears and other mechanical components, finally attaching it to the spinner within the simulated device. The user then presses and holds a button again to witness the filament passing through the virtual gears. Again, a pop-up with more information about that part of the process appears at the end of the task.

Figure 13.

Screenshot of the process of coagulation and spinning the material.

Figure 13.

Screenshot of the process of coagulation and spinning the material.

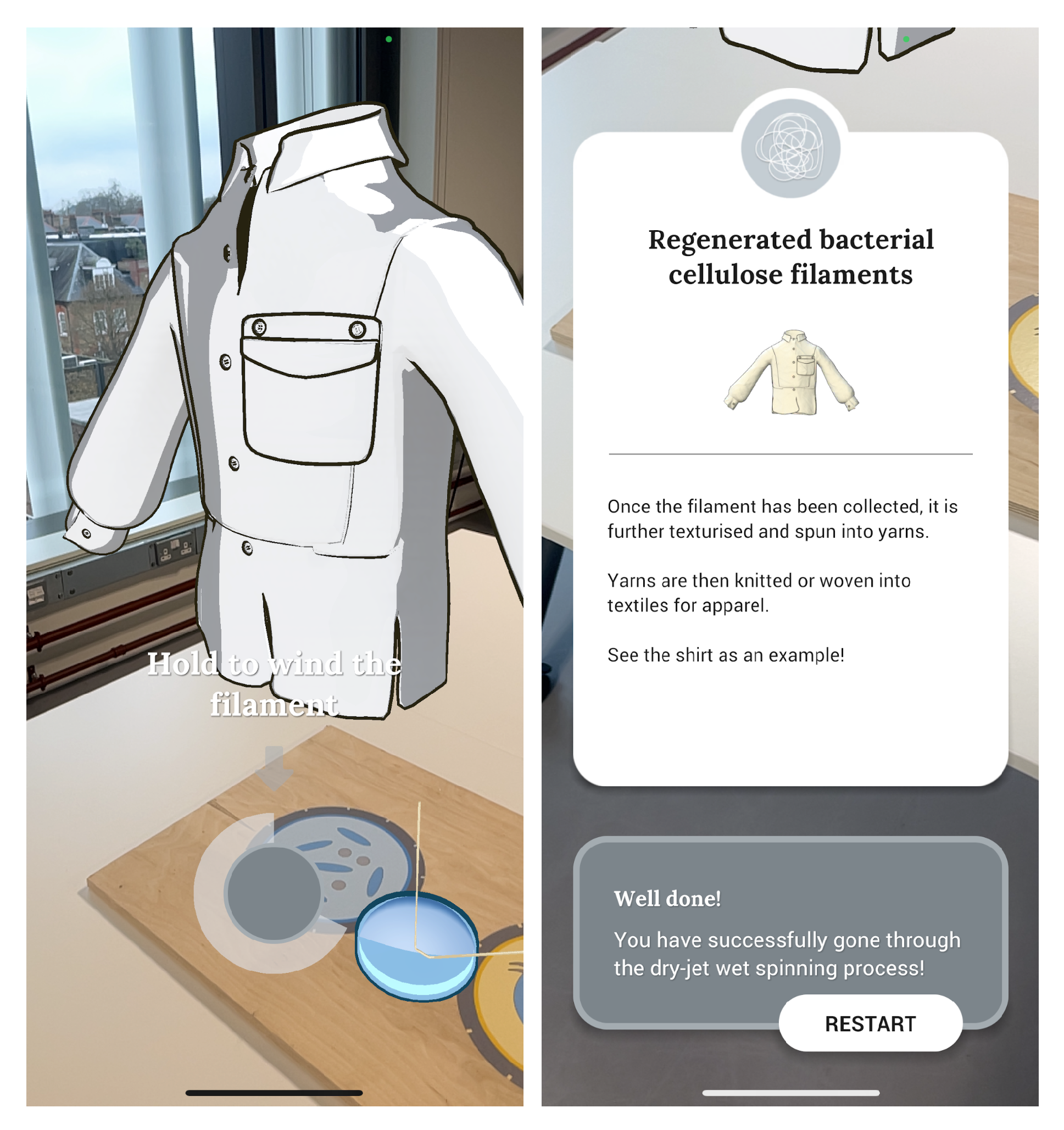

4.3.5. Scene 5: Witnessing the Creation

In the final scene, users are presented with a view of the wet spinning process. With the syringe securely positioned, the AR interface initiates the simulation of the wet spinning device. As the yarn is spun and winds onto a sample spool, the user sees the gradual formation of the material. As a concluding step, the yarn forms a virtual shirt to contextualise the material properties within practical applications according to the design specification.

4.4. Pilot Study

Once the AR tool was finalised, we held a pilot study at [Place’s name anonymised for review]. The aim was to evaluate the effectiveness of the application in enhancing consumer understanding of biobased textiles and its integration with specific wellbeing dimensions such as Enjoyment & Pleasure, Playfulness, Bodily & Sensory, Learning, and Future-self. The study counted twelve participants recruited through an online form. They received compensation for their time. The local ethics committee approved the study.

During the study, participants were invited to complete a questionnaire regarding their purchasing habits and relationship with fashion. Next, the participants were taken to another table where they could experience the bacterial cellulose material and the different stages of the material until it transformed into a textile. After they became familiar with the material and the different stages of fabrication, they were invited to use the AR application. Afterwards, they answered additional questions about their experience with the application.

4.4.1. Results and Discussion

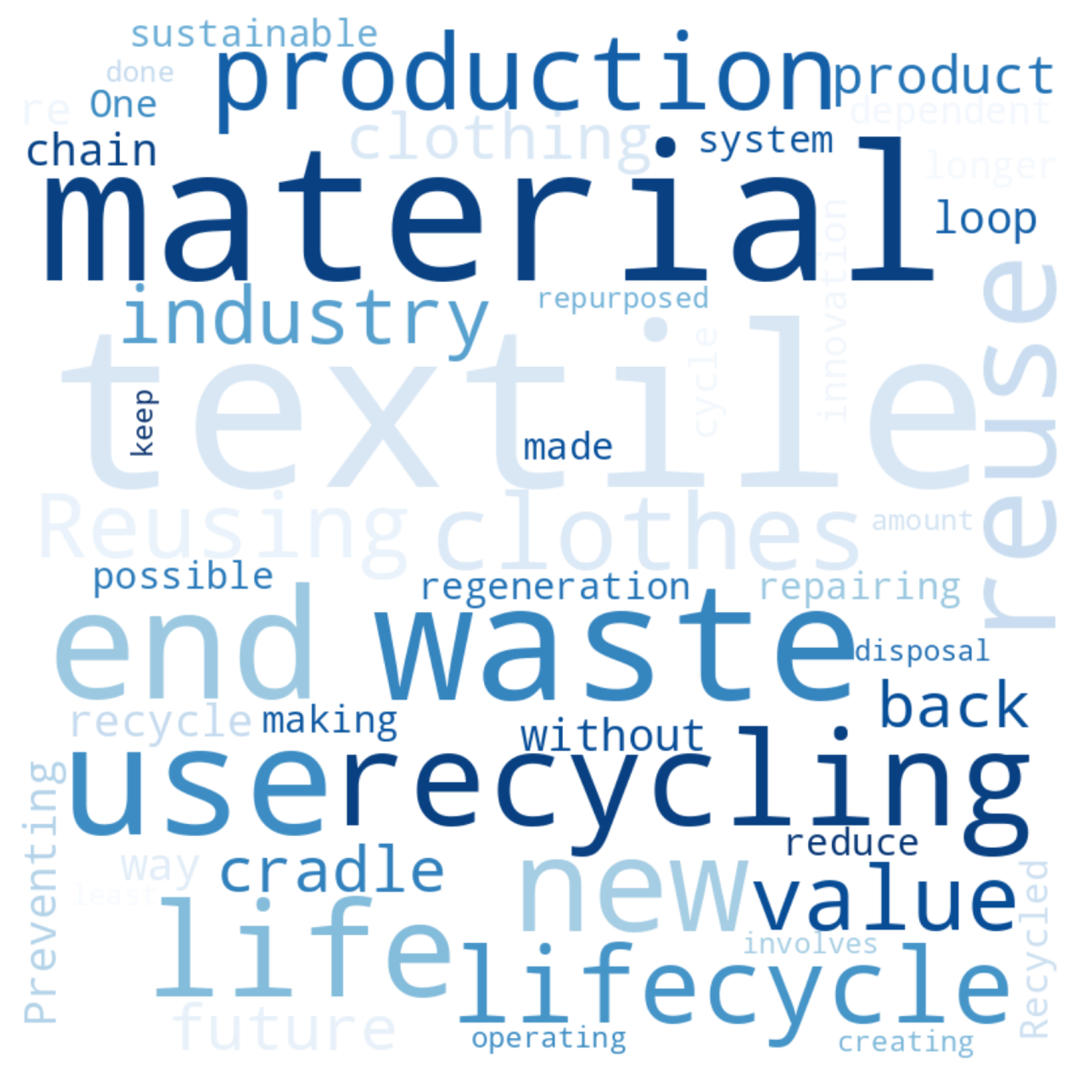

Among the participants, 62% (eight individuals) identified as female. The most represented age group was 25–34 years old. Participants reported limited prior knowledge of biobased textiles, with an average self-rated experience score of 34.45 on a scale from 0 to 100. When asked to define CE in the context of textiles, participants demonstrated a general awareness of principles such as zero-waste, supply chain transparency, and the concepts of reducing, reusing, and recycling. However, their responses revealed a lack of depth and clarity, often oversimplifying the broader systemic implications of CE practices.

When considering the factors influencing purchasing decisions, quality and durability were the most valued qualities, with the majority marking these as "Very important," shown by ratings peaking at 6. Similarly, comfort and fit received high importance, reflecting consumer emphasis on functionality and wearability. Price, while important to many, showed more variability, with significant ratings spread across "Fairly important" and "Important." In contrast, attributes like brand and fashion/trend were less critical. Overall, practical and functional aspects outweighed aesthetic and brand-related factors in consumer decision-making. However, responses to shopping as a leisure activity showed more variation. A broader spread of responses is evident for the statement, "Shopping is a way I like to spend my leisure time." While only a minority (1 participant) strongly agreed, a slightly higher proportion (5 participants) somewhat agreed.

Participants’ responses also revealed insights into their wellbeing. Most participants expressed a general sense of life satisfaction, with four somewhat agreeing and three strongly agreeing with the statement "I am satisfied with my life." Responses to the statement "I have been finding pleasure in my life" were even more positive, with seven somewhat agreeing and three strongly agreeing. However, feelings of happiness were mixed; only one strongly agreed they were mostly happy, while six somewhat agreed, and three were neutral. Regarding negative emotions, six participants were neutral, and three slightly agreed they felt overwhelmed.

After participants engaged with the AR experience, the findings revealed high levels of enjoyment and engagement. Most participants strongly agreed that the activity was fun, with positive responses to the statement, "I had fun doing this activity." Similarly, participants found the experience engaging, as reflected in their agreement with the statement, "I found this experience engaging." The multi-sensory nature of the activity, which combined visual and tactile stimulation, contributed significantly to participants’ immersion, with many agreeing that these features enhanced their understanding and interest. Participants found movement important to the experience, with half of the participants strongly agreeing that moving the body was important for the experience.

The AR experience also positively influenced participants’ knowledge and perceptions of biomaterials. Responses to the statement "I completely understood the wet spinning process" were mixed, suggesting that some participants struggled with comprehension. However, participants strongly agreed that the clarity of animations and texts effectively communicated the process. Participants found the information helpful, with many agreeing that it provided practical value applicable to their daily lives. Additionally, the statement "Knowing more about the manufacturing process might influence me to select better products" received the highest level of agreement, highlighting the potential of educational tools to shape consumer decision-making. Participants also noted that the experience improved their perception of biomaterials, particularly their feasibility for real-world applications, and positively changed their attitudes toward CE practices.

Several participants offered suggestions for improving future AR experiences. These included enhancing accessibility by providing clearer instructions on interacting with AR elements and incorporating sound effects to complement visuals. Participants also expressed interest in more detailed content, such as explaining scalability requirements and comparing bio-based materials and traditional textile manufacturing processes to provide reference points for considering the advantages and/or disadvantages of each. Additionally, they suggested incorporating gamified or motion-capture features to enhance interactivity and offer try-on capabilities to make the experience more immersive. Overall, most participants viewed the AR presentation as successful, striking an effective balance between text and visuals while engaging beginners and those with prior knowledge.

The main insight of this pilot study was that augmented reality (AR) is an effective tool for engaging individuals with bio-based materials by combining interactivity, multi-sensory experiences, and straightforward educational content to enhance understanding and positively influence perceptions of sustainability and CE practices. The findings demonstrate that the ‘Biofibre Explorer’ can bridge knowledge gaps, make abstract processes tangible, and encourage participants to consider biomaterials’ practical applications. However, to make the experience more coherent and time-efficient, it was decided that the material samples of each phase of the bacterial cellulose fabrication should be displayed in the same space as the AR elements (

Figure 14). This alteration was implemented in the second version of the study, which is explained next.

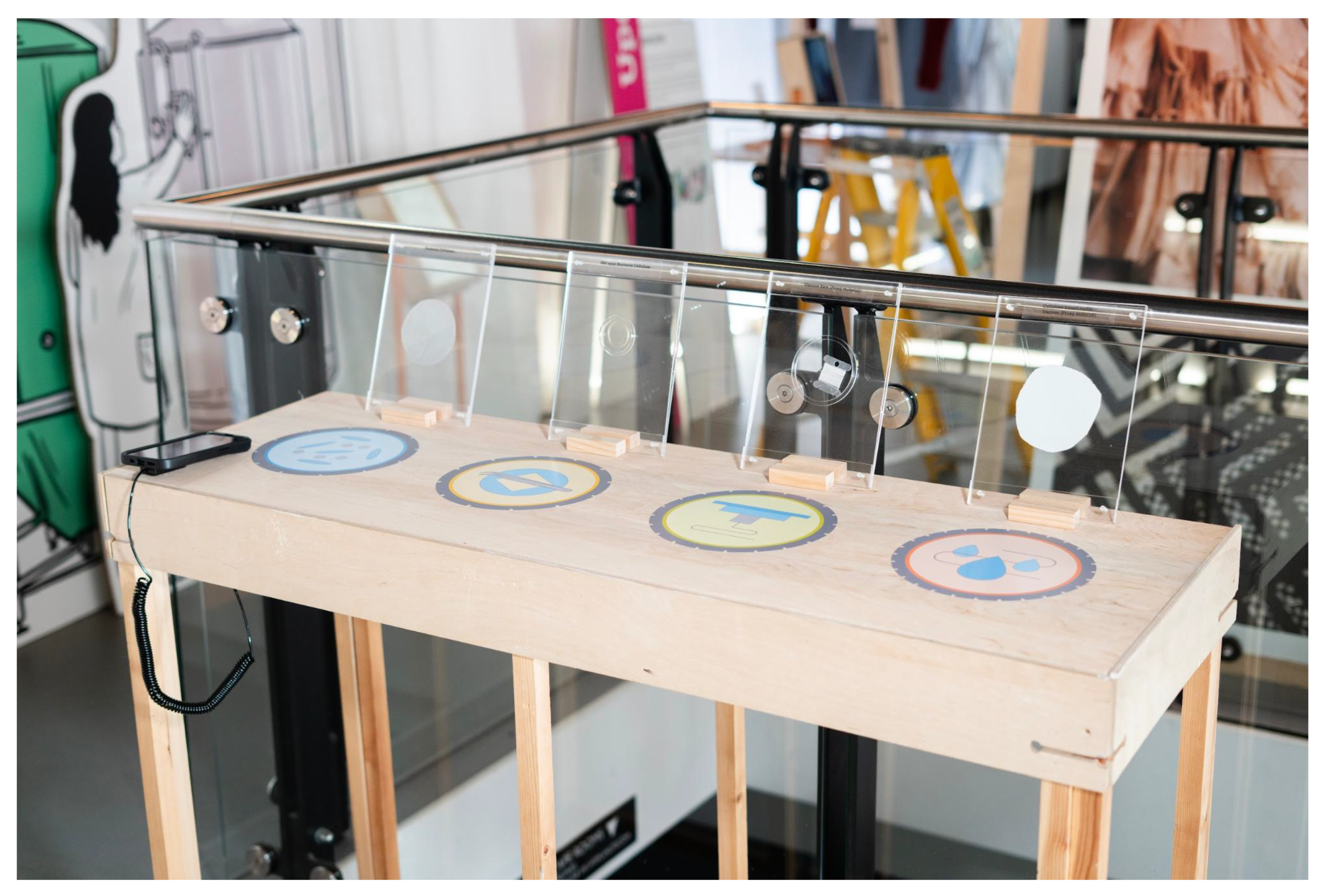

4.5. Evaluation Study

The evaluation study encompassed 39 participants, with the majority identified as female (62%) and aged between 25 and 34. The Local Ethics Committee approved the study. The objectives and methodology were consistent with those of the pilot study. The only difference from the pilot study was the placement of the material samples on the table next to the markers (see

Figure 16).

Before the study, participants reported limited familiarity with biobased textiles, reflected in an average self-rated knowledge score of 34.45 on a scale from 0 to 100. Despite this, initial responses to questions about the CE indicated a basic understanding of principles such as zero-waste and reuse-recycle strategies, albeit with limited depth regarding systemic implications, as represented in the word cloud in

Figure 18.

Sustainability is not yet top-of-mind The participants highlighted several priorities in their clothing purchase decisions. Quality, durability, comfort, and fit were consistently rated as highly important, while sustainability received moderate importance. Fashion trends and brands are less critical overall, receiving higher responses in the ‘slightly important’ and ‘Moderately important’ categories. Variability in responses related to price indicated diverse priorities among participants. 50% of participants reported shopping for clothing monthly, reflecting significant consumer engagement in the fashion sector.

For the data collected after the participants were exposed to the experience, Bayesian Wilcoxon Signed-Rank tests were used to compare participants’ ratings against the neutral value of 4 (“Neither agree nor disagree”). To quantify central tendency and dispersion for our ordinal Likert data, we employed the interpolated median and the median absolute deviation (MAD). On this scale, a score of 4 corresponds to “neither agree nor disagree”, 5 to “somewhat agree”, 6 to “agree”, and 7 to “strongly agree”. Bayesian methods were preferred to control for Type I errors and to differentiate between insufficient data and genuine null effects [

23]. Bayes Factors (BF

10)—which compare the evidence for the alternative relative to the null hypothesis—were interpreted as follows: values between 0.333 and 3 were considered insensitive, BF

10 >3 provided moderate evidence, BF

10 >10 strong evidence, BF

10>30 very strong evidence, and BF

10 >100 decisive evidence [

24].

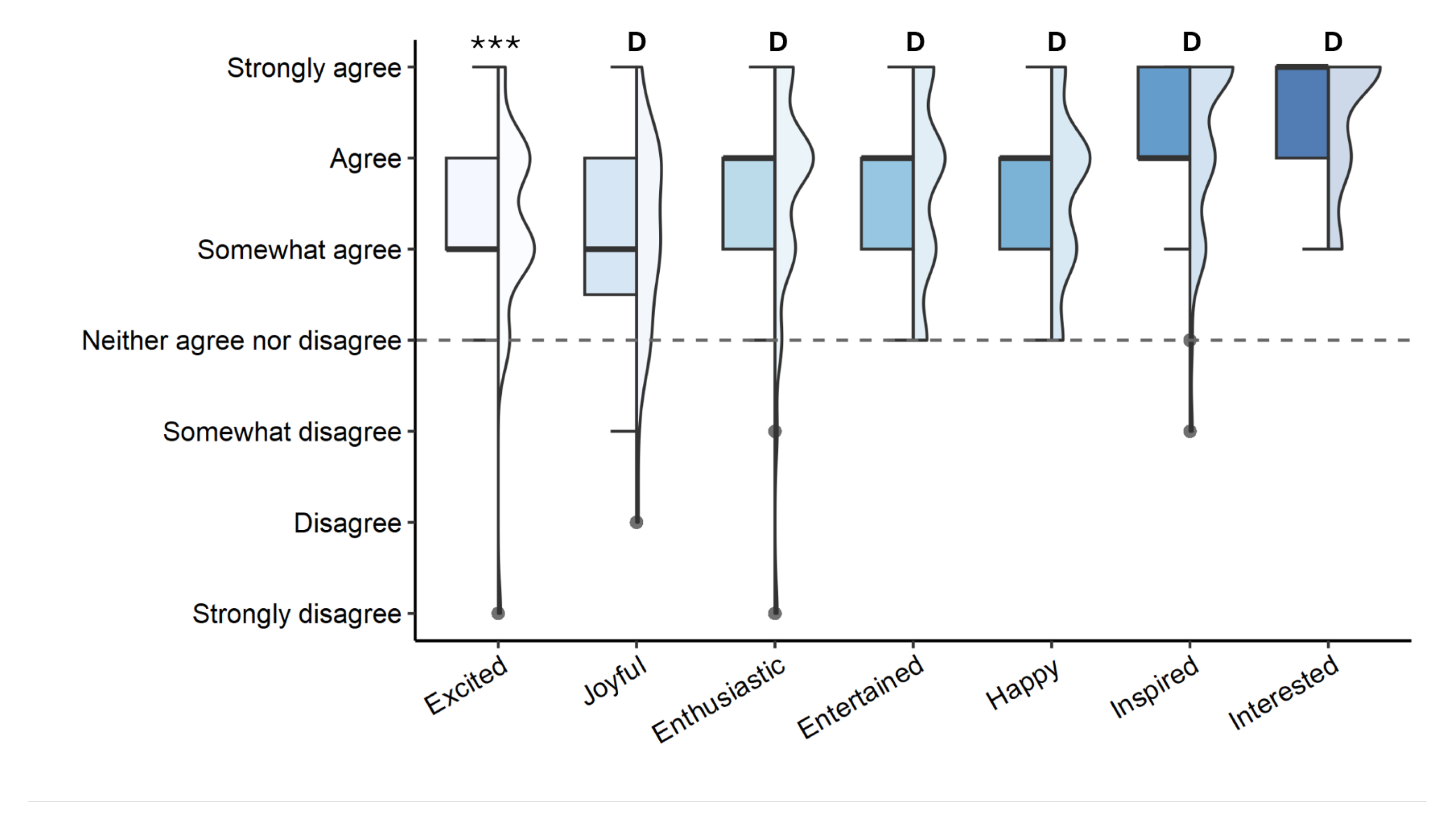

Emotional Responses to the Experience As shown in

Figure 19, participants “somewhat agreed” they felt excited (median = 5.34, MAD = 1.48, BF

10 = 981.47) and joyful (median = 5.23, MAD = 1.48, BF

10 >999), and “agreed” they felt enthusiastic (median = 5.82, MAD = 1.48, BF

10>999), entertained (median = 5.75, MAD = 1.48, BF

10 > 999) and happy (median = 5.71, MAD = 1.48, BF

10 >999). Consumers “strongly agreed” that the experience was interesting (median = 6.65, MAD = 0, BF

10 > 999) and that they felt inspired (median = 6.45, MAD = 1.48, BF

10 >999), with decisive evidence for a marked deviation from neutrality.

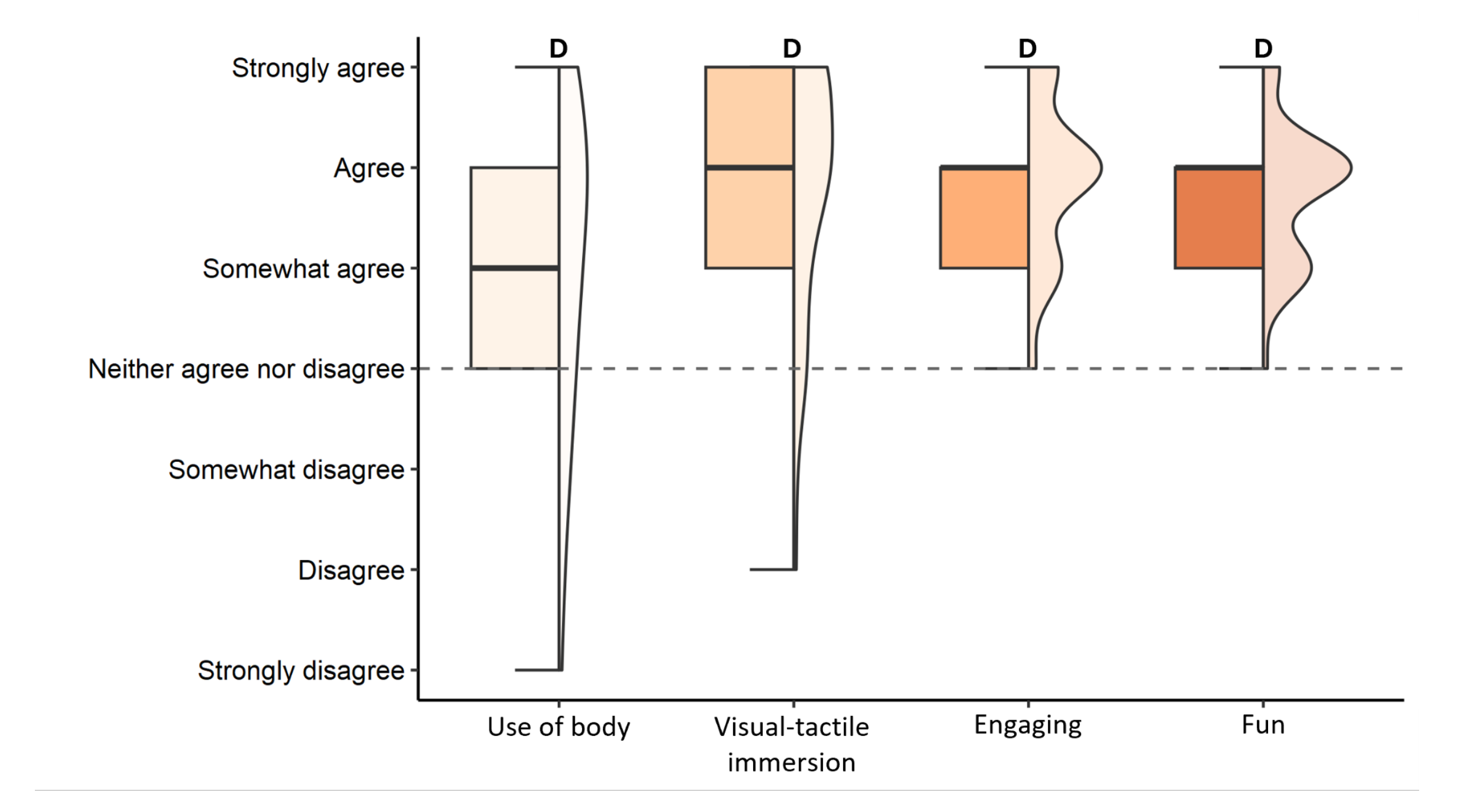

Bodily & sensory engagement benefits enjoyment and comprehension

Figure 20 displays the engagement ratings. Participants rated the experience as highly engaging, with fun (median = 5.80, MAD = 0, BF₁₀ >999), engagement (median = 5.92, MAD = 0, BF₁₀ >999) and visual-tactile immersion (median = 6.04, MAD = 1.48, BF₁₀ > 999) all supported by decisive evidence. Although bodily engagement was rated slightly lower (median = 5.31, MAD = 1.48, BF₁₀ = 85.40), it still significantly diverged from the neutral midpoint.

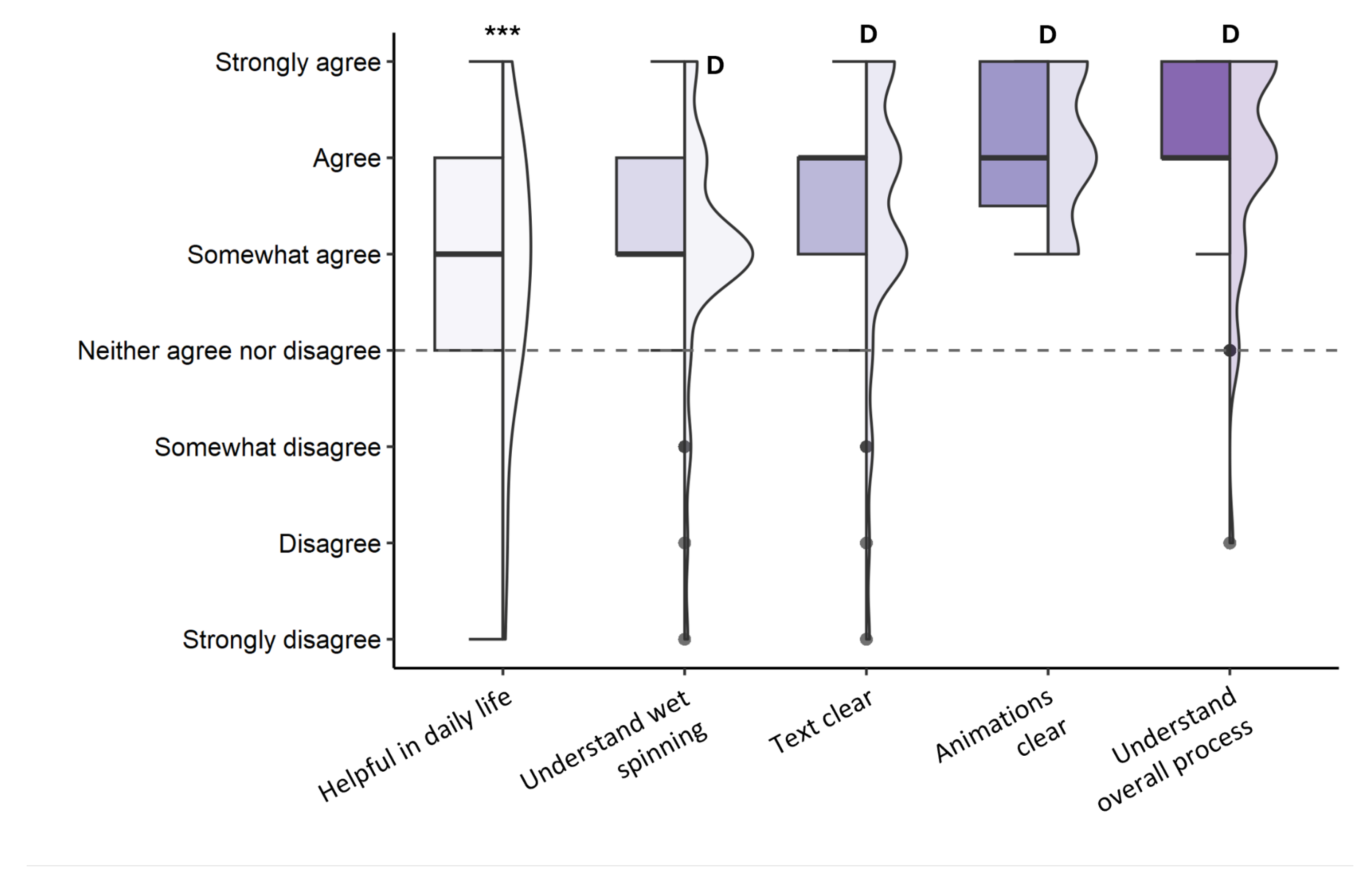

Supporting better product choices As illustrated in

Figure 21, all knowledge-related ratings were significantly above the midpoint. Understanding of the wet spinning process (median = 5.11, MAD = 0, BF₁₀ = 338.82) was significantly above the neutral value. Ratings for clarity of text (median = 5.55, MAD = 1.48, BF₁₀ >999), clarity of animations (median = 6.09, MAD = 1.48, BF₁₀ >999) and comprehension of the overall process (median = 6.20, MAD = 1.48, BF₁₀ >999) all provided decisive evidence. Although the rating for helpfulness (median = 4.96, MAD = 1.48, BF₁₀ = 37.43) was significant, the evidence was comparatively weaker. Overall, these findings suggest that the experience effectively conveyed key knowledge components, with some scope for improvement regarding the perceived helpfulness of the information.

5. Discussion

The Biofibre Explorer successfully addresses the identified gap by transforming complex, technical knowledge about bio-based materials into an engaging and accessible consumer experience. Unlike existing material storytelling methods, which predominantly focus on material characterisation and positioning, our approach emphasises the form of delivery as a critical element. By aligning the narrative with specific dimensions of human wellbeing ([Anonymised publication for review], forthcoming), we provide a novel method for communicating the fabrication processes and outcomes of materials.

Complementing and Expanding Storytelling Techniques Our findings confirm that our approach to using AR guided by the [Theoretical Framework Anonymised for review]([Anonymised Publication for review], forthcoming) complements and extends existing material storytelling techniques discussed in the literature. It highlights that the form of delivery has a direct impact on engagement and immersion, which is key for effectively communicating complex information. By intentionally incorporating the wellbeing dimensions of Enjoyment & Pleasure, Learning, Playfulness, Bodily & Sensory and Future self, the Biofibre Explorer enhances the storytelling framework to create a more holistic and impactful experience. This alignment with wellbeing dimensions extends the potential of AR—and other creative technologies—to inform and emotionally and physically engage consumers, fostering deeper understanding and connection with bio-based materials.

The importance of form beyond content While the content elements—origin, processes and outcomes—remain consistent with established practices [

18,

19,

21], our study highlights that the form in which these elements are presented significantly affects their assimilation. The AR Biofibre Explorer prioritises the emotional and embodied aspects of material knowledge through immersive and multi-sensory design. By crafting a narrative that integrates visual and tactile elements, our approach bridges the cognitive and sensory domains, enabling users to connect with the material on both intellectual and emotional levels. A prior study indicated that consumers value engaging with new bio-based materials through a multisensory experience

(Anonymized publication, under review). However, such engagement is frequently constrained by the limited availability of materials and the high costs associated with their production until these innovations are sufficiently scaled. Therefore, creating a more immersive and multi-sensory narrative around these materials emphasises the significant role of form in translating technical information into experiences that are meaningful, relatable, and memorable for consumers.

Promoting Wellbeing and Multimodal Engagement The application effectively promotes dimensions of wellbeing such as learning, competence, engagement, enjoyment, playfulness, and future selves. Results from our study demonstrated high levels of engagement and enjoyment among participants, particularly due to the immersive and interactive features of the AR tool. Notably, 69.2% of respondents agreed on the importance of combining visual and tactile stimulation, emphasising the value of multimodal engagement in creating meaningful experiences. These findings suggest that expanding AR beyond its traditional visual focus to incorporate sound, touch, and even smell could further enhance its potential to engage users and foster multi-sensory understanding.

Alignment between physical space and the digital experience The comparison between the fragmented experience in Pilot Study 1 and the integrated experience in the Evaluation Study reveals critical insights into the importance of unified narratives and physical contexts. In the Pilot Study, participants learned about material samples separately from the AR experience, which fragmented their understanding. Conversely, integrating physical samples with the AR tool created a cohesive experience that facilitated cognitive connections between the process and its outcomes. Despite this improvement, participants frequently requested direct tactile interaction with the samples, indicating that while the smartphone application’s vibrations were perceived as engaging and playful, they could not substitute for the richness of actual touch.

Redefining AR for Multisensory Perception This research calls for a redefinition of AR to incorporate the full spectrum of human perception. AR remains largely vision-centric, often overlooking the contributions of other senses. Our study demonstrates that incorporating tactile and visual stimuli can significantly enhance immersion, suggesting that future AR applications should prioritise a multimodal design approach. This redefinition of AR has profound implications for its role in promoting sustainability and circularity, as it can enable consumers to connect more deeply with new bio-based materials.

Engaging Diverse Stakeholders The Biofibre Explorer demonstrates significant potential as a tool for engaging diverse stakeholders, including consumers, manufacturers, materials scientists, and brands. Its ability to convey technical materials knowledge in an accessible and enjoyable way positions it as a valuable resource for fostering dialogue and collaboration across the textile and fashion industries.

6. Limitations and Future Research

Despite the success of the Biofibre Explorer in enhancing material communication, several areas require further refinement. One key challenge identified was the complexity of the textual content. While the descriptions were scientifically accurate, some participants found them overly technical, which hindered engagement. Our collaboration with materials scientists revealed that while precise terminology is essential, adjusting language to suit different audiences could improve accessibility and user experience. Future iterations should explore adaptive content delivery, tailoring complexity based on user expertise or offering multiple levels of explanation.

Another limitation concerns the long-term impact of the experience. While the benefits of immediate engagement and comprehension were evident, future longitudinal studies should assess how well participants retain knowledge over time. Understanding the persistence of learning and behavioural change will provide insights into the effectiveness of immersive material education and inform improvements in content structuring.

Additionally, further development should explore advancements in haptic feedback. Current touch interactions in the AR experience remain limited by smartphone-based mediation. While the device’s vibrations provided an engaging and playful element, they were insufficient in replicating the tactile qualities of bio-based textiles. Emerging haptic technologies, such as high-fidelity actuators or smart materials capable of simulating different textures, could enhance user immersion. The use of smart glasses presents another promising direction for future work. Transitioning from handheld devices to wearable AR could eliminate manual mediation, allowing for more natural, embodied interactions with materials. This shift could enable users to engage with bio-based materials hands-free, fostering deeper cognitive and sensory connections.

Finally, expanding the scope of the Biofibre Explorer to incorporate other creative technologies, such as Virtual Reality, and materials could enhance its versatility and impact. Exploring alternative digital technologies, interactive storytelling strategies, or multisensory integration—including sound and even scent—could further enrich the user experience and contribute to broader consumer engagement with bio-based materials.

7. Conclusions

This study demonstrates how AR can be extended beyond its conventional retail applications to support circularity in the fashion and textile industries. The Biofibre Explorer was designed to bridge the material knowledge gap by engaging consumers in the wet spinning process of bio-based textiles, fostering informed decision-making and sustainable consumption behaviours. By aligning the tool with the [Theoretical Framework Anonymised for review], we illustrate how AR can enhance understanding while also promoting dimensions such as Enjoyment & Pleasure, Playfulness, Bodily & Sensory, Learning, and Future-self. Through mixed-methods evaluation, our findings demonstrate the effectiveness of multisensory and interactive approaches in fostering material engagement and cognitive retention. This research contributes to the growing discourse on AR’s potential in sustainability communication, emphasising the importance of multimodal interaction in material storytelling. Future work should explore advanced haptic feedback, wearable AR solutions, and expanded creative technology applications to further enhance material education and deepen consumer connection with bio-based materials. By redefining AR as a tool for knowledge-building rather than just product visualisation, this study advances the role of digital tools in fostering more circular and sustainable consumer behaviour.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ricardo O’Nascimento and Bruna Petreca; methodology, Ricardo O’Nascimento; formal analysis, Christopher Dawes; investigation, Ricardo O’Nascimento and Bruna Petreca; writing—original draft preparation, Ricardo O’Nascimento; writing—review and editing, X.X.; supervision, Sharon Baurley and Bruna Petreca; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was Funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EP/V011766/1), for the National Interdisciplinary Circular Economy Research (NICER) programme for the UK Research & Innovation (UKRI) Interdisciplinary Circular Economy Centre for Textiles: Circular Bioeconomy for Textile Materials.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Boletsis, C.; Karahasanovic, A. Immersive Technologies in Retail: Practices of Augmented and Virtual Reality:. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications, Budapest, Hungary, 2020; pp. 281–290. [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Perry, P.; Boardman, R.; McCormick, H. Augmented reality in retail: a systematic review of research foci and future research agenda. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 2022, 50, 498–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmigniani, J.; Furht, B. Augmented Reality: An Overview. In Handbook of Augmented Reality; Furht, B., Ed.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2011; pp. 3–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturkcan, S. Service innovation: Using augmented reality in the IKEA Place app. Journal of Information Technology Teaching Cases 2021, 11, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riar, M.; Korbel, J.J.; Xi, N.; Zarnekow, R.; Hamari, J. The Use of Augmented Reality in Retail: A Review of Literature. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Lavoye, V.; Mero, J.; Tarkiainen, A. Consumer behavior with augmented reality in retail: a review and research agenda. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 2021, 31, 299–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; Susmit, S.; Lin, C.Y.; Masukujjaman, M.; Ho, Y.H. Factors Affecting Augmented Reality Adoption in the Retail Industry. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 2021, 7, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L. Designing effective augmented reality platforms to enhance the consumer shopping experiences. PhD thesis, Loughborough University, 2022. Artwork Size: 26396861 Bytes.

- Durugbo, C.M. After-sales services and aftermarket support: a systematic review, theory and future research directions. International Journal of Production Research 2020, 58, 1857–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagoropoulos, A.; Pigosso, D.C.; McAloone, T.C. The Emergent Role of Digital Technologies in the Circular Economy: A Review. Procedia CIRP 2017, 64, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.C.; Chandukala, S.R.; Reddy, S.K. Augmented Reality in Retail and Its Impact on Sales. Journal of Marketing 2022, 86, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Yin, S.; Chen, L.; Chen, X. The circular economy in the textile and apparel industry: A systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 259, 120728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Fernandez, A.; Aramendia-Muneta, M.E.; Alzate, M. Consumers’ awareness and attitudes in circular fashion. Cleaner and Responsible Consumption 2023, 11, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzanne Lee.; Dr Amy Congdon.; Georgia Parker.; Charlotte Borst. Understanding "Bio" Material Innovations: a primer for the fashion industry. Technical report, Biofabricate & Fashion for Good, 2020.

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R.; Gonzalez, E.S. Understanding the adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies in improving environmental sustainability. Sustainable Operations and Computers 2022, 3, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenton, T.M.; Benson, S.; Smith, T.; Ewer, T.; Lanel, V.; Petykowski, E.; Powell, T.W.R.; Abrams, J.F.; Blomsma, F.; Sharpe, S. Operationalising positive tipping points towards global sustainability. Global Sustainability 2022, 5, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Merino, J.A.; Rios-Lama, C.A.; Panez-Bendezú, M.H. Sustainable Consumption: Conceptualization and Characterization of the Complexity of “Being” a Sustainable Consumer—A Systematic Review of the Scientific Literature. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, I.; Speed, C. Making as Growth: Narratives in Materials and Process. Design Issues 2017, 33, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. M. C. Machgeels. Convivial Construct: A method to create material narratives to positively influence the materials experience. Master’s thesis, Tu Delft,Industrial Design Engineering, Delft, 2018.

- Rognoli, V.; Petreca, B.; Pollini, B.; Saito, C. Materials biography as a tool for designers’ exploration of bio-based and bio-fabricated materials for the sustainable fashion industry. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 2022, 18, 749–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Olivo, P.; Karana, E. Materials Framing: A Case Study of Biodesign Companies’ Web Communications. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 2021, 7, 403–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanot, A.; Tiwari, S.; Purnell, P.; Omar, A.M.; Ribul, M.; Upton, D.J.; Eastmond, H.; Badruddin, I.J.; Walker, H.F.; Gatenby, A.; et al. Demonstrating a biobased concept for the production of sustainable bacterial cellulose from mixed textile, agricultural and municipal wastes. Journal of Cleaner Production 2025, 486, 144418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienes, Z. Bayesian Versus Orthodox Statistics: Which Side Are You On? Perspectives on Psychological Science 2011, 6, 274–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffreys, H. Theory of probability, 3. ed., repr ed.; Oxford classic texts in the physical sciences, Clarendon Pr: Oxford. 2003. [Google Scholar]

Figure 3.

Material Showcase of the new biobased textile developed at [Centre Name Anonymised for review].

Figure 3.

Material Showcase of the new biobased textile developed at [Centre Name Anonymised for review].

Figure 4.

Materials Sample being assessed through the AR application.

Figure 4.

Materials Sample being assessed through the AR application.

Figure 7.

Wet spinning device developed in the [Anonymised University Name for review].

Figure 7.

Wet spinning device developed in the [Anonymised University Name for review].

Figure 8.

The digital elements representing the devices responsible for the wet spinning process. A specific AR marker triggers each step of the process.

Figure 8.

The digital elements representing the devices responsible for the wet spinning process. A specific AR marker triggers each step of the process.

Figure 10.

Screenshot of the first step and its textual explanation.

Figure 10.

Screenshot of the first step and its textual explanation.

Figure 11.

Screenshot of the step where the bacterial cellulose dissolves in the ionic liquid, creating the material for the next fabrication step and Pop-up explaining the process in more detail.

Figure 11.

Screenshot of the step where the bacterial cellulose dissolves in the ionic liquid, creating the material for the next fabrication step and Pop-up explaining the process in more detail.

Figure 12.

Screenshot of the stage where the solution is placed inside the syringe and Pop-up explaining the process in more detail.

Figure 12.

Screenshot of the stage where the solution is placed inside the syringe and Pop-up explaining the process in more detail.

Figure 14.

Screenshot of the final step of the experience, displaying a virtual shirt and Pop-ups explaining the process in more detail.

Figure 14.

Screenshot of the final step of the experience, displaying a virtual shirt and Pop-ups explaining the process in more detail.

Figure 15.

Diagram illustrating the methods employed in this study, highlighting the pilot study.

Figure 15.

Diagram illustrating the methods employed in this study, highlighting the pilot study.

Figure 16.

Final set up of the experience.

Figure 16.

Final set up of the experience.

Figure 17.

Diagram illustrating the methods employed in this study, highlighting the evaluation study.

Figure 17.

Diagram illustrating the methods employed in this study, highlighting the evaluation study.

Figure 18.

Word Cloud composed of the most used words to describe what a CE of textiles is.

Figure 18.

Word Cloud composed of the most used words to describe what a CE of textiles is.

Figure 19.

Participants’ emotional responses on a 7-point Likert. Bayesian Wilcoxon Signed-Rank tests revealed decisive evidence that ratings deviated from “Neither agree nor disagree”, suggesting, for instance, that participants Strongly Agreed that the experience was inspiring. Note: *** = BF10 >100, D = BF10 >999

Figure 19.

Participants’ emotional responses on a 7-point Likert. Bayesian Wilcoxon Signed-Rank tests revealed decisive evidence that ratings deviated from “Neither agree nor disagree”, suggesting, for instance, that participants Strongly Agreed that the experience was inspiring. Note: *** = BF10 >100, D = BF10 >999

Figure 20.

Participants’ engagement responses on a 7-point Likert. Responses suggested that participants agreed that the experience was fun and engaging and that the visual and tactile aspects added to the immersion. However, they only somewhat agreed they needed to use their body for the experience. Note: *** = BF10>100, D = BF10>999.

Figure 20.

Participants’ engagement responses on a 7-point Likert. Responses suggested that participants agreed that the experience was fun and engaging and that the visual and tactile aspects added to the immersion. However, they only somewhat agreed they needed to use their body for the experience. Note: *** = BF10>100, D = BF10>999.

Figure 21.

Participants’ engagement responses on a 7-point Likert. Responses suggested that participants agreed the experience was fun and engaging and that the visual and tactile aspects added to the immersion. However, they only somewhat agreed they needed to use their body for the experience. Note: *** = BF10>100, D = BF10>999.

Figure 21.

Participants’ engagement responses on a 7-point Likert. Responses suggested that participants agreed the experience was fun and engaging and that the visual and tactile aspects added to the immersion. However, they only somewhat agreed they needed to use their body for the experience. Note: *** = BF10>100, D = BF10>999.

Table 1.

Selected wellbeing concepts are to be articulated through the AR Biofibre Explorer, adapted from [Anonymised publication for review].

Table 1.

Selected wellbeing concepts are to be articulated through the AR Biofibre Explorer, adapted from [Anonymised publication for review].

| Concept |

Description |

| ]1*Learning |

Active engagement in acquiring skills and knowledge. |

| ]1*Attachment |

Emotional bonds formed through connection and affection influenced by meeting expectations, utility, aesthetic appeal, effort, and positive experiences. |

| ]1*Competence |

Skill and confidence in making informed choices about product use and acquisition, as well as their ability to engage in specific circular practices like renewal and repair. |

| ]1*Playfulness |

The inclination toward fun, spontaneous, and creative activities, especially in social interactions with familiar individuals. |

| ]1*Future-self |

Ability to envision future outcomes and take proactive steps to create desired changes. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).