Submitted:

21 August 2025

Posted:

22 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Design innovations (zero-/low-waste techniques, modularity, upcycling),

- Production sustainability (energy and water efficiency, local/regional sourcing),

- Dematerialization approaches (leasing, repair, co-creation models),

- Digital engagement (transparency, traceability, advocacy),

- Cultural engagement (revival of traditional craftsmanship, DIY culture).

2. Research Design

- Explicitly reference or demonstrate sustainability in design, production, communication, or community engagement; and

- Present collections at fashion events consistently over a number of years to ensure sustained activity rather than short-term initiatives.

- Participant observation at 15 industry events (fashion shows, exhibitions, and stakeholder meetings and talks, and sustainability workshops), which allowed for first-hand documentation of sustainability practices and discourses.

- Semi-structured interviews with 24 participants (18 designers and brand representatives, 1 producer, and 5 media actors). Interviews were recorded where permitted (n=20), and otherwise documented through detailed notes and immediate post-conversation write ups (n=24).

-

Qualitative thematic analysis:

- Interview transcripts, observation notes, and archival materials were coded following Braun & Clarke’s [7] reflexive thematic analysis approach.

- Codes were inductively developed, and then refined into categories such as waste reduction, localization of supply chain, design innovation, cultural engagement, and digital transparency.

- The intersection of three approaches – interviews, observation, and media sources – ensures validity and reduces reliance on self-reporting.

-

Quantitative description mapping:

- Practices were recorded for each of the 52 brands.

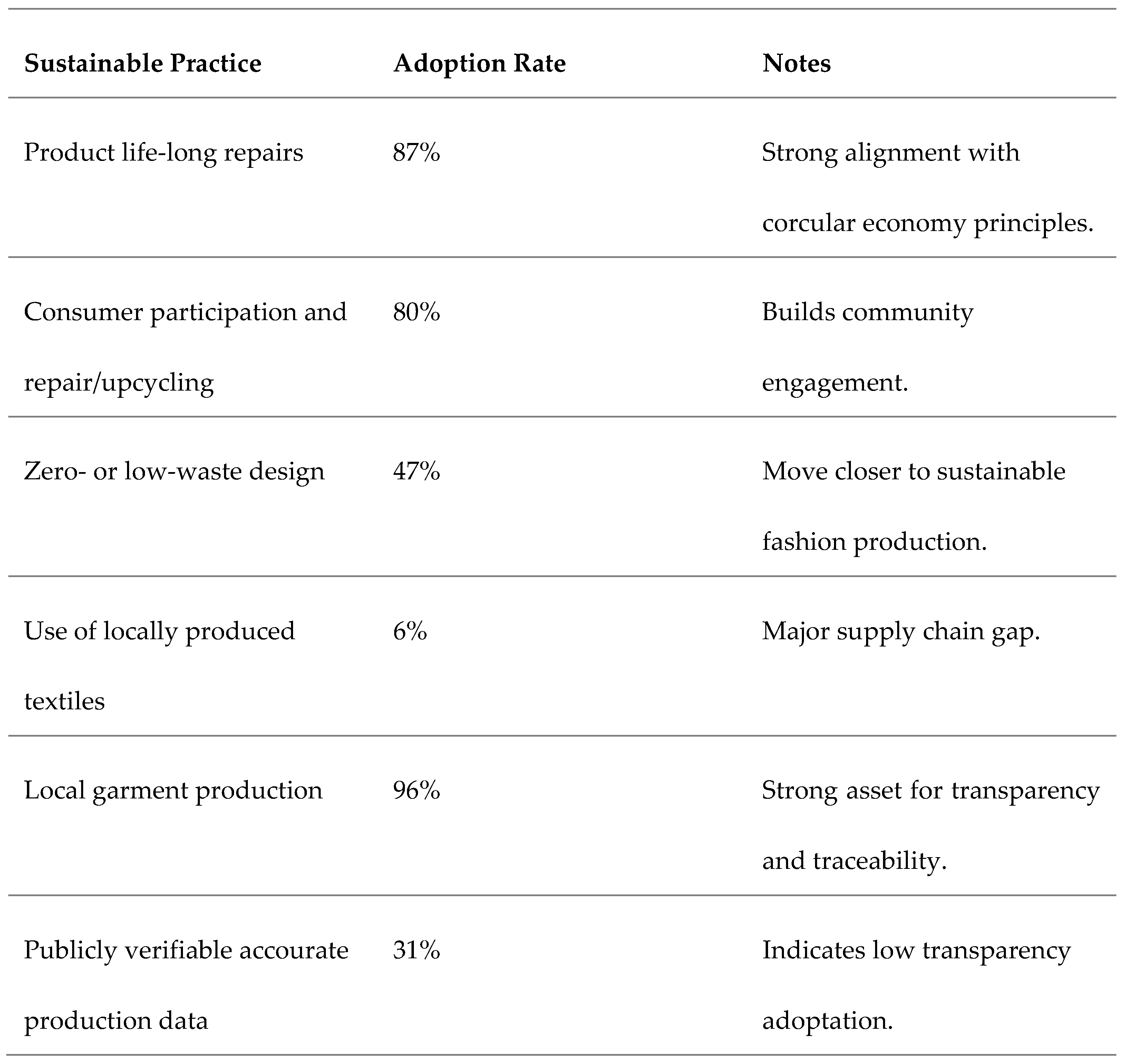

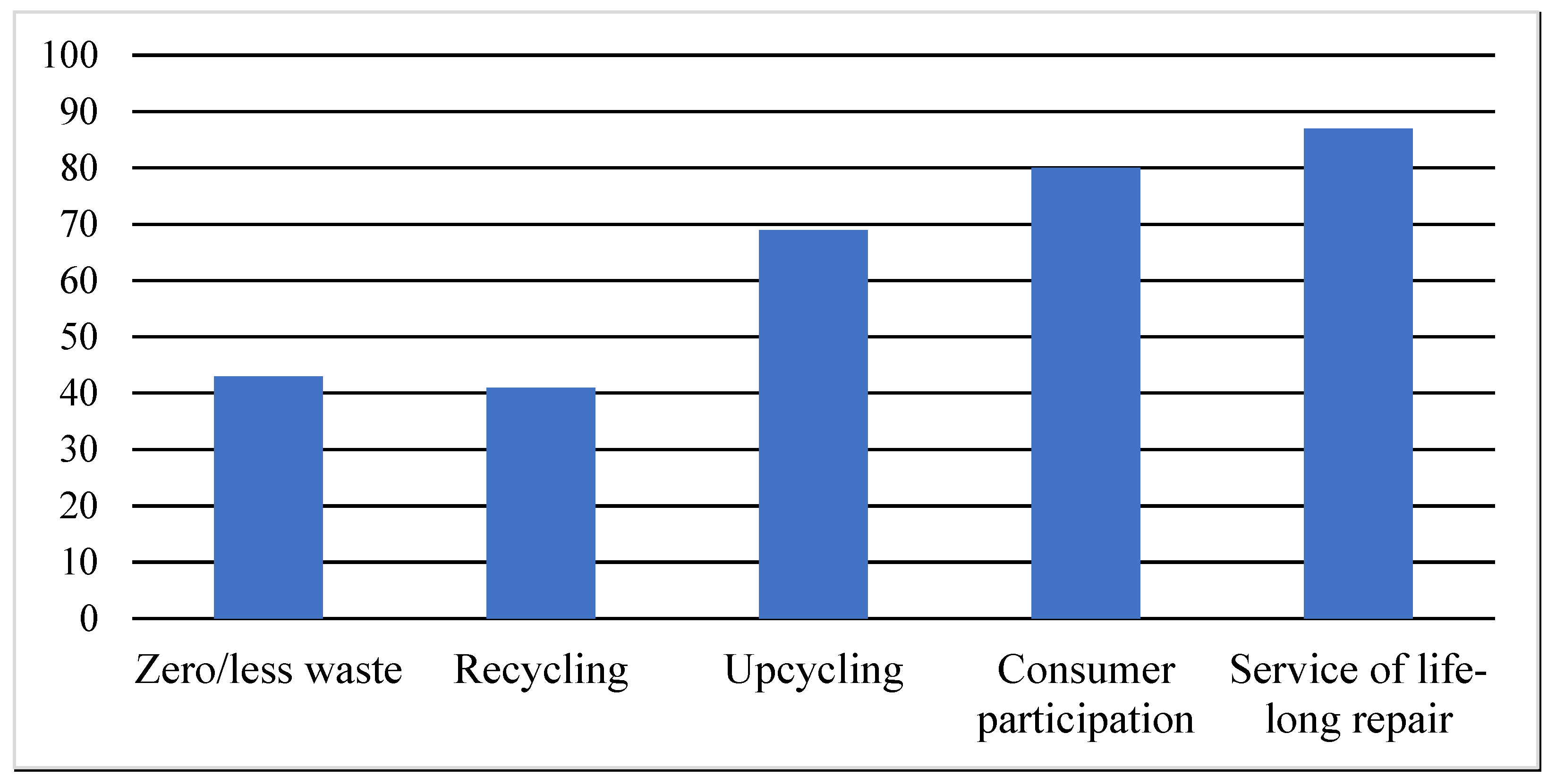

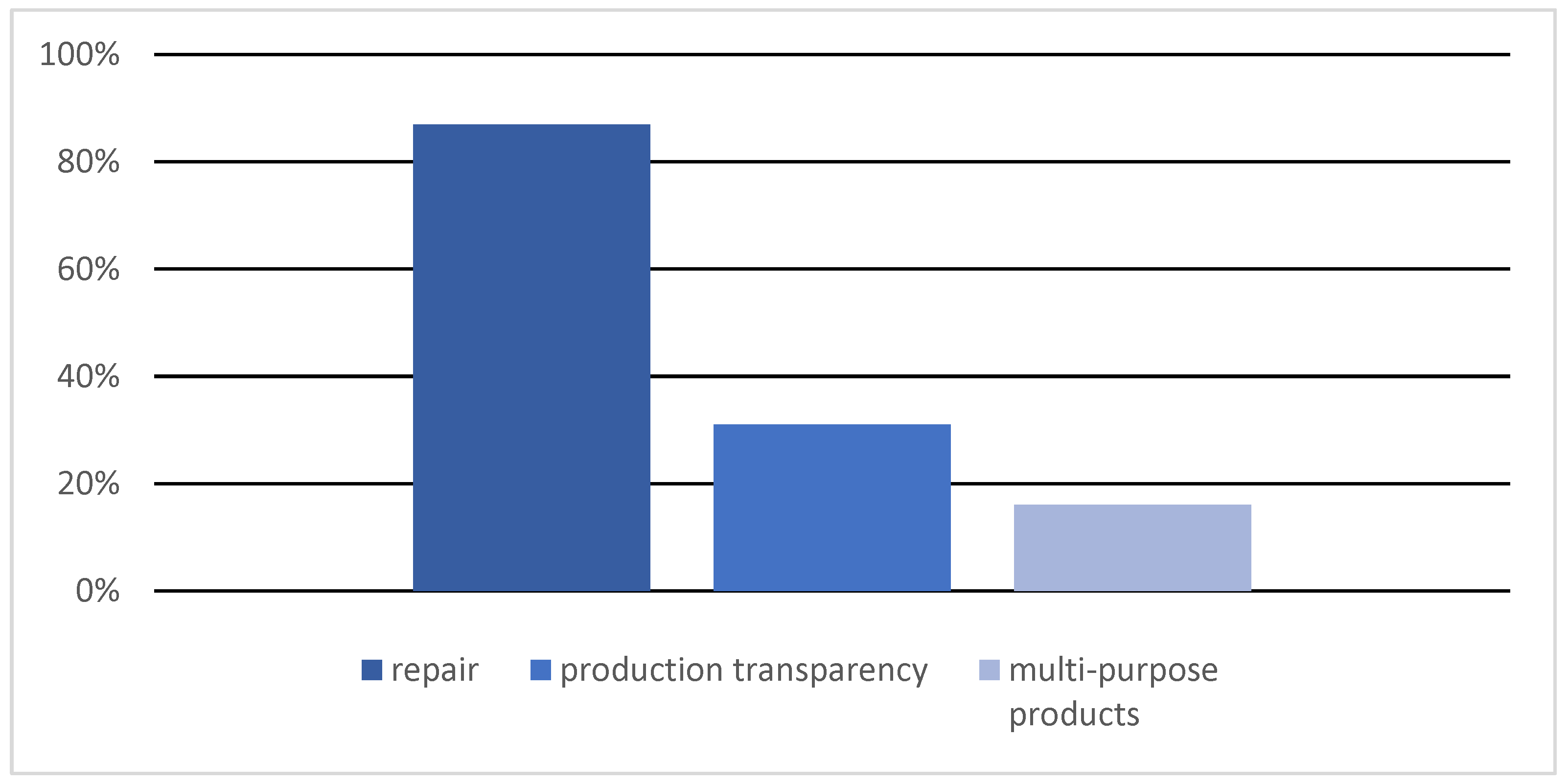

- The results showed that 69% employed some form of upcycling, 87% offered repair or alteration services, 41% integrated zero- or less- waste tailoring, and 40% actively revived traditional craft techniques.

- These statistics provided a baseline for assessing the prevalence and diversity of sustainability strategies in Slovenia’s fashion sector.

3. Sustainability Concepts of Slovenian Fashion Brands in the Socialist and Post-Socialist Periods

3.1. Historical Sustainability-Oriented Foundations of Slovenian Fashion: A Legacy for Contemporary Practices

3.2. Current Practices: Analysis of Contemporary Sustainabilty-Oriented Slovenian Fashion

- Zero-waste or reduced-waste tailoring, emphasizing pattern efficiency and material optimization;

- Recycling and upcycling, with a particular focus on how existing garments are reintroduced into circulation;

- Design for adaptability and longevity, involving modularity, repairability, and continuous product improvement;

- Consumer participation in the design process, highlighting co-creation as a means of extending product value;

- Digital engagement through social media, used both as an educational tool for sustainable fashion and as a platform for sharing brand narratives;

- Community-building practices, where brands initiate and foster fashion communities around sustainability values;

- Repair services, offered as lifelong product support to slow down fashion consumption and counteract the prevailing “clothing metabolism” [20] (p. 89).

4. Contemporary Sustainability-Oriented Fashion Identity in Slovenia

4.1. Sustainable Fashion Practices in Slovenia

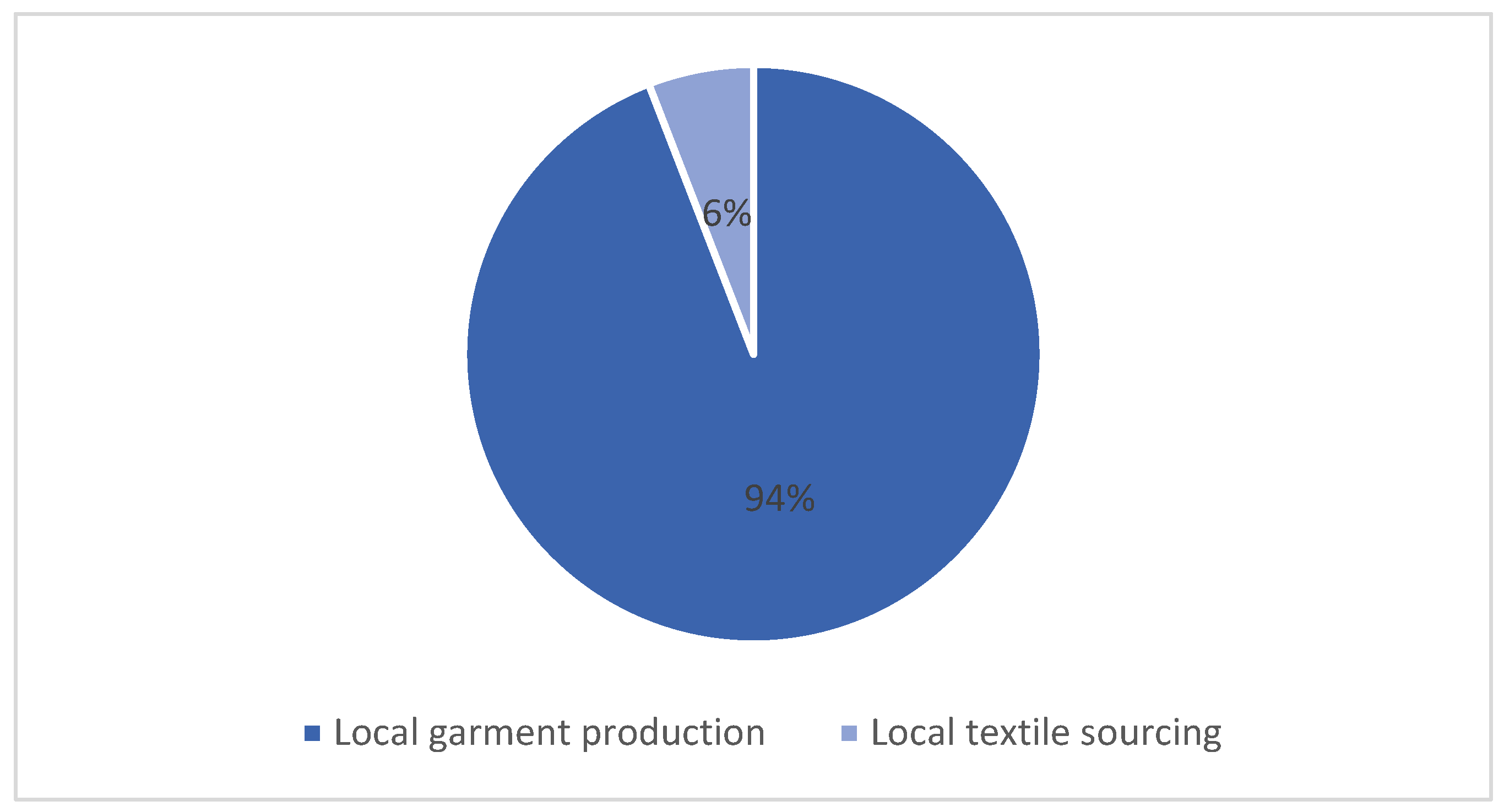

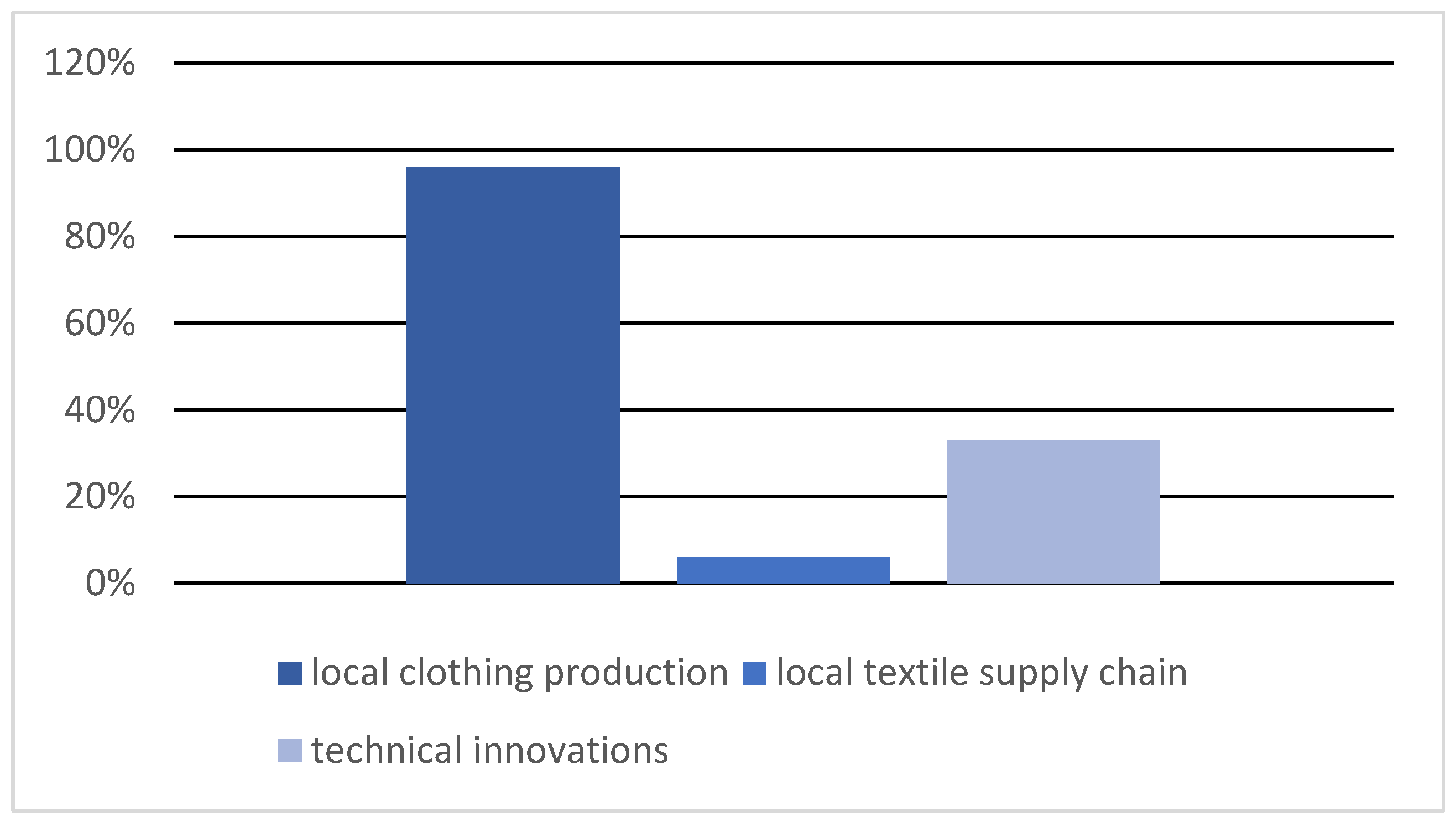

4.2. Startegic Opportunities for Local Production

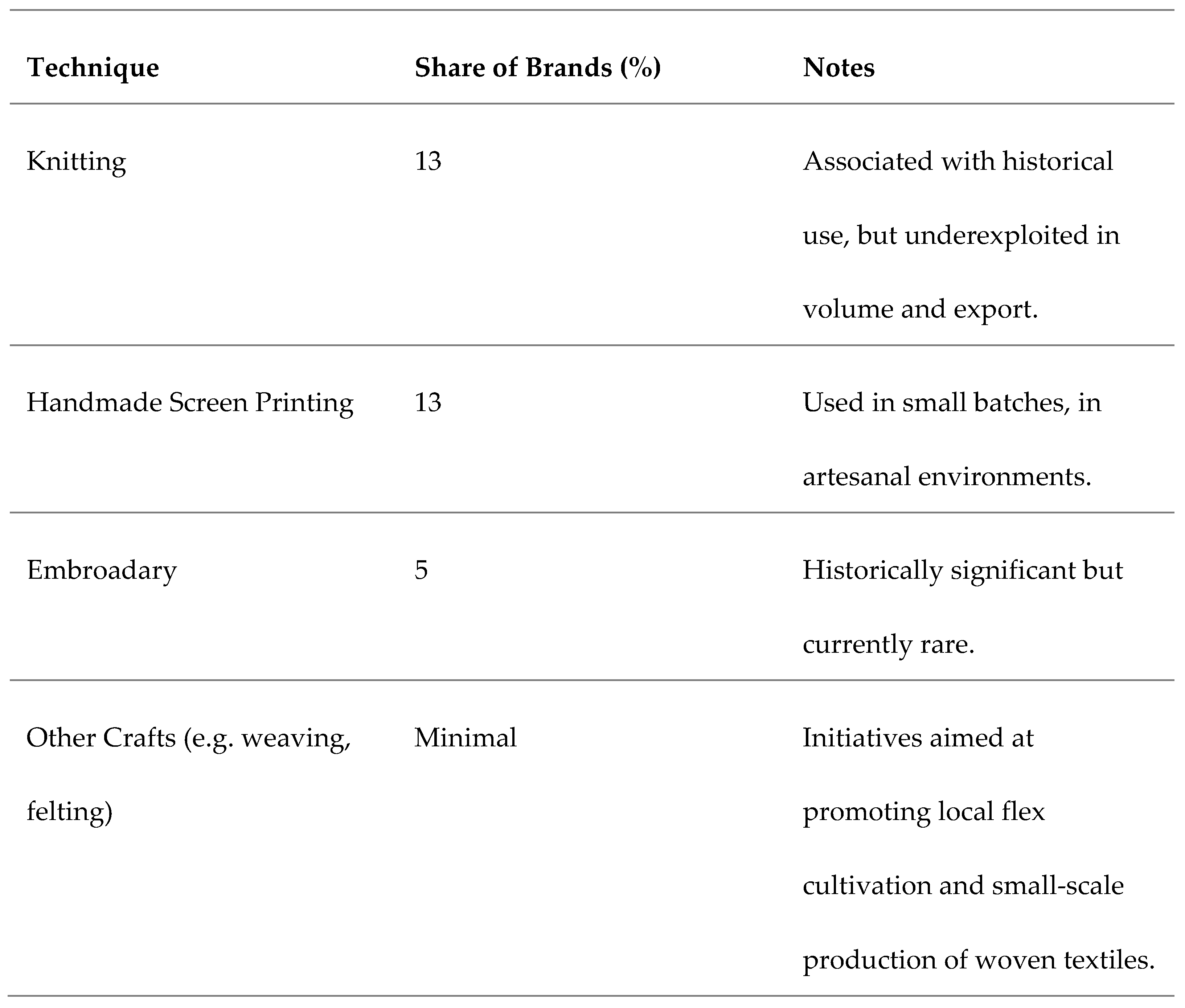

4.3. The Role of Craftsmanship and Cultural Heritage

5. Discussion

5.1. Strategic Vision for Slovenian Sustainability Fashion

- Institutional leadership: Establishment of a professional chamber, or governing body to serve as custodian of the sector’s vision in fulfiling sustainability strategies. This organization should foster cross-sectoral collaboration, across policy makers, educational institutions, designers, and enterpreneurs.

- Digital Platforms: Development of a comprehensive platform of Slovenian fashion brands with clear sustainability strategies, intended for presentations, promotion, and education.

- Promotion and Market Positioning: Stregthening both domestic and international promotion of Slovenian sustainability-oriented fashion brands. Emphasis should be placed on niche, sustainably focused production to increase market differentiation. The ’Made in Slovenia’ label could include a segment dedicated to sustainable fashion, thereby reinforcing cultural authenticity and sustainable value.

- Sustainability and Heritage Integration: Preservation and innovation within traditional handicrafts, linking heritage techniques with sustainable practices such as zero-waste design, natural dyeing, and the use of locally sourced materials. A hybrid integration of craft and modern technology can create high-value, export-oriented products.

- Circular Economy Theory: Craft-based micro-production supports circularity with local sources, minimal waste and short supply chains.

- Post-socialist Transition Insights: Fashion, whose economic, political and social changes have influenced its development, struggles with small-scale production, restrictions on the global market and structural obstacles in transition economies.

- Cultural Heritage Preservation Theory: It emphasizes the importance of incorporating and developing handicraft skills in the preservation of intangible cultural assets, while also linking heritage preservation with economic and environmental sustainability outcomes.

- Policy Recommendations: Support cooperative production hubs, grants for sustainable craft innovations, and certification schemes that emphasize cultural sustainability authenticity.

- Industry Guidelines: Promote hybrid integration of craft and technology, collaborative production models, and transparency through the use of digital tools to increase efficiency and competitiveness in the market.

- Educational Implications: Develop curricula that combine traditional craft skills with sustainable design principles to educate future fashion designers.

5.2. Limitations and Future Reserach

- Conduct studies to monitor changes in the implementation of sustainable practices or strategies over time.

- Undertake cross-national comparisons with other post-socialist transitional and small-scale fashion systems.

- Explore digital platforms to preserve artisanal heritage, increase transparency, and develop a sustainable fashion identity.

6. Conclusions

References

- Fletcher, K. Sustainable Fashion and Textiles: Design Journeys, 1st ed.; Earthscan: London, England, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 04. 08. 2025).

- McCracken, G. Culture and Consumption: A Theoretical Account of Structure and Movement of the Cultural Meaning of Consumer Goods. Journal of Consumer Research 1986, 13, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K.; Grose, L. Fashion & Sustainability: fashion for change; Laurence King Publishing: London, England, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Manzini, E. Design, when everybody designs: An introduction to design for social innovation. MIT Press: Cambridge, USA, 2015.

- Sektor mode v Sloveniji. Center za kreativnost: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2025.

- Braun, V.; Clark, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psycology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bole, P. Muzealizacija Almire. In Preteklost oblikuje sedanjost: Zbornik ob razstavi Alpska modna industrija Almira-Preteklost oblikuje sedanjost; Devetak, T.; Muzeji radovljiške občine: Radovljica, Slovenia, 2020; pp. 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Oblak Japelj, N. Knjižnica Industrije usnja Vrhnika:pridobitev domoznanske zbirke Cankarjeve knjižnice Vrhnike. In Usnjarstvo na Slovenskem: zbornik referatov; Hudales, J.; Muzej Velenje, Muzej usnjarstva na Slovenskem: Šoštanj, Slovenia, 2013; pp. 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Banka Slovenije. Available online: https://www.bsi.si/sl/statistika/devizni-tecaji/zgodovina-deviznih-tecajev-1945-1998 (accessed on 04. 08. 2025).

- Podbevšek, A. Pletenina se je izkazala. Jana 1979, 37, 11. [Google Scholar]

- M. K. Tekstil kupi inkubator. Jana 1979, 20, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Podbevšek, A. Nihče nam ne gleda pod prste. Jana 1983, 23, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Kobe Arzenšek, K. Pletenina: tovarna trikotažnega perila: zgodovinski zapis ob trojnem jubileju; Pletenina, tovarna trikotažnega perila Ljubljana: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Ladika, N. Problematika tekstilne industrije. Vezilo 1975, 11, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Babič, K.; Dabič Perica, S. Aplikativna analiza stanja na področju socialne ekonomije v Republiki Sloveniji. 2018. Available online: http://brazde.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Analiza-stanja-na-podro%C4%8Dju-socialne-ekonomije-v-Sloveniji.pdf (accessed on 28. 07. 2025).

- Coscieme, L.; Manshoven, S.; Gillabel, J.; Grossi, F.; Mortensen, L. F. A Framework of circular business models for fashion and textiles: The role of business-model, technical, and social innovation. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 2022, 18, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/apparel/slovenia (accessed on 20. 05. 2025).

- Sektor mode v Sloveniji. Center za kreativnost: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2025.

- Fletcher, K.; Grose, L. Fashion & Sustainability: fashion for change; Laurence King Publishing: London, England, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Celcar, D. Trajnost in tehnologija v modni industriji. In Preteklost oblikuje sedanjost: Zbornik ob razstavi Alpska modna industrija Almira-Preteklost oblikuje sedanjost; Devetak, T.; Muzeji radovljiške občine: Radovljica, Slovenia, 2020; pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jerič, P. Trajnostno biorazgradljiva oblačila za modno znamko Vivre (magistrsko delo). Univerza v Ljubljani, Naravoslovnitehniška fakulteta, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2022.

- Ladika, N. Problematika tekstilne industrije. Vezilo 1975, 11, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Eržen, S. Shirting. Mladina 2016, 32, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, A. Decolonizing Fashion: Defying the ‘White Man’s Gaze’. Available online: http://vestoj.com/decolonialising-fashion/ (accessed on 12. 11. 2020).

- Cater, L. Brussels turns to ’artisanal skills’ to mend the textile industry. Politico. Available online: https://www.politico.eu/article/brussels-artisanal-skills-mend-textiles-industry-europe-fast-fashion/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 12. 5. 2025).

- Stupica, M. Naša tekstilna industrija. Maneken 1957, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Fajt, E. Alternativne prakse v modi. In Moda in kultura oblačenja; Pušnik, M. in Fajt, E.; Aristej: Maribor, Slovenia, 2014; pp. 147–163. [Google Scholar]

- Rakovec, B. Dobrodošli v Grimščah. Jana 1985, 24, 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- N.N. Blejski pušeljc v Tekstilindusovih oblekah. Jana 1979, 21, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Anselma. Available online: https://anselma.si/about (accessed on 20. 7. 2025.

- Britovšek S. Mariborska ustvarjalka Tina Princ: Česar ne najde, kar pogreš, tisto ustvari. Večer 2021. Available online: https://vecer.com/v-nedeljo/mariborska-ustvarjalka-tina-princ-cesar-ne-najde-kar-pogresa-tisto-ustvari-10236259 (accessed on 5. 5. 2025).

- Center za kreativnost. Available on: https://czk.si/priloznosti/vili-van-style-odprti-poziv-za-vse-mlade-blagovne-znamke/ (accessed on 4. 8. 2025).

- Hishka. Available on: https://hishka.com/about/ (accessed on 30. 9. 2024).

- Big See. Available online: https://bigsee.eu/sewists-appetite/ (accessed on 5. 12. 2024).

- D’Itria, E.; Aus, R. Circular fashion: Evolving practices in a changing industry. Science, Practice and Policy 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sektor mode v Sloveniji. Center za kreativnost: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2025.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).