1. Introduction

Wood–polymer composites (WPCs) are considered promising materials due to their advantageous operational characteristics and broad applicability across various industrial sectors [

1]. WPCs can be manufactured using a variety of processes, including extrusion, injection molding, and compression molding, depending on the intended geometry and application of the final product [

1]. Among these, extrusion is the most commonly employed method for WPCs production in the United States and Europe [

2], primarily used to create continuous profiles with limited cross-sectional complexity. In addition to extrusion, WPCs can also be produced via flat pressing in hot presses [

3,

4,

5]. This hot-pressing method has been the focus of significant academic research aimed at improving the structural and functional performance of flat-pressed WPCs (FPWPCs) [

3,

4,

5]. Mathematical models have been developed to support the optimization of the hot-pressing process, enhancing efficiency and product consistency [

6]. A critical yet often underexplored aspect of FPWPC production is the post-pressing cooling stage, which plays a crucial role in consolidating the composite’s final properties. Although some studies refer to this stage simply as the final cooling phase—typically concluding when the material reaches approximately 50 °C—they often lack a detailed examination of key process parameters, such as cooling time and the temperature of the cooling surfaces [

4,

7].

Previous research has investigated optimal cooling strategies for thermoplastic composites in the post-manufacturing phase [

8]. One such study focused on determining the most effective cooling regime to reduce processing time during the cooling stage of APC-2 laminate press molding. Additionally, an experimental investigation examined the thermal dissipation behavior of WPCs that were initially heated to 150 °C in an electric furnace and subsequently cooled at ambient conditions (21 °C) [

9].

Despite the recognized importance of the thermal dissipation stage in the production of flat-pressed wood–polymer composites (FPWPCs), a review of the existing literature reveals a significant gap in research addressing the mathematical modeling of the cooling process in these materials. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to develop a mathematical model capable of predicting the cooling duration of FPWPCs produced in periodical action presses. The goal was to determine the optimal cooling time required for the core layer of the composite to reach the polymer solidification temperature.

2. Development of the Mathematical Model

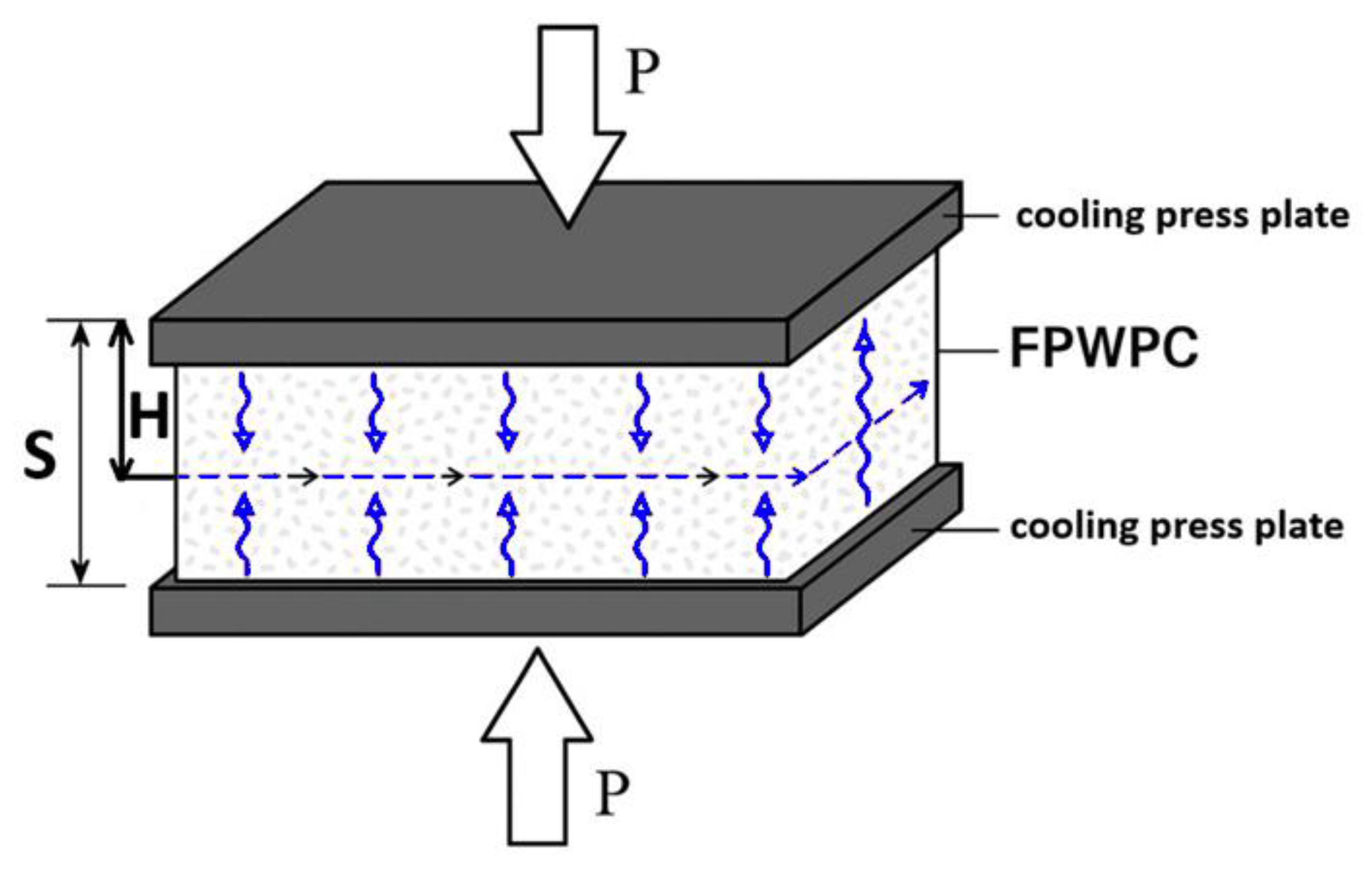

The time required to close and open the press plates, and the time to increase and decrease the pressure, are determined by the type of the flat pressing equipment and any modifications to it. Primarily, the cooling time for FPWPC panels is determined by the time to reach a predetermined temperature in the core layer (

H) (

Figure 1).

In the case of a one-dimensional, transient heat transfer process, the heat conduction equation (based on Fourier's Law) takes the following form:

where,

T (x,t) - temperature at point

x at time

t; α – the thermal diffusivity (α), a property determined by:

where, λ

eff – effective thermal conductivity of FPWPC;

ρ – density of FPWPC;

Cfpwpc – heat capacity of the FPWPC.

FPWPC consists from wood particles and thermoplastic polymer, therefore effective thermal conductivity of FPWPC can be calculated using formula:

where,

λwood and

λpol – are the thermal conductivities of wood and polymer, respectively;

φwood is the volumetric fraction of wood particles in the composite material, expressed as a fraction.

Therefore, the volumetric fraction of wood particles can be calculated in the following manner:

where,

VWPC is volume of FPWPC and

Vwood is the volume of wood particles within the FPWPC.

The thermal conductivities of wood and thermoplastic polymer (in our mathematic we will choose high-density polyethylene (HDPE)) are determined using experimental linear equations [

10]:

The specific heat capacity of the FPWPC can be calculated using the following equation:

where,

сWwood and

сpol are the specific heat capacities of moist wood particles and thermoplastic polymer, respectively.

Then the specific heat capacity of moist wood particles, considering their moisture content, can be determined as follows [

11]:

The specific heat capacity of a HDPE is temperature dependent and can be calculated by [

12]:

An explicit scheme of the finite difference method is used for the numerical solution. The discretization in time and space is presented as follows.

Spatial step:

where, S – thickness of FPWPC (S = 2 H).

The discretization of the Fourier equation results in:

where,

Tin — temperature at the

i- th node at the

n-th time step;

Ti-1n, Ti+1n – temperature at the adjacent nodes;

– dimensionless coefficient.

Subsequently, the initial conditions can be formulated in the following manner.

At the onset of the modelling process, the temperature distribution is defined through the thickness of the FPWPC:

And boundary conditions will be:

Within the numerical discretization:

The finite element method (FEM) was employed as the numerical approach for solving the boundary value problem. FEM is based on the principle of approximating a continuous function with a discrete model composed of piecewise continuous functions, defined over a finite number of subdomains known as finite elements. The geometric domain of interest is discretized into these elements, within which the unknown function is approximated using trial functions. These trial functions are required to satisfy both inter-element continuity and the boundary conditions specified by the problem.

To implement the developed model, the Matlab R2021b (9.11) computational environment (MathWorks, Natick, MA 01760-2098, USA) was utilized, specifically the Matlab Partial Differential Equation Toolbox (PDE Toolbox), which supports FEM-based simulations. The toolbox's graphical user interface (GUI), accessed via the functions “pdeinit” and “pdetool”, facilitates the interactive setup of the PDE model. This includes defining the geometry of the domain, specifying boundary conditions, selecting the equation type and its coefficients, generating a computational mesh, solving the problem, and visualizing the results.

Given that surface temperature after pressing, wood mass fraction, and board density are variable factors in the cooling process, a custom Matlab function, “calculate.m”, was developed. This function accepts these parameters as input and returns numerical simulation results—specifically, temperature distributions at the mesh nodes over time, presented in matrix form.

Graphical representations of the simulated data were generated for an FPWPC sample with a thickness of 18 mm, assuming constant cooling platen temperatures of 25 °C. The initial temperature of the core layer was set at 120 °C. The simulation was concluded when the temperature at the composite’s core decreased to 50 °C.

The parameters varied in the simulation of the FPWPC cooling model are summarized in

Table 1.

3. Results

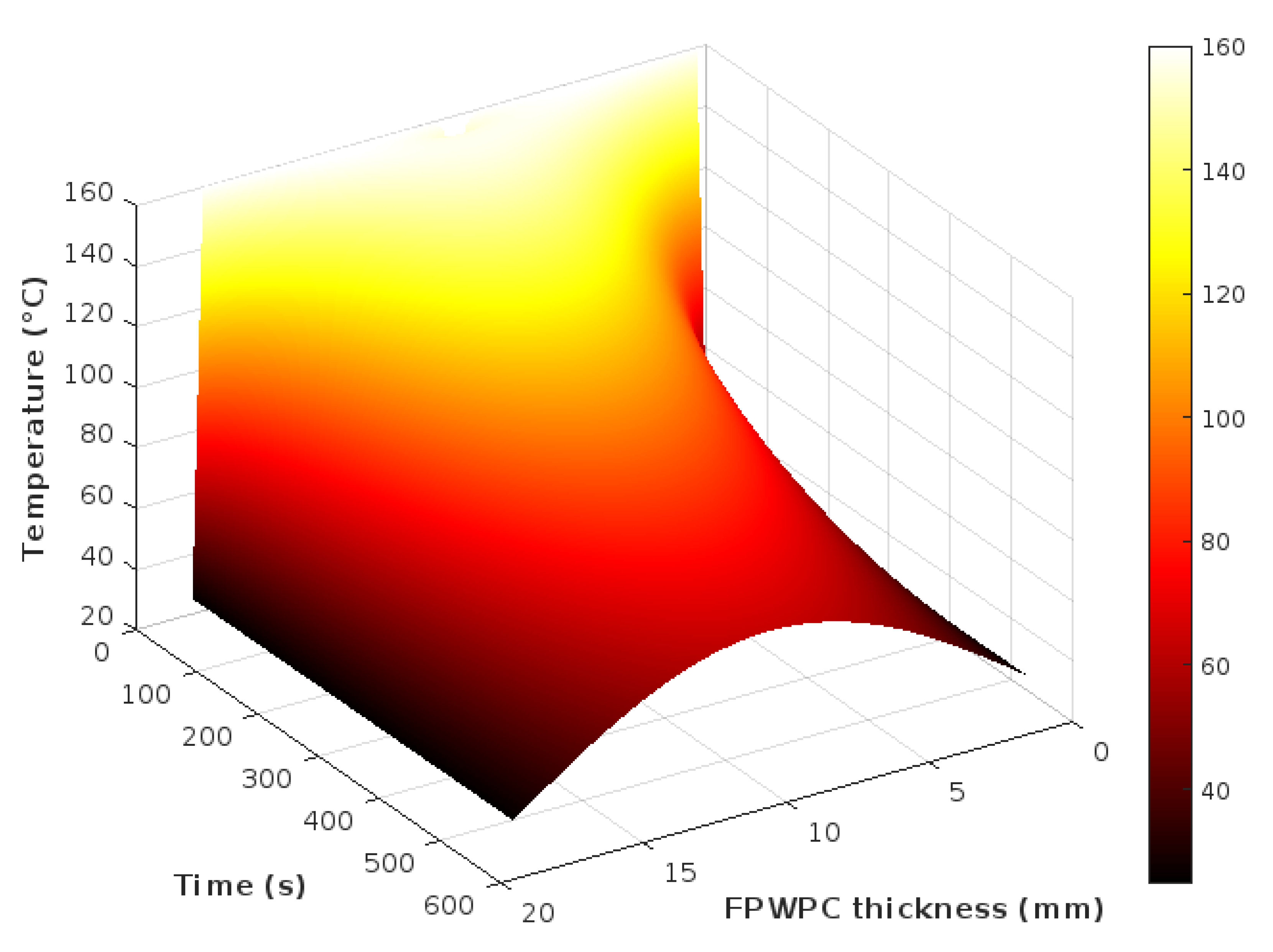

The execution of the mathematical model yielded a plotted relationship illustrating the dependence of the FPWPC cooling time on its initial surface temperature, as well as the spatiotemporal temperature distribution across the material’s cross-section throughout the entire cooling cycle (

Figure 2).

The non-uniform cooling behavior of FPWPC along its thickness is evident and results from the varying heat transfer rates in different layers of the composite. At the onset of the cooling phase, the surface regions exhibit the highest temperature, corresponding to the press plate temperature during the hot-pressing stage. In contrast, the core layer initially exhibits a lower temperature—approximately 10 °C above the fusion temperature of the thermoplastic polymer [

6]. However, as cooling progresses, the surface layers are the first to experience a temperature drop, while the core temperature continues to rise due to thermal inertia. This heat redistribution from the surface to the core creates a steep temperature gradient across the thickness of the material.

Temporally, the cooling of the FPWPC core layer can be divided into three distinct phases:

initial temperature rise (0 - ~40 s);

thermal maximum (~40 - ~60 s);

convective cooling phase (~60 - ~800 s).

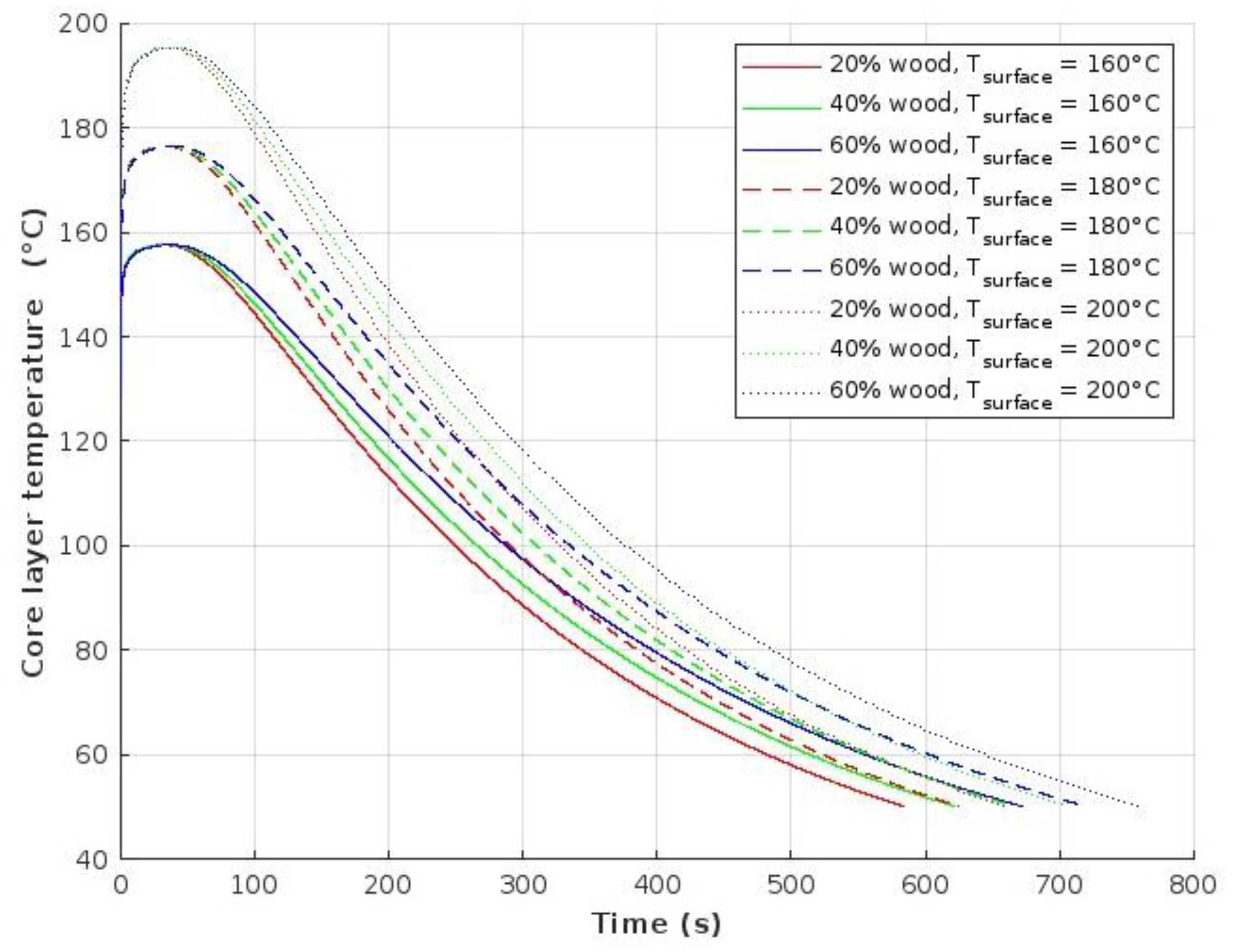

In the first phase—the initial temperature rise (0–~40 s)—a rapid increase in the core temperature is observed, particularly during the first 10–20 seconds. This occurs due to the significant temperature difference between the hotter surface layers and the cooler core. As heat from the surface begins to conduct inward, the core temperature increases sharply, driven by the established thermal gradient. The rate and duration of this temperature rise are influenced by factors such as the initial surface temperature, wood particle content, and bulk density of the FPWPC (

Figure 3). A greater temperature gradient between the surface and the core layers leads to a longer transition period before the composite enters the cooling phase proper. It is important to note that the core temperature does not rise instantaneously; rather, it increases progressively as thermal energy accumulates in the upper layers before being conducted inward.

The second stage of the cooling process, referred to as the thermal maximum phase (~40–60 s), is characterized by the attainment of a peak temperature within the core layer of the FPWPC. This peak occurs as a result of delayed heat transfer into the core, a phenomenon governed by the thermal inertia of the composite. Initially, heat accumulates in the surface layers due to their direct exposure to the hot press plates. As the cooling process begins, this accumulated heat gradually diffuses inward, resulting in a temperature rise within the core and ultimately forming a distinct temperature peak.

Once the temperature in the core layer reaches its maximum, heat begins to dissipate more rapidly due to two simultaneous processes:

The part of the heat is transferred from the core to adjacent, cooler layers;

The surface of the composite, already in contact with the press cooling plates, begins to cool, reducing the thermal influx into the interior.

As a result, the core temperature gradually begins to decline, marking the transition to the third cooling phase. Notably, the magnitude and timing of the thermal peak are strongly influenced by both the initial surface temperature and the wood particle content of the FPWPC. A higher initial surface temperature (e.g., 200 °C) results in a more pronounced and earlier peak. Similarly, increasing the wood particle content delays the thermal maximum and elevates its magnitude due to wood’s lower thermal conductivity compared to the thermoplastic matrix. For instance, at 20% wood content, the temperature peak is lower and cooling begins sooner, whereas at 60%, the peak is higher and occurs later, indicating enhanced heat retention.

This phase can be further subdivided into three sub-phases:

Rapid temperature peak, especially for composites with high initial surface temperatures (e.g., 200 °C);

Gradual temperature stabilization, where the rate of increase levels off;

Onset of temperature decline, indicating transition into the cooling phase.

The third stage—the cooling phase (~60–800 s)—begins once the core temperature peaks and subsequently decreases exponentially. The core does not cool instantaneously; rather, heat continues to transfer into deeper layers before being fully dissipated. During the early moments of this phase, a significant temperature gradient between the composite surface and the press plates drives rapid heat transfer. However, as this gradient diminishes, the cooling rate progressively slows. This transition typically occurs between 300 and 400 seconds.

The cooling rate in this phase remains dependent on both the initial surface temperature and wood content. FPWPCs with higher initial surface temperatures cool rapidly at first but exhibit slower rates later in the cycle. Meanwhile, composites with higher wood content (60%) exhibit slower overall cooling due to wood's lower thermal conductivity and greater thermal mass. As cooling progresses, the temperature curves of the core layer gradually converge toward an asymptotic value, stabilizing around 50 °C—the target temperature indicating the completion of the cooling process.

The time evolution of this phase can be divided into two distinct sub-phases:

Fast cooling (~160–~300–400 s): Characterized by a rapid temperature drop accounting for approximately 50–70% of the total cooling time. This stage is dominated by radiative and convective heat loss;

Slow stabilization cooling (~300–400–800 s): The rate of cooling diminishes as thermal gradients decrease and the temperature in the core layer approaches equilibrium. Eventually, the core layer temperature stabilizes near the target threshold of 50 °C.

Comparison of the model-generated cooling curves with experimental results reported in [

9] shows strong similarity. However, it is important to note that the referenced study measured surface temperatures under ambient cooling conditions, whereas the present model simulates forced cooling between press plates—conditions more representative of industrial FPWPC production.

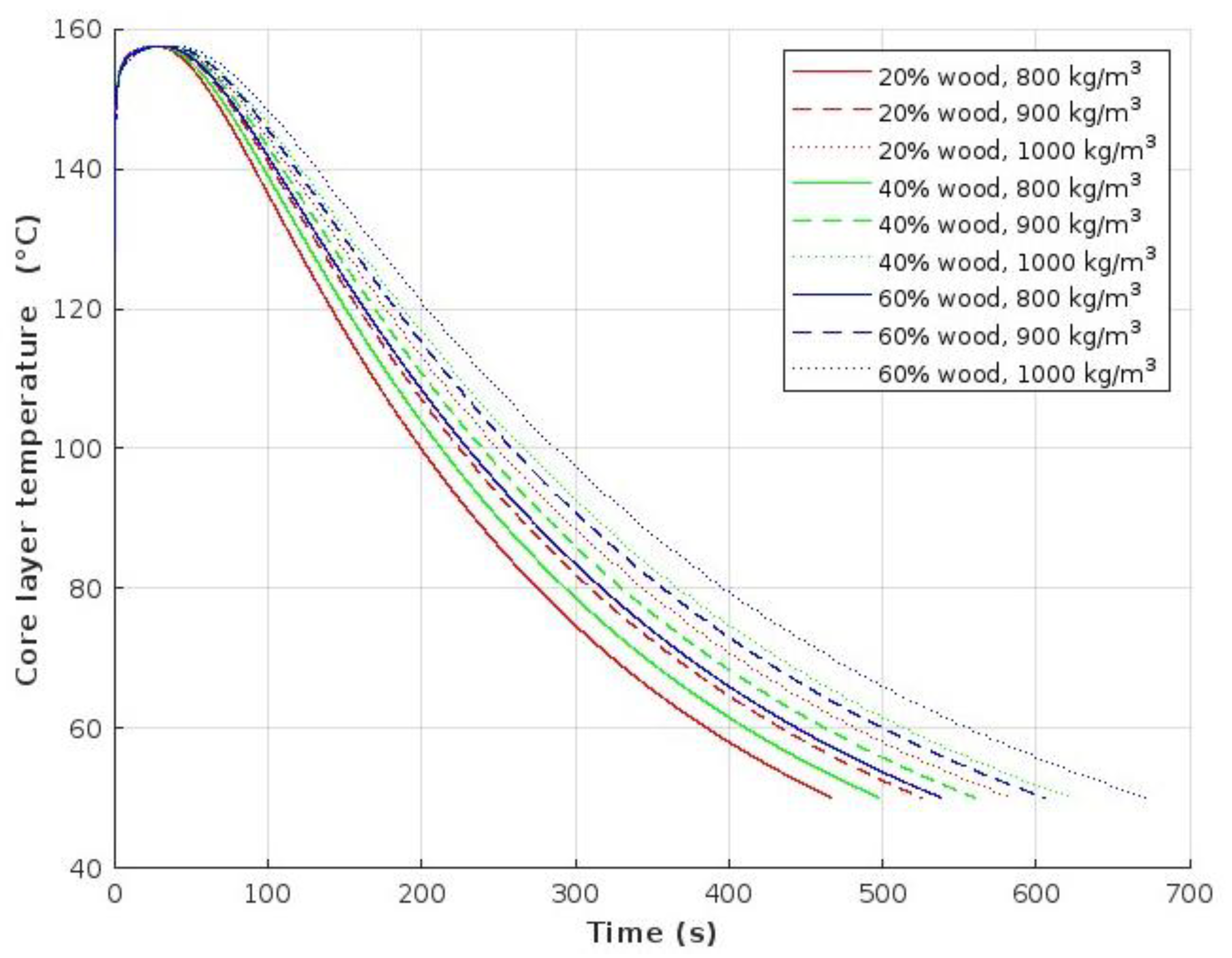

Additionally, the simulation revealed that composites with higher bulk densities (e.g., 1000 kg/m³) cool more slowly than those with lower densities (e.g., 800 kg/m³), due to increased thermal mass and reduced heat transfer efficiency (

Figure 4).

This behavior can be attributed to the fact that as the density of the FPWPC increases, so does its mass and, consequently, its capacity to store thermal energy. As a result, denser composites require more time to dissipate the accumulated heat, leading to a slower cooling rate. Although materials with higher density often exhibit greater thermal conductivity—promoting faster internal heat transfer—this effect is frequently outweighed by the increased heat capacity. Therefore, the net effect is that denser FPWPCs tend to cool more slowly than their less dense counterparts.

4. Conclusions

It was observed that the cooling of flat-pressed wood–polymer composites (FPWPCs) is a non-linear process, characterized by an initially rapid temperature drop followed by a gradual deceleration. One of the key factors influencing the cooling rate is the wood particle content. An increase in wood content leads to a reduction in thermal conductivity, thereby slowing down heat transfer and prolonging the cooling duration of the composite’s inner layers. In addition to wood content, the thickness of the FPWPC significantly impacts the cooling behavior. While the surface layers cool rapidly due to direct exposure to the cooling plates, the core retains heat for a longer period, resulting in a pronounced delay in reaching thermal equilibrium. The initial surface temperature also plays a critical role. A higher initial surface temperature extends the pre-cooling phase, delaying the onset of actual cooling in the core. However, once cooling begins, composites with higher initial temperatures exhibit a faster initial cooling rate due to the larger temperature gradient. This effect is temporary, as a noticeable slowdown typically occurs between 300 and 400 seconds into the cooling process. The bulk density of the FPWPC further influences cooling performance by affecting its heat capacity, thermal conductivity, and overall heat dissipation efficiency. Lower-density composites cool more rapidly, while higher-density composites retain heat for longer durations. This difference becomes especially pronounced after approximately 100 seconds of cooling, when thermal inertia in denser materials begins to dominate the process. The developed mathematical model can be applied to calculate the cooling time of flat-pressed wood–polymer composites (FPWPCs) fabricated with various thermoplastic polymer matrices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, methodology, software, validation, and formal analysis—P.L. and P.B.; investigation, resources, and data curation—P.L., P.B., and J.S.; text drafting—P.L. and P.B.; text review and editing—P.L., P.B., and J.S.; visualisation and supervision—P.L. and P.B.; supervision—P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the EU NextGenerationEU through the Recovery and Resilience Plan for Slovakia under project no. 09I03-03-V01-00124.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the authors. Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported: by the EU NextGenerationEU through the Recovery and Resilience Plan for Slovakia under project No. 09I03-03-V01-00124, and by the Slovak Research and Development Agency under the contracts No. APVV-18-0378, APVV-22-0238 and by the project VEGA 1/0450/25.

Conflicts of Interest

Pavlo Lyutyy was employed by the company Green Cotton Group A/S. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Klyosov, A.A. Wood plastic composites. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, 2007; 726 рр.

- Rowell R.M. Handbook of wood chemistry and wood composites. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2005; 487 pp.

-

Ayrilmis, N.; Jarusombuti, S. Flat-pressed wood plastic composite as an alternative to conventional wood based panels. J. Compos. Mater. 2011 45: 103–112. [CrossRef]

-

Benthien, J.T.; Thoemen, H. Effects of raw materials and process parameters on the physical and mechanical properties of flat pressed WPC panels. Compos. Part A-Appl. S. 2012, 43(3), 570–576. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesa.2011.12.028.

-

Lyutyy, P.; Bekhta, P.; Sedliacik, J.; Ortynska, G. Properties of flat-pressed wood-polymer composites made using secondary polyethylene. Acta Fac. Xylologiae Zvolen 2014, 56(1), 39–50.

-

Lyutyy, P.; Bekhta, P.; Hot-Pressing Process of Flat-Pressed Wood-Polymer Composites: Theory and Experiment. Polymers 2024, 16(20), 2931; [CrossRef]

-

Benthien, J.T.; Thoemen, H. Effects of agglomeration and pressing process on the properties of flat pressed WPC panels. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2013, 129(6), 3710-3717. [CrossRef]

- Sonmez, F. O., and Eyol, E. (2002). Optimal post-manufacturing cooling paths for thermoplastic composites, Compos. Part A-Appl. S. 33(3), 301–314. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, S.; Toghyani, A.E.; Eskelinen, H.; Kärki, T.; Varis, J. Manufacturability of Wood Plastic Composite Sheets on the Basis of the Post-Processing Cooling Curve. BioResources 2015, 10(4), 7970–7984. [CrossRef]

- Prisco, U. Thermal conductivity of flat-pressed wood plastic composites at different temperatures and filler content. Science and Engineering of Composite Materials 2014, 21, 2, 197–204. [CrossRef]

- Thoemen, H.; Humphrey, P.E. Modeling the physical processes relevant during hot pressing of wood-based composites. Part I. Heat and mass transfer. Holz als Roh- und Werkstoff 2005, 64(1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Gaur, U.; Wunderlich, B. Heat capacity and other thermodynamic properties of linear macromolecules. II/ Polyethylene. Journal of Physical Chemistry 1981, 10(1), 119–152.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).