Submitted:

16 April 2025

Posted:

18 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

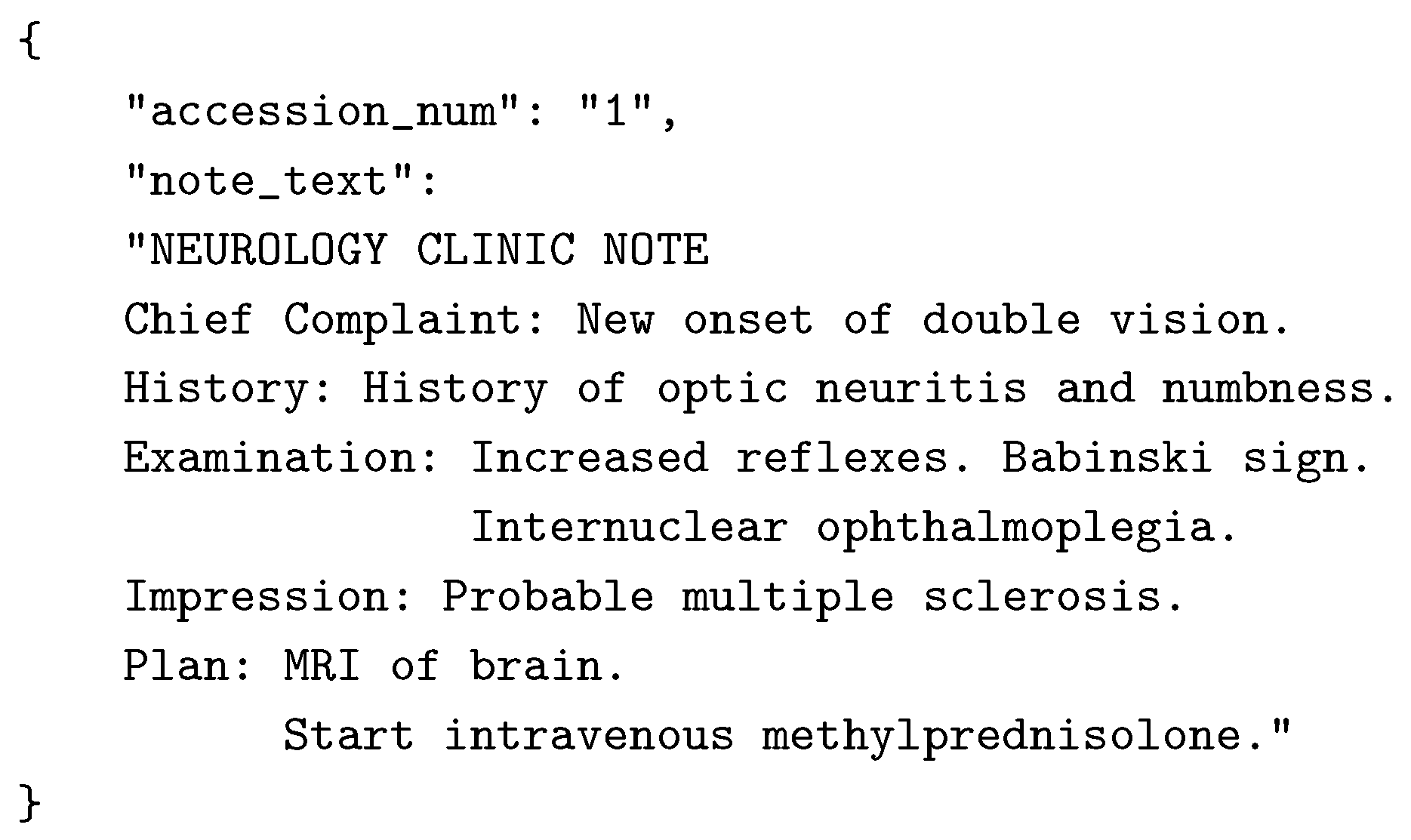

- Expanding abbreviations based on context (e.g., MS” → multiple sclerosis’’ or mental status”).

- Correcting typographical and grammatical errors to improve clarity [43].

- Replacing colloquialisms and dictation artifacts with standardized terminology (e.g., heart attack’’ → “myocardial infarction’’) [44].

- Structuring notes into canonical sections (e.g., History, Examination, Impression, Plan) to enhance navigability.

- Enhance the readability and clinical utility of notes.

- Improve the accuracy of pipelines that extract and normalize medical concepts to standard ontologies.

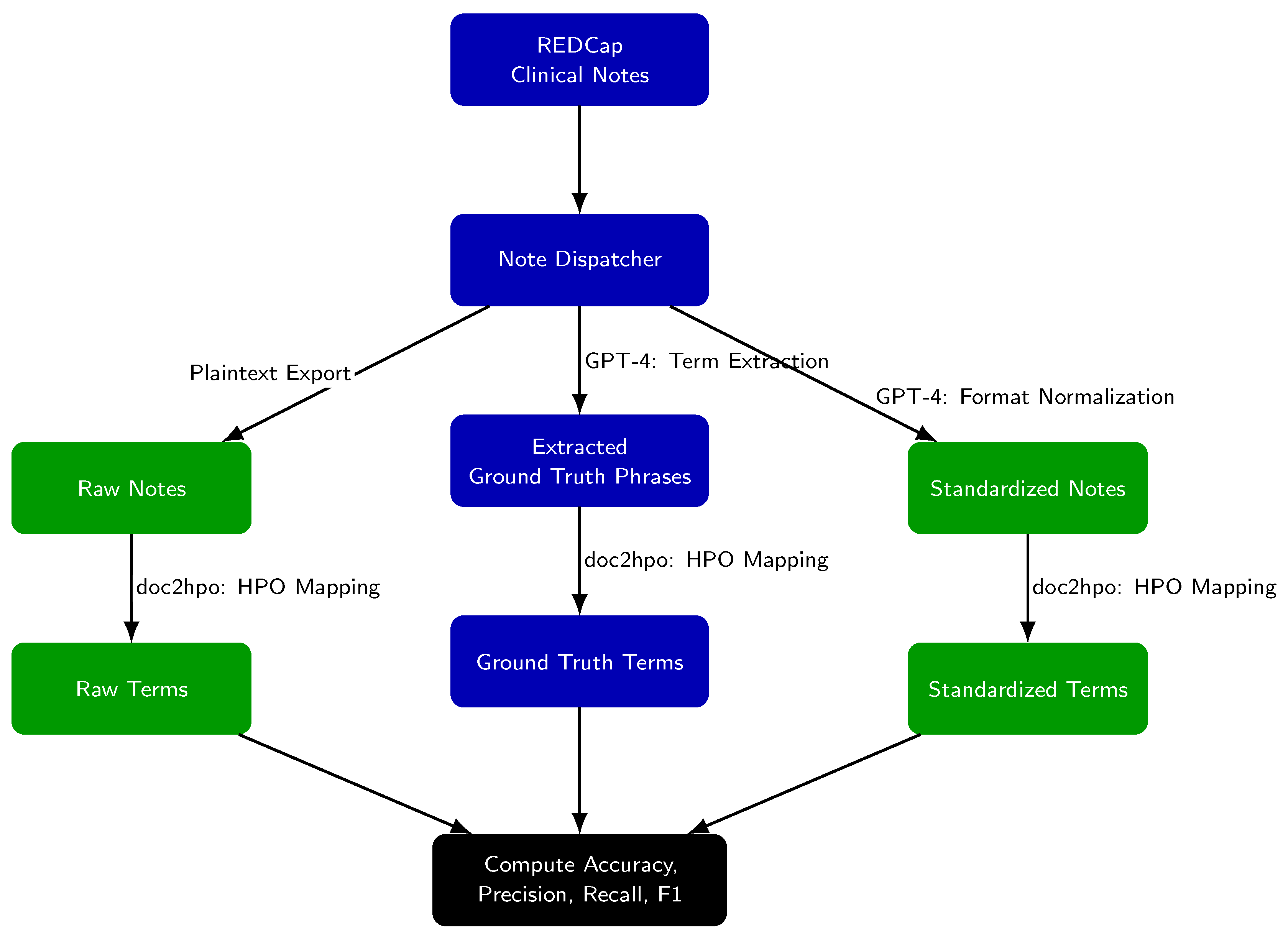

2. Methods

- Raw notes (unmodified exports from REDCap),

- Standardized notes (post-GPT-4 processing),

- Ground truth phrases (GPT-4 extracted candidate HPO terms).

- Ground truth terms: GPT-4 extracted phrases successfully matched by doc2hpo.

- Raw-note terms: doc2hpo output from raw notes.

- Standardized-note terms: doc2hpo output from standardized notes.

- True Positive (TP): Term present in both the extracted set and the ground truth set.

- False Negative (FN): Ground truth term not captured in extraction set.

- False Positive (FP): Term extracted but not part of ground truth set.

- True Negative (TN): Term present in the note but not successfully mapped to HPO by doc2hpo.

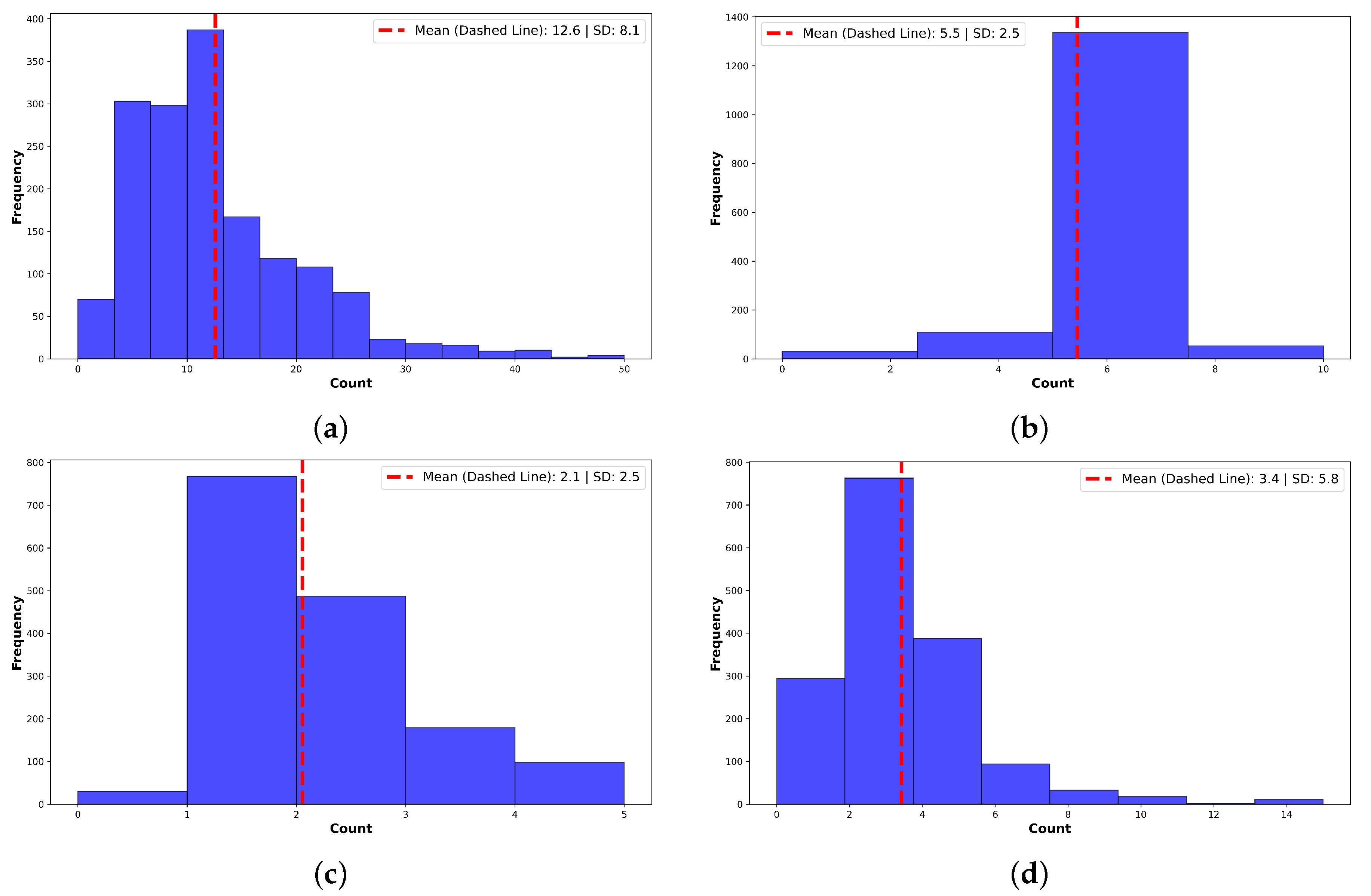

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Note Standardization Improves Structure and Readability

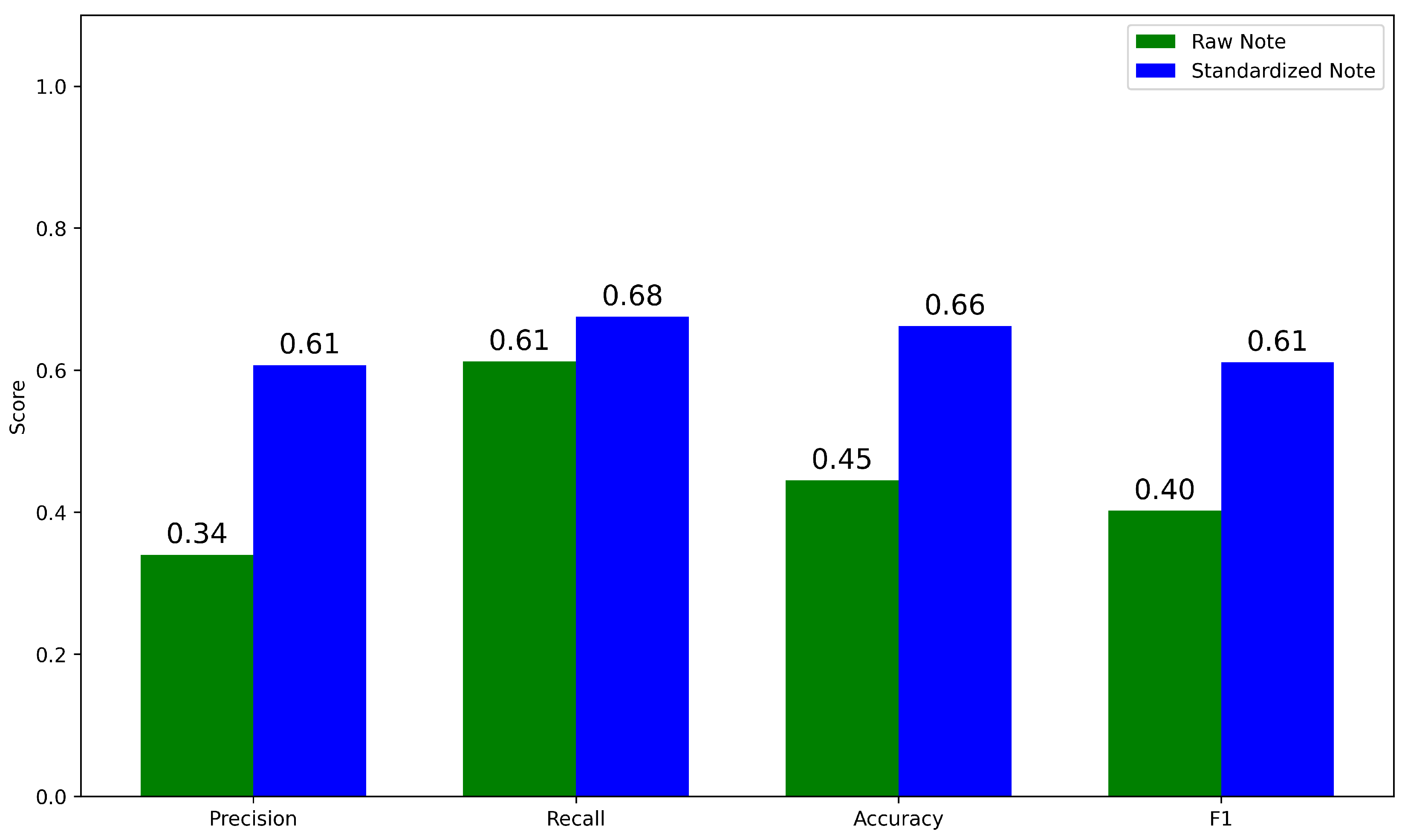

3.2. Standardization Improves HPO Term Extraction by doc2hpo

- Raw Notes → doc2hpo → Raw Terms

- Standardized Notes → doc2hpo → Standardized Terms

- GPT-4 Extracted Phrases → doc2hpo → Ground Truth Terms

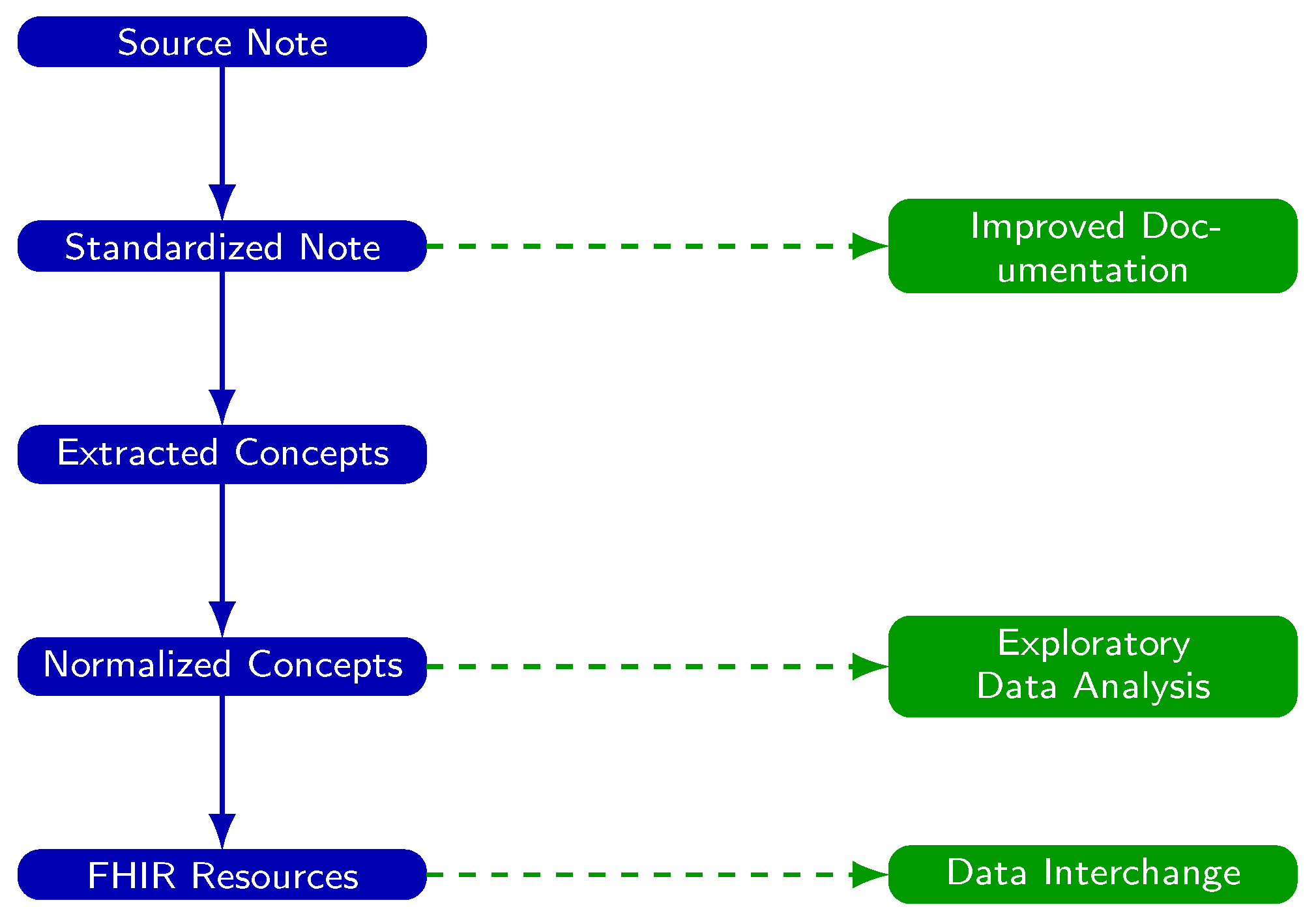

3.3. Downstream Use Cases After Note Standardization

- Standardized notes can be integrated in real time into the EHR to enhance note quality, readability, and clinical interpretability.

- Extracted terms can be passed into NLP pipelines that map these terms to ontology concepts, making clinical data computable for exploratory analysis, machine learning, population health, and quality improvement.

3.4. Addressing Systemic Challenges in EHR Documentation

3.5. Limitations

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Prompt to GPT-4 to Standardize a Physician Note

Appendix B. Note Format Used by GPT-4 for Standardized Notes

Appendix C. Example of Corrections Made by GPT-4

Appendix D. Prompt to GPT-4 to Identify Ground Truth Terms

Appendix E. Sample Neurological Examinations: Before and After Standardization

Appendix F. Abbreviations

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| ASCII | American Standard Code for Information Interchange |

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| FHIR | Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources |

| HIPAA | Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act |

| HPO | Human Phenotype Ontology |

| ICD | International Classification of Diseases |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| JSON | JavaScript Object Notation |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| LOINC | Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| REDCap | Research Electronic Data Capture |

| RxNorm | Standardized Nomenclature for Clinical Drugs |

| TP/FN/FP/TN | True Positive / False Negative / False Positive / True Negative |

References

- Menachemi, N.; Collum, T.H. Benefits and drawbacks of electronic health record systems. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 2011, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruner, A.; Kasdan, M.L. Handwriting errors: harmful, wasteful and preventable. Journal-Kentucky Medical Association 2001, 99, 189–192. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, E.A.; Dittus, R.S.; Smith, W.R.; Fitzgerald, J.F.; Langfeld, C.D. Deciphering the physician note. Journal of General Internal Medicine 1994, 9, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Vera, F.J.; Marin, Y.; Sanchez, A.; Borrachero, C.; Pujol, E. Illegible handwriting in medical records. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 2002, 95, 545–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmgren, A.J.; Hendrix, N.; Maisel, N.; Everson, J.; Bazemore, A.; Rotenstein, L.; Phillips, R.L.; Adler-Milstein, J. Electronic health record usability, satisfaction, and burnout for family physicians. JAMA Network Open 2024, 7, e2426956–e2426956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhiyaddin, R.; Elfadl, A.; Mohamed, E.; Shah, Z.; Alam, T.; Abd-Alrazaq, A.; Househ, M. Electronic health records and physician burnout: a scoping review. Informatics and Technology in Clinical Care and Public Health 2022, 481–484. [Google Scholar]

- Downing, N.L.; Bates, D.W.; Longhurst, C.A. Physician burnout in the electronic health record era: are we ignoring the real cause? Annals of Internal Medicine 2018, 169, 50–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, M.; Padua, M.; Schwenk, T.L. Electronic health records, medical practice problems, and physician distress. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 2022, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.E. How health information technology is failing to achieve its full potential. JAMA Pediatrics 2015, 169, 201–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Fernández, J.M.; Loeb, J.A.; Hier, D.B. It’s time to change our documentation philosophy: writing better neurology notes without the burnout. Frontiers in Digital Health 2022, 4, 1063141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, R.J.; Steege, L.M.B.; Moore, J.L.; Clarke, M.A.; Canfield, S.M.; Kim, M.S.; Belden, J.L. Physician information needs and electronic health records (EHRs): time to reengineer the clinic note. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 2015, 28, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budd, J. Burnout related to electronic health record use in primary care. Journal of primary care & community health 2023, 14, 21501319231166921. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo, S.S.; Plasek, J.M.; Xu, H.; Uzuner, Ö.; Cohen, T.; Yetisgen, M.; Liu, H.; Meystre, S.; Wang, Y. Large language models for biomedicine: foundations, opportunities, challenges, and best practices. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2024, ocae074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Ong, H.H.; Grabowska, M.E.; Krantz, M.S.; Su, W.C.; Dickson, A.L.; Peterson, J.F.; Feng, Q.; Roden, D.M.; Stein, C.M.; et al. Large language models facilitate the generation of electronic health record phenotyping algorithms. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2024, ocae072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munzir, S.I.; Hier, D.B.; Carrithers, M.D. High Throughput Phenotyping of Physician Notes with Large Language and Hybrid NLP Models. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2403.05920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omiye, J.A.; Gui, H.; Rezaei, S.J.; Zou, J.; Daneshjou, R. Large language models in medicine: the potentials and pitfalls. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.00087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clusmann, J.; Kolbinger, F.R.; Muti, H.S.; Carrero, Z.I.; Eckardt, J.N.; Laleh, N.G.; Löffler, C.M.L.; Schwarzkopf, S.C.; Unger, M.; Veldhuizen, G.P.; et al. The future landscape of large language models in medicine. Communications Medicine 2023, 3, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Yerebakan, H.; Shinagawa, Y.; Luo, Y. Enhancing Health Data Interoperability with Large Language Models: A FHIR Study. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.12989. [Google Scholar]

- Van Veen, D.; Van Uden, C.; Blankemeier, L.; Delbrouck, J.B.; Aali, A.; Bluethgen, C.; Pareek, A.; Polacin, M.; Reis, E.P.; Seehofnerova, A.; et al. Clinical text summarization: adapting large language models can outperform human experts. Research Square 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.; Sun, Z.; Idnay, B.; Nestor, J.G.; Soroush, A.; Elias, P.A.; Xu, Z.; Ding, Y.; Durrett, G.; Rousseau, J.F.; et al. Evaluating large language models on medical evidence summarization. NPJ digital medicine 2023, 6, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Bitterman, D.; Afshar, M.; Miller, T.A. Considerations for health care institutions training large language models on electronic health records. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.12339. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, J.; Li, L.; Sun, J.; Peng, J.; Shi, P.; Zhang, R.; Dong, Y.; Lam, K.; Lo, F.P.W.; Xiao, B.; et al. Large ai models in health informatics: Applications, challenges, and the future. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Petzold, L. Are Large Language Models Ready for Healthcare. A Comparative Study on Clinical Language Understanding. ArXiv 2023, arXiv:/2304.05368. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, J. Fewer Physicians Consider Leaving Medicine, Survey Finds. MedPage Today, 29 March 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kugic, A.; Schulz, S.; Kreuzthaler, M. Disambiguation of acronyms in clinical narratives with large language models. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2024, 31, 2040–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aronson, J.K. When I use a word... Medical slang: a taxonomy. bmj 2023, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.H.; Patel, J.P.; VI, A.H.F. Patient-centric medical notes: Identifying areas for improvement in the age of open medical records. Patient Education and Counseling 2017, 100, 1608–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, C.M.; Wilson, C.; Wang, F.; Schillinger, D. Babel babble: physicians’ use of unclarified medical jargon with patients. American Journal of Health Behavior 2007, 31, S85–S95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, M.B.; Hendrickson, M.A. Eradicating jargon-oblivion—a proposed classification system of medical jargon. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2020, 35, 1861–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, T.E.; Shao, Y.; Divita, G.; Zeng-Treitler, Q. An efficient prototype method to identify and correct misspellings in clinical text. BMC Research Notes 2019, 12, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamiel, U.; Hecht, I.; Nemet, A.; Pe’er, L.; Man, V.; Hilely, A.; Achiron, A. Frequency, comprehension and attitudes of physicians towards abbreviations in the medical record. Postgraduate Medical Journal 2018, 94, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J.S.; Gojraty, S.; Yang, W.; Linsky, A.; Airan-Javia, S.; Polomano, R.C. A randomized-controlled trial of computerized alerts to reduce unapproved medication abbreviation use. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2011, 18, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horon, K.; Hayek, K.; Montgomery, C. Prohibited abbreviations: seeking to educate, not enforce. The Canadian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy 2012, 65, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, S.; Hoi, S.; Fernandes, O.; Huh, J.; Kynicos, S.; Murphy, L.; Lowe, D. Audit on the use of dangerous abbreviations, symbols, and dose designations in paper compared to electronic medication orders: A multicenter study. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 2018, 52, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shultz, J.; Strosher, L.; Nathoo, S.N.; Manley, J. Avoiding potential medication errors associated with non-intuitive medication abbreviations. The Canadian journal of hospital pharmacy 2011, 64, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.E. Campaign to Eliminate Use of Error-Prone Abbreviations. Hospital Pharmacy 2006, 41, 809–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association, A.H.; of Health-System Pharmacists, A.S.; et al. Medication safety issue brief. Eliminating dangerous abbreviations, acronyms and symbols. Hospitals & Health Networks 2005, 79, 41–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hultman, G.M.; Marquard, J.L.; Lindemann, E.; Arsoniadis, E.; Pakhomov, S.; Melton, G.B. Challenges and opportunities to improve the clinician experience reviewing electronic progress notes. Applied Clinical Informatics 2019, 10, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, C.J.; Huff, S.M.; Suico, J.G.; Hill, G.; Leavelle, D.; Aller, R.; Forrey, A.; Mercer, K.; DeMoor, G.; Hook, J.; et al. LOINC, a universal standard for identifying laboratory observations: a 5-year update. Clinical Chemistry 2003, 49, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, J.; Joseph, E.; Brochhausen, M.; Hogan, W.R. Building a drug ontology based on RxNorm and other sources. Journal of Biomedical Semantics 2013, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, J.; Golpira, R.; Hashemi, N.; Azadmanjir, Z.; Meidani, Z.; Vahedi, A.; Bakhshandeh, H.; Fakharian, E.; Sheikhtaheri, A. Comparison of the accuracy of inpatient morbidity coding with ICD-11 and ICD-10. Health Information Management Journal 2025, 54, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; de Keizer, N.; Lau, F.; Cornet, R. Literature review of SNOMED CT use. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2014, 21, e11–e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficarra, B.J. Grammar and Medicine. Archives of Surgery 1981, 116, 251–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, F.R.; Zhou, L.; Weiner, S.G. Incidence of speech recognition errors in the emergency department. International Journal of Medical Informatics 2016, 93, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, D.; Sartipi, K. HL7 FHIR: An Agile and RESTful approach to healthcare information exchange. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 26th IEEE international symposium on computer-based medical systems.

- Vorisek, C.N.; Lehne, M.; Klopfenstein, S.A.I.; Mayer, P.J.; Bartschke, A.; Haese, T.; Thun, S. Fast healthcare interoperability resources (FHIR) for interoperability in health research: systematic review. JMIR medical informatics 2022, 10, e35724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunstein, M.L. Health Informatics on FHIR: How HL7’s New API is Transforming Healthcare; Springer, 2018.

- Benson, T.; Grieve, G. Principles of health interoperability. Springer International.

- Groza, T.; Köhler, S.; Doelken, S.; Collier, N.; Oellrich, A.; Smedley, D.; Couto, F.M.; Baynam, G.; Zankl, A.; Robinson, P.N. Automatic concept recognition using the human phenotype ontology reference and test suite corpora. Database 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Bao, R.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xiang, Y. Accurate medical named entity recognition through specialized NLP models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.08255. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.F.; Henry, S.; Wang, Y.; Shen, F.; Uzuner, O.; Rumshisky, A. The 2019 n2c2/UMass Lowell shared task on clinical concept normalization. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2020, 27, 1529–e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, M.; O’Connell, C.; Fatemi, Y.; Levy, A.; Sontag, D. Robust benchmarking for machine learning of clinical entity extraction. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning for Healthcare Conference. PMLR; 2020; pp. 928–949. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, S.; Chen, D.; He, H.; Liu, S.; Moon, S.; Peterson, K.J.; Shen, F.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wen, A.; et al. Clinical concept extraction: a methodology review. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2020, 103526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funk, C.; Baumgartner, W.; Garcia, B.; Roeder, C.; Bada, M.; Cohen, K.B.; Hunter, L.E.; Verspoor, K. Large-scale biomedical concept recognition: an evaluation of current automatic annotators and their parameters. BMC bioinformatics 2014, 15, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.G.; Howsmon, D.; Zhang, B.; Hahn, J.; McGuinness, D.; Hendler, J.; Ji, H. Entity linking for biomedical literature. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2015, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Peres Kury, F.S.; Li, Z.; Ta, C.; Wang, K.; Weng, C. Doc2Hpo: a web application for efficient and accurate HPO concept curation. Nucleic Acids Research 2019, 47, W566–W570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, D.M. Evaluation: from precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness and correlation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.16061. [Google Scholar]

- Tayefi, M.; Ngo, P.; Chomutare, T.; Dalianis, H.; Salvi, E.; Budrionis, A.; Godtliebsen, F. Challenges and opportunities beyond structured data in analysis of electronic health records. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics 2021, 13, e1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.Y.; Liu, X.C.; Nejatian, N.P.; Nasir-Moin, M.; Wang, D.; Abidin, A.; Eaton, K.; Riina, H.A.; Laufer, I.; Punjabi, P.; et al. Health system-scale language models are all-purpose prediction engines. Nature 2023, 619, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, J.; Hochman, K.A.; Guzman, B.V.; Goodman, A.; Weisstuch, J.; Testa, P. Scaling note quality assessment across an academic medical center with AI and GPT-4. NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery 2024, 5, CAT–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegler, E.L.; Adelman, R. Copy and paste: a remediable hazard of electronic health records. The American Journal of Medicine 2009, 122, 495–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, S.J.; Wang, S.; Kelly, B.; Sharma, G.; Schwartz, A. How accurate is the medical record? A comparison of the physician’s note with a concealed audio recording in unannounced standardized patient encounters. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2020, 27, 770–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Kostis, W.J.; Wilson, A.C.; Cosgrove, N.M.; Hassett, A.L.; Moreyra, A.E.; Delnevo, C.D.; Kostis, J.B. Questionable hospital chart documentation practices by physicians. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2008, 23, 1865–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakken, S. Can informatics innovation help mitigate clinician burnout? Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2019, 26, 93–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, M. Physician burnout in the electronic health record era. Annals of Internal Medicine 2019, 170, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Sarkar, N. Interventions to reduce electronic health record-related burnout: a systematic review. Applied Clinical Informatics 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Z.; Wei, Q.; Xu, H. Bert-based ranking for biomedical entity normalization. AMIA Summits on Translational Science Proceedings 2020, 2020, 269. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, J.A.; Cofrancesco, J.; Beach, M.C.; Bertram, A.; Hedian, H.F.; Mixter, S.; Yeh, H.C.; Berkenblit, G. Effect of outpatient note templates on note quality: NOTE (Notation Optimization through Template Engineering) randomized clinical trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2021, 36, 580–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savoy, A.; Frankel, R.; Weiner, M. Clinical thinking via electronic note templates: who benefits? Journal of General Internal Medicine 2021, 36, 577–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbers, T.; Kool, R.B.; Smeele, L.E.; Dirven, R.; den Besten, C.A.; Karssemakers, L.H.; Verhoeven, T.; Herruer, J.M.; van den Broek, G.B.; Takes, R.P. The impact of structured and standardized documentation on documentation quality; a multicenter, retrospective study. Journal of Medical Systems 2022, 46, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, H.B.; Hoang, A.; Becher, D.; Fontelo, P.; Liu, F.; Stephens, M.; Pangaro, L.N.; Sessums, L.L.; O’Malley, P.; Baxi, N.S.; et al. QNOTE: an instrument for measuring the quality of EHR clinical notes. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2014, 21, 910–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).