Submitted:

16 April 2025

Posted:

17 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

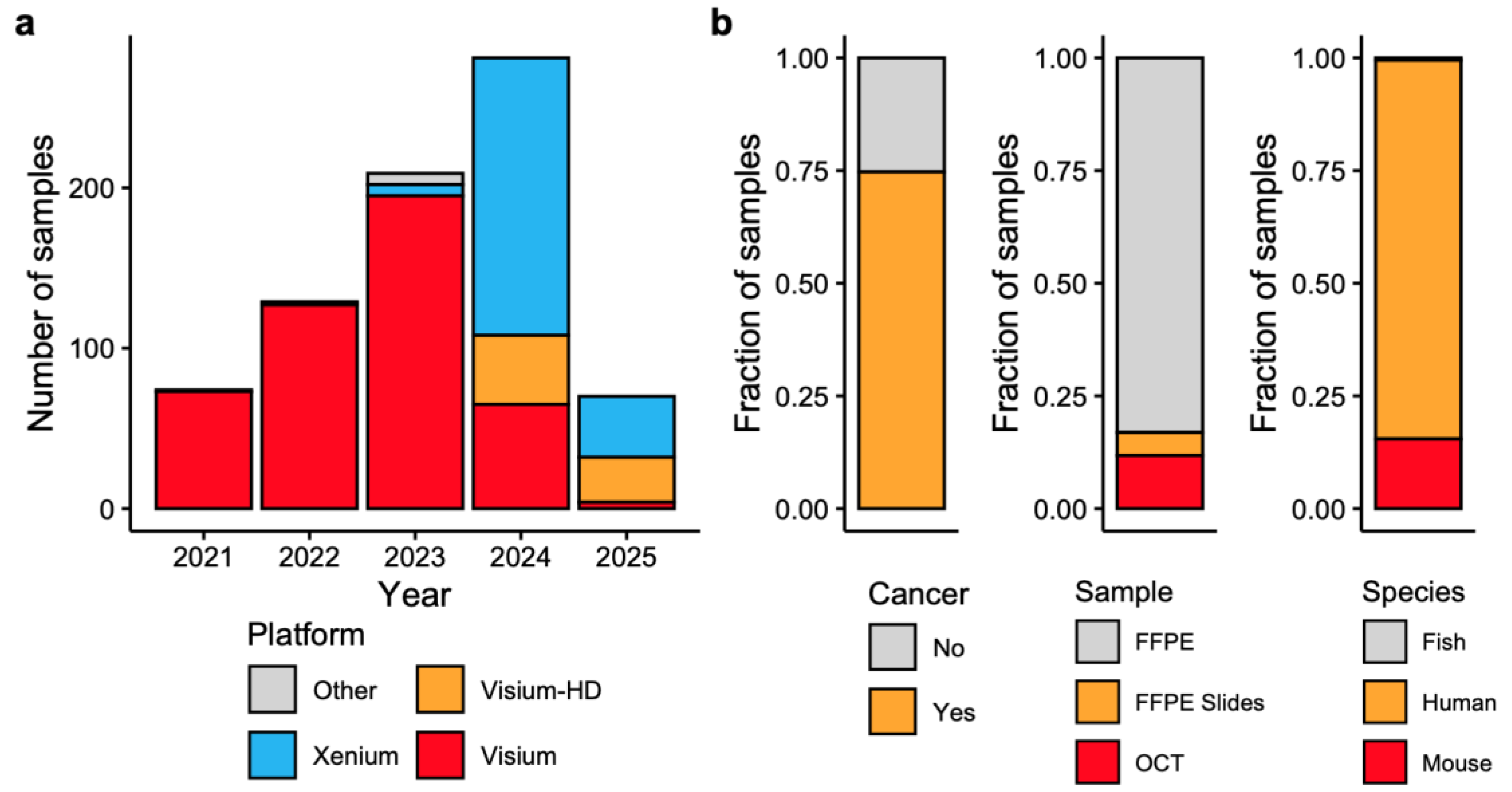

QuickStart: Five Lessons from 1,000+ Samples

- Lesson 1: Build the right team early

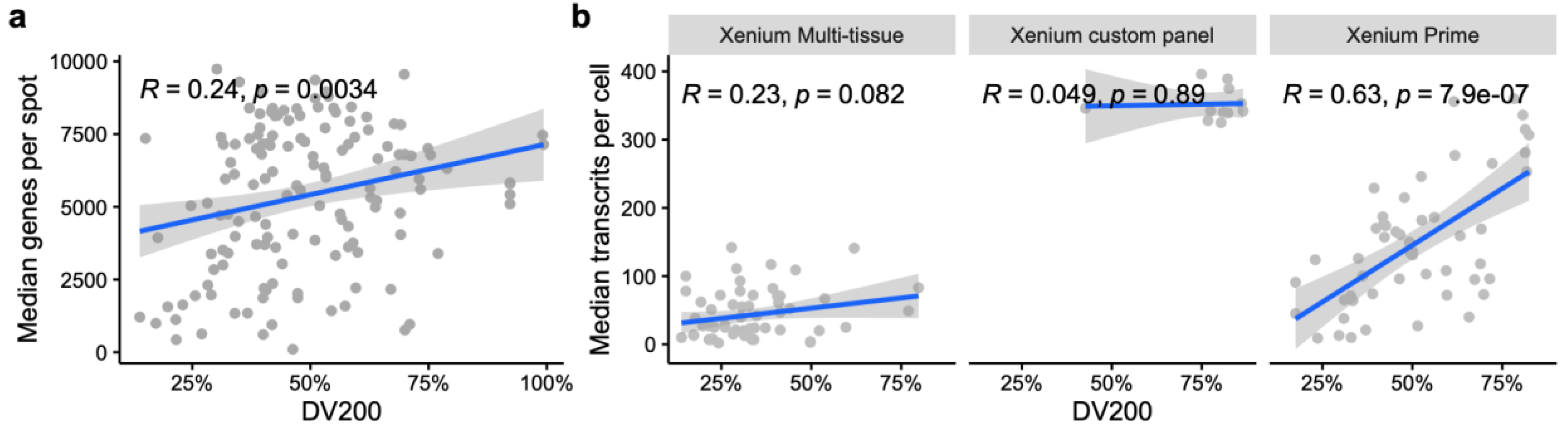

- Lesson 2: RNA quality matters, but it’s not everything

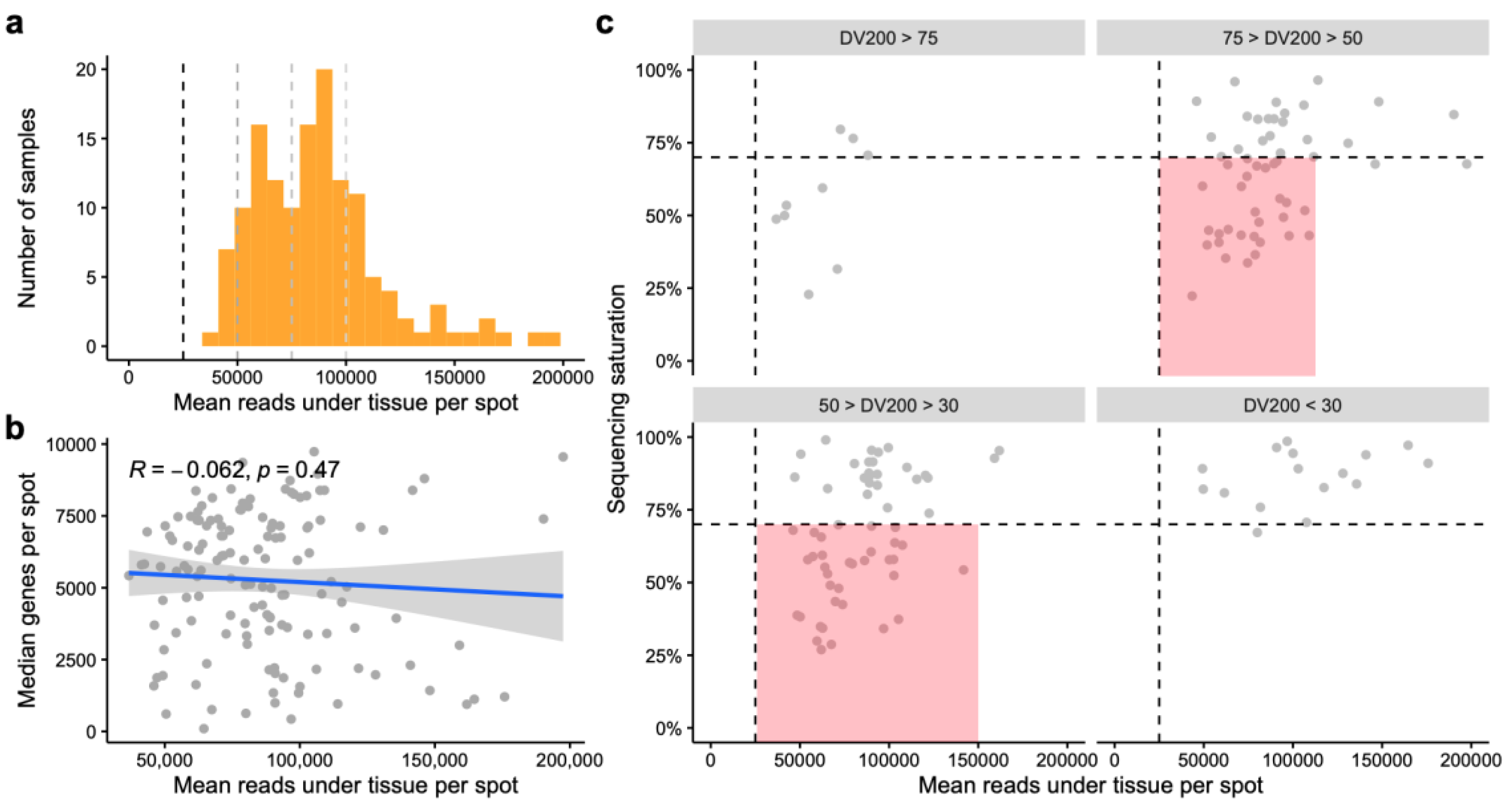

- Lesson 3: Don’t skimp on sequencing

- Lesson 4: Bigger gene panels can dilute your signal

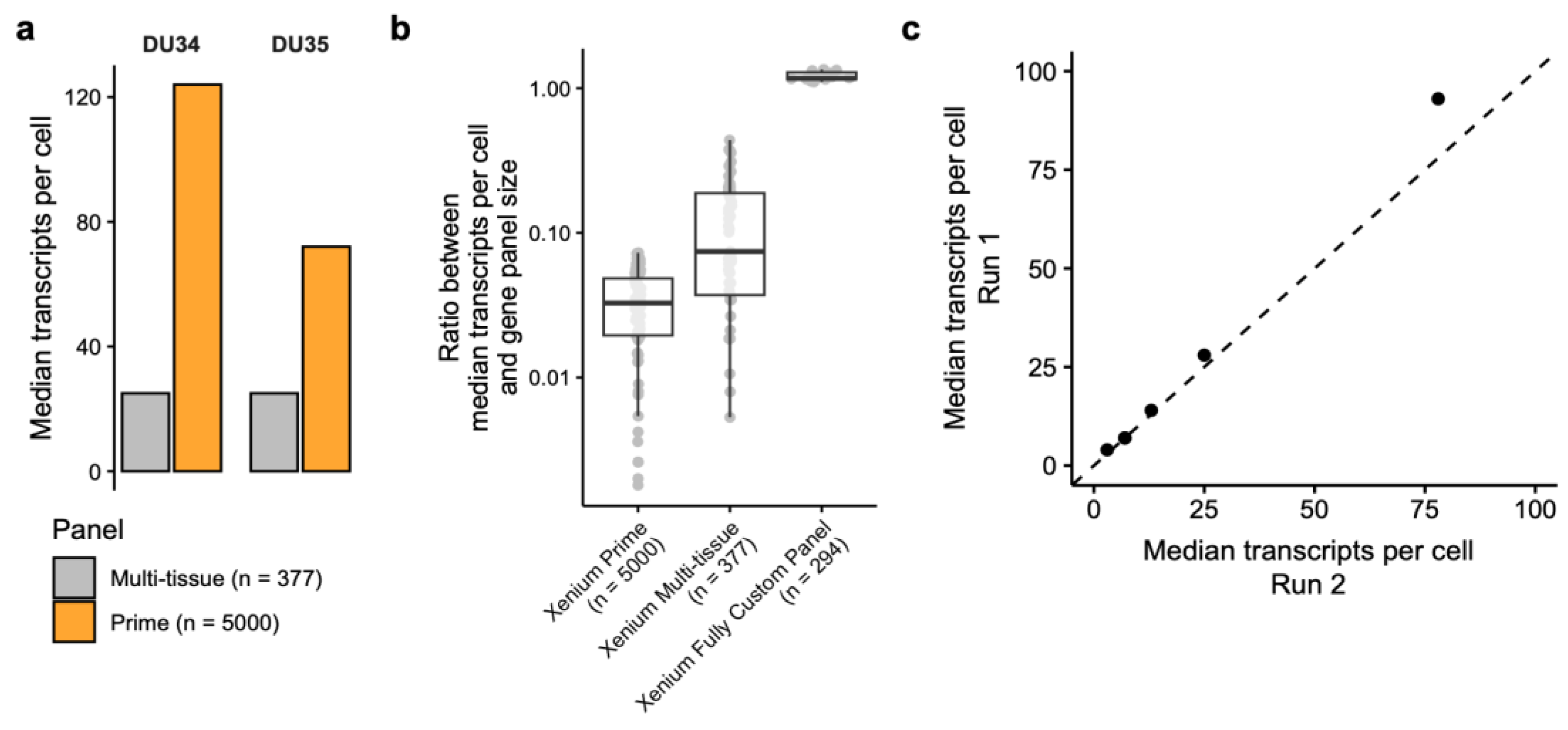

- Lesson 5: Batch effects are easier to prevent than to fix

- Step 1 - Defining the Research Question

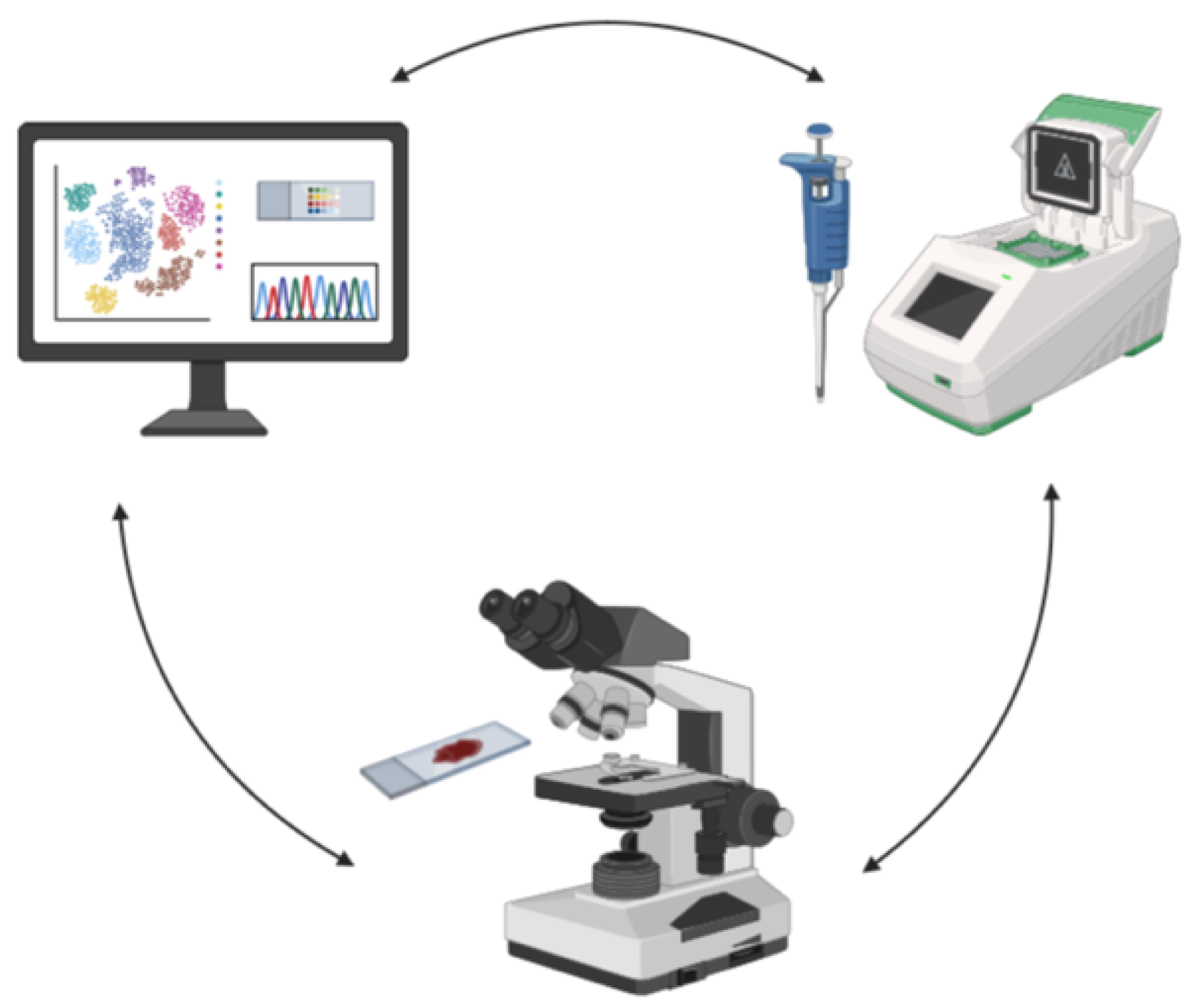

- Step 2 - Assemble the right team

- 1. Laboratory technician - Sample Preparation & Execution

- 2. Pathology & Histological Input

- 3. Bioinformatics & Data Interpretation

- Coordination is Key

- Step 3 - Experimental Design, Controls, and Statistical Power

- Step 4 – Tissue Selection, Processing, and Quality Control

- RNA

- RNA Quality Control

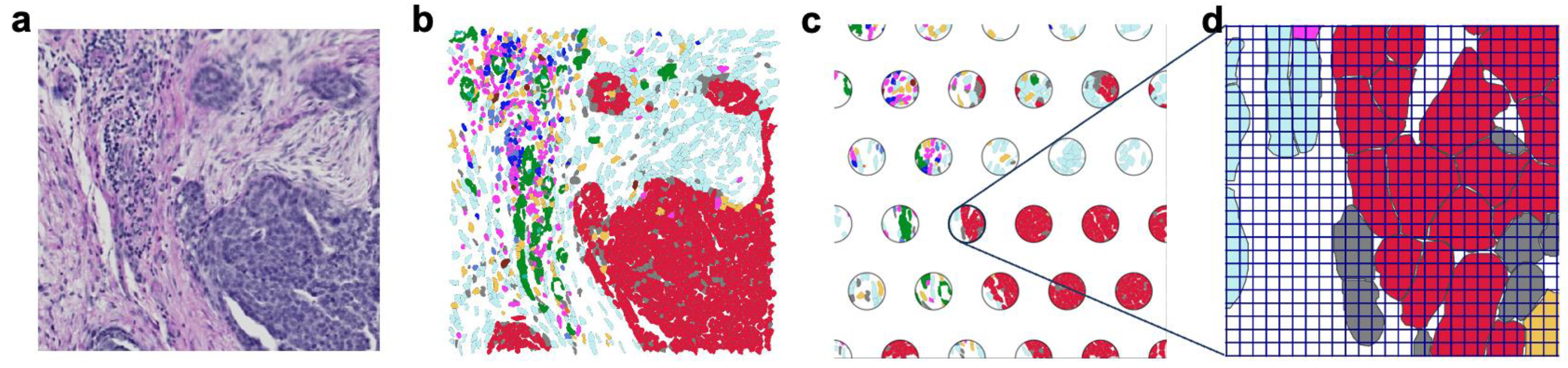

- Histological and Nuclear QC

- Step 5 - Spatial Platform Selection

- When Sample Quality Is a Limiting Factor

- Whole-Transcriptome vs. Targeted Approaches

- Whole-transcriptome platforms (e.g., Visium, Visium CytAssist, Visium-HD, Stereo-seq) offer broad, unbiased gene expression profiling. These are ideal for exploratory studies, identifying novel cell states, or capturing unanticipated spatial programs. However, they require high sequencing depth and often have lower spatial resolution unless using HD variants.

- Targeted platforms (e.g., Xenium, CosMx, MERFISH) focus on a fixed set of genes and enable high spatial resolution, often at the single-cell or subcellular level. These approaches are well suited for hypothesis-driven studies focused on specific pathways or cell populations. The main limitation is that genes outside the panel are undetectable, limiting discovery potential.

- Panel Design and Sensitivity Trade-offs

- Cross-Sample and Cross-Platform Comparability

- Cost, Scalability, and Workflow Practicality

- Whole-transcriptome platforms typically require deeper sequencing, increasing per-sample costs and limiting scalability.

- Imaging-based platforms can be more cost-effective for large-scale studies, especially when using TMAs, which allow multiple samples to be profiled on a single slide without sequencing.

- Some platforms also offer higher sample multiplexing or simplified batch processing. For example, Xenium supports multiple slides per run, and CosMx allows parallel processing of RNA and protein targets, reducing the need for separate experiments.

- Turnaround time is another consideration. Visium experiments can often be completed within a week (excluding sequencing), whereas CosMx and Xenium runs typically require longer, especially when imaging large tissue areas or running high-plex panels.

- Workflow complexity also varies. Platforms like Visium, Visium-HD, Xenium, GeoMx and CosMx offer relatively streamlined protocols that are broadly compatible with diverse tissue types. In contrast, methods such as MERFISH or seqFISH demand specialized microscopy setups, significant user training, and often require protocol optimization for each tissue type.

- Step 6 – Execution of the Experiment

- Pre-experiment Setup

- Tissue Sectioning and ROI Localization

- Handling Larger Blocks and Small ROIs

- Working with Tissue Microarrays (TMAs)

- Core size: Larger cores (1.5–2.0 mm) are useful for preserving architecture; smaller, random cores better capture tumor heterogeneity.

- Replicates and backups: Always prepare 2–3 consecutive sections in advance in case of technical failures.

- Sample Preparation and Bench Practices

- Use RNase-free surfaces and tips

- Process samples in parallel and randomized order

- Control incubation time and temperature precisely

- Use reagents from the same lot whenever possible

- Prevent contamination by gentle pipetting and workspace cleaning

- Real-time quality control should be embedded in the workflow. Monitor RNA integrity, tissue morphology, staining quality and library QC before proceeding to sequencing or imaging. These checkpoints can prevent time and resource loss on low-quality material.

- Tips for Visium CytAssist Alignment

- Step 7 – Sequencing decisions for Spatial Transcriptomics Libraries

- Step 8 – Data Processing, Normalization, and Interpretation

Future Directions: AI, Multi-Omics, and Clinical Applications

Spatial at Scale: From Feasibility to Impact

Acknowledgements

References

- Williams, C.G.; Lee, H.J.; Asatsuma, T.; Vento-Tormo, R.; Haque, A. An introduction to spatial transcriptomics for biomedical research. Genome Med. 2022, 14, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, A.; Barkley, D.; França, G.S.; Yanai, I. Exploring tissue architecture using spatial transcriptomics. Nature 2021, 596, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressan, D.; Battistoni, G.; Hannon, G.J. The dawn of spatial omics. Science 2023, 381, eabq4964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, V. Method of the Year: spatially resolved transcriptomics. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Zuo, Y.; Li, G.; Liu, W.; Pan, Y.; Fan, T.; Fu, X.; Yao, X.; Peng, Y. Advances in spatial transcriptomics and its applications in cancer research. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fomitcheva-Khartchenko, A.; Kashyap, A.; Geiger, T.; Kaigala, G.V. Space in cancer biology: its role and implications. Trends Cancer 2022, 8, 1019–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarenpää, S.; Shalev, O.; Ashkenazy, H.; Carlos, V.; Lundberg, D.S.; Weigel, D.; et al. Spatial metatranscriptomics resolves host-bacteria-fungi interactomes. Nat Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 1384–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Xiao, W.; Tian, L.; Guo, L.; Ma, G.; Ji, C.; Huang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wu, X.; Yang, T.; et al. Spatial transcriptomics uncover sucrose post-phloem transport during maize kernel development. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Guo, P.; Xia, K.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, J.; Xu, M.; Liu, N.; Yue, Z.; et al. Spatial transcriptomics reveals light-induced chlorenchyma cells involved in promoting shoot regeneration in tomato callus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2310163120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Z.V.; Hegarty, B.E.; Gruenhagen, G.W.; Lancaster, T.J.; McGrath, P.T.; Streelman, J.T. Cellular profiling of a recently-evolved social behavior in cichlid fishes. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valihrach, L.; Zucha, D.; Abaffy, P.; Kubista, M. A practical guide to spatial transcriptomics. Mol. Asp. Med. 2024, 97, 101276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Luo, S.; Shi, H.; Wang, X. Spatial omics advances for in situ RNA biology. Mol. Cell 2024, 84, 3737–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffitt, J.R.; Lundberg, E.; Heyn, H. The emerging landscape of spatial profiling technologies. Nat Rev Genet. 2022, 23, 741–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Chen, F.; Macosko, E.Z. The expanding vistas of spatial transcriptomics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 41, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moses, L.; Pachter, L. Museum of spatial transcriptomics. Nat Methods 2022, 19, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.P.; Jensen, K.B.; Wise, K.; Roach, M.J.; Dezem, F.S.; Ryan, N.K.; et al. A comparative analysis of imaging-based spatial transcriptomics platforms. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Harvey, K.; Reeves, J.; Roden, D.L.; Bartonicek, N.; Yang, J.; et al. An experimental comparison of the Digital Spatial Profiling and Visium spatial transcriptomics technologies for cancer research. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, P.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Luo, C.; Wang, S.; et al. Systematic benchmarking of high-throughput subcellular spatial transcriptomics platforms. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Huang, R.; Nelson, J.; Gao, C.; Tran, M.; Yeaton, A.; et al. Systematic benchmarking of imaging spatial transcriptomics platforms in FFPE tissues. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Fu, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, Z.; Jia, S.; Lu, S.; Ren, W.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; et al. Systematic comparison of sequencing-based spatial transcriptomic methods. Nat. Methods 2024, 21, 1743–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademacher, A.; Huseynov, A.; Bortolomeazzi, M.; Wille, S.J.; Schumacher, S.; Sant, P.; et al. Comparison of spatial transcriptomics technologies using tumor cryosections. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervilla, S.; Grases, D.; Perez, E.; Real, F.X.; Musulen, E.; Esteller, M.; et al. Comparison of spatial transcriptomics technologies across six cancer types. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.R.M.; Wang, C.; Law, C.W.; Amann-Zalcenstein, D.; Anttila, C.J.A.; Ling, L.; Hickey, P.F.; Sargeant, C.J.; Chen, Y.; Ioannidis, L.J.; et al. Benchmarking spatial transcriptomics technologies with the multi-sample SpatialBenchVisium dataset. Genome Biol. 2025, 26, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, E.; Sibai, M.; Andrada, E.; Grases, D.; Reig, O.; Escobosa, M.; et al. Spatial biomarkers of response to neoadjuvant therapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer: the DUTRENEO trial. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnol, D.; Schapiro, D.; Bodenmiller, B.; Saez-Rodriguez, J.; Stegle, O. Modeling Cell-Cell Interactions from Spatial Molecular Data with Spatial Variance Component Analysis. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 202–211e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, D.; Tan, X.; Balderson, B.; Xu, J.; Grice, L.F.; Yoon, S.; Willis, E.F.; Tran, M.; Lam, P.Y.; Raghubar, A.; et al. Robust mapping of spatiotemporal trajectories and cell–cell interactions in healthy and diseased tissues. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri-Borgogno, S.; Zhu, Y.; Sheng, J.; Burks, J.K.; Gomez, J.A.; Wong, K.K.; Wong, S.T.; Mok, S.C. Spatial Transcriptomics Depict Ligand–Receptor Cross-talk Heterogeneity at the Tumor-Stroma Interface in Long-Term Ovarian Cancer Survivors. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 1503–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Porta-Pardo, E.; Tokheim, C.; Bailey, M.H.; Yaron, T.M.; Stathias, V.; Geffen, Y.; Imbach, K.J.; Cao, S.; Anand, S.; et al. Pan-cancer proteogenomics connects oncogenic drivers to functional states. Cell 2023, 186, 3921–3944.e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibai, M.; Cervilla, S.; Grases, D.; Musulen, E.; Lazcano, R.; Mo, C.-K.; Davalos, V.; Fortian, A.; Bernat, A.; Romeo, M.; et al. The spatial landscape of cancer hallmarks reveals patterns of tumor ecological dynamics and drug sensitivity. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-R.; Wang, S.; Coy, S.; Chen, Y.-A.; Yapp, C.; Tyler, M.; Nariya, M.K.; Heiser, C.N.; Lau, K.S.; Santagata, S.; et al. Multiplexed 3D atlas of state transitions and immune interaction in colorectal cancer. Cell 2023, 186, 363–381.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bost, P.; Schulz, D.; Engler, S.; Wasserfall, C.; Bodenmiller, B. Optimizing multiplexed imaging experimental design through tissue spatial segregation estimation. Nat. Methods 2022, 20, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, E.A.G.; Schapiro, D.; Dumitrascu, B.; Vickovic, S.; Regev, A. In silico tissue generation and power analysis for spatial omics. Nat. Methods 2023, 20, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, L.; Maitra, A.; Yuan, Y.; Lau, K.; Kaur, H.; Li, L.; et al. PoweREST: Statistical Power Estimation for Spatial Transcriptomics Experiments to Detect Differentially Expressed Genes Between Two Conditions. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Jeon, H.; Chang, W.; Jeon, Y.; Li, Z.; Ma, Q.; et al. SpaDesign: A statistical framework to improve the design of sequencing-based spatial transcriptomics experiments. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsunsky, I.; Millard, N.; Fan, J.; Slowikowski, K.; Zhang, F.; Wei, K.; Baglaenko, Y.; Brenner, M.; Loh, P.-R.; Raychaudhuri, S. Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with Harmony. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.; Stuart, T.; Kowalski, M.H.; Choudhary, S.; Hoffman, P.; Hartman, A.; Srivastava, A.; Molla, G.; Madad, S.; Fernandez-Granda, C.; et al. Dictionary learning for integrative, multimodal and scalable single-cell analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 42, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, J.D.; Kozareva, V.; Ferreira, A.; Vanderburg, C.; Martin, C.; Macosko, E.Z. Single-Cell Multi-omic Integration Compares and Contrasts Features of Brain Cell Identity. Cell 2019, 177, 1873–1887.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.A.; Thomas, E.; Sozanska, A.M.; Pescia, C.; Royston, D.J. Spatial transcriptomic approaches for characterising the bone marrow landscape: pitfalls and potential. Leukemia 2024, 39, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, R.K.; Hawkins, E.D.; Bowden, R.; Rogers, K.L. Towards deciphering the bone marrow microenvironment with spatial multi-omics. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 167, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.J.; Wang, Y.; Buzdin, A.; Li, X. A practical guide for choosing an optimal spatial transcriptomics technology from seven major commercially available options. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dries, R.; Chen, J.; del Rossi, N.; Khan, M.M.; Sistig, A.; Yuan, G.-C. Advances in spatial transcriptomic data analysis. Genome Res. 2021, 31, 1706–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zormpas, E.; Queen, R.; Comber, A.; Cockell, S.J. Mapping the transcriptome: Realizing the full potential of spatial data analysis. Cell 2023, 186, 5677–5689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozenblatt-Rosen, O.; Regev, A.; Oberdoerffer, P.; Nawy, T.; Hupalowska, A.; Rood, J.E.; Ashenberg, O.; Cerami, E.; Coffey, R.J.; Demir, E.; et al. The Human Tumor Atlas Network: Charting Tumor Transitions across Space and Time at Single-Cell Resolution. Cell 2020, 181, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.C. The human body at cellular resolution: the NIH Human Biomolecular Atlas Program. Nature 2019, 574, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, T.; Butler, A.; Hoffman, P.; Hafemeister, C.; Papalexi, E.; Mauck WM3rd et, a.l. Comprehensive Integration of Single-Cell Data. Cell 2019, 177, 1888–1902e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cable, D.M.; Murray, E.; Zou, L.S.; Goeva, A.; Macosko, E.Z.; Chen, F.; Irizarry, R.A. Robust decomposition of cell type mixtures in spatial transcriptomics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 40, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleshchevnikov, V.; Shmatko, A.; Dann, E.; Aivazidis, A.; King, H.W.; Li, T.; Elmentaite, R.; Lomakin, A.; Kedlian, V.; Gayoso, A.; et al. Cell2location maps fine-grained cell types in spatial transcriptomics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Torkel, M.; Cao, Y.; Yang, J.Y.H. Multi-task benchmarking of spatially resolved gene expression simulation models. Genome Biol. 2025, 26, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charitakis, N.; Salim, A.; Piers, A.T.; Watt, K.I.; Porrello, E.R.; Elliott, D.A.; Ramialison, M. Disparities in spatially variable gene calling highlight the need for benchmarking spatial transcriptomics methods. Genome Biol. 2023, 24, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ran, Q.; Tang, J.; Chen, Z.; Huang, S.; Shi, X.; Xi, R. Benchmarking algorithms for spatially variable gene identification in spatial transcriptomics. Bioinformatics 2025. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Zhao, F.; Lin, S.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, J.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Zhao, Y. Benchmarking spatial clustering methods with spatially resolved transcriptomics data. Nat. Methods 2024, 21, 712–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Kim, H.J.; Yang, P. Evaluating spatially variable gene detection methods for spatial transcriptomics data. Genome Biol. 2024, 25, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynoso, S.; Schiebout, C.; Krishna, R.; Zhang, F. STEAM: Spatial Transcriptomics Evaluation Algorithm and Metric for clustering performance. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, W.; Luo, T.; Yu, Z.; Jiang, M.; Wen, J.; Gupta, G.P.; Giusti, P.; Zhu, H.; Yang, Y.; et al. A comprehensive comparison on cell-type composition inference for spatial transcriptomics data. Briefings Bioinform. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Jin, X.; Smyth, G.K.; Chen, Y. Benchmarking cell type annotation methods for 10x Xenium spatial transcriptomics data. BMC Bioinform. 2025, 26, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, C.-K.; Liu, J.; Chen, S.; Storrs, E.; da Costa, A.L.N.T.; Houston, A.; Wendl, M.C.; Jayasinghe, R.G.; Iglesia, M.D.; Ma, C.; et al. Tumour evolution and microenvironment interactions in 2D and 3D space. Nature 2024, 634, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouwman, B.A.; Crosetto, N.; Bienko, M. The era of 3D and spatial genomics. Trends Genet. 2022, 38, 1062–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, M.; León-Periñán, D.; Splendiani, E.; Strenger, L.; Licha, J.R.; Pentimalli, T.M.; Schallenberg, S.; Alles, J.; Tagliaferro, S.S.; Boltengagen, A.; et al. Open-ST: High-resolution spatial transcriptomics in 3D. Cell 2024, 187, 3953–3972.e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Fu, J.; Lu, Z.; Tu, J. Deep learning in integrating spatial transcriptomics with other modalities. Briefings Bioinform. 2024, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cui, H.; Zhang, A.; Xie, R.; Goodarzi, H.; Wang, B. ScGPT-spatial: Continual pretraining of single-cell foundation model for spatial transcriptomics. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; He, Y.; Coelho, P.P.; Bucci, M.; Nazir, A.; Chen, B.; et al. SpatialAgent: An Autonomous AI Agent for Spatial Biology. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Larsson, L.; Swarbrick, A.; Lundeberg, J. Spatial landscapes of cancers: insights and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 21, 660–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1. |

| Platform (Type) | Resolution & Panel Type | Sample Types | RNA Quality | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visium (FF, sequencing) | ~55 µm; Whole transcriptome | Human, mouse, all species (polyA+) | RIN ≥ 7 (≥ 4 w/ CytAssist) | Broad discovery in fresh tissue |

| Visium FFPE (sequencing) | ~55 µm; Whole transcriptome | Human, mouse FFPE | DV200 ≥ 50% (≥ 30% w/ CytAssist) | Archived samples; full profiling |

| Visium HD (sequencing) | ~2 µm; Whole transcriptome | Human, mouse FFPE or OCT | RIN ≥ 4; DV200 ≥ 30% | High-res + whole transcriptome |

| Xenium (imaging) | Subcellular; Targeted (up to 5000 genes; customizable) | Human, mouse FFPE or fresh-frozen; non-model (custom) | DV200 ≥ 10% | Cell typing; high-res profiling; cross-species (custom panels) |

| CosMx (imaging) | Subcellular; Targeted (up to 6000 genes) | Human, mouse FFPE or fresh-frozen | DV200 ≥ 10% | Multiplexed profiling; spatial cell state mapping |

| MERFISH / seqFISH (imaging) | Subcellular; Highly multiplexed (customizable) | Fresh-frozen; FFPE (with optimization) | Protocol-dependent | Deep profiling in microscopy-capable labs |

| Stereo-seq (sequencing) | 500 nm; Whole transcriptome (species-specific probes) | Human, mouse, non-model (custom probes) | RIN ≥ 7 recommended | Nanoscale mapping; large area profiling |

| Non-model species | Varies by platform & probe design | Visium (polyA+), Xenium, Stereo-seq | Variable | Cross-species studies (requires custom panels or transcriptomes) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).