1. Introduction

Detection, measurement, and treatment of high blood pressure (BP) or as a ’silent killer’, the leading risk factor for death and disability globally plays an essential role in the prevention and control of cardiovascular diseases (CV) [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. In clinical practice, measurements of systolic and diastolic BP are performed with the conventional brachial cuff sphygmomanometer [

9] to represent the pressure load in the large conduit arteries that connect to the peripheral vascular beds and organs. However, this method may have variable accuracy [

10] and due to anatomical proximity, pulsatile stress on organs such as the heart, brain, and kidney is determined more closely by central aortic pulse pressure than by the peripheral pulse pressure [

11]. There is increasing evidence that central, more than peripheral, BP is associated with target organ damage and potentially CV risk [

12,

13]. Arterial stiffness and the mechanics of arterial pulse wave propagation, reflection and pulse pressure [

14,

15] are key parts of the complex and not only mechanical but also neurohumoral [

8,

16] vascular pressure system. Various technological and computational technologies are increasingly being introduced into the field of cardiovascular disease management [

17,

18,

19]. Hence, the indirect measurement of brachial arterial BP is first and most simple step of describing cardiovascular risk, but the addition of information derived from the peripheral arterial pressure curves could result in improved assessment of CV function in relation to treatment and management not only values of high BP but arterial stiffness and vascular dysfunction. One approach involves calculating pulse wave velocity (PWV) based on pulse transit time (PTT) using photoplethysmography (PPG) from finger or toe with simultaneous electrocardiography (ECG), as increasing arterial stiffness and BP level decreases PTT values and increases the PWV [

3,

20,

21,

22]. Another option is to measure peripheral arterial pulsatile volume curves with EBI to obtain continuous data with diagnostic and prognostic significance [

23,

24,

25].

The present study aimed to achieve non-invasive monitoring of central aortic BP using EBI sensing. Electronic circuitry with an embedded data acquisition and signal processing approach is described. The appropriate placement of electrodes is proposed and the results of modeling concerning the best sensitivity and stability of the measurement procedures are discussed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection and Characteristics of Patients

In this prospective single-center study, we enrolled 66 consecutive patients aged 45-75 years, of whom 44 were applicable for further analysis. All patients were referred for a scheduled coronary angiography evaluation at East-Tallinn Central Hospital between years 2020-2021.

All enrolled patients were hemodynamically stable and in sinus rhythm before the procedure, presented palpable pulses in both radial arteries and had a contralateral variance of non-invasive brachial BP measurements of less than 20 mmHg. This study was approved by the Estonian Research Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Health Development and the study was carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after a complete explanation of the protocol and possible risks.

Exclusion criteria comprised an ongoing acute coronary syndrome, previous myocardial infarction, previous coronary revascularization (percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting, PCI/CABG), persistent atrial fibrillation (AF), significant and/or corrected valvular disease, cardiomyopathy with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <30%, pericardial effusion, renal insufficiency with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <30 mL/min/1,73m2, other significant and / or life-shortening vascular diseases (vasculitis, aortic disease including endovascular thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR), or chemotherapy).

Hypertension was defined as >140 mmHg for systolic and/or >90 mmHg for diastolic BP in repeated measurements or permanent treatment with antihypertensive drugs. Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting blood glucose concentration >7 mmol L−1 or antihyperglycemic drug treatment. Dyslipidaemia was defined as LDL cholesterol >3mmol L−1 or antidyslipidemic drug treatment. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing a patient’s weight at current hospitalization in kilograms by their height in meters squared. Vascular disease was defined by the previous diagnosis of lower extremity arterial disease, aortic aneurysm, or atherosclerosis, and a history of ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke.

2.2. Catheterization and Measurement of the Invasive Hemodynamic Data and EBI

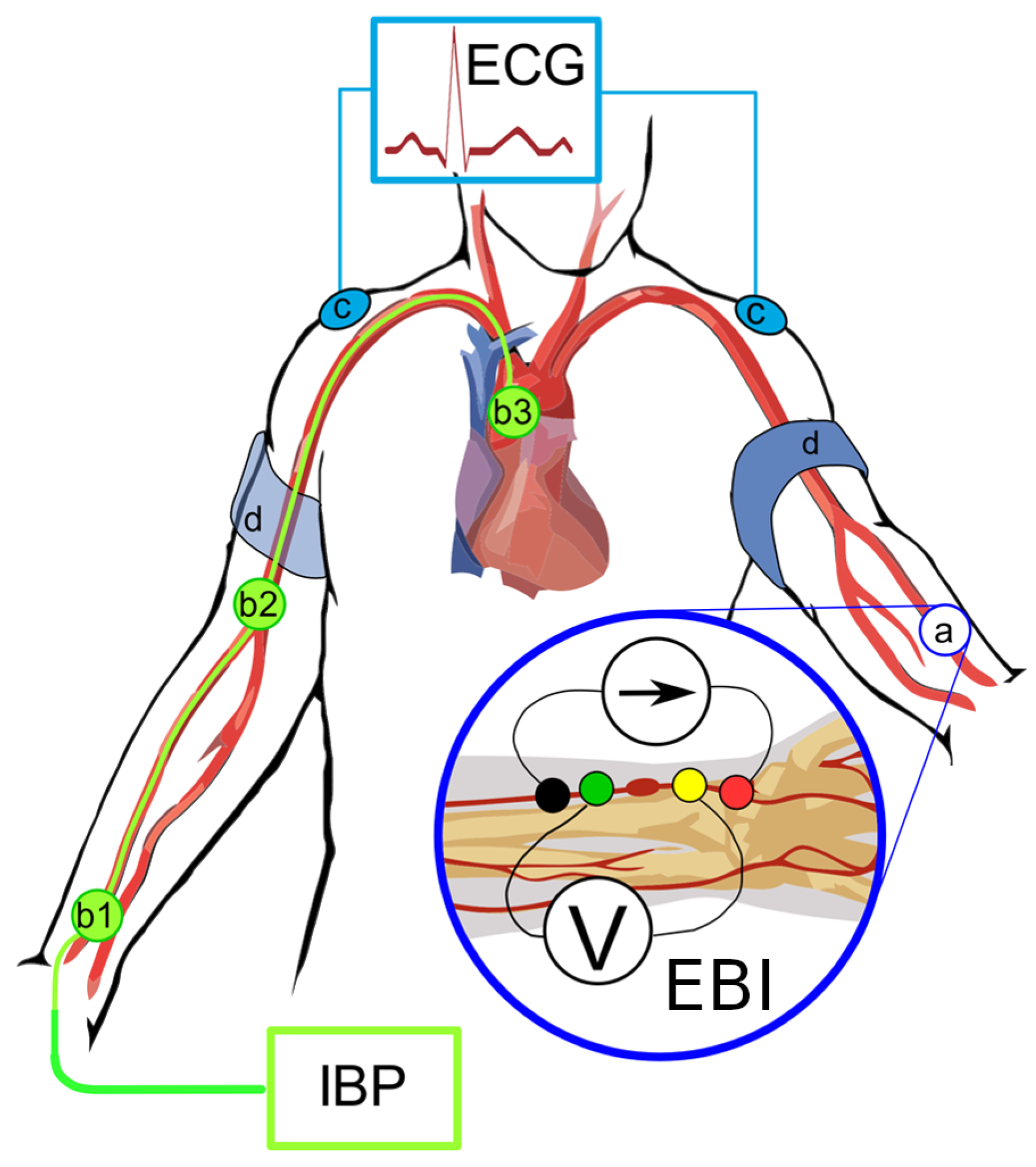

Noninvasive brachial BP measurements were performed on the cardiology ward upon arrival, selective coronary angiography with invasive blood pressure and bioimpedance measurements was performed on the same day or the next day as scheduled. Electrodes placing and measuring points in cath lab are shown in

Figure 1.

Hemodynamic measurements were conducted while the patient was in a supine position. For premedication, midazolam 3.5 mg p.o. was administered in the ward. In the Cathlab, electrodes for electrical bioimpedance (EBI) were placed to the left radial palpable pulse longitudinally (

Figure 1), and three ECG electrodes were placed on shoulders and left leg. The pressure was calibrated to normal atmospheric pressure prior to inserting the catheters. The right radial artery was cannulated, and coronary angiograms performed as standard procedure. BP measurements were performed via cannula of radial artery and the central BP was obtained via 6F Pigtail catheter positioned above aortic annulus.

All direct invasive BP measurements were achieved via saline (NaCl 0.9%) flushed line (ACIST CVI AngioTouch Kit) which was connected to ACIST CVi™ Contrast Delivery System (Standard) and were registered with the PHILIPS Xper PM5 hemodynamic system. Measurements of EBI were carried out simultaneously for every invasive measurement of BP (i.e., left radial EBI-right radial BP; left radial EBI – ascending aorta (patient nr.3 shown in

Figure 3). All registered curves (EBI, ECG, BP) were recorded with MFLI Lock-in Amplifier of Zurich Instruments, Zürich, Switzerland and saved digitally.

Coronary artery anatomy was assessed visually by performing physician fluoroscopic images during the standard procedure performed with the Allura Xper FD20 Clarity angiograph. Direct coronary angiography was performed via 6 F diagnostic catheters with Visipaque 320 mg Iodine mL−1. The narrowing of the coronary arteries were categorized as follows:

0 - Normal coronaries

1 - Minimal (≤25)% decrease in vessel diameter

2 - Moderate (26–50)% decrease in vessel diameter

3 - Medium (51–75)% decrease in vessel diameter

4 - Severe (76–90)% decrease in vessel diameter

5 - Preocclusion (91–99)%

6 - Occlusion (100)%

The patient’s numeric information was stored in the Red Cap database.

2.3. Data Analysis

The following risk factor groups were formed based on patient’ baseline clinical charcateristics: body mass index (BMI) greater than 35, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia without medical treatment, current or previous smoking, arterial vascular disease in locations other than the coronary arteries. Based on coronary lesions, the groups were formed as follows (see

Table 1):

Normal coronaries,

Minimal/Moderate (≤50)% decrease in vessel diameter,

Medium (51–75)% decrease in vessel diameter,

Significant (51–100)% decrease in vessel diameter.

2.4. Signals Preprocessing

The acquired data was smoothed with the Savitzky-Golay filter (with window duration 0.1

and polynomial order of 3). Secondly, the data were resampled at a new sample rate equal to 150 sample s

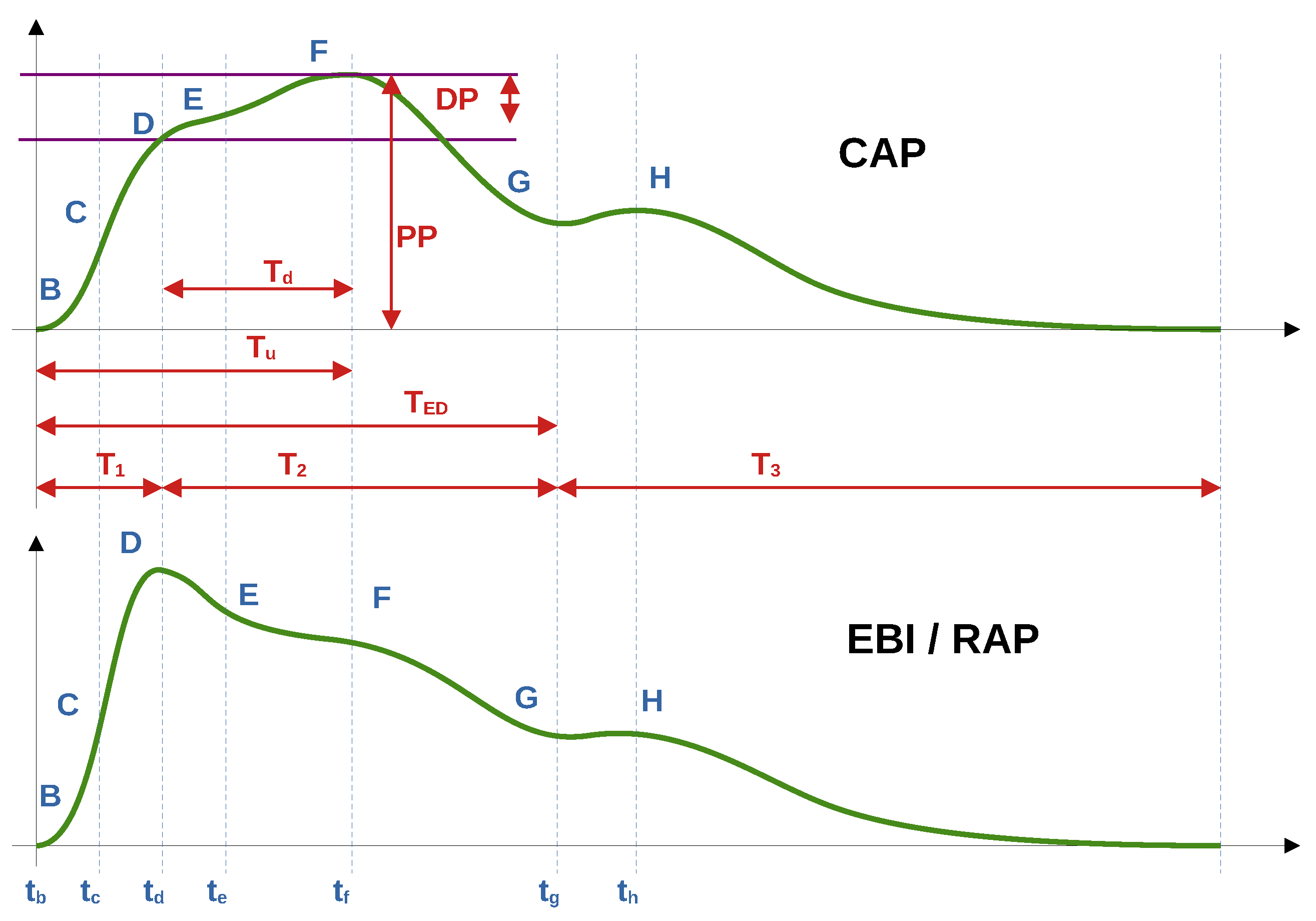

−1. In this study, instead of subtracting the mean value (high-pass filter), baseline compensation (subtraction) was used to extract the cardiac component. By the baseline of both the cardiac impedance signal and the pulse wave of blood pressure, we mean the curve that passes the minima or base of the waveforms of the signals (point B in

Figure 2). These minima were related to the end of the diastolic and beginning of the systolic processes. For this task, the Hankel matrix-based signal decomposer was used [

26].

2.5. Fiducial Points Overview

In the current work, we used alphabetical sequence of Latin letters from

B to

H, which corresponds to fiducial points of the EBI/RAP and CAP waveforms. We started from

B as

base point, corresponding to a baseline of the curve. In

Figure 2 are shown illustrative typical waveforms of the EBI and CAP periods with fiducial points, time, and amplitude intervals of our interest.

Several points on the CAP and EBI/RAP curves were identified, but only five (B, C, D, F, G) met the criteria for acceptable accuracy across all patients. Consequently, only these points were included for further analysis in this study.

The estimation of fiducial points varies between EBI/RAP waveforms and the CAP waveform. Detailed procedures for each are provided in the subsections that follow.

2.5.1. EBI/RAP Fiducial Points Estimation

The following text describes the algorithms used to identify points on the EBI and RAP signal waveforms. Although the text refers specifically to impedance signals, the same principles apply to the RAP signals and their corresponding points.

-

B point:

In cardiac impedance waveform analysis, the B point marks the beginning of the peripheral impedance curve initiated by cardiac systolic ejection. The B point detection algorithm uses a straightforward approach by identifying the first point of the signal. This initial point represents the onset of the arterial systolic curve before the rapid upstroke phase of the impedance curve. Unlike more complex feature detection methods, B point identification is based on temporal positioning rather than derivative analysis or peak detection.

-

C point:

The C point detection algorithm identifies the maximum slope in the cardiac impedance waveform, representing the rapid ventricular ejection phase. This critical point is mathematically determined by finding the maximum value of the first derivative using equation . The C point occurs as a result of ventricular systole, usually appearing between the B point (cycle onset) and the D point (peak impedance) and serves as a clinically significant marker for the assessment of contractility.

-

D point:

The D point detection algorithm identifies the peak amplitude in the cardiac EBI waveform, representing the maximum blood flow during ventricular ejection. This critical cardiac feature is computationally determined by finding the global maximum value within the signal.

-

F point:

The F point detection algorithm identifies a critical inflection point in the descending phase of the cardiac impedance waveform, marking the beginning of reduced ejection velocity after peak systolic function. This point is computationally determined by analyzing the third derivative of the impedance signal, specifically at the first transition from positive to negative slope after point D, which represents the equation . Point F serves as a significant marker for the onset of the cardiac relaxation phase, located between the peak ejection (point D) and the beginning of diastole.

-

G point:

The G point detection algorithm identifies the onset of the dicrotic notch in the cardiac impedance waveform, marking the beginning of isovolumic relaxation. This inflection point is determined by analyzing the third derivative of the impedance signal, specifically finding the most significant negative excursion after the F point according to where and is a limiting factor. The G point serves as a critical marker for the onset of the ventricular relaxation phase, positioned during the early descending limb of the impedance curve after peak ejection.

2.5.2. CAP Fiducial Points Estimation

The upcoming text explains the techniques applied to detect the corresponding points on the CAP signal waveforms.

-

B point:

Estimates the location of point B in the CAP waveform. Point B represents the onset of the systolic upstroke in the CAP signal, corresponding to the opening of the aortic valve and the beginning of ventricular ejection. This implementation simply identifies the first point in the signal as point B, which serves as a reference point for subsequent cardiac cycle analysis.

-

C point:

Estimates the C point in the CAP waveform, which represents the maximum rate of pressure increase during systole. The C point is identified as the maximum of the first derivative of the pressure signal, corresponding to the steepest ascending slope of the pressure curve. Physiologically, this point reflects the rapid ejection phase and provides information about ventricular-arterial coupling. The time of occurrence and the amplitude of the C point are important markers for assessing left ventricular contractility and arterial compliance.

-

D point:

Estimates the D point in the Central Aortic Pressure (CAP) waveform, which represents the completion of the deceleration of the ventricular ejection. The method analyzes the third derivative of pressure to identify the first positive segment after point C, locating D in the first quarter of this segment. Mathematically, the location of the D point (time instance) is defined as: in the interval . Where is the time at point C, and is the time at point F. This approach captures the maximum rate of change in pressure acceleration during late ventricular ejection, with the search window limited between points C and F to ensure physiological relevance.

-

F point:

Estimates the F point in the CAP waveform. The point F represents the maximum systolic pressure in the CAP signal, occurring during the ventricular ejection phase. This method identifies F by locating the maximum amplitude value in the CAP signal .

-

G point:

Estimates the G point in the CAP waveform, which represents the onset of left ventricular ejection. The algorithm identifies G by locating the minimum of the first derivative and then finding the beginning of the first negative segment in the third derivative within a defined interval. This interval spans from the minimum of the first derivative to halfway between this minimum and the end of the signal, providing a focused search region for detecting inflection changes. This approach exploits the inflection characteristics in which the third derivative becomes negative, indicating the acceleration change at the onset of the systolic ejection phase in the CAP signal.

2.6. Periods Ensemble Processing

This section introduces the methodology for processing cardiac signal periods within a synchronized ensemble framework. By selecting and aligning periods from various signals, such as EBI, CAP, and ECG, we ensure that only valid and simultaneous cardiac periods are analyzed. Subsequent steps, including outlier detection and normalization, refine the data further to create representative and averaged period ensembles. Detailed descriptions of each processing step are provided in the subsections that follow.

2.6.1. Periods Ensemble Synchronization

When all periods were found, we synchronized these periods, by storing only simultaneous periods found in all the signals, EBI RAP and CAP. All cardiac periods, which were presented only in one signal, were ignored and excluded from further analysis.

2.6.2. EBI and CAP Periods Selection

After extracting the cardiac component, the periods detection algorithm was applied to the impedance and BP cardiac signals.

2.6.3. ECG Periods Selection

ECG signal periods were selected using the time frame of the impedance corresponding to the periods shifted back in time by 300 ms (to obtain the whole ECG period). The starting points of the periods (the B point in

Figure 2 and in

Figure 3) were obtained from the first-order derivatives of the corresponding signals (EBI, CAP and RAP). The location of the B point is defined as the time instance when the value of the signal’s first derivative

increases above the threshold level

, with

as the maximum value of the signal’s first-order derivative.

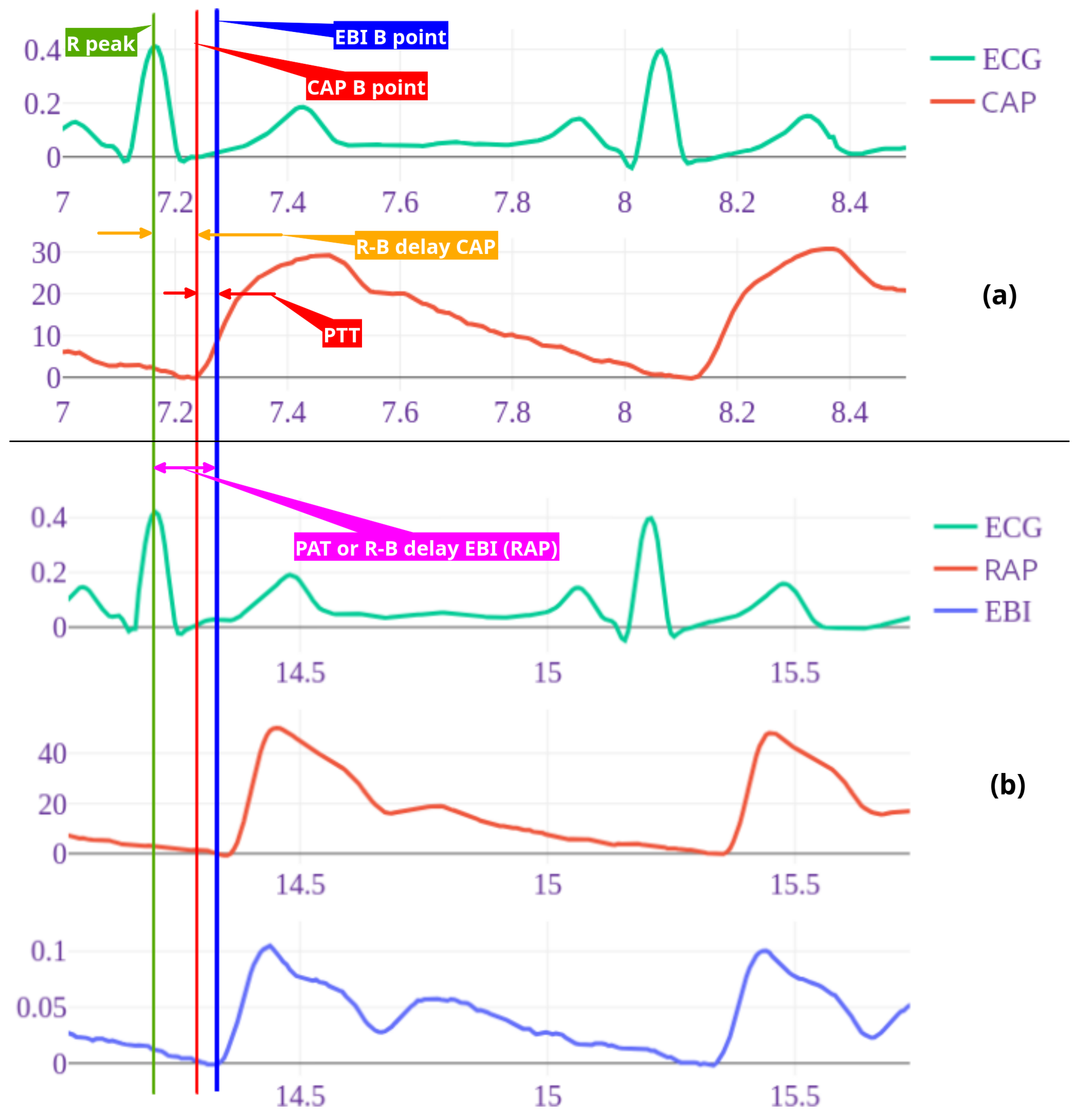

Figure 3.

Example of wave recordings and time points for patient nr 3. ECG and central pressure recording (a) followed by Radial artery pressure and EBI recordings taken simultaneously with ECG (b). Timelines are shown with vertical lines as follows: green – ECG R peak, blue – radial arterial pressure (RAP) and EBI B point, red – central arterial pressure B point. R-B delay radial (RAP/EBI) interval, also pulse arrival time (PAT) with purple arrow and central (CAP) R-B delay with orange arrow. Pulse arrival time (PAT) is time from R peak to peripheral (RAP B point) and pulse transit time (PTT) is time between central and distal pressure wave B points (red arrow). Note: here shown 2 cycle recordings, for calculations 7-10 cycles were used.

Figure 3.

Example of wave recordings and time points for patient nr 3. ECG and central pressure recording (a) followed by Radial artery pressure and EBI recordings taken simultaneously with ECG (b). Timelines are shown with vertical lines as follows: green – ECG R peak, blue – radial arterial pressure (RAP) and EBI B point, red – central arterial pressure B point. R-B delay radial (RAP/EBI) interval, also pulse arrival time (PAT) with purple arrow and central (CAP) R-B delay with orange arrow. Pulse arrival time (PAT) is time from R peak to peripheral (RAP B point) and pulse transit time (PTT) is time between central and distal pressure wave B points (red arrow). Note: here shown 2 cycle recordings, for calculations 7-10 cycles were used.

2.6.4. Periods Outliers Sifting

Thereafter, all saved periods were filtered from outliers by the period signal waveform. Consequently, all the periods of the selected signals (EBI, CAP, RAP and ECG) were put into corresponding ensembles. For each ensemble, a three-step procedure for outlier detection was introduced:

All three steps were applied sequentially. When some period after outlier detection was presented only in one collection, it was excluded from further analysis.

2.6.5. Periods Normalization

After the collection of accepted periods, they all were normalized in time by resampling (for each ensemble individually) to the same duration. The duration of the normalized period was estimated as the median duration of all periods in the set. Then, the ensemble averaged periods were obtained from the normalized period ensembles.

2.7. Features Selection

In this section, we outline the key features considered for the simplified noninvasive heart-to-arm pulse-wave velocity (PWV) analysis. Each feature is carefully selected to improve the accuracy and reliability of the proposed methodology. The features include fiducial points, time intervals, pulse arrival time (PAT), pulse transit time (PTT), and the newly proposed complementary pulse wave velocity (CPWV). These features form the foundation of the analytical framework discussed in subsequent subsections.

2.7.1. Fiducial Points Features

The selected fiducial points (described in

Section 2.5.1, and shown in

Figure 2) B, C, F, G and D were estimated for EBI and AP signals, and R and Q were estimated for ECG, respectively. For further analysis, time instances and values for the B, C, F, G and D points were scaled back to the original time scale, after ensemble averaging, and stored into the table. The time instances of the detected points were related to the beginning of the period, presented as point B.

2.7.2. Time Intervals as Features

Furthermore, delays from the R peak to the B points of the EBI/RAP and CAP signals (

Figure 3) were estimated and used in the following analysis. For each simultaneous period, these delays were individually estimated. For the final analysis, the median delay was used for all ensemble periods.

2.7.3. PAT and PTT as Features

The invasive pressure-based and non-invasive volume-based pulse arrival time (PAT) was calculated. For invasive pulse arrival time (

) to distal radial artery we measured time in seconds from R-peak in ECG to beginning point of the radial pressure (

) and for noninvasive pulse arrival time (

) beginning point of radial bioimpedance (

), point B in

Figure 2 (see also

Figure 3). For pulse transit time (PTT) we measured time from ECG R peak to B point on CAP and thereby calculated time between

and

points (

delay minus

delay in

Figure 3).

2.7.4. PWV as Features

For direct PWV calculations from the aortic valve to the distal radial artery, the distance with the Pigtail catheter was measured and the pressure curves above the aortic valve (CAP) and in distal radial artery were recorded as described in the Methods section. The pulse transit time (PTT) was calculated (

1) by subtracting

from

:

where

is the velocity of the pulse wave,

is the distance between the aortic valve and the distal radial artery, in meters.

is pulse arrival time for radial artery pressure and

the pulse arrival time for central aortic pressure

2.7.5. CPWV as Features

For the non-invasive PWV calculation we used the fixed distance value 0.8

as the median radial aortic length of our investigated patients and the value

in seconds. For this simplified noninvasive heart-to-arm PWV, we propose new term Complimentary Pulse Wave Velocity (CPWV).

For direct pulse-wave velocity calculations both time instances for the B point of the wave should be registered at the beginning of the wave propagation and at the end of the wave propagation process (e.g., close to the heart and on the radial artery). However, using the non-invasive EBI measurement in the radial artery, we can only register the wave propagation at the end point of the vasculature of interest. Consequently, for the proposed approach we assume that the time interval from the ECG R peak to the EBI B point does not change significantly as the measurements are performed in relatively healthy subjects without cardiac arrhythmia or high pulse rate situations such as exercise, fewer, or cardiac emergencies.

Therefore, we propose to use the

time interval and the median arm length of the researched patients as a basis for the proposed estimate of CPWV (

2), and the results for CPWV together with PWV are shown in Figure 11.

3. Results

In this study, data from 44 subjects were analyzed. The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study patients are presented in

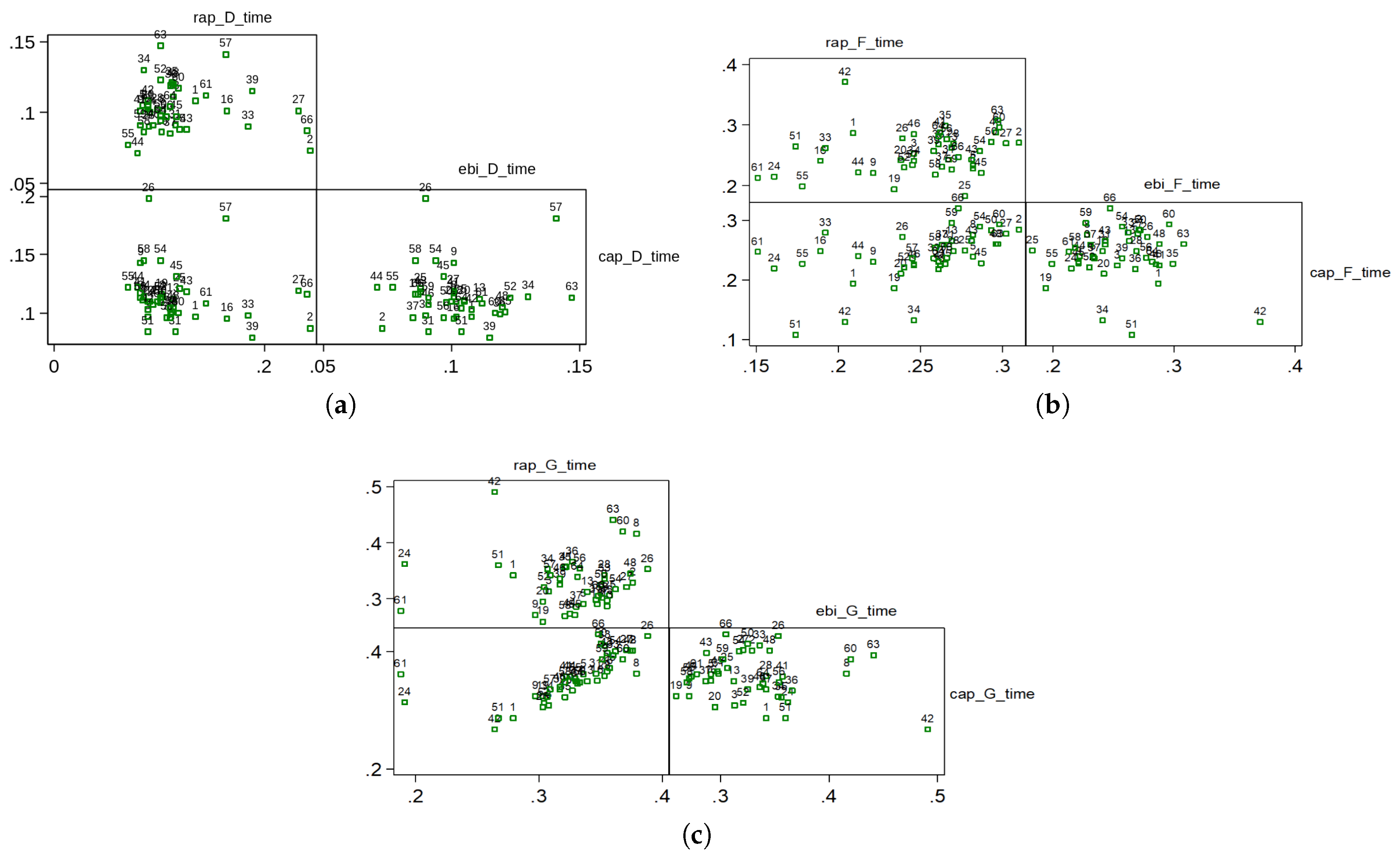

Table 1. Pulse wave velocities between the aortic valve and the distal radial artery were calculated as described in the section on methods. For the statistical analysis in the paper, Spearman rank correlation coefficient is used due to the small number of patients. The correlations between the D, F and G time points on the pressure and bioimpedance curves are presented in

Figure 4 and in

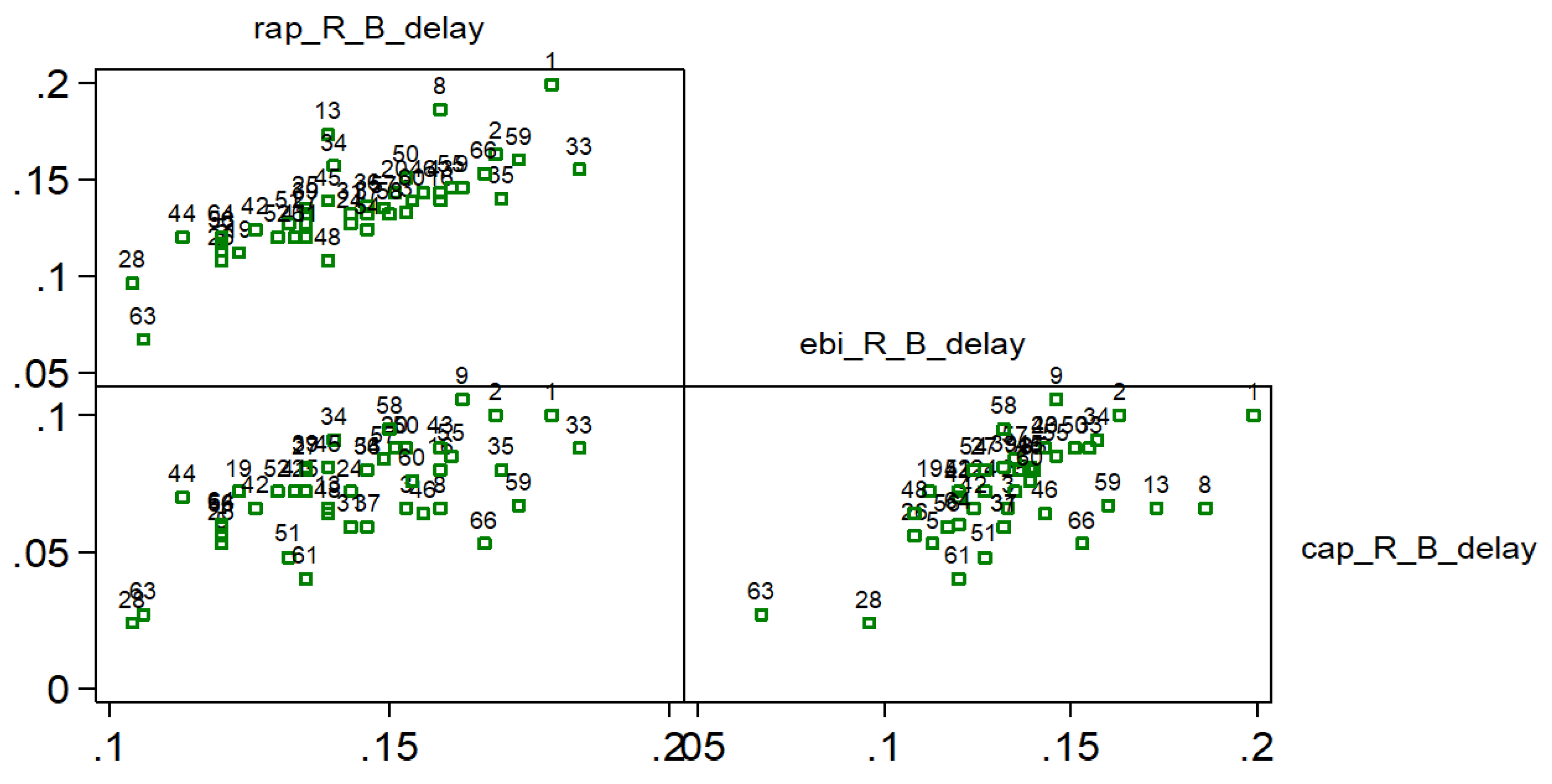

Table 2, where a strong correlation is found between the times of the RAP and CAP G points.

Strong positive correlation (0.844) was found between R-B delay of RAP and EBI curves. R-B delay defined as time from R-point of ECG and B point of RAP and EBI curves (

Figure 6, study patients are presented with numbers).

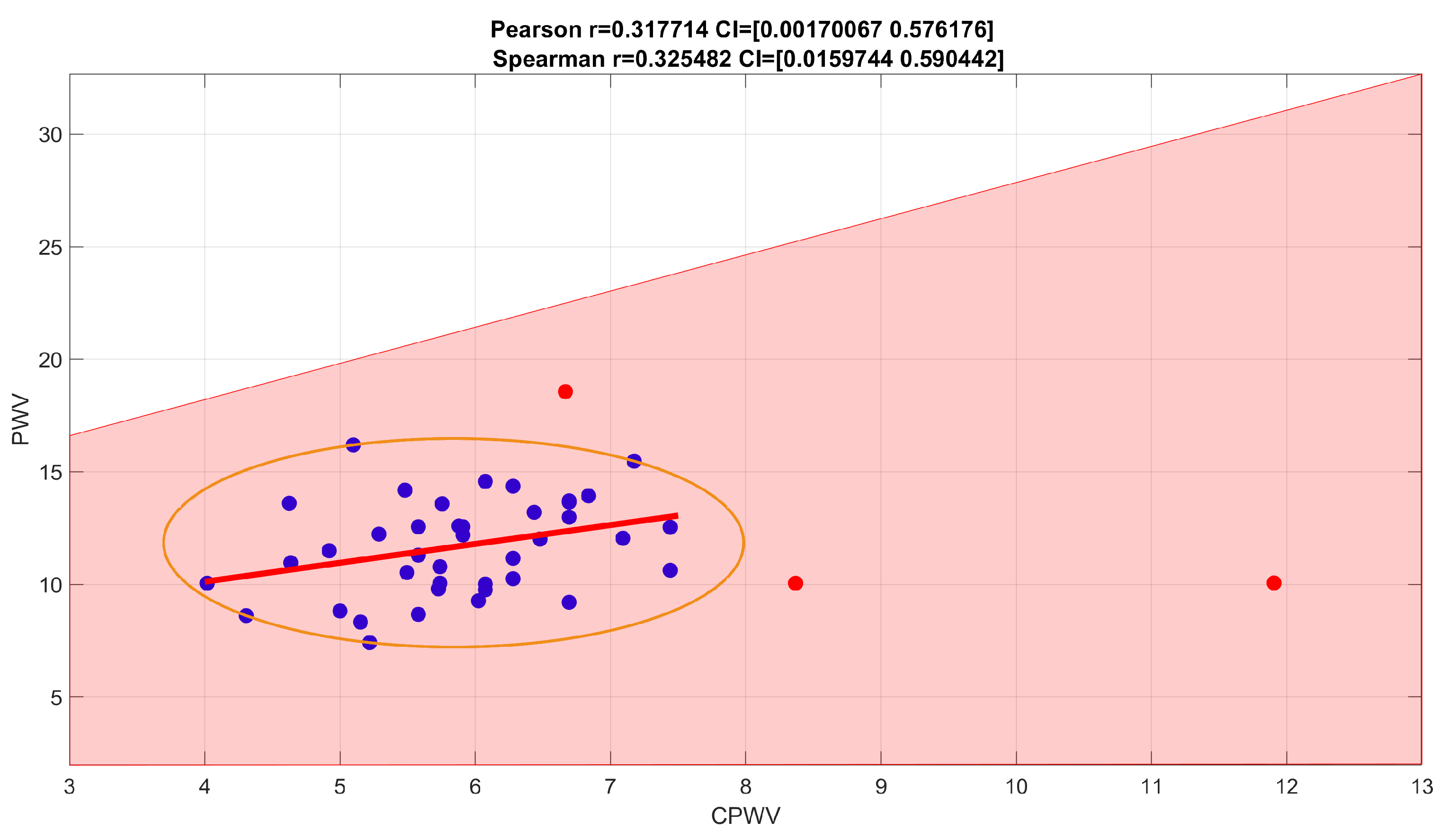

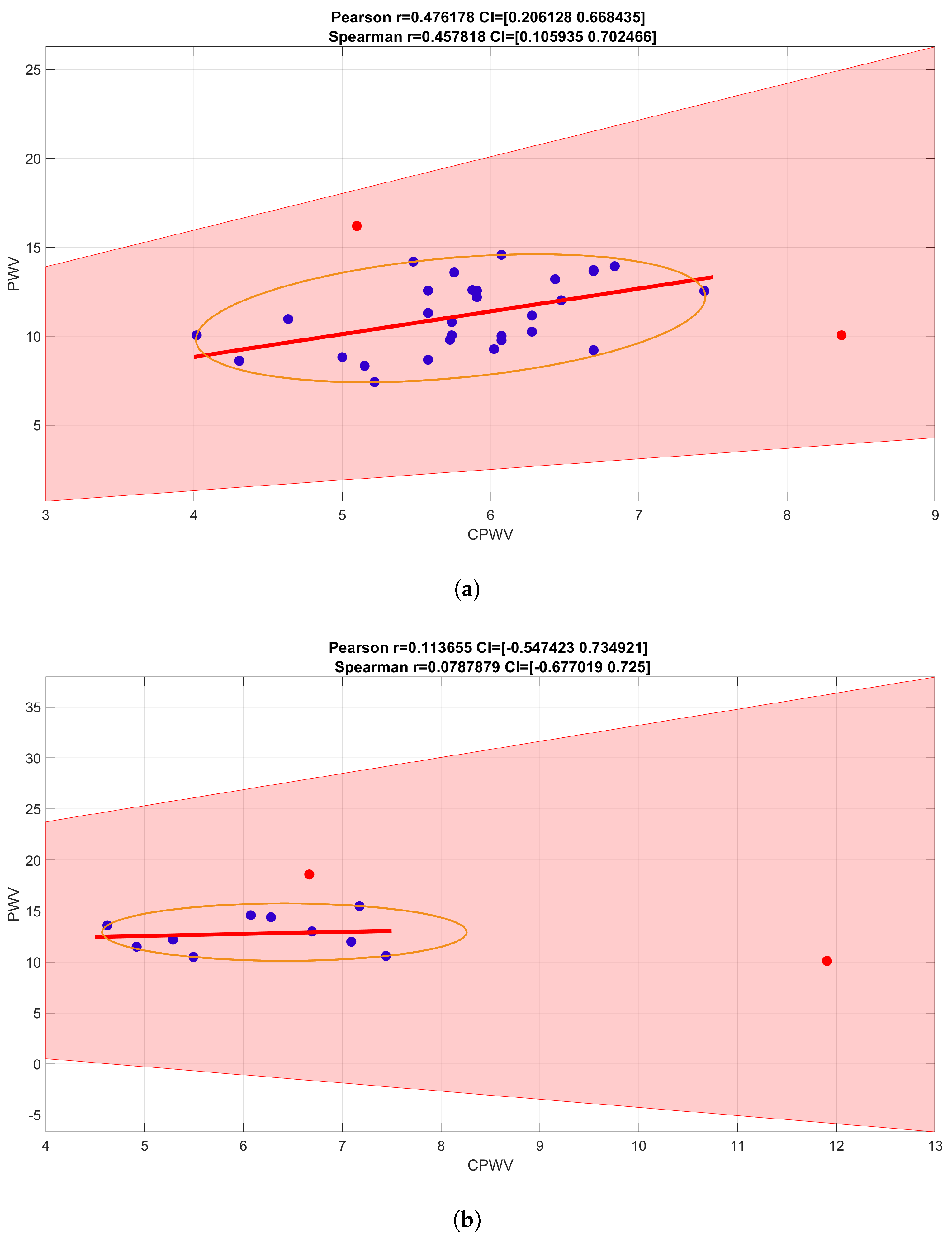

PWV calculations based on invasive (radial artery pressure, RAP) and non-invasive (radial electrical bioimpedance, EBI) R-B delay showed a moderate positive correlation with Spearman correlation coefficient 0.3255, confidence interval (0.0160, 0.5904) (

Figure 7), similar correlation is shown in male gender group while female group is too small to make suggestions (

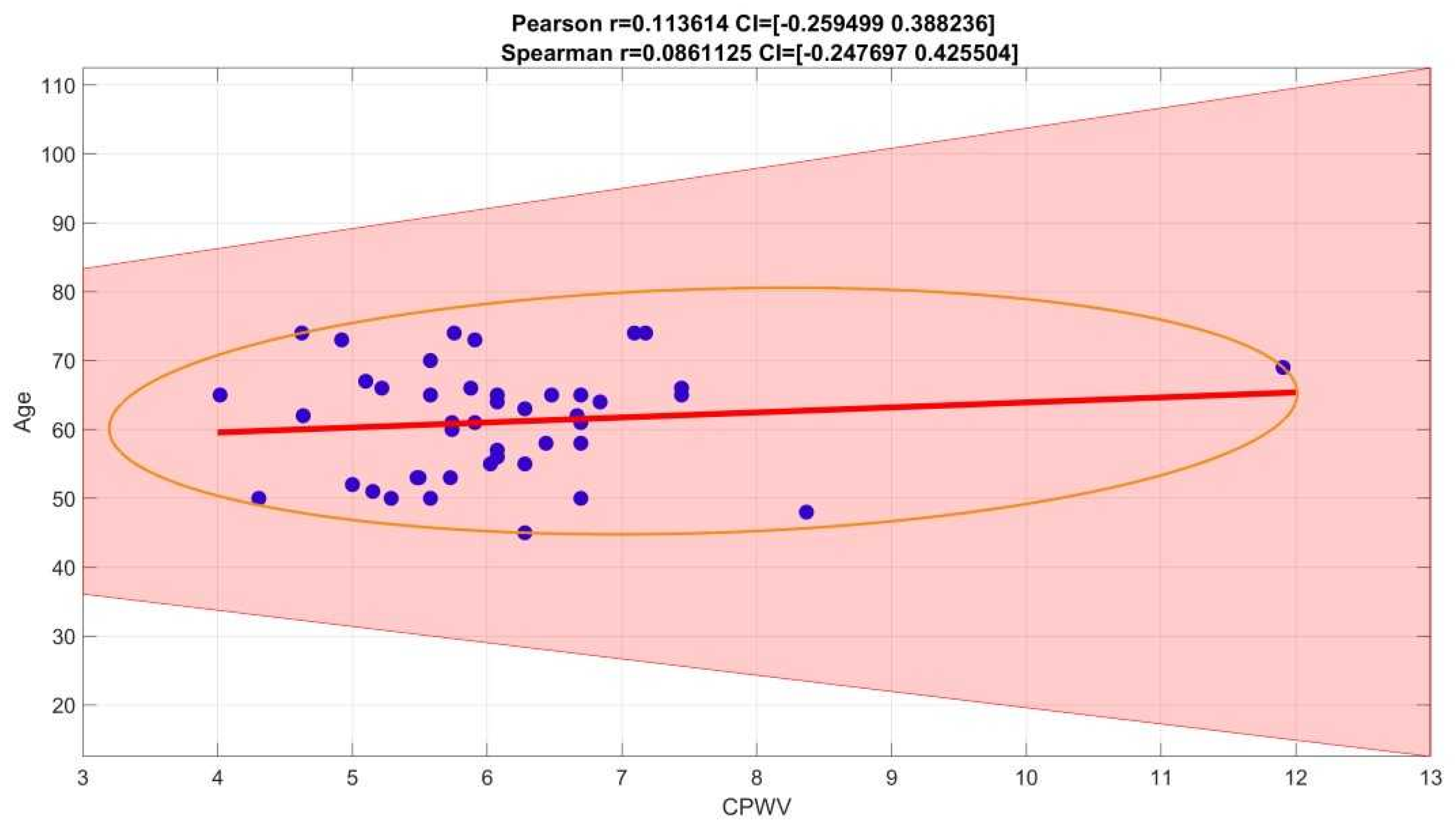

Figure 9). In our group of patients (aged 45-74 years, moderate to high cardiovascular risk) PWV is not affected by age (

Figure 8).

We pre described six groups of common cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, smoking, diabetes mellitus, overweight with BMI > 35, atherosclerosis in other vascular territories (stroke, peripheral arterial disease, etc.). Hypercholesterolemia was considered as risk factor if not treated, because of vasoprotective effect of statins when used in hyperlipidemia treatment. In our group only 2 patients had none of these risk factors as well only 2 had four risk factors, there were no patients with 5 or 6 risk factors (

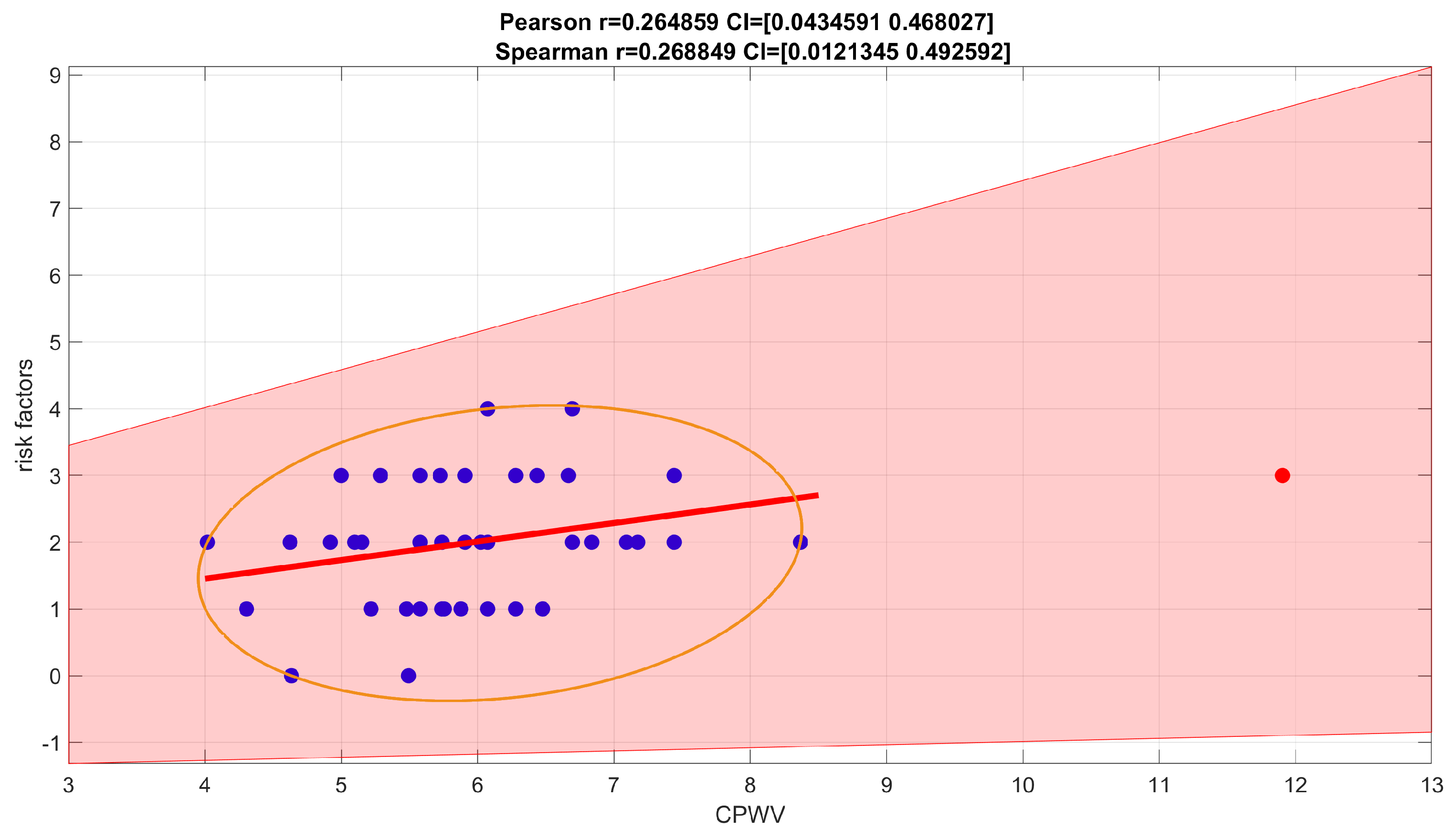

Table 1) . Correlation between risk factors and CPWV in our patient groups, shown in

Figure 10, was weak, Spearman correlation coefficient 0.2688, confidence interval (0.0121, 0.4926).

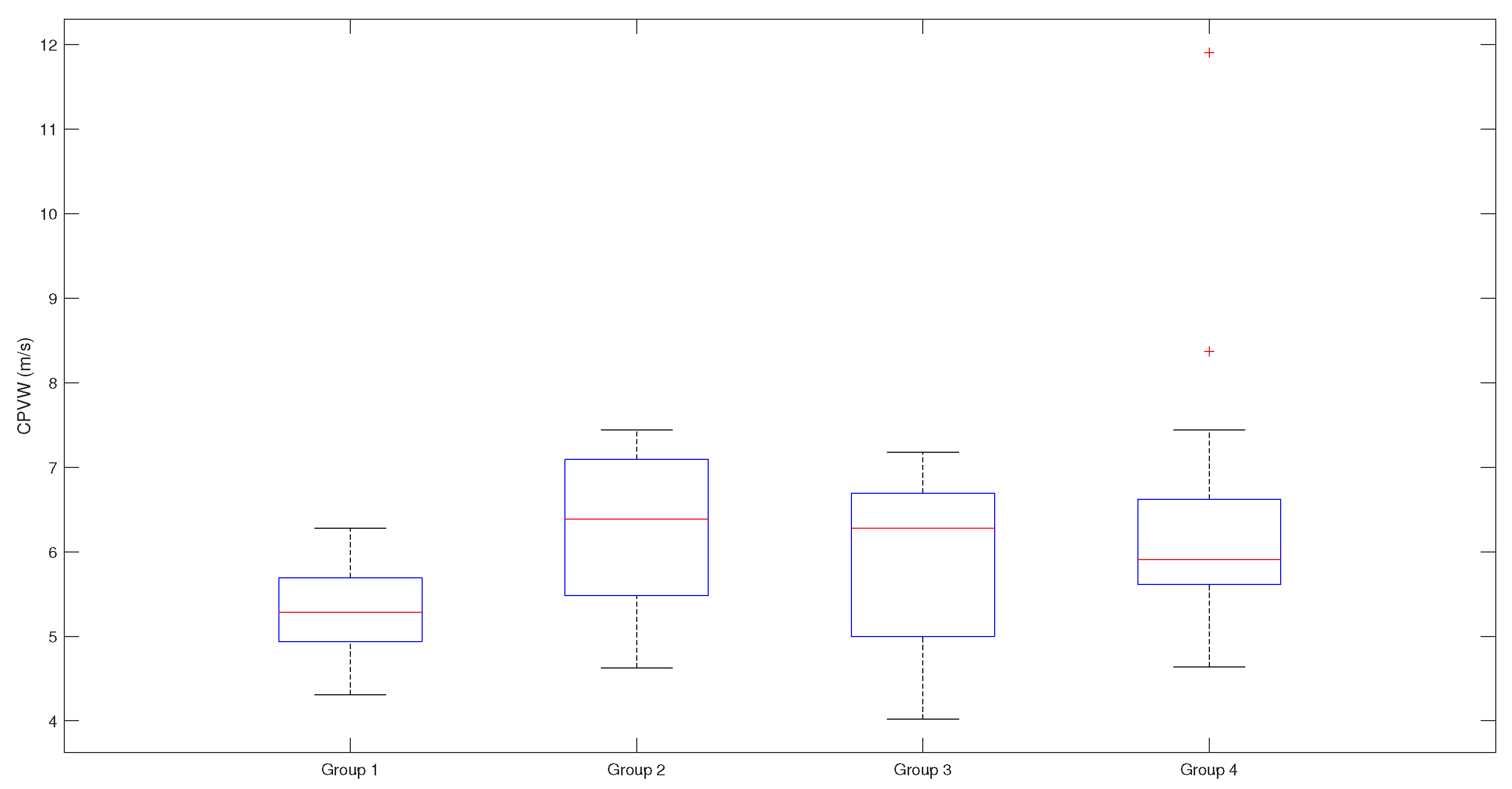

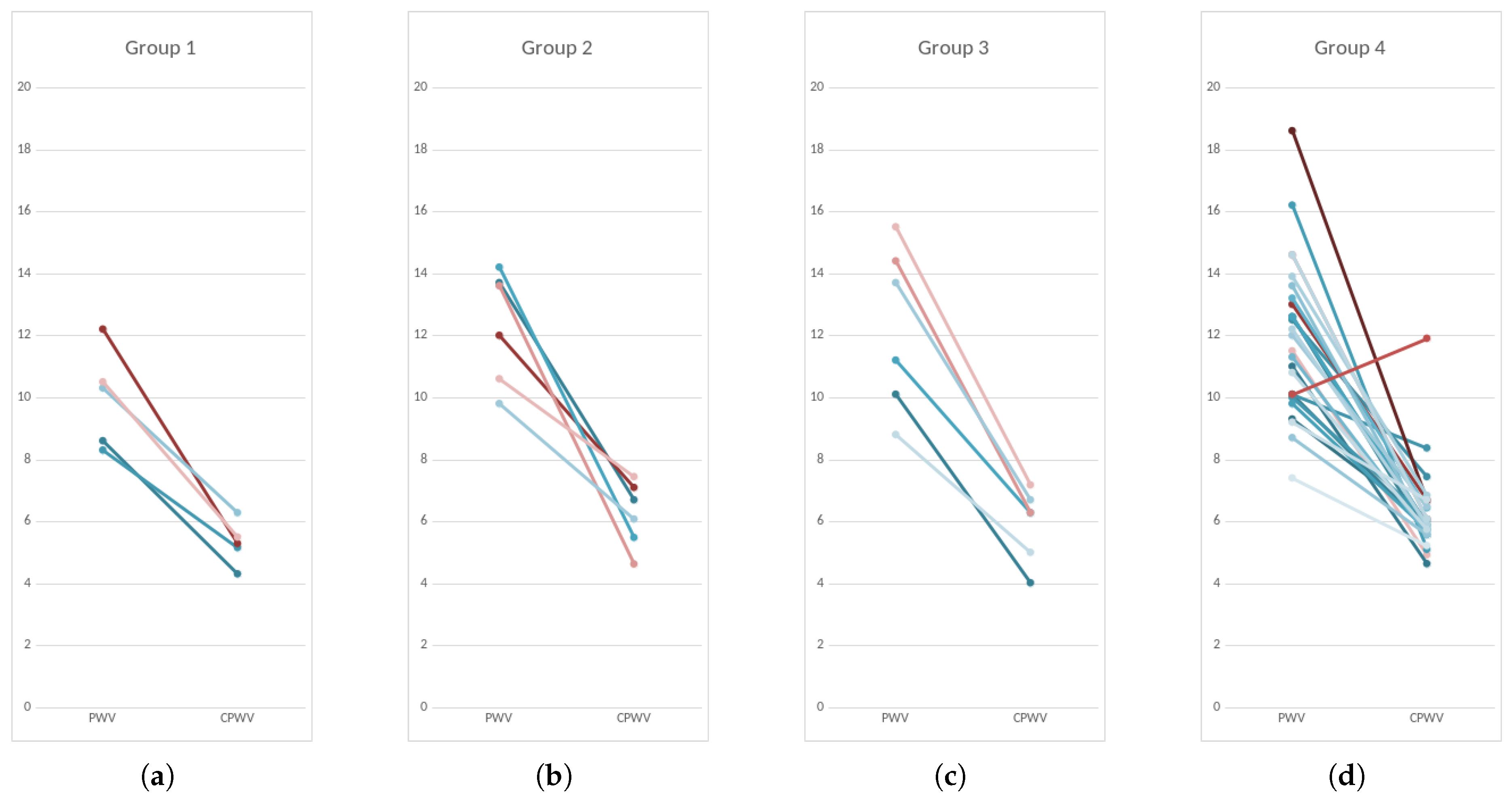

Based on coronary lesions we formed four groups of patients – first group with normal coronaries, second group with minimal/moderate changes (≤50)% stenoses, third group with moderately significant coronary lesions (51–75)% stenoses, non-revascularization objects, 1-2 vessel disease) and fourth group with significant (51–100)% stenoses that are objects of revascularization and three-vessel disease (

Figure 11 and

Figure 5).

Figure 5.

CPWV range and median in patient groups with different stages of coronary disease. Patients with coronary lesions present with higher CPWV values compared to patients with normal coronaries. There is moderate difference between median values of group 1 and groups 2-4, p-value is 0,0404; CPWV- complimentary pulse wave velocity; Patient groups: Group 1 – normal coronaries; Group 2 – with coronary stenoses ≤50%; Group 3 – with coronary stenoses (51–75)%, non-revascularization objects, 1-2 vessel disease; Group 4 – with coronary stenoses (51–100)% that are objects of revascularization and three-vessel disease.

Figure 5.

CPWV range and median in patient groups with different stages of coronary disease. Patients with coronary lesions present with higher CPWV values compared to patients with normal coronaries. There is moderate difference between median values of group 1 and groups 2-4, p-value is 0,0404; CPWV- complimentary pulse wave velocity; Patient groups: Group 1 – normal coronaries; Group 2 – with coronary stenoses ≤50%; Group 3 – with coronary stenoses (51–75)%, non-revascularization objects, 1-2 vessel disease; Group 4 – with coronary stenoses (51–100)% that are objects of revascularization and three-vessel disease.

Figure 6.

Scatterplots and Spearman rank correlation coefficients for R-B delays. 0.844 for R-B delay , 0.573 for and 0.581 for ; Studied patients are presented with numbers; (0.7–0.9) is high positive correlation (0.5–0.7) is a moderate positive correlation; rap – radial artery pressure, ebi – electrical bioimpedance, cap – central aortic pressure, R – electrocardiogram R peak, B – start point of pressure/ebi curve.

Figure 6.

Scatterplots and Spearman rank correlation coefficients for R-B delays. 0.844 for R-B delay , 0.573 for and 0.581 for ; Studied patients are presented with numbers; (0.7–0.9) is high positive correlation (0.5–0.7) is a moderate positive correlation; rap – radial artery pressure, ebi – electrical bioimpedance, cap – central aortic pressure, R – electrocardiogram R peak, B – start point of pressure/ebi curve.

Figure 7.

Spearman rank correlation coefficients for PWV calculations based on direct blood pressure curves and EBI curves. Spearman correlation coefficient 0,2650 with confidence interval (−0.0327, 0.5305) indicates a weak positive correlation (with outliers (red points) removed, Spearman correlation coefficient is 0.3255, with confidence interval (0.0160, 0.5904), and indicates stronger positive correlation.

Figure 7.

Spearman rank correlation coefficients for PWV calculations based on direct blood pressure curves and EBI curves. Spearman correlation coefficient 0,2650 with confidence interval (−0.0327, 0.5305) indicates a weak positive correlation (with outliers (red points) removed, Spearman correlation coefficient is 0.3255, with confidence interval (0.0160, 0.5904), and indicates stronger positive correlation.

Figure 8.

Spearman correlation coefficient for age and CPWV is 0,0861125, confidence interval (−0.2476970, 425504)

Figure 8.

Spearman correlation coefficient for age and CPWV is 0,0861125, confidence interval (−0.2476970, 425504)

Patients with mild to significant coronary lesions, shown in

Figure 11, present with higher PWV values compared to patients with normal coronaries (median values 12 m s

−1 and 10 m s

−1 accordingly,

). The same pattern but with lower velocities can be observed with CPWV, (median values for patients with coronary disease (6–6.4) m s

−1 and 5.3 m s

−1 for patients with normal coronaries. The difference of CPWV means is statistically significant with

p-value 0.0448, Bayes factor BF10: 288, that there is very weak evidence that means of group 1 with normal coronaries and and other groups with any level of coronary disease are different (

Figure 5 ).

Therefore, we propose to use the

time interval and the median arm length of the researched patients as a basis for the proposed CPWV estimate (

2), and the results for CPWV together with PWV are shown in

Figure 11 and in

Figure 11.

Figure 9.

PWV and CPWV correlations for male (a) or female (b) gender. Spearman correlation coefficient for male group is 0.3124, confidence interval (−0.0785, 0.6151) – weak (with outliers removed, moderate) correlation. Female (b) gender group is too small to make suggestions.

Figure 9.

PWV and CPWV correlations for male (a) or female (b) gender. Spearman correlation coefficient for male group is 0.3124, confidence interval (−0.0785, 0.6151) – weak (with outliers removed, moderate) correlation. Female (b) gender group is too small to make suggestions.

Figure 10.

Spearman correlation coefficient for number of risk factors. For a number of risk factors (0-4 coexistent risks for this patient group) and CPWV correlation coefficient is 0.2688, confidence interval (0.0121, 0.4926) which indicates a weak positive correlation.

Figure 10.

Spearman correlation coefficient for number of risk factors. For a number of risk factors (0-4 coexistent risks for this patient group) and CPWV correlation coefficient is 0.2688, confidence interval (0.0121, 0.4926) which indicates a weak positive correlation.

Figure 11.

PWV and CPWV (EBI derived PWV) in different patient groups according to coronary disease. Every line represents one patient. Left dots – PWV calculated from invasive arterial pressure ( PWV rap) and right dots CPWV calculated from EBI curve (PWV ebi); Group 1 – normal coronaries; Group 2 – with coronary stenoses ≤50%; Group 3 – with coronary stenoses (51–75)%, non-revascularization objects, 1-2 vessel disease; Group 4 – with coronary stenoses (51–100)% that are objects of revascularization and three-vessel disease.

Figure 11.

PWV and CPWV (EBI derived PWV) in different patient groups according to coronary disease. Every line represents one patient. Left dots – PWV calculated from invasive arterial pressure ( PWV rap) and right dots CPWV calculated from EBI curve (PWV ebi); Group 1 – normal coronaries; Group 2 – with coronary stenoses ≤50%; Group 3 – with coronary stenoses (51–75)%, non-revascularization objects, 1-2 vessel disease; Group 4 – with coronary stenoses (51–100)% that are objects of revascularization and three-vessel disease.

4. Discussion

Blood pressure values and its pressure curve characteristics is not a constant value through arterial tree, it becomes modified as it travels away from the heart towards the periphery, whereas the changes between central and peripheral pulse pressure depends not only propagation characteristics of arteries [

3,

15] but also microvasculature [

29,

30] and cardiac rate [

31]. This back-and forth influences generate circulus vitiosus, also called ‘amplifier hypothesis’ [

32]. Understanding physiological mechanisms and the difference between central and peripheral systolic pressure and pulse contour is significant in relating the conventional cuff measurements on the arm to CV function. In order to determine vascular parameters to complement the conventional BP measurement by the cuff sphygmomanometer, various methods of pulse detection have been developed that utilize waveform features for the estimation of arterial elastic properties [

3]. Noninvasive assessment of central BP has become widely available and officially recognized in recent years [

12]. Although the available techniques have limitations, it has been accepted that they may provide further complementary data to peripheral BP, regarding the management of arterial hypertension and CV risk [

14]. In the transmission of blood, arterial BP, ECG and pulse wave signals reflect the different functions of the cardiovascular system and blood flow information [

33]. According to the arterial wave propagation theory, the start point and the end point signals of the arterial path are extracted, and PTT can be calculated and used to determine CV functional status, such as BP, arterial stiffness, and arterial compliance [

33]. The present study focused on a correlation analysis which was conducted to estimate arterial wave propagation theory by using the EBI method and explore its effectiveness in monitoring vascular tone. Technical aspects of bioimpedance curve calculations are described previously in our work [

26], PWV is a gold standard to measure vascular stiffness and estimate cardiovascular risk [

21]. Traditionally assessments are made on carotid-femoral axis which is costly, inconvenient for routine ambulatory measurements, and may cause the complications if performed invasively. Additionally, this measurement becomes fused in the presence of lower-extremity arterial disease [

34]. For these reasons, we chose aortic valve to arm axis to exclude most of the aorta and lower limb arteries and compared invasive pulse wave measurements with noninvasive ones delivered from EBI recordings. Invasive methods are still considered gold standard, so we used for reference common cardiac catheterization pathway that begins with right distal radial artery and follows the vasculature back to aortic valve. EBI method provides more comfortable cuffless measurement that is more suitable for continuous monitoring, both important factors of patient comfort and activation affecting the overall recovery process [

35] and safety [

36].

For invasive PWV calculation the true distance could be used as pressure recording catheter is inserted from the distal measurement point and placed just above aortic valve, so the internal catheter length can be defined. For noninvasive calculations we performed EBI measurements on contralateral wrist corresponding to radial artery puncture places and ECG recordings from chest, the distance was calculated as mean invasive distance. We succeeded to demonstrate strong correlations between radial CAP and EBI R-B delays (that can also be defined as PAT). Our method faced multiple technical tasks, as EBI signal is very movement sensitive and needs filtering, direct distance measuring during invasive procedure may not be the most precise, single-channel ECG recorded waves can be poorly detectable for computational analysis and even healthy subjects may not have laterally uniform pulse wave propagation. Some of these problems are discussed in further text.

For signals filtering we used the Savitzky-Golay filter for the signals smoothing and Hankel matrix-based signal decomposer for extracting the cardiac component from the raw signals.

Distance measurement techniques and their accuracy for PWV calculation are at great variability [

37]. We chose aortic-arm axis as carotid-femoral axis may be more affected of subject’s height [

38] and vessel elongation. For direct measuring we considered possible error ± 2 cm acceptable if otherwise standardized method for measurement is used including catheter distal end placement verification by fluoroscopy. The anatomical differences between arteries of the arms could result in different BP [

39], but not PAT [

40]. Pitfall of measuring BP or PAT in one arm is missed arterial occlusion or significant stenosis and thereby erroneous reading. This can be easily overcome by first measuring BP on both arms, as suggest guidelines [

41] and was done in our study. Not only that every 5 mmHg difference identifies higher cardiovascular risk [

42] but over 30 mmHg may indicate subclavian arterial occlusion [

43], if in this situation pulsatile radial flow is present and measured, it would be collateral flow, including subclavian steal syndrome through intracranial circulation [

44] and measuring PWV may be misleading. Thereby, patients with significant inter-arm pressure should be managed differently and are not subjects of screening methods as PWV measurement.

For distal arterial waveform analysis, we recorded EBI on left wrist as investigation method and for right radial invasive pressure curve for reference, both with ECG recordings. For additional information central pressure curves above aortic valve were recorded. Different arterial and pressure curve characteristic points were identified according to previous authors [

3,

45,

46,

47] and named in alphabetical order from B to H, to differentiate our own computational analysis points from classical points as similar practice from other authors [

23,

45]. In this stage of study, we used these fiducial points only for describing the pressure curves and verifying the EBI curves, the further analysis will be subject of following studies.

Computational analysis of recorded hemodynamic curves bases on automatic recognition of certain points and time intervals of clinical significance of pressure or volume curves. We were able to show correlations between the D, F, and G time points on the pressure and bioimpedance curves and a strong correlation between the RAP and CAP G point. We also could show strong positive correlation between R-B delay of RAP and EBI curves, thereby confirming in our study that the radial invasive pressure curve could be replaced by bioimpedance-based curve measurement to generate noninvasive measurement.

There is considerable heterogeneity of measurement sites and techniques to obtain the waveform for PWV calculations [

48]. For defining PAT, we used the most definable and also the most used ECG R peak [

49] instead of R onset and volume wave (EBI) curve beginning/onset (EBI-B) as PAT (onset) is preferred over PAT (peak) due to its higher physiological correlation [

49]. PAT is not only a good surrogate marker for PTT but contains more information such as the time delay between the electrical depolarization of the left ventricle of the heart and the opening of the aortic valve, known as the pre-ejection period (PEP) [

50]. For these reasons we used PTT for invasive PWV calculations and PAT for EBI derived PWV calculations, and to distinguishing proposed the term CPWV for PAT derived noninvasive PWV.

PWV increases normally with age; its mean values are less than 6 m s

−1 in the twenties and more than 8 m s

−1 in subjects over 60 years old [

51]. For increased cardiovascular risk, common threshold values for arterial stiffness are > 10 m s

−1 for carotid–femoral PWV and > 14 m s

−1 for brachial–ankle PWV [

2]. The presence of an isolated PWV >13 m/s is strong predictor of cardiovascular mortality [

52]. As PTT is shorter than PAT, the values of CPWV are considerably shorter than PWV values and thereby the new cutoff values for different risk groups are needed.

We could show only moderate difference between CPWV in different groups of patients, one reason may be the absence of a truly healthy group and a relatively homogeneous cardiovascular risk group, since all patients were considered high risk and scheduled for coronarography. Some of the common cardiovascular risk factors were for technical reasons exclusions in our study, like atrial fibrillation, heart failure, aortic valve and aortic diseases. It is also known that vascular atherosclerosis begins with soft plaque formation and positive remodeling far before visual changes appear on coronarography [

53] and not all stenoses cause cardiac events, a situation called visual-functional mismatch [

54]. For the same reason our 3-rd and 4-th groups start with 51% lesions and are differentiated by operators opininon whether they are objects of revascularization or not. Therefore, more sophisticated methods for intravascular diagnostics, for example, intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) with lipid core detection by near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) [

55] and FFR with IMR [

56] could be used to describe vascular damage and regroup patients. By grouping individuals according to the true stages of atherosclerotics, CPWV and other characteristics of the bioimpedance arterial curve can be more precisely calibrated, which can offer significant value in preventive medicine.

5. Conclusions

Measurement of PAT and calculation of PWV is the first step in analyzing the EBI waveform, with better quality and artifact-free recordings, more time and slope analyses of single waveform and also detection of changes during follow-up. Complementary quantifiable information on the arterial pulse waveform can provide a markedly improved means of non-invasive characterization of CV function and better stratification of CV risk [

3] and could lead to innovative clinical applications, developed in collaboration with the medical device industry, and used in various cardiovascular fields, including ambulatory and patient self-management settings, as well as in hospital and acute care environments.

Monitoring peripheral EBI variations is a promising method that has the potential to replace invasive or burdensome techniques for cardiovascular measurements. With regard to wearable devices, the EBI-derived PAT can serve as a substrate to blood pressure calculations or cardiovascular risk assessment, although these data require further confirmation.

However, the study had some limitations. First, the study was conducted in a relatively small number of patients. Second, the control group with normal coronaries can not be defined as reference or healthy group because visual estimation of coronaries can significantly over- and underestimate real vascular pathology. Third, several aspects of data acquisition and signal processing need further refinement. Investigation is needed for optimal placement of the electrodes, more efficient suppression of different measurement artifacts, optimal selection of measurement time points and sequence lengths, to name a few.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, K.L., T.U., A.K, M.Min, M.R. and P.A.; software, A.K.; validation, K.L. and T.U.; formal analysis, K.L, A.K. and G.T.; resources, K.L. and S.M.; data curation, K.L., T.U.; writing—original draft preparation, K.L., T.U., A.K and P.A.; writing—review and editing, M.Mets., G.T. and M.R.; visualization, A.K, K.L. and G.T.; project administration, supervision, K.L., M.Min and S.M; funding acquisition, M.Min, K.L, T.U. and S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.