1. Introduction

Millions of individuals in Africa have been receiving antiretroviral treatment (ART) based on Dolutegravir (DTG) since the significant transition to new treatment regimens in 2019-2020. This shift was primarily driven by the World Health Organization (WHO), which advocated for DTG as the preferred option for both first and second-line ART due to its substantial clinical benefits [

1]. However, limited guidance has been provided to countries on identifying and managing resistance to DTG in scenarios with restricted access to genotype testing, such as in Mozambique. Many countries continue to encounter significant barriers to implementing new algorithms that incorporate genotyping capabilities [

2].

In Mozambique, the decision to switch ART regimens is made based on pragmatic clinical observations due to the unavailability of HIV genotype resistance testing (HIV-GT) within the public health system [

3]. With the advent of DTG and the increasing availability of more consistent treatment regimens alongside expanding access to viral load monitoring, suppression rates have improved significantly [

1,

4]. Consequently, only a small percentage of PLWH may require a change in their treatment regimen [

1].

In this scenario, it is essential to establish innovative strategies for identifying PLWH who require resistance testing and, ultimately, a revised ART regimen.

Since 2016, efforts by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and subsequently the International Training and Education Center for Health (I-TECH-Mozambique [

5]) have facilitated access to HIV-GT at the Alto Maé Referral Centre in Maputo. This report presents data from a programmatic intervention focused on HIV genotype resistance testing within a cohort of PLWH with extensive exposure to ART in a resource-limited setting.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

According to the INSIDA 2021 survey, it is estimated that the prevalence of HIV in Maputo City stands at 16.2% among individuals aged 15 and older [

6]. Furthermore, as reported by the Health Information System for Monitoring and Evaluation (SIS-MA) of MoH, Maputo City had a cumulative total of 170,161 people living with HIV (PLWH) who were receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) by mid-2024 [

7].

In 2003, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) established the Centro de Referência de Alto-Mae (CRAM) in collaboration with the Ministry of Health (MoH) as an outpatient center dedicated to the referral of PLWH with advanced HIV disease (AHD) and those suspected of experiencing failure with second-line ART regimens from the broader Maputo urban area [

5]. In December 2020, management of CRAM was transitioned to ITECH-Mozambique [

8]. The center continues to receive PLWH from the health network within Maputo city.

The CRAM database maintains a cumulative registry of 25,432 individuals living with HIV, of which 1,819 remain actively engaged in care as of July 2024. CRAM provides a range of outpatient services, including rapid screening and management of AHD, chemotherapy for Kaposi Sarcoma, treatment of Multidrug Resistant Tuberculosis, as well as confirmation and follow-up care of PLWH exhibiting resistance to ART [

9].

2.2. Study Design and Population

This cross-sectional assessment of routine programmatic data was conducted to guide future program enhancements. The included data were retrospectively collected as part of the treatment failure program (TFP) from CRAM between July 2020 and February 2024. Eligible participants included individuals of all ages who had access to HIV-GT.

2.2.1. Eligible Participants

The eligibility criteria for accessing a genotyping test at CRAM, as per our internal algorithm, included the following: First, non-naive PLWH on ART, irrespective of WHO/AIDS clinical staging and/or CD4 count; Second, PLWH who had been exposed to ART for a minimum of 24 months; Third, individuals exhibiting persistent high viral load, defined as at least two consecutive results exceeding 1000 copies/ml, prior to enrollment in the treatment failure program; Fourth, persistent high viral load following at least three consecutive adherence counseling sessions after entering the treatment failure program; Five, persistent high viral load after a 4-week supervised treatment intervention.

The sole exclusion criterion for eligibility to undergo a genotyping test was a viral load result of less than 5000 copies/ml after adherence support interventions. This limitation arises from the inherent constraints of dried blood spot (DBS) samples, which are not capable of effectively amplifying and sequencing viral genetic material at lower viral load levels

2.2.1.1. Algorithm for Selecting PLWH for Genotyping Testing

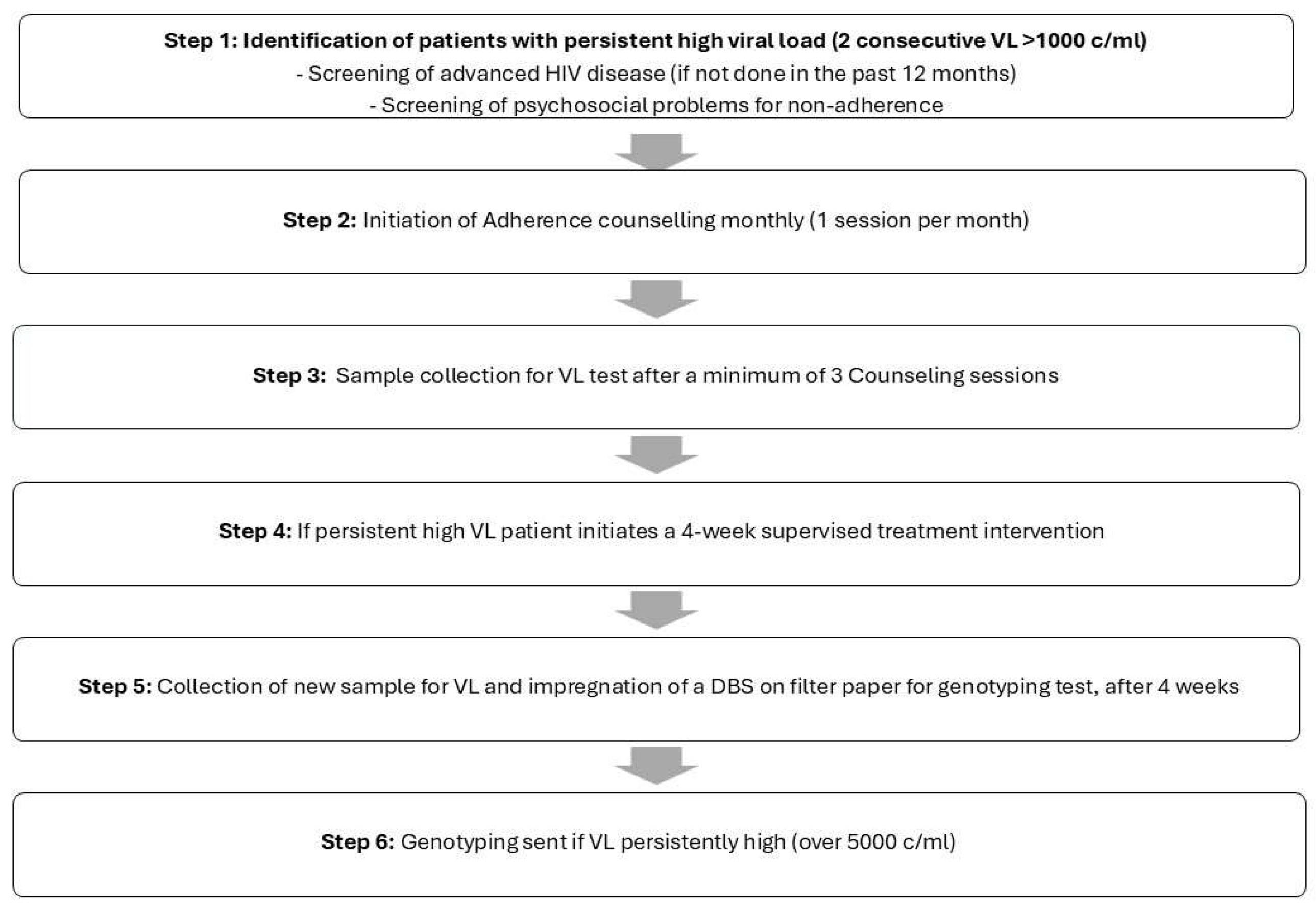

PLWH were referred to CRAM with persistent high viral loads and were managed according to the outlined algorithmic steps (

Figure 1):

Once PLWH were selected for this intervention, monthly adherence counseling sessions were conducted by senior lay counselors, coinciding with clinical consultations by a physician. A minimum of three sessions were provided prior to viral load (VL) re-evaluation. If VL remained elevated, a four-week supervised antiretroviral therapy (ART) period was initiated. This involved daily communication via phone call or text message from the patient to confirm adherence to treatment. During this period, PLWH were required to report daily on their treatment compliance. Following this intervention, all PLWH provided a blood sample for two purposes: to conduct a new VL test and to collect a dried blood spot sample on filter paper for storage. A genotyping test was performed if VL remained elevated, typically when it exceeded 5,000 copies/ml.

2.2.1.2. Genotyping HIVDR Testing

Four milliliters of whole blood samples were collected by venipuncture in a K2 EDTA tube. Resistance Genotyping was done on dried blood spots (DBS) using 50μL of venous blood per spot and dried overnight, samples were stored at -20ºC for <1 month before being shipped to the virology laboratory (Hôpitaux Universitaires de Genève) [

10].

DBS fragments were cut and subjected to elution for the release of viral RNA. During the amplification and sequencing phase, the Nested/Seminested RT-PCR technique was used. The amplified product was sequenced using the Sanger method, to identify mutations that may be associated with resistance [

11].

The Stanford HIVdb algorithm was used to interpret the results of the genotypic tests [

6]. Resistance scores (-R) for tenofovir (TDF), zidovudine (AZT), atazanavir (ATV) and dolutegravir (DTG) are reported. In addition, we present a composite class-related nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) resistance score calculated by averaging the TDF-R and AZT-R scores (where one of the scores was not available, the NRTI-R score was imputed as the other available score) [

12].

The Stanford HIVdb algorithm was used to interpret the results of the genotypic tests [

13]. Resistance scores (-R) for tenofovir (TDF), zidovudine (AZT), atazanavir (ATV) and dolutegravir (DTG) are reported. In addition, we present a composite class-related nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) resistance score calculated by averaging the TDF-R and AZT-R scores (where one of the scores was not available, the NRTI-R score was imputed as the other available score) [

14].

2.2.1.3. Program Evaluation Variables

We defined the Major dolutegravir resistance mutations (DTG-R) as those that can cause at least intermediate resistance to DTG when they occur in isolation [

12]. These mutations are G118R, Q148K/R and R263K for the purposes of this analysis. Non-major mutations are all other mutations (i.e. accessory or Major mutations related to INSTI, but which do not cause resistance or cause only low-level resistance to DTG when they arise alone) [

12].

2.2.2. Sampling and Sample Size of Program Participants

The sample will encompass the entire population of non-naive PLWH on ART who have experienced Virological Failure and have undergone HIV-1 genotyping, as recorded in the HIV-1 genotyping test registration book at CRAM, in accordance with the specified eligibility criteria. Consequently, no sampling calculation criteria are applicable.

2.2.3. Program Data Collection

The study team extracted routine clinical data from paper-based patient files, during the period under analysis, between the years 2020 and 2024. Exposure variables were categorized into four fields: (1) date of ART initiation and HIV-GT collection; (2) demographic profile: gender and age; (3) ART drug combination: NRTI-nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (D4T–Stavudine, ABC-Abacavir, AZT-Zidovudine, TDF-Tenofovir) Plus PIs-protease inhibitors (LPV-Lopinavir, RTV-Ritonavir, ATV-Atazanavir, DRV-Darunavir); or NRTI plus INSTI-integrase strand transfer inhibitor (DTG-Dolutegravir, RAL-Raltegravir); (4) Previous and most recent viral load; (5) Major HIV-1 drug resistance mutations described by their categories: NRTI, PI and INSTI; (6) most recent CD4 T lymphocyte count.

Data collected from eligible PLWH were anonymized to remove identifying details: each patient was given an alphanumeric code, and the anonymized data were included in the data sheet. Spreadsheet data were exported to SPSS for further data analysis

2.2.4. Program Data Analysis

All analyses were carried out in R (version 4.4.1). The Bayesian bootstrap implementation was performed using the bayesboot package (version 0.2.2).

We used medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) to describe continuous or count (discrete) variables, as well as proportions (%) to summarize categorical data. Our choice of Bayesian methods over frequentist approaches is motivated by their ability to quantify parameter uncertainty, particularly under smaller sample sizes reflective of real-world programmatic conditions. To further avoid parametric assumptions, we employ nonparametric bootstrapping for distribution assessment. The underlying assumption is that this cohort represents the population of PLWH with virological failure in the treatment failure program at CRAM.

To report uncertainty, we used the highest density interval for the 95% Bayesian credible interval (95% CrI). For the prior distribution of weights in the bootstrap algorithm, a non-informative uniform Dirichlet distribution was used. For proportions, a non-informative Jeffrey’s prior beta (0.5, 0.5) was applied.

Also, to determine the existence of an effect, we calculated the probability of direction (pd), which is the probability that the posterior distribution goes in the direction of the mean effect (positive or negative for differences, or above or below 1 for ratios) (Makowski et al. 2019). Regarding the existence of effect, the pd was interpreted as follows: pd ≤ 95%, uncertain effect; 95% < pd ≤ 97.5%, possibly existing; 97.5% < pd ≤ 99%, likely existing; pd > 99%, probably/certainly existing.

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Description

Among 106 samples successfully sequenced, 99 (93%) were subtype C; 62 (58.5%) were on a DTG-based regimen; 57 (53.8%) were female; 80 (75.5%) were receiving a TDF-based backbone; and 72 (67.9%) had advanced HIV disease (CD4 count lower than 200). (

Table 1)

All cases were from PLWH having persistent high viral load (virological failure). The average time on ART for the cohort was 11.6 years (IQR 9.1-14.4). The average time on the current ART regime was 3.1 years (IQR 2.2-4.5). (

Table 1)

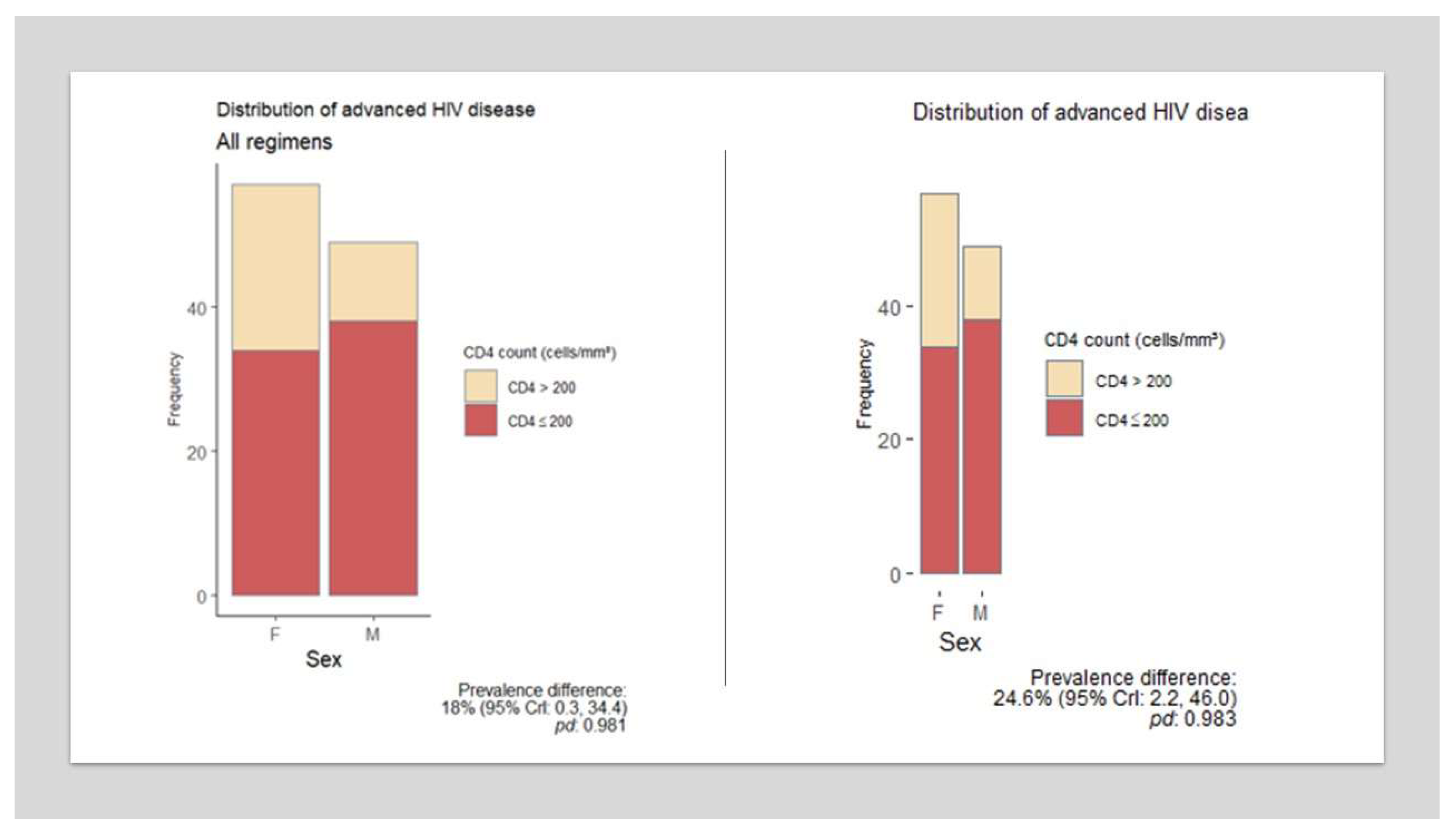

A difference in immunological status was observed between female and male PLWH in this cohort. Men exhibited a lower mean CD4 count and a higher proportion of advanced HIV disease, with high probability in both instances (prevalence difference 24.6%; 95% CrI 2.2-46). (

Figure 2).

3.2. INSTI Mutations and Resistance

Fifty-seven (92%) of the 62 samples from PLWH on a DTG-based regimen were sequenced, and 51 (89.5% [95% CrI: 80.7, 96.2]) had confirmed resistance to DTG; the mean DTG-R score was 70.2 (95% CrI: 62.2, 78). PLWH with DTG-R had a median of 3 INSTI mutations (IQR 1-4). (

Table 2)

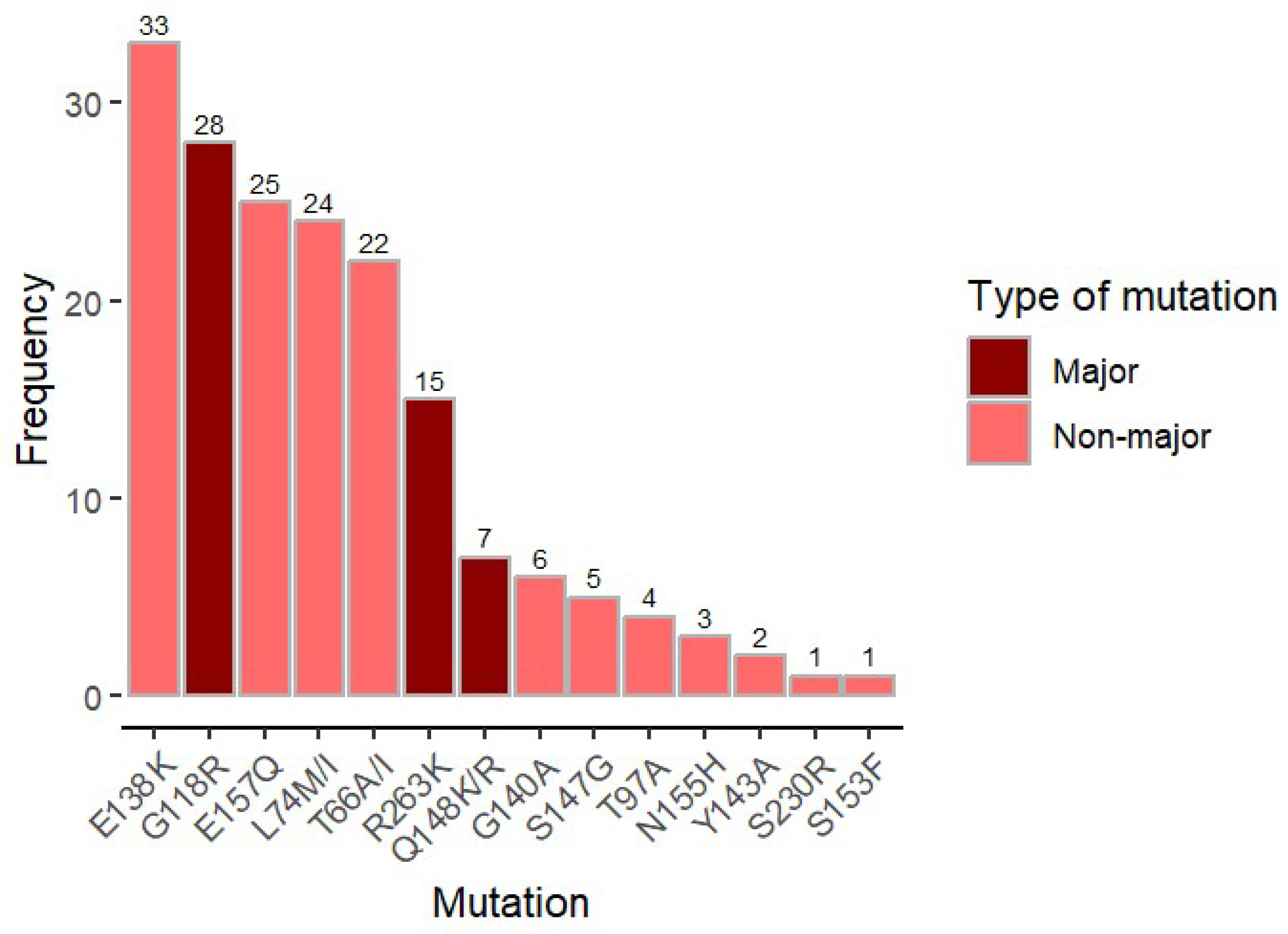

Major DTG-associated mutations were found in 46 out of 57 samples (80,7%); G118R (n = 28), R263K (n=15), and Q148RK (n=7). However, the most frequent mutation found was E138K (n=33), a non-major mutation that confers low level resistance when present isolated. (

Figure 3)

The mean relative DTG-R score (the DTG-R score standardized by total number of INSTI mutations) was 20.6 (95% CrI: 19, 22.2). The relative DTG-R score was positively correlated with the number of major mutations (bootstrapped Pearson’s correlation coefficient,

r: 0.61 [95% CrI: 0.42, 0.77;

pd: 100%]). We found a high resistance level to NRTI in our cohort. The median NRTI mutations in the global cohort was 3 (IQR 2-5), with a median of 4 (2-5) mutations in the DTG group, compared to 3 (2-5) mutations in the PI group. (

Table 2)

We didn’t find any INSTI resistance mutation in PLWH on the PI group (n=44). None of them had received treatment with INSTI before, so we assume we didn’t find primary resistance to DTG in our cohort. (

Table 2)

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

In this programmatic HIV-GT intervention, DTG-R was consistently found in highly ART exposed persons experiencing VF, after going through a structured adherence algorithm that included a short, supervised treatment intervention.

In our cohort, 51 cases of DTG resistance were detected among 57 PLWH resulting in a resistance rate of 89.5% in individuals experiencing confirmed virological failure. This finding indicates a high yield of resistance within our cohort, particularly when compared to other studies. DTG resistance surpassed the 19.6% (36/183) reported in a 2021–2022 Mozambique clinic-based study of experienced individuals transitioning to DTG across seven high-volume sites [

12]. Our analysis found higher DTG resistance than the 26.9% (24/89) reported in a Malawian retrospective cohort [

15] and likewise exceeded the 5.8% (4/84) INSTI resistance observed in Tanzania’s 2020 national HIV drug resistance survey [

16].

The results of this tightly controlled cohort of PLWH underscore the critical need for the implementation of high-quality, evidence-based adherence interventions, complemented by access to drug resistance testing for effective clinical management, in the sub-group of people particularly among individuals heavily exposed to ART.

Our algorithm demonstrated a notably high positive predictive value to find resistance (over 89%), among individuals with significant exposure to ART. This approach allowed the strategic allocation of resistance testing resources to PLWH with increased probability of carrying resistance mutations enabling customized decision-making concerning the subsequent individualized treatment options.

In our cohort, the analysis of the mutational patterns indicates that the predominant mutation linked to DTG is E138K, which was identified in 33 out of 51 samples, representing 65% of the cases. This mutation is categorized as a non-major mutation, associated with low-level resistance to DTG when it occurs in isolation. The most frequently observed major mutation associated with DTG is G118R, detected in 28 out of 51 samples, accounting for 55%. The second most prevalent major mutation is R263K, found in 15 out of 51 samples, which corresponds to 29%. Furthermore, the third most common major mutation is E148K, identified in 7 out of 51 samples, constituting 14%. When comparing various mutational patterns identified in previous studies and cohort analyses, no significant differences emerge. The RESIST study, which evaluated genotypic resistance test results of PLWH undergoing DTG regimens from 2013 to 2021 (n=599; INSTI drug resistance mutations detected in 86 PLWH, representing 14%), revealed a lower level of resistance alongside a distinct mutational pattern. The most prevalent Major-DTG associated mutation was R263K, identified in 10 out of 36 samples (28%). The second most frequent Major-DTG associated mutation was E138K, found in 7 out of 36 samples (19%), while the third most common Major mutation was E148K, present in 6 out of 36 samples (17%). Notably, only 3 out of 36 PLWH (8%) exhibited the G118K mutation, which is recognized as the Major mutation with the most significant impact on susceptibility to dolutegravir [

17].

Our cohort showed 67% of samples with high-level DTG resistance (Stanford score ≥60), compared to 17% in the RESIST study. Conversely, 6% of our samples had low-level resistance (Stanford score <15), versus 36% in the RESIST study [

17]. The observed differences may reflect varying stages in resistance development. While the RESIST study cohort, largely from settings with prompt genotyping access, included only 9 (2%) DTG-resistant samples from Africa [

17], the CRAM cohort had prolonged exposure to suboptimal DTG regimens prior to testing. This likely explains the higher resistance levels and greater prevalence of major DTG mutations in our cohort. In the cohort of PLWH undergoing a protease inhibitor-based regimen, there was no recorded prior exposure to dolutegravir (DTG). Consequently, we can conclude that primary resistance to integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs) was not identified, despite the extended duration of antiretroviral therapy (ART

4.2. Other Relevant Findings

Extended resistance to other ART classes was observed, showing a high prevalence of NRTI resistance in the cohort (median composite score for NRTI resistance over 5), and particularly in the DTG subgroup.

Men in our cohort had lower mean CD4 counts and a higher proportion of advanced HIV disease (AHD) than women. This aligns with findings that 31% of men starting ART in Mozambique had AHD, compared to 21% of women [

15]. CRAM’s focus on AHD and ART failure may explain the higher male representation, contrasting with the feminized HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa, where women comprise over 57% of PLWH [

16]. Other reports also indicate higher AHD prevalence in men [

18].

4.3. Limitations of the Study

Due to the necessity of transporting materials to outside Mozambique, we used DBS technology to facilitate the collection, preservation, and transport of samples. While this technology offers certain advantages, it also presents limitations, particularly in its sensitivity to detect mutations in samples exhibiting lower-level viremia. Consequently, PLWH with a viral load below 5000 copies/ml following the intervention were typically excluded from resistance testing. Utilizing plasma samples would likely have allowed for the inclusion of a greater number of PLWH in the testing strategy, thereby enhancing its overall success.

Due to the clinical focus of this intervention, designed to enhance tailored decision-making, exceptions allowed genotyping for three PLWH with viral loads below the standard threshold (1750, 3410, and 4800 copies/ml). Only the sample with 4800 copies/ml was successfully amplified and sequenced, highlighting challenges with genotyping DBS in lower-level viremia and reduced amplification success. By requiring a minimum of 24 months of ART exposure, we may have excluded some PLWH deemed unlikely to develop resistance. Most unsuppressed PLWH on first-line DTG achieved viral suppression through adherence reinforcement standardized in national protocols.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

In a context with scarce access to genotyping testing capacity, we strongly recommend the introduction of algorithms designed to identify PLWH at high risk of developing resistance. Our algorithm includes adherence reinforcement strategies already recommended in national policies, followed by an additional short, supervised ART support strategy. This approach has demonstrated a very high predictive capacity to identify PLWH with resistant mutations to DTG. Importantly, this allows for the avoidance of regimen switches in PLWH for whom the highly effective DTG regimen can still achieve viral suppression.

Because the positive predictive value of a test, to identify a particular event (in this case, the existence of resistance) is partly related to the prevalence of this event, it is uncertain how this algorithm may perform in PLWH in which resistance is less probable, as is the case of those using DTG as a first line or with shorter time of exposure to ART. Further assessment of this algorithm in distinct subpopulations is warranted. If feasible, plasma-based testing should be considered, to improve detection of resistance.

5.1. What the Bullet Points of this Study?

High Prevalence of Dolutegravir Resistance: The study reveals a strikingly high prevalence of dolutegravir (DTG) resistance (89.5%) among individuals with virologic failure (VF) who had extensive exposure to antiretroviral therapy (ART). This underscores the risk of resistance in heavily ART-experienced populations and challenges the assumption that DTG resistance is rare.

Effective Algorithm for Resistance Identification: The study introduces a structured algorithm combining adherence reinforcement, supervised ART support, and viral load monitoring to identify individuals at high risk of resistance. This approach demonstrated a high positive predictive value (89.5%), enabling targeted use of genotypic resistance testing where resources are limited.

Mutational Patterns and Resistance Scores: The study documents the most common DTG-associated mutations (e.g., G118R, R263K, Q148RK) and provides detailed resistance scores, offering insights into the genetic basis of DTG resistance in this cohort. The correlation between the number of major mutations and resistance scores further elucidates the mechanisms of resistance development.

Programmatic Implications: The findings highlight the need for integrating resistance testing into ART programs in resource-limited settings, particularly for individuals with prolonged ART exposure and virologic failure. The study advocates for adherence support and supervised interventions before considering regimen switches, which can help preserve effective treatment options like DTG.

Sex Disparities in Advanced HIV Disease: The study notes significant immunological differences between men and women in the cohort, with men exhibiting lower CD4 counts and higher rates of advanced HIV disease. This aligns with broader trends in sub-Saharan Africa and emphasizes the need for targeted interventions for male populations.

Limitations and Future Directions: The study acknowledges the challenges of using dried blood spot (DBS) samples for genotyping, particularly their lower sensitivity for detecting resistance in cases of low-level viremia. It calls for further research to validate the algorithm in different subpopulations and to explore plasma-based testing for improved sensitivity

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

MR & AF, equally contributed to the study design, data acquisition, study implementation, analysis and implementation of data, and major contributions to writing. They also read and approved the final version. AC, IG, AG contributed equally to study implementation, writing, reading and approved final version. RB, AM, SY & HM, contributed to data acquisition, and read and approved final version. JL, FM & EN equally contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, reviewing, writing, reading and approved the final version.

Funding

This work results from a collaborative among MSF, I-TECH and the Mozambican MoH. I-TECH was the responsible for the clinical management of PLWH, including, diagnose, lab results interpretation, and clinical follow up. MSF funded the HIV Genotyping test and hosted the genotyping dataset. Data analysis and manuscript writing was conducted through an equal collaboration between I-TECH, MSF and the MoH. The I-TECH Mozambique clinical work at the facility (CRAM) was funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) – HRSA (U91HA0680112) and CDC (NU2GGH002374). The content and conclusions presented herein are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing official statements or policies. Consequently, no endorsement by MSF, HRSA, CDC, HHS, or the U.S. Government should be inferred.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Gaza Institutional Bioethics Committee for Health (IRB0002657 – Comité Institucional de Bioética para a Saúde de Gaza, nr: 181/CIBS-Gaza/2023) and permission to perform this evaluation was also obtained from the National Directorate of Public Health from Mozambican Ministry of Health (Direção Nacional de Saúde Publica, N/Ref. no. 224/2103/DNSP/2020). Because this analysis only involved assessment of routine administrative data collected for programmatic purposes, this analysis is considered Non-Research from the University of Washington. This evaluation fulfilled the exemption criteria set by the Médecins Sans Frontières Ethics Review Board for a posteriori analyzes of routinely-collected clinical data and thus did not require MSF ERB review.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent to participate in the routine program was waived by IRB because we performed analysis on routine administrative data. All information obtained during the analysis was kept confidential. Analysis was performed on de-identified aggregated data. Furthermore, this analysis was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets utilized in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request; however, they are not publicly accessible due to privacy constraints.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author’s contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any agency to which they are affiliated.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABC |

Abacavir, |

| AHD |

Advanced HIV Disease |

| ART |

Antiretroviral therapy |

| ATV |

Atazanavir |

| AZT |

Zidovudine |

| CRAM: |

Centro de Referência de Alto-Mae |

| CDC |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| D4T |

Stavudine |

| DBS |

Dried blood spot |

| DRV |

Darunavir |

| DTG |

Dolutegravir |

| DTG-R |

Dolutegravir resistance testing |

| HRSA |

Health Resources and Services Administration |

| HIV-GT |

HIV genotypic resistance testing |

| IQR |

Interquartile range |

| INSTI |

Integrase strand transfer inhibitor |

| ITECH |

International Training and Education Center for Health |

| pd |

Probability of direction (pd), |

| PIs |

Protease inhibitors |

| PLWH |

People living with HIV |

| LPV |

Lopinavir |

| MSF |

Médecins Sans Frontières |

| NRTI |

Nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors |

| RTV |

Ritonavir |

| RAL |

Raltegravir |

| TDF |

Tenofovir) Plus |

| VF |

Virologic failure |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| 95% Crl |

95% Bayesian credible interval |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO), “WHO recommends dolutegravir as preferred HIV treatment option in all populations,” World Health Organization (WHO). Accessed: Nov. 20, 2024. [Online]. https://www.who.int/news/item/22-07-2019-who-recommends-dolutegravir-as-preferred-hiv-treatment-option-in-all-populations.

- Borry, P.; Bentzen, H.B.; Budin-Ljøsne, I.; Cornel, M.C.; Howard, H.C.; Feeney, O.; Jackson, L.; Mascalzoni, D.; Mendes, Á.; Peterlin, B.; et al. The challenges of the expanded availability of genomic information: an agenda-setting paper. J. Community Genet. 2017, 9, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. de S. M. DNAM - Direcção Nacional de Assistência Médica, “COMITÉ TARV: MISAU, Mozambique,” Ministério da Saúde de Moçambique. Accessed: Apr. 20, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://comitetarvmisau.co.mz/.

- Nacarapa, E.; Verdu, M.E.; Nacarapa, J.; Macuacua, A.; Chongo, B.; Osorio, D.; Munyangaju, I.; Mugabe, D.; Paredes, R.; Chamarro, A.; et al. Predictors of attrition among adults in a rural HIV clinic in southern Mozambique: 18-year retrospective study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, “I-TECH Supported Reference Center Serves as Critical Lifeline for People with Advanced HIV Disease,” I-TECH, University of Washington - Global Health department. Accessed: Feb. 24, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.go2itech.org/2023/02/i-tech-supported-reference-center-serves-as-critical-lifeline-for-people-with-advanced-hiv-disease/.

- C. INS, “INSIDA 2021: Divulgados Resultados do Inquérito sobre o Impacto do HIV e SIDA em Moçambique.” Accessed: Jun. 01, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://ins.gov.mz/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/53059_14_INSIDA_Summary-sheet_POR.

- SISMA - MoH Mozambique, “O Sistema de Informação de Saúde para Monitoria e Avaliação (SIS-MA),” SISMA - Ministério da Saúde. Accessed: Feb. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://sisma.misau.gov.mz/.

- TECH, “ I-TECH International Training and Education Center for Health, Mozambique Partnerships.” Accessed: Apr. 20, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.go2itech.org/2017/08/mozambique-partnerships/.

- ITECH Mozambique 2017, “Annual progress report narrative COP16,” Sep. 2017. Accessed: Sep. 08, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.go2itech.

- Reust, M.J.; Lee, M.H.; Xiang, J.; Zhang, W.; Xu, D.; Batson, T.; Zhang, T.; Downs, J.A.; Dupnik, K.M. Dried Blood Spot RNA Transcriptomes Correlate with Transcriptomes Derived from Whole Blood RNA. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 98, 1541–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crossley, B.M.; Bai, J.; Glaser, A.; Maes, R.; Porter, E.; Killian, M.L.; Clement, T.; Toohey-Kurth, K. Guidelines for Sanger sequencing and molecular assay monitoring. J. Veter- Diagn. Investig. 2020, 32, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanford University, “STANFORD HIVDB ALGORITHM UPDATES.” Accessed: , 2023. [Online]. Available: https://hivdb.stanford.edu/page/algorithm-updates/#version.9.4.update. 06 May 2022.

- Stanford University, “STANFORD HIVDB ALGORITHM UPDATES.” Accessed: , 2023. [Online]. Available: https://hivdb.stanford.edu/page/algorithm-updates/#version.9.4.update. 06 May 2022.

- Stanford database HIV Drug Resistance Database, “REGA HIV-1 Subtyping Tool.” Accessed: Sep. 08, 2022. [Online]. Available: http://dbpartners.stanford.edu:8080/RegaSubtyping/stanford-hiv/typingtool/.

- Kanise, H.; van Oosterhout, J.J.; Bisani, P.; Songo, J.; Matola, B.W.; Chipungu, C.; Simon, K.; Cox, C.; Hosseinipour, M.C.; Sagno, J.-B.; et al. Virological Findings and Treatment Outcomes of Cases That Developed Dolutegravir Resistance in Malawi’s National HIV Treatment Program. Viruses 2023, 16, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamori, D.; Barabona, G.; Rugemalila, J.; Maokola, W.; Masoud, S.S.; Mizinduko, M.; Sabasaba, A.; Ruhago, G.; Sambu, V.; Mushi, J.; et al. Emerging integrase strand transfer inhibitor drug resistance mutations among children and adults on ART in Tanzania: findings from a national representative HIV drug resistance survey. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2023, 78, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loosli, T.; Hossmann, S.; Ingle, S.M.; Okhai, H.; Kusejko, K.; Mouton, J.; Bellecave, P.; van Sighem, A.; Stecher, M.; Monforte, A.D.; et al. HIV-1 drug resistance in people on dolutegravir-based antiretroviral therapy: a collaborative cohort analysis. Lancet HIV 2023, 10, e733–e741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitenge, M.K.; Fatti, G.; Eshun-Wilson, I.; Aluko, O.; Nyasulu, P. Prevalence and trends of advanced HIV disease among antiretroviral therapy-naïve and antiretroviral therapy-experienced patients in South Africa between 2010-2021: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).