1. Introduction

People living with human immunodeficiency virus (PWH) currently require lifelong antiretroviral therapy (ART), which has significantly improved life expectancy. As a result, HIV infection is now considered one of the communicable chronic diseases. The 2023 guidelines from the US Department of Health and Human Services, the 2023 European AIDS Clinical Society, and the 2022 International Antiviral Society–USA recommend the use of second-generation integrase strand transfer inhibitors as initial antiretroviral regimens. Examples include bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide fumarate (BIC/FTC/TAF) and dolutegravir/lamivudine (DTG/3TC) for most treatment-naive individuals with HIV and as a switch option for those who are virologically suppressed [

1,

2,

3]. These recommendations are based on the demonstrated potent, durable antiviral activity and a high barrier to resistance of these medications.

Several studies have demonstrated the suppressive efficacy of a two-drug regimen comprising DTG plus 3TC. Notably, its suppressive efficacy is comparable to that of three-drug regimens. In the GEMINI trial, DTG plus 3TC and DTG plus FTC/TAF exhibited similar efficacy, irrespective of the baseline viral load [

4]. Additionally, the TANGO and SALSA clinical trials revealed that DTG/3TC maintained virological suppression similarly to a tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) or tenofovir alafenamide (TAF)-based three-drug regimen [

5,

6,

7]. Real-world cohort studies have further supported these findings, indicating a similar effectiveness and safety profile, including adverse events leading to discontinuation, in virologically suppressed individuals with HIV who switched to DTG/3TC or BIC/FTC/TAF [

8,

9,

10].

Most studies on DTG/3TC and BIC/FTC/TAF have been clinical trials primarily focused on Europe and North America, with limited representation from real-world studies in Asia. Furthermore, these studies predominantly included treatment-naïve or virologically suppressed patients, and there has been a scarcity of research analyzing the risk factors for virological failure and the impact of pre-existing resistance-associated mutations among antiretroviral therapy (ART)-experienced and viremic individuals living with HIV. Therefore, the primary objective of this study is to investigate the effectiveness, safety profiles, and adverse effects of switching to DTG/3TC and BIC/FTC/TAF in Asian ART-experienced patients. Additionally, the study aims to identify the risk factors associated with detectable viral loads after a 48-week period.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective, observational cohort study was conducted at a designated hospital for HIV care in Taiwan. The study was conducted from March 2019 to January 2023 and included treatment-experienced adults living with HIV who switched from a regimen comprising two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) plus an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI), nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), or protease inhibitor (PI) to coformulated DTG/3TC or BIC/FTC/TAF as maintenance treatment. Patients with specific conditions, such as HIV/HBV co-infection taking DTG/3TC, those with active tuberculosis, were excluded. All included patients were followed for a 48-week period.

The primary endpoint was the proportion of participants who achieved undetectable plasma HIV RNA (<50 copies/mL) at week 48 after switching to DTG/3TC or BIC/FTC/TAF, evaluated in a snapshot, per-protocol-exposed population. Secondary endpoints included changes in body weight, total cholesterol, and triglyceride levels over the course of the study. The study received approval from the research ethics committee or institutional review board (registration number: TYGH112029), and patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. All data were analyzed without personal sensitive information.

2.1. Data collection and definition

A standardized case record form was utilized to gather information on demographics, sexual preference, body weight, HIV treatment history, HIV regimens prior to the switch, reasons for switching, HBsAg serology, and results of various laboratory investigations. The tests included plasma HIV RNA, CD4 lymphocyte count, serum creatinine, liver function, lipid profile, and fasting blood glucose or glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C). These tests were conducted every 3–6 months in adherence to the CDC HIV treatment guidelines in Taiwan.

Plasma HIV RNA was measured using the COBAS AmpliPrep TaqMan HIV-1 test version 2.0 (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), with a lower limit of quantitation of fewer than 20 copies/mL. An HIV status considered under control was defined as HIV RNA below 50 copies/mL, while virologic failure was defined as a plasma HIV RNA exceeding 1,000 copies/mL. Low-level viremia was characterized by HIV RNA between 50 to 1,000 copies/mL occurring more than twice consecutively in the previous year before the switch.

Resistance-associated mutations (RAMs) were identified through population sequencing of HIV-1 RNA, and resistance was predicted using the HIVdb program of the Stanford University HIV Drug Resistance Database, aligning with the drug resistance mutation list of the international AIDS Society-USA Consensus Guidelines [

11].

2.2. Statistical analysis

The distributions of patients' demographics and baseline characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. Categorical variables were compared using either the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, while continuous variables were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test. In the case of paired data, the McNemar test was employed for categorical variables, and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for continuous variables.

2.3. Analysis and regression models

A linear regression model was employed to examine the association between changes in weight and lipids, while a logistic regression model was used to assess the risk factors associated with detectable HIV viral loads at week 48. All p values were two-sided, and statistical significance was set at a p value <0.05. The analyses were conducted using SPSS software version 24.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

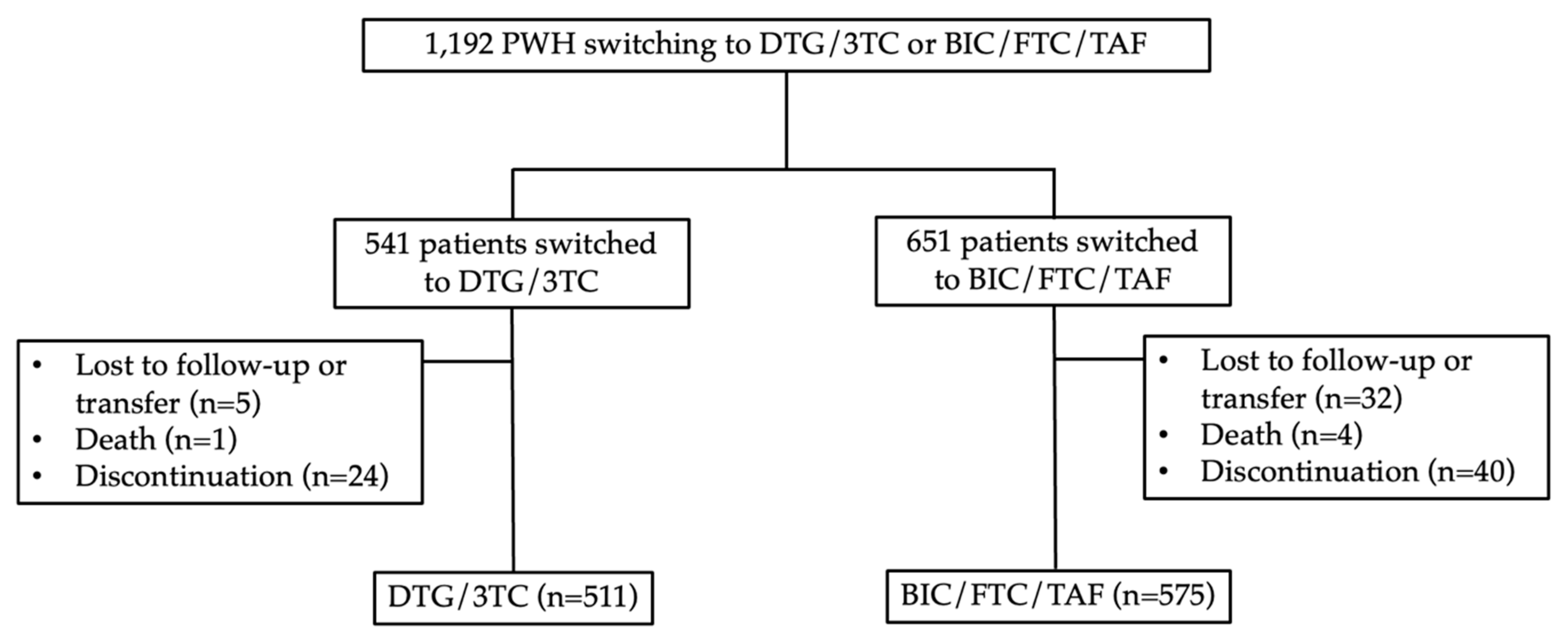

Between October 2019 and January 2023, a total of 1,192 PWH were screened. Out of these, 651 individuals switched their antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimen to BIC/FTC/TAF, while 541 switched to DTG/3TC. In the BIC/FTC/TAF group, 40 PWH discontinued BIC/FTC/TAF due to adverse events or virologic failure, 4 patients passed away for reasons unrelated to drug-related issues, and 32 patients were lost to follow-up (not related to efficacy issues or intolerance). Ultimately, 615 PWH were included in the modified intention-to-treat (mITT) analysis after excluding those lost to follow-up, transferred to other clinics, or deceased. Additionally, 575 PWH were included in the per-protocol (PP) analysis. In the DTG/3TC group, 24 PWH discontinued ART, 1 patient passed away for non-drug related reasons, and 5 patients were lost to follow-up (unrelated to efficacy issues or intolerance). Finally, 535 PWH were included in the mITT analysis, and 511 PWH were included in the PP analysis. Refer to

Figure 1 for more detailed information.

In the BIC/FTC/TAF group, 95 patients (17%) tested positive for HBsAg, whereas none were observed in the DTG/3TC group (

p<0.01). The distribution of CD4 counts in the DTG/3TC group showed that 68% (346/511) had CD4 counts >500 cells/uL, and 2% (11/515) had CD4 counts <200 cells/uL. In comparison, the BIC/FTC/TAF group had 55% (314/575) with CD4 counts >500 cells/uL and 5% (27/575) with CD4 counts <200 cells/uL (

p<0.01). Among the included patients, 951 had undetectable viral loads (HIV RNA <50 copies/mL) before the switch, with 94% (483/511) in the DTG/3TC group and 81% (468/575) in the BIC/FTC/TAF group (

p<0.01). In the per-protocol population, 84% of patients had no record of virological failure (HIV RNA >1000 copies/mL), with a higher proportion in the DTG/3TC group (87%) compared to the BIC/FTC/TAF group (82%). Before the switch in the DTG/3TC group, DTG/3TC/ABC (72%) was the predominant ART regimen, while TAF/FTC/EVG/c (69%) was the main ART regimen in the BIC/FTC/TAF group (p<0.01). Baseline characteristics and differences between groups are summarized in

Table 1.

Pre-existing primary resistance-associated mutations (RAM) to any drug class were identified in 11.9% (61/511) of patients in the DTG/3TC group. These mutations included nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-resistance (NRTI-R) in 4%, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-resistance (NNRTI-R) in 7%, protease inhibitor-resistance (PI-R) in 1%, and integrase strand transfer inhibitor-resistance (INSTI-R) in 0.4%. Notably, one patient had K65R+M184V before the switch. In the BIC/FTC/TAF group, 13.7% (79/575) of patients had pre-existing RAM, consisting of NRTI-R in 7%, NNRTI-R in 7%, PI-R in 0.2%, and INSTI-R in 0.2%. Additionally, three patients had K65R+M184V/I, and one patient in the BIC/FTC/TAF group had Q148H+G140S before the switch (

Table 2).

3.2. Virological effectiveness

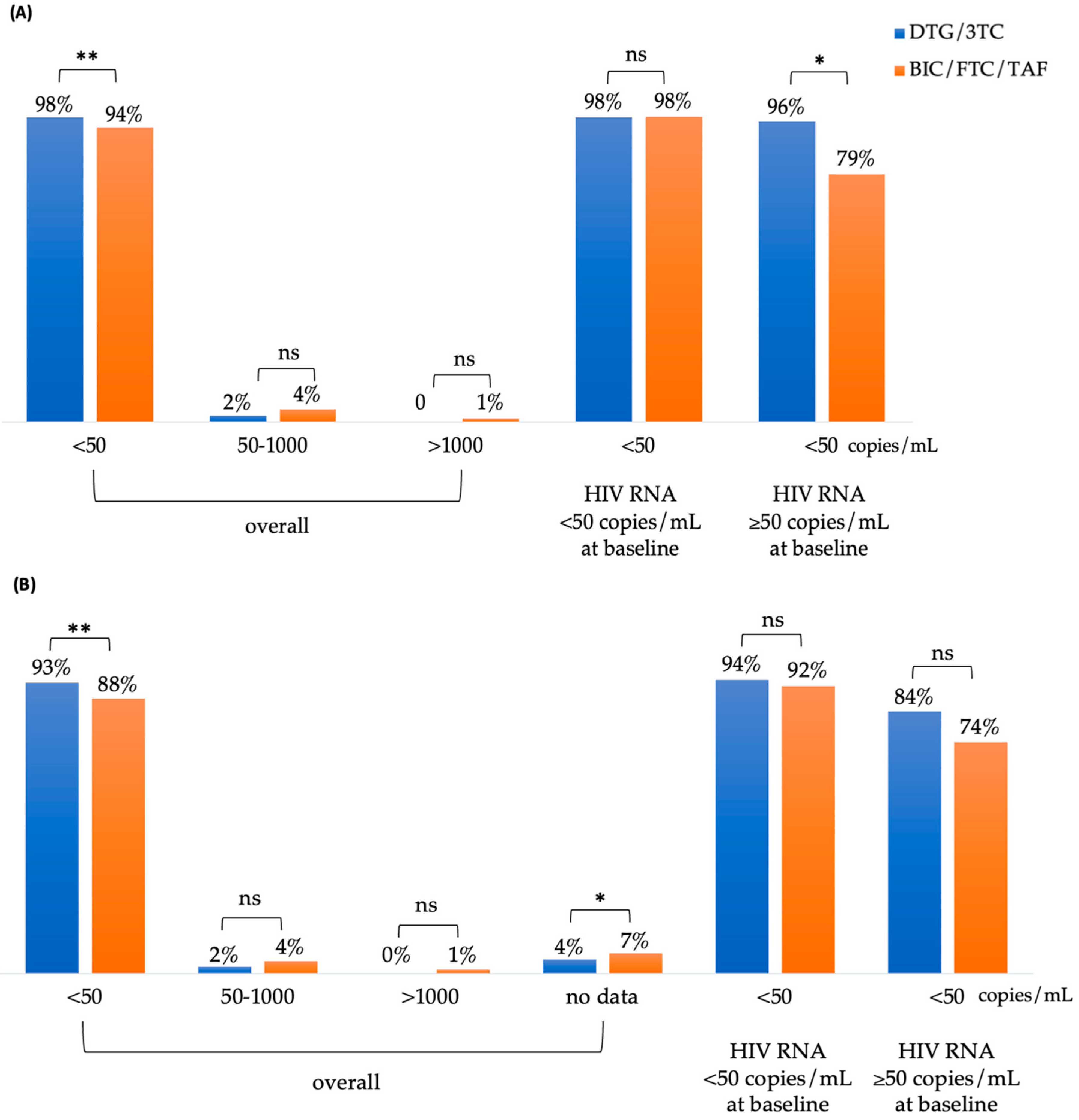

At week 48, 98% (499/511) of patients in the DTG/3TC group and 94% (543/575) in the BIC/FTC/TAF group achieved an HIV RNA of <50 copies/mL (

p <0.01) in the Snapshot, Per Protocol-Exposed (PP-E) population (

Figure 2A). Among patients with an HIV RNA of <50 copies/mL at baseline, the rates of undetectable plasma HIV RNA for the DTG/3TC and BIC/FTC/TAF cohorts were 98% (483/472) and 98% (458/468), respectively. For patients with an HIV RNA of ≥50 copies/mL at baseline, the rates of undetectable viral load for the DTG/3TC and BIC/FTC/TAF cohorts were 96% (27/28) and 79% (85/107), respectively (p = 0.03).

Figure 2B illustrates the results of the modified intention-to-treat (mITT) analysis, which were consistent with those of the PP analysis. At week 48, 93% (499/535) of patients in the DTG/3TC group and 88% (543/615) in the BIC/FTC/TAF group achieved an HIV RNA of <50 copies/mL (

p <0.01). Among participants with an HIV RNA of ≥50 copies/mL or <50 copies/mL at baseline, the rates of undetectable viral load did not differ significantly between the DTG/3TC and BIC/FTC/TAF groups. There were no significant differences in other parameters.

Among PWH switching to DTG/3TC or BIC/FTC/TAF who had pre-existing K65R with or without M184V/I before the switch, all 3 out of 3 (100%) and 4 out of 4 (100%), respectively, successfully achieved an HIV RNA of <50 copies/mL at week 48. It's worth noting that these 7 patients already achieved undetectable viral loads at baseline. Furthermore, among PWH switching to DTG/3TC or BIC/FTC/TAF with pre-existing M184V/I, 5 out of 6 (83.3%) and 18 out of 19 (94.7%) achieved HIV RNA levels of <50 copies/mL at week 48. In the DTG/3TC group, 2 patients with pre-existing Q148H before the switch, and in the BIC/FTC/TAF group, 1 patient with pre-existing Q148H along with G140S, all 3 out of 3 (100%) successfully achieved undetectable viral loads at week 48.

3.3. Risk factors of detectable viral loads at week 48 after switch

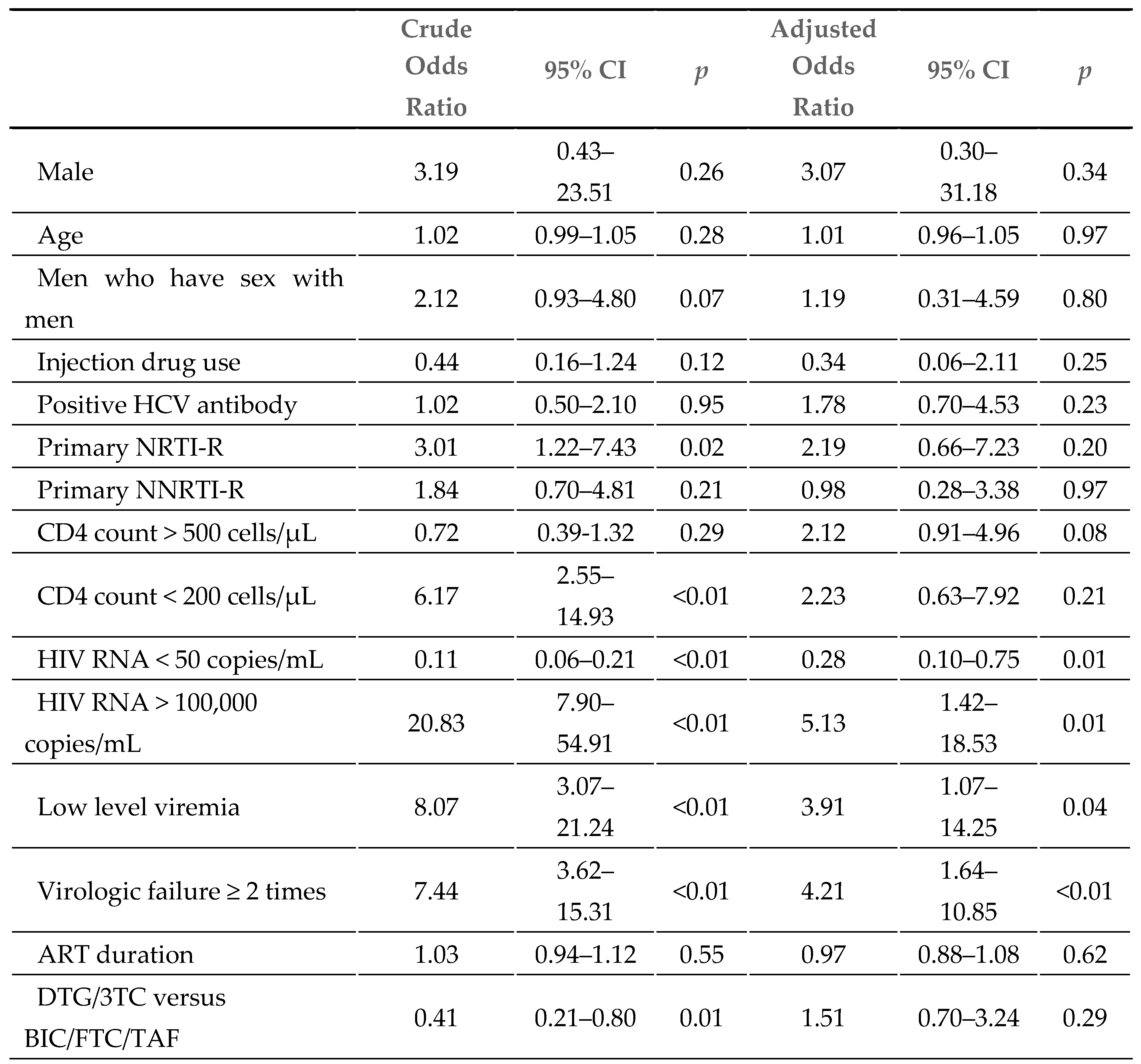

At week 48, 44 patients (4%) had detectable viral loads (HIV RNA >50 copies/mL). As shown in

Table 3, detectable viral loads were analyzed in a logistic regression model, and the following factors before the switch were considered: HIV RNA > 100,000 copies/mL (AOR 5.13, 95% CI 1.42–18.53), low-level viremia (AOR 3.91, 95% CI 1.07–14.25), and a record of virologic failure ≥ 2 times (AOR 4.21, 95% CI 1.64–10.85), while an HIV viral load <50 copies/mL before the switch (AOR: 0.28, 95% CI 0.10–0.75) was identified as a protective factor. After adjusting for baseline age, sex, route of transmission, primary RAM, CD4 cell counts, HIV RNA, low-level viremia, record of virologic failure, and ART duration, there were no significant differences between the DTG/3TC and BIC/FTC/TAF groups (AOR: 1.51, 95% CI 0.70–3.24).

3.4. Immunological response and clinical outcomes

The mean (standard deviation [SD]) change from baseline to week 48 in CD4 lymphocyte cell count was 63 cells/µL (± 221) in the DTG/3TC group and 54 cells/µL (± 206) in the BIC/FTC/TAF group (

p = 0.51).

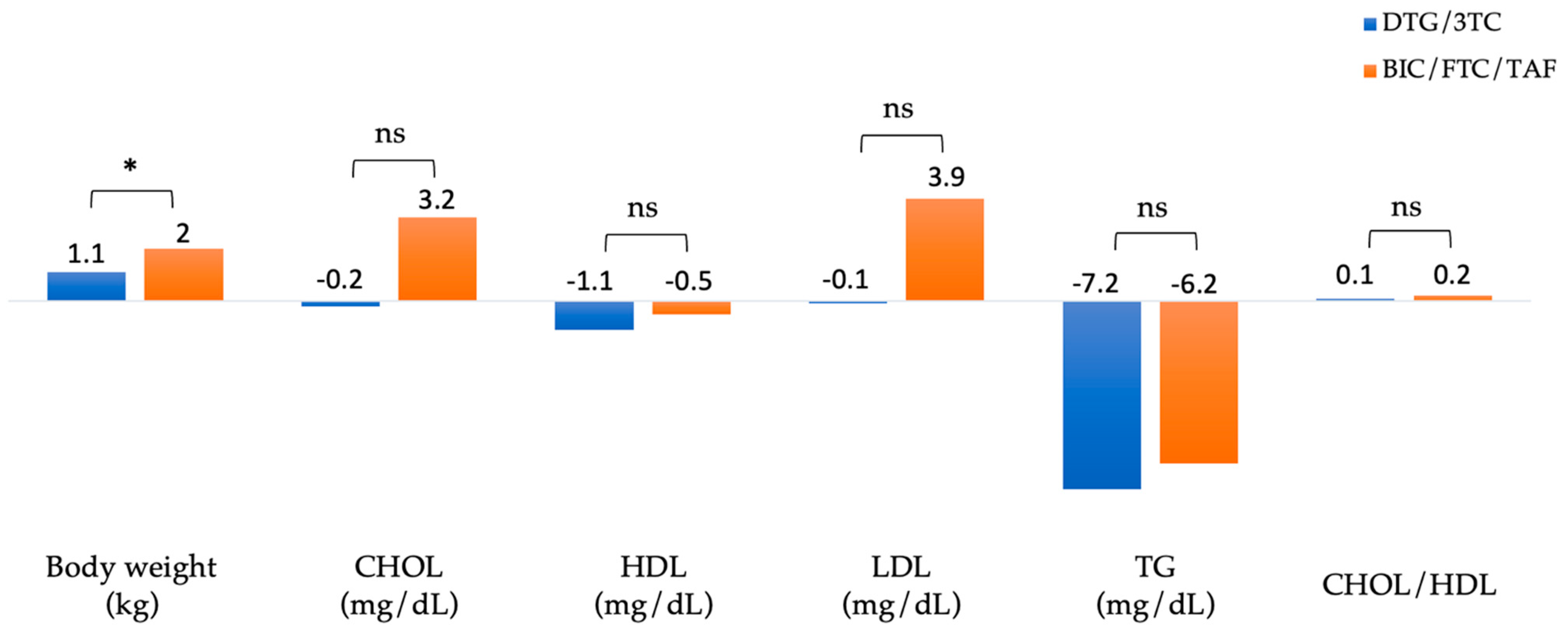

Figure 3 summarizes the changes in body weight and lipid profiles of patients after 48 weeks of switching to DTG/3TC and BIC/FTC/TAF. The absolute mean (SD) weight at baseline versus week 48 was 72.5 (± 13.8) vs. 73.5 (± 13.6) kg in the DTG/3TC group (n=210) and 70.7 (± 12.3) vs. 72.7 (± 12.9) kg in the BIC/FTC/TAF group (n=193), respectively. In the BIC/FTC/TAF group, body weight increased by 2 kg, and in the DTG/3TC group, body weight increased by 1.1 kg (adjusted difference, 0.9 kg; 95% CI, 0.4–1.4;

p = 0.04).

The absolute mean total cholesterol (CHOL) at baseline versus week 48 was 183.8 (± 32.2) vs. 183.6 (± 32.2) mg/dL in the DTG/3TC group (n=403) and 179.2 (± 34.7) vs. 182.4 (± 32.5) mg/dL in the BIC/FTC/TAF group (n=349). The absolute mean high-density lipoprotein (HDL) at baseline versus week 48 was 47.8 (± 12.5) vs. 46.7 (± 11.2) mg/dL in the DTG/3TC group (n=401) and 48 (± 13.9) vs. 47.5 (± 12.5) mg/dL in the BIC/FTC/TAF group (n=327). The absolute mean low-density lipoprotein (LDL) at baseline versus week 48 was 122.8 (± 30) vs. 122.7 (± 32) mg/dL in the DTG/3TC group (n=402) and 114.4 (± 30.7) vs. 118.4 (± 30.8) mg/dL in the BIC/FTC/TAF group (n=329). The absolute mean triglyceride (TG) at baseline versus week 48 was 141.9 (± 97) vs. 134.7 (± 112.6) mg/dL in the DTG/3TC group (n=402) and 151.3 (± 103) vs. 145.1 (± 129.4) mg/dL in the BIC/FTC/TAF group (n=347). The absolute mean CHOL/HDL ratio at baseline versus week 48 was 4.1 (± 1.1) vs. 4.2 (± 1.2) in the DTG/3TC group (n=377) and 3.9 (± 1) vs. 4.1 (± 1.3) in the BIC/FTC/TAF group (n=312), respectively. Blood lipid parameters did not differ substantially from baseline, including total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein, and triglyceride.

3.5. Adverse events and causes leading to discontinuation

Through week 48, the proportion of patients reporting drug-related adverse events or causes leading to discontinuation was 24 (4.4%) in the DTG/3TC group and 40 (6.1%) in the BIC/FTC/TAF group. The most common adverse events (AEs) in the DTG/3TC group were pruritus (0.9%), insomnia (0.7%), headache/dizziness (0.4%), increased weight (0.4%), and renal function deterioration (0.4%). The most common AEs leading to discontinuation in the BIC/FTC/TAF group were increased weight or obesity (1.2%), insomnia (0.6%), and low-level viremia (0.6%). Treatment discontinuation rates did not significantly differ between the two regimens (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

In this real-world study involving a switch to BIC/FTC/TAF or DTG/3TC in 1086 ART-experienced PWH, we observed high proportions of undetectable HIV RNA at week 48. However, the occurrence of HIV RNA greater than 50 copies/mL after the switch at week 48 was associated with HIV RNA greater than 100,000 copies/mL, low-level viremia, and a history of virologic failure more than 2 times before the switch. Furthermore, having undetectable HIV RNA before the switch was associated with a lower risk of HIV RNA greater than 50 copies/mL at week 48, even among PWH with pre-existing NRTI resistance. BIC/FTC/TAF and DTG/3TC are efficacious and well-tolerated integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI)-based regimens for both antiretroviral therapy (ART)-naïve [

6,

12,

13] and ART-experienced people living with HIV (PLWH) [

5,

7,

14,

15,

16,

17]. They are recommended as first-line ART options in several international HIV treatment.

TANGO and SALSA clinical trials revealed that DTG/3TC maintained virological suppression similarly to a tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) or tenofovir alafenamide (TAF)-based three-drug regimen. Our cohort also showed switching to DTG/3TC maintained similar virological suppression as switching to BIC/FTC/TAF at week 48. The proportion of undetectable HIV RNA was 98% (DTG/3TC) and 98% (BIC/FTC/TAF) in the subgroup of HIV RNA <50 copies/mL at baseline (Snapshot, PP-E population). Furthermore, regardless of HIV RNA viral loads at baseline, the proportion of undetectable HIV RNA using DTG/3TC or BIC/FTC/TAF for 48 weeks was 98% and 94% (p <0.01), respectively, and in the subgroup of HIV RNA ≥50 copies/mL at baseline, the proportions were 96% and 79% (p = 0.03), respectively.

While clinical trials may exhibit the weakness of lacking diversity, with enrolled participants not reflecting the demographics of the intended patient population, thereby limiting the interpretation of published outcomes, retrospective observational cohort studies face the weakness of selection bias. Participants in real-world studies may not be randomly assigned, leading to the potential for a disproportion between groups. This can affect the generalizability of the findings to the broader population [

18].

Therefore, we conducted a logistic regression model to identify the risk factors for detectable viral loads at week 48. The findings showed that HIV RNA > 100,000 copies/mL (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 5.13, 95% CI 1.42–18.53), low-level viremia (AOR 3.91, 95% CI 1.07–14.25), and a record of virologic failure ≥ 2 times (AOR 4.21, 95% CI 1.64–10.85) before the switch were the major risk factors. The adjusted odds ratio between the regimens of DTG/3TC and BIC/FTC/TAF (AOR: 1.51, 95% CI 0.70–3.24) is not significant. Moreover, among the 44 patients (4%) with detectable viral loads (HIV RNA >50 copies/mL) at week 48, no one was detected to have acquired drug resistance-associated mutations. The interval change from baseline in CD4 lymphocyte cell count was not significantly different between the DTG/3TC and BIC/FTC/TAF groups (63 vs. 54 cells/µL, p=0.51), and the finding was similar to TANGO and SALSA.

In our cohort, there is significant greater number of loss to follow-up PWH in BIC/FTC/TAF group (4.9%) comparing to DTG/3TC group (0.9%). This might be explained by the fact that PWH might have frequent lifestyle instability and suboptimal adherence in BIC/FTC/TAF group. Suboptimal adherence is associated with higher risk of low-level viremia and virologic failure. [

19,

20] Hence, we also noticed higher proportion of PWH with virologic failure and low-level viremia in BIC/FTC/TAF group. Therefore, PWH with lifestyle instability and suboptimal adherence could have motivated physicians to consider a potentially more robust and forgiving three-drug regimen.

Low-level viremia (LLV) with HIV RNA between 50 and 199 copies/mL could lead to subsequent virological failure (HIV RNA >1000 copies/mL) before the era of second-generation integrase strand transfer inhibitor-containing regimens as first-line ART [

21,

22,

23]. Chen GJ et al. showed that the risks of developing very low-level viremia (VLLV) or LLV were similarly low between PWH switched to bictegravir-based, dolutegravir-based regimens, and PI-based regimens [

24,

25]. The results were consistent with our study, which demonstrated that the incidence rate of developing LLV was 4.2 per 100 person-years of follow-up (PYFU) in the BIC/FTC/TAF group and 2.3 per 100 PYFU in the DTG/3TC group [incidence rate ratio (IRR) = 1.83;

p = 0.09].

Some studies confirmed that DTG/3TC and BIC/FTC/TAF were effective, regardless of the existence of the M184V mutation, among suppressed PWH. Andreatta K. et al revealed that at week 48, 98% (561/570) of all BIC/FTC/TAF-treated participants versus 98% (213/217) with pre-existing resistance and 96% (52/54) with archived M184V/I had HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/mL. No BIC/FTC/TAF-treated participants developed resistance-associated mutations (RAMs) to study drugs [

26]. Santoro MM. et al showed that the probability of virologic failure and blips in patients switching to DTG/3TC was very low (7.8% and 6.9%) after 3 years of treatment regardless of M184V [

27]. Our study found that among PWH switching to DTG/3TC or BIC/FTC/TAF who had pre-existing K65R with or without M184V/I before the switch, 7 out of 7 (100%) successfully achieved HIV RNA <50 copies/mL at week 48, and these 7 patients had undetectable viral loads at baseline. Furthermore, among PWH switching to DTG/3TC or BIC/FTC/TAF with pre-existing M184V/I, 5 out of 6 (83.3%) and 18 out of 19 (94.7%) achieved HIV RNA levels <50 copies/mL at week 48, but only 18 out of 25 (%) patients had undetectable viral loads before the switch. However, the effect of a short duration of previous virological suppression in patients with M184V/I on DTG/3TC or BIC/FTC/TAF response remains unclear. Therefore, a clinical trial that examines the duration of virological suppression before the switch is warranted.

The mean increase in body weight from baseline to week 48 was 2.0 kg in the BIC/FTC/TAF group and 1.1 kg in the DTG/3TC group (adjusted difference, 0.9 kg; 95% CI, 0.4–1.4;

p = 0.04). This difference in weight gain between groups may be partly explained by patients in the BIC/FTC/TAF group switching from regimens (TDF/FTC/EFV and TDF/FTC/RPV) known to be associated with weight gain suppression (BIC/FTC/TAF vs DTG/3TC; 11% vs 3%; mean difference, 8%; 95% CI, 5%–11%;

p < 0.01) [

28,

29]. Moreover, overall adverse effects were generally similar between groups, but increased weight or obesity was the leading cause of discontinuation in patients switching to a regimen of BIC/FTC/TAF than those switching to DTG/3TC. Despite the 0.9 kg difference in weight increase, lipid profile was generally unchanged from baseline across both groups.

Our study has several limitations, and the results should be carefully interpreted. First, this was a retrospective study with unbalanced baseline characteristics between the two groups, and some of the discontinuations were made by the treating physicians. Therefore, we used a logistic regression model for multivariate analyses to adjust for possible confounding factors or bias. Second, the small number of detectable viral loads at week 48 limited our statistical power when constructing a multivariate model to identify potential risk factors. Third, the included people living with HIV were mainly taking single-tablet regimens before switching to DTG/3TC or BIC/FTC/TAF, and its generalizability was limited to PWH who took multiple-tablet regimens. Fourth, around 50% of all the included PWH had data on resistance-associated mutations before the switch because antiretroviral resistance testing was not routinely available in PWH who initiated or switched ART in Taiwan. Finally, this was a single-center study that lasted for only 48 weeks, limiting the ability to extrapolate.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study suggests that the effectiveness and safety profiles of DTG/3TC and BIC/FTC/TAF were comparable in treatment-experienced adults with HIV, especially among those with undetectable viral loads at baseline. However, the presence of high viral loads, low-level viremia, and frequent virologic failure before the switch might impact the benefits of these regimens in the short term of follow-up.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-Y.C. and S.-Y.L.; methodology, C.-Y.C.; software, C.-Y.C. and S.-Y.L.; validation, S.-Y.C., S.-Y.K., C.-P.C., and Y.-C.L.; formal analysis, C.-Y.C. and S.-Y.L.; investigation, C.-Y.C. and S.-H.C.; resources, C.-Y.C. and S.-H.C.; data curation, , C.-Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.-Y.L.; writing—review and editing, C.-Y.C.; visualization, C.-Y.C.; supervision, C.-Y.C.; project administration, S.-Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Taoyuan General Hospital (TYGH112029).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study and all data were analyzed without personal sensitive information.

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed or generated during this study are included in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV. 2023. Available online: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/guidelines/documents/adult-adolescent-arv/guidelines-adult-adolescent-arv.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- European AIDS Clinical Society. EACS guidelines version 12.0. 2023. Available online: https://www.eacsociety.org/media/guidelines-12.0.pdf (accessed on October 2023).

- Gandhi, R.T.; Bedimo, R.; Hoy, J.F.; Landovitz, R.J.; Smith, D.M.; Eaton, E.F. , Lehmann, C.; Springer, S.A.; Sax, P.E.; Thompson, M.A., et al. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and pre vention of HIV infection in adults: 2022 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society–USA panel. JAMA 2023, 329, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolle, C.P.; Arribas, J.R.; Ortiz, R.; Matthews, J.; Man, C.; Grove, R.; Donovan, C.; Wynne, B.; Kisare, M.; Jones, B.; et al. High Efficacy of Dolutegravir/Lamivudine (DTG/3TC) in Treatment-Naive Adults With HIV-1 and High Baseline Viral Load (VL): 48-Week Subgroup Analyses of the GEMINI-1/-2 and STAT Trials. HIV Drug Therapy Glasgow 2022; Virtual and Glasgow, Scotland. Poster P056.

- Wyk, J.V.; Ajana, F.; Bisshop, F.; Wit, S.D.; Osiyemi, O.; Sogorb, J.P.; Routy, J.P.; Wyen, C.; Ait-K, M.; Nascimento, M.C.; et al. Efficacy and safety of switching to dolutegravir/lamivudine fixed-dose 2-drug regimen vs continuing a tenofovir alafenamide–based 3- or 4-drug regimen for maintenance of virologic suppression in adults living with human immunodeficiency virus type 1: phase 3, randomized, noninferiority TANGO study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020, 71, 1920–1929. [Google Scholar]

- Cahn, P.; Madero, J.S.; Arribas, J.R.; Antinori, A.; Ortiz, R.; Clarke, A.E.; Hung, C.C.; Rockstroh, J.K.; Girard, P.M.; Sievers, J.; et al. Dolutegravir plus lamivudine versus dolutegravir plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine in antiretroviral-naive adults with HIV-1 infection (GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2): week 48 results from two multicentre, double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 trials. Lancet 2019, 393, 143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Llibre, J.M.; Brites, C.; Cheng, C.Y.; Osiyemi, O.; Galera, C.; Hocqueloux, L.; Maggiolo, F.; Degen, O.; Taylor, S.; Blair, E.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Switching to the 2-Drug Regimen Dolutegravir/Lamivudine Versus Continuing a 3- or 4-Drug Regimen for Maintaining Virologic Suppression in Adults Living With Human Immunodeficiency Virus 1 (HIV-1): Week 48 Results From the Phase 3, Noninferiority SALSA Randomized Trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2023, 76, 720–729. [Google Scholar]

- De Socio, G.V.; Tordi, S.; Altobelli, D.; Gidari, A.; Zoffoli, A.; Francisci, D. Dolutegravir/Lamivudine versus Tenofovir Alafenamide/Emtricitabine/Bictegravir as a Switch Strategy in a Real-Life Cohort of Virogically Suppressed People Living with HIV. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocabert, A.; Borjabad, B.; Berrocal, L.; Blanch, J.; Inciarte, A.; Chivite, I.; Gonzalez-Cordon, A.; Torres, B.; Ambrosioni, J.; Martinez-Rebollar, M.; et al. Tolerability of bictegravir/tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine versus dolutegravir/lamivudine as maintenance therapy in a real-life setting. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2023, 78, 2961–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Xie, X.; Fu, Y.; Yang, X.; Ma, S.; Kong, L.; Song, C.; Song, Y.; Ren, T.; Long, H. Bictegravir/ Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Alafenamide Versus Dolutegravir Plus Lamivudine for Switch Therapy in Patients with HIV-1 Infection: A Real- World Cohort Study. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2023, 12, 2581–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wensing, A.M.; Calvez, V.; Ceccherini-Silberstein, F.; Charpentier, C.; Günthard, H.F.; Paredes, R.; Shafer, R.W.; Richman, D.D. 2022 update of the drug resistance mutations in HIV-1. Top. Antivir. Med. 2022, 30, 559–574. [Google Scholar]

- Gallant, J.; Lazzarin, A.; Mills, A.; Orkin, C.; Podzamczer, D.; Tebas, P.; Girard, P.M.; Brar, I.; Daar, E.S.; Wohl, D.; et al. Bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide versus dolutegravir, abacavir, and lamivudine for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection (GS-US-380-1489): a double-blind, multicentre, phase 3, randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 2063–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sax, P.E.; Pozniak, A.; Montes, M.L.; Koenig, E.; DeJesus, E.; Stellbrink, H.J.; Antinori, A.; Workowski, K.; Slim, J.; Reynes, J.; et al. Coformulated bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide versus dolutegravir with emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide, for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection (GS-US-380-1490): a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 2073–2082. [Google Scholar]

- Sax, P.E.; Rockstroh, J.K.; Luetkemeyer, A.F.; Yazdanpanah, Y.; Ward, D.; Trottier, B.; Rieger, A.; Liu, H.; Acosta, R.; Collins, S.E.; et al. GS-US-380–4030 Investigators. Switching to Bictegravir, Emtricitabine, and Tenofovir Alafenamide in Virologically Suppressed Adults With Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e485–e493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreatta, K.; Willkom, M.; Martin, R.; Chang, S.; Wei, L.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.P.; Graham, H.; Quirk, E.; Martin, H.; et al. Switching to bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide maintained HIV-1 RNA suppression in participants with archived antiretroviral resistance including M184V/I. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 3555–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daar, E.S.; DeJesus, E.; Ruane, P.; Crofoot, G.; Oguchi, G.; Creticos, C.; Rockstroh, J.K.; Molina, J.M.; Koenig, E.; et al. Efficacy and safety of switching to fixed-dose bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide from boosted protease inhibitor-based regimens in virologically suppressed adults with HIV-1: 48 week results of a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet HIV 2018, 5, e347–e356. [Google Scholar]

- Molina. J.M.; Ward, D.; Brar, I.; Mills, A.; Stellbrink, H.J.; López-Cortés, L.; Ruane, P.; Podzamczer, D.; Brinson, C.; Custodio, J.; et al. Switching to fixed-dose bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide from dolutegravir plus abacavir and lamivudine in virologically suppressed adults with HIV-1: 48 week results of a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, active-controlled, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet HIV 2018, 5, e357–e365. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, E. Striving for diversity in research studies. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1429–1430. [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand, M.L.; Shet, A.; Chandy, S.; Singh, G.; Shamsundar, R.; Madhavan, V.; Saravanan, S.; Heylen, E.; Kumarasamy, N. Suboptimal adherence associated with virological failure and resistance mutations to first-line highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in Bangalore, India. Int. Health. 2011, 3, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantopoulos, C.; Ribaudo, H.; Ragland, K.; Bangsberg, D.R.; Li, J.Z. Antiretroviral regimen and suboptimal medication adherence are associated with low-level human immunodeficiency virus viremia. Open. Forum. Infect. Dis. 2015, 2, ofu119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J.; Caballero, E.; Curran, A.; Burgos, J.; Ocaña, I.; Falcó, V.; Torella, A.; Pérez, M.; Ribera, E.; Crespo, M. Impact of low-level viraemia on virological failure in HIV-1- infected patients with stable antiretroviral treatment. Antivir. Ther. 2016, 21, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, L.E.; Moorhouse, M.; Carmona, S.; Grobbee, D.E.; Hofstra, L.M.; Richman, D.D.; Tempelman, H.A.; Venter, W.D.F.; Wensing, A.M.J. Effect of HIV-1 low-level viraemia during antiretroviral therapy on treatment outcomes in WHO-guided South African treatment programmes: a multicentre cohort study. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joya, C.; Won, S.H.; Schofield, C.; Lalani, T.; Maves, R.C.; Kronmann, K.; Deiss, R.; Okulicz, J.; Agan, B.K.; Ganesan, A. Persistent low-level viremia while on antiretroviral therapy is an independent risk factor for virologic failure. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 69, 2145–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.J.; Sun, H.Y.; Chen, L.Y.; Hsieh, S.M.; Sheng, W.H.; Liu, W.D.; Chuang, Y.C.; Huang, Y.S.; Lin, K.Y.; Wu, P.Y.; et al. Low-level viraemia and virologic failure among people living with HIV who received maintenance therapy with co-formulated bictegravir, emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide versus dolutegravir-based regimens. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2022, 60, 106631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.J.; Sun, H.Y.; Chang, S.Y.; Cheng, A.; Huang, Y.S.; Huang, S.H.; Huang, Y.C.; Su, Y.C.; Liu, W.C.; Hung, C.C. Incidence and impact of low-level viremia among people living with HIV who received protease inhibitor- or dolutegravir-based antiretroviral therapy. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 105, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreatta, K.; Willkom, M.; Martin, R.; Chang, S.; Wei, L.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.P.; Graham, H.; Quirk, E.; Martin, H.; White, K.L. Switching to bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide maintained HIV-1 RNA suppression in participants with archived antiretroviral resistance including M184V/I. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 3555–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, M.M.; Armenia, D.; Teyssou, E.; Santos, J.R.; Charpentier, C.; Lambert-Niclot, S.; Antinori, A.; Katlama, C.; Descamps, D.; Perno, C.F.; et al. Virological efficacy of switch to DTG plus 3TC in a retrospective observational cohort of suppressed HIV-1 patients with or without past M184V: the LAMRES study. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2022, 31, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sax, P.E.; Erlandson, K.M.; Lake, J.E.; Mccomsey, G.A.; Orkin, C.; Esser, S.; Brown, T.T.; Rockstroh, J.K.; Wei, X.; Carter, C.C.; et al. Weight gain following initiation of antiretroviral therapy: risk factors in randomized comparative clinical trials. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.H.; Huang, W.C.; Lin, S.W.; Chuang, Y.C.; Sun, H.Y.; Chang, S.Y.; Kuo, P.H.; Wu, P.Y.; Liu, W.C.; Chiang, C.; et al. Impact of efavirenz mid-dose plasma concentration on long-term weight change among virologically suppressed people living with HIV. J. Acquir. Immune. Defic. Syndr. 2021, 87, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).