1. Introduction

The concept of disability has changed significantly over the second half of the 20th century with new ideas in biological science, psychology, and human services reframing thinking of disability for children with disabilities, their families and early intervention professionals. Expectations and opportunities for children with disabilities and their families now exist due to the recognition of the social model of disability [

1], the normalization principle [

2], the environmental influence on intelligence [

3], and the recognition of the influence of complex environments on health [

4]. The highest priority is for countries to ensure that every child has a good start to life [

5]. and that they have equal opportunities and are consulted about their inclusive services [

6]. Early Intervention (EI) for infants and pre-schoolers with disabilities is seen as essential in tempering the impact of any impairments on their development. Early intervention services internationally differ both within and between countries and can be complex [

7]. They are situated in contexts that are unique in terms of culture, policy, legislation, underpinning philosophies and people. Early intervention services include multiple stakeholders, for example, health and social care professionals, education professionals, and families. Integrating early intervention within existing often complex health service systems is necessary, although it is a challenging thing to do. Providing integrated, family-centred, culturally appropriate and socially inclusive EI services is complex. In different countries, services are shaped and delivered in different ways [

8]. Development of services, at whatever stage they are at can be informed by a conceptual understanding of EI. This understanding must be informed by relevant theory as well as the participation of those involved in EI in order to inform best practices. We need to situate theories to EI practice by developing models that are underpinned by conceptual constructs. These models can then support the implementation and evaluation of best practice EI services.

Family Systems Theory [

9] and Ecological Systems Theory [

10] offer ways of thinking about the family and the context of human development. Applying family systems theories can help us focus on factors that can be applied in practice [

11]. When trying to understand a complex phenomenon, it is important to include the perspectives of all who use the services while recognising the ecological perspective where the family is viewed as a system that is part of other social systems, for example, education and healthcare [

12]. There is value in including everyone involved in a service to share their experiences. Parents and professionals are frequently asked about their views of disability services. However, children are often excluded.

Family-centred practice is a social model for health, education and social care services that expands the focus of intervention beyond the child’s level of functioning to view the child in the context of their family [

13]. Using a systems approach is compatible with a family-centred philosophy in EI when the target of intervention is the family system and not solely the child. Family-centred practice involves the EI service being responsive to family priorities and needs [

14]. A systems approach has influenced treatment and opportunity for children with disabilities and their families in EI practice [

15,

16]. Other theories which became relevant to EI practice are Social Exchange Theory [

17], Interdependence Theory [

18], and Social Penetration Theory [

19]. Although some of these theories draw on dated literature, the theories supported the development of a conceptual model from the participants’ perspectives [

20]. Thus, there is a need for a Grounded Theory study to understand how theories underpin the current context of EI practice. This paper presents a research study that aimed to build a model of facilitating and hindering constructs that facilitate best practice and support integrated care for early intervention service provision in Ireland. This model can inform the development of EI services in Western Countries and beyond.

2. Materials and Methods

The reporting guidelines for Grounded Theory (GT) research were used to frame this section [

21]. As the aim of the research was to build a model for practice and based on the diversity of how EI services function and the heterogeneity of the client population who use EI services in Ireland, qualitative exploration was needed to understand the facilitating and hindering constructs from the perspectives of families and service providers [

22]. A GT methodology was used as it facilitates theory building that is ‘faithful to and illuminates the area under study’ [

23] (p. 43). A model is defined as ‘a representation of a more complex reality used deliberately to throw light on a problem’ [

24] and its development is guided by theory. An interpretivist paradigm guided the first author in the selection of tools, instruments, participants, and methods used in the study. This paradigm is most appropriate as it assumes that multiple realities exist and that the researcher and the participant co-create an understanding of the phenomenon relative to the time and the place [

25].

Following ethical approval, a staged approach to sampling was used. Initially, a purposive approach was employed to select EI services in Ireland. EI services in Ireland vary and are delivered by healthcare teams for children from birth to six years with significant developmental difficulties [

26]. Following the recruitment phase, one EI team accepted the invitation to participate. Data were collected from multiple perspectives within one early intervention disability service in Ireland. At the time of the research, children were referred to the team via an intake forum following a multi-agency forum where professionals come together to discuss a child’s needs and design a pathway of care for them. This team’s ethos was one of family-centred practice [

27]. A comprehensive transdisciplinary team-based assessment was the norm for this team, with coordinated input from the various disciplines as appropriate. The team worked closely in one location. The team comprised of over 100 families and 18 professionals, which included four Nurses, three Speech and Language Therapists, three Physiotherapists, two Occupational Therapists, one Social Worker, one Care Assistant, one Family Support Worker, one Dietician and two Psychologists, and Thirteen of the staff worked full-time on the team with five working part-time. Tertiary staff to the team were Medical Doctors, Paediatricians and Administration Support. The intervention approach used by the professionals on the team encompassed both medical and social models. Some children received both home and clinic-based interventions, while others received only clinic-based interventions.

A purposive approach was employed to sample the team in order to gain a broad representation of backgrounds and experiences, representations from all those involved in the team were included [

28]. The methods used included semi-structured interviews, theoretical sampling, and constant comparative method. Five children with intellectual disabilities (aged between 3 years and 5 years), six parents and 17 professionals shared their experiences of their early intervention disability service. In total, 31 semi-structured interviews were included, and data were collected and interpreted in a coherent, systematic and rigorous way. Each child participated using a multi-method data collection process, using a skilled facilitator and with the support of parental expertise [

29]. Parents and professionals took part in semi-structured interviews. Following verbatim transcription all data were analysed using GT methodology [

30,

31]. The first author reconstructed meaning from the data in keeping with [

32] GT methodology by immersing herself in the data, questioning the data, memoing and using a constant comparative approach. This reconstruction and development of conceptual understanding moved between the multiple perspectives and the literature in an iterative way. This involved reviewing theoretical ideas following the collection of data from each participant to support the emerging data from the research field. This means that the first author considered not only the voice and perspective of all those involved in the team, that is, parents, children and professionals, but also the interactions between them and the literature. As with any research study issues of rigour and trust are important [

33]. This research was conducted in a rigorous manner supporting the trustworthiness of the conceptual model, through the use of an audit trail, peer review by the second author and an expert panel, persistent observation, prolonged engagement and use of multiple perspectives. Numerous theories, to support the development of the model, were identified during this research, which highlights the complexity of the EI context. The conceptual model acknowledges the existence of synergistic interdependent relationships in an EI context. When considering outcomes of service delivery professionals and policy makers need to consider how rewarding and enabling the service is to all involved in the relationship.

3. Results

In the process of making sense of the data from multiple perspectives and through the application of the constant comparative approach as per [

34] GT, several theories became relevant while making sense of the data. These theories became the foundational concepts for understanding the complex phenomena of early intervention practice. These theories, notably Family Systems Theory [

35] Social Exchange Theories [

36,

37,

38], and Social Penetration Theories [

39,

40] supported the first author’s interpretation of the multiple perspectives shared and in understanding the complexity of EI practice.

Family Systems Theory [

41] a branch of General Systems Theory, provides a way to conceptualise family members as interacting with and mutually influencing one another. Within General Systems Theory there are the concepts of Interdependence where elements are mutually influential in the relationship. Each family member has unique characteristics, a relationship to each of the other family members, and to the family as a whole. Each family member influences, and is influenced by, each of the other family members. Any change in the characteristics of one member, or in the relationships between family members, affects the entire family system.

Social Exchange Theory [

42] states that ‘relationships grow, develop, deteriorate, and dissolve as a consequence of an unfolding social-exchange process, which may be conceived as a bartering of rewards and costs’ [

43] (p. 4). The constructs of this theory include disclosure, relational expectations, and perceived rewards or costs in the relationship. Theory of Interdependence is part of Social Exchange Theory [

44]. Individuals enter relationships with an awareness of societal norms for relationships and a repertoire of previous experiences [

45]. Within exchange relationships levels of involvement, dependence, and resources contribute importantly to the different patterns of interaction observed within personal relationships [

46]. [

47] developed the investment model, which is an extension of the interdependence model. Investments, intrinsic or extrinsic, are attached to a relationship and help predict outcome. Intrinsic investments are related to time and effort invested directly in a relationship and extrinsic investments develop over time and are related to resources or benefits, identity and being part of a group [

48].

According to [

49] Social Penetration Theory, couples and friends disclose more information as their relationship changes from strangers to relational partners. [

50] expanded [

51]’s theory identifying five stages: Initiating, Experimenting, Intensifying, Integrating, and Bonding. [

52] state that relationships between individuals who mutually influence each other, share some degree of behavioral interdependence within repeated interactions.

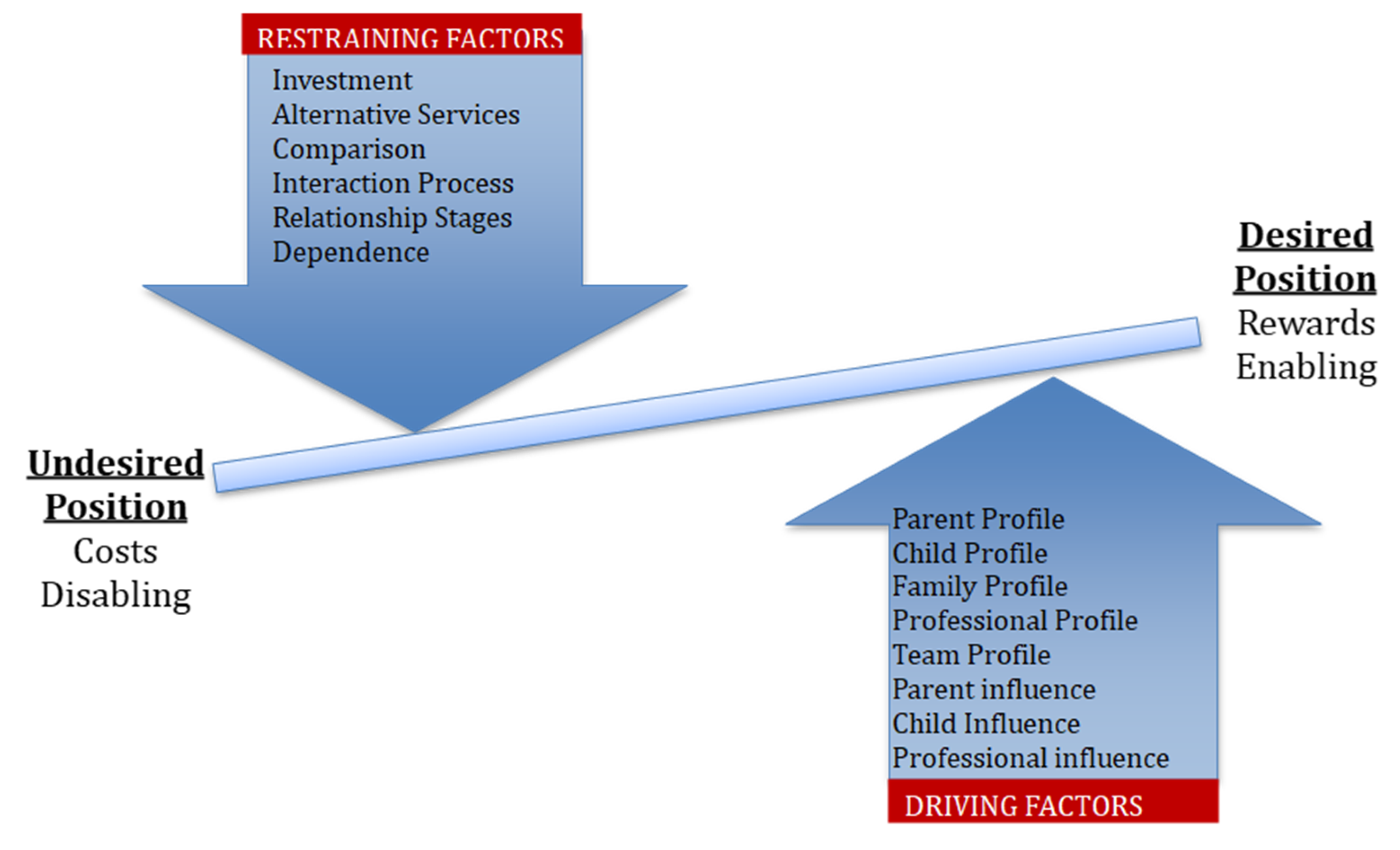

The model, Factors Affecting the Relationship in Early Intervention Practice, proposes that the EI relationship is influenced by driving factors and restraining factors. Driving factors include: People Influences and System Influences. The people in the EI relationship are the child, parent(s) and professional(s). They have their own profiles/characteristics to bring to the relationship and each person has influence, which they can exert in different ways in the relationship. Restraining factors include: Relationship Stages, Comparison, Alternative Services, Interaction Process, Dependence and Investment.

This model proposes that everyone in the relationship must work together to maintain equilibrium between the influences, these are, drivers or restrainers.

Figure 1 illustrates the factors affecting the synergistic interdependent relationship in EI [

53].

3.1. Driving Factors

The predominant driving factors are the people involved in the relationship.

3.1.1. Team Profile & Influence

Initially, it is important to identify the team profile, identify the team members, identify what approach underpins the team’s practice, identify who is in the relationship and recognise their critical attributes. Each person can influence the relationship either positively or negatively. Furthermore, the people in the relationship have the potential to drive the relationship to be a rewarding one.

3.1.2. Child Profile & Influence

Acknowledging the profile of the child is important for professionals to understand their ‘personality’, their ‘needs’ in terms of services and therapy, and understand their ‘skills’ and ‘difficulties’. The child can exert their influence in their relationships in several ways. Their needs and difficulties dictate which professionals they meet. Each child has his/her own interests, likes, and skills of recognition. Each child is different, is unique and has a level and range of skills. Their level of motivation in activities can influence the relationship and outcomes. Hence, when a child is interested they are motivated and engage in interactions. The children can make decisions regarding whether or not to participate during their interactions and within their relationships.

3.1.3. Parent Profile & Influence

Acknowledging the profile of the parent is important through understanding each parent’s ‘personality’, their ‘needs’ to support their child and their ‘preferences’ in terms of therapy and/or ‘style’ of interaction. Each parent exerts their influence in the relationships in several ways. Parenting style and parenting decisions are specific to each family. Parents have commitments outside the home and this may impact on a parent’s flexibility. Parents influence how they adapt to change, how they link interventions to the home setting and in decision-making about their level of involvement in intervention and services. Parents differ in their motivation, desires and need to be involved in therapy and therapy activities. Knowing what to expect was important: being aware of what to expect from intervention, clarifying roles, and having clear boundaries. Knowing and being aware of limits creates influence, as do knowing goals and knowing what professionals are working on. Furthermore, knowing about collaboration and professional discussions was important to parents. Parents demonstrated their influence through setting and determining goals for their child and through supplementing and supporting assessment with their evidence and observations from other settings in which their child interacts. Parents have the knowledge and awareness of the home setting in terms of activities and communication with their child.

3.1.4. Professional Profile & Influence

Acknowledging the profile of the professional is important through understanding the professional’s ‘training’, their ‘previous work experiences’ and ‘team working background’, and their ‘work ethic’. Each professional is different in terms of their interactions and goals and has different ways of dealing with differences of opinion and conflict. ‘Collaboration’ with families exists whereby professionals plan for interventions and inputs with families. However, professionals’ decisions can be predominantly ‘expert driven’ and ‘authoritative’ where they make decisions without consulting parents. They can make decisions about therapy interventions such as the setting and who will deliver the intervention and identify and measure goals. They can show ‘authority’ by not allowing some parents to seek other therapy options. They may also ‘inform’ and tell parents rather than collaborate. The professional profile is influenced by the team profile and guiding principles underpinning their professional practice.

3.1.5. Family Profile & Influence

The child and parent profiles dictate the amount or level of interaction families need. Therefore, the professionals make decisions based on the family profile. Similar to the child and the parent making decisions on their level of interactions with families, professionals exerted their influence in the relationship by ‘protecting’ themselves and ‘pulling back’ and limiting interactions as they saw fit.

3.2. Restraining Factors

The restraining factors are embedded within a macro context, for example, the country and the organisational context where the EI relationship is situated. These contexts need to be considered in terms of their influence on how services are delivered. The restraining factors include: Investment, Alternative Services, Comparison, Interaction Process, Relationship Stages and Dependence.

3.2.1. Investment Is Linked to Intrinsic and Extrinsic Investments

‘Motivation’ as an intrinsic investment needs to be considered in terms of how it could influence each person in the relationship positively or negatively. For example, if a child is not motivated to participate in an interaction, this will impact his/her engagement in activities. It could also influence how others in the relationship respond to the child. Extrinsic investment is linked to ‘therapy activities’ and programmes’ that relate to the child’s routines and structure. Considering the planning and design of interventions with families, linking goals to routines could positively influence each person in the relationship.

3.2.2. Alternative Services

A potential restrainer on the relationship was families’ need to explore other options outside the EI relationship to supplement interventions for several different reasons, such as, lack of frequency of appointments. Although involvement with alternative services was very important for some families, they often withheld this information from professionals.

3.2.3. Comparison

Comparisons include comparing a child with a developmental disability to their peers and siblings. These comparisons were made by parents in terms of development and needs. Comparisons of services were also made by families and professionals and these were based on past relational experiences, personal observations and perceptions of other people’s relationships. All need to consider how these comparisons will influence expectations of a service and in turn, influence EI relationships.

3.2.4. Interaction Process

The interaction process acts as a potential restraining factor on the relationship in terms of the context of the interactions during assessment and interventions, for example, home, school or clinic. Therefore, the context has the potential to influence the interaction because families made choices on how they would interact in particular contexts. In turn, these choices facilitated positive or negative interactions. We need to consider the place of interactions and be mindful of how they can influence the interactions of all. Importantly for families and professionals positive, respectful relationships were important: having a shared focus, respect and shared responsibility were key.

3.2.5. Relationship Stages

The influence of relationship stages relates to the understanding that the EI relationship process can be explained by an over-lapping five-stage developmental trajectory [

54]. Recognising and acknowledging where each participant is on the relationship development trajectory will facilitate the development and progression of the relationships.

3.2.6. Dependance

In terms of Dependence, families need the skillset of the EI professionals which in turn may foster dependency and lead to family-focussed dependence. Families desired techniques to be modelled and shared and to understand the strategies needed to help their child. Families highlighted that there would be a lifelong need for expert advice and support. Professionals also recognised that meeting the parents’ needs included modelling and integration of goals and skills in the home setting and other contexts. Professional-focused dependence also included professionals shielding parents by masking information or withholding information to protect the families they were working with.

4. Discussion

This section aims to discuss the key relationships between the categories and the concepts in the model and position in current literature and share implications for practice [

55]. This research promoted and facilitated children’s participation, thus advancing childhood research [

56]. The importance of facilitating research ‘with’ children with disabilities rather than ‘on’ children with disabilities is increasingly recognised and promoted. EI professionals can support young children with disabilities to participate in research activities and in decision-making about their EI service [

57]. Listening to children’s perspectives can influence how professionals and families collaborate to devise a plan to reflect the child’s and families’ priorities and strengths [

58,

59]. Researchers and professionals have a responsibility to include children with speech, language and communication needs in research and practice [

60]. EI professionals must include children’s perspectives in practice. By doing so, they can support the implementation of interest-based child learning opportunities within the context of their everyday activities [

61,

62,

63]. This in turn may lead to improved relationships between families and teams and augment intervention outcomes.

The developed conceptual model, informed by theory, can support early intervention practice in Ireland and is transferrable to other teams who support children with disabilities in Western countries. This conceptual model ‘provides an initial understanding and explanation of the nature and dynamics’ [

64] (p. 231), of an EI team. It is both a shared model and an all-inclusive one, combining the views of children, parents and professionals supporting all involved in EI disability services. The model can be used by professionals to reflect on how they provide their service and it can be used by families to reflect on the service they are involved with. When we consider the constructs of social exchange theory, they include disclosure, relational expectations, and perceived rewards or costs in the relationship. In practice, understanding the role of each partner in the relationship, their extended roles, involvement, expectations and motivations will lead to rewards and enabling outcomes for the EI relationship. Professionals must allocate time to understanding what engagement in intervention looks like for families [

65]. This will in turn enable a family-centered experience for all involved. Furthermore, research about engagement involving Occupational Therapists [

66] and speech and language therapists [

67] shared that professionals need to be open-minded, share information and reflect on their interactions with families so that they understand that engagement looks different for individual families. The relationship between professionals and families is a dynamic one and professionals need to adapt to parent and child needs and preferences [

68,

69]. Considering the underpinning conceptual constructs built as a model in this way provides a structure to consider and through which to potentially share, families’ and professionals’ perspectives on engagement.

In practice, it is important to identify the team profile. Firstly, identify the team members, for example, are the parents part of the team member or are they recipients of the EI service? Are early childhood educators part of the team as well as health and social care professionals? Secondly, identify what underpins the team’s practice, for example, family-centred or child-centred or social model or medical model and identify the roles and duties of each team member, for example, is there a coordinator, and/or a key worker role. Thirdly, identify who is in the relationship and recognise their critical attributes. Each person can at times influence the relationship either positively or negatively. The people in the relationship have the potential to drive the relationship to be a rewarding one. Awareness of roles allows for clear boundaries and coherent decision-making. Unclear roles or inaccurate perceptions of roles impacts on boundaries and will subsequently impact on interactions between all involved. Furthermore, clear boundaries are interdependent with clear roles and may influence interactions and expectations [

70].

The continuity of care and the continuous sharing of information between the professionals, the parents and the children will facilitate trust and shared decision-making and may subsequently reduce conflicts and discord that may otherwise occur. At a practice level professionals need to support each other families in the shared decision-making process within family-centred practice [

71]. All stakeholders, professionals, families and children with disabilities need to work collaboratively and acknowledge the level of engagement, commitment, skills and knowledge each person brings. The model provides a structure to consider these constructs to enable positive engagement in an EI service for families and professionals.

The conceptual model of constructs from this study adds to the world view of EI services by explaining multiple perspectives about EI services in the unique Irish context. This model can inform service development in Ireland and across the world. The Roadmap for Service Improvement 2023-2026 is a policy framework currently guiding Children’s Disability Services in Ireland. This policy framework aims for children to have fun, learn and develop interests and skills and form positive relationships with others [

72]. A priority area of this policy is to better support parents and families through prevention and EI programmes. The conceptual model shared here can inform the implementation of this policy framework as it supports the collaboration of children, families and children with disabilities.

5. Conclusions

Equipped with the knowledge that each person can influence the relationship combined with an awareness of what the restraining and driving factors are for each individual, interventions for children with disabilities and their families can be family-centred. Finding this balance requires an acknowledgement of the constructs within the relationship and identifying the need for conversations about process and outcomes for individual families. This balancing act is core to EI practice and due regard must be given to the driving and restraining factors within each partnership. In order to meet this goal, attentive consideration needs to be given to the profile and influence of each individual within the relationship. When considering outcomes of service delivery professionals and policy makers need to consider how rewarding and enabling the service is to all involved in the relationship.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C.; methodology, C.C. and J.S; formal analysis, C.C.; investigation, C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C.; writing—review and editing, C.C. and J.S.; supervision, J.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the University of Galway, Galway, Ireland Ethics Committee in 2009.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. Assent was obtained from the child participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data associated with this study are not deposited in a publicly available repository.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the children, parents, and professionals who took part in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EI |

Early Intervention |

| GT |

Grounded Theory |

References

- Oliver, M. A. New Model of the Social Work Role in Relation to Disability. In The Handicapped Person: a New Perspective for Social Workers?; Camplling, J.(Editor); RADAR: London, UK, 1981.

- Wolfensberger, W. The Principle of Normalisation in Human Services. National Institute on Mental Retardation: Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 1972.

- Lewin, K. A Dynamic Theory of Personality. McGraw-Hill: New York, USA, 1935.

- World Health Organization. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. Paper presented at the First International Conference on Health Promotion, Ottawa, 1986.

- Marmot, M., Allen, J., Bell, R., Bloomer, E., Goldblatt, P. WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet 2012, 380, 1011–1029.

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Seen, Counted, Included: Using data to shed light on the well-being of children with disabilities, UNICEF, New York, 2021. Available online: https://did4all.com.au/resources/unicef-2021-seen-counted-included-using-data-to-shed-light-on-the-well-being-of-children-with-disabilities (accessed 11th March 2025).

- Guralnick M. J. Why Early Intervention Works: A Systems Perspective. Infants and Young Children 2011, 24(1), 6–28. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, C., Murphy, G., Sixsmith, J. The Progression of Early Intervention Disability Services in Ireland. Infants and Young Children 2013, 26(1), 1-88. [CrossRef]

- Bowen, M. Family Therapy in Clinical Practice. Aronson, J.: New York, USA, 1978.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Harvard University Press: USA, 1979.

- Dunst C. J. (2023). Meta-Analyses of the Relationships between Family Systems Practices, Parents' Psychological Health, and Parenting Quality. International journal of environmental research and public health 2023, 20(18), 6723. [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Making Human Beings Human: Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development. Sage: USA, 2005.

- Davis, J.M. Analysing participation and social exclusion with children and young people: Lessons from practice. International Journal of Children's Rights 2007, 15(1), 121-146.

- Dunst, C.J., Espe-Sherwindt, M. Family-centered practices in early childhood intervention. In Handbook of Early Childhood Special Education, Reichow, B., Boyd, B.A., Barton, E.E., Odom, S.L., Eds.; Springer; New York, USA, 2016; pp. 37–55.

- Guralnick M. J. Why Early Intervention Works: A Systems Perspective. Infants and Young Children 2011, 24(1), 6–28. [CrossRef]

- Guralnick M. J. Applying the Developmental Systems Approach to Inclusive Community-Based Early Intervention Programs: Process and Practice. Infants and Young Children 2020, 33(3), 173–183. [CrossRef]

- Homans, G. Social Behavior: Its Elementary Forms. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: New York, USA, 1961.

- Thibaut, J. W., Kelley, H. H. The Social Psychology of Groups. Wiley: New York, USA, 1959.

- Altman, I., Taylor, D. A. Social Penetration: The Development of Interpersonal Relationships. Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, USA, 1973.

- Seedhouse, D. Health Promotion: Philosophy, Prejudice and Practice. John Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1997.

- Bøttcher Berthelsen, C., Grimshaw-Aagard, S. L. S., Hansen, C. Developing a Guideline for Reporting and Evaluating Grounded Theory Research Studies (GUREGT). International Journal of Health Sciences 2018, 6(1), 64-76. [CrossRef]

- Sandall, S.R., Smith, B.J., Mclean, M.E., Broudy-Ramsey, A. Qualitative research in early intervention/early childhood special education. Journal of Early Intervention 2002, 25(2), 129-136.

- Strauss, A., Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory (2nd ed.). Sage: Newbury Park, California, USA, 1998.

- Seedhouse, D. Health Promotion: Philosophy, Prejudice and Practice. John Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1997.

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, USA, 2002.

- Carroll, C., Murphy, G., Sixsmith, J. The Progression of Early Intervention Disability Services in Ireland. Infants and Young Children 2013, 26(1), 1-88. [CrossRef]

- Dunst, C.J. Key Characteristics and Features of Community-based Family Support Programs. Family Resource Coalition: Chicago, IL, 1995.

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, USA, 2015.

- Carroll, C., Sixsmith, J. Exploring the facilitation of young children with disabilities in research about their early intervention service. Child Language Teaching and Therapy 2016, 32(3), 313-325. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, C., Sixsmith, J. A Trajectory of Relationship Development for Early Intervention Practice for Children with Developmental Disabilities. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation 2016, 23(2), 81-90. [CrossRef]

- O’Shaughnessy Carroll, C. Understanding Early Intervention Services in Ireland: A Conceptual Evaluation, Doctoral Dissertation, University of Galway, Galway, Ireland, November, 2016). Available online: https://aran.library.nuigalway.ie/bitstream/handle/10379/6361/2016oshaughnessycarrollphd.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Strauss, A., Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; Sage: Newbury Park, California, USA, 1998.

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, Sage: Thousand Oaks, USA, 2002.

- Strauss, A., Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; Sage: Newbury Park, California, USA, 1998.

- Bowen, M. Family Therapy in Clinical Practice. Aronson, J.: New York, USA, 1978.

- Homans, G. Social Behavior: Its Elementary Forms. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: New York, USA, 1961.

- Thibaut, J. W., Kelley, H. H. The Social Psychology of Groups. Wiley: New York, USA, 1959.

- Rusbult, C. E. Commitment and satisfaction in romantic associations: A test of the investment model. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 1980, 16, 172-186.

- Altman, I., Taylor, D. A. Social Penetration: The Development of Interpersonal Relationships. Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, USA, 1973.

- Knapp, M. L., Vangelisti, A. L. Interpersonal communication and human relationships (5th ed.). Allyn and Bacon: Boston, USA, 2005.

- Bowen, M. Family Therapy in Clinical Practice. Aronson, J.: New York, USA, 1978.

- Homans, G. Social Behavior: Its Elementary Forms. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: New York, USA, 1961.

- Burgess, R. L., Huston, T. L. (Eds.). Social Exchange in Developing Relationships: Academic Press, 1979.

- Thibaut, J. W., Kelley, H. H. The Social Psychology of Groups. Wiley: New York, USA, 1959.

- Thibaut, J. W., Kelley, H. H. The Social Psychology of Groups. Wiley: New York, USA, 1959.

- Thibaut, J. W., Kelley, H. H. The Social Psychology of Groups. Wiley: New York, USA, 1959.

- Rusbult, C. E. Commitment and satisfaction in romantic associations: A test of the investment model. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 1980, 16, 172-186.

- Rusbult, C. E. (1980). Commitment and satisfaction in romantic associations: A test of the investment model. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 16, 172-186.

- Altman, I., & Taylor, D. A. Social Penetration: The Development of Interpersonal Relationships. Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, USA, 1973.

- Knapp, M. L., Vangelisti, A. L. Interpersonal communication and human relationships (5th ed.). Allyn and Bacon: Boston, USA, 2005.

- Altman, I., & Taylor, D. A. Social Penetration: The Development of Interpersonal Relationships. Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, USA, 1973.

- Guerrero, L. K., Andersen, P. A., & Afifi, W. A. Close encounters: Communication in relationships (3rd ed.). Sage: Thousand Oaks, California, USA, 2011.

- O’Shaughnessy Carroll, C. Understanding Early Intervention Services in Ireland: A Conceptual Evaluation, Doctoral Dissertation, University of Galway, Galway, Ireland, November, 2016). Available online: https://aran.library.nuigalway.ie/bitstream/handle/10379/6361/2016oshaughnessycarrollphd.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Carroll, C., Sixsmith, J. A Trajectory of Relationship Development for Early Intervention Practice for Children with Developmental Disabilities. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation 2016, 23(2), 81-90. [CrossRef]

- Bøttcher Berthelsen, C., Grimshaw-Aagard, S. L. S., Hansen, C. Developing a Guideline for Reporting and Evaluating Grounded Theory Research Studies (GUREGT). International Journal of Health Sciences 2018, 6(1), 64-76. [CrossRef]

- Tisdall, E. K. M. Applying human rights to children’s participation in research. In Twomey, M., Carroll, C. Eds.; Seen and heard: Participation, engagement and voice for children with disabilities. Peter Lang: Oxford, UK, 2018, pp. 17-38.

- Carroll, C., Sixsmith, J. Exploring the facilitation of young children with disabilities in research about their early intervention service. Child Language Teaching and Therapy 2016, 32(3), 313-325. [CrossRef]

- Bruder, M. B. Coordinating services with families. In Working with families of young children with special needs, McWilliam, R. A., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, USA, 2010; pp. 93-126.

- McAllister, L., Carroll, C., Gillett-Swan, J., McGills, N. Responsibilities of speech and language pathologists in supporting children’s rights: more than listening. Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech-Language Pathology 2023, 25(2), 70–75. [CrossRef]

- Lyons, R., Carroll, C., Gallagher, A., Merrick, R., Tancredi, H. Understanding the perspectives of children and young people with speech, language and communication needs: How qualitative research can inform practice. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 2022, 24(5), 547–557. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, C. Positioning the Views of Children with Developmental Disabilities at the Centre of Early Interventions. In The Lives of Children and Adolescents with Disabilities,1st Ed.; Beckett, A.E., Callus, A.M., Eds.; Routledge; London, UK, 2024; Chapter 7, pp. [CrossRef]

- Lyons, R., Carroll, C., Gallagher, A., Merrick, R., Tancredi, H. Understanding the perspectives of children and young people with speech, language and communication needs: How qualitative research can inform practice. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 2022, 24(5), 547–557. [CrossRef]

- Dunst, C. J., Raab, M., Trivette, C. L., Swanson, J. Community-based everyday child learning opportunities. In Working with families of young children with special needs, McWilliam, R. A., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, USA, 2010; pp. 60-92.

- Lynham, S. A. The general method of theory-building research in applied disciplines. Advances in Developing Human Resources 2002, 4(3), 221-235. [CrossRef]

- Imms, C., Granlund, M., Wilson, P.H., Steenburger, B., Rosenbaum, P., Gordon, A. Participation - both a means and an end. A conceptual analysis of processes and outcomes in childhood disability. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2017, 59(1), 16–25.

- D'Arrigo, R., Copley, J. A., Poulsen, A. A., Ziviani, J. (2020). Parent engagement and disengagement in paediatric settings: an occupational therapy perspective. Disability and Rehabilitation 2020, 42(20), 2882–2893. [CrossRef]

- Melvin, K., Meyer, C., Scarinci, N. What does a family who is “engaged” in early intervention look like? Perspectives of Australian speech-language pathologists. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 2021, 23(3), 236-246. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, C. Positioning the Views of Children with Developmental Disabilities at the Centre of Early Interventions. In The Lives of Children and Adolescents with Disabilities,1st Ed.; Beckett, A.E., Callus, A.M., Eds.; Routledge; London, UK, 2024; Chapter 7, pp. [CrossRef]

- King, G., Chiarello, L.A., Thompson, L., McLarnon, M.J.W., Smart, E., Ziviani, J., Pinto, M. Development of an observational measure of therapy engagement for pediatric rehabilitation, Disability and Rehabilitation 2019, 41(1), 86-97, . [CrossRef]

- Gil-Garcia, J. R., Guler, A., Pardo, T.A., Burke, G.B. Characterizing the importance of clarity of roles and responsibilities in government inter-organizational collaboration and information sharing initiatives, Government Information Quarterly 2019, 36 (4), 101-393. [CrossRef]

- Klatte, I.S., Bloemen, M., de Groot, A., Mantel, T.C., Ketelaar, K. Gerrits, E. (2024) Collaborative working in speech and language therapy for children with DLD—What are parents’ needs? International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders 2024, 59, 340–353. [CrossRef]

- Health Service Executive, The Roadmap for Service Improvement 2023-2026, Health Service Executive, Ireland, 2023. Available online: https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/4/disability/progressing-disability/pds-programme/roadmap-for-service-improvement-2023-2026.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).