1. Introduction

Hyperbilirubinemia is a common condition in newborns, characterized by elevated levels of bilirubin in blood leading to jaundice[

1]. The incidence of hyperbilirubinemia varies significantly between term and preterm infants. In term newborns, approximately 60% develop some degree of jaundice, though only about 5-10% reach bilirubin levels that require phototherapy and less than 1% escalate to levels necessitating exchange transfusion[

2,

3]. In contrast, preterm infants are at higher risk due to immature liver function and decreased bilirubin clearance. Up to 80% of preterm neonates may develop jaundice, with about 10-15% requiring phototherapy. The proportion of preterm infants needing exchange transfusion, although higher than in term infants, remains relatively low, typically ranging from 1-5% depending on gestational age and comorbidities[

4]. Early detection and management are crucial to prevent complications such as kernicterus[

5,

6].

Kernicterus is a term that describes acute neonatal encephalopathy associated with brain toxicity due to unbound unconjugated bilirubin that crosses the blood-brain barrier. Serum bilirubin levels exceeding 25-30 mg/dL are typically associated with this condition[

7]. Kernicterus follows a specific multiregional damage pattern, primarily affecting the globus pallidus, subthalamic nucleus, geniculate nucleus, dentate nucleus, inferior olives, nucleus gracilis and cuneatus, hippocampus, mammillary bodies, red nucleus, substantia nigra, cranial nerve nuclei, colliculi, and the cerebellar vermis[

8]. The main effects of bilirubin on neurons and oligodendrocytes include apoptosis, oxidative stress and reduced myelin synthesis, accompanied by a proinflammatory microglial reaction that initiates a metabolic cascade leading to neurotoxicity[

9,

10].

This pathological process explains the typical imaging signature observed in the acute phase of kernicterus. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) sequences, particularly T1-weighted images, show phase signal hyperintensity in the globus pallidus and subthalamic nucleus[

11]. However, this hyperintensity represents only a gradient of increased signal compared to normal tissue and is not sufficiently distinctive to confirm the extent of neuronal death[

12]. Over time, usually after several weeks, a fine fibrillary astrogliotic scar becomes evident, permanently marking the globus pallidus on T2-weighted MRI scans[

13].

The epidemiology of kernicterus has evolved with advancements in neonatal care. In developed countries, where routine bilirubin screening and early interventions such as phototherapy are standard practice, the incidence of kernicterus has significantly declined. It is estimated to occur in 0.5 to 1 per 100,000 live births among term infants in high-resource settings[

14]. Conversely, in low- and middle-income countries, where access to timely medical care and phototherapy may be limited, the incidence is considerably higher, ranging from 1 to 4 per 1,000 live births[

15]. Preterm infants are particularly vulnerable due to lower thresholds for bilirubin neurotoxicity, increasing their risk of developing kernicterus even at bilirubin levels considered safe for term neonates. Early detection, vigilant monitoring, and prompt management of hyperbilirubinemia remain critical to prevent this severe, lifelong neurological condition[

16].

In this paper, we describe a case of severe hyperbilirubinemia in a term newborn who, despite receiving proper exchange transfusion therapy, developed kernicterus. We provide a detailed neuroimaging analysis, comparing magnetic resonance imaging findings at different time points to illustrate the progression of brain injury and possible early detection neuroimaging markers.

2. Case Report

Our patient, a Caucasian male infant, was born at home by eutocic delivery at 40 weeks of gestation. Antenatal imaging and serology were unremarkable, and there was no family history of metabolic diseases. At birth, positive pressure ventilation was required within the fifth minute of life, APGAR score was 7 at 1 minute and 10 at 5 minutes. Birth weight was 3260g (Average for Gestational Age – AGA, according to Bertino et al., 2010[

17]). The patient was admitted to the NICU on day 3 of life for jaundice, hypotonia, hyporeactivity and feeding difficulties. Blood exams on admission revealed significant hyperbilirubinemia (total bilirubin level: 51 mg/dl, prevalently unconjugated), blood type 0, Rhesus positive, positive direct Coombs test (maternal blood typization was A, Rhesus positive). In addition, blood cultures resulted positive for E. faecalis, S. Aureus and E. Coli, leading to a concomitant diagnosis of early onset neonatal sepsis. Neurological examination revealed signs consistent with bilirubin-induced neurotoxicity. The infant exhibited hypotonia with diminished spontaneous movements and a weak Moro reflex. Suck and rooting reflexes were markedly impaired. There was poor feeding behavior accompanied by episodes of high-pitched crying, suggestive of irritability and potential central nervous system involvement. Cranial nerve examination revealed limited upward gaze and poor tracking.

The patient underwent a blood exchange transfusion immediately after admission, reaching safe serum bilirubin levels after just one cycle. Concomitantly, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy was initiated with complete resolution of the clinical sepsis after one week of treatment. Neurological objectivity showed improvement in the following days, with persistent difficulties in gaze control and heightened reactivity indicating partial recovery with ongoing neurological impairment. Further examinations were performed: Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) showed no responses, indicating possible auditory pathway involvement. However, both electroencephalogram (EEG) and fundoscopy were normal, suggesting no widespread cortical or retinal abnormalities.

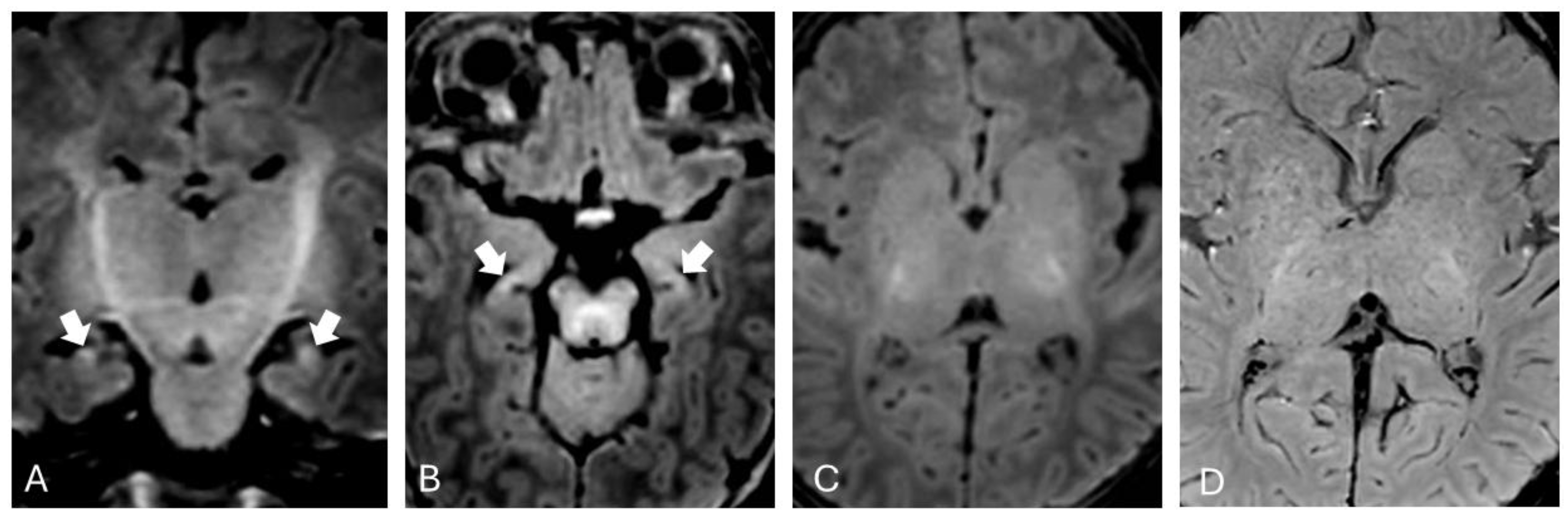

Brain MRI was performed at one month of extrauterine life and showed mild T1 hyperintensity in the hippocampi bilaterally (

Figure 1).

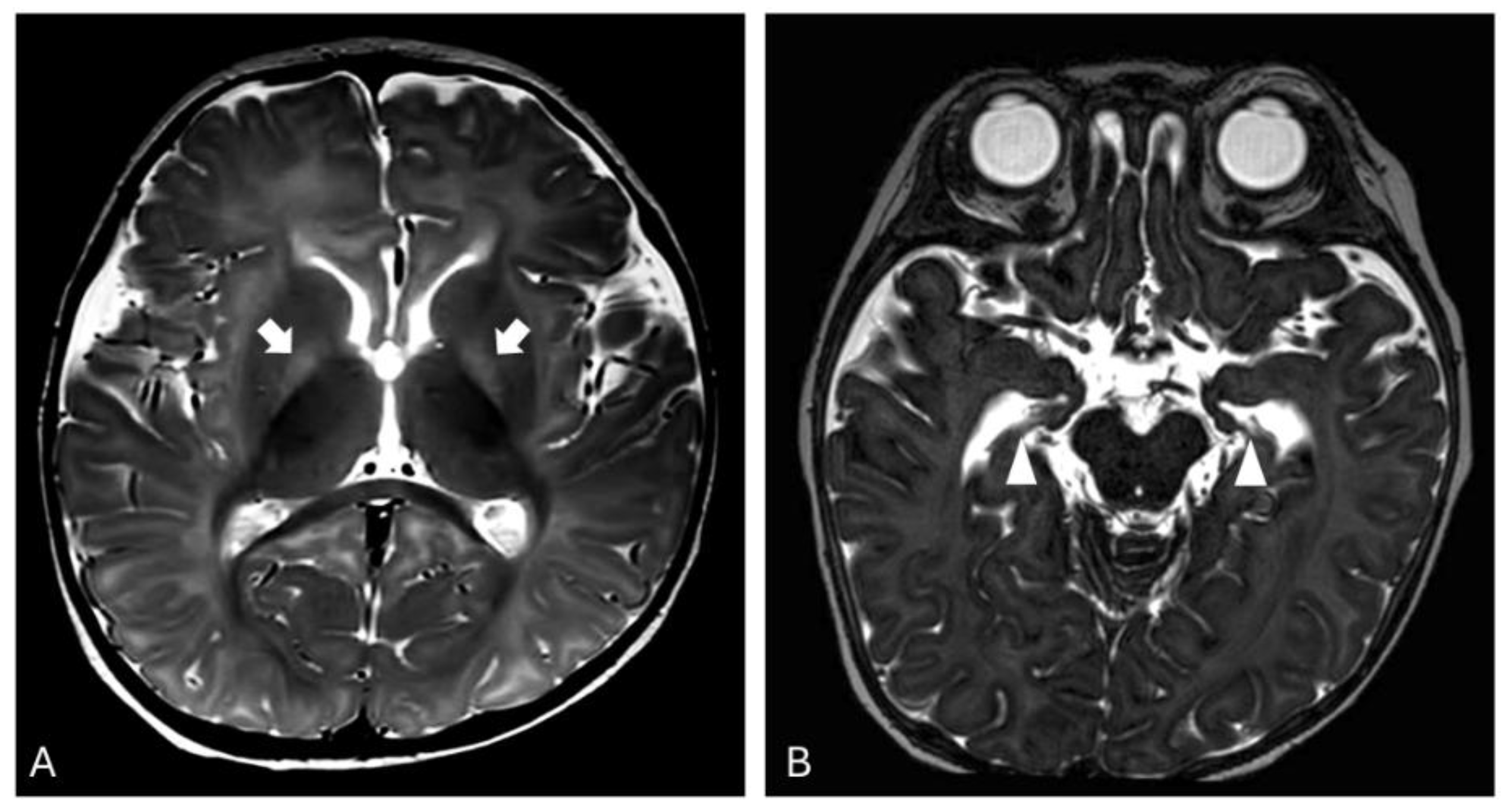

The exam was repeated at two months of life, showing partial resolution of the previously described alterations, and again at six months of age revealing T2-weighted hyperintensity in both globi pallidi and hippocampal atrophy (

Figure 2). Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS) of the basal nuclei showed a minimal reduction in N-acetylaspartate (NAA) levels. These neuroradiological findings were compatible with sequelae of kernicterus.

Clinically, the described lesions resulted in a neuropsychomotor profile characterized by strabismus, intermittent gaze, poorly fluid and organized motor activity with dyskinetic movements. There was a slight presence of antigravity movements of the lower limbs, which were quickly exhausted. Muscle tone was within normal limits, although there was absence of complete head control, with the ability to lift the head only briefly when placed in a prone position. The hands were clenched, with occasional spontaneous opening and flexion of the distal interphalangeal joints along with a transient grasping ability. Further investigations, including visual evoked potentials (VEP) and fundoscopy were within normal limits. However, ABR threshold testing revealed retrocochlear hearing loss with a conductive component, requiring the application of a cochlear implant.

Over time, the infant developed hypertonia with opisthotonus posturing and deep tendon reflexes were exaggerated, with the presence of sustained clonus.

3. Discussion

Kernicterus is an uncommon but severe condition that leads to acute neonatal encephalopathy and may result in long-term neurocognitive impairments, such as sensorineural hearing loss and dyskinetic cerebral palsy[

18]. In our patient, brain MRI performed during the subacute phase revealed hyperintense signal on T1-weighted images within the hippocampi, while T2-weighted images in the same regions appeared normal. No significant alterations were observed in the basal ganglia and subthalamic nuclei on T1-weighted sequences. The absence of obvious alterations in T1-weighted sequences may be attributed to the myelination process, which makes it more difficult to distinguish pathological changes from the expected T1 hyperintensity in these regions during normal developmental processes at this age[

19]. This is particularly true when using high-field imaging, which provides better signal-to-noise ratio. Alternatively, this could be related to the onset of the “blind window” described by Gburek-Augustat et al.[

20] which is typically observed around two months of life, during which no alterations are detectable on MRI.

During the follow-up at 2 months, a progressive normalization of the signal alterations in T1-weighted sequences in the hippocampal region was observed. At the 6-month follow-up, there was focal tissue loss, with no signal alterations in the T1-weighted sequences. In this last examination, the appearance of T2 hyperintensities in both globi pallidi was also noted, as classically described in the literature in the sequel of kernicterus, consistent with gliosis[

21,

22]. Additionally, magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) demonstrated a reduction in the N-acetylaspartate peak compared to age-matched controls, suggesting neuronal and axonal loss.

The role of Susceptibility Weighted Imaging (SWI) remains unclear. Lequin et al.[

23] recently suggested it as a more specific and sensitive tool for detecting pathological alterations in kernicterus. However, in our patient, SWI remained unremarkable. In our opinion, the use of SWI to study the nucleo-capsular region in newborns and infants remains challenging due to the myelination process and the diamagnetic properties of myelin itself[

24], which appears slightly hyperintense. Additionally, the presence of T1 hyperintense lesions can lead to a hyperintense signal in SWI images, due to a “T1 shine-through” effect[

25,

26]. Potential additional information can be obtained using Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping (QSM) both for its higher anatomical resolution compared to SWI and for the possibility of quantifying the variation in magnetic susceptibility in brain tissue[

27]. In this context, QSM could represent a potential auxiliary tool in early diagnosis and longitudinal monitoring of damage evolution, for instance by correlating the obtained data with blood bilirubin levels, but further studies are needed.

From a clinical point of view our patient exhibited long-term sequelae, including hearing loss and motor impairment. This underscores the critical importance of not only monitoring bilirubin levels in neonates during hospitalization and after discharge—particularly in the presence of risk factors such as maternal-neonatal ABO incompatibility—but also ensuring close neuroimaging follow-up, even after the resolution of clinical and laboratory abnormalities. In our case, MRI performed at one and two months of age detected only slight T1 hyperintensity within the hippocampi bilaterally, while the last follow-up neuroimaging at six months of age revealed T2 hypersignal within both globi pallidi and tissue loss in the hippocampi, a neuroimaging hallmark of chronic bilirubin encephalopathy.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, it is important to emphasize that even in the absence of detectable injury on the first MRI study, close clinical and radiological follow-up is essential to identify neurological damage in the brain regions typically affected by kernicterus. In fact, even in the absence of significant clinical symptoms or in the presence of non-specific findings, as often occurs, the detection of these alterations allows to implement an early neuro-rehabilitative management with the aim of reducing morbidity rate and long-term complications related to neurotoxicity, thereby promoting optimal neurodevelopment. This case highlights the complexity of bilirubin-induced neurotoxicity and the limitations of current therapeutic approaches in preventing kernicterus, even with prompt management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P., M.R., A.R., L.A.R. and A.C.; methodology, A.P., M.R., and A.C.; forma! analysis, A.P .. and A.C.; investigation, A.P., M.R., D.T., A.R. and A.C.; resources, L.A.R. and A.C.; data curation, A.P., M.R., A.R., L.A.R. and A.C .. ; writing-original draft preparation, A.P., M.R., D.T., and A.C.; writing-review and editing, A.R., and L.A.R.; visualization, M.R., D.T., and A.R.; supervision, A.R., L.A.R. and A.C.; project administration, A.C.; funding acquisition, L.A.R. and A.C. Ali authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by an IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini research grant [UAUT (2022_258_0)]. No other funding was received.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in compliance with the terms of the Helsinki Declaration and written informed consent for the enrolment and for the publication of individual clinical details was obtained from parents. In our country, namely Italy, this type of clinical study does not require Institutional Review Board/Institutional Ethics Committee approval to publish the results.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of the subject involved in the present study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data sets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini for the support given in several steps leading to the publication of the present study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MRS |

Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy |

| NICU |

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit |

| NAA |

N-Acetylaspartate |

| SWI |

Susceptibility Weighted Imaging |

| ABR |

Auditory brainstem response |

| EEG |

Electroencephalogram |

| VEP |

Visual Evoked Potentials |

| AGA |

Average for Gestational Age |

| QSM |

Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping |

References

- B. O. Olusanya, M. Kaplan, and T. W. R. Hansen, “Neonatal hyperbilirubinaemia: a global perspective,” Lancet Child Adolesc Health, vol. 2, no. 8, pp. 610–620, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Wolf et al., “Exchange transfusion safety and outcomes in neonatal hyperbilirubinemia,” J Perinatol, vol. 40, no. 10, pp. 1506–1512, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Ü. Sarici et al., “Incidence, course, and prediction of hyperbilirubinemia in near-term and term newborns,” Pediatrics, vol. 113, no. 4, pp. 775–780, Apr. 2004. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Maisels, J. F. Watchko, V. K. Bhutani, and D. K. Stevenson, “An approach to the management of hyperbilirubinemia in the preterm infant less than 35 weeks of gestation,” J Perinatol, vol. 32, no. 9, pp. 660–664, Sep. 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Huang, K. E. Kua, H. C. Teng, K. S. Tang, H. W. Weng, and C. S. Huang, “Risk factors for severe hyperbilirubinemia in neonates,” Pediatr Res, vol. 56, no. 5, pp. 682–689, Nov. 2004. [CrossRef]

- R. Kemper et al., “Clinical Practice Guideline Revision: Management of Hyperbilirubinemia in the Newborn Infant 35 or More Weeks of Gestation,” Pediatrics, vol. 150, no. 3, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kasirer, M. Kaplan, and C. Hammerman, “Kernicterus on the Spectrum,” Neoreviews, vol. 24, no. 6, pp. E329–E342, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Assefa Neknek, K. Woldemichael, A. Moges, and D. Zewdneh Solomon, “MRI of bilirubin encephalopathy (kernicterus): A case series of 4 patients from Sub-Saharan Africa, May 2017,” Radiol Case Rep, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 676–679, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- V. K. Bhutani and L. Johnson, “Kernicterus in the 21st century: frequently asked questions,” J Perinatol, vol. 29 Suppl 1, pp. S20–S24, 2009. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Shapiro, “Definition of the clinical spectrum of kernicterus and bilirubin-induced neurologic dysfunction (BIND),” J Perinatol, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 54–59, Jan. 2005. [CrossRef]

- S. Sugama, A. Soeda, and Y. Eto, “Magnetic resonance imaging in three children with kernicterus,” Pediatr Neurol, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 328–331, 2001. [CrossRef]

- K. Yokochi, “Magnetic resonance imaging in children with kernicterus,” Acta Paediatr, vol. 84, no. 8, pp. 937–939, 1995. [CrossRef]

- J. Gburek-Augustat et al., “Acute and Chronic Kernicterus: MR Imaging Evolution of Globus Pallidus Signal Change during Childhood,” AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, vol. 44, no. 9, pp. 1090–1095, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. K. Bhutani and L. Johnson, “Synopsis report from the pilot USA Kernicterus Registry,” J Perinatol, vol. 29 Suppl 1, pp. S4–S7, 2009. [CrossRef]

- F. Okolie, J. E. South-Paul, and J. F. Watchko, “Combating the Hidden Health Disparity of Kernicterus in Black Infants: A Review,” JAMA Pediatr, vol. 174, no. 12, pp. 1199–1205, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Okumura et al., “Kernicterus in preterm infants,” Pediatrics, vol. 123, no. 6, Jun. 2009. [CrossRef]

- E. Bertino et al., “Neonatal anthropometric charts: the Italian neonatal study compared with other European studies,” J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, vol. 51, no. 3, pp. 353–361, Sep. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Y. W. Wu et al., “Risk for cerebral palsy in infants with total serum bilirubin levels at or above the exchange transfusion threshold: a population-based study,” JAMA Pediatr, vol. 169, no. 3, pp. 239–246, Mar. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Wisnowski, A. Panigrahy, M. J. Painter, and J. F. Watchko, “Magnetic resonance imaging of bilirubin encephalopathy: current limitations and future promise,” Semin Perinatol, vol. 38, no. 7, pp. 422–428, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Gburek-Augustat et al., “Acute and Chronic Kernicterus: MR Imaging Evolution of Globus Pallidus Signal Change during Childhood,” AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, vol. 44, no. 9, pp. 1090–1095, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhang, J. Gao, Y. Zhao, Q. Zhang, J. Lu, and X. Yang, “The application of magnetic resonance imaging and diffusion-weighted imaging in the diagnosis of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy and kernicterus in premature infants,” Transl Pediatr, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 958–966, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang et al., “Studying neonatal bilirubin encephalopathy with conventional MRI, MRS, and DWI,” Neuroradiology, vol. 50, no. 10, pp. 885–893, Oct. 2008. [CrossRef]

- M. Lequin, F. Groenendaal, J. Dudink, and P. Govaert, “Susceptibility weighted imaging can be a sensitive sequence to detect brain damage in neonates with kernicterus: a case report,” BMC Neurol, vol. 23, no. 1, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Liu, W. Li, K. A. Tong, K. W. Yeom, and S. Kuzminski, “Susceptibility-weighted imaging and quantitative susceptibility mapping in the brain,” J Magn Reson Imaging, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 23–41, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. B. Salmela et al., “All that bleeds is not black: susceptibility weighted imaging of intracranial hemorrhage and the effect of T1 signal,” Clin Imaging, vol. 41, pp. 69–72, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. C. T. Hsu et al., “More on Exploiting the T1 Shinethrough and T2* Effects Using Multiecho Susceptibility-Weighted Imaging,” American Journal of Neuroradiology, vol. 42, no. 9, pp. E62–E63, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. P. R. Ruetten, J. H. Gillard, and M. J. Graves, “Introduction to Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping and Susceptibility Weighted Imaging,” Br J Radiol, vol. 92, no. 1101, 2019. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).