Introduction

In recent years, there has been a growing emphasis on the meaningful involvement of autistic people in research, with participatory research increasingly recognised as best practice or the gold standard (Le Cunff et al., 2023; Fletcher-Watson et al., 2021). Some autism journals now require reporting on autistic involvement (Tan et al., 2024; Fletcher-Watson, 2021; Nicolaidis et al., 2019), and co-production is gaining funding support (Pickard et al., 2022).

However, achieving true and meaningful participation remains challenging. It is an iterative process that requires ongoing reflection and learning from researchers’ experiences over time. This is particularly difficult for early-career autism researchers, for whom participatory research is still a relatively new and often unfamiliar approach (Pickard et al., 2022). While many researchers are enthusiastic about involving autistic people, they often lack the necessary expertise, support, and resources to do so effectively (Fletcher-Watson et al., 2019).

To address this gap in experience and transparency, the current study aimed to develop and validate evaluation tools that support researchers in fostering meaningful participation of autistic people throughout the research process.

To understand the challenges of participatory research in autism, it is important to first examine the historical context and power imbalances that have shaped autism research.

Challenges of participatory research

Despite its potential, the application of participatory approaches in autism research is still developing and faces several significant challenges. Some of these challenges are discussed in the next section.

- 1)

Perceptual misalignment of what participation is

One key challenge is the discrepancy in how researchers and the autistic community perceive participatory research. In a large-scale questionnaire study (n= 1,516), Pellicano, Dinsmore, and Charman (2014) found that while researchers considered themselves to be engaged in participatory research, the autistic community did not share this view. This could be addressed through the development of guidelines to clarify what meaningful participation looks like.

- 2)

Lack of Understanding of Meaningful Participation

Another challenge is the limited understanding of what constitutes meaningful participation among researchers. Den Houting et al. (2020) found that when researchers were asked to define participation, they often described consultation in terms of ‘being involved in an advisory capacity’ (p. 458) rather than genuine collaboration. Additionally, Roche et al. (2021) highlighted that autistic individuals are not involved as research partners as frequently as professionals, parents, or carers. Den Houting et al. (2020) argue that more training, support, and funding are needed to promote genuine participatory approaches.

- 3)

Mismatch Between Research Priorities

It is crucial that autism research aligns with topics that the autistic community considers relevant and important. However, studies indicate a significant gap between the research being conducted and the research priorities of the autism community (Pickard et al., 2022; Den Houting & Pellicano, 2019; Pellicano, Dinsmore & Charman, 2014). Roche et al. (2021) argue that greater efforts are needed to involve autistic individuals in setting research priorities.

- 4)

Inconsistencies in Participatory Research Practices

Although there are examples of successful participatory research in autism studies (e.g., Le Cunff, 2023; Pavlopoulou, 2021; Stark et al., 2021; Lam et al., 2020; Crane et al., 2019), research has shown considerable variation in how participation is designed and reported. For participatory approaches to be meaningful and to address stigma within autism research (Kaplan-Kahn & Caplan, 2023), active involvement should be evident throughout all research stages (Den Houting et al., 2021; Garfield & Yudell, 2019).

However, a scoping review by Jivraj et al. (2014) found that only a small proportion of studies consistently engaged neurodivergent individuals throughout the research process. However, it should be acknowledged that Jivraj et al.’s scoping review had strict criteria which resulted in the inclusion of only a very small number of studies detailing the involvement of community partners. Den Houting et al. (2021) reported that participation was most common during the middle stages of research (e.g., study design) but less so in the early (e.g., grant proposals) and later stages (e.g., data analysis and dissemination). Similarly, Pellicano et al. (2014a, 2014b) found that opportunities for autistic individuals to engage beyond dialogue and dissemination were rare. This highlights the need for clear guidance to support researchers in adopting participatory approaches throughout each and every step of the research.

Existing good practice guidelines around PAR

One of the primary obstacles to the widespread adoption of participatory approaches in autism research is a lack of understanding around how to operationalise it effectively and meaningfully (Pickard et al., 2022) and the lack of clear guidelines and advisory frameworks to assist researchers in effectively implementing this approach (Fletcher-Watson et al., 2019; Jivraj et al., 2014). Den Houting et al. (2021) gathered the views of academic researchers and community members and found they were supportive of participatory research, but they did not have a deep understanding of it and some of their views around the implementation of participatory approaches, for example in relation to power, may not support meaningful engagement.

These findings underscore the necessity for a standardised evaluative framework to better assess the contributions and outcomes of partnerships with autistic individuals. Without such a framework, there is a risk that participatory approaches will be underutilised or applied in a superficial manner, failing to achieve its full potential in transforming autism research (Pellicano, Dinsmore, & Charman, 2014).

Arnstein’s ladder is an invaluable tool to support assessment of power to make decisions within participatory approaches, previously found to be lacking within research in the autism community (Fletcher-Watson et al., 2019; Pellicano et al., 2014a, 2014b). The ladder is split into three levels with manipulation at the bottom, tokenism in the middle and citizen power at the top, which meaningful participation should aspire to. Fletcher-Watson et al. (2019) found that autism research often sits in the bottom half of the ladder and is, at best, tokenistic. To address this, Den Houting et al. (2021) redesigned Arnstein’s ladder for use in academic settings specifically with the autistic community and renamed the three domains with ‘doing to’ at the bottom, ‘doing for’ in the middle and ‘doing with’ at the top. However, critics argue that the Arstein’s Ladder oversimplifies the complexities of participation and the linear, rigid structure suggests that one can simply "move up" the ladder, but in practice, participation might shift across various levels depending on context, issues, and the actors involved (Cornwall, 2008). Additionally, although influential, this broad framework does not give specific guidelines on how participation can be implemented within research.

There has been some valuable work in creating guidelines for meaningful participation in autism research (e.g., Nicolaidis et al., 2019; Gowen et al., 2019; Dark, 2024). Whilst some provide a broad framework for ethical and inclusive research practices (i.e. Dark, 2024), they lack specific guidance on how to operationalise these principles in different research contexts. This makes it difficult for researchers - especially those unfamiliar with participatory approaches - to apply these principles in a meaningful way. Building on good practice guidelines, (e.g., Gowen et al., 2019; Nicolaidis et al., 2019) to establish a clear sequence of steps to follow when designing an inclusive study will enable researchers to evaluate the effectiveness, impact, and success of including autistic people in research. More detailed and structured guidelines are essential to provide a practical, clear and systematic sequence of steps for ensuring the inclusion of autistic people across different research stages, to address power imbalances and ensure autistic individuals have meaningful influence in decision-making. They would also offer methodological adaptations for engaging underrepresented groups, particularly nonspeaking autistic individuals, outline clear accommodations to remove participation barriers, including sensory and communication adaptations, standardise language and framing to align with autistic self-advocacy perspectives and ensure accessible dissemination of research findings to both academic and non-academic audiences.

Building on the need for structured and actionable guidelines, The Autism Co-productive Research Centre (Autism Cooperative Research Centre for Living with Autism) (2016) produced a range of Inclusive Research Practice Guides. These guidelines include a checklist for good practice in supporting Participation in Research for Individuals on the Autism Spectrum (Checklist 5) which utilises a 3 point checklist to promote the involvement of participants, mutual respect, equality, communication, environment and inclusion. This is a useful checklist to provide a broad overview of participation but lacks specific strategies for power sharing, accessibility, compensation and reflective practice.

By providing researchers with clear, actionable guidance around how to operationalise participatory research, the research community can ensure that participatory research is implemented in a way that truly reflects the principles of equal collaboration and inclusion across all stages of the research process. This would not only enhance the quality and relevance of autism research but also build trust between researchers and the autistic community, fostering a more equitable and productive research environment.

With this in mind, the aim of this project was to develop and carry out initial steps to validate tools to;

It is proposed that these tools will aid researchers adopting PAR approaches and in promoting best practice in autism research. Specifically, it is envisaged that these tools will;

Promote and provide specific guidance around the meaningful inclusion of autistic people throughout the research process, from conception of an idea through to dissemination of results (ELPART).

Aid transparency in how and to what extent autistic people are involved throughout the research process and in decision making (Jivraj et al. 2014), promoting the fair acknowledgement of autistic people’s views (PAR group checklist and ELPART).

Aid reflection and learning at all stages of the research process (ELPART).

Address power dynamics inherent in autism research (PAR group checklist and ELPART).

Positionality

Authors represent diverse neurotypes and have extensive experience in neurodiversity research and advocacy. The PAR group consists of current postgraduate students and a postdoctoral academic having varying experiences of diagnosis. Some received autism diagnoses in childhood and others in adulthood. Two authors are mothers of autistic children and are deeply committed to empowering autistic individuals. One author, a widening participation lead, has experience of anti racism work and anti oppressive pedagogies, within a university setting. While authors represent diversity in terms of age, the majority identify as female and there is over representation from white perspectives. Our perspectives are shaped by the neurodiversity paradigm (Singer, 2016) and the principle of ‘Nothing About Us Without Us.’

Participants

Four members of the PAR group of autistic students and recent graduates, carried out initial steps towards validation. Initially, the lead author established this group to guide and inform wider PhD research. These group members were employed as research assistants (hereafter referred to as community researchers) to lead initial validation activities.

Additionally, the study recruited five academics, PhD researchers and charity employees (hereafter referred to as participatory researchers. The recruitment aimed to ensure diverse career stages (i.e., early career and established researchers) and to recognise power dynamics that may exist between junior and senior researchers (Muhammad et al., 2015). Three participants had extensive experience in participatory research with neurodivergent individuals. One PhD researcher had recently formed a participatory group of autistic people to guide their study, and one participant, a Senior Development Officer in a charity, had extensive experience working in participatory settings with autistic adults and those with learning disabilities.

All participants contributed as authors of this article.

Procedure

In 2021, the lead author formed a PAR group to guide and inform her PhD research on autistic undergraduate students' mental health experiences at university. This group, comprising seven current and former students, has been involved since the project's inception. Over time, the lead author and the PAR group developed methods and approaches to ensure full and meaningful participation (see Horton et al., 2024, 2025). Throughout this process, the lead author reflected on challenges and barriers to participation, continuously adapting the research to align with best practices. Her 30 years of experience in participatory frameworks spanning advocacy, service, and collaborative research shaped the development of the evaluation tools.

The lead author initially sent the draft tools to the PAR group for feedback. Following this, she successfully obtained Spotlight funding, allowing four PAR group members to be recruited as community researchers to lead validation activities. Their primary role involved evaluating the construct and content validity of the tools over a four-month period.

Validation Process

The study focused on testing initial steps to validation and in particular construct validity, which assesses whether a tool measures the intended concept (Robson, 2011). One approach to testing construct validity is face validity, which ensures the tool appears appropriate and understandable to intended users (Haynes, Richard & Kubany, 1995). This validation method also checks for clarity in wording and comprehensibility. The research team conducted focus groups and interviews with community researchers and participatory researchers to assess face validity.

To strengthen the evaluation, the study also examined content validity, which assesses whether the tool fully captures the targeted domain (Hinkin, 1995). The community and participatory researchers evaluated whether the tools addressed key challenges to autistic participation.

Initial and ongoing meetings were held between the lead researcher and community researchers to brief them on the tools and to discuss a plan for validation. As community researchers were studying at postgraduate level, they had experience of carrying out research, so no immediate training needs were identified, but ongoing support was offered by the lead researcher and flexibility was offered in terms of hours worked and any adjustments needed to promote engagement. Community researchers initially carried out a literature review to check that the tools aligned with relevant themes identified from literature and addressed barriers and challenges to participation. We recognise validity may vary in meanings and practice across qualitative and quantitative contexts. This project focused on the first steps to validation, focusing on construct, including face validity and content validity with each group (participatory researchers and community researchers) examining the tools to see if items overlapped (construct validity), if anything was missing (content validity) or needed rewording for clarification (face validity). This was done through the following activities;

Two initial one hour focus groups were held amongst the four community researchers to discuss the tools and changes needed. Due to the group being located in different parts of the UK, participants previously opted for online meetings. Focus groups/interviews were recorded and transcribed and suggested amendments were collated for each item. Changes to the tools were implemented by the lead researcher to reflect these discussions. After making these amendments, the updated tools were sent to the group to approve or discuss further changes.

Two, one hour meetings were then held with the group of participatory researchers, both of which were chaired by community researchers. Focus groups/interviews were recorded and transcribed and suggested amendments were collated for each item. Following each of these meetings, changes were made to reflect these discussions. Finally, a meeting was held with the community researchers to discuss the changes suggested by the participatory researcher group and to address outstanding suggestions.

Results

This section presents findings from the validation exercises conducted on the Evaluating Levels of Participation in Autism Research Tool (ELPART) and the PAR Group Checklist. The validation process followed a structured sequence, beginning with feedback from autistic community researchers and academic researchers. This feedback guided modifications that improved clarity, applicability, and usability.

The results are organised as follows:

ELPART Validation Exercise – This section outlines the evaluation of ELPART, including discussions on the scoring system, construct, face, and content validity, and key modifications made to enhance its effectiveness.

PAR Group Checklist Validation Exercise – This section details how the checklist was refined based on feedback, with particular focus on ensuring accessibility, flexibility, and applicability across different participatory settings.

Finalised tools and rationale.

Validation exercise - ELPART

Scoring system

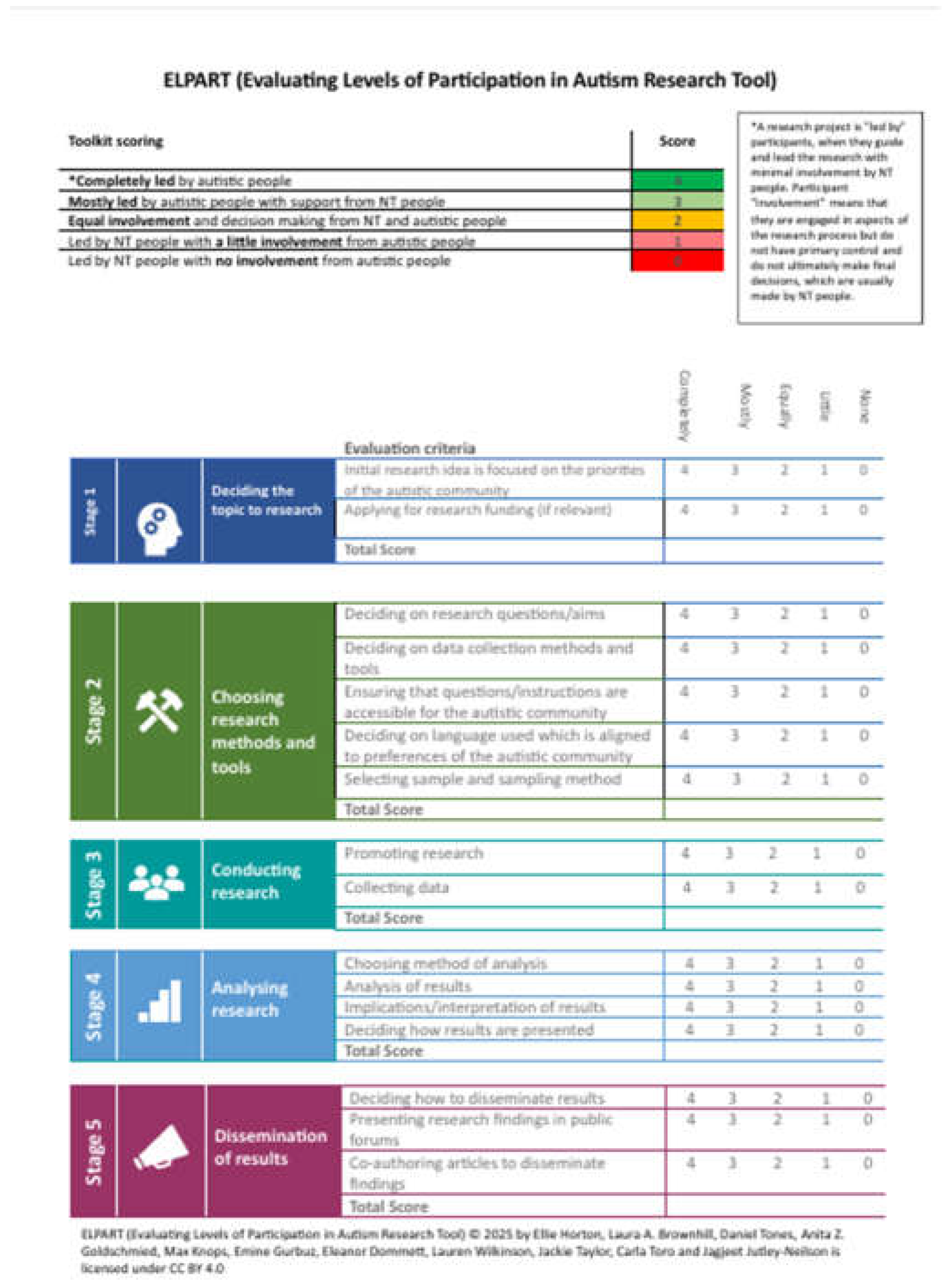

We have added discussions around the scoring system here because it is important to understand whether the likert scale response items are sensitive enough to measure participation. Community researchers recommended a 5-point scale to better capture decision-making power. A final score was omitted to avoid reducing participation to a checklist.

To enhance the flexibility and relevance of the tools, researchers made key modifications to ensure their applicability across a wider range of research methods. For example, researchers discussed changes to the tools to ensure applicability across a broader range of research methods beyond questionnaires or interviews to incorporate clinical trials. Questions were reworded to reflect this wider application, for example, ‘Disseminating questionnaires’ and ‘Carrying out interviews/focus groups’ were changed to ‘Promoting research’ and ‘Collecting data’.

Within

Table 1 and

Table 2 below we present the findings from the ELPART validation process based on feedback from both community researchers and academic researcher groups. Validation focused on construct, including face validity and content validity and each group examined the tools to see if items overlapped (i.e. construct validity), if anything was missing (i.e. content validity) or needed rewording for clarification (i.e. face validity).

Key points and actions from discussions with the community researchers and researchers are outlined within the tables below.

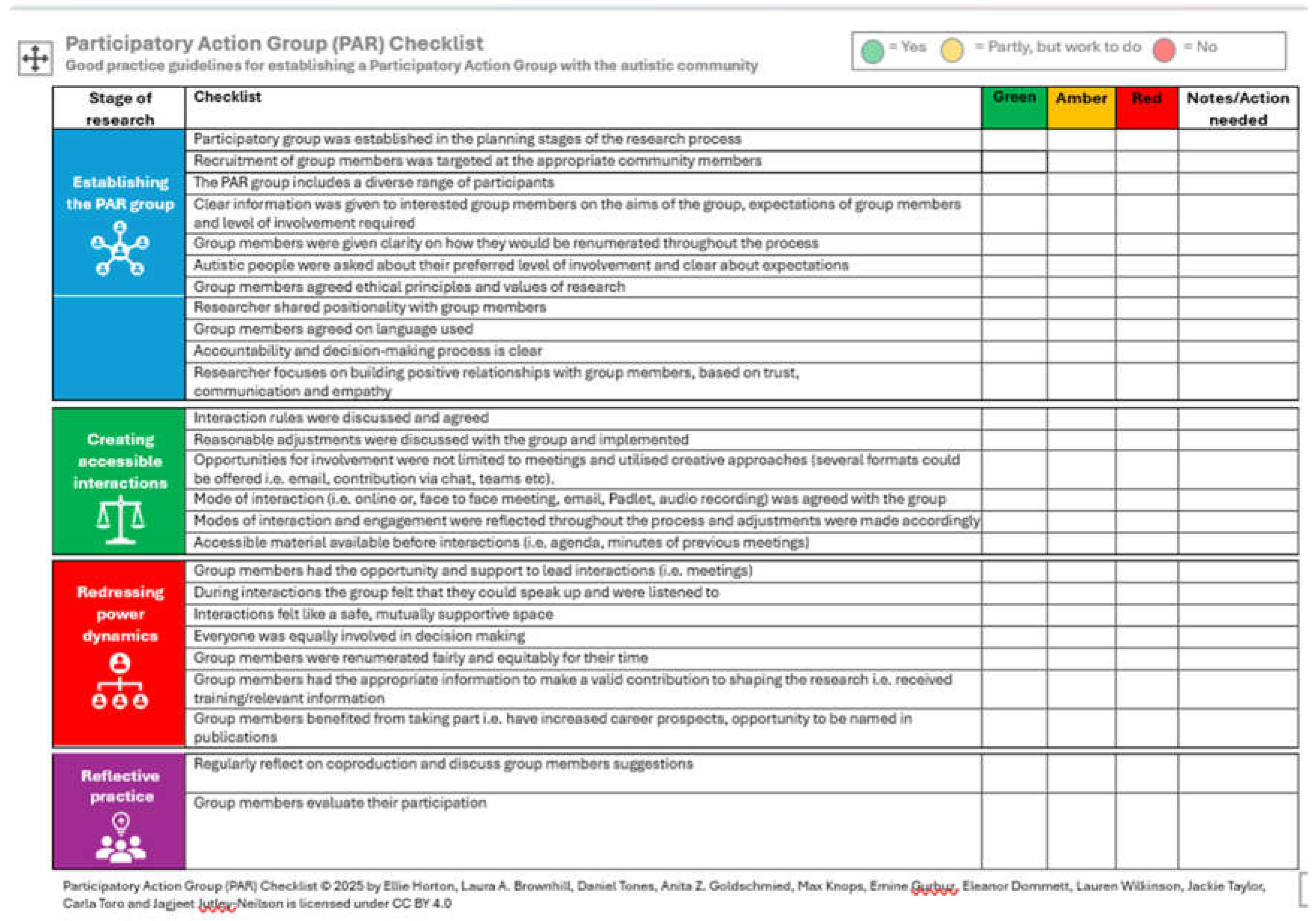

Validation exercise - PAR group checklist

Initially the group discussed the appropriateness of the scoring system. We agreed that a three point scoring was appropriate for this tool so an amber, green, red scoring for this tool with a notes/action column for researchers to highlight any actions needed, was agreed. A three point scaleensures that the tool is simple and easy to use (De Von et al., 2007), less ambiguous (Norman, 2010), forces clear differentiation between levels (Tourangeau et al., 2000) and could result in more actionable results (Patton, 2008). The 3-point scale helps researchers quickly identify weaknesses and take corrective action.

Key points and actions from discussions with the community researchers and researchers are outlined within the tables below.

The ELPART and PAR Group Checklist were developed to address the gaps in skills, support, and resources that have been well-documented in participatory autism research (Pickard et al., 2022; Fletcher-Watson et al., 2019; Jivraj et al., 2014). These tools provide structured evaluative frameworks designed to promote best practices in participatory approaches while addressing power imbalances inherent in autism research (Den Houting et al., 2021; Nicolaidis et al., 2019; Rose, 2018).

The ELPART

Historically, autistic people have been subjected to stigmatising and deficit-based discourses in research (Bottema-Beutel, 2023; Rauchberg, 2022; Williams & Gilbert, 2020). One way to counteract this is by ensuring autistic individuals are equal partners in research (Kaplan-Kahn & Caplan, 2023). Meaningful participation involves engaging autistic people throughout all stages of research (Kaplan-Kahn & Caplan, 2023; Den Houting et al., 2021; Garfield & Yudell, 2019), yet active research partnerships remain rare. Studies have identified discrepancies between researchers' perceptions of engagement and autistic participants’ actual involvement (Pellicano et al., 2014a, 2014b). Den Houting et al. (2021) found that autistic engagement was most common in the middle stages of research (e.g., study design) but significantly less so in the early (grant proposals) and later stages (data analysis and dissemination). The ELPART tool helps to address these issues by systematically evaluating autistic participation across five key research stages, providing clarity and accountability regarding involvement (Jivraj et al., 2014).

Scale

Each research stage in ELPART is assessed using a five-point scale, allowing researchers to evaluate the extent of autistic involvement using the following criteria:

Please see the finalised ELPART below.

Stage 1: Deciding the Research Topic

Autistic people should be involved as early as possible, ideally in deciding the research focus. This stage includes two evaluation criteria:

This stage addresses a long-standing issue in autism research - the gap between research priorities identified by the autistic community and the research actually conducted (Pickard et al., 2022; Den Houting & Pellicano, 2019; Pellicano et al., 2014a, 2014b). As Kaplan-Kahn & Caplan (2023) state:

“Our lived experiences color and shape the questions and hypotheses we generate to learn more about autism” (p. 2).

However, challenges remain in involving autistic people in grant applications due to academic barriers (Fletcher-Watson et al., 2019). To address this, our guidance encourages researchers to engage with autistic communities through social media or previous research (e.g., Roche et al., 2021) to align topics with community priorities. A validation team member described how they have used social media polls to determine the research priorities of the autistic community, demonstrating a practical strategy for engagement.

Stages 3 & 4: Conducting and Analysing Research

These stages ensure that research is conducted in an inclusive way and that autistic insights shape data analysis. Evaluation criteria at stage 3 includes;

- 1)

Promoting research

- 2)

Collecting data.

Inclusion at this stage can ensure that research reaches under-represented communities. Kaplan-Kahn & Caplan (2023) advocate for autistic involvement in data collection (e.g., conducting interviews), as this can increase research relevance and impact and enhance validity by ensuring accurate interpretations of autistic communication styles.

Stage 4 evaluation criteria includes;

- 1)

Choosing method of analysis

- 2)

Analysis of results

- 3)

Implications/interpretations of results

- 4)

Deciding on how results are presented.

Autistic strengths—such as hyperfocus, creativity, and monotropic attention—can be advantageous in research, particularly in data coding and analysis (Grant & Kara, 2021).

Stage 5: Dissemination of Results

In keeping with Community Action Research principles, involving autistic individuals in dissemination maximises community impact and drives change (May, 2024; Horton et al., 2024). ELPART evaluates:

Deciding how to disseminate results.

Presenting research findings in public forums.

Co-authoring research articles.

Ensuring autistic co-authorship promotes equitable recognition and skill development, enhancing employability and ensuring autistic people directly benefit from research participation (Nicolaidis et al., 2019). Findings should be disseminated in ways that minimise stigma and align with community priorities (Nicolaidis et al., 2019).

PAR Group Checklist

The PAR Group Checklist provides good practice guidelines for establishing a participatory action group with the autistic community. It is important to note that used alone it does not measure participation perse, but can be used in conjunction with the ELPART to do this. It uses a three-point rating scale (Green = Yes, Amber = Partly, Red = No) to assess participatory practices across four stages: Establishing the PAR group, Creating accessible interactions, Redressing power dynamics and Reflective practice.

Please see the finalised PAR group checklist below.

Figure 2.

PAR group checklist.

Figure 2.

PAR group checklist.

Establishing the PAR group

The first stage of the PAR Group Checklist focuses on establishing the participatory action research (PAR) group. Ideally, this should occur during the planning stages of the research process to ensure meaningful engagement (Den Houting et al., 2021; Garfield & Yudell, 2019) and promote early involvement in defining research aims and objectives. As discussed earlier in relation to Stage 1 of the ELPART tool, early engagement is crucial for ensuring research aligns with autistic priorities.

Recruitment should be targeted to ensure that group members possess relevant expertise and lived experience aligned with the research focus (Pickard et al., 2022; Nicolaidis et al., 2019). For instance, in our research exploring the mental health experiences of autistic university students, we deliberately recruited recent graduates with lived experience of the challenges faced by this demographic (Horton et al., 2025). However, there may be circumstances where neurotypical input is also required, such as in comparison studies. In such cases, good practice guidelines to accompany the tools will clarify how both autistic and neurotypical perspectives will be integrated meaningfully.

It is equally important to ensure diverse representation within the PAR group, reflecting the broader autistic population (McNally et al., 2015). Research highlights the underrepresentation of marginalised groups, including LGBTQ+ individuals and autistic people from ethnic minority backgrounds (Fletcher-Watson et al., 2019; Dark, 2024; NHS England, 2023). However, reaching these communities can be challenging. Pickard et al. (2019) suggest partnering with relevant organisations, such as charities, to support inclusive recruitment efforts.

Clarity and transparency are essential for building trust and ensuring meaningful participation (Nicolaidis et al., 2019). Prospective group members should receive clear information regarding: the aims of the group and its role within the research project, expectations of group members and levels of involvement required. Clarity should also be given around compensation and reimbursement for participation.

Autistic individuals should have autonomy in deciding their preferred level of engagement, and expectations should be made explicit from the outset. A lack of clarity in how autistic perspectives shape decision-making has previously resulted in exclusion and frustration (Jivraj et al., 2014). This lack of transparency is widespread in participatory research (Fletcher-Watson et al., 2019) and can undermine trust, leading to disengagement and dissatisfaction among group members (Nicolaidis et al., 2019). Establishing clear expectations from the start can prevent these issues, even if group members are only involved in certain aspects of the project.

Ethical principles should also be agreed upon collaboratively to ensure that research aligns with the values and priorities of the autistic community. Researchers should share their positionality, acknowledging their biases and the inherent power dynamics in the research process. This transparency fosters a more open and honest environment, allowing for authentic collaboration between autistic and non-autistic researchers.

The language used to describe autism remains a contested issue, often signaling power imbalances between researchers and the autistic community. Autistic individuals have historically been subjected to stigmatising, deficit-based language imposed by others (Bottema-Beutel, 2023; Rauchberg, 2022). Research shows that many autistic individuals prefer identity-first language (e.g., "autistic person" rather than "person with autism") (Kenny et al., 2016). However, perspectives on terminology vary, and no universally accepted definition of autism exists (Kenny et al., 2016). Therefore, group members should collectively establish preferred language guidelines to ensure research terminology aligns with community preferences (Dark, 2024; Nicolaidis et al., 2019).

Strong relationships between researchers and community members are critical in participatory research (Pickard et al., 2022; Den Houting et al., 2021). These relationships require time and effort to build, with an emphasis on trust, mutual respect, and clear communication. Effective strategies for fostering collaboration include: encouraging open dialogue and active listening, providing opportunities for feedback and addressing concerns constructively, recognising and celebrating contributions and engaging in reflective practice to continuously improve research processes (Nicolaidis et al., 2019).

Honest communication is foundational to successful participatory research (Redman et al., 2021) and directly impacts relationships between researchers and group members (Hollins & Pearce, 2019). Milton’s (2012) Double Empathy Problem suggests that communication difficulties between autistic and non-autistic people stem from bi-directional misunderstandings, rather than a deficit in autistic communication. Researchers must therefore be mindful of their own communication styles, ensuring they are clear, concise, and adaptable to group members' needs.

Creating Accessible Interactions

Ensuring accessible participation is key to promoting the full participation of autistic people in participatory research (Horton et al., 2024; Schwartz et al., 2020; Fletcher-Watson et al., 2019). However, research shows that less than half of autistic participants receive reasonable adjustments in participatory research (Den Houting et al., 2021). Autistic individuals with learning disabilities or limited verbal communication remain underrepresented (Fletcher-Watson, 2019), making it essential to adopt appropriate methods that support diverse participation needs. Given the heterogeneous nature of the autistic community, research processes should be adapted to fit individual strengths, challenges, and preferences. As Rauchberg (2022) states, participatory research should "bend toward the [PAR group member’s] skill set" (p. 380). Key considerations include: Flexible modes of engagement (e.g., online meetings, email contributions, chat-based discussions), providing accessible materials in advance (e.g., agendas, meeting notes) and adapting communication formats to suit individual needs (e.g., written over spoken interactions). For example, in our PAR group for PhD research on autistic university students' mental health, meetings were held online, but some participants preferred to engage via email or contribute through chat rather than speaking. These preferences were continually reassessed throughout the research process to accommodate changing needs.

Redressing Power Imbalances

To ensure equitable participation, group members should have the opportunity to lead interactions (e.g., facilitating meetings, shaping discussions) should they wish to. Autistic engagement levels should be flexible, allowing participants to adjust their involvement as needed. During interactions, it is critical that the group feel they can speak up and are listened to and that interactions feel like a safe, mutually supportive space (Horton et al., 2024). As outlined above, everyone should be equally involved in decision making.

Compensation is a crucial factor in addressing power imbalances. Despite this, 42% of community partners in participatory autism research report not receiving payment for their time (Den Houting et al., 2021). Compensation should be equivalent to researcher or research assistant pay where possible, reinforcing the value of autistic contributions. However, institutional constraints such as university funding regulations and restrictions can create barriers to direct payment. In our case, the PhD researcher sought additional funding to employ autistic participants as research assistants, ensuring fair compensation.

Beyond financial remuneration, involvement in participatory research should provide tangible benefits, such as: Career development opportunities and co-authorship on publications (Nicolaidis et al., 2019). While some autistic individuals may not have an interest in academic careers, their perspectives remain essential for ensuring research is inclusive and representative and participation offers an opportunity to develop transferable skills (Nicolaidis et al., 2019).

Ongoing Reflection and Evaluation

Participatory research should be viewed as an ongoing effort, rather than a fixed goal. As Milton et al. (2019) argue:

“Striving for participation and co-production can never be perceived as a given or a fully accomplished outcome” (p. 87).

Self-reflection and continuous evaluation are essential for identifying weaknesses and improving engagement strategies (Kindon, Pain, & Kesby, 2007). Regular feedback from group members can inform adjustments to enhance participatory experiences (Nicolaidis et al., 2019).

By maintaining reflective, adaptable, and inclusive practices, the PAR Group Checklist ensures that participatory autism research is meaningful, ethical, and impactful.

Discussion

Both the ELPART and the PAR Group Checklist provide structured frameworks to support ongoing reflection and assessment of participatory autism research and are designed to use at the start of a project to guide good practice, rather than to assess coproduction at the end. Developed through co-production with the autistic community and experienced participatory researchers, these tools prioritise accessibility, usability, and practical application. They enable researchers to evaluate the effectiveness of participatory methods, highlighting both areas of strength and opportunities for improvement.

THE ELPART

The validation process led to several refinements, particularly in clarifying scoring criteria and ensuring the tool's applicability to diverse research methods.

A key feature of ELPART is its five-point scale, making it the first known tool to systematically assess autistic involvement across five critical research stages: Deciding the research topic, Selecting methods and tools, Conducting research, Analysing findings, and Disseminating results. The five-point Likert scale allows for a nuanced assessment of participation, but care must be taken to avoid rigid scoring interpretations that reduce participation to a checklist exercise.

By explicitly measuring decision-making power, ELPART provides a mechanism to identify and address power imbalances, ultimately fostering more equitable and meaningful autistic participation throughout the research process. Ensuring autistic individuals are involved from the earliest stages (e.g., grant applications and research design) is crucial for avoiding tokenism. Finally, the tool can be adapted across different types of research, including qualitative studies, clinical trials, and mixed-methods approaches.

The ELPART has several implications for Participatory Research. Firstly, it allows for greater transparency in how autistic individuals are engaged at each research stage which will challenge traditional power imbalances in autism research. Secondly, it improves accountability through structured reflection which could help funders and institutions assess participatory research quality more systematically.

The PAR Group Checklist was designed to evaluate best practices for establishing and supporting participatory action research (PAR) groups with autistic individuals. The validation process highlighted the need for clarity around power-sharing, decision-making, and accessibility.

The three-point rating system (green, amber, red) provides a clear and simple assessment tool, making it practical for researchers including those at early stages of their career and those new to participatory research. Researchers should consider the emphasis on ongoing relationship-building rather than one-time assessment as this is essential for meaningful engagement.The tool is adaptable to different interaction formats (e.g., online meetings, asynchronous participation, written vs. verbal communication).

The PAR group checklist has several implications for Participatory Research. Firstly, by ensuring fair remuneration and accessibility, the checklist directly addresses systemic barriers that autistic co-researchers face in academic settings.The emphasis on reflective practice encourages researchers to continually refine their participatory methods, rather than perceiving engagement as static. Finally, encouraging autistic leadership and decision-making throughout the research process empowers the community rather than reinforcing traditional research hierarchies.

Broader Impact on Participatory Research

This evaluation framework underscores the broader challenges and opportunities in embedding participatory research principles into autism studies. While participatory research is increasingly recognised as best practice, researchers often lack structured guidance on implementation (Pickard et al., 2022). These tools help operationalise participatory principles into clear, measurable actions. Both tools should be used to engage in reflective conversations with autistic community members and researchers throughout the research process to guide good practice, rather than as a tick box exercise at the end.

Next steps

This article describes initial steps to validation rather than full validation. The tools have not yet undergone wider testing beyond the research team and immediate collaborators. Future validation will require broader engagement with autistic communities, including nonspeaking individuals and those with higher support needs, as well as application across varied research context.

More examples of high quality participatory research are needed to guide researchers new to this field (Pickard et al., 2022). Accompanying guidance, which will include good practice examples to assist researchers in using the tools, is currently under development, in collaboration with members of the validation group and will be available on a website which is currently under development.

It is envisaged that both of these tools and accompanying guidance will be regularly updated to reflect feedback and the changing needs of the autism and research community. It would additionally be valuable to validate this tool for broader applications with a wider neurodivergent population and to develop additional tools to evaluate PAR group members' experiences of participation.

Some of the authors are involved in a project to look at how researchers can improve the selection of participatory group members from underrepresented autistic groups (e.g., low Socio-Economic Status (SES), ethnic minorities, those needing high support, LGBTQIA+, and autistic individuals with a learning disability). This will involve collaborative working with Voluntary, Community, Social Enterprise and Faith Organisations (VCSEF) to recruit both people with lived experience and Trusted Advocates (TA) and we will co-create guidance on how to promote inclusivity within Participatory approaches in autism research.

Limitations

As previously reported by Pickard et al. (2022) many of the barriers to effective participatory research are systemic in nature i.e. time, costs, senior staff attitudes or inherent in the research culture (Fletcher-Watson et al., 2019). It is identified that institutional change is needed to fully address some of the structural barriers to participatory research. These tools can highlight these issues and the need to address them at a wider level. They could be utilised by funders and research institutions to embed into evaluation frameworks to promote equitable research practices. In addition to this, there is a need for attitudinal and cultural shifts to effectively address these barriers. Redman et al. (2021) discuss the need for researchers to be trained in participatory approaches as well as ensuring that universities incentivise and value community involvement.

Projects may differ to the extent that power can be shared, depending on context (Pickard et al., 2022; Redman et al., 2021). Nicolaidis et al. (2019) discuss the deep commitment needed to undertake a CBPR approach, which may not be achievable for all projects. As Bellingham et al. (2023) highlight, projects who do not engage in participation across all stages of the research process or who do not score highly in the PAR group checklist, still have value and this can provide an initial starting point for deeper involvement and reflection for the future. We should however, be mindful of their limitations and be transparent in the extent to which autistic people have participated (Bellingham et al., 2023) and this evaluation framework enables this transparency.

The researchers who were involved in validating these tools were from Psychology and Education backgrounds so may not reflect requirements of researchers in other disciplines. The community researchers co-creating this project were recruited from a wider PAR group which was involved in co-creating a project to examine the mental health experiences of autistic university students and therefore were current or recent graduates. The tool was co-developed with autistic individuals with advanced academic backgrounds and the validation group was not representative in terms of gender, people from certain ethnic groups such as African-Caribbean communities nor individuals with learning disabilities including those who are nonspeaking. Further validation across diverse autistic communities (including non-speaking individuals and those with learning disabilities) is needed to ensure these tools capture the full spectrum of autistic experiences.

Conclusion

The present study aimed to address the gaps in skills, support, and resources identified in participatory autism research (Pickard et al., 2022; Fletcher-Watson et al., 2019; Jivraj et al., 2014) by developing and carrying out initial steps to validating a structured evaluation framework to support researchers in fostering the meaningful participation of autistic individuals throughout the research process.

The ELPART and PAR Group Checklist were designed to promote best practices in participatory research, helping to combat stigma (Kaplan-Kahn & Caplan, 2023) and redress power imbalances that have historically marginalised autistic voices in autism research (Den Houting et al., 2021; Nicolaidis et al., 2019; Rose, 2018). Initial steps to validate these tools through collaboration with autistic individuals, community stakeholders, and experienced autism researchers, ensuring they reflect a diverse range of research experiences, participatory methods, and autism knowledge.

By embedding structured reflection and accountability into the research process, we hope these tools serve as a valuable resource for researchers at all career stages, ensuring that autistic voices are not only included but centered in shaping the future of autism research.

Authorship Confirmation/Contribution Statement

Ellie Horton: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualisation, Writing – Original draft preparation, Writing – Review and editing. Laura A Brownhill: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project Administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – Review and editing. Daniel Tones: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project Administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – Review and editing. Anita Z Goldschmied: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – Review and editing. Max J J Knops: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – Review and editing. Emine Gurbuz - Validation, Writing - Review and editing . Eleanor J. Dommett: Validation, Writing - Review and editing. Lauren Elizabeth Wilkinson: Validation, Writing - Review and editing. Jackie Taylor: Validation. Carla T Toro: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – Review and editing. Jagjeet Jutley-Neilson: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualisation, Writing – Review and editing.

Funding Statement

Part of this work was supported by University of Warwick through an internal research grant (Spotlight fund).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the additional members of the participatory group who took part in discussions leading up to this research.

Conflict of Interest Statement

None declared.

References

- Bellingham, B., Elder, E., Foxlewin, B., Gale, N., Rose, G., Sam, K., Thorburn, K., River, & J. (2023). ‘Co-design kickstarter’, community mental health drug and alcohol research network. Available at: https://cmhdaresearchnetwork.com.au/resource/ co-design-kickstarter/.

- Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R., & Young, S. L. (2018). Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: a primer.Frontiers in public health,6, 149.

- Bottema-Beutel, K., Kapp, S. K., Sasson, N., Gernsbacher, M. A., Natri, H., & Botha, M. (2023). Anti-ableism and scientific accuracy in autism research: a false dichotomy. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1244451. [CrossRef]

- Botha, M. (2021). Academic, activist, or advocate? Angry, entangled, and emerging: A critical reflection on autism knowledge production. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 727542. [CrossRef]

- Botha, M., & Frost, D. M. (2020).Extending the minority stress model to understand mental health problems experienced by the autistic population. Society and Mental Health, 10(1), 20–34. [CrossRef]

- Cooperative Research Centre for Living with Autism (2016). Inclusive Research Practice Guides and Checklists for Autism Research: version 2. Brisbane, Queens land. Autism CRC Ltd.

- Cornwall, A. (2008). "Unpacking ‘Participation’: Models, meanings, and practices." Community Development Journal, 43(3), 269-283.

- Crane, L., Adams, F., Harper, G., Welch, J., & Pellicano, E. (2019). ‘Something needs to change’: Mental health experiences of young autistic adults in England. Autism, 23(2), 477-493.

- Dark, J. (2024). Eight principles of neuro-inclusion; an autistic perspective on innovating inclusive research methods. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, pp1326536.

- DeVon, H. A., et al. (2007). Psychometric toolbox for testing validity and reliability. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 39(2), 155-164.

- Den Houting, J., Higgins, J., Isaacs, K., Mahony, J., & Pellicano,E. (2021). I’m not just a Guinea pig’: Academic and community perceptions of participatory autism research. Autism, 25(1), 148–163. [CrossRef]

- Den Houting, J., & Pellicano, E. (2019). A portfolio analysis of autism research funding in Australia, 2008–2017. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49, 4400-4408.

- Doyle, M., & Timonen, V. (2010). Lessons from a community-based participatory research project: Older people’s and researchers’ reflections. Research on Aging, 32(2), 244–263. [CrossRef]

- Ewert, B., & Evers, A. (2014). An ambiguous concept: On the meanings of co-production for health care users and user organizations? VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 25, 425–442. [CrossRef]

- Fletcher-Watson, S., Bölte, S., Crompton, C. J., Jones, D., Lai, M. C., Mandy, W., ... & Mandell, D. (2021). Publishing standards for promoting excellence in autism research.Autism,25(6), 1501-1504.

- Fletcher-Watson, S., Adams, J., Brook, K., Charman, T., Crane, L., Cusack, J., Leekam, S., Milton, D., Parr, J. R., & Pellicano,E. (2019). Making the future together: Shaping autism research through meaningful participation. Autism, 23(4), 943–953. [CrossRef]

- Foster-Fishman, P., Nowell, B., Deacon, Z., Nievar, M. A., & McCann, P. (2005). Using methods that matter: The impact of reflection, dialogue, and voice. American Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 275–291A., & McCann, P. (2005). Using methods that matter: The impact of reflection, dialogue, and voice. [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. (1970), Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Continuum Publishing, New York, NY.

- Garfield, T., & Yudell, M. (2019). Commentary 2: Participatory justice and ethics in autism research. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 14(5), 455–45. [CrossRef]

- Gowen, E., Taylor, R., Bleazard, T., Greenstein, A., Baimbridge, P. and Poole, D. (2019) Guidelines for Conducting research with the autism community. Autism Policy and Practice. 2(1) 29–45.

- Grant, A., & Kara, H. (2021). Considering the Autistic advantage in qualitative research: the strengths of Autistic researchers. Contemporary Social Science, 16(5), 589-603.

- Haynes, S. N., Richard, D., & Kubany, E. S. (1995). Content validity in psychological assessment: A functional approach to concepts and methods.Psychological assessment,7(3), 238.

- Hinkin, T. R. (1995). A review of scale development practices in the study of organizations. Journal of management, 21(5), 967-988.

- Hollin G., Pearce W. (2019). Autism scientists’ reflections on the opportunities and challenges of public engagement: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(3), 809–818. [CrossRef]

- Horton,E., Goldschmied, A. Z., Knops, M. J. J., Brownhill, L. A., Bycroft, A., Lloyd, A., Tones, D., Wiltshire, B., Toro, C. T., & Jutley-Neilson, J. (2024).Empowering voices: fostering reflective dialogue and redefining research dynamics in participatory approaches with the autistic community. Journal of Participatory Research Methods, 5. [CrossRef]

- James Lind Alliance. (2023). About the JLA. National Institute for Health and Care Research. https://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk.

- Jivraj, J., Sacrey, L. A., Newton, A., Nicholas, D., & Zwaigenbaum, L. (2014). Assessing the influence of researcher–partner involvement on the process and outcomes of participatory research in autism spectrum disorder and neurodevelopmental disorders: A scoping review. Autism, 18(7), 782-793.

- Kaplan-Kahn, E. A., & Caplan, R. (2023). Combating stigma in autism research through centering autistic voices: a co-interview guide for qualitative research. Frontiers in psychiatry, 14, 1248247. [CrossRef]

- Kenny, L., Hattersley, C., Molins, B., Buckley, C., Povey, C., & Pellicano, E. (2016). Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community. Autism, 20(4), 442-462.

- Lam, G. Y. H., Holden, E., Fitzpatrick, M., Raffaele Mendez, L., & Berkman, K. (2020). “Different but connected”: Participatory action research using Photovoice to explore well-being in autistic young adults. Autism, 24(5), 1246-1259.

- Lasker, R. D., & Weiss, E. S. (2003). Broadening participation in community problem solving: a multidisciplinary model to support collaborative practice and research.Journal of Urban Health,80, 14-47.

- Le Cunff, A.-L., Ellis Logan, P., Martic, B. L., Mousset, I., Sekibo, J., Dommett. E. & Giampietro, V. (2023). Co-Design for ParticipatoryNeurodiversity Research: Collaborating with a Community Advisory Board to Design a Research Study. Journal of Participatory Research Methods, 4(1).

- Mabetha, D., Ojewola, T., Van Der Merwe, M., Mabika, R., Goosen, G., Sigudla, J., ... & On behalf in collab the Verbal Autopsy with Participatory Action Research (VAPAR)/Wits/Mpumalanga Department of Health Learning Platform. (2023). Realising radical potential: building community power in primary health care through Participatory Action Research. International Journal for Equity in Health, 22(1), 94.

- May, E. (2024). Critical pedagogy and disability in participatory research: a review. Information and Learning Sciences, 125(7–8), 437–455. [CrossRef]

- Maye, M., Boyd, B. A., Martínez-Pedraza, F., Halladay, A., Thurm, A., & Mandell, D. S. (2022). Biases, Barriers, and Possible Solutions: Steps Towards Addressing Autism Researchers Under-Engagement with Racially, Ethnically, and Socioeconomically Diverse Communities. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 52(9), 4206–4211. [CrossRef]

- McNally, D., Sharples, S., Craig, G., & Goraya, F. R. C. G. P. (2015). Patient leadership: Taking patient experience to the next level?. Patient Experience Journal, 2(2), 7-15.

- Milton, D. E. M., Ridout, S., Kourti, M., Loomes, G., & Martin, N. (2019). A critical reflection on the development of the Participatory Autism Research Collective (PARC). Tizard Learning Disability Review, 24(2), 82-89.

- Milton D. E. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: The ‘double empathy problem’. Disability & Society, 27(6), 883–887. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad., M., Wallerstein., N., Sussman., A. l., Avila., M., Belone., L., Duran., B. (2015) Reflections on researcher identity and power: The impact of positionality on Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) processes and outcomes. Critical Sociology, 41(7-8), 1045-1063. [CrossRef]

- Nicolaidis, C., Raymaker, D., McDonald, K., Kapp, S., Weiner, M., Ashkenazy, E., Gerrity, M., Kripke, C., Platt, L., & Baggs, A. (2016). The Development and Evaluation of an Online Healthcare Toolkit for Autistic Adults and their Primary Care Providers. Journal of general internal medicine, 31(10), 1180–1189. [CrossRef]

- Nicolaidis, C., Raymaker, D., Kapp, S. K., Baggs, A., Ashkenazy, E., McDonald, K., Weiner, M., Maslak, J., Hunter, M. & Joyce, A. (2019). The AASPIRE practice-based guidelines for the inclusion of autistic adults in research as co-researchers and study participants. Autism, 23(8): 2007–2019. [CrossRef]

- Norman, G. (2010). Likert scales, levels of measurement, and the “laws” of statistics. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 15(5), 625-632.

- Patton, M. Q. (2008). Utilization-focused evaluation. SAGE Publications.

- Pavlopoulou, G. (2021). A good night’s sleep: learning about sleep from autistic adolescents’ personal accounts. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 583868.

- Pellicano, E., Dinsmore, A., & Charman, T. (2014a). Views on researcher-community engagement in autism research in the United Kingdom: A mixed-methods study. PLoS One, 9(10), e109946.

- Pellicano, L. (2014b). A future made together: new directions in the ethics of autism research. Journal of research in special educational needs, 14(3), 200-204.

- Pellicano E., Crane L., Gaudion K. & the Shaping Autism Research Team. (2017).Participatory autism research: A starter pack. UCL Institute of Education.

- Pickard, H., Pellicano, E., Den Houting, J., & Crane, L. (2022). Participatory autism research: Early career and established researchers’ views and experiences.Autism,26(1), 75-87.

- Rappaport, J. (1990). Research methods and the empowerment social agenda. In P. Tolan, C. Keys, F. Chertok, & L. A. Jason (Eds.), Researching community psychology: Issues of theory and methods (pp. 51–63). American Psychological Association. [CrossRef]

- Rauchberg, J. S. (2022). Imagining a neuroqueer technoscience.Studies in Social Justice, 16(2), 370–388. [CrossRef]

- Redman, S., Greenhalgh, T., Adedokun, L., Staniszewska, S., Denegri, S., & Co-production of Knowledge Collection Steering Committee. (2021). Co-production of knowledge: the future. bmj, 372(434). [CrossRef]

- Robson, C. (2024).Real world research. John Wiley & Sons.

- Roche L., Adams D., Clark M. (2021). Research priorities of the autism community: A systematic review of key stakeholder perspectives. Autism, 25(2), 336–348. [CrossRef]

- Rose, D. (2018). Participatory research: real or imagined. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(8), 765–771. [CrossRef]

- Rudd, D., & Hwang, S. K. (2021). Participatory research in a pandemic: The impact of COVID-19 on co-designing research with autistic people. Qualitative Social Work.

- Schwartz, A. E., Kramer, J. M., Cohn, E. S., & McDonald, K. E. (2020). “That felt like real engagement”: Fostering and maintaining inclusive research collaborations with individuals with intellectual disability. Qualitative Health Research, 30(2), 236–249. [CrossRef]

- Singer, J. (2016). Neurodiversity: The birth of an idea. Springer.

- Spencer, L., Leonard, N., Jessiman, P., Kaluževičiūtė-Moreton, G., Limmer, M., & Kidger, J. (2024). Exploring the feasibility of using Participatory Action Research (PAR) as a mechanism for school culture change to improve mental health. Pastoral Care in Education, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Stark, E., Ali, D., Ayre, A., Schneider, N., Parveen, S., Marais, K., ... & Pender, R. (2021). Coproduction with autistic adults: Reflections from the authentistic research collective. Autism in Adulthood, 3(2), 195-203.

- Tan, D. W., Crane, L., Haar, T., Heyworth, M., Poulsen, R., & Pellicano, E. (2024). Reporting community involvement in autism research: Findings from the journal Autism. Autism, 29(2).

- Tourangeau, R., et al. (2000). The psychology of survey response. Cambridge University Press.

- Vaughn, L. M., & Jacquez, F. (2020). Participatory research methods–choice points in the research process. Journal of Participatory Research Methods, 1(1).

- Williams R. M., Gilbert J. E. (2020). Perseverations of the academy: A survey of wearable technologies applied to autism intervention. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 143, 102485. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Validation activity – ELPART.

Table 1.

Validation activity – ELPART.

| Construct validity |

Actions |

Stage 1 (Deciding the Research Topic)

Separate items ‘Proposing initial research idea’ and‘focused on the priorities of the autistic community’ when they could be combined. |

Items amalgamated into ‘Initial research idea is focused on the priorities of the autistic community’

|

| Face validity |

Actions |

Scoring key

Need for clarity around what is meant by ‘led by’ or ‘involvement’. |

Footnote with explanation was added. |

Scoring key

Terminology used in scoring key described autistic community members as ‘researchers’. PAR group members should be considered researchers but researchers may also be neurodivergent, where do they fit in? Also, tool may be used within non academic settings such as in the voluntary sector, where they may not view themselves as traditional researchers so some flexibility is needed.

|

Amended wording from ‘researcher’ to ‘people’. |

Stage 1 (Deciding the Research Topic) and 2 (Selecting Research Methods and Tools)

Item ‘Developing initial research idea’ was duplicated across stage 1 and 2. |

Amended wording in stage 1 to ‘Initial research idea is focused on the priorities of the autistic community’ and amended wording in stage 2 to ‘Deciding on research questions and aims’. |

| Content validity |

Actions |

Stage 4 (Analysing Research)

Autistic people should be involved in interpreting results and deciding how they are presented.

|

Added items ‘Implications/interpretations of results’ and ‘Deciding how results are presented’. |

Table 2.

Validation activity – PAR Group Checklist.

Table 2.

Validation activity – PAR Group Checklist.

| Face validity |

Actions |

| Important for tool to be applicable and relevant in a wide range of interactions rather than being restricted to meetings to promote inclusivity and ensure that members could participate according to their preferences. |

Amended wording throughout from ‘meetings’ to ‘mode of interactions’.

|

Establishing the PAR group

Item ‘Participatory group was established early in the research process’ could create confusion around what ‘early in the process’ means and to promote good practice in establishing the PAR group in the planning stages.

|

Amended wording to 'Participatory group was established in the planning stages of the research process’. |

Creating accessible interactions

Item ‘Flexibility around how members contributed i.e. attending meetings or typing into chat, cameras on or off, email contribution after meeting etc.’ needs clarification and assumes meetings as the main format. |

Amended wording to; ‘Opportunities for involvement were not limited to meetings and utilised creative approaches (several formats could be offered i.e. email, contribution via chat, teams etc)’. Item also moved from the ‘Redressing power dynamics’ to ‘Creating accessible interactions’ section.

|

Redressing power dynamics

Item ‘Group members had every opportunity to lead meetings’. The group felt that some members may not want to lead meetings, and having support is important. |

Amended wording to ‘group members had opportunity and support to lead meetings’.

|

Redressing power dynamics

Item ‘Group members were paid for their time’. This is an important issue to redress power dynamics. Community members considered how they were paid to be an individual choice and outlined the need for flexibility.Ideally we need to pay people and ensure fair remuneration but also offer a range of options. The researchers discussed how this is often difficult due to bureaucracy in university and wider settings. We agreed that we should be explicit about how group members are remunerated from the start and where possible, ask for their preferences. |

Amended wording to ‘Group members were remunerated fairly and equitably for their time’ with further guidance in accompanying materials.

|

Redressing power dynamics

Need to add examples for item ‘Group members had the appropriate information to make a valid contribution to shaping the research’. |

Added example ‘i.e. received training/relevant information’. |

Redressing power dynamics

Need to add an example for the item ‘Group members benefited from taking part’. Additionally, some members may not want to be named in publications. |

Amended wording and added example to ‘Group members benefited from taking part i.e. have increased career prospects, opportunity to be named in publications’. |

| Content validity |

Actions |

Establishing the PAR group

Importance of transparency and clarity around members' responsibilities and expectations. |

Added item ‘Autistic people were asked about their preferred level of involvement and clear about expectations’. |

Establishing the PAR group

Importance of agreeing on language used to describe autism. |

Added item ‘Group members agreed on language used’.

|

Establishing the PAR group

Importance of transparency around the decision making process and accountability when establishing the group. |

Added item ‘Accountability and decision making process is clear’.

|

Creating accessible interactions

Important to reflect on inclusion throughout the research process in order to meet any changing needs. |

Added item ‘Modes of interaction and engagement were reflected throughout the process and adjustments were made accordingly’. |

Redressing power dynamics

Important to reflect on decision making. |

Added item ‘Everyone was equally involved in decision making’. We discussed adding good practice examples to the accompanying guidance.

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).