Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

16 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

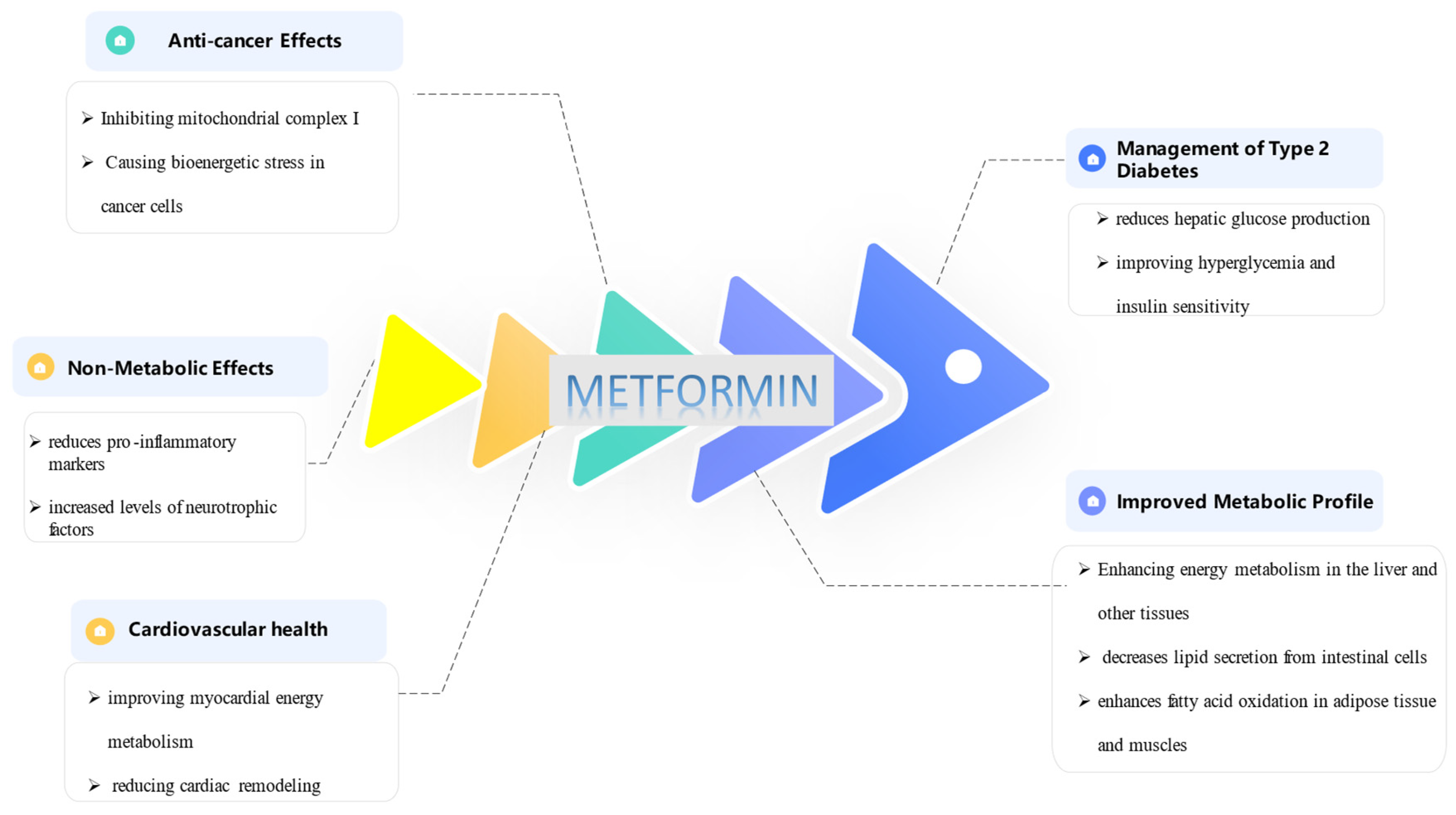

2. Metformin: Its Properties and Applications

3. Three-Dimensional(3D) Cell Culture Models of Disease

4. Extracellular Matrix (ECM)

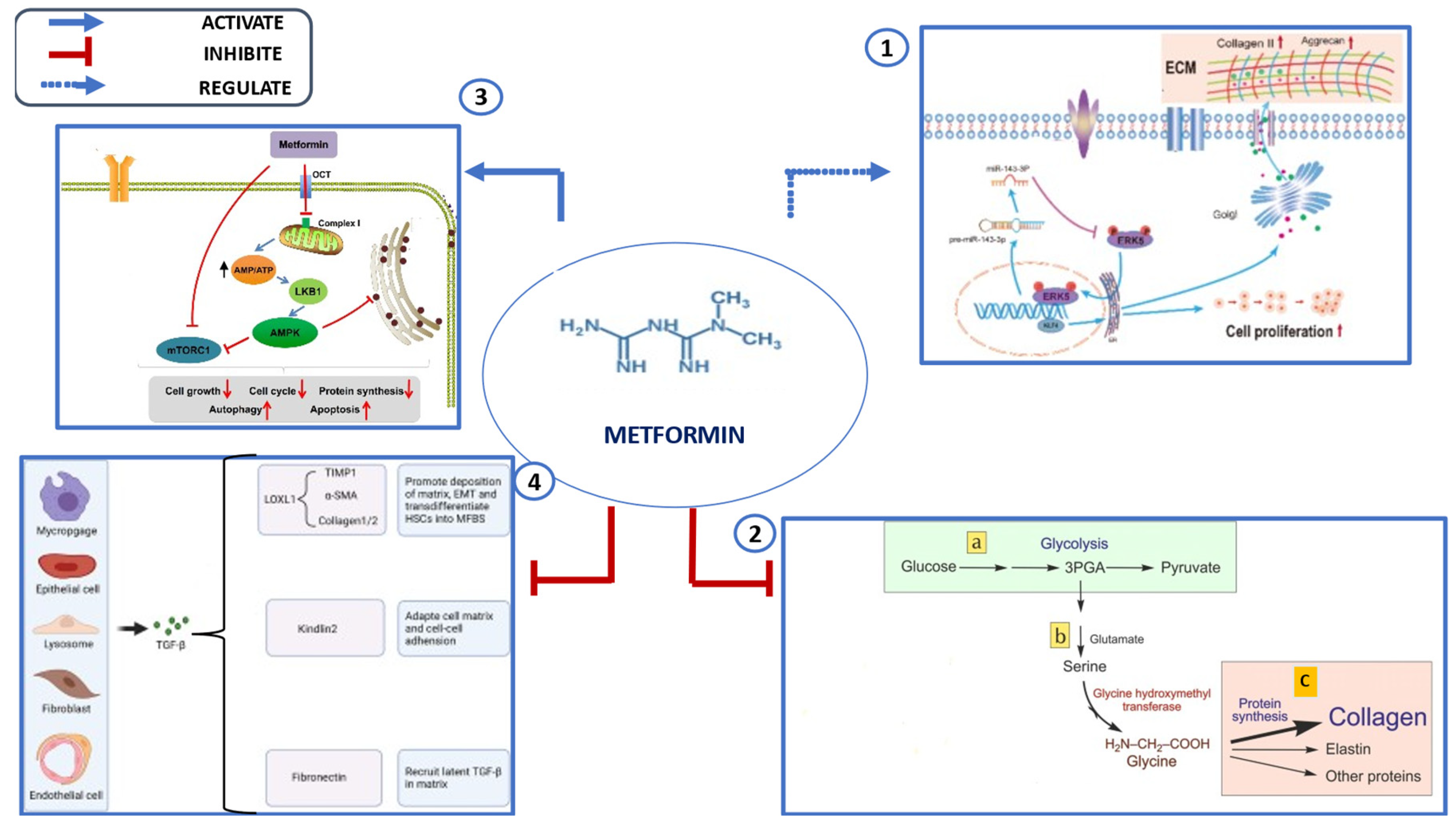

5. Effects of Metformin on ECM

6. Key Mechanisms Underlying Metformin’s Effects on the ECM

7. Application of Metformin in 3D Disease Models

7.1. Cancer

7.2. Fibrose

7.3. Diabetes and Metabolic Diseases

8. Other Application of Metformin with ECM

9. Challenges and Limitations

10. Future Directions

11. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of interest

References

- Dutta, S.; Shah, R.B.; Singhal, S.; Dutta, S.B.; Bansal, S.; Sinha, S.; Haque, M. Metformin: A Review of Potential Mechanism and Therapeutic Utility Beyond Diabetes. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2023, 17, 1907–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, A.; Sanaie, S.; Hamzehzadeh, S.; Seyedi-Sahebari, S.; Hosseini, M.-S.; Gholipour-Khalili, E.; Majidazar, R.; Seraji, P.; Daneshvar, S.; Rezazadeh-Gavgani, E. Metformin: new applications for an old drug. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2022, 34, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Incio, J.; Suboj, P.; Chin, S.M.; Vardam-Kaur, T.; Liu, H.; Hato, T.; Babykutty, S.; Chen, I.; Deshpande, V.; Jain, R.K.; et al. Metformin Reduces Desmoplasia in Pancreatic Cancer by Reprogramming Stellate Cells and Tumor-Associated Macrophages. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0141392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamanos, N.K.; Theocharis, A.D.; Piperigkou, Z.; Manou, D.; Passi, A.; Skandalis, S.S.; Vynios, D.H.; Orian-Rousseau, V.; Ricard-Blum, S.; Schmelzer, C.E.; et al. A guide to the composition and functions of the extracellular matrix. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 6850–6912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharis, A.D.; Skandalis, S.S.; Gialeli, C.; Karamanos, N.K. Extracellular matrix structure. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2016, 97, 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, T.R.; Erler, J.T. Remodeling and homeostasis of the extracellular matrix: implications for fibrotic diseases and cancer. Dis. Model. Mech. 2011, 4, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaicik, M.K.; Kortesmaa, J.T.; Movérare-Skrtic, S.; Kortesmaa, J.; Soininen, R.; Bergström, G.; Ohlsson, C.; Chong, L.Y.; Rozell, B.; Emont, M.; et al. Laminin α4 Deficient Mice Exhibit Decreased Capacity for Adipose Tissue Expansion and Weight Gain. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e109854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang-Jensen, K.C.; Jørgensen, S.M.; Chuang, C.Y.; Davies, M.J. Modification of extracellular matrix proteins by oxidants and electrophiles. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2024, 52, 1199–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, Y.; Long, H.; Liang, Z.; He, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, S.; Bao, J. Tissue-specific micropattern array chips fabricated via decellularized ECM for 3D cell culture. MethodsX 2023, 11, 102463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urciuolo, F.; Imparato, G.; Netti, P.A. In vitro strategies for mimicking dynamic cell–ECM reciprocity in 3D culture models. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1197075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainio, A.; Järveläinen, H. Extracellular matrix-cell interactions: Focus on therapeutic applications. Cell. Signal. 2020, 66, 109487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L. Metformin and Systemic Metabolism. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2020, 41, 868–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rena, G.; Hardie, D.G.; Pearson, E.R. The mechanisms of action of metformin. Diabetologia. 2017, 60, 1577–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; An, H.; Liu, T.; Qin, C.; Sesaki, H.; Guo, S.; Radovick, S.; Hussain, M.; Maheshwari, A.; Wondisford, F.E.; et al. Metformin Improves Mitochondrial Respiratory Activity through Activation of AMPK. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 1511–1523.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeedi, R.; Parsons, H.L.; Wambolt, R.B.; Paulson, K.; Sharma, V.; Dyck, J.R.B.; Brownsey, R.W.; Allard, M.F. Metabolic actions of metformin in the heart can occur by AMPK-independent mechanisms. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2008, 294, H2497–H2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziubak, A.; Wójcicka, G.; Wojtak, A.; Bełtowski, J. Metabolic Effects of Metformin in the Failing Heart. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.-K.; Cheng, K.-C.; Mgbeahuruike, M.O.; Lin, Y.-H.; Wu, C.-Y.; Wang, H.-M.D.; Yen, C.-H.; Chiu, C.-C.; Sheu, S.-J. New Insight into the Effects of Metformin on Diabetic Retinopathy, Aging and Cancer: Nonapoptotic Cell Death, Immunosuppression, and Effects beyond the AMPK Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrzejewski, S.; Siegel, P.M.; St-Pierre, J. Metabolic Profiles Associated With Metformin Efficacy in Cancer. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghshenas, M.; Firouzabadi, N.; Akbarizadeh, A.R.; Rashedinia, M. Combination of metformin and gallic acid induces autophagy and apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 18, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dludla, P.V.; Nkambule, B.B.; Mazibuko-Mbeje, S.E.; Nyambuya, T.M.; Mxinwa, V.; Mokgalaboni, K.; Ziqubu, K.; Cirilli, I.; Marcheggiani, F.; Louw, J.; et al. Adipokines as a therapeutic target by metformin to improve metabolic function: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 163, 105219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristova, M.G. Metabolic Syndrome and Neurotrophins: Effects of Metformin and Non-Steroidal Antiinflammatory Drug Treatment. Eurasian J. Med. 2011, 42, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, C.; Teng, Y. Is It Time to Start Transitioning From 2D to 3D Cell Culture? Front Mol Biosci. 2020, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, K.; Chen, X.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, H.; Li, P.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Li, T.; Qin, X.; et al. Simultaneous 2D and 3D cell culture array for multicellular geometry, drug discovery and tumor microenvironment reconstruction. Biofabrication 2021, 13, 045013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salinas-Vera, Y.M.; Valdés, J.; Pérez-Navarro, Y.; Mandujano-Lazaro, G.; Marchat, L.A.; Ramos-Payán, R.; Nuñez-Olvera, S.I.; Pérez-Plascencia, C.; López-Camarillo, C. Three-Dimensional 3D Culture Models in Gynecological and Breast Cancer Research. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 826113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, N.; Fenech, A.G.; Magri, V.P. 3D cell culture models in research: applications to lung cancer pharmacology. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1438067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.H.; Choi, S.H.; D'Avanzo, C.; Hebisch, M.; Sliwinski, C.; Bylykbashi, E.; Washicosky, K.J.; Klee, J.B.; Brüstle, O.; ETanzi, R.; et al. A 3D human neural cell culture system for modeling Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Protoc. 2015, 10, 985–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, A.; Koch, H.; van Loo, K.M.; Schmied, K.; Gittel, B.; Weber, Y.; Ort, J.; Schwarz, N.; Tauber, S.C.; Wuttke, T.V.; et al. Human organotypic brain slice cultures: a detailed and improved protocol for preparation and long-term maintenance. J. Neurosci. Methods 2024, 404, 110055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloise, N.; Giannaccari, M.; Guagliano, G.; Peluso, E.; Restivo, E.; Strada, S.; Volpini, C.; Petrini, P.; Visai, L. Growing Role of 3D In Vitro Cell Cultures in the Study of Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms: Short Focus on Breast Cancer, Endometriosis, Liver and Infectious Diseases. Cells 2024, 13, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryoo, H.; Giovanni, R.; Kimmel, H.; Jain, I.; Underhill, G.H. Combinatorial Microgels for 3D ECM Screening and Heterogeneous Microenvironmental Culture of Primary Human Hepatic Stellate Cells. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2303128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, J.F.; Skhinas, J.N.; Fey, D.; Croucher, D.R.; Cox, T.R. The extracellular matrix as a key regulator of intracellular signalling networks. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 176, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Takai, K.; Weaver, V.M.; Werb, Z. Extracellular Matrix Degradation and Remodeling in Development and Disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a005058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H. Extracellular matrix: an important regulator of cell functions and skeletal muscle development. Cell Biosci. 2021, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theocharis, A.D.; Manou, D.; Karamanos, N.K. The extracellular matrix as a multitasking player in disease. FEBS J. 2019, 286, 2830–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eble, J.A.; Niland, S. The extracellular matrix in tumor progression and metastasis. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2019, 36, 171–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ojeda, F.J.; Méndez-Gutiérrez, A.; Aguilera, C.M.; Plaza-Díaz, J. Extracellular Matrix Remodeling of Adipose Tissue in Obesity and Metabolic Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, S.; Ding, F.; Gong, L.; Gu, X. Extracellular Matrix Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 12, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browe, D.C.; Díaz-Payno, P.J.; Freeman, F.E.; Schipani, R.; Burdis, R.; Ahern, D.P.; Nulty, J.M.; Guler, S.; Randall, L.D.; Buckley, C.T.; et al. Bilayered extracellular matrix derived scaffolds with anisotropic pore architecture guide tissue organization during osteochondral defect repair. Acta Biomater. 2022, 143, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habanjar, O.; Diab-Assaf, M.; Caldefie-Chezet, F.; Delort, L. 3D Cell Culture Systems: Tumor Application, Advantages, and Disadvantages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akther, F.; Little, P.; Li, Z.; Nguyen, N.-T.; Ta, H.T. Hydrogels as artificial matrices for cell seeding in microfluidic devices. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 43682–43703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, J.; Magli, S.; Rabbachin, L.; Sampaolesi, S.; Nicotra, F.; Russo, L. 3D Extracellular Matrix Mimics: Fundamental Concepts and Role of Materials Chemistry to Influence Stem Cell Fate. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 1968–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.P.; Gaspar, V.M.; Mano, J.F. Decellularized Extracellular Matrix for Bioengineering Physiomimetic 3D in Vitro Tumor Models. Trends Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 1397–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdoz, J.C.; Johnson, B.C.; Jacobs, D.J.; Franks, N.A.; Dodson, E.L.; Sanders, C.; et al. The ECM: To Scaffold, or Not to Scaffold, That Is the Question. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paradiso, F.; Serpelloni, S.; Francis, L.W.; Taraballi, F. Mechanical Studies of the Third Dimension in Cancer: From 2D to 3D Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Nocon, A.; Fry, J.; Sherban, A.; Rui, X.; Jiang, B.; Xu, X.J.; Han, J.; Yan, Y.; Yang, Q.; et al. AMPK Activation by Metformin Suppresses Abnormal Extracellular Matrix Remodeling in Adipose Tissue and Ameliorates Insulin Resistance in Obesity. Diabetes 2016, 65, 2295–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ding, Q.; Ling, L.P.; Wu, Y.; Meng, D.X.; Li, X.; et al. Metformin attenuates motility, contraction, and fibrogenic response of hepatic stellate cells in vivo and in vitro by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. World J Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 819–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Qiao, X.; Xing, X.; Huang, J.; Qian, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Cui, J.; et al. Matrix Stiffness-Upregulated MicroRNA-17-5p Attenuates the Intervention Effects of Metformin on HCC Invasion and Metastasis by Targeting the PTEN/PI3K/Akt Pathway. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Shen, W.; Liu, Z.; Sheng, S.; Xiong, W.; He, R.; Zhang, X.; Ma, L.; Ju, Z. Effect of Metformin on Cardiac Metabolism and Longevity in Aged Female Mice. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya, Y.E.; Karaarslan, N.; Yilmaz, I.; Yasar, D.S.; Akalan, H.; Ozbek, H. A study of the effects of metformin, a biguanide derivative, on annulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus cells. Turk. Neurosurg. 2019, 30, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Li, S.; Lu, S.; Liu, H.; Li, G.; Ma, L.; Luo, R.; Ke, W.; Wang, B.; Xiang, Q.; et al. Metformin facilitates mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular nanovesicles release and optimizes therapeutic efficacy in intervertebral disc degeneration. Biomaterials 2021, 274, 120850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.-Q.; Sun, X.-J.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, N.-F. Metformin attenuates hyperlipidaemia-associated vascular calcification through anti-ferroptotic effects. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 165, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.P.; Jeong, H.G. Metformin blocks migration and invasion of tumour cells by inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase-9 activation through a calcium and protein kinase Calpha-dependent pathway: phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate-induced/extracellular signal-regulated kinase/activator protein-1. Br J Pharmacol. 2010, 160, 1195–211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blandino, G.; Valerio, M.; Cioce, M.; Mori, F.; Casadei, L.; Pulito, C.; Sacconi, A.; Biagioni, F.; Cortese, G.; Galanti, S.; et al. Metformin elicits anticancer effects through the sequential modulation of DICER and c-MYC. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.-J.; Xu, J.; Ye, H.-Y.; Wang, X.-B. Metformin prevents PFKFB3-related aerobic glycolysis from enhancing collagen synthesis in lung fibroblasts by regulating AMPK/mTOR pathway. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xiang, P.; Liu, L.; Sun, J.; Ye, S. Metformin inhibits extracellular matrix accumulation, inflammation and proliferation of mesangial cells in diabetic nephropathy by regulating H19/miR-143-3p/TGF-β1 axis. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2020, 72, 1101–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Tian, X.; Zhang, B.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Yang, C.; Wu, J.; Wei, X.; Qu, Q.; Yu, Y.; et al. Low-dose metformin targets the lysosomal AMPK pathway through PEN2. Nature 2022, 603, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.H.; Um, J.Y.; Hong, S.M.; Cho, J.S.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, S.H.; et al. Metformin reduces TGF-β1-induced extracellular matrix production in nasal polyp-derived fibroblasts. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014, 150, 148–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, M.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Deng, Y.; Yang, S.; Pan, W.; Zhang, X.; Xu, G.M.; Xiao, S.M.; Deng, C.M. Metformin Eliminates Lymphedema in Mice by Alleviating Inflammation and Fibrosis: Implications for Human Therapy. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2024, 154, 1128e–1137e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, C.; Han, R.; Lu, C.; Li, L.; Hu, C.; Feng, M.; Chen, H.; He, Y. Metformin attenuates TGF-β1-induced pulmonary fibrosis through inhibition of transglutaminase 2 and subsequent TGF-β pathways. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, S.; Conaldi, P.G.; Florio, T.; Pagano, A. PPAR Gamma in Neuroblastoma: The Translational Perspectives of Hypoglycemic Drugs. PPAR Res. 2016, 2016, 3038164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutaud, M.; Auger, C.; Verdier, M.; Christou, N. Metformin Treatment Reduces CRC Aggressiveness in a Glucose-Independent Manner: An In Vitro and Ex Vivo Study. Cancers 2023, 15, 3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hassan, M.; Fakhoury, I.; El Masri, Z.; Ghazale, N.; Dennaoui, R.; El Atat, O.; Kanaan, A.; El-Sibai, M. Metformin Treatment Inhibits Motility and Invasion of Glioblastoma Cancer Cells. Anal. Cell. Pathol. 2018, 2018, 5917470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, T.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Yi, J.; Zhang, W.; Chen, D.; Ao, J.; Xiao, Z.-X.; Yi, Y. Integrin β1-Mediated Cell–Cell Adhesion Augments Metformin-Induced Anoikis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schexnayder, C.; Broussard, K.; Onuaguluchi, D.; Poché, A.; Ismail, M.; McAtee, L.; Llopis, S.; Keizerweerd, A.; McFerrin, H.; Williams, C. Metformin Inhibits Migration and Invasion by Suppressing ROS Production and COX2 Expression in MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Al-Sammarraie, N.; DiPette, D.J.; Singh, U.S. Correction: Metformin impairs Rho GTPase signaling to induce apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells and inhibits growth of tumors in the xenograft mouse model of neuroblastoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 42843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocquet, L.; Juin, P.P.; Souazé, F. Mitochondria at Center of Exchanges between Cancer Cells and Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts during Tumor Progression. Cancers 2020, 12, 3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.M.; Jang, A.-H.; Kim, H.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, Y.W. Metformin Reduces Bleomycin-induced Pulmonary Fibrosis in Mice. J. Korean Med Sci. 2016, 31, 1419–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Jiang, Z.; Li, J.; Lin, H.; Xu, B.; Liao, X.; Fu, Z.; Ao, H.; Guo, G.; Liu, M. Metformin Improves Burn Wound Healing by Modulating Microenvironmental Fibroblasts and Macrophages. Cells 2022, 11, 4094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, H.; Kramar, S.; Laborde, C.; Marsal, D.; Pizzinat, N.; Cussac, D.; Roncalli, J.; Boal, F.; Tronchere, H.; Oleshchuk, O.; et al. Metformin Attenuates Postinfarction Myocardial Fibrosis and Inflammation in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pchejetski, D.; Foussal, C.; Alfarano, C.; Lairez, O.; Calise, D.; Guilbeau-Frugier, C.; Schaak, S.; Seguelas, M.-H.; Wanecq, E.; Valet, P.; et al. Apelin prevents cardiac fibroblast activation and collagen production through inhibition of sphingosine kinase 1. Eur. Hear. J. 2011, 33, 2360–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluivers, K.B.; Lince, S.L.; Ruiz-Zapata, A.M.; Post, W.M.; Cartwright, R.; Kerkhof, M.H.; Widomska, J.; De Witte, W.; Pecanka, J.; Kiemeney, L.A.; et al. Molecular Landscape of Pelvic Organ Prolapse Provides Insights into Disease Etiology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhong, N.-N.; Wang, X.; Peng, B.; Chen, Z.; Wei, L.; Li, B.; Li, Y.; Cheng, Y. Metformin Attenuates TGF-β1-Induced Fibrosis in Salivary Gland: A Preliminary Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W.; Song, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Ruan, H.; Fan, C. Metformin prevents peritendinous fibrosis by inhibiting transforming growth factor-β signaling. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 101784–101794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Ma, X.; Feng, W.; Fu, Y.; Lu, Z.; Xu, M.; Shen, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Metformin attenuates cardiac fibrosis by inhibiting the TGFβ1–Smad3 signalling pathway. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010, 87, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazquez-Armendariz, A.I.; Barroso, M.M.; El Agha, E.; Herold, S. 3D In Vitro Models: Novel Insights into Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Pathophysiology and Drug Screening. Cells 2022, 11, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Septembre-Malaterre, A.; Boina, C.; Douanier, A.; Gasque, P. Deciphering the Antifibrotic Property of Metformin. Cells 2022, 11, 4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Yang L, Zhang Q, Shi X, Hua F, Ma J, et al., editors. Nod-like Receptor Protein 3 (Nlrp3) Inflammasomes Inhibition by Metformin Limits Myocardial Ischemia/reperfusion Injury2020.

- Xu, Z.; Ye, H.; Xiao, W.; Sun, A.; Yang, S.; Zhang, T.; Sha, X.; Yang, H. Metformin Attenuates Inflammation and Fibrosis in Thyroid-Associated Ophthalmopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Miao, N.; Xu, J.; Gan, X.; Xu, D.; Zhou, L.; Xue, H.; Zhang, W.; Lu, L. Metformin Prevents Renal Fibrosis in Mice with Unilateral Ureteral Obstruction and Inhibits Ang II-Induced ECM Production in Renal Fibroblasts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Śmieszek, A.; Tomaszewski, K.A.; Kornicka, K.; Marycz, K. Metformin Promotes Osteogenic Differentiation of Adipose-Derived Stromal Cells and Exerts Pro-Osteogenic Effect Stimulating Bone Regeneration. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohandas, S.; Gayatri, V.; Kumaran, K.; Gopinath, V.; Paulmurugan, R.; Ramkumar, K.M. New Frontiers in Three-Dimensional Culture Platforms to Improve Diabetes Research. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, F.; Pizzuti, V.; Marrazzo, P.; Pession, A.; Alviano, F.; Bonsi, L. Perinatal Stem Cell Therapy to Treat Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: A Never-Say-Die Story of Differentiation and Immunomodulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okere, B.; Alviano, F.; Costa, R.; Quaglino, D.; Ricci, F.; Dominici, M.; Paolucci, P.; Bonsi, L.; Iughetti, L. In vitro differentiation of human amniotic epithelial cells into insulin-producing 3D spheroids. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2015, 28, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghandour, F.; Kassem, S.; Simanovich, E.; Rahat, M.A. Glucose Promotes EMMPRIN/CD147 and the Secretion of Pro-Angiogenic Factors in a Co-Culture System of Endothelial Cells and Monocytes. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okkelman, I.A.; Dmitriev, R.I.; Foley, T.; Papkovsky, D.B. Use of Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) as a Timer of Cell Cycle S Phase. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0167385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Sahra, I.; Regazzetti, C.; Robert, G.; Laurent, K.; Le Marchand-Brustel, Y.; Auberger, P.; et al. Metformin, independent of AMPK, induces mTOR inhibition and cell-cycle arrest through REDD1. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 4366–4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundquist, I.; Al-Amily, I.M.; Abaraviciene, S.M.; Salehi, A. Metformin Ameliorates Dysfunctional Traits of Glibenclamide- and Glucose-Induced Insulin Secretion by Suppression of Imposed Overactivity of the Islet Nitric Oxide Synthase-NO System. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0165668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Jang, J. Construction of 3D hierarchical tissue platforms for modeling diabetes. APL Bioeng. 2021, 5, 041506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinnapaka, S.; Yang, K.S.; Flowers, Q.; Faisal, M.; Nerone, W.V.; Rubin, J.P.; Ejaz, A. Metformin Improves Stemness of Human Adipose-Derived Stem Cells by Downmodulation of Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) and Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase (ERK) Signaling. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wang, Y.; Wu, K.; Wang, X. Dual Effects of Metformin on Adipogenic Differentiation of 3T3-L1 Preadipocyte in AMPK-Dependent and Independent Manners. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Jia, X.; Fang, D.; Cheng, Y.; Zhai, Z.; Deng, W.; Du, B.; Lu, T.; Wang, L.; Yang, C.; et al. Metformin Inhibits Lipid Droplets Fusion and Growth via Reduction in Cidec and Its Regulatory Factors in Rat Adipose-Derived Stem Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irrechukwu, O.; Yeager, R.; David, R.; Ekert, J.; Saravanakumar, A.; Choi, C.K. Applications of microphysiological systems to disease models in the biopharmaceutical industry: Opportunities and challenges. Altex 2023, 40, 485–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostrzewski, T.; Cornforth, T.; ASnow, S.; Ouro-Gnao, L.; Rowe, C.; Large, E.M.; Hughes, D.J. Three-dimensional perfused human in vitro model of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ka, M.; Hawkins, E.; Pouponnot, C.; Duvillié, B. Modelling human diabetes ex vivo: a glance at maturity onset diabetes of the young. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1427413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, M.; Yu, H.; Jin, Y.; Mo, J.; Sui, J.; Qian, X.; Chen, T. Metformin Facilitates Osteoblastic Differentiation and M2 Macrophage Polarization by PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway in Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cells Int. 2022, 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmanci, S.; Dutta, A.; Cesur, S.; Sahin, A.; Gunduz, O.; Kalaskar, D.M.; Ustundag, C.B. Production of 3D Printed Bi-Layer and Tri-Layer Sandwich Scaffolds with Polycaprolactone and Poly (vinyl alcohol)-Metformin towards Diabetic Wound Healing. Polymers 2022, 14, 5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.-L.; Liu, L. Effect of metformin on stem cells: Molecular mechanism and clinical prospect. World J. Stem Cells 2020, 12, 1455–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Chen, J.-Y.; Guo, J.; Ma, T.; Weir, M.D.; Guo, D.; Shu, Y.; Lin, Z.-M.; Schneider, A.; Xu, H.H.K. Novel Calcium Phosphate Cement with Metformin-Loaded Chitosan for Odontogenic Differentiation of Human Dental Pulp Cells. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 2018, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, H.H.K.; Dai, Z.; Yu, K.; Xiao, L.; Schneider, A.; Weir, M.D.; Oates, T.W.; Bai, Y.; et al. Effects of Metformin Delivery via Biomaterials on Bone and Dental Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, L.; Farzin, A.; Ghasemi, Y.; Alizadeh, A.; Goodarzi, A.; Basiri, A.; Zahiri, M.; Monabati, A.; Ai, J. Metformin-Loaded PCL/PVA Fibrous Scaffold Preseeded with Human Endometrial Stem Cells for Effective Guided Bone Regeneration Membranes. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 7, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smieszek, A.; Kornicka, K.; Szłapka-Kosarzewska, J.; Androvic, P.; Valihrach, L.; Langerova, L.; Rohlova, E.; Kubista, M.; Marycz, K. Metformin Increases Proliferative Activity and Viability of Multipotent Stromal Stem Cells Isolated from Adipose Tissue Derived from Horses with Equine Metabolic Syndrome. Cells 2019, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śmieszek, A.; Szydlarska, J.; Mucha, A.; Chrapiec, M.; Marycz, K. Enhanced cytocompatibility and osteoinductive properties of sol–gel-derived silica/zirconium dioxide coatings by metformin functionalization. J. Biomater. Appl. 2017, 32, 570–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.-H.; Sun, C.-K.; Lin, Y.-W.; Hung, M.-C.; Lin, H.-Y.; Li, C.-H.; Lin, I.-P.; Chang, H.-C.; Sun, J.-S.; Chang, J.Z.-C. Metformin-Incorporated Gelatin/Nano-Hydroxyapatite Scaffolds Promotes Bone Regeneration in Critical Size Rat Alveolar Bone Defect Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf Aliyu, A.; Adeleke, O.A. Nanofibrous Scaffolds for Diabetic Wound Healing. Pharmaceutics. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Madden, L.A.; Paunov, V.N. Enhanced anticancer effect of lysozyme-functionalized metformin-loaded shellac nanoparticles on a 3D cell model: role of the nanoparticle and payload concentrations. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 12, 4735–4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallaglio, K.; Bruno, A.; Cantelmo, A.R.; Esposito, A.I.; Ruggiero, L.; Orecchioni, S.; Calleri, A.; Bertolini, F.; Pfeffer, U.; Noonan, D.M.; et al. Paradoxic effects of metformin on endothelial cells and angiogenesis. Carcinog. 2014, 35, 1055–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, C.; Rodrigues, I.; Andrade, S.; Costa, R.; Soares, R. Metformin Reduces Vascular Assembly in High Glucose-Treated Human Microvascular Endothelial Cells in An AMPK-Independent Manner. Cell J. 2021, 23, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundewar, S.; Calvert, J.W.; Jha, S.; Toedt-Pingel, I.; Ji, S.Y.; Nunez, D.; Ramachandran, A.; Anaya-Cisneros, M.; Tian, R.; Lefer, D.J. Activation of AMP-Activated Protein Kinase by Metformin Improves Left Ventricular Function and Survival in Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 2009, 104, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disease Models | Effects of Metformin | Key Mechanisms | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CANCER | Reduces sphere-forming ability | Upregulates integrin β1 expression | [59] | |

| Targets cancer stem/progenitor cells | Inhibits stemness pathways | [60,61] | ||

| Decreases invasive capacity | Disrupts large single-cluster formations in multicellular spheroids | [62,63] | ||

| Inhibits cell migration and invasion | Enhances ECM adhesion | [64,65] | ||

| FIBROSIS | Reduces ECM production [collagen types I and III, elastin, hyaluronic acid] | Decreases COL1A1, COL3A1, elastin, and hyaluronic acid expression | [3,70] | |

| Suppresses fibroblast to myofibroblast transformation | Decreases α-SMA expression and inhibits TGF-β, PDGF-β, and SMAD-2 signaling | [3,45,71] | ||

| Promotes fibrosis reversion | Induces AMPK activation and phenotypic switch to lipo-fibroblasts via BMP-2 and PPAR-γ phosphorylation | [74,75] | ||

| Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases | Inhibits cell proliferation in intestinal organoids | AMPK activation and p53-dependent activation of REDD1 lead to mTOR inhibition and cell cycle arrest | [84,85] | |

| Protects pancreatic beta cells | Maintains cell viability under high glucose conditions and prevents fatty acid-induced apoptosis via AMPK-mediated autophagy | [86,87] | ||

| Impairs adipogenesis | Enhances stemness in adipose-derived stem cells via autophagy activation and mTOR inhibition | [88] | ||

| Reduces liver lipid content | Exhibits anti-steatotic properties by lowering fatty acid consumption | [91,92] | ||

| Application | Effects of Metformin | Key Mechanisms | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Regeneration | Stimulates osteogenesis in mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) | Enhances differentiation into osteoblasts, regulates immune responses (M1 to M2 macrophage shift) | [94] |

| Wound Healing | Enhances healing, increases angiogenesis, improves epithelialization, promotes hair follicle formation & collagen deposition | Immunomodulatory & anti-inflammatory effects | [95] |

| Bone Tissue Engineering | Improves osteogenic differentiation & bone formation | Calcium phosphate cement scaffolds & polylactic acid/polycaprolactone composites | [96] |

| Dental Tissue Engineering | Supports dental pulp cell viability & enhances odontogenic differentiation | Calcium phosphate cement-chitosan composites | [97] |

| Periodontal Regeneration | Enhances bone regeneration | Polycaprolactone/polyvinyl alcohol membranes with 10 wt% metformin | [98,99] |

| Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Defects | Improves clinical outcomes in bone defect treatments | Metformin-loaded scaffolds | [98] |

| Implant Integration | Enhances cell proliferation & metabolic activity of adipose-derived stem cells | Sol-gel coatings with metformin for metallic implants | [100,101] |

| Diabetic Wound Healing | Accelerates healing, reduces inflammation, improves dermis & epidermis regeneration | Composite scaffolds (chitosan/gelatin/polycaprolactone, polyvinyl pyrrolidone nanofibers) | [103] |

| Controlled Drug Delivery | Provides sustained metformin release, improves wound healing rates | Collagen/PLGA nanofibrous scaffold membranes | [103] |

| Cancer Therapy | Enhances drug penetration & anticancer effects | Lysozyme-functionalized metformin-loaded nanoparticles modifying ECM | [104] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).