Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

16 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experiments and Methods

2.1. Materials and Preparations

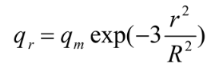

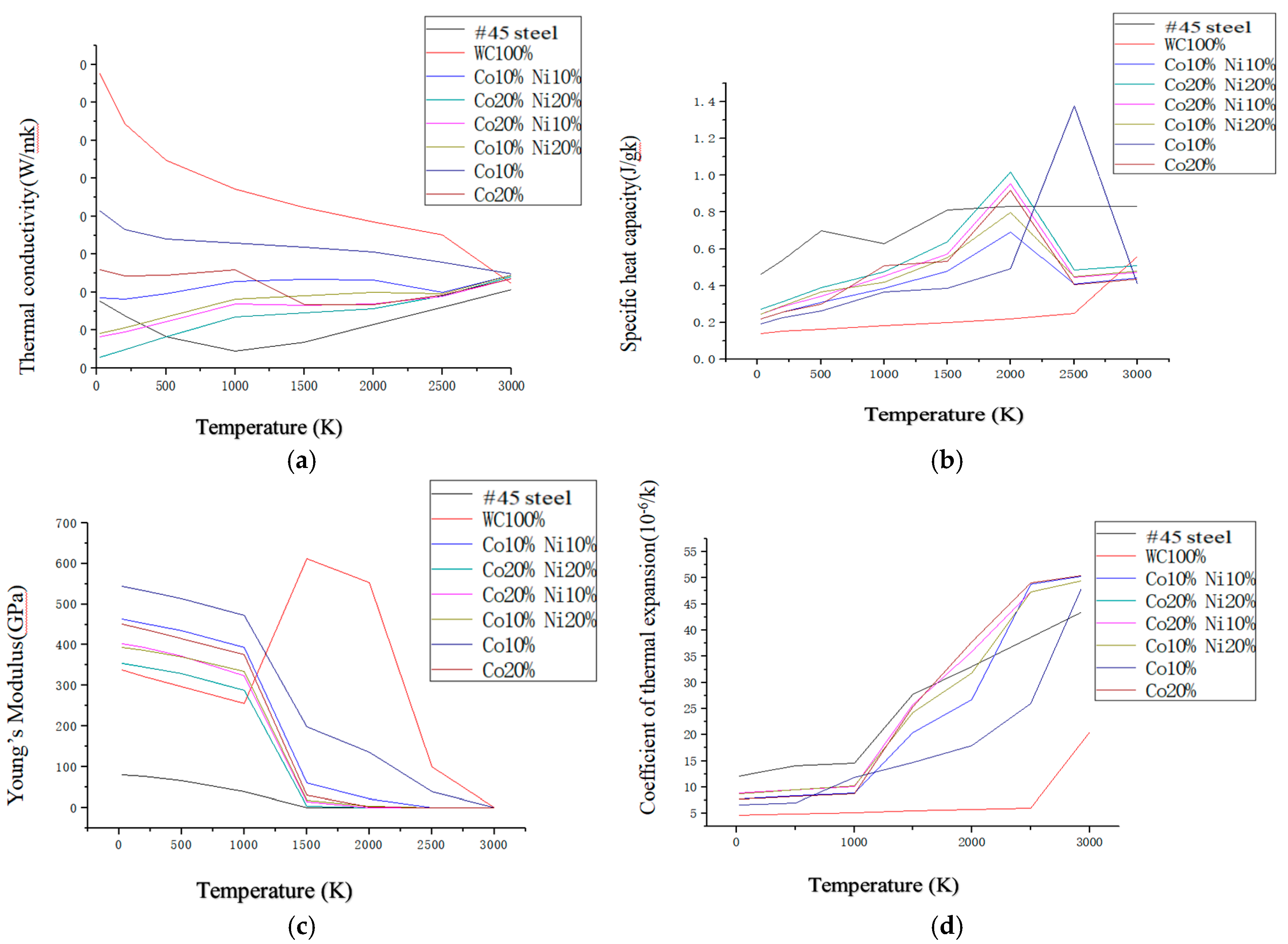

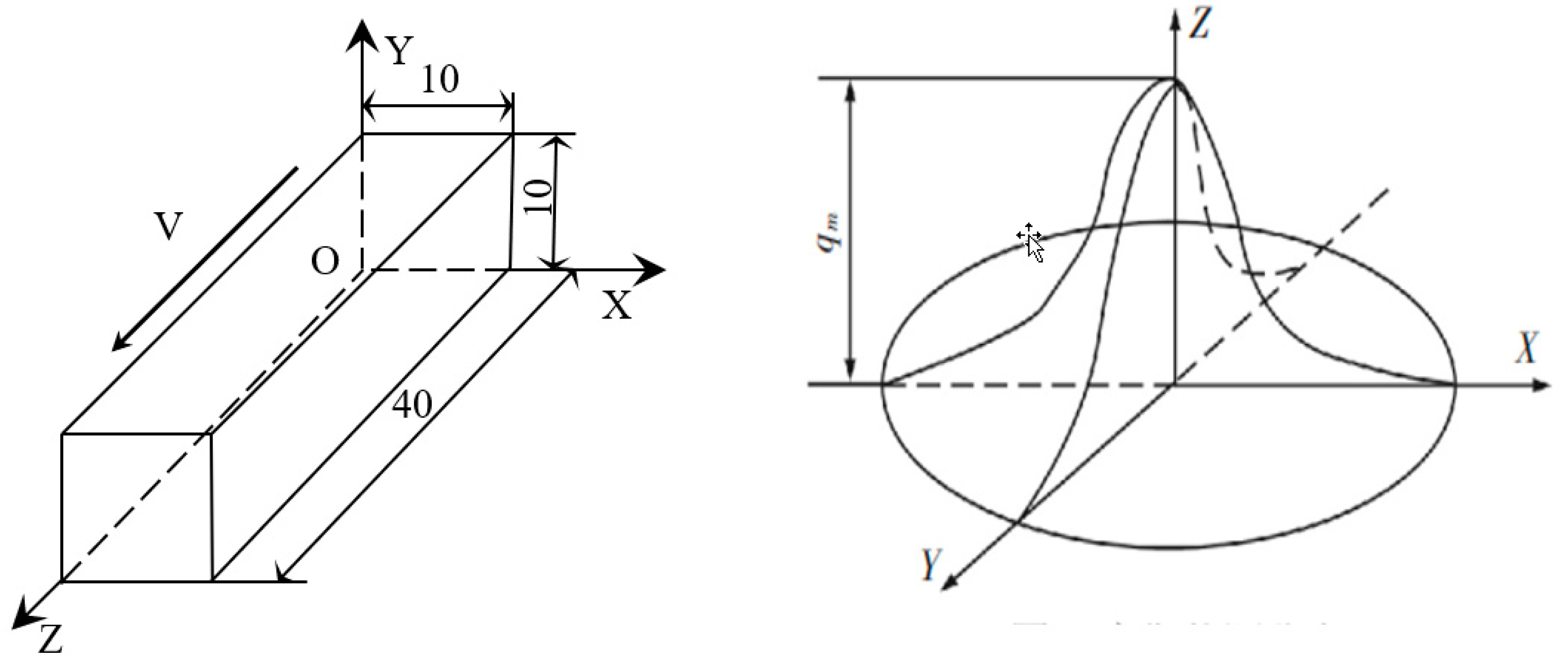

2.2. Finite Element Models

- The heat flow density q(x,y,t) of a Gaussian heat source in a two-dimensional plane, assuming that the heat source is moving along the z-axis with velocity v, is given by the following equation:

- The equation for the heat flow density q(x,y,z,t) for a moving Gaussian heat source in three dimensions, assuming that the heat source is moving along the z-axis with velocity v, is:where q(x,y,z,t) is the density of heat flow, Q is the total laser power, R0 is the radius of the laser spot, v is the moving speed of the heat source, h is the depth of the heat source, t is the time, and x, y, and z are the coordinates in space. In this study, WC (Co,Ni) composite coatings were used in simulations and experiments.

- ESEL, S,MAT,, 2

- EPLOT Killed all the units

- EKILL, ALL

- EPLOT

- EPLOT

- EALIVE, ALL

- CM,E_1, ELEM Activation of units at the scan of the laser

- CM,N_1,NODE

2.3. Response Surface Methodology

3. Experimental Results and Discussion

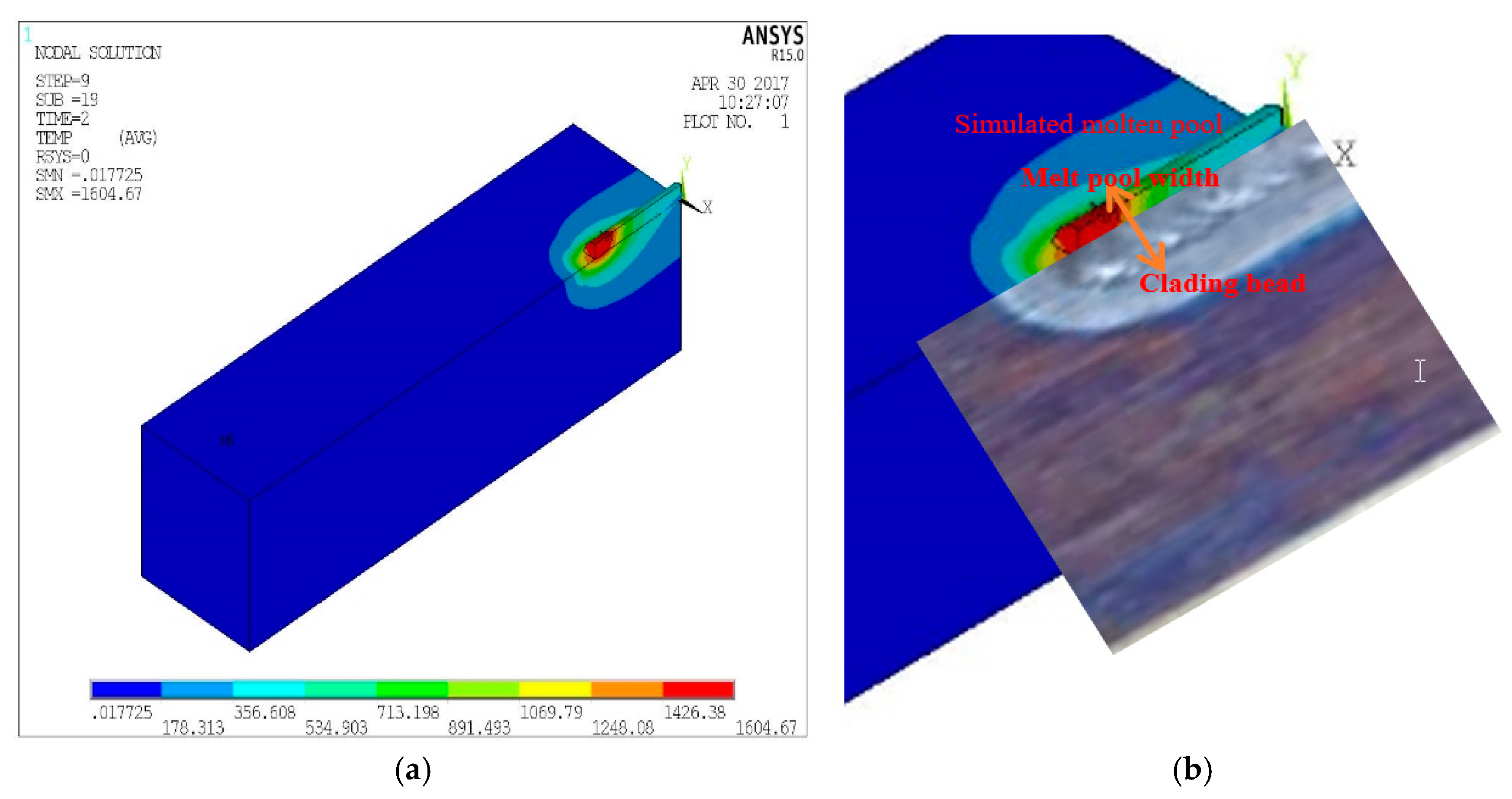

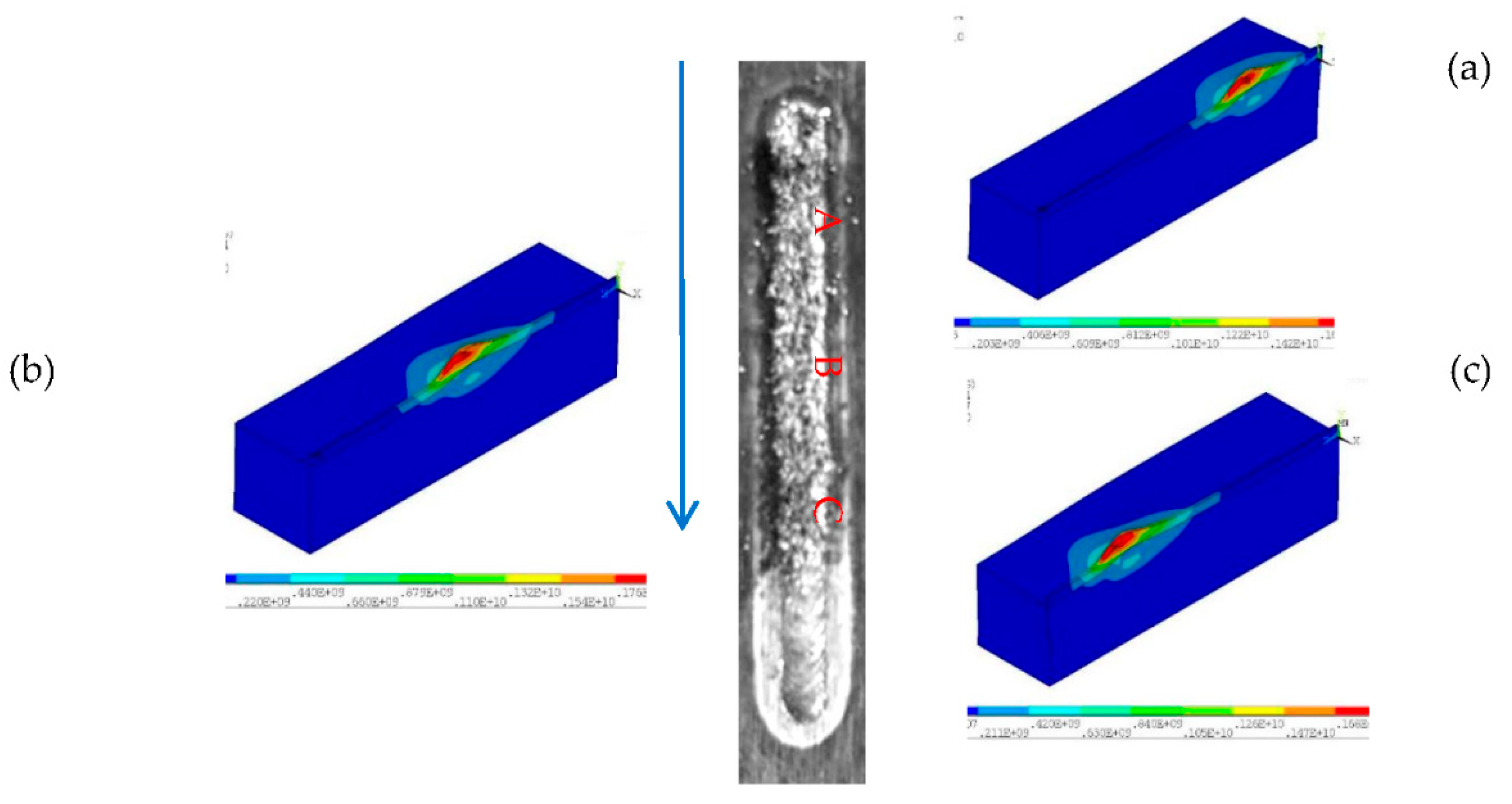

3.1. Validation of Models in Finite Element Analysis

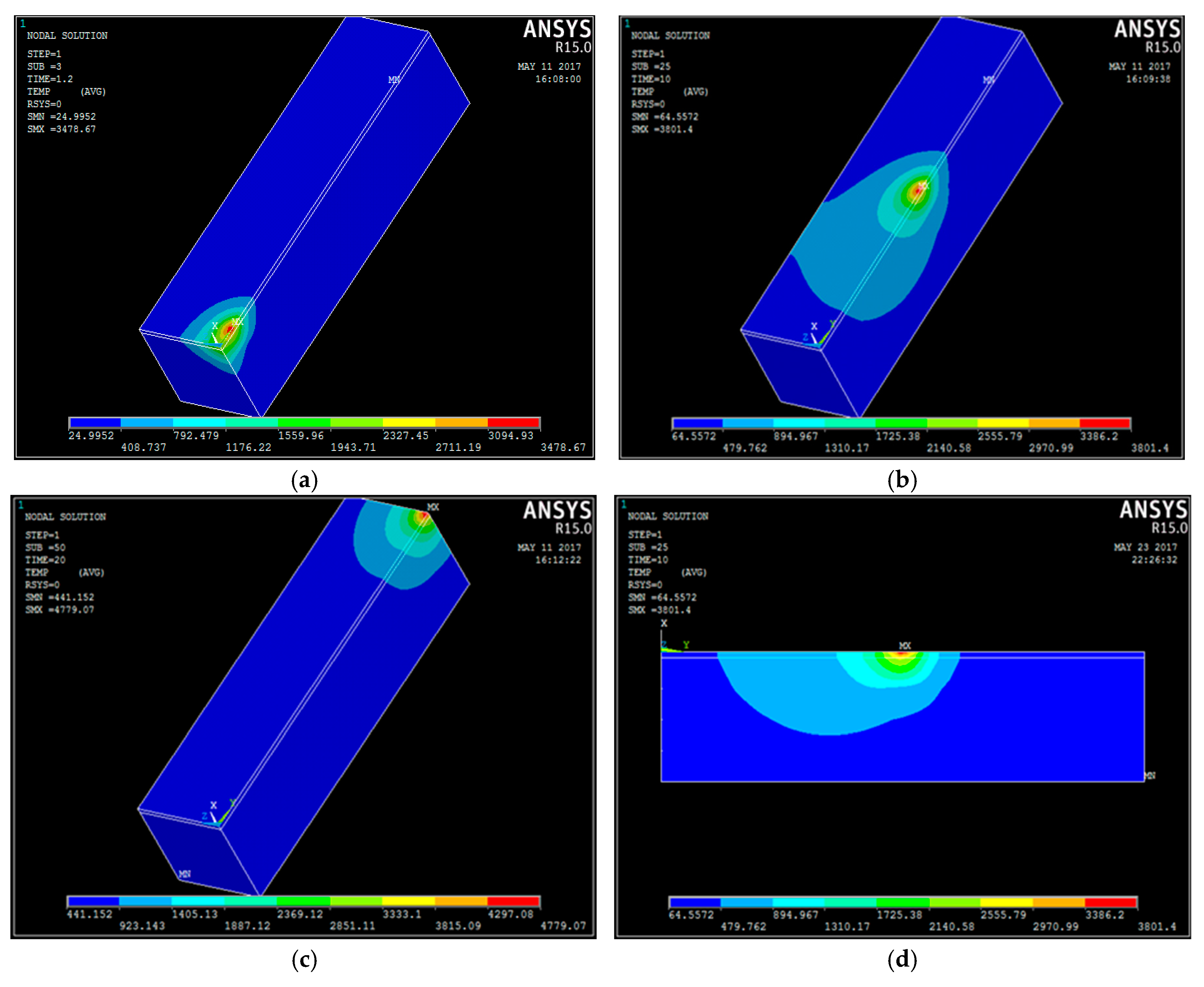

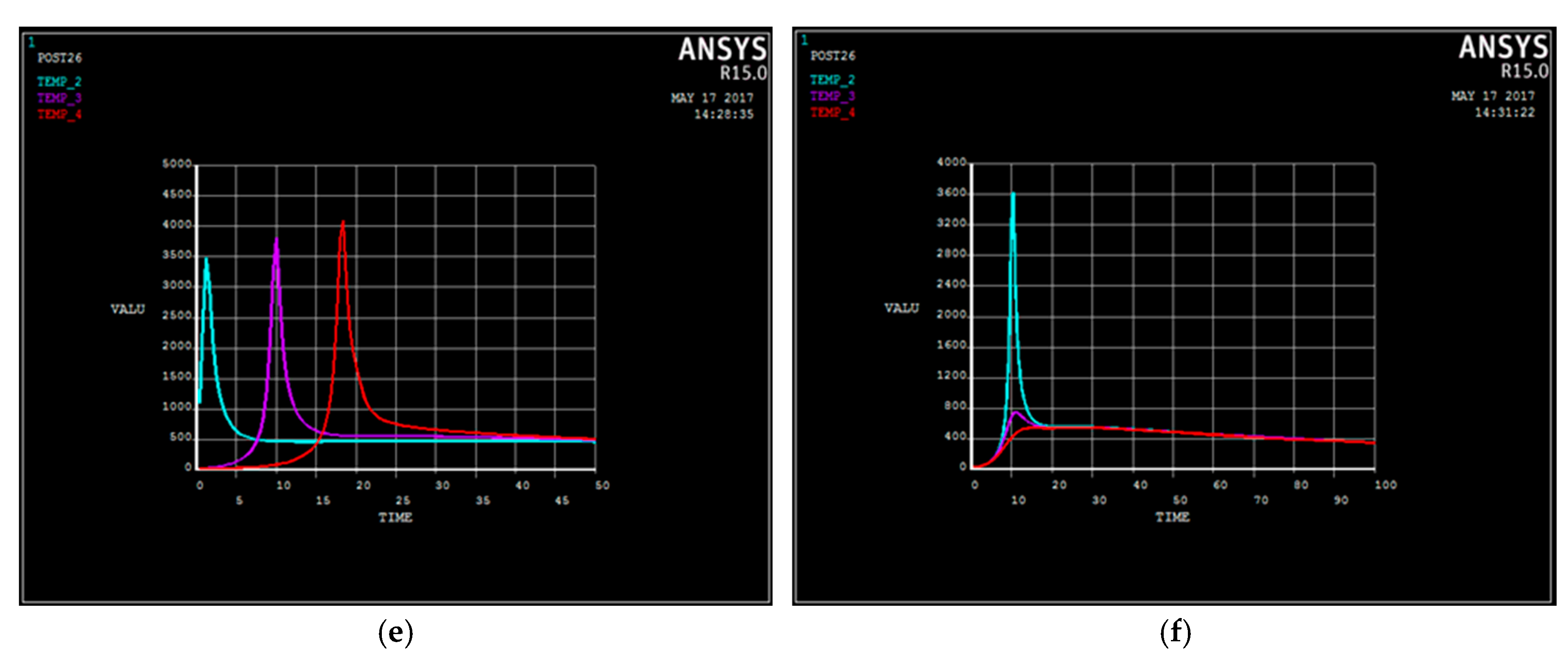

3.2. Validation of Temperature Field in Finite Element Analysis

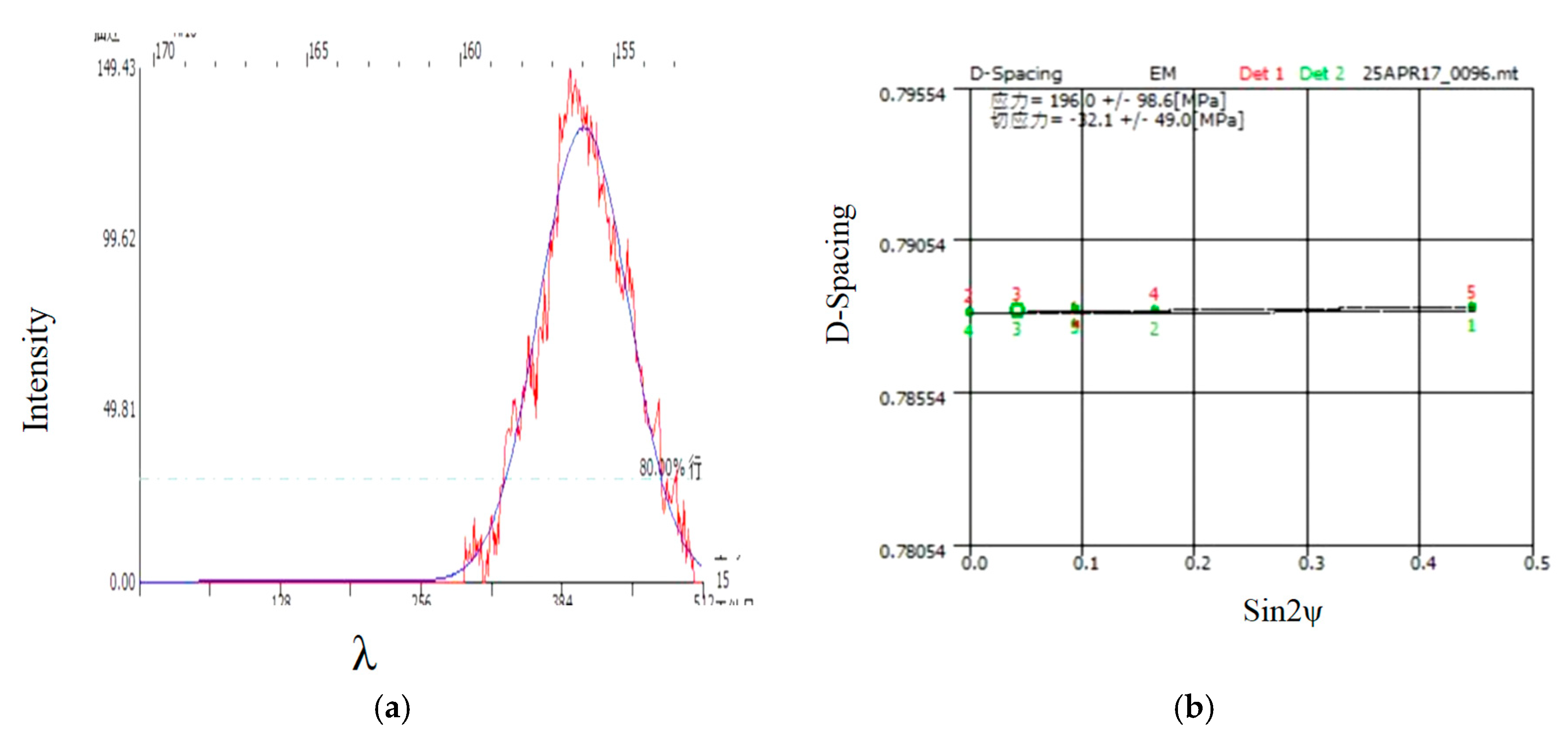

3.3. Evaluation of Residual Stress

3.4. Evolution of Microstructure in the WC(Co,Ni) Welds

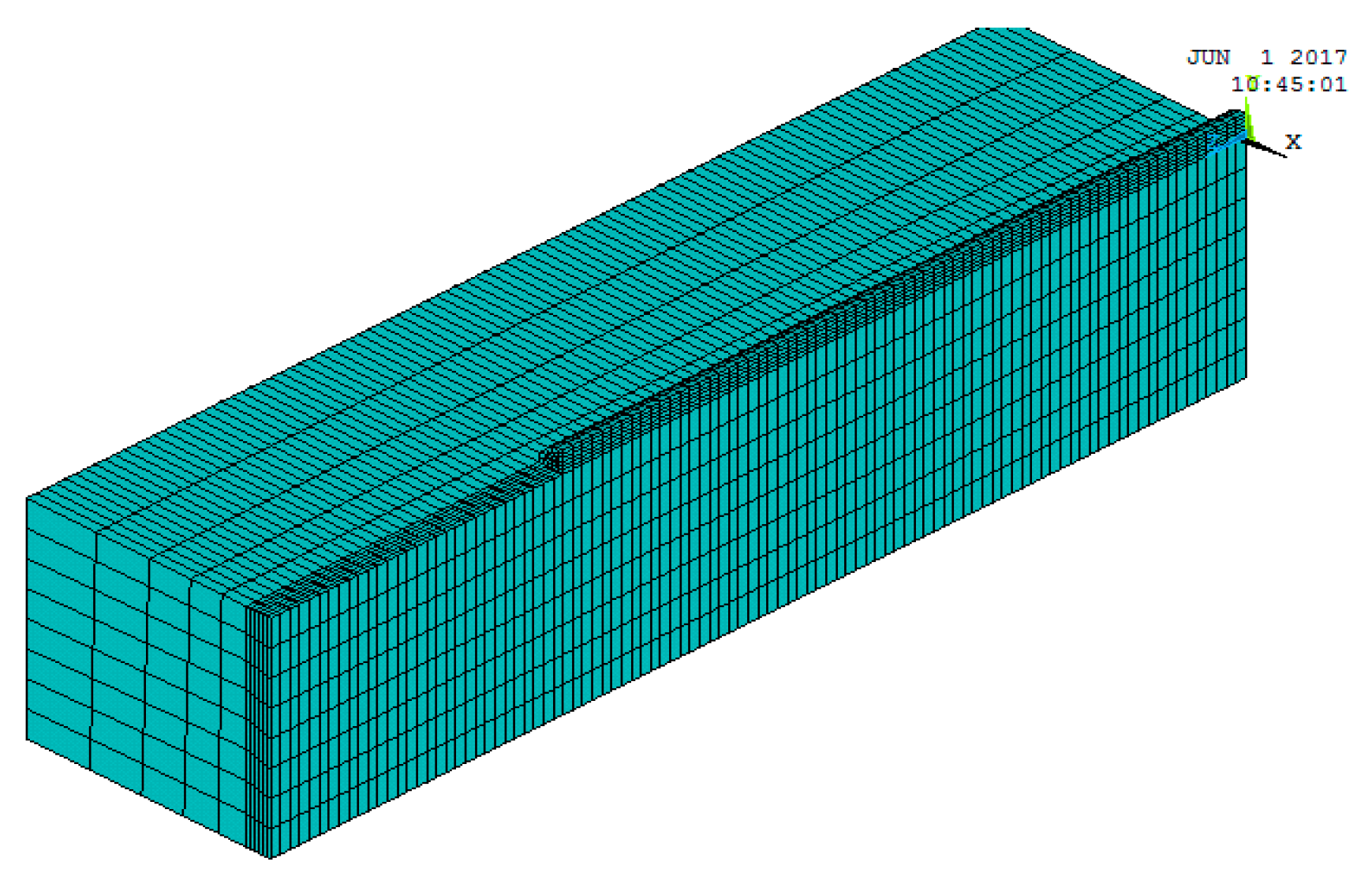

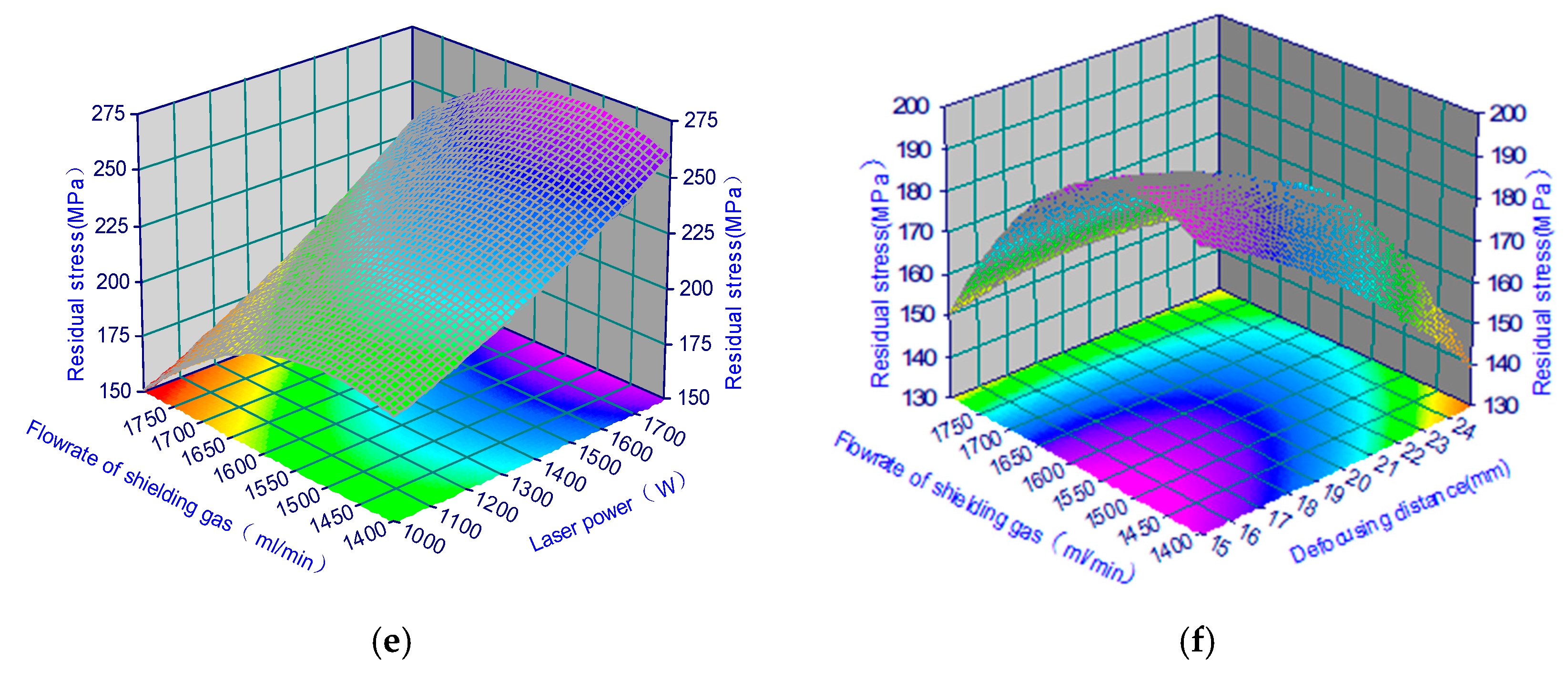

3.5. Effect of Control Factors on Residual Stress Properties

3.6. Construction of Empirical Models

3.7. Effects of Variables on Modeling of Residual Stresses

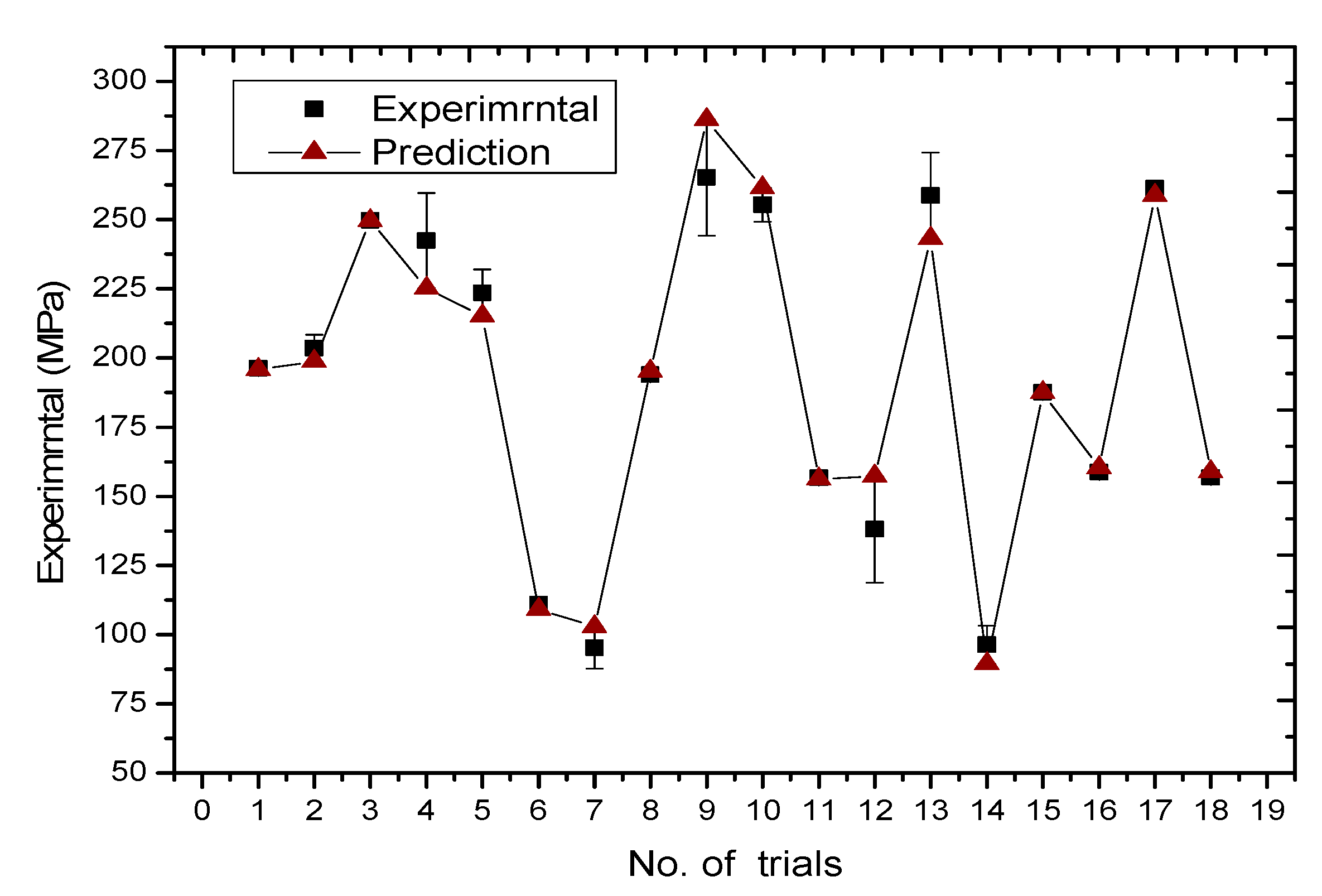

3.8. Analysis of Model Confirmation Experiments

5. Concluding Remarks

- The temperature field and stress field of the coating were investigated by the simulation based on finite element analysis. The temperature field of WC(Co,Ni) alloy by laser cladding is a dynamical temperature field, which has the same thermal cycling curves at each node, only the sequence of time is different.

- Using the parametric design language of ANSYS software, a model of laser melting WC(Co,Ni) welds with continuous loading of a moving laser spot was established. Through this model, the distribution pattern of the temperature field and stress field can be derived during solidification by laser coaxial powders.

- The white areas of the WC(Co,Ni) melting zone are dominated by carbides with more than 80% of W while the C is about 1.5-3.0%. In addition, the large area of the melting zone is composed of dendritic, strip-like, leaf-like, net-like, and smaller clustered carbides, while the grey area is composed of WC,Co and Ni compounds.

- The ANOVA results based on the experimental design showed that the effects of the four variables on residual stress were very significant. Among them, the factors including preheated temperature, laser power, defocusing distance and the flow rate of shielding gas exhibited notable effects, which accounted for 90.46% of the total variance.

- The relationship between the parameters and the residual stresses was established by applying the response surface methodology. By optimizing the design and using RSM model, the residual stress performance of the coating was improved.

- A comparison of all the experiments showed that the average error of the quadratic function was 6.52%, while the prediction error of the model was not more than twice the standard deviation of the experimental values. This means that the predicted values are very close to the experimental values, indicating that the model is credible.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- R. Suryanarayanan. (1993). Plasma Spraying: Theory and Applications. WORLD SCIENTIFIC.

- Y. Huang, X. Zeng. (2010). Investigation on cracking behavior of Ni-based coating by laser-induction hybrid cladding. Applied Surface Science, 256(20), 5985-5992.

- U.D. Oliveira, V. Ocelík, J.T.M.D. Hosson. (2006). Residual stress analysis in Co-based laser clad layers by laboratory X-rays and synchrotron diffraction techniques. Surface & Coatings Technology, 201(3-4), 533-542.

- G. Sun, R. Zhou, J. Lu, J. Mazumder. (2015). Evaluation of defect density, microstructure, residual stress, elastic modulus, hardness and strength of laser-deposited AISI 4340 steel. Acta Materialia, 84(84), 172-189.

- M. Afzal, M. Ajmal, A.N. Khan, A. Hussain, R. Akhter. (2014). Surface modification of air plasma spraying WC–12%CO cermet coating by laser melting technique. Optics & Laser Technology, 56(1), 202-206.

- G. Montay, A. Cherouat, A. Nussair, J. Lu. (2004). Residual stresses in coating technology. Journal of Materials Science & Technology, 20(Supl.), 81-84.

- J. Qian, Y. Yin, T.J. Li, X.T. Hu, C.Wang, S.Q. Li. (2015). Structure, micro-hardness and corrosion behaviour of the AL–SI/AL 2 O 3, coatings prepared by laser plasma hybrid spraying on magnesium alloy.Vacuum, 117, 55-59.

- C.Z. Chen, T.Q. Lei, Q.H. Bao, S.S. Yao. (2002). Problems and the improving measures in laser remelting of plasma sprayed ceramic coatings. Material Science & Technology. 431-435.

- P. Wen, Z. Feng, S. Zheng. (2015). Formation quality optimization of laser hot wire cladding for repairing martensite precipitation hardening stainless steel. Optics & Laser Technology, 65, 180-188.

- P. Farahmand, R. Kovacevic. (2015). Laser cladding assisted with an induction heater (LCAIH) of NI–60%WC coating. Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 222, 244-258.

- M. Afzal, A.N. Khan, T.B. Mahmud, T.I. Khan, M. Ajmal. (2015). Effect of Laser Melting on Plasma Sprayed WC-12 wt.%Co Coatings. Surface & Coatings Technology, 266, 22-30.

- M. Rakhes, E. Koroleva, Z. Liu. (2010). Improvement of Corrosion Performance of HVOF MMC Coatings by Laser Surface Treatment. Proceedings of the 36th International MATADOR Conference. Springer London. 729-733.

- Q. Luo, A.H. Jones. (2010). High-precision determination of residual stress of polycrystalline coatings using optimised XRD-sin 2 ψ technique. Surface & Coatings Technology, 205(5), 1403-1408.

- W. Luo, U. Selvadurai, W. Tillmann. (2016). Effect of Residual Stress on the Wear Resistance of Thermal Spray Coatings. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology, 25(1), 321-330.

- M.S. Zoei, M.H. Sadeghi, M. Salehi. (2016). Effect of grinding parameters on the wear resistance and residual stress of HVOF-deposited WC-10Co-4Cr coating. Surface & Coatings Technology, 307, 886-891.

- J.M. Guilemany, S. Dosta, J.R. Miguel. (2006). The enhancement of the properties of WC-Co HVOF coatings through the use of nanostructured and microstructured feedstock powders. Surface & Coatings Technology, 201(3), 1180-1190.

- P. Kapadia, C. Davies, T. Pirling, M. Hofmann, R. Wimpory, F. Hosseinzadeh, D. Dean, K. Nikbin. (2017). Quantification of residual stresses in electron beam welded fracture mechanics specimens. International Journal of Solids & Structures, s 106–107, 106-118.

- R. Stadelmann, M. Lugovy, N. Orlovskaya, P. Mchaffey, M. Radovic, V.M. Sglavo, S. Grasso, M.J. Reece. (2016). Mechanical properties and residual stresses in ZrB2–SiC spark plasma sintered ceramic composites. Journal of the European Ceramic Society, 36(7), 1527-1537.

- Liu, S.; Zhu, H.; Peng, G.; Yin, J.; Zeng, X. Microstructure prediction of selective laser melting AlSi10Mg using finite element analysis. Mater. Des. 2018, 142, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yin, J.; Zhu, H.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zeng, X. Effect of overlap rate and pattern on residual stress in selective laser melting. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2019, 145, 103433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, M.; Fallah, M.M.; Kazerooni, A. The influence of hatch distance on the surface roughness, microhardness, residual stress, and density of inconel 625 specimens in the laser powder bed fusion process. Adv. Mater. Process. Technol. 2024, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah V, Alimardani M, Corbin S. F., et al. Temporal Development of Melt-Pool Morphology and Clad Geometry in Laser Powder Deposition. Computational Materials Science, 2011, 50(7): 2124-2134.

- C. Wang, C. Jiang, V. J., Thermal stability of residual stresses and work hardening of shot peened tungsten cemented carbide. Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 2016, 240, 98–103.

- Gao, J.L., Wu Ch-zu, HAO Yun-bo, et al. Numerical Simulation and Experimental Investigation on Three-Dimensional Modelling of Single-Track Geometry and Temperature Evolution by Laser Cladding. Optics & Laser Technology, 2020, 129: 106287.

- Li C, Yu Z. B, Gao J.X. et al. Numerical Simulation and Experimental Study on the Evolution of Multi-Field Coupling in Laser Cladding Process by Disk Lasers. Welding in the World, 2019, 63(4): 925-945.

- Andrzej Wójcik, Kamil Jonak, Robert Karpi´nski, Józef Jonak, Marek Kalita and Dariusz Prosta´nski. Mechanism of Rock Mass Detachment Using Undercutting Anchors: A Numerical Finite Element Method (FEM) Analysis. Materials 2024, 17, 4468. [CrossRef]

- C. W. Liu, M. D. Jean, Q. T. Wang, Optimization of residual stresses in laser-mixed WC(Co,Ni) coatings. Strength of Materials, 2019,51(1): 95-101.

- Liu, H.M. Qin X.P. Wu M.W. et al. Numerical Simulation of Thermal and Stress Field of Single Track Cladding in Wide-Beam Laser Cladding. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 2019, 104(9): 3959-3976.

- Song, J. Chew Y. Bi G.J. et al., Numerical and Experimental Study of Laser Aided Additive Manufacturing for Melt-Pool Profile and Grain Orientation Analysis. Materials & Design, 2018, 137: 286-297.

- Heeling, T. Cloots M. Wegener K. Melt Pool Simulation for the Evaluation of Process Parameters in Selective Laser Melting. Additive Manufacturing, 2017, 14: 116-125.

- Jin, P. Tang Q. Song J. et al. Numerical Investigation of the Mechanism of Interfacial Dynamics of the Melt Pool and Defects during Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Optics & Laser Technology, 2021, 143: 107289.

- Tian, H.C. Chen X.D. Yan Z.H. et al. Finite-Element Simulation of Melt Pool Geometry and Dilution Ratio during Laser Cladding. Applied Physics A, 2019, 125(7): 485.

- Gan, Z.T. Yu G. He X.L. et al. Numerical Simulation of Thermal Behavior and Multicomponent Mass Transfer in Direct Laser Deposition of Co-Base Alloy on Steel. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 2017, 104: 28-38.

- Jiaqi Zhang, Jianbo Lei, Zhenjie Gu, Fanliang Tantai, Hongfang Tian, Jiajie Han, Yan Fang. Effect of WC-12Co content on wear and electrochemical corrosion properties of Ni-Cu/WC-12Co composite coatings deposited by laser cladding. Surface and Coatings Technology, 393, 2020, 125807.

- Lin, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zuo, S.; Cai, X.; Feng, K.; Wang, K.; Wei, H.; Xiao, F.; Jin, X. Controlling the crystal texture and microstructure of NiTi alloy by adjusting the thermal gradient of laser powder bed melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 912, 146970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu L, Huang M. Ma Y. H. et al. Simulation of Powder Packing and Thermo-Fluid Dynamic of 316L Stainless Steel by Selective Laser Melting. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance, 2020, 29(11): 7369-7381.

- Zhang J.Q., Lei J.B., Gu Z.J., Tantai F.L. Tian H.F. Han.J.J. Fang Y. Effect of WC-12Co content on wear and electrochemical corrosion properties of Ni-Cu/WC-12Co composite coatings deposited by laser cladding. Surface and Coatings Technology, 393, 2020, 125807.

- Cheng P., Tuo S, Fu G.Y. et al. Study on Temperature Control of Powdered Pool in Hollow Laser Light. Machine Building & Automation, 2021, 50(2): 99-101.

- Marques, B.M.; Andrade, C.M.; Neto, D.M.; Oliveira, M.C.; Alves, J.L.; Menezes, L.F. Numerical Analysis of Residual Stresses in Parts Produced by Selective Laser Melting Process. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 47, 1170–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. H. Myers, D. C. Montgomery, C. M. Anderson-Cook. Response surface methodology: Process and Product Optimization Using Designed Experiments. 3rd ed, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. 2009.

- B.T. Lin, M.D. Jean, J.H. Chou (2007). Using response surface methodology for optimizing deposited partially stabilized zirconia in plasma spraying. Applied Surface Science, 253(6), 3254-3262.

- Y. Sun, M. Hao. (2012). Statistical analysis and optimization of process parameters in TI6AL4V laser cladding using Nd:YAG laser. Optics & Lasers in Engineering, 50(7), 985-995.

- Helia Mohammadkamal and Fabrizia Caiazzo. Numerical Study to Analyze the Influence of Process Parameters on Temperature and Stress Field in Powder Bed Fusion of Ti-6Al-4V. Materials 2025, 18, 368. [CrossRef]

| No. of trials | Control factors and levels | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate | Ratio of Co (%) |

Ratio of Ni (%) |

Preheated temperature (℃) |

Laser power (W) |

Scannig speed (mm/sec) |

Defocusing distance (mm) |

Flowrate of shielding gas(ml/min) | |

| 1 | #45 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 1000 | 2 | 15 | 1400 |

| 2 | #45 | 0 | 10 | 100 | 1400 | 4 | 20 | 1600 |

| 3 | #45 | 0 | 20 | 200 | 1800 | 6 | 25 | 1800 |

| 4 | #45 | 10 | 0 | 25 | 1400 | 6 | 25 | 1600 |

| 5 | #45 | 10 | 10 | 100 | 1800 | 2 | 15 | 1800 |

| 6 | #45 | 10 | 20 | 200 | 1000 | 4 | 20 | 1400 |

| 7 | #45 | 20 | 0 | 100 | 1000 | 4 | 25 | 1800 |

| 8 | #45 | 20 | 10 | 200 | 1400 | 6 | 15 | 1400 |

| 9 | #45 | 20 | 20 | 25 | 1800 | 2 | 20 | 1600 |

| 10 | #40Cr | 0 | 0 | 200 | 1800 | 4 | 15 | 1600 |

| 11 | #40Cr | 0 | 10 | 25 | 1000 | 6 | 20 | 1800 |

| 12 | #40Cr | 0 | 20 | 100 | 1400 | 2 | 25 | 1400 |

| 13 | #40Cr | 10 | 0 | 100 | 1800 | 6 | 20 | 1400 |

| 14 | #40Cr | 10 | 10 | 200 | 1000 | 2 | 25 | 1600 |

| 15 | #40Cr | 10 | 20 | 25 | 1400 | 4 | 15 | 1800 |

| 16 | #40Cr | 20 | 0 | 200 | 1400 | 2 | 20 | 1800 |

| 17 | #40Cr | 20 | 10 | 25 | 1800 | 4 | 25 | 1400 |

| 18 | #40Cr | 20 | 20 | 100 | 1000 | 6 | 15 | 1600 |

| No. of trials | W | C | O | Fe | Ni | Co | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial7 | A | 94.43 | 2.08 | 1.87 | 1.17 | 0.00 | 0.068 |

| B | 92.08 | 1.53 | 3.12 | 2.81 | 0.00 | 0.28 | |

| C | 90.74 | 1.32 | 4.37 | 2.93 | 0.00 | 0.25 | |

| Trial9 | A | 88.85 | 1.61 | 1.08 | 3.12 | 2.89 | 2.15 |

| B | 25.00 | 2.34 | 6.49 | 5.84 | 27.92 | 32.08 | |

| C | 66.22 | 1.93 | 4.48 | 3.76 | 11.95 | 11.11 | |

| Trial 14 | A | 89.98 | 2.97 | 1.54 | 2.42 | 1.479 | 0.99 |

| B | 38.02 | 4.09 | 5.98 | 33.36 | 6.49 | 11.49 | |

| C | 30.01 | 4.99 | 7.14 | 36.07 | 9.60 | 11.30 | |

| Trial17 | A | 91.86 | 1.55 | 1.03 | 0.53 | 2.32 | 2.49 |

| B | 84.00 | 0.99 | 1.74 | 0.71 | 3.46 | 9.02 | |

| C | 46.27 | 1.74 | 12.66 | 3.37 | 5.81 | 28.91 | |

| Control factors |

Sum of squares |

Degrees of Freedom |

Mean square |

F-value | Percent contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1.323 | 1.0 | 1.323 | 0.542 | 0.89 |

| B | 3.222 | 2.0 | 1.611 | 0.660 | 2.17 |

| C | 1.419 | 2.0 | 0.710 | 0.291 | 0.96 |

| D | 17.917 | 2.0 | 8.958 | 3.671 | 12.07 |

| E | 98.303 | 2.0 | 49.152 | 20.144 | 66.21 |

| F | 3.262 | 2.0 | 1.631 | 0.669 | 2.20 |

| G | 9.610 | 2.0 | 4.805 | 1.969 | 6.47 |

| H | 8.529 | 2.0 | 4.264 | 1.748 | 5.74 |

| Error | 4.880 | 2.0 | 2.440 | 1.000 | 3.29 |

| Total | 148.466 | 17.0 | 8.733 | 3.579 | 100.00 |

| Source | Degree of freedom | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F-test | Prob< F | Adjust-R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear model | 4 | 47617.08 | 11904.27 | 16.00383 | 6.08E-05 | 0.779 |

| Interaction model | 10 | 53161.47 | 5316.147 | 9.020209 | 0.004006 | 0.822 |

| quadratic model | 14 | 55681.99 | 3977.285 | 7.434195 | 0.00621 | 0.841 |

| Source | Quadratic model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient Estimate |

Standard error | t-statistical | Prob > F | |

| Intercept | -563.727 | 936.196 | -0.602 | 0.590 |

| D | -0.757 | 1.283 | -0.590 | 0.597 |

| E | -0.176 | 0.361 | -0.486 | 0.660 |

| G | -22.983 | 30.477 | -0.754 | 0.506 |

| H | 1.372 | 1.078 | 1.272 | 0.293 |

| DE | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.977 | 0.401 |

| DG | -0.014 | 0.026 | -0.551 | 0.620 |

| DH | 0.000 | 0.001 | -0.066 | 0.951 |

| EG | 0.006 | 0.006 | 1.121 | 0.344 |

| EH | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.336 | 0.759 |

| GH | 0.014 | 0.011 | 1.222 | 0.309 |

| D2 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 1.131 | 0.340 |

| E2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.404 | 0.714 |

| G2 | -0.195 | 0.499 | -0.390 | 0.723 |

| H2 | -0.001 | 0.000 | -1.759 | 0.177 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).