Submitted:

19 May 2025

Posted:

19 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

- [6]

- built a XGBoost model to predict the NBA game results using the game data from 2021-2023 NBA seasons. The study used the SHAP values to explain the predictions and revealed that the key indicators were field goal percentage, defensive rebounds, and turnovers [6]. [6] recommended exploring different factors such as team tactics, player injuries, and game schedule in future studies.

- [7]

- built two-stage XGBoost models using the game data from the 2018-2019 season to predict the final scores of the games. The study found that the important features were related to the team’s average performance such as rebounds, field goal percentage, free throw percentage, and assists [7]. [7] mentioned that the model input was limited to only one season and recommended using stable feature selection techniques and incorporating features such as opponent information and game schedules.

- [8]

- built the Maximum Entropy model using the game statistics such as three-points or two-points field goal percentage, free throw percentage, and rebounds to predict the outcomes of playoff games. In the study, the mean of the game statistics was calculated for the most recent six games prior to the game that was being predicted [8]. [8] noted that the first game was excluded from prediction due to the absence of the prior data. [8] also mentioned that the model did not include information around relative strengths between the teams, injured players, and coaches’ directions.

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

3.2. Model Selection and Training

3.3. Model Evaluation and Validation

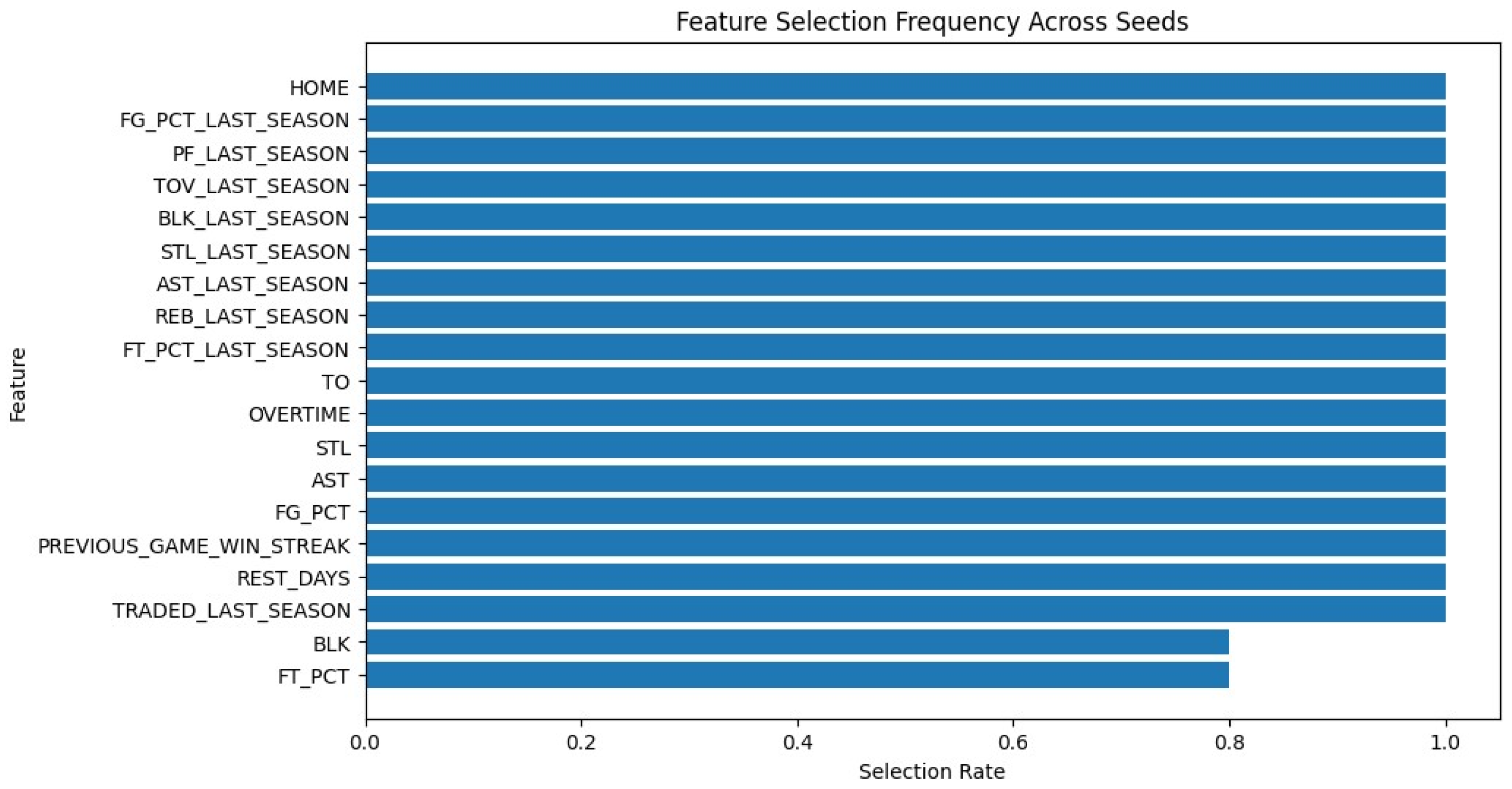

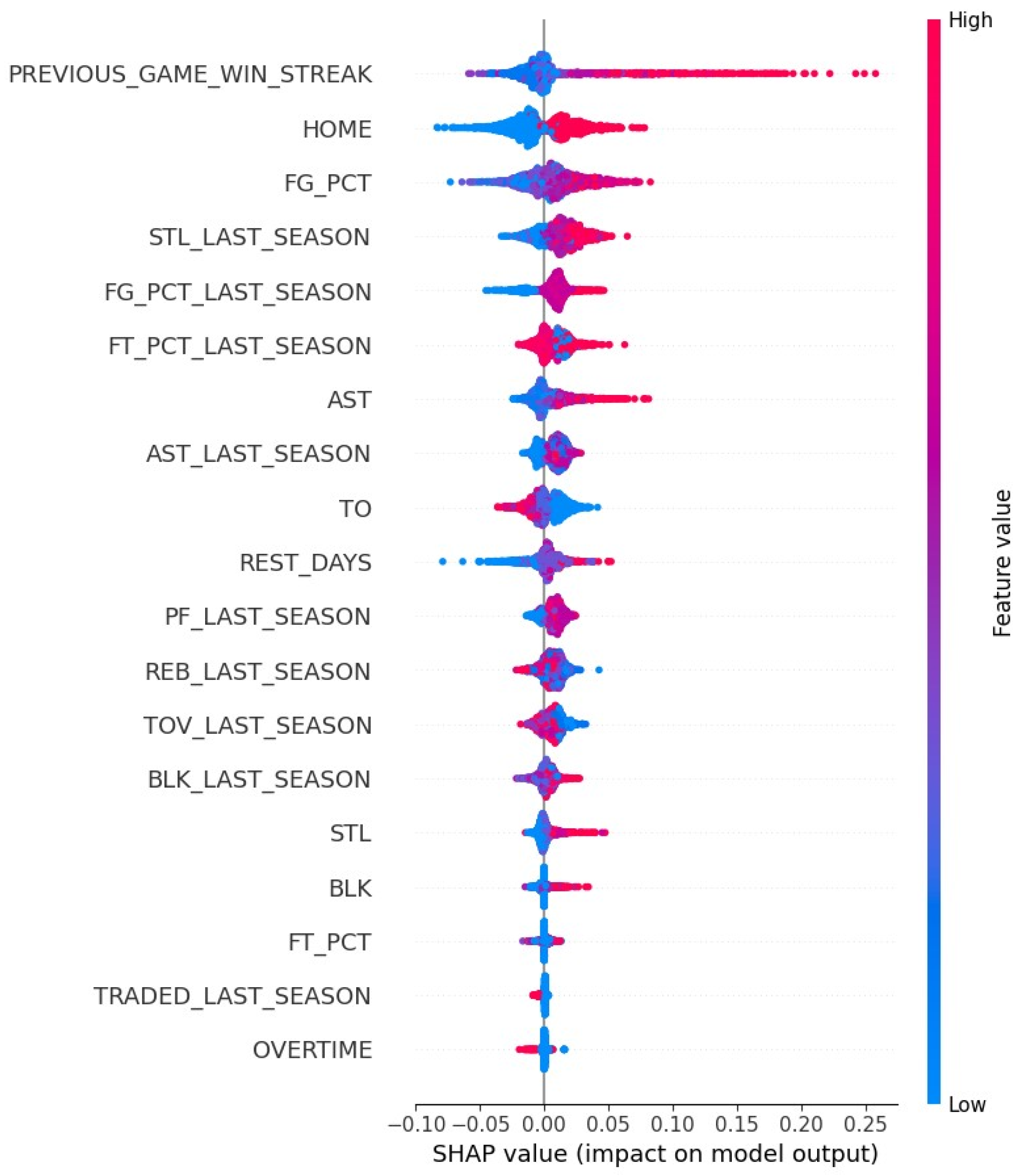

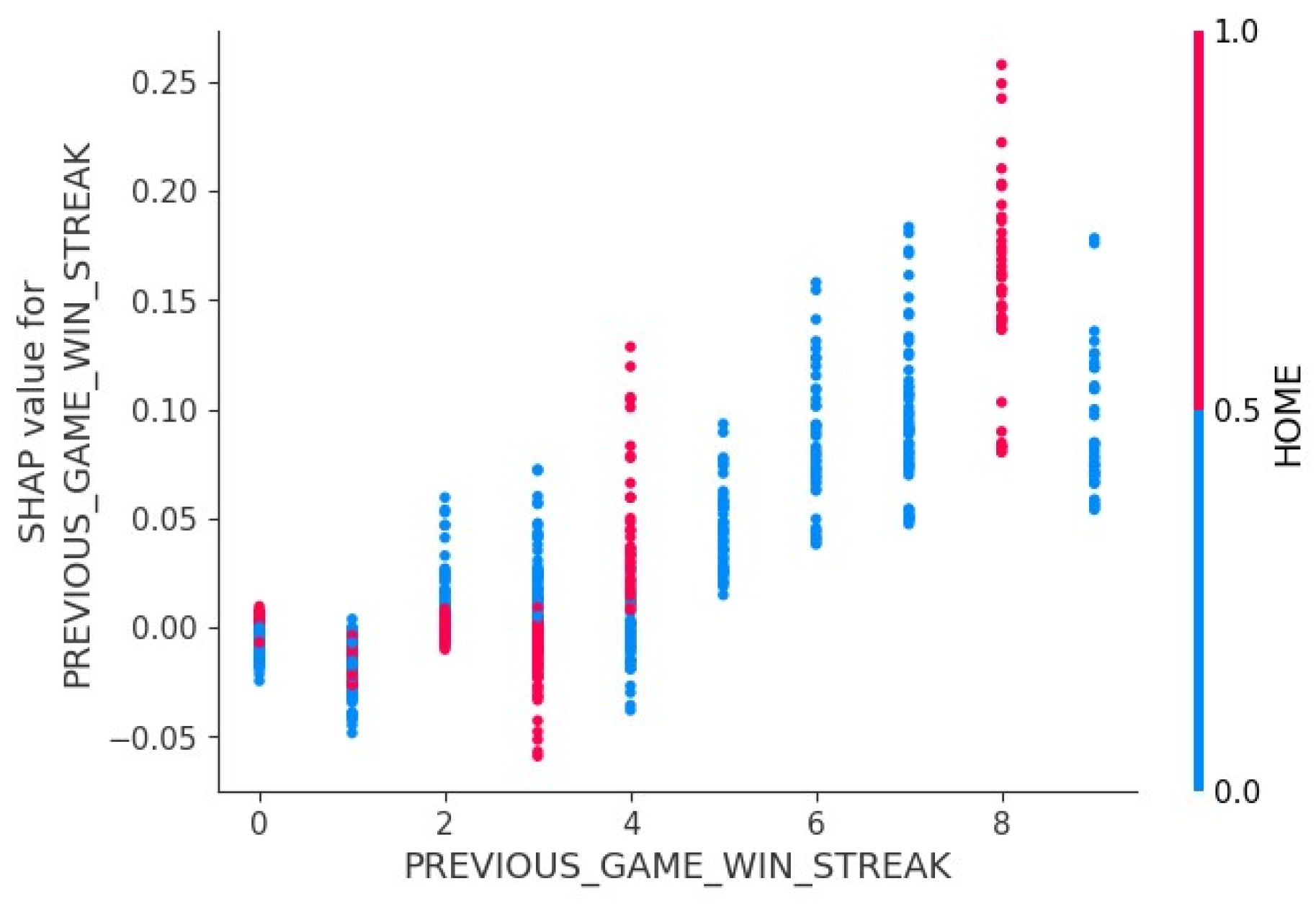

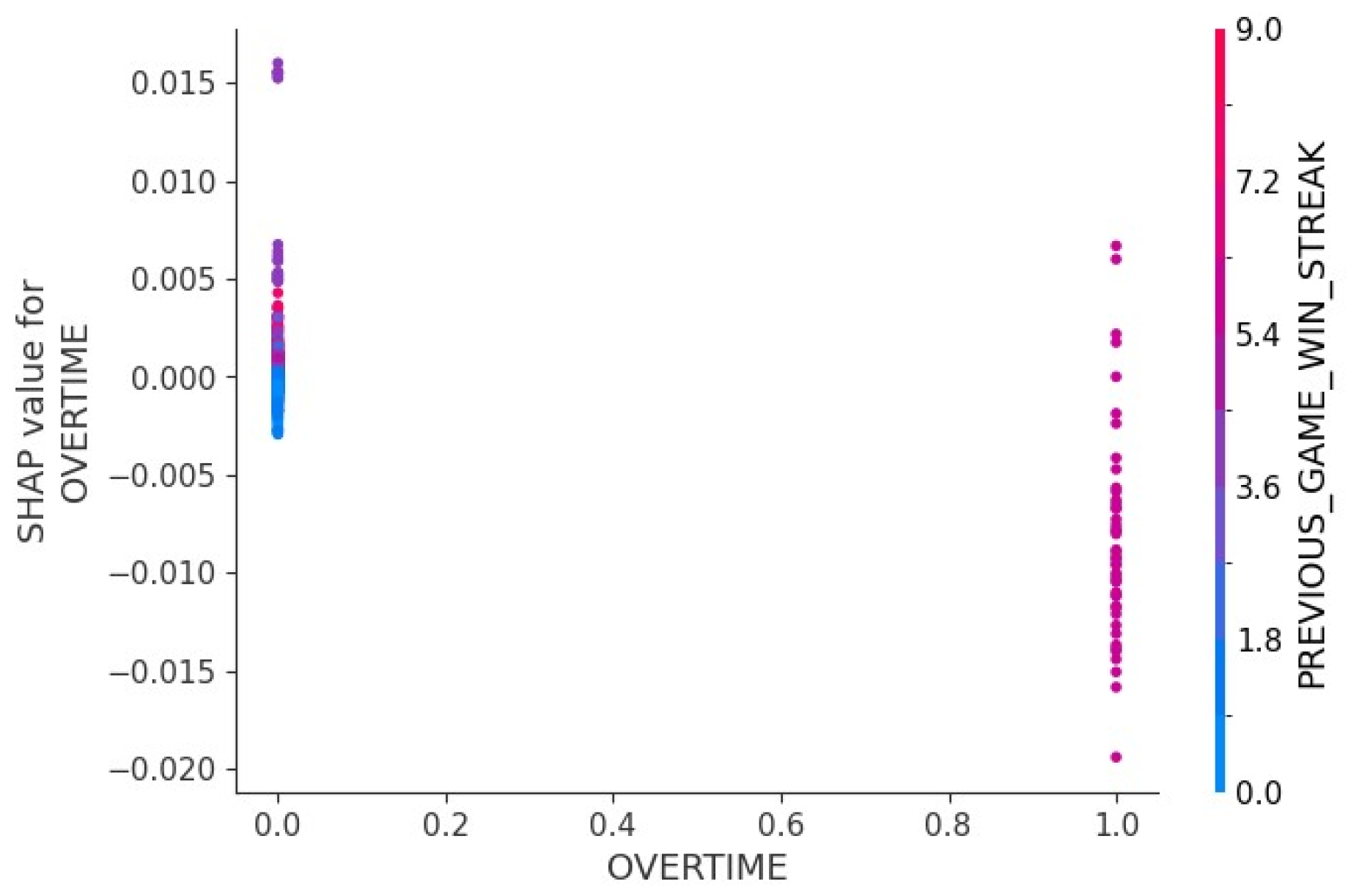

3.4. Feature Importance and Interpretation

4. Results

4.1. Data Exploration

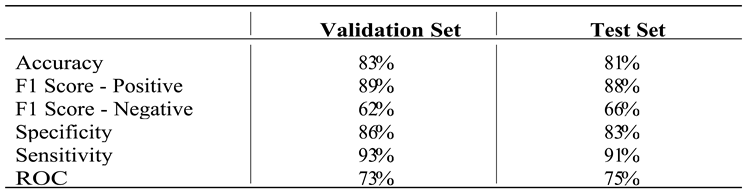

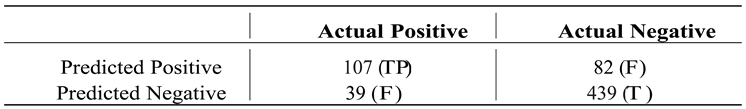

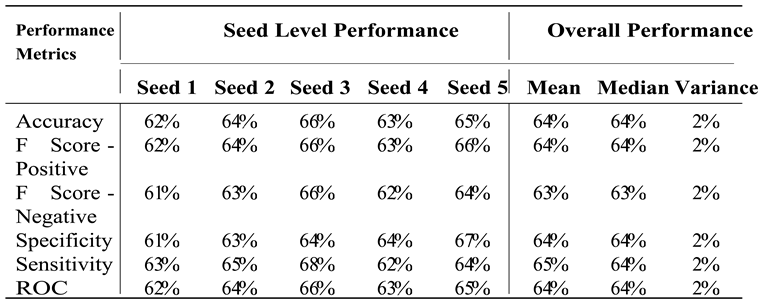

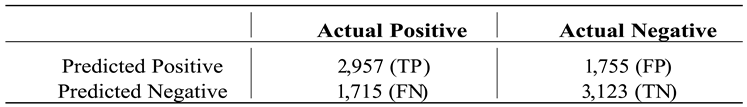

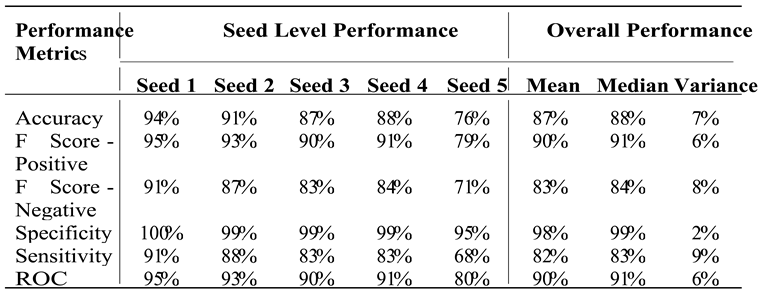

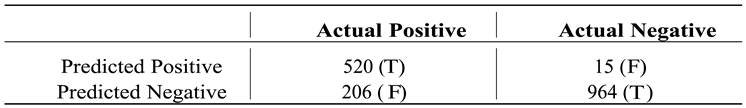

4.2. Model Performance

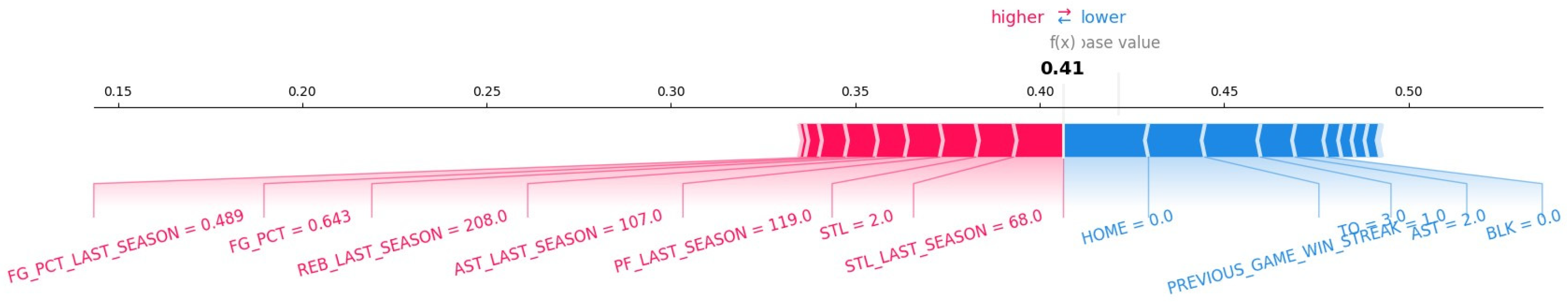

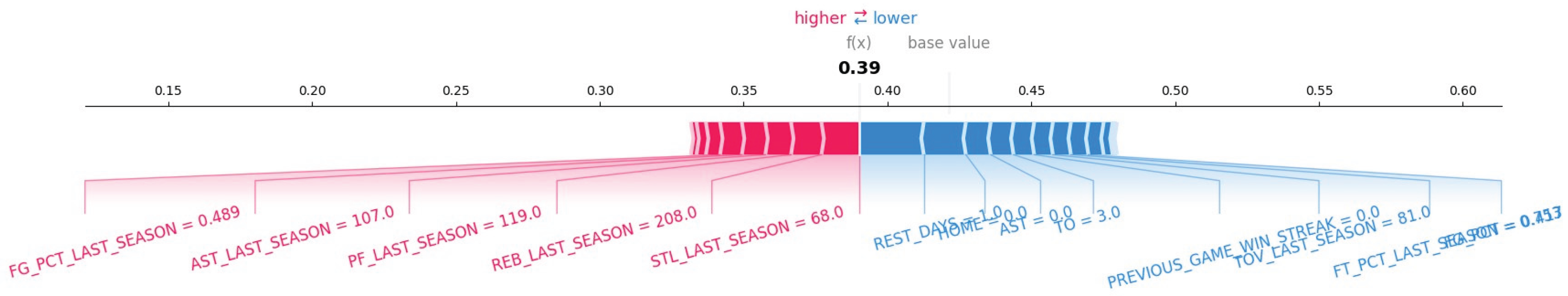

4.3. Model Interpretation

5. Conclusion

6. Discussion

Appendix A

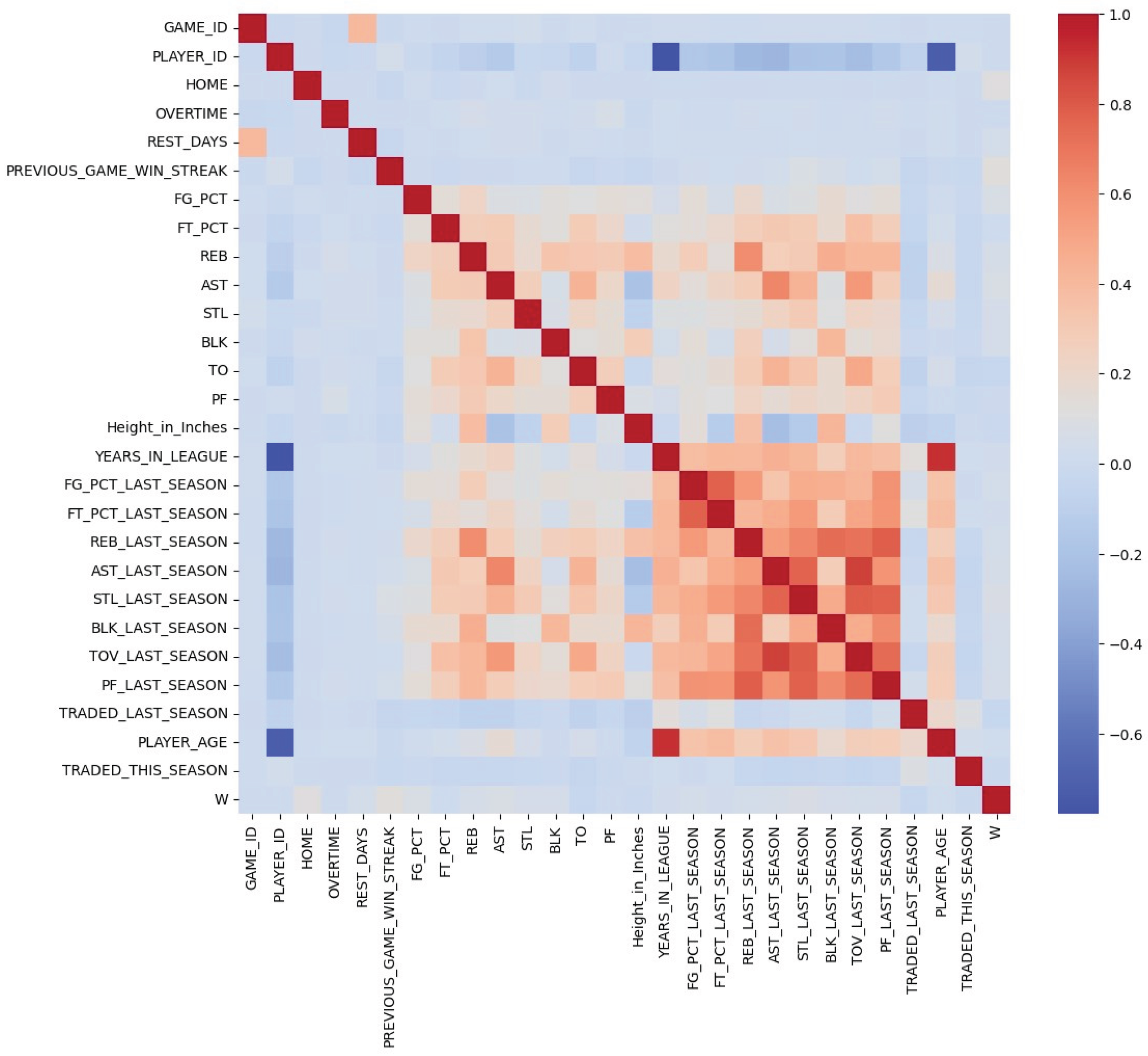

- Game ID – MIdentifier (0 or 1) for each game (i.e. GAME_ID_22400486 represents the game played on January 4th, 2025 with Atlanta Hawks and Los Angeles Lakers)

- Player ID – Identifier (0 or 1) for each player (i.e. PLAYER_ID_1629060 represents the player of LeBron James)

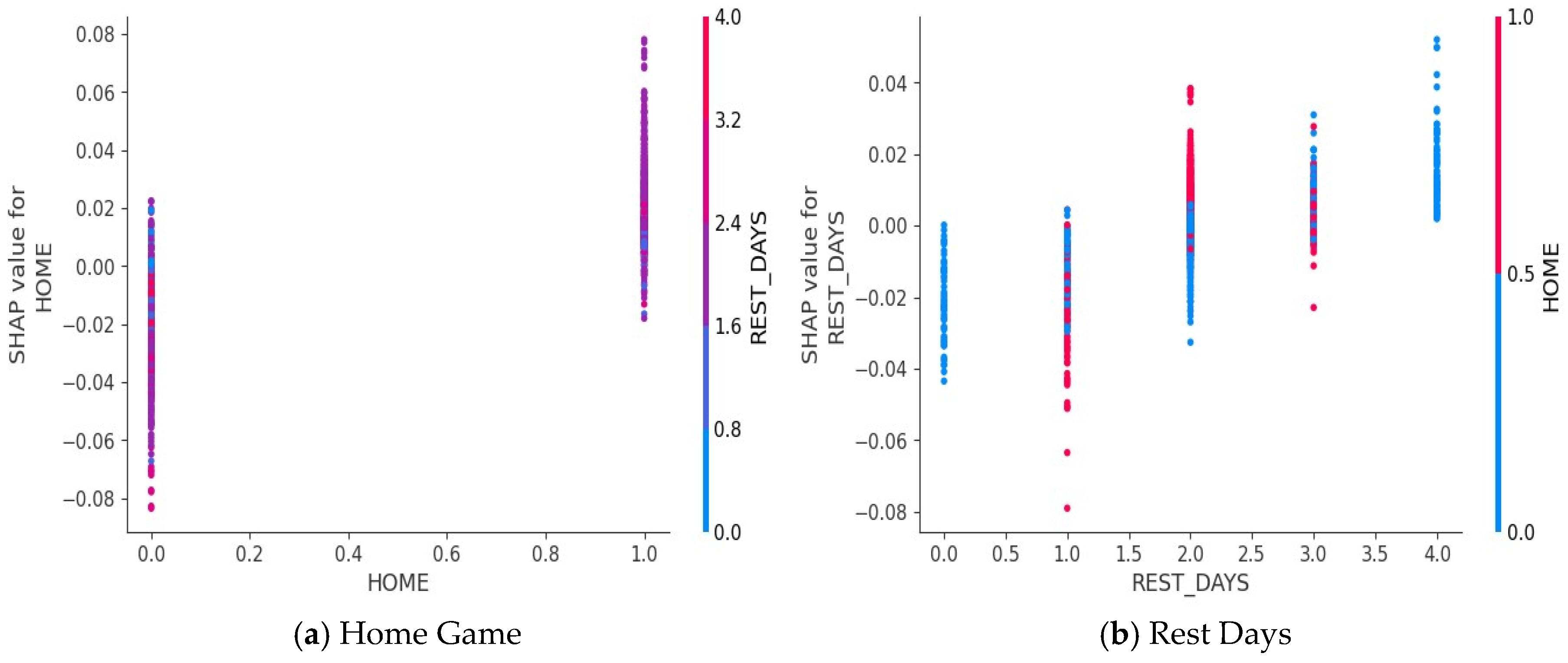

- Home – Identifier (0 or 1) for home game

- Overtime – Identifier (0 or 1) for over time game

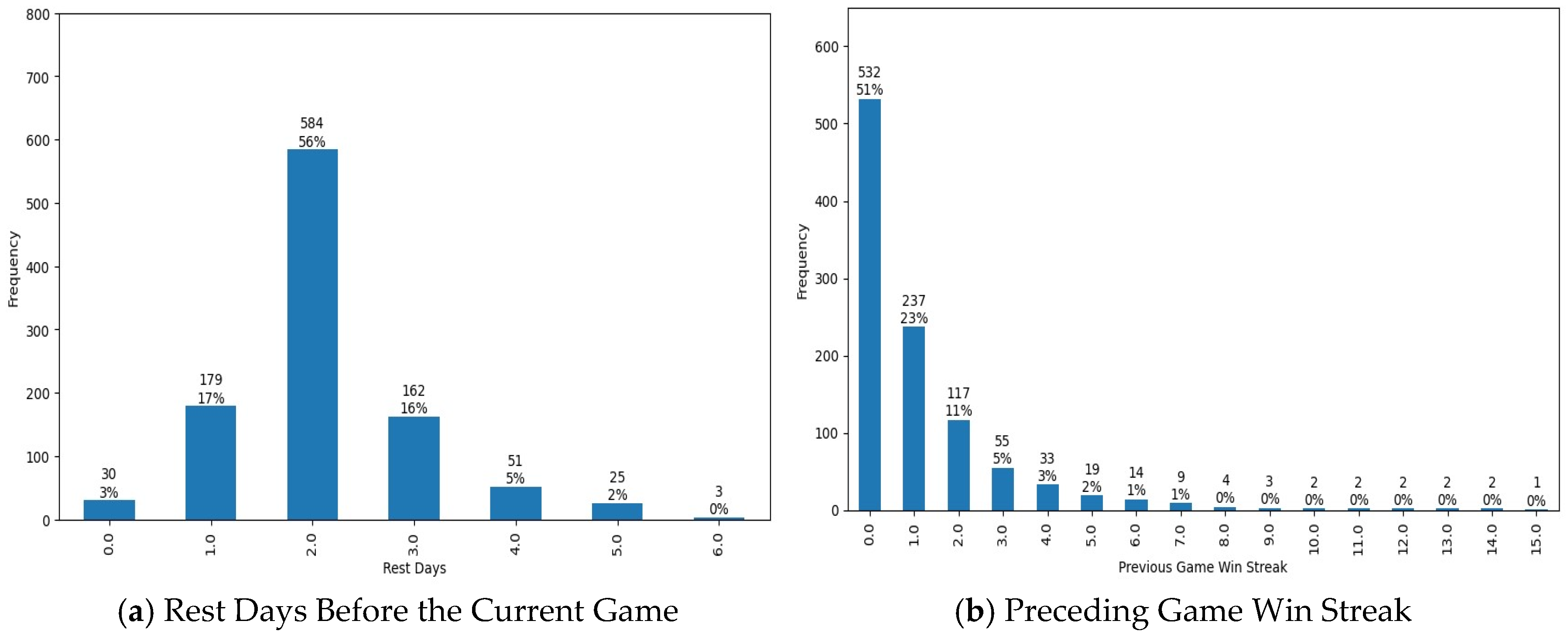

- Rest Days – How many day(s) the team didn’t have a game prior to the current game date

- Previous Game Win Streak – How many game(s) the team consecutively won prior to the current game

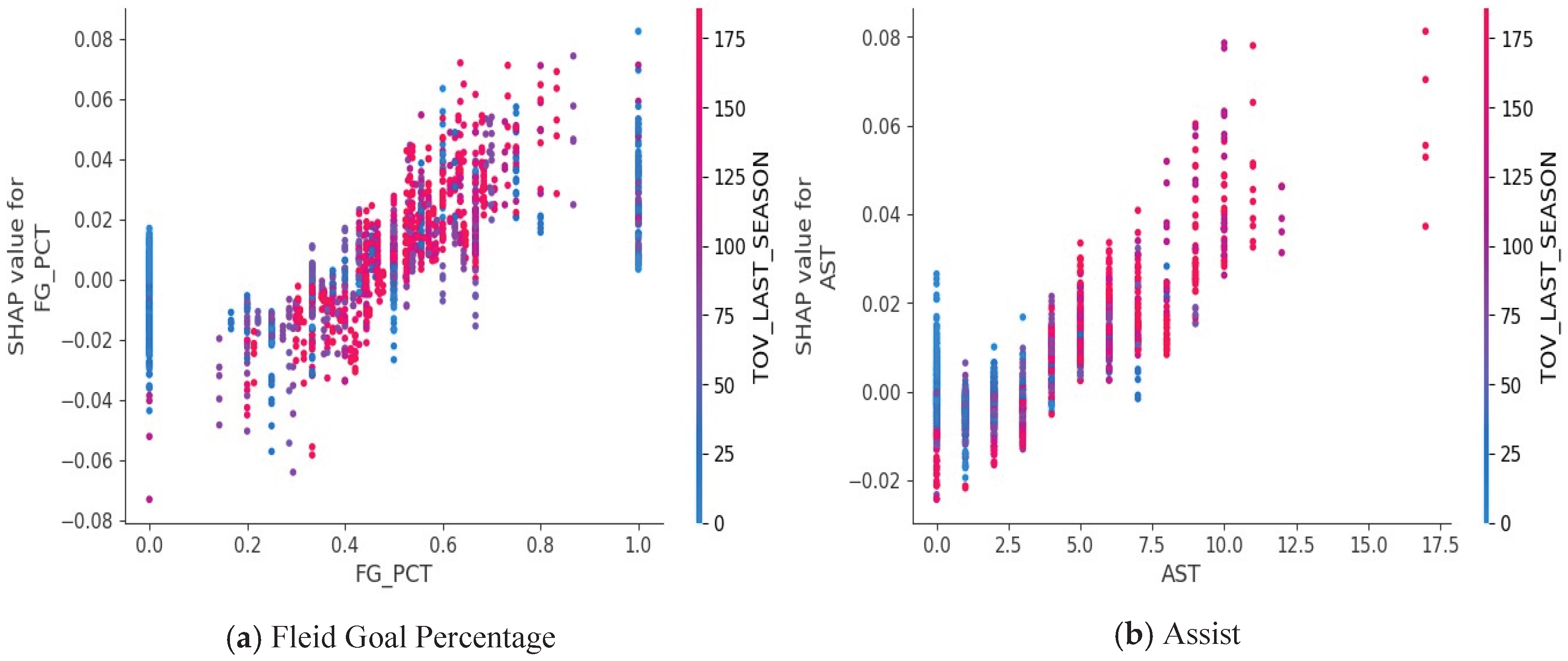

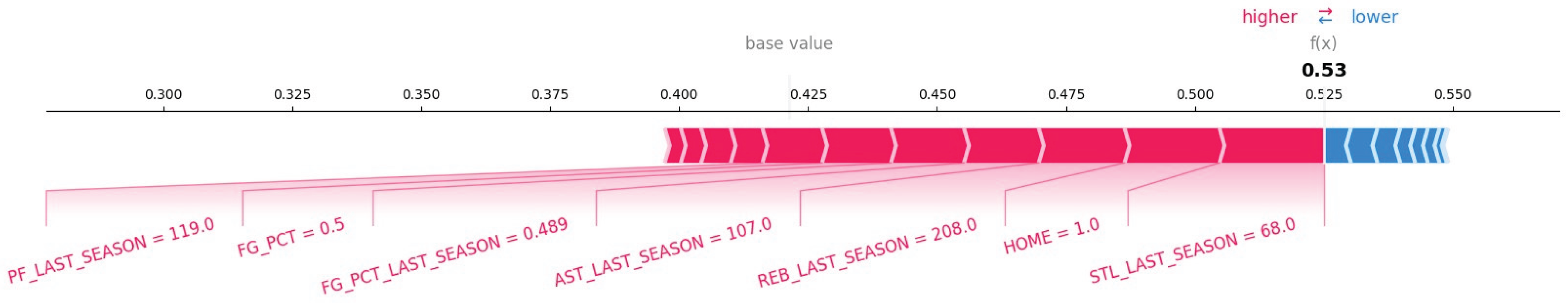

- Field Goal Percentage – How many times the player made the goals compared to the goal attempted in the game (%). Last year overall performance is also available as an variable.

- Free Throw Percentage – How many times the player made the free throw goals compared to the free throw attempted in the game (%). Last year overall performance is also available as an variable.

- Rebound – How many times the player made the rebound for the game. Last year overall performance is also available as an variable.

- Assist – How many times the player made the assist for the game. Last year overall performance is also available as an variable.

- Steal – How many times the player made the steal for the game. Last year overall performance is also available as an variable.

- Turnover – How many times the player made the turnover for the game. Last year overall performance is also available as an variable.

- Personal Foul – How many times the player made the personal foul for the game. Last year overall performance is also available as an variable.

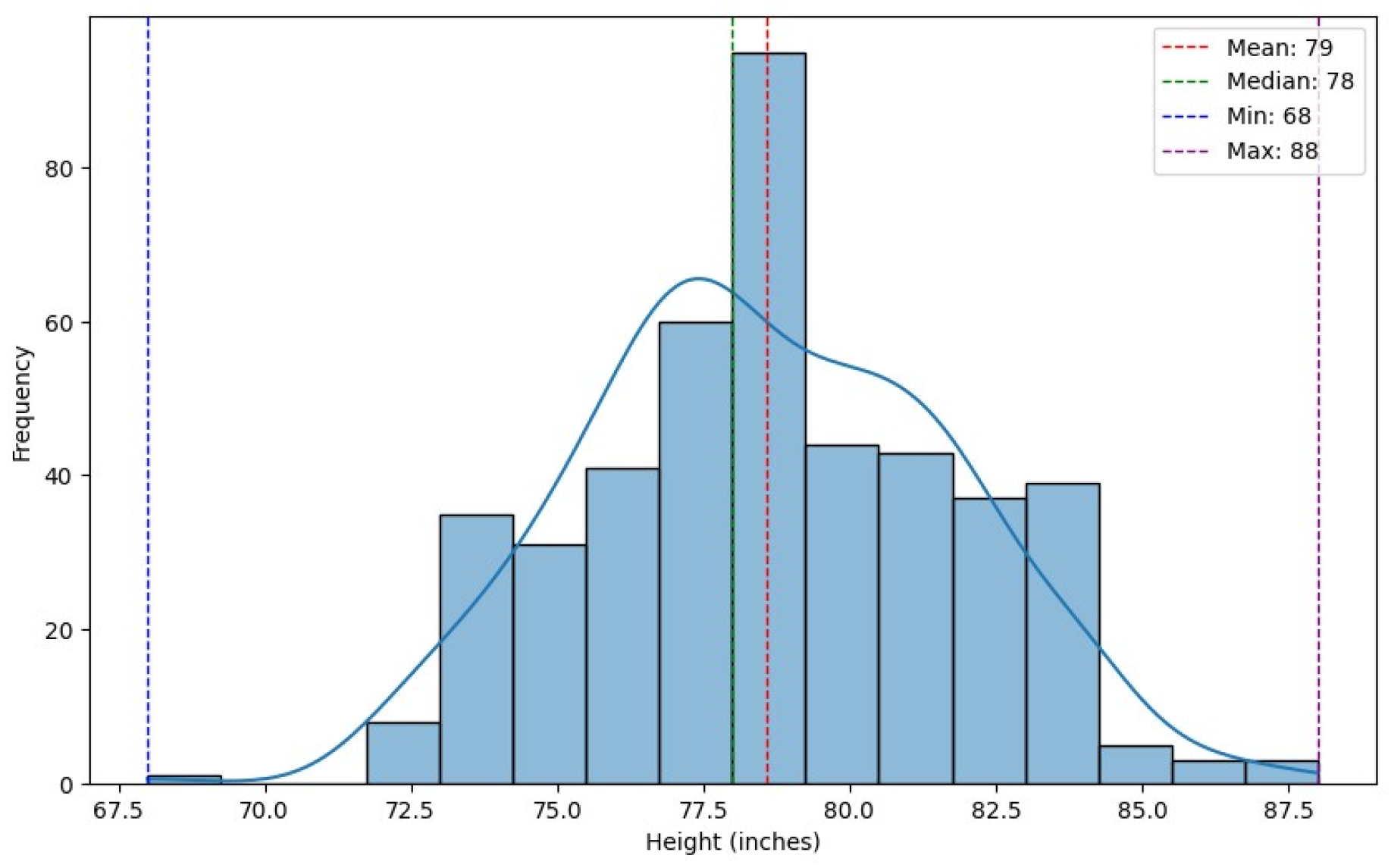

- Height – Player heights in inches

- Player Age – How long the player have been playing in the NBA league

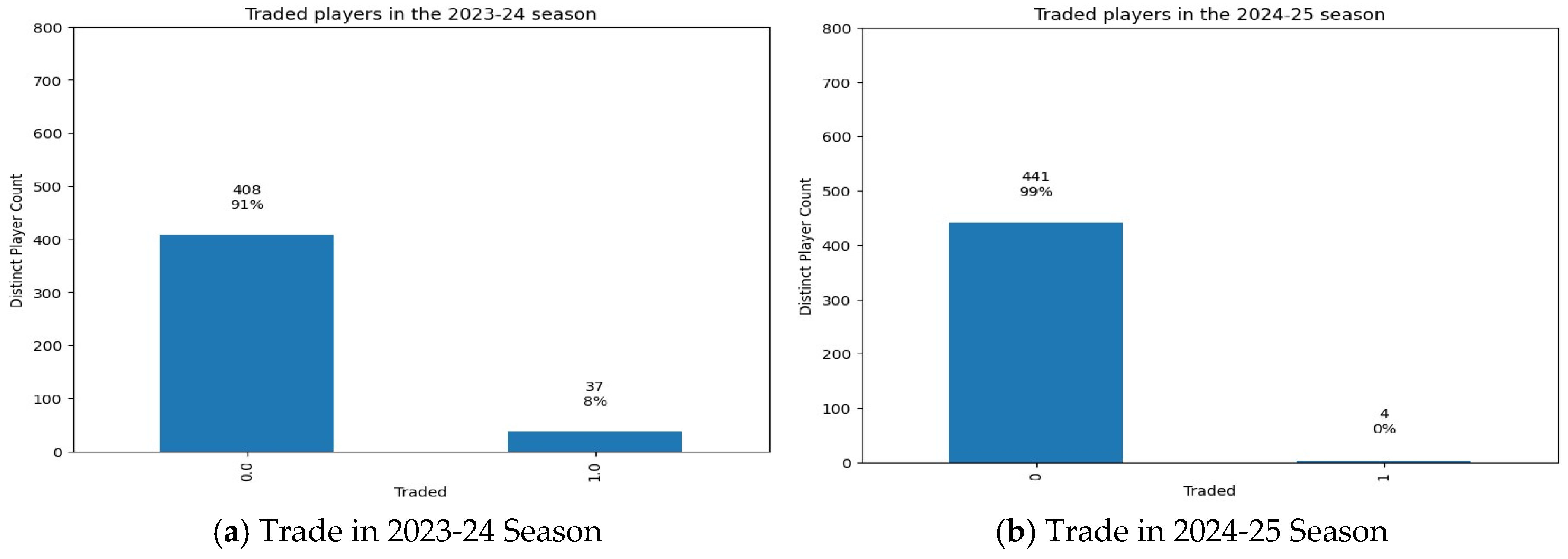

- Traded this season – Indicator (0 or 1) for the player was traded in the season of 2024-25 before January 05, 2025

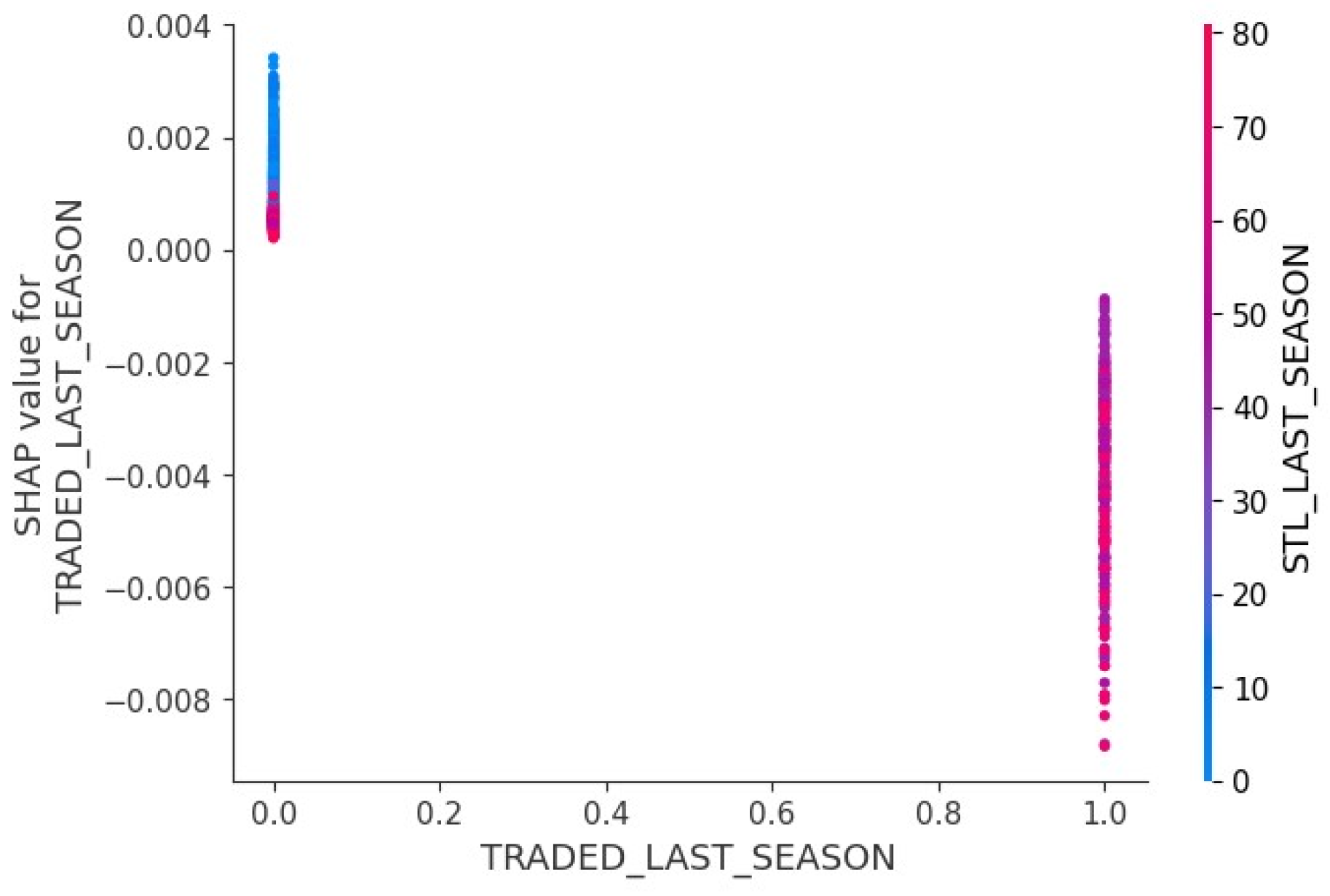

- Traded last season – Indicator (0 or 1) for the player was traded in the season of 2023-24

| Seed | Parallel Trees | Max Depth |

Learning Rate |

Subsample | Feature Sample | |

| Seed 1 | 386 | 98 | 0.09 | 0.83 | 0.64 | |

| Seed 2 | 313 | 45 | 0.09 | 0.86 | 0.88 | |

| Seed 3 | 492 | 98 | 0.08 | 0.74 | 0.57 | |

| Seed 4 | 389 | 41 | 0.09 | 0.91 | 0.46 | |

| Seed 5 | 116 | 39 | 0.09 | 0.45 | 0.31 | |

| Seed | Min Child Weight | Gamma | Alpha | Lambda | ||

| Seed 1 | 6 | 6 × 10−7 | 7 × 10−6 | 0.003 | ||

| Seed 2 | 7 | 6 × 10−8 | 3 × 10−8 | 3 × 10−8 | ||

| Seed 3 | 8 | 3 × 10−5 | 0.003 | 0.002 | ||

| Seed 4 | 10 | 1 × 10−8 | 0.003 | 3 × 10−4 | ||

| Seed 5 | 8 | 1 × 10−8 | 0.001 | 0.060 | ||

References

- Taber, C.B.; Sharma, S.; Raval, M.S.; Senbel, S.; Keefe, A.; Shah, J.; Patterson, E.; Nolan, J.; Artan, N.S.; Kaya, T. A holistic approach to performance prediction in collegiate athletics: player, team, and conference perspectives. Scientific Reports 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Schulte, O. Deep Reinforcement Learning in Ice Hockey for Context-Aware Player Evaluation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 27th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), 2018, pp. [CrossRef]

- Oytun, M.; Tinazci, C.; Acikada, C.; Yavuz, H.U.; Sekeroglu, B. Performance Prediction and Evaluation in Female Handball Players Using Machine Learning Models. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 116321–116335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantzalis, V.C.; Tjortjis, C. Sports Analytics for Football League Table and Player Performance Prediction 2020. pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Patel, B.H.; Camp, C.L.; Forlenza, E.M.; Forsythe, B.; Lavoie-Gagne, O.Z.; Reinholz, A.K.; Pareek, A. Machine Learning for Predicting Lower Extremity Muscle Strain in National Basketball Association Athletes. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine 2022, 10, 232596712211117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, W.; Hong, W.; Zheng, W.; Qi, F.; Peng, L. Integration of machine learning XGBoost and SHAP models for NBA game outcome prediction and quantitative analysis methodology. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0307478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.J.; Jhou, M.J.; Lee, T.S.; Lu, C.J. Hybrid Basketball Game Outcome Prediction Model by Integrating Data Mining Methods for the National Basketball Association. Entropy 2021, 23, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, G.; Zhang, Z.; Kyebambe, M.N.; Kimbugwe, N. Predicting the Outcome of NBA Playoffs Based on the Maximum Entropy Principle. Entropy 2016, 18, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. Optuna: A Next-generation Hyperparameter Optimization Framework. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost parameter tuning documentation, 2020. Version 3.0.0.

- Wang, H.; Wu, Z.; Wang, X.; Bian, L.; Jin, H. HardGBM: A Framework for Accurate and Hardware-Efficient Gradient Boosting Machines. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2023, 42, 2122–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).