Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

16 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

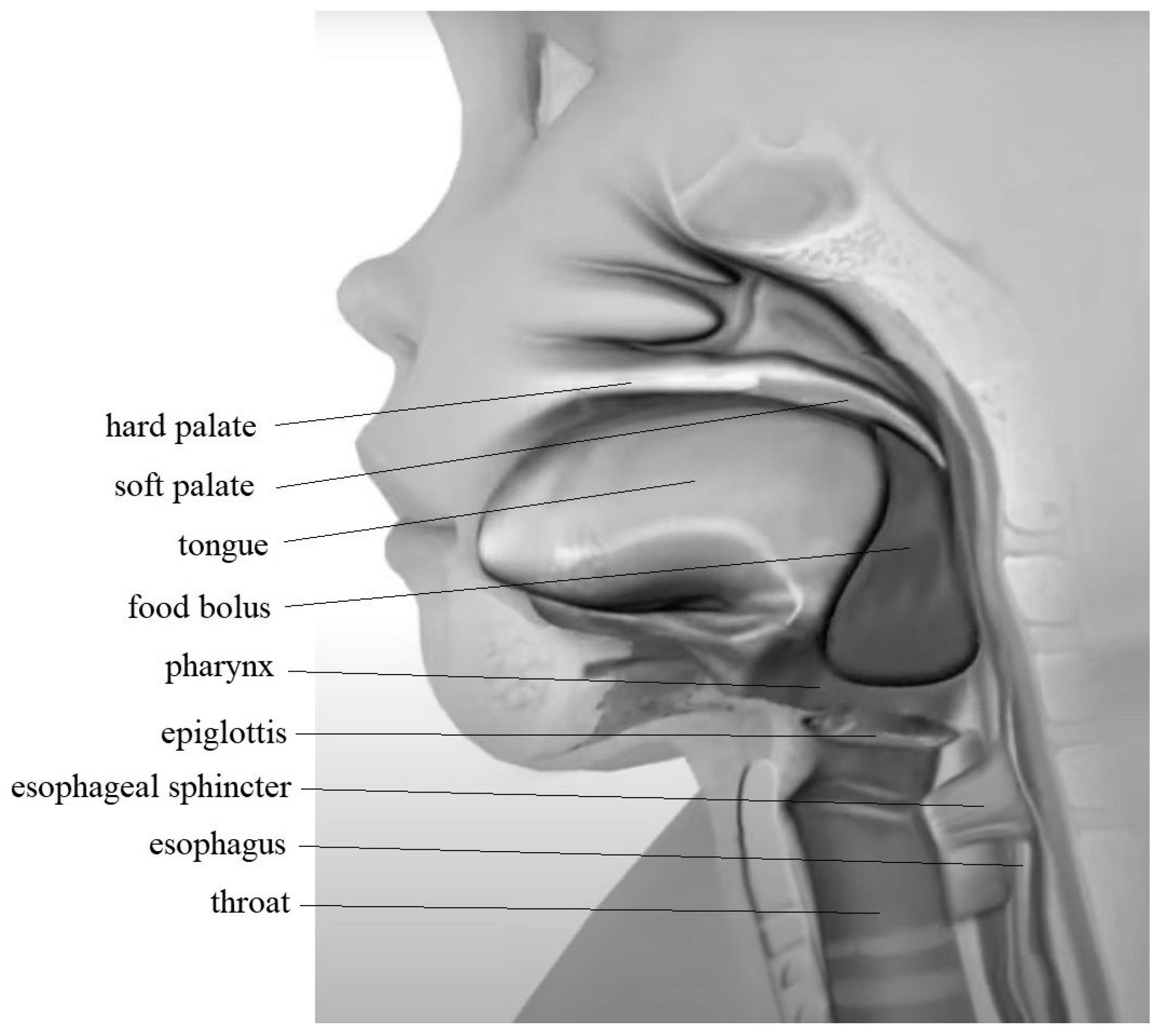

2. The Swallowing Process

3. Symptoms of Dysphagia

4. Causes of Swallowing Disorder

5. Treatment of Dysphagia

6. Electrical Stimulation

7. NMES in Children with Dysphagia

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NMES | Neuro Muscular Electric Stymulation |

| PFD | Pediatric Feeding Disorders |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Prasse, J.E.; Kikano, G.E. Clinical pediatrics an overview of pediatric dysphagia. Clin Pediatr 2009, 48, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodrill, P.; Gosa, M.M. Pediatric Dysphagia: Physiology, Assessment, and Management. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 66, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuchman, D.N. Dysfunctional swallowing in the pediatric patient: Clinical considerations. Dysphagia 1988, 2, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, K.; Palmer, J.B. Anatomy and Physiology of Feeding and Swallowing: Normal and Abnormal. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation Clin. North Am. 2008, 19, 691–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertekin, C.; Aydogdu, I. Neurophysiology of swallowing. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2003, 114, 2226–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.; Jungheim, M.; Kühn, D.; Ptok, M. Electrical Stimulation in Treatment of Pharyngolaryngeal Dysfunctions. Folia Phoniatr. et Logop. 2013, 65, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, N.H.; Othman, A.; A Majid, N.; Harith, S.; Zabidi-Hussin, Z. Parent-report instruments for assessing feeding difficulties in children with neurological impairments: a systematic review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2018, 61, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, C.M.; Choi, S. Diagnosis and Management of Pediatric Dysphagia: A Review. JAMA Pediatrics 2019, 173, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning,Disability and Health: ICF. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2001.

- Barikroo, A. Transcutaneous Electrical Stimulation and Dysphagia Rehabilitation: A Narrative Review. Rehabilitation Res. Pr. 2020, 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan PB, Lambert B, Rose M, et al. Prevalence and severity of feeding and nutritional problems in children with neurological impairment: Oxford Feeding Study. Dev Med Child Neurol 2000;42(10):674–80.

- Manikam, R.; Perman, J.A. Pediatric feeding disorders. J Clin Gastroenterol 2000, 30, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motion, S.; Northstone, K.; Emond, A.; et al. Early feeding problems in children with cerebral palsy: weight and neurodevelopmental outcomes. Dev Med Child Neurol 2002, 44, 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sdravou, K.; Fotoulaki, M.; Emmanouilidou-Fotoulaki, E.; Andreoulakis, E.; Makris, G.; Sotiriadou, F.; Printza, A. Feeding Problems in Typically Developing Young Children, a Population-Based Study. Children 2021, 8, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, N. The prevalence of pediatric voice and swallowing problems in the United States. Laryngoscope 2014, 125, 746–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutor, J.D.; Gosa, M.M. Dysphagia and aspiration in children. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2011, 47, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass NH, Morrell RM. The neurology of swallowing. [in:] M.E. Groher (Ed.), Dysphagia, Diagnosis and Management. Butterworth–Heinemann, Boston, MA: 1992, pp. 1–29.

- Duffy, K.L. Dysphagia in Children. J Pediatr Health Care 2018, 32, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoli, S.M.; Wilson, B.L.; Swanson, C. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation improves feeding and aspiration status in medically complex children undergoing feeding therapy. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 127, 109646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Propp, R.; Gill, P.J.; Marcus, S.; Ren, L.; Cohen, E.; Friedman, J.; Mahant, S. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation for children with dysphagia: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e055124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiaanse, M.E.; Mabe, B.; Russell, G.; Simeone, T.L.; Fortunato, J.; Rubin, B. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation is no more effective than usual care for the treatment of primary dysphagia in children. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2010, 46, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phalen, J.A. Managing feeding problems and feeding disorders. Pediatrics Rev 2013, 34, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Printza, A.; Sdravou, K.; Triaridis, S. Dysphagia Management in Children: Implementation and Perspectives of Flexible Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing (FEES). Children 2022, 9, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logemann, JA. Evaluation and Treatment of Swallowing Disorders. Pro-Ed, Inc., Austin, TX: 1998.

- Santos JK, Cortes Gama AC, Alves Silvério KC, et al. The use of electrical stimulation in speech therapy clinical: An integrative literature review. Braz J Speech Therapy 2015;20(3):201–9.

- Alamer, A.; Melese, H.; Nigussie, F. Effectiveness of Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation on Post-Stroke Dysphagia: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin. Interv. Aging 2020, ume 15, 1521–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diéguez-Pérez, I.; Leirós-Rodríguez, R. Effectiveness of Different Application Parameters of Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation for the Treatment of Dysphagia after a Stroke: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-W.; Chang, K.-H.; Chen, H.-C.; Liang, W.-M.; Wang, Y.-H.; Lin, Y.-N. The effects of surface neuromuscular electrical stimulation on post-stroke dysphagia: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabilitation 2015, 30, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, A.D.; Goodwin, N.; Cash, E.; Bhatt, G.; Silverman, C.L.; Spanos, W.J.; Bumpous, J.M.; Potts, K.; Redman, R.; Allison, W.A.; et al. Impact of transcutaneous neuromuscular electrical stimulation on dysphagia in patients with head and neck cancer treated with definitive chemoradiation. Head Neck 2014, 37, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Benfer, K.; A Weir, K.; Boyd, R.N. Clinimetrics of measures of oropharyngeal dysphagia for preschool children with cerebral palsy and neurodevelopmental disabilities: a systematic review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2012, 54, 784–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terré, R.; Mearin, F. A randomized controlled study of neuromuscular electrical stimulation in oropharyngeal dysphagia secondary to acquired brain injury. Eur. J. Neurol. 2015, 22, 687–e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonelli, M.; Ruoppolo, G.; Iosa, M.; Morone, G.; Fusco, A.; Grasso, M.G.; Gallo, A.; Paolucci, S. A stimulus for eating. The use of neuromuscular transcutaneous electrical stimulation in patients affected by severe dysphagia after subacute stroke: A pilot randomized controlled trial. NeuroRehabilitation 2019, 44, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushner, D.S.; Peters, K.; Eroglu, S.T.; Perless-Carroll, M.; Johnson-Greene, D. Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation Efficacy in Acute Stroke Feeding Tube–Dependent Dysphagia During Inpatient Rehabilitation. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 2013, 92, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, B.H.; Park, Y.H. Analysis of Dysphagia Patterns Using a Modified Barium Swallowing Test Following Treatment of Head and Neck Cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2015, 56, 1221–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarihci Cakmak E, Sen EI, Doruk C, et al. The Effects of Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation on Swallowing Functions in Post-stroke Dysphagia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Dysphagia 2023;38(3):874-85.

- Sun, Y.; Chen, X.; Qiao, J.; Song, G.B.; Xu, Y.B.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, D.; Gao, W.; Li, Y.; Xu, C. Effects of Transcutaneous Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation on Swallowing Disorders A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 2020, 99, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwemmle C, Arens C. Feeding, eating, and swallowing disorders in infants and children: An overview. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngol 2018;112:151-8.

- Florie, M.G.M.H.; Pilz, W.; Dijkman, R.H.; Kremer, B.; Wiersma, A.; Winkens, B.; Baijens, L.W.J. The Effect of Cranial Nerve Stimulation on Swallowing: A Systematic Review. Dysphagia 2020, 36, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilinc, D.D.; Mansiz, D. Myofunctional orofacial examination tests: a literature review. BMC Oral Heal. 2023, 23, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennessy M, Goldenberg D. Surgical anatomy and physiology of swallowing. Operative Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016;27(2):60-6.

- Costa MMB. Neural control of swallowing. Arq Gastroenterol 2018;55:61-75.

- Feher, J. Mouth and Esophagus. In: Feher J, editor, Quantitative Human Physiology (2nd ed), Academic Press, Cambridge, MA, 2017, pp. 771-84.

- Goday PS, Huh SY, Silverman A, et al. Pediatric Feeding Disorder: Consensus Definition and Conceptual Framework. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2019;68(1):124-9.

- Mari, A.; Sweis, R. Assessment and management of dysphagia and achalasia. Clin. Med. 2021, 21, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo G, Strisciugli C. Dysphagia: A practical approach. Glob Pediatr 2024;7:100136.

- Weir, K.; McMahon, S.; Barry, L.; Masters, I.B.; Chang, A.B. Clinical signs and symptoms of oropharyngeal aspiration and dysphagia in children. Eur. Respir. J. 2008, 33, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnicka, E.; Kowalska, K.; Borkowska, J.; Socha, P. Improvement of swallowing function due to neuromuscular electrical stimulation in children with primary dysphagia. Pediatr. Polska 2024, 99, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnicka, E. Therapy of dysphagia using electrostimulation: experience in pediatric population. Gastroenterol Klin 2019;15(2):85–92.

- Hewetson, R.; Singh, S. The Lived Experience of Mothers of Children with Chronic Feeding and/or Swallowing Difficulties. Dysphagia 2009, 24, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, S.S.; Demir, N.; Yalcın, S.; Karaduman, A.; Karnak, I.; Tanyel, F.C.; Soyer, T. Effect of Swallowing Rehabilitation Protocol on Swallowing Function in Patients with Esophageal Atresia and/or Tracheoesophageal Fistula. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2017, 27, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attrill, S.; White, S.; Murray, J.; Hammond, S.; Doeltgen, S. Impact of oropharyngeal dysphagia on healthcare cost and length of stay in hospital: a systematic review. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziewas, R.; Beck, A.M.; Clave, P.; Hamdy, S.; Heppner, H.J.; Langmore, S.E.; Leischker, A.; Martino, R.; Pluschinski, P.; Roesler, A.; et al. Recognizing the Importance of Dysphagia: Stumbling Blocks and Stepping Stones in the Twenty-First Century. Dysphagia 2016, 32, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todorović, J.; Zelić, M.; Jerkić, L. Eating and swallowing disorders in children with cleft lip and/or palate. Acta Fac. Medicae Naissensis 2022, 39, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy M, Perman J. Pediatric Feeding Disorders. J Clin Gastroenterol 2000;30(1):34-46.

- Lanzoni, G.; Sembenini, C.; Gastaldo, S.; Leonardi, L.; Bentivoglio, V.P.; Faggian, G.; Bosa, L.; Gaio, P.; Cananzi, M. Esophageal Dysphagia in Children: State of the Art and Proposal for a Symptom-Based Diagnostic Approach. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 885308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Zaher, E.; Patel, P.; Atia, G.; Sigdel, S. Distal Esophageal Spasm: An Updated Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e41504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirinawasatien, A.; Sakulthongthawin, P. Manometrically jackhammer esophagus with fluoroscopically/endoscopically distal esophageal spasm: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021, 21, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D.J.; Nashwan, A.J.; Al-Ansari, A.N. Congenital and Iatrogenic Esophageal Diverticula in Infants and Children: A Case Series of Four Patients. Cureus 2024, 16, e68806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, E.; Philpott, H. Pathophysiology of Dysphagia in Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Causes, Consequences, and Management. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2022, 67, 1101–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Tan, Y.; Li, C.; Lv, L.; Zhu, H.; Liang, C.; Li, R.; Liu, D. Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy for Pediatric Achalasia: A Retrospective Analysis of 21 Cases With a Minimum Follow-Up of 5 Years. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 845103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, P.O.; Valero-Arredondo, I.; Torcuato-Rubio, E.; Herrador-López, M.; Martín-Masot, R.; Navas-López, V.M. Nutritional Issues in Children with Dysphagia. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros-Pomar, M.D.; Cherubini, A.; Keller, H.; Lam, P.; Rolland, Y.; Simmons, S.F. Texture-Modified Diet for Improving the Management of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Nursing Home Residents: An Expert Review. J. Nutr. Heal. Aging 2020, 24, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, C.L. History of the Use and Impact of Compensatory Strategies in Management of Swallowing Disorders. Dysphagia 2017, 32, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipasquale, V.; Cucinotta, U.; Alibrandi, A.; Laganà, F.; Ramistella, V.; Romano, C. Early Tube Feeding Improves Nutritional Outcomes in Children with Neurological Disabilities: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller S, Peters K, Ptok M., Review of the effectiveness of neuromuscular electrical stimulation in the treatment of dysphagia - an update. J Clin Rehabil 2022;36(5):455-66.

- Frost, J.; Robinson, H.F.; Hibberd, J. A comparison of neuromuscular electrical stimulation and traditional therapy, versus traditional therapy in patients with longstanding dysphagia. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 26, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.-H.; Jang, J.; Jang, E.G.; Park, Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, B.R.; Park, D.; Park, S.; Hwang, H.; Kim, N.H.; et al. Clinical effectiveness of the sequential 4-channel NMES compared with that of the conventional 2-channel NMES for the treatment of dysphagia in a prospective double-blind randomized controlled study. J. Neuroeng. Rehabilitation 2021, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechkham, P. Principles of electrical stimulation, Top. Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 1999;5:1–5.

- Ryu, J.S.; Kang, J.Y.; Park, J.Y.; Nam, S.Y.; Choi, S.H.; Roh, J.L.; Kim, S.Y.; Choi, K.H. The effect of electrical stimulation therapy on dysphagia following treatment for head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009, 45, 665–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengisu, S.; Demir, N.; Krespi, Y. Effectiveness of Conventional Dysphagia Therapy (CDT), Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation (NMES), and Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) in Acute Post-Stroke Dysphagia: A Comparative Evaluation. Dysphagia 2023, 39, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães BTL, Lepri JR. Możliwości zastosowania elektrostymulacji w motoryce twarzowo-ustnej. J Orofacial Therapy 2024;18(1):45–53.

- Clark, H.; Lazarus, C.; Arvedson, J.; Schooling, T.; Frymark, T. Evidence-Based Systematic Review: Effects of Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation on Swallowing and Neural Activation. Am. J. Speech-Language Pathol. 2009, 18, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eimoto, K.; Nagai, K.; Nakao, Y.; Uchiyama, Y.; Domen, K. Swallowing Rehabilitation With Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation for Sarcopenic Dysphagia: A Case Report. Cureus 2024, 16, e59256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.J.; Park, J.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, M.Y. Effects of Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation on Swallowing Functions in Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial. Hong Kong J. Occup. Ther. 2015, 25, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnaby-Mann, G.D.; Crary, M.A. Examining the Evidence on Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation for Swallowing. Arch. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2007, 133, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.-L.; Liu, T.-Y.; Huang, Y.-C.; Leong, C.-P.; Lin, W.-C.; Pong, Y.-P. Functional Outcome in Acute Stroke Patients with Oropharyngeal Dysphagia after Swallowing Therapy. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2014, 23, 2547–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permsirivanich, W.; Tipchatyotin, S.; Wongchai, M.; Leelamanit, V.; Setthawatcharawanich, S.; Sathirapanya, P.; Phabphal, K.; Juntawises, U.; Boonmeeprakob, A. Comparing the effects of rehabilitation swallowing therapy vs. neuromuscular electrical stimulation therapy among stroke patients with persistent pharyngeal dysphagia: a randomized controlled study. J Med Ass Thailand 2009, 92, 259–65. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenfeld, L.; Hahn, Y.; LePage, A.; Leonard, R.; Belafsky, P.C. Transcutaneous electrical stimulation versus traditional dysphagia therapy: A nonconcurrent cohort study. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgy 2006, 135, 754–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pownall, S.; Enderby, P.; Sproson, L. Electrical stimulation for the treatment of dysphagia. Electroceuts 2017:137–56.

- Lv J, Zhu M, Zhang Y. Effects of different intensity neuromuscular electrical stimulation on dysphagia in children with cerebral palsy. Chin J Rehabil Med 2019;34:159–64.

- El-Sheikh A, El-Tohamy A, Abd El-Aziz B. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation therapy on controlling dysphagia in spastic cerebral palsy: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Polish J Physiotherap 2020;20:194–8.

- Ma SR, Choi JB. Effect of electrical stimulation on aspiration in children with cerebral palsy and dysphagia. J Phys Ther Sci 2019;31:93–4.

- Gao, S.; Gao, D.; Su, N.; Zeng, C.; Zhou, Q.; Lin, J. [Effect of acupuncture at proximal and distal acupoints combined with neuromuscular electrical stimulation on children with cerebral palsy salivation]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2018, 38, 825–30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rice, K. Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation in the Early Intervention Population: A Series of Five Case Studies. Internet J. Allied Heal. Sci. Pr. 2012, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, S.; Friedman, J.N.; Lacombe-Duncan, A.; Mahant, S. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation for treatment of dysphagia in infants and young children with neurological impairment: a prospective pilot study. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2019, 3, e000382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).