1. Introduction

Gastrostomy tube (GT) placement for enteral nutrition (EN) is one of the most common surgeries in pediatrics [

1]. It is set to deliver vital macro and micronutrients to patients who are unable to tolerate their nutritional requirements through oral intake [

2,

3]. The need for GTs placement in children varies broadly; from failure to thrive to high-calorie expenditure diseases, dysphagia and swallowing disorders (including aspiration pneumonitis [

4]), craniofacial and digestive tube malformations, malabsorptive diseases, among others [

1]. Undernourishment is also a major indication for enteral nutrition. Malnutrition, on the other hand, leads to alteration of bodily functions, including muscle weakness, immunocompromise, and general worsening of health status, including the rise of mortality rates [

5], thus this procedure becomes vital in the improvement of health-related outcomes, secure survival and improve quality of life.

It is due to new disease approaches, clinical technologies, and higher survival rates of infants that GT indication has risen exponentially in the last decade. A study by Anoosh et al, refers to the fact that gastrostomy use has nearly doubled in the last ten years, and the prevalence of patients who continue to depend on GT for nutrition over one-year or more has increased [

6] as consequence.

It is important to mention that attitudes regarding GT placement vary broadly in different areas of the world [

4]. Enteral nutrition indication in developing countries focuses on patients’ survival and does not take into consideration the burden on caregivers nor the costs for families and health system. Hence, several concerns arise regarding gastrostomy placements [

4]. Firstly, patients who are in the last stages of their primary disease, with an anticipated short life span, are more likely to pass away due to other reasons, e.g., an EN tube infection, instead of their primary disease. Secondly, racial disparities have been found in a recent study by Khrais et al, where Hispanic patients show higher rates of morbidity, mortality, and longer lengths of stay, after GT procedure, due to health resources [

5]. Moreover, there is lack of access to over all rehabilitation (including dysphagia management) in low and middle-income countries [

7], leading to chronic enteral nutrition for these patients. Finally, it is important to emphasize that 85% of disabled people of the world live in the aforementioned countries [

7], which leads to worse health outcomes, including low weight and poor nutritional status.

This report took place in Arica, the northernmost and one of the most resources-limited cities of Chile, characterized by its desertic weather, high levels of migration from Peru, and high levels of lead and arsenic contamination [

8].

This study aimed to analyze the impact of chronic use of gastrostomy tubes in pediatric patients with cerebral palsy one year after its placement, through the assessment of anthropometric variables in a hospital of a developing country.

2. Materials and Methods

This study had a cohort-type intervention, cross-sectional measurement, and qualitative-quantitative analytical variables. It was carried out in Arica - Chile, from September to December 2023, in the Pediatrics Unit of the Regional Hospital Dr. Juan Noé Crevani.

After the approval to access the database of this population, biosocial (age, sex), and anthropometric variables were obtained. Nutritional evaluation was assessed by trained Dietitian through weight (in kilograms), length (in centimeters), body mass index (through the formula weight/height2) and percentile deviations, as the international norm dictates for nutritional assessment in children with cerebral palsy (Life Expectancy Project).

Data of the entire population of patients who were users of enteral nutrition and were attended at the Hospital Regional Dr. Juan Noé Crevani (n=24). Inclusion criteria were patients under 18 years old, CP diagnosis, had a feeding tube and were attended at this hospital for at least one year.

This study was presented and approved by the Healthcare Ethics Committee (CEA) and Director of the Regional Hospital Dr. Juan Noé Crevani. CEA Code: Memo 695, August 2023.

The Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) determined significant differences in the nutritional behavior of children with cerebral palsy, prior to gastrostomy tube placement and one year after its placement. Subsequently, Paired T-Test was applied to analyze the same set of variables that were measured under different conditions (pre-GTP and after) in the same set of patients.

A normality test was used to determine results which were expressed on average and standard deviations.

Data was analyzed with statistical software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 21) and Software for Statistics and Data Science (STATA 12).

3. Results

It was globally observed that all anthropometric variables improved after one year of gastrostomy tube placement. On average, this sample showed an increase of 3.89 kilos (p<0.000), 8.87 cm. (p<0.000), and 1.72 kg/mt2 (p<0.001).

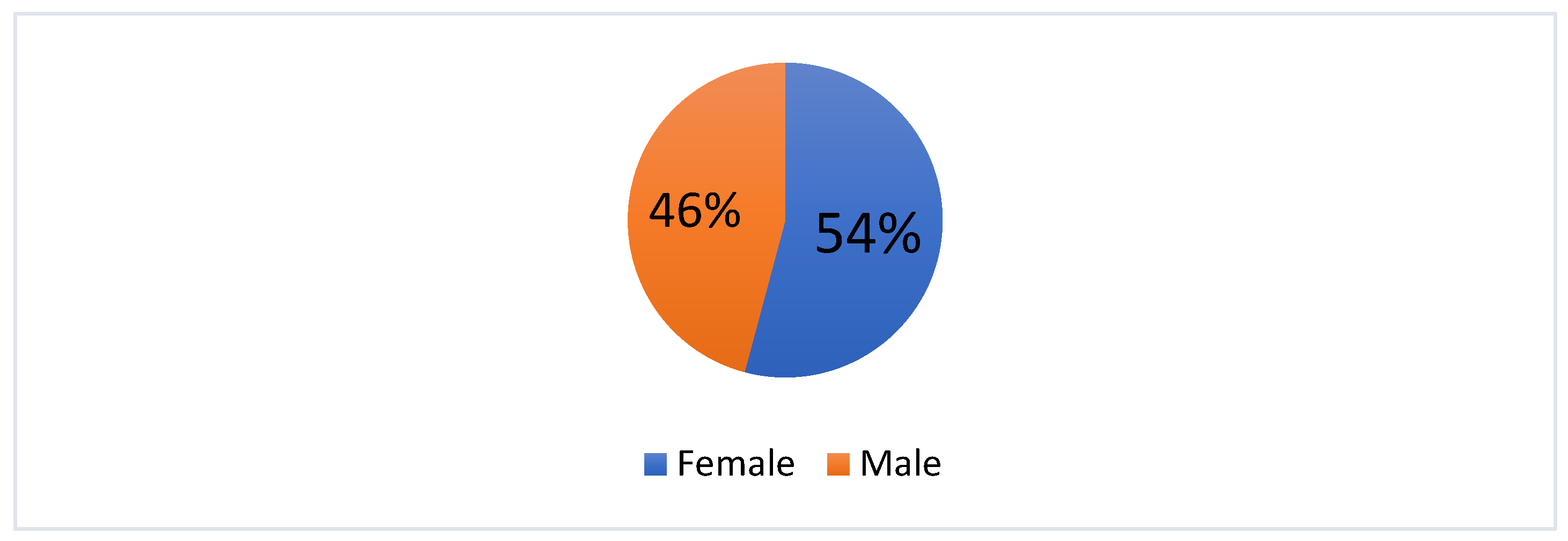

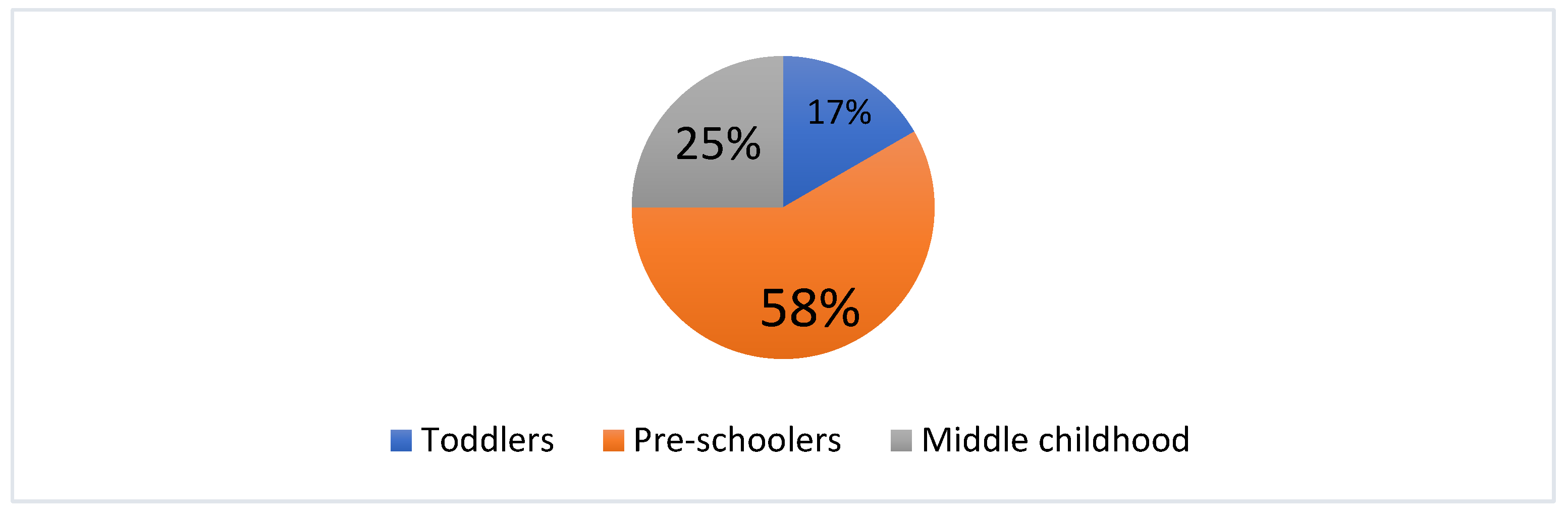

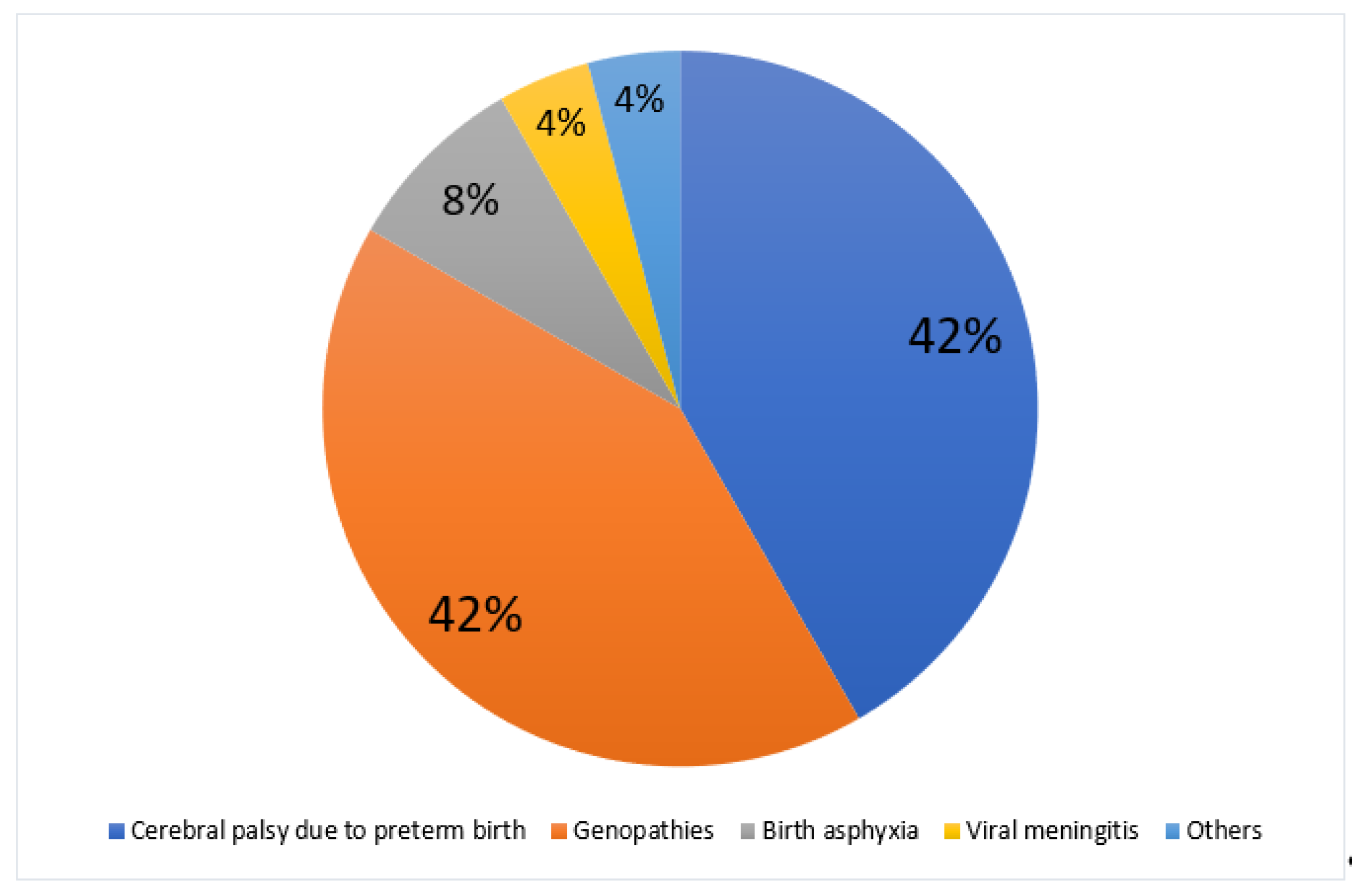

This sample was composed by 46% male and 54% female patients. At the moment of GT placement, the average age was 4.2 years old, from which 17% were toddlers, 58% were preschoolers, and 25% were middle childhood patients. Most patients were G-tubes users due to various genopathies and cerebral palsy (84%) (See

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

In order to analyze GT placement effectiveness, this data was divided in different age groups and into three nutritional assessment categories: BMI/age, weight/age and length/age.

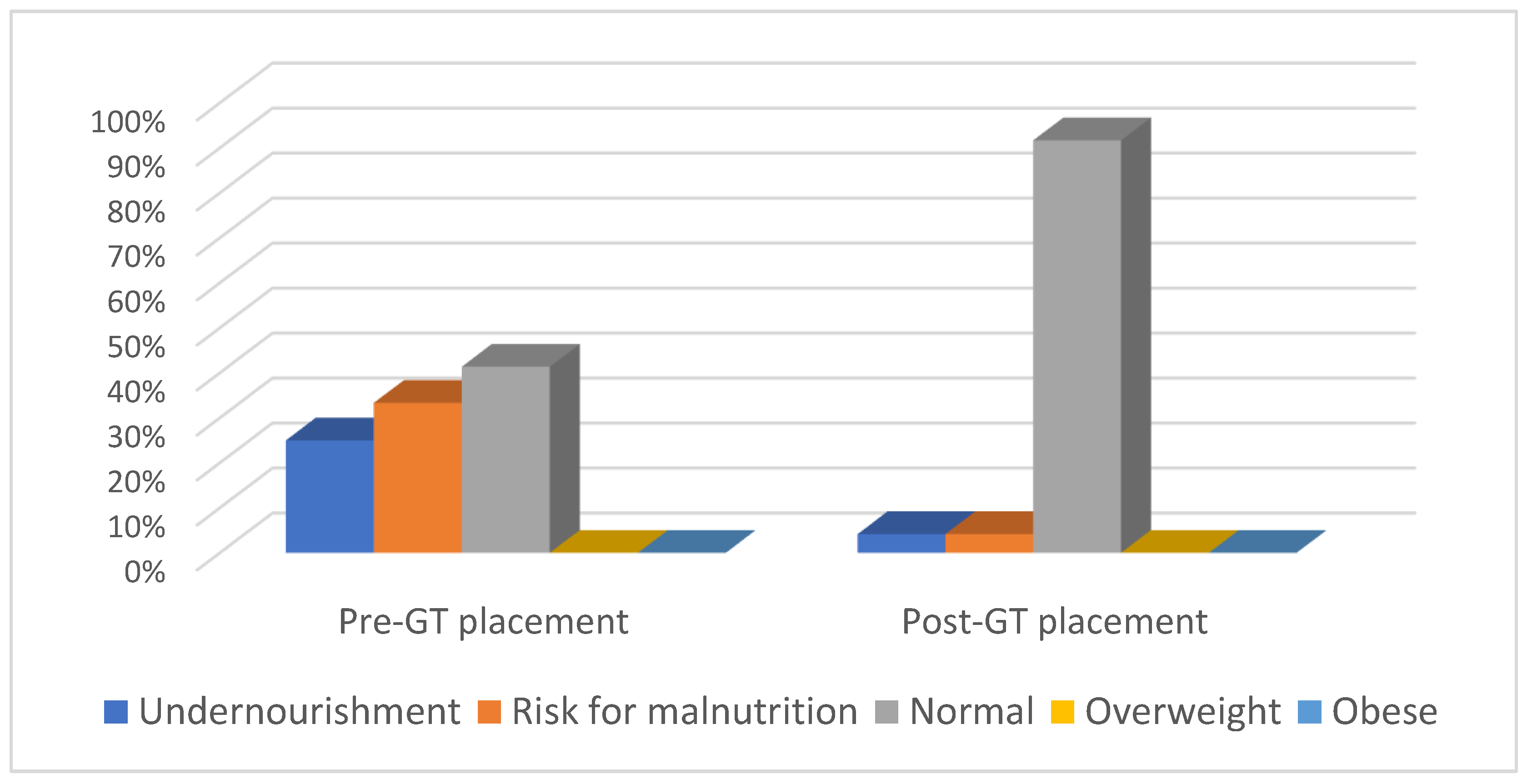

As for BMI/age assessment, it was observed that undernourishment prevalence rate reached 25% prior to GT placement, from which 83.33% and 16.67% of them were preschoolers and middle childhood patients, respectively. After GT placement, undernourishment was reduced to 4.1%, being prevalent only in preschoolers. As for risk for malnutrition, it reached 33.33% prior to GT placement, from which 37.5%, 50% and 12.5% were toddlers, preschoolers and middle childhood patients, respectively. After GT placement, risk for malnutrition was reduced to 4.1%, being prevalent only in toddlers. Finally, as for normal nutritional status, it reached 41.6% prior to GT placement, from which 10%, 50% and 40% were toddlers, preschoolers and middle childhood patients, respectively. After GT placement, normal nutritional status increased to 91.6% in the entire sample, from which 13.64%, 59.09% and 27.27% were toddlers, preschoolers and middle childhood patients, respectively. No CP patients were overweight or obese. (See

Figure 4). The aforementioned values were not statistically significant (p<0.228).

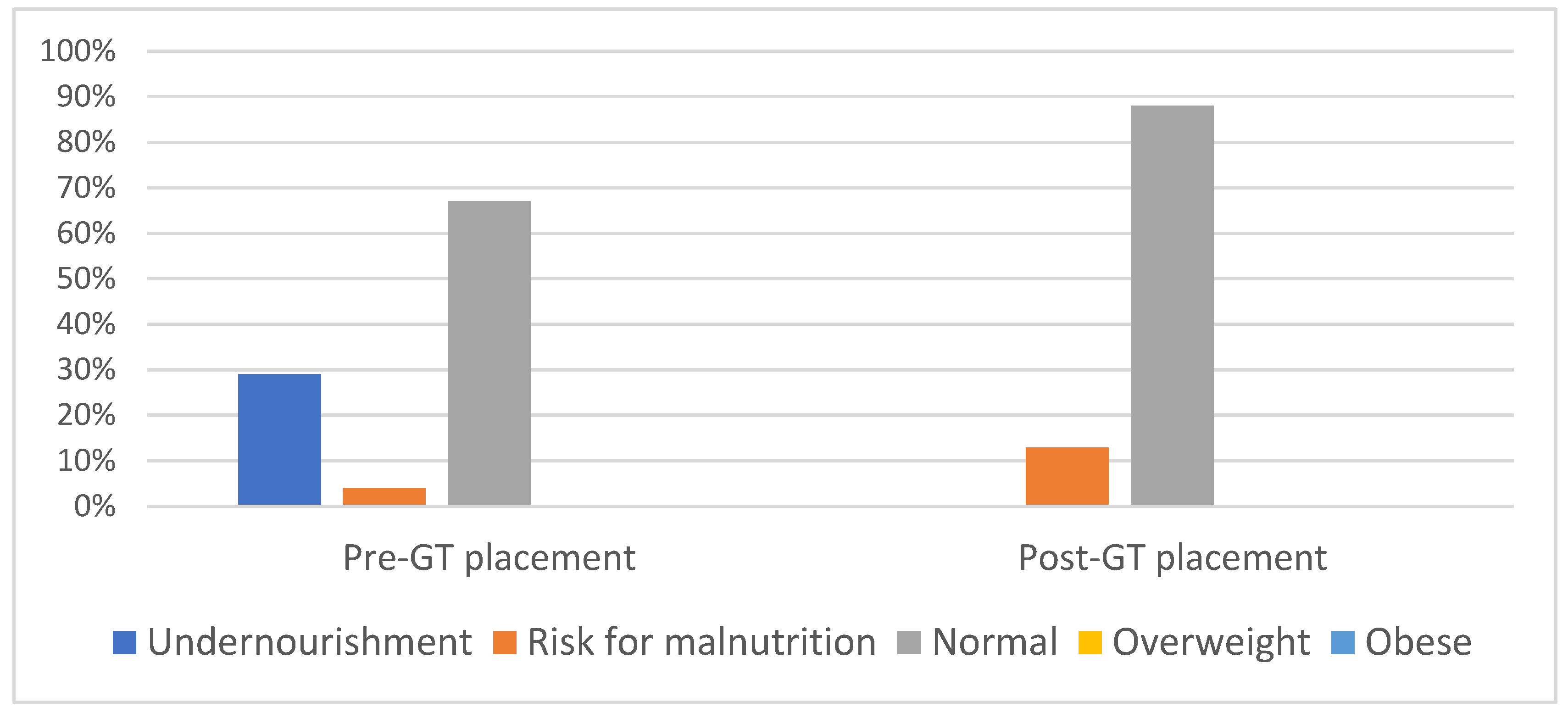

As for Weight/age assessment, it was observed that undernourishment prevalence rate reached 29.17% prior to GT placement, from which 14.28%, 71.42% and 14.28 of them were toddlers, preschoolers and middle childhood patients, respectively. After GT placement, undernourishment was reduced to 0%.

As for risk for malnutrition, it reached 4.17% prior to GT placement, from which 100% were preschoolers. After GT placement, risk for malnutrition increased to 12.5%, being prevalent in toddlers (66.6%) and middle childhood (33.3%) patients.

Finally, as for normal nutritional status, it reached 66.67% prior to GT placement, from which 18.75%, 50% and 31.25% were toddlers, preschoolers, and middle childhood patients, respectively. After GT placement, normal nutritional status increased to 87.50% in the entire sample, from 9.52%, 66.66% and 23.8% were toddlers, preschoolers, and middle childhood patients, respectively. No CP patients were overweight or obese. (See

Figure 5). The values were not statistically significant (p<0.308).

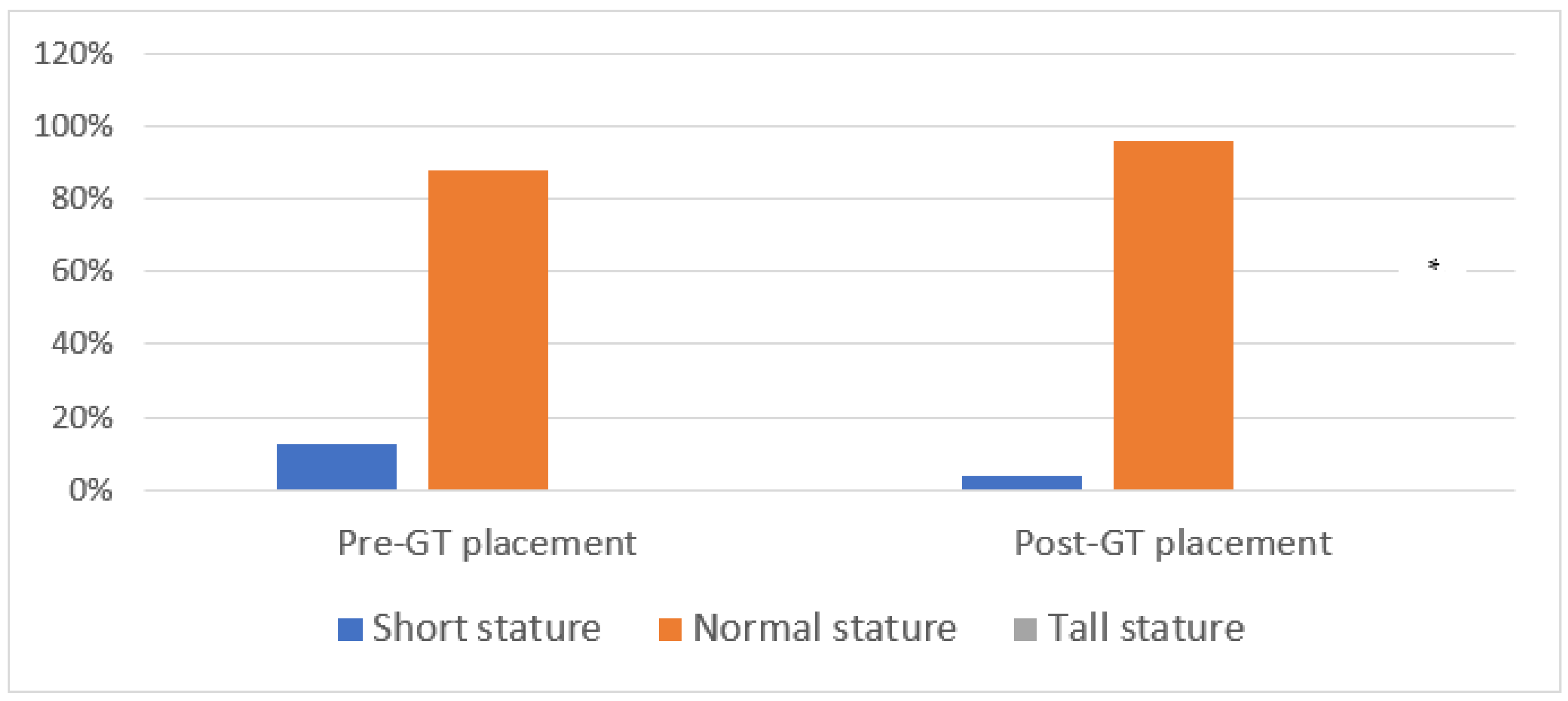

As for Length/age assessment, it was observed that abnormal growth (short stature/age) prevalence rate reached 12.50% prior to GT placement, from which 66.66% and 33.33% of them were preschoolers and middle childhood patients, respectively. After GT placement, short stature was reduced to 4.17%, being prevalent only in preschoolers.

Finally, as for normal growth, it reached 87.50% prior to GT placement, from which 19.04%, 57.14% and 23.8% were toddlers, preschoolers, and middle childhood patients, respectively. After GT placement, normal nutritional status increased to 95.83% in the entire sample, from 17.39%, 56.52% and 26.08% were toddlers, preschoolers, and middle childhood patients, respectively. No CP patients showed abnormal growth (tall stature/age) (See

Figure 6). These values were statistically significant (p<0.002).

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to analyze the chronic use of enteral nutrition in Arica, one of the most resources-limited regions of Chile [

8].

Current data show a variety of negative aspects related to persistent use of gastrostomy tubes. A systematic review states that present recommendations come exclusively from four and five evidence [

9], which could lead to an overuse of G-Tubes worldwide; their analyses show that there is lack of scientific evidence to indicate G-tubes over nasogastric tubes (NGT). This report also affirms that most children can be fed orally, even those with oropharyngeal dysphagia, since swallowing disorders tend to decrease over time, mainly due to oral therapy, and after hospital discharge, GTs should only be considered when individuals fail to thrive with NGT [

9].

Current data report that mortality rates increase after GT placement [

10,

11,

12,

13], even up to 10% of cases. Other severe complications can be pneumonia, and the re-hospitalization rates after these procedures remain high throughout ongoing literature. Another consequence to be taken into consideration is that GT placements are inversely related to oral intake rehabilitation [

6] and are being placed in acute needs [

1].

When comparing the access to rehabilitation programs between developed and developing countries the difference is still significant, thus considering international recommendations require a deeper understanding of public services delivered by each country; these must answer to the populations’ necessities along with their health environments. Other studies suggest surgeons to consider the costs of chronic maintenance of enteral nutrition for the health system [

1], and the caregiver’s burden of patients with gastrostomy tubes [

14].

On the other hand, studies carried out in other areas of the world, like Latin America and Asia [

15,

16,

17] report nutritional improvement in both anthropometric and biochemical parameters in people who are tube fed for over a year, including those patients who require special treatments. This emphasizes the importance of international experiences like Chile’s in these regards.

Other health benefits associated to enteral feedings with G-tubes are important reduction of hospitalizations [

18], prevention of weight loss, reduction of treatment delay, and improve over-all quality of life [

19]. Additionally, gastrostomies are considered a safe procedure and can extend life [

20,

21,

22,

23], even in patients without neurologic impairment [

24].

The ESPGHAN showed in a systematic review that morbidity and mortality rates are reduced after tube insertion [

25], emphasizing that a multidisciplinary approach must be taken into consideration to deliver the best possible treatment, not only during surgery but also after it is inserted. On the other hand, newer procedures are being used in order to reduce complications [

26] with promising results. Finally, due to different health and family contexts in developing countries, gastrostomy tubes remain a crucial tool to prevent early morbidity and mortality in children, and must be considered within multidisciplinary teams.

5. Strengths and Weaknesses of the Study

This study contains the entire tube fed population of a border city of Chile, serving as a representative sample of the disease in extreme regions of developing countries. In addition, a cohort-type study delivers valuable information regarding issues faced by chronically ill communities. Finally, only validated parameters (e.g., anthropometric tools) were used in this study to assess this population’s behavior during the first use of enteral feeding. More time (y) could be needed to extrapolate these results. Large randomized controlled trials are required to confirm the efficacy of gastrostomy tubes for patients who undergo enteral nutrition in developing countries.

6. Conclusions

This study has confirmed that enteral nutrition is key to improve nutritional status in long-term parameters despite new evidence showing negative aspects of gastrostomy tubes. GTs have been proven to reduce morbidity, mortality, and hospitalizations, as well as secure survival and improve quality of life of patients with different health conditions.

The authors of this study emphasize that current data showing negative aspects of GT placement and its prolonged time usage, come from developed countries, where rehabilitation is part of the treatment of tube-fed patients. Whereas rehabilitation in resource-poor countries is not broadly available, leading to chronic use of GTs to secure survival.

Author Contributions

RC.; conceptualization, writing, original draft, writing, review and editing, and project administration. JVV; conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing, original draft, writing, review and editing. SDA; writing, review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data availability will be upon request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jackson J, Theodorou C, Vukcevich O, Brown E, Beres A. Patient selection for pediatric gastrostomy tubes: Are we placing tubes that are not being used? J Pediatric Surgery 2021 Jun; 57(2022):532-537.

- Doley J. Enteral Nutrition Overview. Nutrients 2022 May; 14(1):2180.

- Nwafor I, Akanni B, Obi C, Nsude I. The profile and clinical spectrum of indications, challenges and complications for gastrostomy or jejunostomy in a developing country: A 2 center study. African J. Medical and Health Sciences 2022 Oct; 22(5):35-40.

- Yildiz A, Sungurtekin U, Celik M, Sugurtekin H. Retrospective analysis of the long-term outcomes of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in critically ill patients and the satisfaction of their caregivers. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sc 2023; 27(1):1104-1109. [CrossRef]

- Khrais A, Ismail M, Kahlam A, Shaikh A, Ahlawat S. Trends Regarding Racial Disparities Among Malnourished Patients with Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy (PEG) Tubes. Cureus 2022 Nov; 14(11):31781. [CrossRef]

- Bahraini A, Purcell l, Cole K, Koonce R, Richardson L, Trembath A, et al. Failure to thrive, oral intake, and inpatient status prior to gastrostomy tube placement in the first year of life is associated with persistent use 1-year later. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 2022 Mar; 57(1): 723-727. [CrossRef]

- Jahan I, Sultana R, Muhid M, Akbar D, Karim T, Mahmudul H, et al. Nutrition Intervention for Children with Cerebral Palsy in Low-a and Middle-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2022 March; 14:1211. [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Vivienda. Datasocial. [Internet]. 2020; [cited 2023 Jul 18]. Retrieved from: https://datasocial.ministeriodesarrollosocial.gob.cl/portalDataSocial/catalogoDimension/47.

- Berman L, Baird R, Sant’Anna A, Rosen R, Petrini M, Celluci M, et al. Gastrostomy Tube Use in Pediatrics: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2022 Jun; 149(6):2021055213. [CrossRef]

- Young Pih G, Kyong Na H, Yong Ahn J, Wook Jung K, Hoon Kim D, Hoon Lee J, et al. Risk factors for complications and mortality of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy insertion. BMC Gastroenterology 2018 Jun;18(1):101.

- Löfling Skogar M, Sundbom M. Time trends and outcomes of gastrostomy placement in a Swedish national cohort over two decades. World J Gastroenterol 2024 March; 30(10): 1358-1367.

- Lima DL, Miranda LEC, Lima RNCL, Romero-Velez G, Chin R, Shadduck PP, et al. Factors Associated with Mortality after Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy. JSLS 2023 Apr; 27(2): 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wong K, Glasson EJ, Jacoby P, Srasuebkul P, Forbes D, Ravikumara M, et al. Survival of children and adolescents with intellectual disability following gastrostomy insertion. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2020 Jul;64(7):497-511. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien K, Scaife J, Iantorno S, Bucher B. Caregiver health-related quality of life 1 year following pediatric gastrostomy tube placement. Surgery Open Science 2022 Aug; 10(2022): 111-115. [CrossRef]

- Qiuping W, Xiaohua G, Yan B, Qun Y, Lili L, Min H. Nutritional management of a child with glycogen storage disease type Ia combined with feeding disorders undergoing gastrostomy: a case report. Authorea 2023 Jun.

- Ayala-Germán A, Ignorosa Arellano K, Díaz-García L, Zárate-Mondragón F, Toro-Monjaraz E, CCadena-León J, et al. Nutritional benefits in pediatric patients with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy placement. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2022 Nov;114(11):680. [CrossRef]

- Jung S, Moon H, Kim T, Park J, Kim J, Kang S, et al. Nutritional Impact of Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy: A Retrospective Single-center Study. Korean J Gastroenterol Dic 2021; 79(1): 13-21. [CrossRef]

- Jacoby P, Wong K, Srasuebkul P, Glasson J, Forbes D, Ravikumara M, et al. Risk of Hospitalizations Following Gastrostomy in Children with Intellectual Disability. The Journal of Pediatrics 2020 Feb; 217(1): 131-138. [CrossRef]

- Xu Q, Guo L, Lou J, Chen L, Wang Y, Chen L, et al. Effect of prophylactic gastrostomy on nutritional and clinical outcomes in patients with head and neck cancer. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2022 May; 76(11):1536-1541. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe J, Kotani K. Early versus Delayed Feeding after Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy Placement in Children: A Meta-Analysis. Children 2020; 7(9): 124. [CrossRef]

- Pih GY, Na HK, Hong SK, Ahn JY, Lee JH, Jung KW, et al. Clinical Outcomes of Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy in the Surgical Intensive Care Unit. Clin Endosc. 2020 Nov; 53(6):705-716. [CrossRef]

- Mawatari F, Miyaaki H, Arima T, Ito H, Matsuki K, Fukuda S, et al. Procedure-Related Complications and Survival after Gastrostomy: Results from a Japanese Cohort. Ann Nutr Metab 2021 Feb; 76 (6): 413–421. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Yuan T, Yang H, Zhou X, Cao J. Effect of complete high-caloric nutrition on the nutritional status and survival rate of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients after gastrostomy. Am J Trans Re 2022 Oct; 14(11): 7842-7851.

- Corsello A, Trovato CM, Dipasquale V, Proverbio E, Milani GP, Diamanti A, Agostoni C, Romano C. Malnutrition management in children with chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2025 Jan;40(1):15-24. [CrossRef]

- Homan M, Hauser B, Romano C, Tzivinikos C, Torroni F, Gottrand F, et al. Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy in Children: An Update to the ESPGHAN Position Paper. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2021 Sep;73(3):415-426. [CrossRef]

- Corsello A, Antoine M, Sharma S, Bertrand V, Oliva S, Fava G, Destro F, Huang A, Fong WSW, Ichino M, Thomson M, Gottrand F. Over-the-scope clip for closure of persistent gastrocutaneous fistula after gastrostomy tube removal: a multicenter pediatric experience. Surg Endosc. 2024 Nov;38(11):6305-6311. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).