Submitted:

14 January 2025

Posted:

15 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

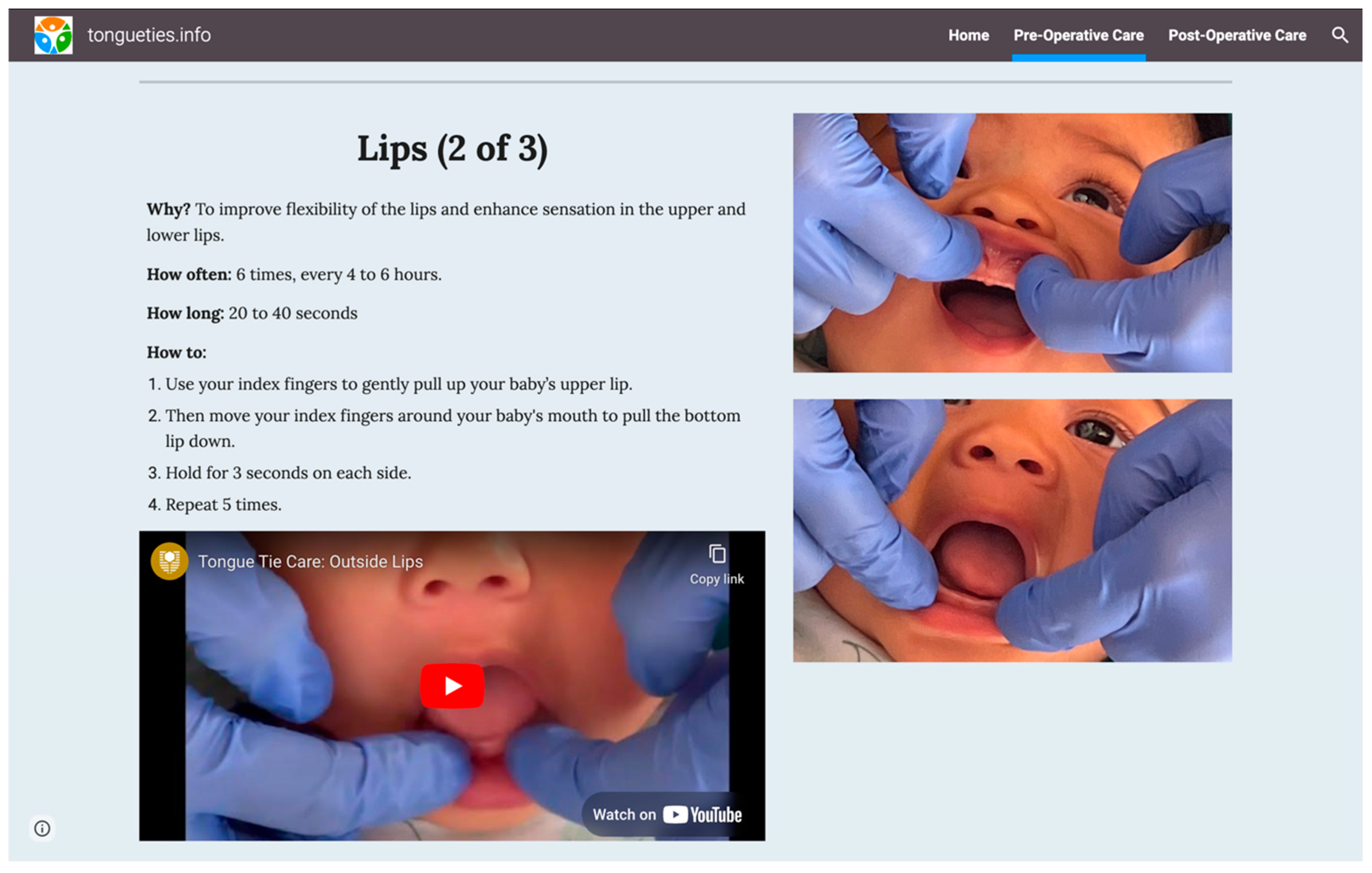

2.2. Materials

2.3. Procedure

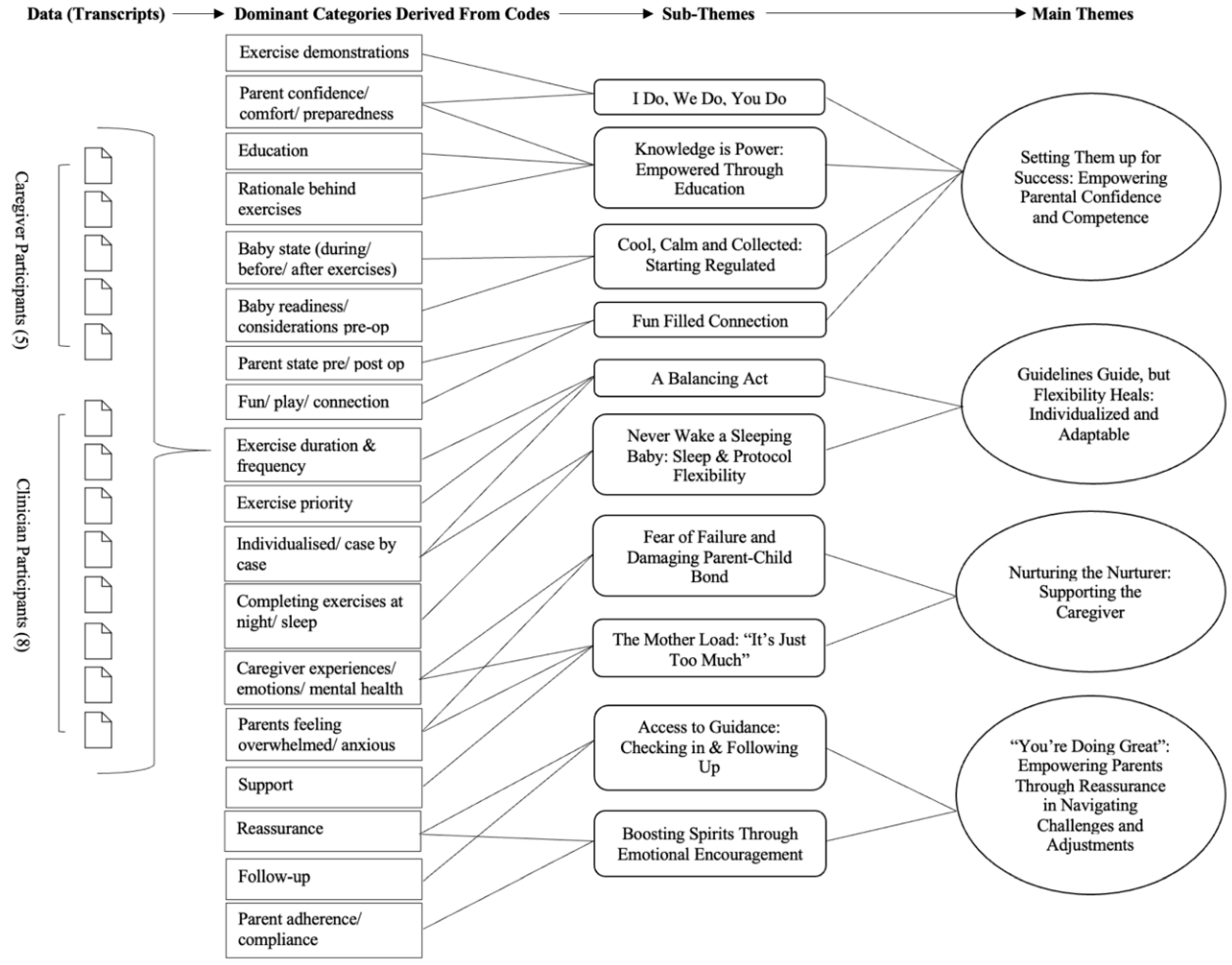

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

| Event/Platform | Location | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Australian Society for Tethered Oral Tissues (ASTOT) Symposium | Gold Coast, Queensland | March 2024 |

| International Consortium of Oral Ankylofrenula Professionals (ICAP) Conference | Cleveland, Ohio, United States of America | May 2024 |

| Speech Pathology Australia (SPA) Conference | Perth, Western Australia | May 2024 |

| International Consortium of oral Consortium Professionals (ICAP) Active Members Group (186 members) | May 2024 |

| Main Theme | Subtheme | Supporting Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Setting Them up for Success: Empowering Parental Confidence and Competence | I Do, We Do, You Do | “Maybe a demonstration would come in handy with handing out hard copies as well. Even just like when you're at the appointment, you're bringing along the caregiver as well, who's going to be doing it. And you can give them that sort of demonstration on baby and show them how it works with their child.” (P1) |

| “I think perhaps it would be a face-to-face conversation with a health professional who can show the exercises on your baby in real time to show how it works and then with some opportunity for the parent to give it a go and practise and then receive feedback from that health professional.” (P3) =’’ | ||

| “I think them really being prepared and seeing how baby responds before, so doing the stretch and seeing the baby's not crying or even if baby does cry, as soon as we pick them up and snuggle and cuddle, they calm down really quickly. That has really helped to reassure them.” (C3) | ||

| “But just to have the physician do them first because you do find that because you're scared you’re going to squeeze too hard, you're scared you’re going to tear their lips open.” (P2) | ||

| Knowledge is Power: Empowered Through Education | “You know, I feel that education is key for this. Like, we have to empower parents to take in all the information, you know, make it as easy for them to understand and then let them make their own decisions.” (C4) | |

| “Knowledge is power, so you’ve got to deliver it in a way that’s not scaring the bejeezus out of them.” (C5) | ||

| “And I think if parents know the reason, then they're more motivated to do it, or perhaps they may feel more accountable.” (P3) | ||

| “And then I think what was really valuable was the specificity. Like you've given a rationale which I think is really important and will help with adherence.” (C8) | ||

| Cool, Calm, and Collected: Starting Regulated | “Also just starting with a regulated baby. So, if the baby is already going crazy and upset, we first have to co-regulate before we would start this. Otherwise, we're setting them up to have that negative association with all of these mouth exercises, which we really don't want to do.” (C6). | |

| “But if you're trying to get the baby's tongue moving in a certain way, the tension can't be there. They have to be in a relaxed state, like a quiet alert state, especially for a young infant.” (C4) | ||

| “Consideration needs to be made around when bub is most comfortable.” (P2) | ||

| “Because an unsettled baby doing exercises and trying to feed is just not good for anybody. I think it's more stressful in that parent child interaction and I really do think that impacts attachment and bonding and just the enjoyment of feeding as well.” (P3) | ||

| Fun Filled Connection | “And I tell parents to be really silly, make silly faces, be happy, give a whole positive experience and only do that at times when the infant is in a state to accept play. Not when they're tired, not when they're hungry.” (C4) | |

| “The more fun oral play we can be doing, even if it's just brief moments, then the more baby’s going to be comfortable with that, and the more mum’s going to see that they're comfortable with that and be comfortable doing it.” (C3) | ||

| “If you can just foster that connection during it... So, I do think that like having that real big hit of like, you know, the love hormones and the cuddles and the cuteness before having to do those exercises... just like lock eyes, skin to skin cuddles. I don't know, anything...playing, laughing, joking, to then move into the exercises and then go back to that connection.” (P5) | ||

| “And with a focus on deregulation - downregulation of that nervous system of both mum and baby, and just encouraging that connection from heart to heart, from mum to bub, just into a real place of harmony. And just helping the mum fall in love with her baby over and over and over.” (C5) | ||

| “It doesn’t matter how much you’ve stretched, it does not matter if you can’t get the brain and the heart and the emotional health and wellbeing of that dyad to a point where they can go baby, we’ve got this. I’ve got you. You’ve got me. We’ve got this sweetheart, I’m with you.” (C5) | ||

| Guidelines Guide, but Flexibility Heals: Individualized and Adaptable | A Balancing Act | “And to talk about how to make it achievable for that specific family and to fit it into their day, rather than it being like “Here it is. Go and do it.” I think a discussion of “How does your family work? How can we build this into your routine as much as possible? How can we set you up to succeed?” It's definitely not straightforward. It's not a one-size fits all approach for everyone.” (P3) |

| “I think spending some time with the parents trying to figure out what's the best time for them to do the stretches helps them to work it into their routine.” (C3) | ||

| “And I give different options because I don't think there's a one-size-fits-all. It depends on the day, and time of the day. Depends on what's going on in that...in the world of that family.” (C4) | ||

| “And then just on the bad days like prioritising which exercise is vital...Like, which one do you start with? Because if your baby really, really cracks it or something's really bad or there's been a family emergency and you've just got to get one done, which is it? What one are we prioritising?” (P5) | ||

| Never Wake a Sleeping Baby: Respecting Sleep Needs and Protocol Flexibility | “I think the sleep part is really important. If you can note down to make that part parent friendly, like if you can let them sleep if they are sleeping for seven hours...Yeah, counterintuitive as a parent after you've just rocked them to sleep for three hours. I guess like knowing about that would be good. That would definitely be a part of a good protocol I think” (P5) | |

| “I think that that instruction should be in there like, you know, try to do this at a point where you don't have to wake your baby up to do it, you know, try and get...try not to make this something that's disruptive to your sleep” (C4) | ||

| “I also wonder if there needs to be a little bit of flexibility in that tool allowing parents the flexibility in saying, you know, sometimes particularly overnight, you're not going to wake up before your baby is showing hunger cues to do the exercises and then feed them.” (P3) | ||

| Nurturing the Nurturer: Supporting the Caregiver | Fear of Failure and Damaging Parent-Child Bond | “Most parents will take things very literally, so if they don't do it every four to six hours, some parents may be like “I've ruined it. I failed. I'm doing my child a disservice.” […] and knowing you're not going to ruin your baby if you miss one of these rounds of exercises.” (P3) |

| “And if you miss one, you do, you feel like you're the worst parent ever and that you've ruined everything. And now we've ruined everything and we're going to go back to square one. So maybe just some wording around that.” (P5) | ||

| “If you’re told black and white, this is exactly what you have to do, and you don’t do it, you feel like a failure constantly.” (P1) | ||

| “I think they're...my main nurturing tips that it's OK, or even a video after the hand washing, with a little message from a mum [...] saying “It's OK. You only have like, 24 more to go. You're going to get through this, it's going to be OK. Your baby's not going to hate you,” because that's genuinely what you think [...]” (P5) | ||

| The Mother Load: “It’s just too much” | “A lot of it has to do with especially maternal anxiety. If I’ve got a mother that is highly anxious and her baby’s crying it triggers her anxiety. She’s less likely to adhere to a stretching post care protocol.” (C5) | |

| “I had a partner. I wasn't on my own and I didn't have other children, so he was my first child, so it was literally like literally like me and him 24/7 so I could focus all my attention. I wasn't working or anything like that. And coming from me, I still feel like maybe it is a lot.” (P1) | ||

| “I think there will be families that are going to read it and go “Far out. That's a lot.” You know, every four to six hours.” (P2) | ||

| “Because after doing the exercises, you almost want to run away and have a shower, hand the baby off to somebody and remove the trauma from you because you know you have to do it in six hours' time again. It sounds really dramatic, but that is how it feels when you're in the thick of it.” (P5) | ||

| “You’re Doing Great”: Empowering Parents through Reassurance in Navigating Challenges and Adjustments | Access to Ongoing Guidance: Checking in and Following Up | “And then also I allow them access to me, which I know not every provider would necessarily want, but I tell them “You're not going to bother me. Please message me photos if you want feedback, please video a stretch if you want feedback. [...] if I can respond, I will, and I really do want to see that.” I think that's been helpful, just the reassurance for them.” (C6) |

| “So yeah, after that sort of time. Even maybe day three, day four sort of thing to say. Look, just checking in, making sure everyone's going OK. Any questions? Anything you've noticed those sorts of things at that point, I think people would really appreciate that too.” (P1) | ||

| “Follow up would be good. It's not about that authoritative sort of focus. It's more “do you need further support? Is there anything we can help you with if you're having trouble getting them done? Is there anything that can be done to help you get them done?” Things might change for the family, so it's really important that they know that they do have that support there and that it's OK to ask for that help.” (P2) | ||

| Boosting Spirits Through Emotional Encouragement | “Comes down to like that whole reassurance that you don't have to complete every exercise, every single time, every minute of every day, like taking that pressure off to make sure that people are aware of that. That's really the main point.” (P1) | |

| “And just again, reassurance around yes, it looks it might look like it's a lot, but once you're actually doing it, you'll get into a rhythm. You'll get used to it. We don't expect you to be doing this day one straight away.” (P2) | ||

| “So, a reminder, I remind them that that's it's not forever. You don't have to do this for, you know for more than the four weeks recommend when it comes to the stretches.” (C2) | ||

| “It's just reassuring, connection, support. I think it all goes back to that, yeah.” (P5) |

3.1. Theme 1: Setting Them Up for Success - Parental Confidence and Competence

3.2. Theme 2: Guidelines Guide, but Flexibility Heals - Individualised and Adaptable

3.3. Theme 3: Nurturing the Nurturer - Supporting the Caregiver

3.4. Theme 4: You’re Doing Great - Empowering Parents Through Reassurance in Navigating Challenges and Adjustments

4. Discussion

Key Implications for Clinical Practice

- Holistic, Family-Centred Care. Emphasising the well-being of the both the infant and caregiver throughout the treatment journey, from diagnosis to aftercare.

- Interdisciplinary Collaboration. Highlighting the necessity of coordinated care between healthcare providers in pre-and post-operative exercises.

- Consistency Across Providers. Unified treatment philosophies and consistent messaging across healthcare providers to enhance caregiver confidence and pre- and post-operative care adherence.

- Tailored Aftercare Strategies. Provision of enhanced and tailored support, including focus on parent’s emotional wellness, stress management and practical guidance for pre- and post-operative exercises.

- Flexible but Standardised Protocols. To balance the pre-and post-operative care protocols with consideration for wellness and recovery, to optimise outcomes for infant, mother and family.

5. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Informed Consent Statement

Originality and Verification

References

- Hatami A, Dreyer CW, Meade MJ, Kaur S. Effectiveness of tongue-tie assessment tools in diagnosing and fulfilling lingual frenectomy criteria: a systematic review. Aust Dent J. 2022;67(3):212-9. [CrossRef]

- Unger C, Chetwynd E, Costello R. Ankyloglossia identification, diagnosis, and frenotomy: a qualitative study of community referral pathways. J Human Lact. 2020;36(3):519-27. [CrossRef]

- O’Connor ME, Gilliland AM, LeFort Y. Complications and misdiagnoses associated with infant frenotomy: results of a healthcare professional survey. Int Breastfeed J. 2022;17(1):1-9. [CrossRef]

- Australian Dental Association. Ankyloglossia and Oral Frena Consensus Statement. 2020. https://ada.org.au/unauthorized-access.

- Walsh J, Tunkel D. Diagnosis and treatment of ankyloglossia in newborns and infants: a review. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143(10):1032-9. [CrossRef]

- Akbari D, Bogaardt H, Lau T, Docking K. Ankyloglossia in Australia: Practices of health professionals. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2023;171:111649. [CrossRef]

- Shekher R, Lin L, Zhang R, Hoppe IC, Taylor JA, Bartlett SP, et al. How to treat a tongue-tie: an evidence-based algorithm of care. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021;9(1). [CrossRef]

- Messner AH, Lalakea ML. Ankyloglossia: controversies in management. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;54(2-3):123-31. [CrossRef]

- Ferrés-Amat E, Pastor-Vera T, Rodriguez-Alessi P, Mareque-Bueno J, Ferrés-Padró E. The prevalence of ankyloglossia in 302 newborns with breastfeeding problems and sucking difficulties in Barcelona: a descriptive study. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2017;18(4):319-25. [CrossRef]

- Ferrés-Amat E, Pastor-Vera T, Ferrés-Amat E, Mareque-Bueno J, Prats-Armengol J, Ferrés-Padró E. Multidisciplinary management of ankyloglossia in childhood. Treatment of 101 cases. A protocol. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2016;21(1):e39. [CrossRef]

- Ferrés-Amat E, Pastor-Vera T, Rodríguez-Alessi P, Ferrés-Amat E, Mareque-Bueno J, Ferrés-Padró E. Management of ankyloglossia and breastfeeding difficulties in the newborn: breastfeeding sessions, myofunctional therapy, and frenotomy. Case Rep Pediatr. 2016;2016. [CrossRef]

- Baxter R, Hughes L. Speech and feeding improvements in children after posterior tongue-tie release: a case series. Int J Clin Pediatr. 2018;7(3):29-35. [CrossRef]

- Bhandarkar KP, Dar T, Karia L, Upadhyaya M. Post Frenotomy Massage for Ankyloglossia in Infants—Does It Improve Breastfeeding and Reduce Recurrence? Matern Child Health J. 2022;26(8):1727-31. [CrossRef]

- Garrocho-Rangel A, Herrera-Badillo D, Pérez-Alfaro I, Fierro-Serna V, Pozos-Guillén A. Treatment of ankyloglossia with dental laser in paediatric patients: Scoping review and a case report. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2019;20(2):155-63. [CrossRef]

- Ghaheri BA, Cole M, Fausel SC, Chuop M, Mace JC. Breastfeeding improvement following tongue-tie and lip-tie release: A prospective cohort study. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(5):1217-23. [CrossRef]

- Jaikaria A, Pahuja SK, Thakur S, Negi P. Treatment of partial ankyloglossia using Hazelbaker Assessment Tool for Lingual Frenulum Function (HATLFF): A case report with 6-month follow-up. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2021;12(2):280. [CrossRef]

- Jaikumar S, Srinivasan L, Babu SK, Gandhimadhi D, Margabandhu M, et al. Laser-assisted frenectomy followed by post-operative tongue exercises in ankyloglossia: a report of two cases. Cureus. 2022;14(3). [CrossRef]

- Harun NA, Rashidi NAM, Teni NFM, Ardini YD, Jamani NA. Mothers' Perceptions and Experiences on Tongue-tie and Frenotomy: A Qualitative Study. Malay J Med Health Sci. 2022;18(2). [CrossRef]

- Dunwoodie K, Macaulay L, Newman A. Qualitative interviewing in the field of work and organisational psychology: Benefits, challenges and guidelines for researchers and reviewers. Appl Psychol. 2023;72(2):863-89. [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira B. Participatory action research as a research approach: Advantages, limitations and criticisms. Qual Res J. 2023;23(3):287-97. [CrossRef]

- Cornish F, Breton N, Moreno-Tabarez U, Delgado J, Rua M, de-Graft Aikins A, et al. Participatory action research. Nat Rev Methods Primers. 2023;3(1):34. [CrossRef]

- Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Teams [Internet]. 2024. Available from: https://www.office.com/.

- Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Streams [Internet]. 2024. Available from: https://www.office.com/.

- Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Word [Internet]. 2024. Available from: https://www.office.com/.

- Nvivo14 [Internet]. 2024. Available from: https://lumivero.com/product/nvivo/.

- Schütz Hämmerli N, Stoffel L, Schmitt K-U, Khan J, Humpl T, Nelle M, et al. Enhancing parents’ well-being after preterm birth—A qualitative evaluation of the “transition to home” model of care. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(7):4309. [CrossRef]

- Russell G, Sawyer A, Rabe H, Abbott J, Gyte G, Duley L, et al. Parents’ views on care of their very premature babies in neonatal intensive care units: a qualitative study. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:1-10. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Medina IM, Granero-Molina J, Hernández-Padilla JM, Jimenez-Lasserrotte MdM, Ruiz-Fernández MD, Fernández-Sola C. Socio-family support for parents of technology-dependent extremely preterm infants after hospital discharge. J Child Health Care. 2022;26(1):42-55. [CrossRef]

- Bry A, Wigert H. Psychosocial support for parents of extremely preterm infants in neonatal intensive care: a qualitative interview study. BMC Psychol. 2019;7(1):76. [CrossRef]

- Bhutani J, Bhutani S, Balhara YPS, Kalra S. Compassion fatigue and burnout amongst clinicians: a medical exploratory study. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34(4):332-7. [CrossRef]

- Weintraub A, Geithner E, Stroustrup A, Waldman E. Compassion fatigue, burnout and compassion satisfaction in neonatologists in the US. J Perinatol. 2016;36(11):1021-6. [CrossRef]

- Chan SH, Shorey S. Effectiveness of psychosocial interventions on the psychological outcomes of parents with preterm infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr Nurs. 2024;74:23-34. [CrossRef]

- Staveski SL, Parveen V, Madathil SB, Kools S, Franck LS. Parent education discharge instruction program for care of children at home after cardiac surgery in Southern India. Cardiol Young. 2016;26(6):1213-20. [CrossRef]

- Lee P. Pre and post procedure parent education to reduce anxiety related to tongue-tie [dissertation]. Grand Canyon University; 2018.

- Ray S, Hairston TK, Giorgi M, Links AR, Boss EF, Walsh J. Speaking in tongues: what parents really think about tongue-tie surgery for their infants. Clin Pediatr. 2020;59(3):236-44. [CrossRef]

- David Vainberg L, Vardi A, Jacoby R. The experiences of parents of children undergoing surgery for congenital heart defects: A holistic model of care. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2666. [CrossRef]

- Wang L-L, Ma J-J, Meng H-H, Zhou J. Mothers’ experiences of neonatal intensive care: A systematic review and implications for clinical practice. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9(24):7062. [CrossRef]

- The Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network. Developmentally supportive care for newborn infants: Practical guideline. 2022. Contract No.: 2006-0027.

- Warre R, O’Brien K, Lee SK. Parents as the primary caregivers for their infant in the NICU: benefits and challenges. Neoreviews. 2014;15(11):e472-e7. [CrossRef]

- Castles C, Stewart V, Slattery M, Bradshaw N, Roennfeldt H. Supervision of the mental health lived experience workforce in Australia: A scoping review. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2023;32(6):1654-71. [CrossRef]

- Rycroft-Malone J, Fontenla M, Seers K, Bick D. Protocol-based care: The standardisation of decision-making? J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(10):1490-500. [CrossRef]

- Ball, H. L., Taylor, C. E., Thomas, V., Douglas, P. S., & the SBY, w. g. (2020). Development and evaluation of ‘Sleep, baby & You’—An approach to supporting parental well-being and responsive infant caregiving. PLoS One, 15(8). [CrossRef]

| Participant | Healthcare Background/Discipline | Years of Experience | Client Age Range | Pre-op/Post-op Exercises |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | Paediatric Dentist | 16 | 2 weeks – 14 years | Yes |

| C2 | Dentist | 28 | All ages | Yes |

| C3 | Speech-Language Pathologist/ Certified Orofacial Myologist/ Certified IBCLC | 20 | All ages | Yes |

| C4 | RN/ Midwife/ IBCLC | 20 | All ages | Yes |

| C5 | Osteopath | 20 | Infants | Yes |

| C6 | Speech-Language Pathologist/ Certified Orofacial Myologist | 12 | All ages | Yes |

| C7 | Speech-Language Pathologist /OMT | 29 | All ages | Yes |

| C8 | Speech-Language Pathologist /OMT | 5 | 3+ years | Yes |

| Participant | Healthcare Background | Age of Child’s Tongue-Tie Diagnosis | Age at Time of Procedure | Procedure Type | Pre-/Post-Operative Exercises |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Medical Administration Role | Shortly after birth | 4 months old | Laser (Paediatric Dentist) | None provided. |

| P2 | Carer Peer Worker in Hospital | At birth | 10 years old | Supposedly cut during tonsillectomy | None provided. |

| P3 | Speech Pathologist (early intervention & paediatric feeding) | Child 1: 2 weeks old Child 2: 2 days old |

Child 1: 4-5 weeks old Child 2: 1 week old |

Child 1: Scissors, then laser (following unsuccessful initial surgery) Child 2: Laser |

Child 1: None provided. Child 2: ‘Vague’ post-op provided (every 4-6 hours, unclear instructions for how long). |

| P4 | Speech Pathologist | Child 1: 11 months Child 2: At birth. |

Child 1: 18 months Child 2: 4 weeks |

Child 1: Laser (ENT) Child 2: Laser (Dentist) |

Child 1: SP suggested functional exercises (e.g., funny faces, licking lips, licking ice-cream etc.) Child 2: Pre- and post-op exercises were provided (as part of feeding programme/structured programme on app). |

| P5 | Various Medical Administration Roles, Phlebotomist. | 2 weeks old | Surgery 1: 4 weeks old Surgery 2: 5 months old |

Surgery 1: Scissors Surgery 2: Laser |

Surgery 1: None provided. Surgery 2: Only post provided (sweeps & stretches, every 6hrs for 2 weeks) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).