Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

16 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Chemical Classes of Antioxidant Phytochemicals: Structural Significance

2.1. Unsaturated Fatty Acids

2.2. Carotenoids

2.3. Polysaccharides

2.4. Phenolic Compounds

| Class | Compound | Main source | Concentration | Assay | AA | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UFAs* | ||||||

| ω-3 | ALA | Olive, sunflower, linseed, rapeseed, fruit and vegetable seeds, other oily crops | 5.5–61.5% | ROS | 16.86 mM | [71,72,73,74] |

| EPA | Seaweed, microalgae, fish oil | 6.6–22.5% | ROS | 150 µM | [75,76] | |

| DHA | Seaweed, microalgae, fish oil | 1–6.6% | ROS | 100 µM | [75,77,78] | |

| ω-6 | LA | Olive, sunflower, linseed, rapeseed, nuts, fruit and vegetable seeds, other oily crops | 16.5–62.5% | ROS | 39.5 mM | [71,74,79,80,81] |

| ω-7 | PA | Olive, nuts, macadamia nuts, microalgae | 0.6–50.1 | – | – | [82,83,84,85,86] |

| ω-9 | OA | Microalgae, linseed, rapeseed, nuts, fruit and vegetable seeds, other oily crops | 1.4–79.6% | SOD | 53.1 mM | [74,75,83,87,88,89] |

| Carotenoids | ||||||

| Carotenes | α-carotene | Carrots, pumpkins | 13.44–30.11 mg/kg fw | ROS | 40.6 µmol TE/g dw | [90,91] |

| β-carotene | Carrots, red peppers, oranges, potatoes, green vegetables | 41.60–71.2 mg/kg fw | ROS | 7.2 µmol TE/g dw | [90,91] | |

| Xanthophylls | Fucoxanthin | Brown algae | 0.02-18.60 mg/g dw | ROS | 201 μg/mL | [29,92] |

| Astaxanthin | Haematococcus pluvialis | 3.8 % | ROS | 1.33 mM | [93] | |

| Lutein | Microalgae, algae, vegetables (i.e., kale, spinach) | 0.7-5% dw | ROS | 1.8-22 μg/mL | [94] | |

| Zeaxanthin | Red and brown seaweed, red/orange vegetables/fruits | 0.49-1230 µg/g dw | ROS | 2.2 μg/mL | [29,95] | |

| β-cryptoxanthin | Algae, red/orange vegetables/fruits | 409-1103 µg/g dw | ROS | 38.30 μg/mL | [96,97] | |

| Polysaccharides | ||||||

| HE | Hyaluronic acid | Streptococcus spp., Tremella fuciformis | 1300 µg/mL | ROS | 69.2-78.4% | [98,99] |

| Chondroitin sulfate | Bacteria and cartilage | - | Metal cations chelation | 3.33 mg/mL | [100,101] | |

| Heparin | Marine organism, Asteraceae | - | Enzymatic antioxidants | 2.20 mg/mL | [102,103] | |

| HO | Fructan | Prokaryotes, lower and higher plants | 0.9–1.8 g/100 g in different wheat cultivars | Enzymatic antioxidants, metal cations chelation | 0.12 mg/mL | [15,104] |

| Galactan | Seaweeds, seeds of some plants | - | SOD and GSH-Px | 9 μM | [105] | |

| Plant | Pectin | Cell walls of terrestrial plants | Citrus peels 30% fw, oranges 0.5-3.5 % fw, carrots 1.4 % fw | ROS | 161.94 ppm | [106,107] |

| Cellulose | Cell walls of terrestrial plants | 40-50% fw | ROS | 80.9 ppm | [108,109] | |

| Starch | Cereals, pseudocereals,umes | 60-75 % fw | ROS | 97 µg/mL | [110,111] | |

| Microbial | Curdlan | Agrobacterium sp., Rhizobium sp. | 34.04 mg/g | ROS | 82 % DPPH, 72% ABTS | [112,113] |

| Dextran | Lactic acid bacteria | 580 mg/100 mL dw | ROS | 97 μg/mL | [114,115] | |

| Cellulose | Acetobacter spp., Sarcina spp., Agrobacterium spp. | 60.7 % dw | ROS | 80.9 ppm | [108,116] | |

| Fungi | β-glucans | Mycetes’ cell walls | 31% dw | ROS, antioxidant enzyme | 161-4019 μg/mL | [117,118] |

| Chitosan | Cell wall of filamentous fungi | 20-45% dw | ROS | 0.022 mg/mL | [119,120] | |

| Marine | Fucoidan | Brown seaweed | 20% dw | ROS | 0.058 mg/mL | [121,122] |

| Alginate | Brown seaweed | 20-60 % dw | ROS | 121.4-346.3 mol/g | [123,124] | |

| Cellulose | Green algae | 1.5-34 %dw | ROS | 0.15–0.39 mg/mL | [116,125,126] | |

| Phenolic compounds | ||||||

| Total PC | - | Phoenix dactylifera var Bunarinja | 34.90 mg/ 100g fw | ROS | 0.875 μg/mL | [127] |

| Phenolic acids | Caffeic acid | Green coffee | 6.56 μg/mL | ROS | 6.31 μg/mL | [128] |

| Cichoric acid | Echinacea purpurea | 56.03 mg/g dw | ROS | 15 μg/mL | [129] | |

| Ferulic acid | Rice bran | 8.71 mg/g | ROS | 9.9 μg/mL | [130,131] | |

| Flavonoids | Quercetin | Onion skin | 2, 122 mg/g | ROS | 62.27 μg/mL | [132] |

| Myricetin | Green tea | 0.40-0.79 mg/g | ROS | 4.68 µg/mL | [133] | |

| Apigenin | Gentiana veitchiorum | 37.50 mg/L | ROS | 8.26 mg/mL | [134] | |

| Total tannin | - | Ginger | 35.08 mg/g | ROS | 1 mg/mL | [135] |

| - | Garlic | 7.44 mg/g | ROS | 3.7 mg/mL | [135] | |

| - | Myristica fragrans | 14.03 % w/w | ROS | 89.98 μg/mL | [136] | |

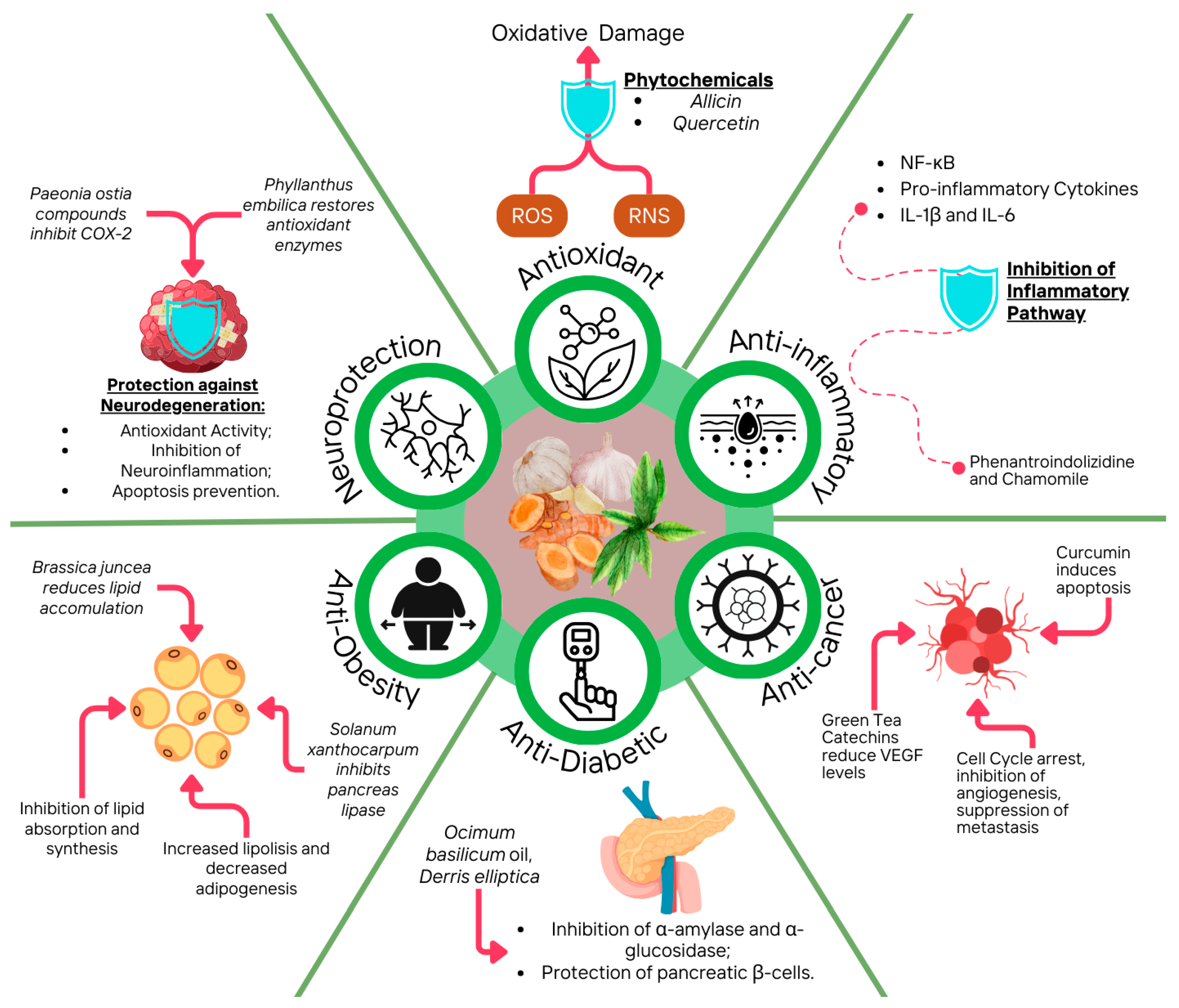

3. Chemopreventive and Therapeutic Properties of Antioxidant Phytochemicals

3.1. Antioxidant

3.2. Anti-Inflammatory

3.3. Antidiabetic

3.4. Antiobesity

3.5. Neuroprotective

| Plant species | Extract/ Fraction | Phytochemical compound | Chemopreventive activity | Analysis Method | Trial type | Mechanism of action | Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antioxidant activity | ||||||||

| Garlic (Allium sativum L.) | ns. | Allicin (purity >90%) | Anti-tumor (Cholangiocarcinoma) | CCK-8, colony formation, FC, WB | In vitro/In vivo | STAT3 inhibition via SHP-1 upregulation | Suppressed proliferation, invasion, EMT, and tumor growth | [140] |

| ns. | HS-1793 | Resveratrol analogue | Anti-tumor (Murine breast cancer) | LYM proliferation, DNA damage assessment, Treg and TAM analysis | In vivo | Inhibition of LYM damage and immune suppression by Tregs and TAMs | Enhanced LYM proliferation, reduced Tregs, and decreased IL-10/TGF-β | [141] |

| Green tea‒Curcuma longa L. | ns. | Catechins and curcumin | Anti-tumor (OSCC) | Histology, Immunofluorescence, FC | In vivo | AP induction and anti-angiogenesis | Increase in AP and reduction in tumor growth | [138] |

| Melilotus officinalis L. | ns. | DC (coumarin derivative) | Anti-proliferative, gonad-safe | DC injection in BALB/c mice ovarian apoptosis, meiotic spindle | In vitro/In vivo | Alteration of cell cycle dynamics without effect on microtubule stability | DC suppressed cell proliferation and increased AP in Vero and MCF-7 cells | [142,174] |

| Polyalthia longifolia L. | ME | Tetranorditerpene | Anti-cancer (prostate, leukemia cells) | Proteomic analysis | In vitro | Activates ER stress, induces apoptosis | Inhibits prostate cancer, leukemia cell growth | [175] |

| Fagonia cretica L. | AqE | ns. | Cytotoxic, induces cell cycle arrest | siRNA knockdown, MTT and FC, comet assay, WB | In vitro | Induction of DNA damage, and activation of p53 and FOXO3a | Induce cell cycle arrest and AP in two phenotypic breast cancer cell lines | [143] |

| Onobrychis argyrea L. | ME (leaves) | Quinic Acid, Isoquercitrin, Epicatechin, Routine | Antioxidant, antidiabetic, anticancer | LC-MS/MS, DPPH, Iron Reduction, Enzyme Inhibition, XTT, FC | In vitro | ME induces apoptosis in HT-29 cells by disrupting mitochondrial membranes and activating caspases | High antioxidant, enzyme inhibition, strong anti-cancer capacity | [147] |

| Elephantopus mollis Kunth. | ME | 3,4-di-O-caffeoyl quinic acid | Cytotoxicity and -glucosidase inhibitory effects | DPPH, FRAP, Metal Chelating, β-Carotene, Cytotoxicity | In vitro | Induces cell death in NCI-H23 cells by triggering apoptosis | High antioxidant, induces apoptosis | [146] |

| Thymus vulgaris L. | MetE, EAE, ChE, BolE, AqE, PEE | Polyphenols, tannins, flavonoids and sterols/triterpènes | Antioxidant | DPPH, ABTS, Ferrous Ion Chelation, CVT | In vitro | Radical scavenging, metal chelation, and electrochemical reduction | Strong antioxidant capacity correlated with phenol and flavonoid content | [176] |

| Markhamia lutea L. | Leaves extract | Flavonoids (O-glycosides) | Antioxidant, Anti-AChE, Anti-BChE, Aβ-amyloid-42 inhibition | DPPH, ORAC, Iron Reduction, FRAP | In silico/ in vitro | Induces antioxidant effects and inhibits AChE, BChE, and Aβ-amyloid 42 | DPPH: 35.69 µg/mL, ORAC: 16,694.4 μM TE/mg, and iron chelation: 70.7 μM EDTA eq/mg | [145] |

| Hertia cheirifolia L. | Organic and ethyl acetate fraction | Total phenolics (100–250 mg GAE/g) | Antioxidant | DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, β-carotene | In vitro | Synergistic mechanisms between different biomolecules | DPPH: 38.83 µg/ml,ABTS: 23.76 µg/ml; FRAP: 2628.87 µmol Fe²⁺ Eq/mL; β-carotene: 58.91% | [177] |

| ns. | AqE | QUE | Anticarcinogenic (hepatocellular carcinoma) | WB, RT-PCR | In vitro | Downregulation of ROS, PKC, PI3K, COX-2; Upregulation of p53, BAX | QUE modulated OS and apoptotic pathways in HepG2 cells | [144] |

| Anti-inflammatory activity | ||||||||

| Tylophora ovata L. | Natural and synthetic PAs | O-methyltylophorinidine (1, 1s) | Anti-tumor against TNBC | NFκB inhibition, 3D co-culture | In vitro | Stabilizes IκBα, blocks NFκB | Inhibits spheroid growth, surpasses paclitaxel | [151] |

| Mangifera indica L. | ns. | Polyphenols | Anti-inflammatory, anticancer | Real-time PCR analysis and protein expression | In vitro | Modulated PI3K/AKT/mTOR, , NF-κB, PARP-1, Bcl-2 | Reduced cancer cell growth by 90% | [152] |

| Helicteres isora L. | DCM-E/HeE | Rosmarinic Acid | Anti-inflammatory, Antioxidant | ELISA assays | In vitro | Differentiation in cancer cells and showed no cytotoxic effect at high levels | Reduced TNF-α, PGE-2, and NO levels; highest COX-2 inhibition | [154] |

| Waltheria indica L. | Roots and aerial parts/ CH2Cl2 extract | Flavonoids | Anti-inflammatory, Cancer chemoprevention | NF-κB inhibition, luciferase reporter assay, QR inducing assay | In vitro | Induce Phase 2 enzyme activity via QR induction assay | Of 29 compounds in the study, 7 showed inhibitory activity on the NF-κB pathway | [178] |

| Commiphora leptophloeos L. | Hydroalcoholic leaf extract | Phenolic acids and flavonoids | Anti-inflammatory | NO radical inhibition analysis, qPCR, physicochemical tests | In vitro/ In vivo | Downregulates NF-κB, COX-2, reduces cytokines | Reduces inflammatory markers, promising for inflammatory bowel disease | [153] |

| Matricaria chamomilla L. | ns. | β-Amyrin, β-Eudesmol, β-Sitosterol, Apigenin, Lupeol, Quercetin, Myricetin | Anti-inflammatory, anticancer | Proteome analysis, WB, Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR, Thermophoresis | In silico/ In vitro | Inhibition of NF-κB pathway, reduction of IL-1β, IL6 mRNA expression, and G2/M cell cycle arrest | NF-κB inhibition, potential cancer prevention, reduced proinflammatory cytokine expression | [156] |

| Asparagusdensiflorus meyeri L. | Root and aerial parts/ DCM-E | Saponins, glycosides, sterols, triterpenes | Cytotoxic, anti-inflammatory | MTT assay, MCF-7 cell stimulation using TNF—α, RT-PRC | In vitro | Reduces NO release and NF-κB gene expression | Significant cytotoxicity (IC50 26.13 μg/ml) | [179] |

| Capparis cartilaginea L. | Ethanolic leaf extract | Alkaloids, flavonoids, phenols, fatty acids, carotenes | Antioxidant, cytotoxic, anti-inflammatory | FBRC, FRAP, MTT assay, COX-1 inhibition | In vitro | Dose-dependent inhibition of thermally induced protein denaturation | Anti-inflammatory (IC50 60.23 and 17.67 µg/mL) better than standards | [180] |

| Corchorus olitorius L. | Hydroethanolic leaf extract | Tannins, flavonoids, phenolics, terpenoids, cardiac glycosides | Pro-estrogenic, anti-inflammatory | Phytochemical and ELISA analyses | In vivo | Lowers IL-6 and inhibits proliferation by binding phytoestrogens to ER-β | Strong antioxidative potential due to its high tannin content. | [181] |

| Amaranthus hybridus L. | Tannins, flavonoids, phenolics, cardiac glycosides, coumarins | Reduction in tumor size and incidence | ||||||

| Euphorbia hirta L. | Whole extract | Phytol, fatty acids and 5-HMF | Anti-inflammatory | NO Production | In vitro | Suppression of PG generation | Inhibition of iNOS directly involved in inflammation | [157] |

| Antidiabetic activity | ||||||||

| Tradescantia pallida L. | Leave extract | Syringic acid, p-coumaric acid, morin, and catechin | Glycosylation and hemoglobin activity | α-amylase assay | In vitro | Glycosylation inhibition non-enzymatically | Boosts insulin production, revitalizes β-cells, inhibits AGEs, stimulates glucose transporters and AMPK | [182] |

| Cissampelos capensis L. | Leaf, stem, and rhizome | Glaziovine, Pronuciferine and, cissamanine | Antihyperglycemic | α-amylase assay | In vitro | Enzyme inhibition pathway | Reduction of glucose levels | [183] |

| Phyllanthus emblica L. | ns. | Flavonoids | Antihyperglycemic | Molecular docking assay | In silico | Hypoglycemic action, reduction of relative risk of T2D, and PPAR inhibition of T2D | High binding affinity and selectivity for T2D therapeutic targets | [184] |

| Ocinum sanctum L. | Leaves | Eugenol | Antihyperglycemic | ELISA, RIA, and Neutral Red assay | In vitro | Physiological pathway | Reductions in plasma glucose levels in T2D are associated with enhanced insulin secretion from pancreatic islets, perfused pancreas | [185] |

| Ocinum basilicum L. | Leaves | TPC and FC | Antihyperglycemic | Enzyme inhibitory activity assay | In vitro | Enzymes inhibition pathway (α-glucosidase, α-amylase, DPP-IV, PTP1B, and SGLT2) | Inhibition of intestinal sucrase, maltase, and porcine pancreatic α-amylase | [186] |

| Derris elliptica L. | Leaves | QUE and ceramide | Antihyperglycemic | Biochemical analysis and histopathology study | In vivo | Enzymes inhibition pathway | Increase insulin secretion, protect pancreatic β–cells from oxidative stress | [159] |

| Carica papaya L. | Seeds | Hexadecanoic acid Methyl ester, 11-ODA Oleic acid | Antihyperglycemic | α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibition assay | In vitro | Enzymes inhibition pathway | Reduction of glucose levels | [187] |

| Rhazya stricta L. | Root | Hexadecanoic acid, Methyl ester | Antihyperlipidemic activity and hepatoprotective effect | DPP-IV, α-amylase, α-secretase inhibition assay, GLP-1 measurement | In vitro/ in vivo | Enzymes inhibition pathway | Reduce blood glucose and HbA1c, reduce cholesterol and triglyceride levels, reduce liver enzyme activity | [188] |

| Halooxylon stocksii L. | Root and aerial parts | 8-ODA Methyl ester | Antidiabetic | α-amylase and α-glucosidase assay | In vitro | Enzymes inhibition pathway | Reduction of glucose levels | [189] |

| Antiobesity activity | ||||||||

| Rosa centifolia L. | Petals | Ellagic acid (polyphenols) | Lipid metabolism improvement | PCR | In vivo | Suppression of lipid synthesis, Inhibition of intestinal absorption, Downregulation of Scd1 and Hmcgr mRNAs in the liver | Reduced body weight and adipose tissue, increased fecal triglycerides, improved lipid, and cholesterol metabolism | [161] |

| Rheum rhabarbarum L. | ns. | Emodin, rhein (anthraquinones) | Lipid lowering | ELISA assay and histological evaluation | In vitro/ in vivo | FAS and ACC production was prevented through decreased PPARγ and C/EBPα expression, leading to a reduction in lipid accumulation | Body weight and adipose tissue reduction | [166] |

| Brassica juncea L. | ns. | Sinigrin (glucosinolate) | Anti-obesity | Cell Culture and XTT Assay, WB, Histological Analysis | In vitro/ in vivo | Reduce expression of adipogenic and lipid synthesis proteins | Inhibition of lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 and decrease eWAT mass in obese mice fed a high-fat diet | [165] |

| Anthophycus longifolius L. | ns. | Rhodomycinone, salsolinol, 5-HCO, 2-COS, demethylalangiside | Anti-obesity and Anti-hyperglycemia | α-amylase, α-glucosidase, and pancreatic lipase assay | In vitro | Enzymes inhibition pathway | Delay lipid and CH digestion and absorption | [167] |

| Solanum xanthocarpum L. | Fresh and dry leaves | Solasodine, Carpesterol, β-Sitosterol, Diosgenin | Hypoglycemic, hepatoprotective hypotensive | Pancreatic Lipase Inhibition Assay and MTT | In vitro | ns. | At 62.5 µg/mL, the fresh leaf extract reduced cancer cell viability by 50% | [164] |

| Rumex rothschildianus L. | Acetone fraction | Flavonoids, phenolics | Anti-α-amylase, anti-α-glucosidase, anti-lipase | Lipase inhibition activity | In vitro | Inhibits OS, α-amylase, α-glucosidase, and lipase | Strong lipase inhibition (acetone fraction IC50 26.3 μg/ml), close to orlistat (IC50 12.3 μg/ml) | [168] |

| Neuroprotective activity | ||||||||

| Paeonia ostii | Stamen | (+)-3′′-methoxy-oxylactiflorin | Anti-inflammatory | Molecular docking and NO inhibition assay | In vitro/ in silico | Inhibition of NO production by binding with protein COX-2 | NO production reduced to values of EC50 3.02 μM | [171] |

| Phyllanthus emblica | Fruit extract | ns. | Anti-inflammatory | NO inhibition assay | In vivo | Reduction of pro-inflammatory markers IL-1β and TNF-α and up-regulation of expression of up-regulated 5-HT1D, 5-HT2A, and D2 receptor proteins | Amelioration of social interaction, social affiliation, anxiety, and motor coordination | [172] |

| Tabebuia impetiginosa | Leaves | Iridoids and organic acids | Anti-inflammatory | AChE inhibitory activity, LA detection, Y-maze test, PA assay | In vitro/ in vivo | Attenuation of cognitive impairment induced by CP supported by its effect on rats’ performance in Y-maze and PA tests | Reduction of CP-induced chemo brain and restoration of normal hippocampal function | [173] |

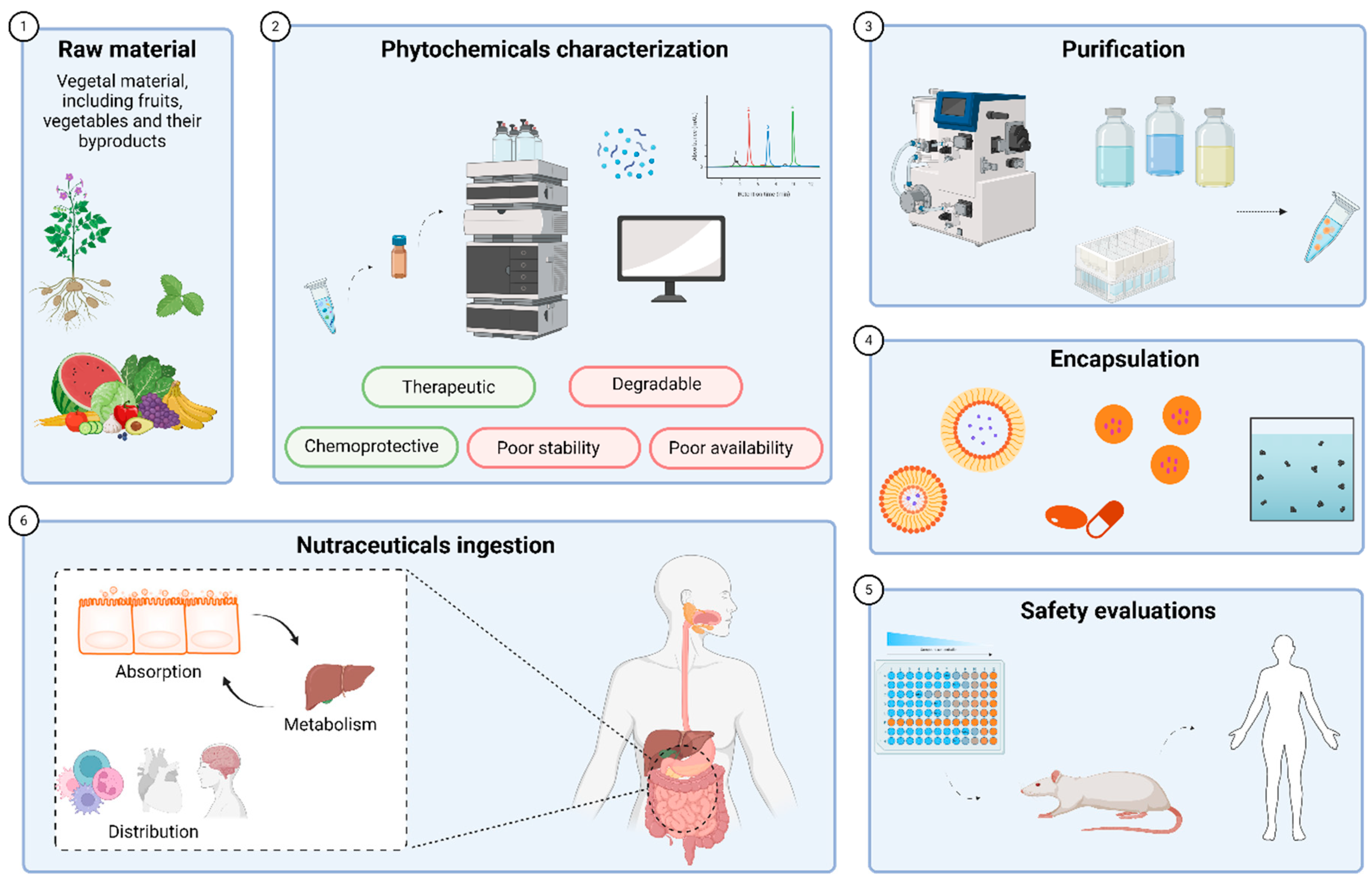

4. Development of Phytochemicals as Nutraceuticals

4.1. Extraction, Purification and Encapsulation

4.2. Considerations of Bioavailability

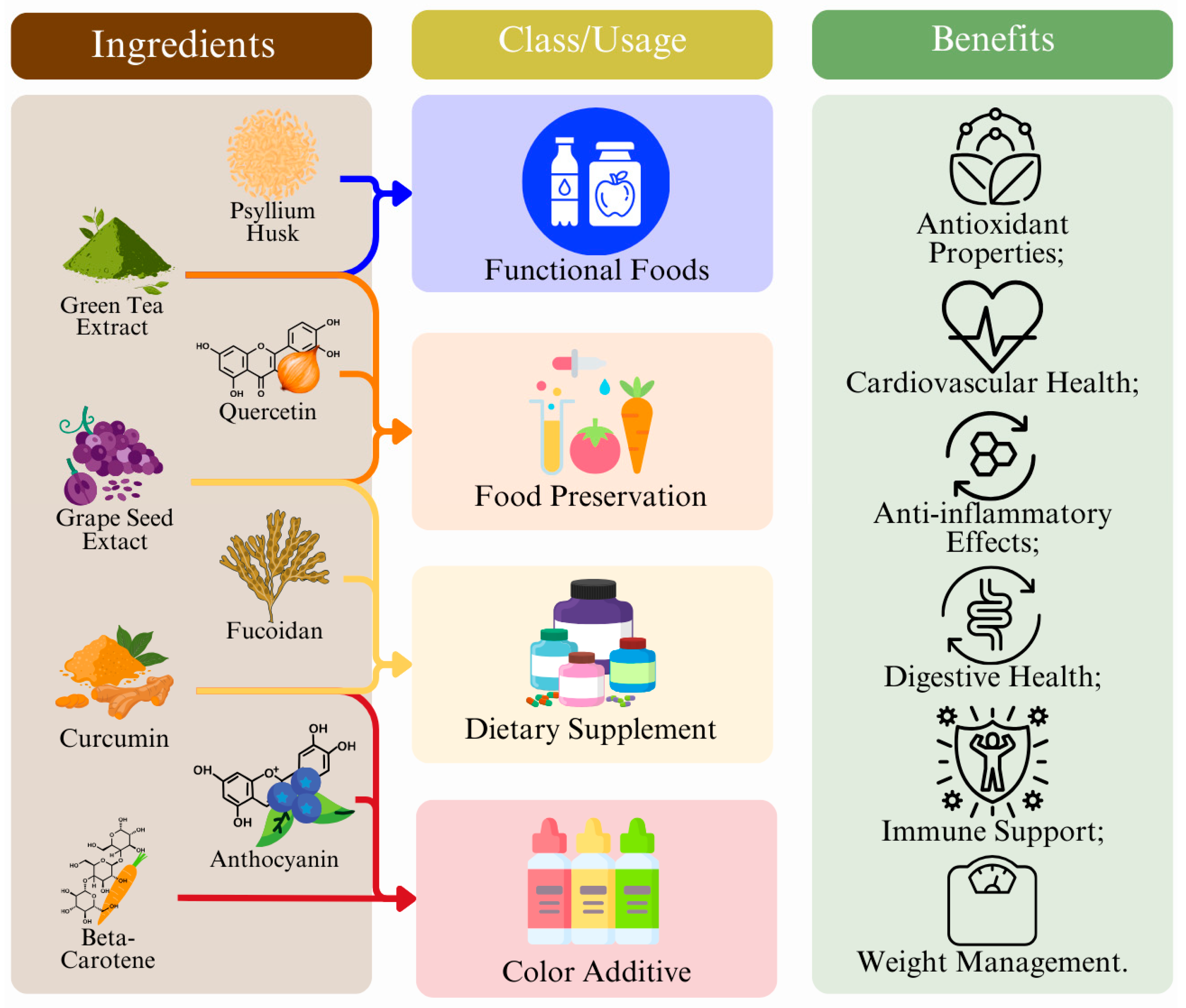

5. Current Applications of Nutraceuticals

5.1. Ingredients of Functional Foods

5.2. Isolated Phytochemicals as Nutraceuticals

| Nutraceutical | Source | Applications | Functionality | Health Benefits | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pectin | Fruits (Apple, citrus…) | Jams, jellies, dairy products | Gelling agent, thickener | Anti-cancer, immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, cholesterol-lowering (…) | [252] |

| Inulin | Chicory root | Low-fat foods, fiber supplements | Prebiotic, fat replacer | Gut-microbiota regulating, lipid metabolism regulating, mineral absorption enhancing, anti-inflammatory (…) | [253] |

| Cellulose | Several plants | Low-fat foods, plant-based meats, bakery products | Stabilizer, thickener | Gut-microbiota regulating, cholesterol reducing, blood glucose levels regulating, anti-inflammatory (…) | [234] |

| Wheat Bran | Wheat | Cereals, bread and bakery products | Texture enhancer, fiber source | Gut-microbiota regulating, cancer-risk reducing, cardioprotective (…) | [254] |

| Psyllium husk | Plantago ovata seeds | Fiber supplement, cereals | Fiber source, thickener | Anti-diabetic, reduces cholesterol levels, and aids in gastrointestinal health (…) | [255,256] |

| Green tea extract and catechins | Green tea leaves | Beverages, supplements, snacks | Antioxidant, antimicrobial | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, antiobesity (…) | [257,258] |

| Grapeseed extract | Grape seeds | Beverages, supplements | Antioxidant, antimicrobial | Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, cardioprotective, antimicrobial, anti-cancer (…) | [259] |

| β-carotene | Carrots, sweet potatoes | Supplements, snacks, beverages, candies | Natural colorant, antioxidant | Antioxidant, supports immune function (…) | [260] |

| Anthocyanins | Berries, red cabbage | Supplements, snacks, beverages, candies | Natural colorant, antioxidant | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, anti-obesity (…) | [261] |

| Betanins | Beetroot | Supplements, snacks, beverages, candies | Natural colorant, antioxidant | Antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, potential anticancer benefits (…) | [243] |

| Curcumin | Turmeric root | Supplements, snacks, beverages, candies | Natural colorant, antioxidant | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and immune-regulatory properties (…) | [262] |

| Resveratrol | Grapes, red wine | Beverages, supplements | Antioxidant, antimicrobial | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, cardioprotective (…) | [263] |

| Fucoidans | Blown algae | Supplements, fortified foods | Gelling agents, thickeners | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticoagulant, antitumor, antiviral (…) | [264] |

| Agar | Red algae | Jellies, jams, candy, plant-based gelatin | Gelling agent, texture enhancer | Antioxidant, antiviral, antibacterial, prebiotic, anti-tumor (…) | [265] |

| Carrageenan | Red algae | Jellies, jams, candy, plant-based gelatin | Thickener, gelling agent | Cardioprotective, anticancer, antiviral, anticoagulant, antioxidant (…) | [266] |

| Quercetin | Onions, apple peels | Supplements, fortified foods | Antioxidant, preservative | Anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anticancer, cardioprotective (…) | [267,268] |

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carpena, M.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Pereira, A.G.; Soria-Lopez, A.; Chamorro, F.; Collazo, N.; Jarboui, A.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Prieto, M.A. Plant Antioxidants from Agricultural Waste: Synergistic Potential with Other Biological Properties and Possible Applications. In Plant Antioxidants and Health; Ekiert, H.M., Ramawat, K.G., Arora, J., Eds.; Springer, Cham, 2021; pp. 1–38 ISBN 9783030452995.

- Shahidi, F.; Ambigaipalan, P. Phenolics and Polyphenolics in Foods, Beverages and Spices: Antioxidant Activity and Health Effects - A Review. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 18, 820–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-J.; Gan, R.-Y.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; Li, A.-N.; Xu, D.-P.; Li, H.-B. Antioxidant Phytochemicals for the Prevention and Treatment of Chronic Diseases. Molecules 2015, 20, 21138–21156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allaqaband, S.; Dar, A.H.; Patel, U.; Kumar, N.; Nayik, G.A.; Khan, S.A.; Ansari, M.J.; Alabdallah, N.M.; Kumar, P.; Pandey, V.K.; et al. Utilization of Fruit Seed-Based Bioactive Compounds for Formulating the Nutraceuticals and Functional Food: A Review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knothe, G. Vegetable Oils. In Handbook of Bioenergy Crop Plants; Wiley, 2012; pp. 793–810 ISBN 9781439816851.

- Chouaibi, M.; Rezig, L.; Hamdi, S.; Ferrari, G. Chemical Characteristics and Compositions of Red Pepper Seed Oils Extracted by Different Methods. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 128, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Lomillo, J.; González-SanJosé, M.L. Applications of Wine Pomace in the Food Industry: Approaches and Functions. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Li, H.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, H. A State-of-the-Art Review on the Synthetic Mechanisms, Production Technologies, and Practical Application of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids from Microalgae. Algal Res. 2021, 55, 102281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, G.L.; Moccia, S.; Russo, M.; Spagnuolo, C. Redox Regulation by Carotenoids: Evidence and Conflicts for Their Application in Cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 194, 114838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, T. Provitamin a Carotenoids: Occurrence, Intake and Bioavailability. Food Nutr. Components Focus 2012, 1, 142–161. [Google Scholar]

- Poojary, M.M.; Barba, F.J.; Aliakbarian, B.; Donsì, F.; Pataro, G.; Dias, D.A.; Juliano, P. Innovative Alternative Technologies to Extract Carotenoids from Microalgae and Seaweeds. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Concepcion, M.; Avalos, J.; Bonet, M.L.; Boronat, A.; Gomez-Gomez, L.; Hornero-Mendez, D.; Limon, M.C.; Meléndez-Martínez, A.J.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Palou, A.; et al. A Global Perspective on Carotenoids: Metabolism, Biotechnology, and Benefits for Nutrition and Health. Prog. Lipid Res. 2018, 70, 62–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Q.; Hu, J.; Gao, H.; Li, M.; Sun, Y.; Chen, H.; Zuo, S.; Fang, Q.; Huang, X.; Yin, J.; et al. Bioactive Dietary Fibers Selectively Promote Gut Microbiota to Exert Antidiabetic Effects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 7000–7015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baiano, A. Recovery of Biomolecules from Food Wastes - A Review. Molecules 2014, 19, 14821–14842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, F.; Pasha, I.; Arshad, M.U.; Muhammad Anjum, F.; Hussain, S.; Rasheed, R.; Nasir, M.A.; Shafique, B. Physiological and Nutraceutical Perspectives of Fructan. Int. J. Food Prop. 2015, 18, 1895–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Fraga-Corral, M.; Carpena, M.; García-Oliveira, P.; Echave, J.; Pereira, A.G.; Lourenço-Lopes, C.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Agriculture Waste Valorisation as a Source of Antioxidant Phenolic Compounds within a Circular and Sustainable Bioeconomy. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 4853–4877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barjoveanu, G.; Pătrăuțanu, O.-A.; Teodosiu, C.; Volf, I. Life Cycle Assessment of Polyphenols Extraction Processes from Waste Biomass. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, Y.; Smolke, C.D. Strategies for Microbial Synthesis of High-Value Phytochemicals. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguengo, L.M.; Salgaço, M.K.; Sivieri, K.; Maróstica Júnior, M.R. Agro-Industrial by-Products: Valuable Sources of Bioactive Compounds. Food Res. Int. 2022, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, P.A. Fatty Acids: Metabolism. In Encyclopedia of Human Nutrition; Elsevier, 2013; Vol. 2–4, pp. 220–230 ISBN 9780123848857.

- Moghadasian, M.H.; Shahidi, F. Fatty Acids. In International Encyclopedia of Public Health; Elsevier, 2016; Vol. 3, pp. 114–122 ISBN 9780128037089.

- He, M.; Ding, N.Z. Plant Unsaturated Fatty Acids: Multiple Roles in Stress Response. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoka, T. Carotenoids as Natural Functional Pigments. J. Nat. Med. 2020, 74, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crupi, P.; Faienza, M.F.; Naeem, M.Y.; Corbo, F.; Clodoveo, M.L.; Muraglia, M. Overview of the Potential Beneficial Effects of Carotenoids on Consumer Health and Well-Being. Antioxidants 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshminarayana, R.; Paul, B. Free Radical Chemistry of Carotenoids and Oxidative Stress Physiology of Cancer. In Handbook of Oxidative Stress in Cancer: Therapeutic Aspects: Volume 1; Chakraborti, S., Ed.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2022; Vol. 1, pp. 3077–3097. ISBN 9789811654220. [Google Scholar]

- Genç, Y.; Bardakci, H.; Yücel, Ç.; Karatoprak, G.Ş.; Akkol, E.K.; Barak, T.H.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E. Oxidative Stress and Marine Carotenoids: Application by Using Nanoformulations. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R. Physicochemical, Antioxidant Properties of Carotenoids and Its Optoelectronic and Interaction Studies with Chlorophyll Pigments. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.K.; Prasad, P.; Lokesh, V.; Shang, X.; Shin, J.; Keum, Y.S.; Lee, J.H. Carotenoids: Dietary Sources, Extraction, Encapsulation, Bioavailability, and Health Benefits—A Review of Recent Advancements. Antioxidants 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.G.; Otero, P.; Echave, J.; Carreira-Casais, A.; Chamorro, F.; Collazo, N.; Jaboui, A.; Lourenço-Lopes, C.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Prieto, M.A. Xanthophylls from the Sea: Algae as Source of Bioactive Carotenoids. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widomska, J.; Zareba, M.; Subczynski, W.K. Can Xanthophyll-Membrane Interactions Explain Their Selective Presence in the Retina and Brain? Foods 2016, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojulari, O.V.; Gi Lee, S.; Nam, J.O. Therapeutic Effect of Seaweed Derived Xanthophyl Carotenoid on Obesity Management; Overview of the Last Decade. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürbüz, M.; Aktaç, Ş. Understanding the Role of Vitamin A and Its Precursors in the Immune System. Nutr. Clin. Metab. 2022, 36, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebadi, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Pezeshki, A.; Jafari, S.M. Health Benefits of Beta-Carotene. In Handbook of Food Bioactive Ingredients; Jafari, S.M., Rashidinejad, A., Simal-Gandara, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; ISBN 978-3-030-81404-5. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, E.; Batool, R.; Akhtar, W.; Rehman, S.; Shahzad, T.; Malik, A.; Shariati, M.A.; Laishevtcev, A.; Plygun, S.; Heydari, M.; et al. Xanthophyll: Health Benefits and Therapeutic Insights. Life Sci. 2020, 240, 117104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Omer, K. Recent Advancement in Therapeutic Activity of Carotenoids. In Dietary Carotenoids; Rao, A.V., Rao, L., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Grune, T.; Lietz, G.; Palou, A.; Ross, A.C.; Stahl, W.; Tang, G.; Thurnham, D.; Yin, S.A.; Biesalski, H.K. β-Carotene Is an Important Vitamin A Source for Humans. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 2268S–2285S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.J.; Fehrenbach, G.W.; Abidin, I.Z.; Buckley, C.; Montgomery, T.; Pogue, R.; Murray, P.; Major, I.; Rezoagli, E. Polysaccharides—Naturally Occurring Immune Modulators. Polymers (Basel). 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, L. de F.; de Vos, P.; Fabi, J.P. Nature’s Soothing Solution: Harnessing the Potential of Food-Derived Polysaccharides to Control Inflammation. Curr. Res. Struct. Biol. 2023, 6, 100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baghel, R.S.; Choudhary, B.; Pandey, S.; Pathak, P.K.; Patel, M.K.; Mishra, A. Rehashing Our Insight of Seaweeds as a Potential Source of Foods, Nutraceuticals, and Pharmaceuticals. Foods 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F. Sen; Yao, Y.F.; Wang, L.F.; Li, W.J. Polysaccharides as Antioxidants and Prooxidants in Managing the Double-Edged Sword of Reactive Oxygen Species. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 159, 114221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G. peng; Wu, D. sheng; Xiao, X. wei; Huang, Q. yun; Chen, H. bin; Liu, D.; Fu, H. qing; Chen, X. hua; Zhao, C. Structural Characterization and Antioxidant Effect of Green Alga Enteromorpha Prolifera Polysaccharide in Caenorhabditis Elegans via Modulation of MicroRNAs. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 150, 1084–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, M.; Hu, C.; Liu, A.; Chen, J.; Gu, C.; Zhang, X.; You, C.; Tong, H.; Wu, M.; et al. Sargassum Fusiforme Fucoidan SP2 Extends the Lifespan of Drosophila Melanogaster by Upregulating the Nrf2-Mediated Antioxidant Signaling Pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Wu, S.; Shang, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, M.; Li, F.; Wang, C. Pleurotus Nebrodensis Polysaccharide(PN50G) Evokes A549 Cell Apoptosis by the ROS/AMPK/PI3K/AKT/MTOR Pathway to Suppress Tumor Growth. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 1616–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hu, S.; Nie, S.; Yu, Q.; Xie, M. Reviews on Mechanisms of in Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Polysaccharides. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 5692852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, N.; Sarmah, M.; Khatun, B.; Maji, T.K. Encapsulation of Active Ingredients in Polysaccharide–Protein Complex Coacervates. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 239, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, X. A Critical Review of the Abilities, Determinants, and Possible Molecular Mechanisms of Seaweed Polysaccharides Antioxidants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Jiang, T.; Xu, J.; Xi, W.; Shang, E.; Xiao, P.; Duan, J. ao The Relationship between Polysaccharide Structure and Its Antioxidant Activity Needs to Be Systematically Elucidated. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 270, 132391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.A.R.; Coimbra, M.A. The Antioxidant Activity of Polysaccharides: A Structure-Function Relationship Overview. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 314, 120965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, L.; Xu, D.; Zhou, Y.M.; Zhang, Y.B.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.B.; Cui, Y.L. Antioxidant Activities of Natural Polysaccharides and Their Derivatives for Biomedical and Medicinal Applications. Antioxidants 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niyigaba, T.; Liu, D.; Habimana, J. de D. The Extraction, Functionalities and Applications of Plant Polysaccharides in Fermented Foods: A Review. Foods 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheibani, E.; Hosseini, A.; Sobhani Nasab, A.; Adib, K.; Ganjali, M.R.; Pourmortazavi, S.M.; Ahmadi, F.; Marzi Khosrowshahi, E.; Mirsadeghi, S.; Rahimi-Nasrabadi, M.; et al. Application of Polysaccharide Biopolymers as Natural Adsorbent in Sample Preparation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 2626–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.; Qin, P.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X.; Yao, Y.; Ren, G. Structural Characterization and Antioxidant Activity of Alkali-Extracted Polysaccharides from Quinoa. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 113, 106392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, P.P.; Nayak, R.; Patra, S.; Abdulabbas, H.S.; Jena, M.; Pradhan, B. Seaweed-Derived Sulfated Polysaccharides; The New Age Chemopreventives: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers (Basel). 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Bharadvaja, N. Potential Benefits of Nutraceuticals for Oxidative Stress Management. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2022, 32, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, K.M.; Ramos-Lopez, O.; Pérusse, L.; Kato, H.; Ordovas, J.M.; Martínez, J.A. Precision Nutrition: A Review of Current Approaches and Future Endeavors. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 128, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, R. Chemistry and Biochemistry of Dietary Polyphenols. Nutrients 2010, 2, 1231–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Pereira, A.G.; Lourenço-Lopes, C.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Cassani, L.; Fraga-Corral, M.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Main Bioactive Phenolic Compounds in Marine Algae and Their Mechanisms of Action Supporting Potential Health Benefits. Food Chem. 2021, 341, 128262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, C.; Colombo, F.; Biella, S.; Stockley, C.; Restani, P. Polyphenols and Human Health: The Role of Bioavailability. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Shen, T.; Lou, H. Dietary Polyphenols and Their Biological Significance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2007, 8, 950–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Sang, S.; McClements, D.J.; Chen, L.; Long, J.; Jiao, A.; Jin, Z.; Qiu, C. Polyphenols as Plant-Based Nutraceuticals: Health Effects, Encapsulation, Nano-Delivery, and Application. Foods 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haminiuk, C.W.I.; Maciel, G.M.; Plata-Oviedo, M.S.V.; Peralta, R.M. Phenolic Compounds in Fruits - an Overview. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 47, 2023–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeriglio, A.; Barreca, D.; Bellocco, E.; Trombetta, D. Proanthocyanidins and Hydrolysable Tannins: Occurrence, Dietary Intake and Pharmacological Effects. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1244–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashmi, H.B.; Negi, P.S. Phenolic Acids from Vegetables: A Review on Processing Stability and Health Benefits. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caleja, C.; Ribeiro, A.; Barreiro, M.F.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Phenolic Compounds as Nutraceuticals or Functional Food Ingredients. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017, 23, 2787–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuolo, M.M.; Lima, V.S.; Maróstica Junior, M.R. Phenolic Compounds. In Bioactive Compounds: Health Benefits and Potential Applications; Campos, M.R.S., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; ISBN 9780128147740. [Google Scholar]

- Sorrenti, V.; Burò, I.; Consoli, V.; Vanella, L. Recent Advances in Health Benefits of Bioactive Compounds from Food Wastes and By-Products: Biochemical Aspects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.K.; Weng, M.S. Flavonoids as Nutraceuticals. Sci. Flavonoids 2006, 7, 213–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, M.; Romaní-Pérez, M.; Romaní, A.; de la Cruz, A.; Pastrana, L.; Fuciños, P.; Amado, I.R. Recent Technological Advances in Phenolic Compounds Recovery and Applications: Source of Nutraceuticals for the Management of Diabetes. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Rahaman, M.S.; Islam, M.R.; Rahman, F.; Mithi, F.M.; Alqahtani, T.; Almikhlafi, M.A.; Alghamdi, S.Q.; Alruwaili, A.S.; Hossain, M.S.; et al. Role of Phenolic Compounds in Human Disease: Current Knowledge and Future Prospects. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignesh, A.; Amal, T.C.; Sarvalingam, A.; Vasanth, K. A Review on the Influence of Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods on Health. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 5, 100749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhazi, L.; Depeint, F.; Gotor, A.A. Loss in the Intrinsic Quality and the Antioxidant Activity of Sunflower (Helianthus Annuus L.) Oil during an Industrial Refining Process. Molecules 2022, 27, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambra, R.; Natella, F.; Lucchetti, S.; Forte, V.; Pastore, G. α-Tocopherol, β-Carotene, Lutein, Squalene and Secoiridoids in Seven Monocultivar Italian Extra-Virgin Olive Oils. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 68, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagali, N.; Catalá, A. Antioxidant Activity of Conjugated Linoleic Acid Isomers, Linoleic Acid and Its Methyl Ester Determined by Photoemission and DPPH Techniques. Biophys. Chem. 2008, 137, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinska, A.; Zebrowski, J.; Duda, M.; Gorka, A.; Wnuk, M. Fatty Acid Profile and Biological Activities of Linseed and Rapeseed Oils. Molecules 2015, 20, 22872–22880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulatt, C.J.; Wijffels, R.H.; Bolla, S.; Kiron, V. Production of Fatty Acids and Protein by Nannochloropsis in Flat-Plate Photobioreactors. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0170440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Li, Y.; Lin, Y.; Lin, J.; Zhang, L.; Wu, D.; Zeng, J.; Li, J.; Liu, J. wen; Li, G. Eicosapentaenoic Acid (EPA) Exhibits Antioxidant Activity via Mitochondrial Modulation. Food Chem. 2022, 373, 131389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, Y.; Xiao, B.; Cui, D.; Lin, Y.; Zeng, J.; Li, J.; Cao, M.-J.; Liu, J. Antioxidant Activity of Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) and Its Regulatory Roles in Mitochondria. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 1647–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Meng, T.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z.; Shi, Y.; Ling, X.; Luo, W.; Liang, D.; et al. Functions of PKS Genes in Lipid Synthesis of Schizochytrium Sp. by Gene Disruption and Metabolomics Analysis. Mar. Biotechnol. 2018, 20, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, N.; Casal, S.; Pinho, T.; Cruz, R.; Peres, A.M.; Baptista, P.; Pereira, J.A. Fatty Acid Composition from Olive Oils of Portuguese Centenarian Trees Is Highly Dependent on Olive Cultivar and Crop Year. Foods 2021, 10, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petraru, A.; Ursachi, F.; Amariei, S. Nutritional Characteristics Assessment of Sunflower Seeds, Oil and Cake. Perspective of Using Sunflower Oilcakes as a Functional Ingredient. Plants 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Y.M.; Kadir, A.A.; Ahmad, Z.; Yaakub, H.; Zakaria, Z.A.; Hakim Abdullah, M.N. Free Radical Scavenging Activity of Conjugated Linoleic Acid as Single or Mixed Isomers. Pharm. Biol. 2012, 50, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Cheng, W.; Liu, T. Heterotrophy of Filamentous Oleaginous Microalgae Tribonema Minus for Potential Production of Lipid and Palmitoleic Acid. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 239, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, T.H.; Pereira, J.A.; Cabrera-Vique, C.; Lara, L.; Oliveira, A.F.; Seiquer, I. Characterization of Arbequina Virgin Olive Oils Produced in Different Regions of Brazil and Spain: Physicochemical Properties, Oxidative Stability and Fatty Acid Profile. Food Chem. 2017, 215, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Fitzgerald, M.; Topp, B.; Alam, M.; O’Hare, T.J. A Review of Biological Functions, Health Benefits, and Possible de Novo Biosynthetic Pathway of Palmitoleic Acid in Macadamia Nuts. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, D.; Freije, A.; Abdulhussain, H.; Khonji, A.; Hasan, M.; Ferraris, C.; Gasparri, C.; Aziz Aljar, M.A.; Ali Redha, A.; Giacosa, A.; et al. Analysis of the Antioxidant Activity, Lipid Profile, and Minerals of the Skin and Seed of Hazelnuts (Corylus Avellana L.), Pistachios (Pistacia Vera) and Almonds (Prunus Dulcis)—A Comparative Analysis. AppliedChem 2023, 3, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, X.; Dai, T.; Chen, M.; Liang, R.; Du, L.; Chen, J.; Liu, C. Comparative Study of Chemical Compositions and Antioxidant Capacities of Oils Obtained from 15 Macadamia (Macadamia Integrifolia) Cultivars in China. Foods 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górnaś, P.; Rudzińska, M.; Grygier, A.; Lācis, G. Diversity of Oil Yield, Fatty Acids, Tocopherols, Tocotrienols, and Sterols in the Seeds of 19 Interspecific Grapes Crosses. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 2078–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, G.E.; Momin, R.A.; Nair, M.G.; Dewitt, D.L. Antioxidant and Cyclooxygenase Activities of Fatty Acids Found in Food. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 2231–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Sun, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, D.; Nie, F.; Gooneratne, R. Oleic Acid Alleviates Cadmium-Induced Oxidative Damage in Rat by Its Radicals Scavenging Activity. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2019, 190, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xavier, A.A.O.; Pérez-Gálvez, A. Carotenoids as a Source of Antioxidants in the Diet. In Sub-Cellular Biochemistry; Stange, C., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; Vol. 79, pp. 359–375. ISBN 978-3-319-39126-7. [Google Scholar]

- Koca Bozalan, N.; Karadeniz, F. Carotenoid Profile, Total Phenolic Content, and Antioxidant Activity of Carrots. Int. J. Food Prop. 2011, 14, 1060–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço-Lopes, C.; Fraga-Corral, M.; Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Carpena, M.; Pereira, A.G.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; 57,92, M. A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Biological Action Mechanisms of Fucoxanthin Extracted from Algae for Application in Food and Cosmetic Industries. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 117, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambati, R.R.; Moi, P.S.; Ravi, S.; Aswathanarayana, R.G. Astaxanthin: Sources, Extraction, Stability, Biological Activities and Its Commercial Applications - A Review. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, H.; Soccol, C.R.; Molina-Aulestia, D.T.; Cardoso, J.; de Melo Pereira, G.V.; de Souza Vandenberghe, L.P.; Manzoki, M.C.; Ambati, R.R.; Ravishankar, G.A.; de Carvalho, J.C. Lutein from Microalgae: An Industrial Perspective of Its Production, Downstream Processing, and Market. Fermentation 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, C.; Pintea, A. A Brief Overview of Dietary Zeaxanthin Occurrence and Bioaccessibility. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burri, B.J.; La Frano, M.R.; Zhu, C. Absorption, Metabolism, and Functions of β-Cryptoxanthin. Nutr. Rev. 2016, 74, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahma, D.; Dutta, D. Evaluating β-Cryptoxanthin Antioxidant Properties against ROS-Induced Macromolecular Damages and Determining Its Photo-Stability and in-Vitro SPF. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 39, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galla, R.; Ruga, S.; Aprile, S.; Ferrari, S.; Brovero, A.; Grosa, G.; Molinari, C.; Uberti, F. New Hyaluronic Acid from Plant Origin to Improve Joint Protection—An In Vitro Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.A.; Niamah, A.K. Identification and Antioxidant Activity of Hyaluronic Acid Extracted from Local Isolates of Streptococcus Thermophilus. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 60, 1523–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiraldi, C.; Cimini, D.; De Rosa, M. Production of Chondroitin Sulfate and Chondroitin. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 87, 1209–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, G.M.; Avenoso, A.; Campo, S.; Ferlazzo, A.M.; Calatroni, A. Antioxidant Activity of Chondroitin Sulfate. In Advances in Pharmacology; Advances in Pharmacology; Academic Press, 2006; Vol. 53, pp. 417–431 ISBN 0120329557.

- Pavão, M.S.G.; Mourão, P.A.S. Challenges for Heparin Production: Artificial Synthesis or Alternative Natural Sources? Glycobiol. Insights 2012, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijak, M.; Saluk, J.; Szelenberger, R.; Nowak, P. Popular Naturally Occurring Antioxidants as Potential Anticoagulant Drugs. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2016, 257, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medlej, M.K.; Batoul, C.; Olleik, H.; Li, S.; Hijazi, A.; Nasser, G.; Maresca, M.; Pochat-Bohatier, C. Antioxidant Activity and Biocompatibility of Fructo-Polysaccharides Extracted from a Wild Species of Ornithogalum from Lebanon. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delattre, C.; Fenoradosoa, T.A.; Michaud, P. Galactans: An Overview of Their Most Important Sourcing and Applications as Natural Polysaccharides. Brazilian Arch. Biol. Technol. 2011, 54, 1075–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P.; Malviya, R. Sources of Pectin, Extraction and Its Applications in Pharmaceutical Industry - an Overview. Indian J. Nat. Prod. Resour. 2011, 2, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wathoni, N.; Yuan Shan, C.; Yi Shan, W.; Rostinawati, T.; Indradi, R.B.; Pratiwi, R.; Muchtaridi, M. Characterization and Antioxidant Activity of Pectin from Indonesian Mangosteen (Garcinia Mangostana L.) Rind. Heliyon 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indrianingsih, A.W.; Rosyida, V.T.; Apriyana, W.; Hayati, S.N.; Darsih, C.; Nisa, K.; Ratih, D. Antioxidant and Antibacterial Properties of Bacterial Cellulose-Indonesian Plant Extract Composites for Mask Sheet. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 10, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabañas-Romero, L.V.; Valls, C.; Valenzuela, S. V.; Roncero, M.B.; Pastor, F.I.J.; Diaz, P.; Martínez, J. Bacterial Cellulose-Chitosan Paper with Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 1568–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, A.H.; Al Abboud, M.A.; Alawlaqi, M.M.; Abdelghany, T.M.; Hasanin, M. Synthesis of Nanocapsules Based on Biosynthesized Nickel Nanoparticles and Potato Starch: Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, and Anticancer Activity. Starch/Staerke 2022, 74, 2100165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulíková, D.; Kraic, J.Á.N. Natural Sources of Health-Promoting Starch Natural Sources of Health-Promoting Starch. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2018, 45, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Edgar, K.J. Properties, Chemistry, and Applications of the Bioactive Polysaccharide Curdlan. Biomacromolecules 2014, 15, 1079–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, S.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Ding, S.; Wang, R.; Fu, F.; Zhan, X. Curdlan-Polyphenol Complexes Prepared by PH-Driven Effectively Enhanced Their Physicochemical Stability, Antioxidant and Prebiotic Activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 267, 131579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareem, A.J.; Salman, J.A.S. Production of Dextran from Locally Lactobacillus Spp. Isolates. Reports Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 8, 278–286. [Google Scholar]

- Rosca, I.; Turin-Moleavin, I.A.; Sarghi, A.; Lungoci, A.L.; Varganici, C.D.; Petrovici, A.R.; Fifere, A.; Pinteala, M. Dextran Coated Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Loaded with Protocatechuic Acid as Multifunctional Therapeutic Agents. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 256, 128314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, R.; Farah, L.F. Production and Application of Microbial Cellulose. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1998, 59, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rop, O.; Mlcek, J.; Jurikova, T. Beta-Glucans in Higher Fungi and Their Health Effects. Nutr. Rev. 2009, 67, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mebrek, S.; Djeghim, H.; Mehdi, Y.; Meghezzi, A.; Anwar, S.; Ali Awadh, N.A.; Benali, M. Antioxidant, Anti-Cholinesterase, Anti-α-Glucosidase and Prebiotic Properties of Beta-Glucan Extracted from Algerian Barley. Int. J. Phytomedicine 2018, 10, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, T.; Khan, A.; Brown, D.; Dhayagude, N.; He, Z.; Ni, Y. Sources, Production and Commercial Applications of Fungal Chitosan: A Review. J. Bioresour. Bioprod. 2022, 7, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, R.; Yu, H.; Liu, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Z.; Li, P. Antioxidant Activity of Differently Regioselective Chitosan Sulfates in Vitro. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2005, 13, 1387–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha De Souza, M.C.; Marques, C.T.; Guerra Dore, C.M.; Ferreira Da Silva, F.R.; Oliveira Rocha, H.A.; Leite, E.L. Antioxidant Activities of Sulfated Polysaccharides from Brown and Red Seaweeds. J. Appl. Phycol. 2007, 19, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhein-Knudsen, N.; Reyes-Weiss, D.; Horn, S.J. Extraction of High Purity Fucoidans from Brown Seaweeds Using Cellulases and Alginate Lyases. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 229, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; COTAS, J. Alginates - Recent Uses of This Natural Polymer; IntechOpen: Rijeka, 2019; ISBN 978-1-78985-642-2. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheekh, M.; Kassem, W.M.A.; Alwaleed, E.A.; Saber, H. Optimization and Characterization of Brown Seaweed Alginate for Antioxidant, Anticancer, Antimicrobial, and Antiviral Properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, B.; Costa, S.M.; Costa, I.; Fangueiro, R.; Ferreira, D.P. The Potential of Algae as a Source of Cellulose and Its Derivatives for Biomedical Applications. Cellulose 2024, 31, 3353–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petchsomrit, A.; Chanthathamrongsiri, N.; Jiangseubchatveera, N.; Manmuan, S.; Leelakanok, N.; Plianwong, S.; Siranonthana, N.; Sirirak, T. Extraction, Antioxidant Activity, and Hydrogel Formulation of Marine Cladophora Glomerata. Algal Res. 2023, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Harthi, S.S.; Mavazhe, A.; Al Mahroqi, H.; Khan, S.A. Quantification of Phenolic Compounds, Evaluation of Physicochemical Properties and Antioxidant Activity of Four Date (Phoenix Dactylifera L.) Varieties of Oman. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2015, 10, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, M.G.S.; Cruz, L.T.; Bertges, F.S.; Húngaro, H.M.; Batista, L.R.; da Silva, S.S.; Fonseca, M.J.V.; Rodarte, M.P.; Vilela, F.M.P.; Amaral, M. da P.H. do Enhancement of Antioxidant Properties from Green Coffee as Promising Ingredient for Food and Cosmetic Industries. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 16, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, S.Y.; Sung, J.M.; Huang, P.W.; Lin, S.D. Antioxidant, Antidiabetic, and Antihypertensive Properties of Echinacea Purpurea Flower Extract and Caffeic Acid Derivatives Using in Vitro Models. J. Med. Food 2017, 20, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharat, N.N.; Rathod, V.K. Extraction of Ferulic Acid from Rice Bran Using NADES-Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction: Kinetics and Optimization. J. Food Process Eng. 2023, 46, e14158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero-Cruz, J.F.; Granados-Pineda, J.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Pérez-Rojas, J.M.; Kumar-Passari, A.; Diaz-Ruiz, G.; Rivero-Cruz, B.E. Phytochemical Constituents, Antioxidant, Cytotoxic, and Antimicrobial Activities of the Ethanolic Extract of Mexican Brown Propolis. Antioxidants 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Al-Ansari, M.; Al-Humaid, L.; Aldawsari, M.; Abid, I.F.; Jhanani, G.K.; Shanmuganathan, R. Quercetin Extraction from Small Onion Skin (Allium Cepa L. Var. Aggregatum Don.) and Its Antioxidant Activity. Environ. Res. 2023, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyandoko, D.; Widowati, W.; Kusuma, H.S.W.; Afifah, E.; Wijayanti, C.R.; Wahyuni, C.D.; Idris, A.M.; Putdayani, R.A.; Rizal, R. Antioxidant Activity of Green Tea Extract and Myricetin. In Proceedings of the InHeNce 2021 - 2021 IEEE International Conference on Health, Instrumentation and Measurement, and Natural Sciences; 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, X.; Zhou, Z.; Ren, R.; Xu, M. Apigenin, Flavonoid Component Isolated from Gentiana Veitchiorum Flower Suppresses the Oxidative Stress through LDLR-LCAT Signaling Pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akullo, J.O.; Kiage-Mokua, B.N.; Nakimbugwe, D.; Ng’ang’a, J.; Kinyuru, J. Phytochemical Profile and Antioxidant Activity of Various Solvent Extracts of Two Varieties of Ginger and Garlic. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antasionasti, I.; Datu, O.S.; Lestari, U.S.; Abdullah, S.S.; Jayanto, I. Correlation Analysis of Antioxidant Activities with Tannin, Total Flavonoid, and Total Phenolic Contents of Nutmeg (Myristica Fragrans Houtt) Fruit Precipitated by Egg White. Borneo J. Pharm. 2021, 4, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Montes, E.; Salamanca-Fernández, E.; Garcia-Villanova, B.; Sánchez, M.J. The Impact of Plant-Based Dietary Patterns on Cancer-Related Outcomes: A Rapid Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.M. , Darwish, Z.E., El Nouaem, M.I. et al. The Potential Preventive Effect of Dietary Phytochemicals In Vivo. Nature 2023, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, H.S.; Undie, D.A.; Okibe, G.; Ochepo, O.E.; Mahmud, F.; Ilumunter, M.M. Antioxidant and Phytochemical Classification of Medicinal Plants Used in the Treatment of Cancer Disease. J. Chem. Lett. 2024, 5, 108–119. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zhu, B.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, F.; Feng, J.; Jin, Y.; Sun, J.; Geng, R.; Wei, Y. Allicin Inhibits Proliferation and Invasion in Vitro and in Vivo via SHP-1-Mediated STAT3 Signaling in Cholangiocarcinoma. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 47, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Jeong, S.K.; Oh, S.J.; Lee, C.G.; Kang, Y.R.; Jo, W.S.; Jeong, M.H. The Resveratrol Analogue, HS-1793, Enhances the Effects of Radiation Therapy through the Induction of Anti-Tumor Immunity in Mammary Tumor Growth. Int. J. Oncol. 2020, 56, 1405–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aras, D.; Cinar, O.; Cakar, Z.; Ozkavukcu, S.; Can, A. Can Dicoumarol Be Used as a Gonad-Safe Anticancer Agent : An in Vitro and in Vivo Experimental Study. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 22, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.; Carmichael, A.R.; Griffiths, H.R. An Aqueous Extract of Fagonia Cretica Induces DNA Damage, Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in Breast Cancer Cells via FOXO3a and P53 Expression. PLoS One 2012, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Manjula, M. Anticarcinogenic Action of Quercetin by Downregulation of Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase ( PI3K ) and Protein Kinase C ( PKC ) via Induction of P53 in Hepatocellular Carcinoma ( HepG2 ) Cell Line. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2015, 42, 1407–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdy, M.; Elosaily, A.H.; Mohsen, E.; EL Hefnawy, H.M. Chemical Profile, Antioxidant and Anti-Alzheimer Activity of Leaves and Flowers of Markhamia Lutea Cultivated in Egypt: In Vitro and in Silico Studies. Futur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, K.L.; Muhammad, T.S.T.; Tan, M.L.; Sulaiman, S.F. Cytotoxic, Apoptotic and Anti-α-Glucosidase Activities of 3,4-Di-O-Caffeoyl Quinic Acid, an Antioxidant Isolated from the Polyphenolic-Rich Extract of Elephantopus Mollis Kunth. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 135, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeniçeri, E.; Altay, A.; Koksal, E.; Altın, S.; Taslimi, P.; Yılmaz, M.A.; Cakir, O.; Tarhan, A.; Kandemir, A. Phytochemical Profile by LC-MS/MS Analysis and Evaluation of Antioxidant, Antidiabetic, Anti-Alzheimer, and Anticancer Activity of Onobrychis Argyrea Leaf Extracts. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2024, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almilaibary, A. Phyto-Therapeutics as Anti-Cancer Agents in Breast Cancer: Pathway Targeting and Mechanistic Elucidation. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 31, 103935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, C.W.; Jeon, J.; Go, G.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.H. The Dual Role of Autophagy in Cancer Development and a Therapeutic Strategy for Cancer by Targeting Autophagy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, Y.-C.; Ho, C.-T.; Pan, M.-H. Recent Advances in Cancer Chemoprevention with Phytochemicals. J. Food Drug Anal. 2020, 28, 14–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimche, I.; Yu, H.; Ariantari, N.P.; Liu, Z.; Merkens, K.; Rotfuß, S.; Peter, K.; Jungwirth, U.; Bauer, N.; Kiefer, F.; et al. Phenanthroindolizidine Alkaloids Isolated from Tylophora Ovata as Potent Inhibitors of Inflammation, Spheroid Growth, and Invasion of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbizu-Berrocal, S.H.; Kim, H.; Fang, C.; Krenek, K.A.; Talcott, S.T.; Mertens-Talcott, S.U. Polyphenols from Mango (Mangifera Indica L.) Modulate PI3K/AKT/MTOR-Associated Micro-RNAs and Reduce Inflammation in Non-Cancer and Induce Cell Death in Breast Cancer Cells. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 55, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, V.C.; Guerra, G.C.B.; Araújo, D.F.D.S.; De Araújo, E.R.; De Araújo, A.A.; Dantas-Medeiros, R.; Zanatta, A.C.; Da Silva, I.L.G.; De Araújo Júnior, R.F.; Esposito, D.; et al. Chemopreventive and Immunomodulatory Effects of Phenolic-Rich Extract of Commiphora Leptophloeos against Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Preclinical Evidence. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattanamaneerusmee, A.; Thirapanmethee, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Bongcheewin, B.; Chomnawang, M.T. Chemopreventive and Biological Activities of Helicteres Isora L. Fruit Extracts. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 13, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Samarakoon, K.W.; Gyawali, R.; Park, Y.H.; Lee, S.J.; Oh, S.J.; Lee, T.H.; Jeong, D.K. Evaluation of the Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Anticancer Activities of Euphorbia Hirta Ethanolic Extract. Molecules 2014, 19, 14567–14581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drif, A.I.; Yücer, R.; Damiescu, R.; Ali, N.T.; Abu Hagar, T.H.; Avula, B.; Khan, I.A.; Efferth, T. Anti-Inflammatory and Cancer-Preventive Potential of Chamomile (Matricaria Chamomilla L.): A Comprehensive In Silico and In Vitro Study. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Samarakoon, K.W.; Gyawali, R.; Park, Y.H.; Lee, S.J.; Oh, S.J.; Lee, T.H.; Jeong, D.K. Evaluation of the Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Anticancer Activities of Euphorbia Hirta Ethanolic Extract. Molecules 2014, 19, 14567–14581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, R.G.; Rodrigues, S. de O.; Marques, L.A.; Oliveira, C.M. d.; Salles, B.C.C.; Zanatta, A.C.; Rocha, F.D.; Vilegas, W.; Pagnossa, J.P.; Fernanda, F.B.; et al. Eugenia Sonderiana O. Berg Leaves: Phytochemical Characterization, Evaluation of in Vitro and in Vivo Antidiabetic Effects, and Structure-Activity Correlation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 115126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Rahman, R.; Jayasingh Chellammal, H.S.; Ali Shah, S.A.; Mohd Zohdi, R.; Ramachandran, D.; Mohsin, H.F. Exploring the Therapeutic Potential of Derris Elliptica (Wall.) Benth in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats: Phytochemical Characterization and Antidiabetic Evaluation. Saudi Pharm. J. 2024, 32, 102016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanmaz, H.; Gokce, Y.; Hayaloglu, A.A. Volatiles, Phenolic Compounds and Bioactive Properties of Essential Oil and Aqueous Extract of Purple Basil (Ocimum Basilicum L.) and Antidiabetic Activity in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Wistar Rats. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Takeuchi, A.; Zhang, N.; Mori, R.; Mijiti, M.; Banno, A.; Okada, T.; Hiramatsu, N.; Nagaoka, S. Rose Polyphenols Exert Antiobesity Effect in High-Fat–Induced Obese Mice by Regulating Lipogenic Gene Expression. Nutr. Res. 2023, 119, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, Y.C.; Hsieh, P.H.; Pan, M.H.; Ho, C.T. Cellular Models for the Evaluation of the Antiobesity Effect of Selected Phytochemicals from Food and Herbs. J. Food Drug Anal. 2017, 25, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfram, S.; Wang, Y.; Thielecke, F. Anti-Obesity Effects of Green Tea: From Bedside to Bench. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2006, 50, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brattiya, K.; Jagdish, R.; Ahamed, A.; R, A.; J, J. Anti-Obesity and Anticancer Activity of Solanum Xanthocarpum Leaf Extract: An in Vitro Study. Natl. J. Physiol. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2023, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, J.H.; Lim, J. seok; Han, X.; Men, X.; Oh, G.; Fu, X.; Cho, G. hee; Hwang, W. sang; Choi, S. Il; Lee, O.H. Anti-Obesogenic Effect of Standardized Brassica Juncea Extract on Bisphenol A-Induced 3T3-L1 Preadipocytes and C57BL/6J Obese Mice. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 16, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.Y.; Huang, T.H.; Chen, W.J.; Aljuffali, I.A.; Hsu, C.Y. Rhubarb Hydroxyanthraquinones Act as Antiobesity Agents to Inhibit Adipogenesis and Enhance Lipolysis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 146, 112497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magwaza, S.N.; Erukainure, O.L.; Olofinsan, K.; Meriga, B.; Islam, M.S. Evaluation of the Antidiabetic, Antiobesity and Antioxidant Potential of Anthophycus Longifolius ((Turner) Kützing). Sci. African 2024, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, N.; Hawash, M. Anti-Obesity Activities of Rumex Rothschildianus Aarons. Extracts. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2021, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suescun, J.; Chandra, S.; Schiess, M.C. The Role of Neuroinflammation in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Transl. Inflamm. 2019, 241–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, M.; Mosa, O.F.; Nawaz, A.; Hamdoon, A.A.E.; Elkhalifa, M.E.M.; Sadiq, A.; Ullah, F.; Ahmed, A.; Kabra, A.; Khan, H.; et al. Neuroprotective Potentials of Lead Phytochemicals against Alzheimer’s Disease with Focus on Oxidative Stress-Mediated Signaling Pathways: Pharmacokinetic Challenges, Target Specificity, Clinical Trials and Future Perspectives. Phytomedicine 2024, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.N.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.X.; Huo, Y.L.; Ren, J.Y.; Bai, Z.Z.; Zhang, Y.L.; Tang, J.J. Neuroprotective Potential of Phytochemicals Isolated from Paeonia Ostii ‘Feng Dan’ Stamen. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 200, 116808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, B.; Sinha, S.N.; Sangaraju, R.; Huynh, T.; Patangay, S.; Venkata Mullapudi, S.; Mungamuri, S.K.; Patil, P.B.; Periketi, M.C. Extraction, Phytochemical Profile, and Neuroprotective Activity of Phyllanthus Emblica Fruit Extract against Sodium Valproate-Induced Postnatal Autism in BALB/c Mice. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, N.; Ibrahim, N.; Ali, A.E.; Youssef, F.S.; El-Ahmady, S.H. LC-QTOF-MS/MS Phytochemical Profiling of Tabebuia Impetiginosa (Mart. Ex DC.) Standl. Leaf and Assessment of Its Neuroprotective Potential in Rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerry Bone, S.M (Ed.) Principles of Herbal Pharmacology, 2nd ed. Elsevier, 2013; ISBN 9780443069925.

- Chen, Y.C.; Chia, Y.C.; Huang, B.M. Phytochemicals from Polyalthia Species: Potential and Implication on Anti-Oxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, Anti-Cancer, and Chemoprevention Activities. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amamra, S.; Cartea, M.E.; Belhaddad, O.E.; Soengas, P.; Baghiani, A.; Kaabi, I.; Arrar, L. Determination of Total Phenolics Contents, Antioxidant Capacity of Thymus Vulgaris Extracts Using Electrochemical and Spectrophotometric Methods. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2018, 13, 7882–7893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelouhab, K.; Guemmaz, T.; Karamać, M.; Kati, D.E.; Amarowicz, R.; Arrar, L. Phenolic Composition and Correlation with Antioxidant Properties of Various Organic Fractions from Hertia Cheirifolia Extracts. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2023, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteillier, A.; Cretton, S.; Ciclet, O.; Marcourt, L.; Ebrahimi, S.N.; Christen, P.; Cuendet, M. Cancer Chemopreventive Activity of Compounds Isolated from Waltheria Indica. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 203, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhy, Y.S.; Abo-Zeid, Y.S.; Mahgoub, S.S.; Mina, S.A.; Mady, M.S. In-Vitro Cytotoxic and Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Asparagus Densiflorus Meyeri and Its Phytochemical Investigation. Chem. Biodivers. 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamer, F.H.; Al-opari, A.M.; Al-Gani, A.M.S.; Al-jaberi, E.A.; Allugam, F.A.; Almahboub, H.H.; Mosik, H.M.; Khalil, H.H.; Abduljalil, M.M.; Alpogosh, M.Y.; et al. Capparis Cartilaginea Decne. as a Natural Source of Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Anti-Cancer Herbal Drug. Phytomedicine Plus 2024, 4, 100502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dania, O.E.; Dokunmu, T.M.; Adegboye, B.E.; Adeyemi, A.O.; Chibuzor, F.C.; Iweala, E.E.J. Pro-Estrogenic and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Corchorus Olitorius and Amaranthus Hybridus Leaves in DMBA-Induced Breast Cancer. Phytomedicine Plus 2024, 4, 100567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, F.; Islam, M.; Saeed, H.; Ishaq, M.; Shareef, U.; Qaisar, M.N.; Ullah, K.; Mansoor Rana, S.; Yasmeen, A.; Saleem, A. HPLC Profiling for the Simultaneous Estimation of Antidiabetic Compounds from Tradescantia Pallida. Arab. J. Chem. 2024, 17, 105703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latolla, N.; Reddy, S.; van de Venter, M.; Hlangothi, B. Phytochemical Composition and Antidiabetic Potential of the Leaf, Stem, and Rhizome Extracts of Cissampelos Capensis L.F. South African J. Bot. 2023, 163, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Joshi, T.; Joshi, T.; Chandra, S.; Tamta, S. In Silico Screening of Potential Antidiabetic Phytochemicals from Phyllanthus Emblica against Therapeutic Targets of Type 2 Diabetes. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannan, J.M.A.; Marenah, L.; Ali, L.; Rokeya, B.; Flatt, P.R.; Abdel-Wahab, Y.H.A. Ocimum Sanctum Leaf Extracts Stimulate Insulin Secretion from Perfused Pancreas, Isolated Islets and Clonal Pancreatic β-Cells. J. Endocrinol. 2006, 189, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Beshbishy, H.A.; Bahashwan, S.A. Hypoglycemic Effect of Basil (Ocimum Basilicum) Aqueous Extract Is Mediated through Inhibition of α-Glucosidase and α-Amylase Activities: An in Vitro Study. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2012, 28, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agada, R.; Thagriki, D.; Esther Lydia, D.; Khusro, A.; Alkahtani, J.; Al Shaqha, M.M.; Alwahibi, M.S.; Soliman Elshikh, M. Antioxidant and Anti-Diabetic Activities of Bioactive Fractions of Carica Papaya Seeds Extract. J. King Saud Univ. - Sci. 2021, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, R.; Kayani, W.K.; Ahmed, T.; Malik, F.; Hussain, S.; Ashfaq, M.; Ali, H.; Rubnawaz, S.; Green, B.D.; Calderwood, D.; et al. Assessment of Antidiabetic Potential and Phytochemical Profiling of Rhazya Stricta Root Extracts. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.N.R.; Afzal, S.; Khan, K.U.R.; Aati, H.Y.; Rao, H.; Ghalloo, B.A.; Shahzad, M.N.; Khan, D.A.; Esatbeyoglu, T.; Korma, S.A. Chemical Characterisation, Antidiabetic, Antibacterial, and In Silico Studies for Different Extracts of Haloxylon Stocksii (Boiss.) Benth: A Promising Halophyte. Molecules 2023, 28, 3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, V.; Nagpal, M.; Singh, I.; Singh, M.; Dhingra, G.A.; Huanbutta, K.; Dheer, D.; Sharma, A.; Sangnim, T. A Comprehensive Review on Nutraceuticals: Therapy Support and Formulation Challenges. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Martín, E.; Forbes-Hernández, T.; Romero, A.; Cianciosi, D.; Giampieri, F.; Battino, M. Influence of the Extraction Method on the Recovery of Bioactive Phenolic Compounds from Food Industry By-Products. Food Chem. 2022, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqil, F.; Munagala, R.; Jeyabalan, J.; Vadhanam, M. V. Bioavailability of Phytochemicals and Its Enhancement by Drug Delivery Systems. Cancer Lett. 2013, 334, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, R.A.; Moghadasian, M.H. Nutraceuticals and Nutrition Supplements: Challenges and Opportunities. Nutrients 2020, 12, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. Harnessing the Power of Plants: A Green Factory for Bioactive Compounds. Life 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Nirmal, P.; Kumar, M.; Jose, A.; Tomer, V.; Oz, E.; Proestos, C.; Zeng, M.; Elobeid, T.; Sneha, V.; et al. Major Phytochemicals: Recent Advances in Health Benefits and Extraction Method. Molecules 2023, 28, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Maaiden, E.; Bouzroud, S.; Nasser, B.; Moustaid, K.; El Mouttaqi, A.; Ibourki, M.; Boukcim, H.; Hirich, A.; Kouisni, L.; El Kharrassi, Y. A Comparative Study between Conventional and Advanced Extraction Techniques: Pharmaceutical and Cosmetic Properties of Plant Extracts. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannavacciuolo, C.; Pagliari, S.; Celano, R.; Campone, L.; Rastrelli, L. Critical Analysis of Green Extraction Techniques Used for Botanicals: Trends, Priorities, and Optimization Strategies-A Review. TrAC - Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 173, 117627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, R.; Pateiro, M.; Munekata, P.E.S.; McClements, D.J.; Lorenzo, J.M. Encapsulation of Bioactive Phytochemicals in Plant-Based Matrices and Application as Additives in Meat and Meat Products. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommakanti, V.; Puthenparambil Ajikumar, A.; Sivi, C.M.; Prakash, G.; Mundanat, A.S.; Ahmad, F.; Haque, S.; Prieto, M.A.; Rana, S.S. An Overview of Herbal Nutraceuticals, Their Extraction, Formulation, Therapeutic Effects and Potential Toxicity. Separations 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belwal, T.; Chemat, F.; Venskutonis, P.R.; Cravotto, G.; Jaiswal, D.K.; Bhatt, I.D.; Devkota, H.P.; Luo, Z. Recent Advances in Scaling-up of Non-Conventional Extraction Techniques: Learning from Successes and Failures. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 127, 115895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pateiro, M.; Barba, F.J.; Domínguez, R.; Sant’Ana, A.S.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A.; Gavahian, M.; Gómez, B.; Lorenzo, J.M. Essential Oils as Natural Additives to Prevent Oxidation Reactions in Meat and Meat Products: A Review. Food Res. Int. 2018, 113, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitwell, C.; Indra, S. Sen; Luke, C.; Kakoma, M.K. A Review of Modern and Conventional Extraction Techniques and Their Applications for Extracting Phytochemicals from Plants. Sci. African 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altemimi, A.; Lightfoot, D.A.; Kinsel, M.; Watson, D.G. Employing Response Surface Methodology for the Optimization of Ultrasound Assisted Extraction of Lutein and β-Carotene from Spinach. Molecules 2015, 20, 6611–6625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altemimi, A.; Lakhssassi, N.; Baharlouei, A.; Watson, D.G.; Lightfoot, D.A. Phytochemicals: Extraction, Isolation, and Identification of Bioactive Compounds from Plant Extracts. Plants 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Pang, X.; Xuewu, D.; Ji, Z.; Jiang, Y. Role of Peroxidase in Anthocyanin Degradation in Litchi Fruit Pericarp. Food Chem. 2005, 90, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulinacci, N.; Prucher, D.; Peruzzi, M.; Romani, A.; Pinelli, P.; Giaccherini, C.; Vincieri, F.F. Commercial and Laboratory Extracts from Artichoke Leaves: Estimation of Caffeoyl Esters and Flavonoidic Compounds Content. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2004, 34, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolescu, A.; Babotă, M.; Barros, L.; Rocchetti, G.; Lucini, L.; Tanase, C.; Mocan, A.; Bunea, C.I.; Crișan, G. Bioaccessibility and Bioactive Potential of Different Phytochemical Classes from Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manocha, S.; Dhiman, S.; Grewal, A.S.; Guarve, K. Nanotechnology: An Approach to Overcome Bioavailability Challenges of Nutraceuticals. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; McClements, D.J. Formulation of More Efficacious Curcumin Delivery Systems Using Colloid Science: Enhanced Solubility, Stability, and Bioavailability. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agriopoulou, S.; Tarapoulouzi, M.; Varzakas, T.; Jafari, S.M. Microorganisms Switzerland November. 2023.

- Kato, L.S.; Lelis, C.A.; da Silva, B.D.; Galvan, D.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Micro- and Nanoencapsulation of Natural Phytochemicals: Challenges and Recent Perspectives for the Food and Nutraceuticals Industry Applications. In Advances in Food and Nutrition Research; Toldrá, F., Ed.; Advances in Food and Nutrition Research; Academic Press, 2023; Vol. 104, pp. 77–137 ISBN 9780443193026.

- Alu’datt, M.H.; Alrosan, M.; Gammoh, S.; Tranchant, C.C.; Alhamad, M.N.; Rababah, T.; Zghoul, R.; Alzoubi, H.; Ghatasheh, S.; Ghozlan, K.; et al. Encapsulation-Based Technologies for Bioactive Compounds and Their Application in the Food Industry: A Roadmap for Food-Derived Functional and Health-Promoting Ingredients. Food Biosci. 2022, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, N.; Meghwal, M.; Das, K. Microencapsulation: An Overview on Concepts, Methods, Properties and Applications in Foods. Food Front. 2021, 2, 426–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, G.; Franco, P.; De Marco, I.; Xiao, J.; Capanoglu, E. A Review of Microencapsulation Methods for Food Antioxidants: Principles, Advantages, Drawbacks and Applications. Food Chem. 2019, 272, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pateiro, M.; Gómez, B.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Barba, F.J.; Putnik, P.; Kovačević, D.B.; Lorenzo, J.M. Nanoencapsulation of Promising Bioactive Compounds to Improve Their Absorption, Stability, Functionality and the Appearance of the Final Food Products. Molecules 2021, 26, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altemimi, A.B.; Farag, H.A.M.; Salih, T.H.; Awlqadr, F.H.; Al-Manhel, A.J.A.; Vieira, I.R.S.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Application of Nanoparticles in Human Nutrition: A Review. Nutrients 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Pal, P.; Pandey, B.; Goksen, G.; Sahoo, U.K.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Sarangi, P.K. Development of “Smart Foods” for Health by Nanoencapsulation: Novel Technologies and Challenges. Food Chem. X 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puttasiddaiah, R.; Lakshminarayana, R.; Somashekar, N.L.; Gupta, V.K.; Inbaraj, B.S.; Usmani, Z.; Raghavendra, V.B.; Sridhar, K.; Sharma, M.; Rennes-angers, L.I.A.; et al. Advances in Nanofabrication Technology for Nutraceuticals : New Insights and Future Trends. Bioengineered 2022, 9, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Lin, Q.; Zhao, H.; Li, X.; Sang, S.; McClements, D.J.; Long, J.; Jin, Z.; Wang, J.; Qiu, C. Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability of Phytochemicals: Influencing Factors, Improvements, and Evaluations. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 135, 108165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holst, B.; Williamson, G. Nutrients and Phytochemicals: From Bioavailability to Bioefficacy beyond Antioxidants. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2008, 19, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epriliati, I. Phytochemicals. In Phytochemicals - A Global Perspective of Their Role in Nutrition and Health; Rao, V., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shahidi, F.; Pan, Y. Influence of Food Matrix and Food Processing on the Chemical Interaction and Bioaccessibility of Dietary Phytochemicals: A Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 6421–6445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby-Pham, S.N.B.; Miller, R.B.; Howell, K.; Dunshea, F.; Bennett, L.E. Physicochemical Properties of Dietary Phytochemicals Can Predict Their Passive Absorption in the Human Small Intestine. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polia, F.; Pastor-Belda, M.; Martínez-Blázquez, A.; Horcajada, M.N.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; García-Villalba, R. Technological and Biotechnological Processes To Enhance the Bioavailability of Dietary (Poly)Phenols in Humans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 2092–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, N.A.; Eassa, H.A.; Amer, A.M.; Eltokhy, M.A.; Edafiogho, I.; Nounou, M.I. Nutraceuticals’ Novel Formulations: The Good, the Bad, the Unknown and Patents Involved. Recent Pat. Drug Deliv. Formul. 2019, 13, 105–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namal Senanayake, S.P.J. Green Tea Extract: Chemistry, Antioxidant Properties and Food Applications - A Review. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 1529–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumalla, A.V.S.; Hettiarachchy, N.S. Green Tea and Grape Seed Extracts - Potential Applications in Food Safety and Quality. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massounga Bora, A.F.; Ma, S.; Li, X.; Liu, L. Application of Microencapsulation for the Safe Delivery of Green Tea Polyphenols in Food Systems: Review and Recent Advances. Food Res. Int. 2018, 105, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto, G.; Martínez-Zamora, L.; Peñalver, R.; Marín-Iniesta, F.; Taboada-Rodríguez, A.; López-Gómez, A.; Martínez-Hernández, G.B. Applications of Plant Bioactive Compounds as Replacers of Synthetic Additives in the Food Industry. Foods 2023, 13, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duizer, L.M.; West, R.; Campanella, O.H. Fiber Addition to Cereal Based Foods: Effects on Sensory Properties. In Food Engineering Series; 2020; pp. 419–435.

- Muñoz-Almagro, N.; Garrido-Galand, S.; Taladrid, D.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V.; Villamiel, M.; Montilla, A. Use of Natural Low-Methoxyl Pectin from Sunflower by-Products for the Formulation of Low-Sucrose Strawberry Jams. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 102, 5957–5964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Sharma, H.K.; Kumar, N.; Kaur, M. The Effect of Inulin as a Fat Replacer on the Quality of Low-Fat Ice Cream. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2015, 68, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bastard, Q.; Chapelet, G.; Javaudin, F.; Lepelletier, D.; Batard, E.; Montassier, E. The Effects of Inulin on Gut Microbial Composition: A Systematic Review of Evidence from Human Studies. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 39, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsor-Atindana, J.; Chen, M.; Goff, H.D.; Zhong, F.; Sharif, H.R.; Li, Y. Functionality and Nutritional Aspects of Microcrystalline Cellulose in Food. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 172, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P.C.; Debnath, S.; Sharma, M.; Sridhar, K.; Nayak, P.K.; Inbaraj, B.S. Recent Advances in Cellulose-Based Hydrogels: Food Applications. Foods 2023, 12, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onipe, O.O.; Ramashia, S.E.; Jideani, A.I.O. Wheat Bran Modifications for Enhanced Nutrition and Functionality in Selected Food Products. Molecules 2021, 26, 3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]