Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

16 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Hardware and Software

2.1.1. Robot Setup

2.2. Prostate Segmentation

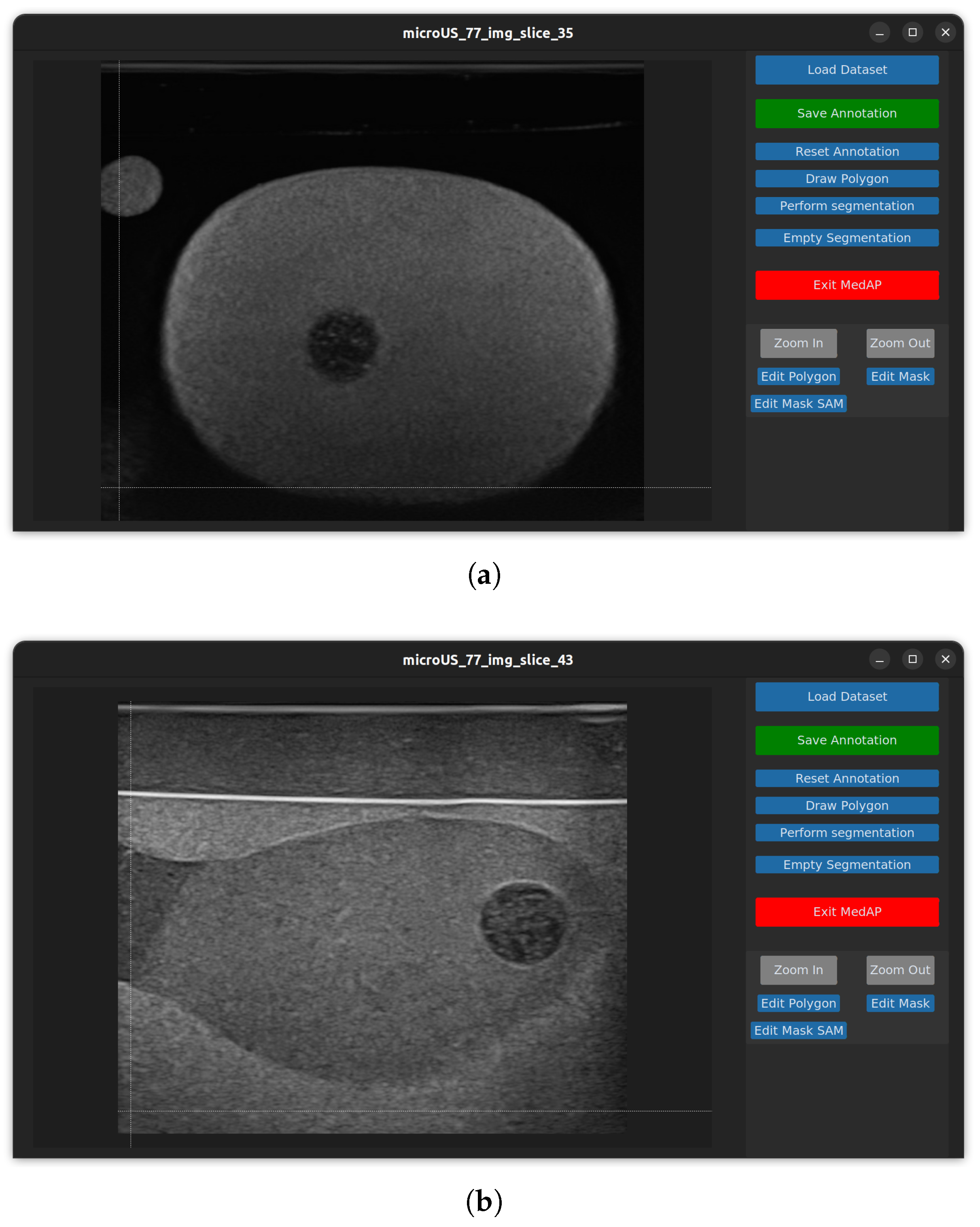

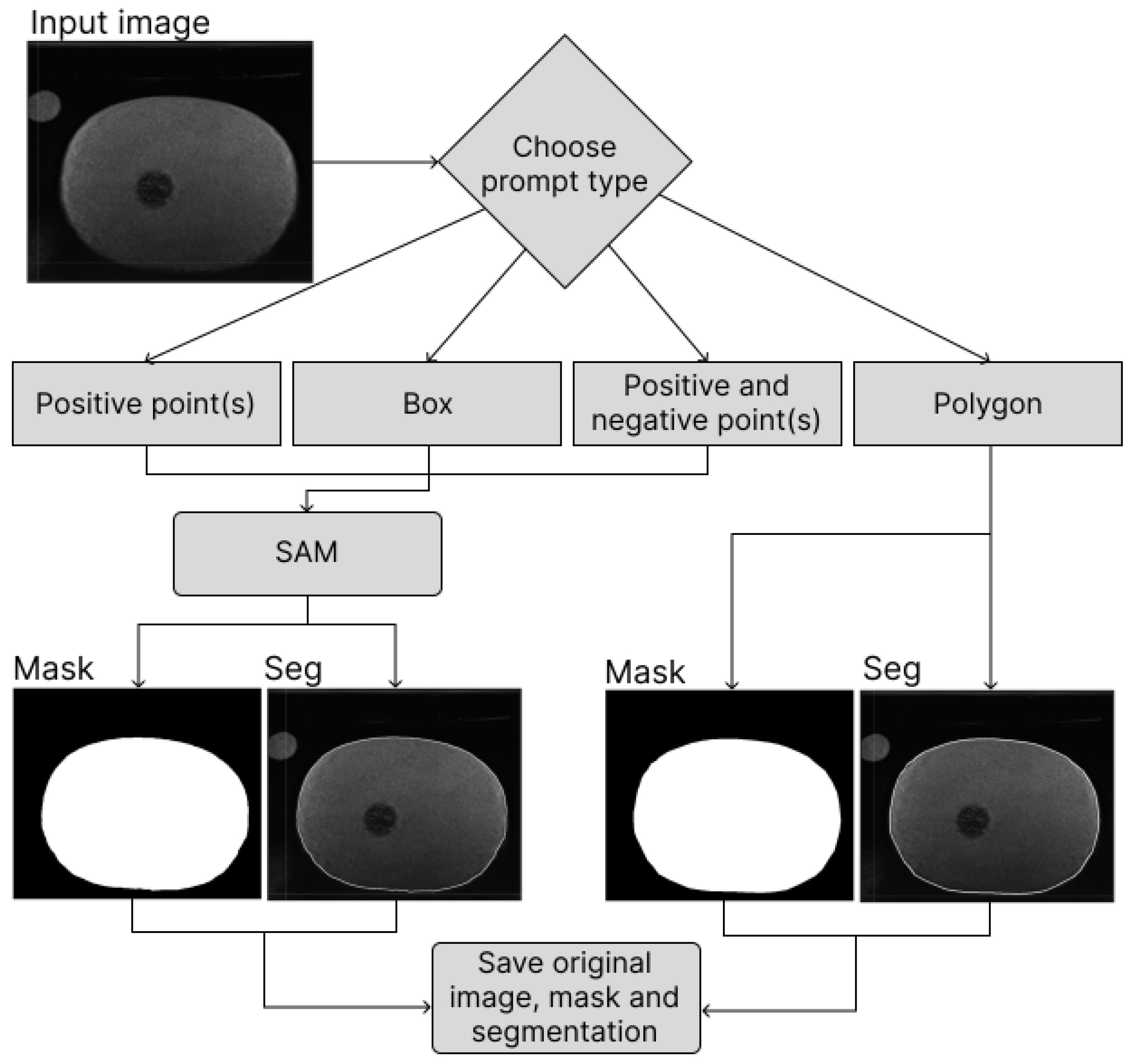

2.2.1. MedAP

2.2.2. Deep Attentive Features for Prostate Segmentation (DAF3D)

2.2.3. MicroSegNet

3. Results

3.1. Model Performance Evaluation

| Algorithm 1 Postprocessing procedure for segmentation images |

|

3.2. Prostate Reconstruction

| Length / [mm] | Width / [mm] | Height / [mm] | Volume / [] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesured | 55.9 ± 0.47 | 42.9 ± 0.42 | 37.3 ± 0.61 | 54058.2 ± 652.4 |

| Ground truth | 50 | 45 | 40 | 53000 |

| Length / [mm] | Width / [mm] | Height / [mm] | Volume / [] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesured | 58.0 ± 0.16 | 43.9 ± 0.43 | 37.4 ± 0.19 | 53217.6 ± 546.6 |

| Ground truth | - | - | - | 49000 |

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PSA | Prostate-Specific Antigen |

| DRE | Digital Rectal Examination |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| mpMRI | Multiparametric MRI |

| DOF | Degree of Freedom |

| ROS | Robot Operatinf System |

| TRUS | Transrectal Ultrasound |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| ViT | Vision Transformer |

| AG-BCE | Annotation-Guided Binary Cross-Entropy |

| MSDS | Multi-Scale Deep Supervision |

| ROS | Robot Operating System |

| TCP | Tool Center Point |

| MedAP | Medial Annotation Platform |

| SAM | Segment Anything |

| DICOM | Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine |

| NIfTI | (Neuroimaging Informatics Technology Initiative |

| DAF3D | Deep Attentive Features for Prostate Segmentation |

| GUI | Graphical User Interface |

References

- The GLOBOCAN 2022 cancer estimates: Data sources, methods, and a snapshot of the cancer burden worldwide - PubMed.

- McNeal, J.E.; Redwine, E.A.; Freiha, F.S.; Stamey, T.A. Zonal distribution of prostatic adenocarcinoma. Correlation with histologic pattern and direction of spread. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology 1988, 12, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegelin, O.; van Melick, H.H.E.; Hooft, L.; Bosch, J.L.H.R.; Reitsma, H.B.; Barentsz, J.O.; Somford, D.M. Comparing Three Different Techniques for Magnetic Resonance Imaging-targeted Prostate Biopsies: A Systematic Review of In-bore versus Magnetic Resonance Imaging-transrectal Ultrasound fusion versus Cognitive Registration. Is There a Preferred Technique? European Urology 2017, 71, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, T.; de Rooij, M.; Giganti, F.; Allen, C.; Barentsz, J.O.; Padhani, A.R. Quality checkpoints in the MRI-directed prostate cancer diagnostic pathway. Nature Reviews. Urology 2023, 20, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.I.; Muter, S.; Vladica, P.; Gillatt, D. Robotic-assisted magnetic resonance imaging ultrasound fusion results in higher significant cancer detection compared to cognitive prostate targeting in biopsy naive men. Translational Andrology and Urology 2020, 9, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouvière, O.; Jaouen, T.; Baseilhac, P.; Benomar, M.L.; Escande, R.; Crouzet, S.; Souchon, R. Artificial intelligence algorithms aimed at characterizing or detecting prostate cancer on MRI: How accurate are they when tested on independent cohorts? - A systematic review. Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging 2023, 104, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maris, B.; Tenga, C.; Vicario, R.; Palladino, L.; Murr, N.; De Piccoli, M.; Calanca, A.; Puliatti, S.; Micali, S.; Tafuri, A.; et al. Toward autonomous robotic prostate biopsy: a pilot study. International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery 2021, 16, 1393–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wetterauer, C.; Trotsenko, P.; Matthias, M.O.; Breit, C.; Keller, N.; Meyer, A.; Brantner, P.; Vlajnic, T.; Bubendorf, L.; Winkel, D.J.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy and clinical implications of robotic assisted MRI-US fusion guided target saturation biopsy of the prostate. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 20250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.Y.; Yang, X.Y.; Lee, H.J.; Law, Y.M.; Huang, H.H.; Lau, W.K.; Lee, L.S.; Ho, H.S.; Tay, K.J.; Cheng, C.W.; et al. Multiparametric MRI-ultrasonography software fusion prostate biopsy: initial results using a stereotactic robotic-assisted transperineal prostate biopsy platform comparing systematic vs targeted biopsy. BJU International 2020, 126, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porpiglia, F.; De Luca, S.; Passera, R.; Manfredi, M.; Mele, F.; Bollito, E.; De Pascale, A.; Cossu, M.; Aimar, R.; Veltri, A. Multiparametric-Magnetic Resonance/Ultrasound Fusion Targeted Prostate Biopsy Improves Agreement Between Biopsy and Radical Prostatectomy Gleason Score. Anticancer Research 2016, 36, 4833–4840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, W.; Liu, Y. An Analytical Inverse Kinematics Solution with the Avoidance of Joint Limits, Singularity and the Simulation of 7-DOF Anthropomorphic Manipulators. 48, 117–132. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liang, D.; Sun, L.; Guo, X.; Jiang, J.; Zuo, S.; Zhang, Y. Design and experimental study of a novel 7-DOF manipulator for transrectal ultrasound probe. Science Progress 2020, 103, 0036850420970366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H. Continuous Body Type Prostate Biopsy Robot for Confined Space Operation. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 113667–113677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.; Yuen, J.S.P.; Mohan, P.; Lim, E.W.; Cheng, C.W.S. Robotic transperineal prostate biopsy: pilot clinical study. Urology 2011, 78, 1203–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, P.; De Santis, M.; Ippoliti, S.; Orecchia, L.; Charlesworth, P.; Barrett, T.; Kastner, C. Vector Prostate Biopsy: A Novel Magnetic Resonance Imaging/Ultrasound Image Fusion Transperineal Biopsy Technique Using Electromagnetic Needle Tracking Under Local Anaesthesia. European Urology 2023, 83, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ipsen, S.; Wulff, D.; Kuhlemann, I.; Schweikard, A.; Ernst, F. Towards automated ultrasound imaging—robotic image acquisition in liver and prostate for long-term motion monitoring. Physics in Medicine & Biology 2021, 66, 094002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Pan, B.; Fu, Y.; Liu, Y. Development of a transperineal prostate biopsy robot guided by MRI-TRUS image. The International Journal of Medical Robotics and Computer Assisted Surgery 2021, 17, e2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoianovici, D.; Kim, C.; Petrisor, D.; Jun, C.; Lim, S.; Ball, M.W.; Ross, A.; Macura, K.J.; Allaf, M. MR Safe Robot, FDA Clearance, Safety and Feasibility Prostate Biopsy Clinical Trial. IEEE/ASME transactions on mechatronics: a joint publication of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society and the ASME Dynamic Systems and Control Division 2017, 22, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilak, G.; Tuncali, K.; Song, S.E.; Tokuda, J.; Olubiyi, O.; Fennessy, F.; Fedorov, A.; Penzkofer, T.; Tempany, C.; Hata, N. 3T MR-guided in-bore transperineal prostate biopsy: A comparison of robotic and manual needle-guidance templates: Robotic Template for MRI-Guided Biopsy. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2015, 42, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Jun, C.; Chang, D.; Petrisor, D.; Han, M.; Stoianovici, D. Robotic Transrectal Ultrasound Guided Prostate Biopsy. IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON BIOMEDICAL ENGINEERING 2019, 66, 2527–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, C.; Fedorov, A.; Kapur, T.; Yang, X. Segmentation of prostate from ultrasound images using level sets on active band and intensity variation across edges. Medical Physics 2016, 43, 3090–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsu, N. A Threshold Selection Method from Gray-Level Histograms. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics 1979, 9, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minaee, S.; Boykov, Y.Y.; Porikli, F.; Plaza, A.J.; Kehtarnavaz, N.; Terzopoulos, D. Image Segmentation Using Deep Learning: A Survey. pp. 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2015; Navab, N.; Hornegger, J.; Wells, W.M.; Frangi, A.F., Eds., Cham, 2015; pp. 234–241.

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale, 2021, [arXiv:cs.CV/2010.11929].

- Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Luo, X.; Adeli, E.; Wang, Y.; Lu, L.; Yuille, A.L.; Zhou, Y. TransUNet: Transformers Make Strong Encoders for Medical Image Segmentation.

- Jiang, H.; Imran, M.; Muralidharan, P.; Patel, A.; Pensa, J.; Liang, M.; Benidir, T.; Grajo, J.R.; Joseph, J.P.; Terry, R.; et al. MicroSegNet: A deep learning approach for prostate segmentation on micro-ultrasound images. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics 2024, 112, 102326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlaka, D.; Švaco, M.; Chudy, D.; Jerbić, B.; Šekoranja, B.; Šuligoj, F.; Vidaković, J.; Romić, D.; Raguž, M. Frameless stereotactic brain biopsy: A prospective study on robot-assisted brain biopsies performed on 32 patients by using the RONNA G4 system. The international journal of medical robotics + computer assisted surgery: MRCAS 2021, 17, e2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raguž, M.; Dlaka, D.; Orešković, D.; Kaštelančić, A.; Chudy, D.; Jerbić, B.; Šekoranja, B.; Šuligoj, F.; Švaco, M. Frameless stereotactic brain biopsy and external ventricular drainage placement using the RONNA G4 system. Journal of Surgical Case Reports 2022, 2022, rjac151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macenski, S.; Foote, T.; Gerkey, B.; Lalancette, C.; Woodall, W. Robot Operating System 2: Design, architecture, and uses in the wild. Science Robotics 2022, 7, eabm6074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, M.; Mower, C.E.; Ourselin, S.; Vercauteren, T.; Bergeles, C. LBR-Stack: ROS 2 and Python Integration of KUKA FRI for Med and IIWA Robots. Journal of Open Source Software 2024, 9, 6138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.Y.; et al. Segment Anything. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). IEEE, pp. 3992–4003. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dou, H.; Hu, X.; Zhu, L.; Yang, X.; Xu, M.; Qin, J.; Heng, P.A.; Wang, T.; Ni, D. Deep Attentive Features for Prostate Segmentation in 3D Transrectal Ultrasound. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2019, 38, 2768–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, S.; Girshick, R.; Dollar, P.; Tu, Z.; He, K. Aggregated Residual Transformations for Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). IEEE, pp. 5987–5995. [CrossRef]

- Suligoj, F.; Heunis, C.M.; Sikorski, J.; Misra, S. RobUSt–An Autonomous Robotic Ultrasound System for Medical Imaging. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 67456–67465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Hu, F.; Chen, P.; Zhang, H.; Song, L.; Yu, Y. Human-Robot Interaction of a Craniotomy Robot Based on Fuzzy Model Reference Learning Control. Transactions of FAMENA 2024, 48, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fold no. | DAF3D | MicroSegNet | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dice Score | Jaccard Score | Dice Score | Jaccard Score | |

| 1 | 0.905432 | 0.829091 | 0.936580 | 0.885725 |

| 2 | 0.897736 | 0.819591 | 0.931808 | 0.881644 |

| 3 | 0.899132 | 0.820070 | 0.932482 | 0.884236 |

| 4 | 0.906388 | 0.831164 | 0.930665 | 0.877613 |

| 5 | 0.903041 | 0.825669 | 0.926850 | 0.873178 |

| Average | 0.902346 | 0.825117 | 0.931677 | 0.880479 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).