1. Introduction

Liquid crystal (LC) materials, particularly those exhibiting smectic phases, are crucial for advanced electro-optical applications, including high-performance displays, spatial light modulators, and optical switches [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

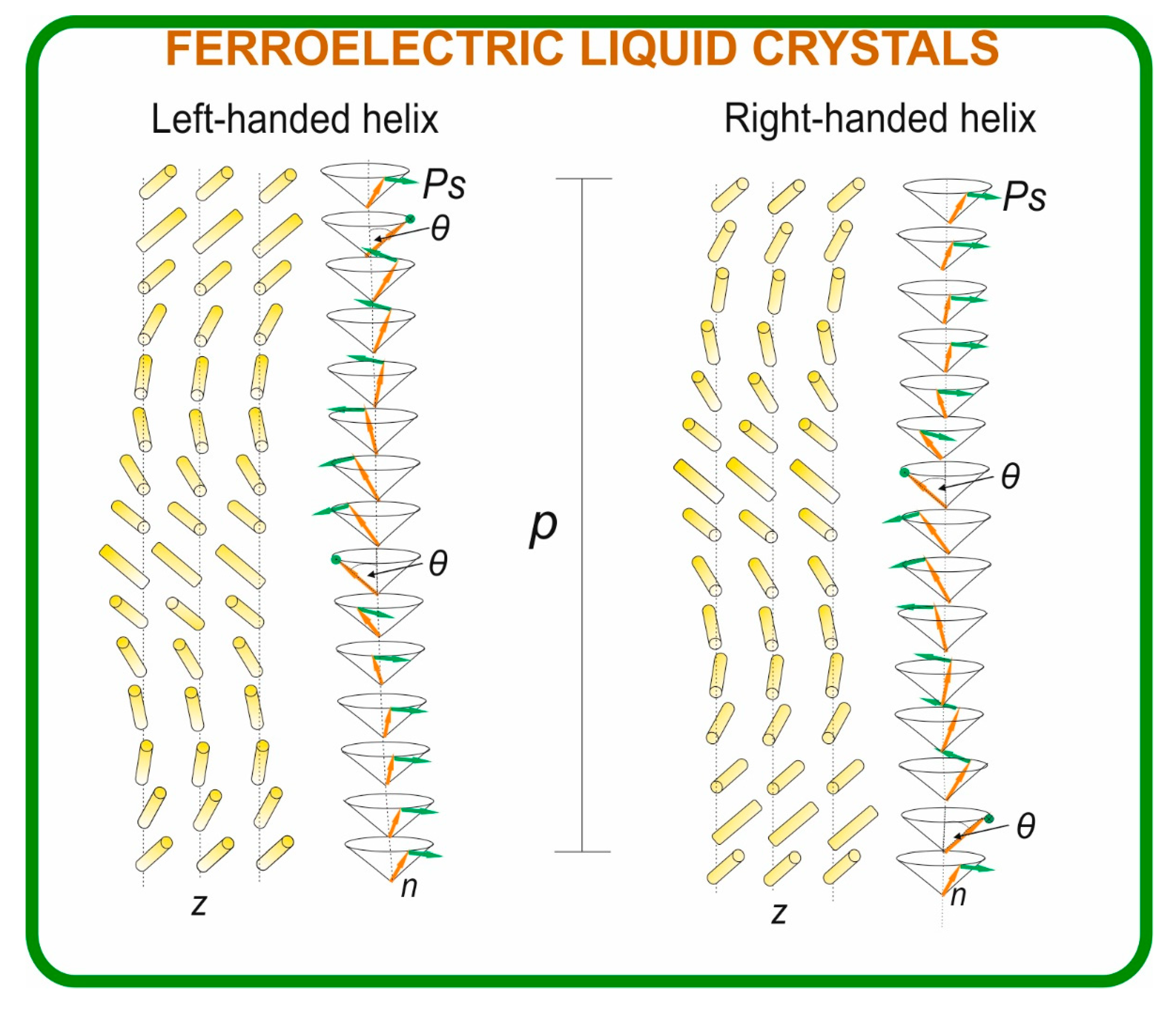

9]. Liquid crystals exist in a mesomorphic state and may comprise multiple sub-phases, each distinguished by its specific molecular ordering. Among these, nematic liquid crystals (NLCs) exhibit long-range orientational order without positional order, meaning their molecular long axes align along a common director (

n) but lack a fixed spatial arrangement. In contrast, smectic liquid crystals (SLCs) are organized into layered structures, maintaining orientational order while forming distinct, structured arrangements. Among these, the SmA and SmC phases are particularly significant due to their widespread applicability. In the SmA phase, molecules, i.e. the director, align perpendicularly to the layers, whereas in the SmC phase, the director tilts at an angle (

θ) with respect to the layer normal.

A crucial subclass of the smectic phases is the chiral smectic C (SmC*) phase[

10], which, due to its intrinsic chirality, exhibits spontaneous polarization (

Ps), rendering it ferroelectric. This characteristic makes the SmC* materials—commonly referred to as ferroelectric liquid crystals (FLCs)—highly desirable for applications requiring high-speed electro-optical switching[

11]. However, it is still almost impossible to reach the desirable properties of the FLCs in a single molecule material [

12,

13]. That is why the design of binary and multicomponent FLC mixtures remains an effective tool for tuning their properties and getting the required ones by the specific applications [

13,

14,

15,

16].

The electro-optical performance of FLCs depends on several critical parameters, including the mentioned tilt angle (

θ) and spontaneous polarization (

Ps), as well as the helical pitch length (

p), switching time (

τ), and rotational viscosity (

γφ). The helical pitch represents the periodicity over which molecular orientation, i.e. the director, rotates for 360

o forming a helical superstructure (see

Figure 1). The switching time τ defines the response speed between two stable electro-optical states, while the rotational viscosity determines the ease of molecular reorientation under an external electric field. Achieving materials with the SmC* phase and optimal properties over a broad temperature range remains a key challenge in FLC development [

14,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

There are two principally different electro-optical effects exploiting FLCs: the surface-stabilized ferroelectric liquid crystal (SSFLC) effect [

10] and the deformed helix ferroelectric liquid crystal (DHFLC) effect [

30,

31]. The SSFLC effect is based on surface-induced synclinic ordering, where interactions with confining substrates unwind the intrinsic FLC helical structure. This requires ultra-thin electro-optical cells with thicknesses below the helical pitch. The molecular alignment changes under an applied electric field, stabilizing in two synclinic states even after the field is removed. This bistability enables high-contrast optical switching, making SSFLCs ideal for memory-based electro-optical devices.

In contrast, the DHFLC effect leverages the deformation of the helical structure under an electric field. In this configuration, the helix axis is aligned parallel to the electro-optical cell, defining the optical axis of the medium. Unlike SSFLCs, the heliconical structure remains intact, requiring materials with short helical pitch (below the cell thickness). The application of a low-voltage electric field deforms the helix, inducing a tilt in the optical axis and modulating light polarization. At small voltages, the tilt angle varies linearly with field intensity, whereas at higher voltages, the helix unwinds, yielding SSFLC-like behaviour. While DHFLCs lack bistability, they offer grayscale rendering, operate at lower driving voltages, and require no threshold voltage, making them promising candidates for next-generation photonic devices, including optical sensors and fast-switching display technologies [

32,

33].

In our days, the FLC mixtures are formulated using two primary strategies: (i) by introducing a chiral dopant —either bichiral or monochiral—into a low-viscosity achiral SmC base mixture [

34,

35,

36] or (ii) by employing purely monochiral FLC compounds [

19,

37,

38,

39,

40]. The former approach allows the fine-tuning of material properties but often results in a lower tilt angle of the director. Conversely, materials composed exclusively of monochiral FLCs typically exhibit high tilt angles but present challenges in optimizing other physicochemical parameters, often leading to increased viscosity [

41]. Both approaches share a common drawback: difficulty in achieving low melting temperatures, which are necessary for stable FLC operation in both DHFLC and SSFLC modes at sub-zero temperatures. The ability to develop FLC materials that retain their electro-optical performance at low temperatures is essential for applications requiring high stability in extreme environmental conditions (for ex., low temperature).

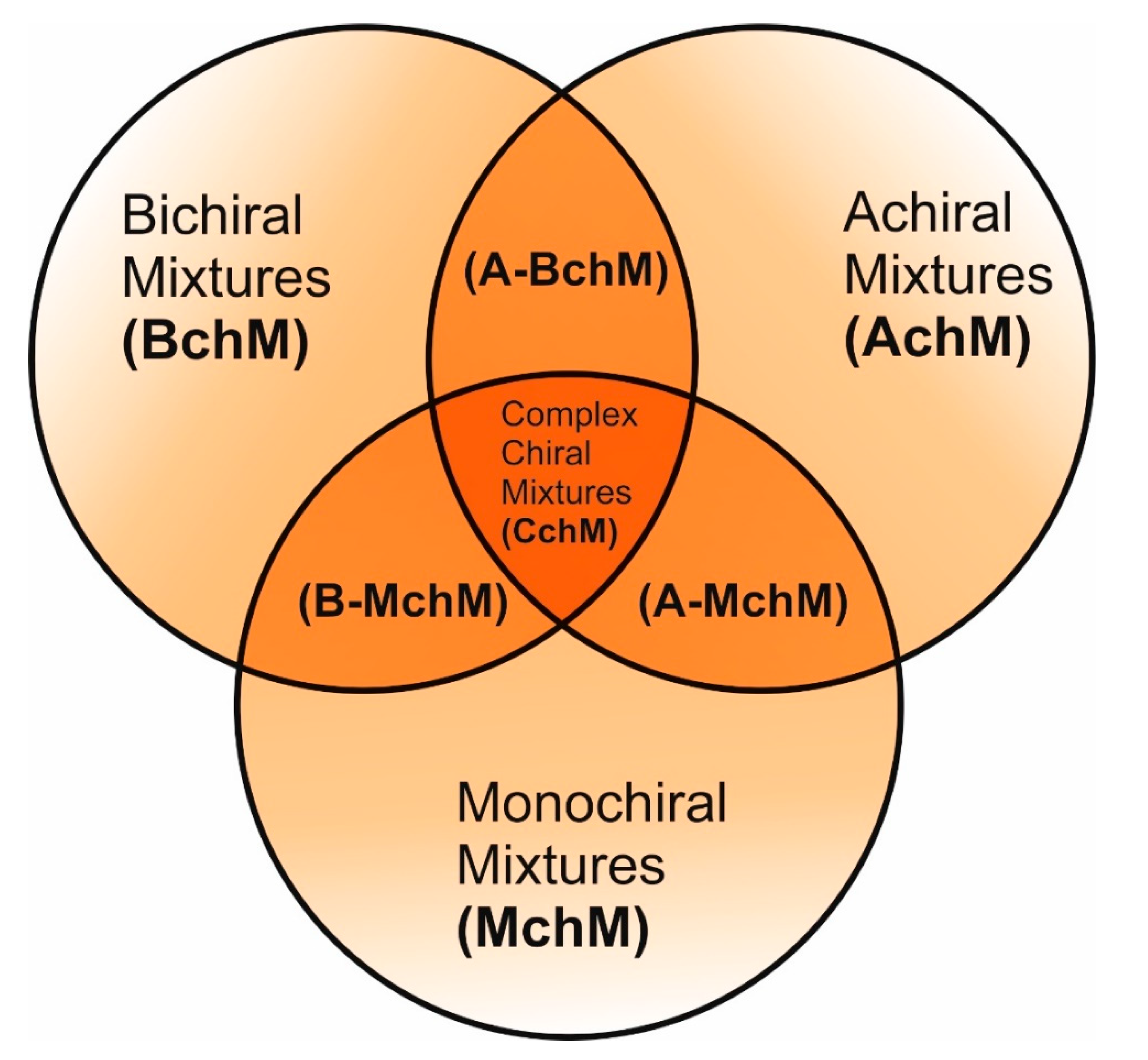

Here, we present a novel series of systematically designed FLC mixtures build-up in a way to elucidate the impact of chirality on mesomorphic stability, electro-optical response, and key physicochemical parameters (

Figure 2). For the first time, we have developed a complex chiral mixture (CchM) incorporating achiral, monochiral, and bichiral components. This approach has enabled the formulation of an FLC material with an exceptionally low melting temperature but with the preservation of other physicochemical properties, making it highly suitable for DHFLC applications. These findings represent a significant advancement in the development of next-generation ferroelectric LC materials, offering new avenues for their integration into cutting-edge electro-optical technologies.

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. FLC Mixtures

In this study, liquid crystal materials were systematically developed based on three primary base mixtures. The initial step involved determining the eutectic composition of each base mixture using a MATLAB-based computational program developed at the Military University of Technology (MUT). This program employs thermodynamic modelling based on the equations (1) and (2):

where

and

denote the enthalpy of fusion and melting temperature of component

k, respectively. The variable

represents the mole fraction of component

k,

n is the total number of components,

R is the universal gas constant, and

k serves as the component index.

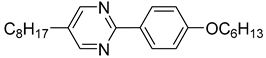

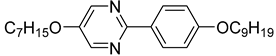

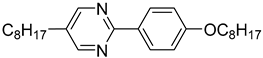

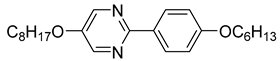

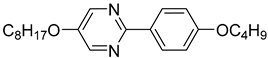

The first developed base mixture, referred to as the eutectic achiral mixture (AchM), comprises ten two-ring organic compounds in varying specific proportions [

35]. These compounds share a characteristic core structure typical of the SmC materials, consisting of a pyrimidine and a benzene ring. However, they differ in their terminal groups—either aliphatic or alkoxy in various configurations—and in the length of these groups, which range from four to ten carbon atoms. The detailed composition of the AchM mixture, along with the weight fraction values of its constituents, is presented in

Table 1.

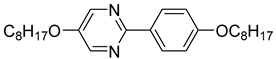

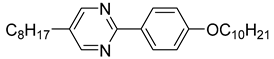

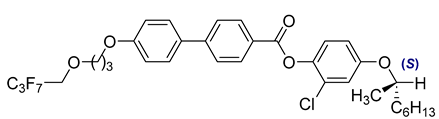

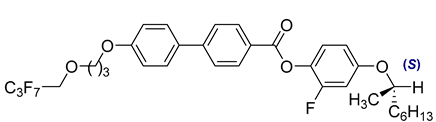

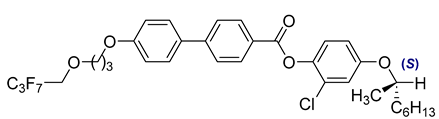

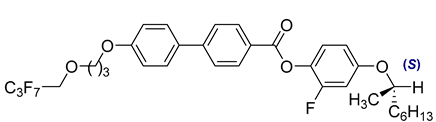

The second base mixture, referred to as the eutectic monochiral mixture (MchM), is a binary system composed of compounds featuring a single chiral centre [

41]. Both constituents exhibit three-ring rigid core with terminal alkoxy substituents. For both compounds, hydrogen atoms within the unbranched alkyl chain are partially substituted with fluorine atoms, and an ester group is positioned between two benzene rings. A key structural distinction lies in the lateral substitution on the benzene ring close to the chiral chain: one compound incorporates a chlorine atom, whereas the other one possesses a fluorine atom. The detailed composition of the MchM mixture, including the relative proportions of its constituents, is presented in

Table 2.

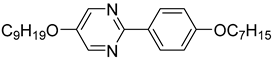

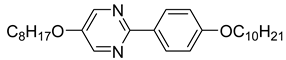

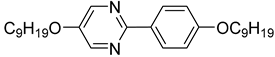

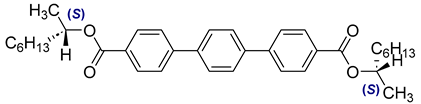

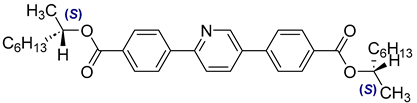

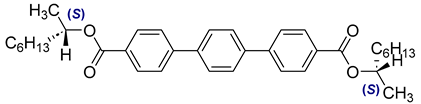

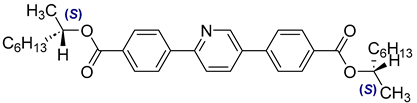

The third base mixture, designated as the bichiral mixture (BchM), consists of compounds possessing two chiral centres[

42]. These molecules are characterized by a rigid core comprising three benzene rings and two identical terminal chiral chains containing ester groups. The primary structural differentiation between the two constituents arises from the presence or absence of a nitrogen atom in the central benzene ring. Specifically, one compound consists solely of benzene rings, while in the other, a pyridine ring replaces one of the benzene rings. The composition of the BchM mixture is presented in

Table 3.

Initial characterization was performed on the base mixtures themselves. Subsequently, novel formulations were obtained by combining these base mixtures in various weight ratios, followed by further experimental investigations of the resulting compositions. These additional systems, designed by mixing the three base mixtures in different proportions, are summarized in

Table 4.

2.2. Polarizing Optical Microscopy and Differential Scanning Calorimetry

To measure phase transition temperatures and identify phases, a polarizing optical microscope (POM) was used. The sample was placed between crossed polarizers and analysed on a heating stage that controlled its temperature, allowing for the determination of phase transition temperatures. Both heating and cooling were performed at a rate of 2°C/min, and the apparatus provided temperature measurements with an accuracy of 0.1°C. The experiments were conducted using an Olympus BX51 POM equipped with a LINKAM THMS 600 heating stage. The microscope image was observed on a monitor via an FW ColorView III camera, while the heating stage temperature was controlled using a Linkam CI-94 temperature controller. To further investigate thermal properties, differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was used to determine the phase transition temperatures and enthalpy changes. During the experiments, the samples were heated and cooled at a rate of 2°C/min, while the measurement chamber was flushed with gaseous nitrogen at a flow rate of 20 ml/min. The DSC 204 F1 calorimeter from NETZSCH was used for these studies. The weight of samples used for the DSC measurements was 10.00-12.00 mg.

2.3. Helical Pitch Measurement

For the measurement of the helical pitch length (

p), the studied material was applied onto a glass slide coated with a 5% solution of octadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (C₁₈H₃₇(CH₃)₃N⁺Br⁻) in ethanol, which ensures the homeotropic alignment. After the solvent evaporated, the test material was deposited, and the sample was heated by a heating stage until it transitioned into the isotropic (Iso) liquid phase. The prepared slide was then placed into a brass cuvette, and the measurement was initiated. First, a reference curve was always recorded without the test material, followed by the actual measurement with the sample applied. The highest temperature used was the transition temperature from the lower-ordered phase to the chiral tilted phase, while the lowest achievable temperature was 2°C. The cooling was performed at a rate of 5°C/min, with measurements taken at 3°C intervals. Each measurement was preceded by a temperature stabilization period of 4 minutes. Helical pitch determination was based on the selective reflection phenomenon [

38] and analysed using a SHIMADZU UV-3600 UV-VIS-NIR spectrophotometer, operating within the 360–3000 nm wavelength range. Temperature control was achieved using the U7 MLW thermostat (SHIMADZU). The selectively reflected wavelength (

λs) was determined at half the height and width of the reflection band, and the helical pitch was subsequently calculated using the equation (3):

where

nav is the value of the average refractive index;

nav = 1.5 was taken for calculation [

43].

2.4. Electro-Optical Properties, Spontaneous Polarization and Tilt Angle

To investigate electro-optical properties, a test cell consisting of two glass plates separated by a 1.6 μm gap was constructed. The plates were pre-coated with a polyimide (Nylon 6) alignment layer and transparent Indium Tin Oxide (ITO) electrodes. The inner surfaces of the cell were rubbed in opposite directions, creating an anti-parallel rubbing alignment. In the isotropic phase, the tested materials were filled into the cell; due to low viscosity and capillary forces, the LC substance was homogeneously distributed throughout the entire volume of the test cell. The prepared cell was then placed on a Linkam HFS91 heating stage in a BIOLAR PZO polarizing microscope equipped with a THORLABS PDA100A-EC photodetector. Electro-optical measurements were conducted using a Rohde & Schwarz HMF2550 arbitrary function generator, an HM0724 oscilloscope, and a Linkam TMS93 temperature controller, with a twenty-fold amplification of the control signal using an FLC F20AD amplifier.

Switching time was determined by measuring the interval at which transmittance reached 90% of its maximum during the transition between two synclinic states, induced by a rectangular electrical signal. The director tilt angle was evaluated by applying a rectangular electrical signal with a voltage range of 14–30 V and a frequency of 30 Hz to the electro-optical cell [

44]. This resulted in two synclinic states corresponding to opposite polarity of the electric field. By rotating the microscope stage, two minima in transmittance were identified for positive and negative applied voltages. These dips, observed when the optical axis and polarization plane were parallel, enabled the determination of the director tilt angle (2

θ) as the values between the two dark states. Measurements were conducted as a function of temperature, with steps of 2°C, 3°C, and finally 5°C at lower temperatures. Spontaneous polarization measurements were performed using the same electro-optical cell, connected in series with an MCP BXR-07 decade resistor with a resistance of R

0 = 13 kΩ. A triangular voltage of 20–30 V at a frequency of 50 Hz was applied, and measurements were based on the voltage drop across the resistor [

45]. Data acquisition was carried out using a custom-developed computer program created at the Military University of Technology in Warsaw in the LabVIEW environment. The active area of the cell was 0.25 cm²; the 1.6 μm thick cells were used for the measurements.

The temperature dependence of the rotational viscosity (γ

φ) for the selected materials was determined based on switching time and spontaneous polarization measurements, using the semi-empirical formula (4) [

46]:

where E = U/d, U represents the applied voltage, and d denotes the cell gap.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mesomorphic Behaviour

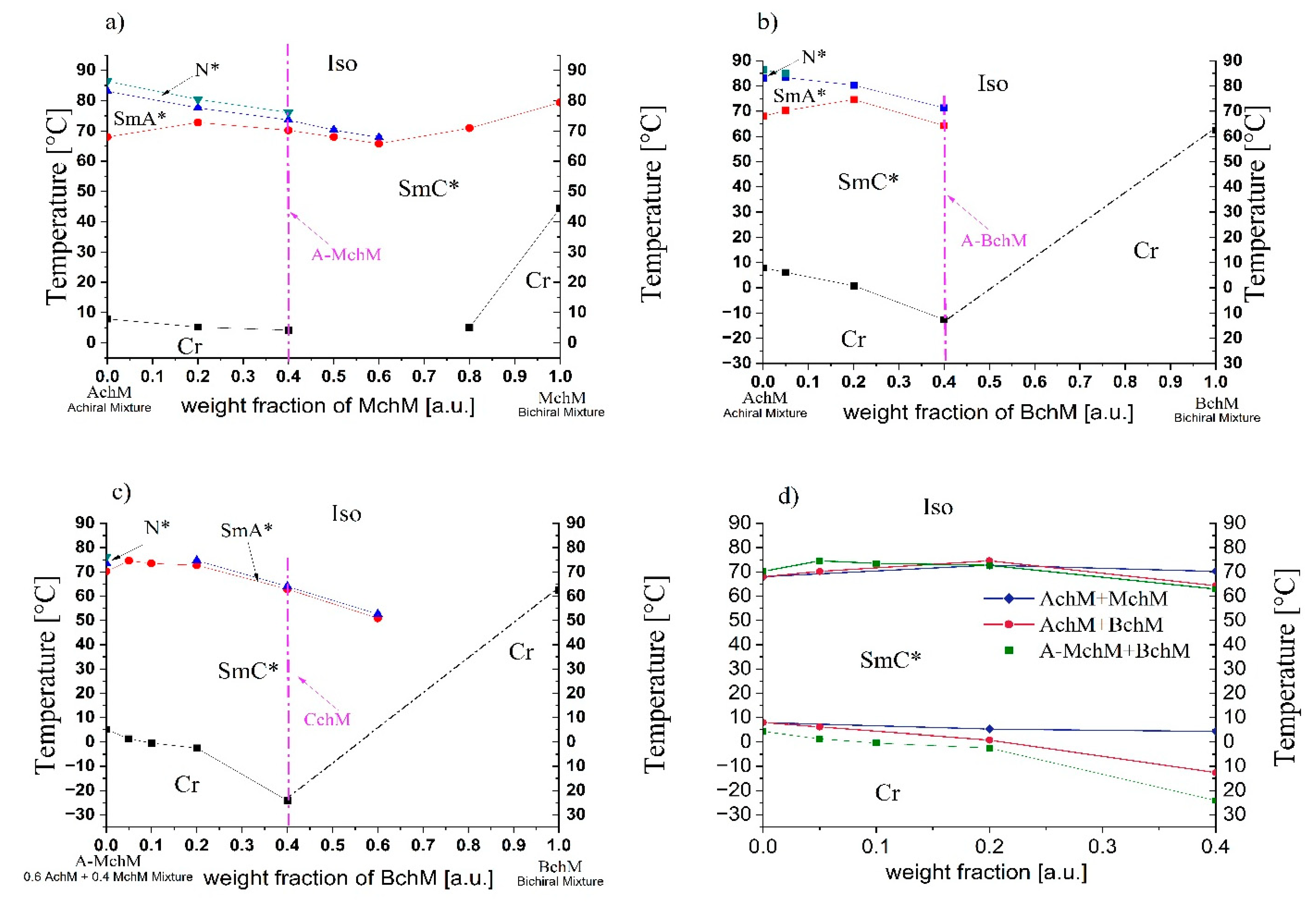

The investigated multicomponent systems consisted of three types of mixtures: (i) achiral (AchM) combined with monochiral (MchM), (ii) achiral (AchM) combined with bichiral (BchM), and (iii) the achiral-monochiral mixture (A-MchM) combined with bichiral (BchM) as was presented in

Figure 3 and

Table 4. The phase diagrams of these systems are shown in

Figure 3 and detailed temperatures and enthalpies of each prepared mixture are collected in

Table S1 (ESI).

The achiral AchM mixture exhibits three distinct liquid crystal phases: a broad-temperature-range tilted SmC phase, the orthogonal SmA phase, and the N phase (see

Table S1, ESI). The phase diagram of the AchM-MChM system (

Figure 3a) reveals that all its mixtures retain a wide-temperature-range ferroelectric phase and exhibit melting points below room temperature. Additionally, in mixtures containing up to 0.6 weight fraction of MchM in AchM, the SmA* phase persists, while the N* phase is maintained up to a composition of 0.4. The mixture consisting of 0.4 weight fraction of MchM in AchM exhibited one of the lowest melting temperatures and a reasonably high SmC*–SmA* phase transition temperature (above 70°C), making it the optimal candidate for further studies. This mixture was subsequently designated as A-MchM and served as the basis for preparing the final system, which incorporated components with all three degrees of chirality. In the second system, the AchM mixture was doped with a non-mesogenic bichiral (BchM) mixture, which has a melting point of 62.4°C (see

Table S1, ESI). The phase diagram of this system (

Figure 3b) shows the disappearance of the N* phase at chiral mixture concentrations exceeding a weight fraction of 0.05. Up to a composition of 0.4, the SmA* phase remains present; however, it becomes destabilized in favour of the ferroelectric phase. The temperature range of the SmC* phase expands up to a chiral mixture concentration of 0.2, beyond which it undergoes significant destabilization. The melting temperature decreases substantially, reaching -12.6°C for the mixture containing a 0.4 weight fraction of BChM. The final system was obtained by combining the achiral-monochiral mixture (A-MchM) with the bichiral mixture (BchM). In this system, an increasing concentration of BchM resulted in a further expansion of the SmC* phase while significantly lowering the melting temperature (

Figure 3c).

Among the multiple mixtures initially synthesized and analysed, only three FLC materials were selected for further investigation based on a comprehensive assessment of their mesomorphic properties. This selection process identified three key formulations for advanced studies: (i) the optimized achiral-monochiral mixture, 0.6 AchM + 0.4 MchM (A-MchM), (ii) the achiral-bichiral mixture, 0.6 AchM + 0.4 BchM (A-BchM), and (iii) the optimized achiral-monochiral-bichiral system, 0.6 A-MchM + 0.4 BchM, referred to as the complex chiral mixture (CchM). The remaining mixtures from the three examined systems were excluded from further analysis due to either limited phase stability or elevated melting temperatures (

Figure 2d), which restricted their suitability for advanced electro-optic applications.

Two of the selected mixtures (A-BchM and CchM) exhibit melting temperatures below 0°C, while all three maintain a stable ferroelectric phase up to 62°C (

Table 5). Notably, the complex chiral mixture (CchM), which incorporates all chirality levels, demonstrates the most pronounced extension of the ferroelectric phase range at lower temperatures. DSC traces for A-MchM, A-BchM, and CchM are presented in

Figure S1 (ESI).

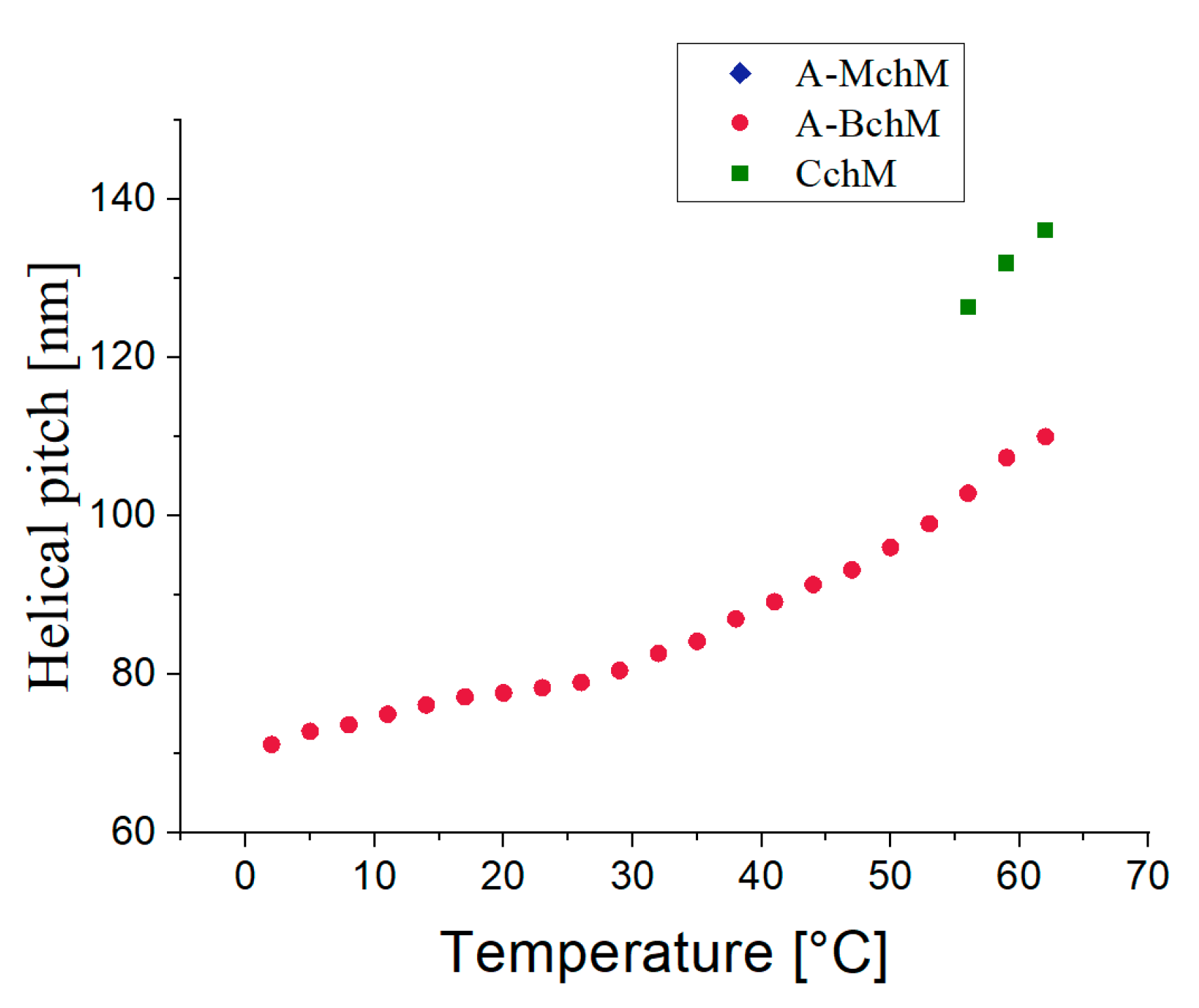

3.2. Helical Pitch

Figure 4 shows the temperature dependence of the helical pitch for the selected mixtures. It can be observed that as the temperature decreases, the helical pitch of A-BchM and CchM mixtures also decreases. Notably, in A-BchM mixture, the helical pitch remains the smallest across the entire temperature range of the ferroelectric phase. For the other mixtures, the data were only partially recorded due to limitations of the spectrophotometer's measurement range. In the case of the CchM mixture, three data points were obtained at temperatures above 55°C, while at lower temperatures, the selectively reflected wavelength values fell below 360 nm. Conversely, for A-MchM mixture, the helical pitch values exceeded the upper measurement limit of the spectrophotometer (

p>1.5 µm). The exceptionally low helical pitch values recorded for A-BchM mixture were made possible by the appearance of a second-order selective reflection band in the spectra (see

Figure S2, ESI). When all three base mixtures are combined, the helical pitch does not further decrease beyond that observed in the achiral–bichiral system. This suggests differential twisting efficiencies between the chiral components, ultimately constraining further helical pitch reduction.

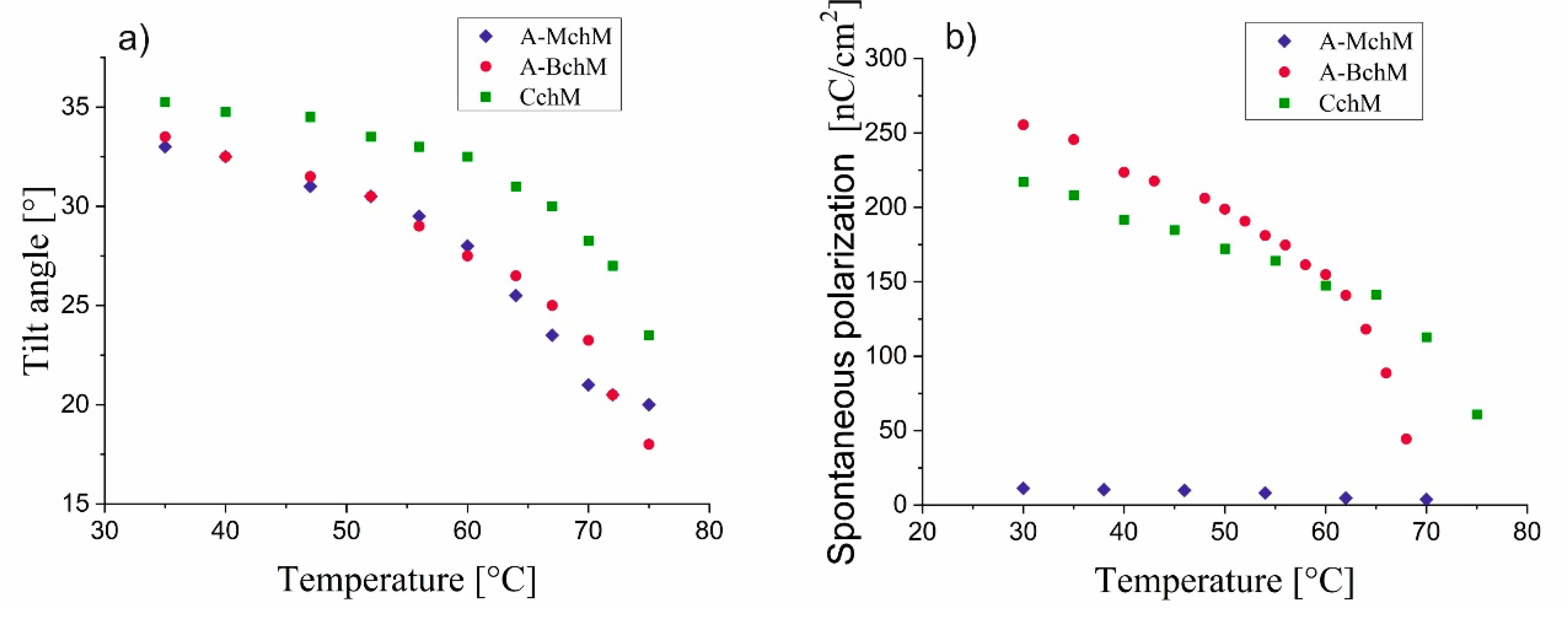

3.3. Tilt Angle and Spontaneous Polarization

As shown in

Figure 5a, the tilt angle decreases with increasing temperature for all selected mixtures. The highest values of the tilt angle are observed for CchM mixture, which incorporates achiral, monochiral, and bichiral components. The other mixtures exhibit quite comparable tilt angle values. Notably, for all selected mixtures, the tilt angle values remain above 32° at 30°C. The highest values of the spontaneous polarization are observed for the mixture A-BchM (

Figure 5b). Introducing a mixture containing compounds with a single chiral centre (MchM) into this system results in a reduction of spontaneous polarization. This effect may arise due to the opposing signs of the spontaneous polarization vector generated by the components of BchM and AchM mixtures. The lowest spontaneous polarization values are recorded for mixture A-MchM.

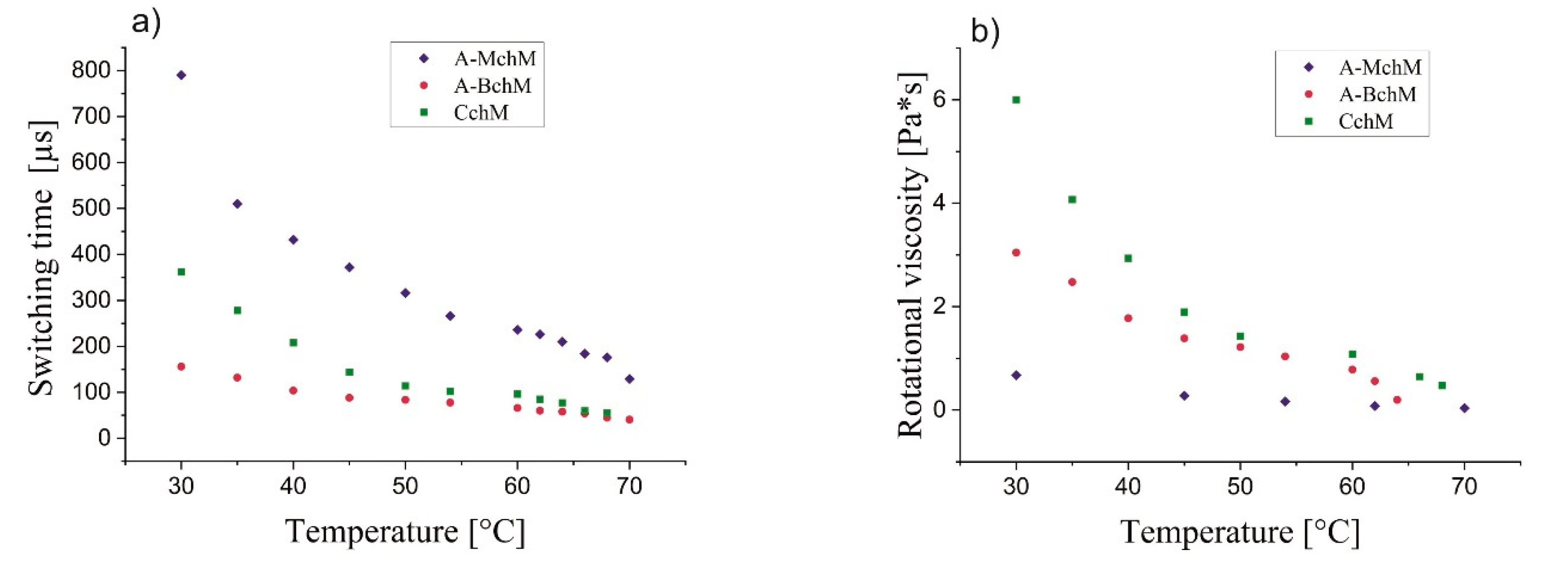

3.4. Switching Time and Rotational Viscosity

The switching times between the two synclinic states increase with decreasing temperature for all selected mixtures; the most pronounced effect was observed for mixture A-MchM and the lowest one for mixture A-BchM (

Figure 6a). Among examined systems, mixture A-BchM exhibits the shortest switching times across the entire temperature range, while mixture A-MchM shows the longest ones. Interestingly, the complex chiral mixture (CchM) demonstrates an intermediate switching behaviour, being slower than the achiral–bichiral mixture but faster than the achiral–monochiral mixture. Given that CchM also exhibits the highest rotational viscosity among the three selected mixtures (

Figure 6b), this finding suggests a complex interplay between viscosity and spontaneous polarization in the studied systems.

4. Conclusions

A systematic approach was employed to design and characterize new multicomponent FLC materials by leveraging three primary eutectic base formulations: an achiral mixture (AchM), a monochiral mixture (MchM), and a bichiral mixture (BchM). Subsequently, binary and ternary LC systems were developed by combining these base mixtures in controlled composition, followed by comprehensive investigations into their mesomorphic behaviour. As a result, the three best multicomponent mixtures were selected, and their mesomorphic and electro-optical characteristics were investigated.

The findings reveal several critical trends in the mesomorphic behaviour of studied LC systems. First, the introduction of chiral components—up to a 0.2 weight fraction—consistently expands the temperature range of the ferroelectric phase and simultaneously lowers the melting temperature across all developed mixtures. The mixture composed of compounds with two chiral centres exhibits a significantly shorter helical pitch compared to those containing one chiral centre. The mixture incorporating compounds with three different degrees of chirality exhibits significantly higher tilt angles compared to those containing only mono- or bichiral components. A similar tendency is observed for spontaneous polarization behavior, which generally increases with chiral content. The longest switching times are observed in systems composed of achiral compounds and those containing only a single chiral centre, which can be attributed to their higher viscosity and lower spontaneous polarization. In contrast, the achiral–bichiral mixture exhibits the shortest switching times due to the significantly enhanced spontaneous polarization.

Comprehensive results presented in

Table 6 indicate that the two mixtures incorporating bichiral compounds are the most promising candidates for applications utilizing the DHFLC effect. Particularly noteworthy is the mixture containing achiral, monochiral, and bichiral components, as it possesses the lowest reported melting temperature among FLC mixtures developed for the DHFLC effect. This feature extends the operational range of the ferroelectric phase to significantly lower temperatures, enabling DHFLC functionality well below 0°C—a capability critical for next-generation low-temperature photonic devices. The primary limitation of this system is its relatively high rotational viscosity, which may contribute to slower switching times but still faster than electro-optical systems-based nematic LCs.

These findings establish a robust framework for further design of new liquid crystalline materials with precisely predicted ferroelectric properties, thereby opening new avenues for fast-switching photonic devices and adaptive optical systems, particularly those operating at low temperatures.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org or from the author.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Cz. and D.W.; Methodology, M.Cz. and K.Ł.; Validation, M.Cz. and M.F.; Formal Analysis, M.F. and K.Ł; Investigation, M.Cz. and K.Ł.; Resources, D.W.; Data Curation, M.F. and K.Ł; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, M.CZ. and M.F.; Writing – Review & Editing, M.Cz., M.F. and D.W; Visualization, M.F. and K.Ł.; Supervision, M.Cz.; Project Administration, M.Cz. and D.W.; Funding Acquisition, M.Cz. and D.W.

Acknowledgments

All authors acknowledge the financial support from the MUT University grant UGB 22-026.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

References

- Lagerwall, J.P.F.; Giesselmann, F. Current Topics in Smectic Liquid Crystal Research. ChemPhysChem 2006, 7, 20–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, H.; Morris, S. Liquid-Crystal Lasers. Nat Photonics 2010, 4, 676–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagerwall, J.P.F.; Scalia, G. A New Era for Liquid Crystal Research: Applications of Liquid Crystals in Soft Matter Nano-, Bio- and Microtechnology. Current Applied Physics 2012, 12, 1387–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, V.; Panov, V.P.; Panov, A.; Rodriguez-Lojo, D.; Stevenson, P.J.; Gorecka, E.; Vij, J.K. Design and Electro-Optic Investigations of de Vries Chiral Smectic Liquid Crystals for Exhibiting Broad Temperature Ranges of SmA* and SmC* Phases and Fast Electro-Optic Switching. J Mater Chem C Mater 2020, 8, 4859–4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozhidaev, E.P.; Michie, A.; Ladouceur, F.; Guo, Q.; Chigrinov, V.; Silvestri, L.; Brodzeli, Z. Sensors at Your Fibre Tips: A Novel Liquid Crystal- Based Photonic Transducer for Sensing Systems. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2013, 31, 2940–2946. [Google Scholar]

- Al Abed, A.; Srinivas, H.; Firth, J.; Ladouceur, F.; Lovell, N.H.; Silvestri, L. A Biopotential Optrode Array: Operation Principles and Simulations. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Abed, A.; Wei, Y.; Almasri, R.M.; Lei, X.; Wang, H.; Firth, J.; Chen, Y.; Gouailhardou, N.; Silvestri, L.; Lehmann, T.; et al. Liquid Crystal Electro-Optical Transducers for Electrophysiology Sensing Applications. J Neural Eng 2022, 19, 056031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizawa, A. Ferroelectric Smectic Liquid Crystals. Crystals (Basel) 2024, 14, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Han, J.; Yang, L.; Li, J.; Song, Z.; Wang, T.; Zhu, J. Advanced Liquid Crystal-Based Switchable Optical Devices for Light Protection Applications: Principles and Strategies. Light Sci Appl 2023, 12, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, N.A.; Lagerwall, S.T. Submicrosecond Bistable Electro-optic Switching in Liquid Crystals. Appl Phys Lett 1980, 36, 899–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabadda, E.; Bennis, N.; Czerwinski, M.; Walewska, A.; Jaroszewicz, L.R.; Sánchez-López, M. del M.; Moreno, I. Ferroelectric Liquid-Crystal Modulator with Large Switching Rotation Angle for Polarization-Independent Binary Phase Modulation. Opt Lasers Eng 2022, 159, 107204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamplová, V.; Bubnov, A.; Kas˘par, M.; Novotná, V.; Glogarová, M.; Hamplova´, V.H.; Bubnov, H.A.; Kas, M.; Par, ˘; Novotnaánd, V. ; et al. New Series of Chiral Ferroelectric Liquid Crystals with the Keto Group Attached to the Molecule Core. Liq Cryst 2003, 30, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubnov, A.; Novotná, V.; Hamplová, V.; Kašpar, M.; Glogarová, M. Effect of Multilactate Chiral Part of Liquid Crystalline Molecule on Mesomorphic Behaviour. J Mol Struct 2008, 892, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitas, J.; Marzec, M.; Kurp, K.; Żurowska, M.; Tykarska, M.; Bubnov, A. Electro-Optic and Dielectric Properties of New Binary Ferroelectric and Antiferroelectric Liquid Crystalline Mixtures. Liq Cryst 2017, 44, 1468–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubnov, A.; Podoliak, N.; Hamplová, V.; Tomášková, P.; Havlíček, J.; Kašpar, M. Eutectic Behaviour of Binary Mixtures Composed of Two Isomeric Lactic Acid Derivatives. Ferroelectrics 2016, 495, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Das, M.K.; Bubnov, A.; Weissflog, W.; Wȩgłowska, D.; Dabrowski, R. Induced Frustrated Twist Grain Boundary Liquid Crystalline Phases in Binary Mixtures of Achiral Hockey Stick-Shaped and Chiral Rod-like Materials. J Mater Chem C Mater 2019, 7, 10530–10543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tykarska, M.; Kurp, K.; Zieja, P.; Herman, J.; Stulov, S.; Bubnov, A. New Quaterphenyls Laterally Substituted by Methyl Group and Their Influence on the Self-Assembling Behaviour of Ferroelectric Bicomponent Mixtures. Liq Cryst 2022, 49, 821–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wȩgłowska, D.; Perkowski, P.; Chrunik, M.; Czerwiński, M. The Effect of Dopant Chirality on the Properties of Self-Assembling Materials with a Ferroelectric Order. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2018, 20, 9211–9220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalik, S.; Deptuch, A.; Fryń, P.; Jaworska-Gołąb, T.; Węgłowska, D.; Marzec, M. Physical Properties of New Binary Ferroelectric Mixture. J Mol Liq 2019, 274, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Vijaya Prakash, G.; Kaur, S.; Choudhary, A.; Biradar, A.M. Molecular Relaxation in Homeotropically Aligned Ferroelectric Liquid Crystals. Physica B Condens Matter 2008, 403, 3316–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurp, K.; Czerwiński, M.; Tykarska, M.; Salamon, P.; Bubnov, A. Design of Functional Multicomponent Liquid Crystalline Mixtures with Nano-Scale Pitch Fulfilling Deformed Helix Ferroelectric Mode Demands. J Mol Liq 2019, 290, 111329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żurowska, M.; Dziaduszek, J.; Szala, M.; Morawiak, P.; Bubnov, A. Effect of Lateral Fluorine Substitution Far from the Chiral Center on Mesomorphic Behaviour of Highly Titled Antiferroelectric (S) and (R) Enantiomers. J Mol Liq 2018, 267, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubnov, A.; Domenici, V.; Hamplov, V.; Kapar, M.; Veracini, C.A.; Glogarov, M. Orientational and Structural Properties of Ferroelectric Liquid Crystal with a Broad Temperature Range Inthe SmC* Phase by 13C NMR, x-Ray Scattering and Dielectric Spectroscopy. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2008, 21, 035102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbańska, M.; Zając, M.; Czerwiński, M.; Morawiak, P.; Bubnov, A.; Deptuch, A. Synthesis and Properties of Highly Tilted Antiferroelectric Liquid Crystalline (R) Enantiomers. Materials 2024, 17, 4967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimal, T.; Pandey, S.; Gupta, S.K.; Singh, D.P.; Agrahari, K.; Pathak, G.; Kumar, S.; Tripathi, P.K.; Manohar, R. Manifestation of Strong Magneto-Electric Dipolar Coupling in Ferromagnetic Nanoparticles−FLC Composite: Evaluation of Time-Dependent Memory Effect. Liq Cryst 2018, 45, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.P.; Boussoualem, Y.; Duponchel, B.; Hadj Sahraoui, A.; Kumar, S.; Manohar, R.; Daoudi, A. Pico-Ampere Current Sensitivity and CdSe Quantum Dots Assembly Assisted Charge Transport in Ferroelectric Liquid Crystal. J Phys D Appl Phys 2017, 50, 325301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrahari, K.; Vimal, T.; Rastogi, A.; Pandey, K.K.; Gupta, S.; Kurp, K.; Manohar, R. Ferroelectric Liquid Crystal Mixture Dispersed with Tin Oxide Nanoparticles: Study of Morphology, Thermal, Dielectric and Optical Properties. Mater Chem Phys 2019, 237, 121851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, A.K.; Roy, A.; Pratap Singh, B.; Pandey, K.K.; Shrivas, R.; Saluja, J.K.; Tripathi, P.K.; Manohar, R. Influence of SiO2 Nanoparticles on the Dielectric Properties and Anchoring Energy Parameters of Pure Ferroelectric Liquid Crystal. J Dispers Sci Technol 2020, 41, 2136–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimal, T.; Pujar, G.H.; Agrahari, K.; Inamdar, S.R.; Manohar, R. Nanoparticle Surface Energy Transfer (NSET) in Ferroelectric Liquid Crystal-Metallic-Silver Nanoparticle Composites: Effect of Dopant Concentration on NSET Parameters. Phys Rev E 2021, 103, 022708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beresnev, L.A.; Chigrinovs, V.G.; Dergachevt, D.I.; Poshidaev, E.P.; Fünfschilling, J.; Schadt, M. Deformed Helix Ferroelectric Liquid Crystal Display: A New Electrooptic Mode in Ferroelectric Chiral Smectic C Liquid Crystals. Liq Cryst 1989, 5, 1171–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozhidaev, E.; Chigrinov, V.; Murauski, A.; Molkin, V.; Tao, D.; Kwok, H.-S. V-Shaped Electro-Optical Mode Based on Deformed-Helix Ferroelectric Liquid Crystal with Subwavelength Pitch. J Soc Inf Disp 2012, 20, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, L.; Chen, Y.; Brodzeli, Z.; Sirojan, T.; Lu, S.; Liu, Z.; Phung, T.; Ladouceur, F. A Novel Optical Sensing Technology for Monitoring Voltage and Current of Overhead Power Lines. IEEE Sens J 2021, 21, 26699–26707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Silvestri, L.; Lei, X.; Ladouceur, F. Optically Powered Gas Monitoring System Using Single-Mode Fibre for Underground Coal Mines. Int J Coal Sci Technol 2022, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailenko, V.; Krivoshey, A.; Pozhidaev, E.; Popova, E.; Fedoryako, A.; Gamzaeva, S.; Barbashov, V.; Srivastava, A.K.; Kwok, H.S.; Vashchenko, V. The Nano-Scale Pitch Ferroelectric Liquid Crystal Materials for Modern Display and Photonic Application Employing Highly Effective Chiral Components: Trifluoromethylalkyl Diesters of p-Terphenyldicarboxylic Acid. J Mol Liq 2019, 281, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwiński, M.; Gaładyk, K.; Morawiak, P.; Piecek, W.; Chrunik, M.; Kurp, K.; Kula, P.; Jaroszewicz, L.R. Pyrimidine-Based Ferroelectric Mixtures – The Influence of Oligophenyl Based Chiral Doping System. J Mol Liq 2020, 303, 112693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotova, S.P.; Pozhidaev, E.P.; Samagin, S.A.; Kesaev, V. V.; Barbashov, V.A.; Torgova, S.I. Ferroelectric Liquid Crystal with Sub-Wavelength Helix Pitch as an Electro-Optical Medium for High-Speed Phase Spatial Light Modulators. Opt Laser Technol 2021, 135, 106711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurp, K.; Czerwiński, M.; Tykarska, M.; Bubnov, A. Design of Advanced Multicomponent Ferroelectric Liquid Crystalline Mixtures with Submicrometre Helical Pitch. Liq Cryst 2017, 44, 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubnov, A.; Vacek, C.; Czerwiński, M.; Vojtylová, T.; Piecek, W.; Hamplová, V. Design of Polar Self-Assembling Lactic Acid Derivatives Possessing Submicrometre Helical Pitch. Beilstein Journal of Nanotechnology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitas, J.; Marzec, M.; Szymkowiak, M.; Jaworska-Gołąb, T.; Deptuch, A.; Tykarska, M.; Kurp, K.; Żurowska, M.; Bubnov, A. Mesomorphic, Electro-Optic and Structural Properties of Binary Liquid Crystalline Mixtures with Ferroelectric and Antiferroelectric Liquid Crystalline Behaviour. Phase Transitions 2018, 91, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmini, V.; Babu, P.N.; Nair, G.G.; Rao, D.S.S.; Yelamaggad, C. V. Optically Biaxial, Re-Entrant and Frustrated Mesophases in Chiral, Non-Symmetric Liquid Crystal Dimers and Binary Mixtures. Chem Asian J 2016, 11, 2897–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węgłowska, D.; Chen, Y.; Ladouceur, F.; Silvestri, L.; Węgłowski, R.; Czerwiński, M. Single Ferroelectric Liquid Crystal Compounds Targeted for Optical Voltage Sensing. J Mol Liq 2024, 399, 124454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tykarska, M.; Dbrowski, R.; Czerwiński, M.; Chełstowska, A.; Piecek, W.; Morawiak, P. The Influence of the Chiral Terphenylate on the Tilt Angle in Pyrimidine Ferroelectric Mixtures. Phase Transitions 2012, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowiorski, K.; Kedzierski, J.; Raszewski, Z.; Kojdecki, M.A.; Chojnowska, O.; Garbat, K.; Miszczyk, E.; Piecek, W. Complementary Interference Method for Determining Optical Parameters of Liquid Crystals. Phase Transitions 2016, 89, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahr, C.H.; Heppke, G. Optical and Dielectric Investigations on the Electroclinic Effect Exhibited by a Ferroelectric Liquid Crystal with High Spontaneous Polarization. Liq Cryst 1987, 2, 825–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyasato, K.; Abe, S.; Takezoe, H.; Fukuda, A.; Kuze, E. Direct Method with Triangular Waves for Measuring Spontaneous Polarization in Ferroelectric Liquid Crystals. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics, Part 2: Letters 1983, 22, 661–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarp, K. Rotational Viscosities in Ferroelectric Smectic Liquid Crystals. Ferroelectrics 1988, 84, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of molecular orientation leading to the formation of a heliconical structure in FLCs; it is characterized by helical pitch (p) and distinct handedness. The figure also highlights the molecular director (n), helix axis (z), tilt angle of the director (θ), and spontaneous polarization vector (Ps).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of molecular orientation leading to the formation of a heliconical structure in FLCs; it is characterized by helical pitch (p) and distinct handedness. The figure also highlights the molecular director (n), helix axis (z), tilt angle of the director (θ), and spontaneous polarization vector (Ps).

Figure 2.

A schematic representation illustrating the design concept for the studied FLC mixtures based on compounds with different degrees of chirality.

Figure 2.

A schematic representation illustrating the design concept for the studied FLC mixtures based on compounds with different degrees of chirality.

Figure 3.

Phase diagrams (data from DSC) for systems: AChM-MChM (a), AchM-BchM (b), A-MChM-BchM (c), and collected phase diagram with melting points and upper-temperature range of the SmC* phase (d). The compositions of mixture A-MChM, A-BChM, and CChM are marked with a purple arrow and a dashed line in each phase diagram. “Cr” stands for the crystal phase.

Figure 3.

Phase diagrams (data from DSC) for systems: AChM-MChM (a), AchM-BchM (b), A-MChM-BchM (c), and collected phase diagram with melting points and upper-temperature range of the SmC* phase (d). The compositions of mixture A-MChM, A-BChM, and CChM are marked with a purple arrow and a dashed line in each phase diagram. “Cr” stands for the crystal phase.

Figure 4.

Temperature dependence of the helical pitch length for all tested mixtures as indicated.

Figure 4.

Temperature dependence of the helical pitch length for all tested mixtures as indicated.

Figure 5.

Temperature dependence of the tilt angle (a) and the spontaneous polarization (b) for mixtures: A-MchM, A-BchM, and CchM.

Figure 5.

Temperature dependence of the tilt angle (a) and the spontaneous polarization (b) for mixtures: A-MchM, A-BchM, and CchM.

Figure 6.

Temperature dependence of the switching time (a) and rotational viscosity (b) for mixtures: A-MchM, A-BchM, and CchM.

Figure 6.

Temperature dependence of the switching time (a) and rotational viscosity (b) for mixtures: A-MchM, A-BchM, and CchM.

Table 1.

Composition of the base achiral mixture (AchM) [

35].

Table 2.

Composition of the base monochiral mixture (MchM), based on compounds with a single chiral centre [

41].

Table 2.

Composition of the base monochiral mixture (MchM), based on compounds with a single chiral centre [

41].

| Numbers of component |

Chemical formulae |

Weight Fraction |

| 11 |

|

0.52 |

| 12 |

|

0.48 |

Table 3.

Composition of the base bichiral mixture (BchM), based on compounds with two chiral centres [

42].

Table 3.

Composition of the base bichiral mixture (BchM), based on compounds with two chiral centres [

42].

| Numbers of component |

Chemical formulae |

Weight Fraction |

| 13 |

|

0.44 |

| 14 |

|

0.56 |

Table 4.

Designations and compositions of the developed mixtures incorporating compounds with varying degrees of chirality, categorized within three primary systems: MchM–AchM, AchM–BchM, and CchM–BchM.

Table 4.

Designations and compositions of the developed mixtures incorporating compounds with varying degrees of chirality, categorized within three primary systems: MchM–AchM, AchM–BchM, and CchM–BchM.

| |

Composition of the mixture (Weight Fraction) |

| Mixture Acronym |

AchM (Achiral Mixture) |

MchM (Monochiral Mixture |

BchM

(Bichiral Mixture) |

| 0.2 MchM + 0.8 AchM |

0.80 |

0.20 |

- |

| 0.4 MchM + 0.6 AchM (designated as A-MchM)

|

0.60 |

0.40 |

- |

| 0.5 MchM + 0.5 AchM |

0.50 |

0.50 |

- |

| 0.6 MchM + 0.4 AchM |

0.40 |

0.60 |

- |

| 0.8 MchM + 0.2 AchM |

0.20 |

0.80 |

- |

| 0.05 BchM + 0.95 AchM |

0.95 |

- |

0.05 |

| 0.2 BchM + 0.8 AchM |

0.80 |

- |

0.20 |

| 0.4BchM + 0.6 AchM (designated as A-BchM)

|

0.60 |

- |

0.40 |

| 0.4 A-MchM + 0.6 BchM |

0.24 |

0.16 |

0.60 |

| 0.6 A-MchM + 0.4 BchM (designated as CchM) |

0.36 |

0.24 |

0.40 |

| 0.8 A-MchM + 0.2 BchM |

0.48 |

0.32 |

0.20 |

| 0.9 A-MchM + 0.1 BchM |

0.54 |

0.36 |

0.10 |

| 0.95 A-MchM + 0.05 BchM |

0.57 |

0.38 |

0.05 |

Table 5.

The phase transition temperatures [°C] from DSC (first row), and corresponding enthalpy changes [kJ mol-1] (second row), in italic font, of the selected FLC mixtures determined during heating.

Table 5.

The phase transition temperatures [°C] from DSC (first row), and corresponding enthalpy changes [kJ mol-1] (second row), in italic font, of the selected FLC mixtures determined during heating.

| Mixture acronym |

Cr |

▪ |

SmC* |

▪ |

SmA* |

▪ |

N* |

▪ |

Iso |

| A-MchM |

▪ |

4.2

11.74

|

▪ |

70.2#

- |

▪ |

73.6#

- |

▪ |

74.5

5.58

|

▪ |

| A-BchM |

▪ |

-12.6

7.28

|

▪ |

64.3#

- |

▪ |

73.5

4.89

|

- |

- |

▪ |

| CchM |

▪ |

-24.1

1.88

|

▪ |

62.9#

- |

▪ |

65.2

3.11

|

- |

- |

▪ |

Table 6.

Temperature range of ferroelectric phase and collected electro-optical and physicochemical properties for investigated mixtures at T =30 °C.

Table 6.

Temperature range of ferroelectric phase and collected electro-optical and physicochemical properties for investigated mixtures at T =30 °C.

| Mixture Acronym |

Temperature Rangeof SmC* [°C] |

Properties at 30°C |

p

[nm] |

θ[°] |

PS

[nC/cm2] |

τ

[μs] |

γφ

[Pa*s] |

| A-MchM |

4.2 <SmC*> 74.5 |

>1000 |

34.0 |

11 |

790 |

0.67 |

| A-BchM |

-12.6 <SmC*> 82.4 |

80.5 |

34.5 |

255 |

156 |

3.04 |

| CchM |

-24.1 <SmC*> 67.2 |

<120 |

36.0 |

217 |

362 |

6.00 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).