Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

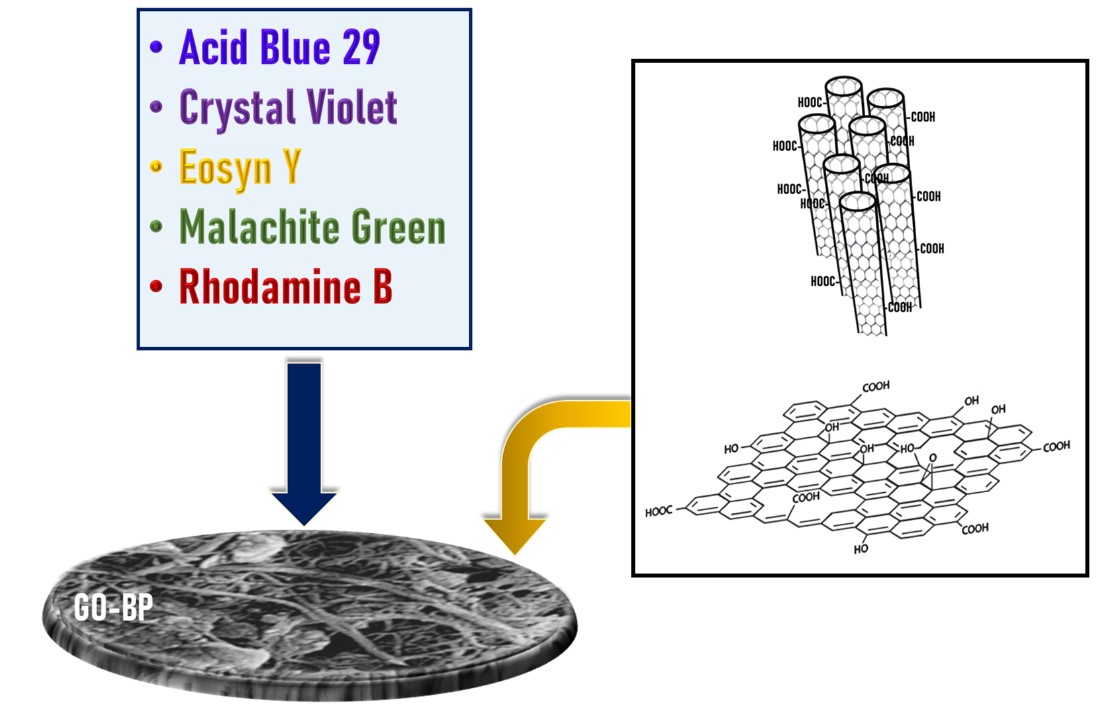

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Buckypaper (GO-BP) Preparation

2.3. Batch Studies for Dyes Adsorption

2.4. Characterizations

3. Results

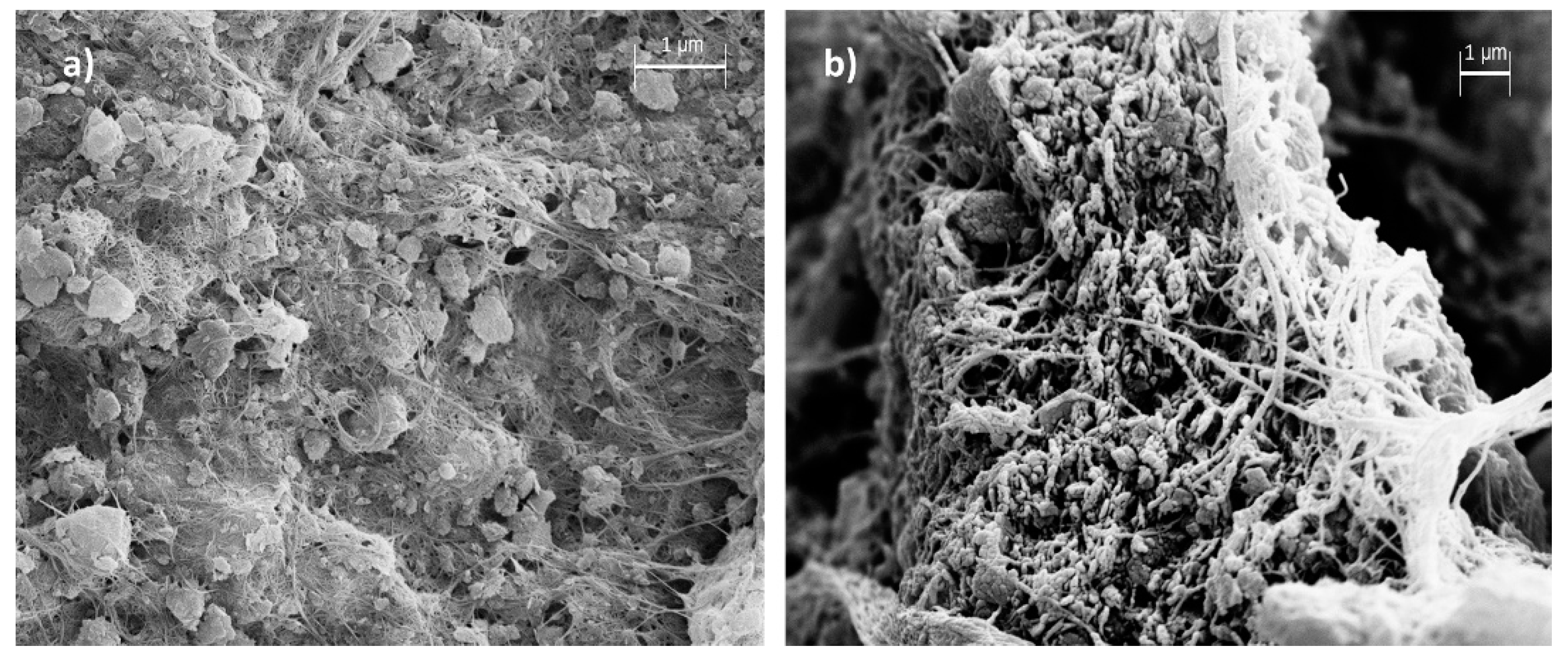

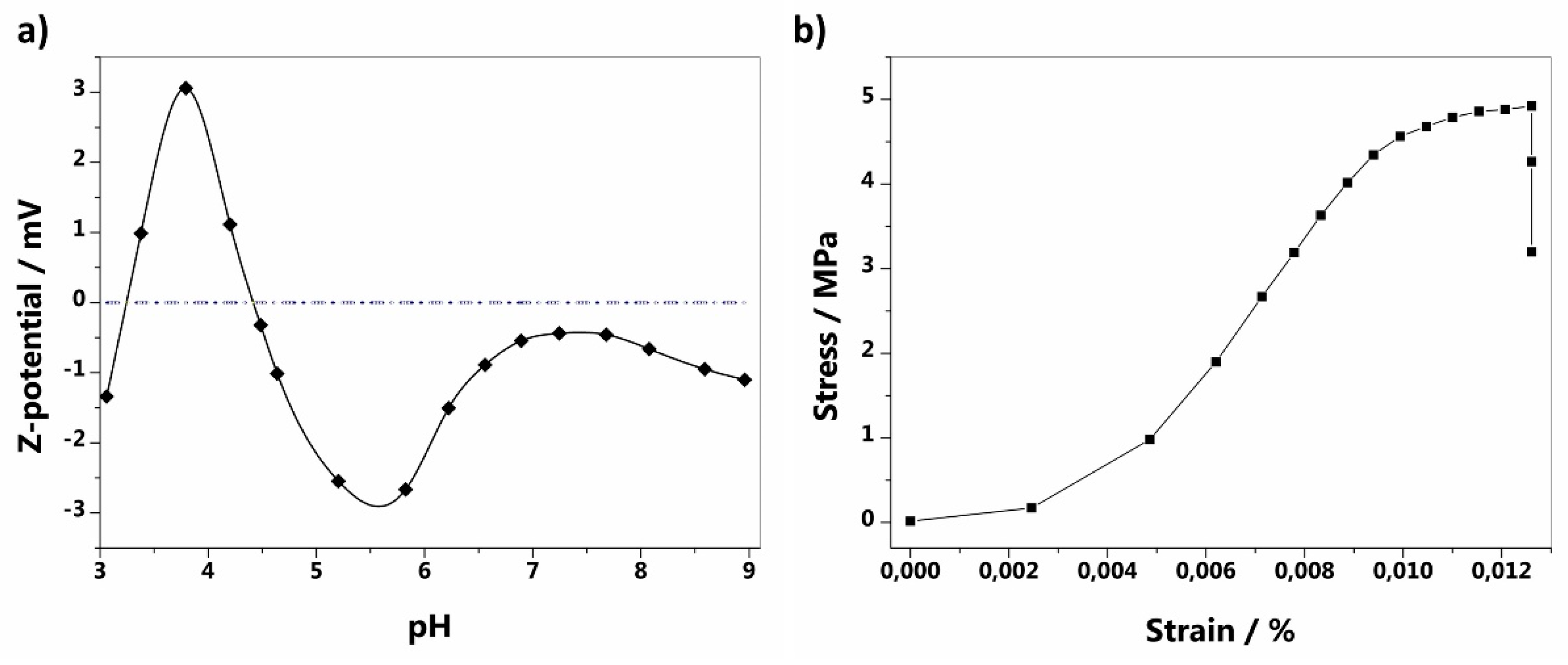

3.1. GO-BPs Characterization

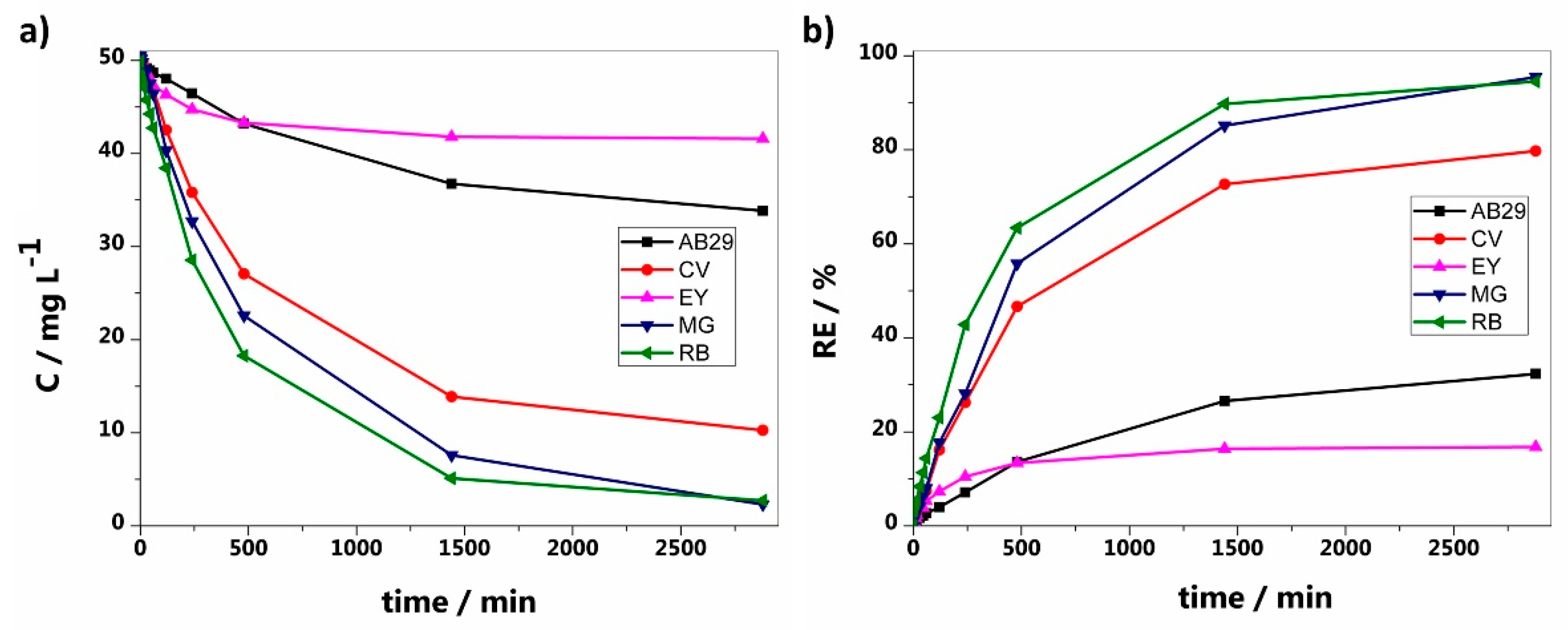

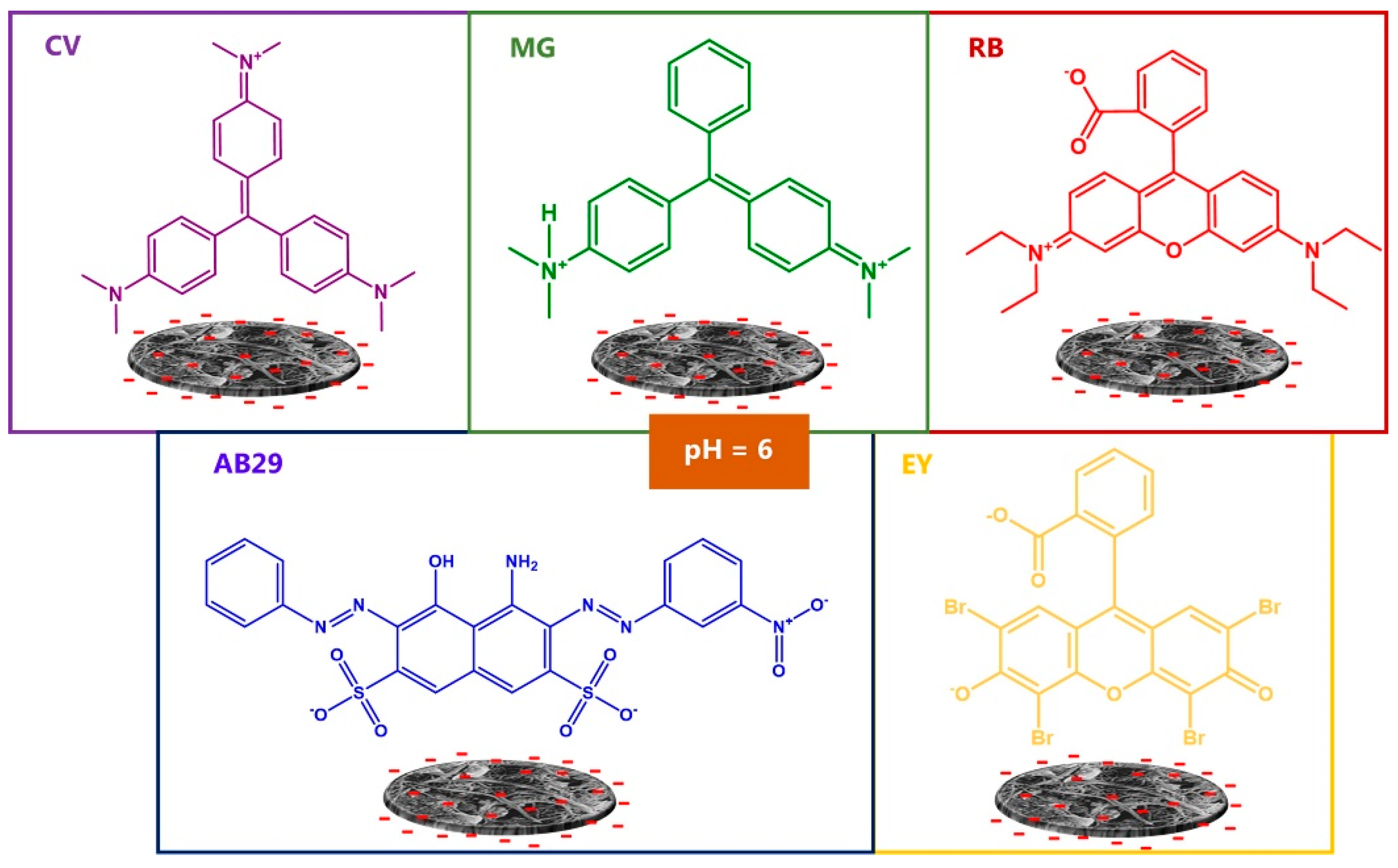

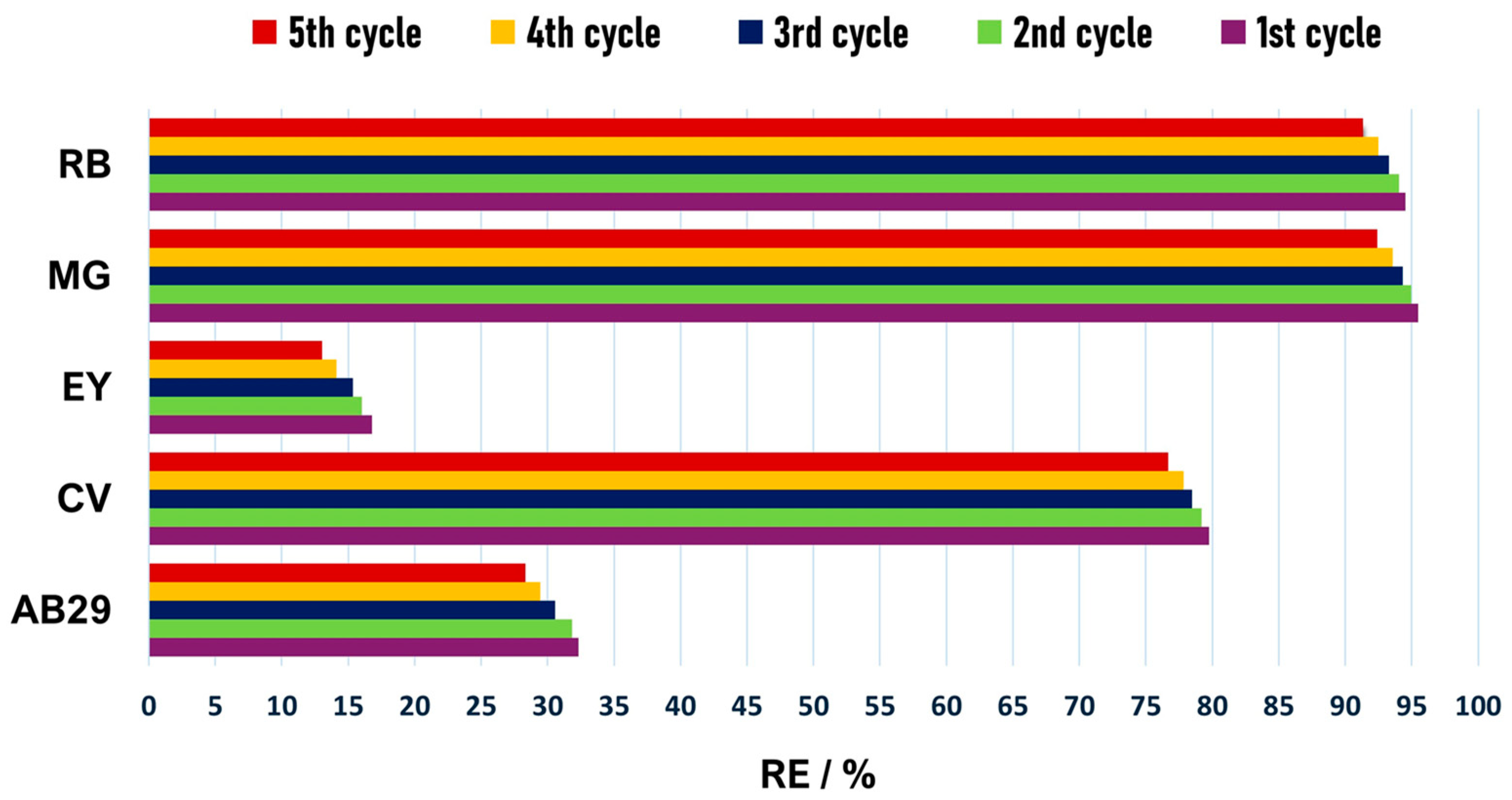

3.2. Dyes Adsorption

3.1. Comparison with Other Adsorbents

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SWCNT-BP | single-walled carbon nanotube buckypaper |

| MWCNTs | multi-walled carbon nanotubes |

| GO | graphene oxide |

| BP | buckypaper |

| AB29 | acid blue 29 |

| CV | crystal violet |

| EY | eosyn Y |

| MG | malachite green |

| RB | rhodamine B |

References

- United Nations Organization The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGS); 2024;

- Islam, T.; Repon, M.R.; Islam, T.; Sarwar, Z.; Rahman, M.M. Impact of Textile Dyes on Health and Ecosystem: A Review of Structure, Causes, and Potential Solutions; Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2023; Vol. 30; ISBN 0123456789.

- IMARC Report Textile Market by Raw Material, Product, Application, and Region 2025-2033; 2025;

- Goswami, D.; Mukherjee, J.; Mondal, C.; Bhunia, B. Bioremediation of Azo Dye: A Review on Strategies, Toxicity Assessment, Mechanisms, Bottlenecks and Prospects. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176426. [CrossRef]

- Berradi, M.; Hsissou, R.; Khudhair, M.; Assouag, M.; Cherkaoui, O.; El Bachiri, A.; El Harfi, A. Textile Finishing Dyes and Their Impact on Aquatic Environs. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02711. [CrossRef]

- Al-Tohamy, R.; Ali, S.S.; Li, F.; Okasha, K.M.; Mahmoud, Y.A.G.; Elsamahy, T.; Jiao, H.; Fu, Y.; Sun, J. A Critical Review on the Treatment of Dye-Containing Wastewater: Ecotoxicological and Health Concerns of Textile Dyes and Possible Remediation Approaches for Environmental Safety. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 231, 113160. [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, V.K.; Shirin, S.; Aman, A.M.; de Solla, S.R.; Mathieu-Denoncourt, J.; Langlois, V.S. Genotoxic and Carcinogenic Products Arising from Reductive Transformations of the Azo Dye, Disperse Yellow 7. Chemosphere 2016, 146, 206–215. [CrossRef]

- Solayman, H.M.; Hossen, M.A.; Abd Aziz, A.; Yahya, N.Y.; Leong, K.H.; Sim, L.C.; Monir, M.U.; Zoh, K.D. Performance Evaluation of Dye Wastewater Treatment Technologies: A Review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109610. [CrossRef]

- Chethana, M.; Sorokhaibam, L.G.; Bhandari, V.M.; Raja, S.; Ranade, V. V. Green Approach to Dye Wastewater Treatment Using Biocoagulants. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 2495–2507. [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, R.; Joshi, H.; Mall, I.D.; Srivastava, V.C. Electrochemical Treatment of Acrylic Dye-Bearing Textile Wastewater: Optimization of Operating Parameters. Desalin. Water Treat. 2014, 52, 111–122. [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, L.; Elcik, H.; Blankert, B.; Ghaffour, N.; Vrouwenvelder, J. Textile Dye Wastewater Treatment by Direct Contact Membrane Distillation: Membrane Performance and Detailed Fouling Analysis. J. Memb. Sci. 2021, 636, 119552. [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.K.H.; Tan, H.K.; Lau, S.Y.; Yap, P.S.; Danquah, M.K. Potential and Challenges of Enzyme Incorporated Nanotechnology in Dye Wastewater Treatment: A Review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103261. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, R.; Shafiq, I.; Akhter, P.; Iqbal, M.J.; Hussain, M. A State-of-the-Art Review on Wastewater Treatment Techniques: The Effectiveness of Adsorption Method. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 9050–9066. [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Wu, D.; Yu, J.; Gao, T.; Guo, L.; Li, F. Upgraded β-Cyclodextrin-Based Broad-Spectrum Adsorbents with Enhanced Antibacterial Property for High-Efficient Dyeing Wastewater Remediation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 461, 132610. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Sun, Y.; Liu, W.; Pan, F.; Sun, P.; Fu, J. An Overview of Nanomaterials Applied for Removing Dyes from Wastewater. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 15882–15904. [CrossRef]

- Baratta, M.; Nezhdanov, A.V.; Mashin, A.I.; Nicoletta, F.P.; De Filpo, G. Carbon Nanotubes Buckypapers: A New Frontier in Wastewater Treatment Technology. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171578. [CrossRef]

- Umesh, A.S.; Puttaiahgowda, Y.M.; Thottathil, S. Enhanced Adsorption: Reviewing the Potential of Reinforcing Polymers and Hydrogels with Nanomaterials for Methylene Blue Dye Removal. Surfaces and Interfaces 2024, 51, 104670. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.; Kumar, A.; Singh, A. Adsorptive Removal of Heavy Metals, Dyes, and Pharmaceuticals: Carbon-Based Nanomaterials in Focus. Carbon N. Y. 2024, 217, 118621. [CrossRef]

- Baratta, M.; Tursi, A.; Curcio, M.; Cirillo, G.; Nezhdanov, A.V.; Mashin, A.I.; Nicoletta, F.P.; De Filpo, G. Removal of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs from Drinking Water Sources by GO-SWCNT Buckypapers. Molecules 2022, 27, 7674. [CrossRef]

- De Filpo, G.; Pantuso, E.; Mashin, A.I.; Baratta, M.; Nicoletta, F.P. WO3/Buckypaper Membranes for Advanced Oxidation Processes. Membranes (Basel). 2020, 10, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Baratta, M.; Nezhdanov, A.V.; Ershov, A.V.; Aiello, D.; Napoli, A.; Donna, L. Di; Mashin, A.I.; Nicoletta, F.P.; Filpo, G. De Improving the Catalytic Performance of TiO 2 by Its Surface Deposition on CNT Buckypapers for Use in the Removal of Wastewater Pollutants. New Carbon Mater. 2025, 40, 438–455. [CrossRef]

- Tursi, A.; Mastropietro, T.F.; Bruno, R.; Baratta, M.; Ferrando-Soria, J.; Mashin, A.I.; Nicoletta, F.P.; Pardo, E.; De Filpo, G.; Armentano, D. Synthesis and Enhanced Capture Properties of a New BioMOF@SWCNT-BP: Recovery of the Endangered Rare-Earth Elements from Aqueous Systems. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 8, 2100730. [CrossRef]

- Baratta, M.; Mastropietro, T.F.; Bruno, R.; Tursi, A.; Negro, C.; Ferrando-Soria, J.; Mashin, A.I.; Nezhdanov, A.; Nicoletta, F.P.; De Filpo, G.; et al. Multivariate Metal-Organic Framework/Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Buckypaper for Selective Lead Decontamination. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 5223–5233. [CrossRef]

- Baratta, M.; Mastropietro, T.F.; Escamilla, P.; Algieri, V.; Xu, F.; Nicoletta, F.P.; Ferrando-Soria, J.; Pardo, E.; De Filpo, G.; Armentano, D. Sulfur-Functionalized Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Buckypaper/MTV-BioMetal-Organic Framework Nanocomposites for Gold Recovery. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 18992−19001. [CrossRef]

- Baratta, M.; Tursi, A.; Curcio, M.; Cirillo, G.; Nicoletta, F.P.; De Filpo, G. GO-SWCNT Buckypapers as an Enhanced Technology for Water Decontamination from Lead. Molecules 2022, 27, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Chun, M.S.; Lee, S.Y.; Yang, S.M. Estimation of Zeta Potential by Electrokinetic Analysis of Ionic Fluid Flows through a Divergent Microchannel. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003, 266, 120–126. [CrossRef]

- Akrami, M.; Danesh, S.; Eftekhari, M. Comparative Study on the Removal of Cationic Dyes Using Different Graphene Oxide Forms. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2019, 29, 1785–1797. [CrossRef]

- Bradder, P.; Ling, S.K.; Wang, S.; Liu, S. Dye Adsorption on Layered Graphite Oxide. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2011, 56, 138–141. [CrossRef]

- Minitha, C.R.; Lalitha, M.; Jeyachandran, Y.L.; Senthilkumar, L.; Rajendra Kumar, R.T. Adsorption Behaviour of Reduced Graphene Oxide towards Cationic and Anionic Dyes: Co-Action of Electrostatic and π – π Interactions. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2017, 194, 243–252. [CrossRef]

- Konicki, W.; Aleksandrzak, M.; Mijowska, E. Equilibrium, Kinetic and Thermodynamic Studies on Adsorption of Cationic Dyes from Aqueous Solutions Using Graphene Oxide. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2017, 123, 35–49. [CrossRef]

- Narayanaswamy, V.; Alaabed, S.; Al-Akhras, M.A.; Obaidat, I.M. Molecular Simulation of Adsorption of Methylene Blue and Rhodamine B on Graphene and Graphene Oxide for Water Purification. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 28, 1078–1083. [CrossRef]

- Ramesha, G.K.; Vijaya Kumara, A.; Muralidhara, H.B.; Sampath, S. Graphene and Graphene Oxide as Effective Adsorbents toward Anionic and Cationic Dyes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 361, 270–277. [CrossRef]

- Sedeño-Díaz, J.; Eugenia, L.; Mendoza-mart, E.; Joseph, A.; Soledad, S. Distribution Coefficient and Metal Pollution Index in Water and Sediments: Proposal of a New Index for Ecological Risk Assessment of Metals. Water (Switzerland) 2019, 12, 1–20, doi:doi:10.3390/w12010029.

- Wang, J.; Guo, X. Adsorption Kinetic Models: Physical Meanings, Applications, and Solving Methods. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 390, 122156. [CrossRef]

- Veerakumar, P.; Tharini, J.; Ramakrishnan, M.; Panneer Muthuselvam, I.; Lin, K.C. Graphene Oxide Nanosheets as An Efficient and Reusable Sorbents for Eosin Yellow Dye Removal from Aqueous Solutions. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 3598–3607. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Karim, S.; Hussain, D.; Mok, Y.S.; Siddiqui, G.U. Efficient Dual Adsorption of Eosin Y and Methylene Blue from Aqueous Solution Using Nanocomposite of Graphene Oxide Nanosheets and ZnO Nanospheres. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 39, 3155–3164. [CrossRef]

- Ciesielczyk, F.; Bartczak, P.; Zdarta, J.; Jesionowski, T. Active MgO-SiO2 Hybrid Material for Organic Dye Removal: A Mechanism and Interaction Study of the Adsorption of C.I. Acid Blue 29 and C.I. Basic Blue 9. J. Environ. Manage. 2017, 204, 123–135. [CrossRef]

- Marrakchi, F.; Bouaziz, M.; Hameed, B.H. Adsorption of Acid Blue 29 and Methylene Blue on Mesoporous K2CO3-Activated Olive Pomace Boiler Ash. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2017, 535, 157–165. [CrossRef]

- Nandi, B.K.; Goswami, A.; Das, A.K.; Mondal, B.; Purkait, M.K. Kinetic and Equilibrium Studies on the Adsorption of Crystal Violet Dye Using Kaolin as an Adsorbent. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2008, 43, 1382–1403. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Das Saha, P. Adsorption of Crystal Violet from Aqueous Solution onto NaOH-Modified Rice Husk. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 86, 1533–1541. [CrossRef]

- Sabna, V.; Thampi, S.G.; Chandrakaran, S. Adsorption of Crystal Violet onto Functionalised Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes: Equilibrium and Kinetic Studies. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016, 134, 390–397. [CrossRef]

- Puri, C.; Sumana, G. Highly Effective Adsorption of Crystal Violet Dye from Contaminated Water Using Graphene Oxide Intercalated Montmorillonite Nanocomposite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2018, 166, 102–112. [CrossRef]

- Adeoye, J.B.; Balogun, D.O.; Etemire, O.J.; Ezeh, P.N.; Tan, Y.H.; Mubarak, N.M. Rapid Adsorptive Removal of Eosin Yellow and Methyl Orange Using Zeolite Y. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.K.; Dhakate, S.R.; Pratap Singh, B. Carbon Nanotube Incorporated Eucalyptus Derived Activated Carbon-Based Novel Adsorbent for Efficient Removal of Methylene Blue and Eosin Yellow Dyes. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126231. [CrossRef]

- Altintig, E.; Onaran, M.; Sarı, A.; Altundag, H.; Tuzen, M. Preparation, Characterization and Evaluation of Bio-Based Magnetic Activated Carbon for Effective Adsorption of Malachite Green from Aqueous Solution. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018, 220, 313–321. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, T.; Meng, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Lu, J.; Wang, H. Novel Graphene Oxide/Aminated Lignin Aerogels for Enhanced Adsorption of Malachite Green in Wastewater. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 603, 125281. [CrossRef]

- Khawaja, H.; Zahir, E.; Asghar, M.A.; Asghar, M.A. Graphene Oxide Decorated with Cellulose and Copper Nanoparticle as an Efficient Adsorbent for the Removal of Malachite Green. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 167, 23–34. [CrossRef]

- Shirmardi, M.; Mahvi, A.H.; Hashemzadeh, B.; Naeimabadi, A.; Hassani, G.; Niri, M.V. The Adsorption of Malachite Green (MG) as a Cationic Dye onto Functionalized Multi Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2013, 30, 1603–1608. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Khatri, O.P. Reduced Graphene Oxide as an Effective Adsorbent for Removal of Malachite Green Dye: Plausible Adsorption Pathways. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 501, 11–21. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Duan, X.; Srinivasakannan, C.; Liang, J. Preparation of Magnesium Silicate/Carbon Composite for Adsorption of Rhodamine B. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 7873–7882. [CrossRef]

- Neelaveni, M.; Santhana Krishnan, P.; Ramya, R.; Sonia Theres, G.; Shanthi, K. Montmorillonite/Graphene Oxide Nanocomposite as Superior Adsorbent for the Adsorption of Rhodamine B and Nickel Ion in Binary System. Adv. Powder Technol. 2019, 30, 596–609. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Murthy, B.N.; Shapter, J.G.; Constantopoulos, K.T.; Voelcker, N.H.; Ellis, A. V. Benzene Carboxylic Acid Derivatized Graphene Oxide Nanosheets on Natural Zeolites as Effective Adsorbents for Cationic Dye Removal. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 260, 330–338. [CrossRef]

- Oyetade, O.A.; Nyamori, V.O.; Martincigh, B.S.; Jonnalagadda, S.B. Effectiveness of Carbon Nanotube-Cobalt Ferrite Nanocomposites for the Adsorption of Rhodamine B from Aqueous Solutions. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 22724–22739. [CrossRef]

| Dye | LogKD | Maximun adsorption capacity (mg g-1) | 1st order kinetic constant (min-1) | R2 |

| AB29 | 3.58 | 129.31 | 0.0004 ± 0.0001 | 0.9906 |

| CV | 4.50 | 323.74 | 0.0013 ± 0.0004 | 0.9972 |

| EY | 3.21 | 67.09 | 0.0011 ± 0.0003 | 0.9776 |

| MG | 5.23 | 390.17 | 0.0017 ± 0.0004 | 0.9968 |

| RB | 5.14 | 377.53 | 0.0021 ± 0.0006 | 0.9974 |

| Dye | Adsorbent typology | Adsorbent dose /(mg) | pH | Cdye/ (mg L-1) | Cmax / (mg g-1) | Ref. |

| AB29 | MgO-SiO2 | 500 | 10 | 100 | 44.9 | [37] |

| K2CO3-activated olive pomace boiler ash | 300 | 6 | 100 | 38.48 | [38] | |

| GO-BP | 50 | 6 | 100 | 162.65 | This work | |

| CV | Kaolin | 100 | 7 | 100 | 45.0 | [39] |

| NaOH-modified rice husk | 1000 | 7 | 50 | 44.87 | [40] | |

| MWCNT-COOH | 10 | 6 | 500 | 100.0 | [41] | |

| GO | 25 | 6 | 200 | 487.80 | [42] | |

| GO-BP | 50 | 6 | 100 | 374.53 | This work | |

| EY | Zeolite Y | 100 | 2.5 | 60 | 52.91 | [43] |

| CNTs incorporated eucalyptus | 20 | 6 | 50 | 49.15 | [44] | |

| GO | 300 | 1 | 50 | 217.33 | [35] | |

| GO/ZnO nanocomposite | 230 | 2 | 100 | 555.55 | [36] | |

| GO-BP | 50 | 6 | 100 | 85.38 | This work | |

| MG | Fe3O4-AC | 100 | 6 | 300 | 217.68 | [45] |

| GO/aminated lignin aerogels | 20 | 8 | 50 | 113.5 | [46] | |

| GO-Cellulose-Cu | 1000 | 7 | 400 | 207.1 | [47] | |

| MWCNT-COOH | 40 | 7 | 100 | 142.85 | [48] | |

| rGO | 50 | 7 | 200 | 476.2 | [49] | |

| GO-BP | 50 | 6 | 100 | 493.44 | This work | |

| RB | Magnesium silicate/carbon composite | 100 | 6.5 | 600 | 244 | [50] |

| Montmorillonite/GO | 300 | 7 | 150 | 625.0 | [51] | |

| Benzene carboxylic acid/ GO-zeolite | 10 | 3 | 500 | 67.56 | [52] | |

| MWCNT-COOH | 50 | 7 | 100 | 42.68 | [53] | |

| GO-BP | 50 | 6 | 100 | 467.35 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).