Submitted:

14 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicting interests

Abbreviations

| AS | Aortic stenosis |

| LVM | Left ventricular mass |

| LVMi | Left ventricular mass index |

| LVEF | Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| AVA | Aortic valve area |

| LVH | Left ventricular hypertrophy |

| AVR | Aortic valve replacement |

| TAVI | Transcatheter aortic valve implantation |

| CAD | Coronary artery disease |

| PASP | Pulmonary artery systolic pressure |

References

- Otto CM, Burwash IG, Legget ME, et al. Prospective study of asymptomatic valvular aortic stenosis. Clinical, echocardiographic, and exercise predictors of outcome. Circulation 1997;95:2262-2270. [CrossRef]

- Rosenhek R, Binder T, Porenta G, et al. Predictors of outcome in severe, asymptomatic aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med 2000;343:611-617.

- Pellikka PA, Sarano ME, Nishimura RA, et al. Outcome of 622 adults with asymptomatic, hemodynamically significant aortic stenosis during prolonged follow-up. Circulation 2005;111:3290-3295. [CrossRef]

- Avakian SD, Grinberg M, Ramires JA, Mansur AP. Outcome of adults with asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis. Int J Cardiol 2008;123:322-327. [CrossRef]

- Bing R, Cavalcante JL, Everett RJ, et al. Imaging and impact of myocardial fibrosis in aortic stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2019;12:283-296. [CrossRef]

- Dweck MR, Boon NA, Newby DE. Calcific aortic stenosis: a disease of the valve and the myocardium. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1854-1863.

- De Biase N, Mazzola M, Del Punta L, et al. Haemodynamic and metabolic phenotyping of patients with aortic stenosis and preserved ejection fraction: A specific phenotype of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction? Eur J Heart Fail 2023;25:1947-1958.

- Azevedo CF, Nigri M, Higuchi ML, et al. Prognostic significance of myocardial fibrosis quantification by histopathology and magnetic resonance imaging in patients with severe aortic valve disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:278-287. [CrossRef]

- Cioffi G, Faggiano P, Vizzardi E, et al. Prognostic effect of inappropriately high left ventricular mass in asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis. Heart 2011;97:301-307. [CrossRef]

- Stassen J, Ewe SH, Hirasawa K, et al. Left ventricular remodelling patterns in patients with moderate aortic stenosis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2022;23:1326-1335. [CrossRef]

- Lorell BH, Carabello BA. Left ventricular hypertrophy: pathogenesis, detection, and prognosis. Circulation 2000;102:470-479.

- Duncan AI, Lowe BS, Garcia MJ, et al. Influence of concentric left ventricular remodeling on early mortality after aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;85:2030-2039. [CrossRef]

- Burchfield JS, Xie M, Hill JA. Pathological ventricular remodeling: mechanisms: part 1 of 2. Circulation 2013;128:388-400.

- Minamino-Muta E, Kato T, Morimoto T, et al. Impact of the left ventricular mass index on the outcomes of severe aortic stenosis. Heart 2017;103:1992-1999. [CrossRef]

- DesJardin JT, Chikwe J, Hahn RT, et al. Sex Differences and Similarities in Valvular Heart Disease. Circ Res 2022;130:455-473. [CrossRef]

- Devereux RB, Alonso DR, Lutas EM, et al. Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy: comparison to necropsy findings. Am J Cardiol 1986;57:450-8. [CrossRef]

- Lang RM, Biering M, Devereux RB, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2005;18:1440-1463.

- Fuster RG, Argudo JA, Albarova OG, et al. Left ventricular mass index in aortic valve surgery: a new index for early valve replacement? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2003;23:696-702.

- Stassen J, Pio SM, Ewe SH, et al. Sex-Related Differences in Medically Treated Moderate Aortic Stenosis. Struct Heart 2022;6:100042. [CrossRef]

- Gonzales H, Douglas PS, Pibarot P, et al. Left Ventricular Hypertrophy and Clinical Outcomes Over 5 Years After TAVR: An Analysis of the PARTNER Trials and Registries. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2020;13:1329-1339.

- Rader F, Sachdev E, Arsanjani R, Siegel RJ. Left ventricular hypertrophy in valvular aortic stenosis: mechanisms and clinical implications. Am J Med 2015;128:344-352. [CrossRef]

- Gerdts E, Rossebø AB, Pedersen TR, et al. Relation of Left Ventricular Mass to Prognosis in Initially Asymptomatic Mild to Moderate Aortic Valve Stenosis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;8:e003644. [CrossRef]

- Douglas PS, Otto CM, Mickel MC, et al. Gender differences in left ventricle geometry and function in patients undergoing balloon dilatation of the aortic valve for isolated aortic stenosis. NHLBI Balloon Valvuloplasty Registry. Br Heart J 1995;73:548-554. [CrossRef]

- Pighi M, Piazza N, Martucci G, et al. Sex-Specific Determinants of Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2019;12:e005363.

- Singh A, Musa TA, Treibel TA, et al. Sex differences in left ventricular remodelling, myocardial fibrosis and mortality after aortic valve replacement. Heart 2019;105:1818-1824. [CrossRef]

- Capoulade R, Clavel MA, Le Ven F, et al. Impact of left ventricular remodelling patterns on outcomes in patients with aortic stenosis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;18:1378-1387. [CrossRef]

- Gavina C, Falcao-Pires I, Pinho P, et al. Relevance of residual left ventricular hypertrophy after surgery for isolated aortic stenosis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;49:952–959. [CrossRef]

- Hachicha Z, Dumesnil JG, Bogaty P, Pibarot P. Paradoxical low-flow, low-gradient severe aortic stenosis despite preserved ejection fraction is associated with higher afterload and reduced survival. Circulation 2007;115:2856–2864. [CrossRef]

- Tastet L, Kwiecinski J, Pibarot P, et al. Sex-Related Differences in the Extent of Myocardial Fibrosis in Patients With Aortic Valve Stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2020;13:699-711. [CrossRef]

- Kararigas G, Dworatzek E, Petrov G, et al. Sex dependent regulation of fibrosis and inflammation in human left ventricular remodelling under pressure overload. Eur J Heart Fail 2014;16:1160–1167. [CrossRef]

- Naoum C, Blanke P, Dvir D, et al. Clinical Outcomes and Imaging Findings in Women Undergoing TAVR. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;9:483-493. [CrossRef]

- Treibel TA, Kozor R, Fontana M, et al. Sex Dimorphism in the Myocardial Response to Aortic Stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;11:962-973. [CrossRef]

- Kwak S, Singh A, Everett RJ, et al. Sex-Specific Association of Myocardial Fibrosis With Mortality in Patients With Aortic Stenosis. JAMA Cardiol 2025;19:e245593. [CrossRef]

- Zwadlo C, Schmidtmann E, Szaroszyk M, et al. Antiandrogenic therapy with finasteride attenuates cardiac hypertrophy and left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation 2015;131:1071-1081. [CrossRef]

- Chehab O, Shabani M, Varadarajan V, et al. Endogenous sex hormone levels and myocardial fibrosis in men and postmenopausal women. JACC Adv 2023;2:100320. [CrossRef]

- Greiten LE, Holditch SJ, Arunachalam SP, Miller VM. Should there be sex-specific criteria for the diagnosis and treatment of heart failure? J Cardiovasc Transl Res 2014;7:139-155.

- Shub C, Klein AL, Zachariah PK, et al. Determination of left ventricular mass by echocardiography in a normal population: effect of age and sex in addition to body size. Mayo Clin Proc 1994;69:205-211. [CrossRef]

- Sickinghe AA, Korporaal SJA, den Ruijter HM, Kessler EL. Estrogen contributions to microvascular dysfunction evolving to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019;10:442. [CrossRef]

- Petrov G, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Lehmkuhl E, et al. Regression of myocardial hypertrophy after aortic valve replacement: faster in women? Circulation 2010;122(11 Suppl):S23-S28.

- Zhou L, Shao Y, Huang Y, Yao T, Lu LM. 17-Estradiol inhibits angiotensin II-induced collagen synthesis of cultured rat cardiac fibroblasts via modulating angiotensin II receptors. Eur J Pharmacol 2007;567:186 –192. [CrossRef]

- Michail M, Davies JE, Cameron JD, et al. Pathophysiological coronary and microcirculatory flow alterations in aortic stenosis. Nat Rev Cardiol 2018;15:420-431. [CrossRef]

- McConkey HZR, Marber M, Chiribiri A, et al. Coronary Microcirculation in Aortic Stenosis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2019;12:e007547. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds HR, Bairey Merz CN, Berry C, et al. Coronary Arterial Function and Disease in Women With No Obstructive Coronary Arteries. Circ Res 2022;130:529-551. [CrossRef]

- Oguz D, Huntley GD, El-Am EA, et al. Impact of atrial fibrillation on outcomes in asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis: a propensity-matched analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med 2023;10:1195123. [CrossRef]

| All patients N=531 (%) |

Men N=283 (53.3) |

Women N=248 (46.7) |

p | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 74.7 (11.6) | 74.1 (12.6) | 75.5 (10.2) | 0.149 |

| Time since baseline, mean (SD), y | 2.7 (1.2) | 2.8 (1.3) | 2.6 (1.2) | 0.138 |

| Dyslipidemia, No. (%) | 177 (33.3) | 81 (28.6) | 96 (38.7) | 0.014 |

| Hypertension, No. (%) | 390 (73.6) | 192 (68.1) | 198 (79.8) | 0.002 |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 153 (28.8) | 85 (30.0) | 68 (27.4) | 0.507 |

| Smoking, No. (%) | 43 (8.1) | 23 (8.1) | 20 (8.1) | 0.979 |

| Anemia, No. (%) | 145 (27.3) | 81 (28.6) | 64 (25.8) | 0.468 |

| Syncope, No. (%) | 46 (8.7) | 32 (11.3) | 14 (5.7) | 0.021 |

| Angina, No. (%) | 197 (37.1) | 112 (39.6) | 85 (34.3) | 0.207 |

| Dyspnea, No. (%) | 475 (89.5) | 247 (87.3) | 228 (91.9) | 0.081 |

| AF, No. (%) | 33 (6.2) | 24 (8.5) | 9 (3.6) | 0.021 |

| Weight, mean (SD), Kg | 74.3 (14.3) | 79.1 (13.0) | 68.6 (13.6) | <0.001 |

| BSA, mean (SD), m2 | 1.8 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.2) | 1.7 (0.2) | <0.001 |

| LVEF, mean (SD), % | 60.6 (9.6) | 58.7 (10.7) | 62.8 (7.6) | <0.001 |

| LVMi, mean (SD), g/m2 | 118.6 (30.6) | 122.1 (29.9) | 114.5 (30.9) | 0.004 |

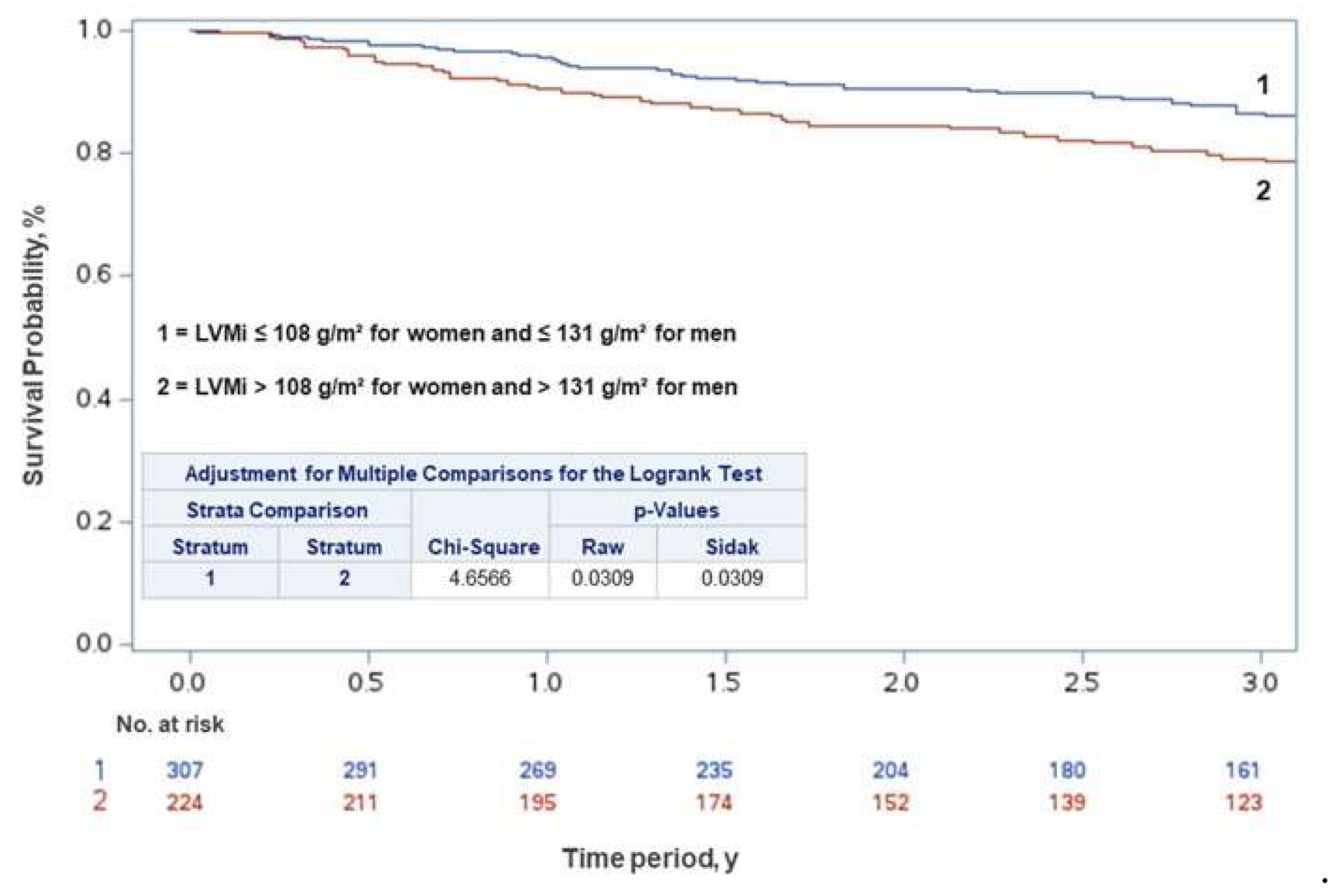

| LVMi moderate+severe | 224 (42.2) | 90 (31.8) | 134 (54.0) | <0.001 |

| LA Volume, mean (SD), ml | 44.9 (15.2) | 45.3 (14.5) | 44.5 (16.0) | 0.666 |

| Peak Gradient, mean (SD), mmHg | 79.8 (22.9) | 76.9 (21.4) | 83.1 (24.2) | 0.002 |

| Mean Gradient, mean (SD), mmHg | 50.5 (15.6) | 48.6 (14.7) | 52.6 (16.3) | 0.003 |

| Valve area, mean (SD), cm2 | 0.87 (2.42) | 1.0 (3.3) | 0.72 (0.19) | 0.155 |

| Peak Jet velocity, mean (SD), m/s | 4.4 (0.6) | 4.3 (0.6) | 4.5 (0.6) | 0.002 |

| Bicuspid / Tricuspid, No. (%) | 54 (10.2) / 477 (89.8) | 30 (10.6) / 253 (89.4) | 24 (9.68) / 224 (90.3) | 0.725 |

| CAD, No. (%) | 279 (52.5) | 172 (60.78) | 107 (43.2) | <0.001 |

| AVR, No. (%) | 162 (30.5) | 91 (32.2) | 71 (28.6) | 0.378 |

| Valvuloplasty, No. (%) | 13 (2.45) | 10 (3.5) | 3 (1.21) | 0.084 |

| TAVI, No. (%) | 98 (18.5) | 46 (16.3) | 52 (20.97) | 0.163 |

| Death, No. (%) | 165 (31.1) | 89 (31.5) | 76 (30.7) | 0.842 |

| Cardiovascular death, No. (%) | 148 (27.9) | 79 (27.9) | 69 (27.8) | 0.921 |

| All patients N=531 (%) |

Survivors N=366 (68.9) |

Non-Survivors N=165 (31.1) |

p | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 74.7 (11.6) | 74.4 (11.3) | 75.5 (12.1) | 0.133 |

| Female, No. (%) | 366 (68.9) | 172 (47.0) | 76 (46.1) | 0.841 |

| Time since baseline, mean (SD), y | 2.7 (1.2) | 2.73 (1.2) | 2.55 (1.3) | 0.146 |

| Dyslipidemia, No. (%) | 177 (33.3) | 124 (33.4) | 53 (32.1) | 0.691 |

| Hypertension, No. (%) | 390 (73.6) | 270 (73.8) | 120 (73.2) | 0.885 |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 153 (28.8) | 101 (27.6) | 52 (31.5) | 0.356 |

| Smoking, No. (%) | 43 (8.1) | 26 (7.1) | 17 (10.3) | 0.211 |

| Anemia, No. (%) | 145 (27.3) | 96 (26.2) | 49 (29.7) | 0.410 |

| Syncope, No. (%) | 46 (8.7) | 35 (9.6) | 11 (6.7) | 0.272 |

| Angina, No. (%) | 197 (37.1) | 146 (39.9) | 51 (30.9) | 0.047 |

| Dyspnea, No. (%) | 475 (89.5) | 325 (88.8) | 150 (90.9) | 0.463 |

| AF, No. (%) | 33 (6.2) | 15 (4.1) | 18 (10.9) | 0.003 |

| Weight, mean (SD), Kg | 74.3 (14.3) | 74.7 (14.2) | 73.4 (14.6) | 0.334 |

| BSA, mean (SD), m2 | 1.8 (0.21) | 1.8 (0.2) | 1.7 (0.2) | 0.205 |

| LVEF, mean (SD), % | 60.6 (9.6) | 61.4 (8.9) | 58.8 (10.8) | 0.008 |

| LVMi, mean (SD), g/m2 | 118.6 (30.6) | 115.5 (29.3) | 125.3 (32.5) | <0.001 |

| LVMi moderate+severe | 224 (42.2) | 136 (37.2) | 88 (53.3) | <0.001 |

| LA Volume, mean (SD), ml | 44.9 (15.2) | 44.4 (16.1) | 46.3 (12.8) | 0.246 |

| Peak Gradient, mean (SD), mmHg | 79.8 (22.9) | 80.4 (23.3) | 78.4 (22.0) | 0.365 |

| Mean Gradient, mean (SD), mmHg | 50.5 (15.6) | 50.6 (15.7) | 50.4 (15.3) | 0.894 |

| Valve area, mean (SD), cm2 | 0.87 (2.42) | 0.9 (2.9) | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.258 |

| Peak Jet velocity, mean (SD), m/s | 4.4 (0.6) | 4.4 (0.6) | 4.4 (0.6) | 0.359 |

| Bicuspid / Tricuspid, No. (%) | 54 (10.2) / 477 (89.8) | 42 (11.5) / 324 (88.5) | 12 (7.2) / 153 (92.7) | 0.138 |

| CAD, No. (%) | 279 (52.5) | 183 (50.0) | 96 (58.1) | 0.081 |

| AVR, No. (%) | 162 (30.5) | 142 (38.8) | 20 (12.1) | <0.001 |

| Valvuloplasty, No. (%) | 13 (2.45) | 5 (1.37) | 8 (4.9) | 0.016 |

| TAVI, No. (%) | 98 (18.5) | 85 (23.2) | 13 (7.9) | <0.001 |

| Survivors | p | Non-Survivors | p | |||

| Men N=194 (53) |

Women N=172 (47) |

Men N=89 (53.9) |

Women N=76 (46.1) |

|||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 75.1 (10.5) | 75.1 (10.8) | 0.792 | 73.9 (15.0) | 73.0 (11.2) | 0.650 |

| Time since baseline, mean (SD), y | 2.8 (1.2) | 2.7 (1.1) | 0.284 | 2.7 (1.4) | 2.4 (1.3) | 0.289 |

| Dyslipidemia, No. (%) | 59 (30.4) | 65 (37.8) | 0.137 | 22 (24.7) | 31 (40.8) | 0.028 |

| Hypertension, No. (%) | 127 (65.5) | 143 (83.1) | <0.001 | 65 (73.9) | 55 (72.4) | 0.829 |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 50 (25.8) | 51 (29.7) | 0.408 | 35 (39.3) | 17 (22.4) | 0.019 |

| Smoking, No. (%) | 16 (8.3) | 10 (5.8) | 0.366 | 7 (7.9) | 10 (13.2) | 0.265 |

| Anemia, No. (%) | 52 (26.8) | 44 (25.6) | 0.791 | 29 (32.6) | 20 (26.3) | 0.380 |

| Syncope, No. (%) | 25 (12.9) | 10 (5.8) | 0.022 | 7 (7.9) | 4 (5.3) | 0.506 |

| Angina, No. (%) | 86 (44.3) | 60 (34.8) | 0.066 | 26 (29.2) | 25 (32.9) | 0.610 |

| Dyspnea, No. (%) | 169 (87.1) | 156 (90.7) | 0.279 | 78 (87.6) | 72 (94.7) | 0.114 |

| AF, No. (%) | 12 (6.19) | 3 (1.74) | 0.032 | 12 (13.5) | 6 (7.9) | 0.251 |

| Weight, mean (SD), Kg | 79.7 (12.6) | 69.0 (13.7) | <0.001 | 27.9 (13.9) | 67.6 (13.5) | <0.001 |

| BSA, mean (SD), m2 | 1.9 (0.2) | 1.7 (0.2) | <0.001 | 1.9 (0.2) | 1.7 (0.2) | <0.001 |

| LVEF, mean (SD), % | 59.6 (9.7) | 63.4 (6.9) | <0.001 | 56.7 (12.0) | 61.3 (8.7) | 0.006 |

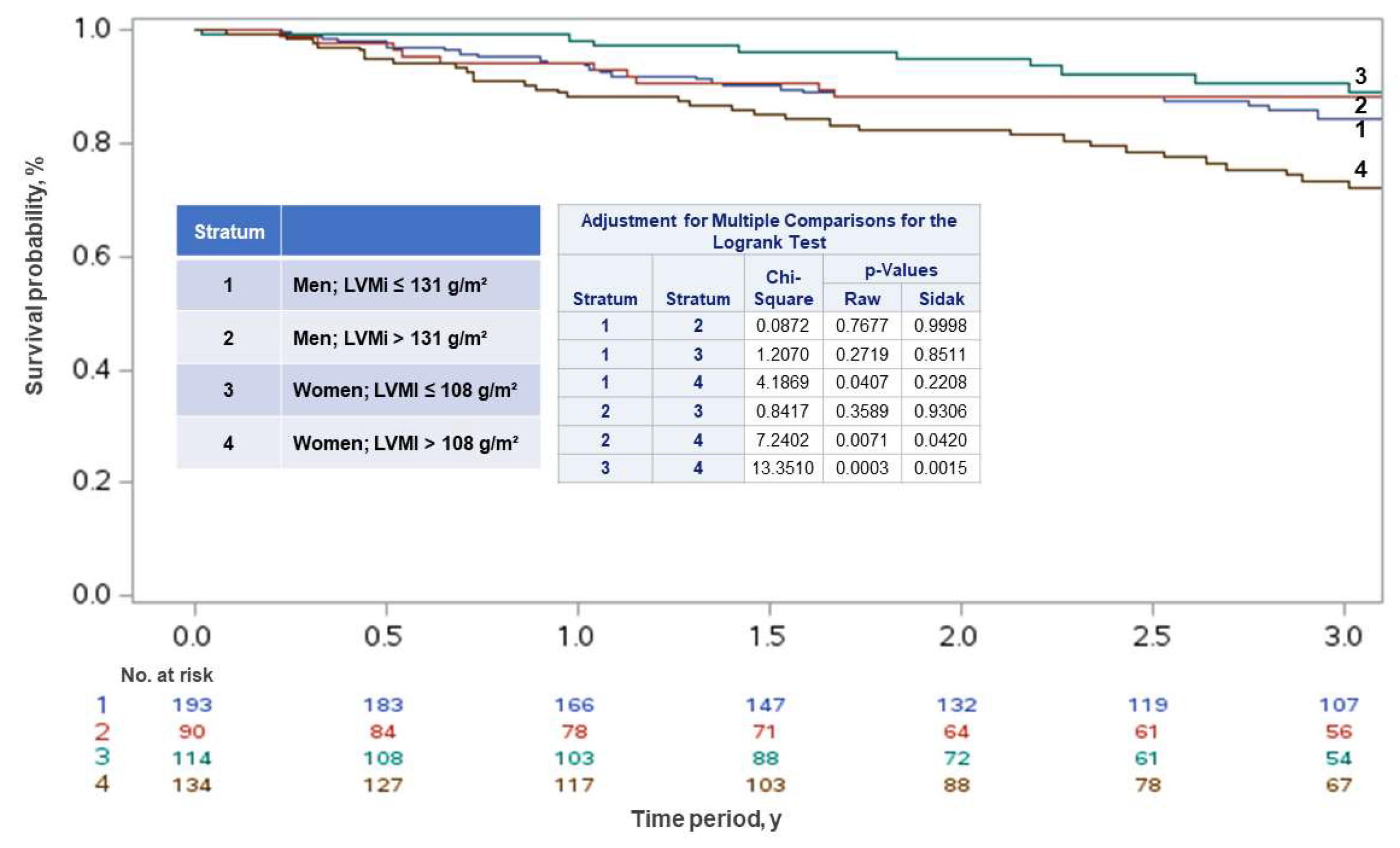

| LVMi, mean (SD), g/m2 | 120.3 (29.1) | 110.1 (28.5) | <0.001 | 125.9 (31.5) | 124.5 (33.8)a | 0.784 |

| LVMi moderate+severe | 60 (30.9) | 76 (44.2) | 0.009 | 30 (33.7) | 58 (76.3)a | <0.001 |

| LA Volume, mean (SD), ml | 44.8 (15.4) | 43.8 (16.9) | 0.619 | 46.6 (12.2) | 46.3 (13.7) | 0.995 |

| Peak Gradient, mean (SD), mmHg | 77.6 (20.5) | 83.6 (25.8) | 0.015 | 75.4 (23.1) | 82.0 (20.2) | 0.057 |

| Mean Gradient, mean (SD), mmHg | 48.9 (14.0) | 52.5 (17.3) | 0.030 | 48.1 (16.1) | 53.1 (13.9) | 0.038 |

| Valve area, mean (SD), cm2 | 1.1 (4.0) | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.200 | 0.8 (1.2) | 0.7 (0.2) | <0.001 |

| Peak Jet velocity, mean (SD), m/s | 4.4 (0.6) | 4.5 (0.7) | 0.023 | 4.3 (0.7) | 4.5 (0.6) | 0.039 |

| Bicuspid / Tricuspid, No. (%) | 23 (11.9)/171 (88.1) | 19 (11.1)/153 (88.9) | 0.809 | 7 (7.9)/82 (92.1) | 5 (6.6)/71 (93.4) | 0.751 |

| CAD, No. (%) | 114 (58.8) | 69 (40.1) | <0.001 | 58 (65.2) | 38 (50) | 0.049 |

| AVR, No. (%) | 82 (42.3) | 60 (34.9) | 0.148 | 9 (10.1) | 11 (14.5) | 0.392 |

| Valvuloplasty, No. (%) | 4 (2.1) | 1 (0.6) | 0.223 | 6 (6.7) | 2 (2.6) | 0.220 |

| TAVI, No. (%) | 38 (19.6) | 47 (27.3) | 0.081 | 8 (9.0) | 5 (6.6) | 0.567 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).