1. Sotatercept in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: Between Efficacy and Side Effects

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a rare disease caused by hypertrophy of the media and hyperplasia of the intima of the pulmonary arteries and arterioles, with involvement of the pulmonary interstitium (1). This remodeling results in an increase in mean arterial pressure (mPAP) measured in the pulmonary artery during right heart catheterization (RHC) at rest, and increased pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) (1). The pulmonary remodeling ultimately culminates in right ventricular failure and death. The blockade and eventual resolution of pulmonary remodeling are the rationale for the development of drugs that block patological remodeling, and thus able to modify the progression of the disease. Sotatercept has recently been introduced for the treatment of PAH, as a drug with strong inhibitory activity on pathological remodeling, and therefore potentially able to arrest the progression of disease (2). The STELLAR study was an international pivotal randomized clinical trial demonstrating that treatment of patients with group 1 PAH with sotatercept for 24 weeks improves 6-minute walk distance (6MWD), pulmonary vascular resistance, serum levels of the N-terminal fragment of the prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide, the functional class of the World Health Organization, and the time to the first onset of non-fatal clinical worsening (2). Since clinical improvement noticed in the STELLAR study could not have been obtained by the current standard of care, sotatercept could represent the fourth pillar in the treatment of PAH (2-5). In the STELLAR study, in the sotatercept arm, a higher incidence of telangiectasia and increased hemoglobin level were however recorded (2). Furthermore, the study showed an increase in bleeding events in the sotatercept group (21.5%) versus placebo (12.5%), regardless of the decrease in platelet count (2).

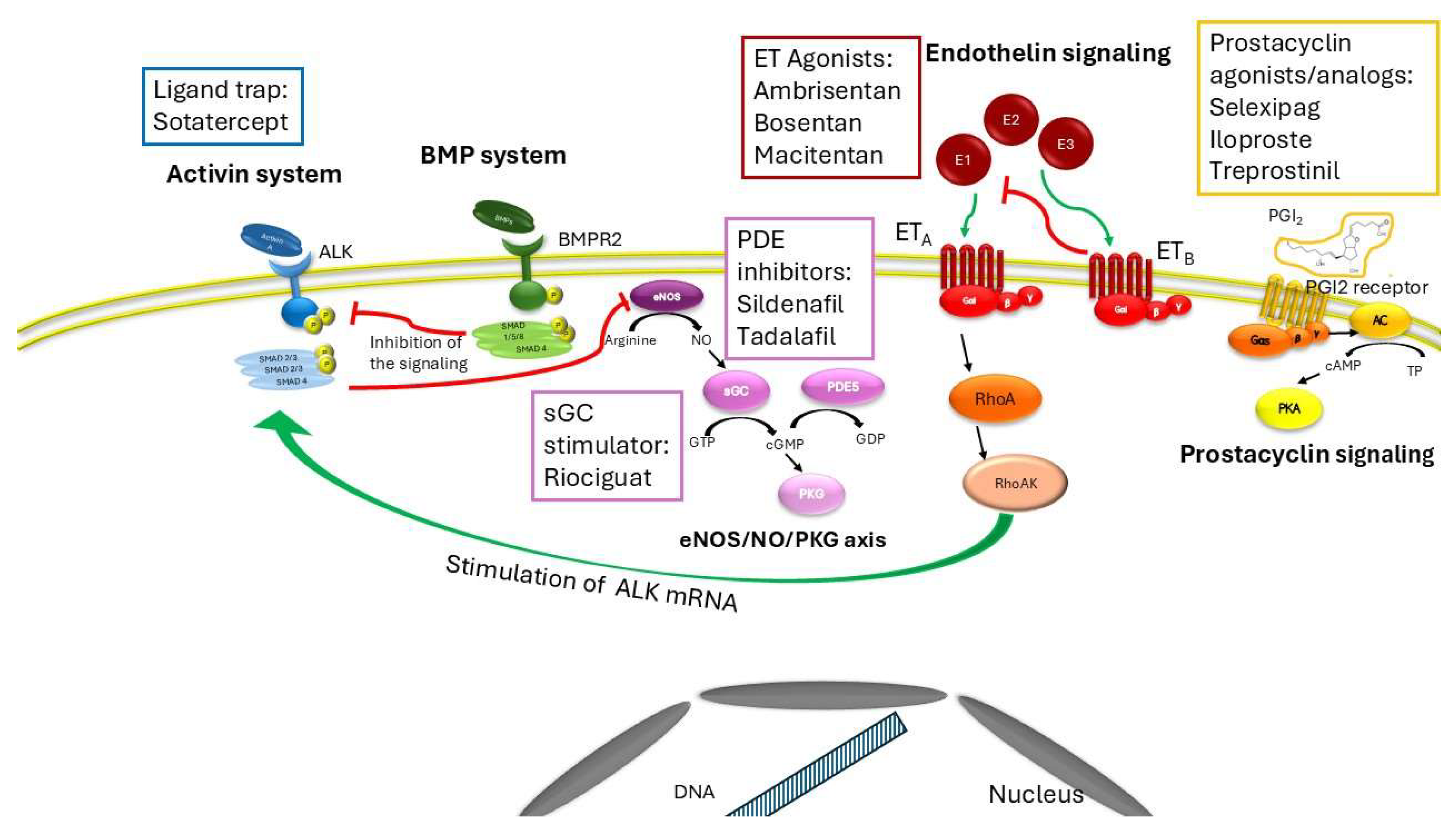

Sotatercept (6) sequesters free activins that act as an inhibitory brake on bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) activity, leading to deregulated proliferation of pulmonary arteries and arterioles. BMP binds to and activates the type 2 receptor (BMPR2) that phosphorylates the transcription factor SMAD1/5/8, allowing them to translocate into the nucleus and bind to specific sites on DNA. This binding inhibits DNA replication and the cell cycle in endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells (6). Activins are homodimeric polypeptide growth factor highly homologous to TGF-β that interact with the Alk1 receptor (6). Alk1 is a transmembrane protein with serine/threonine kinase activity that forms a heteromeric complex and phosphorylates the nuclear transcription factor Suppressor of Mothers against Decapentaplegic (SMAD) homolog 2 and homolog 3 (SMAD2/3). Activin-Alk1 binding induces DNA replication and cell cycle in endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells, leading to a variety of pulmonary conditions, such as interstitial pulmonary fibrosis and idiopathic or hereditary PAH (6).

Sotatercept is administered subcutaneously and involves titration from a baseline dose of 0.3 mg/kg to 0.7 mg/kg once every 3 weeks. If we analyze the curve of the STELLAR study in which the effects on the time to clinical worsening of the arm treated with background therapy and the arm treated with sotatercept on top of background therapy are shown, we note how the curves diverge significantly and very early (2). An effect that suggests that sotatercept not only play an inhibitory action on pathological remodeling per se (which requires longer times to manifest itself) but evidently off-target effects on other signaling pathways that lead to vasodilation, an effect that appears much earlier than the anti-remodeling effect alone. There are several points of interaction between the sotatercept signaling pathway and other signaling pathways on which other vasodilatory drugs specific for PAH act. First, Alk1 colocalizes with endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in endothelial caveolae, where both interact with caveolin-1 (7). Treatment of pulmonary endothelial cells with activin A reduces eNOS expression (8). Furthermore, ET-1 increases Alk expression via the Gi/RhoA/Rho kinase pathway. Activation of Gi and RhoA is associated with Alk promoter activity via Sp-1 and Alk mRNA stability (9). In light of the extensive interactions between NO, ET-1, and activin, it is possible that sotatercept not only reduces the dysregulated proliferation of pulmonary circulation vessels, but also regulates their vasodilation through sequestration of activin, thereby removing the inhibitory brake on eNOS.

In addition to its effects on pulmonary circulation, sotatercept has several hematologic effects that may suggest its use in the treatment of certain blood disorders (10), but also may explain the side effects of the drug in the PAH trials.

In this review, we will discuss the application of sotatercept, with the aim of analyzing in deep its cross reactivity in function and signaling alone or in combination with other drugs currently used in PAH. We will try also to further understand the hematological effects of sotatercept which are the root of the side effects seen in PAH trials, such as bleeding and increased hemoglobin.

2. Crosstalk Between the Activin System and Other Signalings

2.1. The Activin System

The activin system is a signal transduction system widely distributed in tissues which controls several the body development, from embryogenesis to adulthood (11). Activins belong to the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β superfamily and bind to a combination of receptors with serine/threonine kinase activity. The binding to activin receptor like type 1 (ALK1) stimulates the kinase activity of the intracellular domain of the receptor, inducing the phosphorylation of transcription factor Suppressor of Mothers against Decapentaplegic (SMAD) homolog 2 and homolog 3 and the subsequent formation of the phosphoSMAD2/3/4 complex, which translocates to the nucleus (12). Several ligands can bind and activate the activin system, among them activin A, growth differentiation factor (GDF)11 and bone morphogenetic proteins (BMP)10 promoting the expression of genes that regulate several cellular processes including cell cycle, proliferation, differentiation, extracellular matrix (ECM) formation, erythropoiesis and apoptosis (13). An excessive stimulation of activin signaling by activin A or a lack of inhibition exerted by BMP system, evoke an imbalance between activin and BMP signaling, produce pro-fibrotic effects or alteration in erythropoiesis which underly several pathological conditions such asthma, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, inflammation, interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, and PAH (14, 15, 10), BPM10, considered a biomarker in heart diseases, including atrial fibrillation and heart failure (16, 17), is involved in the physiological function of the vascular endothelium by modulating remodelling and angiogenesis (18). BMP10 forms heterodimers with BMP9 and subsequently a receptor complex involving ALK1, bone morphogenic protein receptor 2 (BMPR2) and endoglin allowing the maintenance of balance between angiogenesis and maturation of lymphatic vessels by regulating the differentiation of vascular endothelium in endothelial cells and morphogenesis (19). The dysregulation of the complex due to mutations can alter the integrity and functionality of pulmonary vascular endothelium leading to PAH (18).

The activins represent a critical signaling pathway also in hematological disorders. Overstimulation by GDF11 impacts at different stages of erythropoiesis from the differentiation of erythroid burst-forming units to the proliferation of erythroid progenitor cells (20). Moreover, its overexpression, due to oxidative stress or alpha-globin precipitation, can evoke an autocrine amplification loop (21) and an excessive number of immature erythroblasts blocking terminal erythroid maturation (21). Loss-of-function mutations in SEC23B and high GDF11 levels have also been observed (22). These effects lead overall to several blood disorders including beta-thalassemia, myelodysplastic syndromes, dyserythropoietic anemias and multiple myeloma which are counteracted by treatments with sotatercept (10). Moreover, as already indicated activin signaling co-localizes and interacts with other pathways which are described in the following paragraphs (

Figure 1).

2.2. The Bone Morphogenetic Protein System

As activins, also bone morphogenetic proteins (BMP) are members of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily. The BMP signaling exerts antifibrotic effects and is widely distributed in tissues and organs, including the lungs maintaining the integrity of the endothelial wall of arteries (23, 15). BMP receptors are serine/threonine kinases and the binding to the type II receptor (BMPRII) triggers the activation by phosphorylation of the type I. The complex targets the receptor- regulated SMADs by phosphorylation. The SMADS mainly involved are SMAD1, SMAD5 and SMAD9 (11) which aggregate upon phosphorylation with SMAD4 and translocate to the nucleus regulating the expression of genes such as inhibitor DNA binding 1 which may play a critical role in cell growth, senescence, and differentiation, and inhibitor of DNA binding 2 that negatively regulate cell differentiation and cell cycle in endothelial and smooth muscle cells (15, 23). Dysregulation in the BMP signaling underlies inherited and non-hereditary forms of PAH (24, 25), leading to a decrease in antiproliferative effects. Several genes encoding proteins involved in the BMP signal transduction and highly expressed in vascular endothelial cells are mutated in PAH, including BMPR2, ALK1 and endoglin (ENG) (23), leading to endothelial dysfunction, i.e. cell apoptosis, compromised barrier function, altered vasoactive mediator release and permeability in lung vasculature (23). Mutations in ALK1 and ENG are associated with different types of hemorrhagic telangiectasia, also known as Rendu-Osler-Weber syndromes (26). Dysregulated endothelial BMP signaling is no longer able to attenuate the activin system, provoking an imbalance which triggers a pulmonary vascular remodeling (Figure 1).

2.3. Endothelin Receptor Signaling

Sugimoto et al 2021 demonstrated that the endothelin-1 and the activin systems can interact each other through the Gi/RhoA/Rho kinase pathway in human pulmonary artery endothelial cells (9). The cross talk between the two pathways potentiates the vasoconstrictor action of the ET-1 signaling (9) whose activation upregulates the activin receptor like kinase 1 expression. Endothelin receptor antagonists such as ambrisentan, bosentan e macitentan are oral drugs currently approved for the treatment of PAH (27) which prevent the binding between endothelin receptor and its natural ligands (27). Bosentan and macitentan are non-peptide dual antagonist of the binding of endothelin-1 to ET A and ET B receptors in human pulmonary arterial smoothmuscle cells (28, 29), while ambrisentan is a selective potent antagonist against the ETA receptor (30). The endothelin receptor signaling consists of two seven transmembrane (7TM) receptor subtypes, endothelin receptor type A, (ETA), and endothelin receptor type B (ETB) which, binding endothelins, can activate multiple types of G proteins (31). They modulate several physiological processes including vasoconstriction, vasodilation, growth, survival, invasion and angiogenesis (31). Endothelins are a family of 21 amino acid peptides produced by endothelium: endothelin 1 (ET-1) and ET-2 activate both receptor subtypes with equal affinity, whereas ET-3 has a lower affinity for ETA (32). Among all endothelins, the first discovered peptide endothelin-1 presents the strongest vasoconstrictor effect by interacting with ETA receptor (31). Interestingly, the binding with ETB mediates vasodilation and the clearance of circulating endothelin-1 by lysosomal degradation (31), promoting the development of novel pharmacological strategies in the form of agonists of ETB agonists (31) (Figure 1).

2.4. cGMP/Phosphodiesterase Signaling

The activin system can downregulate endothelial nitric oxide synthetase (eNOS), disrupting the NO signaling and thus leading to an increase to pulmonary pressure (7, 8). The NO-soluble guanylate cyclase-cyclic guanosine monophosphate (NO-sGC-cGMP) axis is one of the signaling which enables vasodilation, regulates blood pressure, improves vascular function, and inhibits inflammation, fibrosis, and cell proliferation (33). Phosphodiesterase 5 catalyzes the degradation of the second messenger cGMP, and inhibitors of this enzyme are effective treatments in attenuating pulmonary hypertension and vascular remodeling in PAH (34). PDE5 inhibitors and soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators, including sildenafil, tadalafil and riociguat can produce vasodilation or attenuate PAH remodelling both by maintaining high concentrations of intracellular cGMP which induce antiproliferative, antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory effects (33, 9) (Figure 1).

2.5. Prostacyclin System

In 2024 Savale et al (35) observed a downregulation of the insulin-like growth factor binding protein (IGFBP) 7 in patients treated with sotatercept compared to placebo; IGFBP7 can stimulate prostacyclin production and cell adhesion but it is also a biomarker for PAH whose increased expression may be associated to fibrotic changes in pulmonary vasculature; (36). Prostacyclin (PGI2) is a potent vasodilator with antiplatelet and antiproliferative properties which can protect against atrial fibrosis (37). PGI2 is primarily synthesized in vascular endothelial, vascular smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts from arachidonic acid by the sequential catalysis of cyclooxygenase-2 and PGI synthase upon endogenous or exogenous stimuli (38). When it binds its receptors, a Gs-type G protein-coupled receptor, PGI2 evokes the activation of adenylyl cyclase and thus the synthesis of cyclic adenosine 3’,5’-monophosphate (cAMP) which in turn binds and activates protein kinase A, inducing the final effects (38). PGI2 acts as potent anti-fibrotic and vasodilator agent by inhibiting cell proliferation, smooth muscle contraction and platelet aggregation, decreasing the synthesis of proteins of the extracellular matrix (ECM), and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (39, 38). Treatment with prostacyclin analogs such as selexipag, iloprost, treprostinil or epoprostenol, can improve clinical worsening in PAH patients over background targeted therapies, by improving exercise capacity, mean pulmonary artery pressure, and cardiac index, even though an overall risk of adverse events cannot be excluded (40) (Figure 1).

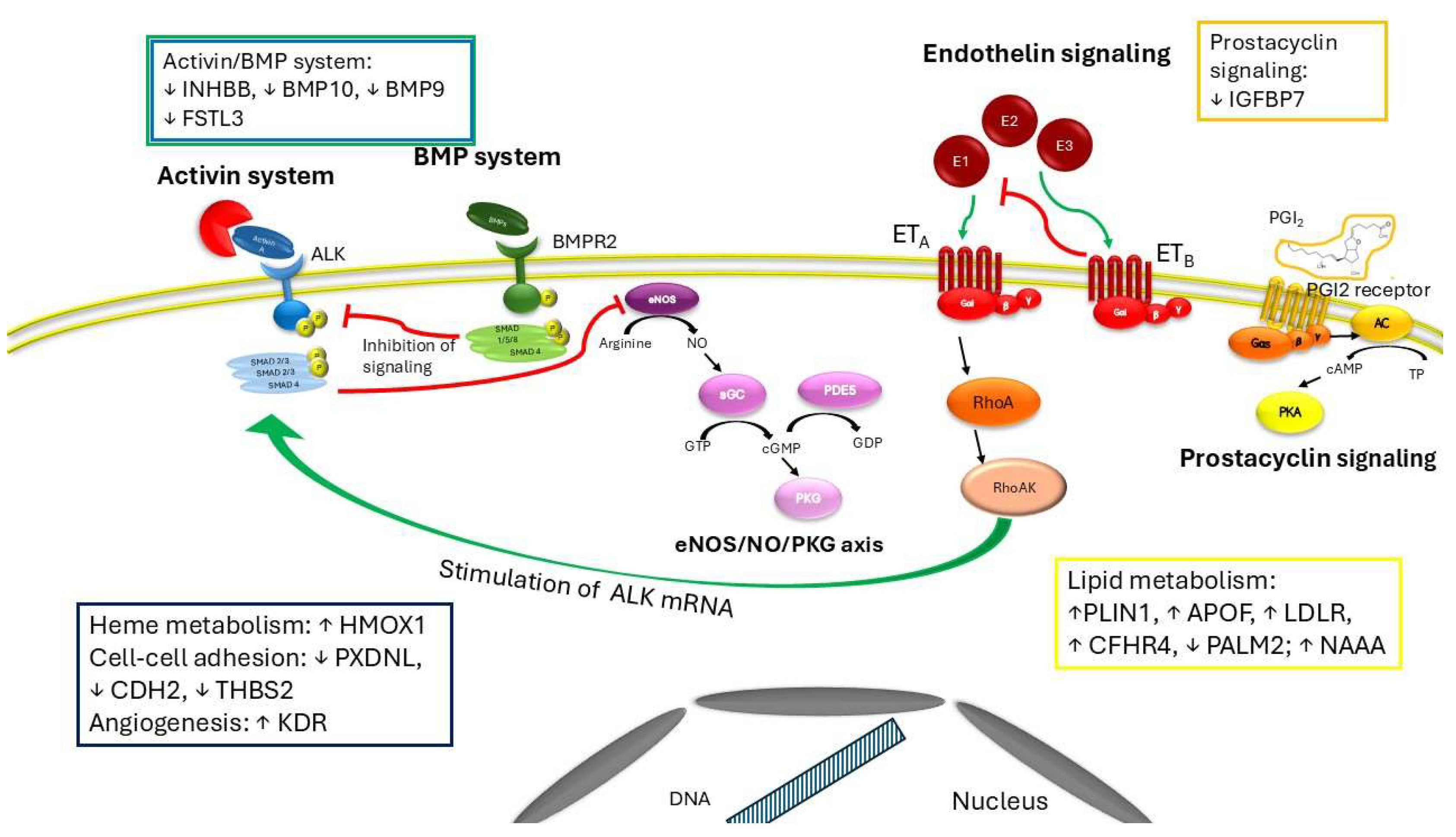

3. Sotatercept Beyond the Antiremodelling Effect: Impact on Cell Metabolism and Regulation

Complementary experimental and genetic models of PAH reveal therapeutic anti-inflammatory activities of ActRIIA-Fc that, together with its known anti-proliferative effects on vascular cell types, could underline clinical activity of sotatercept as either monotherapy or add-on to current PAH therapies (41). Proteomics analysis of circulating biomarkers in PAH patients treated with sotatercept for 24 weeks compared to placebo reveals a different expression of several proteins implicated in various cell processes (35). Among them, authors found a downregulation in inhibin subunit beta B (INHBB) expression, a preproprotein which is proteolytically cleaved to generate a subunit of the dimeric activin and inhibin protein complexes. Sotatercept treatment alters also markers involved in recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells and in oxidative stress and, among those downregulated, there is also the insulin-like growth factor binding protein 7 (IGFBP7), which binds IGF-I and IGF-II with relatively low affinity and stimulates prostacyclin production and cell adhesion. Sotatercept affects also proteins implicated in lipid metabolism. Perilipin1 (PLIN1), apoprotein F (APOF), LDL receptor (LDLR), complement factor H related 4 (CFHR4), paralemmin (PALM2), N-acylethanolamine acid amidase (NAAA), are all proteins involved in the metabolism of complex lipids or lipid transport through lipoproteins. Interestingly, except for PALM2, they are all upregulated. Low density lipoproteins (LDLs) can bind to activin A receptor-like kinase 1 with lower affinity than LDL receptors of on cell surface, promoting transcytosis in endothelial cells (42, 43). The binding is saturated only at hypercholesterolemic concentrations and avoids the lysosomal degradation (42). Interestingly, according to Savale et al (35) in PAH patients treated with sotatercept the LDL receptor is upregulated compared to placebo, indicating a compensatory mechanism due to lack of activin A. Furthermore, sotatercept, preventing activation of Smad2/3 pathway by trapping activins or GDF11, reverses the process that leads to hematological disorders related to abnormal activin signaling. Blunting the activin system induces a blocking of erythroid progenitor cell differentiation and of excessive numbers of immature erythroblasts, re-establishes the erythroid progenitor cell development or osteoblast differentiation, leading to an overall increase of hemoglobin and hematocrit (10) (

Figure 2).

4. Hematological and Vascular Effects of Sotatercept

The most common adverse events that occurred with sotatercept than with placebo include epistaxis, dizziness, skin telangiectasia, increased hemoglobin levels, thrombocytopenia, and increased blood pressure (45, 46). In STELLAR, one instance of gastrointestinal bleeding was noted in the treatment group. Overall, bleeding events were higher in the sotatercept group compared with placebo, although they were not associated with a decrease in platelet numbers. Treatment with sotatercept increases the expression of the inducible heme oxygenase-1 (HMOX1) (35). This enzyme belongs to the heme oxygenase family and catabolizes the heme group to form biliverdin, which is further metabolized to bilirubin and carbon monoxide by biliverdin reductase. The role of overexpression of HMOX1 is still controversial and contrasting results are reported. In experimental models of intracerebral hemorrhage its overexpression induces proinflammatory response in microglia and disrupts the balance of iron metabolism (47, 48), while in astrocytes or in a subarachnoid hemorrhage mouse model HMOX-1 overexpression provides neuroprotective effects against intracerebral hemorrhage (49, 50) or against Dengue virus-induced vascular endothelial dysfunction and leakage (51). Interestingly, sotatercept reduces the expression of follistatin like 3 (FSTL3) (35) that is strong inhibitor of activin system but exerts a weak inhibitory effect on BMP signaling (52). Furthermore, FSTL3 cooperates with integrins in regulating the adhesion of hematopoietic cells to fibronectin (52) and seems to promote vascular endothelial cells from induced pluripotent stem cells by upregulating endothelin-1 (53). Accordingly, BMP9 and BMP10 are downregulated in sotatercept treatment (35), worsening the pathological spectrum towards vascular lesions, abnormal blood vessels and hereditary heamorragic telangiectasia, in which vascular endothelial cells show an hyperactivation of the VEGFR2 pathways (35). Consistently with these findings, Savale et al 2024 found also an increase of expression of KDR (kinase insert domain receptor) which is a type III receptor tyrosine kinase, one of the two receptors for the VEGF (35). Peroxidasin-like (PXDNL) is another marker downregulated by sotatercept (35), it belongs to the peroxidase gene family and is highly expressed in the cardiovascular system. Early studies indicate that PXDNL is involved in the extracellular matrix formation with the potential of antagonizing PXDN activity (54). Lastly, also other proteins such as cadherin 2 (CDH2, N-cadherin) and thrombospondin 2 (THBS2), which are involved in cell-cell adhesion and in maintaining tissue integrity and cell proliferation, are downregulated in presence of sotatercept, (35). Given the above, alteration in expression of these markers may contribute to the adverse effects encountered during the treatment with sotatercept (Figure 2).

5. Effects of RAP-011, the Murine Orthologue of Sotatercept, in Experimental Models of Hematologic Disorders

Preclinical evaluation of sotatercept has been widely performed in in vivo and in vitro experimental models of blood diseases and pulmonary hypertension with the aim of better understanding the crosstalk between the BMP and activin signaling which are often compromised in anemia (10). Erythropoiesis is a process which can be affected by imbalance between activin and BMP signaling pathway, leading to a reduction in red blood cells production and, thereby, in various forms of anemia. Since sotatercept is a chimeric protein containing the extracellular domain of the activin receptor 2A (ACVR2A) fused to the Fc domain of human IgG1, in preclinical studies its murinized counterpart, RAP-011, which is composed by the soluble extracellular domain of ActRIIA fused to a murine IgG2a-Fc (55), has been widely assessed. In 2016 authors observed that the infusion of RAP-011 in mice produced a rapid increase in hematocrit, hemoglobin levels and in red blood cell count; these effects were attributed to the ability of RAP011 to revert the inhibition induced by activin system on late-stage erythroid precursors in the bone marrow and to enhance erythropoietin and erythroid burst-forming units (56). Interestingly, RAP-011 required bone marrow accessory cells to rescue inhibition evoked by activin signaling and, thereby, to restore physiological erythropoiesis (56). To better understand the mechanism underlying blood disorder and the efficacy of RAP-011 in vivo, several models of anemia were produced. Ear et al in 2015, produced a zebrafish model harboring a mutation mimicking the dysfunction of 5q-syndrome, a form of myelodysplastic syndrome (57). In a model representative of Diamond Blackfan anemia, the RPL11 ribosome-deficient zebrafish, administration of RAP-011 produced a remarkable increase in hemoglobin concentration by stimulating erythropoiesis through the sequester of lefty1, likely being implicated as a signaling marker in erythroid cell development (58). Recently, RAP-011 was found effective also in a model of congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type II, an anemia characterized by ineffective erythropoiesis due to maturation arrest of erythroid precursors (59). The study demonstrated that the administration of RAP-011 could increase hemoglobin concentration in transgenic and wild type models without inducing splenic depletion of iron store, as differently observed upon infusion of erythropoietin, indicating that sotatecept may have a role in in the management of iron overload in patients with congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type II. In the transgenic mice the mechanism involved a restoring of gene expression of erythroid markers by inhibiting of the phospoSMAD2 pathway (59). RAP-011 was also evaluated in a mouse model of β-thalassemia intermedia (21). As reported, treatment with RAP-011 ameliorated ineffective erythropoiesis, corrected anemia and limited iron overload, as already observed in other animal models, by acting as a binding trap for GDF11. The inhibition of the overstimulation of GDF11 signaling improved β-thalassemia effects by reducing the abnormal production of reactive oxygen species and the precipitation of α-globin membranes and by favouring a balance between immature/mature erythroblasts via apoptosis (21). Several studies performed in in vitro models have confirmed in vivo findings and improved the comprehension of the underlying mechanisms. In 2012, Iancu-Rubin et al (60) observed that ACE-011 (sotatercept) did not directly affect erythroid differentiation of human CD34(+) cells but could improve erythropoiesis inhibited by conditioned media produced by bone marrow stromal cells, indicating that ACE-011 might influence the production of inhibitory factors from bone marrow stromal cells. It is interesting to point out that, since the activin signaling system is strictly connected also to the bone morphogenesis, preclinical studies have been addressed to evaluate treatments with RAP-011 even in experimental models of mineral and bone disorders which often are associated to chronic kidney and cardiovascular disease (61, 62). Early studies in female cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) treatments with ACE-011 could produce an improvement of bone strength and matrix mineralization by rebalancing bone resorption and formation, which are impaired by overstimulation of activin pathway (63). In a rat model of closed fracture RAP-011 was able to promote bone formation during repair, but not to optimize callus bone quality (64).

In conclusion, preclinical evidence evaluated in vivo and in vitro experimental models indicates that sotatecept can restore functional erythropoiesis and bone formation by inhibiting activin signaling, indicating could be a new drug strategy.

6. Sotatecept in Hematological Clinical Studies: A Summary of Findings

According to preclinical studies, sotatercept and its murinized analogue exhibit the ability to restore erythropoiesis and bone formation. Similar findings have been observed in clinical trials. In the first clinical trial on healty postmenopausal women, sotatercept produced a significant and persistent improvement in reverting erythropoiesis and bone mineral density (65). In a phase IIa trail, sotatercept was administered at different concentrations (0,1- 0,5 mg/kg vs placebo) to patients affected by multiple myeloma for four weeks-cycles, combination with oral therapy of melphalan, prednisolone, and thalidomide. Sotatercept enhanced hemoglobin levels compared to baseline as well as the duration of the increase vs placebo. Moreover, anabolic improvements in bone mineral density and in bone formation were recorded. Multiple doses of sotatercept with the combined treatment appeared safe and generally well-tolerated by patients (66). In Phase II studies, administration of sotatercept in patients with metastatic breast cancer or with solid tumors treated with platinum-based chemotherapy induced an increase in hemoglobin of ≥1.0 g/dL (67). In these clinical trials sotatercept proved to be effective with a safety profile in the treatment of anemia which was evoked by cancer therapies. In the prospective, open-label, single-institution, investigator-initiated Phase-II clinical study 56 anemic patients with primary myelofibrosis or post polycythemia vera/essential thrombocythemia myelofibrosis were enrolled (68). The study also included patients who were already in ruxolitinib therapy. The primary endpoint of the study was achieved by 30% of patients in 84 days either in monotherapy with sotatercept or combination therapy with ruxolitinib, with a duration of response ranging up to 9 years (approximately 23 and 20 months in monotherapy and combination therapy respectively. Participants in combination therapy experienced more serious adverse effects (48%) then patients in monotherapy patients (31%). The most frequent ( > 5%) serious adverse events were anemia, fever, infection and neoplasms, while the most common minor adverse event were gastrointestinal disorders, pain, bleeding and flu like symptoms. The open-label, dose-finding, multicenter Phase II study (NCT01571635) randomized 16 adults with transfusion-dependent β -thalassemia and 30 adults with non-transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia to sotatercept versus placebo for two years. The study met its primary and secondary outcomes, observing a significant reduction in transfusion burden in patients with transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia, and an increase in hemoglobin levels from baseline in patients with non-transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia over 12 weeks. Sotatercept was overall effective and well tolerated since all patients in the study experienced non-serious adverse effects, mainly abdominal pain and other gastrointestinal disorders (68). The multicenter, open-label, dose-funding Phase II clinical study (NCT01736683) enrolled 74 adult patients with anemia and low or intermediate-1 risk myelodysplastic syndromes or nonproliferative chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) and who were ineligible for or refractory to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs). Sotatercept was randomly administered at doses 0,1 and 0,3 mg/kg and in a nonrandomly at 0,5, 1, and 2 mg/kg doses. The primary endpoint was to determine the dose that achieved haematological erythroid improvement (HI-E), prior to completion of five treatment cycles, defined as an increase of >1.5 g/dL hemoglobin or a decrease of >4 units of transfused RBCs, both maintained for 56 days over a period of 8 weeks. Sotatercept (0,3 mg/kg) was effective in improving anemia and in reducing RBC transfusion, in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (69).

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Sotatercept, in sequential combination with background therapy and for a duration of 24 weeks of treatment, has demonstrated an unequivocal improvement in several functional and haemodynamic endpoints in patients with PAH group 1 (idiopathic, heritable, drug- or toxin-induced, associated with connective tissue disease or associated with corrected congenital shunts). In particular, sotatercept improved the hard endpoint of time to clinical worsening,

Despite this, attention must be paid to the side effects of the drug, whose actions range from the pulmonary circulation, to the vessels, to cellular metabolism and to the blood.

Although the results indicate that the administration of sotatercept is well tolerated in anemic patients, there are no data on the effects in non-anemic patients and in the long-term follow-up. In particular, it is not known what the effect of the increase in hemoglobin concentration and red blood cell counts may be in non-anemic patients with PAH. Likewise, the incidence of bleeding in patients treated with sotatercept and the possible long-term clinical implications are unknown. Further studies with higher sample size are needed to better define the safety of the drug and its efficacy, especially in the long term, both in the hematological field and in PAH.

Author Contributions

RM contributed to the conception of the manuscript; RM and SG wrote the manuscript; RM critically reviewed the final draft.

Funding

This work is supported by the European Union—Next-Generation EU through the Italian Ministry of University and Research under PNRR—M4C2-I1.3 Project PE_00000019 “HEAL ITALIA”, CUP I53C22001440006, and PNRR-MR1-2022-12376879 (to RM).

Institutional Review Board Statement

In this section, you should add the Institutional Review Board Statement and approval number, if relevant to your study. You might choose to exclude this statement if the study did not require ethical approval. Please note that the Editorial Office might ask you for further information. Please add “The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving humans. OR “The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving animals. OR “Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Any research article describing a study involving humans should contain this statement. Please add “Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.” OR “Patient consent was waived due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable.” for studies not involving humans. You might also choose to exclude this statement if the study did not involve humans. Written informed consent for publication must be obtained from participating patients who can be identified (including by the patients themselves

Conflicts of Interest

No conflict of interest declared on this topic

References

- M, Kovacs G, Hoeper MM, Badagliacca R, Berger RMF, Brida M, et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Vol. 61, European Respiratory Journal. European Respiratory Society; 2023. [CrossRef]

- Souza R, Badesch DB, Ghofrani HA, Gibbs JSR, Gomberg-Maitland M, McLaughlin VV, Preston IR, Waxman AB, Grünig E, Kopeć G, Meyer G, Olsson KM, Rosenkranz S, Lin J, Johnson-Levonas AO, de Oliveira Pena J, Humbert M, Hoeper MM. Effects of sotatercept on haemodynamics and right heart function: analysis of the STELLAR trial. Eur Respir J. 2023 Sep 21;62(3):2301107. [CrossRef]

- Joshi SR, Liu J, Bloom T, Karaca Atabay E, Kuo TH, Lee M, Belcheva E, Spaits M, Grenha R, Maguire MC, Frost JL, Wang K, Briscoe SD, Alexander MJ, Herrin BR, Castonguay R, Pearsall RS, Andre P, Yu PB, Kumar R, Li G. Sotatercept analog suppresses inflammation to reverse experimental pulmonary arterial hypertension. Sci Rep. 2022 May 12;12(1):7803. [CrossRef]

- Madonna R, Biondi F. Perspectives on Sotatercept in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. J Clin Med. 2024 Oct 28;13(21):6463. [CrossRef]

- Madonna R, Biondi F. Sotatercept: New drug on the horizon of pulmonary hypertension. Vascul Pharmacol. 2024 Nov 19:107442. [CrossRef]

- ung LM, Yang P, Joshi S, Augur ZM, Kim SSJ, Bocobo GA, Dinter T, Troncone L, Chen PS, McNeil ME, Southwood M, Poli de Frias S, Knopf J, Rosas IO, Sako D, Pearsall RS, Quisel JD, Li G, Kumar R, Yu PB. ACTRIIA-Fc rebalances activin/GDFversus BMP signaling in pulmonary hypertension. Sci Transl Med. 2020 May 13;12(543):eaaz5660. [CrossRef]

- Santibanez JF, Blanco FJ, Garrido-Martin EM, Sanz-Rodriguez F, del Pozo MA, Bernabeu C. Caveolin-1 interacts and cooperates with the transforming growth factor-beta type I receptor ALK1 in endothelial caveolae. Cardiovasc Res. 2008 Mar 1;77(4):791-9. [CrossRef]

- Yong HE, Murthi P, Wong MH, Kalionis B, Cartwright JE, Brennecke SP, Keogh RJ. Effects of normal and high circulating concentrations of activin A on vascular endothelial cell functions and vasoactive factor production. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2015 Oct;5(4):346-53. [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto K, Yokokawa T, Misaka T, Kaneshiro T, Yamada S, Yoshihisa A, Nakazato K, Takeishi Y. Endothelin-1 Upregulates Activin Receptor-Like Kinase-1 Expression via Gi/RhoA/Sp-1/Rho Kinase Pathways in Human Pulmonary Arterial Endothelial Cells. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021 Feb 23;8:648981. [CrossRef]

- Lan Z, Lv Z, Zuo W, Xiao Y. From bench to bedside: The promise of sotatercept in hematologic disorders. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023 Sep;165:115239. [CrossRef]

- Meunier H, Cajander SB, Roberts VJ, Rivier C, Sawchenko PE, Hsueh AJ, Vale W. Rapid changes in the expression of inhibin alpha-, beta A-, and beta B-subunits in ovarian cell types during the rat estrous cycle. Mol Endocrinol. 1988 Dec;2(12):1352-63. [CrossRef]

- Olsen OE, Hella H, Elsaadi S, Jacobi C, Martinez-Hackert E, Holien T. Activins as Dual Specificity TGF-β Family Molecules: SMAD-Activation via Activin- and BMP-Type 1 Receptors. Biomolecules. 2020 Mar 29;10(4):519. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stump B, Waxman AB. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension and TGF-β Superfamily Signaling: Focus on Sotatercept. BioDrugs. 2024 Nov;38(6):743-753. [CrossRef]

- Namwanje M, Brown CW. Activins and Inhibins: Roles in Development, Physiology, and Disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016 Jul 1;8(7):a021881. [CrossRef]

- Ye Q, Taleb SJ, Zhao J, Zhao Y. Emerging role of BMPs/BMPR2 signaling pathway in treatment for pulmonary fibrosis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024 Sep;178:117178. [CrossRef]

- Gkarmiris KI, Lindbäck J, Alexander JH, Granger CB, Kastner P, Lopes RD, Ziegler A, Oldgren J, Siegbahn A, Wallentin L, Hijazi Z. Repeated Measurement of the Novel Atrial Biomarker BMP10 (Bone Morphogenetic Protein 10) Refines Risk Stratification in Anticoagulated Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: Insights From the ARISTOTLE Trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024 Apr 2;13(7):e033720. [CrossRef]

- Liu L, Liang Y, Lan QG, Chen JZ, Wang R, Zhao JH, Liang B. Bone morphogenetic protein 10 and atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2024 Mar 8;51:101376. PMCID: PMC10943040. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Sun H, Yu H, Du B, Fan Q, Jia B, Zhang Z. Bone morphogenetic protein 10, a rising star in the field of diabetes and cardiovascular disease. J Cell Mol Med. 2024 May;28(10):e18324. [CrossRef]

- Capasso TL, Li B, Volek HJ, Khalid W, Rochon ER, Anbalagan A, Herdman C, Yost HJ, Villanueva FS, Kim K, Roman BL. BMP10-mediated ALK1 signaling is continuously required for vascular development and maintenance. Angiogenesis. 2020 May;23(2):203-220. [CrossRef]

- Yu J, Dolter KE. Production of activin A and its roles in inflammation and hematopoiesis. Cytokines Cell Mol Ther. 1997 Sep;3(3):169-77.

- Dussiot M, Maciel TT, Fricot A, Chartier C, Negre O, Veiga J, Grapton D, Paubelle E, Payen E, Beuzard Y, Leboulch P, Ribeil JA, Arlet JB, Coté F, Courtois G, Ginzburg YZ, Daniel TO, Chopra R, Sung V, Hermine O, Moura IC. An activin receptor IIA ligand trap corrects ineffective erythropoiesis in β-thalassemia. Nat Med. 2014 Apr;20(4):398-407. [CrossRef]

- De Rosa G, Andolfo I, Marra R, Manna F, Rosato BE, Iolascon A, Russo R. RAP-011 Rescues the Disease Phenotype in a Cellular Model of Congenital Dyserythropoietic Anemia Type II by Inhibiting the SMAD2-3 Pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Aug 4;21(15):5577. [CrossRef]

- Li W, Quigley K. Bone morphogenetic protein signalling in pulmonary arterial hypertension: revisiting the BMPRII connection. Biochem Soc Trans. 2024 Jun 26;52(3):1515-1528. [CrossRef]

- Jerkic M, Kabir MG, Davies A, Yu LX, McIntyre BA, Husain NW, Enomoto M, Sotov V, Husain M, Henkelman M, Belik J, Letarte M. Pulmonary hypertension in adult Alk1 heterozygous mice due to oxidative stress. Cardiovasc Res. 2011 Dec 1;92(3):375-84. [CrossRef]

- Girerd B, Montani D, Coulet F, Sztrymf B, Yaici A, Jaïs X, Tregouet D, Reis A, Drouin-Garraud V, Fraisse A, Sitbon O, O'Callaghan DS, Simonneau G, Soubrier F, Humbert M. Clinical outcomes of pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients carrying an ACVRL1 (ALK1) mutation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010 Apr 15;181(8):851-61. [CrossRef]

- Eswaran H, Kasthuri RS. Potential and emerging therapeutics for HHT. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2024 Dec 6;2024(1):724-727. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasheed A, Aslam S, Sadiq HZ, Ali S, Syed R, Panjiyar BK. New and Emerging Therapeutic Drugs for the Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2024 Aug 29;16(8):e68117. [CrossRef]

- Frantz RP, Desai SS, Ewald G, Franco V, Hage A, Horn EM, LaRue SJ, Mathier MA, Mandras S, Park MH, Ravichandran AK, Schilling JD, Wang IW, Zolty R, Rendon GG, Rocco MA, Selej M, Zhao C, Rame JE. SOPRANO: Macitentan in patients with pulmonary hypertension following left ventricular assist device implantation. Pulm Circ. 2024 Dec 4;14(4):e12446. [CrossRef]

- Shihoya W, Sano FK, Nureki O. Structural insights into endothelin receptor signalling. J Biochem. 2023 Sep 29;174(4):317-325. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman JH, Kar S, Kirkpatrick P. Ambrisentan. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007 Sep;6(9):697-8. [CrossRef]

- Shihoya W, Sano FK, Nureki O. Structural insights into endothelin receptor signalling. J Biochem. 2023 Sep 29;174(4):317-325. [CrossRef]

- Dhaun N, Webb DJ. Endothelins in cardiovascular biology and therapeutics. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019 Aug;16(8):491-502. [CrossRef]

- Gawrys O, Kala P, Sadowski J, Melenovský V, Sandner P, Červenka L. Soluble guanylyl cyclase stimulators and activators: Promising drugs for the treatment of hypertension? Eur J Pharmacol. 2025 Jan 15;987:177175. [CrossRef]

- Weatherald J, Varughese RA, Liu J, Humbert M. Management of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2023 Dec;44(6):746-761. [CrossRef]

- Savale L, Tu L, Normand C, Boucly A, Sitbon O, Montani D, Olsson KM, Park DH, Fuge J, Kamp JC, Humbert M, Hoeper MM, Guignabert C. Effect of sotatercept on circulating proteomics in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2024 Oct 31;64(4):2401483. [CrossRef]

- Torres G, Lancaster AC, Yang J, Griffiths M, Brandal S, Damico R, Vaidya D, Simpson CE, Martin LJ, Pauciulo MW, Nichols WC, Ivy DD, Austin ED, Hassoun PM, Everett AD. Low-affinity insulin-like growth factor binding protein 7 and its association with pulmonary arterial hypertension severity and survival. Pulm Circ. 2023 Sep 4;13(3):e12284. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Yuan M, Cai W, Sun W, Shi X, Liu D, Song W, Yan Y, Chen T, Bao Q, Zhang B, Liu T, Zhu Y, Zhang X, Li G. Prostaglandin I2 signaling prevents angiotensin II-induced atrial remodeling and vulnerability to atrial fibrillation in mice. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2024 Jun 15;81(1):264. [CrossRef]

- Zeng C, Liu J, Zheng X, Hu X, He Y. Prostaglandin and prostaglandin receptors: present and future promising therapeutic targets for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Respir Res. 2023 Nov 1;24(1):263. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Yuan M, Cai W, Sun W, Shi X, Liu D, Song W, Yan Y, Chen T, Bao Q, Zhang B, Liu T, Zhu Y, Zhang X, Li G. Prostaglandin I2 signaling prevents angiotensin II-induced atrial remodeling and vulnerability to atrial fibrillation in mice. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2024 Jun 15;81(1):264. [CrossRef]

- Wang P, Deng J, Zhang Q, Feng H, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Han L, Yang P, Deng Z. Additional Use of Prostacyclin Analogs in Patients With Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: A Meta-Analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2022 Feb 9;13:817119. [CrossRef]

- Joshi SR, Liu J, Bloom T, Karaca Atabay E, Kuo TH, Lee M, Belcheva E, Spaits M, Grenha R, Maguire MC, Frost JL, Wang K, Briscoe SD, Alexander MJ, Herrin BR, Castonguay R, Pearsall RS, Andre P, Yu PB, Kumar R, Li G. Sotatercept analog suppresses inflammation to reverse experimental pulmonary arterial hypertension. Sci Rep. 2022 May 12;12(1):7803. [CrossRef]

- Kraehling JR, Chidlow JH, Rajagopal C, Sugiyama MG, Fowler JW, Lee MY, Zhang X, Ramírez CM, Park EJ, Tao B, Chen K, Kuruvilla L, Larriveé B, Folta-Stogniew E, Ola R, Rotllan N, Zhou W, Nagle MW, Herz J, Williams KJ, Eichmann A, Lee WL, Fernández-Hernando C, Sessa WC. Genome-wide RNAi screen reveals ALK1 mediates LDL uptake and transcytosis in endothelial cells. Nat Commun. 2016 Nov 21;7:13516. [CrossRef]

- Fung KYY, Ho TWW, Xu Z, Neculai D, Beauchemin CAA, Lee WL, Fairn GD. Apolipoprotein A1 and high-density lipoprotein limit low-density lipoprotein transcytosis by binding SR-B1. J Lipid Res. 2024 Apr;65(4):100530. [CrossRef]

- Lan Z, Lv Z, Zuo W, Xiao Y. From bench to bedside: The promise of sotatercept in hematologic disorders. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023 Sep;165:115239. [CrossRef]

- Hoeper MM, Badesch DB, Ghofrani HA, Gibbs JSR, Gomberg-Maitland M, McLaughlin VV, Preston IR, Souza R, Waxman AB, Grünig E, Kopeć G, Meyer G, Olsson KM, Rosenkranz S, Xu Y, Miller B, Fowler M, Butler J, Koglin J, de Oliveira Pena J, Humbert M; STELLAR Trial Investigators. Phase 3 Trial of Sotatercept for Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2023 Apr 20;388(16):1478-1490. [CrossRef]

- Humbert M, McLaughlin V, Gibbs JSR, Gomberg-Maitland M, Hoeper MM, Preston IR, Souza R, Waxman A, Escribano Subias P, Feldman J, Meyer G, Montani D, Olsson KM, Manimaran S, Barnes J, Linde PG, de Oliveira Pena J, Badesch DB; PULSAR Trial Investigators. Sotatercept for the Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2021 Apr 1;384(13):1204-1215. [CrossRef]

- Liu Q, Han Z, Li T, Meng J, Zhu C, Wang J, Wang J, Zhang Z, Wu H. Microglial HO-1 aggravates neuronal ferroptosis via regulating iron metabolism and inflammation in the early stage after intracerebral hemorrhage. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025 Feb 6;147:113942. [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi K, Lambein F, Kusama-Eguchi K. Vascular insult accompanied by overexpressed heme oxygenase-1 as a pathophysiological mechanism in experimental neurolathyrism with hind-leg paraparesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012 Nov 9;428(1):160-6. [CrossRef]

- Chen-Roetling J, Kamalapathy P, Cao Y, Song W, Schipper HM, Regan RF. Astrocyte heme oxygenase-1 reduces mortality and improves outcome after collagenase-induced intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurobiol Dis. 2017 Jun;102:140-146. [CrossRef]

- Gao Q, Su Z, Pang X, Chen J, Luo R, Li X, Zhang C, Zhao Y. Overexpression of Heme Oxygenase 1 Enhances the Neuroprotective Effects of Exosomes in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage by Suppressing Oxidative Stress and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Mol Neurobiol. 2024 Dec 22. [CrossRef]

- Wu YH, Chen WC, Tseng CK, Chen YH, Lin CK, Lee JC. Heme oxygenase-1 inhibits DENV-induced endothelial hyperpermeability and serves as a potential target against dengue hemorrhagic fever. FASEB J. 2022 Jan;36(1):e22110. [CrossRef]

- Tian S, Xu X, Yang X, Fan L, Jiao Y, Zheng M, Zhang S. Roles of follistatin- like protein 3 in human non-tumor pathophysiologies and cancers. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022 Oct 17;10:953551. [CrossRef]

- Kelaini S, Vilà-González M, Caines R, Campbell D, Eleftheriadou M, Tsifaki M, Magee C, Cochrane A, O'neill K, Yang C, Stitt AW, Zeng L, Grieve DJ, Margariti A. Follistatin-Like 3 Enhances the Function of Endothelial Cells Derived from Pluripotent Stem Cells by Facilitating β-Catenin Nuclear Translocation Through Inhibition of Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3β Activity. Stem Cells. 2018 Jul;36(7):1033-1044. [CrossRef]

- Péterfi Z, Tóth ZE, Kovács HA, Lázár E, Sum A, Donkó A, Sirokmány G, Shah AM, Geiszt M. Peroxidasin-like protein: a novel peroxidase homologue in the human heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2014 Mar 1;101(3):393-9. [CrossRef]

- Pearsall RS, Canalis E, Cornwall-Brady M, Underwood KW, Haigis B, Ucran J, Kumar R, Pobre E, Grinberg A, Werner ED, Glatt V, Stadmeyer L, Smith D, Seehra J, Bouxsein ML. A soluble activin type IIA receptor induces bone formation and improves skeletal integrity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 May 13;105(19):7082-7. [CrossRef]

- Carrancio S, Markovics J, Wong P, Leisten J, Castiglioni P, Groza MC, Raymon HK, Heise C, Daniel T, Chopra R, Sung V. An activin receptor IIA ligand trap promotes erythropoiesis resulting in a rapid induction of red blood cells and haemoglobin. Br J Haematol. 2014 Jun;165(6):870-82. [CrossRef]

- Ear J, Hsueh J, Nguyen M, Zhang Q, Sung V, Chopra R, Sakamoto KM, Lin S. A Zebrafish Model of 5q-Syndrome Using CRISPR/Cas9 Targeting RPS14 Reveals a p53-Independent and p53-Dependent Mechanism of Erythroid Failure. J Genet Genomics. 2016 May 20;43(5):307-18. [CrossRef]

- Ear J, Huang H, Wilson T, Tehrani Z, Lindgren A, Sung V, Laadem A, Daniel TO, Chopra R, Lin S. RAP-011 improves erythropoiesis in zebrafish model of Diamond- Blackfan anemia through antagonizing lefty1. Blood. 2015 Aug 13;126(7):880-90. [CrossRef]

- De Rosa G, Andolfo I, Marra R, Manna F, Rosato BE, Iolascon A, Russo R. RAP-011 Rescues the Disease Phenotype in a Cellular Model of Congenital Dyserythropoietic Anemia Type II by Inhibiting the SMAD2-3 Pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Aug 4;21(15):5577. [CrossRef]

- Iancu-Rubin C, Mosoyan G, Wang J, Kraus T, Sung V, Hoffman R. Stromal cell- mediated inhibition of erythropoiesis can be attenuated by Sotatercept (ACE-011), an activin receptor type II ligand trap. Exp Hematol. 2013 Feb;41(2):155-166.e17.

- Williams MJ, Sugatani T, Agapova OA, Fang Y, Gaut JP, Faugere MC, Malluche HH, Hruska KA. The activin receptor is stimulated in the skeleton, vasculature, heart, and kidney during chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2018 Jan;93(1):147-158. [CrossRef]

- Sugatani T, Agapova OA, Fang Y, Berman AG, Wallace JM, Malluche HH, Faugere MC, Smith W, Sung V, Hruska KA. Ligand trap of the activin receptor type IIA inhibits osteoclast stimulation of bone remodeling in diabetic mice with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2017 Jan;91(1):86-95. [CrossRef]

- Fajardo RJ, Manoharan RK, Pearsall RS, Davies MV, Marvell T, Monnell TE, Ucran JA, Pearsall AE, Khanzode D, Kumar R, Underwood KW, Roberts B, Seehra J, Bouxsein ML. Treatment with a soluble receptor for activin improves bone mass and structure in the axial and appendicular skeleton of female cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis). Bone. 2010 Jan;46(1):64-71. [CrossRef]

- Morse A, Cheng TL, Peacock L, Mikulec K, Little DG, Schindeler A. RAP-011 augments callus formation in closed fractures in rats. J Orthop Res. 2016 Feb;34(2):320-30.

- Sherman ML, Borgstein NG, Mook L, Wilson D, Yang Y, Chen N, Kumar R, Kim K, Laadem A. Multiple-dose, safety, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic study of sotatercept (ActRIIA-IgG1), a novel erythropoietic agent, in healthy postmenopausal women. J Clin Pharmacol. 2013 Nov;53(11):1121-30.

- Abdulkadyrov KM, Salogub GN, Khuazheva NK, Sherman ML, Laadem A, Barger R, Knight R, Srinivasan S, Terpos E. Sotatercept in patients with osteolytic lesions of multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2014 Jun;165(6):814-23. [CrossRef]

- Raftopoulos H, Laadem A, Hesketh PJ, Goldschmidt J, Gabrail N, Osborne C, Ali M, Sherman ML, Wang D, Glaspy JA, Puccio-Pick M, Zou J, Crawford J. Sotatercept (ACE-011) for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced anemia in patients with metastatic breast cancer or advanced or metastatic solid tumors treated with platinum-based chemotherapeutic regimens: results from two phase 2 studies. Support Care Cancer. 2016 Apr;24(4):1517-25. [CrossRef]

- Bose P, Masarova L, Pemmaraju N, Bledsoe SD, Daver NG, Jabbour EJ, Kadia TM, Estrov Z, Kornblau SM, Andreeff M, Jain N, Cortes JE, Borthakur G, Alvarado Y, Richie MA, Dobbins MH, McCrackin SA, Zhou L, Pierce SA, Wang X, Pike AM, Garcia- Manero G, Kantarjian HM, Verstovsek S. Sotatercept for anemia of myelofibrosis: a phase II investigator-initiated study. Haematologica. 2024 Aug 1;109(8):2660-2664. [CrossRef]

- Komrokji R, Garcia-Manero G, Ades L, Prebet T, Steensma DP, Jurcic JG, Sekeres MA, Berdeja J, Savona MR, Beyne-Rauzy O, Stamatoullas A, DeZern AE, Delaunay J, Borthakur G, Rifkin R, Boyd TE, Laadem A, Vo B, Zhang J, Puccio-Pick M, Attie KM, Fenaux P, List AF. Sotatercept with long-term extension for the treatment of anaemia in patients with lower risk myelodysplastic syndromes: a phase 2, dose-ranging trial. Lancet Haematol. 2018 Feb;5(2):e63-e72. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).