Submitted:

01 December 2023

Posted:

05 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

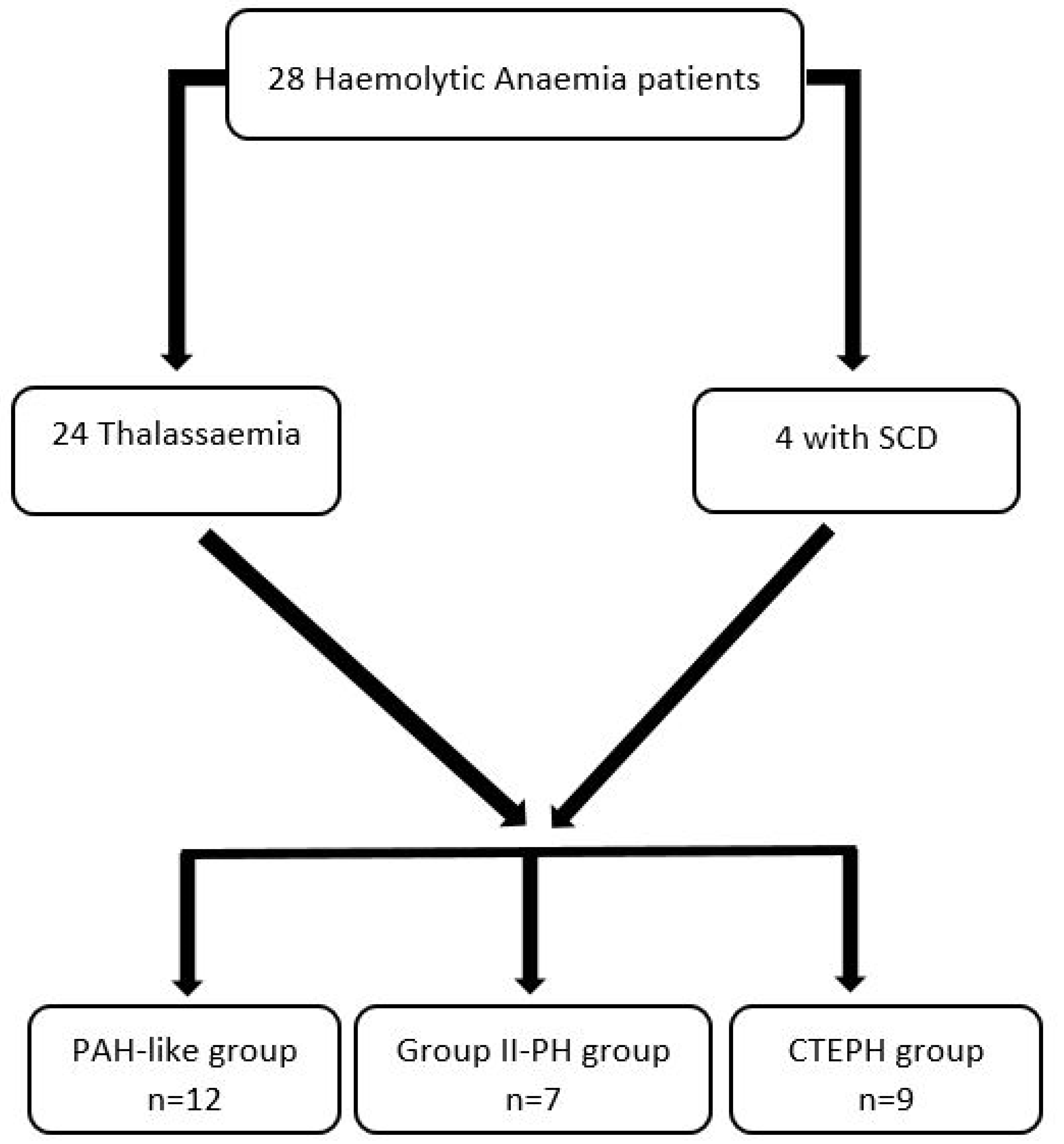

2.1. Patient selection

2.2. Data collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Haemodynamic and Echocardiographic Characteristics

3.2. Therapeutic approach

3.3. Hemodynamic Parameters at follow up

3.3.1. PAH-like group

3.3.2. PH Group II (PH-LHD)

3.3.3. CTEPH group

3.3.4. Haemodynamic Indices to predict the relevant PH diagnosis

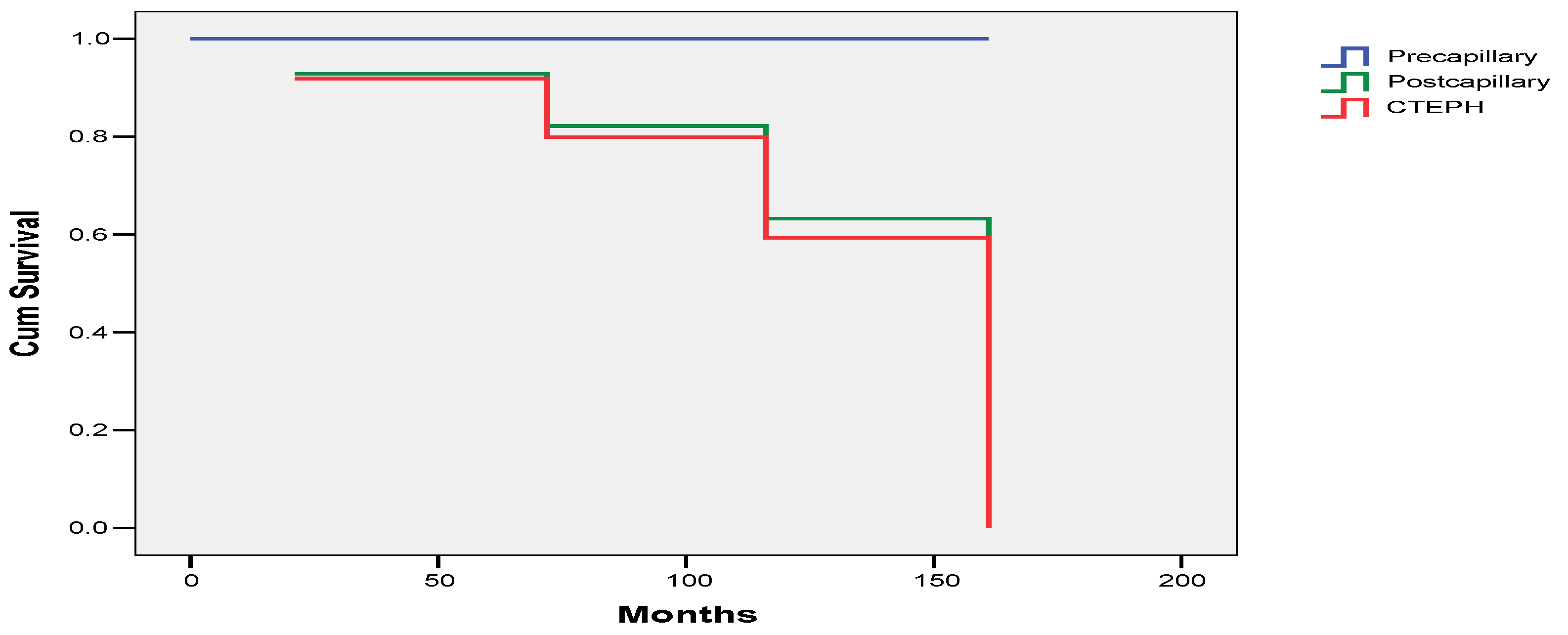

3.4. Survival

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

References

- Gladwin MT, Sachdev V, Jison ML, Shizukuda Y, Plehn JF, Minter K, et al. Pulmonary hypertension as a risk factor for death in patients with sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med 2004, 350, 886–895. [CrossRef]

- Savale L, Habibi A, Lionnet F, Maitre B, Cottin V, Jais X, et al. Clinical phenotypes and outcomes of precapillary pulmonary hypertension of sickle cell disease. Eur Respir J 2019, 54, 1900585. [CrossRef]

- Sutton LL, Castro O, Cross DJ, Spencer JE, Lewis JF. Pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease. Am J Cardiol 1994, 74, 626–628. [CrossRef]

- Derchi G, Galanello R, Bina P, Cappellini MD, Piga A, Lai ME, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for pulmonary arterial hypertension in a large group of beta-thalassemia patients using right heart catheterization: a Webthal study. Circulation 2014, 129, 338–345. [CrossRef]

- Humbert M, Kovacs G, Hoeper MM, Badagliacca R, Berger RMF, Brida M, Carlsen J, Coats AJS, Escribano-Subias P, Ferrari P, Ferreira DS, Ghofrani HA, Giannakoulas G, Kiely DG, Mayer E, Meszaros G, Nagavci B, Olsson KM, Pepke-Zaba J, Quint JK, Rådegran G, Simonneau G, Sitbon O, Tonia T, Toshner M, Vachiery JL, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Delcroix M, Rosenkranz S; ESC/ERS Scientific Document Group. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2022, 43, 3618–3731.

- Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, Gibbs S, Lang I, Torbicki A, Simonneau G, Peacock A, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Beghetti M, Ghofrani A, Gomez Sanchez MA, Hansmann G, Klepetko W, Lancellotti P, Matucci M, McDonagh T, Pierard LA, Trindade PT, Zompatori M, Hoeper M; ESC Scientific Document Group.2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J. 2016, 37, 67–119.

- D T Kremastinos, D P Tsiapras, G A Tsetsos, E I Rentoukas, H P Vretou, P K Toutouzas. Left ventricular diastolic Doppler characteristics inbeta-thalassemia major. Circulation 1993, 88, 1127–1135. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Aessopos, G Stamatelos, V Skoumas, G Vassilopoulos, M Mantzourani, D Loukopoulos Pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure inpatients with beta-thalassemia intermedia. Chest 1995, 107, 50–53. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasia Anthi, Stylianos E Orfanos, Apostolos Armaganidis. Pulmonary hypertension in β thalassaemia. Lancet Respir Med 2013, 1, 488–496.

- Alem Mehari, Elizabeth S Klings. Chronic Pulmonary Complications of Sickle Cell Disease. Chest 2016, 149, 1313–1324. [CrossRef]

- Valeria Maria Pinto, Khaled M Musallam, Giorgio Derchi, Giovanna Graziadei, Marianna Giuditta, Raffaella Origa, Susanna Barella, Gavino Casu, Annamaria Pasanisi, Filomena Longo et al. Mortality in β-thalassemia patients with confirmed pulmonary arterial hypertension on right heart catheterization. Blood 2022, 139, 2080–2083.

- Parent F, Bachir D, Inamo J, et al. A hemodynamic study of pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med 2011, 365, 44–53. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthi, D. Tsiapras, P. Karyofyllis, V. Voudris, A. Armaganidis, S. Orfanos. The wide spectrum of β-thalassaemia intermedia-induced pulmonary hypertension: two case reportson the possible role of specific pulmonary arteri-alhypertension therapy. Pulm Circ 2021, 11, 20458940211030490.

- Derchi G, Forni GL, Formisano F, Cappellini MD, Galanello R, D’Ascola G, et al. Efficacy and safety of sildenafil in the treatment of severe pulmonary hypertension in patients with hemoglobinopathies. Haematologica 2005, 90, 452–458.

- Machado RF, Martyr S, Kato GJ, Barst RJ, Anthi A, Robinson MR,et al. Sildenafi l therapy in patients with sickle cell disease and pulmonary hypertension. Br J Haematol 2005, 130, 445–453. [CrossRef]

- Minniti CP, Machado RF, Coles WA, Sachdev V, Gladwin MT, Kato GJ. Endothelin receptor antagonists for pulmonary hypertension in adult patients with sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol 2009, 147, 737–743. [CrossRef]

- Castro O, Hoque M, Brown BD. Pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease: Cardiac catheterization results and survival. Blood 2003, 101, 1257–1261. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymond L Benza, Dave P Miller, Robyn J Barst, David B Badesch, Adaani E Frost, Michael D McGoon. An evaluation of long-term survival from time of diagnosis in pulmonary arterial hypertension from the REVEAL Registry. Chest 2012, 142, 448–456. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghofrani HA, D’Armini AM, Grimminger F, Hoeper MM, Jansa P, Kim NH, et al. Riociguat for the treatment of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med 2013, 369, 319–329. [CrossRef]

- Sadushi-Kolici R, Jansa P, Kopec G, Torbicki A, Skoro-Sajer N, Campean IA, et al. Subcutaneous treprostinil for the treatment of severe non-operable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH): a double-blind, phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2019, 7, 239–248. [CrossRef]

- Ghofrani HA, Simonneau G, D’Armini AM, Fedullo P, Howard LS, Jais X, et al. Macitentan for the treatment of inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (MERIT-1): results from the multicentre, phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet Respir Med 2017, 5, 785–794.

- Xavier Jaïs 1, Philippe Brenot 2, Hélène Bouvaist 3, Mitja Jevnikar 4, Matthieu Canuet 5, Céline Chabanne 6, Ari Chaouat 7, Vincent Cottin 8, Pascal De Groote 9, Nicolas Favrolt 10, Delphine Horeau-Langlard 11, Pascal Magro 12, Laurent Savale 4, Grégoire Prévot 13, Sébastien Renard 14, Olivier Sitbon 4, Florence Parent 4, Romain Trésorier 15, Cécile Tromeur 16, Céline Piedvache 17, Lamiae Grimaldi 18, Elie Fadel 19, David Montani 4, Marc Humbert 4, Gérald Simonneau 4 Balloon pulmonary angioplasty versus riociguat for the treatment of inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (RACE): a multicentre, phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial and ancillary follow-up study. Lancet Respir Med 2022, 10, 961–971.

- Balakrishnan Mahesh, Martin Besser, Antonio Ravaglioli, Joanna Pepke-Zaba, Guillermo Martinez, Andrew Klein, Choo Ng, Steven Tsui, John Dunning, David P. Jenkins Author Notes Pulmonary endarterectomy is effective and safe in patients with haemoglobinopathies and abnormal red blood cells: the Papworth experience. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery 2016, 50, 537–541.

- Panagiotis Karyofyllis 1, Dimitris Tsiapras 2, Varvara Papadopoulou 3, Michael D Diamantidis 4, Paraskevi Fotiou 4, Eftychia Demerouti 2, Vassilis Voudris Balloon pulmonary angioplasty is a promising option in thalassemic patients with inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Case Reports J Thromb Thrombolysis 2018, 46, 516–520.

- Demerouti E, Karyofyllis P, Voudris V, Boutsikou M, Anastasiadis G, Anthi A, Arvanitaki A, Athanassopoulos G, Avgeropoulou A, Brili S, Feloukidis C, Frantzeskaki F, Karatasakis G, Karvounis H, Konstantonis D, Mitrouska I, Mouratoglou S, Naka KK, Orfanos SE, Panagiotidou E, Pitsiou G, Pitsis A, Stamatopoulou V, Stanopoulos I, Thomaidis A, Tsangaris I, Tsiapras D, Giannakoulas G, Manginas A, On Behalf Of The Hellenic Society For The Study Of Pulmonary Hypertension Hssph. Epidemiology and Management of Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension in Greece. Real-World Data from the Hellenic Pulmonary Hypertension Registry (HOPE). J Clin Med. 2021, 10, 4547.

- Karyofyllis P, Demerouti E, Giannakoulas G, Anthi A, Arvanitaki A, Athanassopoulos G, Feloukidis C, Iakovou I, Kostelidou T, Mitrouska I, Mouratoglou SA, Orfanos SE, Pappas C, Pitsiou G, Tsetika EG, Tsiapras D, Voudris V, Manginas A; Hellenic Society for the Study of Pulmonary Hypertension HSSPH. Balloon Pulmonary Angioplasty in Patients with Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension in Greece: Data from the Hellenic Pulmonary Hypertension Registry. J Clin Med. 2022, 11, 2211.

- Panagiotis Karyofyllis, Dimitrios Tsiapras, Eftychia Demerouti, Iakovos Armenis, Varvara Papadopoulou, Vassilis Voudris Sickle cell disease related chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: challenging clinical scenario. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2022, 53, 467–470. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PAH GROUP (group 1) | PH-LHD (group 2) | CTEPH GROUP (group 4) | p-value | |

| RAP (mmHg) | 7.7±0.4 | 13.5±3.7 | 11.5±5.3 | 0.029 (group 1 vs 2) |

| PASP (mmHg) | 57.6±12.8 | 55.8±15.5 | 83.6±10.5 | ≤ 0.01 (group 4 vs 1,2) |

| mPAP (mmHg) | 36±7.6 | 37.1±8.6 | 50.4±6.2 | ≤ 0.04 (group 4 vs 1,2) |

| PAWP (mmHg) | 10.8±4 | 19±1.4 | 11.9±3.2 | <0.01 (group 2 vs 1,4) |

| CI (L/min/m2) | 2.82±0.78 | 2.67±0.62 | 2.60±0.7 | ns |

| PVR (WU) | 5.7±3 | 4.3±1.9 | 8.5±2.4 | ≤ 0.038 (group 4 vs 1,2) |

| PAC (ml/mmHg) | 1.78±0.68 | 2.31±2.36 | 1.09±0.39 | 0.023 (group 2 vs 4) |

| SVO2 (%) | 68.3±5.9 | 66.4±6.1 | 52.5±10 | ≤ 0.01(group 4 vs 1,2) |

| Specific PH treatment n=23/28(82.1) | ERA 15(65.2) | PDE5 6(26) | RIO 8(34.5) | SELEX 1(4.3) | Monotherapy 16(69.5) | Double therapy 7(30.4) | No specific PH treatment 5(17.9) |

| Precapillary PH n=11/12 | 9(75) | 3(25) | 1(8.3) | 0 | 9(75) | 2(16.7) | 1(8.3) |

| Postcapillary PH n=3/7 | 1(14.3) | 1(14.3) | 2(28.6) | 0 | 2(28.6) | 1(14.3) | 4(57.1) |

| CTEPH n=9/9 | 5(55.6) | 2(22.2) | 5(55.6) | 1(11.1) | 5(55.6) | 4(44.4) | 0 |

| N=9 | Baseline | Post treatment | p-value |

| RAP (mmHg) | 8.1±4.6 | 7.6±2.8 | 0.807 |

| PASP (mmHg) | 62.6±10.1 | 51±9.6 | 0.019 |

| mPAP (mmHg) | 38.8±6.8 | 33±6.5 | 0.083 |

| CI (L/min/m2) | 2.92±0.87 | 3.49±0.91 | 0.145 |

| PVR (WU) | 6.4±3.2 | 4±1.9 | 0.005 |

| PAC (ml/mmHg) | 1.58±0.55 | 2.75±1.67 | 0.044 |

| SVO2 (%) | 67.5±6 | 71.4±6.5 | 0.094 |

| Baseline | Last RHC | p-value | |

| RAP (mmHg) | 14.2±3.3 | 9.4±2 | 0.026 |

| PASP (mmHg) | 56.8±18.9 | 55±11 | 0.841 |

| mPAP (mmHg) | 38±10.1 | 34.6±5.5 | 0.482 |

| CI (L/min/m2) | 2.85±0.64 | 2.76±0.75 | 0.821 |

| PVR (WU) | 4.1±2.3 | 4.2±1.5 | 0.983 |

| PAC (ml/mmHg) | 2.71±2.77 | 2.01±0.78 | 0.594 |

| SVO2 (%) | 69.8±1.2 | 66.1±4.3 | 0.159 |

| N=6 | Baseline | Post treatment | p-value |

| RAP (mmHg) | 11.5±5.3 | 7.1±1.4 | 0.149 |

| PASP (mmHg) | 85.2±7.4 | 56.3±21 | 0.02 |

| mPAP (mmHg) | 51.7±6.1 | 34±10.2 | 0.029 |

| CI (L/min) | 2.33±0.35 | 2.79±0.42 | 0.063 |

| PVR (WU) | 9.5±1.6 | 4.5±2.9 | 0.020 |

| PAC (ml/mmHg) | 0.94±0.18 | 2.51±2 | 0.122 |

| SVO2 (%) | 51.6±10.9 | 61.1±8.4 | 0.138 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).