Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study species

2.2 Sources of seed and soils

2.3 Seed germination on sterile media

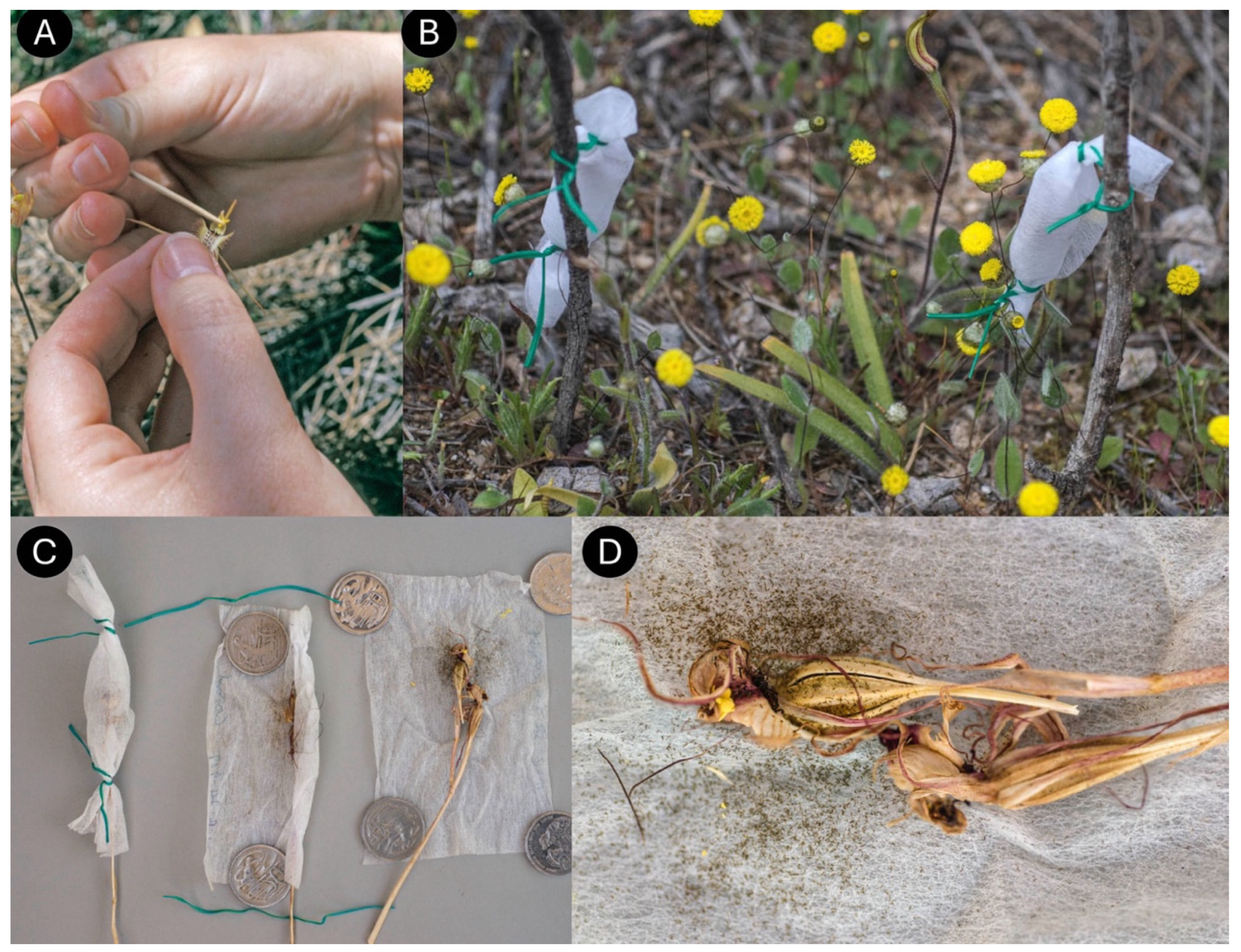

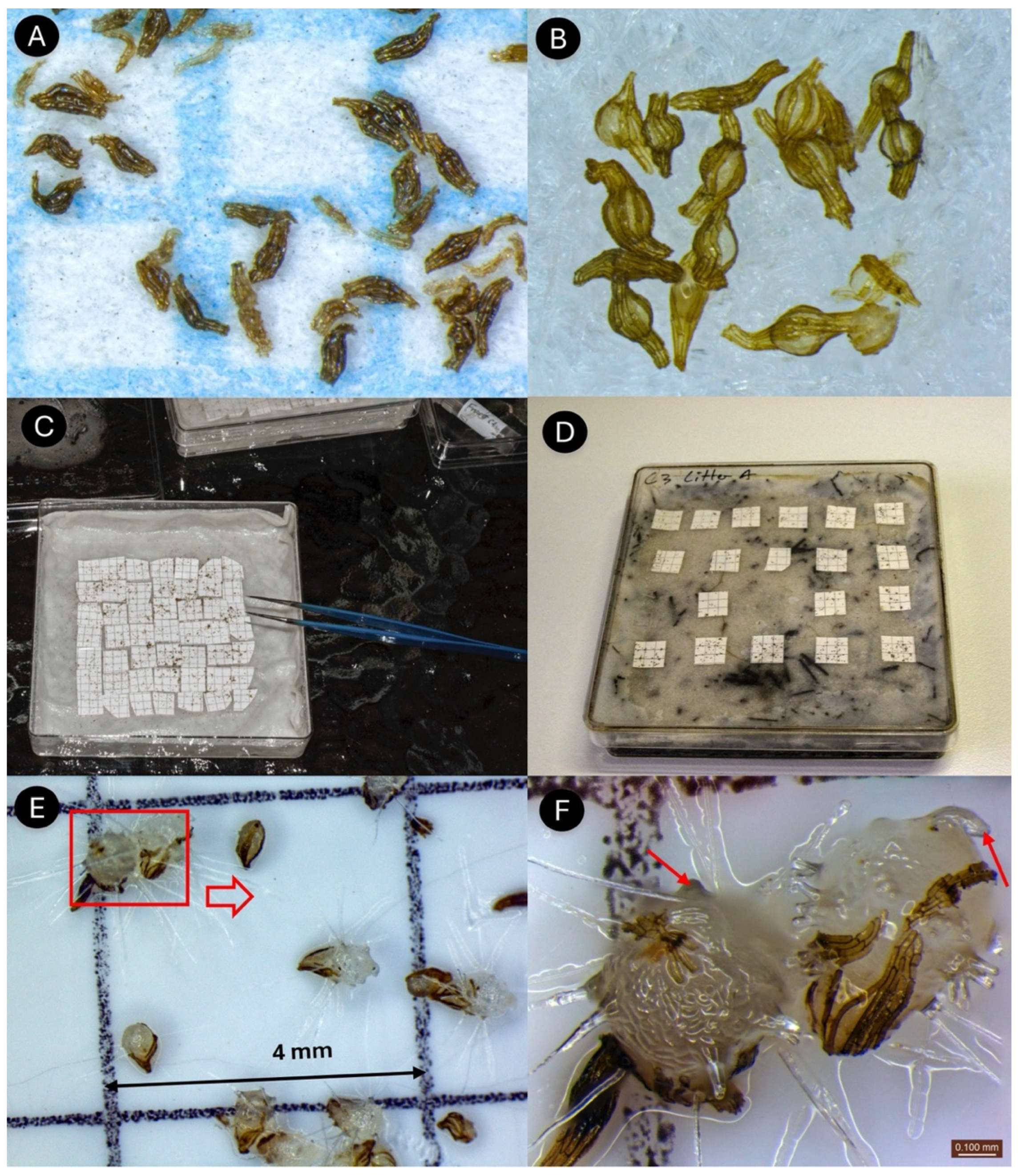

2.4 Orchid seed baiting

2.5 Seed germination in non-sterile conditions

2.6 Continued growth and translocation of seedlings

2.7 Measurements and data analysis

3. Results

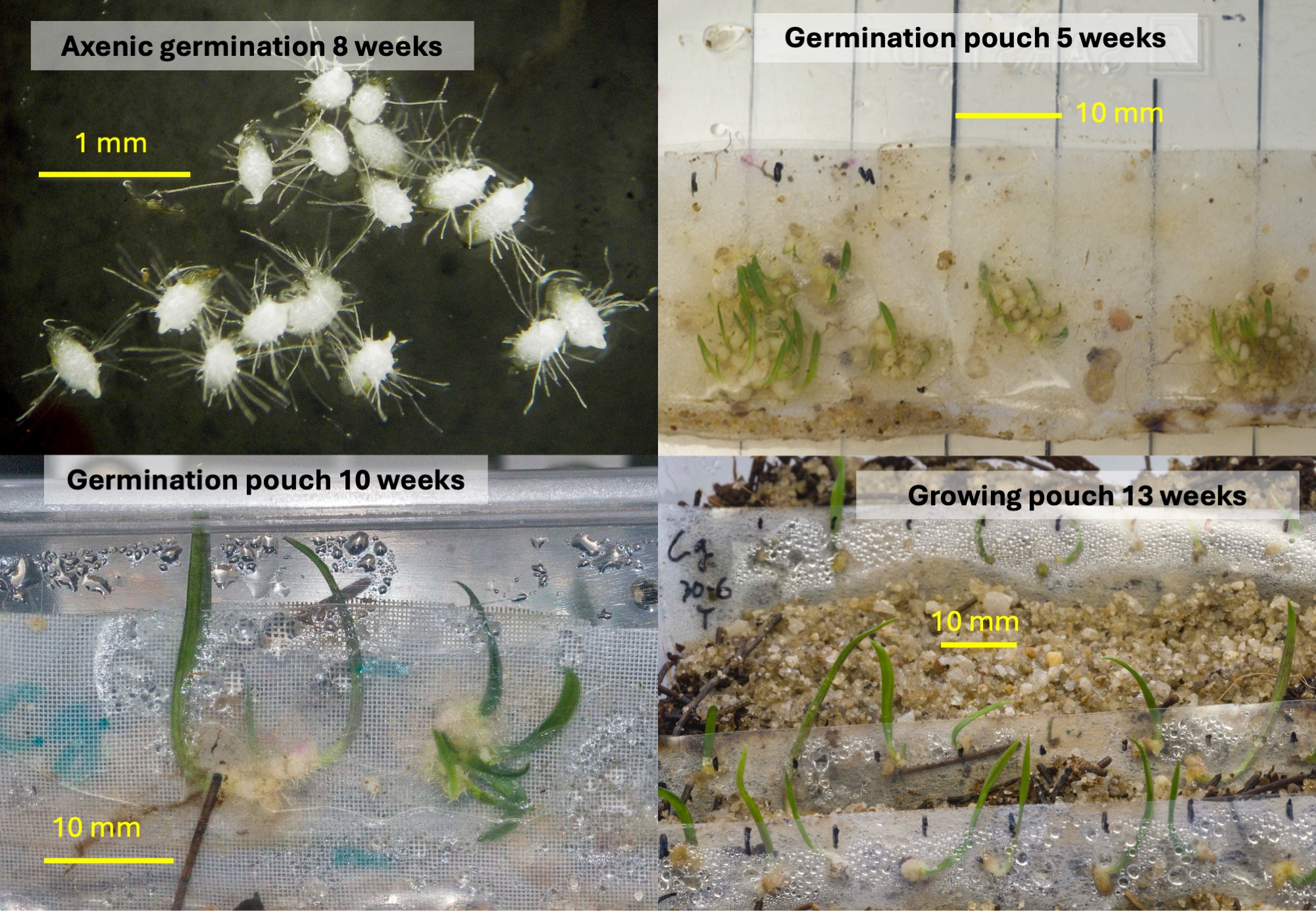

3.1 Asymbiotic sterile germination

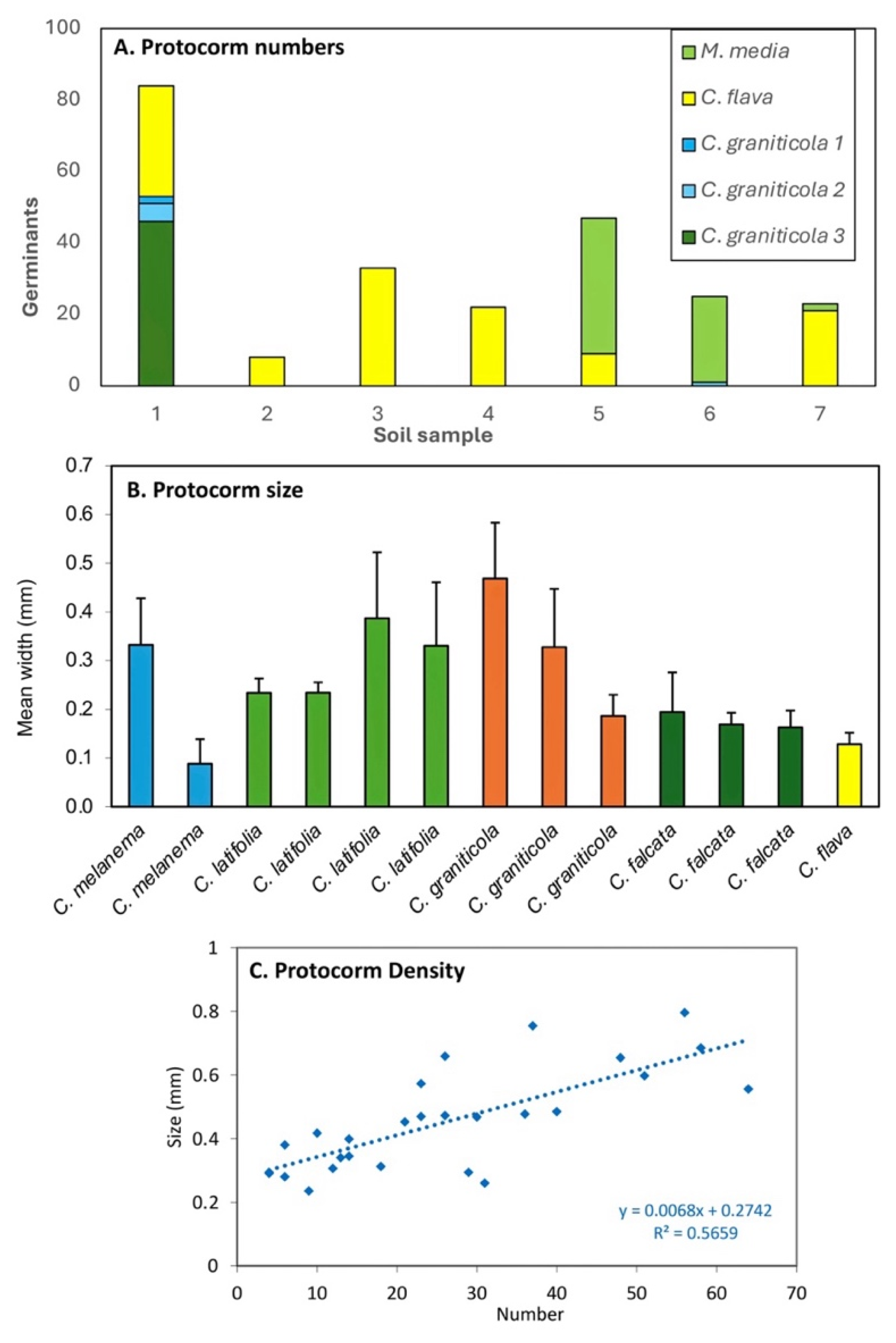

3.2 Ex situ baiting

3.3 Symbiotic germination in non-sterile conditions

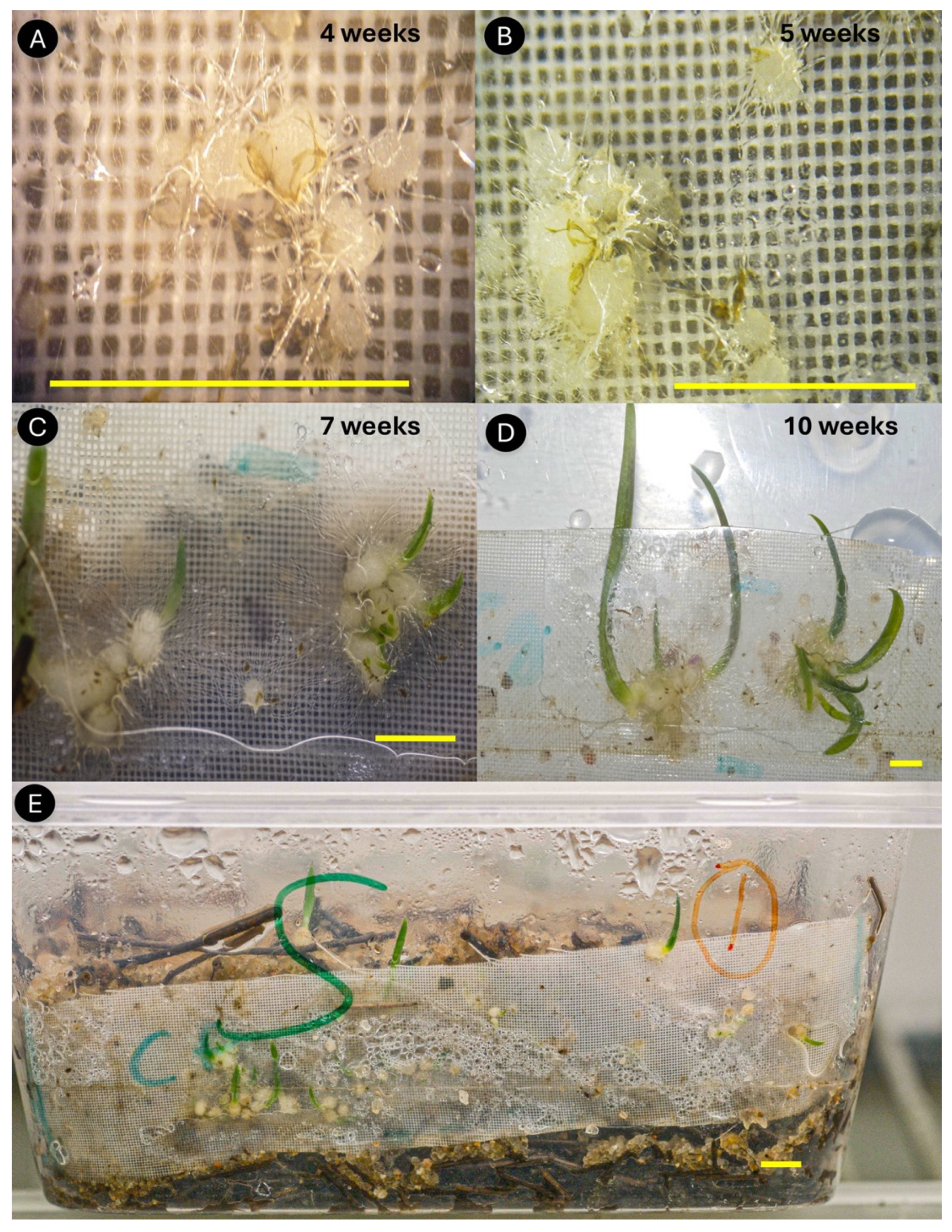

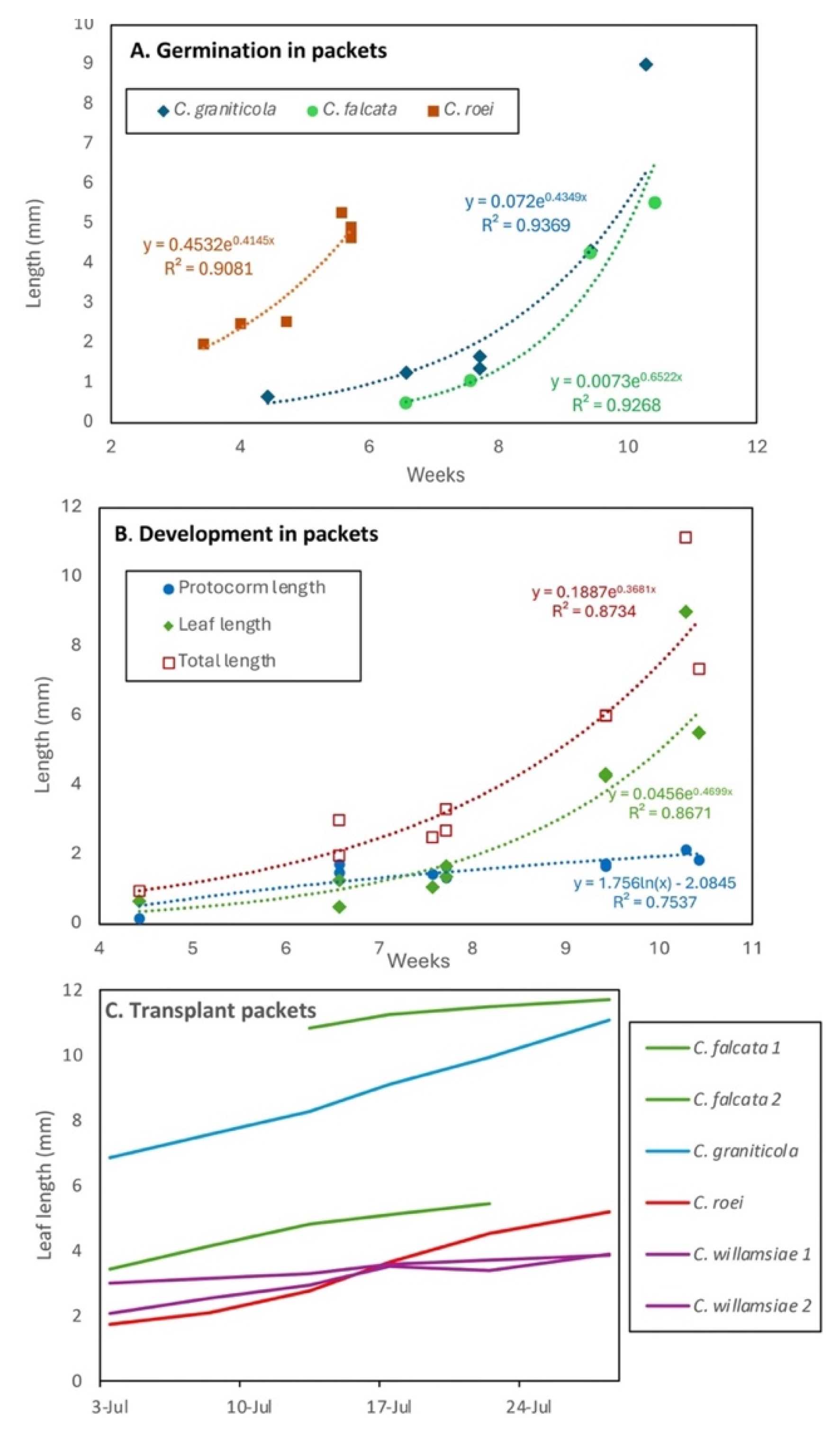

3.4 Seedlings in the incubator

3.5 Seedlings in the glasshouse or field

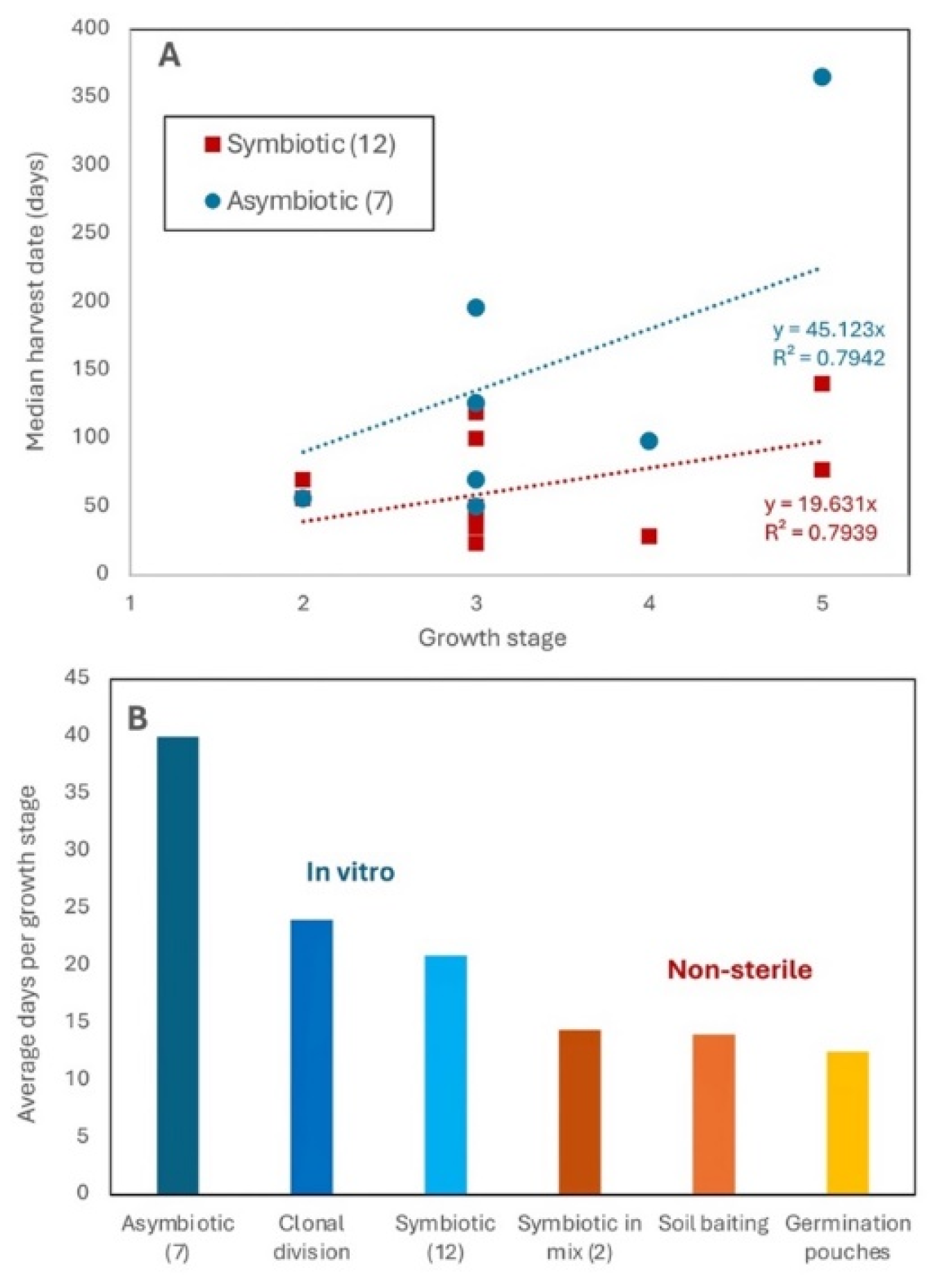

3.6 Comparison of methods

4. Discussion

4.1 In vitro seed germination

4.2 Non-sterile seed germination

4.3 Germination and development of orchids in semi-natural conditions

5. Conclusions

- 1.

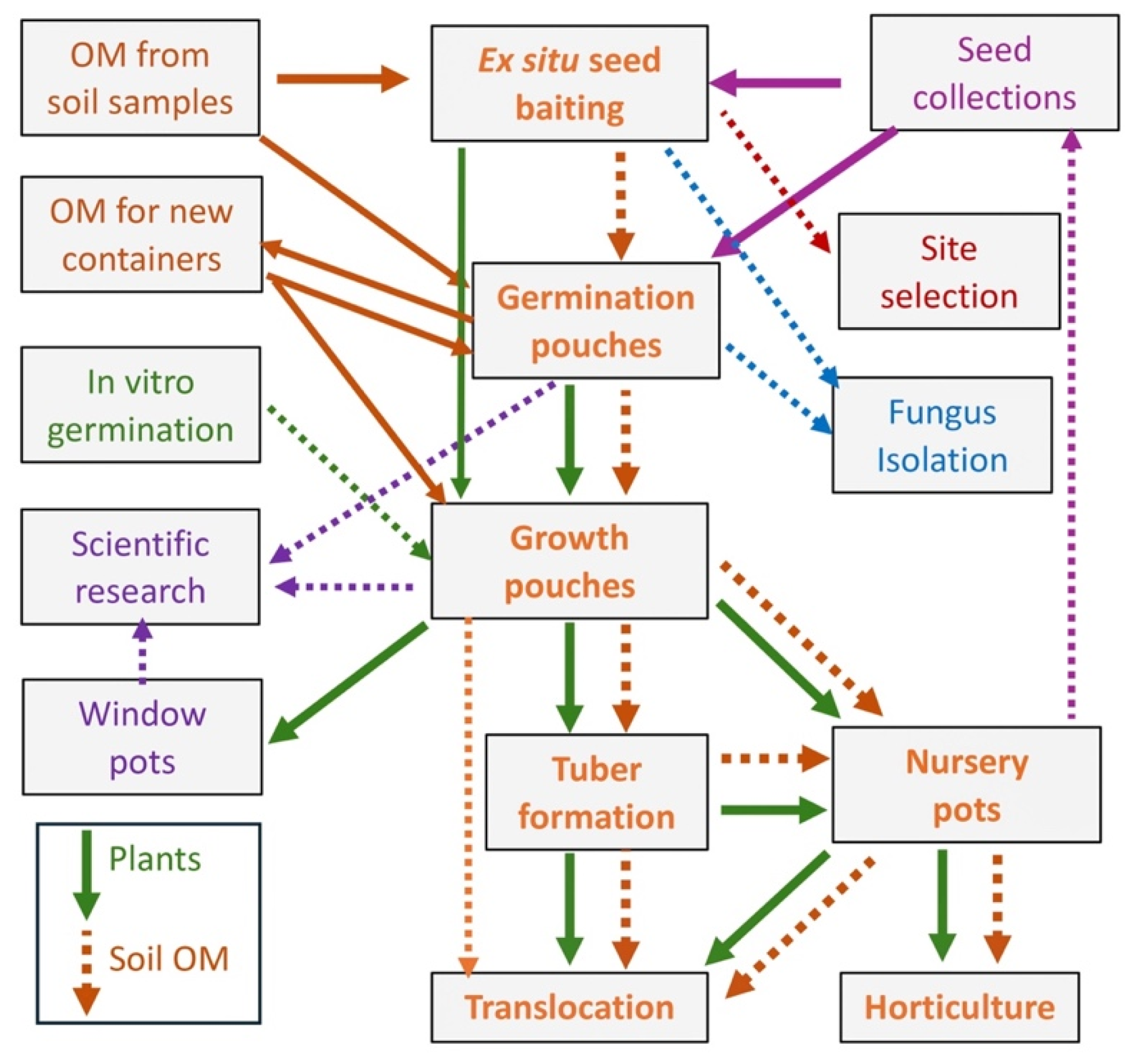

- Ex situ orchid seed baiting is normally used to determine if inoculum of compatible fungi is present in soils, but also measures seed viability (by counting imbibed seeds with coats ruptured by embryo enlargement). This method efficiently detected soil samples and fractions that contained fungus inoculum compatible with specific orchids, usually on the first attempt.

- 2.

- Non-sterile orchid seed germination utilising fungi present in soil organic material was a comparatively efficient and rapid method for orchid propagation (FORGE). The equipment and supplies required are readily available, inexpensive and containers can be reused many times. This method avoids the need for complex and expensive laboratory equipment and associated training.

- 3.

- The pouch system allows transplantation of seedlings along with substrate colonised by fungi into new containers at an optimum stage for further growth so rapid growth continues (Figures 5, 6). It is also possible to leave smaller protocorms for further growth. We were also transferred protocorms from in vitro culture or soil baiting into pouches, but these were less robust (Figure 5).

- 4.

- Regular observation of seeding growth allows intervention when growth slows, or pests appear (e.g. fungus gnats, nematodes, or slime moulds). Action can then be taken to address these issues (e.g. changing growing conditions, relocating seedlings, or application of control agents).

- 5.

- Orchid germination and growth in the FORGE system follows a normal sequence of development, in contrast to in vitro systems where seedlings tend to be abnormal. Developmental stages that are normally invisible in the soil can be studied under relatively natural conditions and easily photographed in plastic pouches without disturbance using inexpensive portable microscopes, phones or cameras. Transplanting seedings into window pots (Figure 6) allows observations to continue. Continuous observation of seedling development is also ideal for research on their development or physiology.

- 6.

- The use of natural inoculum sources containing indigenous fungi from orchid habitats should result in more robust seedlings for translocation and avoids introduction of non-local fungi.

- 7.

- 8.

- Large seedlings were available for translocation much sooner than in other propagation systems (the same year). Seedlings also survive better and grow more rapidly than those from in vitro methods, presumably because they were pre-adjusted to soil conditions.

- 9.

- Management of seedlings in FORGE microcosms requires inspections several times a week and occasional additions of small amounts of water.

- 10.

- Maintaining suitable temperature and substrate moisture is important to avoid over-abundance of harmful soil animals, slime moulds, etc.

- 11.

- Predators of orchid seeds and fungi may be present, so must be monitored and controlled (e.g. fungus gnats, nematodes, slime moulds, etc.). Mites are present, but have limited impacts, unlike sterile culture systems where they are a major source of contamination. Larger soil animals such as snails and millipedes can be manually removed.

- 12.

- Organic substrates supporting orchid growth eventually become depleted, collapsed or soggy, but can be augmented, or seedlings transplanted into a mixture of new and old substrate.

- 13.

- Living soil systems should be isolated from sterile culture facilities to avoid spread of harmful soil organisms.

- 14.

- The FORGE system is relatively new and requires further optimisation to increase consistency and efficiency for a wider diversity of orchid genera. Additional research is required to test substrates, growing conditions, plant density, possible nutrient supplements, management of soil animals, fungal diversity and the role of plant genetics in germination responses. However, this optimisation is unlikely to be more arduous than what is required for successful outcomes from sterile culture methods, which produce seedlings that must also survive in non-sterile environments after explanting.

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vitt, P.; Taylor, A.; Rakosy, D.; Kreft, H.; Meyer, A.; Weigelt, P.; Knight, T.M. Global conservation prioritization for the Orchidaceae. Scientific reports 2023, 13, 6718.

- Freudenstein, J.V. Orchid phylogenetics and evolution: history, current status and prospects. Annals of Botany 2024, mcae202.

- Givnish, T.J.; Zuluaga, A.; Marques, I.; Lam, V.K.; Gomez, M.S.; Iles, W.J.; Ames, M.; Spalink, D.; Moeller, J.R.; Briggs, B.G. Phylogenomics and historical biogeography of the monocot order Liliales: out of Australia and through Antarctica. Cladistics 2016, 32, 581–605.

- Rasmussen, H.N.; Rasmussen, F.N. Orchid mycorrhiza: Implications of a mycophagous life style. Oikos 2009, 118, 334–345. [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.; Cross, R.; Cousens, R.; May, T.; McLean, C. Taxonomic and functional characterisation of fungi from the Sebacina vermifera complex from common and rare orchids in the genus Caladenia. Mycorrhiza 2010, 20, 375,390.

- Oktalira, F.T.; Whitehead, M.R.; Linde, C.C. Mycorrhizal specificity in widespread and narrow-range distributed Caladenia orchid species. Fungal Ecology 2019, 42, 100869.

- Arditti, J.; Ghani, A.K.A. Numerical and physical properties of orchid seeds and their biological implications. The New Phytologist 2000, 145, 367–421.

- Brundrett, M.C. Scientific approaches to Australian temperate terrestrial orchid conservation. Australian Journal of Botany 2007, 55, 293–307. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R.D.; Brown, A.P.; Dixon, K.W.; Hopper, S.D. Orchid biogeography and factors associated with rarity in a biodiversity hotspot, the southwest Australian floristic region. Journal of Biogeography 2011, 38, 487–501.

- Gale, S.W.; Fischer, G.A.; Cribb, P.J.; Fay, M.F. Orchid conservation: bridging the gap between science and practice. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 2018, 186, 425–434.

- Wraith, J.; Pickering, C. A continental scale analysis of threats to orchids. Biological conservation 2019, 234, 7–17.

- Wraith, J.; Pickering, C. Tourism and recreation a global threat to orchids. Biodiversity and Conservation 2017, 26, 3407–3420.

- Dillon, R.; Monks, L.; Coates, D. Establishment success and persistence of threatened plant translocations in south west Western Australia: An experimental approach. Australian Journal of Botany 2018, 66, 338–346.

- Zimmer, H.C.; Auld, T.D.; Cuneo, P.; Offord, C.A.; Commander, L.E. Conservation translocation–an increasingly viable option for managing threatened plant species. Australian Journal of Botany 2020, 67, 501–509.

- Dowling, N.; Jusaitis, M. Asymbiotic in vitro germination and seed quality assessment of australian terrestrial orchids. Australian Journal of Botany 2012, 60, 592–601.

- Bustam, B.M.; Dixon, K.W.; Bunn, E. In vitro propagation of temperate australian terrestrial orchids: Revisiting Asymbiotic Compared with Symbiotic Germination. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 2014, 176, 556–566.

- Jolman, D.; Batalla, M.I.; Hungerford, A.; Norwood, P.; Tait, N.; Wallace, L.E. The challenges of growing orchids from seeds for conservation: An assessment of asymbiotic techniques. Appl Plant Sci 2022, 10, e11496. [CrossRef]

- Knudson, L. Nonsymbiotic germination of orchid seeds. Botanical Gazette 1922, 73, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Arditti, J. Micropropagation of Orchids; John Wiley & Sons: Malden, MA, USA, 2009;

- Huynh, T.T.; Thomson, R.; Mclean, C.B.; Lawrie, A.C. Functional and genetic diversity of mycorrhizal fungi from single plants of Caladenia formosa (Orchidaceae). Annals of Botany 2009, 104, 757–765.

- Freestone, M.; Linde, C.; Swarts, N.; Reiter, N. Asymbiotic germination of Prasophyllum (Orchidaceae) requires low mineral concentration. Australian Journal of Botany 2023, 71, 67–78.

- Hadley, G. Cellulose as a carbon source for orchid mycorrhiza. New Phytologist 1969, 68, 933–939. [CrossRef]

- Warcup, J.H. Symbiotic Germination of Some Australian Terrestrial Orchids. New Phytologist 1973, 72, 387–392.

- Clements, M.A.; Muir, H.; Cribb, P.J. A preliminary report on the symbiotic germination of European terrestrial orchids. Kew Bulletin 1986, 437–445.

- Zettler, L.W.; Piskin, K.A. Mycorrhizal fungi from protocorms, seedlings and mature plants of the eastern prairie fringed orchid, Platanthera leucophaea (Nutt.) Lindley: a comprehensive list to augment conservation. The American Midland Naturalist 2011, 166, 29–39.

- Reiter, N.; Whitfield, J.; Pollard, G.; Bedggood, W.; Argall, M.; Dixon, K.; Davis, B.; Swarts, N. Orchid re-introductions: an evaluation of success and ecological considerations using key comparative studies from Australia. Plant ecology 2016, 217, 81–95.

- Reiter, N.; Lawrie, A.C.; Linde, C.C. Matching symbiotic associations of an endangered orchid to habitat to improve conservation outcomes. Annals of Botany 2018, 122, 947–959.

- Batty, A.L.; Brundrett, M.C.; Dixon, K.W.; Sivasithamparam, K. New methods to improve symbiotic propagation of temperate terrestrial orchid seedlings from axenic culture to soil. Australian Journal of Botany 2006, 54, 367–374.

- Johnson, T.R.; Stewart, S.L.; Dutra, D.; Kane, M.E.; Richardson, L. Asymbiotic and symbiotic seed germination of Eulophia alta (Orchidaceae)—preliminary evidence for the symbiotic culture advantage. Plant cell, Tissue and organ culture 2007, 90, 313–323.

- Jamja, T.; Bora, S.; Tabing, R.; Tagi, N.; Chaurasiya, A.K.; Devi, N.; Yangfo, M. Symbiotic germination in orchids: an overview of ex situ and in situ symbiotic seed germination. Ecology Environment and Conservation 2023, 29, 1251–1265.

- Sommerville, K.D.; Siemon, J.P.; Wood, C.B.; Offord, C.A. Simultaneous encapsulation of seed and mycorrhizal fungi for long-term storage and propagation of terrestrial orchids. Australian Journal of Botany 2008, 56, 609–615.

- Yang, H.; Li, N.-Q.; Gao, J.-Y. A novel method to produce massive seedlings via symbiotic seed germination in orchids. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1114105.

- Wright, M.; French, G.; Cross, R.; Cousens, R.; Andrusiak, S.; McLean, C.B. Site amelioration for direct seeding of Caladenia tentaculata improves seedling recruitment and survival in natural habitat. Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology 2007, 7, 430–432.

- De Hert, K.; Jacquemyn, H.; Provoost, S.; Honnay, O. Absence of recruitment limitation in restored dune slacks suggests that manual seed introduction can be a successful practice for restoring orchid populations. Restoration ecology 2013, 21, 159–162.

- Brundrett, M.; Scade, A.; Batty, A.; Dixon, K.; Sivasithamparam, K. Development of in situ and ex situ seed baiting techniques to detect mycorrhizal fungi from terrestrial orchid habitats. Mycological Research 2003, 107, 1210–1220. [CrossRef]

- Whigham, D.F.; O’Neill, J.P.; Rasmussen, H.N.; Caldwell, B.A.; McCormick, M.K. Seed longevity in terrestrial orchids–potential for persistent in situ seed banks. Biological conservation 2006, 129, 24–30.

- Batty, A.L.; Dixon, K.W.; Sivasithamparam, K. Soil seed-bank dynamics of terrestrial orchids. Lindleyana 2000, 15, 227–236.

- Zhao, D.-K.; Selosse, M.-A.; Wu, L.; Luo, Y.; Shao, S.-C.; Ruan, Y.-L. Orchid reintroduction based on seed germination-promoting mycorrhizal fungi derived from protocorms or seedlings. Frontiers in plant science 2021, 12, 701152.

- Brundrett, M.C. A Proposed framework for efficient and cost-effective terrestrial orchid conservation. www.preprints.org 2020, doi:doi:10.20944/preprints202004.0465.v1.

- Benzing, D.H. Vascular epiphytism: Taxonomic participation and adaptive diversity. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 1987, 74, 183–204.

- Janissen, B.; French, G.; Selby-Pham, J.; Lawrie, A.C.; Huynh, T. differences in emergence and flowering in wild, re-introduced and translocated populations of an endangered terrestrial orchid and the influences of climate and orchid mycorrhizal abundance. Australian Journal of Botany 2021, 69, 9–20.

- Reiter, N.; Menz, M.H. Optimising conservation translocations of threatened Caladenia (orchidaceae) by identifying adult microsite and germination niche. Australian Journal of Botany 2022, 70, 231–247.

- Collins, M.T.; Dixon, K.W. Micropropagation of an Australian terrestrial orchid Diuris longifolia R. Br. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture 1992, 32, 131–135.

- Zettler, L.W.; McInnis, J. symbiotic seed germination and development of Spiranthes cernua and Goodyera pubescens (Orchidaceae: Spiranthoideae). Lindleyana, 1993, 8, 155-162.

- Oddie, R.L.A.; Dixon, K.W.; McComb, J.A. influence of substrate on asymbiotic and symbiotic in vitro germination and seedling growth of two Australian terrestrial orchids. Lindleyana 1994, 9, 183–189.

- Quay, L.; McComb, J.A.; Dixon, K.W. Methods for ex vitro germination of Australian terrestrial orchids. HortScience 1995, 30, 1445–1446.

- Batty, A.L.; Dixon, K.W.; Brundrett, M.; Sivasithamparam, K. Constraints to symbiotic germination of terrestrial orchid seed in a mediterranean bushland. New Phytologist 2001, 152, 511–520.

- Yamato, M.; Iwase, K. Introduction of Asymbiotically Propagated Seedlings of Cephalanthera falcata (Orchidaceae) into natural habitat and investigation of colonized mycorrhizal fungi. Ecological Research 2008, 23, 329–337. [CrossRef]

- Chou, L.-C.; Chang, D.C.-N. Asymbiotic and symbiotic seed germination of Anoectochilus formosanus and Haemaria discolor and their F1 Hybrids. Botanical Bulletin of Academia Sinica 2004, 45, 143–147.

- Batty, A.L.; Dixon, K.W.; Brundrett, M.; Sivasithamparam, K. Long-term storage of mycorrhizal fungi and seed as a tool for the conservation of endangered Western Australian terrestrial orchids. Australian Journal of Botany 2001, 49, 619–628.

- Swarts, N.D.; Sinclair, E.A.; Francis, A.; Dixon, K.W. Ecological specialization in mycorrhizal symbiosis leads to rarity in an endangered orchid. Molecular Ecology 2010, 19, 3226–3242.

- Freestone, M.; Linde, C.; Swarts, N.; Reiter, N. Ceratobasidium orchid mycorrhizal fungi reveal intraspecific variation and interaction with different nutrient media in symbiotic germination of Prasophyllum (Orchidaceae). Symbiosis 2022, 87, 255–268. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R.D.; Faast, R.; Bower, C.C.; Brown, G.R.; Peakall, R. Implications of pollination by food and sexual deception for pollinator specificity, fruit set, population genetics and conservation of Caladenia (Orchidaceae). Australian Journal of Botany 2009, 57, 287–306;

- Brundrett, M.C.; Ladd, P.G.; Keighery, G.J. Pollination strategies are exceptionally complex in southwestern Australia—A globally significant ancient biodiversity hotspot. Australian Journal of Botany 2024, 72, 1–70. [CrossRef]

- Brundrett, M.C. Using vital statistics and core habitat maps to manage critically endangered orchids in the West Australian wheatbelt. Australian Journal of Botany 2016, 64, 51–64.

- Brundrett, M. Wheatbelt Orchid Rescue Project: Case Studies of Collaborative Orchid Conservation in Western Australia; University of Western Australia: Nedlands, Western Australia, 2011;

- Brundrett, M. Identification and Ecology of Southwest Australian Orchids; Western Australian Naturalists’ Club Inc.: Perth, Western Australia, 2014;

- Brundrett, M.; Sivasithamparam, K.; Ramsay, M.; Krauss, S.; Taylor, R.; Bunn, E.; Hicks, A.; Karim, N.; Debeljak, N.; Mursidawati, S.; et al. Orchid Conservation Techniques Manual; First International Orchid Conservation Congress: Kings Park, Western Australia, 2001;

- Brundrett, M.; Ager, E. Wheatbelt Orchid Rescue Project Final Report: Seed Collecting, Soil Baiting and Propagation of Orchids; The University of Western Australia: Nedlands WA, 2011;

- Rasmussen, H.; Johansen, B.; Andersen, T.F. Density-dependent interactions between seedlings of Dactylorhiza majalis (Orchidaceae) in symbiotic in vitro culture. Physiologia Plantarum 1989, 77, 473–478.

- Anderson, M.J. PERMANOVA+ for PRIMER: Guide to Software and Statistical Methods. PRIMER-E, Plymouth Marine Laboratory 2008, 214.

- Bonnardeaux, Y.; Brundrett, M.; Batty, A.; Dixon, K.; Koch, J.; Sivasithamparam, K. Diversity of mycorrhizal fungi of terrestrial orchids: compatibility webs, brief encounters, lasting relationships and alien invasions. Mycological research 2007, 111, 51–61.

- De Long, J.R.; Swarts, N.D.; Dixon, K.W.; Egerton-Warburton, L.M. Mycorrhizal preference promotes habitat invasion by a native Australian orchid: Microtis media. Annals of botany 2012, 111, 409–418.

- Hadley, G. Non-specificity of symbotic infection in orchid mycorrhiza. New Phytologist 1970, 69, 1015–1023. [CrossRef]

- Masuhara, G.; Katsuya, K. In situ and in vitro specificity between Rhizoctonia spp. and Spiranthes sinensis (Persoon) Ames, var. amoena (M. Bieberstein) Hara (Orchidaceae). New Phytologist 1994, 127, 711–718.

- Raleigh, R.E. Propagation and Biology of Arachnorchis (orchidaceae) and their mycorrhizal fungi. PhD Thesis, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (Australia), 2005.

- Scade, A.; Brundrett, M.; Batty, A.; Dixon, K.; Sivasithamparam, K. Survival of transplanted terrestrial orchid seedlings in urban bushland habitats with high or low weed cover. Australian Journal of Botany 2006, 54, 383–389. [CrossRef]

- Silcock, J.L.; Simmons, C.L.; Monks, L.; Dillon, R.; Reiter, N.; Jusaitis, M.; Vesk, P.A.; Byrne, M.; Coates, D.J. Threatened plant translocation in Australia: a review. Biological Conservation 2019, 236, 211–222.

- Wright, M.; Cross, R.; Dixon, K.; Huynh, T.; Lawrie, A.; Nesbitt, L.; Pritchard, A.; Swarts, N.; Thomson, R. Propagation and reintroduction of Caladenia. Australian Journal of Botany 2009, 57, 373–387.

- Dutra, D.; Johnson, T.R.; Kauth, P.J.; Stewart, S.L.; Kane, M.E.; Richardson, L. Asymbiotic seed germination, in vitro seedling development, and greenhouse acclimatization of the threatened terrestrial orchid Bletia purpurea. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture 2008, 94, 11–21.

- Zi, X.-M.; Sheng, C.-L.; Goodale, U.M.; Shao, S.-C.; Gao, J.-Y. In situ seed baiting to isolate germination-enhancing fungi for an epiphytic orchid, Dendrobium aphyllum (Orchidaceae). Mycorrhiza 2014, 24, 487–499.

- Cruz-Higareda, J.B.; Luna-Rosales, B.S.; Barba-Alvarez, A. A novel seed baiting technique for the epiphytic orchid Rhynchostele cervantesii, a means to acquire mycorrhizal fungi from protocorms. Lankesteriana 2015, 15, 67–76.

- Higaki, K.; Rammitsu, K.; Yamashita, Y.; Yukawa, T.; Ogura-Tsujita, Y. A method for facilitating the seed germination of a mycoheterotrophic orchid, Gastrodia pubilabiata, using decomposed leaf litter harboring a basidiomycete fungus, Mycena sp. Botanical studies 2017, 58, 1-7 (59).

- Yang, W.-K.; Li, T.-Q.; Wu, S.-M.; Finnegan, P.M.; Gao, J.-Y. Ex situ seed baiting to isolate germination-enhancing fungi for assisted colonization in Paphiopedilum spicerianum, a critically endangered orchid in China. Global Ecology and Conservation 2020, 23, e01147. [CrossRef]

- Batty, A.L.; Brundrett, M.C.; Dixon, K.W.; Sivasithamparam, K. In situ symbiotic seed germination and propagation of terrestrial orchid seedlings for establishment at field sites. Australian Journal of Botany 2006, 54, 375–381.

- Feuerherdt, L.; Petit, S.; Jusaitis, M. Distribution of mycorrhizal fungus associated with the endangered pink-lipped spider orchid (Arachnorchis (Syn. Caladenia) behrii) at Warren Conservation Park in South Australia. New Zealand Journal of Botany 2005, 43, 367–371.

- Diez, J.M. Hierarchical patterns of symbiotic orchid germination linked to adult proximity and environmental gradients. Journal of Ecology 2007, 95, 159–170.

- Jacquemyn, H.; Brys, R.; Lievens, B.; Wiegand, T. Spatial variation in below-ground seed germination and divergent mycorrhizal associations correlate with spatial segregation of three co-occurring orchid species. Journal of Ecology 2012, 100, 1328–1337.

- Reiter, N.; Dimon, R.; Arifin, A.; Linde, C. Culture age of Tulasnella Affects Symbiotic Germination of the Critically Endangered Wyong sun orchid Thelymitra adorata (Orchidaceae). Mycorrhiza 2023, 33, 409–424.

- Harzli, I.; Özdener Kömpe, Y. Impact of fungal symbionts of co-occurring orchids on the seed germination of Serapias orientalis and Spiranthes spiralis. Current Microbiology 2025, 82, 79.

- Shao, S.-C.; Burgess, K.S.; Cruse-Sanders, J.M.; Liu, Q.; Fan, X.-L.; Huang, H.; Gao, J.-Y. Using in situ symbiotic seed germination to restore over-collected medicinal orchids in southwest China. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017, 8, 888.

- Wang, X.-J.; Wu, Y.-H.; Ming, X.-J.; Wang, G.; Gao, J.-Y. Isolating ecological-specific fungi and creating fungus-seed bags for epiphytic orchid conservation. Global Ecology and Conservation 2021, 28, e01714.

- Aewsakul, N.; Maneesorn, D.; Serivichyaswat, P.; Taluengjit, A.; Nontachaiyapoom, S. Ex vitro symbiotic seed germination of Spathoglottis plicata blume on common orchid cultivation substrates. Scientia Horticulturae 2013, 160, 238–242.

- Yao, N.; Wang, T.; Cao, X. Epidendrum radicans fungal community during ex situ germination and isolation of germination-enhancing fungi. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1841.

- Schweiger, J.M.-I.; Bidartondo, M.I.; Gebauer, G. Stable isotope signatures of underground seedlings reveal the organic matter gained by adult orchids from mycorrhizal fungi. Functional ecology 2018, 32, 870–881.

- Mehra, S.; Morrison, P.D.; Coates, F.; Lawrie, A.C. Differences in carbon source utilisation by orchid mycorrhizal fungi from common and endangered species of Caladenia (Orchidaceae). Mycorrhiza 2017, 27, 95–108.

- Yeung, E.C.-T.; Lee, Y.-I. The orchid protocorm. In Orchid Propagation; Yeung, E.C.-T., Lee, Y.-I., Eds.; Springer Protocols Handbooks; Springer US: New York, NY, 2024; pp. 3–15 ISBN 978-1-0716-4030-2.

- Veyret, Y. Development of the embryo and the young seedling stages of orchids. In The orchids: scientific studies; Withner, C., L., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1974; pp. 223–265.

- Kauth, P.J.; Kane, M.E. In vitro ecology of Calopogon tuberosus var. tuberosus (Orchidaceae) seedlings from distant populations: implications for assessing ecotypic differentiation. The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 2009, 136, 433–444.

- Leroux, G.; Barabé, D.; Vieth, J. Morphogenesis of the protocorm of Cypripedium acaule (Orchidaceae). Plant Systematics and Evolution 1997, 205, 53–72.

- González-Orellana, N.; Salazar Mendoza, A.; Tremblay, R.L.; Ackerman, J.D. Host suitability for germination differs from that of later stages of development in a rare epiphytic orchid. Lankesteriana 2024, 24, 93–114.

| Method | Orchids | Time taken | Success criteria | Yield | Reference |

| Symbiotic | Dactylorhiza elata, Orchis spp. (European) | 39-161 days | Stage 3-4 | ND | [24] |

| Symbiotic | 7 Thelymitra, 2 Diuris, 2 Pterostylis | 24-65 days | Stage 3 | ND | [23] |

| Clonal division | Diuris magnifica (was D. longifolia) | 120 days | Stage 5 (roots) | 5-55% | [43] |

| Symbiotic | Spiranthes cenua, Goodyera pubescens (European) | 23 days | Stage 3 | 8-95% | [44] |

| Symbiotic | Elythranthera emarginata, Diuris magnifica | 17 weeks | Stage 3 (trichomes) | 0.3-42% | [45] |

| Asymbiotic | As above | 28 weeks | As above | 11-52% | [45] |

| Symbiotic | Caladenia latifolia, D. magnifica (inoculated sterile potting mix) | 10 weeks | Stage 4 (leaf) | 80-230 per 270 ml | [46] |

| Symbiotic | Caladenia arenicola, Diuris magnifica, Pterostylis sanguinea, Thelymitra crinita | 4-6 weeks | Stage 3 (trichomes) | 31-59% | [47] |

| Asymbiotic | Eulophia alta (African) | 18 weeks | Stage 3 (trichomes) | 20-88% | [29] |

| Symbiotic | As above | 6 weeks | Stage 3 | 44.3% | [29] |

| Asymbiotic | Cephalanthera falcata, Anoectochilus formosanus, Haemaria discolor (Asian) | 2-5 months | Stage 4-6 | 50-70% | [48] |

| Asymbiotic | A. formosanus, H. discolor (Asian) | 50 days | Stage 3 (trichomes) | 72-75% | [49] |

| Symbiotic | As above | 50 days | Stage 3 | 80-81% | [49] |

| Soil baiting | Disa bracteata, Microtis media, Pterostylis sp., Caladenia arenicola, Diuris sp., Caladenia latifolia | 4-8 weeks | Stage 2-4 | 2 - 27% | [35] |

| Symbiotic | Caladenia arenicola, Diuris magnifica, Thelymitra crinita | 10-12 weeks | Stage 3-4 (leaf size) | 35 -53 % | [28] |

| Symbiotic | Caladenia formosa | 4 weeks | Stage 3-4 (green leaf) | 4-21% | [20] |

| Symbiotic | Caladenia arenicola, Pterostylis sanguinea (seed and fungi in alginate beads) | 8 weeks | Stage 3-5 (leaf size) | 560-2300 / m2 | [50] |

| Symbiotic | Caladenia huegelii, C. discoidea, C. arenicola, C. flava, C. longicauda | 10 weeks | Stage 2 (trichomes) | 35-85% | [51] |

| Asymbiotic | Pterostylis nutans, Microtis arenaria,我Thelymitra pauciflora, Prasophyllum pruinosum | 10 weeks | Stage 3 -4 | 10-95% | [15] |

| Symbiotic | Caladenia latifolia | 8 weeks | Stage 2 | 95% | [16] |

| Asymbiotic | D. magnifica, Thelymitra benthamiana, Spiculaea ciliata, Cyanicula gemmata, Elythranthera brunonis, Ericksonella saccharata, Pheladenia deformis, Eriochilus dilatatus, Microtis media, C. huegelii | 8 weeks | As above | 60-95% | [16] |

| Symbiotic | Prasophyllum frenchii | 3 months | Stage 3 (leaf primordia) | 0-5% | [52] |

| Asymbiotic | Prasophyllum 18 spp. | 12 months | Stage 5 (leaf) | 0-93% | [21] |

| Caladenia species | Seed batches | Seed sites | Soils (sites) | Baiting plates | Axenic plates | Germ pouch | Grow pouch | Pots |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. graniticola | 22 | 4 | 20 (4) | 20 | 4 | 2 | 10 | 4 |

| C. melanema | 7 | 3 | 5 (2) | 6 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| C. williamsiae | 4 | 1 | 4 (1) | 5 | 4 | 6 | 6 | |

| C. roei | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 3 | |

| C. dimidia | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | |||

| C. latifolia | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| C. falcata | 1 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 3 | |

| C. flava | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1 | ||||

| C. radialis | 2 | 1 | 5 | 3 |

| Asymbiotic Sterile | Soil Baiting | Seed Packets | Incubator | Greenhouse | Field | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. williamsiae | 129 | 1 | 64 | 28 | 28 | |

| C. melanema | 94 | 42 | 13 | 42 | 20 | 20 |

| C. graniticola | 256 | 28 | 51 | 20 | 20 | |

| C. falcata | 9 | 155 | 157 | 25 | 50 | 10 |

| C. roei | 29 | 193 | 108 | 48 | 80 | 20 |

| C. latifolia | 96 | 93 | 5 | 10 | ||

| C. flava | 159 | 10 | 10 | |||

| Total | 357 | 899 | 311 | 333 | 218 | 108 |

| Factor | Asymbiotic | Soil Baiting | Seed Packets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preparation time (days) | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Set up time (days) | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Maintenance time (hrs./week) | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Multiplies fungi associates in soil | no | no | yes |

| Complexity of methods | high | medium | low |

| Loss due to contamination or similar | 50% | 15% | 10% |

| Typical growth rate (mm/week) | 0.04 | 0.04 | 1.4 |

| Yield (average size mm) | 0.46 | 0.38 | 7.5 |

| Yield (seedlings per container) | 19 | 66 | 54 |

| Time to produce seedlings (stage 3) | 2-6 months | 1-2 months | 1-2 months |

| Further growth required for outplanting | months | weeks | weeks (if needed) |

| Survival in greenhouse | low | medium | high |

| Cost per 100 seedlings in 2009 (Table S1) | $ 3.79 | $ 1.09 | $ 1.30 |

| Overall Ranking | * | ** | *** |

| Stage | Description | Morphology | Roles | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Seed | Small embryo in dry seed coat | Dispersal and quiescence | Waiting |

| 1 | Imbibed seed | Spherical swollen embryo, split seed coat (if viable and non-dormant) | Irreversible transition to growth or death due to water uptake | Pre-germination |

| 2 | Protocorm | Growth from cell division starts, leading to cell differentiation and trichome initiation (ovoid shape) | Attraction of fungi and potential initiation of symbiosis by fungal colonisation | Germination starts |

| 3 | Advanced protocorm | Substantial growth (change in shape - longer, broader, etc.), many long trichomes, fungal coils, leaf primordia (if relevant) | Establishment of functional mycorrhizas, resource acquisition, initiation of photosynthesis (if relevant) | Germination success – TF |

| 4 | Seedling | Substantial leaf growth (or stem, root, or rhizome), protocorm growth slows | Metabolic balance shifts towards autotrophy (if relevant), fuelling rapid growth | Growth – TF |

| 5 | Advanced seedling | Organ differentiation to form root, or dropper, or rhizome (varies with orchid) | Switch towards adult growth phase and resource storage | Consolidation我– TF, SN |

| 6 | Adult plant | Vegetative organs complete (tuber, corm, rhizome, stem - varies with orchid), plant dormancy or quiescence starts (if relevant) | Completion of structures required for successful perennation | Completion and survival – SN, SO |

| 7 | Reproductive plant | Flowering and seed set or clonal division (usually on a subsequent year) | Reproduction potentially leading to local persistence and spread | Establishment and expansion – SO |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).