1. Introduction

1. Transition metal oxides (TMOs), such as Nb

2O

5, are notable for their diverse oxidation states and advantageous electronic and optical properties, making them suitable for applications in energy storage and photocatalysis. Hereby, Nb

2O

5 is a stable wide-band gap

n-type semiconductor, whose properties strongly depend on the type of polymorph. Among these, monoclinic H-Nb

2O

5 is the thermodynamically stable variant and consists of a ReO

3 block-type structure of 3 × 5 and 3 × 4 blocks of corner sharing NbO

6 octahedra within the blocks and edge sharing between blocks [

1]. With a band gap ranging from 3.1 to 3.9 eV [

2,

3] and an electrical conductivity of 10

-13 - 10

-6 S cm

-1 [

4], Nb

2O

5 has been primarily explored for sensor applications and various electronic devices [

5,

6], with some studies also investigating its potential in dye-sensitized solar cells [

7] and photocatalytic processes [

8].

Upon partial reduction of TMOs and creation of oxygen vacancies, their electronic properties can be enhanced compared to the pristine oxides, yielding materials with improved chemical and physical characteristics [

9]. For instance, Chen

et al. synthesized so-called black titania through hydrogenation of TiO

2, which introduced defects and partially reduced Ti

4+ cations to Ti

3+, resulting in increased photocatalytic activity relative to the pristine oxide [

10]. This approach has spurred interest in defect engineering within TMOs, leading to reports on partially reduced oxides such as Nb

2O

5-x [

11,

12], ZrO

2–x [

13], WO

3–x [

14], V

2O

5–x [

15], and MoO

3–x [

16], which also exhibit enhanced light absorption [

13], as well as improved photocatalytic [

15] and photoelectrochemical (PEC) activities [

11,

12].

Despite the potential of black Nb

2O

5, its synthesis has not been extensively studied. Common synthesis methods involve high-temperature reductions using aluminum [

11,

12] or NaBH

4 [

17] as reducing agents or the creation of oxygen vacancies by the diffusion-reduction method [

18], resulting in the formation of high-performance materials for photoelectrochemical water-splitting, sodium-ion batteries, and photocatalytic CO

2 reduction, respectively. However, these methods often require energy-intensive annealing steps under inert gas [

19], hydrogen [

20,

21,

22], or vacuum [

23] conditions to induce partial reduction and formation of Nb

2O

5−x.

In contrast, mechanochemical approaches offer a more energy-efficient alternative by inducing chemical reactions through the absorption of mechanical energy at room temperature [

24]. While energy consumption is not only heavily reduced with this method, the continuous impact of milling balls also results in the creation of additional defects and an increase in reactivity. Literature on mechanochemical reduction of TMOs is limited, using either highly reactive alkaline metals, such as Na [

25] or Li [

26] or non-conventional hydrides such as TiH

2 [

27]. In a recent study, we were able to show that alkali metal hydrides LiH and NaH represent readily available and powerful reducing agents for the partial reduction in a ball mill of rutile type TiO

2 and monoclinic H-Nb

2O

5 resulting in the formation of black TiO

2 and black Nb

2O

5 with enhanced photocatalytic activities for the degradation of methylene blue [

28].

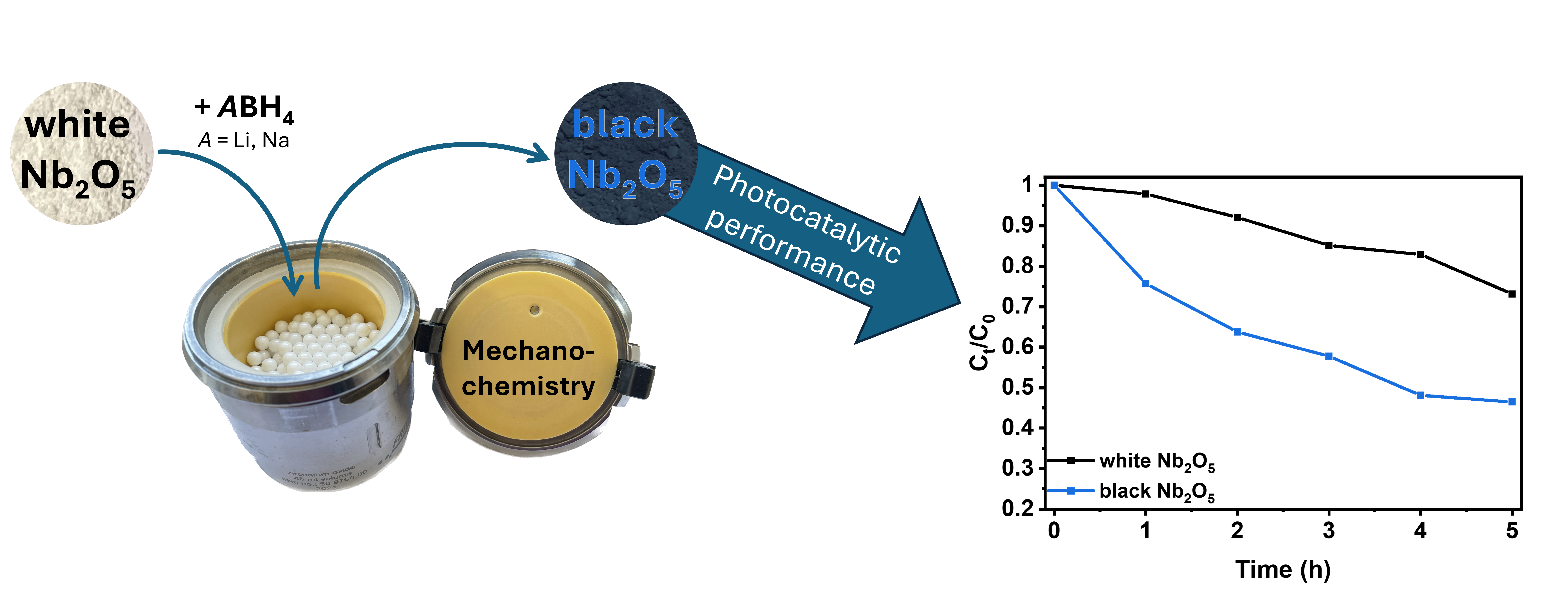

Building on this knowledge, we now systematically investigate the effectiveness of LiBH4 and NaBH4, which has already been used in high temperature reductions, as reducing agents in mechanochemical reduction processes. More specifically, the effects of concentration and milling duration on the resulting materials' photocatalytic activity for methylene blue degradation are examined.

2. Materials and Methods

Materials

Nb2O5 (ChemPur, Karlsruhe, Germany, 99.98%), NaBH4 (Merck, Hohenbrunn, Germany, ≥ 98%), and LiBH4 (Sigma Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany, ≥ 95%) were used without further purification and stored in a glovebox under argon atmosphere. 1,2-dimethoxyethane (ABCR GmBH, Karlsruhe, Germany, 99%) was dried in a solvent purifying system SPS 5 (MBRAUN, Garching, Germany). All solids have been characterized by X-ray diffraction before use.

Synthesis

The syntheses were performed in a planetary ball mill Pulverisette 7 (Fritsch, Idar-Oberstein, Germany) using ZrO2 grinding jars with a volume of 45 mL and 180 ZrO2 milling balls with a diameter of 5 mm. All syntheses were carried out under an argon atmosphere using glovebox technique. In a typical experiment, 3.00 g of Nb2O5 (11.29 mmol, 1 eq.) were milled with n eq. of ABH4 (n = 0.25, 0.5, 1 and 2; A= Li, Na). The milling speed was set to 300 rpm, while the milling time was equal to 10, 30, and 60 min. To prevent cementation during the milling process with 1 or 2 eq. of ABH4, 200 µL of dry 1,2-dimethoxyethane (DME) were added.

Afterwards, the samples were washed with water and MeOH several times to remove unreacted alkali metal hydrides as well as side products. Both solvents were degassed with argon for 1 h beforehand. After centrifugation, samples were dried in a vacuum oven at 80 °C and stored in an argon-filled glovebox.

Testing of the photocatalytic activity

The photocatalytic experiments were performed in an EvoluChemTM PhotoRedOx Box (HepatoChem, Beverly, USA) equipped with 2 x 20 ml sample holder, an EvoluChem 365PF lamp (365 nm) for testing the photocatalytic activity in the UV region and an Evoluchem 6200PF lamp (cold white) for the Vis region.

In a typical methylene blue (MB) degradation experiment, 15 mg of catalyst (1 mg/ml) were added to 15 mL of an aqueous MB solution (20 ppm). After stirring for 30 min in the dark, the suspensions were irradiated. After certain time intervals, 0.4 ml of suspension were periodically sampled and centrifuged to separate the photocatalyst from the solution. The MB solution was then diluted by a factor of 2 before the concentration of MB was measured by UV-Vis spectroscopy.

Characterization

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns were recorded on a D8-A25-Advance diffractometer (Bruker-AXS, Karlsruhe, Germany) under ambient conditions in BraggBrentano

θ-θ-geometry (goniometer radius 280 mm) with Cu

Kα-radiation (λ = 154.0596 pm). A 12 µm Ni foil served as a

Kβ filter at the primary beam side. At the primary beam side, a variable divergence slit was mounted and a LYNXEYE detector with 192 channels at the secondary beam side. Experiments were carried out in a 2

θ range of 7 to 120° with a step size of 0.013° and a total scan time of 2 h. Rietveld refinement of the recorded diffraction patterns was performed using TOPAS 5.0 software [

29]. Crystallographic structure and microstructure were refined, while instrumental line broadening was included in a fundamental parameters approach [

30]. The mean crystallite size <L> was calculated as the mean volume weighted column height derived from the integral breadth. Crystal structure data were obtained from the Pearson’s Crystal database [

31].

EPR spectra were recorded using an Elexsys E580 X-band spectrometer (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany) with an ER 4118X-MD5 resonator (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany). All shown EPR spectra were recorded at 80 K using a closed cycle cryostat (Cryogenic CF VTC).

For the acquisition of the Raman spectra, a Raman microscope LabRAM HR Evolution HORIBA Jobin Yvon A (Horiba, Longmujeau, France) with a 633 nm HeNe Laser (Melles Griot, IDEX Optics and Photonics, Albuquerque, USA) and an 1800 lines/mm grating was used.

UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectra were performed on a Perkin Elmer Lambda 750 spectrometer (PerkinElmer Inc., Shelton, USA) equipped with a 100 mm integration sphere from 290 to 1500 nm with a 2 nm increment and an integration time of 0.2 s. BaSO4 was used as the reference.

7Li and

11B single-pulse excitation magic angle spinning (SPE MAS) NMR spectra were recorded at 155.57 MHz and 128.43 MHz, respectively, on a Bruker AV400WB spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, USA) at 298 K in standard ZrO

2 rotors with a diameter of 4 mm. A spinning rate of 13 kHz and a relaxation delay of 3 s were applied. Solid LiCl and NaBH

4 were used as an external reference with a chemical shift of 0 and -42 ppm, respectively. Spectra were recorded using the TopSpin software [

32]. Fitting of the spectra was performed using the DMFit software program package [

33]. The extracted data is compiled in Table 1.

3. Results

3.1. Reduction Process During Ball Milling

For the mechanochemically induced partial reduction of Nb2O5, niobia was milled with n equivalents of LiBH4 and NaBH4 (n = 0.25, 0.5, 1 and 2 eq.) for 10, 30, and 60 min at a constant milling speed of 300 rpm. To prevent cementation and ensure a homogeneous reaction mixture, 200 µl DME were added during milling with 1 and 2 eq. of MBH4 for 60 min.

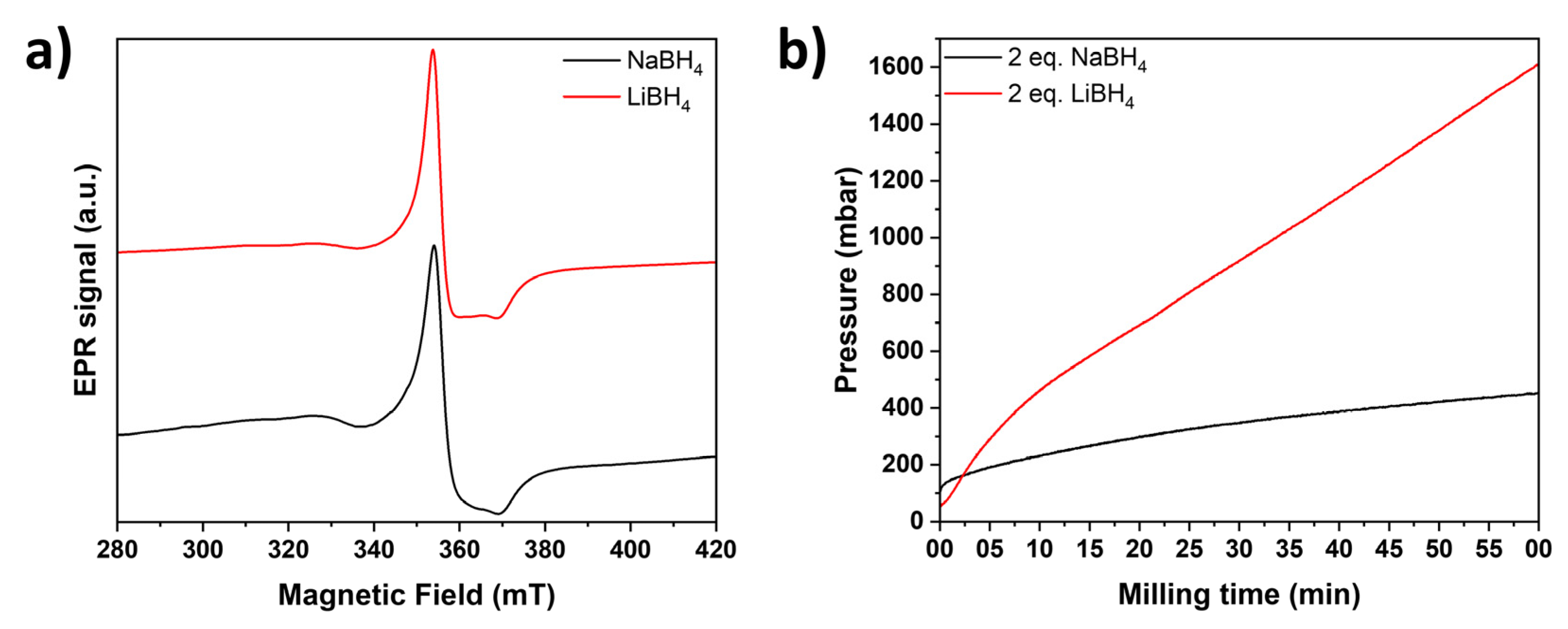

After just 10 minutes of mechanochemical treatment at room temperature, a color change from white Nb

2O

5 to light gray and dark blue-black is observed depending on the milling conditions (Supporting Information,

Figure S1). This change in color can be attributed to the reduction of Nb

5+ to Nb

4+ [34] accompanied by the intercalation of alkali metal ions and/or the presence of color centers [

35] due to the formation of oxygen vacancies [

36] to maintain electroneutrality. The formation of unpaired electrons, which confirms a successful reduction, [

12,

37] was proven by EPR spectroscopy even for the lighter colored NaBH

4 reduced samples (

Figure 1a). Hereby, LiBH

4 produced darker (anthracite to blackish blue) and more reduced samples than NaBH

4 (light gray to darker gray). To monitor the evolution of the pressure inside the milling jar, the EASY GTM system by Fritsch was used. As shown in

Figure 1b, a continuous pressure increase up to 0.4 and 1.6 bar is observed with NaBH

4 and LiBH

4, respectively, which was also observed due to hydrogen formation during the mechanochemical reduction of TiO

2 and Nb

2O

5 with NaH and LiH [

28]. In theory, the formation of volatile borane species as side-products is also conceivable, but not further investigated, as the focus lays on the characterization of the as-prepared reduced oxides. The higher pressure observed with LiBH

4 aligns with its greater efficiency in achieving reduction compared to NaBH

4. The milling process also elevated the temperature but remained below 35 °C for both hydrides.

Figure 1: (a) Normalized continuous wave (CW) EPR spectra of Nb2O5 reduced with 0.25 eq. NaBH4 (black) and 0.25 eq. LiBH4 (red) for 60 min. (b) Evolution of the pressure inside the milling jar for the reaction of Nb2O5 with 2 eq. NaBH4 (black) and LiBH4 (red).

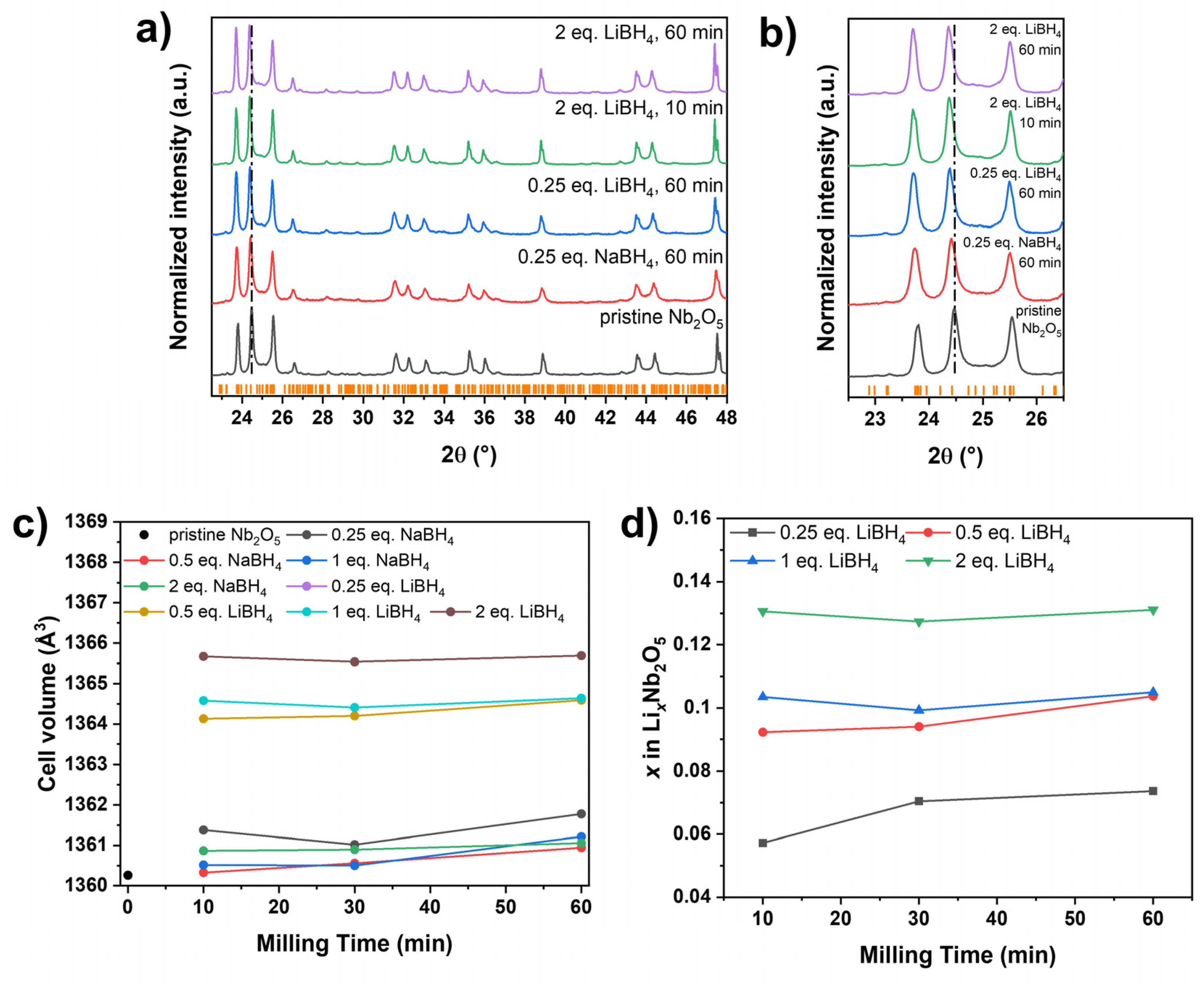

3.2. PXRD Analysis and Influence of the Hydride Concentration on the Reduction

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) analysis was conducted to assess structural modifications induced by partial reduction during milling. The diffraction patterns of all reduced samples remained consistent with monoclinic H-Nb₂O₅ (space group

P2/

m), indicating no major structural transformation, regardless of the reducing agent, its concentration, or the milling duration (Figure 2a; Supporting Information,

Figures S2–S8). However, a distinct shift toward lower diffraction angles was observed for all LiBH

4 reduced samples (

Figure 2b). Rietveld refinement revealed an expansion of the unit cell volume of by up to ~6·10

-3 nm

3 in these samples compared to pristine Nb

2O

5, whereas no significant increase was detected for NaBH

4 reduced samples (

Figure 2c). Generally, higher LiBH

4 concentrations resulted in increased cell volumes, while the milling time has a rather low influence. As previously reported for the mechanochemical reduction of transition metal oxides using LiH and NaH [

28], the observed volume increase is attributed to Li

+ intercalation, given its smaller ionic radius of (76 pm) compared to Na

+ (102 pm) [

38]. Based on the unit cell expansion, the estimated composition of the LiBH

4 reduced samples ranged from Li

0.06(1)Nb2O

5 to Li

0.13(1)Nb2O

5 (

Figure 2c). In contrast, previously reported LiH-reduced samples exhibited a broader composition range (Li

0.02(1)Nb2O

5 to Li

0.25(1)Nb2O

5) [

28], consistent with the higher reactivity of LiH compared to LiBH

4.

Figure 2: (a) PXRD patterns and (b) corresponding zoom of pristine and reduced niobia. Orange ticks indicate the Bragg positions of monoclinic Nb2O5 (P2/m). The vertical line is meant for easier visualization of the shift of reflections. (c) Evolution of the cell volume of pristine Nb2O5 compared to LiBH4 and NaBH4 reduced samples and (d) the estimated Li content based on Rietveld refinement assuming a sum formula of LixNb2O5 for the LiBH4 reduced samples.

Although the microstructure parameters crystallite size and strain cannot be refined simultaneously (Supporting Information,

Figure S9), an overall trend can be observed in the influence of the reaction parameters on the microstructure. With increasing milling times and decreasing hydride concentrations, the niobia crystallites exhibit larger defects, which are characterized by smaller crystallite size and/or larger strain. Longer milling times tend to damage the material due to the sustained mechanical stress. [

39,

40,

41] On the other hand, the decrease in damage with decreasing NaBH

4 and LiBH

4 suggests a mechanical buffering effect of the respective hydride, meaning that the boron hydrides can absorb some of the mechanical energy from collisions with the milling balls without decomposing. The transfer of mechanical energy is thus hindered, and less energy is available to induce the mechanochemical reduction, which also explains nicely the lighter coloration of samples prepared with high NaBH

4 concentrations. In this case, the excess of hydride has the opposite effect of an inert grinding auxiliary such as inorganic salts, which can for example be added to sticky reaction mixtures to achieve a better texture and efficient mixing [

42].

While clear differences in the sample coloration are observed in the NaBH4 reduced samples (the darker the samples are, the higher their degree of reduction), color differences in the LiBH4 reduced samples are more subtle. This raises the question of why NaBH4 reduced samples show larger differences in color. In fact, the higher molar mass of NaBH4 necessitates nearly doubles the mass compared to LiBH4 to achieve the same Nb2O5-to-hydride ratio; for instance, 0.8539 g of NaBH4 is required for a 1:2 ratio, while only 0.4920 g of LiBH4 is needed. Consequently, it is very likely that LiBH4 shows overall the same behavior, but it is less obvious due to the lower used mass. Theoretically, the use of an even greater excess of LiBH4 should therefore lead to a lower degree of reduction.

To test this hypothesis, Nb2O5 was milled with an excess of 5 eq. LiBH4 (similar weight ratio of the reactants than Nb2O5/2 eq. NaBH4) for 10 min at 300 rpm, with 200 µl of DME added to prevent cementation. The resulting light blue oxide was significantly lighter than the sample obtained with only 2 equivalents of LiBH4 under identical milling conditions. After washing and removal of unreacted LiBH4, a cell volume of 1364.46 Å3 was determined by Rietveld refinement. The lighter coloration and reduced cell volume suggest that a lower degree of reduction was achieved with the excess LiBH4. Consequently, the above hypothesis is confirmed and higher concentrations of the two alkali metal borohydrides tested lead to an overall lower reduction as the excess hydride acts as a buffer material.

3.3. Solid State NMR Spectroscopy

Solid state NMR spectroscopy was applied to study the effectiveness of the washing process, which is needed to remove unreacted hydrides and other possibly formed boron-containing side products such as alkali metal borates [

43,

44], which can also be envisioned in addition to the formation of volatile boron-containing side products. Moreover, the local environment of intercalated lithium can be investigated.

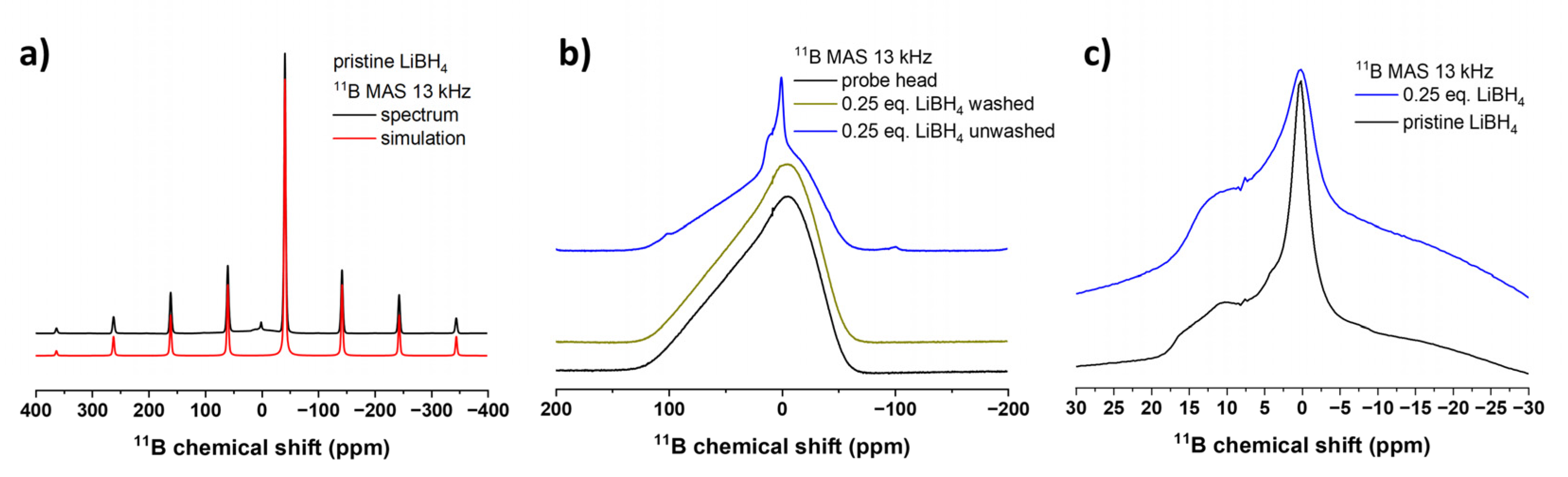

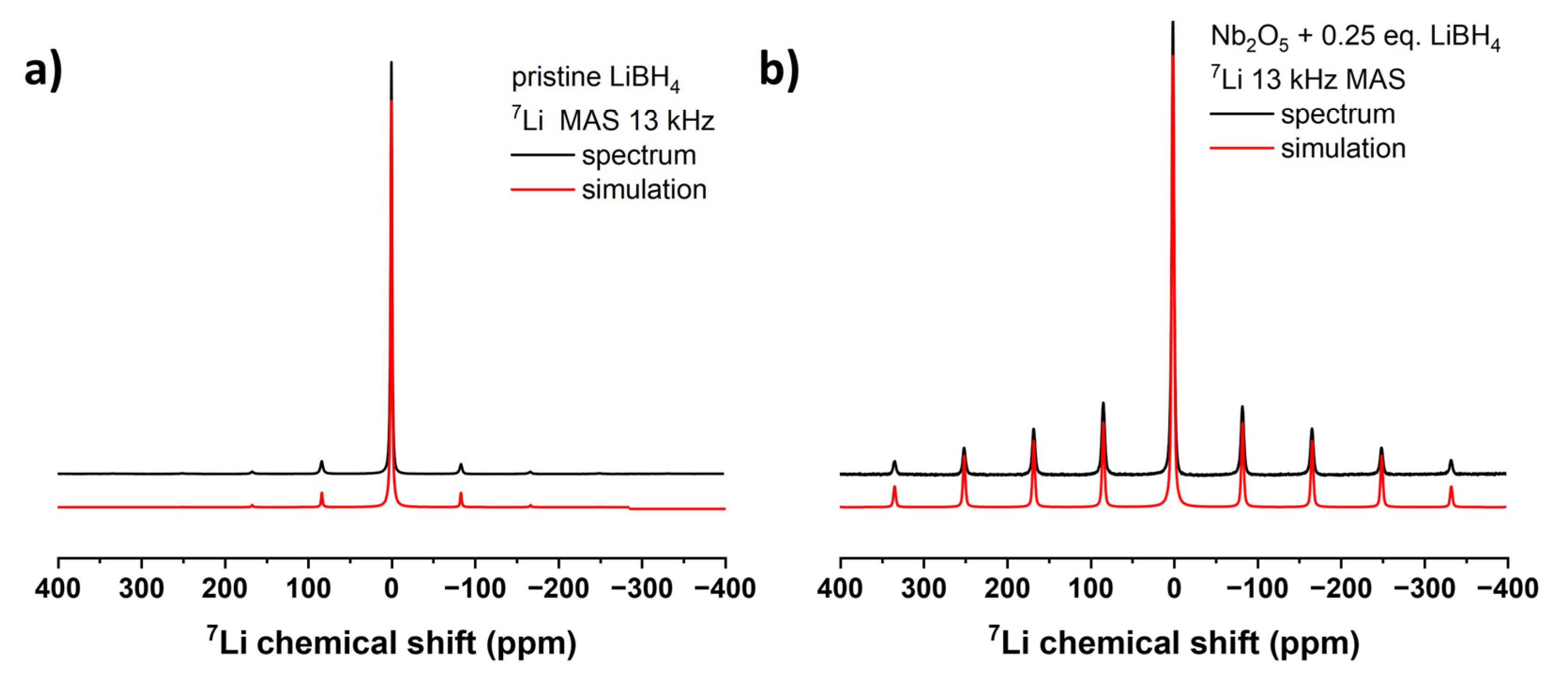

As shown in the

11B and

7Li solid state MAS NMR spectra of the pristine LiBH

4 starting material, an intense central |+1/2⟩↔|–1/2⟩ transition was observed at -42.0 and -0.7 ppm respectively, as well as a spinning sideband manifold originating from the outer satellite transitions |±1/2⟩↔|±3/2⟩ (

Figure 3a,

Figure 4a), which is consistent with the literature [

45,

46]. With the help of the DMFit software package [

33] for both spectra the quadrupolar parameter C

Q was extracted for the cases of η

Q = 0 and 1, which gives a hint on the local site asymmetry and coordination environment (Supporting Information,

Table S1). The

11B solid-state NMR spectra show the broad signal of the probe head, which contains a B-containing stator, so the signals can only be interpreted to a limited extent.

After ball milling Nb

2O

5 reduced with 0.25 eq. LiBH

4 for 60 min, the

11B spectrum shows mainly the signal of the probe head of the NMR device and no signal of pristine LiBH

4 at -42.0 ppm is detected. In addition, one can clearly see the structured signal of small spinning sidebands centered around 0.2 ppm and a broader shoulder at around 10 ppm, indicating the presence of an unknown, possibly partially oxidized boron species in the sample but only in very small amounts (

Figure 3b). This becomes clear when comparing the intensities to the spectrum of LiBH

4 shown in (

Figure 3a) in which the signal of the probe head is almost completely suppressed. However, as shown in

Figure 3c, the LiBH

4 starting material exhibits signals in the same region, which would match with tetrahedral BO

4 (around 0 ppm) and trigonal BO

3 (around 10 ppm) units [

43,

47]. Therefore, it cannot indefinitely be concluded that they form during the reduction process or are a simply present in the starting material. In any way, their overall concentration is very low which agrees with the low degree of reduction.

After washing, no spinning sidebands are visible anymore, meaning that all boron species were successfully removed by washing with water (

Figure 3c). Regarding the

7Li spectrum of Nb

2O

5 reduced with 0.25 eq. LiBH

4 for 60 min, all features discussed above in line with Li incorporation into the Nb

2O

5 are visible in the spectrum (

Figure 4b). The obtained C

Q parameter differs from the one of LiBH

4 (Supporting Information,

Table S1) which is qualitatively already visible by the differences in the range and the intensity profile of the spinning sideband manifold underlines the different crystallographic environment of the Li atom in LiBH

4 and the reduced Nb

2O

5. Ball milling Nb

2O

5 with 2 eq. LiBH

4 leads to almost identical looking

7Li spectra (Supporting Information,

Figures S10 and S11).

The examples in

Figure 4 are representative of the study. Two other

7Li spectra are shown in the Supporting Information (

Figures S10 and S11) looking almost identical to the one present here, meaning that the milling conditions appear to have no significant influence on the chemical environment of the lithium nucleus after reduction that can be detected with NMR spectroscopy.

Regarding the

11B solid-state MAS NMR of pristine NaBH

4, a featureless intense central transition at -42 ppm is observed (Supporting Information,

Figure S12a) in accordance with literature [

46]. Again, an additional signal at ~3 ppm shows the presence of unknown oxidic boron-containing species already in the starting material [

44,

48]. In contrast to the LiBH

4 niobia reduced sample, large amounts of unreacted NaBH

4 are still detected in the

11B MAS spectrum after ball milling Nb

2O

5 and 0.25 eq. NaBH

4 for 60 min, which is successfully removed during the washing process (Supporting Information,

Figure S12b). The presence of unreacted NaBH

4 in the as-milled sample indicates a lower conversion compared to using LiBH

4 as a reducing agent.

Overall, no significant amounts of solid boron-containing side-products are detected that can clearly be identified as side-products issuing from the reaction. Suspending the reaction mixture in deuterated acetonitrile after milling also gives no clear evidence for the formation of higher boranes or other soluble boron-containing species. On the other hand, the degree of reduction is rather low, especially with NaBH

4 as reducing agent, meaning that only small amounts of side products are to be expected. The low degree of reduction, the observed buffering effect and the rather complicated question of the formation of boron-containing by-products are less favorable compared to the use of alkali metal hydrides as reducing agents [

28].

Figure 3: (a) 11B MAS NMR spectra (black) of LiBH4 and fitted with a single Gaussian-Lorentz line (red). (b) Normalized 11B MAS NMR of the probe head measured with an empty rotor (black) in comparison to the washed (yellow) and unwashed (blue) Nb2O5 reduced with 0.25 eq. LiBH4 for 60 min. (c) Comparison of the magnified oxidic boron-containing side-phases present in pristine LiBH4 (black) and in Nb2O5 reduced with 0.25 eq. LiBH4 for 60 min (blue). For better comparison, both spectra are normalized to their respective intensity value at 0.12 ppm.

3.4. Raman and UV-Vis Absorbance Spectroscopy

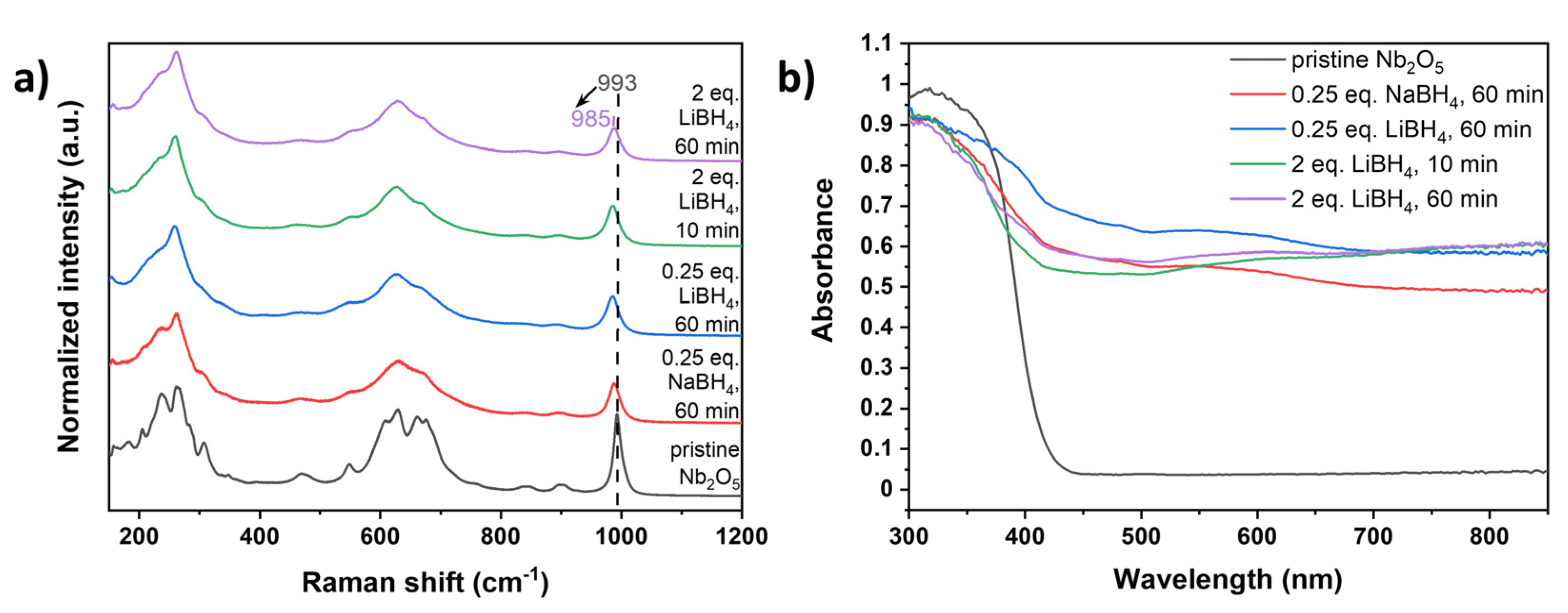

Raman spectroscopy was additionally employed to study structural changes during milling. As shown in

Figure 5a, all typical bands of monoclinic H-Nb

2O

5 remain detectable for both NaBH

4 and LiBH

4 reduced and washed samples. These include Nb-O-Nb angle-deformations between 160 to 300 cm

-1, transverse optic modes (TO) originating from symmetric stretching of NbO

6 octahedra between 600 and 700 cm

-1 and the longitudinal optic mode (LO) of NbO

6 edge-shared octahedra at around 990 cm

-1 [

42]. After mechanochemical reduction, a significant decrease in Raman activity and broadening of the observed bands were noted (

Figure 5a), particularly for LiBH

4 reduced samples, which also exhibited a red shift of the LO mode to up to 885 cm

-1. In line with PXRD and NMR analysis, it can therefore be concluded that the use of LiBH

4 as reducing agent leads to higher structural disorder caused by Li intercalation [

49] or formation of other defects during milling [

50] due to the higher degree of reduction.

Similarly, the optical properties were also affected by the mechanochemical reduction process. While the diffuse reflectance UV-Vis (DRS-UV-Vis) spectrum of pristine Nb

2O

5 shows only UV absorption with negligible absorbance in the visible and near-infrared (NIR) regions, all reduced samples demonstrated significantly enhanced absorption in these regions (

Figure 5b). This enhancement is attributed to the successful partial reduction and introduction of defects [

26], leading to a decrease in the optical band gap of up to 0.4 eV as determined using the Kubelka-Munk function (Supporting Information,

Figure S13,

Table S2).

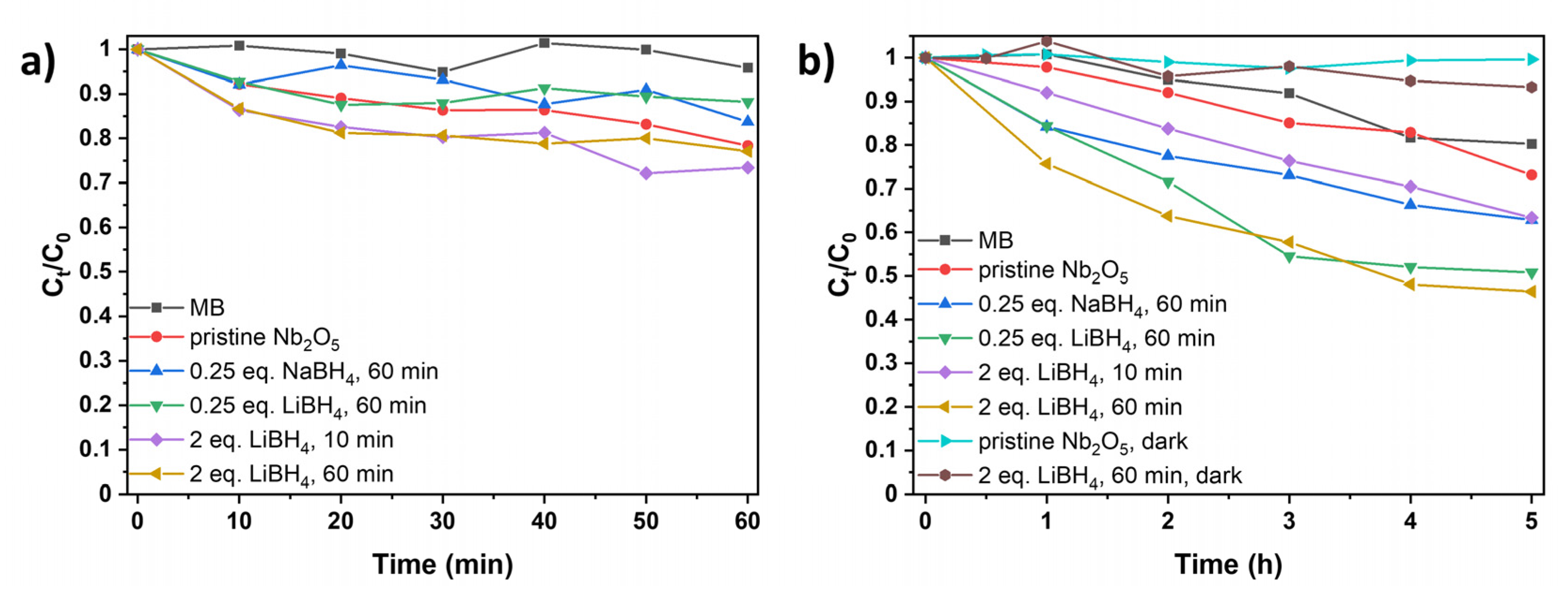

3.5. Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue

The enhancement of absorption properties across a broader wavelength range and the reduction of the optical band gap often improve the (photogenerated) charge carrier properties, leading to increased photocatalytic activity [

26], which we previously observed for our LiH reduced samples [

28]. Consequently, the photocatalytic activity of the borohydride reduced samples was evaluated through the degradation of methylene blue (MB), a common pollutant in textile wastewater [

51]. The photocatalytic degradation was tested under UV irradiation (365 nm) and visible light (400-700 nm, with the strongest irradiance being at around 450 and 550 nm). Control experiments without catalysts only showed minimal MB photobleaching (

Figure 6), while stirring MB with the photocatalyst in the absence of light also did not significantly reduce its concentration (

Figure 6b).

Under UV light, both pristine and reduced niobia show almost no activity as only 10 to 30% of MB are degraded after 60 min, depending on the synthesis conditions of the catalyst (

Figure 6a). While there is a slight improvement in the photocatalytic activity of the oxides prepared with 2 eq. LiBH

4 compared to the pristine material, both pristine and black niobia are less effective as UV photocatalysts compared to our previously synthesized black titania samples. [

28] In contrast, all tested black niobia samples show an enhanced performance under visible light compared to the pristine material. While pristine Nb

2O

5 degrades only 27% of MB in five hours, the degradation was improved to 37% when using the samples prepared with 0.25 eq. NaBH

4/60 min (blue) and 2 eq. LiBH

4/10 min (purple), as shown in

Figure 6b. Further milling with 0.25 (green) and 2 eq. (yellow) LiBH

4 resulted in 49 and 53% degradation, respectively, which is comparable to our LiH reduced material [

28].

These findings indicate that the partial mechanochemical reduction using alkali metal boron hydrides effectively enhances the photocatalytic properties of Nb

2O

5. Overall, the use of LiBH

4 as the more effective reducing agent, higher initial hydride concentrations and longer milling times favor the faster photocatalytic degradation of MB. This can be attributed to the partial reduction to Nb

4+ and the increased presence of defects and structural disorder, resulting in an enhanced light absorption across a wide range of wavelengths, reduced the optical band gap, and likely decreased recombination rate of photogenerated electron-hole pairs [

26,

52].

Figure 6: Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue (MB) (a) under UV (365 nm) and (b) under visible light without catalyst (black), with pristine niobia (red) and with reduced niobia (blue: 0.25 eq. NaBH4, 60 min; green: 0.25 eq. LiBH4, 60 min; purple: 2 eq. LiBH4, 10 min; yellow: 2 eq. LiBH4, 60 min). In (b), MB and Nb2O5 (turquoise), as well as LiBH4 reduced Nb2O5 (brown) are also stirred without illumination for comparison to stirring with illumination. Note the different time scales between (a) and (b).

5. Conclusions

In summary, the mechanochemical partial reduction of H-Nb2O5 using LiBH4 and NaBH4 as reducing agents at room temperature was systematically investigated, revealing a strong dependence on the type of the reducing agent. Due to a buffering effect regarding the transferred mechanical energy, large boron hydride concentrations do not benefit the reduction process. Structural analysis by PXRD measurements confirmed the retention of the Nb2O5 lattice, with Li+ intercalation leading to an increase in cell volume, as also supported by 7Li NMR spectroscopy. All reduced samples demonstrated enhanced visible light absorption and a band gap reduction of up to 0.4 eV compared to pristine niobia. Raman spectroscopy revealed increasing structural disorder due to the formation of defects, particularly for the stronger reduced LiBH4 samples. These defects contribute to significantly improved photocatalytic performance of the synthesized materials compared to pristine oxides under visible light illumination.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1: Photographs of Nb

2O

5 reduced with different amounts of NaBH

4 and LiBH

4 for different milling times.; Figure S2 Rietveld refinement of monoclinic H-Nb

2O

5 milled with 0.25 eq. NaBH

4 for 10 min.

Figures of merit: R

wp = 8.86, GOF = 4.19.; Figure S3: Rietveld refinement of monoclinic H-Nb

2O

5 milled with 0.25 eq. NaBH

4 for 60 min.

Figures of merit: R

wp = 5.24, GOF = 2.48.; Figure S4: Rietveld refinement of monoclinic H-Nb

2O

5 milled with 2 eq. NaBH

4 for 60 min.

Figures of merit: R

wp = 7.72, GOF = 3.66.; Figure S5: Rietveld refinement of monoclinic H-Nb

2O

5 milled with 0.25 eq. LiBH

4 for 60 min.

Figures of merit: R

wp = 7.11, GOF = 2.49.; Figure S6: Rietveld refinement of monoclinic H-Nb

2O

5 milled with 2 eq. LiBH

4 for 10 min.

Figures of merit: R

wp = 10.65, GOF = 5.57.; Figure S7: Rietveld refinement of monoclinic H-Nb

2O

5 milled with 2 eq. LiBH

4 for 60 min.

Figures of merit: R

wp = 9.39, GOF = 4.91.; Figure S8: Rietveld refinement of monoclinic H-Nb

2O

5 milled with 5 eq. LiBH

4 for 10 min.

Figures of merit: R

wp = 9.39, GOF = 4.91.; Figure S9: Evolution of the crystallite size as a function of milling time and (a) NaBH

4 and (b) LiBH

4 concentration, when only the crystallite size is refined. Analogous evolution of strain (c), (e) and strain (e), (f) as a function of milling time and hydride concentration, when both the crystallite size and the strain is refined. To accommodate experimental errors, the standard deviation of the strain calculated by Topas was multiplied by a factor of three.; Figure S10:

7Li MAS NMR spectrum of Nb

2O

5 + LiBH

4 (1:2) after 10 minutes with a single line shape simulation.; Figure S11:

7Li MAS NMR spectrum of Nb

2O

5 + LiBH

4 (1:2) after 60 minutes with a single line shape simulation.; Table S1: Summary of the

7Li and

11B solid state NMR spectroscopic observables obtained for LiBH

4 and three selected samples of LiBH

4 reduced Nb

2O

5 extracted from the DMFit software with δ being the observed resonance (in ppm) and C

Q being the quadrupolar parameter (in kHz) refined for η

Q = 0 and 1; Figure S12: (a)

11B MAS NMR of pristine NaBH

4. (b)

11B MAS NMR of the probe head measured with an empty rotor (black) in comparison to the washed (yellow) and unwashed (blue) Nb

2O

5 reduced with 0.25 eq. NaBH

4 for 60 min.; Figure S13: Kubelka-Munk plot of pristine Nb

2O

5 (black) and with NaBH

4 (0.25 eq./60 min, red) and LiBH

4 (0.25 eq./60 min, blue; 2 eq./10 min, green; 2 eq./60 min, purple) reduced Nb

2O

5.; Table S2: Optical band gaps of pristine and reduced niobia determined using the Kubelka-Munk function.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M. and G.K.; methodology, A.M. and E.C.J.G.; investigation, A.M.; resources, G.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.; writing—review and editing, E.C.J.G. and G.K.; supervision, G.K.; project administration, G.K.; funding acquisition, G.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

Instrumentation and technical assistance for this work were provided by the Service Center X-ray Diffraction, with financial support from Saarland University and German Science Foundation (project number INST 256/349-1).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Petra Herbeck-Engel from the INM-Leibniz Institute for New Materials, Saarbrücken for Raman measurements, as well as Dr. Clemens Matt and Haakon Wiedemann, Physical Chemistry and Chemistry Education, Saarland University for continuous-wave EPR measurements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process: During the preparation of this work, the authors employed AI-based tools, including DeepL.com and ChatGPT, to improve language clarity and correct spelling, punctuation, and grammatical errors. Following the use of these tools, the authors thoroughly reviewed and revised the content as needed, ensuring its accuracy and integrity. The authors take full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Cava, R. J.; Murphy, D. W.; Zahurak, S. M. Lithium Insertion in Wadsley-Roth Phases Based on Niobium Oxide. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1983, 130, 2345–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M. R. N.; Leite, S.; Nico, C.; Peres, M.; Fernandes, A. J. S.; Graça, M. P. F.; Matos, M.; Monteiro, R.; Monteiro, T.; Costa, F. M. Effect of processing method on physical properties of Nb2O5. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 31, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Viet, A.; Reddy, M. V.; Jose, R.; Chowdari, B. V. R.; Ramakrishna, S. Nanostructured Nb2O5 Polymorphs by Electrospinning for Rechargeable Lithium Batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, M. P. F.; Meireles, A.; Nico, C.; Valente, M. A. Nb2O5 nanosize powders prepared by sol-gel-Structure, morphology and dielectric properties. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 553, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambon, L.; Maleysson, C.; Pauly, A.; Germain, J. P.; Demarne, V.; Grisel, A. Investigation, for NH3 gas sensing applications, of the Nb2O5 semiconducting oxide in the presence of interferent species such as oxygen and humidity. Sens. Actuator B Chem. 1997, 45, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambon, L.; Pauly, A.; Germain, J. P.; Maleysson, C.; Demarne, V.; Grisel, A. A model for the responses of Nb2O5 sensors to CO and NH3 gases. Sens. Actuator B Chem. 1997, 43, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Viet, A.; Jose, R.; Reddy, M. V.; Chowdari, B. V. R.; Ramakrishna, S. Nb2O5 photoelectrodes for dye-sensitized solar cells: Choice of the polymorph. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 21795–21800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Liu, H.; Gao, Z.; Fornasiero, P.; Wang, F. Nb2O5-Based Photocatalysts. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Huang, F. Black titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanomaterials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 1861–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Yu, P. Y.; Mao, S. S. Increasing Solar Absorption for Photocatalysis with Black Hydrogenated Titanium Dioxide Nanocrystals. Science 2011, 331, 746–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Zhu, G.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, W.; Yang, C.; Lin, T.; Gu, H.; Huang, F. Black nanostructured Nb2O5 with improved solar absorption and enhanced photoelectrochemical water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 11830–11837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhao, W.; Zhu, G.; Lin, T.; Xu, F.; Huang, F. Black Nb2O5 nanorods with improved solar absorption and enhanced photocatalytic activity. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 3888–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinhamahapatra, A.; Jeon, J.-P.; Kang, J.; Han, B.; Yu, J.-S. Oxygen-Deficient Zirconia (ZrO2-x): A New Material for Solar Light Absorption. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsukawa, T.; Ishigaki, T. Effect of isothermal holding time on hydrogen-induced structural transitions of WO3. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 7590–7596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badreldin, A.; Imam, M. D.; Wubulikasimu, Y.; Elsaid, K.; Abusrafa, A. E.; Balbuena, P. B.; Abdel-Wahab, A. Surface microenvironment engineering of black V2O5 nanostructures for visible light photodegradation of methylene blue. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 871, 159615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S.; Cook, J. B.; Lin, H.; Ko, J. S.; Tolbert, S. H.; Ozolins, V.; Dunn, B. Oxygen vacancies enhance pseudocapacitive charge storage properties of MoO3-x. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Yang, R.; Wu, S.; Shen, D.; Jiao, T.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, W.; Lee, C.-S. Surface-Engineered Black Niobium Oxide@Graphene Nanosheets for High-Performance Sodium-/Potassium-Ion Full Batteries. Small 2019, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Xia, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, S.; Chen, Y.; Chen, S.; Ding, B.; Yu, J.; Yan, J. Fabrication of Flexible Mesoporous Black Nb2O5 Nanofiber Films for Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction into CH4. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Fan, Y.; Hu, K.; Jiang, L.; Tan, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, A.; Yang, S.; Hu, Y.; Gu, H. Fast, Sensitive, and Highly Selective Room-Temperature Hydrogen Sensing of Defect-Rich Orthorhombic Nb2O5–x Nanobelts with an Abnormal p-Type Sensor Response. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 25937–25948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Wang, J.; Duan, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, H.; Xiao, Q.; Lin, H. Anionic oxygen vacancies in Nb2O5-x/carbon hybrid host endow rapid catalytic behaviors for high-performance high areal loading lithium sulfur pouch cell. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 417, 128172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Cui, Y.; Kang, R.; Zou, B.; Ng, D. H. L.; El-Khodary, S. A.; Liu, X.; Qiu, J.; Lian, J.; Li, H. Oxygen vacancies boosted the electrochemical kinetics of Nb2O5−x for superior lithium storage. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 8182–8185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, D.; Zhang, Z.; Li, G.; Cheng, S.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Gao, R.; Li, M.; Sy, S.; Deng, Y.-P.; et al. Revealing the Rapid Electrocatalytic Behavior of Ultrafine Amorphous Defective Nb2O5-x Nanocluster toward Superior Li-S Performance. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 4849–4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo, M. A.; Gromboni, M. F.; Marken, F.; Parker, S. C.; Peter, L. M.; Turner, J.; Aspinall, H. C.; Black, K.; Mascaro, L. H. Contrasting transient photocurrent characteristics for thin films of vacuum-doped “grey” TiO2 and “grey” Nb2O5. Appl. Catal. B 2018, 237, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; García, F. Main group mechanochemistry: from curiosity to established protocols. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 2274–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Pei, Q.; Chen, W.; Liu, L.; He, T.; Chen, P. Room temperature synthesis of reduced TiO2 and its application as a support for catalytic hydrogenation. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 4306–4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, G.; Xu, Y.; Wen, B.; Lin, R.; Ge, B.; Tang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Yang, C.; Huang, K.; Zu, D.; et al. Tuning defects in oxides at room temperature by lithium reduction. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, N.; Schmidt, J.; Kahnt, A.; Osvet, A.; Romeis, S.; Zolnhofer, E. M.; Marthala, V. R. R.; Guldi, D. M.; Peukert, W.; et al. Noble-Metal-Free Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Activity: The Impact of Ball Milling Anatase Nanopowders with TiH2. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1604747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaely, A.; Janka, O.; Gießelmann, E. C. J.; Haberkorn, R.; Wiedemann, H. T. A.; Kay, C. W. M.; Kickelbick, G. Black Titania and Niobia within Ten Minutes – Mechanochemical Reduction of Metal Oxides with Alkali Metal Hydrides. Chem. Eur. J. 2023, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topas 5; Karlsruhe (Germany), 2014.

- Cheary, R. W.; Coelho, A. A.; Cline, J. P. Fundamental Parameters Line Profile Fitting in Laboratory Diffractometers. J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 2004, 109, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson's Crystal Data: Crystal Structure Database for Inorganic Compounds. Release 2022/23; ASM International®: Materials Park: Ohio (USA), 2023.

- Topspin 2.1; Bruker Corp.: Karlsruhe, Germany, 2008.

- Massiot, D.; Fayon, F.; Capron, M.; King, I.; Le Calvé, S.; Alonso, B.; Durand, J.-O.; Bujoli, B.; Gan, Z.; Hoatson, G. Modelling one- and two-dimensional solid-state NMR spectra. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2002, 40, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, H.; Gruehn, R.; Schulte, F. The Modifications of Niobium Pentoxide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1966, 5, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Khan, G. G. The formation and detection techniques of oxygen vacancies in titanium oxide-based nanostructures. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 3414–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santara, B.; Giri, P. K.; Imakita, K.; Fujii, M. Evidence of oxygen vacancy induced room temperature ferromagnetism in solvothermally synthesized undoped TiO2 nanoribbons. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 5476–5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Li, G.; Luo, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, G.; Shui, L.; Wang, X.; Chen, Z. Engineering the Conductive Network of Metal Oxide-Based Sulfur Cathode toward Efficient and Longevous Lithium–Sulfur Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, R. D. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr. A 1976, 32, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B.R, V. K.; Dasgupta, A.; Ghosh, C.; Sinha, S. K. Analysis of structural transformation in nanocrystalline Y2O3 during high energy ball milling. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 900, 163550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S. K.; Shee, S. K.; Chanda, A.; Bose, P.; De, M. X-ray studies on the kinetics of microstructural evolution of Ni3Al synthesized by ball milling elemental powders. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2001, 68, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadef, F.; Ans, M. X-ray analysis and Rietveld refinement of ball milled Fe50Al35Ni15 powder. Surfaces and Interfaces 2021, 26, 101303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J. L.; Cao, Q.; Browne, D. L. Mechanochemistry as an emerging tool for molecular synthesis: What can it offer? Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 3080–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, A.; Tobschall, E.; Heitjans, P. Li Ion Diffusion in Nanocrystalline and Nanoglassy LiAlSi2O6 and LiBO2 - Structure-Dynamics Relations in Two Glass Forming Compounds. Z. Phys. Chem. 2009, 223, (10–11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.; Jia, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Ouyang, L.; Zhu, M.; Yao, X. NaBH4 regeneration from NaBO2 by high-energy ball milling and its plausible mechanism. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 13127–13135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnbjerg, L. M.; Ravnsbæk, D. B.; Filinchuk, Y.; Vang, R. T.; Cerenius, Y.; Besenbacher, F.; Jørgensen, J.-E.; Jakobsen, H. J.; Jensen, T. R. Structure and Dynamics for LiBH4−LiCl Solid Solutions. Chem. Mater. 2009, 21, 5772–5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łodziana, Z.; Błoński, P.; Yan, Y.; Rentsch, D.; Remhof, A. NMR Chemical Shifts of 11B in Metal Borohydrides from First-Principle Calculations. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 6594–6603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroeker, S.; Stebbins, J. F. Three-coordinated Boron-11 chemical shifts in borates. Inorg. Chem. 2001, 40, 6239–6246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J. W. E.; Bryce, D. L. A solid-state 11B NMR and computational study of boron electric field gradient and chemical shift tensors in boronic acids and boronic esters. J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 114, 5119–5131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strelchuk, V. V.; Budzulyak, S. I.; Budzulyak, I. M.; Ilnytsyy, R. V.; Kotsyubynskyy, V. O.; Segin, M. Y.; Yablon, L. S. Raman spectroscopy of the laser irradiated titanium dioxide. Semicond. Phys. Quantum Electron. Optoelectron. 2010, 13, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, S. K.; Singh, F.; Sulania, I.; Singh, R. G.; Kulriya, P. K.; Pippel, E. Micro-Raman study on the softening and stiffening of phonons in rutile titanium dioxide film: Competing effects of structural defects, crystallite size, and lattice strain. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladoye, P. O.; Ajiboye, T. O.; Omotola, E. O.; Oyewola, O. J. Methylene blue dye: Toxicity and potential elimination technology from wastewater. Results Eng. 2022, 16, 100678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinhamahapatra, A.; Jeon, J.-P.; Yu, J.-S. A new approach to prepare highly active and stable black titania for visible light-assisted hydrogen production. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 3539–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).