Submitted:

14 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Connectome Extraction

- the unique IDs of the pre-synaptic and post-synaptic neuron,

- the Cleft score: a measure of how well-defined the synaptic cleft is,

- the Connection score: a measure of the size of the synapse,

- the probability of the synaptic neurotransmitter being Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid, Acetylcholine, Glutamate, Octopamine, Serotonin, or Dopamine.

2.2. Echo-State Network

2.3. Time Series Generation

2.4. Experimental Protocol

3. Results

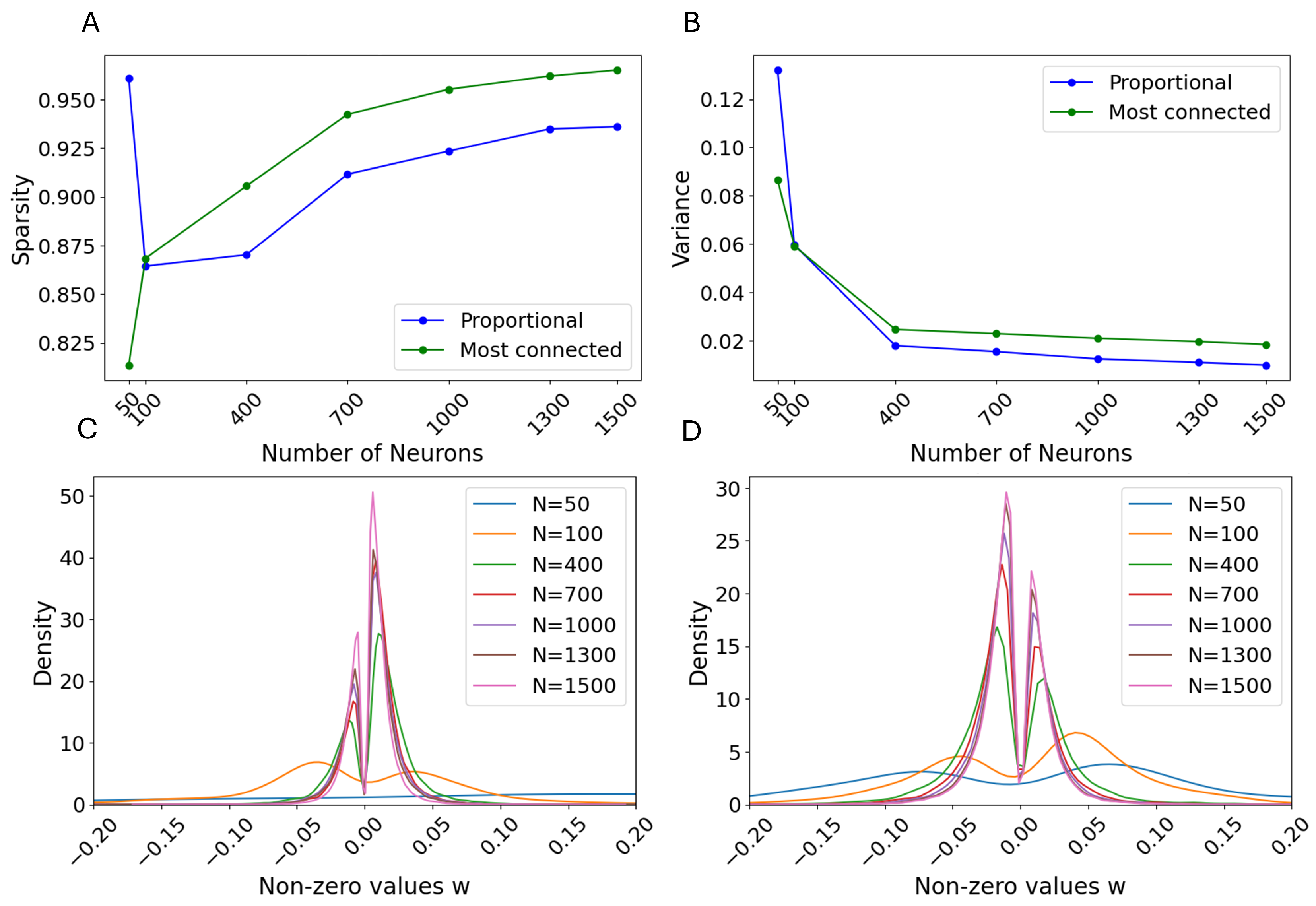

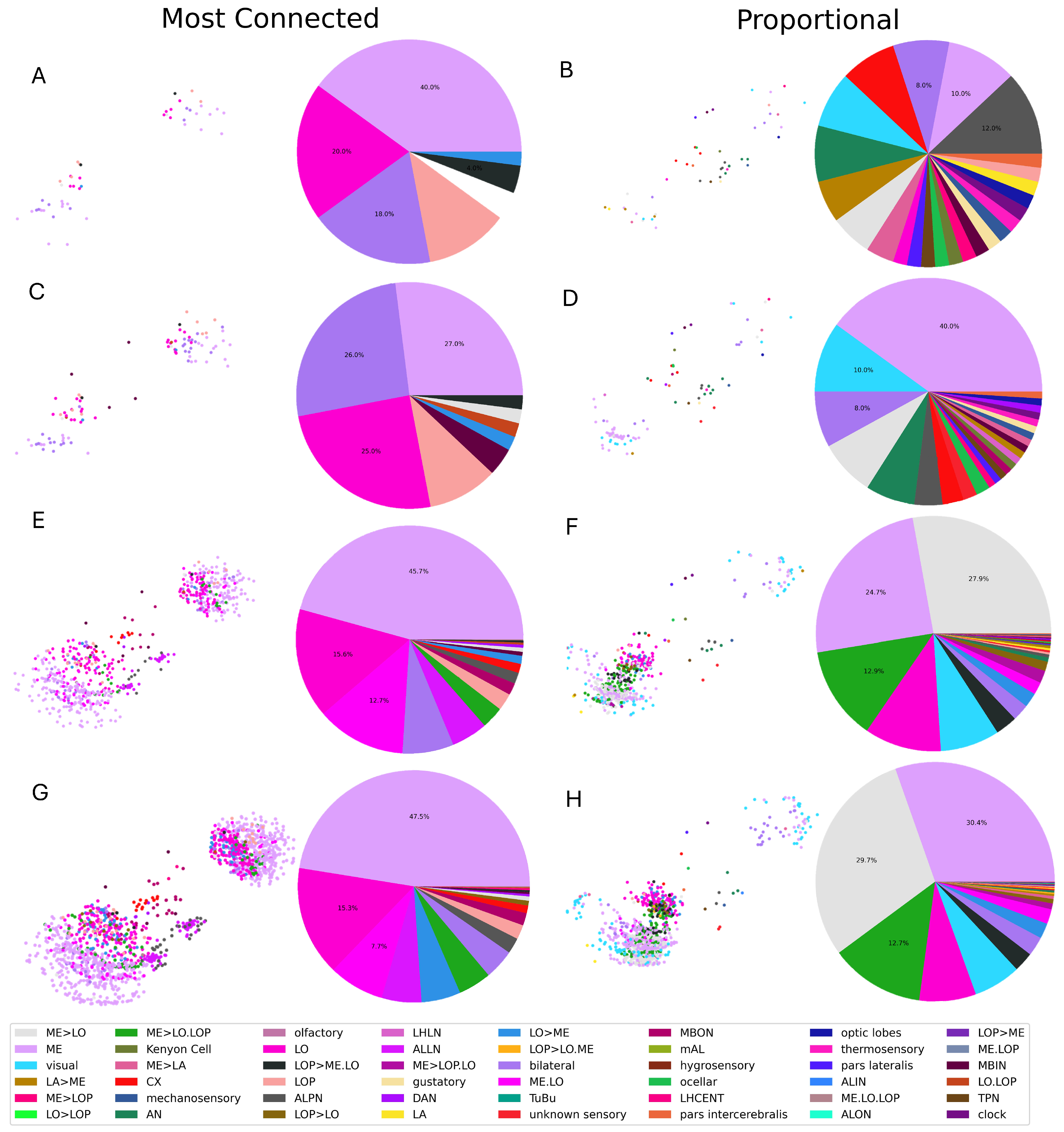

3.1. Selection Criteria

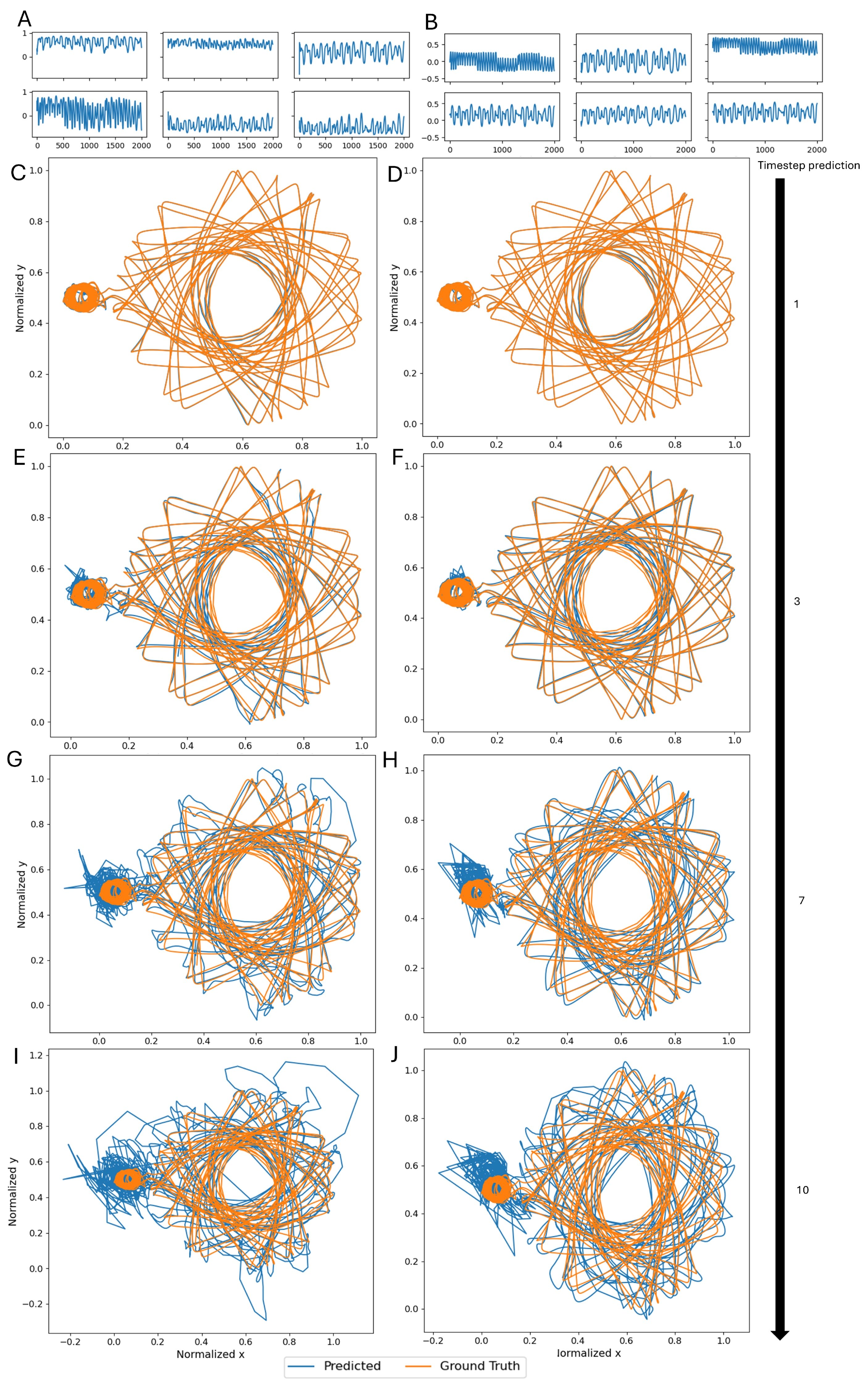

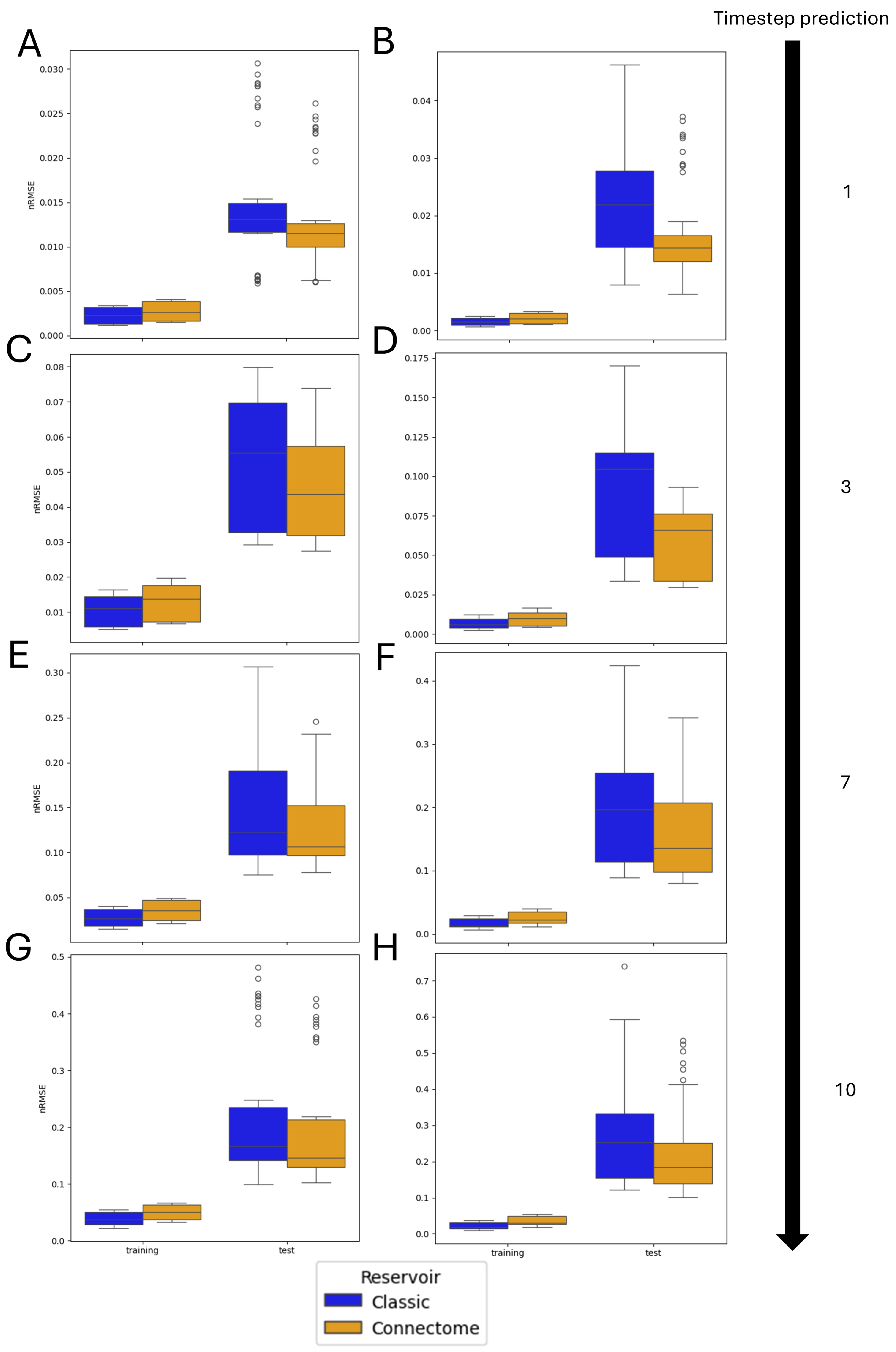

3.2. Single Simulation

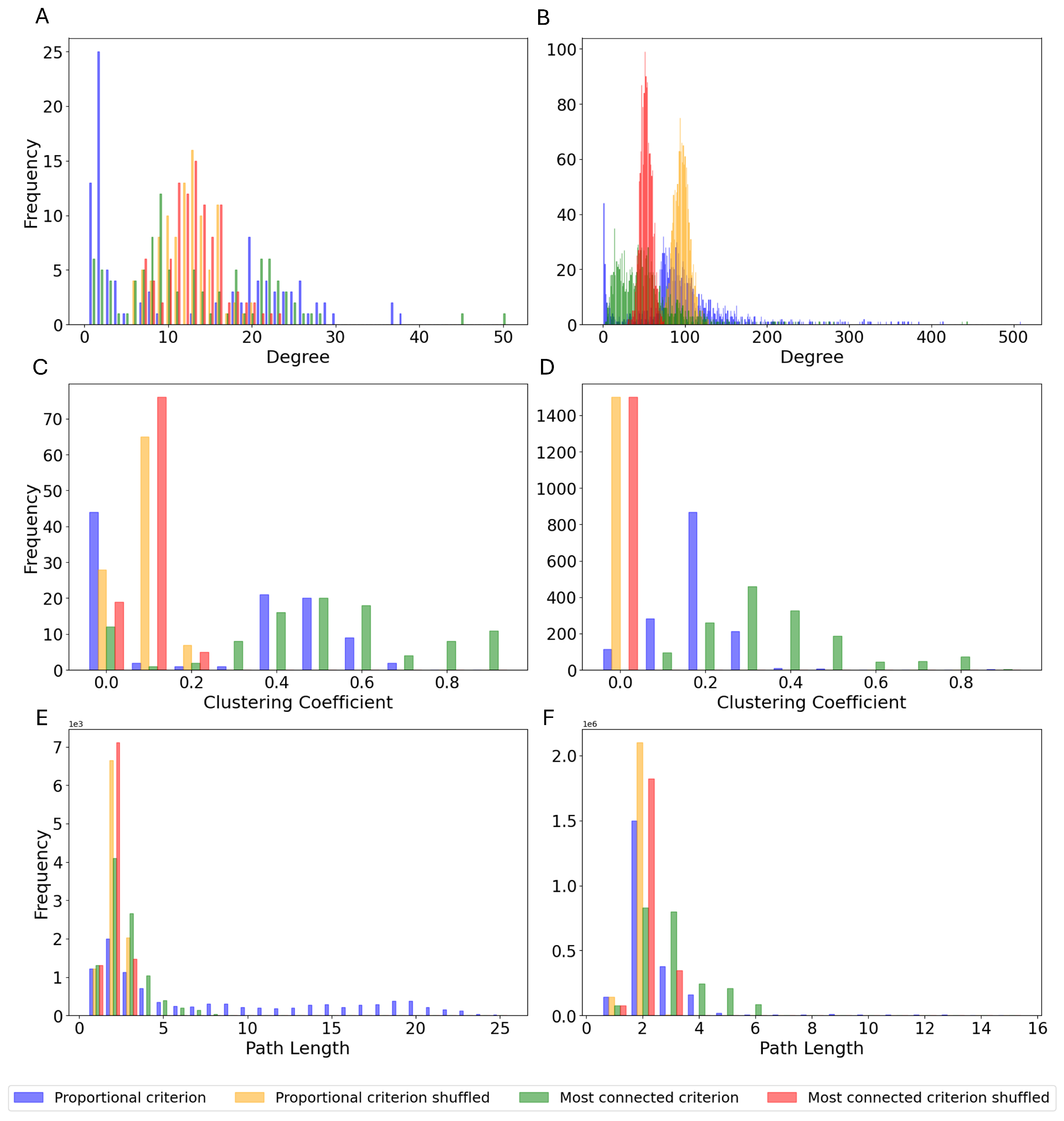

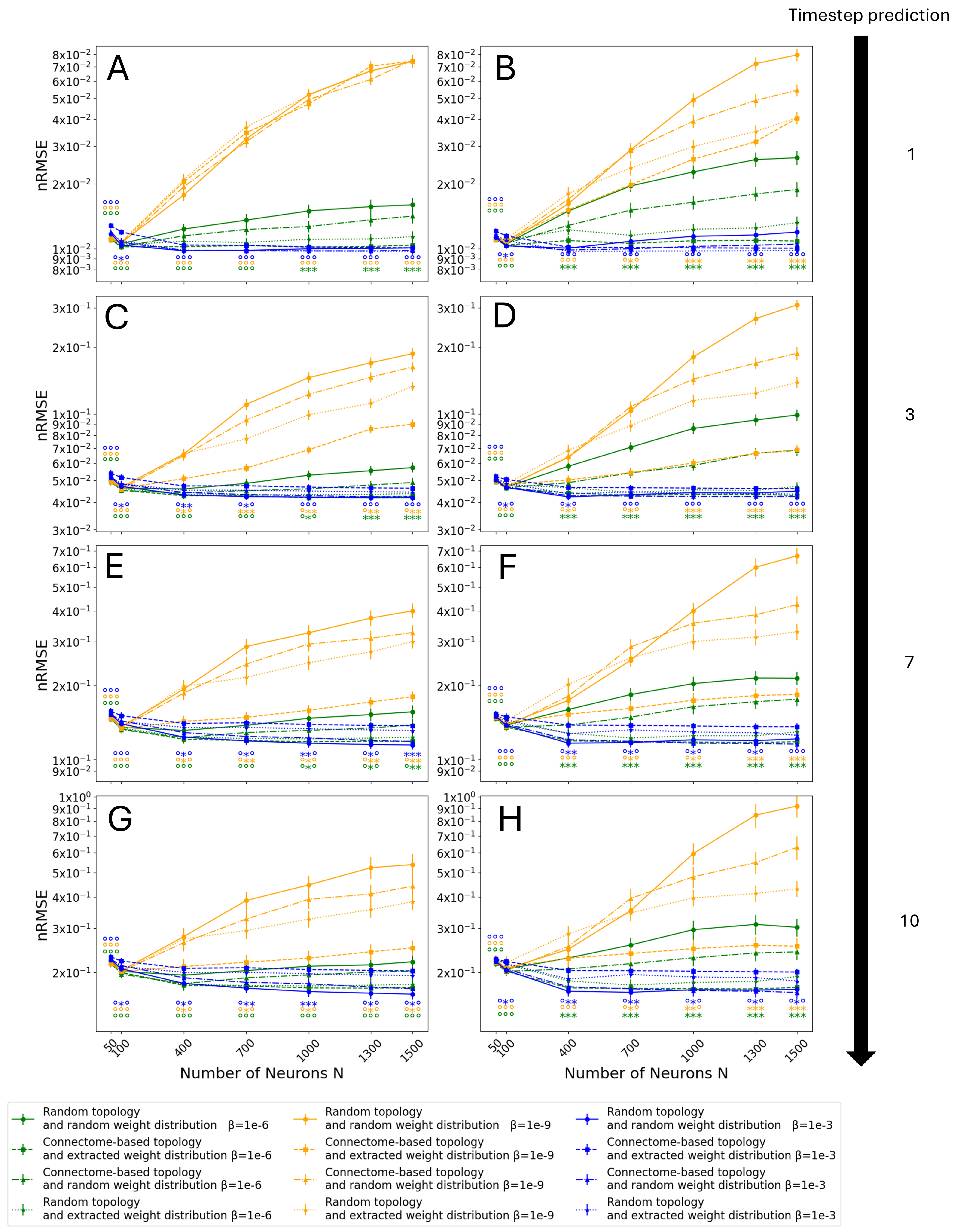

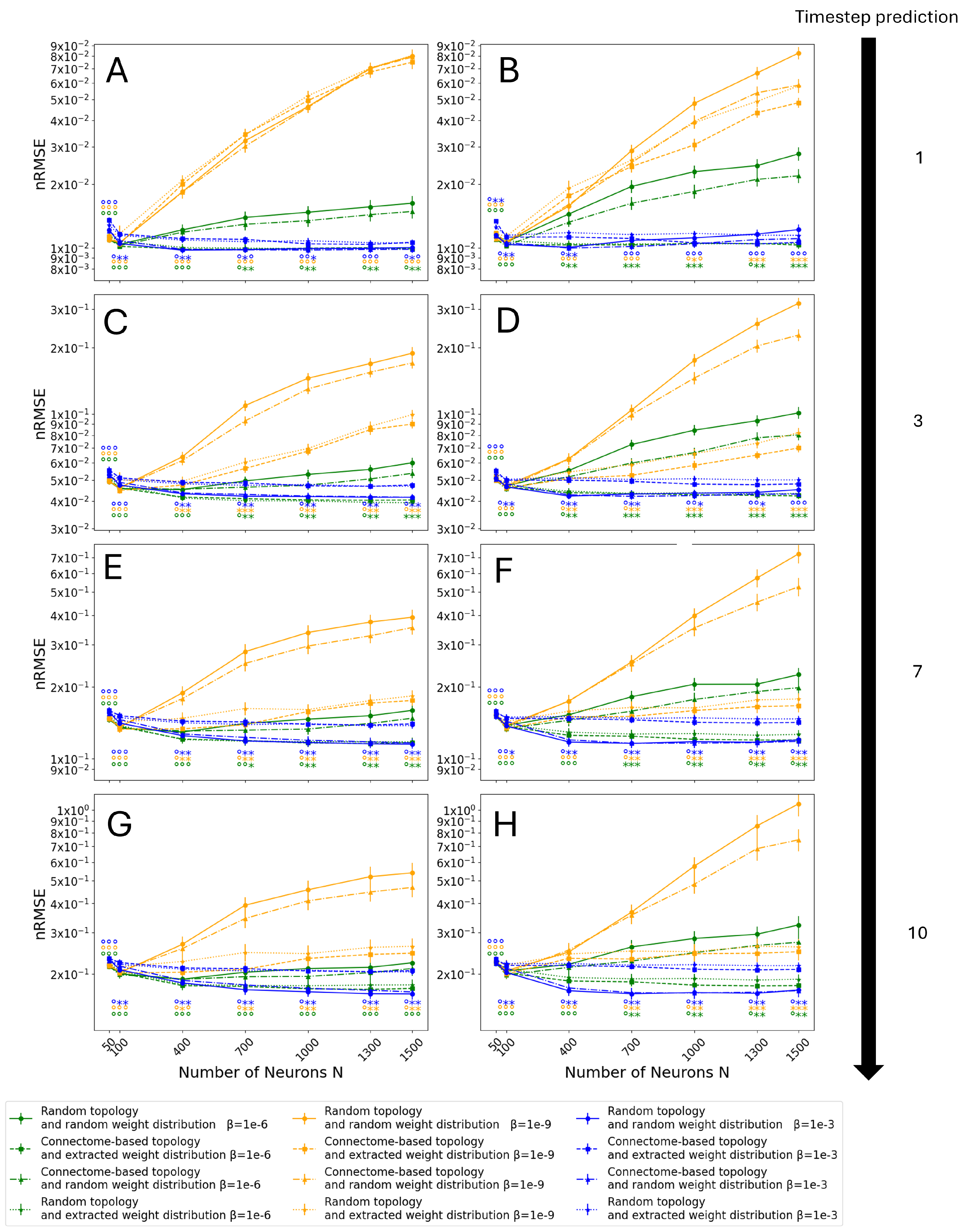

3.3. Monte Carlo Simulations

- Random topology and random weight distribution, which is the standard way to create ESNs and it represents the control group.

- Connectome-based topology and extracted weight distribution, utilizing all the data extracted from the Drosophila connectome.

- Connectome-based topology and random weight distribution, to isolate solely the contribution of the topology of the connectome.

- Random topology and extracted weight distribution, to isolate solely the contribution of the weight distribution of the connectome.

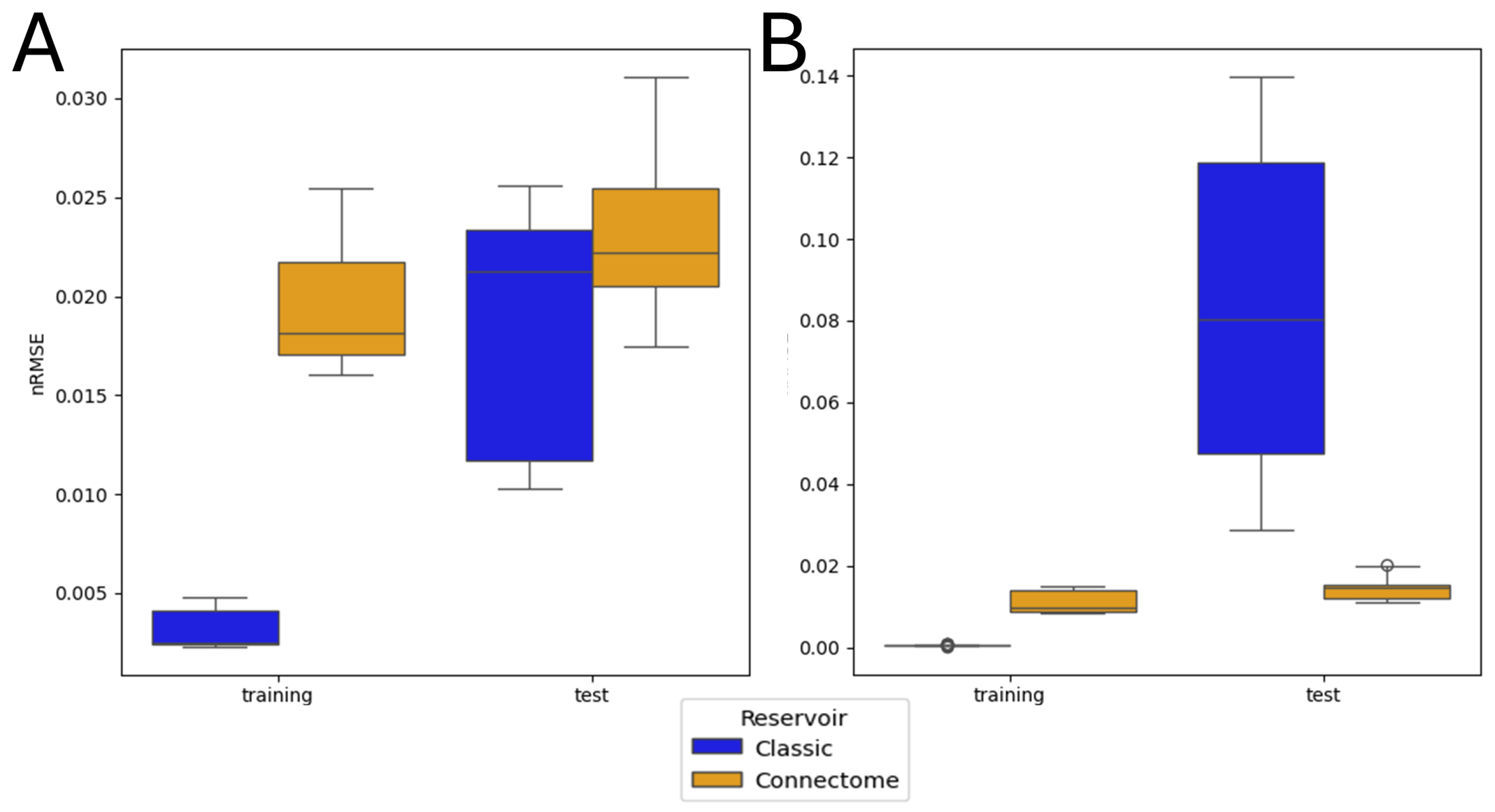

3.4. Entire Connectome Simulations

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Narayanan, D.; Shoeybi, M.; Casper, J.; LeGresley, P.; Patwary, M.; Korthikanti, V.; Vainbrand, D.; Kashinkunti, P.; Bernauer, J.; Catanzaro, B.; et al. Efficient large-scale language model training on gpu clusters using megatron-lm. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis, 2021, pp. 1–15.

- Kaplan, J.; McCandlish, S.; Henighan, T.; Brown, T.B.; Chess, B.; Child, R.; Gray, S.; Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Amodei, D. Scaling laws for neural language models. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2001.08361. [Google Scholar]

- Henighan, T.; Kaplan, J.; Katz, M.; Chen, M.; Hesse, C.; Jackson, J.; Jun, H.; Brown, T.B.; Dhariwal, P.; Gray, S.; et al. Scaling laws for autoregressive generative modeling. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.14701. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Qiu, X. A survey of transformers. AI open 2022, 3, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Naseer, M.; Hayat, M.; Zamir, S.W.; Khan, F.S.; Shah, M. Transformers in vision: A survey. ACM computing surveys (CSUR) 2022, 54, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, L.; Zhang, J.; Humaidi, A.J.; Al-Dujaili, A.; Duan, Y.; Al-Shamma, O.; Santamaría, J.; Fadhel, M.A.; Al-Amidie, M.; Farhan, L. Review of deep learning: concepts, CNN architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. Journal of big Data 2021, 8, 1–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Si, X.; Hu, C.; Zhang, J. A review of recurrent neural networks: LSTM cells and network architectures. Neural computation 2019, 31, 1235–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, A.K.; Pillai, G.; Chakrabarty, S. Reinforcement learning algorithms: A brief survey. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 231, 120495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoch, S.; Chauhan, S.S.; Kumar, V. A review on genetic algorithm: past, present, and future. Multimedia tools and applications 2021, 80, 8091–8126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, R.; Liu, J.; Huang, B. A review on reinforcement learning: Introduction and applications in industrial process control. Computers & Chemical Engineering 2020, 139, 106886. [Google Scholar]

- Lukoševičius, M.; Jaeger, H. Reservoir computing approaches to recurrent neural network training. Computer science review 2009, 3, 127–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrauwen, B.; Verstraeten, D.; Van Campenhout, J. An overview of reservoir computing: theory, applications and implementations. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 15th european symposium on artificial neural networks. p. 471-482 2007, 2007, pp. 471–482.

- Cressie, N.; Sainsbury-Dale, M.; Zammit-Mangion, A. Basis-function models in spatial statistics. Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application 2022, 9, 373–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, G.; Mazur, T.; Szaciłowski, K. An organized view of reservoir computing: a perspective on theory and technology development. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics 2024, 63, 050803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucchi, M.; Abreu, S.; Ciccone, G.; Brunner, D.; Kleemann, H. Hands-on reservoir computing: a tutorial for practical implementation. Neuromorphic Computing and Engineering 2022, 2, 032002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, H.; Fuechslin, R.M.; Nakajima, K. Morphological computation: The body as a computational resource. In Opinions and Outlooks on Morphological Computation; Self-published, 2014; pp. 226–244.

- Nakajima, K.; Hauser, H.; Li, T.; Pfeifer, R. Information processing via physical soft body. Scientific reports 2015, 5, 10487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülser, T.; Köster, F.; Jaurigue, L.; Lüdge, K. Role of delay-times in delay-based photonic reservoir computing. Optical Materials Express 2022, 12, 1214–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Huang, C.; Bienstman, P.; Tino, P.; Lin, W.; Sun, J. Emerging opportunities and challenges for the future of reservoir computing. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.; Tang, J.; Li, X.; Liang, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Xi, Y.; Yao, P.; Hao, Z.; Gao, B.; et al. A memristor-based analogue reservoir computing system for real-time and power-efficient signal processing. Nature Electronics 2022, 5, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Renda, F.; Le Gall, A.; Mocellin, L.; Bernabei, M.; Dangel, T.; Ciuti, G.; Cianchetti, M.; Stefanini, C. Data-driven methods applied to soft robot modeling and control: A review. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margin, D.A.; Ivanciu, I.A.; Dobrota, V. Deep reservoir computing using echo state networks and liquid state machine. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Black Sea Conference on Communications and Networking (BlackSeaCom). IEEE, 2022, pp. 208–213.

- Soures, N.; Merkel, C.; Kudithipudi, D.; Thiem, C.; McDonald, N. Reservoir computing in embedded systems: Three variants of the reservoir algorithm. IEEE Consumer Electronics Magazine 2017, 6, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukoševičius, M. A practical guide to applying echo state networks. In Neural Networks: Tricks of the Trade: Second Edition; Springer, 2012; pp. 659–686.

- Rodan, A.; Tino, P. Minimum complexity echo state network. IEEE transactions on neural networks 2010, 22, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viehweg, J.; Worthmann, K.; Mäder, P. Parameterizing echo state networks for multi-step time series prediction. Neurocomputing 2023, 522, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallicchio, C.; Micheli, A. Deep echo state network (deepesn): A brief survey. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.04323. [Google Scholar]

- Moroz, L.L. On the independent origins of complex brains and neurons. Brain Behavior and Evolution 2009, 74, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marder, E.; Goaillard, J.M. Variability, compensation and homeostasis in neuron and network function. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2006, 7, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöfmann, C.M.; Fasli, M.; Barros, M. Biologically Plausible Neural Networks for Reservoir Computing Solutions. Authorea Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Armendarez, N.X.; Mohamed, A.S.; Dhungel, A.; Hossain, M.R.; Hasan, M.S.; Najem, J.S. Brain-inspired reservoir computing using memristors with tunable dynamics and short-term plasticity. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2024, 16, 6176–6188. [Google Scholar]

- Sumi, T.; Yamamoto, H.; Katori, Y.; Ito, K.; Moriya, S.; Konno, T.; Sato, S.; Hirano-Iwata, A. Biological neurons act as generalization filters in reservoir computing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2023, 120, e2217008120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Parhi, K.K. Reservoir computing using DNA oscillators. ACS Synthetic Biology 2022, 11, 780–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damicelli, F.; Hilgetag, C.C.; Goulas, A. Brain connectivity meets reservoir computing. PLoS Computational Biology 2022, 18, e1010639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morra, J.; Daley, M. Using connectome features to constrain echo state networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–8.

- Schlegel, P.; Yin, Y.; Bates, A.S.; Dorkenwald, S.; Eichler, K.; Brooks, P.; Han, D.S.; Gkantia, M.; Dos Santos, M.; Munnelly, E.J.; et al. Whole-brain annotation and multi-connectome cell typing of Drosophila. Nature 2024, 634, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.G.; Southgate, E.; Thomson, J.N.; Brenner, S.; et al. The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 1986, 314, 1–340. [Google Scholar]

- Bardozzo, F.; Terlizzi, A.; Simoncini, C.; Lió, P.; Tagliaferri, R. Elegans-AI: How the connectome of a living organism could model artificial neural networks. Neurocomputing 2024, 584, 127598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morra, J.; Daley, M. Imposing Connectome-Derived topology on an echo state network. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–6.

- Wie, B. Space vehicle dynamics and control; Aiaa, 1998.

- Perraudin, N.; Srivastava, A.; Lucchi, A.; Kacprzak, T.; Hofmann, T.; Réfrégier, A. Cosmological N-body simulations: a challenge for scalable generative models. Computational Astrophysics and Cosmology 2019, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nudell, B.M.; Grinnell, A.D. Regulation of synaptic position, size, and strength in anuran skeletal muscle. Journal of Neuroscience 1983, 3, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holler, S.; Köstinger, G.; Martin, K.A.; Schuhknecht, G.F.; Stratford, K.J. Structure and function of a neocortical synapse. Nature 2021, 591, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, G.C. Ridge regression. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics 2009, 1, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscani, F.; Izzo, D. heyoka: High-precision Taylor integration of ordinary differential equations, 2025. Accessed: 2025-03-23.

- Nishimura, R.; Fukushima, M. Comparing Connectivity-To-Reservoir Conversion Methods for Connectome-Based Reservoir Computing. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–8.

- Matsumoto, I.; Nobukawa, S.; Kurikawa, T.; Wagatsuma, N.; Sakemi, Y.; Kanamaru, T.; Sviridova, N.; Aihara, K. Optimal excitatory and inhibitory balance for high learning performance in spiking neural networks with long-tailed synaptic weight distributions. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–8.

- Blass, A.; Harary, F. Properties of almost all graphs and complexes. Journal of Graph Theory 1979, 3, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, L.K.; Xu, C.S.; Januszewski, M.; et al. A Connectome and Analysis of the Adult Drosophila Central Brain. eLife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Neuron Class | Full Name | Function | Neuron Class | Full Name | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CX | Central Complex | Motor control, navigation | Kenyon Cell | Kenyon Cell | Learning and memory |

| ALPN | Antennal Lobe Projection Neuron | Olfactory signal relay | LO | Lamina Output Neuron | Early visual processing |

| bilateral | Bilateral Neuron | Cross-hemisphere connections | ME | Medulla Neuron | Visual processing |

| ME>LOP | Medulla to Lobula Plate | Motion detection | ME>LO | Medulla to Lobula | Higher-order vision |

| LO>LOP | Lobula to Lobula Plate | Object motion detection | ME>LA | Medulla to Lamina | Visual contrast enhancement |

| LA>ME | Lamina to Medulla | Photoreceptor signal relay | ME>LO.LOP | Medulla to Lobula and Lobula Plate | Motion and feature integration |

| ALLN | Allatotropinergic Neuron | Hormonal regulation | olfactory | Olfactory Neuron | Detects airborne stimuli |

| DAN | Dopaminergic Neuron | Learning, reward, motivation | MBON | Mushroom Body Output Neuron | Readout of learned behaviors |

| ME>LOP.LO | Medulla to Lobula Plate and Lobula | Visual integration | LOP>ME.LO | Lobula Plate to Medulla and Lobula | Motion-sensitive feedback |

| LOP | Lobula Plate Neuron | Optic flow detection | LOP>LO.ME | Lobula Plate to Lobula and Medulla | Visual-motor integration |

| LOP>LO | Lobula Plate to Lobula | Motion-sensitive projection | LA | Lamina Neuron | First visual synaptic layer |

| AN | Antennal Neuron | Mechanosensory and olfactory processing | visual | Visual Neuron | General vision processing |

| TuBu | Tubercle Bulb Neuron | Connects brain to vision | LHCENT | Lateral Horn Centroid | Odor valence processing |

| ALIN | Antennal Lobe Interneuron | Olfactory modulation | mAL | Mushroom Body-associated Antennal Lobe Neuron | Olfactory-learning link |

| LHLN | Lateral Horn Local Neuron | Innate odor-driven behavior | ME.LO | Medulla and Lobula Neuron | General vision processing |

| mechanosensory | Mechanosensory Neuron | Touch, vibration detection | ME.LO.LOP | Medulla, Lobula, and Lobula Plate Neuron | Multi-layer vision processing |

| LO>ME | Lobula to Medulla | Visual feedback | hygrosensory | Hygrosensory Neuron | Detects humidity |

| pars lateralis | Pars Lateralis Neuron | Hormonal/circadian regulation | unknown sensory | Unknown Sensory Neuron | Uncharacterized sensory function |

| LO.LOP | Lobula and Lobula Plate Neuron | Motion and space awareness | ocellar | Ocellar Neuron | Light intensity detection |

| optic lobes | Optic Lobe Neuron | General vision processing | pars intercerebralis | Pars Intercerebralis Neuron | Hormonal regulation |

| ME.LOP | Medulla and Lobula Plate Neuron | Motion and edge detection | gustatory | Gustatory Neuron | Taste processing |

| ALON | Antennal Lobe Olfactory Neuron | Olfactory cue processing | MBIN | Mushroom Body Input Neuron | Learning circuit modulation |

| thermosensory | Thermosensory Neuron | Temperature sensing | clock | Clock Neuron | Circadian rhythm control |

| LOP>ME | Lobula Plate to Medulla | Motion-sensitive feedback | TPN | Transmedullary Projection Neuron | Optic lobes to brain |

| Type | Neuron Classes |

|---|---|

| Input | olfactory, visual, mechanosensory, hygrosensory, thermosensory, gustatory, ocellar, unknown sensory |

| Intermediate | CX, ALPN, LO, bilateral, ME, ME>LOP, ME>LO, LO>LOP, ME>LA, LA>ME, ME>LO.LOP, ALLN, LOP>ME.LO, LOP>LO.ME, LA, AN, ALIN, mAL, LHLN, ME.LO, ME.LO.LOP, LO>ME, optic lobes, ME.LOP, TPN |

| Output | MBON, DAN, LHCENT, clock, pars intercerebralis, pars lateralis, Kenyon Cell, ALON, LOP>ME, LOP>LO.ME, LOP>LO, LOP, TuBu |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).