Submitted:

14 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Clinical Diagnosis of AD

Progress in Diagnostic Technologies for AD

| Methodology | Biomarker | Advantages | Limitations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunoassay from Biological Fluids | ||||

| CSF | Aβ42, t-tau and p-tau, NfL | Widely used in several systematic studies | Requires the presence of cognitive decline that impacts daily activities for the diagnosis of AD | [5] |

| Plasma | Aβ42 and Aβ40, p-tau181, p-tau217, p-tau231, NfL, GFAP | High diagnostic accuracy for identifying AD compared to standard clinical evaluation | More research is needed | [66,67] |

| Serum | Aβ, tau, NfL, miRNA | Ability to accurately diagnose early stages of AD and identify individuals at high risk of cognitive decline in older adults | Diagnosis is based on clinical and pathological criteria | [68] |

| Neuroimaging | ||||

| CT | Brain atrophy and vascular changes | This method also identifies other causes of neurodegeneration | While offering ease of access, there may be less accuracy in the results | [69] |

| PET | Cerebral metabolism involving glycolysis or Aβ protein deposition | Identifies lower glycolysis uptake in medial temporal regions and the cingulum | High cost | [70] |

| MRI | Cerebral atrophy and ventricular dilation | Better visualization of atrophy in the entorhinal cortex, middle temporal lobe, and hippocampus | High cost | [69] |

| MRS | Measures different metabolites: NAA, mI, Chol, Glu, Gln, and GABA | Provides metabolic information that may aid in understanding AD | Difficult access and high cost of use | [71] |

| DTI | Description of white matter microstructure through its tensor model | Identifies potential biomarkers in the early stages of AD | Limitations regarding interpretation | [72] |

| FW | Isolates and quantifies changes in extracellular water | Detects subtle changes in brain tissue that may indicate early stages of DA | Introduces an additional layer of complexity in the analysis and interpretation of data | [73] |

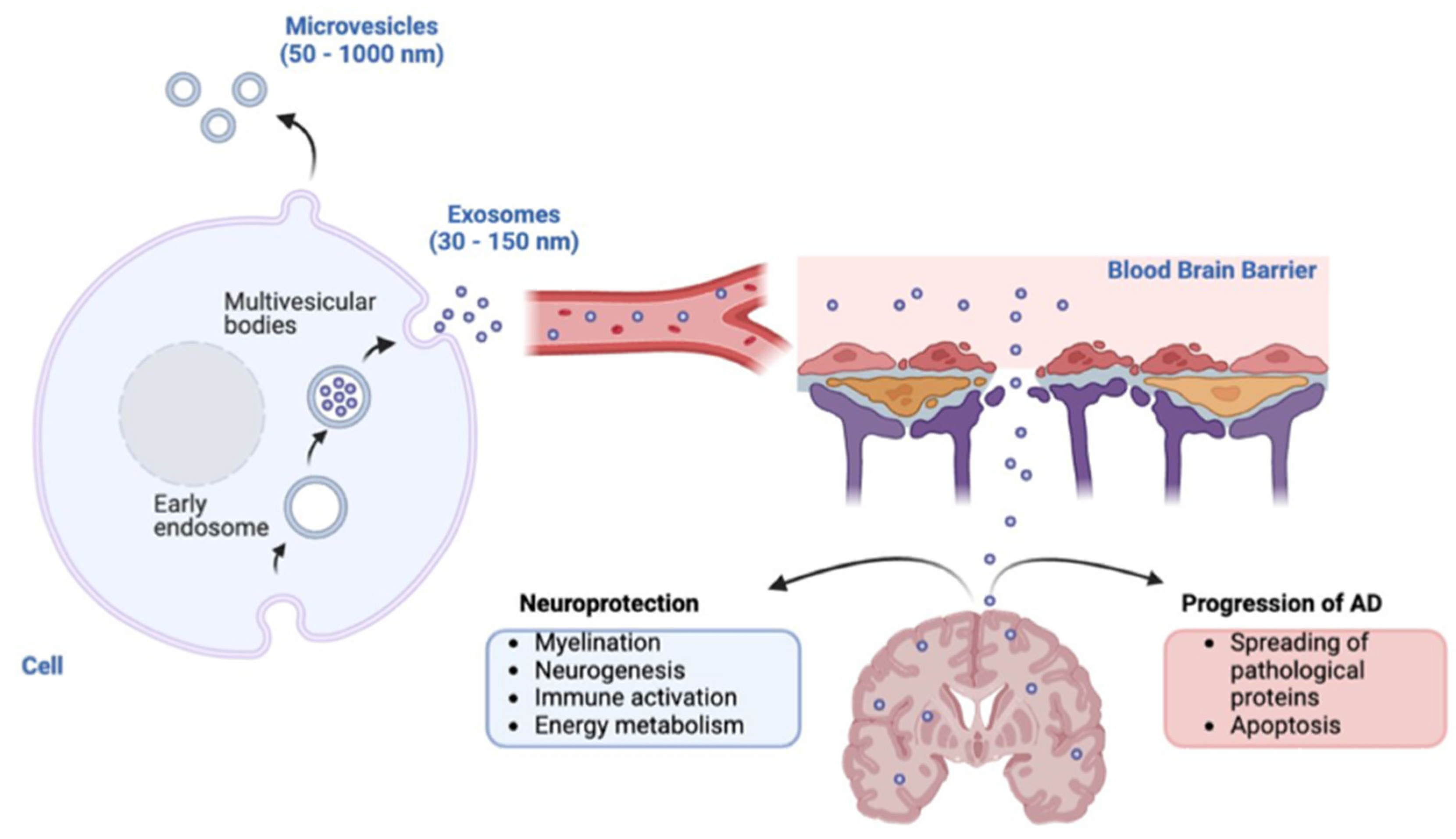

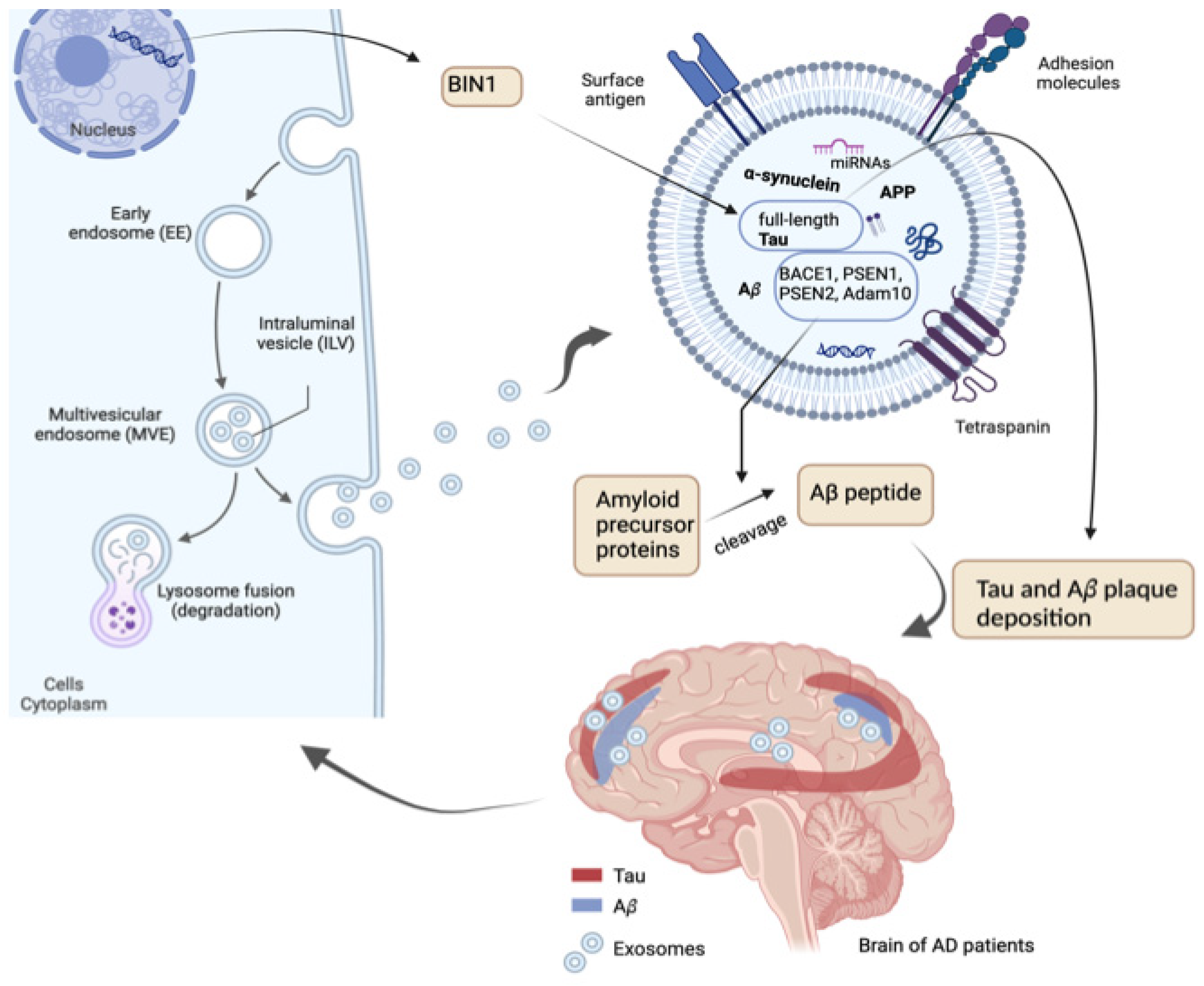

Exosomal Proteins

Exosomal microRNAs

Exosomal Circular RNAs

Exosomal miRNAs as Potential Biomarkers for AD Diagnosis

| EV samples | miRNA's | Biomarkers Characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | let-7g; miR126-3p; miR142-3p; miR146a; mir223-3p; mir26b | Low level in severe AD (SAD). KEGG pathway analysis - The analysis revealed 43 KEGG pathways associated with the most significant miRNAs, with a focus on p53, toll-like receptors, MAPK, NF-kappa B, AD, apoptosis, and PI3K-Akt. Increase of endothelial EVs. Elevated levels of EVs expressing the axonal glycoprotein CD171. Increase of inflammatory cytokines and reduction of over 50% growth factors, compared to EVs of HC. SAD score and miRNA expression presented correlation (let-7g r = 0.5223, miR126-3p r = 0.4564, miR142-3p r = 0.4675, miR146a r = 0.5433, mir223-3p r = 0.4779). |

[146] |

| CSF, serum and plasma | miR-193b | Low level in CSF, serum and plasma of AD, and serum and plasma of MCI. Potential target of the 3' UTR of APP. Negative correlation between levels of miR-193b and Aβ42 in the CSF of patients with DAT (r =−0.442), and control group (r =−0.503). |

[147] |

| Plasma | miR-342-3p | Differential expression in AD group and correlated with other miRNAs decreased in AD. | [148] |

| miR-185-5p, hsa-miR-20a-5p, and hsa-miR-497-5p | Related to AD and education level. | ||

| Plasma | hsa-miR-185-5p, hsa-miR-181c-5p, hsa-miR-451a, and hsa-miR-664a-3p | Decreased hsa-miR-185-5p in AD improves the expression of PSEN1 and GSK3β, which further increases Aβ generation. The 3′ UTR of hsa-miR-181c-5p contains a predicted binding site for IL1. In AD patients, IL1 is associated with Aβ generation. hsa-miR-451a correlated with clinical measurements of education (R = 0.477), depression (R = 0.605), and leisure activity (R = 0.411). hsa-miR-664a-3p was upregulated in AD patients, which downregulated CREB1 and BDNF expression levels, thereby leading to a cognitive decline in AD patients. |

[149] |

| Serum | miR-223 | Decreased in patients with dementia. miR-223 level correlated with Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores, Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scores, magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) spectral ratios and serum concentrations of IL-1b, IL-6, TNF-α, and CRP. | [150] |

| miR-223 downregulated in the dementia group compared to the control group. Differential expression of miR-223 between AD and Vascular Dementia (VaD) groups. Higher miR-223 levels in AD patients under medical care than those at their first clinical visit. Levels of miR-223 in the blood of dementia patients have a positive correlation with the scores on the MMSE and CDR scales (r = 0.365 and 0.4598, respectively). miR-223 levels in patients with dementia present positive correlation with the scores on the MMSE and CDR scales (r = 0.365 and 0.4598, respectively). Levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and PCR elevated in patients with dementia. Higher in AD compared to VaD. A correlation was found between the levels of miR-223 and the concentrations of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and PCR (r = -0.5504, -0.4549, -0.5152, -0.4977, respectively). miR-223 present AUC of 0.875 (95% CI: 0.7779–0.9721). |

|||

| Plasma | miR-16-5p, miR-19b-3p, miR-25-3p, miR-30b-5p, miR-92a-3p and miR-451a | Validation analysis confirmed significant upregulation of miR-16-5p, miR-25-3p, miR-92a-3p, and miR-451a in prodromal AD patients, suggesting these dysregulated miRNAs are involved in the early progression of AD. Group of AD patients presented positive correlations between Aβ42 and miR-30b-5p (r = 0.67) and between h-tau and miR-223-3p (r = 0.62). |

[151] |

| Plasma | hsa-miR-451a e hsa-miR-21-5p hsa-miR-23a-3p, hsa-miR-126-3p, hsa-let-7i-5p e hsa-miR-151a-3p |

Down-regulated in AD samples respect to dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) patients. Decreased in AD respect to controls. |

[152] |

| Cortical gray matter | miR-132 and miR-212 | Levels of miR-132 separated controls from AD-MCI with an AUC of 0.58 (95% CI: 0.38–0.78) and controls from AD dementia with an AUC of 0.77 (95% CI: 0.61–0.93). miR-212 showed better discrimination than miR-132 between AD-MCI and controls, and AD and controls. miR-212 levels separated controls from AD-MCI with an AUC of 0.68 (95% CI: 0.5–0.86) and controls from AD dementia with an AUC of 0.84 (95% CI: 0.72–0.96). miR-212 achieved a sensitivity of 92.2% (95% CI: 68.5–99.6%) and a specificity of 69.0% (95% CI: 50.8–82.7%). | [140] |

| Plasma | miR-502-5p miR-483-5p |

AUC is 0.872, sensitivity 79.2 % and specificity 83.3 %. Area Under the Curve (AUC) is 0.901, sensitivity 79.2 % and specificity 100 %. |

[153] |

| Serum | hsa-miR-125b-1-3p, hsa-miR-193a-5p, hsa-miR-378a-3p, hsa-miR-378i and hsa-miR-451 | hsa-miR-125b-1-3p has an AUC of 0.765 in the AD group compared to the healthy group. Sensitivity (82.1) and specificity (67.7%). | [126,154,155] |

| CSF | miR-455–3p | Elevated levels in AD patients compared to controls (AUC = 0.745). | [156] |

| Plasma (NCAM/ABCA1 dual-labeled exosomal Aβ42/40) | miR-384 | The AUC of NCAM/ABCA1 dual-labeled exosomal Aβ42/40 for diagnosis of SCD was higher than that of Aβ42, T-tau, and P-T181-tau; the AUC of NCAM/ABCA1 dual-labeled exosomal miR-384 for diagnosis of SCD was higher than that of Aβ42, Aβ42/40, T-tau, P-T181-tau, and NfL. miR-384 can downregulate the expression and activity of BACE. |

[157] |

| Plasma (Neurons: EVL1CAM) | miR-29a-5p, miR-125b-5p, and miR-210-3p | MCI, MCI-AD, and AD dementia (AUC = 0.948). | [158] |

| miR-210-3p and miR-132-5p | MCI (AUC = 0.941). | ||

| miR-106-5p |

AD dementia (AUC = 1.000). |

||

| miR-106b-5p |

Negative correlation with cortical thickness in regions prone to age-related dementias as imaged in MRI. | ||

|

Plasma (Astrocytes: sEVGLAST) |

miR-107 |

MCI, MCI-AD, and AD dementia (AUCs = 0.964); AD dementia (AUC = 1.000). |

|

| miR-107 and miR 132-5p | Negative correlation with the cortical thickness. | ||

| and miR-210-3p | MCI (AUCs = 0.941). | ||

| miR-29a-5p and miR-106-5p | Overall cognitive impairment (AUC = 0.925). | ||

|

Plasma (Microglia: sEVTMEM119) |

miR-29a-5p |

MCI (AUC = 0.840). |

|

| miR-132-5p and miR-125b-5p | AD dementia (AUC = 1.000). | ||

| miR-106b-5p and miR-132-5p | Negative correlation with the temporal cortical thickness. | ||

| Plasma (Oligodendrocytes: sEVPDGFRα) | miR-29a-5p | AD dementia (AUC = 1.000). Negative correlation with temporal cortical thickness. | |

| Plasma (Pericytes: sEVPDGFRβ) | miR-9-5p | Overall cognitive impairment (AUC = 0.935), MCI (AUC = 0.931), and AD (AUC = 1.000). | |

| Plasma (Endothelial cells: sEVCD31) | miR-132-5p | Overall impairment and MCI, and prediction of AD (AUC = 1.000). | |

| miR-210-3p | Negative correlation with cortical thickness. | ||

| Plasma (Pericytes: sEVPDGFRβ and Endothelial cells: sEVCD31) | miR-9-5p (sEVPDGFRβ) and miR-132-5p (sEVCD31) | Overall cognitive impairment (AUC = 1.000). | |

| miR-132-5p (sEVCD31) and miR-135b-5p (sEVPDGFRβ) | MCI and AD. |

Concluding Remarks and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knopman, D.S.; Amieva, H.; Petersen, R.C.; Chételat, G.; Holtzman, D.M.; Hyman, B.T.; et al. Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nichols, E.; Steinmetz, J.D.; Vollset, S.E.; Fukutaki, K.; Chalek, J.; Abd-Allah, F.; et al. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 2022, 7, e105–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grøntvedt, G.R.; Schröder, T.N.; Sando, S.B.; White, L.; Bråthen, G.; Doeller, C.F. Alzheimer’s disease. Current Biology. 2018, 28, R645–R649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madnani, R.S. Alzheimer’s disease: a mini-review for the clinician. Front Neurol. 2023, 14, 1178588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B.; Villain, N.; Frisoni, G.B.; Rabinovici, G.D.; Sabbagh, M.; Cappa, S.; et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations of the International Working Group. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 484–496. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, N.; Ren, Y.; Yamazaki, Y.; Qiao, W.; Li, F.; Felton, L.M.; et al. Alzheimer’s Risk Factors Age, APOE Genotype, and Sex Drive Distinct Molecular Pathways. Neuron. 2020, 106, 727–742e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.B. A Brief History of the Progress in Our Understanding of Genetics and Lifestyle, Especially Diet, in the Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2024, 100, S165–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordestgaard, L.T.; Christoffersen, M.; Frikke-Schmidt, R. Shared Risk Factors between Dementia and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 9777. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Tan, L.; Wang, H.F.; Jiang, T.; Tan, M.S.; Tan, L.; et al. Meta-analysis of modifiable risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015, 86, 1299–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Q.; Tan, L.; Wang, H.F.; Tan, M.S.; Tan, L.; Xu, W.; et al. Risk factors for predicting progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016, 87, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenaza-Urquijo, E.M.; Vemuri, P. Resistance vs resilience to Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2018, 90, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunkle, B.W.; Grenier-Boley, B.; Sims, R.; Bis, J.C.; Damotte, V.; Naj, A.C.; et al. Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Aβ, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nat Genet. 2019, 51, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monsell, S.E.; Mock, C.; Fardo, D.W.; Bertelsen, S.; Cairns, N.J.; Roe, C.M.; et al. Genetic Comparison of Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Persons With Alzheimer Disease Neuropathology. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2017, 31, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prpar Mihevc, S.; Majdič, G. Canine Cognitive Dysfunction and Alzheimer’s Disease – Two Facets of the Same Disease? Front Neurosci. 2019, 13, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panek, W.K.; Murdoch, D.M.; Gruen, M.E.; Mowat, F.M.; Marek, R.D.; Olby, N.J. Plasma Amyloid Beta Concentrations in Aged and Cognitively Impaired Pet Dogs. Mol Neurobiol. 2021, 58, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiandaca, M.S.; Kapogiannis, D.; Mapstone, M.; Boxer, A.; Eitan, E.; Schwartz, J.B.; et al. Identification of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease by a profile of pathogenic proteins in neurally derived blood exosomes: A case-control study. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2015, 11, 600. [Google Scholar]

- Kapogiannis, D.; Mustapic, M.; Shardell, M.D.; Berkowitz, S.T.; Diehl, T.C.; Spangler, R.D.; et al. Association of Extracellular Vesicle Biomarkers With Alzheimer Disease in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. JAMA Neurol. 2019, 76, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.A.; Younes, S.N.; Raza, S.S.; Zarif, L.; Nisar, S.; Ahmed, I.; et al. Role of non-coding RNA networks in leukemia progression, metastasis and drug resistance. Mol Cancer. 2020, 19, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares Martins, T.; Trindade, D.; Vaz, M.; Campelo, I.; Almeida, M.; Trigo, G.; et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic potential of exosomes in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2021, 156, 162–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetzl, E.J.; Kapogiannis, D.; Schwartz, J.B.; Lobach, I.V.; Goetzl, L.; Abner, E.L.; et al. Decreased synaptic proteins in neuronal exosomes of frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. The FASEB Journal. 2016, 30, 4141–4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetzl, E.J.; Schwartz, J.B.; Abner, E.L.; Jicha, G.A.; Kapogiannis, D. High complement levels in astrocyte-derived exosomes of Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2018, 83, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winston, C.N.; Goetzl, E.J.; Schwartz, J.B.; Elahi, F.M.; Rissman, R.A. Complement protein levels in plasma astrocyte-derived exosomes are abnormal in conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring. 2019, 11, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Winston, C.N.; Goetzl, E.J.; Akers, J.C.; Carter, B.S.; Rockenstein, E.M.; Galasko, D.; et al. Prediction of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to dementia with neuronally derived blood exosome protein profile. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring. 2016, 3, 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Jjiao Yang, G.; Yan Qqing Zhao, J.; Li, S. Exosome-encapsulated microRNAs as promising biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Rev Neurosci. 2019, 31, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yuan, T.; Tschannen, M.; Sun, Z.; Jacob, H.; Du, M.; et al. Characterization of human plasma-derived exosomal RNAs by deep sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2013, 14, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Balkom, B.W.M.; Eisele, A.S.; Michiel Pegtel, D.; Bervoets, S.; Verhaar, M.C. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of small RNAs in human endothelial cells and exosomes provides insights into localized RNA processing, degradation and sorting. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015, 4, 26760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, M.A.; Ludwig, R.G.; Garcia-Martin, R.; Brandão, B.B.; Kahn, C.R. Extracellular miRNAs: From Biomarkers to Mediators of Physiology and Disease. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 656–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Li, L.; Li, M.; Guo, C.; Yao, J.; et al. Exosome and Exosomal MicroRNA: Trafficking, Sorting, and Function. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2015, 13, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shobeiri, P.; Alilou, S.; Jaberinezhad, M.; Zare, F.; Karimi, N.; Maleki, S.; et al. Circulating long non-coding RNAs as novel diagnostic biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease (AD): A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2023, 18, e0281784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Cheng, X.; Su, X.; Wu, L.; Cai, Q.; Wu, H. Treponema denticola Induces Alzheimer-Like Tau Hyperphosphorylation by Activating Hippocampal Neuroinflammation in Mice. J Dent Res. 2022, 101, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graff-Radford, J.; Yong, K.X.X.; Apostolova, L.G.; Bouwman, F.H.; Carrillo, M.; Dickerson, B.C.; et al. New insights into atypical Alzheimer’s disease in the era of biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phochantachinda, S.; Chatchaisak, D.; Temviriyanukul, P.; Chansawang, A.; Pitchakarn, P.; Chantong, B. Ethanolic Fruit Extract of Emblica officinalis Suppresses Neuroinflammation in Microglia and Promotes Neurite Outgrowth in Neuro2a Cells. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2021, 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, D.; Wildman, D.E. Extracellular Vesicles and the Promise of Continuous Liquid Biopsies. J Pathol Transl Med. 2018, 52, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanninen, K.M.; Bister, N.; Koistinaho, J.; Malm, T. Exosomes as new diagnostic tools in CNS diseases. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 2016, 1862, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolova, L. Early-Stage Alzheimer Primer. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021, 82, 32781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eramudugolla, R.; Mortby, M.E.; Sachdev, P.; Meslin, C.; Kumar, R.; Anstey, K.J. Evaluation of a research diagnostic algorithm for DSM-5 neurocognitive disorders in a population-based cohort of older adults. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachdev, P.S.; Blacker, D.; Blazer, D.G.; Ganguli, M.; Jeste, D.V.; Paulsen, J.S.; et al. Classifying neurocognitive disorders: the DSM-5 approach. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014, 10, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thal, D.R.; Capetillo-Zarate, E.; Del Tredici, K.; Braak, H. The Development of Amyloid β Protein Deposits in the Aged Brain. Science of Aging Knowledge Environment. 2006, 2006, re1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, B.T.; Phelps, C.H.; Beach, T.G.; Bigio, E.H.; Cairns, N.J.; Carrillo, M.C.; et al. National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2012, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Montine, T.J.; Phelps, C.H.; Beach, T.G.; Bigio, E.H.; Cairns, N.J.; Dickson, D.W.; et al. National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012, 123, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejo-Lopez, J.A.; Yachnis, A.T.; Prokop, S. Neuropathology of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurotherapeutics. 2022, 19, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeTure, M.A.; Dickson, D.W. The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2019, 14, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Braak, H.; Thal, D.R.; Ghebremedhin, E.; Del Tredici, K. Stages of the pathologic process in alzheimer disease: Age categories from 1 to 100 years. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2011, 70, 960–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schilling, L.P.; Balthazar, M.L.F.; Radanovic, M.; Forlenza, O.V.; Silagi, M.L.; Smid, J.; et al. Diagnóstico da doença de Alzheimer: recomendações do Departamento Científico de Neurologia Cognitiva e do Envelhecimento da Academia Brasileira de Neurologia. Dement Neuropsychol. 2022, 16 (Suppl. 1), 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murden, R.A. The Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. In 1990. p. 59–64.

- Parker, T.D.; Slattery, C.F.; Zhang, J.; Nicholas, J.M.; Paterson, R.W.; Foulkes, A.J.M.; et al. Cortical microstructure in young onset Alzheimer’s disease using neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging. Hum Brain Mapp. 2018, 39, 3005–3017. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Pozo, A.; Frosch, M.P.; Masliah, E.; Hyman, B.T. Neuropathological Alterations in Alzheimer Disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2011, 1, a006189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alafuzoff, I.; Libard, S. Ageing-Related Neurodegeneration and Cognitive Decline. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, P.A.; Yu, L.; Leurgans, S.E.; Wilson, R.S.; Brookmeyer, R.; Schneider, J.A.; et al. Attributable risk of Alzheimer’s dementia attributed to age-related neuropathologies. Ann Neurol. 2019, 85, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, L.R.; Corrada, M.M.; Kawas, C.H.; Cholerton, B.A.; Edland, S.E.; Flanagan, M.E.; et al. Neuropathologic Changes of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias: Relevance to Future Prevention. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2023, 95, 307–316. [Google Scholar]

- Jack, C.R.; Andrews, J.S.; Beach, T.G.; Buracchio, T.; Dunn, B.; Graf, A.; et al. Revised criteria for diagnosis and staging of Alzheimer’s disease: Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2024, 20, 5143–5169. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, B.; Villain, N.; Schneider, L.; Fox, N.; Campbell, N.; Galasko, D.; et al. Alzheimer Disease as a Clinical-Biological Construct—An International Working Group Recommendation. JAMA Neurol. 2024, 81, 1304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jack, C.R.; Andrews, J.S.; Beach, T.G.; Buracchio, T.; Dunn, B.; Graf, A.; et al. Revised criteria for diagnosis and staging of Alzheimer’s disease: Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2024, 20, 5143–5169. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, M.C.; O’Philibin, L.; Foley, T.; Dolan, C.; Kennelly, S.; O’Dowd, S.; et al. The Use of Biomarkers in Diagnosing Alzheimer’s Disease: Recommendations of the Irish Working Group on Biological Approaches to the Diagnosis of Dementia. Ir Med J. 2024, 117, 1062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Studart Neto, A.; Barbosa, B.J.A.P.; Coutinho, A.M.; Souza, L.C.; de Schilling, L.P.; da Silva, M.N.M.; et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers in clinical practice in Brazil: recommendations from the Scientific Department of Cognitive Neurology and Aging of the Brazilian Academy of Neurology. Dement Neuropsychol. 2024, 18, e2024C001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Okazawa, H.; Nogami, M.; Ishida, S.; Makino, A.; Mori, T.; Kiyono, Y.; et al. PET/MRI multimodality imaging to evaluate changes in glymphatic system function and biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 12310. [Google Scholar]

- Jack, C.R. Advances in Alzheimer’s disease research over the past two decades. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 866–869. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, N.J.; Janelidze, S.; Al Khleifat, A.; Leuzy, A.; van der Ende, E.L.; Karikari, T.K.; et al. A multicentre validation study of the diagnostic value of plasma neurofilament light. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 3400. [Google Scholar]

- Benedet, A.L.; Milà-Alomà, M.; Vrillon, A.; Ashton, N.J.; Pascoal, T.A.; Lussier, F.; et al. Differences Between Plasma and Cerebrospinal Fluid Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein Levels Across the Alzheimer Disease Continuum. JAMA Neurol. 2021, 78, 1471. [Google Scholar]

- Hampel, H.; Hardy, J.; Blennow, K.; Chen, C.; Perry, G.; Kim, S.H.; et al. The Amyloid-β Pathway in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2021, 26, 5481–5503. [Google Scholar]

- Schindler, S.E.; Bollinger, J.G.; Ovod, V.; Mawuenyega, K.G.; Li, Y.; Gordon, B.A.; et al. High-precision plasma β-amyloid 42/40 predicts current and future brain amyloidosis. Neurology. 2019, 93, e1647–e1659. [Google Scholar]

- Karikari, T.K.; Ashton, N.J.; Brinkmalm, G.; Brum, W.S.; Benedet, A.L.; Montoliu-Gaya, L.; et al. Blood phospho-tau in Alzheimer disease: analysis, interpretation, and clinical utility. Nat Rev Neurol. 2022, 18, 400–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, N.J.; Puig-Pijoan, A.; Milà-Alomà, M.; Fernández-Lebrero, A.; García-Escobar, G.; González-Ortiz, F.; et al. Plasma and CSF biomarkers in a memory clinic: Head-to-head comparison of phosphorylated tau immunoassays. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2023, 19, 1913–1924. [Google Scholar]

- Mielke, M.M.; Aakre, J.A.; Algeciras-Schimnich, A.; Proctor, N.K.; Machulda, M.M.; Eichenlaub, U.; et al. Comparison of CSF phosphorylated tau 181 and 217 for cognitive decline. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2022, 18, 602–611. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, J.; Ning, Y.; Chen, M.; Wang, S.; Yang, H.; Li, F.; et al. Biomarker Changes during 20 Years Preceding Alzheimer’s Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2024, 390, 712–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmqvist, S.; Tideman, P.; Mattsson-Carlgren, N.; Schindler, S.E.; Smith, R.; Ossenkoppele, R.; et al. Blood Biomarkers to Detect Alzheimer Disease in Primary Care and Secondary Care. JAMA. 2024, 332, 1245. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, N.J.; Brum, W.S.; Di Molfetta, G.; Benedet, A.L.; Arslan, B.; Jonaitis, E.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of a Plasma Phosphorylated Tau 217 Immunoassay for Alzheimer Disease Pathology. JAMA Neurol. 2024, 81, 255. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Farvadi, F.; Hashemi, F.; Amini, A.; Vakilinezhad, M.A.; Raee, M.J. Early Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease with Blood Test; Tempting but Challenging. Int J Mol Cell Med. 2023, 12, 172. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Liu, K.Y.; Costafreda, S.G.; Selbæk, G.; Alladi, S.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. The Lancet. 2024, 404, 572–628. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, E.C.; Cross, D.J.; Galasko, D.; Schellenberg, G.D.; Raskind, M.A.; Peskind, E.R.; et al. Preclinical Evidence of Alzheimer Changes. Arch Neurol. 2009, 66, 632–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh-Bahaei, N.; Chen, M.; Pappas, I. Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS) in Alzheimer’s Disease. In 2024. p. 115–42.

- Chen, X.; Firulyova, M.; Manis, M.; Herz, J.; Smirnov, I.; Aladyeva, E.; et al. Microglia-mediated T cell infiltration drives neurodegeneration in tauopathy. Nature. 2023, 615, 668–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamagata, K.; Andica, C.; Takabayashi, K.; Saito, Y.; Taoka, T.; Nozaki, H.; et al. Associação de índices de ressonância magnética do sistema glinfático com deposição amiloide e cognição em comprometimento cognitivo leve e doença de Alzheimer. Neurology. 2022, 2648–2660. [Google Scholar]

- Brum, W.S.; Cullen, N.C.; Janelidze, S.; Ashton, N.J.; Zimmer, E.R.; Therriault, J.; et al. A two-step workflow based on plasma p-tau217 to screen for amyloid β positivity with further confirmatory testing only in uncertain cases. Nat Aging. 2023, 3, 1079–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colmant, L.; Boyer, E.; Gerard, T.; Sleegers, K.; Lhommel, R.; Ivanoiu, A.; et al. Definition of a Threshold for the Plasma Aβ42/Aβ40 Ratio Measured by Single-Molecule Array to Predict the Amyloid Status of Individuals without Dementia. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.L.; Tuo, Q.Z.; Lei, P. An Introduction to Ultrasensitive Assays for Plasma Tau Detection. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2021, 80, 1353–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, Y.T.; Rocchi, L.; Hammond, P.; Hardy, C.J.D.; Warren, J.D.; Ridha, B.H.; et al. Effect of donepezil on transcranial magnetic stimulation parameters in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. 2018, 4, 103–107. [Google Scholar]

- Kamagata, K.; Andica, C.; Hatano, T.; Ogawa, T.; Takeshige-Amano, H.; Ogaki, K.; et al. Advanced diffusion magnetic resonance imaging in patients with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Neural Regen Res. 2020, 15, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabarestani, S.; Eslami, M.; Cabrerizo, M.; Curiel, R.E.; Barreto, A.; Rishe, N.; et al. A Tensorized Multitask Deep Learning Network for Progression Prediction of Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 810873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Thibeau-Sutre, E.; Diaz-Melo, M.; Samper-González, J.; Routier, A.; Bottani, S.; et al. Convolutional neural networks for classification of Alzheimer’s disease: Overview and reproducible evaluation. Med Image Anal. 2020, 63, 101694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischof, G.N.; Bartenstein, P.; Barthel, H.; van Berckel, B.; Doré, V.; van Eimeren, T.; et al. Toward a Universal Readout for 18 F-Labeled Amyloid Tracers: The CAPTAINs Study. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2021, 62, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, L.; Chiaravalloti, A.; Bagni, O.; Schillaci, O. 18F-labeled radiopharmaceuticals for the molecular neuroimaging of amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018, 8, 268–281. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, C.C.; Pejoska, S.; Mulligan, R.S.; Jones, G.; Chan, J.G.; Svensson, S.; et al. Head-to-Head Comparison of 11 C-PiB and 18 F-AZD4694 (NAV4694) for β-Amyloid Imaging in Aging and Dementia. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2013, 54, 880–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murugan, N.A.; Chiotis, K.; Rodriguez-Vieitez, E.; Lemoine, L.; Ågren, H.; Nordberg, A. Cross-interaction of tau PET tracers with monoamine oxidase B: evidence from in silico modelling and in vivo imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019, 46, 1369–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, C.; Villeneuve, S.; Smith, R.; Hansson, O.; Ossenkoppele, R. Tau PET Imaging in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2022, 63 (Supplement 1), 20S–26S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klunk, W.E.; Engler, H.; Nordberg, A.; Wang, Y.; Blomqvist, G.; Holt, D.P.; et al. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann Neurol. 2004, 55, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Arteaga, J.; Chen, G.; Gangadharmath, U.; Gomez, L.F.; Kasi, D.; et al. [18F]T807, a novel tau positron emission tomography imaging agent for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2013, 9, 666–676. [Google Scholar]

- Jack, C.R.; Knopman, D.S.; Jagust, W.J.; Shaw, L.M.; Aisen, P.S.; Weiner, M.W.; et al. Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological cascade. Lancet Neurol. 2010, 9, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittens, M.M.J.; Allemeersch, G.J.; Sima, D.M.; Naeyaert, M.; Vanderhasselt, T.; Vanbinst, A.M.; et al. Inter- and Intra-Scanner Variability of Automated Brain Volumetry on Three Magnetic Resonance Imaging Systems in Alzheimer’s Disease and Controls. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 746982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Firulyova, M.; Manis, M.; Herz, J.; Smirnov, I.; Aladyeva, E.; et al. Microglia-mediated T cell infiltration drives neurodegeneration in tauopathy. Nature. 2023, 615, 668–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maillard, P.; Hillmer, L.J.; Lu, H.; Arfanakis, K.; Gold, B.T.; Bauer, C.E.; et al. MRI free water as a biomarker for cognitive performance: Validation in the MarkVCID consortium. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring. 2022, 14, e12362. [Google Scholar]

- Sathe, A.; Yang, Y.; Schilling, K.G.; Shashikumar, N.; Moore, E.; Dumitrescu, L.; et al. Free-water: A promising structural biomarker for cognitive decline in aging and mild cognitive impairment. Imaging Neuroscience. 2024, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, E.; Hallikainen, I.; Hänninen, T.; Tohka, J. Rey’s Auditory Verbal Learning Test scores can be predicted from whole brain MRI in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage Clin. 2017, 13, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology , function , and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367, eaau6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciferri, M.C.; Quarto, R.; Tasso, R. Extracellular Vesicles as Biomarkers and Therapeutic Tools: From Pre-Clinical to Clinical Applications. Biology 2021, 10, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroya-Beltri, C.; Baixauli, F.; Mittelbrunn, M.; Fernández-Delgado, I.; Torralba, D.; Moreno-Gonzalo, O.; et al. ISGylation controls exosome secretion by promoting lysosomal degradation of MVB proteins. Nat Commun. 2016, 7, 13588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krämer-Albers, E.; Bretz, N.; Tenzer, S.; Winterstein, C.; Möbius, W.; Berger, H.; et al. Oligodendrocytes secrete exosomes containing major myelin and stress-protective proteins: Trophic support for axons? Proteomics Clin Appl. 2007, 1, 1446–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frühbeis, C.; Fröhlich, D.; Kuo, W.P.; Amphornrat, J.; Thilemann, S.; Saab, A.S.; et al. Neurotransmitter-Triggered Transfer of Exosomes Mediates Oligodendrocyte–Neuron Communication. PLoS Biol. 2013, 11, e1001604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drago, F.; Lombardi, M.; Prada, I.; Gabrielli, M.; Joshi, P.; Cojoc, D.; et al. ATP Modifies the Proteome of Extracellular Vesicles Released by Microglia and Influences Their Action on Astrocytes. Front Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Lee, H.; Zhu, Z.; Minhas, J.K.; Jin, Y. Enrichment of selective miRNAs in exosomes and delivery of exosomal miRNAs in vitro and in vivo. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2017, 312, L110–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migneault, F.; Dieudé, M.; Turgeon, J.; Beillevaire, D.; Hardy, M.P.; Brodeur, A.; et al. Apoptotic exosome-like vesicles regulate endothelial gene expression, inflammatory signaling, and function through the NF-κB signaling pathway. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 12562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Valbuena, I.; Visanji, N.P.; Kim, A.; Lau, H.H.C.; So, R.W.L.; Alshimemeri, S.; et al. Alpha-synuclein seeding shows a wide heterogeneity in multiple system atrophy. Transl Neurodegener. 2022, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Su, Y.; Sharma, M.; Singh, S.; Kim, S.; Peavey, J.J.; et al. MicroRNA expression in extracellular vesicles as a novel blood-based biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2023, 19, 4952–4966. [Google Scholar]

- Crotti, A.; Sait, H.R.; McAvoy, K.M.; Estrada, K.; Ergun, A.; Szak, S.; et al. BIN1 favors the spreading of Tau via extracellular vesicles. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 9477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guix, F.; Corbett, G.; Cha, D.; Mustapic, M.; Liu, W.; Mengel, D.; et al. Detection of Aggregation-Competent Tau in Neuron-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. Int J Mol Sci. 2018, 19, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellingham, S.A.; Guo, B.B.; Coleman, B.M.; Hill, A.F. Exosomes: Vehicles for the Transfer of Toxic Proteins Associated with Neurodegenerative Diseases? Front Physiol. 2012, 3, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitan, E.; Hutchison, E.R.; Marosi, K.; Comotto, J.; Mustapic, M.; Nigam, S.M.; et al. Extracellular vesicle-associated Aβ mediates trans-neuronal bioenergetic and Ca2+-handling deficits in Alzheimer’s disease models. NPJ Aging Mech Dis. 2016, 2, 16019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajendran, L.; Honsho, M.; Zahn, T.R.; Keller, P.; Geiger, K.D.; Verkade, P.; et al. Alzheimer’s disease β-amyloid peptides are released in association with exosomes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006, 103, 11172–11177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frühbeis, C.; Fröhlich, D.; Kuo, W.P.; Amphornrat, J.; Thilemann, S.; Saab, A.S.; et al. Neurotransmitter-Triggered Transfer of Exosomes Mediates Oligodendrocyte–Neuron Communication. PLoS Biol. 2013, 11, e1001604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkins, M.B.; Dasgupta, S.; Wang, G.; Zhu, G.; Bieberich, E. Exosome reduction in vivo is associated with lower amyloid plaque load in the 5XFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2014, 35, 1792–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Dinkins, M.; He, Q.; Zhu, G.; Poirier, C.; Campbell, A.; et al. Astrocytes Secrete Exosomes Enriched with Proapoptotic Ceramide and Prostate Apoptosis Response 4 (PAR-4). Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012, 287, 21384–21395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fire, A.; Xu, S.; Montgomery, M.K.; Kostas, S.A.; Driver, S.E.; Mello, C.C. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998, 391, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titze-de-Almeida, R.; David, C.; Titze-de-Almeida, S.S. The Race of 10 Synthetic RNAi-Based Drugs to the Pharmaceutical Market. Pharm Res. 2017, 34, 1339–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takousis, P.; Sadlon, A.; Schulz, J.; Wohlers, I.; Dobricic, V.; Middleton, L.; et al. Differential expression of microRNAs in Alzheimer’s disease brain, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2019, 15, 1468–1477. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Y.J.; Wong, B.Y.X.; Vaidyanathan, R.; Sreejith, S.; Chia, S.Y.; Kandiah, N.; et al. Altered Cerebrospinal Fluid Exosomal microRNA Levels in Young-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease and Frontotemporal Dementia. J Alzheimers Dis Rep. 2021, 5, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Bao, C.; Li, S.; Guo, W.; Zhao, J.; et al. Circular RNA is enriched and stable in exosomes: a promising biomarker for cancer diagnosis. Cell Res. 2015, 25, 981–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanhäusser, B.; Busse, D.; Li, N.; Dittmar, G.; Schuchhardt, J.; Wolf, J.; et al. Global quantification of mammalian gene expression control. Nature. 2011, 473, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeck, W.R.; Sorrentino, J.A.; Wang, K.; Slevin, M.K.; Burd, C.E.; Liu, J.; et al. Circular RNAs are abundant, conserved, and associated with ALU repeats. RNA. 2013, 19, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, L.S.; Andersen, M.S.; Stagsted, L.V.W.; Ebbesen, K.K.; Hansen, T.B.; Kjems, J. The biogenesis, biology and characterization of circular RNAs. Nat Rev Genet. 2019, 20, 675–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titze-de-Almeida, S.S.; Titze-de-Almeida, R. Progress in circRNA-Targeted Therapy in Experimental Parkinson’s Disease. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, R.; Reis, F.C.G.; Ying, W.; Olefsky, J.M. Exosomes as mediators of intercellular crosstalk in metabolism. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 1744–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Zhao, F. Comprehensive identification of internal structure and alternative splicing events in circular RNAs. Nat Commun. 2016, 7, 12060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, R.; Reis, F.C.G.; Ying, W.; Olefsky, J.M. Exosomes as mediators of intercellular crosstalk in metabolism. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 1744–1762. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ulshöfer, C.J.; Pfafenrot, C.; Bindereif, A.; Schneider, T. Methods to study circRNA-protein interactions. Methods. 2021, 196, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aufiero, S.; van den Hoogenhof, M.M.G.; Reckman, Y.J.; Beqqali, A.; van der Made, I.; Kluin, J.; et al. Cardiac circRNAs arise mainly from constitutive exons rather than alternatively spliced exons. RNA. 2018, 24, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jin, Z.; Liu, C.; Yu, X.; et al. Circular RNAs in Parkinson’s Disease: Reliable Biological Markers and Targets for Rehabilitation. Mol Neurobiol. 2023, 60, 3261–3276. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Preußer, C.; Hung, L.; Schneider, T.; Schreiner, S.; Hardt, M.; Moebus, A.; et al. Selective release of circRNAs in platelet-derived extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2018, 7, 1424473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.F.; Li, W.J.; Hu, K.S.; Gao, J.; Zhai, W.L.; Yang, J.H.; et al. Exosome biogenesis: machinery, regulation, and therapeutic implications in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2022, 21, 207. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, T.B.; Jensen, T.I.; Clausen, B.H.; Bramsen, J.B.; Finsen, B.; Damgaard, C.K.; et al. Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature. 2013, 495, 384–388. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Yan, P.; Liang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhou, S.; et al. Circular RNA expression is suppressed by androgen receptor (AR)-regulated adenosine deaminase that acts on RNA (ADAR1) in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e3171–e3171. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Deng, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Qing, H. G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs) in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Focus on BACE1 Related GPCRs. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Zheng, Q.; Liang, L.; Zhou, L. Serum Exosomal miRNA-125b and miRNA-451a are Potential Diagnostic Biomarker for Alzheimer’s Diseases. Degener Neurol Neuromuscul Dis. 2024, 14, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gámez-Valero, A.; Campdelacreu, J.; Vilas, D.; Ispierto, L.; Reñé, R.; Álvarez, R.; et al. Exploratory study on microRNA profiles from plasma-derived extracellular vesicles in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Transl Neurodegener. 2019, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aharon, A.; Spector, P.; Ahmad, R.S.; Horrany, N.; Sabbach, A.; Brenner, B.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles of Alzheimer’s Disease Patients as a Biomarker for Disease Progression. Mol Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 4156–4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.F.; Wei, L.; Duan, Z.Q.; Zhang, Z.L.; Chen, T.Y.; Lu, J.G.; et al. Contribution of IL-1β, 6 and TNF-α to the form of post-traumatic osteoarthritis induced by “idealized” anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in a porcine model. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018, 65, 212–220. [Google Scholar]

- Visconte, C.; Fenoglio, C.; Serpente, M.; Muti, P.; Sacconi, A.; Rigoni, M.; et al. Altered Extracellular Vesicle miRNA Profile in Prodromal Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 14749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Wang, L. Inflamma-MicroRNAs in Alzheimer’s Disease: From Disease Pathogenesis to Therapeutic Potentials. Front Cell Neurosci. 2021, 15, 785433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, T.; Jin, F.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, J.; Tang, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. MicroRNA-126-3p attenuates blood-brain barrier disruption, cerebral edema and neuronal injury following intracerebral hemorrhage by regulating PIK3R2 and Akt. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017, 494, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chum, P.P.; Bishara, M.A.; Solis, S.R.; Behringer, E.J. Cerebrovascular miRNAs Track Early Development of Alzheimer’s Disease and Target Molecular Markers of Angiogenesis and Blood Flow Regulation. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2024, 99, S187–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, D.J.; Mengel, D.; Mustapic, M.; Liu, W.; Selkoe, D.J.; Kapogiannis, D.; et al. miR-212 and miR-132 Are Downregulated in Neurally Derived Plasma Exosomes of Alzheimer’s Patients. Front Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugli, G.; Cohen, A.M.; Bennett, D.A.; Shah, R.C.; Fields, C.J.; Hernandez, A.G.; et al. Plasma Exosomal miRNAs in Persons with and without Alzheimer Disease: Altered Expression and Prospects for Biomarkers. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0139233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.Y.; Hernandez-Rapp, J.; Jolivette, F.; Lecours, C.; Bisht, K.; Goupil, C.; et al. miR-132/212 deficiency impairs tau metabolism and promotes pathological aggregation in vivo. Hum Mol Genet. 2015, 24, 6721–6735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogswell, J.P.; Ward, J.; Taylor, I.A.; Waters, M.; Shi, Y.; Cannon, B.; et al. Identification of miRNA Changes in Alzheimer’s Disease Brain and CSF Yields Putative Biomarkers and Insights into Disease Pathways. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2008, 14, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhen, H.; Sun, Y.; Rong, S.; Li, B.; Song, Z.; et al. Plasma Exo-miRNAs Correlated with AD-Related Factors of Chinese Individuals Involved in Aβ Accumulation and Cognition Decline. Mol Neurobiol. 2022, 59, 6790–6804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, M.; Hu, Y.; Lan, T.; Guan, K.L.; Luo, T.; Luo, M. The Hippo signalling pathway and its implications in human health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharon, A.; Spector, P.; Ahmad, R.S.; Horrany, N.; Sabbach, A.; Brenner, B.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles of Alzheimer’s Disease Patients as a Biomarker for Disease Progression. Mol Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 4156–4169. [Google Scholar]

- LIUCG; SONGJ; ZHANGYQ; WANGPC MicroRNA-193b is a regulator of amyloid precursor protein in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid derived exosomal microRNA-193b is a biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Med Rep. 2014, 10, 2395–2400. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugli, G.; Cohen, A.M.; Bennett, D.A.; Shah, R.C.; Fields, C.J.; Hernandez, A.G.; et al. Plasma Exosomal miRNAs in Persons with and without Alzheimer Disease: Altered Expression and Prospects for Biomarkers. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0139233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhen, H.; Sun, Y.; Rong, S.; Li, B.; Song, Z.; et al. Plasma Exo-miRNAs Correlated with AD-Related Factors of Chinese Individuals Involved in Aβ Accumulation and Cognition Decline. Mol Neurobiol. 2022, 59, 6790–6804. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H.; Xu, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, Q.; Yang, M.; et al. Serum Exosomal miR-223 Serves as a Potential Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarker for Dementia. Neuroscience. 2018, 379, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visconte, C.; Fenoglio, C.; Serpente, M.; Muti, P.; Sacconi, A.; Rigoni, M.; et al. Altered Extracellular Vesicle miRNA Profile in Prodromal Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 14749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámez-Valero, A.; Campdelacreu, J.; Vilas, D.; Ispierto, L.; Reñé, R.; Álvarez, R.; et al. Exploratory study on microRNA profiles from plasma-derived extracellular vesicles in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Transl Neurodegener. 2019, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Li, N.; Pu, J.; Zhang, C.; Xu, K.; Wang, W.; et al. The plasma derived exosomal miRNA-483-5p/502-5p serve as potential MCI biomarkers in aging. Exp Gerontol. 2024, 186, 112355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, X.; Zheng, Q.; Liang, L.; Zhou, L. Serum Exosomal miRNA-125b and miRNA-451a are Potential Diagnostic Biomarker for Alzheimer’s Diseases. Degener Neurol Neuromuscul Dis. 2024, 14, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Doecke, J.D.; Sharples, R.A.; Villemagne, V.L.; Fowler, C.J.; Rembach, A.; et al. Prognostic serum miRNA biomarkers associated with Alzheimer’s disease shows concordance with neuropsychological and neuroimaging assessment. Mol Psychiatry. 2015, 20, 1188–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Reddy, P.H. Elevated levels of MicroRNA-455-3p in the cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer’s patients: A potential biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 2021, 1867, 166052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Meng, S.; Di, W.; Xia, M.; Dong, L.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Amyloid-β protein and MicroRNA-384 in NCAM-Labeled exosomes from peripheral blood are potential diagnostic markers for Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2022, 28, 1093–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Su, Y.; Sharma, M.; Singh, S.; Kim, S.; Peavey, J.J.; et al. MicroRNA expression in extracellular vesicles as a novel blood-based biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2023, 19, 4952–4966. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).