Submitted:

14 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of the Coating Material

2.2. Materials, Equipment for ESD and Deposition Conditions

2.3. Types of Research, Methodology of Measurements, Research Equipment

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Coating Characterization—Roughness and Thickness, Тoпoграфия и Structure

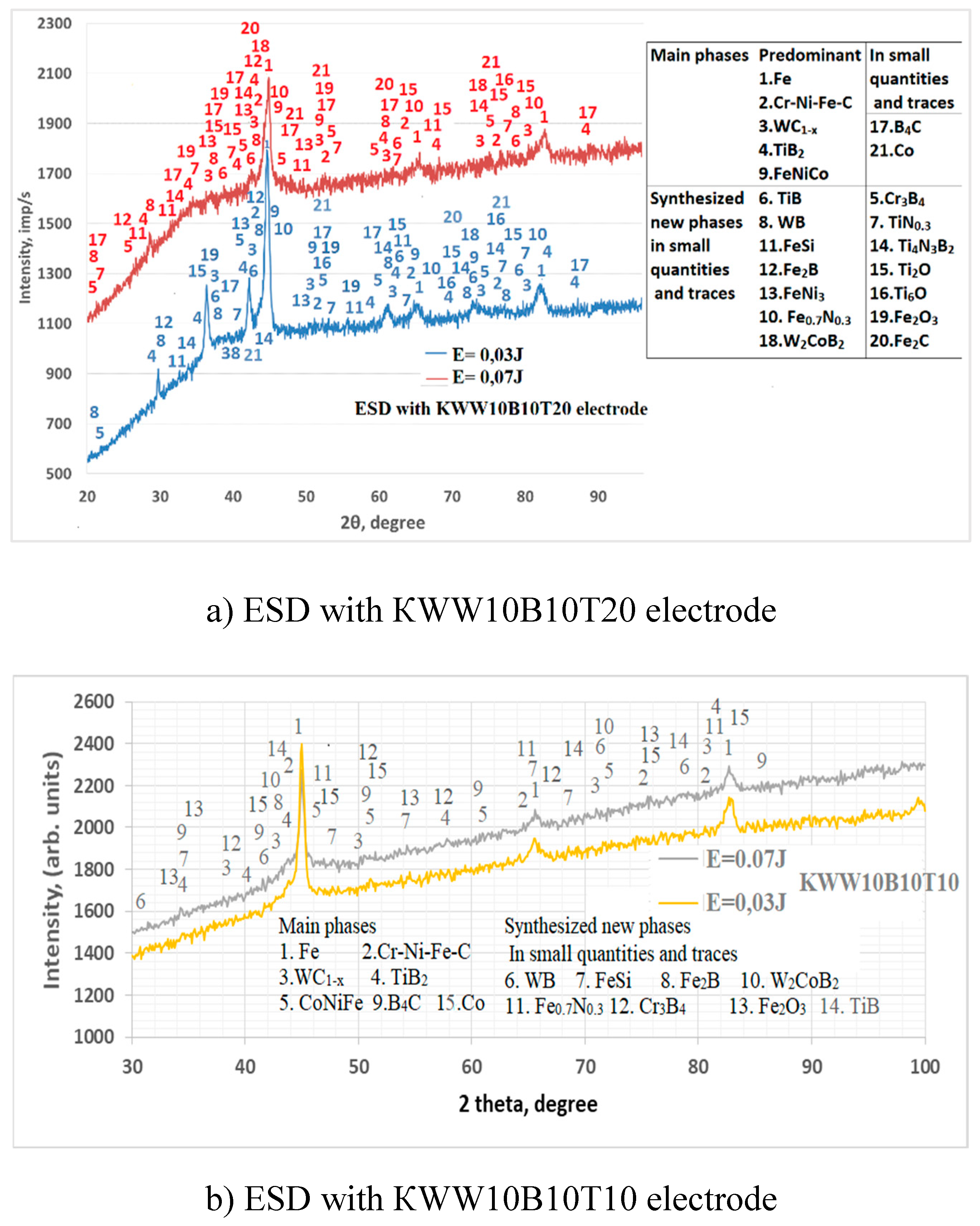

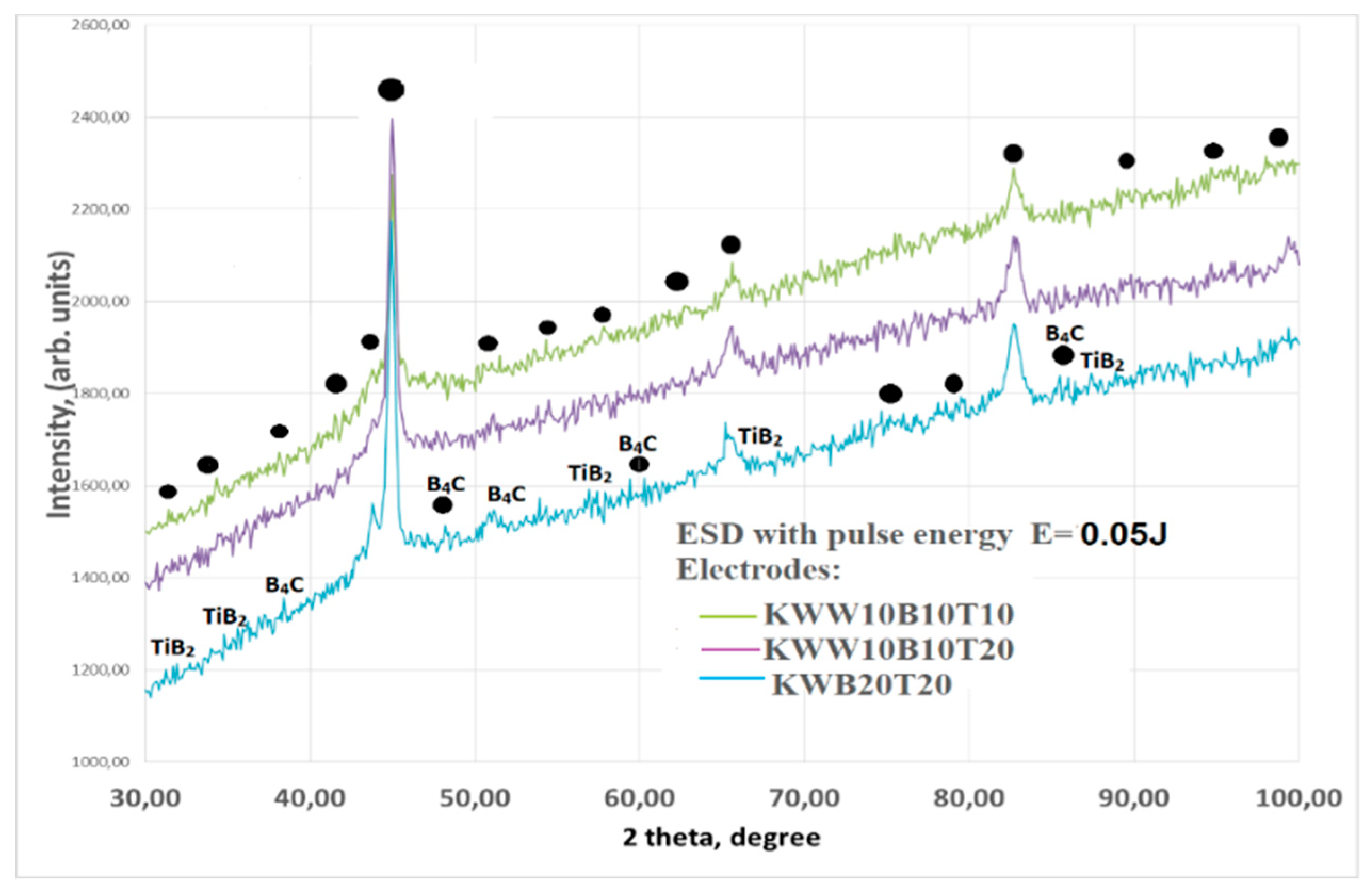

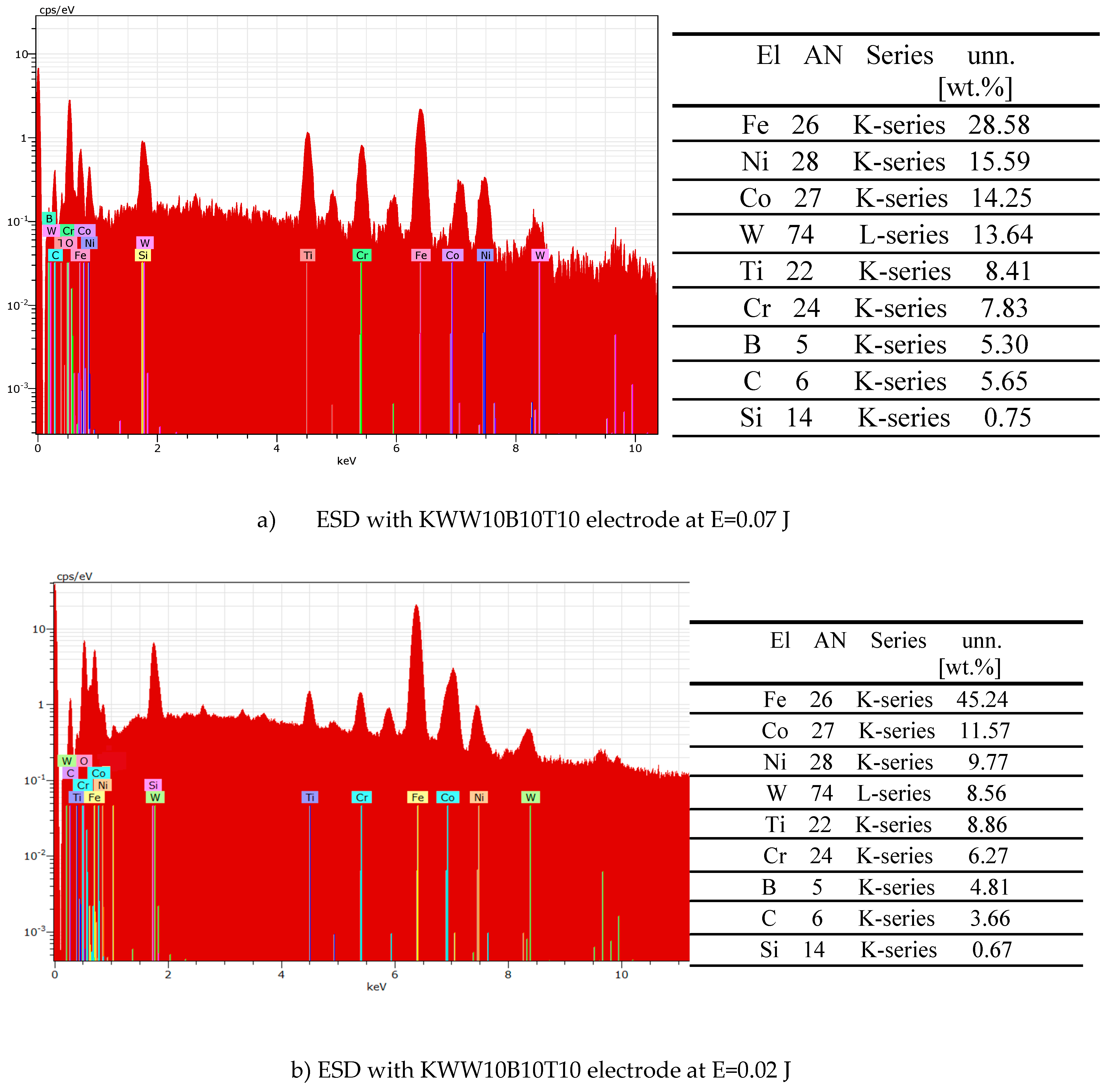

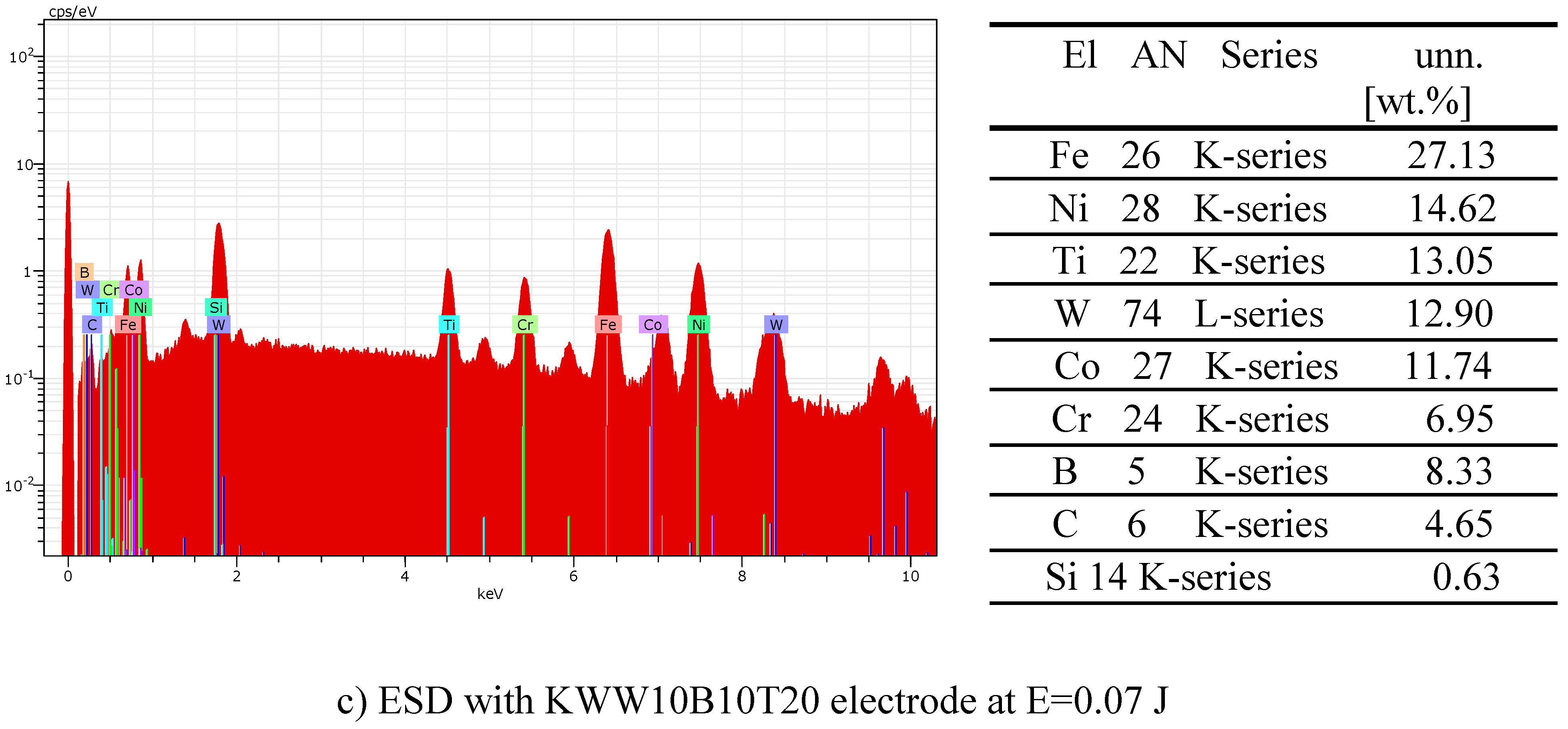

3.2. Phase Composition of Coatings

3.3. Tribological Tests

4. CONCLUSIONS

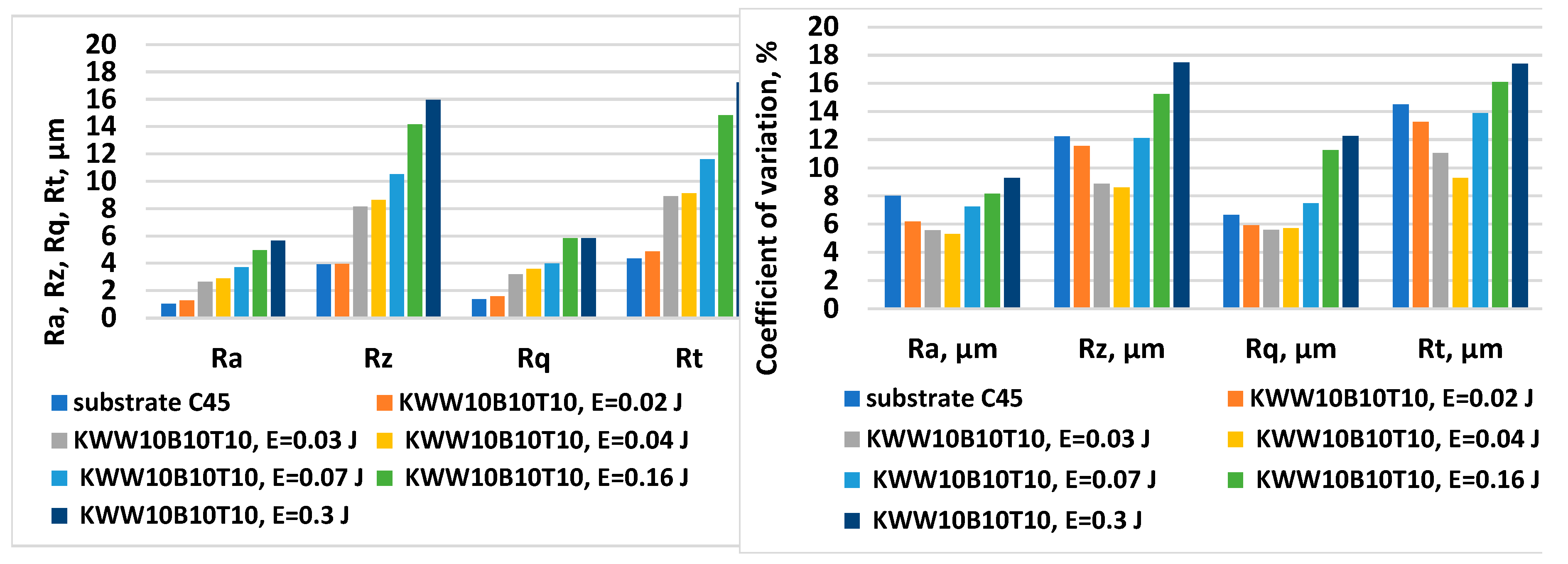

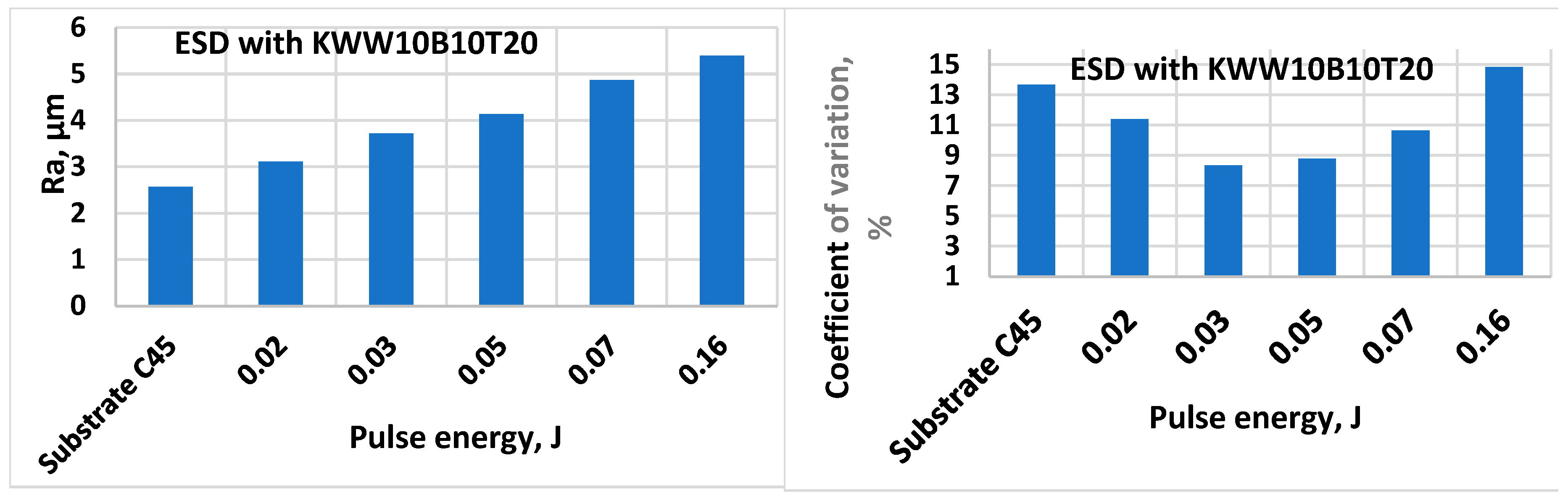

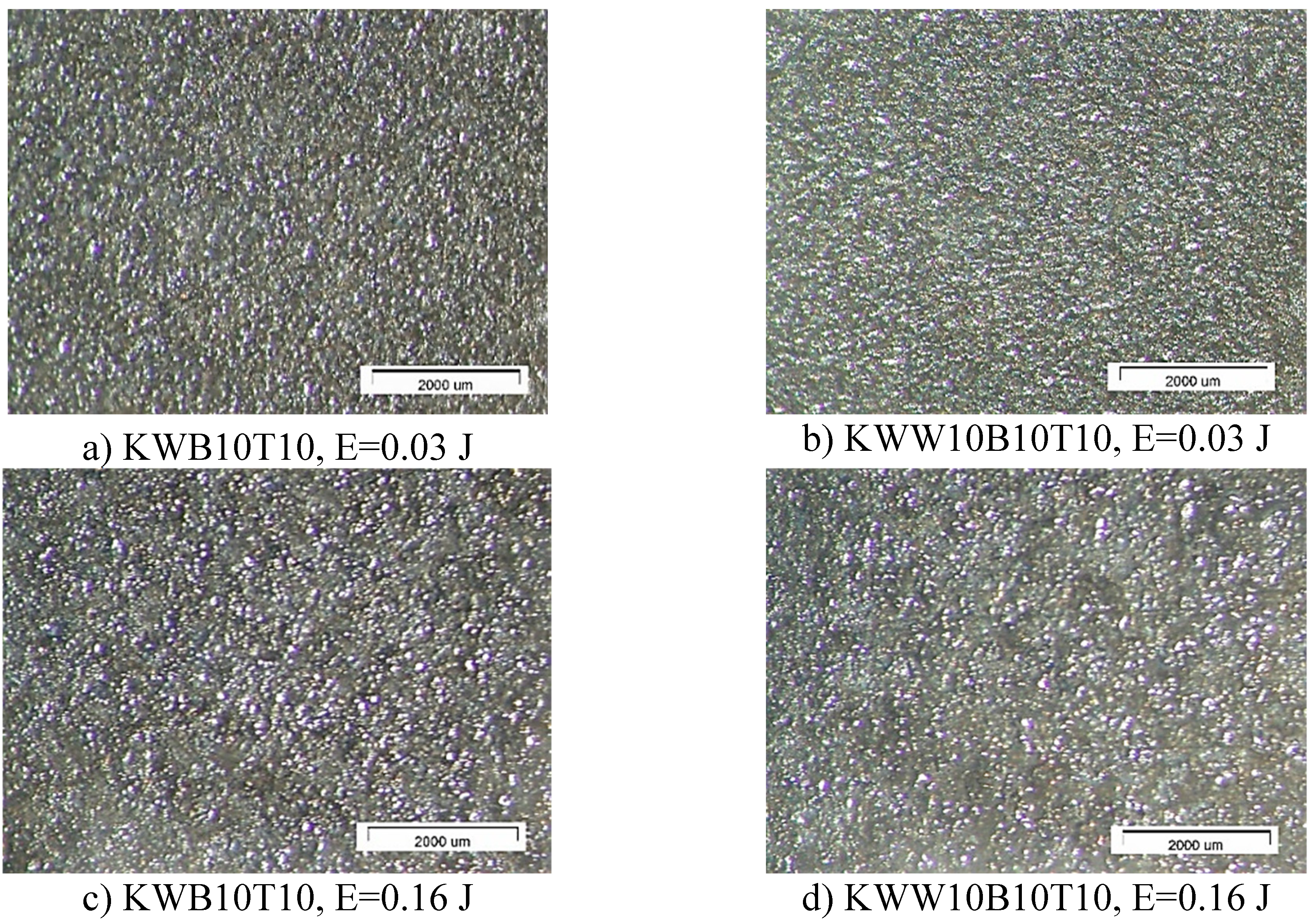

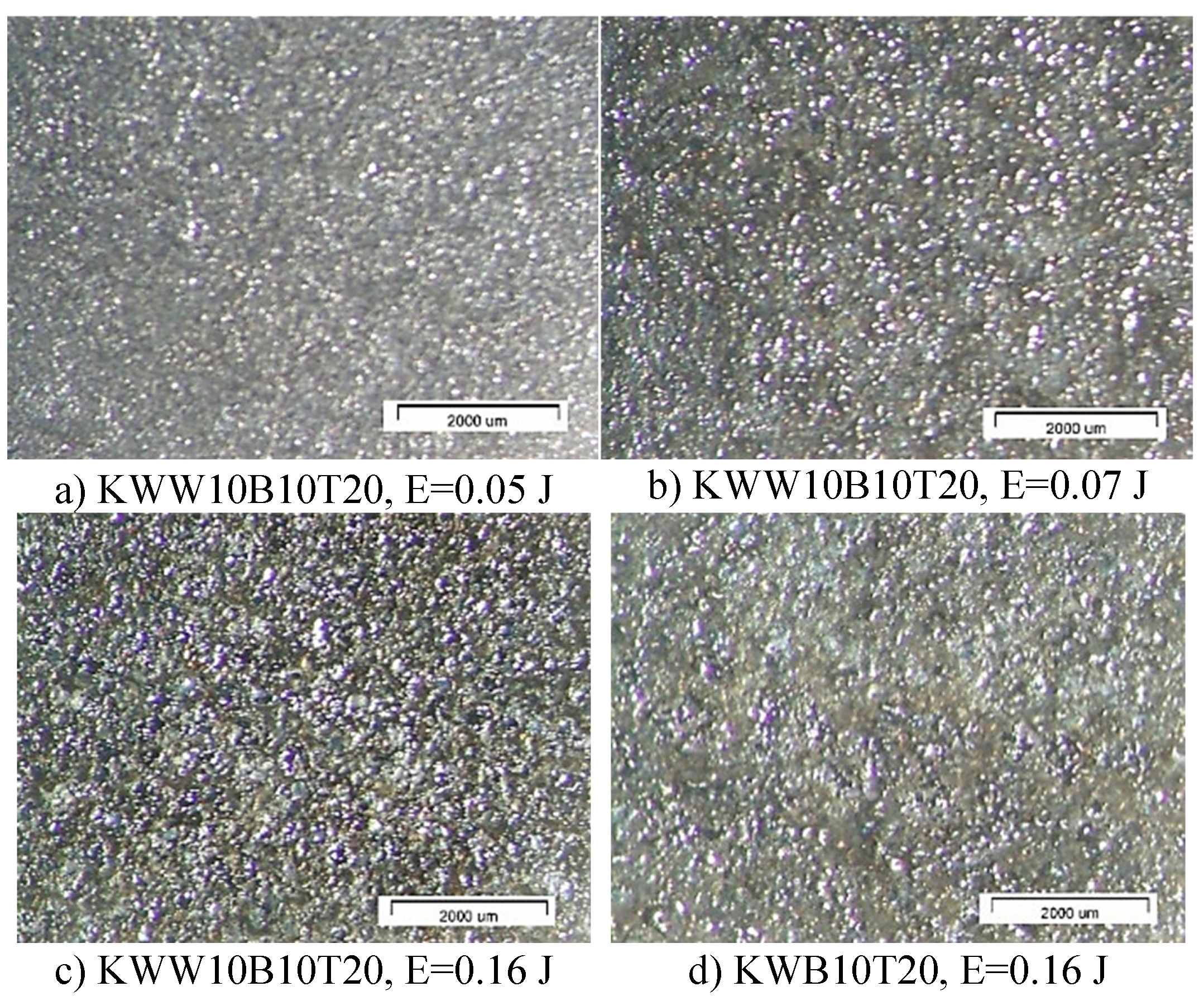

- 1. By ESD with multicomponent electrodes containing WC, Co-Ni-Cr-B-Si-Fe-C semi-self-fluxing alloys and additives of the superhard compounds B4C and TiB2 with different ratios between the individual components and using low-energy pulses, dense and uniform coatings with improved adhesion to the substrate, with crystalline-amorphous structures, with thickness, roughness and microhardness variable by ESD modes in the ranges δ=15÷70 µm Ra=1.5÷7 µm, and HV 8.5÷15.0 GPa, respectively, and improved physicochemical and tribological properties were obtained.

- 2. The increase in pulse energy leads to an increase in the roughness, thickness and microhardness of the obtained coatings, but their unevenness also increases significantly. At the same pulse energy, the roughness parameters and the thickness of the coatings are different for the different electrodes studied, and to a significant extent depend on the amount of the the binding metal mass.

- 3. The microhardness of the coatings is 3-5 times higher than that of the steel substrates, as the differences in the microhardness values of the coatings from different electrodes vary within the range of 1÷3.5 GPa. The highest microhardness is that of ESD with КWW10 B20T20 and КWW10B10T20 electrodes, whose composition is most enriched in high-hard phases, intermetallic compounds.

- 4. In addition to the phases from the deposition electrode, new highly resistant phases and compounds were also registered in the coatings, the amount of which increases with increasing energy.

- 5. Nano-sized crystalline-amorphous structures were found in the coatings, the largest amount of which was registered in the coatings from the electrodes КWT10B10, КWW10T10B10 and КWW10B10T20 and pulse energy E=0.03÷0.07J. Due to the specificity and complexity of the processes caused by spark-plasma discharges, it was established that complete amorphization of the applied coatings is not possible through ESD with the studied electrodes, but the ranges of pulse energy at which the amount of amorphous regions is maximum have been determined for each electrode.

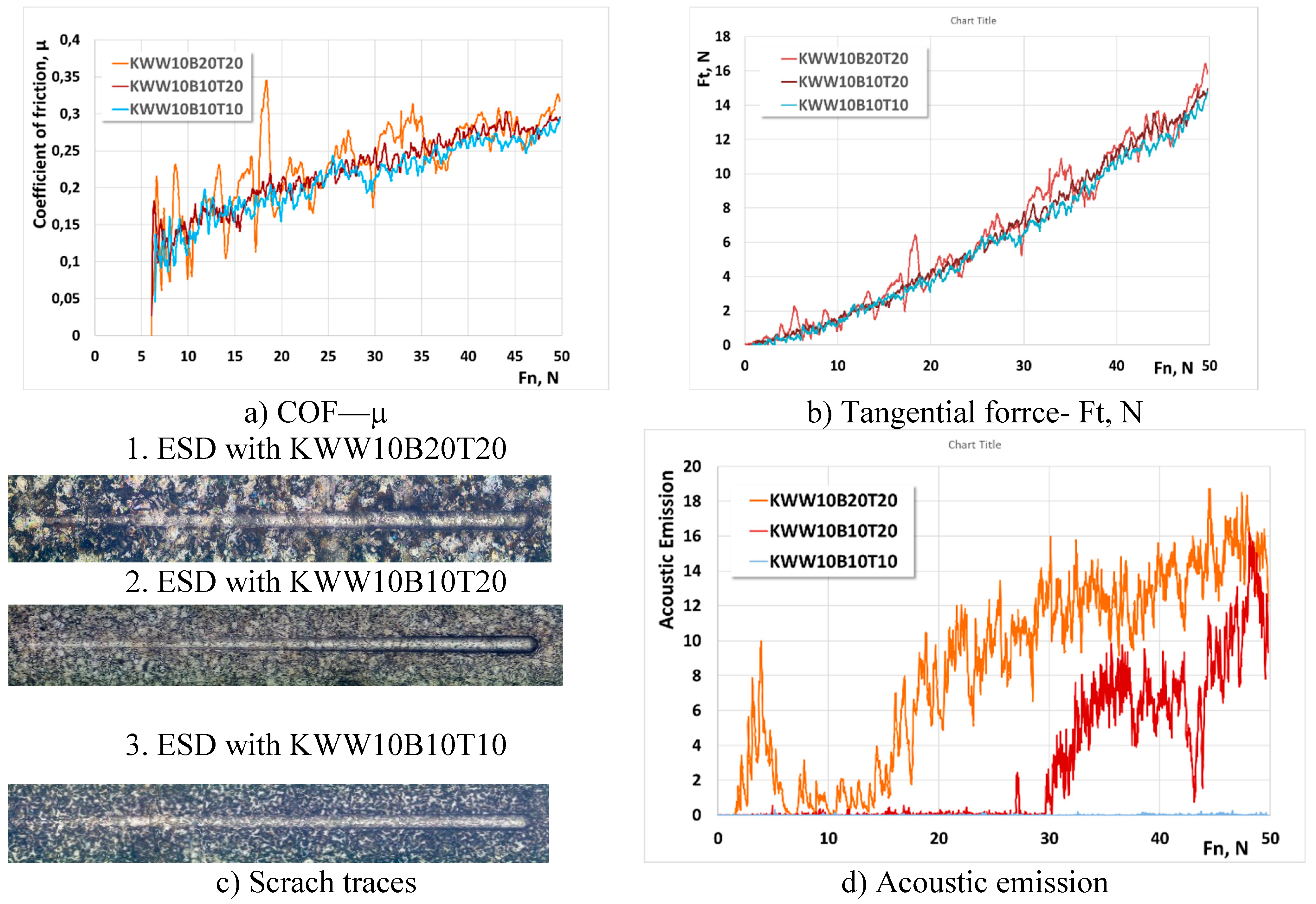

- 6. The values of COF, tangential force, acoustic emission and scratch test trace sizes of coatings from “KW” and “KWW” electrodes are 10-15 % lower than those of coatings from conventional carbide electrodes. The lowest values of COF, Ft and scratch test traces are shown by coatings from KWB10T10 and KWW10B10T10 electrodes applied at pulse energy up to 0.07 J, which do not show loss of cohesive strength at a load of up to 50 N, which is an indicator of very good plasticity, but lower hardness. The highest values are shown by coatings from KWW10B20T20 electrodes, which indicates higher brittleness, and the higher value of the acoustic signal is evidence of higher hardness of these coatings.

- 7. Semi-self-fluxing binding metals Ni-Cr-B-Si provide increased adhesion to the steel substrate and at the same time reduce oxidation processes during transfer, and also reduce the presence of microcracks. Highly wear-resistant components WC-TiB2-B4C and the presence of amorphous and nanoscale structures significantly increase wear resistance. The combination of materials with high hardness and wear resistance /carbides, borides, nitrides/ with lower-melting metals allows to obtain coatings with increased adhesion to the steel substrate, with high hardness and wear resistance, and at the same time high strength provided by the metal matrix.

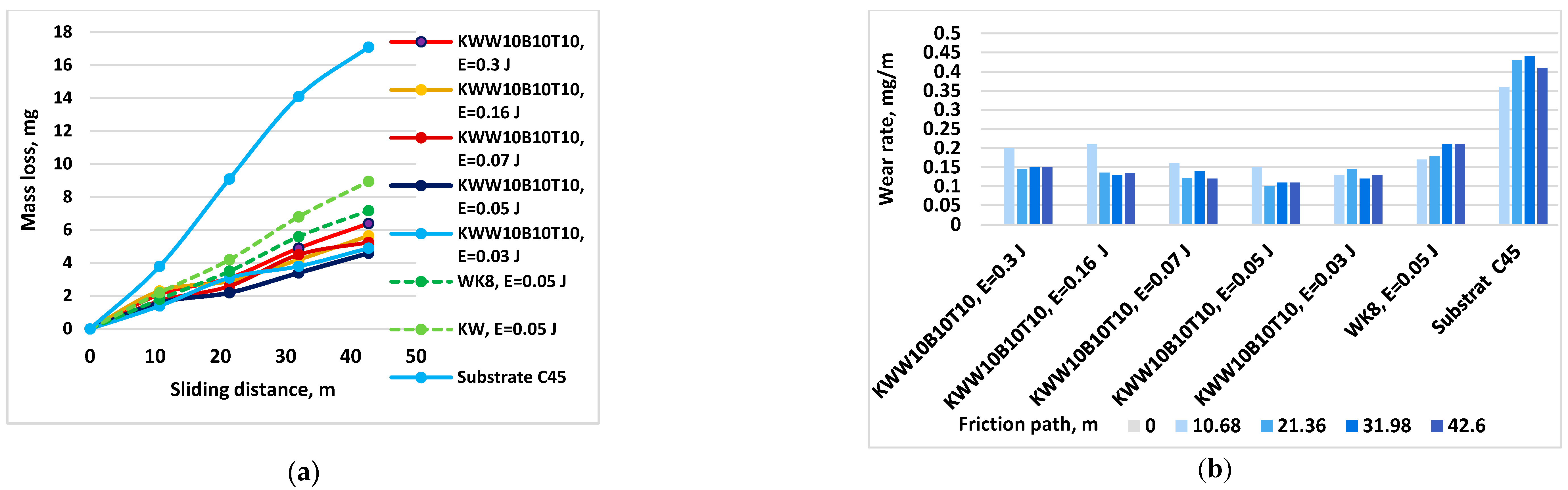

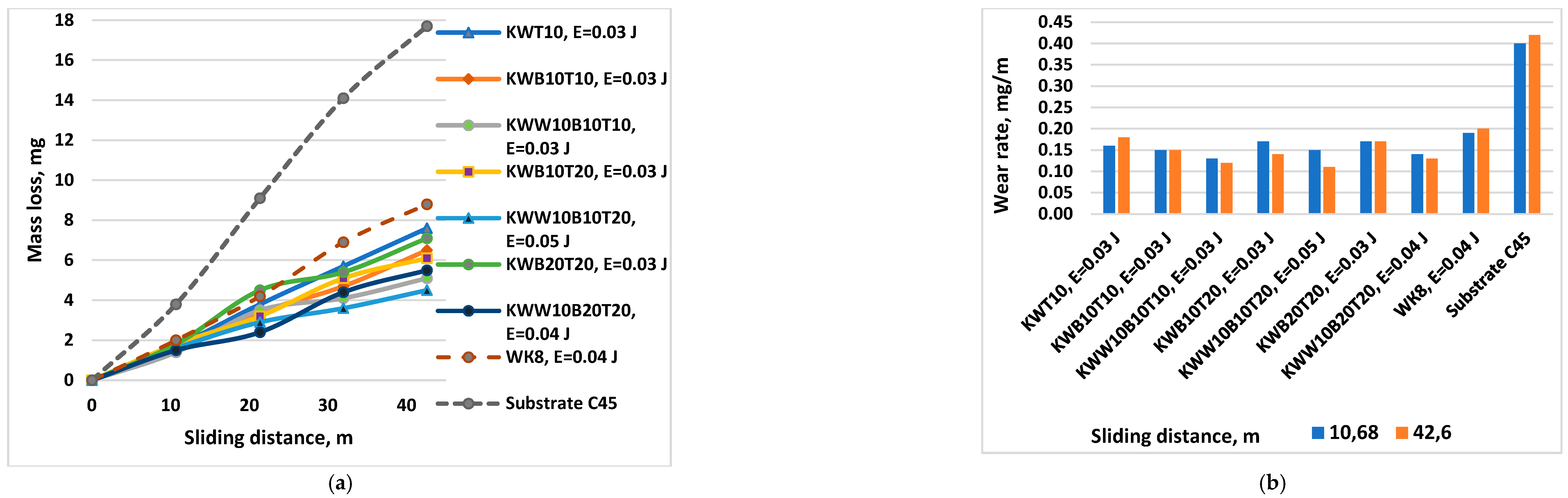

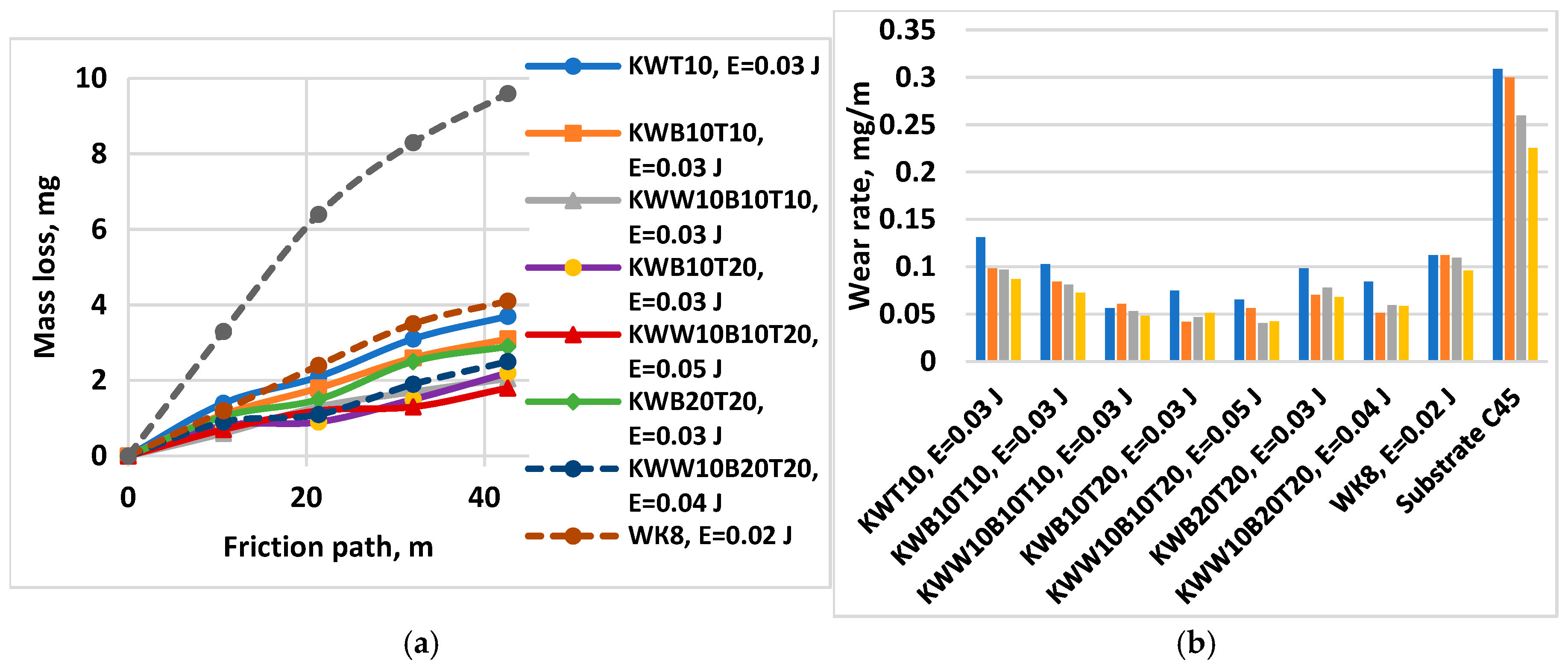

- 8. With increasing energy, the wear of the coatings decreases, reaching a minimum in the energy range 0.03-0.07 J. The samples coated with КWW10T10B20 and КWW10T10B10 have the lowest wear at both load values of 5 and 10 N. For each of the electrode compositions studied, the energy range at which the wear of the coatings is minimal and the limit values of the pulse energy, after exceeding which, the wear begins to increase, have been determined.

- 9. The amount of the binding metal mass from 20-40 % depending on the energy used affects to a varying extent the parameters and characteristics of the obtained coatings. Increasing the amount of the binding metal mass to 32-40 % (KW10B10T10, KWT10) expands the range of possible modes in which dense and uniform coatings are obtained, contributes to better adhesion of the coating to the base, allows the use of higher pulse energy (up to E=0.16 J) and the production of coatings with increased thickness, strength and toughness, a high amount of amorphous-like phases, acceptable roughness (Ra≈4-5 µm), but lower microhardness and wear resistance under friction.

- 10. The specified ratios between the individual components in the composition of the electrode material and the ESD conditions allow for maximum improvement of the properties and wear resistance of the coatings—up to 4÷5 times higher than that of the substrate and up to 1.5 times higher than that of conventionally used electrodes.

- 11. The results of the present research confirm the positive effect of coatings from alloys of the Co-Cr- Ni- Si-B-C system with additions of WC, TiB2 B4C on the structure and performance characteristics of C45 steel.

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- Zhengchuan, Zhang; Guanjun, Liu; Konoplianchenko, Ie. ; Tarelnyk, V.B. A review of the electro-spark deposition technology. In Bulletin of Sumy National Agrarian University. The series: Mechanization and Automation of Production Processes. 2021, 44, 2, 45–53.

- Barile, C. Casavola, C.; Pappalettera, G.; Renna, G. Giovanni, P. Advancements in electrospark deposition (ESD)technique: A short review. Coatings. 2022, 12, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitlevich, A.E.; Mikhailov, V.V.; et al. Electrospark alloying of metal surfaces, Chisinau, Stinitsa, 198 p., 1985, (in Ru).

- Vizureanu, P.; Perju, Manuela-Cristina; Achiţei, Dragoş-Cristian; Nejneru, C. Advanced Electro-Spark Deposition Process on Metallic Alloys. Wear. 2008, 264, 505–517. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Chang, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, S.; Xu, A.; Gao, X. Research Status and Prospect of ElectroSpark Deposition Technology, Surface Technology. 2021, 50,1,150.

- Mulin,Yu. I.; Verkhoturov,A.D.; Vlasenko,V.D. Electrospark alloying of surfaces of titanium alloys. Perspective materials. 2006, 1, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Algodi,J. ;Clare,A.T.;Brown,P.D. Modelling of single spark interactions during electrical discharge coating. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2018, 252, 760–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, I.S.; Kuznetsov, Yu. A.; Kravchenko, I.N.; Kolomeichenko, A.V.; Labusova, T.A. Analytical Study of the Appearance of Heat Sources on the Surface of a Part during Electrospark Alloying. Metallurgy (Metally), 2020, 13,1507-1512 in Russian. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.Y.; Gao, W.; Li, Z.W.; Zhang, H.F.; Hu, Z.Q. Electro÷spark Deposition of Fe-based Amorphous Alloy Coatings. Mater. Lett. 2007, 61, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanabadi, F.M.; Ghaini, M.F.; Ebrahimnia, M.; Shahverdi, H.R. Production of amorphous and nanocrystalline iron based coatings by electro-spark deposition process. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 270, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, J. Application of electro-spark deposition as a joining technology, Weld. J. 2011, 90, 191–197. [Google Scholar]

- Wei,X. ; Chen, Zhiguo; Zhong, Jue; Xiang, Yong. Feasibility of preparing Mo2FeB2-based cermet coating by electrospark deposition on high speed steel, Surface and Coatings Technology. 2016, 296, 58÷64.

- Petrzhik, M.; Molokanov, V.; Levashov, E. On conditions of bulk and surface glass formation of metallic alloys. J. Alloys Comp. 2017, 707, 68—72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadney,S. ; Brochu,M.Formation of amorphous Zr41.2Ti13.8Ni10Cu12.5Be22.5 coatings via the ElectroSpark Deposition process, Intermetallics. 2008, 16, 4, 518÷523.

- Nikolenko, S.V.; Kuz’menko, A.P.; Timakov, D.I.; Abakymov, P.V. Nanostructuring a steel surface by electrospark treatment with new electrode materials based on tungsten carbide. Surface Engineering and Applied Electrochemistry. 2011, 47, 3, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Xiang; Tan, Yefa; Zhou, Chunhua; Xu, Ting; Zhang, Zhongwei. Microstructure and tribological properties of Zr-based amorphous÷nanocrystalline coatings deposited on the surface of titanium alloys by Electrospark Deposition. Applied Surface Science. 2015, 356, 1244÷1251. [Google Scholar]

- Auchynnikau, E.; Kazak, N.; Mikhailov, V.; Ivashcu, S.; Shkurpelo, A. Tribotechnical characteristics of nanostructured coatings formed by eil method. Proceedings of BALTTRIB’2019, ISSN 2424-5089 (Online). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudryashov, A.E.; Potanin, A.Yu.; Lebedev, D.N. , et all. Structure and properties of Cr–Al–Si–B coatings produced by pulsed electrospark deposition on a nickel alloy. Surface & Coatings Technology, 2016, 285, 278–288. [Google Scholar]

- Rukanskis, M. Control of Metal Surface Mechanical and Tribological Characteristics Using Cost Effective Electro-Spark Deposition, Surface Engineering and Applied Electrochemistry. 2019, 55, 5, 607–619.

- Padgurskas, J.; Kreivaitis, R.; Rukuiža, R.; Mihailov, V.; Agafii, V.; Kriukiene, R.; Baltušnikas, A. Tribological properties of coatings obtained by electro-spark alloying C45 steel surfaces. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 311, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.J.; Qian, Y.Y.; Liu, J. Structural and Interfacial Analysis of WC92-Co8 Coating Deposited on Titanium Alloy by Electrospark Deposition, Applied Surface Science. 2004, 228, 405–409.

- Penyashki, T.; Kostadinov, G.; Mortev, I.; Dimitrova, E. Investigation of properties and wear of WC, TiC and TiN based multilayer coatings applied onto steels C45, 210CR12 and HS6-5-2 deposited by non-contact electrospark process. Journal of the Balkan Tribological Association. 2017, 23, 2, 325–342. [Google Scholar]

- Aghajani, H.; Hadavand, E.; Peighambardoust, Naeimeh-Sadat; Khameneh-asl, Sh. Electro spark deposition of WC–TiC–Co–Ni cermet coatings on St52 steel. Surfaces and Interfaces. 2020, 18, 100392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkov, A.A.; Pyachin, S.A.; Zaytsev, A.V. Influence of Carbon Content of WC÷Co Electrode Materials on the Wear Resistance of Electrospark Coatings. Journal of Surface Engineered Materials and Advanced Technology. 2012, 2, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarelnyk, V.B.; Paustovskii, A.V.; Tkachenko, Y.G.; Konoplianchenko, E.V.; Martsynkovskyi, V.S.; Antoszewski, B. Electrode Materials for Composite and Multilayer Electrospark-Deposited Coatings from Ni–Cr and WC–Co Alloys and Metals. Powder Metall. Met. Ceram. 2017, 55, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.; Pirolli, L.; Deng, F.; Ni, CY.; Teplyakov, A.V. Structurally different interfaces between electrospark deposited titanium carbonitride and tungsten carbide films on steel. Surface and Coating Technology. 2014, 258, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamulaeva, E.I.; Levashov, E.A; et al. Carbon-containing and nanostructured WC—Co electrodes for electrospark modification of the surface of titanium alloys. Metal technology. 2008, 11, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- 28, Tarelnyk, V. ; Gaponova, O.; Myslyvchenko, O.; Sarzhanov, B. Electrospark deposition of multilayer coatings, Powder Metallurgy and Metal Ceramics. 2020, 59, 76–88.

- Kandeva, M.; Penyashki, T.; Kostadinov, G.; Nikolova, M.; Grozdanova, T. Wear resistance of multi-component composite coatings applied by concentrating energy flows, Proceedings on Engineering Sciences—PES journal—16th International Conference on Tribology, Kragujevac, Serbia, 2019, 1,1, 197-207.

- Paustovskii, A.V.; Tkachenko, Yu.G.; Alfintseva, R.A.; Kirilenko, S.N.; Yurchenko, D.Z. Optimization of the composition, structure and properties of electrode materials and electrospark coatings during the hardening and restoration of metal surfaces. Surface Engineering and Applied Electrochemistry. 2013, 49, 1, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailov, V.; Kazak, N.; Ivashcu, S.; Ovchinnikov, E.; Baciu, C.; Ianachevici, A.; Rukuiza, R.; Zunda, A. Synthesis of Multicomponent Coatings by Electrospark Alloying with Powder Materials. Coatings. 2023, 13, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penyashki, T.G.; Radev, D.D.; Kandeva, M.K; Kostadinov, G.D. Structural and TribologicalProperties of Multicomponent Coatings on 45 and 210Cr12 Steels Obtained by Electrospark Deposition with WC-B4C-TiB2–Ni-Cr-Co-B-Si Electrodes. Surf. Eng. Appl. Electrochem. 2019, 55, 6, 638–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhoturov, A.D.; Nikolenko, S.V. Classifications. Development and creation of electrode materials for electrospark alloying. Hardening technologies and coatings. 2010, 2, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Penyashki, T.; Kostadinov, G.; Kandeva, M.; Kamburov, V.; Nikolov, A. Abrasive and Erosive Wear of TI6Al4V Alloy with Electrospark Deposited Coatings of Multicomponent Hard Alloys Materials Based of WC and TiBCoatings. 2023, 13,1, 215.

- Nikolenko, V.; Verkhoturov, A.D.; Syui, N. A Generation and study of new electrode materialswith self-fluxing additives to improve the efficiency of mechanical electrospark alloying, Surface Engineering and Applied Electrochemistry. 2015, 51, 1, 38-45.

- Kandeva, M.; Svoboda, P.; Kalitchin, Zh.; Penyashki, T.; Kostadinov, G. Wear of Gas-flame Composite Coatings with Tungsten and Nickel Matrix. Part II. Erosive Wear. Journal of Environmental protection and ecology. 2019, 20 3, 1292–1302. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, M.A.; Rico, A.; Gómez, M.T.; Fernández÷Rico, J.E.; Rodríguez, J. Tribological and Oxidative Behavior of Thermally Sprayed NiCrBSi Coatings. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology. 2017, 26, 3, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houdková, S.; Smazalová, E.; Vostřák, M.; Schubert, J. Properties of NiCrBSi Coating, as Sprayed and Remelted by Different Technologies. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2014, 253, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, G.Y.; Bolfarini, C.; Kiminami, C.S.; et al. An Overview of Thermally Sprayed Fe-Cr-Nb-B Metallic Glass Coatings: From the Alloy Development to the Coating’s Performance Against Corrosion and Wear. J Therm Spray Tech. 2022, 31, 923–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alontseva, D.; Missevra, S.; Russakova, A. Characteristics of Structure and Properties of Plasma- Detonated Ni-Cr and Co-Cr Based Powder Alloys Coatings. Journal of Materials Science and Engineering. 2013, 1, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert,J.; Houdková, J.Š.; Kašparová, M.; Česánek Z. Effect of Co content on the properties of HVOF sprayed coatings based on tungsten carbide. Proceedings of 21st International Conference on Metallurgy and Materials – Metal 2012, Brno (Czech Republic), 23-25.05.2012, 1086, 2012.

- Fanicchi, F.; Axinte, D.A.; Kell, J.; Brewster, G.; Norton, A.D. Combustion Flame Spray of CoNiCrAl coatings. Surface and Coatings Technology. 2017, 315, 546–557. [Google Scholar]

- Vivek, D.; Kalyankar, P.; Wanare, Sachin. Comparative Investigations on Microstructure and Slurry Abrasive Wear Resistance of NiCrBSi and NiCrBSi-WC Composite Hardfacings Deposited on 304 Stainless Steel. Tribology in Industry. 2022, 44, 2, 199–211. [Google Scholar]

- Vencl, А.; Mrdak, M.; Hvizdos, P. Tribological Properties of WC÷Co/NiCrBSi and Mo/NiCrBSi Plasma Spray Coatings under Boundary Lubrication Conditions. Tribology in industry. 2017, 39, 2,, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umansky, A.P.; Storozhenko, M.S.; Akopyan, V.V.; Martsenyuk, I.S. Electrospark strengthening of steel by composite materials of the TiB2-(Fe-Mo) system. Aviation and space engineering and technology. 2012, 96, 9, 214–218. [Google Scholar]

- Podchernyaeva, A.; Verkhoturov, A.D.; Panashenko, V.M. , Konevtsov, L.A. Electric sparк surface hardening and integrated surface hardening of titanium Study notes 2014, 17, 1–1, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Kazamer, N.; Valean, P.C.; Pascal, D.; Serban, V.A.; Muntean, R.; Margineal, G. Microstructure and phase composition of NiCrBSi–TiB2 vacuum furnace fused flame-sprayed coatings, in: 7th Int. Conf. Advanced Mater. Structures-AMS. 2018, 416, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umanskii, A.P.; Storozhenko, M.S.; Hussainova, I.; Terentiev, A.E.; Kovalchenko, A.M.; Antonov, Structure, phase composition and wear mechanisms of plasma-sprayed NiCrBSi–20 wt. % TiB2 coating. Powder Metall. Met. Ceram. 2015, 53, No. 11–12, 663–671. [Google Scholar]

- JÖNSSON, B.; HOGMARK, S. Hardness Measurements of Thin Films. Thin Solid Film, 1984, 114, 257.

| Element , % | С | Si | Cr | Fe | B | Co | Ni | Designation of composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoNiCrBSi | 1.5 | 1.5 | 23 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 40 | balance | KW=45%CoNiCrBSi + 55%WC |

| Designation/ Composition, % | KW | WC- Сo8 | TiB2 | B4C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KWT10 | 90 | - | 10 | - |

| KWB10T10 | 80 | - | 10 | 10 |

| KWW10B10T10 | 70 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| KWB10T20 | 70 | - | 20 | 10 |

| KWW10B10T20 | 50 | 10 | 20 | 20 |

| KWB20T20 | 60 | - | 20 | 20 |

| KWW10B20T20 | 50 | 10 | 20 | 20 |

| WК8 | 92/8 |

| № of regimes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Сapacity, С, µF | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 50 | 100 |

| Pulse energy Е, J | 0.02 | 0.03 | ≈0.05 | ≈0.07 | ≈0.16 | ≈0.3J |

| № | Electrode, Е= 0.03÷0.3 J | Ra, mm | d, mm | Hv, GPa | Coeff. Of hardening |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | WК8 | 1.8÷5.5 | 14÷42 | 7.8÷12 | 3÷5 |

| 2 | KWТ10 | 2.5÷5.3 | 19÷66 | 8÷12 | 3÷5 |

| 3 | KWB10T10 | 2.5÷5.3 | 18÷63 | 8.3÷12.5 | 3÷5.3 |

| 4 | KWW10B10T10 | 2.3÷5.6 | 16÷59 | 8.8÷13 | 3.5÷5.6 |

| 5 | KWB10T20 | 2.2÷5.5 | 16÷56 | 8.8÷13 | 3.5÷5.6 |

| 6 | KWW10B10Т20 | 2.2÷5.9 | 20÷53 | 9.5÷14.5 | 3.6÷6.2 |

| 7 | KWB20T20 | 2.1÷5.8 | 18÷55 | 9÷14 | 3.8÷6 |

| 8 | KWW10B20T20 | 2.1÷6.8 | 18÷55 | 9.5÷15 | 3.8÷6.4 |

| Electrode, Impulse energy, J | Roughness and thickness δ of the coating after 3 electrode passes | Average thickness | Cathode growth, mg/cm2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roughness, µm | Thickness δ, µm | µm | mg/cm2 | |||||

| Ra | Rz | Rt | min | max | ||||

| Substrate | 2.38 | 9.56 | 2.7 | 9.65 | - | - | - | - |

| KWW10B20T20,Е=0.07 | 4.84 | 14.12 | 5.50 | 17.63 | 27.6 | 35.5 | 30 | 0.67 |

| KWB20T20, Е=0.07 | 4.46 | 12.72 | 5.16 | 15.58 | 30.2 | 38.1 | 33 | 0.83 |

| KWW10B10T10, E0.07 | 4.29 | 12.62 | 4.67 | 14.63 | 33.6 | 41.9 | 36 | 1.2 |

| KWW10B10T10, E0.05 | 4.04 | 11.8 | 4.44 | 13.48 | 23.7 | 30.3 | 28 | 0.88 |

| KWB10T10, E=0.07 | 3.87 | 12.2 | 3.6 | 14.11 | 35.6 | 43.5 | 40 | 1.43 |

| KWB10T10, E=0.05 | 3.38 | 9.56 | 3.7 | 11.65 | 26.5 | 35.9 | 32 | 1.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).