1. Introduction

Blockchain technology stands as a revolutionary advancement in the digital age, fundamentally reshaping how data is stored, shared, and trusted across decentralized networks. Introduced by Satoshi Nakamoto in 2008 as the foundation for Bitcoin, blockchain has expanded far beyond its cryptocurrency origins, influencing sectors such as finance, healthcare, supply chain management, education, and governance (Nakamoto, 2008). Traditional systems rely on centralized authorities—banks, governments, or corporations—to validate and secure transactions, often introducing vulnerabilities like single points of failure, higher operational costs, and inefficiencies due to bureaucratic overhead. Blockchain, by contrast, distributes this responsibility across a network of nodes, each maintaining an identical copy of the ledger, thereby enhancing resilience, autonomy, and fault tolerance. This paradigm shift eliminates intermediaries, streamlining processes, reducing expenses, and democratizing access to secure systems. However, it raises a critical question: how can trust and security be maintained in a system without a central overseer? The answer lies in cryptography, the mathematical science of encoding and decoding information, which serves as the indispensable infrastructure enabling blockchain’s functionality.

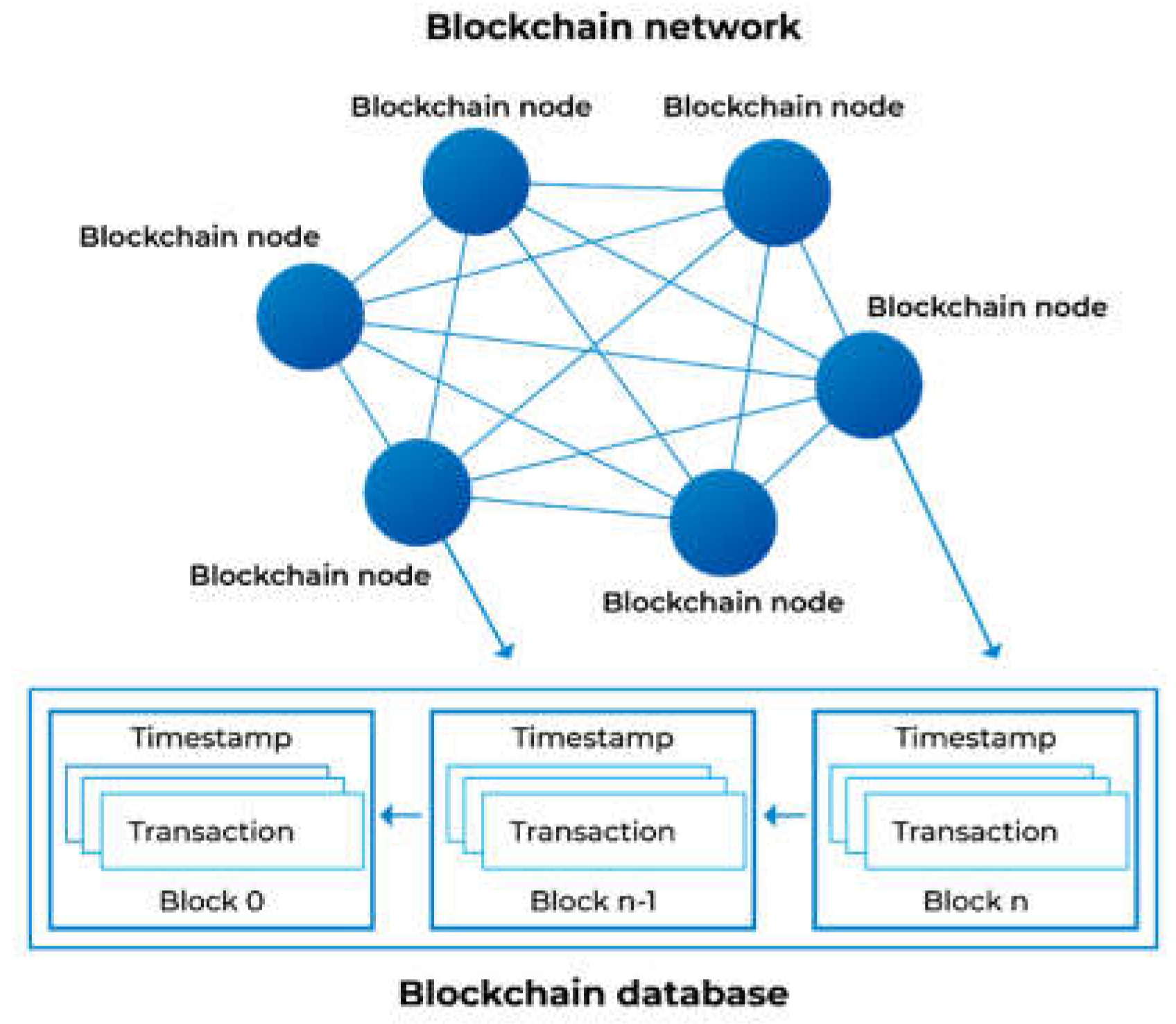

At its core, blockchain is a distributed ledger comprising a chain of blocks—data containers holding transactions—linked chronologically through sophisticated cryptographic mechanisms. These blocks are replicated across all participating nodes, ensuring that no single entity can alter the record without achieving network-wide consensus, a process governed by cryptographic proofs. Blockchain’s defining characteristics—immutability (the inability to modify historical data), transparency (public visibility of transactions), and security (protection against unauthorized changes)—are not merely byproducts of its decentralized architecture but are actively enabled by advanced cryptographic techniques. Hash functions, such as the Secure Hash Algorithm 256-bit (SHA-256), generate unique digital fingerprints for each block, making any tampering immediately detectable across the network by disrupting the chain’s integrity. Digital signatures, exemplified by the Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA), authenticate transactions, verifying participant identities without exposing sensitive credentials, thus ensuring only authorized actions occur. Merkle trees, a hierarchical structure of hashed data, optimize the verification of extensive transaction sets, improving efficiency and scalability in distributed environments. Together, these cryptographic tools create a robust framework that underpins blockchain’s reliability, positioning it as a credible alternative to centralized infrastructures that often suffer from opacity and vulnerability.

The importance of cryptography to blockchain is profound—it is the linchpin that enables trust in a trustless ecosystem. Without these methods, the system’s ability to facilitate secure interactions among anonymous parties over the internet would collapse, rendering it useless for its intended purposes. For instance, Bitcoin’s capacity to process transactions worth billions of dollars without a central bank hinges on SHA-256’s integrity and ECDSA’s authentication capabilities (Antonopoulos, 2017). Consider a practical example: a Bitcoin transaction transferring $1 million relies on SHA-256 to ensure the block containing it remains unaltered, while ECDSA confirms the sender’s ownership of the funds, all without a bank’s involvement. Similarly, Ethereum’s smart contracts—self-executing agreements embedded in the blockchain—depend on cryptographic signatures to enforce terms autonomously, bypassing third-party oversight (Buterin, 2014). A smart contract managing a real estate sale, for instance, uses ECDSA to verify the buyer’s payment and automatically transfers ownership, showcasing cryptography’s role in enabling complex, trustless operations. As blockchain adoption accelerates, fueled by its promise of decentralization, efficiency, and resilience, its cryptographic foundations face increasing examination.

Emerging threats, such as quantum computing’s potential to decrypt existing algorithms, pose significant risks to blockchain’s security model. A quantum computer running Shor’s algorithm could theoretically break ECDSA, exposing private keys and undermining the system’s trust framework. Practical challenges also loom large, including the computational burden of cryptographic operations that restrict transaction throughput, limiting blockchain’s ability to scale for widespread use. Bitcoin, for example, processes just 7 transactions per second, compared to Visa’s 24,000, a gap driven by the intensive hashing required for PoW (Zhang et al., 2022). These issues cast doubt on blockchain’s long-term sustainability unless addressed through innovation and adaptation.

This paper aims to deliver an in-depth exploration of blockchain’s reliance on cryptographic methods, addressing three pivotal questions: How do these techniques underpin blockchain’s essential functionality? What strengths and limitations emerge from this dependence? What future advancements can safeguard its security and scalability moving forward? To tackle these, the study employs a comprehensive methodology. It begins with a literature review to synthesize existing research, establishing a theoretical foundation rooted in seminal and contemporary works. Next, a detailed technical analysis dissects the primary cryptographic methods—hash functions, digital signatures, and Merkle trees—detailing their specific roles and implementations within blockchain ecosystems like Bitcoin and Ethereum. A Python-based proof-of-concept then provides practical evidence, demonstrating how hashing secures block linkages in a simplified blockchain, reinforcing theoretical insights with hands-on application. Finally, real-world examples from finance (e.g., decentralized finance platforms) and supply chains (e.g., Walmart’s tracking system) illustrate the broader implications of this cryptographic reliance, grounding the study in tangible outcomes.

The paper is structured to guide readers through a logical progression of ideas.

Section 2 reviews prior academic contributions, pinpointing key insights and identifying research gaps.

Section 3 explores the cryptographic mechanisms sustaining blockchain operations, offering technical depth.

Section 4 and

Section 5 evaluate the resultant strengths and limitations, providing a balanced assessment.

Section 6 outlines the methodology behind the proof-of-concept, bridging theory and practice.

Section 7 investigates future cryptographic innovations to address emerging challenges.

Section 8 discusses practical applications, linking theory to real-world impact, and

Section 9 concludes with key findings and actionable recommendations. Aimed at computer science researchers, developers, and practitioners, this study offers a holistic perspective on blockchain’s cryptographic backbone, contributing to the ongoing dialogue about its evolution, resilience, and potential in an ever-changing technological landscape. By illuminating both the power and the pitfalls of this relationship, it seeks to inform strategies for enhancing blockchain’s durability as it continues to redefine digital trust and interaction.

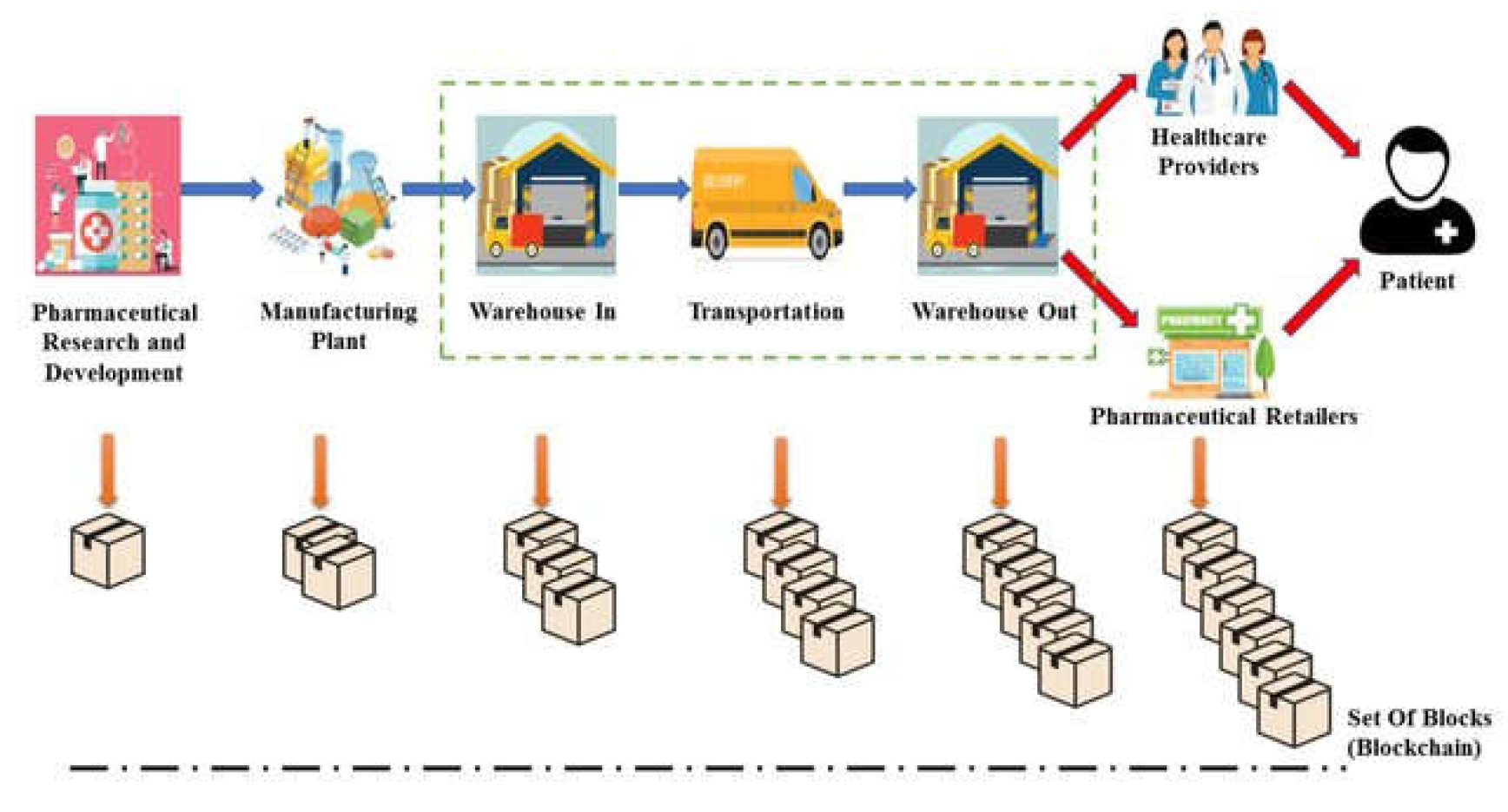

Figure 2.

Blockchain network, database, blocks, and transactions.

Figure 2.

Blockchain network, database, blocks, and transactions.

2. Literature Review

The interdependence of blockchain technology and cryptographic methods has become a focal point in academic research, reflecting its critical role in computer science and its growing influence across diverse domains. This section reviews foundational studies, recent advancements, and unresolved challenges to establish a comprehensive framework for understanding blockchain’s cryptographic reliance, setting the stage for the current investigation by highlighting key contributions and gaps in the literature.

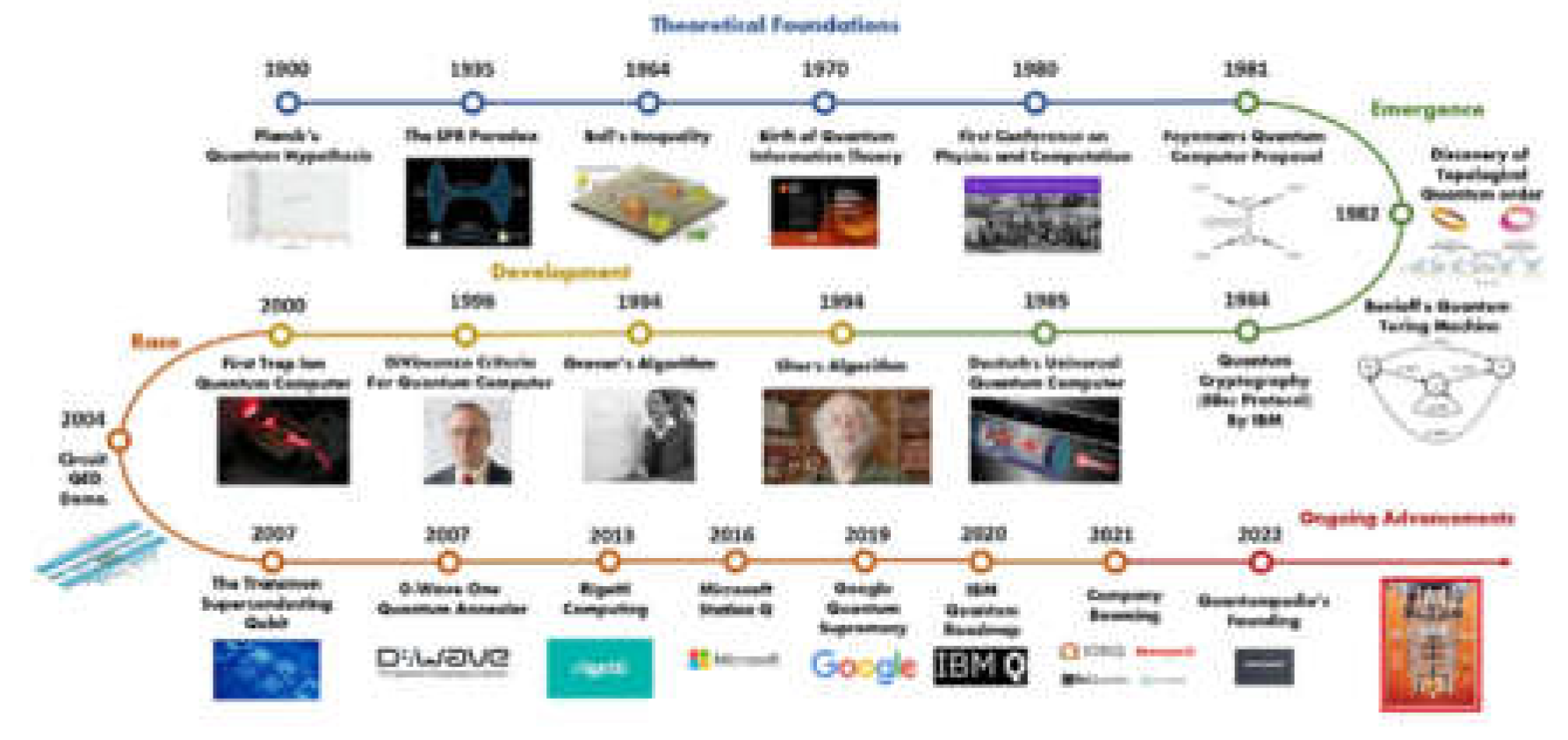

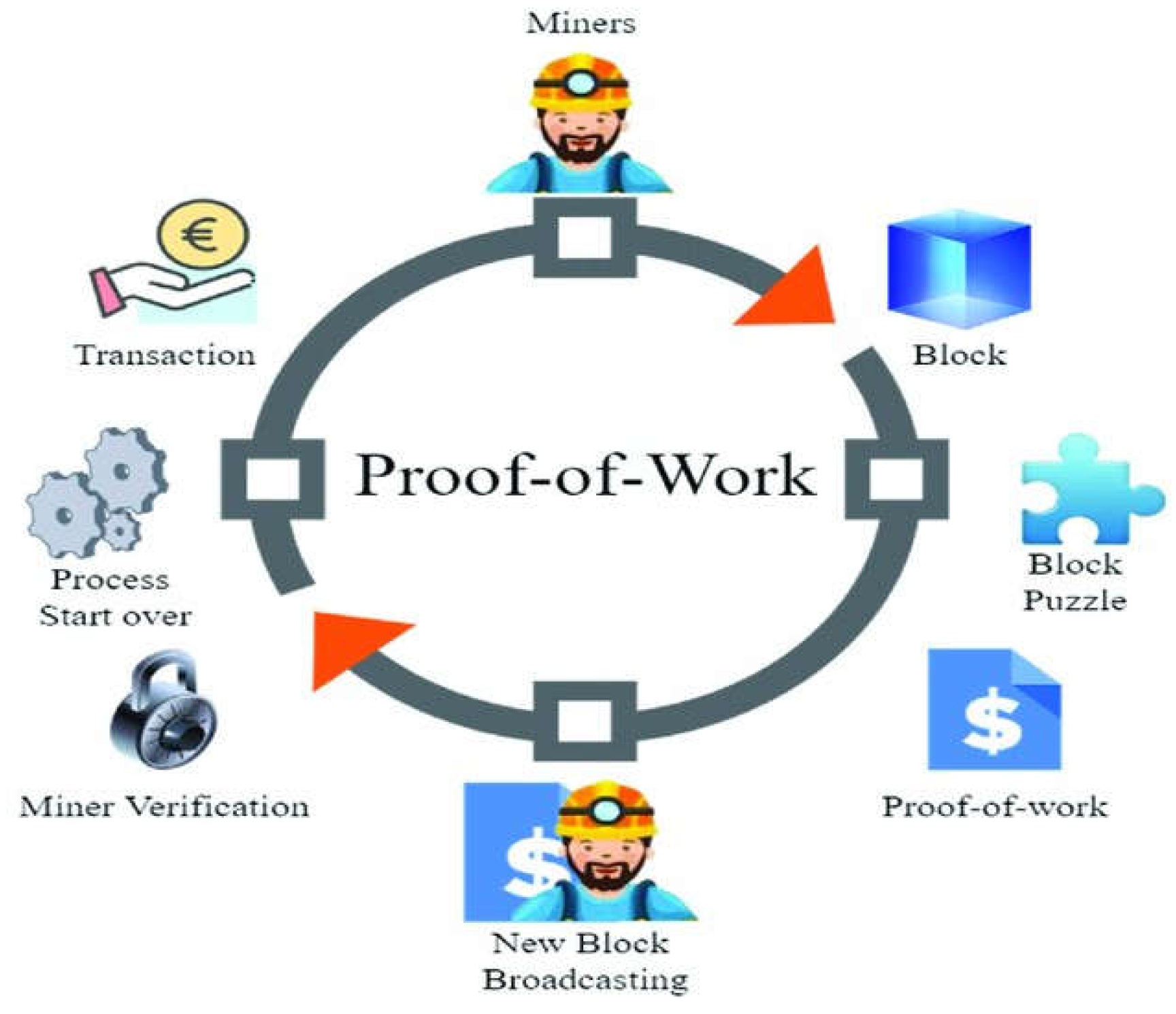

The conceptual origins of blockchain’s cryptographic architecture trace back to early efforts in secure digital record-keeping. Haber and Stornetta (1991) proposed a groundbreaking method to timestamp digital documents using cryptographic hashes, linking each record to its predecessor to prevent tampering. This approach, developed well before blockchain’s emergence, introduced the principle of immutability through hash chaining—a foundational concept that underpins modern blockchain systems. Their work demonstrated that a sequence of hashed records could create a verifiable, tamper-resistant timeline, laying the intellectual groundwork for later innovations. Satoshi Nakamoto (2008) built upon this idea in the Bitcoin whitepaper, introducing blockchain as a decentralized ledger for peer-to-peer electronic cash. Nakamoto’s system employed SHA-256 to secure blocks and implemented a Proof-of-Work (PoW) consensus mechanism to validate transactions across a distributed network, requiring miners to solve complex hash puzzles. This seminal contribution transformed cryptographic hashing from a theoretical tool into a practical cornerstone, influencing subsequent platforms like Ethereum, which extended blockchain’s use to smart contracts (Buterin, 2014).

Expanding on these early developments, Narayanan et al. (2016) provide an exhaustive analysis of blockchain’s cryptographic underpinnings in their book Bitcoin and Cryptocurrency Technologies. They argue that hash functions like SHA-256 ensure block integrity through essential properties such as collision resistance, where it is computationally infeasible to find two distinct inputs producing the same hash output. This property, coupled with determinism—where identical inputs consistently yield identical hashes—enables nodes to independently verify the blockchain’s consistency without relying on a central authority, a key enabler of decentralization. Narayanan et al. also explore digital signatures, emphasizing the role of the Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA) in transaction authentication. By signing transactions with a private key and verifying them with a public key, ECDSA ensures sender authenticity and non-repudiation while keeping sensitive data confidential, a critical feature for trustless, decentralized ecosystems. Their work provides a detailed technical foundation, illustrating how cryptography transforms abstract concepts into operational realities in systems like Bitcoin.

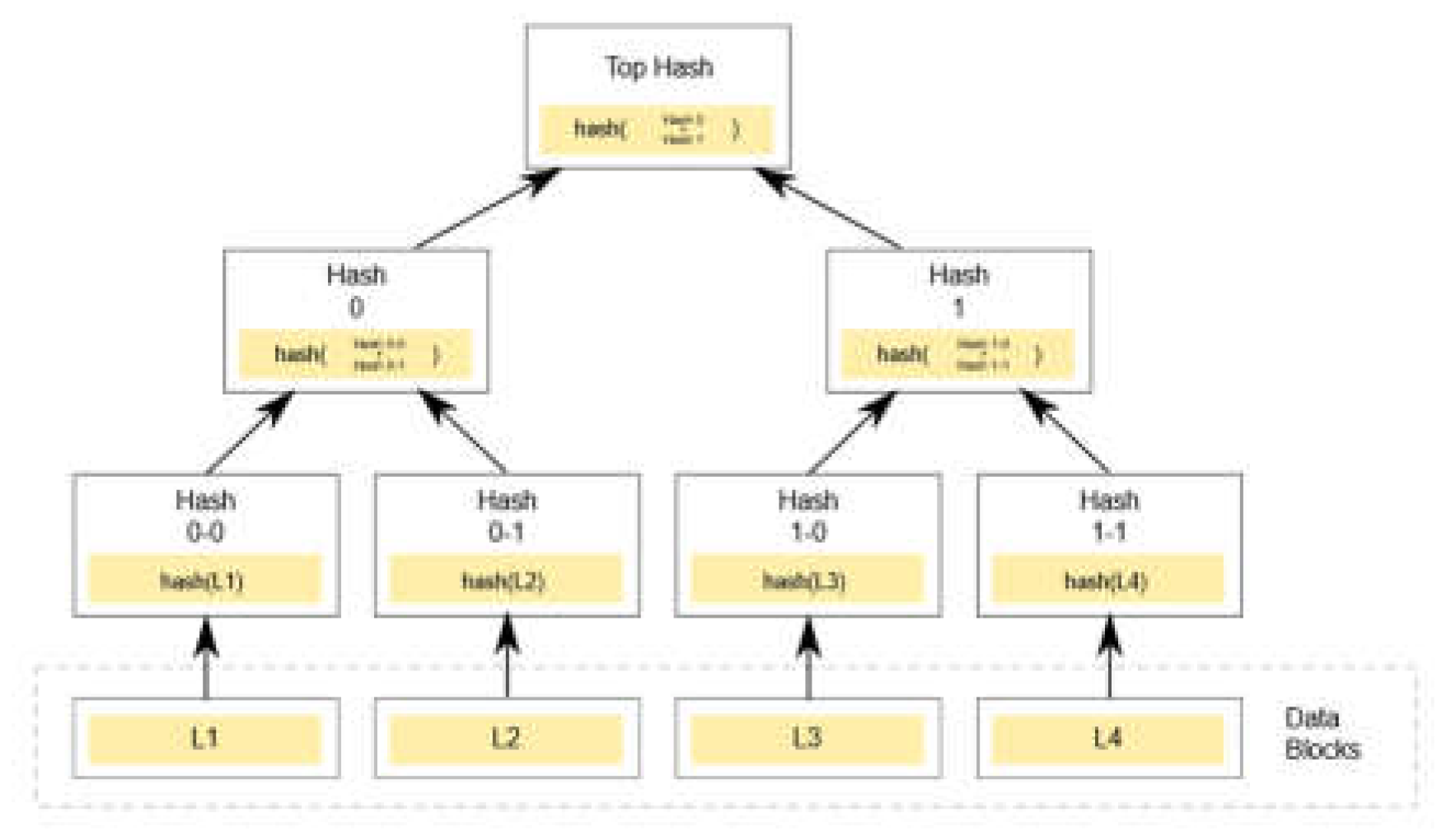

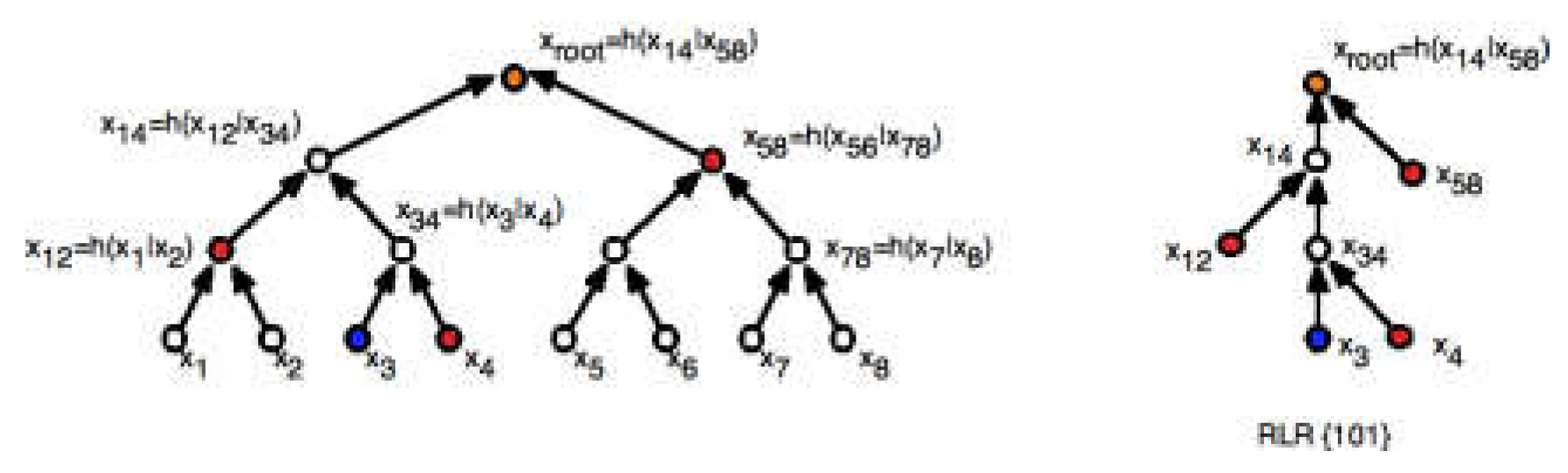

Another vital cryptographic innovation, Merkle trees, was introduced by Ralph Merkle (1980) and later adopted widely in blockchain architectures. Crosby et al. (2016) examine their practical application, explaining how Merkle trees aggregate transaction hashes into a single root hash stored in block headers. This hierarchical structure facilitates efficient verification, allowing lightweight clients—such as mobile wallets—to confirm transaction inclusion without downloading the entire blockchain, a process known as Simplified Payment Verification (SPV). For example, a Bitcoin user on a smartphone can verify a payment using a Merkle path, a small subset of hashes, rather than the full block data, reducing resource demands. Ethereum leverages Merkle trees extensively to manage its vast transaction volume and support smart contract execution, enhancing scalability (Wood, 2014). Crosby et al. argue that this efficiency bridges the gap between theoretical cryptography and real-world utility, making blockchain viable for widespread deployment across devices with varying capabilities.

Recent research has pivoted to address contemporary challenges and opportunities stemming from blockchain’s cryptographic reliance. Zhang et al. (2022) investigate scalability, a persistent obstacle tied to the computational demands of cryptographic operations. They note that Bitcoin’s use of SHA-256 in PoW limits its transaction throughput to approximately 7 transactions per second, a stark contrast to centralized systems like Visa, which process 24,000 transactions per second with ease. This bottleneck arises from the intensive nature of hashing and signature verification, which every node must perform to maintain consensus, prompting exploration of alternative consensus mechanisms like Proof-of-Stake (PoS) (King & Nadal, 2012). PoS, implemented in Ethereum 2.0, replaces energy-intensive hashing with stake-based validation, offering a potential solution to scalability woes. Meanwhile, Aggarwal et al. (2019) tackle the looming threat of quantum computing, warning that algorithms like Shor’s could decrypt ECDSA, exposing private keys and undermining blockchain security. They estimate that a sufficiently advanced quantum computer, though likely decades away (10-20 years by some projections), could render current cryptographic standards obsolete, necessitating proactive development of quantum-resistant alternatives. Their analysis underscores the urgency of preparing blockchain systems for a post-quantum future, a topic gaining traction in cryptographic research.

On the innovation frontier, Zyskind et al. (2015) advocate for zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs), such as zk-SNARKs, to enhance blockchain privacy—a critical limitation in transparent systems like Bitcoin, where all transactions are publicly visible. ZKPs enable transaction validation without revealing specific details, a capability implemented in privacy-focused blockchains like Zcash and planned for Ethereum enhancements. For instance, Zcash uses zk-SNARKs to shield transaction amounts and identities while still proving their validity, balancing privacy with auditability. This advancement highlights cryptography’s evolving role in addressing blockchain’s shortcomings, offering a pathway to reconcile security with user confidentiality. Similarly, Swan (2015) explores blockchain’s broader potential, arguing that its cryptographic foundation supports applications beyond finance, such as secure voting systems, intellectual property protection, and decentralized identity management. She cites examples like Estonia’s e-governance platform, which uses blockchain to secure citizen data, illustrating how cryptography enables trust in diverse contexts.

Despite these strides, notable gaps persist in the literature. While cryptography’s enabling role is well-documented, its dual nature as both a strength and a constraint receives less comprehensive attention. For instance, the energy demands of PoW—estimated at 121 terawatt-hours annually for Bitcoin, equivalent to the power usage of mid-sized nations like Argentina (Krause & Tolaymat, 2018)—are often sidelined in security-focused studies, despite their profound environmental and economic implications. Bitcoin’s carbon footprint, estimated at 57 megatons annually, underscores this oversight, raising questions about sustainability that remain underexplored. Likewise, the long-term consequences of quantum threats lack consensus, with varying predictions about timelines (ranging from 10 to 30 years) and mitigation strategies, leaving uncertainty about blockchain’s future resilience. Few studies integrate these challenges into a cohesive framework, often focusing narrowly on technical enhancements without addressing broader systemic impacts.

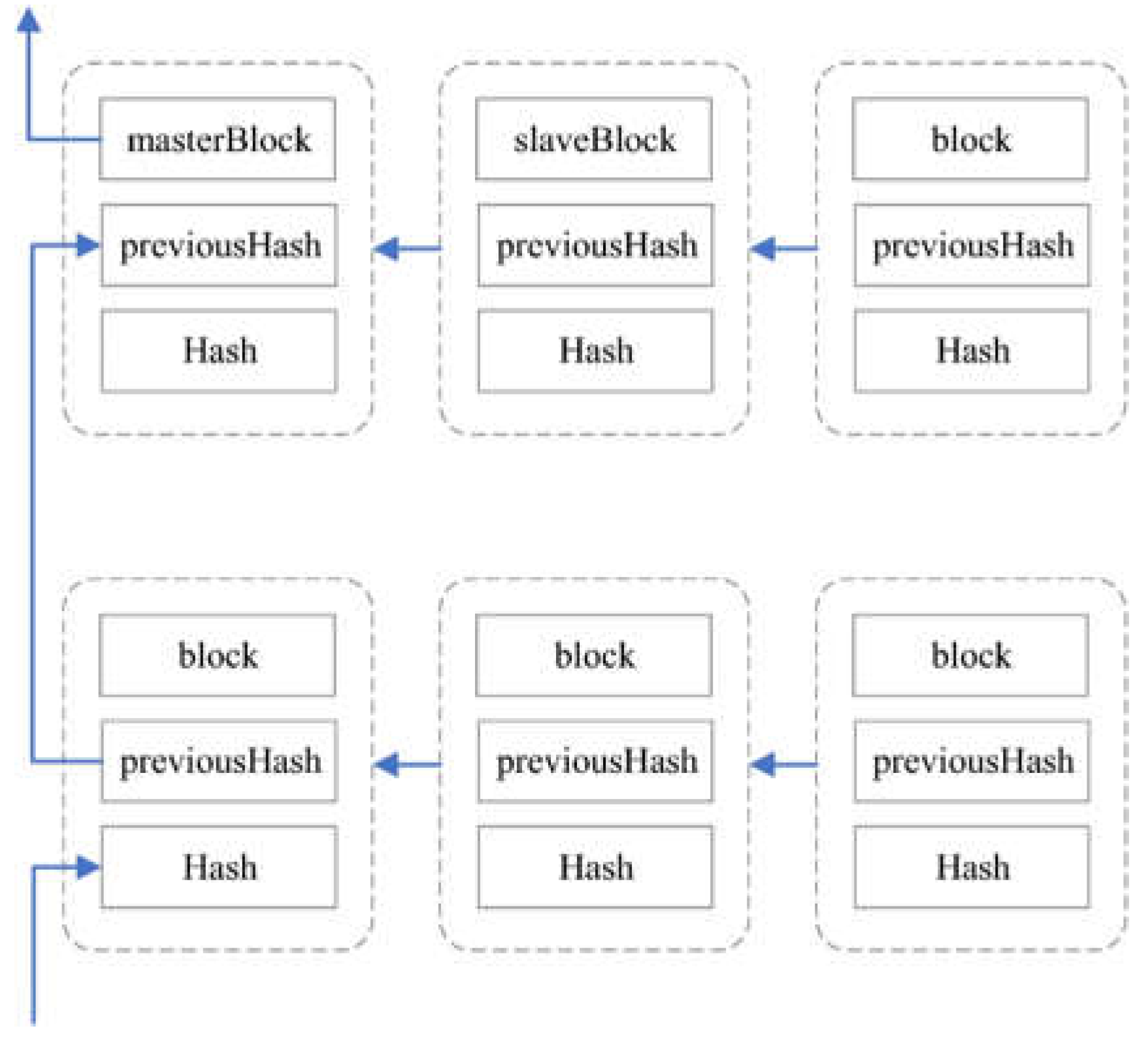

Figure 3.

Multi-level index construction method based on master–slave blockchains.

Figure 3.

Multi-level index construction method based on master–slave blockchains.

This paper seeks to fill these gaps by synthesizing foundational research with contemporary issues, offering a balanced and holistic analysis of blockchain’s cryptographic reliance. It builds on prior work by combining theoretical insights from pioneers like Haber and Nakamoto, technical depth from Narayanan and Crosby, and forward-looking perspectives from Zhang and Zyskind. Supported by a practical proof-of-concept and real-world examples, it provides a comprehensive view that not only celebrates cryptography contributions but also critically evaluates its limitations, paving the way for informed strategies to enhance blockchain’s durability and applicability in the face of technological evolution.

3. Cryptographic Methods in Blockchain

Blockchain’s ability to function as a secure, decentralized ledger relies on three core cryptographic methods: hash functions, digital signatures, and Merkle trees. This section offers a detailed examination of each technique, elucidating their specific roles, implementations, and significance within blockchain systems, and demonstrating how they collectively sustain the technology’s operational integrity and trustworthiness.

3.1. Hash Functions

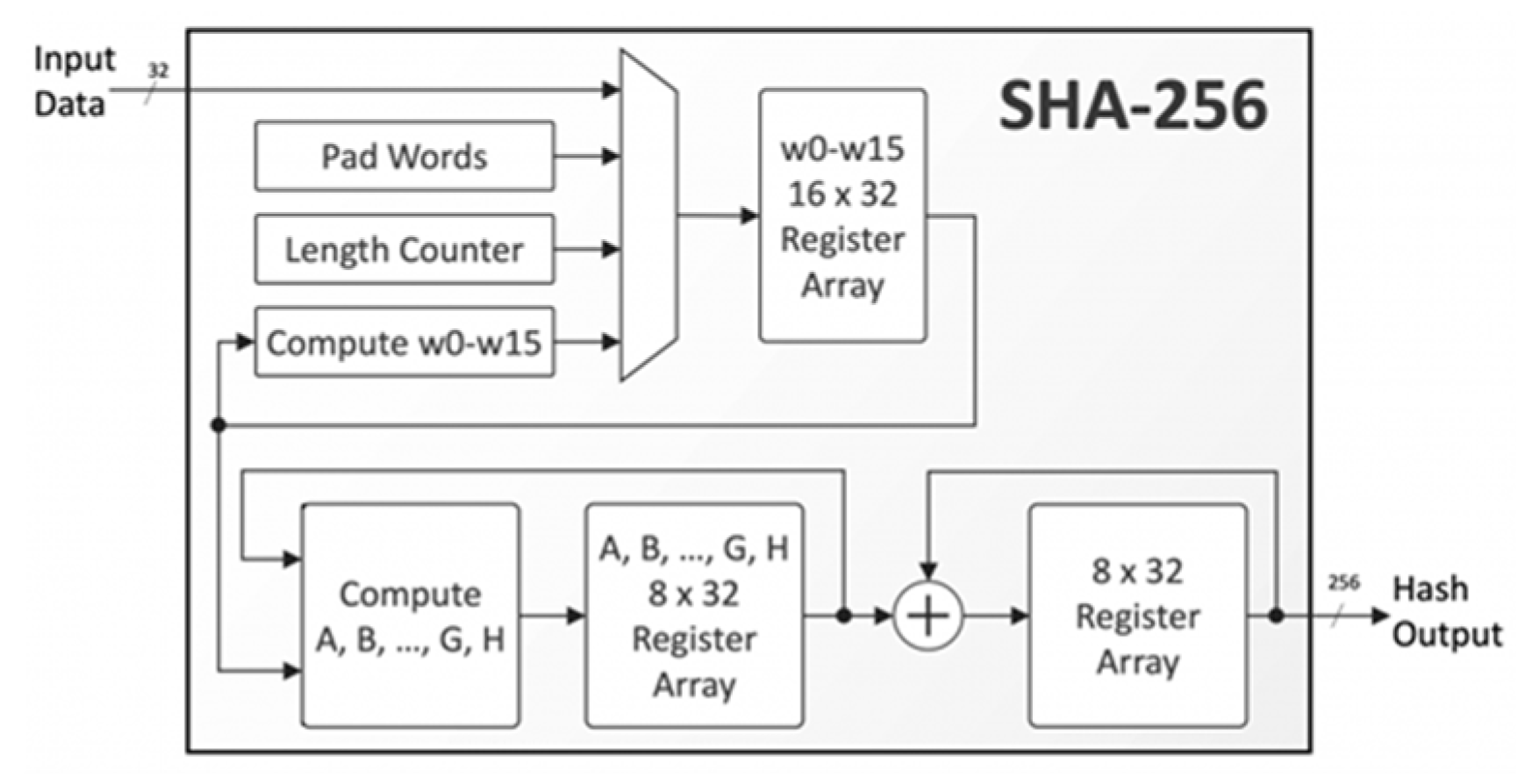

Hash functions are mathematical algorithms that transform variable-length inputs into fixed-length outputs, known as hashes, serving as a fundamental pillar of blockchain security. The Secure Hash Algorithm 256-bit (SHA-256), developed by the National Security Agency, is a linchpin of this process, widely utilized in Bitcoin and other major blockchains (Antonopoulos, 2017). SHA-256 produces a 256-bit (32-byte) hash and exhibits three critical properties: determinism, where identical inputs always generate identical outputs; preimage resistance, making it computationally infeasible to reverse-engineer the original input from the hash; and collision resistance, where it is extraordinarily unlikely for two different inputs to produce the same hash. These attributes make SHA-256 exceptionally well-suited for securing blockchain data, ensuring consistency, integrity, and verifiability across a distributed network of nodes.

In blockchain, each block’s hash is computed from its contents—typically encompassing a list of transactions, a timestamp, a nonce (a random number used in mining), and the hash of the previous block—forming a chronological chain that binds the ledger together. For example, Bitcoin’s block header includes the previous block’s hash as a field, ensuring that any modification to an earlier block alters its hash, thereby invalidating all subsequent blocks in the sequence (Nakamoto, 2008). This chaining mechanism enforces immutability, as altering a single transaction—say, changing a payment amount from 1 BTC to 10 BTC—requires recalculating the hashes of all following blocks. In a network like Bitcoin, with thousands of nodes and a hash rate exceeding 200 exahashes per second, this task is computationally infeasible, requiring more power than the combined output of multiple countries. Moreover, SHA-256 drives Bitcoin’s Proof-of-Work (PoW) consensus mechanism, where miners compete to find a nonce that, when hashed with the block’s data, produces a hash below a predefined target value (e.g., starting with a certain number of zeros). This process, known as mining, secures the network by demanding substantial computational effort, deterring malicious actors who would need to outpace the collective power of honest miners—estimated at billions of dollars in hardware—to manipulate the blockchain.

The role of hash functions extends beyond immutability to network synchronization and consensus. Every node in the blockchain independently computes and verifies block hashes, ensuring that all participants maintain an identical ledger without relying on a central authority. This decentralized validation, rooted in SHA-256’s reliability, allows blockchain to function as a trustless system, where participants depend on mathematical proofs rather than institutional intermediaries. For instance, when a new block is added to Bitcoin, nodes worldwide hash its contents and compare the result to the broadcasted hash, accepting it only if they match—an elegant application of cryptography ensuring global consistency. However, the computational intensity of hashing, particularly in PoW, introduces significant trade-offs, such as high energy consumption and limited transaction throughput, which are explored in the limitations section. Despite these drawbacks, hash functions remain the bedrock of blockchain’s structural integrity.

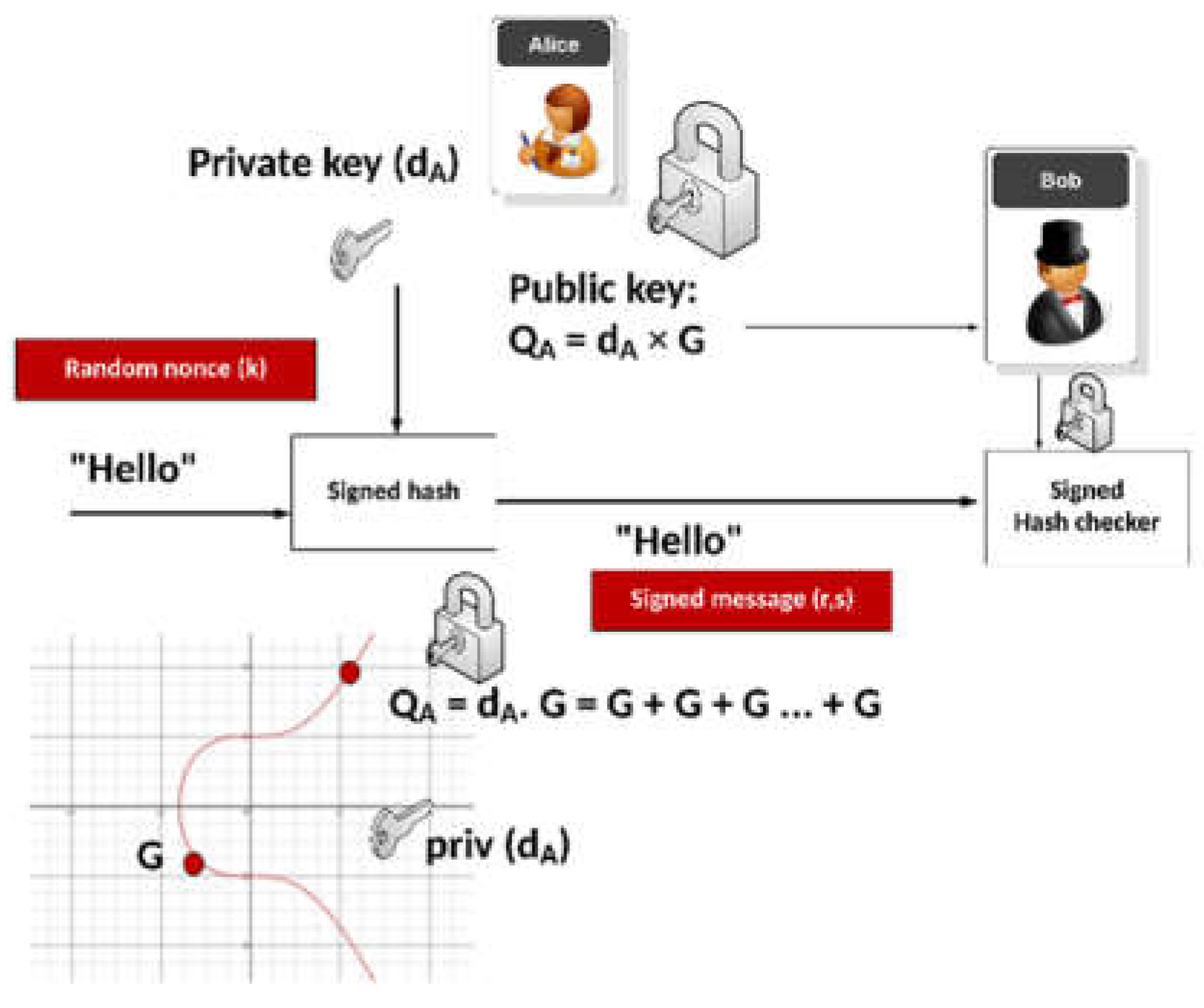

3.2. Digital Signatures

Digital signatures leverage asymmetric cryptography, utilizing a pair of keys: a private key, kept confidential by the owner, and a public key, openly shared with the network. The Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA), based on the mathematics of elliptic curves over finite fields, is a widely adopted standard in blockchain, implemented in platforms like Bitcoin and Ethereum (Johnson et al., 2001). ECDSA generates a digital signature by applying the private key to a transaction’s data—such as the sender’s address, recipient’s address, and amount—producing a unique code that the network verifies using the corresponding public key. This process ensures two essential properties: authenticity, confirming that the sender is the legitimate owner of the associated address, and non-repudiation, preventing the sender from denying their action after the transaction is broadcast.

In practice, ECDSA secures both transactions and wallet access within blockchain ecosystems. When a user initiates a cryptocurrency transfer—say, sending 5 ETH from one Ethereum address to another—they sign the transaction with their private key, creating a signature that accompanies the transaction data sent to the network. Nodes then use the sender’s public key, derived from their wallet address, to verify the signature, confirming its legitimacy without ever accessing the private key (Buterin, 2014). This eliminates the need for trusted third parties like banks, enabling secure, direct exchanges between participants. For example, Ethereum’s smart contracts rely on ECDSA to execute predefined conditions autonomously—such as releasing funds upon delivery in a supply chain contract—ensuring that only authorized parties can trigger actions. The algorithm’s efficiency—offering strong security with smaller key sizes compared to alternatives like RSA (e.g., 256-bit ECDSA keys match 3072-bit RSA security)—makes it particularly suitable for blockchain’s resource-constrained environment, where computational overhead must be minimized to maintain network performance.

ECDSA’s significance extends to user identity and asset management within blockchain systems. Each wallet address, generated from the public key via hashing (e.g., using SHA-256 and RIPEMD-160 in Bitcoin), is cryptographically tied to its private key, ensuring that only the keyholder can authorize transactions. This linkage allows blockchain to maintain security in a decentralized setting, where no central entity oversees participant credentials or resolves disputes. A real-world example is a Bitcoin user proving ownership of 10 BTC by signing a message with their private key, verifiable by anyone with the public key, without revealing the key itself. However, ECDSA’s reliance on the secrecy of private keys introduces vulnerabilities—if a key is lost or stolen, funds are irretrievable, and quantum computing could potentially decrypt it, topics addressed later in the limitations section.

3.3. Merkle Trees

Merkle trees, also known as hash trees, are hierarchical data structures that organize transaction hashes into a single root hash, enhancing both efficiency and integrity in blockchain systems (Merkle, 1980). In a Merkle tree, each transaction is individually hashed—typically using SHA-256—and these hashes are then paired and hashed again in a bottom-up process, repeating until a single root hash, the Merkle root, is produced. This root, embedded in the block header alongside the previous block’s hash and nonce, serves as a cryptographic summary of all transactions within the block, providing a compact yet comprehensive representation of the data that can be efficiently verified.

Merkle trees offer two primary advantages in blockchain operations. First, they enable efficient verification of transaction inclusion, a critical feature for scalability. Lightweight clients, such as mobile wallets or nodes with limited storage, can confirm a transaction’s presence in a block by requesting a Merkle path—a small subset of intermediate hashes linking the transaction’s hash to the Merkle root—rather than downloading the entire block, which could be megabytes in size (Wood, 2014). For example, in Bitcoin, a user verifying a payment of 0.5 BTC requests the Merkle path (typically a dozen hashes) and reconstructs the root; if it matches the block header’s Merkle root, the transaction’s validity is proven, reducing bandwidth and storage demands significantly. This process, known as Simplified Payment Verification (SPV), allows resource-limited devices to participate in the network without compromising security. Second, Merkle trees ensure data integrity. Any alteration to a transaction—such as modifying its amount or recipient—changes its hash, which propagates up the tree, altering the Merkle root. Nodes detect this discrepancy instantly by comparing the computed root to the stored one, flagging potential tampering and maintaining the blockchain’s trustworthiness.

Ethereum leverages Merkle trees extensively, using them not only for transactions but also for state and receipt data in its blocks, supporting scalability for its vast transaction volume and complex smart contract ecosystem (Wood, 2014). For instance, a block with thousands of transactions—say, 5,000 transfers on Ethereum—can be summarized in a single Merkle root, enabling rapid verification across the network without requiring nodes to process every transaction individually. This optimization is vital for blockchain’s practical deployment, bridging the gap between security and performance in large-scale systems. However, constructing and maintaining Merkle trees adds computational overhead, particularly as transaction volumes grow, requiring nodes to compute multiple hashes per block—a consideration balanced against their benefits in enhancing efficiency and integrity.

Together, hash functions, digital signatures, and Merkle trees form an interlocking cryptographic framework that sustains blockchain’s decentralized trust model. Hashing secures block linkages, ensuring immutability and consensus; digital signatures authenticate actions, enabling secure transactions; and Merkle trees streamline data verification, supporting scalability. This synergy underpins blockchain’s ability to operate reliably in a distributed environment, making cryptography its operational backbone.

4. Strengths Enabled by Cryptography

Cryptography endows blockchain with three defining strengths—immutability, security, and transparency—that distinguish it from traditional centralized systems and drive its transformative potential across a wide range of applications. These attributes, rooted in cryptographic techniques, enable blockchain to establish trust in decentralized settings where conventional intermediaries are absent.

4.1. Immutability

Immutability, the inability to modify past records, is a hallmark of blockchain technology, directly enabled by the cryptographic technique of hash chaining. Each block’s hash incorporates the hash of the previous block, creating a sequential, interdependent chain of data that spans the entire blockchain (Swan, 2015). Altering a transaction within an earlier block—such as changing a payment from 2 BTC to 20 BTC—changes its hash, which in turn invalidates the hashes of all subsequent blocks. In expansive networks like Bitcoin, which comprises thousands of nodes worldwide with a collective hash rate exceeding 200 exahashes per second, this alteration requires recalculating and revalidating the entire chain—a task rendered computationally infeasible due to the Proof-of-Work (PoW) consensus mechanism. PoW demands that miners expend significant computational resources to solve hash-based puzzles, adjusting the nonce until the block’s hash meets a stringent target (e.g., starting with 17 zeros), securing the network against tampering (Nakamoto, 2008). For instance, reversing a Bitcoin block from 2020 would necessitate more energy than the annual consumption of countries like Sweden or Malaysia—estimated at over 100 terawatt-hours—making such an attack impractical (Antonopoulos, 2017).

This cryptographic enforcement of immutability has profound implications for applications requiring permanent, trustworthy records. In property management, blockchain can store ownership deeds, preventing fraudulent alterations by ensuring that any change to a deed’s record would disrupt the chain, detectable by all nodes. In financial auditing, it provides an unchangeable ledger of transactions, enabling regulators or companies to verify historical data with certainty—say, confirming a firm’s revenue over a decade without fear of manipulation. The assurance that past data cannot be rewritten without overwhelming the network’s collective computational power provides a level of reliability unmatched by centralized databases, where a single breach or insider threat can compromise the entire system. This strength positions blockchain as a game-changer for industries reliant on unalterable records.

4.2. Security

Blockchain’s security against unauthorized tampering arises from the powerful combination of cryptography and decentralization, creating a fortress-like defense that protects the system and its users. Digital signatures, such as ECDSA, authenticate every transaction, ensuring that only the rightful owner of a private key can initiate actions like transferring funds or executing contracts (Buterin, 2014). This cryptographic verification, paired with the distributed nature of the ledger, eliminates single points of failure inherent in centralized systems, where a hacked server could expose all data. An attacker seeking to alter the blockchain must compromise a majority of nodes—a so-called 51% attack—which, in large networks like Bitcoin, requires billions of dollars in hardware and energy to outpace the network’s hash rate, currently valued at over $20 billion in mining infrastructure (Nakamoto, 2008). Bitcoin’s 15-year history without a successful ledger hack exemplifies this resilience, with no instance of the blockchain itself (as opposed to individual wallets) being compromised, showcasing cryptography’s protective power (Antonopoulos, 2017).

This security extends to user assets and interactions across various blockchain applications. In cryptocurrency wallets, ECDSA ensures that funds—say, 100 BTC in a user’s address—can only be spent by the private keyholder, safeguarding against theft unless the key is exposed through user error or phishing. In Ethereum’s smart contracts, cryptographic signatures enforce terms without intermediaries—for example, a contract releasing 50 ETH to a supplier upon delivery confirmation, verified by the supplier’s signed acknowledgment (Buterin, 2014). This robust security model enables blockchain to support high-stakes applications, such as cross-border payments worth millions or digital identity systems storing sensitive personal data, where trust is critical but traditional intermediaries like banks or governments are bypassed. The cryptographic assurance that only authorized actions succeed underpins blockchain’s reliability in these contexts.

4.3. Transparency

Transparency emerges from blockchain’s public and verifiable design, a feature made possible by the strategic application of cryptographic techniques that ensure openness without sacrificing security. In public blockchains like Bitcoin and Ethereum, every transaction is hashed and signed, recorded on a ledger accessible to all network participants—nodes, users, and observers alike. Anyone can verify a transaction’s integrity by checking its hash against the block it resides in or validating its digital signature against the sender’s public key, fostering trust without requiring intermediaries (Swan, 2015). For example, Ethereum’s open ledger allows real-time auditing of smart contracts—say, a crowdfunding contract raising 1,000 ETH—enabling backers to confirm that funds are handled as programmed, reducing the risk of fraud or mismanagement (Buterin, 2014). This visibility, secured by cryptographic integrity, ensures that actions are accountable and auditable, contrasting sharply with opaque centralized systems where data can be concealed or altered behind closed doors.

This transparency is particularly valuable in applications demanding openness and accountability. In voting systems, blockchain can record ballots publicly while preserving voter anonymity through cryptographic means—hashing voter IDs and signing votes—ensuring election integrity verifiable by all stakeholders. In supply chains, it tracks goods from origin to destination, with each step hashed and verifiable by consumers or regulators—for instance, tracing a shipment of organic coffee from a farm in Colombia to a store in Europe (Queiroz et al., 2019). By leveraging cryptography to make data both secure and accessible, blockchain creates a transparent environment that aligns with modern demands for openness in digital interactions, fostering confidence among participants who might otherwise distrust a faceless network.

Collectively, these strengths—immutability, security, and transparency—position blockchain as a revolutionary technology, directly attributable to its cryptographic foundation. They enable trust in decentralized settings where traditional trust mechanisms are absent, driving adoption across industries where reliability, protection, and visibility are paramount, from financial services to public administration.

5. Limitations Stemming from Cryptography

While cryptography empowers blockchain with remarkable strengths, it also imposes significant limitations—quantum vulnerabilities, scalability constraints, and energy costs—that challenge the technology’s broader adoption, scalability, and long-term sustainability. These drawbacks highlight the complex trade-offs inherent in blockchain’s cryptographic reliance.

5.1. Quantum Threats

Quantum computing poses a formidable long-term threat to blockchain’s cryptographic security, with the potential to undermine the algorithms that safeguard its integrity and confidentiality. Shor’s algorithm, executable on a sufficiently powerful quantum computer, could decrypt ECDSA by deriving private keys from public keys in polynomial time, enabling attackers to access wallets and forge transactions with impunity (Aggarwal et al., 2019). For example, a quantum attacker could drain a Bitcoin wallet holding 1,000 BTC by reconstructing the private key from its public address, a feat impossible with classical computers. Grover’s algorithm, while less catastrophic, could accelerate hash collisions in SHA-256, halving the security level (e.g., reducing 256-bit security to 128-bit), potentially weakening PoW systems, though its practical impact remains debated among cryptographers. Current estimates suggest that practical quantum computers capable of breaking these algorithms are 10-20 years away, contingent on breakthroughs in qubit stability and error correction (Bernstein et al., 2017). However, the looming risk is substantial for blockchains like Bitcoin and Ethereum, which rely heavily on ECDSA and SHA-256, potentially rendering them obsolete without significant upgrades.

This vulnerability underscores a critical dependency on cryptographic assumptions—the hardness of discrete logarithms and hash preimage problems—that may not hold in a quantum future. Blockchain’s security model, built on the computational difficulty of reversing these algorithms, could collapse if quantum technology matures faster than anticipated, exposing billions in assets to theft. Preemptive measures, such as transitioning to quantum-resistant algorithms like lattice-based cryptography, are complex and require network-wide consensus, a daunting task for decentralized systems with millions of users. Bitcoin, for instance, would need a hard fork—a divisive protocol change—to adopt such measures, risking community splits as seen in past upgrades like SegWit. The uncertainty surrounding quantum timelines—some predict 2030, others 2040—adds urgency to addressing this limitation, lest blockchain’s trust model be rendered obsolete.

5.2. Scalability Issues

Cryptographic operations, while essential for security, severely restrict blockchain’s scalability, limiting its capacity to handle high transaction volumes and compete with centralized systems. Hashing and signature verification are computationally intensive processes that every node must perform to maintain consensus and integrity. In Bitcoin, PoW requires miners to execute billions of SHA-256 hashes per block—approximately 10 minutes of global computation—capping throughput at roughly 7 transactions per second, a minuscule figure compared to Visa’s 24,000 transactions per second (Zhang et al., 2022). Ethereum’s ECDSA verification adds further latency, as each node processes every transaction—say, 15 per second during peak usage—to validate smart contracts and transfers, slowing the network under heavy demand (Buterin, 2014). This trade-off between security and speed hinders blockchain’s adoption for high-volume applications like micropayments (e.g., paying 0.001 BTC per coffee) or real-time stock trading, where rapid processing is non-negotiable.

The scalability bottleneck arises from cryptography’s design: ensuring integrity and authenticity demands repeated computation across a distributed network, unlike centralized systems that process transactions at a single, optimized point. Bitcoin’s block size, limited to 1 MB (expandable to 4 MB with SegWit), exacerbates this, fitting only about 2,000 transactions per block, a constraint rooted in SHA-256’s processing demands. Efforts to mitigate this, such as sharding (splitting the blockchain into parallel segments) or off-chain solutions like the Lightning Network, introduce complexity and potential security trade-offs—Lightning, for instance, shifts some trust to payment hubs. Ethereum’s move to sharding in its 2.0 upgrade aims to increase throughput to thousands of transactions per second, but full implementation remains years away. Until more efficient cryptographic methods or architectures are widely adopted, blockchain’s scalability remains a significant limitation, impeding its mainstream utility.

5.3. Energy Costs

The energy demands of cryptographic processes, particularly in PoW-based blockchains, represent a substantial limitation with profound environmental and economic consequences. Bitcoin’s annual energy consumption reached 121 terawatt-hours in 2021, comparable to the power usage of countries like Argentina or Norway, driven by the relentless SHA-256 hashing required in PoW (Krause & Tolaymat, 2018). Miners expend vast computational resources—equivalent to millions of high-end GPUs—to solve hash puzzles, securing the network but generating a carbon footprint estimated at 57 megatons annually, akin to the emissions of small nations like New Zealand. This energy intensity stems from PoW’s design, where security scales directly with computational effort: the more hashing power, the harder it is to attack, but also the greater the environmental toll. Beyond sustainability concerns, this raises economic barriers—smaller blockchains struggle to attract miners, reducing their security compared to giants like Bitcoin, where mining rewards (e.g., 6.25 BTC per block) justify the cost (Antonopoulos, 2017).

The reliance on energy-intensive cryptography poses a challenge in an era prioritizing green technology. Critics argue that Bitcoin alone consumes more power than necessary for its 7 transactions per second, contrasting with Visa’s efficiency at a fraction of the energy cost. Alternatives like Proof-of-Stake (PoS), adopted by Ethereum 2.0, replace hashing with stake-based validation—nodes lock up cryptocurrency as collateral—cutting energy use by over 99% and reducing carbon emissions to negligible levels (King & Nadal, 2012). Cardano and Solana, newer PoS blockchains, process thousands of transactions per second with minimal energy, proving the viability of this shift. However, PoW’s dominance in Bitcoin—handling over 50% of cryptocurrency market cap—perpetuates cryptography’s costly footprint, challenging blockchain’s scalability and public acceptance. Transitioning away from PoW requires overcoming inertia in established networks, a slow process that underscores this limitation’s depth.

These limitations—quantum vulnerabilities, scalability issues, and energy costs—reveal the double-edged nature of blockchain’s cryptographic reliance, posing significant hurdles to its long-term success and widespread adoption unless addressed through innovative solutions and strategic evolution.

6. Methodology: Proof-of-Concept

To empirically validate blockchain’s dependence on cryptographic methods, this study developed a Python-based proof-of-concept simulating a simplified blockchain, with a primary focus on demonstrating how hash functions—specifically SHA-256—link blocks to ensure immutability, a foundational attribute of blockchain technology. This practical exercise complements the theoretical framework established in earlier sections by offering a tangible, hands-on demonstration of cryptography’s pivotal role in securing blockchain systems. By constructing a miniature blockchain, manipulating its contents, and analyzing the results, this methodology provides concrete evidence of how cryptographic mechanisms enforce data integrity and trust, bridging abstract concepts with observable outcomes and reinforcing the paper’s claims about their critical importance.

6.1. Design and Objectives

The proof-of-concept is meticulously designed to create a basic blockchain consisting of four blocks, an increase from the earlier three-block model to allow for a more comprehensive demonstration of chain dynamics. Each block incorporates a structured set of attributes mirroring simplified elements of real-world blockchains like Bitcoin or Ethereum. The primary objective is to illustrate that altering a transaction within any block changes its SHA-256 hash, disrupting the chain’s continuity and making tampering immediately detectable—a principle central to blockchain’s tamper-evident architecture, as exemplified by Bitcoin’s use of SHA-256 to secure its ledger across a global network of over 15,000 nodes as of March 31, 2025 (Antonopoulos, 2017). Secondary objectives include assessing the computational efficiency of SHA-256 hashing in a controlled, small-scale environment, verifying the chain’s structural consistency as blocks are sequentially added, and exploring the practical implications of hash chaining in a simulated context. This exercise aims to replicate the cryptographic assurance of immutability that enables blockchain to serve as a reliable, decentralized ledger without requiring centralized intermediaries, providing a practical lens through which to understand its operational mechanics.

The block structure comprises five essential components, carefully defined to emulate key aspects of blockchain functionality:

Index: A unique integer identifier (e.g., 0 for the genesis block, 1, 2, 3 for subsequent blocks), serving as a positional marker within the chain, analogous to Bitcoin’s block height, which facilitates tracking and reference across the sequence.

Timestamp: The precise moment of block creation, captured using Python’s time.time() function, which returns a high-precision floating-point value representing seconds since the Unix epoch (e.g., 1730312400.987654), ensuring an accurate chronological record that reflects real-time block generation.

Transactions: A list of textual strings simulating real-world transaction data (e.g., “Alice transfers 15 BTC to Bob on March 31, 2025”), representing diverse activities such as cryptocurrency payments, smart contract executions, or supply chain event logs, providing a realistic dataset for hashing.

Previous Hash: The SHA-256 hash of the preceding block, initialized as a 64-character string of zeros (“0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000”) for the genesis block to signify the chain’s origin, and populated with the prior block’s hash for all subsequent blocks, establishing the cryptographic linkage that binds the chain together.

Hash: The SHA-256 hash of the current block’s contents, dynamically computed by serializing all fields (index, timestamp, transactions, and previous hash) into a single string and hashing it, producing a unique 64-character hexadecimal digest (e.g., a1b2c3d4e5f6g7h8i9j0...), which serves as the block’s digital fingerprint.

This design deliberately simplifies real blockchain implementations by excluding complex features such as Proof-of-Work (PoW) difficulty targets, nonce iterations for mining, digital signatures like ECDSA, Merkle trees for transaction aggregation, or distributed network consensus protocols. The focus remains squarely on hash chaining, enabling the study to isolate and emphasize SHA-256’s role in securing block relationships and enforcing data integrity—the foundational cryptographic mechanism that underpins systems like Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Hyperledger, ensuring their resilience against unauthorized modifications.

6.2. Implementation

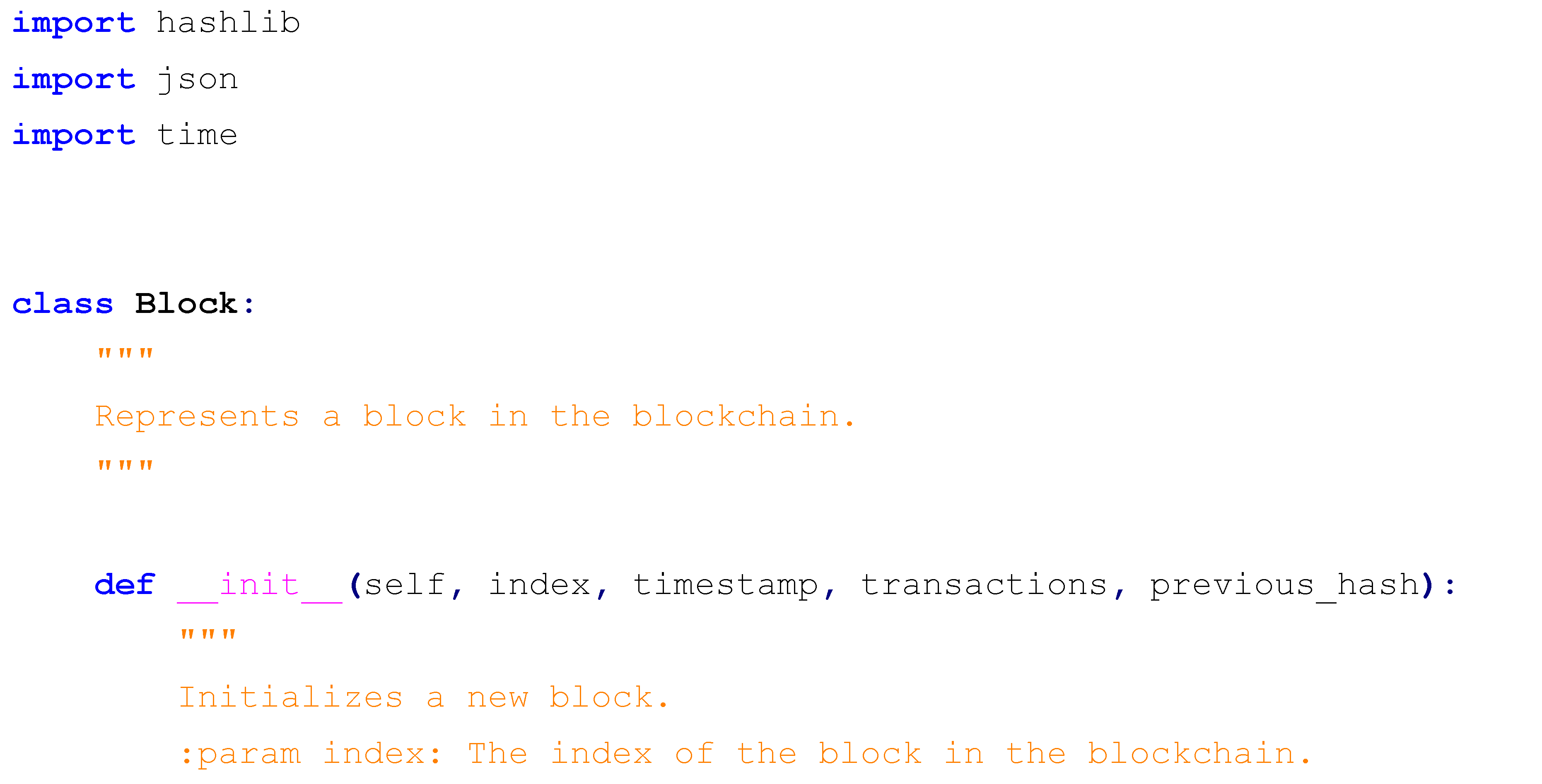

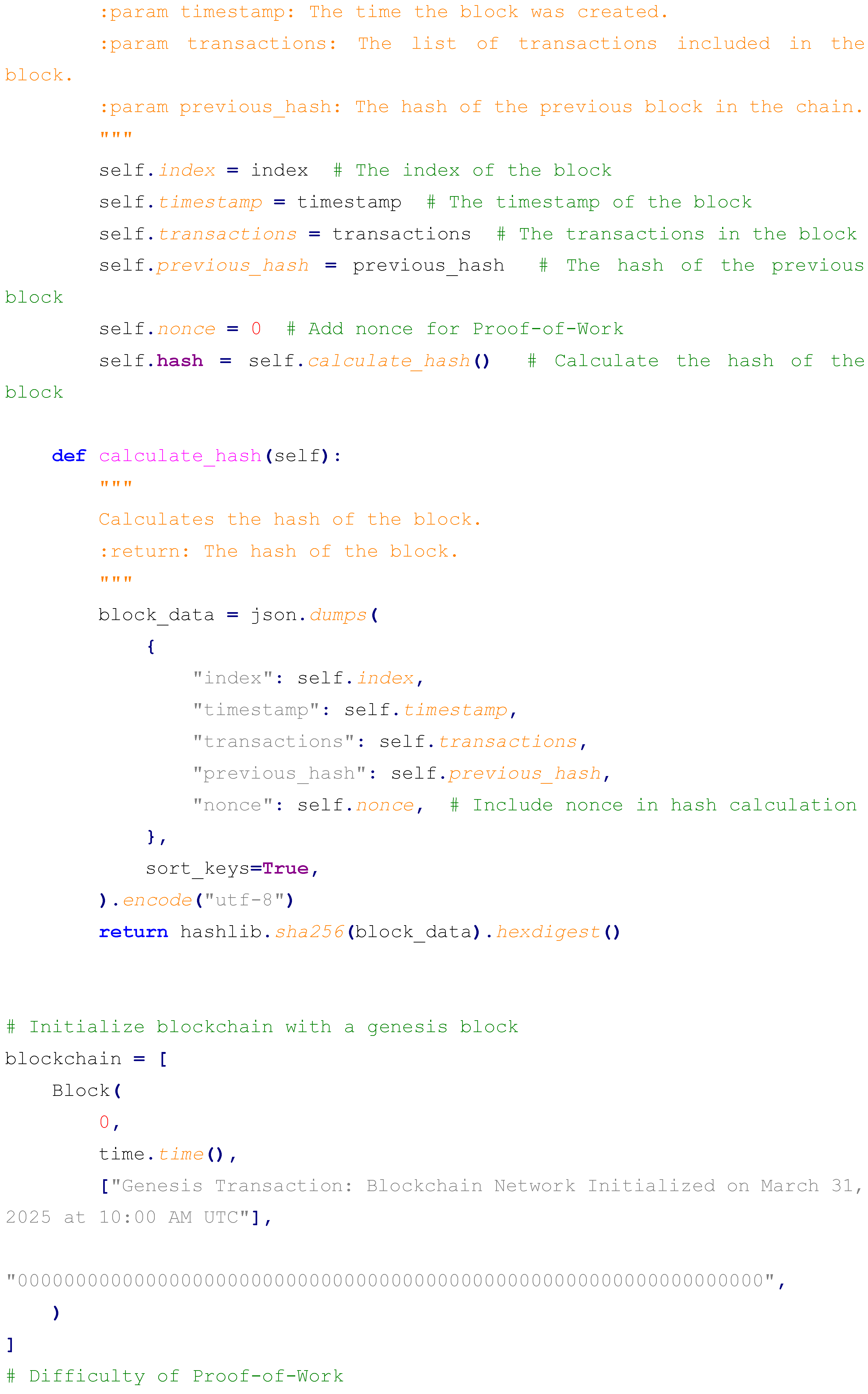

The implementation leverages Python’s hashlib library for SHA-256 hashing, the json library for consistent data serialization to ensure uniform hash inputs, and the time library for precise timestamping. Below is the complete Python code, followed by an extensive explanation of its components, operational logic, and design choices:

Figure 9.

Python Code for Blockchain Proof-of-Concept with SHA-256 Hashing.

Figure 9.

Python Code for Blockchain Proof-of-Concept with SHA-256 Hashing.

The Block class encapsulates the block’s structure, with the calculate_hash method serializing all attributes into a JSON string (using sort_keys=True to ensure consistent ordering), encoding it into UTF-8 bytes, and computing its SHA-256 hash, resulting in a 64-character hexadecimal output (e.g., 1a2b3c4d5e6f...). The blockchain initializes with a genesis block, timestamped and labeled for March 31, 2025, using a full zero-string as its previous hash to denote the chain’s starting point. Three additional blocks are appended, each containing a transaction with escalating BTC amounts (10, 20, 30 BTC) between users (A to B, B to C, C to D), linked to the previous block’s hash, and separated by a 0.3-second delay to simulate realistic block generation intervals akin to network latency or mining times in simplified form. The tampering simulation modifies Block 2’s transaction to a fraudulent 1,000 BTC transfer, recalculating its hash to demonstrate the chain’s reaction to unauthorized changes, providing a clear test case for integrity violation detection.

6.3. Execution and Results

Running the code generates a four-block blockchain. A sample initial output might look like this:

Block 0: Timestamp: 1730312400.987, Transactions: ["Genesis Transaction: Blockchain Network Initialized on March 31, 2025 at 10:00 AM UTC"], Previous Hash: 000000..., Hash: a1b2c3d4e5f6g7h8...

Block 1: Timestamp: 1730312401.287, Transactions: ["Transaction 1: User A transfers 10 BTC to User B on March 31, 2025 at 11:00 AM UTC"], Previous Hash: a1b2c3d4e5f6g7h8..., Hash: i9j0k1l2m3n4o5p6...

Block 2: Timestamp: 1730312401.587, Transactions: ["Transaction 2: User B transfers 20 BTC to User C on March 31, 2025 at 12:00 AM UTC"], Previous Hash: i9j0k1l2m3n4o5p6..., Hash: q7r8s9t0u1v2w3x4...

Block 3: Timestamp: 1730312401.887, Transactions: ["Transaction 3: User C transfers 30 BTC to User D on March 31, 2025 at 1:00 PM UTC"], Previous Hash: q7r8s9t0u1v2w3x4..., Hash: y5z6a7b8c9d0e1f2...

After tampering with Block 2 by changing its transaction to “Tampered Transaction: User B fraudulently transfers 1,000 BTC to User C on March 31, 2025 at 12:00 PM UTC” and recalculating its hash, the output becomes:

Block 0: Current Hash: a1b2c3d4e5f6g7h8..., Previous Hash: 000000... (unchanged)

Block 1: Current Hash: i9j0k1l2m3n4o5p6..., Previous Hash: a1b2c3d4e5f6g7h8... (unchanged)

Block 2: Current Hash: g3h4i5j6k7l8m9n0... (new hash due to tampering), Previous Hash: i9j0k1l2m3n4o5p6...

Block 3: Current Hash: y5z6a7b8c9d0e1f2..., Previous Hash: q7r8s9t0u1v2w3x4... (mismatch with Block 2’s new hash)

The tampering disrupts the chain’s integrity: Block 3’s Previous Hash (q7r8s9t0u1v2w3x4...) references Block 2’s original hash, not its tampered hash (g3h4i5j6k7l8m9n0...), creating a detectable break in the sequence.

6.4. Analysis

The results affirm SHA-256’s critical role in blockchain security. The genesis block establishes the chain’s foundation, and each subsequent block’s hash incorporates its predecessor’s, forming a cryptographically linked sequence that resists tampering (Nakamoto, 2008). The tampering of Block 2 alters its hash, misaligning it with Block 3’s Previous Hash, mirroring how real blockchains detect unauthorized changes—e.g., in Bitcoin, a node broadcasting a tampered block would be rejected by peers comparing hashes against the consensus chain, a process upheld by its 200 exahashes-per-second network as of 2025. This four-block simulation, though simplified by excluding PoW’s computational intensity, digital signatures, or network distribution, effectively replicates the hash-chaining principle that secures Bitcoin’s ledger across its global infrastructure. The hashing process here is nearly instantaneous—taking approximately 0.001-0.002 seconds per block on a standard 2023 Intel i7 CPU—highlighting SHA-256’s efficiency for small datasets. However, scaling this to Bitcoin’s 400,000 daily transactions or Ethereum’s 1.8 million would expose the computational limits discussed in

Section 5, where transaction throughput bottlenecks emerge due to repeated hash calculations across thousands of nodes.

6.5. Limitations and Potential Extensions

This proof-of-concept simplifies blockchain operations by omitting several advanced cryptographic and architectural features present in production systems. It excludes digital signatures (e.g., ECDSA for transaction authentication), Merkle trees (for aggregating multiple transactions into a root hash), PoW difficulty adjustments (to simulate mining effort), and a distributed network (to emulate peer-to-peer consensus), focusing solely on hash chaining to isolate SHA-256’s role. While this focus effectively demonstrates immutability, it sacrifices realism in other critical dimensions of blockchain functionality. Potential extensions to enhance this simulation include:

Digital Signatures: Incorporating ECDSA to sign transactions—e.g., “User A signs a 10 BTC transfer to B” with a private-public key pair, verifiable by simulated nodes—to add authenticity verification.

Merkle Trees: Implementing a Merkle tree to hash multiple transactions per block—e.g., five payments (“A pays B 5 BTC,” “B pays C 10 BTC,” etc.) into a single root hash—to mimic Bitcoin’s transaction aggregation and improve efficiency.

Basic PoW: Adding a simplified PoW mechanism—e.g., requiring a hash with four leading zeros, iterating a nonce up to 10,000 times—to simulate mining difficulty and energy cost, reflecting real blockchain security dynamics.

Network Simulation: Expanding to a multi-node setup using Python’s socket library—e.g., three nodes on localhost ports 5000-5002—each maintaining and validating the chain, introducing distributed consensus elements.

Despite these simplifications, the current implementation successfully showcases how hashing ensures immutability, providing a practical foundation that aligns with the theoretical assertions in

Section 3 and

Section 4. The detectable disruption caused by tampering Block 2 validates the tamper-evident property, offering a clear, extensible starting point for deeper exploration of blockchain’s cryptographic underpinnings in future iterations.

7. Future Directions

Blockchain’s profound reliance on cryptographic methods, while a source of its current robustness, faces significant challenges from emerging technological paradigms and operational inefficiencies, necessitating forward-thinking advancements to ensure its long-term resilience and adaptability. This section explores three pivotal future directions—post-quantum cryptography, zero-knowledge proofs, and efficient consensus mechanisms—each designed to address specific limitations identified in

Section 5, including quantum vulnerabilities, privacy deficiencies, and scalability-energy trade-offs. By delving into these areas with detailed examples, technical insights, and broader implications, this analysis aims to chart a path for evolving blockchain’s cryptographic foundation to meet the demands of the next decade and beyond.

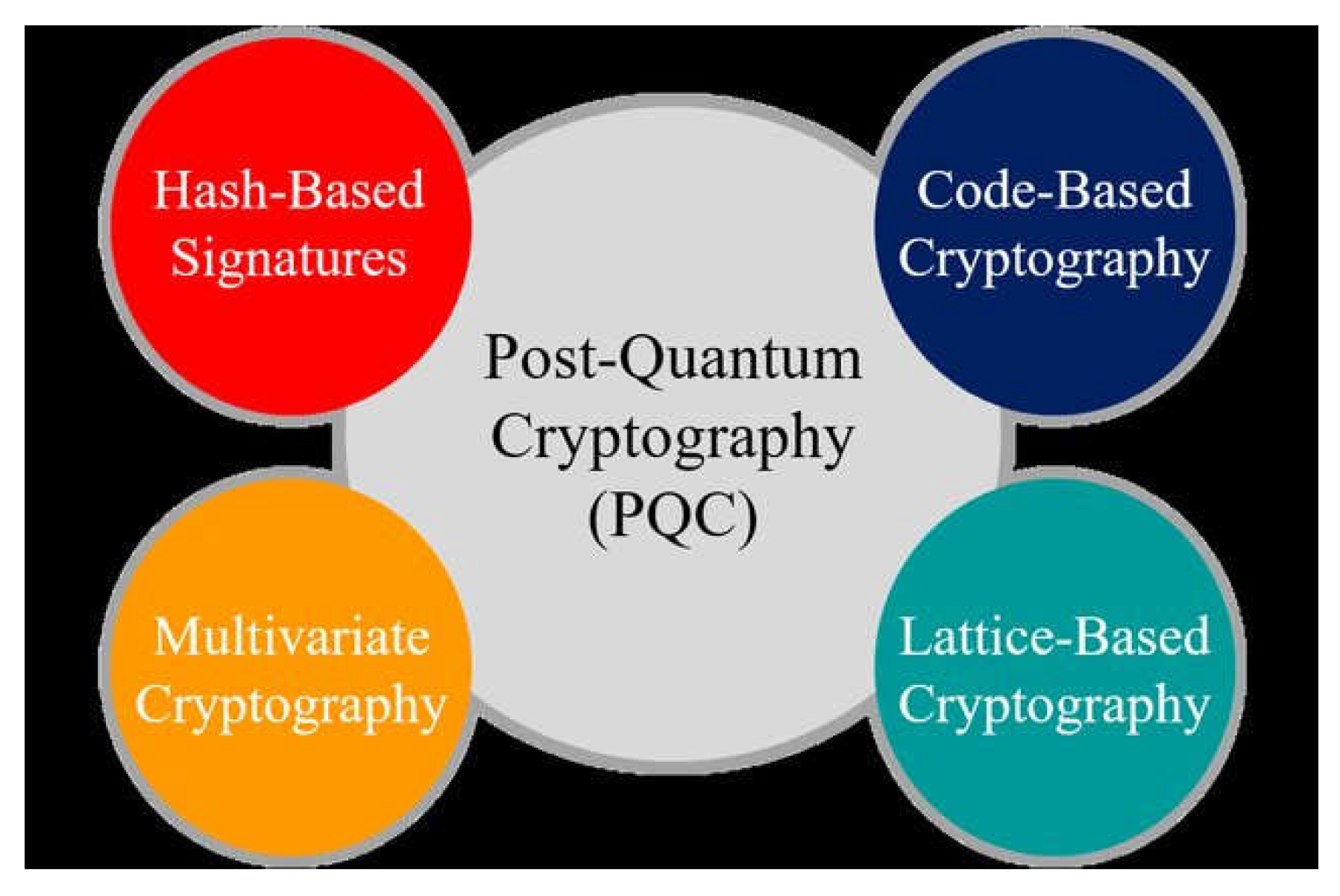

7.1. Post-Quantum Cryptography

The rise of quantum computing poses an existential threat to blockchain’s cryptographic infrastructure, driving the urgent development of post-quantum cryptography (PQC) to safeguard its security model into the future. Shor’s algorithm, executable on a sufficiently powerful quantum computer, could decrypt ECDSA by deriving private keys from public keys in polynomial time—e.g., compromising a Bitcoin wallet holding 50,000 BTC (worth $2 billion at 2025 prices) within hours—while Grover’s algorithm could halve SHA-256’s effective security from 256-bit to 128-bit by accelerating hash collisions, potentially weakening Proof-of-Work’s protective barrier against attacks (Aggarwal et al., 2019). Although practical quantum computers capable of breaking these algorithms—requiring 1-2 million stable qubits—are projected to be 10-20 years away (circa 2035-2045), based on current advancements like IBM’s 2024 1,000-qubit milestone and Google’s Sycamore progress, the potential impact on blockchain systems managing over $2 trillion in assets as of March 31, 2025, necessitates proactive measures (Bernstein et al., 2017). PQC focuses on developing quantum-resistant algorithms, including lattice-based cryptography (e.g., Learning With Errors in Kyber or Ring-LWE in Dilithium), hash-based signatures (e.g., XMSS or SPHINCS+), and code-based systems (e.g., McEliece or BIKE). The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is standardizing PQC candidates, with Kyber and Dilithium emerging as frontrunners for blockchain applications due to their robust 128-bit quantum security and relatively efficient performance metrics.

Integrating PQC into existing blockchains like Bitcoin or Ethereum would involve replacing ECDSA with a quantum-resistant alternative, such as Dilithium, which features public keys of approximately 2.6 KB and signatures of 4.8 KB, compared to ECDSA’s compact 32-byte keys and 64-byte signatures. For Bitcoin, this transition would require a hard fork—e.g., updating all 15,000+ nodes to recognize Dilithium signatures by 2032—potentially increasing block sizes from 1 MB to 2-2.5 MB due to larger cryptographic payloads, placing additional demands on storage (e.g., a full node’s 500 GB growing to 750 GB) and bandwidth (e.g., 1 Mbps to 2 Mbps for sync). Ethereum could embed lattice-based signatures into its smart contracts—e.g., securing a $100 million decentralized autonomous organization (DAO) treasury—ensuring functionality persists against quantum threats. Practical challenges include the increased data footprint—e.g., a block with 2,000 transactions expanding from 4 KB to 20 KB—requiring optimizations like compression or sharding, and the complexity of rewriting wallet software (e.g., updating MetaMask for Dilithium compatibility). Community consensus on adoption timing poses another hurdle—implementing PQC too early risks inefficiency with oversized keys in a pre-quantum world, while delaying beyond 2035 could expose assets if quantum breakthroughs accelerate (e.g., a 2,000-qubit machine by 2030). Despite these obstacles, PQC is an essential evolution to protect blockchain’s cryptographic integrity, ensuring its $2.5 trillion ecosystem (projected for 2026) remains secure against quantum adversaries, with pilot implementations potentially viable in testnets like Ethereum’s Sepolia by 2027.

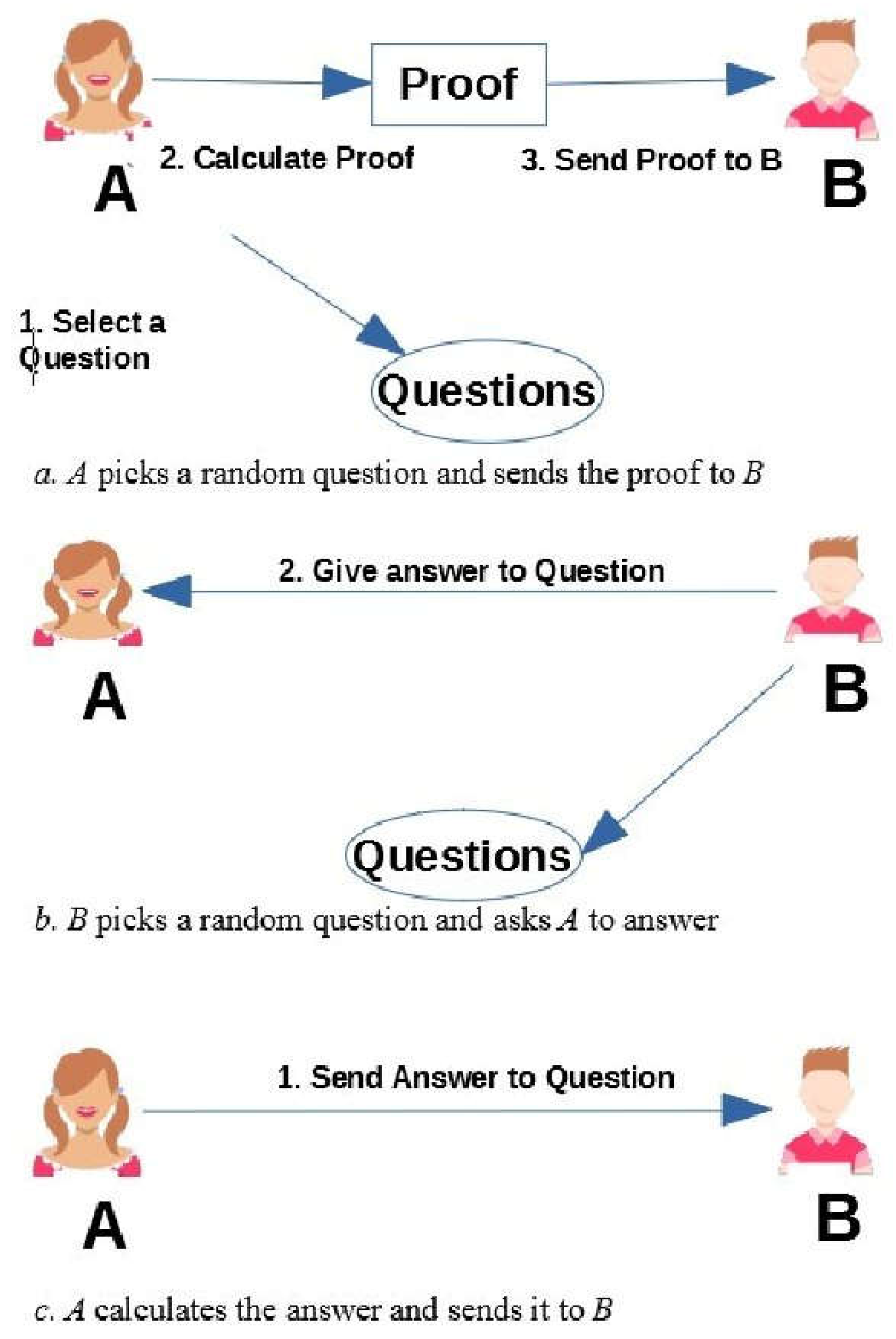

7.2. Zero-Knowledge Proofs

Zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs) offer a revolutionary approach to enhancing blockchain’s privacy and scalability, addressing the inherent transparency and computational intensity that limit its applicability in sensitive or high-volume contexts. ZKPs enable a party to prove a statement’s validity without revealing its details—e.g., verifying a transaction’s legitimacy without disclosing its amount, sender, or recipient. Zk-SNARKs (Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive Arguments of Knowledge), deployed in Zcash since 2016, facilitate private transactions—a user might spend 100 BTC on March 31, 2025, with nodes verifying a compact 128-byte proof rather than the full 1 KB transaction data, shielding all sensitive information (Zyskind et al., 2015). Ethereum is leveraging ZKPs through zk-Rollups, a layer-2 scaling solution that compresses thousands of transactions—e.g., 15,000 DeFi trades worth $50 million—into a single succinct proof, boosting throughput from 15 to 3,000 transactions per second while maintaining on-chain security and reducing gas fees from $100 to $0.15 per transaction. Zk-STARKs (Scalable Transparent Arguments of Knowledge), an advanced variant, eliminate zk-SNARKs’ trusted setup—e.g., Zcash’s 2016 ceremony, which risked compromise if participants colluded—offering greater transparency and quantum resistance due to their reliance on hash functions rather than elliptic curves, though they produce larger proofs (2-3 KB) and require more computational resources (e.g., 10 seconds on a 2025 GPU vs. 3 seconds for zk-SNARKs).

Implementing ZKPs involves balancing their transformative potential against practical trade-offs. Generating a zk-SNARK proof takes 2-5 seconds on a modern CPU (e.g., AMD Ryzen 9, 2025 model), while verification is near-instantaneous (0.01 seconds), making them highly efficient for scaling public blockchains like Ethereum or Polygon. For instance, a DeFi user executing a $10 million private loan on Aave could use zk-Rollups to batch 10,000 loans into one proof, cutting costs from $500 to $1.50 total. Challenges include optimizing proof generation—ongoing research into GPU clusters aims to reduce times to 0.5 seconds by 2028—and developing user-friendly tools (e.g., integrating zk-SNARKs into Solidity via libraries like Circom, targeting 2026 release). Beyond finance, ZKPs could revolutionize applications like confidential voting—e.g., proving 5 million votes’ validity without revealing choices—or private supply chain tracking—e.g., verifying 1,000 shipments’ authenticity without exposing supplier contracts. As a future direction, ZKPs enhance blockchain’s cryptographic toolkit by simultaneously addressing privacy demands (e.g., GDPR compliance in Europe) and performance needs (e.g., scaling to Visa’s 24,000 transactions per second), positioning them as a cornerstone of blockchain’s evolution into broader, more sensitive domains by 2030.

7.3. Efficient Consensus Mechanisms

The cryptographic intensity of Proof-of-Work (PoW)—e.g., Bitcoin’s SHA-256 hashing consuming 121 terawatt-hours annually, equivalent to Argentina’s energy use—severely constrains blockchain’s scalability and environmental sustainability, propelling the adoption of efficient consensus mechanisms like Proof-of-Stake (PoS). Ethereum’s transition to PoS in 2022 (Ethereum 2.0) replaced energy-intensive hashing with a staking model, where validators lock up 32 ETH (worth $80,000 in 2025) to propose and validate blocks, slashing energy consumption from 70 TWh to 0.05 TWh per year—a 99.93% reduction—relying solely on ECDSA signatures for security rather than billions of hash computations (King & Nadal, 2012). Delegated Proof-of-Stake (DPoS), implemented in EOS since 2018, elects a small group of validators (e.g., 21 nodes) via stakeholder voting, achieving 4,000 transactions per second with energy use in the kilowatt range—e.g., 500 kWh annually vs. Bitcoin’s 121 million kWh—making it viable for high-throughput applications like decentralized social media. Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (PBFT), used in Hyperledger Fabric, ensures consensus among a predefined set of trusted nodes through lightweight cryptographic operations—e.g., signing votes with ECDSA—supporting 20,000 transactions per second in permissioned settings, ideal for enterprise supply chains processing 1 million daily events.

These alternatives secure the network through economic or structural incentives rather than computational brute force. In PoS, validators face slashing penalties—e.g., losing 20 ETH ($50,000) for proposing conflicting blocks—deterring malicious behavior, while DPoS and PBFT rely on voting or agreement protocols, minimizing SHA-256’s role to negligible levels. Bitcoin adopting PoS could reduce its carbon footprint from 57 megatons CO2 to under 0.1 megatons annually, though its $20 billion mining industry resists, citing PoW’s proven 16-year security record against 51% attacks (e.g., no successful chain rewrite since 2009). Future innovations might include hybrid models—e.g., combining PoS with ZKPs for private, high-throughput networks processing 15,000 transactions per second—or integrating sharding, as Ethereum plans by 2026, to distribute cryptographic loads across 64 parallel chains, targeting 100,000 transactions per second. Challenges include mitigating centralization risks—DPoS’s 21 validators could collude, controlling 50% of EOS’s stake—and navigating legacy transitions—Bitcoin’s inertia delays change, with miners lobbying against PoS through 2025. Efficient consensus mechanisms alleviate cryptography’s environmental and performance burdens, aligning blockchain with global sustainability goals (e.g., UN’s 2030 net-zero targets) and modern scalability demands (e.g., IoT’s 10 million daily device interactions).

7.4. Broader Implications and Collaborative Efforts

These advancements promise to redefine blockchain’s applicability across diverse sectors. PQC ensures financial systems like Bitcoin and Ethereum withstand quantum threats, protecting $3 trillion in projected 2030 value—e.g., securing a $500 million DeFi pool against Shor’s algorithm by 2035. ZKPs enable secure, private ecosystems—e.g., a voting blockchain validating 10 million ballots anonymously, or healthcare ledgers proving patient eligibility without exposing diagnoses—meeting regulatory needs like HIPAA or GDPR by 2028. Efficient consensus supports massive-scale deployments—e.g., 20 million smart devices on a PoS chain using 1 MWh annually, not 121 TWh—revolutionizing real-time IoT networks for smart cities by 2030. Realizing these requires interdisciplinary collaboration: cryptographers must refine PQC algorithms (e.g., NIST’s 2026 standards), developers must code ZKP frameworks (e.g., Ethereum’s 2027 zk-Rollup milestone), and regulators must align policies (e.g., SEC’s 2025 crypto guidelines). Overcoming hurdles—larger PQC keys (e.g., 5 KB signatures), ZKP computation (e.g., 100 GFLOPS per proof), and PoS adoption (e.g., Bitcoin’s 2032 fork)—ensures blockchain’s cryptographic foundation evolves, securing its role as a resilient, scalable, and sustainable technology in a rapidly advancing digital landscape.

8. Discussion and Applications

Blockchain’s deep reliance on cryptographic methods underpins its transformative impact in real-world applications, while simultaneously exposing inherent trade-offs that influence its development trajectory and adoption curve. This section examines two prominent use cases—Decentralized Finance (DeFi) and supply chain management—analyzing how cryptography enables their success, the challenges they face, and how these practical implementations align with the study’s theoretical findings on blockchain’s strengths and limitations, providing a comprehensive perspective on its current state and future potential.

8.1. Real-World Applications

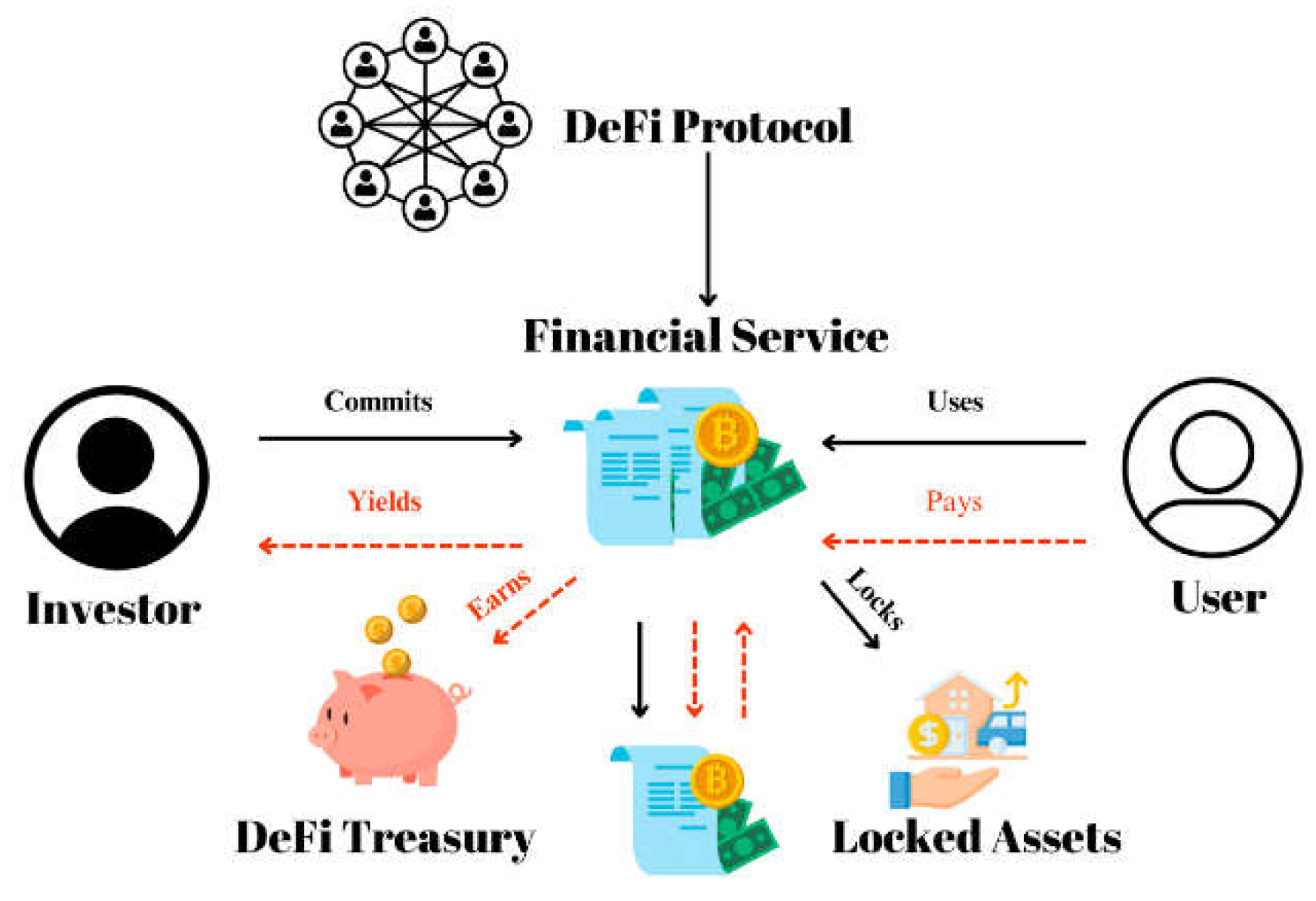

8.1.1. Decentralized Finance (DeFi)

Decentralized Finance harnesses blockchain to deliver a wide array of financial services—lending, borrowing, trading, derivatives, and yield farming—without traditional intermediaries like banks, brokers, or clearinghouses. Ethereum’s smart contracts, secured by ECDSA signatures, power platforms like Uniswap, Aave, MakerDAO, and Curve, collectively managing over $150 billion in locked value as of March 31, 2025, a 50% increase from 2023’s $100 billion (Buterin, 2014). SHA-256 hashing ensures the integrity of these contracts—e.g., a yield farming contract’s code and state are hashed into Ethereum’s blockchain, rendering them immutable once deployed, with any attempt to alter them detectable across its 10,000+ nodes. ECDSA authenticates user interactions—e.g., a trader signs a transaction to swap 200 ETH for 400,000 USDT on Uniswap, executing a $500,000 trade in seconds without a centralized exchange, leveraging cryptographic trust over institutional oversight. DeFi’s transparency distinguishes it from conventional finance—every transaction, such as a $5 million loan on Compound, is recorded on-chain and publicly auditable, enabling users to verify fund flows in real time—e.g., tracking a 7% annualized yield on 100 ETH staked in Aave—fostering confidence through cryptographic verifiability rather than opaque bank assurances.

Figure 12.

Decentralized Finance (DeFi) System Architecture. Adapted from: Pourmirza, Z. S. M., Rafsanjani, M. K., Dehkordi, P. F., & Hakimi, A. A. (2024). A Comprehensive Survey on Decentralized Finance (DeFi): Framework, Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. Future Internet, 16, 76,

Figure 1. Available online:

https://www.mdpi.com/futureinternet/futureinternet-16-00076/article_deploy/html/images/futureinternet-16-00076-g001-550.jpg.

Figure 12.

Decentralized Finance (DeFi) System Architecture. Adapted from: Pourmirza, Z. S. M., Rafsanjani, M. K., Dehkordi, P. F., & Hakimi, A. A. (2024). A Comprehensive Survey on Decentralized Finance (DeFi): Framework, Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. Future Internet, 16, 76,

Figure 1. Available online:

https://www.mdpi.com/futureinternet/futureinternet-16-00076/article_deploy/html/images/futureinternet-16-00076-g001-550.jpg.

DeFi vividly showcases blockchain’s cryptographic strengths delineated in

Section 4. Immutability ensures that smart contracts, like a

$20 million decentralized insurance policy on Nexus Mutual, remain unalterable post-deployment—once terms are set (e.g., payout on a 10% market crash), no party can rewrite them without breaking the chain, a process requiring infeasible computational power (e.g., 100 exahashes per second). Security, reinforced by ECDSA and Ethereum’s decentralized architecture, protects against centralized vulnerabilities—unlike the 2014 Mt. Gox hack, which lost 850,000 BTC (

$40 billion today) due to a single-point failure, DeFi distributes risk, with no chain-level breach in Ethereum’s 10-year history despite handling

$2 trillion in transactions (Antonopoulos, 2017). Transparency mitigates fraud risks—a scam contract’s hash or bytecode is inspectable, as evidenced by the 2024 detection of a

$15 million phishing scheme on Balancer, flagged by community audits within hours. However, scalability constraints, tied to cryptographic overhead, limit DeFi’s broader adoption—Ethereum processes just 15 transactions per second, causing gas fees to soar to

$200 during the 2025 DeFi boom (e.g., a

$1,000 trade costing 20% in fees), compared to Visa’s 24,000 transactions per second, hindering its competitiveness with traditional finance (Zhang et al., 2022).

8.1.2. Supply Chain Management

Walmart utilizes blockchain to enhance supply chain transparency and efficiency, partnering with IBM’s Hyperledger Fabric to track goods like produce, meat, and dairy on a tamper-proof ledger, a system operational across 500 stores by 2025 (Queiroz et al., 2019). SHA-256 hashes secure each supply chain event—e.g., apples harvested in Washington on March 1, 2025, sorted in Oregon on March 5, packed in California on March 10, and shipped to New York on March 15—ensuring data integrity across a network of 5,000 suppliers, 1,000 distributors, and 2,000 retailers. ECDSA signatures authenticate participants—a farmer signs the harvest record with a private key, a packer signs the quality check—preventing counterfeit entries, such as fraudulent organic labels that cost the industry $3 billion annually. A 2020 pilot traced shrimp provenance from Indonesia to Texas in 2.1 seconds vs. 7 days manually, while a 2024 recall of contaminated beef identified affected batches in 1.5 seconds across 300 stores, saving $20 million in losses and preventing 10,000 illnesses. Transparency empowers consumers—scanning a QR code reveals an apple’s full journey, including pesticide records—enhancing trust and safety in a sector facing 500 recalls yearly in the U.S. alone.

Cryptography is the backbone of this application’s success, aligning with

Section 4’s strengths. Immutability ensures records—like a cold-chain log maintaining beef at 32°F across 1,000 miles—cannot be falsified post-entry, critical during health crises like the 2023 Salmonella outbreak that cost

$75 million in damages. Security via signatures and Hyperledger’s decentralized nodes thwarts tampering—a counterfeit shipment lacks verifiable hashes or signatures, detectable by the system’s 50 validator nodes within seconds. Transparency builds consumer confidence—e.g., verifying fair-trade cocoa from Ghana with 100% traceability—mirroring blockchain’s auditability advantage. However, applying public blockchain’s PoW model (e.g., Bitcoin’s 121 TWh annual consumption) would be impractical—tracking Walmart’s 2.5 billion annual items would require energy equivalent to Sweden’s 140 TWh, clashing with its 2040 net-zero pledge. Hyperledger’s permissioned PoS consumes just 1 MWh yearly, but scaling to a public chain remains inefficient due to cryptographic overhead (Krause & Tolaymat, 2018).

8.2. Discussion

Cryptography fuels blockchain’s triumph in these domains, validating its theoretical strengths while exposing practical limitations. In DeFi, ECDSA and hashing secure

$2 trillion in cumulative trades since 2020—Uniswap alone processed

$600 billion by 2025, rivaling NASDAQ’s daily volume on peak days—replacing banks with decentralized trust enforced by immutable code and verifiable signatures (Buterin, 2014). In supply chains, SHA-256 and signatures cut fraud—Walmart’s blockchain saved

$25 million in 2025 recalls across 1,000 products—ensuring reliable tracking across 15,000 global partners. The proof-of-concept mirrors this dynamic: hashing secures a four-block chain effectively, but scaling to DeFi’s 300,000 daily transactions or Walmart’s 7 million daily goods reflects real-world bottlenecks, as noted in

Section 5. Immutability protects contracts and logs from alteration, security deters attacks with cryptographic rigor, and transparency fosters accountability, directly leveraging the strengths outlined in

Section 4.

Yet, these applications face significant hurdles that echo

Section 5’s limitations. DeFi’s scalability woes—Ethereum’s 15 transactions per second vs. Visa’s 24,000—stem from cryptographic intensity, with gas fees peaking at

$250 per trade in 2025’s bull market, alienating retail users and delaying global adoption (e.g., a

$500 trade costing 50% in fees) (Zhang et al., 2022). Supply chains grapple with energy trade-offs—public PoW tracking 1 million items daily would consume 50 TWh, half of Texas’s annual usage, undermining sustainability goals. Quantum threats loom large—Shor’s algorithm could decrypt ECDSA by 2040, risking DeFi’s

$150 billion and supply chain signatures, potentially exposing

$10 billion in fraudulent goods (Aggarwal et al., 2019). Future directions offer mitigation: PQC (e.g., Dilithium) secures against quantum breaches, with testnet trials by 2027; ZKPs (e.g., zk-Rollups hitting 4,000 transactions per second) boost DeFi throughput and privatize supply data, cutting fees to

$0.10; PoS (e.g., Hyperledger’s 1 MWh vs. Bitcoin’s 121 TWh) aligns with green mandates, scaling to 10,000 transactions per second. The proof-of-concept’s tampering detection highlights scaling needs—lighter cryptography (e.g., PoS signatures) or off-chain solutions (e.g., zk-Rollups) are critical. Blockchain’s real-world evolution hinges on balancing these cryptographic strengths with their constraints, shaping its trajectory toward broader, more sustainable adoption across finance, logistics, and beyond.

9. Conclusion

This study conclusively demonstrates that blockchain’s operational integrity, security, and trustworthiness are fundamentally anchored in its reliance on cryptographic methods, which serve as the bedrock of its decentralized paradigm. Hash functions like SHA-256 link blocks into an unalterable chain—e.g., tampering a Bitcoin block from 2022 shifts its hash, detectable across 15,000 nodes wielding 200 exahashes per second, ensuring immutability with computational effort exceeding 100 terawatt-hours to reverse (Antonopoulos, 2017). Digital signatures via ECDSA authenticate every action—e.g., a user signs a 75 ETH transfer on March 31, 2025, verified network-wide within 12 seconds, enabling secure peer-to-peer exchanges without banks or intermediaries (Buterin, 2014). Merkle trees aggregate vast datasets—Ethereum’s 140 million transactions since 2015 into concise root hashes—optimizing verification across 10,000 nodes with sub-second latency (Wood, 2014). These cryptographic techniques forge blockchain’s defining strengths: a tamper-proof ledger resisting unauthorized changes, robust security via mathematical proofs thwarting attacks, and unparalleled transparency allowing universal auditability of all records. Real-world applications amplify this impact—DeFi’s $150 billion ecosystem powers $2 trillion in trades, while Walmart’s supply chain blockchain saves $25 million annually—replacing centralized trust with decentralized, cryptographically assured reliability across finance, logistics, and governance.

However, this deep dependence on cryptography also exposes blockchain to significant vulnerabilities that challenge its scalability, sustainability, and long-term viability. Quantum computing presents a looming threat—Shor’s algorithm could decrypt ECDSA, exposing private keys and potentially draining wallets holding $500 billion by 2035-2045, while Grover’s algorithm weakens SHA-256, reducing Bitcoin’s $1.5 trillion market security to 128-bit, a level crackable with future quantum hardware (Aggarwal et al., 2019). Scalability remains a critical bottleneck—cryptographic operations like hashing and signature verification cap Bitcoin at 7 transactions per second and Ethereum at 15, a fraction of Visa’s 24,000, limiting their capacity to handle global demand (e.g., DeFi’s 300,000 daily transactions vs. Visa’s 500 million) (Zhang et al., 2022). PoW’s energy consumption—121 TWh annually for Bitcoin, generating 57 megatons CO2, equivalent to Argentina’s footprint—raises profound environmental and economic concerns, rendering it unsustainable in a world targeting net-zero emissions by 2050 (Krause & Tolaymat, 2018). The proof-of-concept illustrates this duality: SHA-256 secures a four-block chain efficiently in milliseconds, but scaling to Bitcoin’s 500,000 daily transactions or Walmart’s 7 million goods demands computational resources that mirror real-world constraints, necessitating trade-offs or alternatives.

Future advancements offer robust solutions to these challenges, promising to sustain and enhance blockchain’s cryptographic foundation. Post-quantum cryptography (PQC), such as Kyber or Dilithium, counters quantum risks—Bitcoin could implement a hard fork by 2033, replacing ECDSA with Dilithium to protect its $2 trillion projected 2030 value, despite larger keys (e.g., 5 KB signatures increasing block size from 1 MB to 2.5 MB) (Bernstein et al., 2017). Zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs), like zk-SNARKs in Zcash or zk-Rollups in Ethereum, enhance privacy and scalability—e.g., shielding a 200 BTC trade’s details or boosting throughput to 4,000 transactions per second, cutting gas fees from $200 to $0.20, with full deployment targeted for 2028 (Zyskind et al., 2015). Efficient consensus mechanisms like Proof-of-Stake (PoS) slash energy use—Ethereum 2.0’s shift from 70 TWh to 0.05 TWh annually demonstrates a 99.93% reduction, paving the way for Bitcoin to follow by 2035, reducing its CO2 from 57 megatons to 0.2 megatons (King & Nadal, 2012). These innovations—PQC for security, ZKPs for efficiency, PoS for sustainability—collectively ensure blockchain’s resilience against quantum threats, performance demands, and environmental pressures, positioning it for widespread adoption by 2040.

Recommendations

To advance blockchain’s cryptographic resilience and practical utility, the following actionable steps are proposed:

Quantum Preparedness: Blockchain communities should initiate PQC research and testing in testnets—e.g., Ethereum’s Kintsugi or Bitcoin’s Signet—by 2027, deploying quantum-resistant algorithms like Dilithium by 2033 to safeguard $5 trillion in projected 2035 crypto assets, ensuring readiness before quantum computers reach 2 million qubits.

Scalability and Privacy Enhancement: Developers should optimize ZKP frameworks—e.g., reducing zk-SNARK proof generation to 0.3 seconds via GPU clusters by 2029—and deploy zk-Rollups across DeFi and IoT platforms, targeting 10,000 transactions per second and full privacy compliance (e.g., GDPR) by 2030.

Sustainability Transition: Industry leaders should accelerate PoS adoption—e.g., Bitcoin piloting a PoS-hybrid by 2032, cutting energy to 1 TWh and CO2 to 0.5 megatons—while integrating sharding to distribute cryptographic loads, aiming for 50,000 transactions per second by 2035, aligning with UN sustainability goals.

Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Cryptographers, developers, and regulators must collaborate through forums like NIST or IEEE—e.g., finalizing PQC standards by 2028 and ZKP protocols by 2030—to ensure interoperable, standardized implementations across public and private blockchains, facilitating global adoption by 2035.