1. Introduction

The global scientific community remains active to achieve a world free from the burden of neglected tropical diseases (NTD)[

1]. Hepatitis B is one of the most common infections and represents a significant public health problem nationally and globally, due to its high morbidity and mortality. In 2019, hepatitis B resulted in about 820,000 deaths, mainly from cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (primary liver cancer) [

2]. An average of 1.3 million people died from viral hepatitis in 2022, and along with tuberculosis is the second cause of death in the classification of communicable diseases in 2022, after COVID 19 [

3].

In Brazil, the Ministry of Health (MoH) estimates that the population living with hepatitis B virus (HBV) exceeds 1 million people [

4]. It is based that the most usual forms of hepatitis B transmission occur through percutaneous exposure, with the use of contaminated materials such as needles, syringes, vertical (mother-child) and sexual (unprotected sex and multiple partners), being considered a sexually transmitted infection [

5].

Efforts aimed at banning viral hepatitis are increasingly needed, as well as improvements in access to information [

6]. Similarly, in a study on hepatitis B, C and D in the Eastern Amazon, a higher prevalence was observed among Amerindians, allegedly due to the adversities of obtaining health services [

7].

In the State of Amapá, according to the MoH Epidemiological Bulletin of June 2022, the number and rate of detection of confirmed occurrences of hepatitis B per 100,000 inhabitants in the years 2000 to 2023 are 651 cases and 455 confirmed cases of hepatitis C in the same period [

8]. Thus, the increase in cases of hepatitis indicate that prevention actions and planning should be expanded and prioritize vulnerable populations, considering regional differences in the State.

Therefore, prevention, early diagnosis and the guarantee of access to appropriate treatment are essential for reducing the burden of these diseases, and the continuous development of research, as well as, the awareness of the population are essential to proceed in the eradication of these diseases, achieving a quality of life of affected individuals is a crucial point. Considering the community health problem that viral hepatitis represents, the objective of this study is describing the epidemiological aspects associated with cases of viral hepatitis B and C, attended in a reference center for Tropical Diseases in a State of the Northern Region of the Brazilian Amazon.

2. Materials and Methods

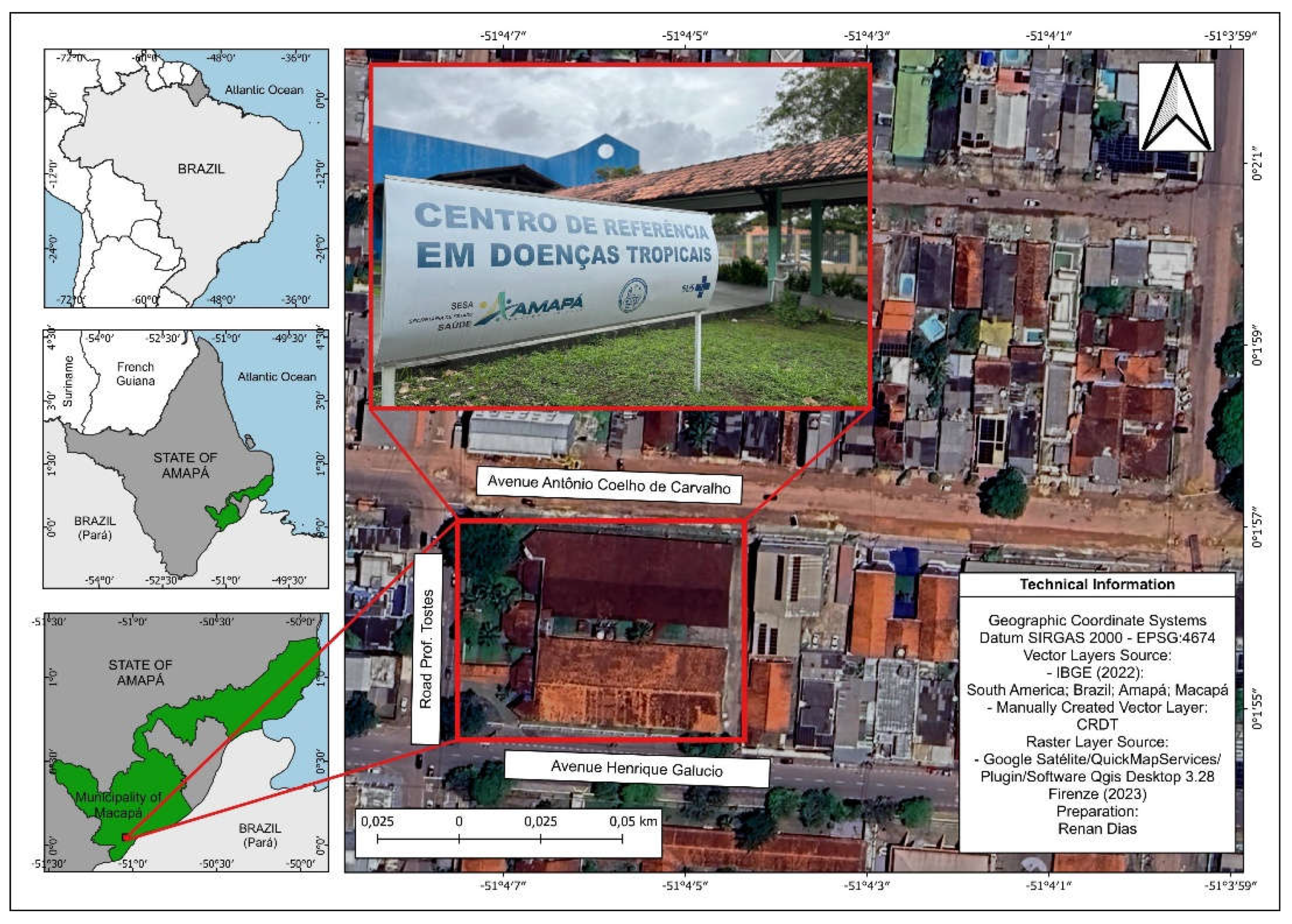

The study was carried out in the State of Amapá, municipality of Macapá, in a reference center for tropical diseases, a State institution linked to the State Secretariat of Health of Amapá (SESA). The State has a territorial unit area of 142,470.762 km2, estimated population of 802,837 people, Human Development Index (HDI) 0.688 and has 16 municipalities, the Capital State of Macapá, cut by the equator with an estimated population of 487,200 people [

9].

The State boundaries are: North: French Guiana, limits to the Northeast: Suriname, East: Atlantic Ocean, South and West: State of Pará, separated by the great Amazon river, its highest point by the Tumucumaque Mountain (701m) according to the Amapá agency, considered as the last frontier of the Country. Despite the geographical barriers, the State has an enchanting beauty by the rustic nature, the way of life of the people and their characteristic culture [

10].

A descriptive, exploratory study with quantitative approach was carried out, where the characterization of the studied population was pointed out, in order to reveal the possible relationships between the variables. In research with a quantitative approach, the collection of quantitative or numerical data is carried out using measurements of quantities that generate masses of data, allowing their analysis through mathematical techniques [

11].

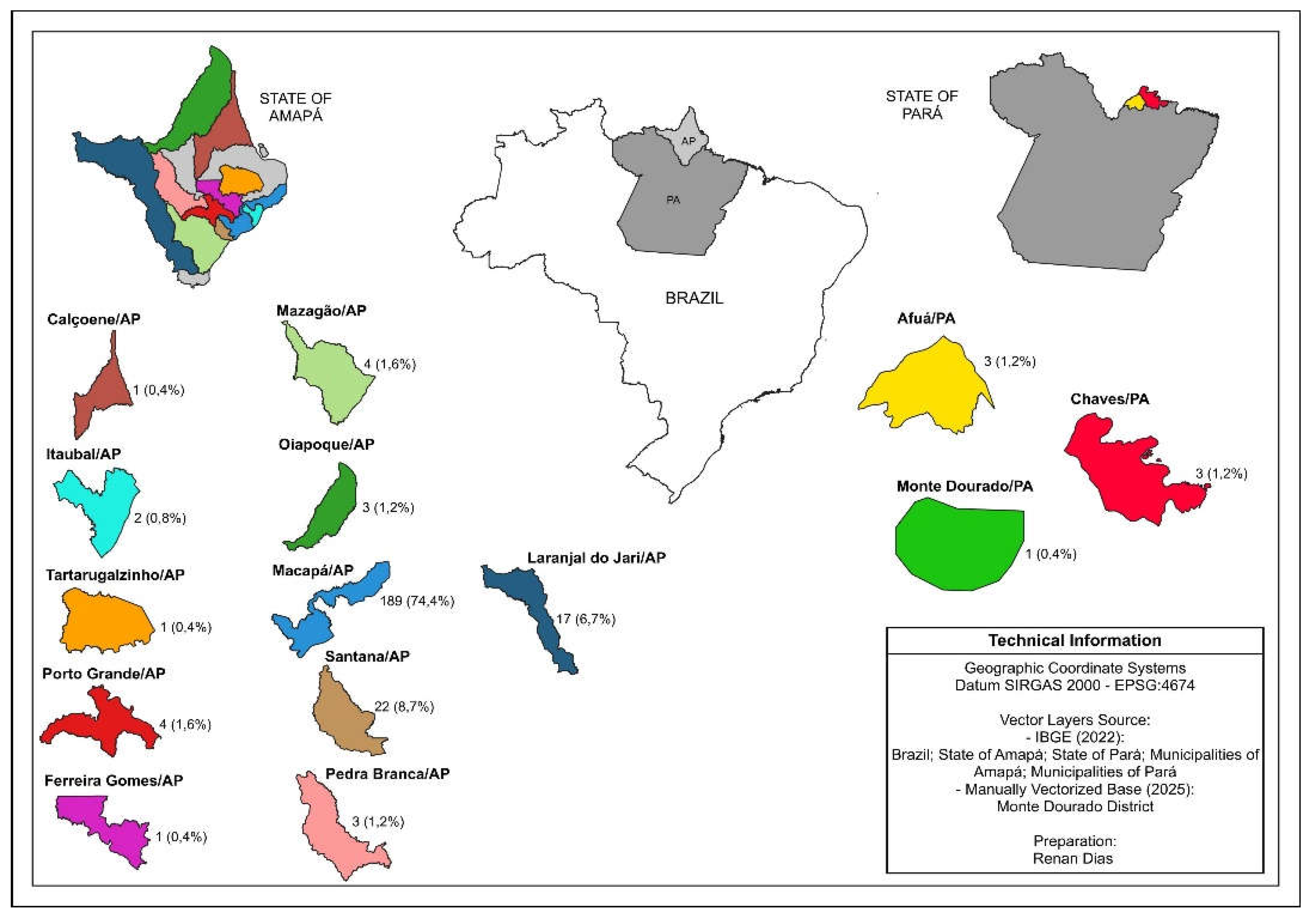

The scenario of the study was in a center of reference in tropical diseases located in the Capital State of Macapá (

Figure 1), it is intended for health care in the care of tropical and infectious diseases in the areas of Dermatology, Infectology, General Pulmonology and Pediatric Pneumology. It is the only reference center for the diagnosis and treatment of these diseases, serves free demand from the State and patients from other municipalities mainly as Afuá and Breves belonging to the State of Pará.

The data collection took place in the first and second quarter of 2024, through the search in medical records, national information bulletin, Notifiable Diseases Information System (SINAN) in the period from 2013 to 2023 totaling ten years retrospectively, the following variables were collected: age, sex, municipality of residence, tests performed, diagnosis with etiological classification of B and C viruses, beginning of treatment, comorbidities, liver transplantation and coinfection.

The composition of the population was for patients of both genders, aged over 18 years old, affected by hepatitis B and C seen in the CRDT. For the research on medical records in the study period, 600 records of patients with hepatitis B and C were considered for the sample calculation, a simple random sample with a sampling error of 5%, and 240 records were needed to compose the sample of the survey.

The analysis was elaborated from the data collection to which a table was built in the Excel 2019 program and imported into the statistical software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26. Simple descriptive statistics techniques were used, from the tabulation, data processing, of the variables submitted to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test to verify if they were suitable for parametric tests, Qui-association test Pearson square to detect associations between the variables sex and etiological classification.

Strengthening the study on viral hepatitis is essential, because this agrave still promote adversities in public health, moreover, shows repercussions not only in the individual’s life, but in the family, as it generates costs and uncertainties, often because the residence is in municipalities of the State with difficult access to the capital for follow-up consultations, as well as to the public system with specialized consultations and high-cost examinations for diagnosis.

The research comes from a master’s dissertation, met the recommendations of the NHC Resolution N 466/2012 MoH. With the obtaining of the consent of the institution’s management, the data collection began-from the approval of the project by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Amapá (UNIFAP), under the CAAE 77341624.5.0000.0003 and Opinion 6.673.389.

3. Results

There were 254 cases of viral hepatitis, a higher proportion for males 53.1% (135/254), with age range of 20 - 59 years old 71.7% (182/254) of the cases, with schooling for high school 44.8% (94/254), with the origin of cases from the public health network 77.4% (185/254). Only 3.8% (8/254) of the sample reported smoking and 8.1% (17/254) drinking alcohol. About 2.8% (7/254) of the sample analyzed were pregnant women (

Table 1).

About 84.6% (215/254) of the sample is made up of residents in the metropolitan Region of Amapá, compared to the inland areas 15.4% (39/254). Thus, due to the reference is located in the capital Macapá and the assistance is still centralized, the State presents peculiarities of access to the capital, in this way, the municipality has higher records of cases of viral hepatitis with 74.4% (189/254) cases (

Figure 2).

In the clinical variables, 52.4% (133/254) presented etiological classification type C, while 47.2% (120/254) are classified as B and only 0.4% (1/254) for B/C. Regarding coinfection, 17.5% (44/254) of the sample presented some type of coinfection. For the comorbidities, about 41.7% (106/254) presented comorbidity associated with hepatitis. Regarding the liver transplant variable, the prevalence of patients who needed to proceed with transplantation was 1.6% (4/254) (

Table 2).

The diagnosis was confirmed by laboratory criteria with an anti-HCV test of 52.8% (133/252) and a reactive result. For the C virus (CV-HCV) viral load test, 92.6% (126/136) presented detectable results, as well as 46.5% (118/254) for HBsAG. In the B virus (CV-HBV) viral load test, 79.8% (99/124) obtained detectable result. In the Anti HBc Total test, 24.5% (62/253) result was reactive with a high prevalence of patients who did not take the test 68.4% (173/253) (

Table 3).

Additionally, antibody testing against the surface antigen of hepatitis B (Anti-HBs) indicated that 8.3% (21/253) presented a reactive result and 62.5% (158/253) did not perform the collection. In the Anti- HDV examination, 1.5% (2/130) presented a reagent result with high prevalence of patients who did not take the test 82.3% (107/130). The Anti-HAV examination did not register patients with a reactive result, but it obtained a percentage of 91.3% (231/253) who did not perform this examination (

Table 3).

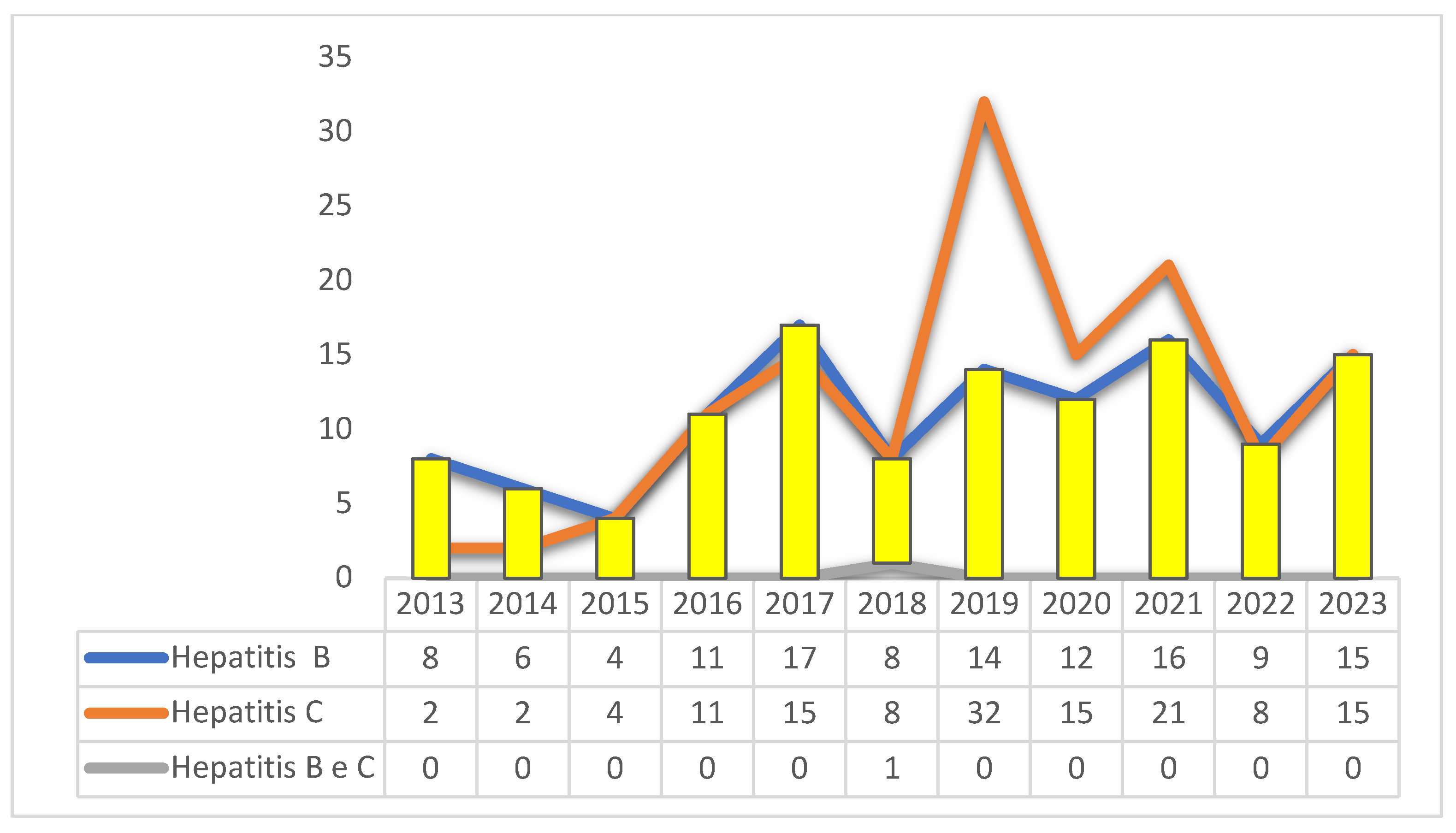

With regard to the distribution of cases of viral hepatitis according to temporal distribution and treatment initiation with higher frequencies for the year 2019 with 18.1% (46/254), being in accordance with the etiological classification between B, C and B and C (Graphic 1).

Graphic 1. Number of cases of hepatitis B, C, and B/C, according to the start of treatment of patients treated in Amapá, Brazil, between 2013 and 2023. Source: self-made

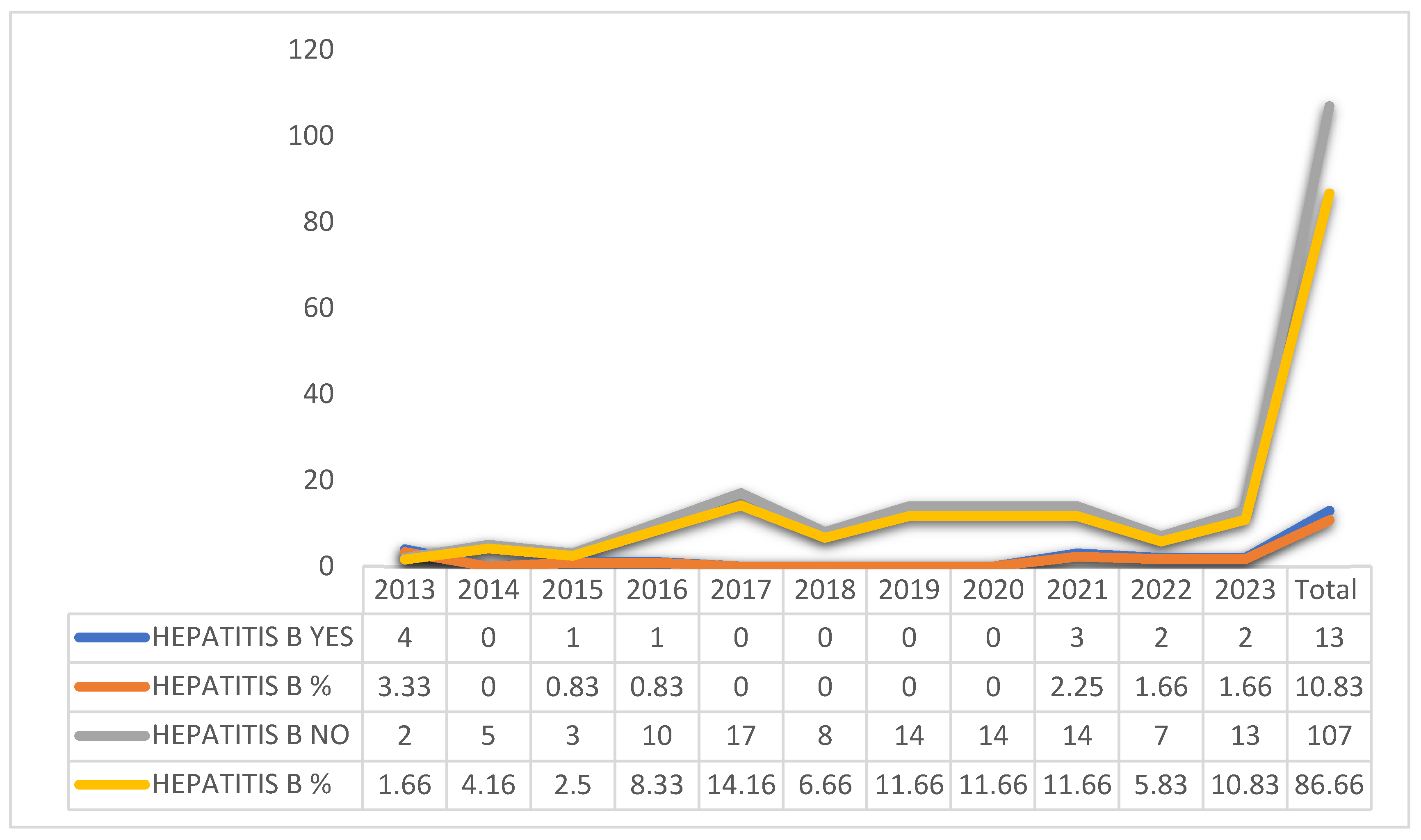

Graphic 2 describes that there was a change in the treatment of patients, according to the year of occurrence, with the years 2013 (3.33%) and 2021 (2.25%) being more prevalent.

Graphic 2. Change of treatment, according to the year of occurrence of hepatitis B patients, Amapá, Brazil between 2013 and 2023. Source: self-made.

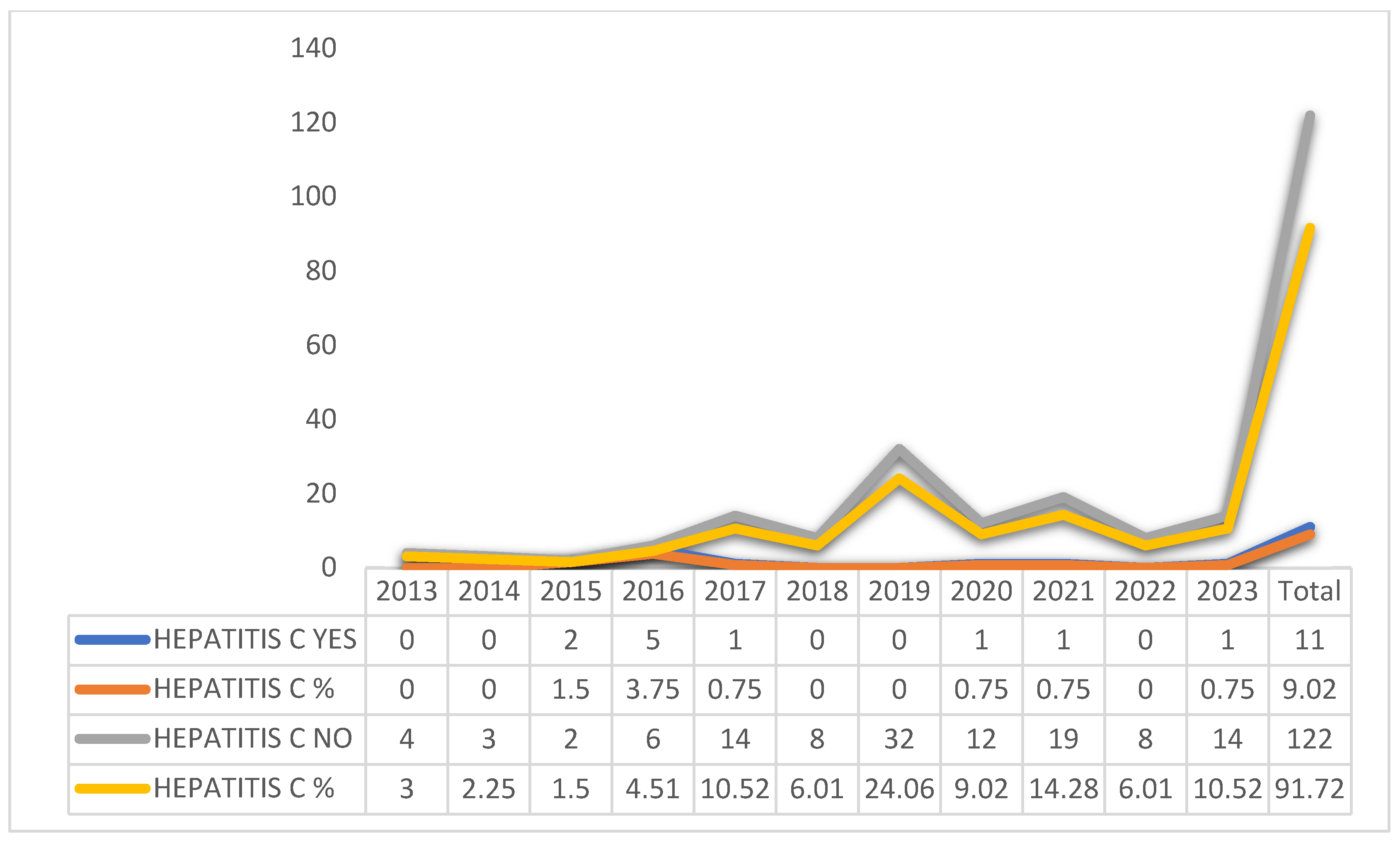

Graphic 3 shows that there was a change in the treatment of the patients, according to the year of occurrence, with the years 2015 (1.5%) and 2016 (3.75%) being the years with the highest percentages of patients who changed treatment.

Graphic 3. Change in treatment, according to the year of occurrence of hepatitis C patients, Amapá, Brazil between 2013 and 2023. Source: self-made.

The association between the "types of Hepatitis B and C" with the "age group" was statistically different (p = 0.001) for the ages of 20-39 years old and 60 or + years old. The range of 20-39 is associated with Hepatitis B and the range of 60 years old or over has association with Hepatitis C. For Hepatitis B, a proportion of 47.4% was expected in the range of 20-39 years old and the actual value was 75.0% (significant and far beyond what was expected), for Hepatitis C were expected a proportion of 52.6% for the age group of 60 years old or over and it was verified that the real value was 79.7% (significant and well beyond what was expected) (

Table 5).

The association between "coinfection by B24" according to the "etiological classification" (0.068), indicating no association between B24 coinfection and etiological classification of hepatitis, was expected about 25,6% B24 cases for both hepatitis B and C and the actual proportions were 38.1% and 13.6%, the test showed that these proportions are statistically equal to the expected proportion of 25,6%, therefore, are not significant and the differences occurred in the sample size (

Table 6).

Table 7 shows associations between the variables "gender" and "treatment abandonment", no statistical differences were observed (p = 0.330). The expected dropout ratio of 32.9% for both genders and the actual percentage values were 34.7% for women and 31.3% for men, not differing from the reference value of 32.9%.

4. Discussion

This study allowed to know the epidemiological aspects associated with cases of viral hepatitis B and C, attended at the reference center in tropical diseases of the State of Amapá in the period from 2013 to 2023. Among the results obtained, we can verify that in relation to cases of viral hepatitis were predominant in males, as well as in the age group of 20 - 59 years old, with schooling for full secondary education, with origin of the public health system, with low prevalence of smoking and alcoholism, as well as low frequency of pregnant women.

In this study the epidemiological profile previously described converges with the national and international literature, showing a prevalence of males, confirming in the various studies that men are more vulnerable because they are more susceptible to risk factors [

14,

15]. What they are: greater exposure to unprotected sexual intercourse, use of a larger amount of injectable drugs, in addition to the low search for health services, which allowed men more exposed to illness [

14,

16].

Regarding the age group, it may vary according to the Region and type of hepatitis, reflecting social, behavioral and health accessibility factors. The age group found in this study is closely related to the lifestyle and risk behavior of individuals, being a socially active group, which may increase exposure to practices that favor the transmission of viruses, as the sharing of sharp objects, unprotected sexual intercourse and the use of injectable drugs. In addition, the lack of awareness about the importance of preventive measures such as vaccination against hepatitis B and the use of condoms contributes to this panorama [

17,

18].

In addition, it was evidenced that the variable schooling, presented higher proportions for complete high school, similar to several national and international studies, where individuals with lower educational level tend to have less access to health information, prevention and treatment of diseases. This includes lack of knowledge about hepatitis transmission modes [

15,

17,

18]. In addition, low education is often associated with unfavorable socioeconomic conditions, which can limit access to quality health services with fewer resources and infrastructure for diagnosis and treatment, increasing the risk of infections [

14,

19]. The combination of these factors creates favorable conditions for the spread of hepatitis in vulnerable communities.

In the study of frequency was evidenced by the public service, where the dimension of the Unified Health System (SUS) assumes an important role in reducing inequalities and mainly in neglected diseases in vulnerable population, it is important to strengthen these services to ensure a more equitable service [

20]. In addition, the Institute of Hematology and Hemotherapy located in the study city identified volunteers for blood donation, with previous serological status of hepatitis B or C [

21]. Demonstrating that the control and investigation of hepatitis by blood banks can be allied to the epidemiology of the disease.

Thus, smoking and alcoholism, despite the low prevalence in the study, may reflect the non-verbalization by the patient in the act of anamnesis, which has the opportunity to address issues such as life habits, the patient may not report this information if it is not asked, it is known that it is an aggravating factor for health and many people die from the use of this product, the incidence of cancer by smoking has increased and remains a serious health problem and cause of impact on people’s lives [

22], however, it becomes important to know to better conduct the assistance, especially in alcohol consumption associated with HBV infection and HCV increases the risk of cirrhosis and even liver cancer [

23].

The study showed a low frequency of pregnant women, affected by viral hepatitis, focusing on prenatal care and quality of care, through the offer of examination and vaccination against Hepatitis B, being important the vaccination and the control of the three doses, as well as the guidelines for prevention of pregnancy during prenatal care. When testing positive, the viral load should be tested for diagnostic confirmation and a line of care should be prioritized [

24,

25,

26].

Our findings showed prevalence by residents in the metropolitan Region of Macapá and Santana, due to the reference located in the capital Macapá and care is still centralized, causing serious problems in the continuity of treatment and/or follow-up; therefore, patients living in other municipalities of the State find difficulties in quitting due to socioeconomic issues.

Thus, the geography of the distant municipalities of the capital of the State of Amapá portrays the difficulties of access, causing impacts on the search for health services, especially the populations of water people living on the banks of rivers, distant from the metropolitan Region with poor structure to ensure the care of medium complexity where the determinants of health factors contribute to the maintenance of the disease in these localities, with dissonant effects on the availability of health services and early diagnosis [

27,

28,

29].

The research revealed etiological classification type C in a greater number than type B, although it did not show statistical difference, the World Health Organization States that 80% of people infected with B and C virus remain undiagnosed or without access to health services [

30], it can be considered that the vaccination offered in SUS for children at birth positively impacts on the etiology of B virus, In view of this, surveillance actions and strategies to achieve early diagnosis and treatment expansion are essential [

31].

In coinfection and comorbidities there were significant results, also to other diseases viral hepatitis is associated with the Social Determinants of Health (SDH) considered a neglected disease and that affects negatively due to its silent action, combined with coinfection and comorbidities potentiates more its effects. The SDH are conditioning factors in the health-disease process, therefore, remedial measures should be implemented to enable access of vulnerable public [

32].

Regarding liver transplantation, the prevalence of patients who needed to proceed with the transplant was low, but does not rule out concern, because one of the complications of viral hepatitis is hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), due to the fact that many times the disease has been diagnosed late, patients with HCC who have undergone liver transplantation present thyroid metastases, and periodic investigation of these patients is necessary [

33].

In the study, with regard to the tests performed, HBsAG presented a reagent result of 46.5%, CV-HBV obtained a detectable result of 79.8%, and these tests were carried out by LACEN, funded by SUS. In the anti-HBc Total test, 24.5% presented a reagent result with a high prevalence of patients who did not take the test 68.4%. The difficulties encountered by patients with regard to the performance of examinations is that the public health system does not offer these examinations on a constant basis (discontinuity of service), being obliged to perform the patient in the private network.

A study on screening and testing for hepatitis infection in the United States recommended collaboration between laboratories to group the three HBV tests (HBsAg, anti-HBs, anti-HBc), thus strengthening laboratory monitoring and diagnosis, would optimize the request of examinations [

16,

34]. It is indispensable to carry out the HBsAG marker for diagnostic purposes and therapeutic conduct, because individuals born in the Amazon Region are vulnerable to HBV infection and have indication of screening [

4].

The findings showed the anti-HBs examination, a prevalence of patients eligible for the examination who did not perform the examination, thus making it difficult to know if the person is immunized against hepatitis B, especially in patients with hepatitis C. Recommended if the vaccination against hepatitis B or revaccination in cases of incomplete regimens or if it is part of a population eligible for examination (dialytics, co-infected with the HIV virus, immunocompromised, sexual partnerships of people with hepatitis B, health professionals), guidelines regarding the completeness of the vaccination scheme in cases of non-reactive anti-HBs and non-reactive HBsAg, given that hepatitis B is an immunoprevensible disease [

35,

36].

In the Anti-HDV examination, with a high percentage of those who did not take this test, in 2024, LACEN made available this test for investigation of HDV through the viral load examination because it is an indicated test in patients with hepatitis B, HBV/HDV coinfection has high rates in the State of Acre [

37]. The Anti-HAV test did not register patients with a reactive result, but obtained a high percentage that did not perform this examination, because it does not have positive records, vaccination against HVA is recommended, the non-registration of reactive cases points to the fact that the examination was not performed, making the follow-up of viral hepatitis fragile.

Regarding the beginning of treatment, it was revealed in this study that the year 2019 presented a higher number of cases attended at CRDT, followed by the year 2021, we can reflect on the pandemic period, what caused the low demand of the health service or the discontinuity of the follow-up of patients. In the findings of this study, there was a prevalence of change in treatment for Hepatitis B in 2013 and 2021, and in 2015 and 2016 a change in treatment for Hepatitis C in CRDT and a reduction in the remaining years of the studied period.

It was observed in the study change of treatment of hepatitis B in the years 2013 and 2021, factors such as comorbidities, co-infections, pregnancy, lead to changes in the choice of medicines, being the antiviral therapy used with criteria to avoid complications especially in pregnant, elderly and immunosuppressed [

38].

Additionally, in the period of increased change of treatment antiretroviral drugs were genotypic, requiring genotyping tests for treatment definition, liver biopsy, creating difficulties in this follow-up, as, the comorbidities and co-infections present. Currently, especially in hepatitis C, the Direct-Action Antivirals (DAAs) are used that are pangenotypical, dispense with the genotyping test, which financially favors the treatment for the individual and the eradication of the virus, contributing to the control of the disease and reducing the risk of hepathocarcinoma. In addition, treatment with antivirals and continuous monitoring, surveillance of the disease for early diagnosis aims to achieve global goals of elimination of viral hepatitis by 2030 [

39,

40].

The research performed associations between sex and etiological classification (p=0.227), not being statistically significant, demonstrating that both genders are exposed to the disease [

41]. However, the association between the types of Hepatitis B and C with age was statistically different (p=0.001) for the ages 20-39 years old and 60 or over. The 20-39 years old age group is associated with Hepatitis B and the 60 years old or older age group has an association with Hepatitis C, viral hepatitis has been shown globally with the strength of the disease constantly varying between age groups.

In this context, hepatitis B considered as a sexually transmitted infection is understood about the age group due to being sexually active people [

42], while etiology C showed in individuals over 60 years old comprises -on the past practices with reuse of syringes, blood banks with little rigor in the control of infections, tattoos, surgeries, among others, as well as, because there is still no vaccine against hepatitis C [

43].

Regarding the coinfection, our findings showed HIV co-infection and an etiological classification of 72.7% in hepatitis B and 27,3% in hepatitis C, studies demonstrate that HIV can affect in multiple mechanisms the pathogenesis of HBV in HBV/HIV coinfection as evidenced in their studies [

44], describes that HDV/HCV/HIV infected have a higher risk of progressing the aggravation and complications, therefore, the follow-up should be rigorous in this context [

45].

It is worth noting that the research showed that the abandonment to treatment associated with sex did not present differences, both men and women abandon the treatment, However, it is necessary to have a strategy in health services so that there is no discontinuity in the follow-up of diseases and vulnerable populations; however, abandonment reflects on a global problem and contributes to an increase in cases [

46,

47]).

The findings of this study contribute to the strengthening of public policies, as well as to the practice of health professionals to act with more rigor and a vision focused on care in the control of infectious diseases at various levels of care. The results point to the need for interventions considering Regional peculiarities. As a limitation of the study, found medical records with lack of information.