1. Introduction

The Fourth Industrial Revolution, also known as Industry 4.0, focuses on optimizing resources while integrating advanced human skills. It is characterized by the increasing use of robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT), and big data, which together are transforming industries, services, and daily life [

1]. A key aspect of this revolution is the replacement of human labor by machines or the enhanced interaction between the two [

2]. Similar to past industrial revolutions, Industry 4.0 seeks to improve efficiency in resource utilization. Automation is a prime example, enabling, e.g., the development of autonomous vehicles and accelerating the adoption of car-sharing by removing the need for human drivers.

A major technological enabler of Industry 4.0 is the evolution of mobile communications, particularly the transition from the fifth generation of mobile communications (5G) into the sixth generation of mobile communications (6G). While 5G enabled direct machine-to-machine communication [

3], 6G aims to enhance these capabilities by supporting real-time data exchange, advanced ultra-reliable low-latency communication, and high-speed connectivity for industrial automation and IoT applications. These advancements are crucial for applications such as autonomous systems, remote healthcare, and smart infrastructure.

The upcoming 6G will further extend these capabilities by enabling advanced services such as holographic communication, immersive extended reality (XR), and next-generation autonomous systems. Additionally, 6G will facilitate seamless interaction with high-speed unmanned aerial vehicles, further expanding its impact across multiple sectors. To support these applications, 6G must achieve ultra-high data rates, increased spectral efficiency, and minimal latency. Among the key enabling technologies, Large Intelligent Surfaces (LIS) stand out as a promising approach to improving spectral efficiency and communication reliability through large-scale antenna arrays.

To meet the demands of these new applications, 6G will need to achieve speeds of up to 1 terabit per second, substantially increase network capacity to support a higher density of connected devices and dramatically reduce latency. These improvements are essential for real-time applications such as autonomous driving, online gaming, and remote control of critical infrastructure. To enable such high-performance connectivity, 6G will rely on cutting-edge technologies, including block transmission techniques, advanced error correction codes, and LIS. The LIS concept represents an evolution beyond massive multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) systems, incorporating an even larger number of antenna elements to enhance spectral efficiency and data transmission rates.

By integrating these innovations, 6G will provide the necessary foundation to interconnect billions of IoT devices with unprecedented speed, reliability, and efficiency, driving the next phase of industrial and technological advancement.

The concept of LIS has gained significant attention as a means of improving wireless communication efficiency through large-scale antenna arrays. Unlike conventional MIMO systems, LIS exploits a dense array of antennas spread over an extended area, enabling enhanced beamforming and spatial multiplexing.

Wireless communications are typically established beyond the Fraunhofer distance, meaning they operate in the far-field [

4]. While individual antenna elements of an LIS function in the far-field, the LIS system, as a whole, operates in the near-field [

4,

5,

6,

7]. As a result, it can be considered a near-field beamformer, distinct from conventional beamformers in that it not only directs beams along azimuth and elevation angles but also adjusts them based on distance. This latter capability (direct the beam through distance) helps mitigate interference between users who share the same bearing and elevation but are positioned at different distances. It is worth noting that adjacent LIS antenna elements are usually spaced at λ/2, and the channel correlation between them enables the formation of the described beam.

In LIS systems, the use of a large number of receiving antennas allows for better spatial resolution and increased diversity, enabling the system to distinguish and recover multiple transmitted signals more effectively. Traditional receivers such as MRC (Maximum Ratio Combining), EGC (Equal Gain Combining), Zero-Forcing (ZF), and MMSE (Minimum Mean Squared Error) have been widely studied and applied due to their mathematical tractability and relatively low complexity [

7,

8,

9]. However, these methods are often limited by assumptions such as perfect channel state information and linearity of the channel model. Moreover, solutions based on matrix inversion—such as ZF and MMSE—can become computationally expensive when scaling to a large number of antennas [

7,

9].

A key challenge in LIS-based communication systems is multi-user interference (MUI), which significantly impacts system performance. Receivers, such as MRC and EGC, generate interference in the decoding process, added to MUI, which tend to degrade the performance. Contrarily, the ZF and MMSE receivers do not generate interference in the decoding process, but they require matrix inversion, leading to computational challenges.

In contrast, deep learning approaches offer the possibility of learning implicit representations of the channel and estimating the transmitted symbols directly from the received signals, without requiring an explicit inversion of the channel matrix. Recent advances have demonstrated the potential of deep learning to replace traditional detection and equalization techniques in communication systems, either by training detection algorithms without any prior knowledge of the channel model [

10], or by jointly learning equalization and decoding processes to improve performance in nonlinear and dispersive channels [

11]. This opens the door to more robust and potentially lower-complexity receiver architectures, especially when optimized for specific environments or channel conditions. In particular, deep learning-based receivers can adapt to complex propagation scenarios, non-linearities, and hardware impairments, and may be trained to outperform traditional linear techniques under certain conditions.

The motivation of this work is thus to investigate whether a neural network-based receiver can provide a viable alternative to conventional receivers, especially MRC and EGC, which are attractive for their simplicity—in the context of LIS systems. This includes evaluating whether a deep neural network can implicitly learn to perform the same role as these techniques (or better) while maintaining low computational complexity and reducing the reliance on analytical channel models.

In this study, we examine an LIS system [

8,

9,

12,

13,

14] utilizing single-carrier transmission with frequency-domain equalization (SC-FDE) [

15,

16], an alternative to orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (OFDM). Due to the high peak-to-average power ratio (PAPR) of OFDM signals, their application in uplink scenarios is less practical. SC-FDE, on the other hand, offers a lower PAPR, making it more suitable for uplink transmission. This paper evaluates the performance of four different receivers—ZF, MMSE, MRC, and EGC [

17,

18]—providing a comparative analysis of their effectiveness.

The contributions of this work are:

We propose a neural network-based interference cancellation approach for LIS systems, eliminating the need for iterative decoding traditionally used with MRC/EGC receivers.

We demonstrate that MRC and EGC receivers enhanced with neural networks outperform conventional ZF/MMSE receivers or MRC/EGC with iterative interference suppression, achieving a better balance between computational efficiency and performance.

We show that our method avoids the need for channel matrix inversion, reducing the computational complexity while maintaining competitive performance.

The outline of this article is as follows: system and signal characterizations are presented in

Section 2; the neural network-based interference cancellation is presented in

Section 3; the performance outcomes are shown and discussed in

Section 4; finally, the conclusions of this article are presented in

Section 5.

2. System and Signal Characterization

The evolution of 6G communications is anticipated to meet stringent performance requirements, including a peak data rate of at least 1 Tbps for nomadic access—100 times greater than 5G—and 1 Gbps in mobile scenarios, which is 10 times higher than its predecessor. Additionally, energy efficiency is projected to improve by a factor of 10 to 100, while spectral efficiency is expected to be enhanced by 5 to 10 times in comparison to 5G. These advancements are expected to be realized through the implementation of LIS systems operating in the terahertz spectrum, combined with block transmission techniques. It is important to note that increasing the carrier frequency results in a larger channel coherence bandwidth, translated in higher throughput.

LIS technology is particularly compatible with terahertz frequencies due to the reduced wavelength, which enables the use of ultra-compact antennas, thereby simplifying the deployment of cost-effective LIS panels. However, as the number of antennas in LIS systems grows—effectively functioning as beyond-massive MIMO—the associated signal processing demands also increase significantly. Consequently, there is a crucial need to explore receiver architectures with minimal complexity. This study links low-complexity receivers, which streamline the decoding process aiming to optimize the performance while keeping the computational complexity acceptable.

To mitigate intersymbol interference, block transmission techniques are frequently employed. The SC-FDE method, in particular, offers a key advantage over OFDM: it exhibits lower PAPR [

15,

16]. This characteristic makes it especially suitable for uplink scenarios and enhances the efficiency of power amplification [

19].

Unlike conventional communications between a user equipment (UE) and a base station (BS), LIS-based communication typically relies on line-of-sight connectivity. The LIS system functions as a short-range beamformer, with antenna elements spaced at half-wavelength intervals—much shorter than the three to four wavelengths commonly used in traditional MIMO configurations. While individual LIS antenna elements communicate in the far field, the overall LIS array operates within the near field, meaning communication occurs at distances shorter than the Fraunhofer limit, typically spanning just a few wavelengths. This unique property gives LIS systems distinctive capabilities. Whereas conventional beamforming is confined to azimuth and elevation adjustments, LIS extends this capability to the distance dimension as well. This enables interference mitigation from users who are aligned in azimuth and elevation but are positioned at varying distances.

As shown in

Figure 1, the

nth transmitted block, consisting of

N data symbols, from the

tth UE is represented as

, while the block received by the

rth antenna of the LIS system is represented as

. The relationship between the time-domain signal and the frequency-domain signal for the

kth subcarrier (assumed to be constant during the transmission of a given block) of the transmitted block is defined by the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT), such that

, i.e., performing the DFT of the time-domain block. A similar approach applies, mutatis mutandis, to the received signal block, channel, and noise.

The received signal in the frequency domain, expressed in matrix–vector form, is given by [

20]

where

represents the data symbols transmitted in the frequency domain, while

refers to the

channel frequency response for the

kth subcarrier (assumed to remain constant during the transmission of a given block), with the

th element denoted as

. Additionally,

represents the frequency-domain block channel noise for that subcarrier [

20].

2.1. System and Signal Model for the Receivers

It is well-established that ZF and MMSE receivers are computationally intensive, as they require channel inversion for each frequency component, which results in significant battery consumption. The ZF receiver offers the benefit of effectively mitigating intersymbol interference. However, it also suffers from increased noise levels under moderate to high noise conditions, leading to a degradation in performance. In contrast, MRC and EGC receivers avoid such complexity, resulting in a simpler receiver architecture that is particularly advantageous in an LIS scenario with a very large number of antenna elements. However, MRC and EGC receivers introduce some interference during the decoding process, which can be mitigated using iterative receivers.

Considering a non-iterative receiver, the estimated frequency domain data symbols

is defined as.

Depending on the algorithm,

can be computed differently [

17]. Using the ZF receiver,

comes

, while

comes

for the MMSE, where

and where

is an

identity matrix. Using the MRC receiver,

comes

and

comes

for the EGC.

Iterative block decision feedback equalization (IB-DFE) [

16] is a highly efficient receiver for SC-FDE, utilizing feedforward and feedback coefficients for enhanced performance. While MRC and EGC are computationally simple, they generate residual interference, especially with moderate signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) values. This can be countered by iterative receivers, similar to IB-DFE, implementing the function:

where the interference cancellation matrix,

, is computed as

[

18], and where

is an

identity matrix.

As an alternative to this iterative receiver, we propose an interference cancellation process applied at the output of the MRC/EGC receiver (with a single iteration), based on a neural network, as defined in the following.

3. Neural Network-Based Interference Cancellation in LIS Systems

In this work, we propose a neural network-based approach for interference cancellation in LIS systems, specifically targeting MRC and EGC receivers. Traditional iterative interference cancellation methods are sub-optimal [

7]. On the other hand, using ZF or MMSE receivers, significant computational complexity is required due to the repeated matrix inversions required at each channel frequency component. Our approach leverages neural networks to learn a mapping from received signals to transmitted signals, effectively bypassing the need for iterative interference cancellation. The neural network is trained to learn the relationship between the received signal, which is affected by interference, and the transmitted signal, represented by

. This allows the network to remove the interference without the need for direct channel matrix inversion or iterative receiver.

4.1. Neural Network Architecture

The neural network model was designed considering the trade-off between computational complexity and performance improvement. Extensive testing showed that increasing the network depth beyond three fully connected layers did not lead to significant performance improvements, while a shallower network resulted in degraded signal recovery. As such, the proposed architecture consists of three key fully connected layers, each serving a specific role in feature extraction and signal reconstruction.

The proposed Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) architecture is well-suited for interference cancellation in LIS systems using MRC/EGC due to its ability to learn non-linear mappings between the received signals and the transmitted signals. Since the interference is generated during the decoding process rather than being a direct function of the channel matrix inversion, the primary goal is to estimate and remove this interference rather than reconstruct the original transmitted signal through explicit channel equalization. The MLP effectively captures complex signal relationships introduced by MRC/EGC processing while maintaining a manageable computational cost. Other architectures, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, were also evaluated but found to be less appropriate, as the interference structure lacks significant spatial or temporal correlations. Additionally, the structure of the MLP network, with three fully connected layers and ReLU activations, ensures a sufficient level of non-linearity to model the interference effects while avoiding unnecessary complexity that could lead to overfitting.

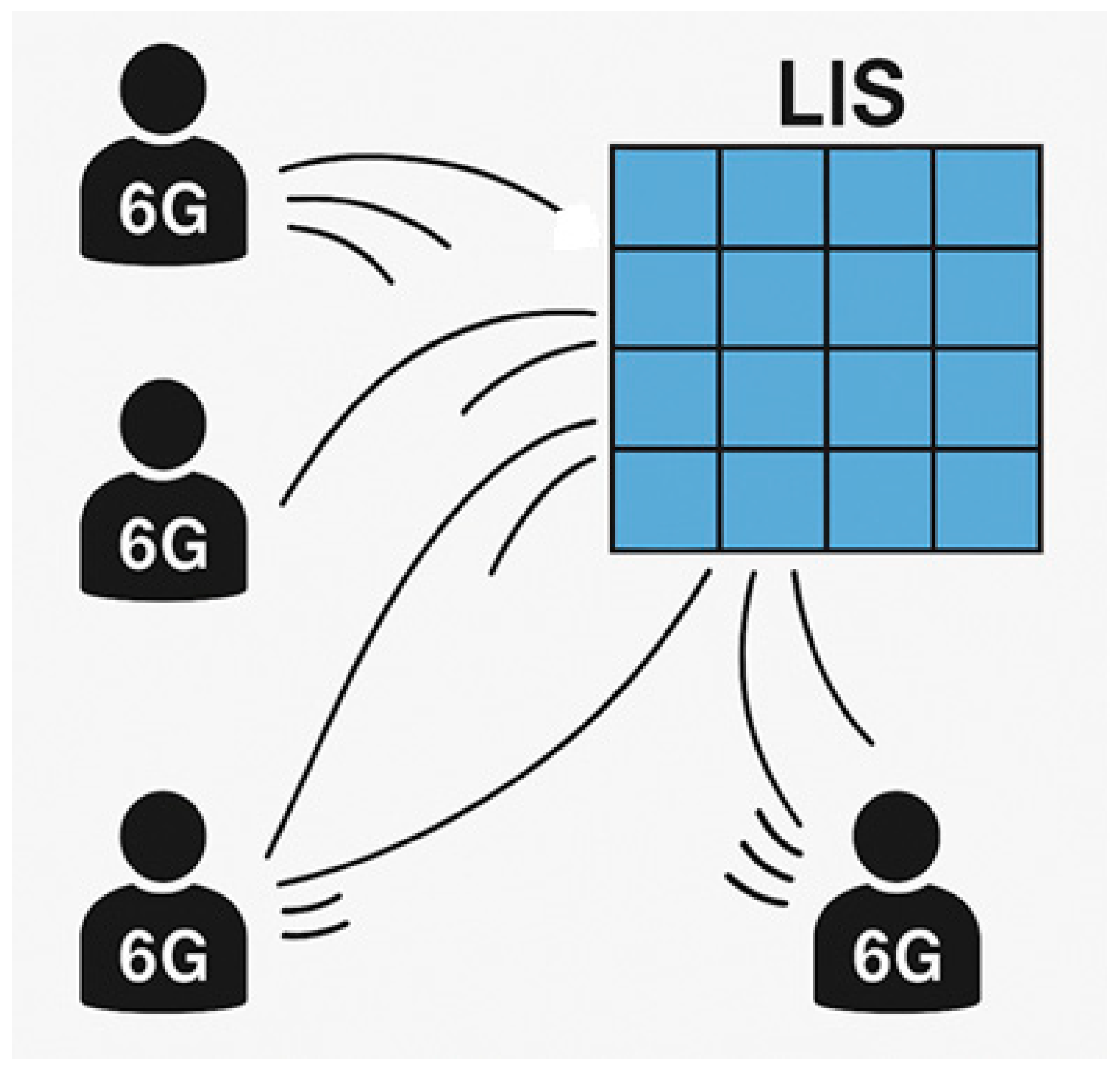

The aim of the neural network relies on removing interference (see

Figure 2). To ensure robust learning, the dataset is structured such that each transmit antenna has a dedicated neural network trained independently. Note that the aim is to estimate the signals transmitted by each one of the transmit antennas. This design choice was motivated by the observation that training a single network for all antennas introduced inconsistencies due to varying channel conditions across antennas. The choice to train independent networks for each antenna is based on the variability of channel conditions across antennas. This ensures that the network can adapt more accurately to the specific conditions of each antenna, resulting in more efficient signal reconstruction.

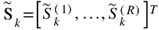

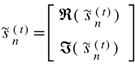

The network receives as input the received signals at the output of the MRC/EGC detector, corresponding to the estimation of the tth transmitted antenna, where the in-phase (I) and quadrature (Q) components are treated as separate features. Note that the neural network processes signals in the time domain. These two components (I and Q) are jointly feed to the network, in a new dimension of the matrix, to achieve the required correlation during training and prediction processes. The input to the neural network is structured as a two-dimensional vector, where the I and Q parts of the received signal are presented as separate features but concatenated to maintain correlation during training:

The length of the dataset is N, the block size during training.

The architecture consists of the following layers:

Feature Input Layer: A featureInputLayer with two input features (I & Q components), ensuring compatibility with the structure of complex-valued signals, compatible with QPSK (Quadrature Phase Shift Keying) complex modulation.

Fully Connected Layer 1: A fullyConnectedLayer with 20 neurons, responsible for initial feature extraction.

ReLU Activation: A reluLayer to introduce non-linearity, improving the network’s ability to capture complex signal relationships.

Fully Connected Layer 2: A fullyConnectedLayer with 10 neurons, further refining the extracted features.

ReLU Activation: Another reluLayer to enhance non-linearity and robustness.

Fully Connected Output Layer: A fullyConnectedLayer with two neurons, reconstructing the in-phase and quadrature components of the transmitted signal.

Regression Output Layer: A regressionLayer to optimize the network for minimizing signal reconstruction errors.

This configuration was selected after an extensive evaluation of various network depths and neuron configurations. More complex architectures with additional layers and neurons did not provide significant performance improvements, while reducing the network’s depth led to a noticeable degradation in signal reconstruction accuracy.

4.2. Training Process

The training data consists of received signals, detected by MRC/EGC with a single iteration, as inputs, and their corresponding transmitted signals as outputs. The output of the MRC/EGC decoder is corrupted by interferences generated in the decoding process (expression (2)).

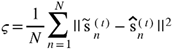

The training process minimizes the Mean Squared Error (MSE) between the predicted and actual transmitted signals:

where

is the actual output signal from the one iteration MRC/EGC detector, while

is the estimated output of the neural network (same signal clean of interference).

Training was performed using the Adam optimizer with the following hyperparameters:

Each neural network was trained to minimize the MSE between the predicted and actual transmitted signals. The batch size of 16 was chosen as a balance between training stability and convergence speed.

4.3. Inference and Signal Reconstruction

During inference, the trained neural networks estimate the transmitted signal from the received signal on a per-antenna basis. Given that each antenna has its own dedicated model, predictions are performed individually, ensuring optimal signal reconstruction for each channel condition.

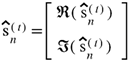

For each received symbol, the I & Q components are extracted as

, processed through the trained model, and recombined to form the estimated complex-valued transmitted signal:

Each layer in the neural network applies a transformation, where a fully connected layer follows:

where W(l) and b(l) are the weights and biases of layer l, and the activation function ReLU ensures non-linearity.

This approach eliminates the need for iterative matrix inversions, significantly reducing computational overhead while surpassing the performance of conventional iterative interference cancellation techniques. The neural network drastically reduces the need for repeated matrix inversions, which are computationally intensive or iterative receivers, making the system more efficient in terms of processing time and energy consumption. Compared to traditional methods, the neural network provides a computationally lightweight solution without significantly compromising signal estimation quality.

4. Simulation Results and Analysis

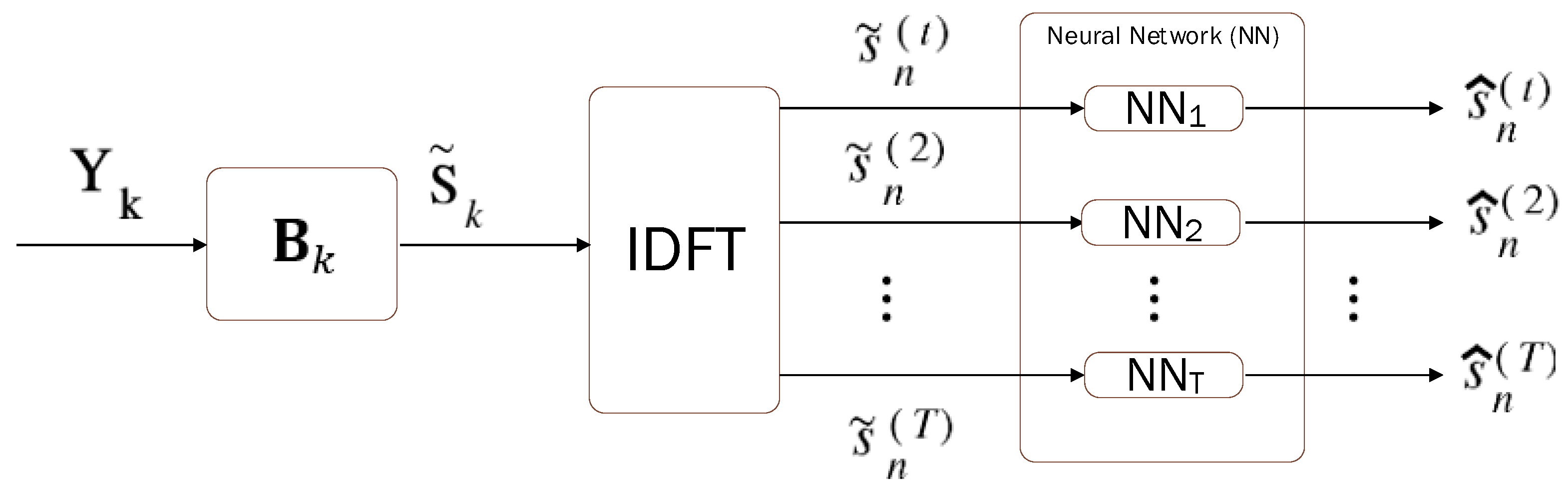

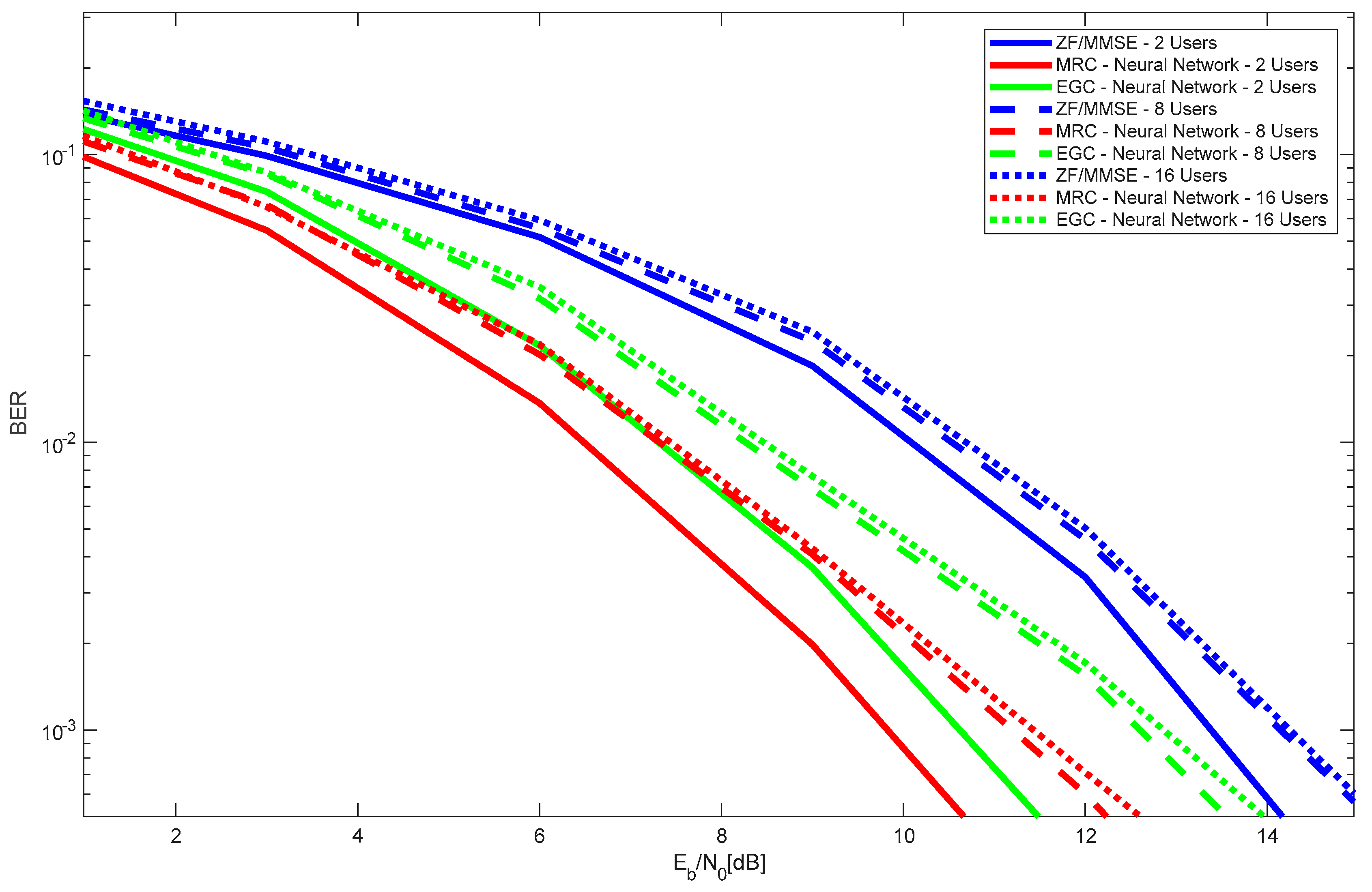

This section evaluates the performance of the LIS in terms of bit error rate (BER) as a function of , where represents the energy per transmitted bit and is the one-sided noise power spectral density. The results are obtained through Monte Carlo simulations, employing SC-FDE for block-based transmission.

During the simulations, user positions are randomly assigned within the environment. The propagation channel includes five multipath components—one direct line-of-sight (LoS) path and four reflections from the walls. The power of each multipath component is determined by propagation characteristics, such as total path length and reflection losses.

The results consider QPSK modulation and a block size of

N = 256 symbols (with similar results observed for other large values of

N).

Figure 3 illustrates the 3D spatial distribution of users and the placement of the LIS panels, offering insight into how users align with the panels. The simulation environment consists of four ceiling-mounted panels, each equipped with a varying number of antennas. For the sake of simplicity, this figure only shows direct paths, not reflected paths.

In addition to conventional iterative receivers based on MRC and EGC used to mitigate the interferences generated in the decoding process, this work explores the application of neural networks for interference cancellation during the decoding process. These networks are trained to mitigate interference effects and optimize signal recovery. The Monte Carlo simulations incorporate multiple user distributions, as the positions of users are randomly reselected in each run, ensuring statistical robustness in the analysis. The performances obtained with the different receiver types are analysed in multiple scenarios with various number of users and different number of antennas.

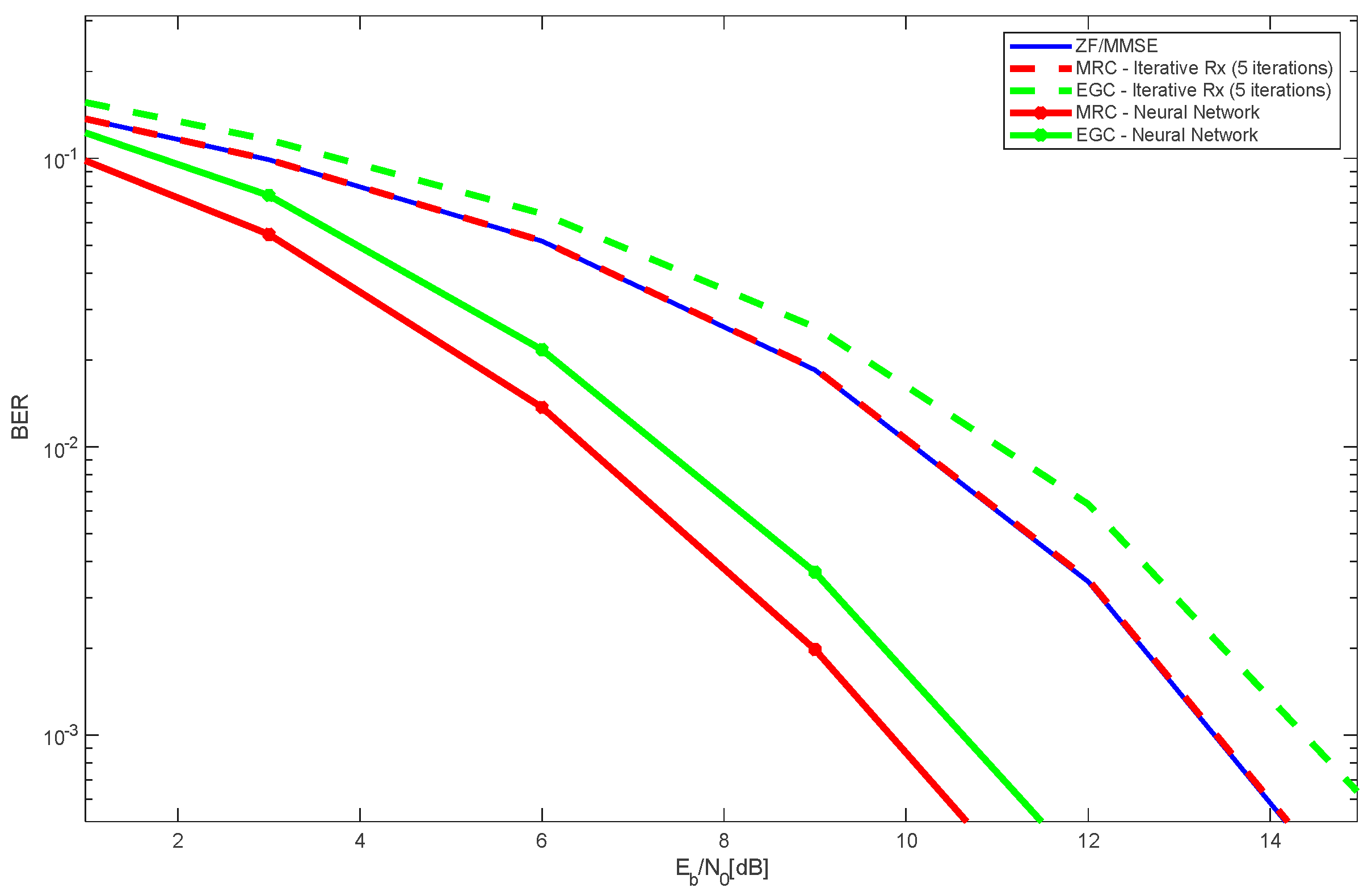

Figure 4 presents the performance results for a LIS setup consisting of four panels, each equipped with 400 antennas, arranged in a 20×20 configuration per panel. This results in a total of 1600 antennas within the LIS system. The scenario includes two users: one serving as the reference user and the other acting as an interfering user. As can be seen, the performance obtained with the MRC with iterative receiver (5 iterations) is approximately the same as ZF and MMSE receivers. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the ZF and MMSE receivers requires the computation of the pseudo-inverse of the channel matrix, for each frequency component of the channel, which is very computationally demanding. On the other hand, the EGC with iterative receiver (5 iterations) performs worst than MRC/ZF/MMSE. Observing the performance obtained with the MRC and EGC associated with neural network receiver, it is clear the performance improvement of the order of 5 dB, as compared with the corresponding iterative receiver. Note that the performances are even better than ZF and MMSE. It is viewed that the MRC with neural receiver is the one that achieves the best overall performance, without requiring explicit channel matrix inversion. The neural network significantly minimizes the requirement for multiple matrix inversions, which are computationally demanding, enhancing the system’s efficiency in both processing speed and energy usage. The training can be computationally demanding, but the prediction is straightforward. In contrast to conventional approaches, the neural network offers a more resource-efficient alternative while maintaining a high level of accuracy in signal estimation.

These results demonstrate that leveraging neural networks in LIS receivers provides a promising alternative to conventional interference cancellation techniques, paving the way for efficient and scalable implementations in future 6G communication systems.

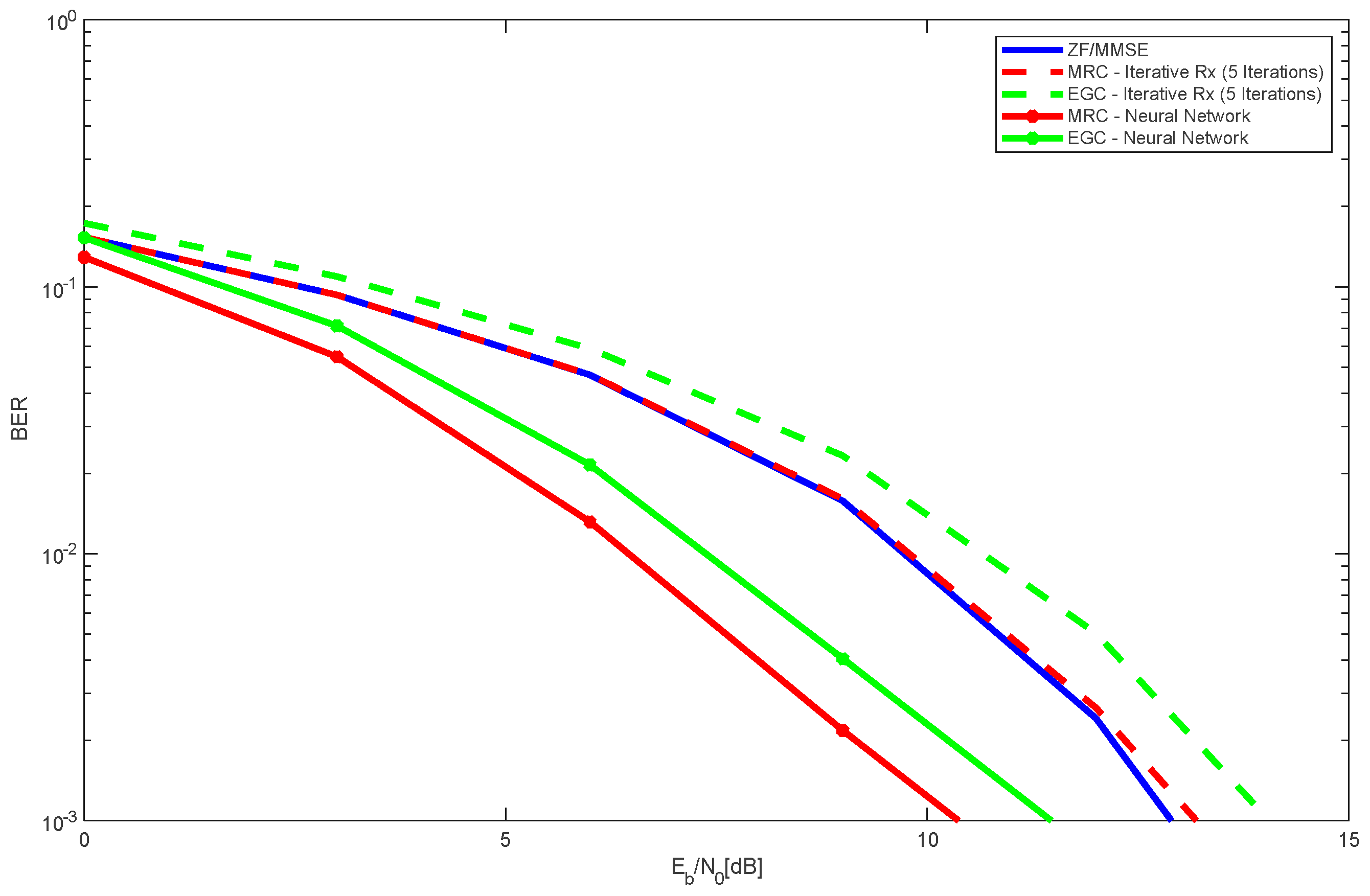

Figure 5 illustrates the performance results for a 4 × 225 LIS configuration, considering two users and various receiver types. This setup consists of four panels, each containing 225 antennas, arranged in a 15×15 grid per panel, leading to a total of 900 antennas in the LIS system. Similar to the previous figure, the scenario involves one reference user and one interfering user. The results indicate that, as observed earlier, the combination of MRC and EGC with a neural receiver outperforms iterative receivers, as well as ZF and MMSE methods. Among these, MRC with a neural receiver demonstrates the best performance, followed by EGC with a neural receiver, which still surpasses the results obtained with ZF and MMSE techniques.

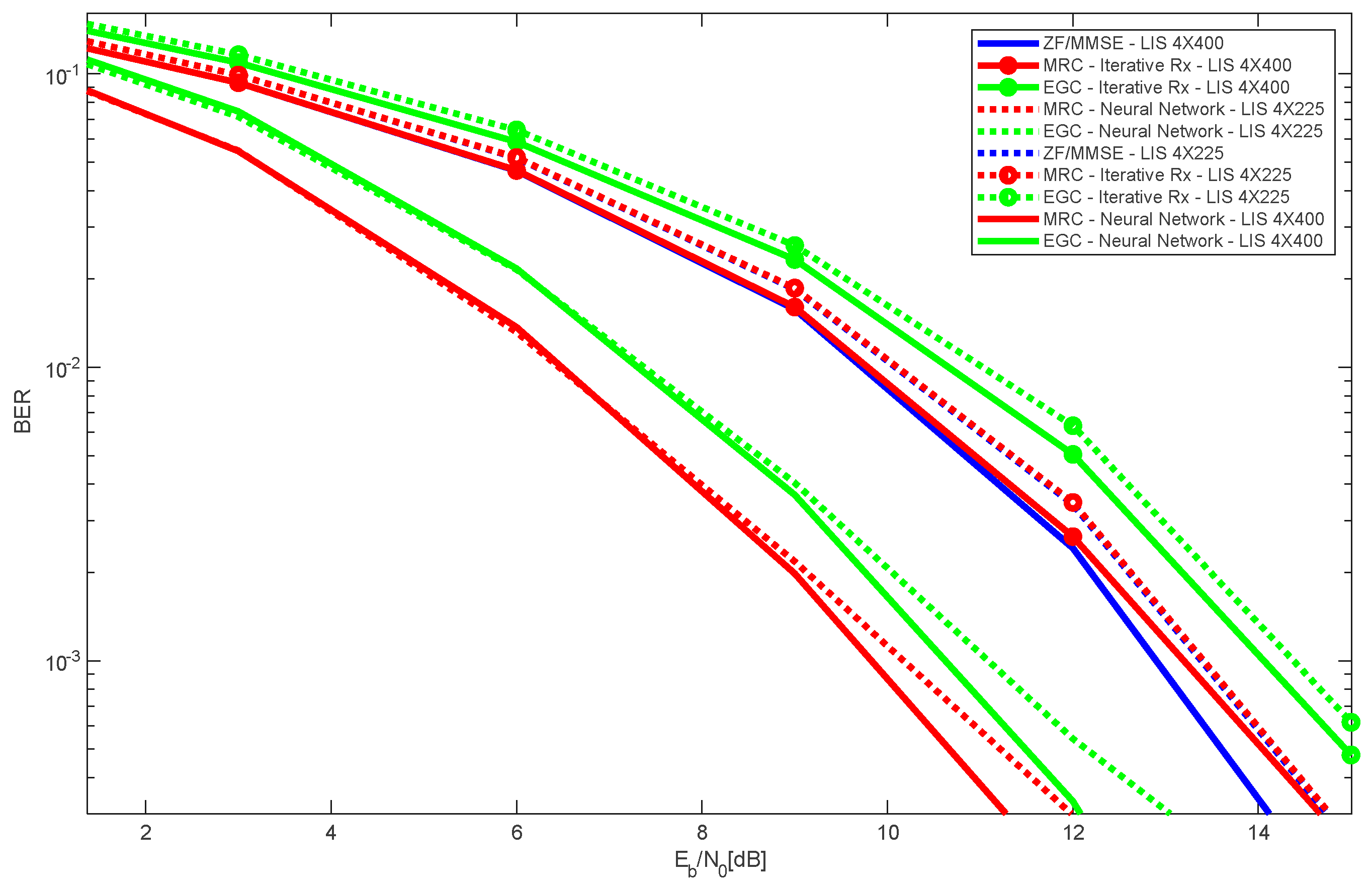

Figure 6 shows the performance with two LIS configurations: 4x400 and 4x225. Two users were considered in the simulations. As expected, results obtained with 4x400 LIS configuration are always better than those obtained with 4x225, for all different receiver types. Moreover, it is viewed that the best overall performance is obtained with 4x400 LIS configuration and MRC with neural receiver.

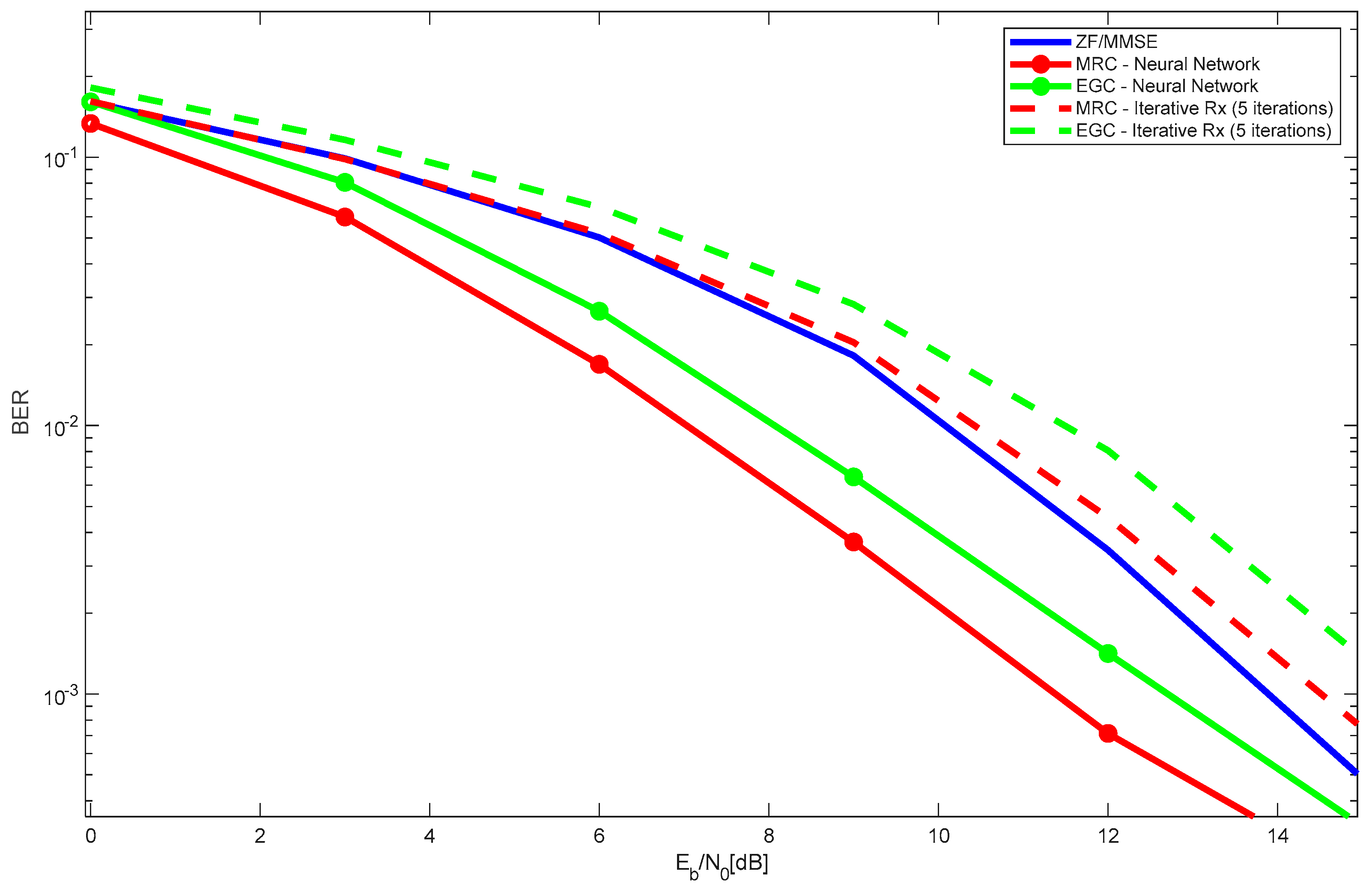

Figure 7 shows the performance results of the 4 × 400 LIS system, with 16 users, with iterative receiver and with Neural Network, for both MRC and EGC. Results for ZF/MMSE are also plotted. Similar to the results shown in

Figure 4 (2 users),

Figure 7 shows that, with 16 users and for this LIS configuration, the best overall performance is obtained with MRC Neural Network receiver. As expected, the performance of ZF/MMSE stays within MRC/EGC iterative receivers and MRC/EGC neural network receivers.

Figure 8 shows the performance results of the 4 × 400 LIS system, with several number of users (2, 8 and 16 users), with iterative receiver and with Neural Network, for both MRC and EGC. Results for ZF/MMSE are also plotted. As expected, the performance degrades with the increase in the number of users. Nevertheless, the performance degradation that occurs by changing 8 users into 16 users is very low. This occurs because the LIS is able to mitigate interference very efficiently. The receiver that reaches the best overall performance, regardless of the number of users is the MRC with the neural network receiver, followed by the EGC.

5. Conclusions

This work introduced a neural network-based approach for interference cancellation in LIS systems employing MRC and EGC receivers. The proposed method replaces traditional iterative interference cancellation techniques by leveraging a MLP to estimate the transmitted signals directly from the output of a single iteration MRC/EGC receiver, which comprises interference-corrupted signals. This approach effectively mitigates the interference generated in the decoding process of MRC/EGC, improving signal recovery without requiring explicit channel matrix inversion, as required for ZF and MMSE receivers. Moreover, it was viewed that the MRC/EGC with neural network outperforms MMSE and ZF. Finally, it was viewed that the MRC always outperforms EGC (with or without neural network.

The chosen network architecture, consisting of three fully connected layers with ReLU activation, was selected based on extensive empirical evaluations, balancing complexity and performance. A deeper network did not yield significant improvements, while a shallower one resulted in degraded performance. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed neural network-based approach outperforms traditional iterative interference cancellation methods in terms of signal reconstruction accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency. The decision to train separate neural networks per transmit antenna was justified by the statistical independence of antennas, ensuring robustness against varying channel conditions. Additionally, alternative architectures such as CNNs and LSTM networks were considered but deemed less suitable due to the absence of strong spatial or temporal dependencies in the interference structure.

Overall, this work confirms that neural networks provide a promising alternative for interference mitigation in LIS receivers, offering a practical and scalable solution for future 6G communication systems.

Future work could explore deeper neural architectures and test the proposed approach in real-time scenarios to validate its practical applicability.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is funded by FCT/MCTES through national funds and, when applicable, co-funded EU funds under the projects UIDB/EEA/50008/2020 and 2022.03897. PTDC.

Data Availability Statement

Data was obtained using Monte Carlo simulations and implemented using Matlab R2025a.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of FCT/MCTES, as described above in the funding section. We also acknowledge the support of Autonoma TechLab for providing an interesting environment in which to carry out this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kunze, L.; Hawes, N.; Duckett, T.; Hanheide, M.; Krajnik, T. Artificial Intelligence for Long-Term Robot Autonomy: A Survey. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2018, 3, 4023–4030. [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M. Big IoT Data Analytics: Architecture, Opportunities, and Open Research Challenges. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 5247–5261.

- Cabeças, A.; Marques da Silva, M. Project Management in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. TECHNO REVIEW Int. Technol. Sci. Soc. Rev. 2021, 9, 79–96. [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Hanzo, L. RIS-Aided Near-field Communications for 6G: Opportunities and Challenges. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.13004.

- Decarli, N.; Dardari, D. Communication Modes with Large Intelligent Surfaces in the Near Field. IEEE Digit. Object Identifier 2021, 9, 165648–165666. [CrossRef]

- Bjornson, E.; Özlem, T.; Sanguinetti, L. A primer on near-field beamforming for arrays and reconfigurable intelligent surfaces. In Proceedings of the 2021 55th Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems, and Computers (ACSSC), Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 31 October–3 November 2021; pp. 105–112.

- Marques da Silva, M.; Gashtasbi, A.; Dinis, R.; Pembele, G.; Correia, A.; Guerreiro, J. On the Performance of Partial LIS for 6G Systems. Electronics 2024, 13, 1035. [CrossRef]

- Dajer, M.; Ma, Z.; Piazzi, L.; Narayan, P.; Qi, X.; Sheen, B.; Yang, J.; Yue, G. Reconfigurable Intelligent Surface: Design the Channel—A New Opportunity for Future Wireless Networks. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.07408v1.

- Gashtasbi, A.; Marques da Silva, M.; Dinis, R.; Guerreiro, J. On the Performance of LDPC-Coded Large Intelligent Antenna System. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4738. [CrossRef]

- Farsad, N.; Goldsmith, A. Detection Algorithms for Communication Systems Using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2017); Long Beach, CA, USA, 2017.

- Xu, W.; Zhong, Z.; Be’ery, Y.; You, X.; Zhang, C. Joint Neural Network Equalizer and Decoder. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Symposium on Wireless Communication Systems (ISWCS); Lisbon, Portugal, 28–31 August 2018; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Gashtasbi, A.; Marques da Silva, M.; Dinis, R. IRS, LIS, and Radio Stripes-Aided Wireless Communications: A Tutorial. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12696. [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Rusek, F.; Edfors, O. Beyond Massive-MIMO: The Potential of Data-Transmission with Large Intelligent Surfaces. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.02887v1.

- Pavia, J.P.; Velez, V.; Souto, N.; Marques da Silva, M.; Correia, A. System-Level Assessment of Massive Multiple-Input–Multiple-Output and Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces in Centralized Radio Access Network and IoT Scenarios in Sub-6 GHz, mm-Wave, and THz Bands. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1098. [CrossRef]

- Borger, D.; Dinis, R.; Montezuma, P. An MRC-Based Receiver for SC-FDE Modulations with Massive MIMO Schemes. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Global Conference on Signal and Information Processing (Global SIP), Washington, DC, USA, 7–9 December 2016.

- Marques da Silva, M.; Dinis, R.; Guerriero, J. A Low Complexity Channel Estimation and Detection for Massive MIMO using SC-FDE. Telecom 2020, 1, 3–17.

- Marques da Silva, M.; Dinis, R.; Aleixo, J.; Oliveira, L.M.L. On the Performance of LDPC-Coded MIMO Schemes for Underwater Communications Using 5G-like Processing. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5549. [CrossRef]

- Marques da Silva, M.; Dinis, R.; Martins, G. On the Performance of LDPC-Coded Massive MIMO Schemes with Power-Ordered NOMA Techniques. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8684. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Baykas, T.; Funada, R.; Sum, C.S.; Rahman, A.; Lan, Z.; Harada, H.; Kato, S. A SNR Mapping Scheme for ZF/MMSE Based SC-FDE Structured WPANs. In Proceedings of the VTC Spring 2009—IEEE 69th Vehicular Technology Conference, Barcelona, Spain, 26–29 April 2009.

- Montezuma, P.; Borges, D.; Dinis, R. Low Complexity MRC and EGC Based Receivers for SC-FDE Modulations with Massive MIMO Schemes. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Conference on Signal and Information Processing-Global SIP, Washington DC, USA, 7–9 December 2016.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

is defined as.

is defined as.

is the actual output signal from the one iteration MRC/EGC detector, while

is the actual output signal from the one iteration MRC/EGC detector, while  is the estimated output of the neural network (same signal clean of interference).

is the estimated output of the neural network (same signal clean of interference). , processed through the trained model, and recombined to form the estimated complex-valued transmitted signal:

, processed through the trained model, and recombined to form the estimated complex-valued transmitted signal: