Submitted:

12 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

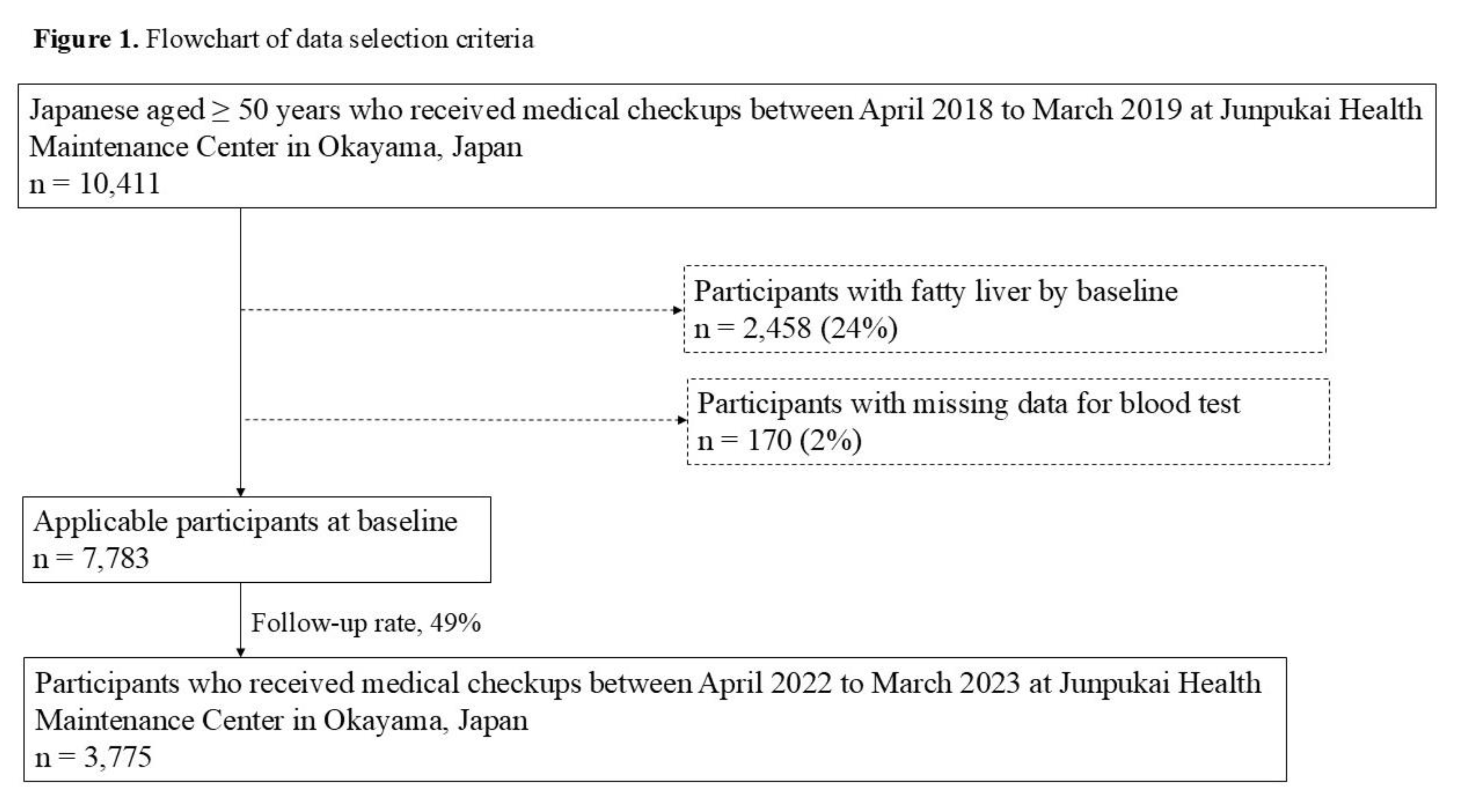

Participants

Assessment of Fatty Liver

Assessment of Body Composition

Assessment of the Serum Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) Level

Assessment of Blood Pressure Levels

Assessment of Chewing Status and Other Items by a Self-Administered Questionnaire

Sample Size

Statistical Analysis

Research Ethics

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allison, M. Fatty liver. Hosp Med. 2004, 65, 609–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, P.; Hellerbrand, C. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2014, 28, 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eguchi, Y.; Hyogo, H.; Ono, M.; Mizuta, T.; Ono, N.; Fujimoto, K.; Chayama, K.; Saibara, T. Prevalence and associated metabolic factors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the general population from 2009 to 2010 in Japan: a multicenter large retrospective study. J Gastroenterol. 2012, 47, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasamori, N. Nationwide results of the 2008 Ningen Dock. Ningen Dokku. 2009, 24, 901–948. [Google Scholar]

- Taniai, M. Epidemiology of NAFLD/NASH. J Society Internal Medicine. 2020, 109, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Steven, F.; Rudolph, B. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Pediatr Rev. 2015, 36, 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Roeb, E. NASH (non-alcoholic steatohepatitis): fatty liver or fatal liver disease? Zentralbl Chir. 2014, 139, 168–174. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Bu, Y.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.; Sun, D.; Zheng, M. Association of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease with kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2022, 18, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, A.; Rosso, C.; Elisabetta, B. Liver cancer: Connections with obesity, fatty liver, and cirrhosis. Annu Rev Med. 2016, 67, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwai, K.; Azuma, T.; Yonenaga, T.; Ekuni, D.; Watanabe, K.; Obora, A.; Deguchi, F.; Kojima, T.; Morita, M.; Tomofuji, T. Association between self-reported chewing status and glycemic control in Japanese adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 9548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motokawa, K.; Mikami, Y.; Shirobe, M.; Edahiro, A.; Ohara, Y.; Iwasaki, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Kawai, H.; Kera, T.; Obuchi, S.; Fujiwara, Y.; Ihara, K.; Hirano, H. Relationship between chewing ability and nutritional status in Japanese older adults: A cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwai, K.; Azuma, T.; Yonenaga, T.; Sasai, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Deguchi, F.; Obora, A.; Kojima, T.; Tomofuji, T. Relationship between chewing status and fatty liver diagnosed by liver/spleen attenuation ratio: A cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 20, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Standard health examination and health guidance program for fiscal year 2008. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-10900000-Kenkoukyoku/00_3 (Accessed on , 2025). 13 March.

- Suzuki, S.; Sano, Y. Guidebook for specified health examination and specified health guidance leading to results. Chuohoki: Tokyo, Japan, 2014.

- Miyano, T.; Anada, T.; Furuta, M.; Yamashita, Y. Prefectural differences in chewing ability in questionnaire for specific health checkup and exploring related factors. J Dent Hlth. 2023, 73, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Iyota, K.; Mizutani, S.; Oku, S.; Asao, M.; Futatsuki, T.; Inoue, R.; Imai, Y.; Kashiwazaki, H. A cross-sectional study of age-related changes in oral function in healthy Japanese individuals. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japan Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for NASH/NAFLD in 2020. https://www.jsge.or.jp/committees/guideline/guideline/pdf/nafldnash2020.pdf#page=58 (Accessed on , 2025). 29 March.

- Japan Society for the Study of Obesity. Obesity clinical practice guidelines in 2016. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/naika/107/2/107_262/_pdf/-char/ja (Accessed on , 2025). 18 March.

- Kawahara, T.; Imawatari, R.; Kawahara, C.; Inazu, T.; Suzuki, G. Incidence of type 2 diabetes in pre-diabetic Japanese individuals categorized by HbA1c levels: A historical cohort study. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0122698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The International Expert Committee. International expert committee report on the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. <i>Diabetes Care</i>. <b>2009</b>, 32. The International Expert Committee. International expert committee report on the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care, 1327. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Crimmins, E. Blood pressure and mortality: Joint effect of blood pressure measures. J Clin Cardiol Cardiovasc Ther. 2020, 2, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, T.; Irie, K.; Watanabe, K.; Deguchi, F.; Kojima, T.; Obora, A.; Tomofuji, T. Association between chewing problems and sleep among Japanese adults. Int J Dent. 2019, 2019, 8196410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, Q.; Shereen, A.; Estabraq, M.; Jood, S.; Abdelfattah, AT.; Adil, A. Electronic cigarette among health science students in Saudi Arabia. Ann Thorac Med. 2019, 14, 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kudo, A.; Asahi, K.; Satoh, H.; Iseki, K.; Moriyama, T.; Yamagata, K.; Tsuruya, K.; Fujimoto, S.; Narita, I.; Konta, T.; Kondo, M.; Shibagaki, Y.; Kasahara, M.; Watanabe, T.; Shimabukuro, M. Fast eating is a strong risk factor for new-onset diabetes among the Japanese general population. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 8210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, Y.; Kashima, H.; Hayashi, N. The number of chews and meal duration affect diet-induced thermogenesis and splanchnic circulation. Obesity. 2014, 22, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, J.; Cummings, E.; Baskin, G.; Barsh, S.; Schwartz, W. Central nervous system control of food intake and body weight. Nature. 2006, 443, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakata, T.; Yoshimatsu, H.; Kurokawa, M. Hypothalamic neuronal histamine: implications of its homeostatic control of energy metabolism. Nutrition. 1997, 13, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tada, A.; Miura, H. Systematic review of the association of mastication with food and nutrient intake in the independent elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014, 59, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, C.; Chang, L. Association of dental prosthetic condition with food consumption and the risk of malnutrition and follow-up 4-year mortality risk in elderly Taiwanese. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011, 15, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, M.; Kikutani, T.; Yoshikawa, M.; Tsuga, K.; Kimura, M.; Akagawa, Y. Correlation between dental and nutritional status in community-dwelling elderly Japanese. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2011, 11, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Weyant, J.; Corby, P.; Kritchevsky, B.; Harris, B.; Rooks, R.; Rubin, M.; Newman, B. Edentulism and nutritional status in a biracial sample of well-functioning, community-dwelling elderly: the health, aging, and body composition study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004, 79, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Hsu, W.; Hollis, J. Increasing the number of masticatory cycles is associated with reduced appetite and altered postprandial plasma concentrations of gut hormones, insulin and glucose. Br J Nutr. 2013, 110, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, G.; Schattenberg, J.; Leclercq, I.; Yeh, M.; Goldin, R.; Teoh, N.; Schuppan, D. Mouse models of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Toward optimization of their relevance to human nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2019, 69, 2241–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z.; Xia, B.; Wu, J.; Zhao, X.; He, X.; Wen, X.; Yuan, C.; Pang, T.; Xu, X. Associations between abdominal obesity, chewing difficulty and cognitive impairment in dementia-free Chinese elderly. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2023, 38, 15333175231167118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.; Araujo, D.; Scudine, K.; Prado, D.; Lima, D.; Castelo, P. Chewing in adolescents with overweight and obesity: An exploratory study with behavioral approach. Appetite. 2016, 107, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, T.; Ueno, M.; Shinada, K.; Ohara, S. ; Kawaguchi, Yoko. Validity of self-reported masticatory function in a Japanese population. J Dent Hlth.

- Anzai, K.; Sakai, H.; Kondo, E.; Tanaka, H.; Shibata, A.; Hashidume, M.; Kurita, H. The effectiveness of a self-reported questionnaire on masticatory function in health examinations. Odontology. 2024, 112, 1361–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonardo, A.; Nascimbeni, F.; Ballestri, S.; Fairweather, D.; Win, S.; Than, T.; Abdelmalek, M.; Suzuki, A. Sex differences in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: state of the art and identification of research gaps. Hepatology. 2019, 70, 1457–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamura, S.; Kawaguchi, T.; Nakano, D.; Tomiyasu, Y.; Yoshinaga, S.; Doi, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Anzai, K.; Eguchi, Y.; Torimura, T. Prevalence and independent factors for fatty liver and significant hepatic fibrosis using B-mode ultrasound imaging and two dimensional-shear wave elastography in health check-up examinees. J Med Kurume. 2021, 66, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhu, Z.; Mao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Du, J.; Tang, X.; Cao, H. HbA1c may contribute to the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease even at normal-range levels. Biosci Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20193996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Dohi, M.; Watanabe, M.; Goromaru, N.; Kanasaki, M.; Shirakashi, M.; Inagawa, M.; Masuda, T.; Takeda, T. Fatty liver has the same background characteristics in those under their ideal weight and the general population. J Ningen Dock and Preventive Medical Care. 2024, 39, 440–446. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, M.; Alfaddagh, A.; Elajami, T.; Ashfaque, H.; Haj, I.H.; Welty, F. Diastolic blood pressure predicts coronary plaque volume in patients with coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2018, 277, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, G.; Chen, Z.; She, Z.; Cai, J.; Li, H. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: an emerging driver of hypertension. Hypertension. 2020, 75, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trovato, G. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and Atherosclerosis at a crossroad: The overlap of a theory of change and bioinformatics. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2020, 11, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The National Health and Nutrition Survey Japan 2019. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10900000/000687163 (Accessed , 2025). 13 March.

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S. Applied logistic regression, 2nd edition. John Wiley and Sons 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Faienza, M.; Baima, J.; Cecere, V.; Monteduro, M.; Farella, I.; Vitale, R.; Antoniotti, V.; Urbano, F.; Tini, S.; Lenzi, F.; Prodam, F. Fructose intake and unhealthy eating habits are associated with MASLD in pediatric obesity: A cross-sectional pilot study. Nutrients. 2025, 17, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Chewing status | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Good(n = 3,234) | Poor(n = 541) | ||

| Gender a | 1,345 (42%) | 275 (50%) | < 0.001* |

| Age (years) | 57 (53, 62) | 56 (52, 62) | 0.024* |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.0 (20.1, 24.1) | 19.7 (21.6, 23.7) | < 0.001* |

| HbA1c level (%) | 5.6 (5.5, 5.9) | 5.7 (5.5, 5.9) | 0.879 |

| Smoking habit b | 443 (14%) | 138 (25%) | < 0.001* |

| Drinking habit b | 906 (28%) | 198 (37%) | < 0.001* |

| Exercise habit b | 1,069 (33%) | 171 (32%) | 0.507 |

| Physical activity b | 823 (25%) | 124 (23%) | 0.209 |

| Systolic blood pressure level (mmHg) | 120 (107, 133) | 114 (102, 128) | < 0.001* |

| Diastolic blood pressure level (mmHg) | 75 (67, 84) | 72 (65, 80) | < 0.001* |

| Sleep status | |||

| Well | 2,056 (64%) | 285 (53%) | < 0.001* |

| Poor | 1,178 (36%) | 256 (47%) | |

| Eating speed | |||

| Slowly | 275 (8%) | 61 (11%) | 0.098 |

| Medium | 1,925 (60%) | 318 (59%) | |

| Quickly | 1,034 (32%) | 162 (30%) | |

| Snacking habit | |||

| None | 591 (18%) | 93 (17%) | 0.686 |

| Sometimes | 1,657 (51%) | 274 (51%) | |

| Daily | 986 (31%) | 174 (32%) | |

| Skipping breakfast habit | |||

| < 3 times / week | 2,939 (91%) | 467 (86%) | < 0.001* |

| ≥ 3 times / week | 295 (9%) | 74 (14%) | |

| Dinner within 2 hours before bedtime habit | |||

| < 3 times / week | 2,496 (77%) | 367 (68%) | < 0.001* |

| ≥ 3 times / week | 738 (23%) | 174 (32%) | |

| Chewing status at baseline | p-value* | ||||

| Good(n = 3,234) | Poor(n = 541) | ||||

| Fatty liver at follow-up | Absence | 2,980 (92%) | 477 (88%) | 0.002* | |

| Presence | 254 (8%) | 64 (12%) | |||

| *p < 0.05, using Fishers exact test. | |||||

| Factor | ORs | 95% CIs | p-value | |

| Gender | Female | 1 | (reference) | < 0.001 |

| Male | 2.165 | 1.712-2.738 | ||

| Age (years) | 0.968 | 0.948-0.988 | 0.002 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | < 25.0 | 1 | (reference) | < 0.001 |

| 25.0 ≤ | 2.281 | 1.764-2.950 | ||

| HbA1c level (%) | < 6.5 | 1 | (reference) | 0.550 |

| 6.5 ≤ | 0.844 | 0.484-1.472 | ||

| Smoking habits | Absence | 1 | (reference) | 0.006 |

| Presence | 1.496 | 1.123-1.993 | ||

| Drinking habit | Absence | 1 | (reference) | 0.072 |

| Presence | 1.251 | 0.980-1.597 | ||

| Exercise habit | Presence | 1 | (reference) | 0.054 |

| Absence | 1.284 | 0.995-1.657 | ||

| Physical activity | Presence | 1 | (reference) | 0.360 |

| Absence | 1.136 | 0.865-1.481 | ||

| Systolic blood pressure level (mmHg) | 1.007 | 1.001-1.013 | 0.020 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure level (mmHg) | 1.019 | 1.010-1.029 | < 0.001 | |

| Sleep status | Well | 1 | (reference) | 0.038 |

| Poor | 1.278 | 1.013-1.613 | ||

| Chewing status | Good | 1 | (reference) | 0.002 |

| Poor | 1.574 | 1.177-2.105 | ||

| Eating speed | Not quickly | 1 | (reference) | 0.508 |

| Quickly | 1.086 | 0.851-1.386 | ||

| Snacking habit | Not daily | 1 | (reference) | 0.327 |

| Daily | 0.881 | 0.683-1.136 | ||

| Skipping breakfast habit | < 3 times / week | 1 | (reference) | 0.006 |

| ≥ 3 times / week | 1.594 | 1.140-2.229 | ||

| Dinner within 2 hours before bedtime habit | < 3 times / week | 1 | (reference) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 3 times / week | 1.671 | 1.307-2.136 | ||

| Abbreviations: ORs, odds ratios; CIs, confidence intervals; BMI, body mass index; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c.. | ||||

| Factor | ORs | 95% CIs | p-value | |

| Gender | Female | 1 | (reference) | < 0.001 |

| Male | 1.830 | 1.414-2.368 | ||

| Age (years) | 0.969 | 0.948-0.991 | 0.006 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | < 25.0 | 1 | (reference) | < 0.001 |

| 25.0 ≤ | 1.975 | 1.510-2.585 | ||

| Smoking habits | Absence | 1 | (reference) | 0.951 |

| Presence | 1.010 | 0.737-1.384 | ||

| Systolic blood pressure level (mmHg) | 0.995 | 0.986-1.005 | 0.343 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure level (mmHg) | 1.017 | 1.002-1.032 | 0.025 | |

| Sleep status | Well | 1 | (reference) | 0.135 |

| Poor | 1.200 | 0.945-1.524 | ||

| Chewing status | Good | 1 | (reference) | 0.012 |

| Poor | 1.475 | 1.090-1.996 | ||

| Skipping breakfast habit | < 3 times / week | 1 | (reference) | 0.257 |

| ≥ 3 times / week | 1.227 | 0.861-1.749 | ||

| Dinner within 2 hours before bedtime habit | < 3 times / week | 1 | (reference) | 0.174 |

| ≥ 3 times / week | 1.201 | 0.922-1.565 | ||

| Abbreviations: ORs, odds ratios; CIs, confidence intervals; BMI, body mass index. Adjustment for gender, age, BMI, smoking habits, systolic blood pressure level, diastolic blood pressure level, sleep status, chewing status, skipping breakfast habit, and dinner within 2 hours before bedtime habit. Hosmer-Lemeshow fit test; p = 0.489. | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).