1. Introduction

According to Gardner [

1] , true learning occurs when an individual comprehends a concept deeply enough to memorize the information related to the concept and retrieve it to apply appropriately in a novel situation. Transfer of learning (TL) refers to the ability to apply acquired knowledge and skills in new and diverse contexts. This ability is crucial for success in real-world scenarios, allowing individuals to adapt and perform effectively in various environments [

2]. Achieving TL is the ultimate goal of any educational system as TL extends beyond simple memorization and recall; it involves making meaningful connections between prior and new knowledge, critically evaluating information, and applying learned concepts across different domains [

3]. Despite its importance, achieving TL is not always straightforward. The extent to which knowledge and skills transfer to new contexts depends on various factors such as the similarity between the learning tasks and the instructional conditions under which learning occurs.

TL is commonly classified as ‘near transfer’ and ‘far transfer’. Near transfer occurs when the source and target tasks share significant similarities (e.g., learning Latin and Spanish). For example, Pellegrino et al. [

4] suggest that learning ‘A’ affects learning ‘B’ only to the extent to which ‘A’ and ‘B’ have common elements. Thus, task similarity is one of the key conditions under which TL can be demonstrated [

5]. In contrast, far transfer involves applying knowledge across substantially different domains, involving the development of abstract principles and cognitive strategies [

6]. However, far transfer is challenging to achieve as it requires extensive cognitive processing and abstract reasoning [

7]. Thorndike's [

8] identical elements theory proposes that shared common features (i.e., the similarity between the source and the target domains) determine the extent to which learned skills transfer to new skills. Therefore, far transfer may rarely occur [

7,

9].

In addition to task similarity, the level of abstraction of the learned material, the complexity of the learning material, the degree of original learning, and the learning context also influence TL [

2]. Individual differences in a learner’s prior knowledge and cognitive abilities can also impact the transfer process. Educational strategies that facilitate TL need to consider these factors. For example, analogical reasoning, where learners identify similarities between previously learned concepts and new ones, can aid in transferring knowledge across domains [

10,

11]. Cognitive flexibility (the ability to switch between different problem-solving approaches), has also been shown to promote TL [

12]. Additionally, providing multiple examples enhances the learner‘s ability to apply knowledge flexibly in diverse situations [

13].

1.1. Challenges in Studying TL

The concept of TL has been studied by scholars, educators, and cognitive scientists for over a century [

14]. Despite its longstanding presence in academic research, there remains a significant lack of research findings that can effectively aid learners in transferring their knowledge or skills from one context to another [

4]. Additionally, understanding the factors hindering or facilitating TL is still limited [

15]. One of the main reasons is that measuring TL using traditional methods such as examinations, tests, surveys, or interviews primarily tests recall and memorization but does not provide insights into how TL occurs and do not capture the subtle changes and differences in cognitive processes underlying learner performance [

16]. Second, self-reported data from surveys and interviews may introduce bias due to factors such as personal preferences and cultural background while examination and test may not be an accurate measure of TL and actual student progress as well [

17,

18,

19].

Other approaches to studying and measuring TL include transfer tests and transfer-appropriate processing (TAP). Transfer tests assess how learners apply previously learned knowledge to a new and unfamiliar situation. For instance, in Gick et al’s study [

11], participants were asked to solve a medical problem that involved a tumor treatable by radiation. Some participants were exposed to a similar problem while serving in the military. They were given a hint about using an analogy-based problem-solving strategy and were more successful in transferring their existing knowledge to the new problem to solve it compared to participants who were not exposed to a relevant prior experience.

TAP provides another perspective on measuring TL. It suggests that the best memory performance occurs when the cognitive processes during information encoding (initial learning) and information retrieval (assessment for later use) are similar [

20]. TAP posits that memory performance depends not just on associating meaning with information (depth of process) but also on the relationship between encoding and retrieval. If the cognitive processes used during encoding align with those during retrieval, memory will accurately recall the relevant information and TL will occur [

21]. However, the effectiveness of TAP as a measure of TL requires careful instructional or experimental design to ensure that learners engage in similar cognitive processes both when learning and when testing their learning.

1.2. Cognitive Load

Cognitive Load Theory (CLT), proposed by John Sweller posits a relationship between cognitive load and learning effectiveness [

22]. Cognitive load is the total amount of resources in the brain’s working memory that are used while performing a cognitive task; learning is efficient when cognitive load is aligned with the individual's cognitive capacity. Therefore, managing cognitive load is essential for successful learning [

23].

CLT categorizes cognitive load into three distinct types: intrinsic, extrinsic, and germane. Intrinsic cognitive load (ICL) is related to the task's inherent complexity. It refers to the amount of mental effort in learning cognitively demanding content. Perceived CLT is less affected by the instructional design than by the number of interactions such as between the type of the new information and the learner’s prior knowledge. For instance, learning complex mathematical concepts demands more cognitive resources, regardless of how the material is presented [

24]. By contrast, extraneous cognitive load (ECL) depends on how information is presented to learners. If the instructional materials are poorly designed, communicated and/or organized, ECL increases and may hinder learning. Finally, germane cognitive load (GCL) refers to the effort placed on memory to form new connectivity schemas and how information is processed in the human brain’s long-term memory [

23].

Cognitive overload occurs when all three types are present: the learner gets overwhelmed with the learning due to the increased mental effort. The learning task overloads the student’s working memory and impedes information retention; the potential for TL decreases [

25]. Studies have found that a low cognitive load indicates that a learner has knowledge or expertise related to the task whereas a high cognitive load often reflects a lack of relevant knowledge or expertise.

Physiological measures using modern neuroimaging techniques have demonstrated the feasibility of using devices such as portable electroencephalogram (EEG) devices to measure objectively cognitive load. For example, EEG devices were used effectively to capture real-time neural activity related to mental workload and learning performance [

17,

26]. Furthermore, EEG data were used in machine learning (ML) and brain-inspired computational algorithms to evaluate working memory performance by assessing cognitive load [

27]. Similarly, EEG data were used to classify learner expertise and compare the performance between novice and expert groups in mathematical learning tasks [

28].

1.3. Learning Programming as a Context for Studying TL

Developing programming knowledge and skills is an essential part of today’s computer science education and professional training. As a knowledge domain, learning a programming language is characterized by a combination of problem-solving tasks that require a practical application of theoretical concepts. However, mastering programming languages is often difficult for learners. This can be attributed to several factors. First, learners need to understand the language's logic, syntax, and semantics which can be quite complex [

29]. Second, programming requires learners to think logically and systematically, which can be challenging for some learners [

30]. In addition, programming languages constantly evolve, which demands staying updated with the latest developments to remain relevant in the job market [

31].

The challenges and cognitive demands associated with learning programming languages and the characteristics of the programming knowledge domain make it a suitable context for studying the TL phenomenon. Research results indicate that the transfer of skills and knowledge within the same domain is more efficient compared to cross-domain transfer [

32,

33]. Therefore, it may be expected that an observable TL will occur when a learner studies a programming language after having already acquired some programming skills.

1.4. Research Question and Contributions

This study examines the cognitive and neural mechanisms underlying TL in the context of learning a programming language. According to CLT, working memory load and task performance are inversely related [

18]. Therefore, efficient memory use is paramount to good task performance. Memory efficiency determines how well prior knowledge is stored, retrieved, and applied to a new context; efficient memory retrieval is essential for transferring learning, as it allows learners to apply previously acquired knowledge to new problems and solve them effectively. Therefore, the main research question of this study was formulated as: ‘What is the effect of prior knowledge on memory efficiency when learning a new programming language?’

Memory efficiency is a factor influencing learning performance as learning performance quality depends on the cognitive load experienced by the learner (cognitive load is the amount of mental effort required for comprehension) [

25]. Higher cognitive load indicates increased mental effort and tends to hinder retention and understanding; lower cognitive load indicates reduced mental effort and better performance [

60]. In particular, the study hypothesizes that:

H1: Having prior programming knowledge reduces cognitive load.

The study contributes to the understanding of TL as a process facilitated by prior programming knowledge using a cognitive computing approach. The study validates the use of cognitive load as an indicator of memory efficiency in the context of studying a programming language. It identifies neural patterns in the alpha and theta waveband frequencies and demonstrates the effect of prior knowledge on cognitive load. Furthermore, the study develops an SNN-based methodology for investigating TL processes that can be generalized and used in other educational domains.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Using EEG to Collect Brain Activity Data

The human brain is always active, analyzing and responding to internal and external stimulants, learning and changing continuously through learning [

34,

35]. When learning occurs, the connections between the neurons in the brain (synapses) change. The ability of the brain to create new connections among neurons causing transformative changes in the internal structure of the existing synapses is called synaptic plasticity [

36,

37]. Synaptic plasticity is the biological mechanism for learning and memorizing.

Brain activity data gathered through neuroimaging techniques such as EEG and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) can be used to study the changes in neuronal connections and how learning occurs in the brain [

16,

19].

EEG is a technique for measuring the electrical activity in the brain with high temporal resolution, capturing neural dynamics in milliseconds (ms) [

38]. This is essential for studying fast-paced learning processes, enabling real-time tracking of brain activity changes in response to stimuli in designed tasks [

39]. Unlike fMRI, which provides high spatial but lower temporal resolution, EEG is particularly well-suited for capturing immediate changes in neural activity during cognitive tasks, making it an effective tool for analyzing TL. Additionally, EEG is easier to use and more cost-effective than fMRI. EEG has been widely used in prior research in areas such as health sciences, medicine, and education [

38,

39,

40]. For example, EEG was used effectively in [

41] to measure changes in brain oscillations associated with memory encoding. In [

42], EEG was successfully used to explore the neural activities underlying motivation-related cognitive processes while solving mathematical problems and revealing specific brainwave patterns and activated brain regions. Due to its advantages and feasibility, EEG was chosen as the data collection method in this study.

Studies involving EEG as a data collection method have utilized brain wave frequency-based features such as the alpha, beta, and theta power ratios to measure cognitive workload and provide insights into a learner’s mental state while performing learning tasks [

43,

44]. These ratios indicate how the power distribution across different frequency bands reflects cognitive processing demands. According to their findings, the ratios between alpha and theta power and between the beta and alpha power and several related combinations can be used as learners’ task engagement and cognitive load indicators [

43]. Another research [

45] examined the changes in the frequency bands (e.g., the delta wave band); it showed that the variations in the frequency bands correlated with different levels of memory workload. For example, an increase in the alpha waveband and a decrease in theta waveband indicated good task performance [

46].

2.2. Using Spiking Neural Networks for EEG Data Analysis

The TL process relates to both space and time activities in the brain. Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) can be used to capture the time-space relationship patterns emerging from neuronal activity data. SNNs were developed as the third generation of artificial neural networks (ANNs). SNNs were inspired by how biological neurons use a series of action potentials (spikes) to communicate and transform information through synaptic changes [

47]. SNNs simulate realistically neural processing; they encode information using discrete spike trains, which capture the spatial and temporal features of neuronal activity data [

48]. By using spike timing and rate-based computation, SNNs achieve low energy consumption and faster learning and are highly effective when used to analyze spatiotemporal brain data (STBD) including EEG data, where the precision of the temporal data analysis is important [

49,

50].

This study uses the SNN architecture NeuCube [

51] to analyze experimentally gathered EEG data. NeuCube captures both the spatial and temporal relationships in EEG signals to provide an advanced representation of the neural processes underlying incremental cognition and learning [

52]. NeCube’s biological plausibility makes it particularly effective when studying the neural basis of memorizing, cognitive load, and TL.

2.3. Experiment Design

2.3.1. Research Participants

The research participants comprised 21 males and 5 females, with the majority (22) aged between 18 and 21 years, one was over 40, and three aged between 22 and 30. All participants were university undergraduates, enrolled in a first-year computer programming (P1) course where they would learn the C programming language.

The participants completed a screening questionnaire to gather demographic data and to gauge the type and level of their existing programming knowledge. The purpose of the screening was to exclude participants with sufficient prior knowledge of the C language and to ensure that participants had comparable prior knowledge regarding the number and level of programming languages they had learned.

All 26 participants attended the first session of the experiment, which was held before starting the P1 course. Only 13 participants returned for the second session of the experiment, which was conducted after the P1 course was completed.

2.3.2. Learning Tasks Design and Presentation

The design of the learning tasks was partially inspired by prior research [

16,

19]. The 17 programming comprehension tasks were formatted as multiple-choice questions. Participants were presented with C programming language code snippets designed to produce an output. After reviewing the code, participants were required to select the correct output from four possible answers. This format minimized the physical movement during EEG recording as participants were not required to type their answers. The learning tasks were organized in order of increasing difficulty and presented to the participants in the same predetermined order to ensure all participants worked through the tasks in the same sequence. During the experiment, the tasks were displayed on a laptop monitor. Participants were given unlimited time to solve the programming problems; this reduced time-limit pressure.

An instructional page was presented at the start of each individual experiment, with an OK button signaling the participant to proceed to the first multiple-choice question. The participant was instructed to select an answer using a mouse click. Once the answer was selected, a screen displaying the word Relax appeared, followed by the automatic presentation of the next task after a brief two-second interval. To provide adequate temporal separation, an intertrial interval of at least 1000 ms between the end of a trial and the start of the subsequent one is commonly recommended [

53](p.64)). This process continued throughout the 17 programming comprehension tasks. A page signaling the end of the experiment appeared once the participant had answered the last question. The calculated total score was presented and stored for further reference.

The programming tasks were presented using the open-source OpenSesame software platform for experiment support [

54]. Two event markers were configured for each programming task to indicate the start and end of the task. The end of each task was marked when the participant clicked on their selected answer to the programming question; the start of each question was automatically marked after the two-second relaxation period.

2.3.3. Data Collection Method

For this study, the researcher collected primary data using an EEG device called Emoiv Epoch X [

55]. It is a 14-channel EEG device that provides detailed brain activity data with high resolution. The device works with 14 electrodes: AF3, F7, F3, FC5, T7, P7, O1, O2, P8, T8, FC6, F4, F8, AF4. The electrodes are arranged according to the international 10-20 system to ensure standardized data collection from 14 locations on the scalp. The device is designed to detect six frequency bands, which include delta (0.5-4 Hz), theta (4-8 Hz), alpha (8-12 Hz), beta low (12-16 Hz), beta high (16-25), and gamma (25-45 Hz).

The EEG data were recorded at two different time points, capturing participant brain activity before and after completing the P1 course. The first session (at time point T1 – pre-P1 course) was conducted before the start of the 12-week P1 course. The second session (at time point T2 – post-P1 course) took place after the course completion. Thus, the study data comprised 39 datasets: 26 datasets that were collected at time point T1 and 13 datasets that were collected at time point T2.

2.4. Data Pre-Processing and Data Sampling

Standard EEG filtering techniques, such as band-pass filtering and artifact removal using Independent Component Analysis (ICA) from MATLAB's EEGLAB toolbox, were applied to remove noise from the data. Next, each of the 39 sets of experimentally gathered data was used to generate spatiotemporal samples for input to NeuCube.

A collection of 17 samples (each corresponding to one of the questions in the programming) was extracted from each of the 39 datasets. The sample contained the brain activity data gathered in a 5 sec interval (3 sec before and 2 sec after the second marker). As the EEG drive collected brain activity data every 4 msec, each sample contained data corresponding to 1250 time points. The specific interval described above was chosen as it comprises the important periods immediately before and after the participant makes a decision about the answer to the question in the programming task. Although there are no strict guidelines about the interval length [

53], a 5-second interval was deemed appropriate given that the relaxation period after the second marker was 2 sec.

The resulting spatiotemporal samples were formatted for input into NeuCube. All samples were saved as CSV files. Each CVS file comprised 1250 rows representing temporal features (timeline points), while the spatial features varied based on the focus of each analysis. In identifying the most active brain regions during programming tasks (section 3.1), all 14 spatial features were used, with each column corresponding to one of the 14 EEG channels. To investigate the effect of prior programming knowledge on the cognitive load at time points T1 and T2 (sections 3.2 and 3.3), the spatial features (EEG channels F7 and T7) were represented by six spectral features, corresponding to the EEG frequency bands delta, theta, alpha, beta low, beta high, and gamma.

3. Results

To test hypothesis H1, this study conducted three analyses of the data collected at time points T1 (pre-course) and T2 (post-course). The first analysis aimed to identify the most active brain regions and their corresponding EEG channels during programming learning tasks. The second analysis compared the brain activity patterns of participants with or without prior programming knowledge before the start of the course, using the data from the EEG channels that corresponded to the most active brain regions (F7 and T7). The third analysis compared the neuronal change patterns underlying STBD across the two time points T1 and T2. Similar to the second analysis, the models were developed using the data from EEG channels F7 and T7 (representing the most active areas of the brain during the 5-second interval around the decision-making timepoint).

3.1. Identifying the Most Active Brain Regions

This analysis involved the samples derived from the 26 data collected at time point T1. Participants were divided into two groups based on the total score they achieved during the experiment. Participant scores varied between 2 and 11; the median score of seven was used as a threshold. A total of 14 participants scored seven or below; they were categorized as having insufficient prior knowledge (IPK). The 12 participants who scored above seven were classified as having sufficient prior knowledge (SPK). The aim of the analysis was to find out, for each individual IPK and SPK participant, which brain region(s) were most active when the participants were answering the programming tasks questions.

Each participant’s dataset (e.g., the collection of 17 samples) was processed as follows. First, the samples were loaded into the input encoding module of NeuCube. The continuous input data were converted into discrete spike trains using the threshold-based representation (TBR) encoding algorithm. The threshold was set to the default value of 0.5. The TBR algorithm was chosen for its precision in capturing significant signal changes over time. Its self-adaptive thresholding is well-suited for dynamic EEG data analyses as it allows to distinguish between excitatory and inhibitory neural activity by setting higher thresholds for excitatory spikes and lower (or negative) thresholds for inhibitory spikes [

56].

For each dataset, the discrete spike trains were initialized by mapping the 14 EEG channels as input neurons into NeuCube’s three-dimensional recurrent spiking neural network cube (SNNc). The SNNc is an SNN architecture, designed to replicate the small-world connectivity structure of the brain and provide biologically plausible neuronal activity representations [

56,

57]. It mirrors the networks of densely interconnected brain neurons (particularly in regions that are functionally or structurally related in which neuronal connectivity is high) and preserves the spatial organization of the EEG channels.

Next, each resulting SNN model was trained using unsupervised learning to capture the temporal and spatial relationships within the data. During this stage, the temporal relationships in each dataset are adjusted by neuronal connection weights based on the Spike Time Dependent Plasticity (STDP) rule. STDP is a biologically inspired learning mechanism that strengthens the synaptic connections between highly interactive neurons; this way, SNNc learns autonomously spatiotemporal patterns in the data. The process mirrors synaptic adaptation in the brain, where connections are modified based on the timing of neuronal spikes [

57,

58].

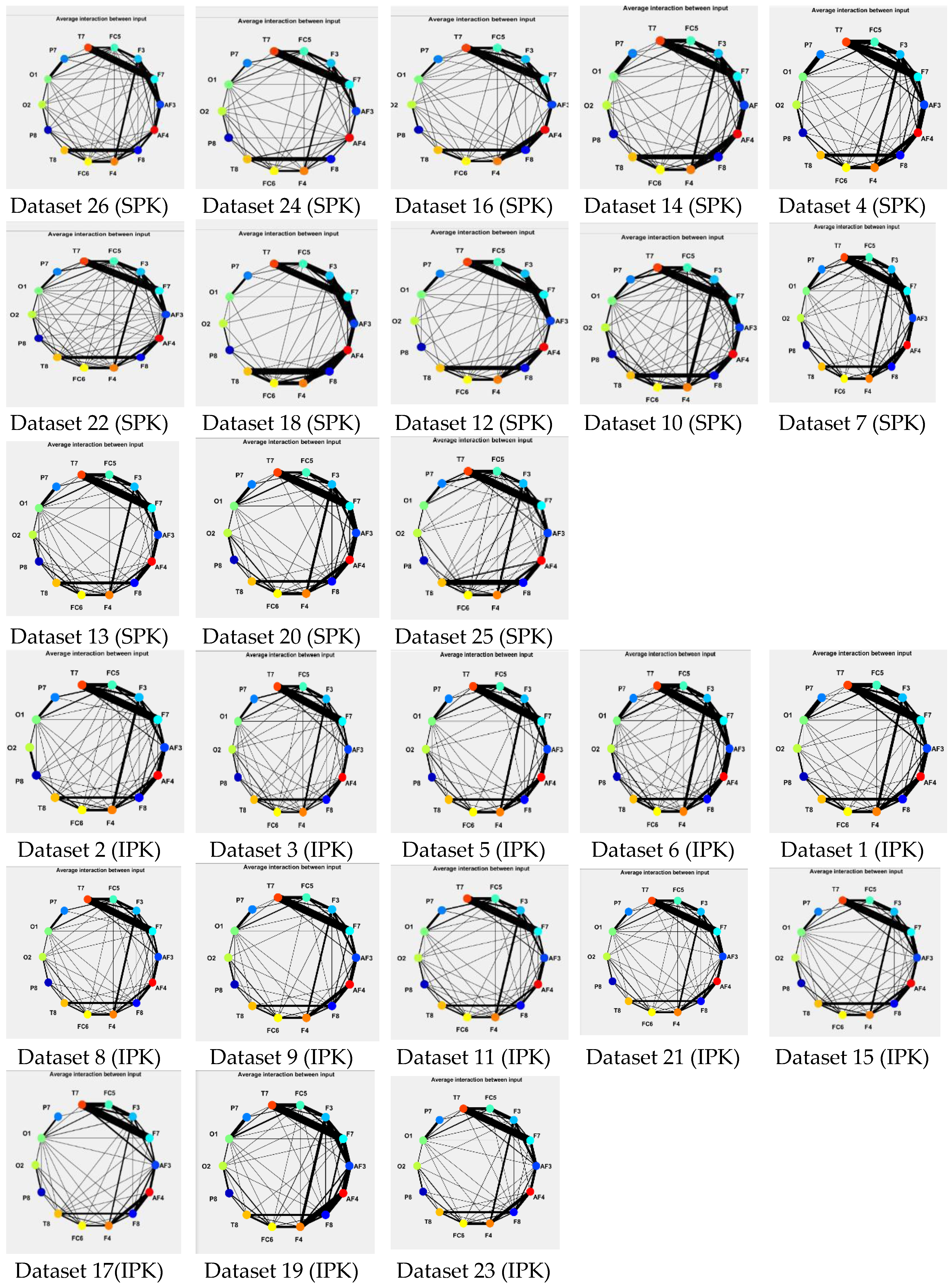

The resulting SNNc comprised 14 input neurons, each corresponding to one of the EEG channels. The input neuron sits at the center of a cluster, surrounded by the neighboring neurons it interacts with mostly. The interactions were visualized graphically using the calculated average input neuron interaction index (based on the average spike exchange of the input neuron with its neighbors during the EEG signal processing (

Figure 1). The 14 input neurons in the diagrams correspond to the 14 spatial sampled features (i.e., EEG channels). The lines connecting the neurons represent the interactions between them. The thicker lines indicate a higher interaction level, meaning more information was exchanged among the two connected neuron clusters.

The models indicated significant input neuron interaction and spike activities in the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. Across all participants, the highest level of information signal exchange was observed in the brain's left hemisphere, between the input neurons corresponding to EEG channels F7 and T7.

EEG channel T7 captures signals from the part of the brain’s left temporal lobe which is involved in comprehending auditory and visual perceptions (e.g., reading and word recognition), visual linguistic perception, long-term memory, and comprehension [

59]. Channel F7 is located in the left frontal lobe of the brain. This part of the brain creates and controls spoken and written language output and is responsible for attention-gaining working memory, and decision-making. These two most active clusters were selected for the subsequent analyses as the activities represented by the EGG data (e.g., comprehension, memorizing, and retrieving information) occur during the TL process.

3.2. Computing Neuronal Activity Patterns at Time Point T1

In this analysis, two comparative studies were carried out. The first comparative study examined the sample data extracted from EEG channel F7 at time point T1 (pre-course). It examined and compared the neural activities represented by the alpha and theta frequency bands of IPK and SPK participants. The second comparative study explored the EEG channel T7 data at time point T1 (pre-course) in the alpha and theta frequency bands and compared the brain activity patterns of the IPK and SPK.

3.2.1. Change Patterns in the Alpha and Theta Frequency Bands in the Brain’s Left Frontal Lobe (EEG Channel F7) at Time Point T1

The EEG channel F7 data was extracted from the sample collections of the 26 IPK and SPK participants. The encoding, initialization, and unsupervised training were carried out following the process described in sub-section 3.1. However, instead of analyzing the data based on the averaged input neuron interaction index, this study used a neuron proportion indicator as a measure of the neuronal relationship between the alpha and theta frequency bands. The value of the neuron proportion represents the percentage of neurons in the SNNc that belong to this input neuron cluster. For any given input neuron cluster, the neuron proportion indicator shows the strength of neuronal interactions and spike activities of the cluster in relation to the other clusters in the SNNc. For example, the NeuCube output diagrams in

Figure 2 show the EEG channel F7 neuron proportions of six waveband frequencies (alpha, theta, delta, gamma, beta low, beta high) extracted for two participant datasets.

The neuron proportions of the theta and alpha waveband frequencies of each of the IPK and SPK groups are shown in

Table 1. The comparison between the groups indicated that in the IPK group, the average neuron proportion of the theta waveband was 15.07% while the average neuron proportion of the alpha waveband frequency was lower, at 13.85%. The SPK group showed a different pattern: the average neuron proportion of the theta waveband frequency (10.08%) was much lower than the neuron proportion of the alpha waveband frequency which was 17.58%. In other words, in the IPK group, the neuronal activity in the alpha waveband was at a lower level compared to the theta waveband; in the SPK group, the neuron activity in the alpha waveband was at a higher level compared to the theta.

3.2.2. Change Patterns in the Alpha and Theta Frequency Bands in the Brain’s Left Temporal Lobe (EEG Channel T7) at Timepoint T1

This study replicated the study presented in sub-subsection 3.2.1, using the EEG channel T7 data. The neuron proportions of the alpha and theta waveband frequencies for the individual IPK and SPK participants are shown in

Table 2. The comparison of the averaged neuron proportion values showed that in the SPK group, the level of neuronal activity in the theta waveband frequency (13%) was lower than that in the alpha waveband frequency (15.5%). The pattern in the IPK group was similar, with average neuron proportions in the alpha and theta wave band frequencies at 13.7% and 16.5%, respectively.

The neuronal activity pattern in the IPK group did not follow the expected pattern of increased activity in the theta waveband frequency and reduced neuronal activity in the alpha waveband frequency. However, the neuron proportion of the theta waveband in the IPK group was still higher than in the SPK group indicating that IPK participants experience a higher cognitive load than SPK participants.

3.3. Comparing Neuronal Activity Patterns at Time Points T1 and T2

While previous analyses focused on time point T1 (pre-course), this analysis tracked individual participants’ neural activities over time. It identified the change patterns in the alpha and theta wavebands between time point T2 (post-course) compared to time point T1 (pore-course), for each participant. The aim was to assess how these changes aligned with participants’ programming task scores, and whether the inverse relationship between the alpha and theta waveband frequency found in the time point T1 data (refer sub-section 3.2) was manifested at time point T2 as well.

The analysis included two comparative studies, as described below. The first comparative study examined and compared, for each participant, the neural activities represented by the alpha and theta frequency bands extracted from EEG channel F7 at time points T1 and T2. The second comparative study similarly analyzed the data extracted from EEG channel T7.

3.3.1. Change Patterns in the Alpha and Theta Wavebands in the Brain’s Left Frontal Lobe (EEG Channel F7)

The datasets of the 13 individuals who, too, participated in the data collection at both time point T1 and time point T2 were used for this analysis. The data pre-processing and the encoding, initialization, and unsupervised training processes followed the procedures described in subsection 3.1. As in the analyses described in subsection 3.2, the neuron proportion value (as calculated by NeuCube) was used as a neuronal activity indicator.

The neural activity of each participant at each time point was examined to explore the relationship between the alpha and theta waveband frequencies. In particular, the neuron proportion values related to the theta and alpha wavebands were extracted and compared to identify patterns of change in neural activity from time point T1 to time point T2.

The results indicated a reduction in the theta neuron proportion at time point T2 compared to time point T1 for all participants, except for participant 7 (who demonstrated a slight increase in the theta waveband activity). In the alpha waveband frequency, eight participants exhibited an increase in the alpha neuron proportion at T2 while three participants demonstrated a decrease; three participants displayed no change between the time points.

Table 3 shows the neuron proportion values (in percentage) for the alpha and theta wavebands in time points T1 and T2 for each participant.

The participants’ programming task scores were used to investigate the relationship between neural activity change patterns and the knowledge presumably acquired after completing the P1 course. As shown in

Table 3, participants’ programming task scores at time point T2 improved for all participants, except for participants 7 and 25. At time point T2, participant 25's theta neuron proportion decreased slightly (when compared to time point T1) while the alpha neuron proportion remained the same. For Participant 7, the neuron proportion of the theta waveband frequency increased slightly, while the neuron proportion of the alpha waveband showed a slight decrease.

3.3.2. Change Patterns in the Alpha and Theta Wavebands in the Brain’s Left Temporal Lobe (Channel T7)

This study replicated the study described in the preceding section using EEG channel T7 data. As shown in

Table 4, there was a reduction in the neuron proportion of the theta waveband frequency at time point T2 (compared to time point T1) for seven participants. Conversely, there was an increase in the theta neuron proportion for four participants; two participants exhibited no change. Regarding the alpha waveband frequency, at time point T2 there was an increase in the neuron proportion for seven participants (compared to time point T1). For the remaining six participants, a decreased neuron proportion in the alpha waveband frequency at time point T2 was observed (compared to time point T1).

As already noted, the programming task scores at time point T2 were higher than those at time point T1 for all participants except for participants 7 and 25, whose scores were lower (refer to

Table 4). At time point T2, participant 25's theta neuron proportion increased (when compared to time point T1) while the alpha neuron proportion decreased. For Participant 7, the neuron proportion of the theta waveband frequency remained unchanged while the neuron proportion of the alpha waveband showed a slight increase.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

This study examined TL as a process contextualized through prior knowledge. The main research question of the study was formulated as: What is the effect of prior knowledge on memory efficiency when learning a new programming language? To investigate the research question, a working hypothesis H1 was formulated, linking prior knowledge to cognitive load.

A series of experiments were conducted to test hypothesis H1: Having prior programming knowledge reduces cognitive load. The next two sections analyze the experimental results and discuss their implications.

4.1. Prior Knowledge and Cognitive Load

4.1.1. The Effect of Prior Knowledge on Cognitive Load at Time Point T1

To test this hypothesis, we analyzed first the neuronal interactions and spike activity at time point T1 (before participants started the P1 programming course) to determine which brain areas were most active while participants were answering the questions in the programming task. We found that during the time intervals used in the study, the brain's left hemisphere, particularly the regions corresponding to EEG channels F7 and T7, was more engaged compared to the right hemisphere. This finding aligns with previous research results about the involvement of the brain's left frontal and temporal regions in supporting higher-order cognitive processes necessary for programming comprehension. For instance, a study [

60] established that the left inferior frontal gyrus and posterior superior temporal gyrus/sulcus are actively engaged during language comprehension tasks. Similarly, [

61] reported increased activity in the left prefrontal cortex during programming tasks.

The neural change patterns in the brain's left frontal lobe, associated with EEG channel F7 measured at time point T1 indicated that participants who had significant programming knowledge (the SPK group) and participants who did not have significant prior programming knowledge (the IPK group) exhibited distinctly different cognitive load patterns: an increase in cognitive load for IPK participants (average neuron proportion in the theta and alpha waveband frequencies: 15.07% and 13.85%, respectively) and a decrease in cognitive load for SPK participants (average neuron proportion in the theta and alpha waveband frequencies: 10.08% and 17.58% respectively)(refer to

Table 1). The established pattern of inverse relationship between the neuronal activities in the alpha and theta waveband frequencies supports hypothesis H1.

The analysis of neural change patterns in the brain's left temporal lobe, associated with EEG channel T7 measured at point T1 demonstrated a reduced cognitive load in the SPK group, supporting hypothesis H1. However, the results of the individuals in IPK participants provide only partial support for hypothesis H1 as the cognitive load patterns of the IPK group were similar to those of the SPK participants. As shown in

Table 2, the average neuron proportions in the theta waveband frequencies in the IPK and SPK groups are 13.78% and 13.00%, respectively. In alpha, the average neuron proportions of the IPK and SPK groups are 16.50% and 15.50%, respectively.

This inconsistency may be explained by the functional role of the T7 region in the temporal lobe. While the left frontal lobe (the channel F7 region) is highly engaged in executive functions such as decision-making, attention, and working memory, the temporal lobe is more involved in processing auditory and spoken language signals [

62]. Answering the programming task questions requires relatively little processing of such signals; therefore, channel T7 may not capture cognitive load patterns as well as channel F7. Although the neuronal activity pattern in the IPK group did not follow the expected pattern of increased theta and reduced alpha, the comparison of the average neuron proportion in the theta waveband frequency between IPK and SPK participants showed higher neuronal activity in the IPK group. This finding may suggest that IPK participants still experienced higher cognitive loads than the SPK participants.

4.1.2. The Effect of Prior Knowledge on Cognitive Load at Time Point T2

The findings suggest that the 12 weeks of learning programming language enhanced the prior programming knowledge of the majority of the 13 participants. As shown in

Table 3, the comparison of the brain activities associated with EEG channel F7 of nine participants demonstrated the inverse relationship pattern between the theta and the alpha wavebands: a decrease (eight participants) or increase (one participant) in the theta waveband frequency and a corresponding increase or decrease in the alpha waveband frequency. The changing pattern was consistent with the difference between the task scores obtained at the two time points. Ultimately, eight participants experienced reduced cognitive load at time point T2, indicating efficient memory use. These findings align with previous research using cognitive load levels as expertise indicators [

25,

63].

The remaining four participants demonstrated a reduction in the theta and a reduction or no change in the alpha waveband activities. The programming task scores of three of the respective participants were higher at time point T2, which may suggest that they also experienced a lower cognitive load. However, the time point T2 task score of the fourth participant was lower.

The variations in alpha waveband activity among these participants may be explained by the impact of external factors on the experienced cognitive load. While an increase in alpha waveband activity is associated with relaxed alertness and efficient handling of known information [

64], stability or slight activity reductions (particularly when paired with reduced theta activity), may indicate external influences like emotional stress or attentional shift [

65,

66]. For example, participants were very likely to experience attention shifts as the experiment site was not entirely isolated from the noisy campus environment. Overall, the findings of this comparison provide support for hypothesis H1

The comparison of the neural activity patterns in the brain's left temporal lobe, associated with channel T7 (refer to

Table 4), showed that five participants (datasets) experienced a cognitive load decrease. However, variations were exhibited by the other eight participants, including different combinations of increases and decreases in the activities in the theta and alpha wave bands. As already mentioned, this variation may be attributed to the specific roles of the brain region around EEG channels F7 and T7. The region around channel F7 is involved in decision-making and working memory, which are closely related to cognitive load [

67]. In contrast, channel T7 primarily involves auditory and speech processes [

62] , which may not be directly related to the neural mechanisms underlying cognitive load during programming tasks. Another reason for the inconsistency is related to the nature of the neural oscillations at specific frequency bands related to certain cognitive processes. For example, the Theta waveband (4-8 Hz) has been related to the coding phase of short-term memory tasks [

68], maintenance [

69] , information retrieval [

70], and differences in memory load [

71]. Changes in the Alpha range (8-13 Hz) with variable amplitude have been associated with attention processes and the inhibition of irrelevant information [

71,

72,

73].

4.2. Prior Knowledge and Memory Efficiency

Overall, the analyses above provide evidence that prior programming knowledge reduces the cognitive load when learners engage in programming tasks related to a new programming language and support hypothesis H1. The brain activity patterns of the participants with prior programming knowledge indicated a state of cognitive readiness and relaxed engagement, facilitating efficient retrieval of known information (prior knowledge). Given the positive impact of reduced cognitive load on memory efficiency suggested in prior research [

25,

60] it can be inferred that in this context, prior knowledge had a positive effect on memory efficiency. Furthermore, the consistent patterns of reduced theta waveband activity in participants with prior programming knowledge also support the inference; it was suggested in prior research [

68] that a reduction of neuronal activity in the theta waveband frequency reflects increased memory efficiency. Enhanced memory efficiency is likely to contribute to better learning outcomes and more effective TL as the reduced intensive cognitive processing allows learners to solve new problems without overloading their working memory

The findings of this study about the inverse relationship between the neuronal activities in theta and alpha wavebands align with results reported in the literature and in particular, in the context of completing outcome-driven tasks [

74]. In prior research, theta waveband activity was found to be associated with mental load and the encoding of new information, while the alpha waveband activity was linked to the efficient processing and retrieval of stored information [

75]. For example, it was found [

64] that increased theta activity was associated with increased task difficulty and demanding attention control requirements, while increased alpha activity reflected cognitive readiness and better attention control.

To summarize, the findings of this study provide plausible evidence supporting the study hypothesis. They demonstrate that prior knowledge positively influences memory efficiency by reducing cognitive load, as reflected by high alpha and low theta waveband activities. Low cognitive load improves memory efficiency, supporting the better retrieval of prior knowledge. This efficient memory usage facilitates an effective TL process and enhances learning performance. These findings have important implications for computer science education, particularly in addressing the challenges students face when learning programming languages. In particular, the results may motivate educators to design instructional materials that are aligned more closely with students’ cognitive capacities. Specifically, customized interventions can be developed for students with varying levels of prior knowledge, thereby improving engagement and performance. By aligning course content and teaching strategies with cognitive load requirements, educators can facilitate better learning experiences and outcomes for learning programming languages.

4.3. Comparison with Prior Work and Study Contributions

There is limited research on the use of neuronal activity patterns to study the role of prior knowledge in the TL process. Authors such as [

25] proposed a method (adapted a subjective survey instrument) to measure cognitive load in introductory computer science courses, focusing on self-reported data during lectures. However, their study did not incorporate objective neurophysiological measures, such as EEG, to assess cognitive load. In contrast, our study utilizes EEG-based measurements to objectively evaluate cognitive load, providing a more direct assessment of learners' mental effort during programming tasks.

A similar EPOC device was used in [

63] to collect experimental EEG data from participants who were working on problem-solving programming exercises. The authors computed direct measures of cognition using the alpha and theta wave frequencies and attempted to classify participants according to the level of their programming expertise. In contrast, this study identified the specific neuronal change patterns that signify cognitive load reduction or increase and, thus, more or less affect memory use.

While some researchers [

61,

76] have studied neuronal signals in relation to cognitive load, their work does not explicitly focus on how prior knowledge affects brain dynamics during learning. [

61] reviewed ML techniques for cognitive workload recognition using EEG, and [

76] proposed multimodal approaches to enhance measurement accuracy. However, these studies do not explore how cognitive load might serve as an indicator of memory efficiency within a TL study framework. Our study extends this work by identifying waveband-specific neural patterns—particularly in the alpha and theta bands—that reflect the cognitive impact of prior knowledge in programming tasks, offering a novel method to quantify TL.

[

75] identified relationships between activities in the alpha and the theta wavebands similar to the ones identified in this study. However, their study was not conducted in an educational context and did not investigate how cognitive load patterns matched task performance. In addition, the data used in the analyses were collected through a complex brain-computer interaction interface informing EEG and fMRI devices

Other related works [

60,

77] have explored cognitive absorption and cognitive load in e-learning environments, as well as predictive coding mechanisms across the left temporal and frontal brain regions during language comprehension. However, these studies do not incorporate EEG-based models related to TL and do not differentiate between learners based on prior knowledge or identify the specific brain areas involved in processing information during computer programming tasks. By focusing on EEG signals from key brain regions, namely the left frontal and temporal lobes, our study investigates how prior knowledge facilitates TL, specifically through patterns of change in alpha and theta waveband activity that reveal how the brain applies previously acquired knowledge to new programming tasks.

In summary, while prior research has advanced our understanding of cognitive load and predictive brain functions, few studies have offered a direct approach to measuring TL in the brain. This study makes several important contributions:

The study identifies neural patterns in the alpha and theta wavebands bands that demonstrate the effect of prior knowledge on cognitive load and validates their use as a framework for the evaluation of cognitive load in the context of studying a programming language.

The study proposes and validates the use of the cognitive load as an indicator of memory efficiency in the context of studying a programming language.

By integrating advanced computational models with neuroscience-based techniques, the study introduces a replicable framework for investigating the cognitive effects of prior knowledge. The novel SNN methodology for investigating TL processes using spatiotemporal neural patterns emerging from the EEG data has the potential to be generalized and used in other educational domains.

4.4. Study Limitations and Directions for Further Research

The major limitation of this study is the relatively small study sample (39 datasets based on data collected from 26 participants. Recruiting research participants was a major challenge in this study due in part to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, with some courses still conducted online. Additionally, misconceptions about the EEG device and its capabilities discouraged participation. A larger participant sample would facilitate a more precise group of participants according to their prior knowledge potentially distinguishing better between the neuronal activity patterns of the two groups.

Apart from conducting the same type of experiments on a larger dataset, future research can explore the generalizability of the methodology by applying it to the study of the processes in educational domains. The scope of the research can be expanded to developing SNN models that consider additional cognitive factors such as stress, motivation, and their impact on the neural activity patterns associated with attention, memory efficiency, and cognitive load. Enabled by the functionalities of the NeuCube platform [

47], this approach will lead to developing a more holistic understanding of how internal states and emotional responses impact learning performance and TL.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. The supplementary material ‘ScreenshotsOS.docx’ contains a document, which shows screenshots of the programming questions and the instructions to participants as presented in OpenSesame.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MHF, NK, and KP; methodology, MHF, NK, KP and GW; software, MHF; validation, MHF, KP and NK; investigation: MHF, formal analysis: MHF; resources, MHF and KP; data curation, MHF; writing—original draft preparation, MHF and KP; writing—review and editing, KP, MHF, NK and GW; visualization, MHF; supervision, KP, NK and GW; project administration, KP. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Auckland University of Technology Ethics Committee (AUTEC) under ethics application number 261/20.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Requests to access the datasets created in this study should be directed to Krassie Petrova, krassie.petrova@aut.ac.nz.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TL |

Transfer of Learning |

| TAP |

Transfer Appropriate Processing |

| CLT |

Cognitive Load Theory |

| ICL |

Intrinsic Cognitive Load |

| ECL |

Extraneous Cognitive Load |

| GCL |

Germane Cognitive Load |

| EEG |

Electroencephalogram |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| fMRI |

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| ICA |

Independent Component Analysis |

| SNNs |

Spiking Neural Networks |

| ANNs |

Artificial Neural Networks |

| STBD |

spatiotemporal brain data |

| ms |

milliseconds |

| IPK |

Insufficient Prior Knowledge |

| SPK |

Sufficient Prior Knowledge |

| TBR |

Threshold Based Representation |

| SNNc |

Spiking Neural Network cube |

| STDP |

Spike Time Dependent Plasticity |

References

- Gardner, H. The Disciplined Mind: What All Students Should Understand; 1999.

- Detterman, D.K. The case for the prosecution: Transfer as an epiphenomenon. In Transfer on trial: Intelligence, cognition, and instruction.; Ablex Publishing: Westport, CT, US, 1993; pp. 1–24.

- Mattews, P. Near and far transfer of learning. Training Journal.com. https://www.trainingjournal.com/blog/near-and-far-transfer-learning.(Accessed Sep. 20, 2020) 2018.

- Pellegrino, J.W.; Hilton, M.L. Education for life and work : developing transferable knowledge and skills in the 21st century; The National Academies Press: 2012.

- Woltz, D.J.; Gardner, M.K.; Gyll, S.P. The role of attention processes in near transfer of cognitive skills. Learning and Individual Differences 2000, 12, 209–251. [CrossRef]

- Perkins, D.N.; Salomon, G. Transfer of learning. International Encyclopedia of Education. Ed. Torsten Husten 1992, 2.

- Sala, G.; Aksayli, N.D.; Tatlidil, K.S.; Tatsumi, T.; Gondo, Y.; Gobet, F. Near and far transfer in cognitive training: A second-order meta-analysis. Collabra: Psychology 2019, 5. [CrossRef]

- Woodworth, R.S.; Thorndike, E.L. The influence of improvement in one mental function upon the efficiency of other functions.(I). Psychological Review 1901, 8, 247.

- Sala, G.; Gobet, F. Does far transfer exist? Negative evidence from chess, music, and working memory training. Current directions in psychological science 2017, 26, 515–520. [CrossRef]

- Hajian, S. The Benefits and Challenges of Analogical Comparison in Learning and Transfer: Can Self-Explanation Scaffold Analogy in the Process of Learning? SFU Educational Review 2018, 11.

- Gick, M.; Holyoak, K. Analogical problem solving. Cognitive Psychology 1980, 12, 306–355. [CrossRef]

- Spiro, R.J. Cognitive Flexibility Theory: Advanced Knowledge Acquisition in Ill-Structured Domains. Technical Report No. 441. 1988.

- Salden, R.J.; Koedinger, K.R.; Renkl, A.; Aleven, V.; McLaren, B.M. Accounting for beneficial effects of worked examples in tutored problem solving. Educational Psychology Review 2010, 22, 379–392. [CrossRef]

- Forrester, S.H. Transfer of Learning and Music Understanding: A Review of Literature. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education 2018, 37, 30–35. [CrossRef]

- Corinne, B.; Paula, A.C. Learning Transfer: The Missing Link to Learning among School Leaders in Burkina Faso and Ghana. Frontiers in Education 2018. [CrossRef]

- Siegmund, J.; Kästner, C.; Apel, S.; Parnin, C.; Bethmann, A.; Leich, T.; Saake, G.; Brechmann, A. Understanding understanding source code with functional magnetic resonance imaging. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Software Engineering, 2014; pp. 378–389.

- Crk, I.; Kluthe, T.; Stefik, A. Understanding programming expertise: an empirical study of phasic brain wave changes. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI) 2015, 23, 1–29.

- Padiri, G.R. Using EEG to Assess Programming Expertise against Self-reported Data. 2018.

- Lee, S.; Matteson, A.; Hooshyar, D.; Kim, S.; Jung, J.; Nam, G.; Lim, H. Comparing Programming Language Comprehension between Novice and Expert Programmers Using EEG Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 16th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Bioengineering (BIBE), 31 Oct.-2 Nov. 2016, 2016; pp. 350–355.

- Mulligan, N.W.; Lozito, J.P. An asymmetry between memory encoding and retrieval: Revelation, generation, and transfer-appropriate processing. Psychological Science 2006, 17, 7–11.

- Morris, C.D.; Bransford, J.D.; Franks, J.J. Levels of processing versus transfer appropriate processing. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior 1977, 16, 519–533. [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. Cognitive load theory, learning difficulty, and instructional design. Learning and Instruction 1994, 4, 295–312.

- De Jong, T. Cognitive load theory, educational research, and instructional design: some food for thought. Instructional Science 2010, 38, 105–134.

- Jordan, J.; Wagner, J.; Manthey, D.E.; Wolff, M.; Santen, S.; Cico, S.J. Optimizing lectures from a cognitive load perspective. AEM Education and Training 2020, 4, 306–312. [CrossRef]

- Morrison, B.B.; Dorn, B.; Guzdial, M. Measuring cognitive load in introductory CS: Adaptation of an instrument. In Proceedings of the 10th Annual Conference on International Computing Education Research, 2014; pp. 131–138.

- Mills, C.; Fridman, I.; Soussou, W.; Waghray, D.; Olney, A.M.; D'Mello, S.K. Put your thinking cap on: detecting cognitive load using EEG during learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the seventh international learning analytics & knowledge conference, 2017; pp. 80–89.

- Abrantes, A.; Comitz, E.; Mosaly, P.; Mazur, L. Classification of eeg features for prediction of working memory load. In Proceedings of the Advances in The Human Side of Service Engineering: Proceedings of the AHFE 2016 International Conference on The Human Side of Service Engineering, July 27-31, 2016, Walt Disney World®, Florida, USA, 2017; pp. 115–126.

- Poikonen, H.; Zaluska, T.; Wang, X.; Magno, M.; Kapur, M. Nonlinear and machine learning analyses on high-density eeg data of math experts and novices. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 8012. [CrossRef]

- Cheah, C.S. Factors contributing to the difficulties in teaching and learning of computer programming: A literature review. Contemporary Educational Technology 2020, 12, ep272. [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, T.-C.; Chuang, Y.-H.; Chen, T.-L.; Chang, C.-Y.; Chen, C.-C. Students' Performances in Computer Programming of Higher Education for Sustainable Development: The Effects of a Peer-Evaluation System. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13, 911417. [CrossRef]

- Bingöl, B. The Importance of Staying Current With Industry Trends. Sertifier Blog 2024, 2025.

- Simonsmeier, B.A.; Flaig, M.; Deiglmayr, A.; Schalk, L.; Schneider, M. Domain-specific prior knowledge and learning: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychologist 2022, 57, 31–54. [CrossRef]

- Tricot, A.; Sweller, J. Domain-specific knowledge and why teaching generic skills does not work. Educational Psychology Review 2014, 26, 265–283.

- Owens, M.T.; Tanner, K.D. Teaching as brain changing: Exploring connections between neuroscience and innovative teaching. CBE—Life Sciences Education 2017, 16, fe2. [CrossRef]

- Park, D.C.; Bischof, G.N. The aging mind: neuroplasticity in response to cognitive training. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 2013, 15, 109. [CrossRef]

- Pedro Mateos-Aparicio; Rodríguez-Moreno, A. The Impact of Studying Brain Plasticity. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2019.

- Mansvelder, H.D.; Verhoog, M.B.; Goriounova, N.A. Synaptic plasticity in human cortical circuits: cellular mechanisms of learning and memory in the human brain? 2019, 54, 186–193. [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, M.; Karwowski, W.; Farahani, F.V.; Fiok, K.; Taiar, R.; Hancock, P.A.; Al-Juaid, A. Neural decoding of EEG signals with machine learning: a systematic review. Brain Sciences 2021, 11, 1525. [CrossRef]

- Yen, C.; Lin, C.-L.; Chiang, M.-C. Exploring the frontiers of neuroimaging: a review of recent advances in understanding brain functioning and disorders. Life 2023, 13, 1472. [CrossRef]

- Douglas, P.K.; Lau, E.; Anderson, A.; Head, A.; Kerr, W.; Wollner, M.; Moyer, D.; Li, W.; Durnhofer, M.; Bramen, J. Single trial decoding of belief decision making from EEG and fMRI data using independent components features. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2013, 7, 392. [CrossRef]

- Hanslmayr, S.; Staudigl, T.; Fellner, M.-C. Oscillatory power decreases and long-term memory: the information via desynchronization hypothesis. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2012, 6, 74. [CrossRef]

- Daly, I.; Bourgaize, J.; Vernitski, A. Mathematical mindsets increase student motivation: Evidence from the EEG. Trends in Neuroscience and Education 2019, 15, 18–28.

- Friedman, N.; Fekete, T.; Gal, Y.a.K.; Shriki, O. EEG-based Prediction of Cognitive Load in Intelligence Tests. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2019, 13, 191.

- Conrad, C.D.; Bliemel, M. Psychophysiological measures of cognitive absorption and cognitive load in e-learning applications. 2016.

- Zarjam, P.; Epps, J.; Chen, F. Characterizing working memory load using EEG delta activity. In Proceedings of the 19th European Signal Processing Conference, 2011; pp. 1554–1558.

- Klimesch, W. EEG alpha and theta oscillations reflect cognitive and memory performance: a review and analysis. Brain Research Reviews 1999, 29, 169–195. [CrossRef]

- Dora, S.; Kasabov, N. Spiking neural networks for computational intelligence: an overview. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2021, 5, 67. [CrossRef]

- Ponulak, F.; Kasinski, A. Introduction to spiking neural networks: Information processing, learning and applications. Acta Neurobiologiae Experimentalis 2011, 71, 409–433.

- Kasabov, N.; Dhoble, K.; Nuntalid, N.; Indiveri, G. Dynamic evolving spiking neural networks for on-line spatio- and spectro-temporal pattern recognition. Neural Networks 2013. [CrossRef]

- Tavanaei, A.; Ghodrati, M.; Kheradpisheh, S.R.; Masquelier, T.; Maida, A. Deep learning in spiking neural networks. Neural Networks 2019, 111, 47–63. [CrossRef]

- Kasabov, N.K. NeuCube: A spiking neural network architecture for mapping, learning and understanding of spatio-temporal brain data. Neural Networks 2014, 52, 62–76. [CrossRef]

- Kasabov, N.K.; Tan, Y.; Doborjeh, M.; Tu, E.; Yang, J.; Goh, W.; Lee, J. Transfer Learning of Fuzzy Spatio-Temporal Rules in a Brain-Inspired Spiking Neural Network Architecture: A Case Study on Spatio-Temporal Brain Data. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems 2023.

- Cohen, M.X. Analyzing neural time series data : theory and practice; The MIT Press: 2014.

- OpenSesame/OpenSesame documentation. Available online: https://osdoc.cogsci.nl/ (accessed on 10 March, 2025).

- Emotiv. Emotiv Epoch X [14-channel EEG device]. Available online: https://www.emotiv.com/epoc-x/ (accessed on 23.12.2024).

- Kasabov, N.K. Time-space, spiking neural networks and brain-inspired artificial intelligence; Springer: 2019.

- Gholami, M.; Kasabov, N. Dynamic 3D Clustering of Spatio-temporal Brain Data in the NeuCube Spiking Neural Network Architecture on a Case Study of fMRI and EEG Data; Springer: 2015.

- Malenka, R.C. Bear MF 2004 LTP and LTD: an embarrassment of riches. Neuron 44, 521. [CrossRef]

- Crinion, J.T.; Lambon-Ralph, M.A.; Warburton, E.A.; Howard, D.; Wise, R.J. Temporal lobe regions engaged during normal speech comprehension. Brain 2003, 126, 1193–1201. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Schoot, L.; Brothers, T.; Alexander, E.; Warnke, L.; Kim, M.; Khan, S.; Hämäläinen, M.; Kuperberg, G.R. Predictive coding across the left fronto-temporal hierarchy during language comprehension. Cerebral Cortex 2023, 33, 4478–4497. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, S.; Xu, Z.; Wang, P.; Wu, X.; Zhang, D. Cognitive workload recognition using EEG signals and machine learning: A review. IEEE Transactions on Cognitive and Developmental Systems 2021, 14, 799–818. [CrossRef]

- Hickok, G.; Poeppel, D. The cortical organization of speech processing. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2007, 8, 393–402. [CrossRef]

- Crk, I.; Kluthe, T. Toward using alpha and theta brain waves to quantify programmer expertise. In Proceedings of the 36th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, 2014; pp. 5373–5376.

- Min, B.-K.; Park, H.-J. Task-related modulation of anterior theta and posterior alpha EEG reflects top-down preparation. BMC Neuroscience 2010, 11, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Attar, E.T. Review of electroencephalography signals approaches for mental stress assessment. Neurosciences Journal 2022, 27, 209–215.

- Van Diepen, R.M.; Foxe, J.J.; Mazaheri, A. The functional role of alpha-band activity in attentional processing: the current zeitgeist and future outlook. Current Opinion in Psychology 2019, 29, 229–238. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. Neural activity during working memory encoding, maintenance, and retrieval: A network-based model and meta-analysis. Human Brain Mapping 2019, 40, 4912–4933. [CrossRef]

- Klimesch, W.; Doppelmayr, M.; Russegger, H.; Pachinger, T. Theta band power in the human scalp EEG and the encoding of new information. Neuroreport 1996, 7, 1235–1240.

- Sarnthein, J.; Petsche, H.; Rappelsberger, P.; Shaw, G.L.; von Stein, A. Synchronization between prefrontal and posterior association cortex during human working memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1998, 95, 7092–7096. [CrossRef]

- Klimesch, W.; Doppelmayr, M.; Stadler, W.; Pöllhuber, D.; Sauseng, P.; Röhm, D. Episodic retrieval is reflected by a process specific increase in human electroencephalographic theta activity. Neuroscience Letters 2001, 302, 49–52. [CrossRef]

- Sauseng, P.; Klimesch, W.; Gruber, W.R.; Birbaumer, N. Cross-frequency phase synchronization: a brain mechanism of memory matching and attention. Neuroimage 2008, 40, 308–317. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, N.R.; Croft, R.J.; Dominey, S.J.; Burgess, A.P.; Gruzelier, J.H. Paradox lost? Exploring the role of alpha oscillations during externally vs. internally directed attention and the implications for idling and inhibition hypotheses. International Journal of Psychophysiology 2003, 47, 65–74. [CrossRef]

- Payne, L.; Guillory, S.; Sekuler, R. Attention-modulated alpha-band oscillations protect against intrusion of irrelevant information. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 2013, 25, 1463–1476. [CrossRef]

- Wendiggensen, P.; Prochnow, A.; Pscherer, C.; Münchau, A.; Frings, C.; Beste, C. Interplay between alpha and theta band activity enables management of perception-action representations for goal-directed behavior. Communications Biology 2023, 6, 494. [CrossRef]

- Borgheai, S.B.; Deligani, R.; McLinden, J.; Abtahi, M.; Ostadabbas, S.; Mankodiya, K.; Shahriari, Y. Multimodal evaluation of mental workload using a hybrid EEG-fNIRS brain-computer interface system. In Proceedings of the 2019 9th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering (NER), 2019; pp. 973–976.

- Chen, F.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y.; Yu, K.; Arshad, S.Z.; Khawaji, A.; Conway, D. Robust Multimodal Cognitive Load Measurement; Springer Publishing Company, Incorporated: 2016.

- Conrad, C.D.; Bliemel, M. Psychophysiological Measures of Cognitive Absorption and Cognitive Load in E-Learning Applications. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Interaction Sciences, 2016.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).