Submitted:

14 April 2025

Posted:

14 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Propolis Material

2.2. Animals

2.3. Preparation of Propolis Extracts

2.4. Total Phenolic Content

2.5. Total Flavonoid Content

2.6. Total Caffeic Acid Derivatives

2.7. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) Analysis of Phenolic Compounds

2.8. Antioxidant Activity

2.8.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay

2.8.2. Ferric-Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assay

2.9. Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitory Activity

2.10. Red Blood Cell Membrane Stabilization (Antihemolytic Activity)

2.10.1. Preparation of Solutions

2.10.2. Preparation of RBC Suspension

2.10.3. Experimental Procedure

2.11. Ex Vivo Anti-Inflammatory Activity

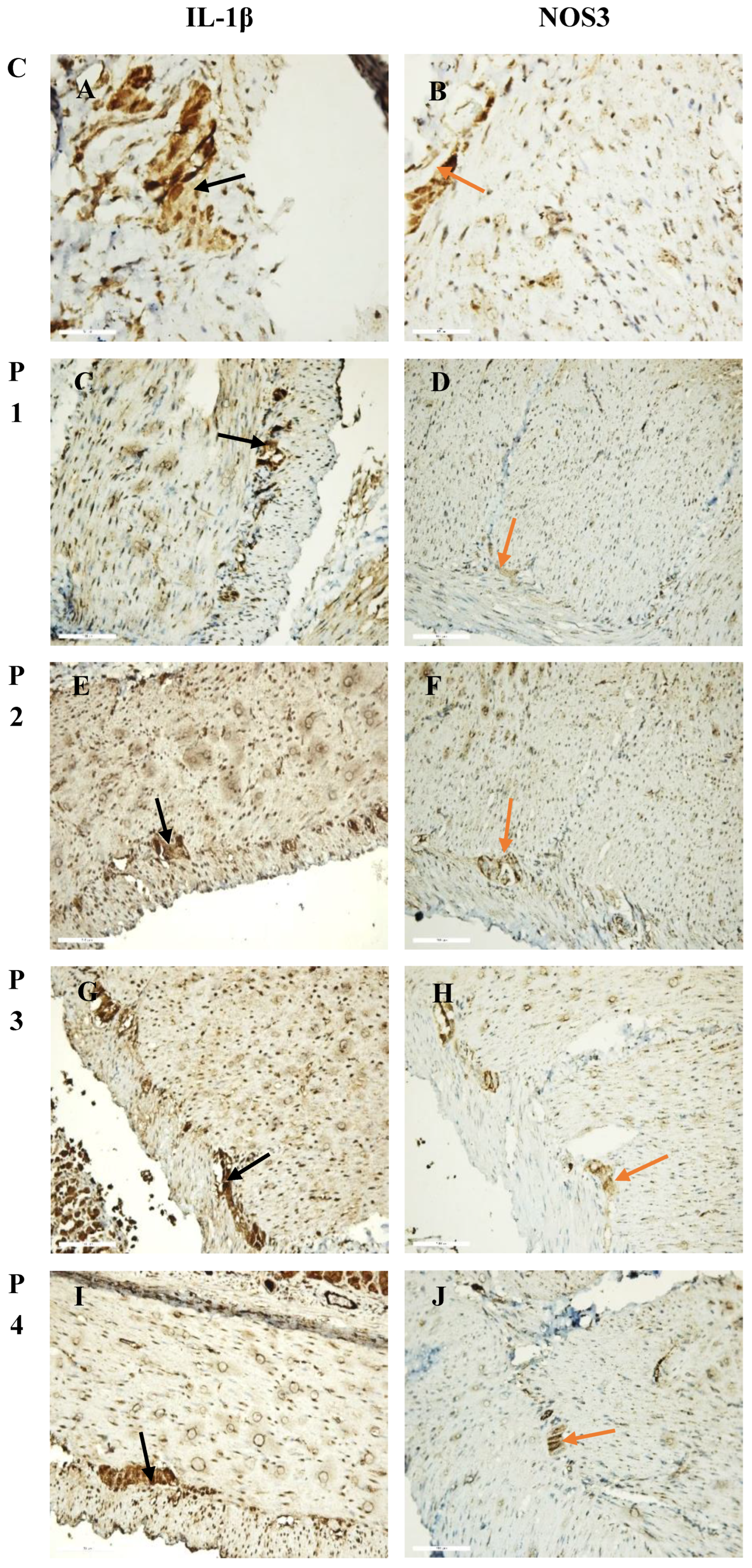

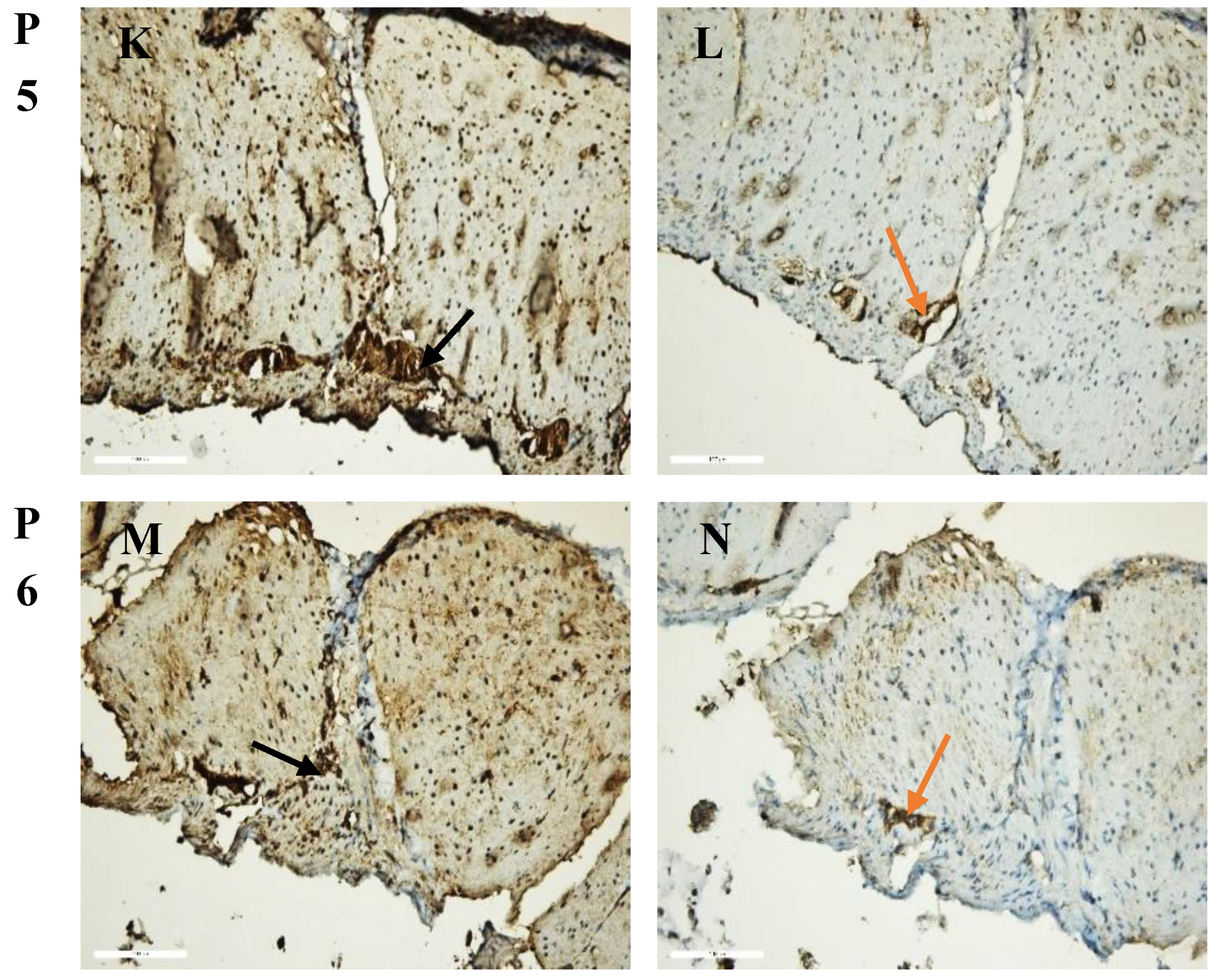

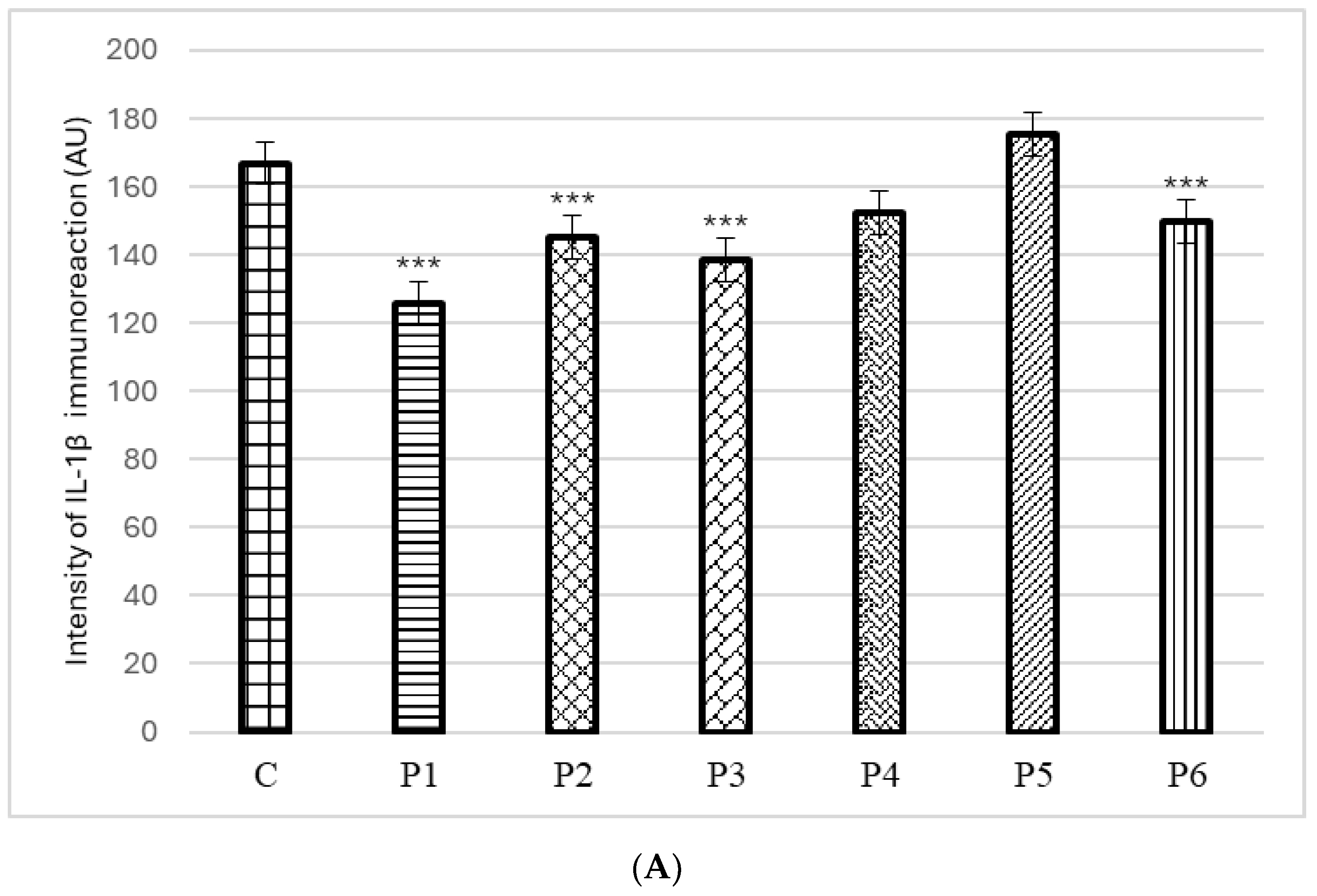

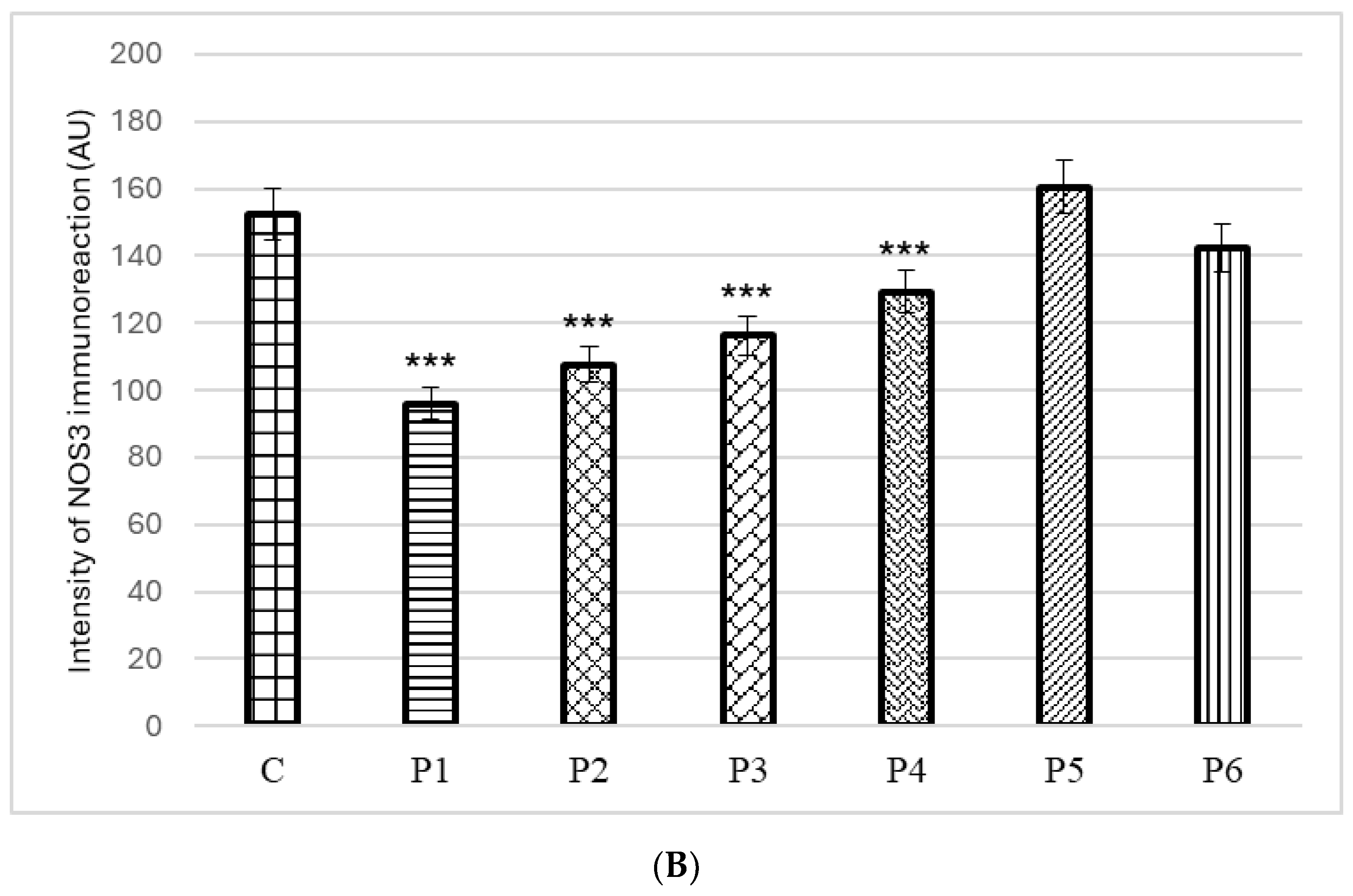

2.11.1. Immunohistochemical Analysis

2.11.2. Morphometric Analysis

2.12. Ethics Statement

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Total Phenolic Content (TPC), Total Flavonoid Content (TFC), Total Caffeic Acid Derivatives Content (TCADC), Antioxidant Activity and Phenolic Profile of DMSO Propolis Extracts

3.2. Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitory Activity

3.3. Red Blood Cell Membrane Stabilization (Antihemolytic Activity)

3.4. Ex Vivo Anti-Inflammatory Activity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Przybyłek, I.; Karpiński, T.M. Antibacterial Properties of Propolis. Molecules 2019, 24, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasote, D.; Bankova, V.; Viljoen, A.M. Propolis: chemical diversity and challenges in quality control. Phytochem. Rev. 2022, 21, 1887–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almuhayawi, M.S. Propolis as a novel antibacterial agent. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 3079–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mountford-McAuley, R.; Prior, J.; McCormick, A.C. Factors affecting propolis production. J. Apic. Res. 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, R.; Quispe, C.; Khan, R.A.; Saikat, A.S.M.; Ray, P.; Ongalbek, D.; Yeskaliyeva, B.; Jain, D.; Smeriglio, A.; Trombetta, D.; Kiani, R.; Kobarfard, F.; Mojgani, N.; Saffarian, P.; Ayatollahi, S.A.; Sarkar, C.; Islam, M.T.; Keriman, D.; Uçar, A.; Martorell, M.; Sureda, A.; Pintus, G.; Butnariu, M.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Cho, W.C. Propolis: An update on its chemistry and pharmacological applications. Chin. Med. 2022, 17, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zullkiflee, N.; Taha, H.; Usman, A. Propolis: Its Role and Efficacy in Human Health and Diseases. Molecules 2022, 27, 6120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bankova, V.; Trusheva, B.; Popova, M. Propolis extraction methods: a review. J. Apic. Res. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forma, E.; Bryś, M. Anticancer Activity of Propolis and Its Compounds. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oršolić, N.; Šaranović, A.B.; Bašić, I. Direct and Indirect Mechanism(s) of Antitumour Activity of Propolis and its Polyphenolic Compounds. Planta Med. 2006, 72, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oršolić, N.; Jembrek, M.J. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Propolis and Its Polyphenolic Compounds against Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catchpole, O.; Mitchell, K.; Bloor, S.; Davis, P.; Suddes, A. Antiproliferative activity of New Zealand propolis and phenolic compounds vs human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells. Fitoterapia 2015, 106, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendez-Encinas, M.A.; Valencia, D.; Ortega-García, J.; Carvajal-Millan, E.; Díaz-Ríos, J.C.; Mendez-Pfeiffer, P.; Soto-Bracamontes, C.M.; Garibay-Escobar, A.; Alday, E.; Velazquez, C. Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Seasonal Sonoran Propolis Extracts and Some of Their Main Constituents. Molecules 2023, 28, 4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zulhendri, F.; Lesmana, R.; Tandean, S.; Christoper, A.; Chandrasekaran, K.; Irsyam, I.; Suwantika, A.A.; Abdulah, R.; Wathoni, N. Recent Update on the Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Propolis. Molecules 2022, 27, 8473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funakoshi-Tago, M.; Okamoto, K.; Izumi, R.; Tago, K.; Yanagisawa, K.; Narukawa, Y.; Kiuchi, F.; Kasahara, T.; Tamura, H. Anti-inflammatory activity of flavonoids in Nepalese propolis is attributed to inhibition of the IL-33 signaling pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015, 25, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichitoi, M.M.; Josceanu, A.M.; Isopescu, R.D.; Isopencu, G.O.; Geana, E.-I.; Ciucure, C.T.; Lavric, V. Polyphenolics profile effects upon the antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of propolis extracts. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 20113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, M.; Freitas, A.S.; Cunha, A.; Oliveira, R.; Almeida-Aguiar, C. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of blends of propolis samples collected in different years. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 145, 111311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuntaş, Ü.; Güzel, İ.; Özçelik, B. Phenolic Constituents, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity and Clustering Analysis of Propolis Samples Based on PCA from Different Regions of Anatolia. Molecules 2023, 28, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolska, K.; Górska, A.; Antosik, K.; Ługowska, K. Immunomodulatory Effects of Propolis and its Components on Basic Immune Cell Functions. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 81, 575–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripari, N.; Sartori, A.A.; da Silva Honorio, M.; Conte, F.L.; Tasca, K.I.; Santiago, K.B.; Sforcin, J.M. Propolis antiviral and immunomodulatory activity: a review and perspectives for COVID-19 treatment. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2021, 73, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnavacca, A.; Sangiovanni, E.; Racagni, G.; Dell'Agli, M. The antiviral and immunomodulatory activities of propolis: An update and future perspectives for respiratory diseases. Med. Res. Rev. 2022, 42, 897–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Guendouz, S.; Aazza, S.; Lyoussi, B.; Antunes, M.D.; Faleiro, M.L.; Miguel, M.G. Anti-acetylcholinesterase, antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory, antityrosinase and antixanthine oxidase activities of Moroccan propolis. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 1762–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, M.G.; Doughmi, O.; Aazza, S.; Antunes, D.; Lyoussi, B. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activities of propolis from different regions of Morocco. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2014, 23, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, K.Y.; Kamise, N.I.; Ong, H.M.; Aw Yong, P.Y.; Islam, F.; Tan, J.W.; Tham, C.L. Anti-Allergic Properties of Propolis: Evidence From Preclinical and Clinical Studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 12, 785371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahinozzaman, M.; Taira, N.; Ishii, T.; Halim, M.A.; Hossain, M.A.; Tawata, S. Anti-Inflammatory, Anti-Diabetic, and Anti-Alzheimer’s Effects of Prenylated Flavonoids from Okinawa Propolis: An Investigation by Experimental and Computational Studies. Molecules 2018, 23, 2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daleprane, J.B.; da Silva Freitas, V.; Pacheco, A.; Rudnicki, M.; Faine, L.A.; Dörr, F.A.; Ikegaki, M.; Salazar, L.A.; Ong, T.P.; Abdalla, D.S.P. Anti-atherogenic and anti-angiogenic activities of polyphenols from propolis. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, M.A.R.; Libério, S.A.; Guerra, R.N.M.; Ribeiro, M.N.S.; Nascimento, F.R.F. Mechanisms of action underlying the antiinfl ammatory and immunomodulatory effects of propolis: a brief review. Braz. J. Pharmacogn. 2012, 22, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Necip, A.; Demirtas, I.; Tayhan, S.E.; Işık, M.; Bilgin, S.; Turan, İ.F.; İpek, Y.; Beydemir, Ş. Isolation of phenolic compounds from eco-friendly white bee propolis: Antioxidant, wound-healing, and anti-Alzheimer effects. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 1928–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahinozzaman, M.; Taira, N.; Ishii, T.; Halim, M.A.; Hossain, M.A.; Tawata, S. Anti-Inflammatory, Anti-Diabetic, and Anti-Alzheimer’s Effects of Prenylated Flavonoids from Okinawa Propolis: An Investigation by Experimental and Computational Studies. Molecules 2018, 23, 2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieb, J.P. Myasthenia gravis: an update for the clinician. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2014, 175, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, L.; Mantegazza, R. Treatment of Myasthenia Gravis. Clin. Drug Investig. 2011, 31, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumbarski, Y.; Ivanov, I.; Todorova, M.; Apostolova, S.; Tzoneva, R.; Nikolova, K. Phenolic Content, Antioxidant Activity and In Vitro Anti-Inflammatory and Antitumor Potential of Selected Bulgarian Propolis Samples. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, I.; Vrancheva, R.; Marchev, A.; Petkova, N.; Aneva, I.; Denev, P.; Georgiev, V.; Pavlov, A. Antioxidant Activities and Phenolic Compounds in Bulgarian Fumaria Species. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2014, 3, 296–306. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, I. Polyphenols Content and Antioxidant Activities of Taraxacum officinale F.H.Wigg (Dandelion) Leaves. Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res. 2014, 6, 889–893. [Google Scholar]

- López, S.; Bastida, J.; Viladomat, F.; Codina, C. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity of some Amaryllidaceae alkaloids and Narcissus extracts. Life Sci. 2002, 71, 2521–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, I.G.; Vrancheva, R.Z.; Petkova, N.T.; Tumbarski, Y.; Dincheva, I.N.; Badjakov, I.K. Phytochemical compounds of anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum) and antibacterial, antioxidant, and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory properties of its essential oil. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 9, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamgeer, H.U.H. Evaluation of in vitro and in vivo therapeutic efficacy of Ribes alpestre Decne in Rheumatoid arthritis. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 55, e17832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milusheva, M.; Todorova, M.; Gledacheva, V.; Stefanova, I.; Feizi-Dehnayebi, M.; Pencheva, M.; Nedialkov, P.; Tumbarski, Y.; Yanakieva, V.; Tsoneva, S.; Nikolova, S. Novel Anthranilic Acid Hybrids—An Alternative Weapon against Inflammatory Diseases. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurek-Górecka, A.; Rzepecka-Stojko, A.; Górecki, M.; Stojko, J.; Sosada, M.; Świerczek-Zięba, G. Structure and Antioxidant Activity of Polyphenols Derived from Propolis. Molecules 2014, 19, 78–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Guendouz, S.; Lyoussi, B.; Miguel, M.G. Insight on propolis from Mediterranean countries chemical composition, biological activities and application fields. Chem. Biodiversity 2019, 16, e1900094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkuş, T.N.; Değer, O. Comparison of total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities of propolis in different solvents. Food Health, 2022, 8, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdal, T.; Sari-Kaplan, G.; Mutlu-Altundag, E.; Boyacioglu, D.; Capanoglu, E. Evaluation of Turkish propolis for its chemical composition, antioxidant capacity, anti-proliferative effect on several human breast cancer cell lines and proliferative effect on fibroblasts and mouse mesenchymal stem cell line. J. Apic. Res. 2018, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmehdi, O.; Bouyahya, A.; Jekő, J.; Cziáky, Z.; Zengin, G.; Sotkó, G.; El baaboua, A.; Senhaji, N.S.; Abrini, J. Chemical analysis, antibacterial, and antioxidant activities of flavonoid-rich extracts from four Moroccan propolis. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, e15816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, M.G.; Ahmad, F.T.; Badr, A.N.; Masry, S.H.; El-Sohaimy, S.A. Chemical analysis, antioxidant, cytotoxic and antimicrobial properties of propolis from different geographic regions. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2020, 65, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi Hafshejani, S.; Lotfi, S.; Rezvannejad, E.; Mortazavi, M.; Riahi-Madvar, A. Correlation between total phenolic and flavonoid contents and biological activities of 12 ethanolic extracts of Iranian propolis. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 4308–4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orhan, I.; Kartal, M.; Tosun, F.; Şener, B. Screening of various phenolic acids and flavonoid derivatives for their anticholinesterase potential. Z. Naturforsch. C 2007, 62, 829–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltas, N.; Yildiz, O.; Kolayli, S. Inhibition properties of propolis extracts to some clinically important enzymes. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2016, 31, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hady, F.K.A.; Souleman, A.M.A.; Ibrahim, I.G.; Abdel-Aziz, M.S.; El-Shahid, Z.A.; Ali, E.A.; Elsarrag, M.S.A. Cytotoxic, Anti-acetylcholinesterase, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Sudanese Propolis with Correlation to its GC/MS and HPLC Analysis. Pharm. Lett. 2016, 8, 339–350. [Google Scholar]

- El-Hady, F.K.A.; Souleman, A.M.A.; El-Shahid, Z.A. Antiacetylcholinesterase and Cytotoxic Activities of Egyptian Propolis with Correlation to its GC/M S and HPLC Analysis. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2015, 34, 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Osés, S.M.; Marcos, P.; Azofra, P.; de Pablo, A.; Fernández-Muíño, M.Á.; Sancho, M.T. Phenolic Profile, Antioxidant Capacities and Enzymatic Inhibitory Activities of Propolis from Different Geographical Areas: Needs for Analytical Harmonization. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, P.; Sarkar, S.; Mukhophadhyay, M.J. Study the antioxidant and In vitro Anti-inflammatory activity by membrane stabilization method of Amaranthus gangeticus leaf extract. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2017, 6, 103–105. [Google Scholar]

- Humaira, A.F.; Aini, S.R.; Hasina, R. Anti –Inflammatory Activity of Propolis Trigona sp. Water Extract from North Lombok with Red Blood Cell Membrane Stability Method. Biol. Med. Natural Prod. Chem. 2024, 13, 555–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiko, A.G.; Olchowik-Grabarek, E.; Sekowski, S.; Roszkowska, A.; Lapshina, E.A.; Dobrzynska, I.; Zamaraeva, M.; Zavodnik, I.B. Antimicrobial Activity of Quercetin, Naringenin and Catechin: Flavonoids Inhibit Staphylococcus aureus-Induced Hemolysis and Modify Membranes of Bacteria and Erythrocytes. Molecules 2023, 28, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzuela-Barra, G.; Castro, C.; Figueroa, C.; Barriga, A.; Silva, X.; de las Heras, B.; Hortelano, S.; Delporte, C. Anti-inflammatory activity and phenolic profile of propolis from two locations in Región Metropolitana de Santiago, Chile. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 168, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagaoka, T.; Banksota, A.H.; Tezuka, Y.; Midorikawa, K.; Matsushige, K.; Kadota, S. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) analogues: potent nitric oxide inhibitors from The Netherlands propolis. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 26, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonska, M.; Bronikowska, J.; Pietsz, G.; Czuba, Z.P.; Scheller, S.; Krol, W. Effect of ethanol extract of propolis (EEP) and its flavones on inducible gene expression in J774A.1 macrophages. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 91, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elangovan, B. A review on pharmacological studies of natural flavanone: pinobanksin. 3 Biotech 2024, 14, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xool-Tamayo, J.; Chan-Zapata, I.; Arana-Argaez, V.E.; Villa-de la Torre, F.; Torres-Romero, J.C.; Araujo-Leon, J.A.; Aguilar-Ayala, F.J.; Rejón-Peraza, M.E.; Castro-Linares, N.C.; Vargas-Coronado, R.F.; Cauich-Rodríguez, J.V. In vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory properties of Mayan propolis. Eur. J. Inflamm. 2020, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demestre, M.; Messerli, S.M. , Celli. N.; Shahhossini, M.; Kluwe, L.; Mautner, V.; Maruta, H. CAPE (caffeic acid phenethyl ester)-based propolis extract (Bio 30) suppresses the growth of human neurofibromatosis (NF) tumor xenografts in mice. Phytother. Res. 2009, 23, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, U.A.; Phadke, A.S.; Nair, A.M.; Mungantiwar, A.A.; Dikshit, V.J.; Saraf, M.N. Membrane stabilizing activity—A possible mechanism of action for the anti-inflammatory activity of Cedrus deodara wood oil. Fitoterapia 1999, 70, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno-Silva, B.; Kawamoto, D.; Ando-Suguimoto, E.S.; Alencar, S.M.; Rosalen, P.L.; Mayer, M.P.A. Brazilian Red Propolis Attenuates Inflammatory Signaling Cascade in LPS-Activated Macrophages. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Propolis Sample* | Village | District/Region | GPS Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Gamzovo | Vidin | 44°05′ N 22°45′ E |

| P2 | Parsha | Gabrovo | 42°57′ N 25°29′ E |

| P3 | Ritya | Gabrovo | 42°59′ N 25°25′ E |

| P4 | Kozi rog | Gabrovo | 42°57′ N 25°16′ E |

| P5 | Burya | Gabrovo | 43°02′ N 25°19′ E |

| P6 | Malinovo | Lovech | 42°90′ N 24°90′ E |

| Propolis sample | TPC, mg GAE/g of extract |

TFC, mg QE/g of extract |

TCADC, mg CAE/g of extract |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 213.75 ± 0.30 | 64.41 ± 0.26 | 15.85 ± 0.69 |

| P2 | 275.09 ± 0.60 | 136.70 ± 0.13 | 18.77 ± 0.30 |

| P3 | 189.30 ± 0.10 | 95.75 ± 0.55 | 11.75 ± 0.85 |

| P4 | 290.80 ± 0.23 | 151.60 ± 0.66 | 21.79 ± 0.31 |

| P5 | 256.03 ± 0.50 | 125.24 ± 0.19 | 19.06 ± 0.27 |

| P6 | 226.01 ± 0.95 | 114.94 ± 0.52 | 15.84 ± 0.21 |

| Propolis sample | Antioxidant activity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH, mM TE/g of extract |

IC50, mg/mL of extract |

FRAP, mM TE/g of extract |

|||

| P1 | 1257.50 ± 2.12 | 0.34 ± 0.02 | 976.77 ± 2.06 | ||

| P2 | 1522.55 ± 2.24 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 1168.02 ± 2.43 | ||

| P3 | 863.73 ± 1.56 | 0.48 ± 0.03 | 796.86 ± 0.59 | ||

| P4 | 1799.22 ± 3.02 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 1145.24 ± 0.99 | ||

| P5 | 1479.69 ± 1.58 | 0.28 ± 0.01 | 1080.10 ± 0.67 | ||

| P6 | 1260.21 ± 1.42 | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 968.07 ± 1.52 | ||

| Phenolic Compounds, mg/g of Extract |

Propolis Samples | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | |

| Phenolic acids | ||||||

| Caffeic acid | 5.18 ± 0.12 | 6.60 ± 0.13 | 4.21 ± 0.04 | 6.85 ± 0.14 | 5.17 ± 0.09 | 4.98 ± 0.03 |

| p-coumaric acid | 3.00 ± 0.09 | 5.42 ± 0.11 | 2.27 ± 0.02 | 2.99 ± 0.03 | 3.54 ± 0.03 | 3.20 ± 0.04 |

| Sinapic acid | 1.47 ± 0.02 | 1.27 ± 0.05 | 3.12 ± 0.07 | 3.43 ± 0.01 | 1.76 ± 0.01 | 2.76 ± 0.07 |

| Caffeic acid benzyl ester | 4.25 ± 0.05 | 5.06 ± 0.08 | 4.71 ± 0.09 | 9.43 ± 0.15 | 7.83 ± 0.05 | 5.19 ± 0.11 |

| Cinnamic acid | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 1.96 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.00 | 0.48 ± 0.00 | 0.59 ± 0.01 | 1.25 ± 0.02 |

| Flavonoids | ||||||

| Isorhamnetin | 1.91 ± 0.07 | 3.51 ± 0.06 | 1.84 ± 0.01 | 2.85 ± 0.02 | 1.98 ± 0.04 | 2.21 ± 0.08 |

| Pinocembrin | 11.48 ± 0.15 | 36.32 ± 0.17 | 11.90 ± 0.10 | 18.61 ± 0.13 | 25.75 ± 0.26 | 22.11 ± 0.23 |

| Chrysin | 31.42 ± 0.55 | 53.98 ± 0.36 | 59.62 ± 0.44 | 81.50 ± 0.62 | 82.21 ± 0.57 | 81.90 ± 0.39 |

| Pinobanksin-3-O-propionate | 35.26 ± 0.28 | 56.85 ± 0.51 | 34.27 ± 0.18 | 75.28 ± 0.46 | 63.74 ± 0.42 | 54.28 ± 0.21 |

| Sample | Inhibition, % | IC50, mg/mL | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 mg/mL | 0.5 mg/mL | 0.25 mg/mL | 0.1 mg/mL | ||

| P1 | 40.99 ± 0.28 | 39.76 ± 0.52 | 37.64 ± 0.61 | 23.13 ± 0.83 | 1.23 ± 0.03 |

| P2 | 43.58 ± 0.44 | 41.40 ± 0.08 | 35.00 ± 0.96 | 26.73 ± 0.57 | 1.25 ± 0.02 |

| P3 | 40.12 ± 0.09 | 31.85 ± 0.82 | 24.74 ± 0.04 | 18.82 ± 0.29 | 1.39 ± 0.03 |

| P4 | 43.58 ± 0.44 | 34.57 ± 0.56 | 27.14 ± 0.18 | 18.14 ± 0.11 | 1.18 ± 0.02 |

| P5 | 46.44 ± 0.17 | 38.84 ± 0.29 | 23.93 ± 0.28 | 17.33 ± 0.04 | 1.07 ± 0.03 |

| P6 | 41.00 ± 0.07 | 35.06 ± 0.88 | 29.12 ± 0.25 | 12.75 ± 0.89 | 1.36 ± 0.24 |

| Sample | Protection, % | IC50, mg/mL | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 mg/mL | 0.25 mg/mL | 0.1 mg/mL | 0.05 mg/mL | ||

| P1 | 86.59 ± 0.39 | 72.97 ± 0.44 | 53.78 ± 0.23 | 34.03 ± 0.63 | 0.11 ± 0.01 |

| P2 | 85.29 ± 0.06 | 73.32 ± 0.23 | 48.56 ± 0.74 | 21.30 ± 0.59 | 0.14 ± 0.02 |

| P3 | 76.28 ± 0.54 | 68.53 ± 0.87 | 45.47 ± 0.55 | 39.61 ± 0.68 | 0.13 ± 0.02 |

| P4 | 86.40 ± 0.17 | 77.09 ± 0.08 | 66.69 ± 0.67 | 41.65 ± 0.89 | 0.06 ± 0.01 |

| P5 | 89.32 ± 0.20 | 78.94 ± 0.49 | 55.93 ± 0.69 | 41.71 ± 0.59 | 0.08 ± 0.01 |

| P6 | 84.28 ± 0.45 | 72.74 ± 0.84 | 64.74 ± 0.40 | 42.31 ± 0.25 | 0.06 ± 0.01 |

| Aspirin | 60.12 ± 0.36 | 55.22 ± 0.26 | 52.18 ± 0.10 | 22.68 ± 0.38 | 0.19 ± 0.02 |

| Prednisolone | 94.97 ± 0.86 | 88.26 ± 0.48 | 74.74 ± 0.69 | 35.71 ± 0.63 | 0.06 ± 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).