1. Introduction

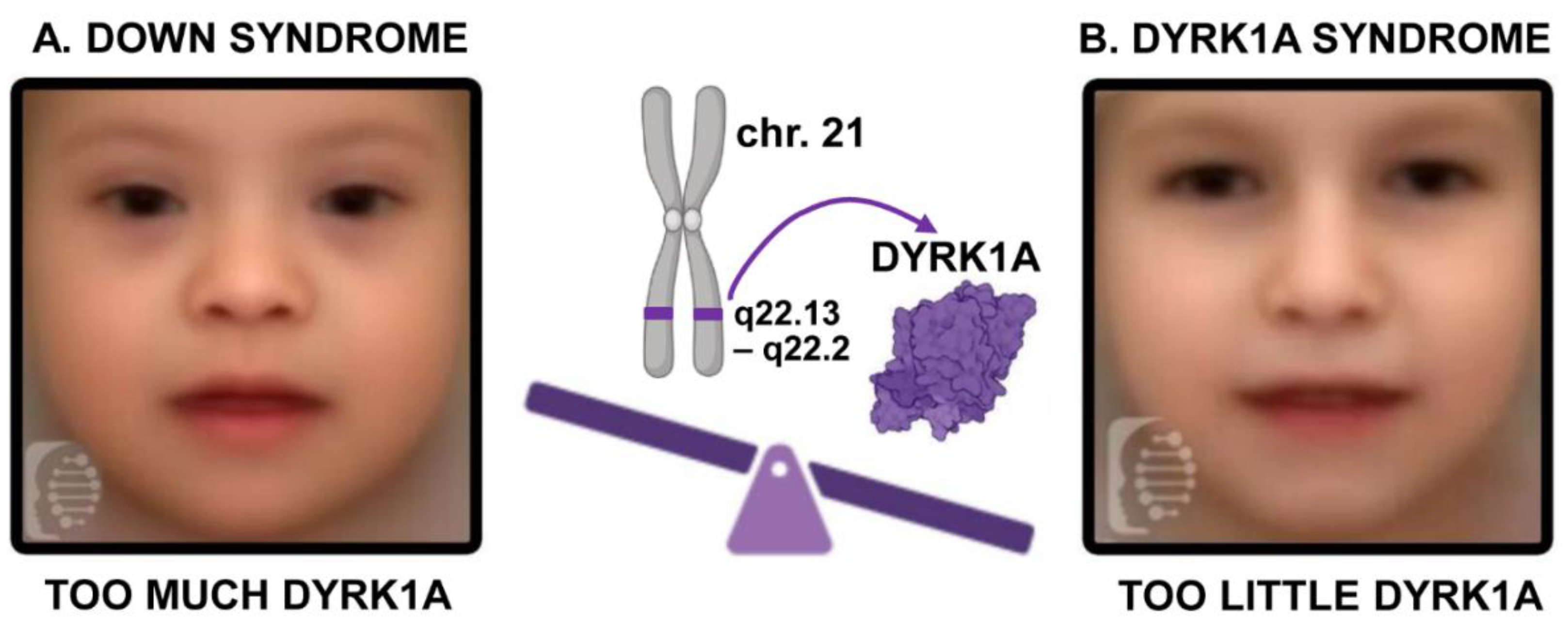

Proper concentration of regulatory proteins is vital for embryonic development, as even subtle deviations can provoke structural defects and lead to congenital anomalies. One factor that can disrupt protein levels is a change in gene dosage. In diploid organisms like humans, the typical gene dosage consists of two copies per gene, with one copy inherited from each parent. Any change in gene dosage can affect the amount of protein product, and if this results in a phenotypic change, it is termed dosage sensitivity (Rice and McLysaght, 2017a, b). For instance, a reduction in gene copies can cause haploinsufficiency, where one functional allele is insufficient for normal function (Johnson et al., 2019). Conversely, an additional gene copy may lead to triplosensitivity, where excess gene product can negatively impact development (Cooper et al., 2011). Some genes are bidirectionally dosage sensitive, meaning that both increases and decreases in gene dosage can cause phenotypic effects. One such gene is

DYRK1A (Dual-specificity Tyrosine (Y) Regulated Kinase), where too much or too little of this “Goldilocks” (see inset) protein can result in structural birth defects (Ananthapadmanabhan et al., 2023; Antonarakis et al., 2020; Atas-Ozcan et al., 2021; Duchon and Herault, 2016; Ji et al., 2015; Kaczorowska et al., 2019; Murphy et al., 2024; Widowati et al., 2018). In particular,

DYRK1A sequence variants that reduce its dosage or function are associated with

DYRK1A syndrome (aka

DYRK1A haploinsufficiency syndrome; Fig. 1)(Atas-Ozcan et al., 2021; Ji et al., 2015; Widowati et al., 2018);van Bon BWM, 2015 Dec 17 [Updated 2021 Mar 18])(Courraud et al., 2021; Obara et al., 2023). Also,

DYRK1A is located on chromosome 21 and increased dosage of this gene as a result of Trisomy 21 is thought to be an important contributor to a range of manifestations associated with Down syndrome (

Figure 1) (Becker et al., 2014; Feki and Hibaoui, 2018; Miyata and Nishida, 2023; Park et al., 2009).

|

Inset: “Goldilocks” refers to the classic fairy tale Goldilocks and the Three Bears, first modernized by Joseph Cundall in 1850. It tells the story of a young blonde girl who stumbles upon a cottage in the forest. Inside, she samples the bears’ porridge—one is too hot, one is too cold, and one is just right. She tries their chairs—one is too big, one too small, and one is just right. Finally, she tests their beds—one is too hard, one is too soft, and one is just right, where she falls asleep. The tale underscores the importance of balance.

|

The molecular nature of DYRK1A has been outlined in numerous excellent reviews (Abbassi et al., 2015; Ananthapadmanabhan et al., 2023; Becker and Sippl, 2011; Fernandez-Martinez et al., 2015; Kay et al., 2016; Murphy et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2023; Yoshida and Yoshida, 2023). DYRK1A autophosphorylates a tyrosine residue in its activation loop during translation. This autophosphorylation primes the enzyme, enabling it to subsequently phosphorylate substrates on serine/threonine residues. Once activated, DYRK1A phosphorylates a variety of substrates involved in transcription, cell cycle control, DNA repair, apoptosis and cytoskeletal dynamics. DYRK1A also has kinase activity independent functions where it may act as a scaffolding protein. The function and targets of this protein appear to be at least in part regulated by its localization. For example, in the cytosol DYRK1A has known roles in regulating cell cycle and the cytoskeleton. But also, DYRK1A contains a nuclear localization signal, and this protein functions in DNA repair and transcription that occurs in the nucleus. Consistently with such a broad range of functions and targets, mis regulation of this protein is associated with numerous human diseases including cancer, skeletal abnormalities congenital heart disease and neurodegenerative conditions (Deboever et al., 2022; Fernández-Martínez et al., 2015; Otte and Roper, 2024; Roper and Reeves, 2006; Wegiel et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2023). Moreover, it is then no wonder that DYRK1A would also be essential to the developing embryo.

In this review, we focus on the consequences of altering

DYRK1A dosage during embryonic development. We have divided the main body of this review into two parts;

Section 2) how decreased DYRK1A (too little) affects development and

Section 3) how increased DYRK1A (too much) perturbs development. We consider dosage effects separately, recognizing that the effects of increased dosage of

DYRK1A are not always just the opposite of decreasing this gene. Moreover, in this review we highlight the importance of vertebrate animal models in uncovering the mechanisms perturbed by changes in

DYRK1A dosage.

2. Too Little DYRK1A

2.1. DYRK1A Syndrome and Loss of Function Variants in Humans

DYRK1A is extremely intolerant of the loss of function copy number and sequence variants that reduce its dosage. According to the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) the probability that

DYRK1A is haploinsufficient is very high (pLI =1.0)(Kaczorowska et al., 2019). Moreover, haploinsufficiency of

DYRK1A is associated with

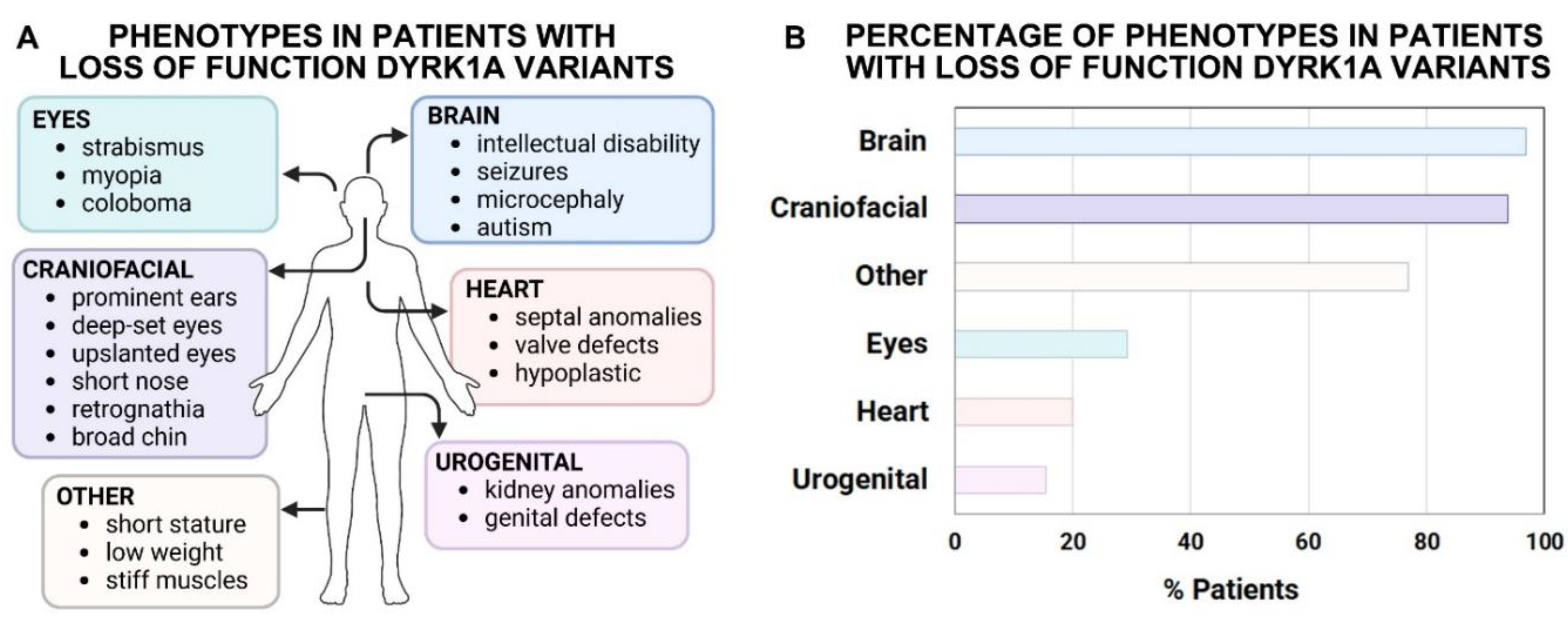

DYRK1A syndrome (Atas-Ozcan et al., 2021; Ji et al., 2015; van Bon BWM, 2015 Dec 17 [Updated 2021 Mar 18]; Widowati et al., 2018), a developmental disorder that is characterized by a number of anomalies in various organs and tissues (summarized in

Figure 2A and Suppl. File). People with

DYRK1A syndrome often have microcephaly, intellectual disability and seizures. In addition, these individuals can display characteristic facial differences as well as vision, urogenital and heart anomalies. Loss of function sequence variants of

DYRK1A have also been uncovered in children with autism (Tran et al., 2020; Tripi et al., 2019).

The types and frequencies of specific developmental anomalies in people with

DYRK1A loss of function variants could provide valuable insight into the effect of decreasing this gene. Additionally, this information could also offer knowledge about the developmental processes regulated by this gene. Therefore, we summarized publicly available data on the frequency of developmental differences in various organs and structures in the 65 people with loss of function variants reported in DECIPHER (DatabasE of genomiC varIation and Phenotype in Humans using Ensembl Resources (Firth et al., 2009), (

Figure 2B and Suppl. File). Here we assessed the phenotypes of individuals with

DYRK1A sequence variants where nucleotide changes were predicted to cause a frameshift, a new stop sequence or splicing defect. In addition, we also included in this analysis individuals with copy number variants (CNVs), where the gene was absent as part of deletion that, in the majority of cases, ranged from 1-100Mb (Suppl. File). Not surprisingly, many of the developmental differences overlapped with those reported in people with

DYRK1A Syndrome. The most prevalent developmental difference was microcephaly or small head, which is due to a smaller brain and skull size. In addition 96.9% of the individuals had conditions that stemmed from anomalies in the nervous system including intellectual disability and seizures. Also, prevalent (93.8%) were differences in the features of the face such as protruding ears, deeply set eyes, and a prominent nose. A fraction of the individuals had anomalies affecting the eye (29.2%, iris coloboma, strabismus, microphthalmia), urogenital system (15.4%, hypospadias, micropenis, renal dysplasia) and heart (20.0%, aortic valve stenosis, EEG abnormality, atrial septal defect). This information suggests that loss of one copy of

DYRK1A has profound developmental effects on multiple organs but especially the brain and craniofacial region.

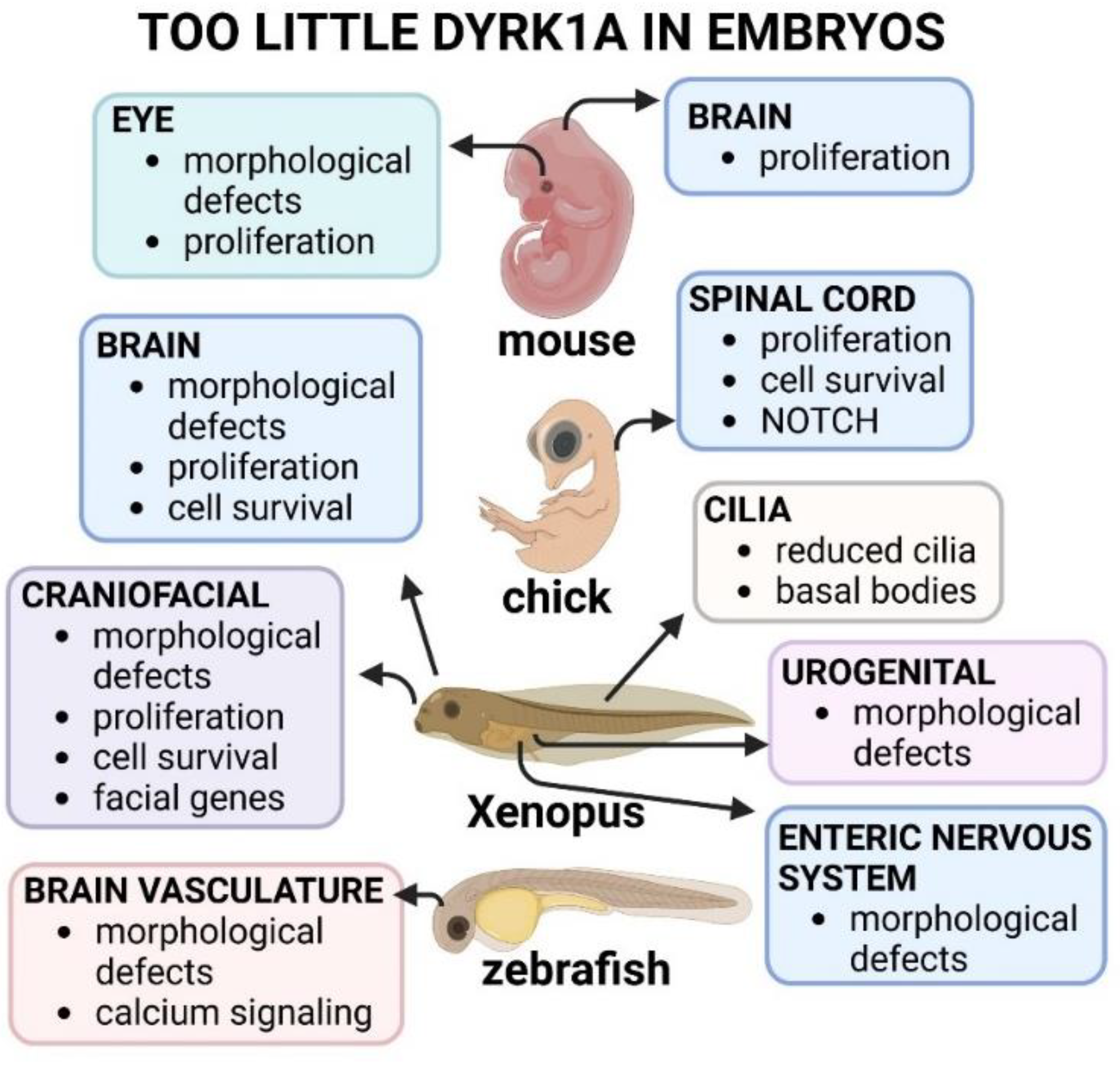

2.2. Too Little Dyrk1a Causes Developmental Anomalies in Vertebrate Animal Models

Studies in vertebrate animal models are beginning to uncover the many consequences of decreasing the dosage of

DYRK1A/

Dyrk1a/dyrk1a in the embryo. Complete loss of function or knockout of this gene is embryonic lethal in mice (Fotaki et al., 2002). These

Dyrk1a-null mutants die during early organogenesis when the brain, eyes, face and limbs are taking shape. To overcome such lethality and to better understand the effects of

DYRK1A haploinsufficiency in humans, studies in developmental animal models have focused on decreasing rather than completely depleting this gene. Such studies have indeed revealed that diminished

DYRK1A/Dyrk1a/dyrk1 affects the development of the brain, face, heart, kidney, and specific cellular structures such as cilia (summarized in

Figure 3). Importantly, these early developmental anomalies could explain some of the developmental differences in humans.

2.2.1. Too Little Dyrk1a Perturbs Central Nervous System Development

The majority of people with DYRK1A loss of function variants have intellectual disability and microcephaly. This suggests that DYRK1A protein has an important role(s) in neurodevelopment (Dierssen and de Lagrán, 2006). Indeed, the transcript and protein of this gene are expressed in the neural tube and throughout the early developing brain of mice, chick, zebrafish and Xenopus embryos (Cho et al., 2019; Fotaki et al., 2002; Hämmerle et al., 2002; Reymond et al., 2002; Willsey et al., 2020). Hammerle and colleagues (Hammerle et al., 2011) demonstrated that DYRK1A was expressed in the neuro proliferative zone of the chick spinal cord and that decreasing DYRK1A protein function in this zone resulted in increased number of mitotic cells. This was accompanied by decreased p27 (also called KIP1 and encoded by CDKN1B) a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, that regulates cell cycle exit. The authors (Hammerle et al., 2011) also found that decreasing Dyrk1a in proliferating neurons of the mouse telencephalon had the same effect. Thus, it appears that lowered DYRK1A/Dyrk1a dosage causes neurons to fail to exit the cell cycle in the developing vertebrate nervous system. In addition, it was also shown that the population of DYRK1A deficient neurons that remained undifferentiated eventually underwent apoptosis (Hammerle et al., 2011). In Xenopus embryos, Willsey and colleagues (Willsey et al., 2020) reported that reduced Dyrk1a resulted in smaller telencephalons which was accompanied by changes in the expression of cell cycle regulators such as cyclins and cyclin dependent kinases. Additionally, similar to mice and chick, there was also increased neural apoptosis that could account for the smaller brain size in the Xenopus embryos. Therefore, these studies together provide evidence that decreased Dyrk1a disrupts the cell cycle and leads to cell death in the nervous system.

The central nervous system continues to develop beyond embryonic stages and there has been a wealth of studies that have examined the effects of reduced Dyrk1a dosage on the postnatal brain and spinal cord. In many of these studies there are reports of regional specific reductions in the brain that in some cases have been correlated with behavioral changes including autistic like impairments (Barallobre et al., 2014; Exner and Willsey, 2021; Fotaki et al., 2002; Guedj et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2017; Raveau et al., 2018; Santos-Durán and Barreiro-Iglesias, 2022). From these studies, a general theme emerges where Dyrk1a is required for an appropriate balance between cell proliferation and the growth arrest during cell differentiation and its reduction can result in the death of neurons. These studies also collectively provide evidence that too little Dyrk1a affects the growth of the brain beyond embryonic development.

In addition to neurons in the brain and spinal cord, a recent study by Willsey and colleagues (McCluskey et al., 2025) demonstrates that decreased Dyrk1a could also affect the early development of the enteric nervous system which regulates the digestive system. Enteric neurons are derived from the neural crest, a group of cells in the embryo that originate next to the CNS and then migrate to the digestive tract. These neural crest cells then differentiate into the neurons controlling gut motility. The authors revealed that Dyrk1a knockdown affects the ability of the progenitor enteric neurons to properly populate the developing gastrointestinal tract in Xenopus embryos. Moreover, this correlated with a decrease in the ability of the frog larvae to digest food. This study indicates that Dyrk1a can also affect neural development outside the central nervous system.

2.2.2. Too Little Dyrk1a Causes Craniofacial Differences

The most recognizable developmental differences associated with DYRK1A syndrome are those that impact the craniofacial region. Dyrk1a/dyrk1a mRNA and encoded protein are present throughout the developing head of mice, zebrafish, and Xenopus including the branchial arches that are major contributors to the jaw (Blackburn et al., 2019; Buchberger et al., 2021; Johnson et al., 2024). It was demonstrated that diminished Dyrk1a function in Xenopus embryos caused orofacial malformations (Johnson et al., 2024). Such malformations included hypotelorism, altered mouth shape, slanted eyes, accompanied by reduction of the jaw cartilage and muscle. Remarkably, similar anomalies have been reported in people with loss of function DYRK1A variants (Suppl. File). Importantly, by employing Dyrk1a antagonists, it was revealed that facial anomalies were caused by inhibiting Dyrk1a kinase activity during a critical period of early craniofacial development. Decreased Dyrk1a function during this period led to the misexpression of key craniofacial regulators including transcription factors and members of the retinoic acid signaling pathway. These changes were also accompanied by a minor reduction in cell proliferation and dramatic increase in apoptosis in the facial tissues. Thus, as in the nervous system, too little Dyrk1a results in excess cell death which in turn contributes to the craniofacial anomalies.

2.2.3. Too Little Dyrk1a Causes Defects in the Cerebral Vasculature

In the developing zebrafish brain, dyrk1a mRNA is not only expressed in neurons but also the veins and arteries that vascularize the cerebrum. The Dyrk1a protein is highly conserved in this species, however a duplication in the genome has produced two copies of dyrk1a. Cho and colleagues (Cho et al., 2019) demonstrated that mutation of one of the copies, dyrk1aa, or treatment with a Dyrk1a inhibitor resulted in zebrafish larvae with decreased complexity of the cerebrovascular system accompanied by cerebral hemorrhaging (Cho et al., 2019). This could have been caused by enlarged interstitial spaces possibly reducing the seal between the blood vessels. In addition, the authors (Cho et al., 2019) revealed that EGTA, a calcium-specific chelator agent, was able to suppress the hemorrhagic phenotype in the dyrk1aa mutants. These results suggest that the effects of decreased Dyrk1a on brain vessels could be ameliorated by modulating calcium levels. From this work, we also might speculate that impairments in blood supply to the brain could contribute to the decreased survival of neurons, which could lead to decreased growth of the brain.

2.2.4. Too Little Dyrk1a Causes Kidney Anomalies

Congenital defects affecting the kidney are present in a subset of humans with loss of function DYRK1A variants and Dyrk1a syndrome. Consistently, Blackburn and colleagues (Blackburn et al., 2019) revealed that dyrk1a mRNA is expressed in the developing kidney and that knockdown of this protein caused kidney anomalies in Xenopus embryos. Specifically, the kidneys were missing the proximal and distal tubules that are integral for kidney function. This study also supports Xenopus as a useful translational model to study Dyrk1a-dependent kidney development since its nephron is anatomically and functionally similar to the mammalian nephron. Future work in this and other developmental models could be useful in dissecting the mechanism underlying the Dyrk1a function in the development of this organ.

2.2.6. Too Little Dyrk1a Perturbs Ciliogenesis

There are several tissues and organs, including the brain ventricles and kidney, that contain multiciliated cells. Cilia are integral to the development of multiple systems in the embryo, influencing signaling pathways such as Sonic Hedgehog as well as tissue morphogenesis and cellular communication (Amack, 2022). By sensing and transducing extracellular signals, cilia also help coordinate the growth, patterning, and organization of the vertebrate body plan (Amack, 2022; Anvarian et al., 2019; Mill et al., 2023). Therefore, it is not surprising that defects in cilia development can cause a host of malformations which are together called ciliopathies (Hildebrandt et al., 2011). The process of forming multiciliated cells has been extensively studied in the epidermis of Xenopus, where the cells are large and easily visualized (Brooks and Wallingford, 2014; Werner and Mitchell, 2012). In this model, WiIlsey and colleagues (Willsey et al., 2020) identified the presence of Dyrk1a in the cilia of epidermal multiciliated cells and demonstrated that knockdown of this protein resulted in fewer skin cilia (Willsey et al., 2020). Building upon this work, Lee and colleagues (Lee et al., 2022) revealed that Dyrk1a phosphorylates CEP97, which induces the recruitment of Polo-like kinase 1 and activation of the separase pathway. This pathway in turn is required for the formation of basal bodies, the modified centriole structures that are necessary for cilia formation and function. Thus, reduced Dyrk1a could have profound effects during the development of a range of tissues and organs by impairing cilia development.

2.2.7. Too Little Dyrk1a Alters Eye Development

Humans with loss of function DYRK1A variants often have eye malformations. Consistently, Dyrk1a mRNA and protein is expressed in the mouse retina throughout embryonic and postnatal development (Fotaki et al., 2002; Hämmerle et al., 2008; Laguna et al., 2008; Laguna et al., 2013). Laguna and colleagues (Laguna et al., 2008) demonstrated that DYRK1A has an important role in the development of this structure in mice. Specifically, Dyrk1a haploinsufficient (Dyrk1a+/−) postnatal mice have reductions in specific layers of the retina that correlates with disruptions in retinal function at the adult stage. The reduction in the number of retinal cells was not due to specific ation or proliferation of retinal progenitors in the embryo. Rather, the authors uncovered a significant increase in apoptotic cells in the affected retinal layers later in the perinatal and postnatal stages. Moreover, they also revealed that DYRK1A phosphorylated caspase-9 and thereby inhibited the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, promoting cell survival. Thus, these results reveal that too little Dyrk1a affects cell survival in the developing eye and can explain eye anomalies in people with DYRK1A loss of function variants.

3. Too Much DYRK1A

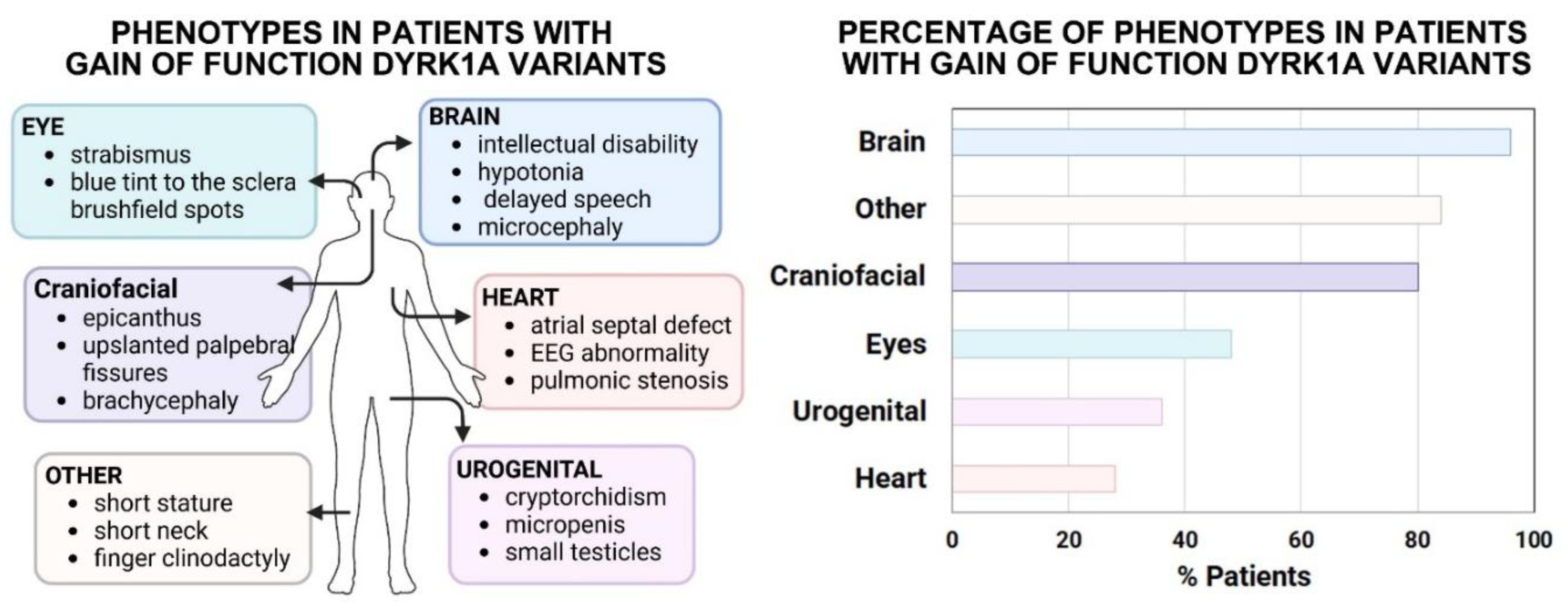

3.1. DYRK1A Gain of Function Copy Number Variants in Humans

DYRK1A is triplosensitive, meaning it is intolerant to a gain of function or duplication of an allele (pTriplo=0.98) (Collins

et al., 2022). Possibly for this reason,

DYRK1A copy number variant (CNV) gains are rare. However, we identified 25 individuals with CNVs affecting

DYRK1A and noted a wide variety of developmental anomalies in the DECIPHER database (Firth et al., 2009) (summarized in

Figure 4A,B, Suppl. File). These individuals had duplication events that, in the majority of cases, included 10-100Mbs. Of the individuals with

DYRK1A gains, 96.0% had differences affecting the brain or motor function such as intellectual disability, hypotonia as well as delayed speech and language development. A large proportion of people (80.0%) also had anomalies affecting the craniofacial region including a skin fold in the upper eyelid (epicanthus), upslanted palpebral fissures, and malformed skull shape (brachycephaly). Structural differences affecting the eye (strabismus, blue tint to the sclera, brushfield spots) were also very frequent occurring in 48.0% of individuals with CNVs affecting

DYRK1A. A smaller proportion (28.0%) of people also had defects affecting the heart (including atrial septal defect, EEG abnormality, pulmonic stenosis), as well as the urogenital system (36.0% and 3.2% respectively). There were also a proportion of individuals with

DYRK1A CNV gains that had other anomalies that did not fall into these categories, affecting other aspects of the body. For example, many people had short stature, had a short neck with extra skin, crooked fingers (clinodactyly) and small hands. This information suggests that increased DYRK1A could have profound developmental effects on multiple organs, structures and tissue types.

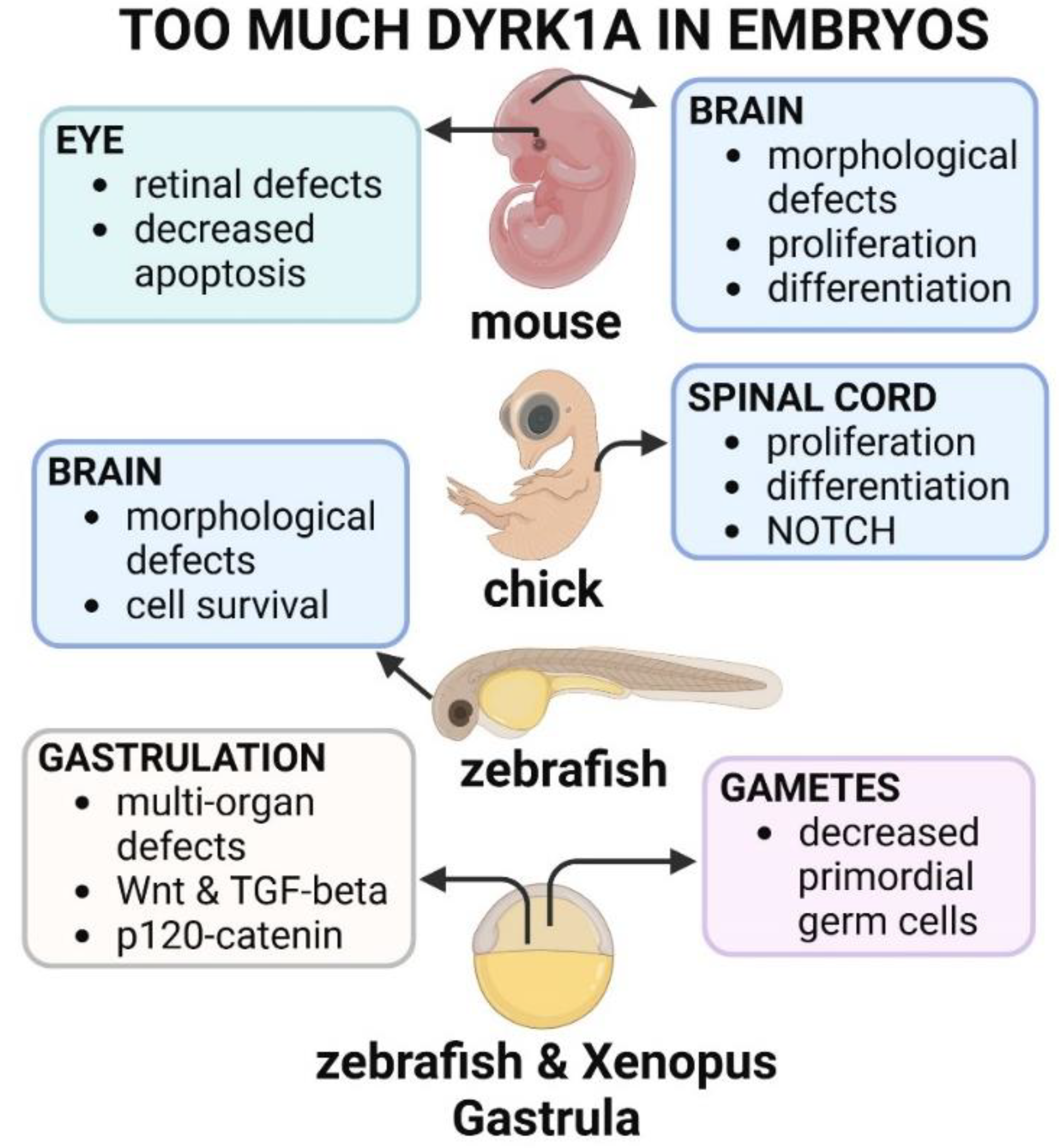

3.2. Too Much Dyrk1a in Vertebrate Animal Models Causes Developmental Defects

People with

DYRK1A gain of function variants can present with anomalies affecting multiple organs and tissues. Animal models have revealed that such anomalies could be due to specific and sometimes the different effects of excess DYRK1A/Dyrk1a on each organ system as well as more global effects on early developmental processes (summarized in

Figure 5).

3.2.1. Too Much Dyrk1a Disrupts Gastrulation

As the embryo begins to arrange its germ layers during gastrulation, a specialized region called the organizer forms. This region emits signals that induce surrounding cells to adopt specific fates and guide the development of various tissues and organs (Kumar et al., 2021). The organizer also plays a crucial role in establishing the anterior-posterior and dorsal-ventral axes of the embryo (Bouwmeester, 2001; De Robertis, 2009). Liu and colleagues (Liu et al., 2022) showed that when dyrk1a was overexpressed in zebrafish embryos, the genes expressed in the organizer were downregulated. Later, these embryos had anomalies such as axis defects and malformations affecting the brain, craniofacial structures, eyes and heart. The authors (Liu et al., 2022) also revealed that organizer disruption was due to Dyrk1a’s effects on two important signaling pathways, WNT and TGF-beta, both of which are critical for germ layer formation and patterning the embryo’s axes (Carron and Shi, 2016; Hikasa and Sokol, 2013; Kofron et al., 1999). In Xenopus, Hong and colleagues (Hong et al., 2012) also revealed that excess Dyrk1a caused gastrulation delays accompanied by the misexpression of the organizer genes. Moreover, these authors also demonstrated that too much Dyrk1a could enhance axis duplication caused by ectopic beta-catenin expression. This finding suggests that this protein could modulate canonical WNT signaling at these early stages. Indeed, the authors uncovered a role for Dyrk1a in regulating p120-catenin and Kaiso, which together repress canonical WNT signaling (Hong et al., 2012). Moreover, an excess of Kaiso rescued the effect of dyrk1a overexpression on gastrulation and target gene expression.

These studies in aquatic developmental models suggest that too much Dyrk1a can perturb early signals, including WNT, that are critical for gastrulation. By altering this developmental process, we could predict that excess dyrk1a would cause multi-organ defects. These studies emphasize the importance of determining how changes in DYRK1A/Dyrk1a/dyrk1a dosage affect early developmental stages and processes.

3.2.2. Too Much Dyrk1a Disrupts Central Nervous System Development

Overexpression of DYRK1A/Dyrk1a /dyrk1a has been shown to affect the growth of the brain in several model vertebrates. For example, in the same study that examined effects of decreased DYRK1A in the developing chick nervous system, Hammerle and colleagues (Hammerle et al., 2011) also investigated the effect of increasing this protein. They determined that ectopic expression of DYRK1A has the opposite effect of decreasing this gene and induced a decrease in mitotic cells in a neuro proliferative zone. In another study, Yabut and colleagues (Yabut et al., 2010) electroporated Dyrk1a into the cerebral cortex of embryonic stages of mice and found that it affects the balance between proliferation and differentiation of neurons. Specifically, excess Dyrk1a inhibits neural cell proliferation and promotes premature neuronal differentiation in the radial glial cells, the neural stem cells of the brain. Moreover, they demonstrated that these effects are dependent on the DYRK1A kinase activity and are mediated by the nuclear export and degradation of cyclin D1 (Yabut et al., 2010). In zebrafish larva, Buchberger and colleagues (Buchberger et al., 2021) tested the effects of dyrk1a overexpression in Purkinje cells, a specific population of neurons located in the cerebellum that governs motor control. Results demonstrated that overexpression in these cells did not interfere with their initial survival (Buchberger et al., 2021). However, later in development the Purkinje cell layers occupied a smaller area within the cerebellum but without a reduction in cell numbers, suggesting that differentiation and cell morphology could be perturbed. This morphological change in the cerebellum significantly correlated with alterations in swimming behavior. Moreover, the Purkinje cell layer defects could be prevented by Dyrk1a inhibition.

Together, these studies in the embryonic stages of animal models suggest that Dyrk1a is important in different populations of developing neurons at different times. Mechanistically, it appears to be essential in modulating the balance between proliferation and differentiation. Interestingly, Hammerle and colleagues (Hammerle et al., 2011), identified NOTCH signaling as regulator of such a balance in chick embryos. Indeed, this pathway is well established as being important for regulating the switch between proliferation and differentiation in the developing nervous system (Moore and Alexandre, 2020; Roese-Koerner et al., 2017).

Too much Dyrk1a not only affects the brain during embryonic stages, but also during postnatal stages as the central nervous system matures. For example, several studies have shown that transgenic mice with an extra copy of the mouse or human Dyrk1/DYRK1A had increased brain weight and region-specific morphological changes postnatally (Ahn et al., 2006; Altafaj et al., 2001; Branchi et al., 2004; Guedj et al., 2012; Sebrié et al., 2008). Guedj and colleagues (Guedj et al., 2012) also showed that too much Dyrk1a dramatically enhanced AKT signaling in the postnatal brain, a pathway intimately tied to cell proliferation and growth (Mahajan and Mahajan, 2012; Peng et al., 2003).

Together, studies of excess Dyrk1a in the nervous system suggest that it can cause an imbalance in proliferation and differentiation in multiple neural cell types and at various times during development. This imbalance could explain the morphological differences in the brain as well as behaviors deficits in animal models and humans with too much Dyrk1a/DYRK1A.

3.2.3. Too Much Dyrk1a Disrupts Germ Cell Development

Individuals with DYRK1A gain of function CNVs have increased risk of urogenital differences and infertility. Lui and colleagues (Liu et al., 2017) demonstrated that some of these differences could be caused by defective development of the primary germ cells in zebrafish embryos. These germ cells are specified very early in development and then migrate to the gonad position after which they develop into eggs and sperm (De Felici, 2000; Raz, 2003). Overexpression of either the human or zebrafish dyrk1a in embryos resulted in fewer and disordered primordial germ cells. Moreover, proteomic analysis revealed that these changes were accompanied by the decrease of two proteins (Ca15b and Piwil1) important for primordial germ cell development. Consistently, Dard and colleagues (Dard et al., 2021) revealed that postnatal mice overexpressing Dyrk1a have impaired fertility and deficiencies in spermatogenesis. In this model, at these later stages, the spermatogonia are produced in excess, but accompanied by abnormal spermatogonial differentiation and meiosis entry.

Together, the studies of gamete development in mice and zebrafish suggest the possibility that excess DYRK1A has more than one effect on gamete production, but a common thread emerges that similar to the nervous system, too much DYRK1A/Dyrk1a may be dysregulating the balance between the proliferating and differentiating gametes.

3.2.4. Too Much Dyrk1a Causes Eye Malformations

Structural and functional differences in the eye are present in individuals with gain of function CNVs of DYRK1A. Consistently, Laguna et al (2013) determined that specific layers of the retina are thicker in adult mice with an extra copy of Dyrk1a (mBACtgDyrk1a). These morphological changes correlated with enhanced retinal activity and altered responses to light. Moreover, the authors determined that such changes in the adult retina could be due to a decrease in caspase-9 mediated apoptosis during embryonic stages. Cell death is a critical process in vertebrate retinal development, refining the numbers of cells and neuronal connections (Biehlmaier et al., 2001; Farah and Easter, 2005). Thus, both too little (section 2.2.7) and too much DYRK1A deregulates cell survival in the retinal, altering the morphology and the function of the eyes.

3.3. Down Syndrome

Gain of function of DYRK1A also occurs in Down syndrome, one of the most universally recognized genetic syndromes which has been well described in many reviews (Antonarakis, 2017; Antonarakis et al., 2004; Antonarakis et al., 2020; Asim et al., 2015; Bull, 2020; Kaczorowska et al., 2019; Rafii et al., 2019; Roper and Reeves, 2006; Wiseman et al., 2009). Down syndrome is caused by an extra copy of chromosome 21, which contains at least 233 protein-coding genes as well as 423 non-protein-coding genes and 188 pseudogenes (Antonarakis et al., 2020). Thus, most certainly, the multi-organ presentation of Down Syndrome is not caused by the overexpression of one individual gene such as DYRK1A but by a range of consequential interactions of other genes on chromosome 21 and their targets (Sloan et al., 2023). However, as discussed in section 3.4 below correcting Dyrk1a dosage in Down syndrome mouse models demonstrates that indeed DYRK1A could be an important contributor to the developmental anomalies in this common congenital syndrome. Therefore, understanding the effects of excess DYRK1A could lead to insight into the developmental mechanisms that can cause some of the phenotypic differences associated with Down Syndrome.

Down Syndrome is characterized by intellectual disability, decreased muscle tone, seizures, as well a set of stereotypical features (Antonarakis, 2017; Locatelli et al., 2022; Murphy et al., 2024) (Suppl. File). These include craniofacial differences such as a flat or depressed nasal bridge, upward slant of the eyes, epicanthus, protruding tongue and brachycephaly. In addition, people with Down syndrome can also have eye anomalies, congenital heart defects, and specific differences in the hands. Interestingly, many of the structural abnormalities observed in Down syndrome individuals are also reported in people with DYRK1A CNV gains (see Suppl. file), in further support of the conclusion that this gene could contribute to the birth defects associated with Down syndrome. However, this type of comparison needs to be made with caution since each phenotypic difference can be caused by perturbing different processes and genes in the embryo. That is, the same phenotypic anomaly could be caused by very different mechanisms. Therefore, it is important to understand the specific developmental effects of excess DYRK1A to determine if this gene contributes to the phenotypes associated with Down syndrome.

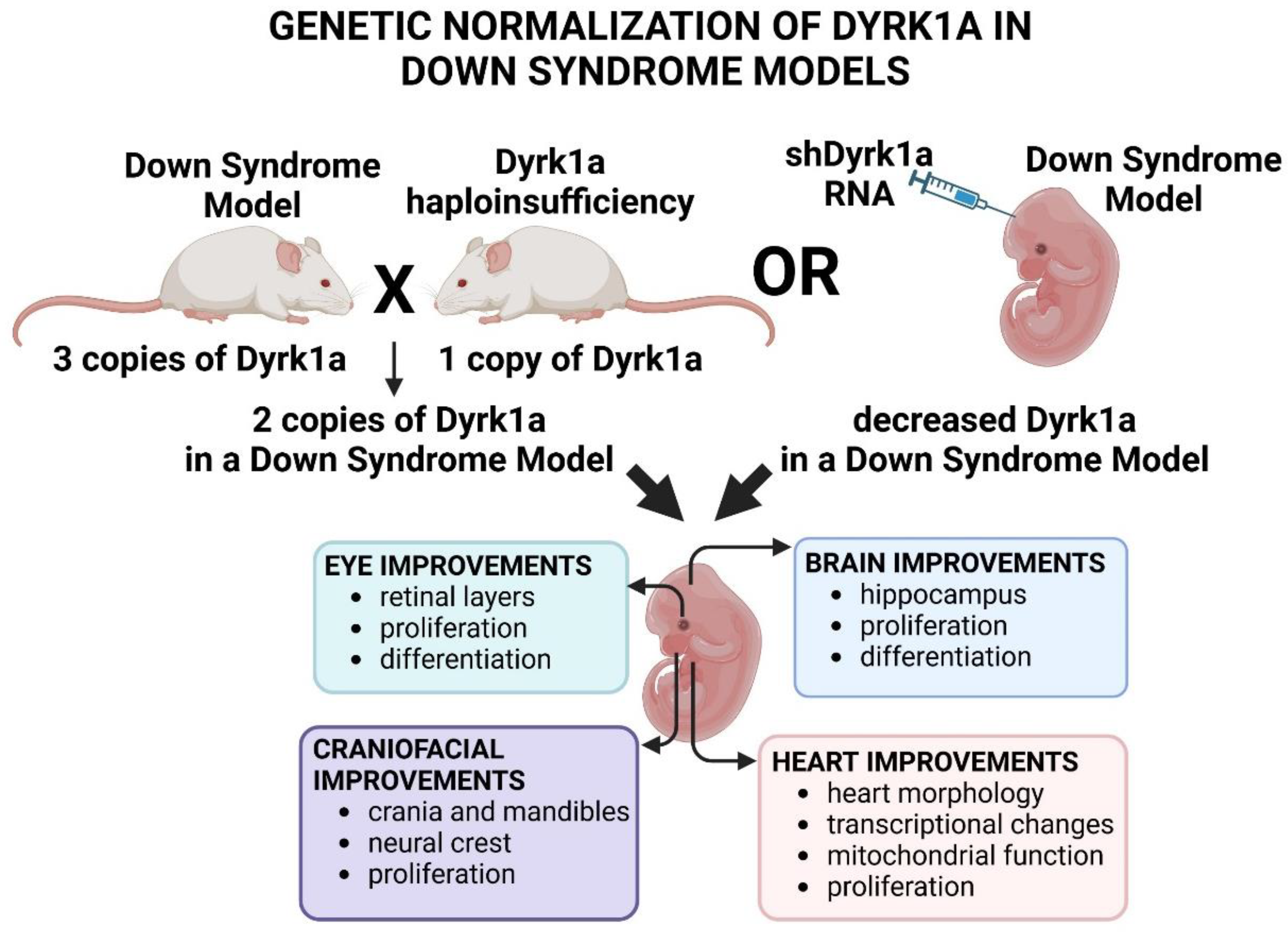

3.4. Normalizing DYRK1A Dosage in Animal Models of Down Syndrome

To test whether DYRK1A contributes to specific developmental differences in Down syndrome, strategies to genetically or pharmacologically normalize Dyrk1a primarily in mouse Down syndrome models have been utilized (Atas-Ozcan et al., 2021; Herault et al., 2017; Moore and Roper, 2007). Investigators have used these types of experiments to demonstrate that elevated Dyrk1a could contribute to the brain, heart, and craniofacial malformations in the Down syndrome animal models.

3.4.1. Genetically Normalizing Dyrk1a Can Improve Developmental Anomalies in Down Syndrome Mouse Models

One method to assess the influence of too much

Dyrk1a in Down syndrome mouse models is to genetically normalize the amount of this protein. To accomplish this, investigators have crossed one of the mouse models of Down Syndrome (such as Ts65Dn or Dp1Tyb) with

Dyrk1a haploinsufficient mice (

Dyrk1a+/−). This then results in mice with a normalized copy number of

Dyrk1a (Ts65Dn or Dp1Tyb/

Dyrk1a +/+/−) with a Down syndrome-like background. This allows investigators to dissect the specific effects of too much

Dyrk1a in the context of the trisomy of other genes gained in Down syndrome. However, some caution should be considered since

Dyrk1a levels are not always normalized consistently using this approach (Hawley et al., 2024). Another method to genetically normalize

Dyrk1a is to use short hairpin RNA, which can be injected into specific tissue in the Down syndrome mouse model. This method allows for a more targeted approach to understand the role of DYRK1A at a specific time and place in the context of Down syndrome. Collectively, these types of studies indicate that normalizing

Dyrk1a dosage can improve Down syndrome associated malformations in the eye, face, brain and heart (summarized in

Figure 6)

3.4.1.1. Brain Development

Since one of the most prevalent and devastating anomalies associated with Down syndrome is intellectual disability, there has been a significant effort to assess the effect of normalizing Dyrk1a in the brain of mice. A growing body of evidence demonstrates that indeed normalization of Dyrk1a during embryonic development in the trisomic mouse models can result in improvements nervous system that can be later assessed in postnatal stages (Feki and Hibaoui, 2018; García-Cerro et al., 2014; Jiang et al., 2015; Ortiz-Abalia et al., 2008; Stringer et al., 2017b). For example, Garcia-Cerro and colleagues (García-Cerro et al., 2014) crossed Dyrk1a haploinsufficient mice (Dyrk1a+/−) with a Down syndrome model (Ts65Dn) and showed that proliferation, differentiation and synapse markers were returned to normal in the hippocampus. Moreover, these morphological changes correlated with improvements in behavioral tests that assessed memory and fear. Using a different approach, Altafaj and coworkers (Altafaj et al., 2013) normalized Dyrk1a by injecting a short hairpin RNA against Dyrk1a into the Ts65Dn mouse embryo. In doing so, synaptic plasticity molecular markers and the electrophysiological properties of the hippocampus were also returned to normal.

Together, these studies reveal that DYRK1A overexpression in individuals with Down syndrome could be responsible for some of the associated structural and functional brain anomalies. Moreover, similar to studies assessing excess Dyrk1a alone, normalizing this gene can improve proliferation and differentiation and at least partially rescue the neural function in animal models of Down Syndrome.

3.4.1.2. Craniofacial Development

People with Down syndrome have a set of characteristic craniofacial differences, and they are at a greater risk for cleft lip/palate (Allareddy et al., 2016; Antonarakis, 2017; Farkas et al., 2001; Macho et al., 2014; Rafii et al., 2019; Vicente et al., 2020). Down syndrome mouse models also have numerous differences in the shape and morphology of the jaw and skull bones that can be recognized in embryonic stages (McElyea et al., 2016; Redhead et al., 2023). To assess the potential effects of too much Dyrk1a on these skeletal elements, Redhead and colleagues (Redhead et al., 2023) crossed Dyrk1a+/− mice with a mouse Down Syndrome model (Dp1Tyb). Indeed, they determined that when Dyrk1a was normalized in these mice, the shape and size of the crania and mandibles were closer to normal. One possible explanation for the cranial skeletal defects in Down syndrome could be the differences in cranial neural crest development since this population of cells contributes to much of the vertebrate cranial skeleton (Knight and Schilling, 2006; Santagati and Rijli, 2003). Indeed, in mouse models of Down syndrome there is a decrease in neural crest correlating with a reduction in mitotic cells in this population of cells (Redhead et al., 2023; Roper et al., 2009). This neural crest proliferation defect was eliminated when Dyrk1a was normalized in the Dp1Tyb mice (Redhead et al., 2023). These studies indicate that excess DYRK1A could be a contributor to some of the craniofacial defects associated with Down syndrome, particularly those caused by neural crest proliferation deficits.

3.4.1.3. Heart Development

Heart anomalies, including septal defects and malformations of the outflow tract, are prevalent in newborn Down syndrome individuals and can lead to increased mortality (Vis et al., 2009). Similarly, septal and outflow tract defects are also observed in mouse models of Down Syndrome (Lana-Elola et al., 2016). Lana-Elola and colleagues (Lana-Elola et al., 2024) revealed that such morphological anomalies in both humans and mice are accompanied by altered expression of genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation and cellular proliferation. Consistently, in the mouse Down syndrome model there was impaired mitochondrial function and cell proliferation in the embryonic hearts. The authors then crossed the Dyrk1a+/- heterozygous mice with a Down Syndrome model (Dp1Tyb) to test whether the increased Dyrk1a contributed to heart anomalies and changes in cardiomyocyte transcriptional profiles in this mouse. Remarkably, the embryonic hearts of the Dyrk1a normalized embryos did not have the characteristic septal defects seen in the Dp1Tyb mice and appeared more like the wild type controls. In addition, the transcriptional profiles, proliferation rates and mitochondrial function in embryonic cardiomyocytes were more similar to controls when Dyrk1a was normalized. These results indicate that elevated Dyrk1a in Down syndrome indeed contributes to specific changes in early heart development.

3.4.1.4. Eye Development

Down Syndrome individuals and mouse models often have visual impairments, including retinal defects. Such defects include bigger eyes with thinker retinal cell layers and these morphological abnormalities correlate with abnormal visual function (Laguna et al., 2008; Laguna et al., 2013). Laguna and colleagues (Laguna et al., 2008; Laguna et al., 2013) determined that normalizing Dyrk1a in two different Down syndrome mouse models (tgYAC152f7-B and Ts65Dn) ameliorated such retinal defects. The tgYAC152f7-B model has extra copies of four genes (Pigp, Ttc3, Dscr3 and Dyrk1a) that are on chromosome 21 of humans. When haploinsufficient Dyrk1a+/−mice were crossed with these tgYAC152f7-B mice, it was found that the offspring had retina morphologies that were indistinguishable from those of wild-type control Dyrk1a (Dyrk1a+/+) mice (Laguna et al., 2008). In a separate study, Laguna and colleagues (2013) also revealed the same effect of normalizing Dyrk1a in the Ts65Dn mice which have triplication of many more genes. Importantly, in this latter study the authors also demonstrated that the levels caspase-9 positive cells were reduced in the Dyrk1a+/+/- mice. Such results are consistent with increased caspase-9 in the retinas of mice haploinsufficient for Dyrk1a (see section 2.2.7 above), together indicating that DYRK1A is responsible for regulating cell survival. In summary, these imbalances in Dyrk1a, causes changes in cell survival which in turn results in retinal malformations in the Down syndrome model mice (Laguna et al., 2008).

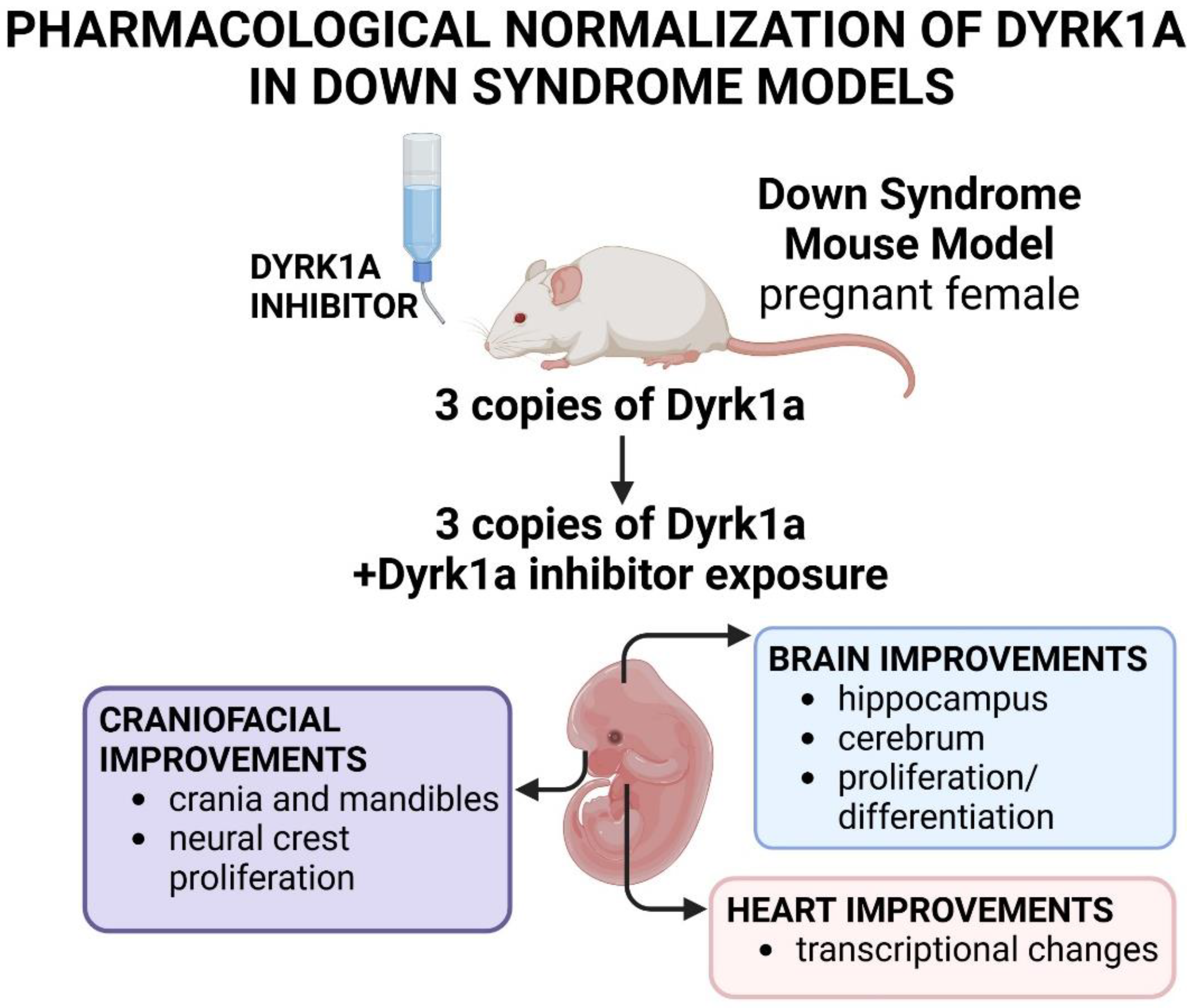

3.4.2. Normalizing Dyrk1a Pharmacologically Can Improve Developmental Anomalies in Down Syndrome Mouse Models

Another method to normalize Dyrk1a in Down syndrome animal models is to treat them with chemicals that can inhibit the protein (Stringer et al., 2017b). There has been a number of compounds that have been shown to inhibit Dyrk1a/DYRK1A kinase activity including Harmine, Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), INDY, ALGERNON and Leucettines (Adayev et al., 2011; Bain et al., 2003; Becker and Sippl, 2011; Naert et al., 2015; Nguyen et al., 2018; Ogawa et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2023). In particular, EGCG is an antioxidant compound found in green tea that has been the most widely tested chemical for its therapeutic potential in correcting the deficits associated with Down syndrome. Moreover, EGCG is currently being clinically tested in Down syndrome (identifier #s; NCT01394796, NCT01699711, NCT03624556, accessed 10/25/24, clinicaltrials.gov). The other benefit of treating mouse models with small molecule Dyrk1a/DYRK1A inhibitors is that they can be applied over specific windows of time, when

Dyrk1a may be differentially expressed. However, the caveat is that there are off-target and side effects associated with some of these chemicals (see (Jamal et al., 2022; Stringer et al., 2017b)). Furthermore, the role of Dyrk1a/DYRK1A in all tissues at every time of development is not fully understood (Ananthapadmanabhan et al., 2023). In most studies, the proof of mechanism that the chemical’s rescue effect was indeed due to normalizing Dyrk1a activity, was not tested. Despite these caveats, pharmacological approaches to normalizing Dyrk1a through its protein function, have shown promise in ameliorating at least some neural, craniofacial and heart malformations in Down Syndrome mouse models (summarized in

Figure 7).

3.4.2.1. Brain Development

DYRK1A inhibitors have shown promise in correcting the neural and behavioral anomalies present in mouse models of Down syndrome and have been the subject of several excellent reviews (Atas-Ozcan et al., 2021; Becker et al., 2014; de la Torre and Dierssen, 2012; Duchon and Herault, 2016; Feki and Hibaoui, 2018). Here we will highlight two studies focused on neural development after treatments over embryonic periods.

Souchet and colleagues (Souchet et al., 2019) determined that prenatal treatment of a mouse model (Dp(16)1Yey) with green tea extract (containing EGCG and other compounds) corrected neural anomalies affecting the hippocampus. The hippocampus is a key brain area involved in object recognition memory. Encoding new memories depends on the balance between the inhibitory GABAergic interneurons and the excitatory glutaminergic neurons in the hippocampus. The Dp(16)1Yey mice have an abnormal balance in these excitatory and inhibitory neurons that later correlates with a decreased ability to recognize objects (Souchet et al., 2019). Green tea extract administered to pregnant mice during the gestation was able to restore the inhibitory/excitatory balance as well as memory recognition in the Down syndrome model (Souchet et al., 2019). In a similar study, Nakano-Kobayashi and coworkers (Nakano-Kobayashi et al., 2017) demonstrated that in utero treatment with a DYRK1A ATP competitive inhibitor, ALGERNON, could also rescue brain anomalies in a Down Syndrome mouse model (Ts1Cje). In this model, ALGERNON administered to pregnant Ts1Cje mice improved the number of proliferating and differentiating neurons in the hippocampus of the offspring. In addition, they also determined that this treatment improved the anomalies in cortical regions of the cerebrum that contain migrating and differentiating neurons. Finally, ALGERNON-treated embryos later showed improved performance in behavioral tests that assessed exploration, memory and learning.

Together these studies demonstrate that in different mouse models of Down syndrome, in different regions of the brain and using different inhibitors, DYRK1A normalization can improve neurodevelopment. Furthermore, restoration of early brain development later correlates with improved brain function. Therefore, these studies suggest that targeting DYRK1A could be a promising method to ameliorate the cognitive deficiencies associated with Down syndrome.

3.4.2.2. Craniofacial Development

Down syndrome mouse models have been shown to have altered facial skeletal dimensions (McElyea et al., 2016; Redhead et al., 2023; Starbuck et al., 2021). Starbuck and coworkers (Starbuck et al., 2021) revealed that green tea extract containing EGCG normalized some aspects of craniofacial development in a Down syndrome mouse model (Ts65Dn). The treatment occurred over early embryonic (prior to the differentiation of the facial skeleton) to postnatal stages followed by an assessment of craniofacial skeletal morphology. 60% of the Ts65Dn mice treated with green tea extract had skeletal dimensions that were more similar to the untreated control mice. These results indicated that the treatment could rescue facial dysmorphology in a subset of animals. Interestingly, a higher dose of green tea extract did not improve skeletal shape and may in fact have worsened the facial anomalies in the Ts65Dn mice (also see (Stringer et al., 2017a)). The authors extended their analysis to a small study in humans where children with Down Syndrome were given green tea extract from 0-3 years of age. Remarkably, six of the seven children with Down Syndrome that were given green tea extract had less severe facial phenotypes compared to untreated children. In particular, green tea supplementation was associated with changes in various dimensions of the nose, philtrum, and midface. These same craniofacial improvements were not noted in children that were given green tea extract at older ages. These results in mice and humans show the possibility that DYRK1A inhibition could be an effective method to ameliorate some craniofacial anomalies associated with Down syndrome, especially when provided during early stages of development.

In another pre-clinical mouse study, McElyea and collegues (McElyea et al., 2016) targeted EGCG treatments to a smaller window of craniofacial development. In this study, the authors focused on early pharyngeal arch development when Dyrk1a is highly expressed in a Down syndrome mouse model (Ts65Dn). In the Ts65Dn mice, the first pharyngeal arch was smaller in size and had fewer neural crest cells during early craniofacial development (Roper et al., 2009). EGCG, given to Ts65Dn pregnant mothers over embryonic days 7 and 8, improved the size of the first pharyngeal arch, increased the number of neural crest cells and enhanced neural crest migration and proliferation in the offspring. Furthermore, this treatment also normalized the expression of several genes important for craniofacial development including two sonic hedgehog signaling members, a pathway important for pharyngeal arch and craniofacial development (Abramyan, 2019; Haworth et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2023). Moreover, this pathway has specifically been shown to be misregulated in the pharyngeal arches in a Down syndrome mouse model (Roper et al., 2009). Importantly, this study indicates that there is potential in targeting such treatments to important early developmental windows when Dyrk1a regulates specific tissues and/or is mis-expressed in Down syndrome (McElyea et al., 2016). Moreover, these studies also help to probe the specific effects and signaling pathways disrupted by excess Dyrk1a in Down syndrome.

Together, these studies in both mice and humans demonstrate that DYRK1A inhibition during embryonic development can ameliorate craniofacial anomalies associated with Down syndrome. Moreover, they highlight the importance of further research using tractable animal models to establish the developmental window for safe and efficient application of the DYRK1A inhibitors for ameliorating the Down syndrome associated craniofacial anomalies.

3.4.2.3. Heart Development

Heart defects are common in Down syndrome and genetic normalization of Dyrk1a in mouse models of this disease improved heart development (see section 3.4.1.3 (Lana-Elola et al., 2024)). Therefore, to extend their analysis, Lana-Elola and colleagues (Lana-Elola et al., 2024) also tested whether a DYRK1A antagonist, Leucettinib-21, could also improve heart development in the mouse Down Syndrome model (Dp1Tyb). When the pregnant mice were provided with Leucettinib-21 over a time when the offspring’s heart was developing, there was a partial rescue. That is, this chemical reversed the changes in the differentially expressed genes involved in proliferation and oxidative stress in the Dp1Tyb embryonic hearts. On the other hand, this treatment did not significantly improve the structural malformations of the heart. These results indicate that Leucettinib-21 treatment was not as effective as genetically normalizing DYRK1A function with respect to heart development. However, there may have been a partial effect that could be optimized by altering treatment duration, mode of administration or type of DYRK1A inhibitor.

4. Conclusions and Future Directions

Altered dosage of DYRK1A has profound effects during development. It is no wonder that there is considerable effort being made to understand the function of this protein and develop methods to correct its levels in DYRK1A haploinsufficiency and Down Syndrome. Certainly, correcting Dyrk1a dosage specifically in Down syndrome animal models shows promise in alleviating craniofacial, eye, heart and neural anomalies associated with this disease. However, while there is promise that DYRK1A inhibitors could offer therapeutic options for people, these compounds have had little or no success in some preclinical mouse experiments and in other cases have even caused harm (Goodlett et al., 2020; Hawley et al., 2024; Jamal et al., 2022; Stringer et al., 2017a). These variable results emphasize that dosage and timing of Dyrk1a inhibition are important to consider. Also, it has to be considered that DYRK1A is a potential tumor suppressor and has a role in the adult brain physiology (Abbassi et al., 2015; Fernandez-Martinez et al., 2015; Wegiel et al., 2011). Therefore, modulating this protein could have unwanted effects with respect to other diseases. Finally, it may also be important to consider that altering Dyrk1a dosage could have variable effects in different tissues and in different sexes (Hawley et al., 2024).

As an alternative to a broad unfettered inhibition of DYRK1A, we could instead modulate this protein by blocking interacting or regulatory proteins. Like other kinases, DYRK1A/Dyrk1a forms complexes with scaffolding and adaptor proteins (Ananthapadmanabhan et al., 2023). Emerging evidence also indicates that such complexes can modulate DYRK1A catalytic activity or localization and thereby its function (Miyata and Nishida, 2023). A better understanding of DYRK1A-interacting proteins and substrates could offer strategies for more precise modulation of the DYRK1A function to avoid unwanted systemic side effects (Ananthapadmanabhan et al., 2023). However, more work is needed. Further questions that can be answered using efficient animal models include 1) when and where DYRK1A regulators are expressed, 2) the mechanisms by which these interactors contribute to DYRK1A function, and 3) whether these interactors have other DYRK1A-unrelated roles in the embryo.

Another method to modify the effects of abnormal DYRK1A dosage could be to modulate downstream cellular processes. Some basic themes have emerged with respect to the processes regulated by Dyrk1a/DYRK1A during embryonic development. That is, this protein appears to have a critical role in balancing cell proliferation, differentiation and survival. Modulating these processes rather than DYRK1A itself could be an alternative way to treat DYRK1A and Down syndromes. This idea has also shown some promise. For example, blocking cell death reduced the effects of Dyrk1a haploinsufficiency during eye development in mice (Laguna et al., 2008). However, these are essential processes and therefore it will be important to utilize methods to provide precise control both temporally and spatially.

Abnormal levels of DYRK1A could also be offset by modulating downstream transcriptional targets or signaling pathways. In embryos, Dyrk1a has been shown to modulate pathways such as sonic hedgehog, Notch, WNT, Hippo and calcium signaling. This avenue also shows promise since altering some of these pathways (sonic hedgehog, beta-catenin, and calcium) has each been shown to correct some of the developmental defects caused by incorrect dosage of Dyrk1a or anomalies in Down syndrome (Cho et al., 2019; Hong et al., 2012; Roper et al., 2009). However, such pathways are utilized in many developmental processes and therefore careful targeting will need to be developed before these types of experiments can move past the pre-clinical phase. To aid this avenue, future work could focus on the specific cells and timing of the downstream targets that are activated by DYRK1A during normal development and under disease conditions. This emphasizes the need for more studies using single-cell and spatial transcriptomics as well as high resolution co-localization of DYRK1A/Dyrk1a protein and various signaling intermediates in the embryo. Along these lines, single cell sequencing has revealed important insights into the transcriptional changes in specific cell types in Down syndrome mouse models (Chen et al., 2023). For example, Chen et al. revealed that in the early embryo there was a down regulation in genes that are critical for the cell identity of neurons, mesenchymal cells, hepatocytes and immune cells. Moreover, the authors propose that this defect in differentiation and cell identity could be connected to the activation of senescence which has also been observed in neural progenitors of the Down syndrome brain (Meharena et al., 2022). It would be interesting to know whether such effects were mediated in part by DYRK1A, especially since this protein can promote quiescent/senescent cell states (Litovchick et al., 2011).

We are still at the early research stages of understanding the full complement of developmental processes and tissues affected by altering DYRK1A/Dyrk1a/dyrk1a dosage. For example, in addition to neural, craniofacial, heart and urogenital differences we know that people with DYRK1A or Down syndrome also have bone anomalies which may lead to differences in height and bone strength (Otte and Roper, 2024; Zhang et al., 2022). Certainly, increased DYRK1A expression can impair the proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts in culture and in postnatal mice (Lee et al., 2009). In Down syndrome mouse models Dyrk1a dosage plays a role in the appendicular skeletal abnormalities and this role is sex specific (LaCombe et al., 2024; Sloan et al., 2023). However, in a study where Dyrk1a was normalized in a Down syndrome mouse model there was no improvement to skeletal abnormalities during embryogenesis. Additional studies in the embryo, especially in the context of decreased Dyrk1a, are necessary to better define how levels of this protein affect the development of bone as well as other tissues.

In conclusion, animal models have been critical in revealing that alterations in Dyrk1a dosage during embryonic development affect the formation of multiple tissues and organs. Emerging from these studies is the knowledge that disruption in the dosage of DYRK1A can lead to anomalies in growth, differentiation and cell survival. A more thorough understanding of these effects can lead to important insights into DYRK1A syndrome and Down syndrome as well as developing preventions and treatment for these birth defects.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Excel file showing phenotypes in individuals with Dyrk1a Syndrome, Down Syndrome, and with sequence and copy number variants of Dyrk1A in sheet one. Note that this is not an exhaustive list but presents commonly reported phenotypes. In addition, on sheet two are screen shots displaying the genetic overview of DYRK1A variants from DECIPHER (Firth et al., 2009).

Author Contributions

Johnson: editing, DECIPHER analysis; Litovchick: editing and funding acquisition; Dickinson: conception, primary writer and compiler of information, funding acquisition.

Funding

This worked was supported in part by R01DE023553 (NIDCR) to AD, R21HD105144 (NICHD) to LL and AD, VCU Children’s Hospital Research Institute internal award to LL and AD, and the VCU Postbaccalaureate Research Education Program (R25GM089614) that provided funds to support KJ.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the VCU Children’s Hospital Research Institute for supporting this work and stimulating collaboration. Figure 1 was made possible by the work done by FDNA (

https://fdna.com) which creates composite facial images from hundreds of individuals with birth defects and syndromes. We would especially like to thank the scientists who created, tested and published the work it took to generate these images which serve as a tremendous asset to the research community (Gurovich et al., 2019). This study makes use of data generated by the DECIPHER community. A full list of centres who contributed to the generation of the data is available from

https://deciphergenomics.org/about/stats and via email from contact@deciphergenomics.org. DECIPHER is hosted by EMBL-EBI and funding for the DECIPHER project was provided by the Wellcome Trust [grant number WT223718/Z/21/Z] (Firth et al., 2009). We used BioRender to generate images in figures 2-7. The concise nature and focus on embryonic development have meant that important work on DYRK1A, DYRK1A syndrome and Down syndrome may not be covered here. Any omissions are not intended to diminish the significance of research on these topics.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- Abbassi, R.; Johns, T.G.; Kassiou, M.; Munoz, L. DYRK1A in neurodegeneration and cancer: Molecular basis and clinical implications. Pharmacol Ther, 2015, 151, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramyan, J. Hedgehog Signaling and Embryonic Craniofacial Disorders. J Dev Biol 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adayev, T.; Wegiel, J.; Hwang, Y.W. Harmine is an ATP-competitive inhibitor for dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1A (Dyrk1A). Arch Biochem Biophys, 2011, 507, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, K.J.; Jeong, H.K.; Choi, H.S.; Ryoo, S.R.; Kim, Y.J.; Goo, J.S.; Choi, S.Y.; Han, J.S.; Ha, I.; Song, W.J. DYRK1A BAC transgenic mice show altered synaptic plasticity with learning and memory defects. Neurobiol Dis, 2006, 22, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allareddy, V.; Ching, N.; Macklin, E.A.; Voelz, L.; Weintraub, G.; Davidson, E.; Prock, L.A.; Rosen, D.; Brunn, R.; Skotko, B.G. Craniofacial features as assessed by lateral cephalometric measurements in children with Down syndrome. Progress in orthodontics, 2016, 17, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altafaj, X.; Dierssen, M.; Baamonde, C.; Martí, E.; Visa, J.; Guimerà, J.; Oset, M.; González, J.R.; Flórez, J.; Fillat, C.; Estivill, X. Neurodevelopmental delay, motor abnormalities and cognitive deficits in transgenic mice overexpressing Dyrk1A (minibrain), a murine model of Down's syndrome. Human molecular genetics, 2001, 10, 1915–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altafaj, X.; Martín, E.D.; Ortiz-Abalia, J.; Valderrama, A.; Lao-Peregrín, C.; Dierssen, M.; Fillat, C. Normalization of Dyrk1A expression by AAV2/1-shDyrk1A attenuates hippocampal-dependent defects in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome. Neurobiol Dis, 2013, 52, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amack, J.D. Structures and functions of cilia during vertebrate embryo development. Mol Reprod Dev, 2022, 89, 579–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananthapadmanabhan, V.; Shows, K.H.; Dickinson, A.J.; Litovchick, L. Insights from the protein interaction Universe of the multifunctional "Goldilocks" kinase DYRK1A. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2023, 11, 1277537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonarakis, S.E. Down syndrome and the complexity of genome dosage imbalance. Nature reviews. Genetics, 2017, 18, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonarakis, S.E.; Lyle, R.; Dermitzakis, E.T.; Reymond, A.; Deutsch, S. Chromosome 21 and down syndrome: From genomics to pathophysiology. Nature reviews. Genetics, 2004, 5, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonarakis, S.E.; Skotko, B.G.; Rafii, M.S.; Strydom, A.; Pape, S.E.; Bianchi, D.W.; Sherman, S.L.; Reeves, R.H. Down syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2020, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anvarian, Z.; Mykytyn, K.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Pedersen, L.B.; Christensen, S.T. Cellular signalling by primary cilia in development, organ function and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol, 2019, 15, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asim, A.; Kumar, A.; Muthuswamy, S.; Jain, S.; Agarwal, S. "Down syndrome: An insight of the disease". Journal of biomedical science, 2015, 22, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atas-Ozcan, H.; Brault, V.; Duchon, A.; Herault, Y. Dyrk1a from Gene Function in Development and Physiology to Dosage Correction across Life Span in Down Syndrome. Genes (Basel) 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, J.; McLauchlan, H.; Elliott, M.; Cohen, P. The specificities of protein kinase inhibitors: An update. The Biochemical journal, 2003, 371, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barallobre, M.J.; Perier, C.; Bové, J.; Laguna, A.; Delabar, J.M.; Vila, M.; Arbonés, M.L. DYRK1A promotes dopaminergic neuron survival in the developing brain and in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Cell Death Dis, 2014, 5, e1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, W.; Sippl, W. Activation, regulation, and inhibition of DYRK1A. FEBS J, 2011, 278, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, W.; Soppa, U.; Tejedor, F.J. DYRK1A: A potential drug target for multiple Down syndrome neuropathologies. CNS & neurological disorders drug targets, 2014, 13, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Biehlmaier, O.; Neuhauss, S.C.; Kohler, K. Onset and time course of apoptosis in the developing zebrafish retina. Cell Tissue Res, 2001, 306, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, A.T.M.; Bekheirnia, N.; Uma, V.C.; Corkins, M.E.; Xu, Y.; Rosenfeld, J.A.; Bainbridge, M.N.; Yang, Y.; Liu, P.; Madan-Khetarpal, S.; Delgado, M.R.; Hudgins, L.; Krantz, I.; Rodriguez-Buritica, D.; Wheeler, P.G.; Al-Gazali, L.; Mohamed Saeed Mohamed Al Shamsi, A.; Gomez-Ospina, N.; Chao, H.T.; Mirzaa, G.M.; Scheuerle, A.E.; Kukolich, M.K.; Scaglia, F.; Eng, C.; Willsey, H.R.; Braun, M.C.; Lamb, D.J.; Miller, R.K.; Bekheirnia, M.R. DYRK1A-related intellectual disability: A syndrome associated with congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. Genet Med, 2019, 21, 2755–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouwmeester, T. The Spemann-Mangold organizer: The control of fate specification and morphogenetic rearrangements during gastrulation in Xenopus. Int J Dev Biol, 2001, 45, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branchi, I.; Bichler, Z.; Minghetti, L.; Delabar, J.M.; Malchiodi-Albedi, F.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Chettouh, Z.; Nicolini, A.; Chabert, C.; Smith, D.J.; Rubin, E.M.; Migliore-Samour, D.; Alleva, E. Transgenic mouse in vivo library of human Down syndrome critical region 1: Association between DYRK1A overexpression, brain development abnormalities, and cell cycle protein alteration. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol, 2004, 63, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, E.R.; Wallingford, J.B. Multiciliated cells. Curr Biol, 2014, 24, R973–R982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchberger, A.; Schepergerdes, L.; Flaßhoff, M.; Kunick, C.; Köster, R.W. A novel inhibitor rescues cerebellar defects in a zebrafish model of Down syndrome-associated kinase Dyrk1A overexpression. The Journal of biological chemistry 2021, 297, 100853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, M.J. Down Syndrome. N Engl J Med, 2020, 382, 2344–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carron, C.; Shi, D.L. Specification of anteroposterior axis by combinatorial signaling during Xenopus development. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol, 2016, 5, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, F.; Gao, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Sun, H.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, S.; Chen, K.; Sun, Y.; Tu, M.; Li, J.; Luo, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Huang, Y.; Sun, X.; Guo, G.; Zhang, D. Single-cell landscape analysis reveals systematic senescence in mammalian Down syndrome. Clin Transl Med, 2023, 13, e1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.J.; Lee, J.G.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Huh, Y.H.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, K.S.; Yu, K.; Lee, J.S. Vascular defects of DYRK1A knockouts are ameliorated by modulating calcium signaling in zebrafish. Dis Model Mech 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, G.M.; Coe, B.P.; Girirajan, S.; Rosenfeld, J.A.; Vu, T.H.; Baker, C.; Williams, C.; Stalker, H.; Hamid, R.; Hannig, V.; Abdel-Hamid, H.; Bader, P.; McCracken, E.; Niyazov, D.; Leppig, K.; Thiese, H.; Hummel, M.; Alexander, N.; Gorski, J.; Kussmann, J.; Shashi, V.; Johnson, K.; Rehder, C.; Ballif, B.C.; Shaffer, L.G.; Eichler, E.E. A copy number variation morbidity map of developmental delay. Nature genetics, 2011, 43, 838–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courraud, J.; Chater-Diehl, E.; Durand, B.; Vincent, M.; Del Mar Muniz Moreno, M.; Boujelbene, I.; Drouot, N.; Genschik, L.; Schaefer, E.; Nizon, M.; Gerard, B.; Abramowicz, M.; Cogné, B.; Bronicki, L.; Burglen, L.; Barth, M.; Charles, P.; Colin, E.; Coubes, C.; David, A.; Delobel, B.; Demurger, F.; Passemard, S.; Denommé, A.S.; Faivre, L.; Feger, C.; Fradin, M.; Francannet, C.; Genevieve, D.; Goldenberg, A.; Guerrot, A.M.; Isidor, B.; Johannesen, K.M.; Keren, B.; Kibæk, M.; Kuentz, P.; Mathieu-Dramard, M.; Demeer, B.; Metreau, J.; Steensbjerre Møller, R.; Moutton, S.; Pasquier, L.; Pilekær Sørensen, K.; Perrin, L.; Renaud, M.; Saugier, P.; Rio, M.; Svane, J.; Thevenon, J.; Tran Mau Them, F.; Tronhjem, C.E.; Vitobello, A.; Layet, V.; Auvin, S.; Khachnaoui, K.; Birling, M.C.; Drunat, S.; Bayat, A.; Dubourg, C.; El Chehadeh, S.; Fagerberg, C.; Mignot, C.; Guipponi, M.; Bienvenu, T.; Herault, Y.; Thompson, J.; Willems, M.; Mandel, J.L.; Weksberg, R.; Piton, A. Integrative approach to interpret DYRK1A variants, leading to a frequent neurodevelopmental disorder. Genet Med, 2021, 23, 2150–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dard, R.; Moreau, M.; Parizot, E.; Ghieh, F.; Brehier, L.; Kassis, N.; Serazin, V.; Lamaziere, A.; Racine, C.; di Clemente, N.; Vialard, F.; Janel, N. DYRK1A Overexpression in Mice Downregulates the Gonadotropic Axis and Disturbs Early Stages of Spermatogenesis. Genes (Basel) 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Felici, M. Regulation of primordial germ cell development in the mouse. Int J Dev Biol, 2000, 44, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de la Torre, R.; Dierssen, M. Therapeutic approaches in the improvement of cognitive performance in Down syndrome: Past, present, and future. Prog Brain Res, 2012, 197, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Robertis, E.M. Spemann's organizer and the self-regulation of embryonic fields. Mech Dev, 2009, 126, 925–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deboever, E.; Fistrovich, A.; Hulme, C.; Dunckley, T. The Omnipresence of DYRK1A in Human Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierssen, M.; de Lagrán, M.M. DYRK1A (dual-specificity tyrosine-phosphorylated and -regulated kinase 1A): A gene with dosage effect during development and neurogenesis. ScientificWorldJournal, 2006, 6, 1911–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchon, A.; Herault, Y. DYRK1A, a Dosage-Sensitive Gene Involved in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, Is a Target for Drug Development in Down Syndrome. Front Behav Neurosci, 2016, 10, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exner, C.R.T.; Willsey, H.R. Xenopus leads the way: Frogs as a pioneering model to understand the human brain. Genesis, 2021, 59, e23405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, M.H.; Easter, S.S. ; Jr. Cell birth and death in the mouse retinal ganglion cell layer. J Comp Neurol, 2005, 489, 120–134. [Google Scholar]

- Farkas, L.G.; Katic, M.J.; Forrest, C.R. Surface anatomy of the face in Down's syndrome: Anthropometric proportion indices in the craniofacial regions. J Craniofac Surg, 2001, 12, 519–524, discussion 525–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feki, A.; Hibaoui, Y. DYRK1A Protein, A Promising Therapeutic Target to Improve Cognitive Deficits in Down Syndrome. Brain Sci 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Martinez, P.; Zahonero, C.; Sanchez-Gomez, P. DYRK1A: The double-edged kinase as a protagonist in cell growth and tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Oncol, 2015, 2, e970048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Martínez, P.; Zahonero, C.; Sánchez-Gómez, P. DYRK1A: The double-edged kinase as a protagonist in cell growth and tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Oncol, 2015, 2, e970048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firth, H.V.; Richards, S.M.; Bevan, A.P.; Clayton, S.; Corpas, M.; Rajan, D.; Van Vooren, S.; Moreau, Y.; Pettett, R.M.; Carter, N.P. DECIPHER: Database of Chromosomal Imbalance and Phenotype in Humans Using Ensembl Resources. American journal of human genetics, 2009, 84, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fotaki, V.; Dierssen, M.; Alcántara, S.; Martínez, S.; Martí, E.; Casas, C.; Visa, J.; Soriano, E.; Estivill, X.; Arbonés, M.L. Dyrk1A haploinsufficiency affects viability and causes developmental delay and abnormal brain morphology in mice. Molecular and cellular biology, 2002, 22, 6636–6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cerro, S.; Martínez, P.; Vidal, V.; Corrales, A.; Flórez, J.; Vidal, R.; Rueda, N.; Arbonés, M.L.; Martínez-Cué, C. Overexpression of Dyrk1A is implicated in several cognitive, electrophysiological and neuromorphological alterations found in a mouse model of Down syndrome. PLoS ONE, 2014, 9, e106572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodlett, C.R.; Stringer, M.; LaCombe, J.; Patel, R.; Wallace, J.M.; Roper, R.J. Evaluation of the therapeutic potential of Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) via oral gavage in young adult Down syndrome mice. Scientific reports, 2020, 10, 10426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedj, F.; Pereira, P.L.; Najas, S.; Barallobre, M.J.; Chabert, C.; Souchet, B.; Sebrie, C.; Verney, C.; Herault, Y.; Arbones, M.; Delabar, J.M. DYRK1A: A master regulatory protein controlling brain growth. Neurobiol Dis, 2012, 46, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurovich, Y.; Hanani, Y.; Bar, O.; Nadav, G.; Fleischer, N.; Gelbman, D.; Basel-Salmon, L.; Krawitz, P.M.; Kamphausen, S.B.; Zenker, M.; Bird, L.M.; Gripp, K.W. Identifying facial phenotypes of genetic disorders using deep learning. Nat Med, 2019, 25, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hämmerle, B.; Elizalde, C.; Tejedor, F.J. The spatio-temporal and subcellular expression of the candidate Down syndrome gene Mnb/Dyrk1A in the developing mouse brain suggests distinct sequential roles in neuronal development. Eur J Neurosci, 2008, 27, 1061–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammerle, B.; Ulin, E.; Guimera, J.; Becker, W.; Guillemot, F.; Tejedor, F.J. Transient expression of Mnb/Dyrk1a couples cell cycle exit and differentiation of neuronal precursors by inducing p27KIP1 expression and suppressing NOTCH signaling. Development, 2011, 138, 2543–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hämmerle, B.; Vera-Samper, E.; Speicher, S.; Arencibia, R.; Martínez, S.; Tejedor, F.J. Mnb/Dyrk1A is transiently expressed and asymmetrically segregated in neural progenitor cells at the transition to neurogenic divisions. Dev Biol, 2002, 246, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, L.E.; Stringer, M.; Deal, A.J.; Folz, A.; Goodlett, C.R.; Roper, R.J. Sex-specific developmental alterations in DYRK1A expression in the brain of a Down syndrome mouse model. Neurobiol Dis, 2024, 190, 106359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haworth, K.E.; Wilson, J.M.; Grevellec, A.; Cobourne, M.T.; Healy, C.; Helms, J.A.; Sharpe, P.T.; Tucker, A.S. Sonic hedgehog in the pharyngeal endoderm controls arch pattern via regulation of Fgf8 in head ectoderm. Dev Biol, 2007, 303, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herault, Y.; Delabar, J.M.; Fisher, E.M.C.; Tybulewicz, V.L.J.; Yu, E.; Brault, V. Rodent models in Down syndrome research: Impact and future opportunities. Dis Model Mech, 2017, 10, 1165–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikasa, H.; Sokol, S.Y. Wnt signaling in vertebrate axis specification. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2013, 5, a007955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, F.; Benzing, T.; Katsanis, N. Ciliopathies. N Engl J Med, 2011, 364, 1533–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.Y.; Park, J.I.; Lee, M.; Munoz, W.A.; Miller, R.K.; Ji, H.; Gu, D.; Ezan, J.; Sokol, S.Y.; McCrea, P.D. Down's-syndrome-related kinase Dyrk1A modulates the p120-catenin-Kaiso trajectory of the Wnt signaling pathway. J Cell Sci, 2012, 125, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, R.; LaCombe, J.; Patel, R.; Blackwell, M.; Thomas, J.R.; Sloan, K.; Wallace, J.M.; Roper, R.J. Increased dosage and treatment time of Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) negatively affects skeletal parameters in normal mice and Down syndrome mouse models. PLoS ONE, 2022, 17, e0264254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Lee, H.; Argiropoulos, B.; Dorrani, N.; Mann, J.; Martinez-Agosto, J.A.; Gomez-Ospina, N.; Gallant, N.; Bernstein, J.A.; Hudgins, L.; Slattery, L.; Isidor, B.; Le Caignec, C.; David, A.; Obersztyn, E.; Wiśniowiecka-Kowalnik, B.; Fox, M.; Deignan, J.L.; Vilain, E.; Hendricks, E.; Horton Harr, M.; Noon, S.E.; Jackson, J.R.; Wilkens, A.; Mirzaa, G.; Salamon, N.; Abramson, J.; Zackai, E.H.; Krantz, I.; Innes, A.M.; Nelson, S.F.; Grody, W.W.; Quintero-Rivera, F. DYRK1A haploinsufficiency causes a new recognizable syndrome with microcephaly, intellectual disability, speech impairment, and distinct facies. Eur J Hum Genet, 2015, 23, 1473–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Liu, C.; Yu, T.; Zhang, L.; Meng, K.; Xing, Z.; Belichenko, P.V.; Kleschevnikov, A.M.; Pao, A.; Peresie, J.; Wie, S.; Mobley, W.C.; Yu, Y.E. Genetic dissection of the Down syndrome critical region. Human molecular genetics, 2015, 24, 6540–6551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.F.; Nguyen, H.T.; Veitia, R.A. Causes and effects of haploinsufficiency. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc, 2019, 94, 1774–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, H.K.; Wahl, S.E.; Sesay, F.; Litovchick, L.; Dickinson, A.J. Dyrk1a is required for craniofacial development in Xenopus laevis. Dev Biol, 2024, 511, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczorowska, N.; Kaczorowski, K.; Laskowska, J.; Mikulewicz, M. Down syndrome as a cause of abnormalities in the craniofacial region: A systematic literature review. Adv Clin Exp Med, 2019, 28, 1587–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay, L.J.; Smulders-Srinivasan, T.K.; Soundararajan, M. Understanding the Multifaceted Role of Human Down Syndrome Kinase DYRK1A. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol, 2016, 105, 127–171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, O.H.; Cho, H.J.; Han, E.; Hong, T.I.; Ariyasiri, K.; Choi, J.H.; Hwang, K.S.; Jeong, Y.M.; Yang, S.Y.; Yu, K.; Park, D.S.; Oh, H.W.; Davis, E.E.; Schwartz, C.E.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, H.G.; Kim, C.H. Zebrafish knockout of Down syndrome gene, DYRK1A, shows social impairments relevant to autism. Molecular autism, 2017, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, R.D.; Schilling, T.F. Cranial neural crest and development of the head skeleton. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2006, 589, 120–133. [Google Scholar]

- Kofron, M.; Demel, T.; Xanthos, J.; Lohr, J.; Sun, B.; Sive, H.; Osada, S.; Wright, C.; Wylie, C.; Heasman, J. Mesoderm induction in Xenopus is a zygotic event regulated by maternal VegT via TGFbeta growth factors. Development, 1999, 126, 5759–5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Park, S.; Lee, U.; Kim, J. The Organizer and Its Signaling in Embryonic Development. J Dev Biol 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaCombe, J.M.; Sloan, K.; Thomas, J.R.; Blackwell, M.P.; Crawford, I.; Bishop, F.; Wallace, J.M.; Roper, R.J. Sex-specific trisomic Dyrk1a-related skeletal phenotypes during development in a Down syndrome model. Dis Model Mech 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguna, A.; Aranda, S.; Barallobre, M.J.; Barhoum, R.; Fernández, E.; Fotaki, V.; Delabar, J.M.; de la Luna, S.; de la Villa, P.; Arbonés, M.L. The protein kinase DYRK1A regulates caspase-9-mediated apoptosis during retina development. Developmental cell, 2008, 15, 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguna, A.; Barallobre, M.J.; Marchena, M.; Mateus, C.; Ramírez, E.; Martínez-Cue, C.; Delabar, J.M.; Castelo-Branco, M.; de la Villa, P.; Arbonés, M.L. Triplication of DYRK1A causes retinal structural and functional alterations in Down syndrome. Human molecular genetics, 2013, 22, 2775–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lana-Elola, E.; Aoidi, R.; Llorian, M.; Gibbins, D.; Buechsenschuetz, C.; Bussi, C.; Flynn, H.; Gilmore, T.; Watson-Scales, S.; Haugsten Hansen, M.; Hayward, D.; Song, O.R.; Brault, V.; Herault, Y.; Deau, E.; Meijer, L.; Snijders, A.P.; Gutierrez, M.G.; Fisher, E.M.C.; Tybulewicz, V.L.J. Increased dosage of DYRK1A leads to congenital heart defects in a mouse model of Down syndrome. Sci Transl Med, 2024, 16, eadd6883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lana-Elola, E.; Watson-Scales, S.; Slender, A.; Gibbins, D.; Martineau, A.; Douglas, C.; Mohun, T.; Fisher, E.M.; Tybulewicz, V.L. Genetic dissection of Down syndrome-associated congenital heart defects using a new mouse mapping panel. eLife 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Nagashima, K.; Yoon, J.; Sun, J.; Wang, Z.; Carpenter, C.; Lee, H.K.; Hwang, Y.S.; Westlake, C.J.; Daar, I.O. CEP97 phosphorylation by Dyrk1a is critical for centriole separation during multiciliogenesis. J Cell Biol 2022, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Ha, J.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, Y.S.; Chang, E.J.; Song, W.J.; Kim, H.H. Negative feedback Inhibition of NFATc1 by DYRK1A regulates bone homeostasis. The Journal of biological chemistry, 2009, 284, 33343–33351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litovchick, L.; Florens, L.; Swanson, S.K.; Washburn, M.P.; DeCaprio, J.A. DYRK1A protein kinase promotes quiescence and senescence through DREAM complex assembly. Genes & development, 2011, 25, 801–813. [Google Scholar]