3.2. Radiation Chemical Yield in Sensitized Radiation-Induced Polymerization and Polymerization Mechanisms

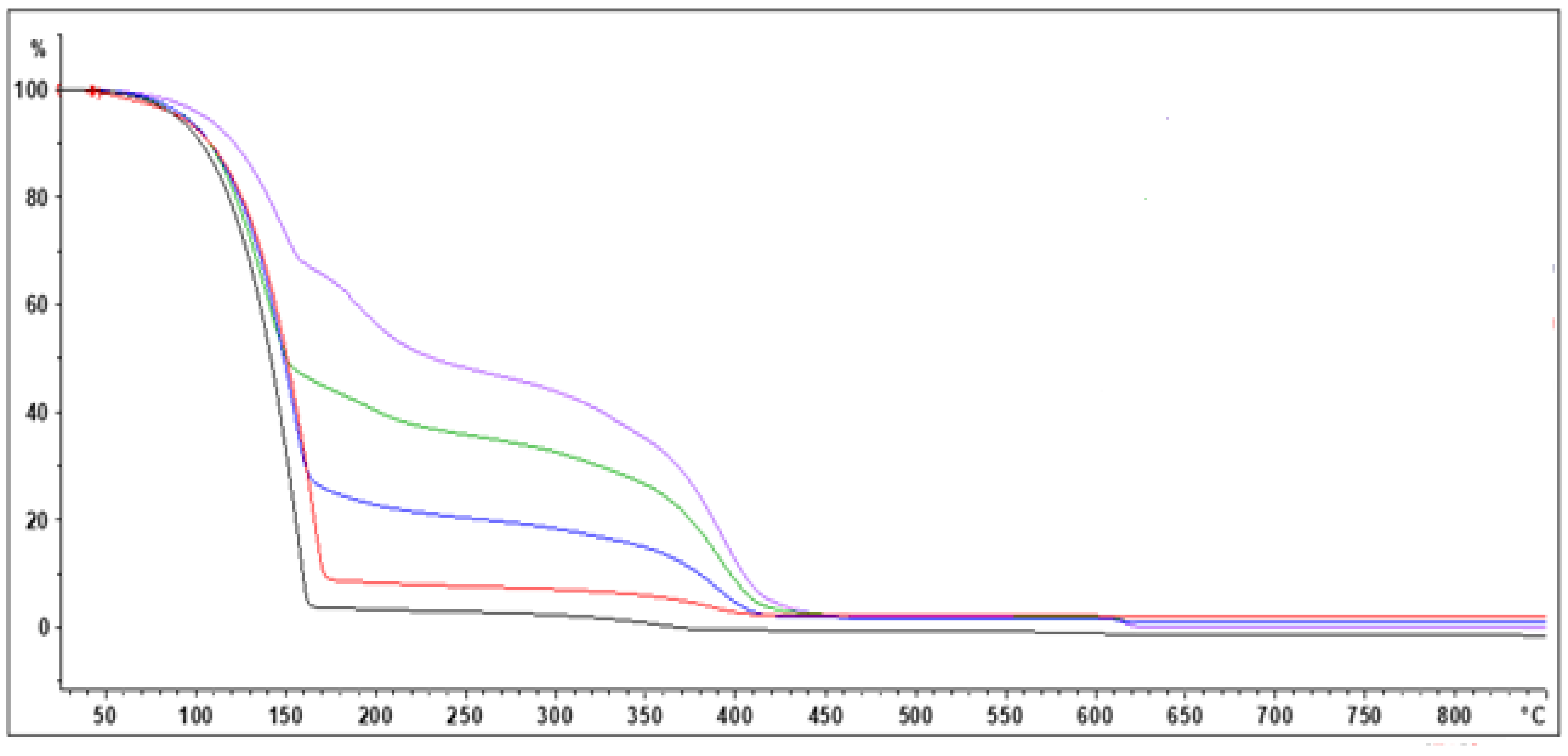

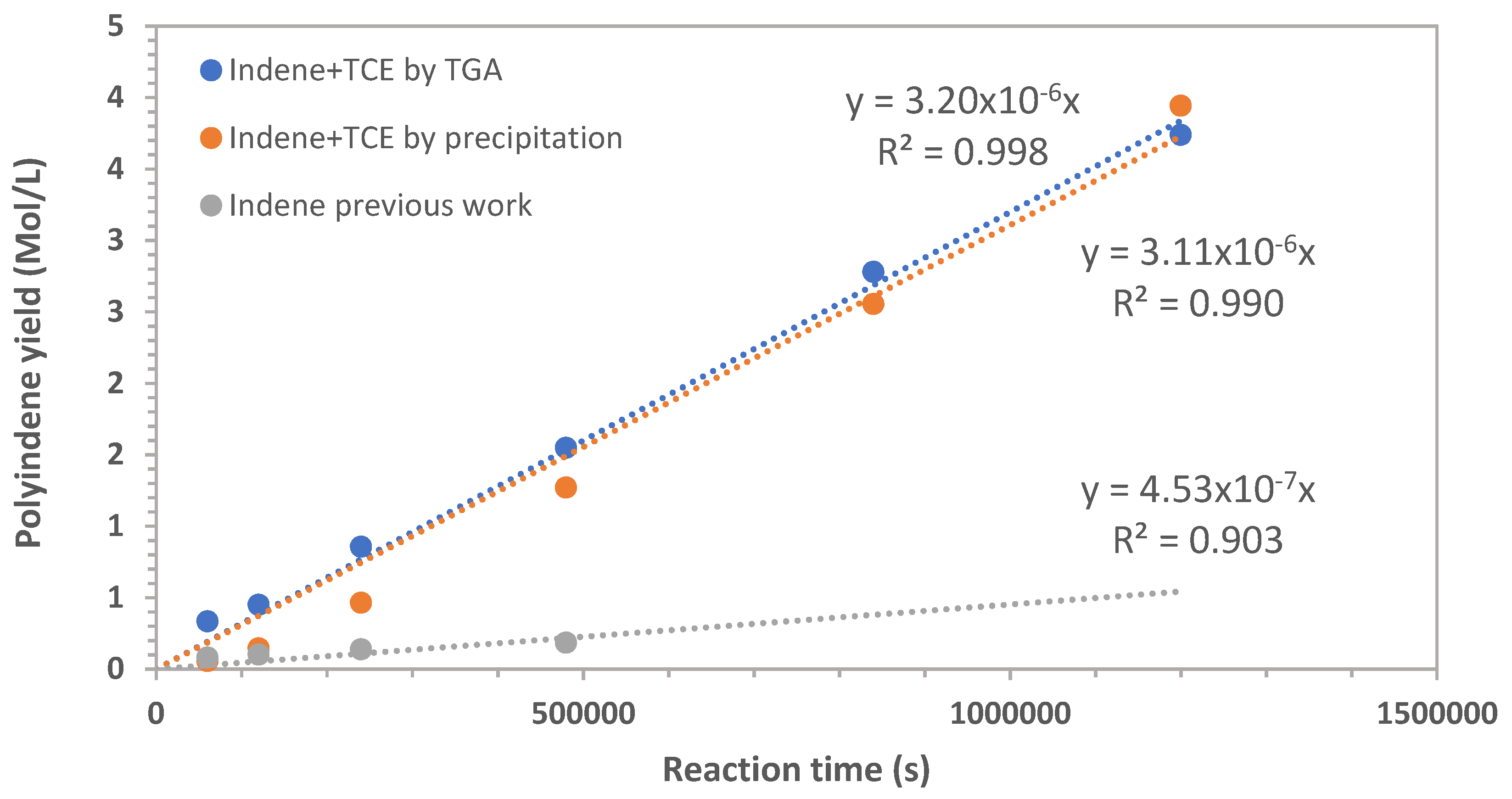

From the polyindene yield results measured with the precipitation method at different doses, the radiation chemical yield of polymerization G

p can be determined using [

11]:

where G

p is monomer molecules/100 eV transformed into polymer and Q is the polymer yield expressed in g, q is the mass of the irradiated monomer (in g), U is the dose in kGy and m the monomer molecular weight (i.e. 116.16 Dalton for indene).

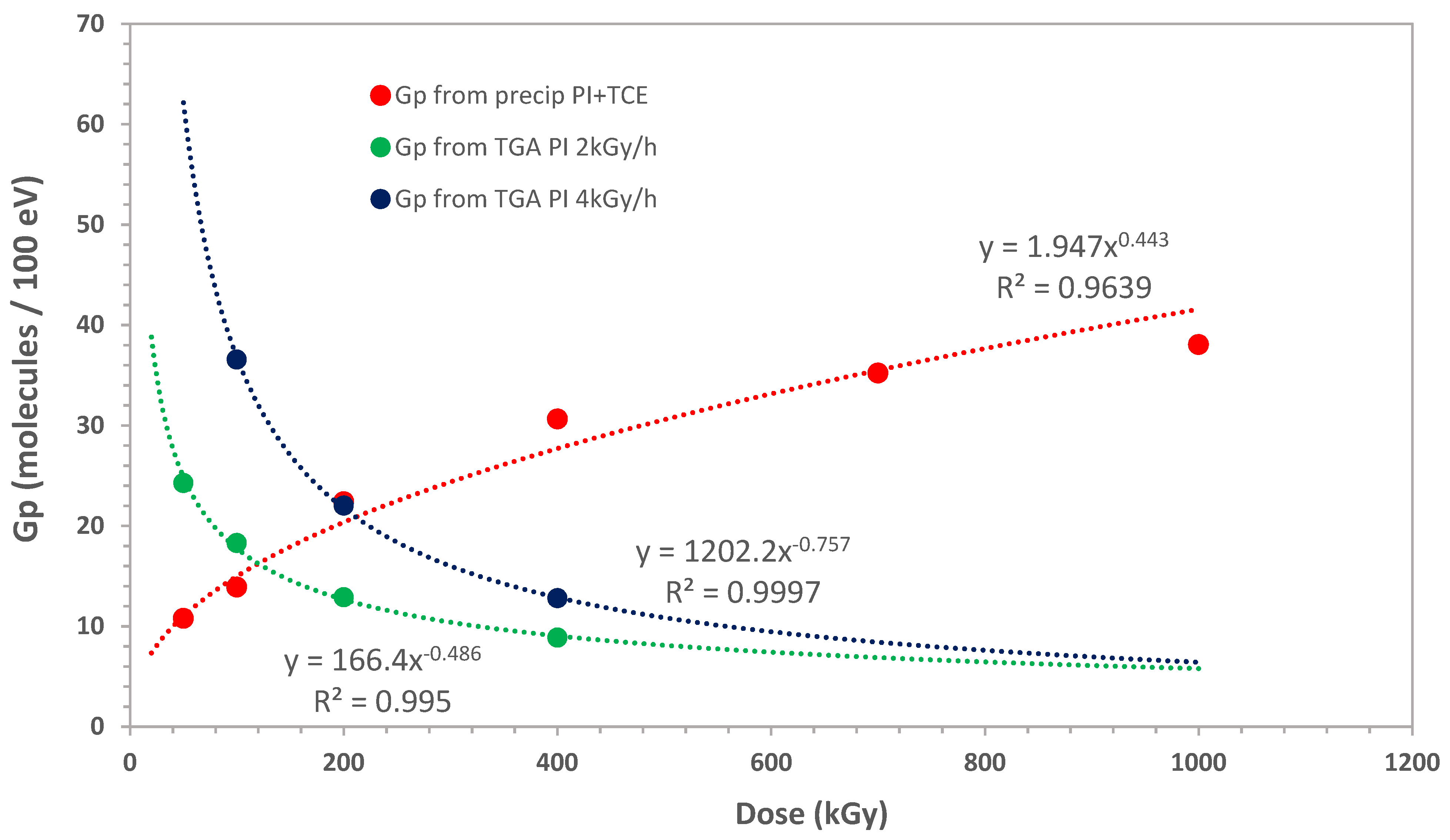

As shown in

Figure 5 the radiation chemical yield experimental data can be fitted by a power law having the form of:

when the indene monomer is polymerized in bulk, using the experimental data of the previous work [

1]. At 2 kGy/h the factor A = 166.4 and the exponent ϕ = 0.486, while at 4 kGy/h A = 1200 and ϕ = 0.757. The meaning of eq. 2 could be interpreted in terms of energy efficiency. At a given dose rate, the radiation chemical yield is maximum at low dose and vanishingly small at very high doses. Indeed, this means that the high energy radiation absorbed by the monomer is better transformed in chemical yield at lower doses.

It is noteworthy that the eq. (3) has the same form of the equation linking the G

p with the dose rate Ů, with K including different constants [

11,

12,

13]:

In other words, the radiation chemical yield for the polymer formation is inversely proportional to the square root of the dose rate (eq. 4) and in our study with eq. 3 we have found that this type of power law applies also to the total dose, although the exponent ϕ deviates from the 0.5 value.

The experimental data relative to the radiation-induced polymerization of indene sensitized by TCE can be either fitted by a power law (

Figure 5). However, this time the exponent of the dose U is positive:

with A = 1.947 and the exponent ϕ = 0.443. In the sensitized indene polymerization the trend of Gp is just opposite to that observed in bulk and unsensitized polymerization.

It is evident that the presence of a sensitizer like TCE enhances the overall energetic efficiency of the process, especially at high dose.

The sensitizer acts essentially as energy transfer agent, absorbing the high energy radiation in a better way than the monomer and transferring then the energy to the monomer. To exhert this effect the sensitizer in general is characterized by a higher sensitivity to high energy radiation with G

R (radiation chemical yield of radicals) values much higher with respect to the G

R(M). For instance, Ivanov [

11] reports G

R = 25, 37 and 44 radicals/100 eV respectively for CCl

4, CHCl

3 and CHBr

3 used as sensitizers. These values should be compared with G

R(M) = 0.69 radicals/100 eV measured on pure styrene [

14,

15], a monomer similar to the chemical structure of indene [

2]. TCE with its structure Cl

2CH-CHCl

2 recalls especially the chemical structure of CHCl

3 and should show similar G

R values as chloroform. Furthermore, the sensitization effect is not only a matter of higher concentration of free radicals and hence easier polymerization initiation, but the sensitizer could address also a parallel mechanism involving cationic polymerization because the radiolysis of haloalkanes used as sensitizers generate certain species which are able to promote also the cationic mechanism in parallel to the free radical, as already noticed by earlier investigators [

14]. The overall effect of the sensitizer is translated in practice into a better utilization of the high energy radiation, leading to higher polymer yields especially at higher doses, while at lower dose the effect in G

p values appears less evident as can be observed in

Figure 5.

Regarding the cationic mechanism which should be active in parallel to the free radical mechanism, and which contributes either to the enhancement of the polymerization kinetics and the polymer yield, it is necessary to make some considerations starting from the radiolysis of pure halocarbons first. While the radiolysis of CCl

4 yelds Cl

2 (G = 0.75), other products but no HCl, the radiolysis of CHCl

3, CH

2Cl

2, n-C

3H

6-Cl and Cl

2C=CHCl produces HCl with G ≈ 5 molecules/100 eV, other products but no Cl

2 [

15]. Similar radiation chemical yield values for HCl production were recently observed in the radiolysis of 10 different chloroalkanes [

16]. According to Milinchuk and Tupikov data [

15], TCE represents an

unicum with an intermediate behaviour between CCl

4 and the other chloroalkanes considered here, yielding simultaneously HCl (G = 7.2) and Cl

2 (G = 2.7). Since HCl is considered a catalyst in cationic polymerization [

2], it is immediately evident that the in situ formation of HCl is a powerful source in promoting the cationic mechanism of indene polymerization, in parallel with the free radical mechanism.

Furthermore, studies on the radiolysis of TCE in hydrocarbons, like for instance cyclohexane [

17], have revealed that the radiation chemical yield of HCl is dramatically enhanced G = 21.6 with formation of trichloroethane G = 118, trichloroethyl radicals and numerous other chlorinated hydrocarbons which can be generically represented as R-Cl.

According to Mehnert [

12], in the irradiation of alkyl chlorides, the electron produced in in the primary ion pair is converted to unreactive chloride ion by dissociative electron capture leading to a radical:

while the alkyl chloride cation transfers its charge to the monomer M, initiating the cationic polymerization:

The cationic polymerization is further sustained by the presence of HCl, the relatively high dielectric constant of TCE (ε = 8.50 and μ = 1.32 Debye [

18]) while indene ε ≈ 2.5. Thus, the above scheme proposed by Mehnert [

12] explains the simultaneous free radical and cationic mechanism initiation.

As deeply discussed in a previous work [

2], the experimental evidences of the cationic polymerization of indene can be detected visually and spectrophotometrically. The polyindenyl cation gives a blood-red color to the solution and such color is quite stable for a long time. Furthermore, the polyindenyl cation is characterized by an absorption band at 521 nm [

2]. The solutions irradiated at 400, 700 and 1000 kGy are characterized by such blood-red color and the polyindenes, once precipitated with ethanol excess from the irradiated solutions present a reddish color which persists even after drying. The KBr pellets of these polyindenes examined with the spectrophotometer show a broad but distinctive peak at 521 nm. Thus, the cationic polymerization mechanism was certainly in action in parallel with the free radical mechanism during the irradiation of the indene solutions in presence of TCE.

3.3. Molecular Weight and Chemical Structure of Polyindene Obtained in Sensitized Radiation-Induced Polymerization

It is well known that the radiation-induced polymerization in presence of sensitizers represented by chlorinated hydrocarbons is characterized by high initiation rates but also by high termination rates, because of the high concentration of free radicals [

11,

12,

13]. This condition leads to high polymer yields characterized by low molecular weight. Such a process is also known as telomerization [

11,

12,

13].

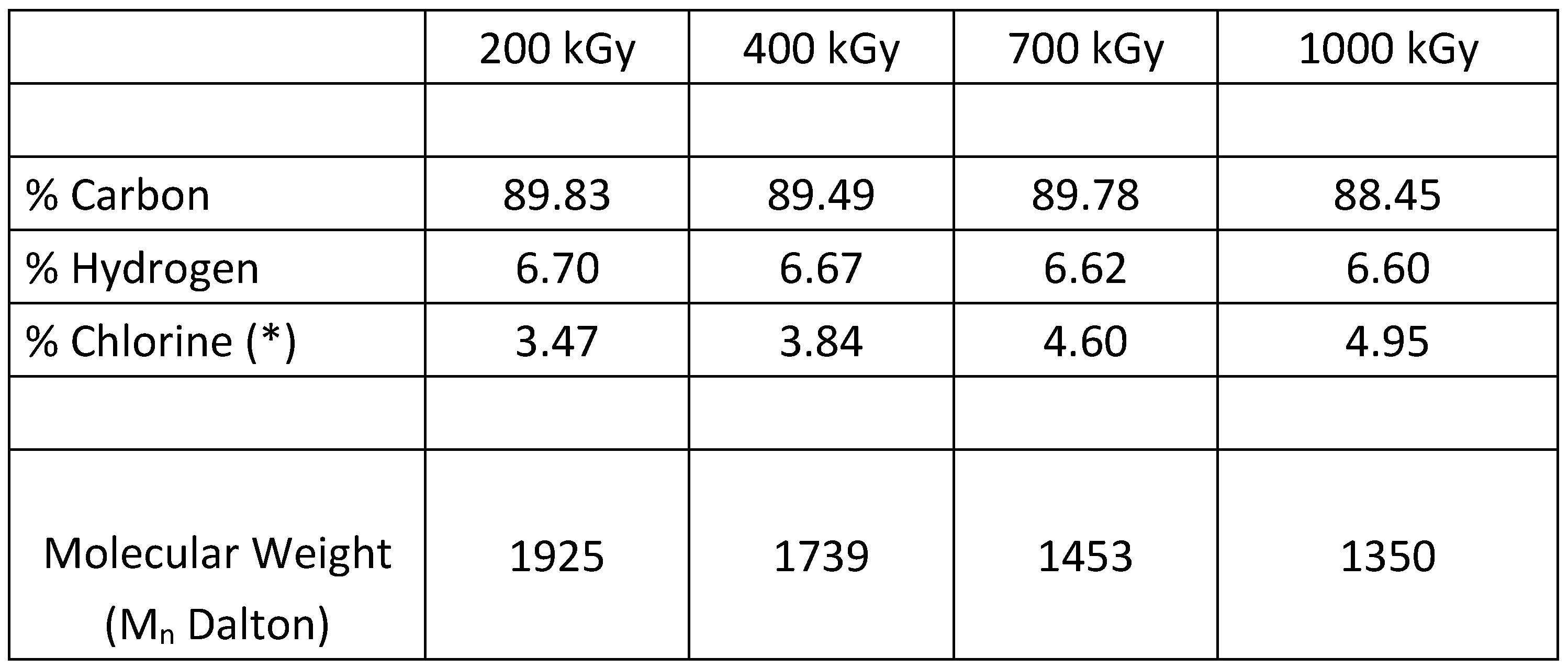

The polyindenes samples isolated with the precipitation method, were subjected to the X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis for the determination of the chlorine content. From these data the elemental composition of the samples produced at the selected doses were determined with the basic and plausible assumption that the end groups of the polyindene chains are composed by chlorine atoms. This assumption is made on the basis of the radiolysis products of TCE which involve mainly HCl and Cl

2 (when radiolyzed as pure liquid) [

15].

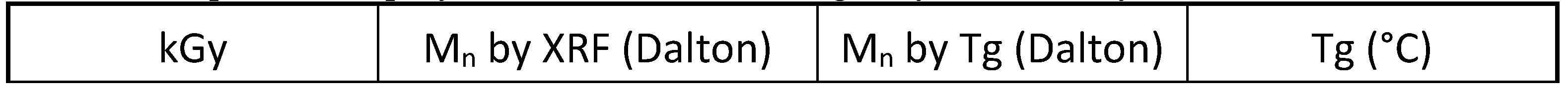

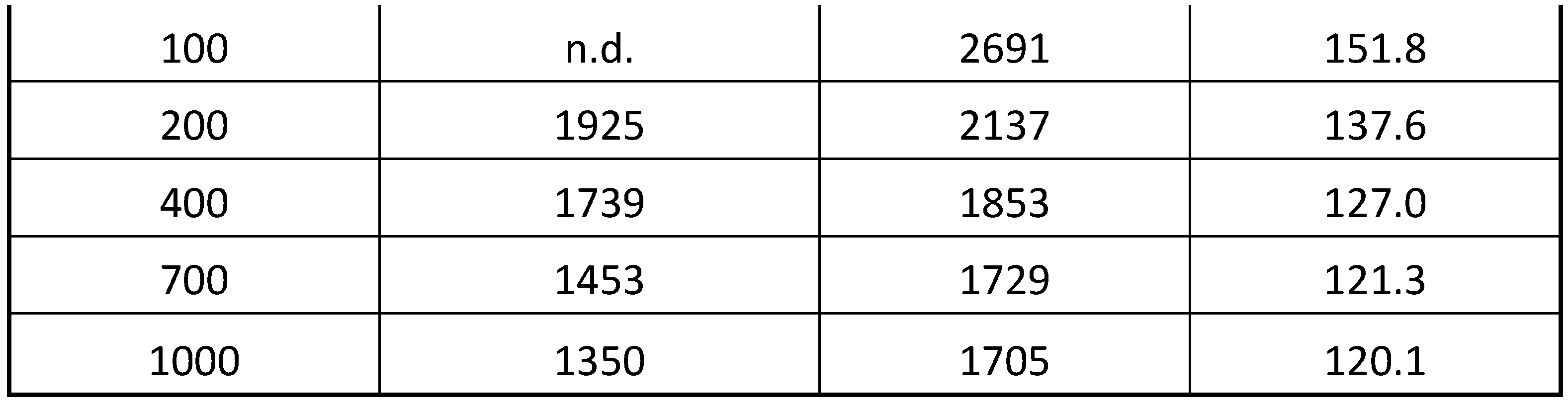

The XRF analysis shows that the chlorine content in polyindene increases linearly with the dose and this fact is reasonable since at higher doses there is more polymer yield but with shorter chains, as indeed it is shown in

Table 1.

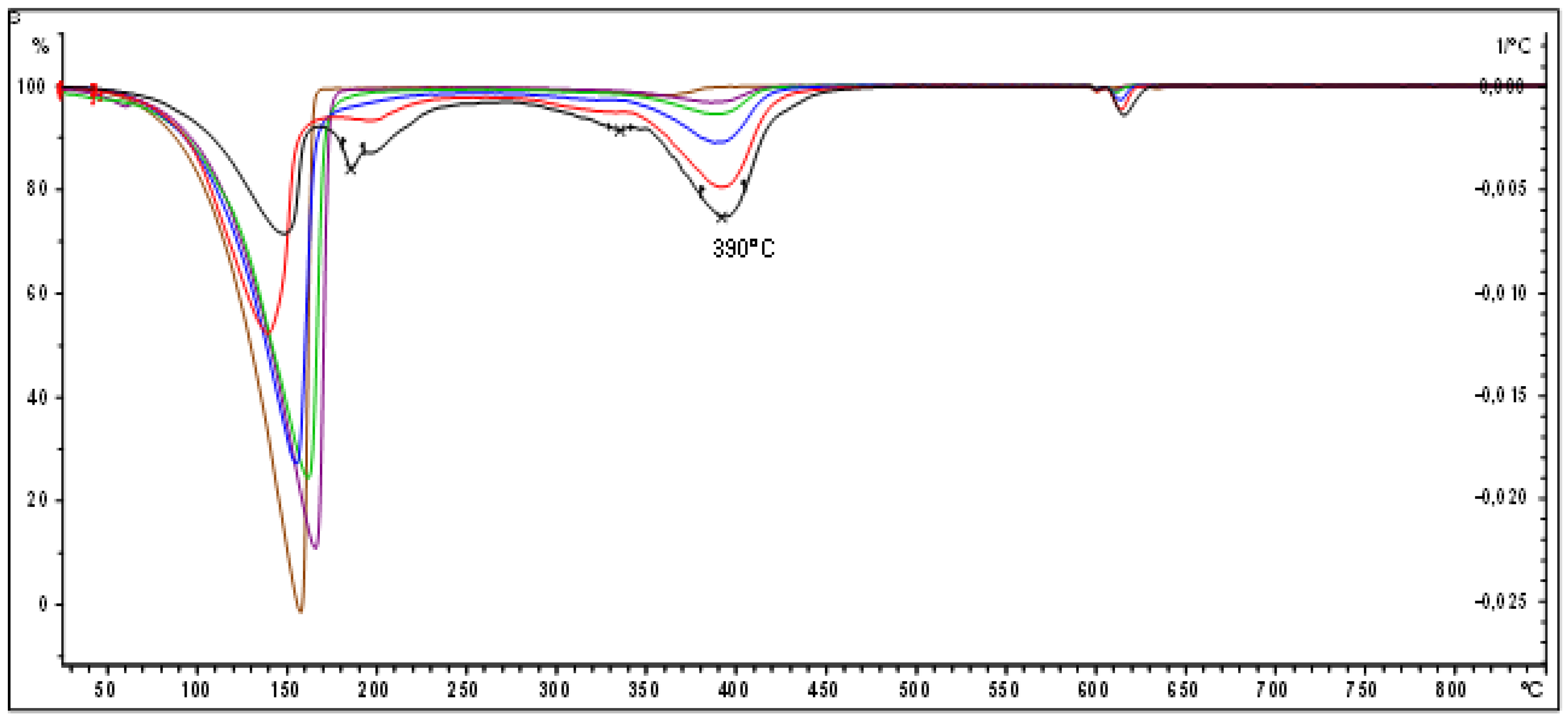

An alternative and indirect way to estimate the molecular weight (M

n) of polyindene is through the determination of the glass transition (T

g) as shown in a previous work [

2]. Using the equation proposed by Hahn and Hillmyer:

the T

g of the polyindene samples was determined by DSC at a heating rate of 10°C/min under N

2 flow.

Table 2 shows a summary of the T

g results and the corresponding molecular weight calculated with eq. 10. Indeed, these polyindene samples obtained by radiolysis in presence of the TCE sensitizer the T

g was found at considerably lower temperatures than in the case of polyindenes synthesized by bulk radiolysis or by chemical initiations [

2].

For instance, polyindene produced by radiolysis in bulk shows T

g = 176.5°C and Mn ≈ 5000 Da, while polyindene produced by cationic polymerization has a T

g = 205°C and Mn ≈ 90000 Da.

Table 2 shows that all polyindenes produced in presence of TCE are characterized by T

g values comprised between 152°C and 120°C, with the lowest T

g values at the higher doses. This fact, is translated into a confirmation of lower molecular weight for the polyindenes obtained in presence of the sensitizer and a good correlation with the molecular weight measured from the chlorine content.

Particularly interesting is the fact that the lowest molecular weight values are found on the samples prepared at higher doses. This is fully in line with the theory which predicts lower molecular weight of polymers at high doses, despite the higher mass yield.

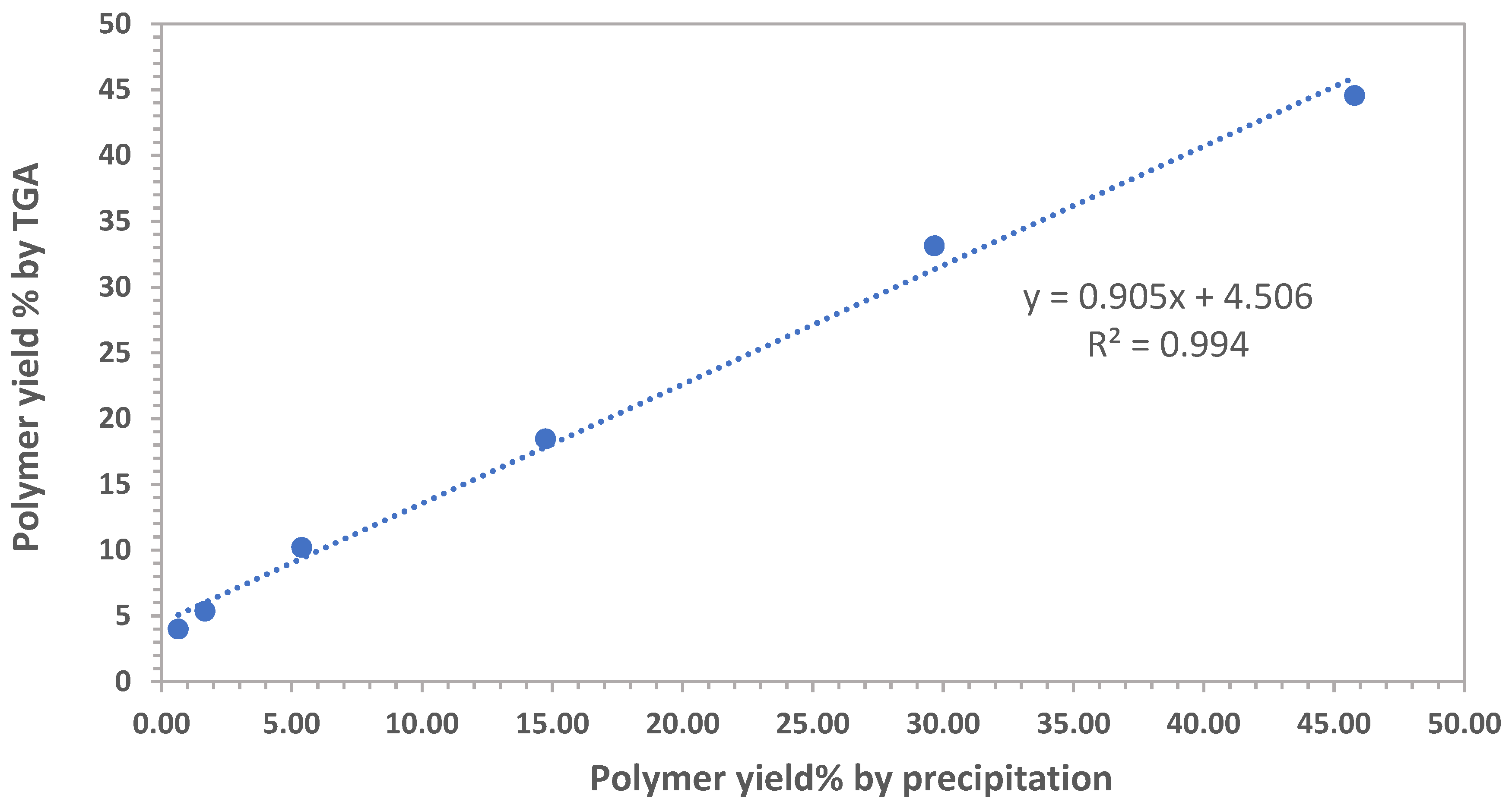

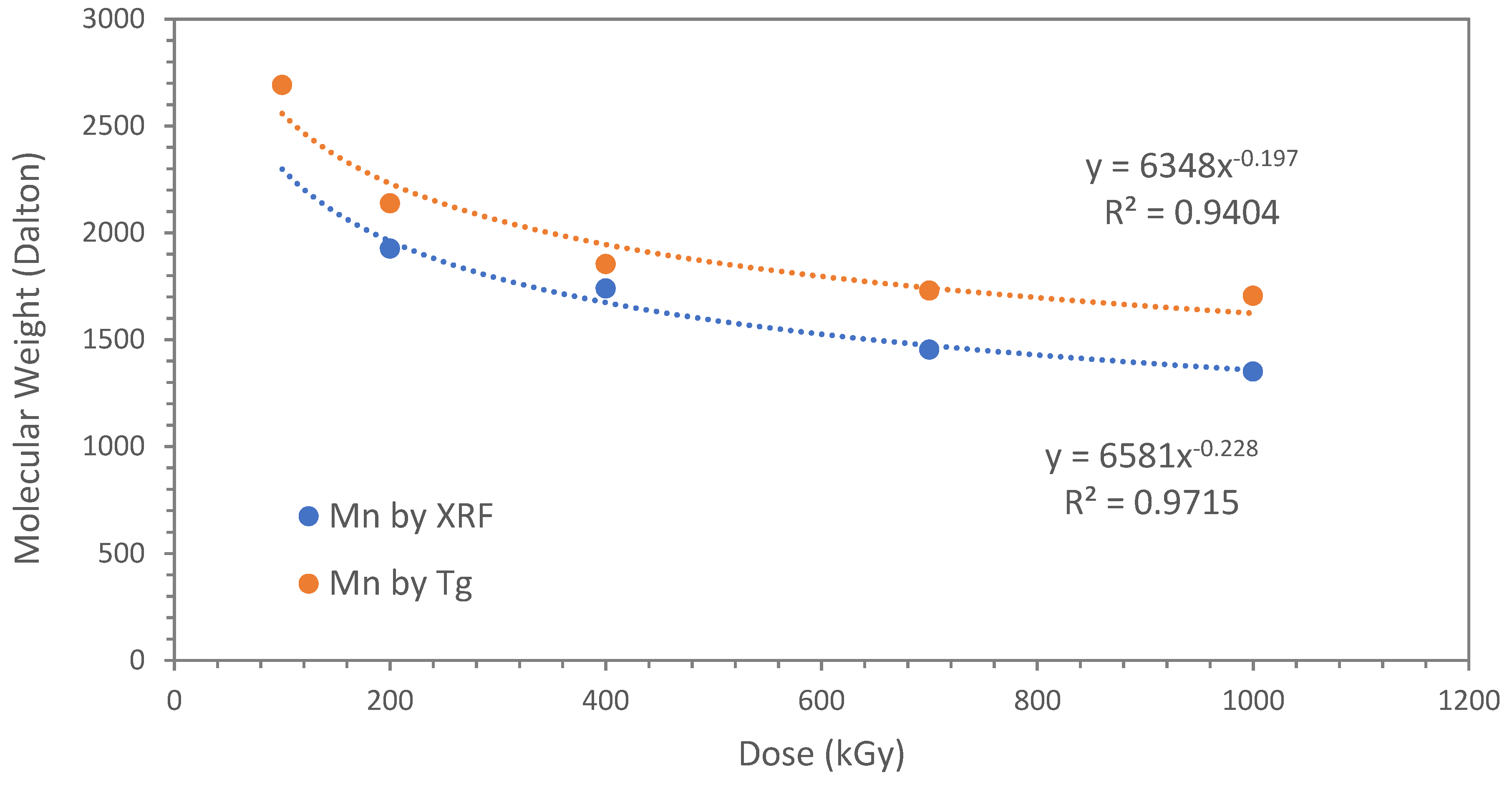

Despite the molecular weights derived from chlorine content (XRF analysis) and those estimated from the T

g (DSC analysis) are not numerically coincident, they follow exactly the same trend as shown in

Figure 6 and the experimental values can be fitted by very similar power law equations with good R

2 values.

Thus, fitting the molecular weight data with dose in the case of the T

g derived values:

while for the Mn derived from XRF and chlorine end groups:

The latter two equations are very similar and the most reliable should be considered eq. 12 which is linked to the direct measurement of the chlorine end groups and hence the true molecular weight. The other equation (eq.11) obtained through a completely different approach and based on the Tg of the polyindenes represents a confirmation of the validity of equation 12.

Based on these results, it appears immediately evident that the telomerization phenomenon [

11] generated by the presence of the TCE sensitizer with high initiation and termination rate and high chain transfer reactions leads to polyindenes with relatively low molecular weight in the range of 1350-2000 Da to be compared with 5000 Da measured on polyindene radiation-polymerized in bulk without additives [

1,

2]. Furthermore, an interesting property of the polyindenes produced in presence of TCE regards the fact that at higher polymer yields (achieved at higher doses) correspond the lowest molecular weight and viceversa.

3.4. FT-IR Spectroscopy of the Polyindenes Obtained by Sensitized Radiation-Induced Polymerization

The FT-IR spectra of polyindenes obtained either with γ irradiation of the indene monomer or with cationic or thermal initiations were already discussed in the previous works [

1,

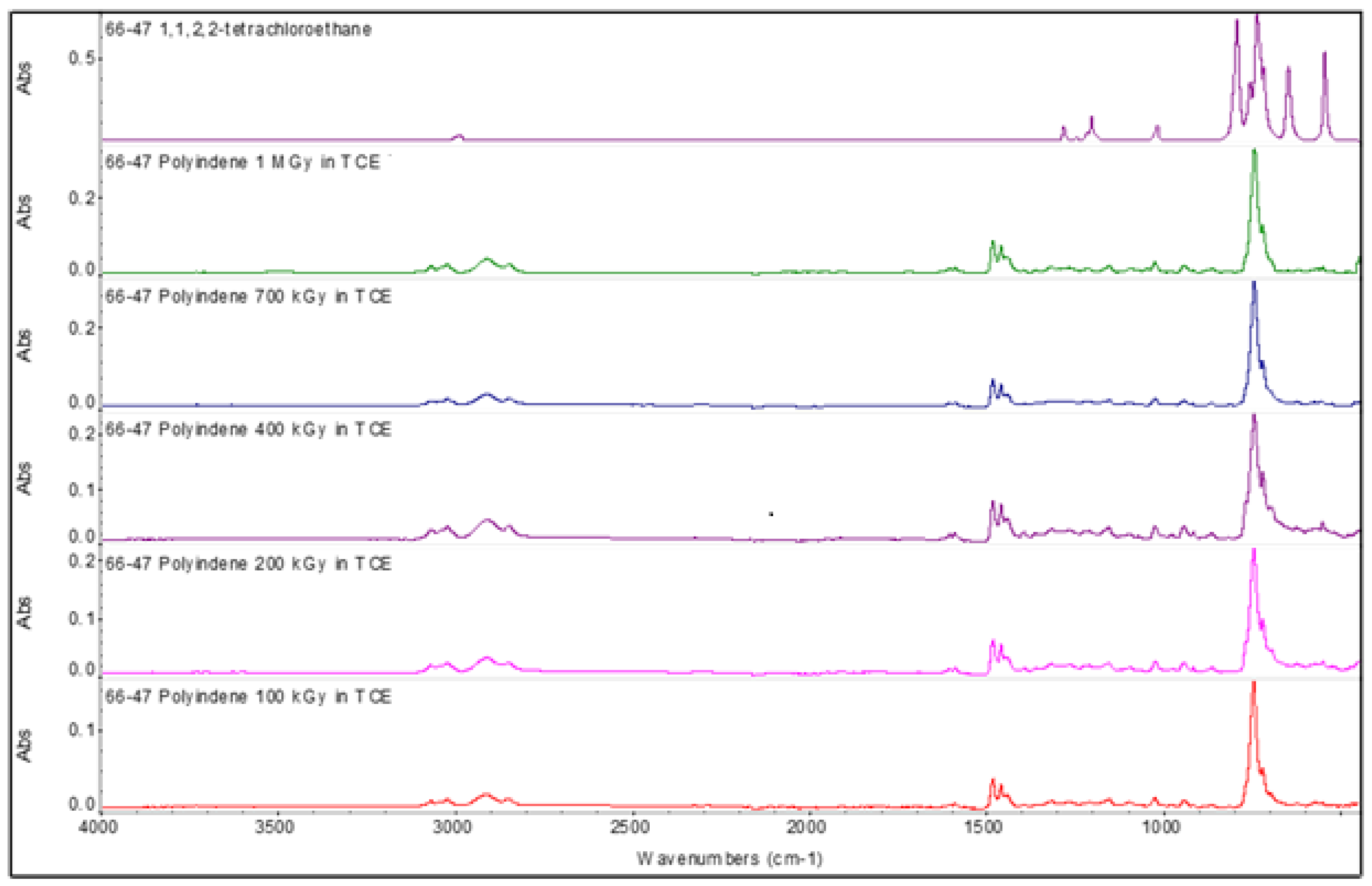

2]. As shown in

Figure 7 the polyindene FT-IR spectrum is dominated by a very strong absorption band at 746 cm

-1 due to the out of plane wagging of four adjacent aromatic C-H groups of indene aromatic ring [

1,

2]. This band is accompanied by another band at 718 cm

-1 due to the indene CH

2 rocking [

1,

2]. It was noticed that the latter band is better defined and well resolved in the polyindene obtained by radiation induced polymerization of indene monomer in bulk and interpreted in terms of high regularity of the resulting chemical structure of the polymer [

1]. On the other hand, for the polyindene synthesized through a pure cationic mechanism, the band at 718 cm

-1 appears poorly resolved and at the limit even appears as a simple shoulder on the main band at 746 cm

-1.

Figure 7 shows that this is the case also for all polyindenes synthesized in the present work using TCE as sensitizer: the band at 718 cm

-1 is indeed poorly resolved. This experimental fact, sustains the idea that the presence of TCE has favored the cationic mechanism (in parallel with the unavoidable free radical mechanism), leading to polyindene samples with chemical structures which report the signature of such a mechanism also on the infrared spectra. After all, it is well known that the chlorinated sensitizers are indeed favoring also the cationic mechanism in the radiation-induced polymerization [

11,

12,

13,

14].

The infrared spectrum of 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane is shown in

Figure 5 and is dominated by the C-Cl stretching bands at 795, 740, 716, 649 and 551 cm

-1 [

20,

21]. It is a quite unfortunate situation that two of these main TCE infrared bands result nearly coincident with the 746 and 718 cm

-1 main bands of polyindene. This precludes any possible attempt to detect the end groups of the polyindene samples obtained in presence of the TCE sensitizer. In fact, apart these two bands that if present are certainly buried by the polyindene vibrations, all the other C-Cl bands of TCE are not detectable at all in the polyindene spectra of the present work.