1. Introduction

The role of three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction in capturing and interpreting real-world environments in widespread applications is becoming increasingly significant. From criminal scene documentation and investigative procedures to architectural conservation, virtual reality, and robotics, generating precise, spatially correct virtual representations of captured imagery or video has never been more useful. Such reconstructions enable professionals to examine and measure environments after the fact, assist in decision-making, facilitate collaboration, and ensure long-term data preservation.

Traditional 3D reconstruction algorithms use photogrammetry [

1,

2]or structured light scanning [

3,

4], which may be slow, computer-intensive, or hardware-dependent. Alternatively, new advances in radiance field-based methods have revolutionized the field, allowing for photorealistic reconstruction from comparatively simple video recordings or image sets. Two of the most prominent and promising among these are Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF) and 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS).

1.1. Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF)

Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF)[

5], introduced in 2020, is a paradigm changer in 3D reconstruction. Rather than explicitly constructing 3D geometry, NeRF learns an underlying volumetric scene function defined by a neural network. Such a function provides an estimate of colour and density at an arbitrary point in space given a viewpoint. In training, a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) is optimized by NeRF so as to mimic the look of a scene in various views from an input set of imagery.

NeRF generates highly accurate renderings with rich detail and view-dependent effects like specular reflections. However, it comes with certain limitations. Training a NeRF model is slow and computationally costly, usually taking hours for each scene. Moreover, its view synthesis performance depends heavily on accurate camera poses and extensive training data.

Despite these challenges, NeRF has found extensive use in research and industry, across applications in visual effects, digitization of cultural heritage, and forensic visualization experiments, because of its realism and capacity to deal with complicated light.

NeRF is not the first step in this new evolution of 3D reconstructions but is, rather, the building block of a family of algorithms, which includes SNeRF[

6], Tetra-NeRF[

7], NeRFacto[

8], Instant-NGP[

9], SPIDR[

10], MERF [

11], and so on. In fact, each one of them solves particular problems and allows for the increment of overall capabilities in different ways.

1.2. 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS)

3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS) [

12,

13] is another recent advancement, which tries to overcome some of the limitations of NeRF. It represents scene points in terms of an ensemble of 3D Gaussians rather than in terms of a dense neural network. Each of them possesses values for position, orientation, size, colour, and opacity, and they get rendered directly through rasterization. This results in significantly faster training and rendering, while maintaining impressive visual quality.

In contrast to NeRF, 3DGS can generate usable reconstructions within minutes rather than hours, so it is extremely suitable for those applications that incur time pressures or have limited resources. It also introduces fewer visual artifacts in some filming scenarios. Such benefits have contributed to the rapid adoption of 3DGS in environments in which speedy feedback and visual clarity are desirable, such as in robotics navigation, in augmented reality, and in forensic documentation processes.

Although advances in algorithms are necessary, input data quality is still an essential consideration in any 3D reconstruction. Properties of cameras such as sensor size, resolution, lens quality, and image stabilization critically impact the capacity of the model to reconstruct geometries and texturing. As demonstrated in earlier research [

14,

15], full-frame sensors generally outperform crop sensors due to their higher sensitivity and broader dynamic range.

Filming techniques, such as maintaining stable movement, capturing from multiple heights, or covering the full object/environment, also play a major role. Such parameters impact the algorithm's ability to reconstruct low-level details, eliminate occlusions, and manage lighting fluctuations.

In this study, we compare side by side NeRF and 3DGS under identical conditions through the use of identical video datasets, recorded using a professional-quality camera equipped with a full-frame sensor and wide-angle lens. The experiments are conducted in both indoor and outdoor settings, representative of real-world environments relevant to forensic and general reconstruction tasks.

Our research aims to assess these algorithms using three key criteria: reconstruction noise, detail preservation, and efficiency of computation. The results are expected to guide professionals and researchers in selecting appropriate tools and capture strategies tailored to their domain-specific requirements.

1.3. Practical Contribution

This study provides clear, evidence-based advice for professionals who want to use 3D reconstruction technologies in practical applications. By evaluating NeRF and 3DGS using identical datasets and controlled filming techniques, the paper identifies which method is better suited for high-fidelity reconstructions in indoor and outdoor environments. These recommendations are highly beneficial for real-world applications in forensic examination, cultural heritage, and computer vision scene reconstruction, in which time is of the essence and visual fidelity is critical. The insights also include useful advice for choosing cameras, movement strategy, and capturing data to ensure optimal reconstruction outcomes.

1.4. Theoretical Contribution

Theoretically, this paper advances existing comparative research in neural radiance field algorithms by formally detailing the advantages and drawbacks of NeRF and Gaussian Splatting in terms of reconstruction noise, detail precision, and computing time. The study introduces a structured evaluation framework that can be used to assess radiance field algorithms from a practical quality standpoint rather than solely based on visual outputs, by combining controlled environments and algorithmic benchmarking. This research bridges the gap between technical development and applied 3D reconstruction practices.

This paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the combined methodology, including the camera setup, filming conditions, data capture techniques, and experimental design used to evaluate NeRF and 3DGS.

Section 3 provides the results of the comparative analysis across indoor and outdoor environments.

Section 4 discusses the findings, highlights the limitations of the current study, and outlines potential directions for future work. Finally,

Section 5 offers concluding remarks.

2. Methodology

This study builds upon a continuous line of research focused on optimizing 3D reconstruction techniques for use in crime scene investigation and other professional fields. Previous work in this research stream has examined the impact of camera parameters, scene conditions, and data capture strategy upon resulting reconstruction quality in an organized manner. In this paper, we build upon those research findings in terms of comparing two dominant radiance field algorithms, NeRF and 3DGS, against identical and validated filming conditions.

The methodology involves а comprehensive camera setup and data capture strategy, supplemented by an organized experimental design in indoors and outdoors. Care has been taken to standardize input conditions since data quality variations can have significant consequences for reconstruction and introduce bias in comparisons.

2.1. Camera Setup

The primary equipment that was used was a SONY a7c [

16] camera with a 24.2MP full-frame Exmor R CMOS BS sensor. This camera was chosen for its full-frame sensor, which results in higher image quality. The lens combined with the camera is a Sigma 14mm f/1.4 DG DN Art lens [

17], which is a wide-angle lens. This lens can capture more data in one pass, which improves the quality of the 3D reconstructions. A DJI RS 4 gimbal was added to the camera setup to create an even more constant capturing method. The gimbal will result in a smoother capture of the environment, with less vibration and thus fewer blurry frames. Constant lighting conditions were maintained across all captures.

To compare the different 3D reconstruction algorithms, particularly in noise reduction, speed of reconstruction, and detail accuracy, we used Postshot [

18](version 0.4.1), an end-to-end software for Radiance Fields to generate the 3DGS and NeRFs. The goal was to determine which radiance field algorithm works best for inside and outside environments.

Two comparison experiments were conducted, and for both comparisons, an optimal dataset was created following the optimal capture methods and camera settings [

14,

15].The datasets were processed with the radiance field algorithms. The generated 3D reconstructions were evaluated based on noise, detail accuracy, and processing time. These criteria were chosen for their importance in forensic applications where both clarity and realism are essential for analysing evidence.

This approach allowed us to identify the optimal algorithm for high-quality 3D reconstructions in indoor and outdoor crime scene scenarios, providing valuable insights for future forensic investigations

2.2. Data Capture Process

The data capture process utilized in the current research was developed in adherence to best practice guidelines developed in our earlier work, which tested different filming styles and camera movement tactics for effects upon 3D reconstruction quality [

15]. Based upon those recommendations, continuous video capture was performed while navigating predefined paths that guaranteed even scene capture, reduced occlusions, and facilitated correct camera pose determination.

Two different environments were utilized for capturing data: an indoor home setting (living room, kitchen, and hallway) and an outdoor city setting (a parking area containing different objects and textures). In each instance, the scenes were captured along a path of loops performed at three vertical heights, low, mid, and high, encircling the objects or environments of interest. This three-height capture approach has previously been demonstrated to greatly optimize reconstruction fidelity, in particular for vertical structures and complex geometries[

14].

The capture process was handheld and done using a gimbal for stabilization. The movement was kept as smooth and continuous as possible to reduce motion blur and ensure consistency in camera trajectory. Care was taken to maintain a consistent walking speed and to avoid sudden camera rotations or changes in lighting, as these are known to introduce artifacts and disrupt parts of the reconstruction pipeline.

Environmental factors were also taken into consideration. The indoor data was collected in a well-lit residential interior with varied furniture and textures to test fine-grained detail capture. Outdoor data was recorded during an afternoon when the sun was out, resulting in high-contrast conditions in terms of shadows, which pose challenges to both algorithms in adapting to lighting.

The captured video sequences were used as input to both 3DGS and NeRF to ensure that algorithms were tested in identical capture environments for an accurate comparison. This process simulates real-world capture cases in forensic or field-based use, where time, location, and illumination can never be fully controlled, but consistency is still crucial for scientific analysis.

2.3. Environmental Setup

In order to quantify the performance of 3DGS and NeRF in real-world scenarios, we created two test scenarios, one indoors and one outdoors. Each setup was selected to include diverse elements with varying geometry, texture, and lighting, reflecting challenges commonly encountered in forensic and spatial reconstruction contexts.

Indoor Environment

The indoor experiment was performed in a complex multi-room setup comprising a living room, kitchen, and hallway. This room contained an assortment of items such as chairs, tables, tableware, closets, ceiling, and various light sources. These were chosen to offer extensive variety both in terms of geometric complexity and surface detail, offering a robust test case for NeRF as well as 3DGS algorithms.

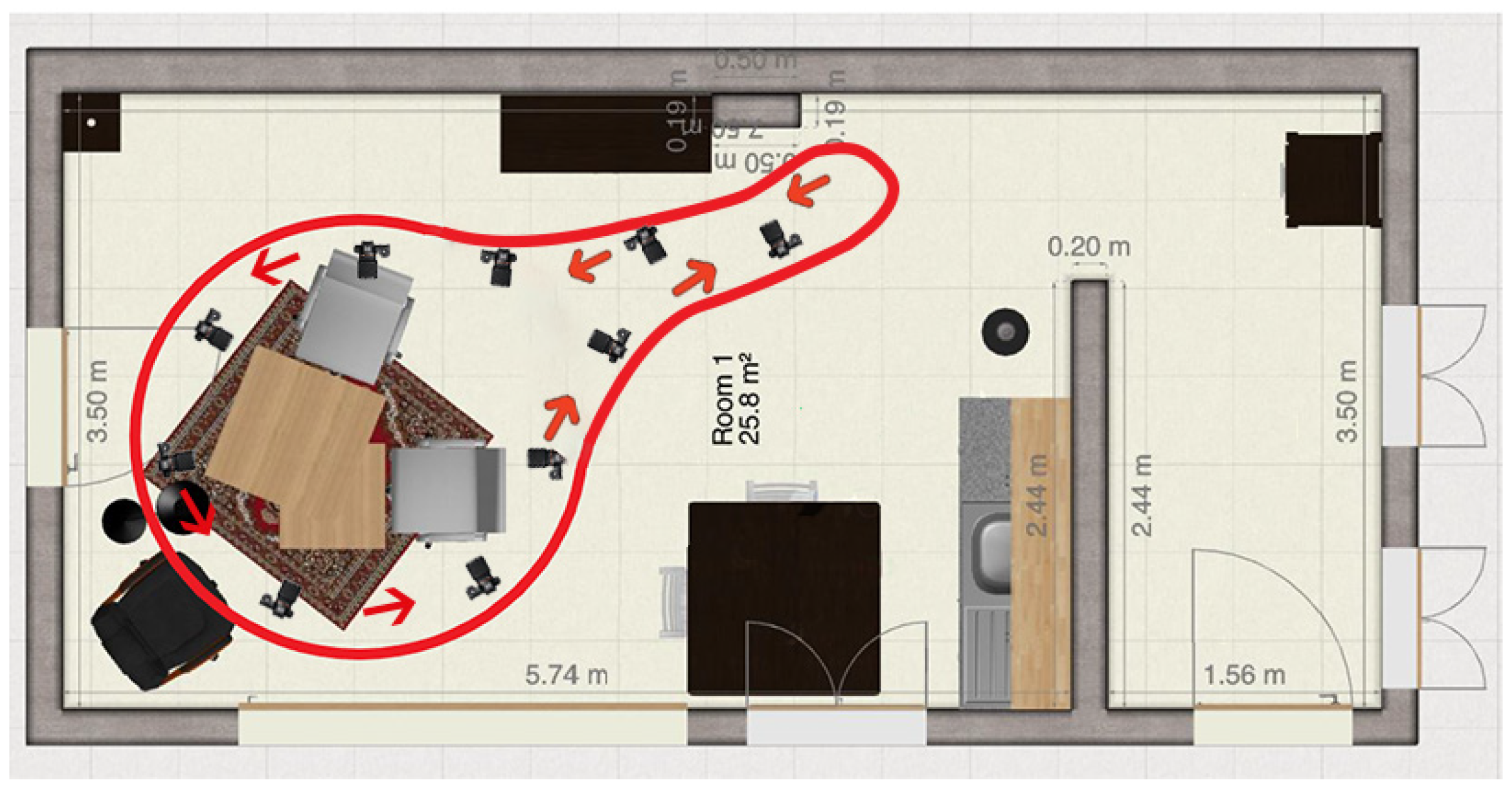

A predefined scan path, illustrated in

Figure 1, was used in data acquisition. In order to provide for extensive coverage and vertical scene understanding, three loops were taken along this path at various heights. This multi-height methodology has been demonstrated to greatly enhance the fidelity in 3D reconstructions for indoor environments [

14]. Wide-angle coverage, combined with vertical diversity, was necessary to provide maximum input for algorithms.

Outdoor Environment

The outdoor experimental setup was held in an open parking area in natural daylight. The scene featured two lines of parking spots, one street lamp, three trees, grassy spots, and one white car. It was selected to offer an array of different materials and light dynamics, such as shaded and illuminated areas, hard ground, and leaves.

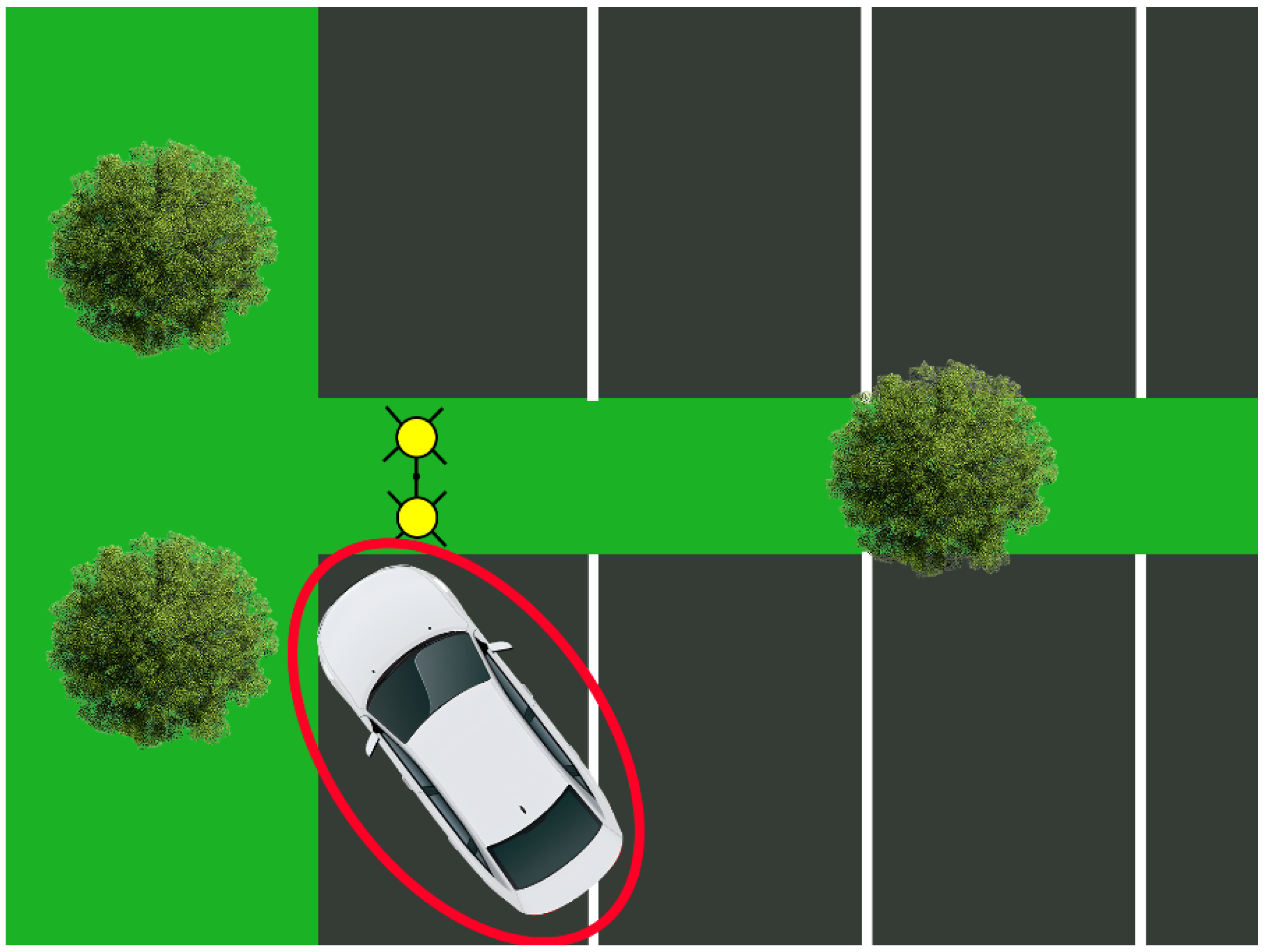

Data capture was done in the afternoon of a summer's day in bright sunlight for consistent lighting. Its scan path, as depicted in

Figure 2, had the operator follow three loops in the scene at varying elevations, similar to what was done in the indoor setup. This allowed the algorithms to leverage multi-angle viewpoints and improve spatial completeness, especially around objects like the vehicle and vertical structures.

Both datasets were captured under identical hardware and capture conditions using the same stabilizer and camera setup explained in

Section 2.1. This consistent approach facilitated direct comparison of the two algorithms in different environments.

2.4. Experimental Design

2.4.1. Algorithm Comparison

To determine which radiance field algorithm is more suitable for 3D reconstruction in different environmental contexts, two controlled comparisons were conducted—one in an outdoor setting and the other indoors. Both experiments used identical hardware and capture methodology to ensure consistency and to isolate the effect of the reconstruction algorithm.

Comparison 1: Outdoor Environment

The first experiment focused on reconstructing an outdoor environment captured in a parking lot, featuring a mix of natural and artificial elements such as trees, grass, asphalt, a streetlamp, and a white car. The camera setup described in

Section 2.1 was used to capture a continuous video sequence following the predefined scan path, showed in

Figure 2. This dataset was then processed using both NeRF and 3DGS algorithms. The resulting 3D reconstructions were evaluated based on visual fidelity, processing efficiency, and artifact presence.

Comparison 2: Indoor Environment

The second experiment targeted a multi-room indoor environment including a kitchen, living room, and hallway, showed in

Figure 1. The same camera configuration and multi-loop scan path strategy were applied to maintain data quality. The dataset captured in this space was also processed by both algorithms using identical software parameters. The goal of this comparison was to assess how each algorithm performs in a more controlled, enclosed space with varied object textures and lighting conditions.

In both cases, the same datasets were provided to each algorithm to ensure a fair and unbiased comparison.

2.4.2. Evaluation Criteria

The evaluation strategy follows a viewpoint-based assessment model. After generating the 3D reconstructions, we selected specific zones within each scene that represent high forensic relevance and technical challenge. This targeted analysis approach allows for focused evaluation on areas where accuracy, noise suppression, and detail fidelity are crucial.

Indoor Analysis Point

For the indoor scene, the analysis centered on a coffee table area located in the living room. This zone presents complex surface textures, varying illumination, and multiple occlusions, making it an ideal location to test the reconstruction performance of each algorithm.

Outdoor Analysis Point

In the outdoor scene, the primary analysis focused on the white car, specifically the region around the “Le Mans” text inscription on the upper left section of the vehicle. This detail presents subtle textural elements and curved surfaces, posing a challenge for radiance field rendering techniques.

Assessment Metrics

The comparison of NeRF and 3DGS was guided by three core metrics:

• Model Noise: Evaluated by the presence of visual artifacts or distortions in the final reconstruction.

• Detail Precision: Measured by the clarity and sharpness of textures and small features in the model.

• Computational Efficiency: Defined by the total time required for processing each dataset using the respective algorithm.

Each algorithm’s performance in these categories was rated on a 1–5 scale, showed in

Table 1, facilitating a structured comparison and visualization of results in tabular form. This scoring system allowed for both qualitative and semi-quantitative evaluation, aligning with the study’s forensic and applied orientation.

The entire experimental design was structured to reflect real-world constraints and priorities found in forensic and field-based 3D documentation tasks.

3. Results

This section presents the outcomes of the two experimental comparisons: one conducted in an outdoor environment and the other in an indoor environment. For both scenarios, identical video datasets were used to process 3D reconstructions with the NeRF and 3DGS algorithms. The performance was assessed using three criteria: model noise, detail precision, and computational efficiency. Ratings were assigned using a 1–5 scale, with 5 representing the best performance.

3.1. Comparison 1: Outdoor Environment

The first experiment focused on an outdoor scene consisting of a parking lot with varied elements such as asphalt, a streetlamp, three trees, patches of grass, and a white car—the central subject of the reconstruction. This environment presented challenges such as high lighting contrast, reflective surfaces, and a mix of natural and artificial objects.

Both NeRF and 3DGS successfully reconstructed the overall layout of the scene. The white car appeared well-defined in both reconstructions, with clear outlines and recognizable surface features. However, differences became apparent upon closer inspection.

The NeRF-based reconstruction demonstrated strong object continuity and colour realism, but several small visual artifacts were noticeable around the edges of the car and in lower-textured background areas, particularly where occlusions occurred. These artifacts slightly degraded the perceived smoothness and clarity of the model.

In contrast, the 3DGS reconstruction preserved a similar level of detail while introducing fewer visual distortions. Edges were cleaner, and transitions between different materials, such as the car’s surface and the surrounding asphalt, were more stable. Additionally, 3DGS completed the reconstruction approximately ten minutes faster than NeRF, making it more efficient from a computational perspective.

These observations are illustrated in

Figure 3, which shows side-by-side visual comparisons of the outdoor scene reconstructions. Quantitative results for processing time, noise level, and detail precision are summarized in

Table 2.

3.2. Comparison 2: Indoor Environment

The second experiment was conducted in a confined indoor space composed of a living room, kitchen, and hallway. The scene included diverse furniture items such as tables, chairs, closets, and various smaller objects like tableware. This environment introduced different challenges: complex textures, variable lighting conditions, reflective surfaces, and tighter geometry with multiple occlusions.

In this case, the 3DGS algorithm delivered a noticeably superior performance across all criteria. The reconstructed indoor scene using 3DGS exhibited smoother surfaces, better noise handling, and a higher level of visual sharpness. Details such as chair legs, lamp structures, and the texture of the floor were preserved more accurately. The overall appearance of the 3DGS model was more cohesive and realistic, making it suitable for close inspection and forensic evaluation.

NeRF also generated a usable 3D model, but it suffered from increased noise levels and some visual artifacts, particularly in areas with occlusion, low texture contrast, or reflective surfaces. These imperfections affected the clarity of furniture outlines and caused minor inconsistencies in the scene geometry.

In terms of processing time, 3DGS completed the reconstruction in just over 42 minutes, while NeRF required more than 74 minutes, reflecting a significant computational advantage for 3DGS in indoor scenarios.

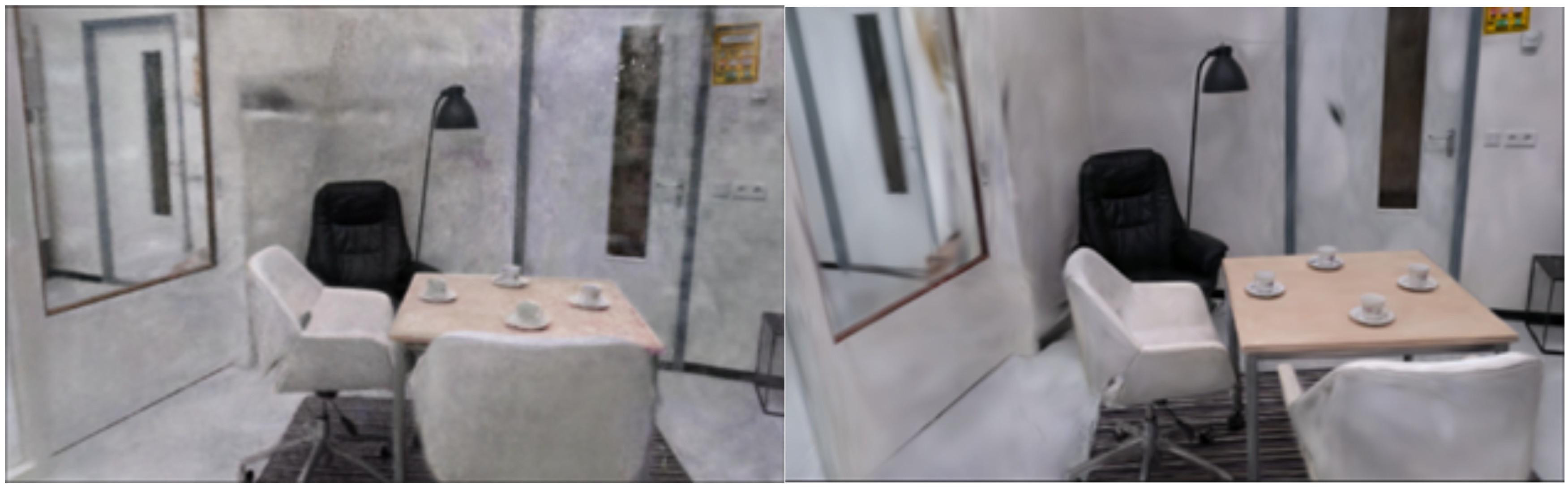

The visual comparison between the two models is shown in

Figure 4, and detailed performance metrics are listed in

Table 3.

These findings demonstrate that both NeRF and 3DGS are capable of producing realistic and structurally accurate reconstructions under optimal capture conditions. However, 3DGS consistently delivers equal or superior visual quality with reduced noise and significantly faster processing time, particularly in the complex and texture-rich indoor environment.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Results

The results of this study demonstrate distinct performance patterns between Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF) and 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS), shaped by the characteristics of the environments and the inherent strengths and limitations of each algorithm. The experimental design allowed for a consistent and controlled evaluation of both methods, leading to a series of insights into how each performs under varying real-world conditions.

Outdoor Environment: Comparable Detail, Different Stability

In the outdoor scene, both algorithms succeeded in generating highly detailed 3D reconstructions of the environment, particularly the focal object, a white car. The reconstructions displayed accurate geometry, strong contour alignment, and clear surface features. However, a subtle but meaningful distinction emerged in the stability and artifact levels of the models.

NeRF produced a visually realistic reconstruction with smooth transitions and nuanced colour rendering, thanks to its volumetric rendering framework. However, this came at the cost of localized noise, particularly along edges and in less-textured areas such as the sky, tree foliage, and asphalt surface. These visual artifacts, while not catastrophic, reduce the clarity and uniformity of the model and may complicate post-processing or analysis tasks, especially in forensic contexts where interpretability is critical.

3DGS, by contrast, matched NeRF in structural fidelity but surpassed it in visual stability. The reconstructed car, tree trunks, and streetlight edges were notably cleaner, with fewer distortions or noisy splats. This improved consistency is likely due to the explicit spatial representation of Gaussians and the more deterministic rendering process in 3DGS. Furthermore, the algorithm completed the reconstruction in approximately ten minutes, less than NeRF, providing a computational efficiency advantage without sacrificing model quality.

This outcome suggests that for open, well-lit scenes with moderate complexity, 3DGS can deliver results on par with NeRF while offering practical benefits in terms of processing speed and visual robustness.

Indoor Environment: 3DGS Outperforms NeRF Across the Board

The performance difference between the two algorithms became more pronounced in the indoor scenario. Indoor environments inherently introduce additional challenges for 3D reconstruction, including complex geometry, confined spaces, varied lighting conditions, and frequent occlusions. These factors significantly impact how reconstruction algorithms perform and often reveal weaknesses not visible in simpler settings.

In this context, 3DGS outperformed NeRF on all evaluation criteria. The resulting 3DGS model exhibited lower noise, higher detail preservation, and shorter processing time. Fine structures such as chair legs, table edges, and decorative items on surfaces were rendered with clarity and cohesion. Textural information, such as patterns on floors or furniture finishes, was maintained with minimal blurring or smoothing. Moreover, surfaces appeared smooth and well-connected, creating a more cohesive and interpretable spatial model.

NeRF, while still able to produce a recognizably accurate scene, introduced more visible artifacts, particularly in shadowed areas and regions with reflective surfaces such as countertops or metallic fixtures. These issues likely stem from NeRF's sensitivity to lighting inconsistencies and its reliance on implicit volumetric encoding, which can falter in low-contrast or high-occlusion regions. The training time for the NeRF model also significantly exceeded that of 3DGS by more than 30 minutes, further emphasizing its operational limitations in time-sensitive applications.

These observations underline that while NeRF remains a powerful tool for rendering photorealistic outputs, its practical usability in forensic or real-time scenarios may be limited by processing demands and stability under variable capture conditions. In contrast, 3DGS appears more robust to environmental complexity and provides a more predictable and efficient pipeline for indoor 3D reconstruction.

4.2. Comparison with Existing Literature

The findings of this study are broadly consistent with emerging research in the field of neural and point-based 3D reconstruction.

Recent literature has noted that NeRF excels in generating highly realistic renderings under ideal conditions but struggles with noisy or limited input data. Mildenhall et al. (2020) [

5], who introduced NeRF, focused primarily on small, controlled indoor scenes with static lighting and extensive input imagery. Later works [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23] have proposed improvements to speed and generalization but NeRF remains relatively computationally demanding and sensitive to inconsistencies in image quality or pose estimation.

By contrast, Gaussian Splatting has rapidly gained traction for its balance between speed and quality. According to Kerbl et al. (2023) [

12], 3DGS can produce photorealistic results with significantly faster training and inference times than NeRF, especially in scenarios requiring fast deployment or live feedback. This observation is reinforced by our findings, particularly in the indoor environment, where 3DGS processed the scene 30 minutes faster while also delivering smoother surfaces and less noise.

Additionally, our use of viewpoint-specific evaluation, inspired by recent forensic reconstruction literature [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30], supports a growing trend of aligning algorithm performance with real-world investigative needs. This aligns our work with recent calls to develop evaluation frameworks that prioritize interpretability, accuracy, and efficiency over synthetic metrics alone.

However, many prior studies have not examined the specific combination of indoor and outdoor real-world environments using the same capture setup. This gives our study a unique contribution by directly comparing algorithms under field-relevant conditions, using consistent hardware and evaluation strategies.

4.3. Practical Implications

The conclusions derived by this research provide significant implications for scientists and academics who use 3D reconstruction in practical applications, especially those dealing with time-sensitive or precision-based applications. In forensic inquiries, precision and interpretability are crucial, and 3D Gaussian Splatting's capability to generate clean, artifact-free reconstructions in less computing time is extremely beneficial. Spatial detail, clarity and minimized visual noise improve the reliability of 3D evidence for documentation purposes, analysis, and even presentation in court.

Outside of forensics, implications reach areas of cultural heritage conservation, architectural surveys, and robotics. For instance, in the digitization of historical locations, most notably interior environments, 3DGS presents an attractive solution for rendering high-fidelity environments without extensive data processing, which typically constrains field operations. Correspondingly, robotic applications demanding real-time or near-real-time understanding of space would be advantageous in using the increased rendering speed of 3DGS for faster navigating, localizing, or interpreting a scene. In contrast, NeRF's robust performance in rendering smooth surfaces and photorealism might still be useful in cinematic visual effects, educational simulation, or other use cases for which aesthetic fidelity takes precedence over computing constraints.

Finally, this comparative assessment enables practitioners to choose the best instrument for the particular needs of their field, whether for speed and strength, or for realism and visual richness. Placing the assessment under real-world conditions of filming and considering indoor and outdoor environments, the research offers practical and transferable knowledge for the broader community of 3D reconstruction.

4.4. Limitations

Although this research provides an organized and practical comparison of 3DGS to NeRF, some limitations need to be addressed to offer a suitable context for its implications. Specifically, experiments were performed using one particular camera rig, a SONY α7C, alongside the gimbal and the wide-angle Sigma lens, used in previous research within this ongoing research. Despite this being an optimized and reusable setup, its generality for other hardware configurations is yet to be tested. Various sensor types, lens focal lengths, or stabilization devices might possibly affect data quality and, in turn, the reconstruction algorithms' performance.

Furthermore, the research used recommended or default parameters for each of NeRF and 3DGS as used in Postshot's software setup. Although this facilitates fairness and ease of reproduction, it does imply that additional gains in performance can be achieved using advanced tuning and tailored pipeline adjustments, something that remains unexplored within this comparison.

One further consideration is limited scene diversity. One scene indoors and one outdoors were analyzed, each designed to represent common forensic or practical reconstruction environments. However, this scope excludes more dynamic or adverse conditions such as nighttime scenes, rapidly changing lighting, or environments with moving objects. A diverse set of test environments would be necessary to adequately test algorithmic robustness and flexibility.

Finally, while the assessment process utilized a scaled 1–5 rating system for critical criteria, still, an element of subjective interpretation was still used in qualitative determination of noise and detail retention. While efforts were made to standardize scoring and focus on relevant viewpoints, more objective, ground-truth-based metrics could enhance future evaluations by providing quantifiable and reproducible benchmarks.

4.5. Future Work

Expanding upon the results and constraints of this research, several promising directions for future work become apparent. A natural next step is to increase the diversity of environments within the experimental setup, both in terms of size and complexity. Adding environments with low light, specular surfaces, dynamic objects, or repetitive geometries would challenge the algorithms further and expose further nuances in performance in ways not yet tested.

It would also be useful to investigate how domain-specific operators, such as forensic investigators, cultural heritage conservators, or drone pilots, use and make sense of each reconstruction. Conducting user studies focused on practical usability, clarity, and decision-making support could reveal which algorithmic characteristics matter most in real-world deployments.

Finally, further investigation into hybrid workflows or optimization strategies could prove fruitful. For instance, developing preprocessing methods that improve input quality for NeRF or integrating semantic segmentation into the 3DGS pipeline could enhance reconstruction accuracy and context-awareness. Such developments would support the growing need for fast, robust, and interpretable 3D models across a wide range of disciplines.

5. Conclusions

This paper presented a systematic and methodologically grounded comparison between Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF) and 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS), two cutting-edge approaches for generating photorealistic 3D reconstructions from captured imagery. By evaluating both algorithms under identical conditions, using the same full-frame camera setup, consistent filming techniques, and controlled indoor and outdoor environments—this study provides a balanced, application-oriented perspective on the strengths and limitations of each method.

The findings demonstrate that while NeRF remains a powerful tool for producing high-quality reconstructions, it is limited by its computational demands and its sensitivity to challenging lighting and occlusion conditions, particularly indoors. In contrast, 3DGS offers a more efficient and robust alternative, delivering reconstructions of comparable or superior visual quality with significantly reduced processing times and fewer visual artifacts. These advantages are especially relevant for time-critical and precision-driven domains such as forensic investigation, security documentation, and indoor spatial analysis.

Importantly, this study contributes to a growing body of applied 3D reconstruction research by not only benchmarking performance but by doing so within a realistic data capture framework grounded in prior experimental validation. It bridges the gap between technical algorithm development and real-world operational deployment, offering concrete guidance for practitioners seeking effective, scalable solutions.

Nonetheless, the study also highlights the importance of context: no single algorithm universally outperforms the other across all scenarios. The decision to use NeRF or 3DGS should be informed by the specific needs of the application, whether it is reconstruction speed, visual interpretability, model sharpness, or computational constraints.

As part of a continuous research line, this paper sets the stage for future exploration into more complex environments, automated evaluation metrics, and user-centered design studies. By expanding the scope of tested scenarios and integrating feedback from domain experts, future work will further refine our understanding of how 3D reconstruction technologies can best serve practical, high impact use cases.

In conclusion, 3D Gaussian Splatting emerges as a highly promising method for efficient and reliable 3D reconstruction under varied filming techniques, offering strong potential for adoption in applied fields where performance, speed, and accuracy must coexist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.W., S.W., E.G., R.M., M.v.K. and D.R.; methodology, D.R.; software, E.G., K.W., S.W. and D.R.; validation, E.G., K.W., S.W. and D.R.; formal analysis, D.R.; investigation, K.W., S.W. and D.R.; resources, D.R. and R.M.; data curation, D.R.; writing—original draft preparation, D.R.; writing—review and editing D.R., M.v.K. and R.M.; visualization, E.G., K.W. and S.W.; supervision, M.v.K. and R.M.; project administration, D.R.; funding acquisition, D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received financial support from the University of Twente and research group Technologies for Criminal Investigations, part of Saxion University for Applied Sciences and the Police Academy of the Netherlands. Also, this research is part of the project “Regiodeal Stedendriehoek” funded by the Dutch National Government and “Stichting Saxion - Zwaartepunt Veiligheid & Digitalisering” funded by Saxion University of Applied Sciences.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

Special gratitude to the University of Twente in the Netherlands, Technology for Criminal Investigations research group part of Saxion University of Applied Sciences and the Police Academy in the Netherlands, the Technical University of Sofia and AI & CAD Systems Lab in Sofia Tech Park in Bulgaria and all researchers in the CrimeBots research line part of research group TCI. Also, thanks for the dedicated opportunity and funding from Saxion University of Applied Sciences.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- E. M. Robinson, “Photogrammetry,” Crime Scene Photography: Third Edition, pp. 411–453, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Houck, F. M. M. Houck, F. Crispino, and T. McAdam, “Photogrammetry and 3D Reconstruction,” The Science of Crime Scenes, pp. 361–377, Jan. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I. Kalisperakis, L. Grammatikopoulos, E. Petsa, and G. Karras, “A Structured-Light Approach for the Reconstruction of Complex Objects,” Geoinformatics FCE CTU, vol. 6, pp. 259–266, Dec. 2011, doi: 10.14311/GI.6.32.

- Y. Feng, R. Wu, X. Liu, and L. Chen, “Three-Dimensional Reconstruction Based on Multiple Views of Structured Light Projectors and Point Cloud Registration Noise Removal for Fusion,” Sensors 2023, Vol. 23, Page 8675, vol. 23, no. 21, p. 8675, Oct. 2023, doi: 10.3390/S23218675.

- B. Mildenhall, P. P. Srinivasan, M. Tancik, J. T. Barron, R. Ramamoorthi, and R. Ng, “NeRF: Representing Scenes as Neural Radiance Fields for View Synthesis,” Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), vol. 12346 LNCS, pp. 405–421, Mar. 2020, doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-58452-8_24.

- T. Nguyen-Phuoc, F. Liu, and L. Xiao, “SNeRF: Stylized Neural Implicit Representations for 3D Scenes,” ACM Trans Graph, vol. 41, no. 4, p. 11, Jul. 2022, doi: 10.1145/3528223.3530107.

- J. Kulhanek and T. Sattler, “Tetra-NeRF: Representing Neural Radiance Fields Using Tetrahedra,” 2023, Accessed: Jul. 15, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/jkulhanek/tetra-nerf.

- M. Tancik et al., “Nerfstudio: A Modular Framework for Neural Radiance Field Development,” Pro-ceedings - SIGGRAPH 2023 Conference Papers, Feb. 2023, doi: 10.1145/3588432.3591516.

- T. Müller, S. Nvidia, A. Evans, C. Schied, and A. 2022 Keller, “Instant Neural Graphics Primitives with a Multiresolution Hash Encoding,” ACM Trans. Graph, vol. 41, no. 4, p. 102, 2022, doi: 10.1145/3528223.3530127.

- R. Liang, J. Zhang, H. Li, C. Yang, Y. Guan, and N. Vijaykumar, “SPIDR: SDF-based Neural Point Fields for Illumination and Deformation,” Oct. 2022, Accessed: Jul. 15, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2210.08398v3.

- C. Reiser et al., “MERF: Memory-Efficient Radiance Fields for Real-time View Synthesis in Unbounded Scenes,” ACM Trans Graph, vol. 42, no. 4, Feb. 2023, doi: 10.1145/3592426.

- B. Kerbl, G. Kopanas, T. Leimkuehler, and G. Drettakis, “3D Gaussian Splatting for Real-Time Radiance Field Rendering,” ACM Trans Graph, vol. 42, no. 4, p. 14, Aug. 2023, doi: 10.1145/3592433.

- G. Chen and W. Wang, “A Survey on 3D Gaussian Splatting,” Jan. 2024, Accessed: Mar. 31, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.03890v6.

- D. Rangelov, S. Waanders, K. Waanders, M. van Keulen, and R. Miltchev, “Impact of Data Capture Methods on 3D Reconstruction with Gaussian Splatting,” Journal of Imaging 2025, Vol. 11, Page 65, vol. 11, no. 2, p. 65, Feb. 2025, doi: 10.3390/JIMAGING11020065.

- D. Rangelov, S. Waanders, K. Waanders, M. van Keulen, and R. Miltchev, “Impact of Camera Settings on 3D Reconstruction Quality: Insights from NeRF and Gaussian Splatting,” Sensors 2024, Vol. 24, Page 7594, vol. 24, no. 23, p. 7594, Nov. 2024, doi: 10.3390/S24237594.

- Sony, “Sony Alpha 7C Full-Frame Mirrorless Camera - Black| ILCE7C.” Accessed: Dec. 22, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://electronics.sony.com/imaging/interchangeable-lens-cameras/all-interchangeable-lens-cameras/p/ilce7c-b?srsltid=AfmBOoo5N6vG9O3tR3d9p7ZKy9YqWMPZSzdnQnfZjfl4XP9WE2vRx1bz.

- Sigma, “14mm F1.4 DG DN | Art | Lenses | SIGMA Corporation.” Accessed: Dec. 22, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.sigma-global.com/en/lenses/a023_14_14.

- Jawset, “Jawset Postshot.” Accessed: Dec. 22, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.jawset.com/.

- W. Bian, Z. Wang, K. Li, J. W. Bian, and V. A. Prisacariu, “NoPe-NeRF: Optimising Neural Radiance Field with No Pose Prior,” Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, vol. 2023-June, pp. 4160–4169, Dec. 2022, doi: 10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.00405.

- Y. Xia, H. Tang, R. Timofte, and L. Van Gool, “SiNeRF: Sinusoidal Neural Radiance Fields for Joint Pose Estimation and Scene Reconstruction,” BMVC 2022 - 33rd British Machine Vision Conference Proceedings, Oct. 2022, Accessed: Apr. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2210.04553v1.

- S. J. Garbin, M. Kowalski, M. Johnson, J. Shotton, and J. Valentin, “FastNeRF: High-Fidelity Neural Rendering at 200FPS,” Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, pp. 14326–14335, Mar. 2021, doi: 10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.01408.

- W. Xiao et al., “Neural Radiance Fields for the Real World: A Survey,” Jan. 2025, Accessed: Apr. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2501.13104.

- J. T. Barron, B. Mildenhall, D. Verbin, P. P. Srinivasan, and P. Hedman, “Mip-NeRF 360: Unbounded Anti-Aliased Neural Radiance Fields,” Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Com-puter Vision and Pattern Recognition, vol. 2022-June, pp. 5460–5469, Nov. 2021, doi: 10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.00539.

- A. Amamra, Y. Amara, K. Boumaza, and A. Benayad, “Crime scene reconstruction with RGB-D sensors,” in Proceedings of the 2019 Federated Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems, FedCSIS 2019, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., Sep. 2019, pp. 391–396. doi: 10.15439/2019F225.

- G. Galanakis et al., “A Study of 3D Digitisation Modalities for Crime Scene Investigation,” Forensic Sci-ences 2021, Vol. 1, Pages 56-85, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 56–85, Jul. 2021, doi: 10.3390/FORENSICSCI1020008.

- A. N. Sazaly, M. F. M. Ariff, and A. F. Razali, “3D Indoor Crime Scene Reconstruction from Micro UAV Photogrammetry Technique,” Engineering, Technology & Applied Science Research, vol. 13, no. 6, pp. 12020–12025, Dec. 2023, doi: 10.48084/ETASR.6260.

- C. Villa, N. Lynnerup, and C. Jacobsen, “A Virtual, 3D Multimodal Approach to Victim and Crime Scene Reconstruction,” Diagnostics 2023, Vol. 13, Page 2764, vol. 13, no. 17, p. 2764, Aug. 2023, doi: 10.3390/DIAGNOSTICS13172764.

- M. A. Maneli and O. E. Isafiade, “3D Forensic Crime Scene Reconstruction Involving Immersive Tech-nology: A Systematic Literature Review,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 88821–88857, 2022, doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3199437.

- S. Kottner, M. J. Thali, and D. Gascho, “Using the iPhone’s LiDAR technology to capture 3D forensic data at crime and crash scenes,” Forensic Imaging, vol. 32, p. 200535, Mar. 2023, doi: 10.1016/J.FRI.2023.200535.

- M. M. Houck, F. Crispino, and T. McAdam, “Photogrammetry and 3D Reconstruction,” The Science of Crime Scenes, pp. 361–377, Jan.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).