1. Introduction

1.1. HIV

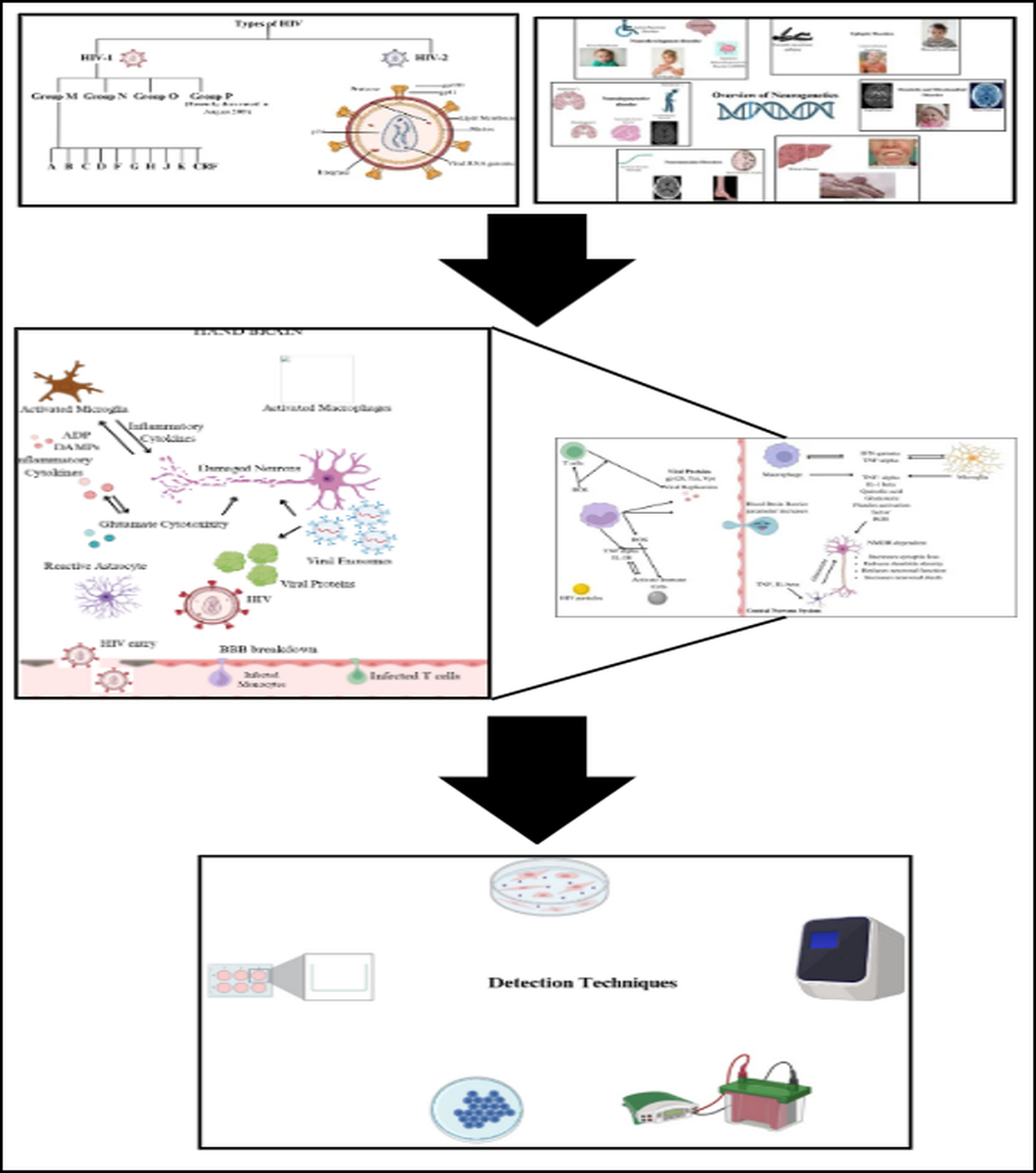

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) primarily targets CD4 cells, essential for immune defense, and can progress to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) if untreated. HIV, a retrovirus, has a complex structure with a lipid bilayer derived from host cell membranes, embedding glycoproteins such as gp120, which binds to CD4 receptors, and gp41, facilitating fusion with host cells. Beneath this envelope is the matrix protein p17, crucial for virion integrity, while the cone-shaped capsid, composed of p24, encases the viral RNA and enzymes. HIV encodes nine genes across its two RNA strands, with key enzymes including reverse transcriptase, converting RNA to DNA, and protease, which processes polyproteins. HIV-1, the more widespread strain causing global pandemics, has main group M and rarer groups N and O, while HIV-2, less transmissible and primarily found in West Africa, progresses more slowly [

1,

2]. HIV-1 group M is responsible for the global pandemic and is subdivided into subtypes (clades) A, B, C, D, F, G, H, J, K, and various Circulating Recombinant Forms (CRFs). Subtype distribution varies geographically. For instance, subtype B predominates in Europe and the Americas, while subtype C is most common in Southern Africa and India. Recombinant forms arise when an individual is co-infected with multiple subtypes, leading to genetic recombination. These strains differ significantly in genetic diversity, transmission rates, and disease progression. The diagrammatical presentation of different types of HIV is shown in

Figure 1.

HIV's reverse transcriptase enzyme lacks proofreading ability, resulting in a high mutation rate during replication. This contributes to the rapid evolution of the virus and the emergence of diverse quasispecies within an infected individual. During reverse transcription, the nascent DNA can switch between the two RNA genomes packaged in a single virion, a "copy-choice" recombination process. This mechanism further increases genetic diversity. The host's immune response and antiretroviral therapies exert selection pressures on HIV, leading to the survival of resistant variants. This dynamic results in a complex, ever-evolving population of viral quasispecies within the host. [

3,

4]

Considering the impact of HIV on the central nervous system (CNS), it was reported to focus on HIV-associated dementia (HAD), a severe neurocognitive disorder seen in the advanced disease stage of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND), which represents a spectrum of cognitive impairments in people living with HIV. HAND includes three clinical categories:

asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment (ANI), mild neurocognitive disorder (MND), and HAD. While HAD been more common in the pre-antiretroviral therapy (ART) era, its incidence has significantly declined with widespread ART use. However, milder forms of HAND (ANI and MND) remain prevalent, affecting up to 50% of individuals with HIV. Despite effective viral suppression, HAND persists due to chronic neuroinflammation, neurotoxicity from viral proteins, and ongoing immune activation within the central nervous system. As antiretroviral therapy (ART) improved survival, researchers identified milder forms of cognitive impairment, prompting deeper investigations into viral reservoirs, neuroinflammation, and immune activation [

5].

Modern molecular studies have revealed mechanisms such as viral proteins (e.g., Tat, gp120) disrupting neuronal function, chronic neuroinflammation driven by monocyte infiltration, and altered synaptic signalling. Neuroimaging and biomarker research advances continue to refine our understanding, highlighting persistent low-level CNS inflammation even in virally suppressed individuals [

6].

1.2. HIV and Neurogenetics

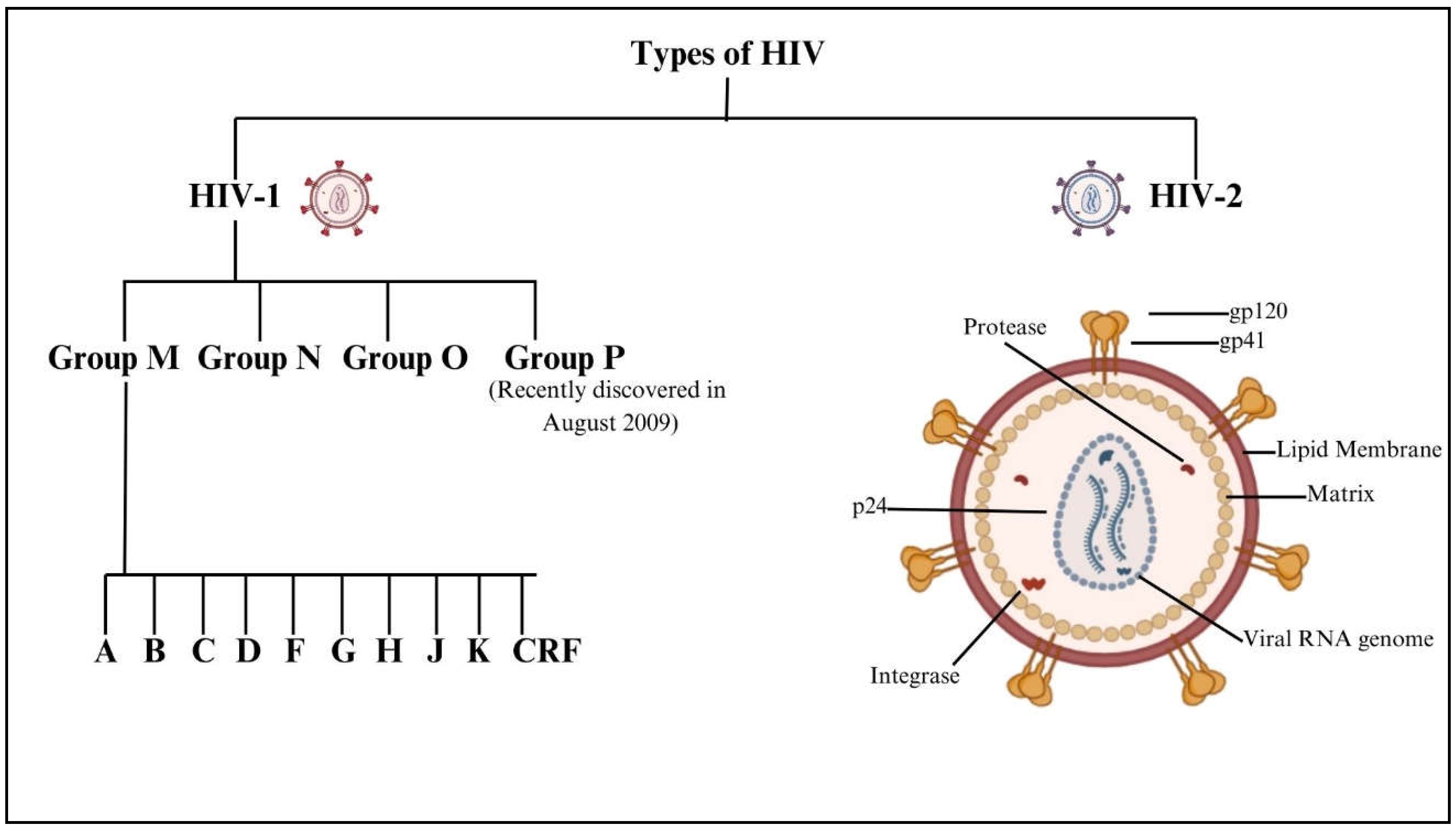

The subfield of genetics, known as "neurogenetics" studies, focuses on the hereditary causes of neurological disorders as well as the effects of genes on the maturation and operation of the nervous system. It explores how brain health is affected by inherited genetic variables and mutations that occur after conception [

7,

8]. Considering the therapeutic approach, the current antiretroviral therapy (ART) has significantly reduced the incidence of severe HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND). However, milder forms of HAND remain prevalent, partly due to challenges in achieving effective ART concentrations within the central nervous system (CNS). The blood-brain barrier (BBB) restricts the entry of many antiretroviral drugs, leading to suboptimal viral suppression in the CNS. This limited penetration allows HIV to persist in the brain, contributing to ongoing neuroinflammation and cognitive impairment [

9]. Researchers have developed the CNS penetration-effectiveness (CPE) score to address this issue, which ranks ART drugs based on their ability to penetrate the CNS. Higher CPE scores are associated with better viral suppression in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and improved neurocognitive outcomes. However, some studies have not consistently confirmed these benefits, indicating that factors beyond drug penetration, such as individual patient characteristics and the presence of drug-resistant HIV strains in the CNS, may influence treatment efficacy [

10]. Drug resistance within the CNS poses another significant challenge. The CNS can serve as a reservoir for HIV, where the virus may evolve independently from peripheral compartments. This compartmentalization can lead to the development of drug-resistant variants that are not detected in standard blood tests, complicating treatment strategies. Cases of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) viral escape, where HIV replication persists in the CNS despite effective peripheral viral suppression, have been documented. These cases often involve drug-resistant HIV strains, underscoring the need for tailored ART regimens that effectively target CNS reservoirs [

11].

Although ART has transformed HIV into a manageable chronic condition, challenges remain in preventing and treating HAND. Improving the CNS penetration of ART, monitoring for CNS-specific drug resistance, and developing therapies that can effectively cross the BBB are critical steps toward optimizing neurocognitive outcomes for individuals living with HIV. Significant areas of attention include the identification of genes associated with neurodevelopmental disorders, autism spectrum disorders, epilepsy, Parkinson's disease, and Alzheimer's disease; this will provide light on the causes of these diseases, including evaluation of risk and possible treatments [

12]. By studying the molecular mechanisms behind processes like neurogenesis and synaptogenesis, neurodevelopmental genetics seeks to understand the impact of genetic differences on the maturation of the nervous system from the embryonic stage into adulthood [

13,

14]. Crucial in genetic testing and diagnosis, it employs cutting-edge genomic technologies like next-generation sequencing to identify mutations in complicated neurological disorders, allowing targeted treatments. Precision medicine aims to improve therapeutic results while minimizing side effects by customizing therapies according to individual genetic profiles [

15]. The field of neurogenetics also investigates novel approaches to treating genetic disorders, such as gene therapy and CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. Animal models, bioinformatics, and methods for evaluating genomic data, such as whole exome sequencing and genome-wide association studies, are essential [

16]. The future of this discipline holds great promise for more accurate diagnoses and tailored therapies, which might completely transform people with neurological diseases are cared for [

17,

18,

19]. The overview of neurogenetics is shown in

Figure 2.

1.3. HAND

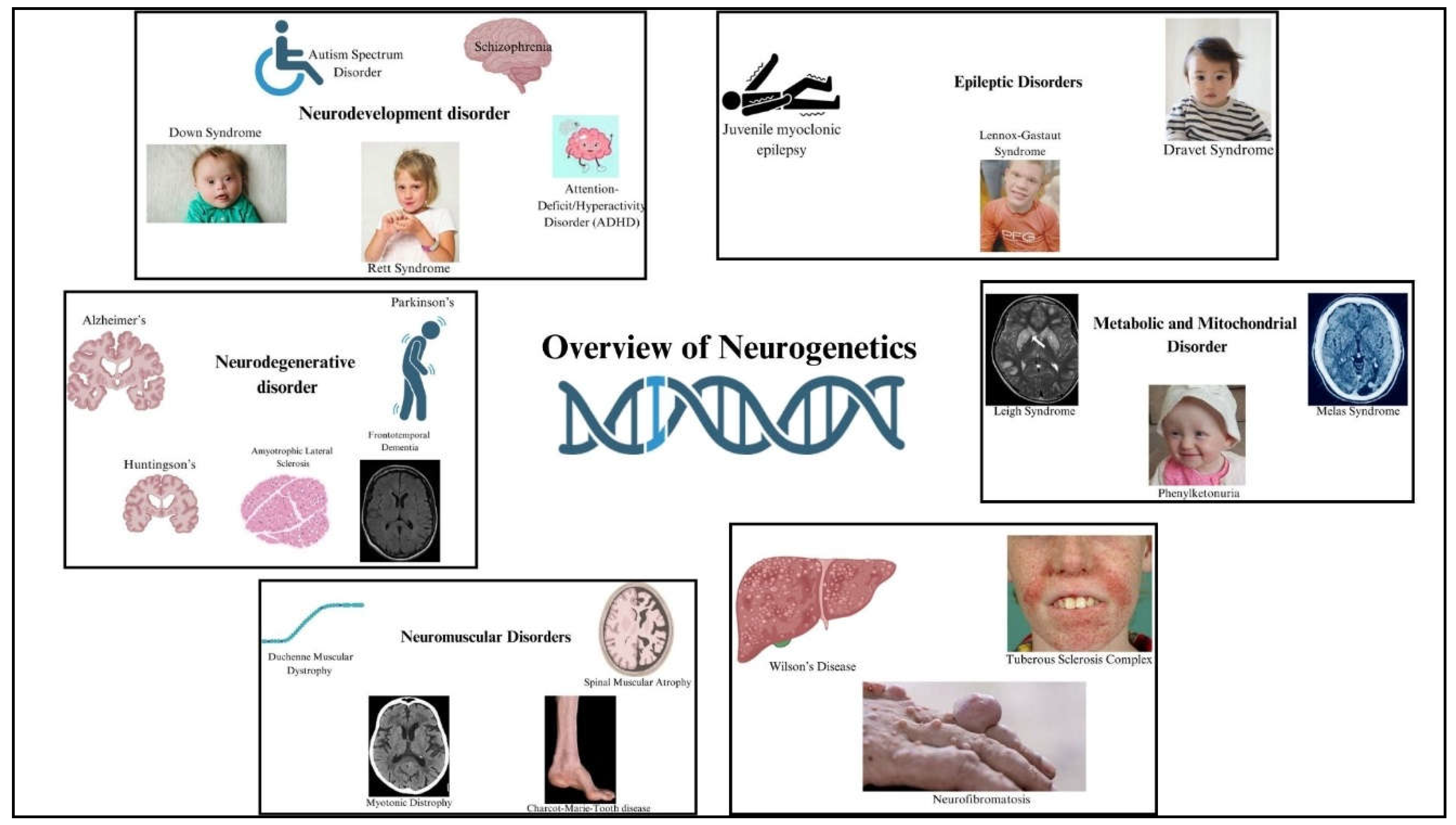

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) encompass a range of cognitive, motor, and behavioral impairments that arise as complications of HIV infection, varying from mild cognitive deficits to severe dementia. These conditions significantly impact daily life and quality of life for affected individuals. HAND includes asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment (ANI), mild neurocognitive disorder (MND), and HIV-associated dementia (HAD). Pathophysiologically, HIV enters the central nervous system early in infection, infecting microglia and macrophages, leading to neuroinflammation and neuronal dysfunction through viral toxicity and neurotransmitter disruption [

20]. Clinical manifestations include cognitive deficits in attention, memory, and executive function, alongside behavioral changes like mood disorders and motor impairments. Diagnosis involves comprehensive neuropsychological assessments, clinical evaluations, and sometimes neuroimaging. Management strategies include early and adherent antiretroviral therapy (ART) to reduce viral load and inflammation and symptomatic treatments such as cognitive rehabilitation and psychiatric interventions [

21]. Ongoing research aims to understand HAND mechanisms better, develop targeted therapies, and improve diagnostic and monitoring tools to enhance outcomes and support for those living with HAND [

22,

23]. The difference between a healthy brain and a HAND brain is shown in

Figure 3.

2. Neuropathogenesis

2.1. Impact of HIV on Neurogenetics

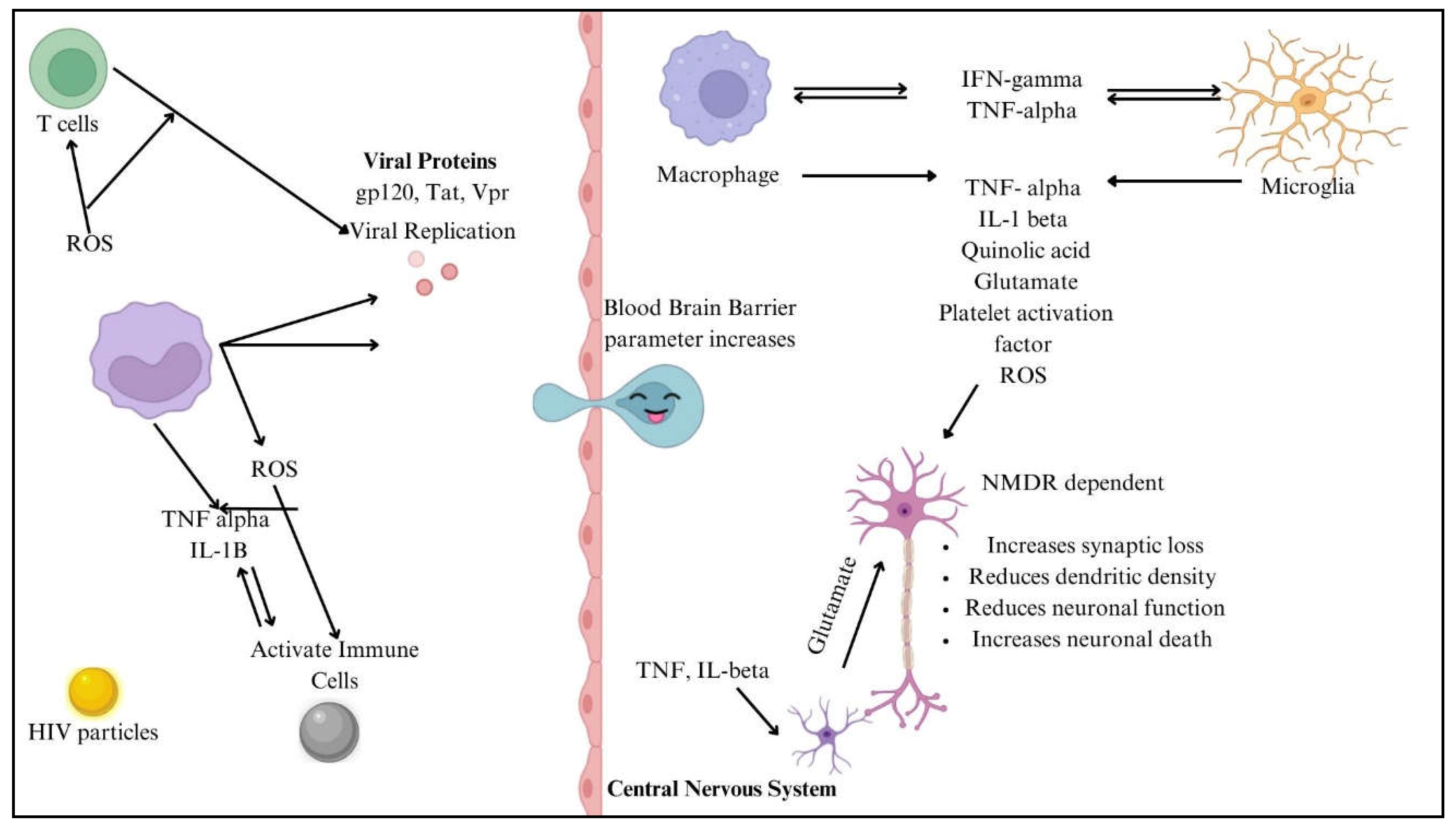

The numerous processes by which HIV penetrates the central nervous system (CNS) include both direct and indirect channels. In most cases, access to the central nervous system is limited by the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which consists of endothelial cells, pericytes, and astrocytic end feet. In contrast, inflammatory reactions and chemokine-mediated signalling allow HIV-infected immune cells, such as monocytes/macrophages and CD4+ T cells, to penetrate the BBB. Once within the central nervous system, HIV uses this sly tactic to set up shop in perivascular macrophages and microglia [

24]. Gp120 and Tat are viral proteins that indirectly worsen neuronal damage by interfering with glutamatergic and dopaminergic pathways, which in turn cause neurocognitive disorders and cognitive deficiencies. Systemic inflammation maintains neurotoxicity and oxidative stress, and microglial activation and astrocyte dysfunction cause neuroinflammation, exacerbating this damage [

25]. HIV-1 proteins gp120 and Tat contribute to neurotoxicity and neuroinflammation, playing key roles in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND). gp120 binds to CXCR4/CCR5 receptors, inducing neuronal apoptosis, excitotoxicity, and blood-brain barrier (BBB) dysfunction while also activating astrocytes and microglia to release pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6). Tat exacerbates neurodegeneration by disrupting BDNF signalling, mitochondrial function, and glutamate uptake, leading to excessive excitotoxicity. Both proteins promote chronic inflammation via NF-κB activation and enhance neurotoxicity when combined with drug abuse or co-infections. These mechanisms drive synaptic damage, cognitive decline, and neurodegeneration, even in ART-treated individuals [

26,

27]. Genetic variables, such as CCR5 mutations and HLA alleles, impact neurocognitive effects and vulnerability to HIV infection. Gene expression related to neuroinflammation and neuronal survival is regulated by epigenetic alterations, which include changes in DNA methylation and histone acetylation. To better control antiretroviral treatment and reduce the risk of neurologic problems, it is essential to understand the underlying processes at work [

24]. The neuropathogenesis of HIV to CNS is shown in

Figure 4.

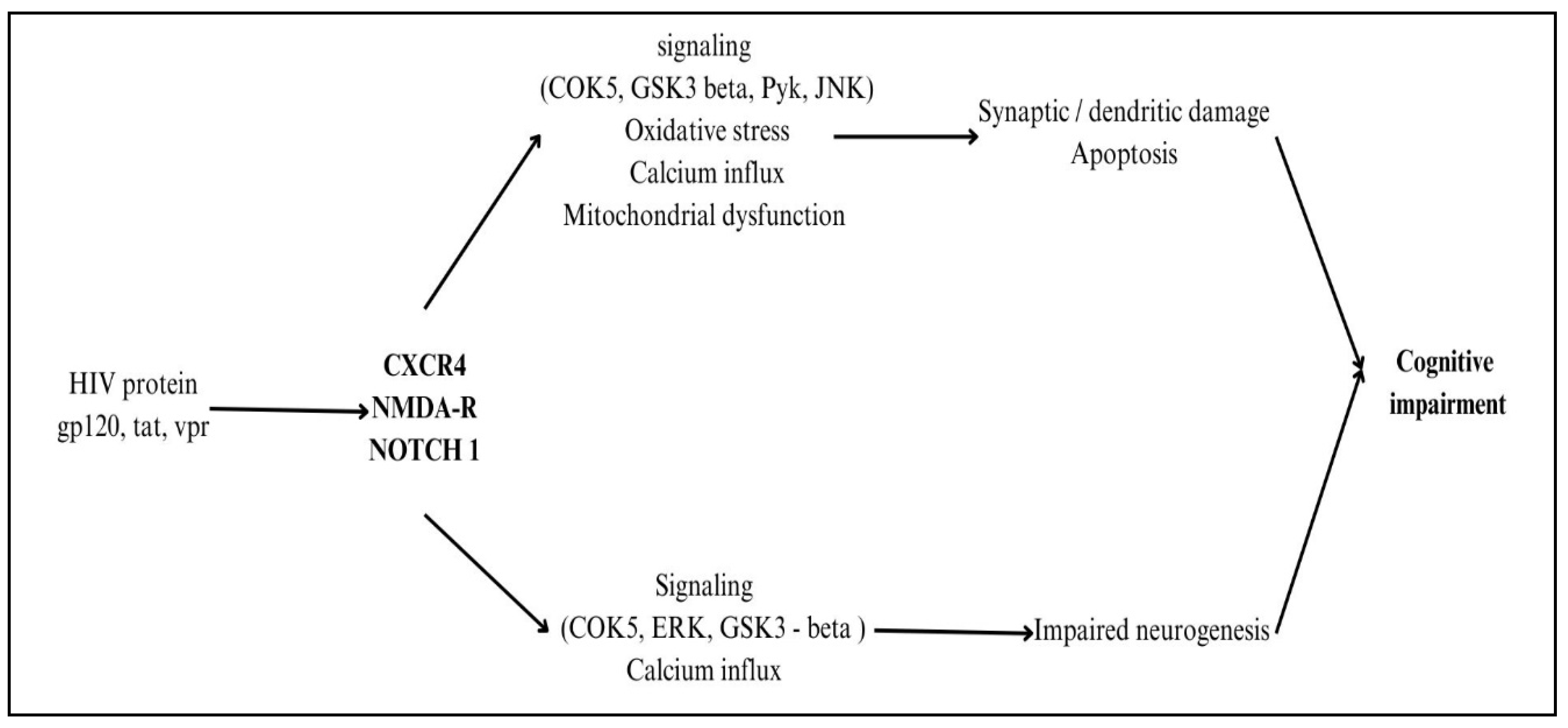

2.2. Impact of Proteins of HIV on Neurogenetics

Multiple viral proteins directly affect neurons when HIV reaches the CNS, leading to neurotoxicity. When gp120 binds to CD4 receptors on neurons, it sets off a cascade of events that includes microglia and astrocyte activation, oxidative stress due to the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and excitotoxicity caused by overactivation of NMDA receptors [

28]. HIV-1 Nef protein also plays a significant role in neuroinflammation by promoting microglial activation, astrocyte dysfunction, and immune cell infiltration into the CNS. Nef disrupts the blood-brain barrier (BBB), facilitating the entry of infected monocytes and amplifying neuroinflammation. It induces the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, leading to chronic neurotoxicity. Additionally, Nef promotes oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in neurons, contributing to synaptic damage and neuronal apoptosis. By activating NF-κB and MAPK signalling pathways, Nef sustains neuroinflammatory responses, exacerbating HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) and neuronal dysfunction, even in ART-treated individuals [

29]. The HIV replication-essential protein Tat infiltrates neurons and interferes with mitochondrial function, which in turn causes neuroinflammation by triggering the production of cytokines, poor energy metabolism, and death via activation of the apoptotic pathway [

30]. Neurotoxicity is worsened when Vpr, a viral replication factor, infects neurons and triggers cell cycle arrest, DNA damage, and pro-inflammatory responses. Because of their central roles in HIV-related neurocognitive disorders (HAND), inflammatory processes, and neuronal health, gp120, Tat, and Vpr need specific treatment strategies to reduce central nervous system (CNS) difficulties in HIV-infected individuals [

31,

32]. The proteins involved in the process of neuropathogenesis are shown in

Figure 5.

2.3. Host Genes Along with HIV Affecting Neurons

Host genes interact with HIV proteins to exacerbate neuroinflammation and neuronal damage in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND). CCR5 and CXCR4, key co-receptors for HIV entry, facilitate viral invasion into the CNS and trigger inflammatory signalling cascades. TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, upregulated in response to HIV proteins (gp120, Tat, and Nef), promote chronic neuroinflammation and neurotoxicity. NF-κB and MAPK pathways, activated by both HIV and host immune responses, enhance the production of inflammatory mediators, contributing to neuronal apoptosis and synaptic dysfunction [

29]. Additionally, BDNF and CREB signalling, critical for neuronal survival and plasticity, are disrupted by HIV, leading to cognitive impairments. Genetic variations in MCP-1 (CCL2) and APOE have been linked to increased neuroinflammatory responses and a higher risk of HAND. These interactions create a vicious cycle of inflammation, oxidative stress, and excitotoxicity, driving progressive neuronal damage even in individuals receiving ART [

33].

Particularly in neurogenetics and central nervous system functioning, chemokine receptors are very vital in HIV infection. HIV uses gp120 to connect to CCR5 or CXCR4 co-receptors and CD4 receptors, so invading cells mainly employing CCR5, R5-tropic HIV strains target macrophages and microglia, hence influencing neuroinflammation and neuronal damage. They also cause the first central nervous system invasion and primary infection. Variations in CCR5, especially the beneficial CCR5 Delta32 mutation, influence receptor function and might reduce the risk of HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment. HIV damages neurons and reduces cognitive ability by infecting the central nervous system CCR5-expressing microglia and macrophages, generating inflammatory mediators [

34]. Investigated for their capacity to block viral entry and lower neuroinflammation, maraviroc and other CCR5 antagonists help to enable tailored treatment based on genetic testing. Research is in progress to clarify the roles of chemokine receptors in HIV neuropathogenesis, their impact on neuronal gene expression and functioning, and to develop creative treatments meant to protect neurons and enhance neurocognitive outcomes in HIV-infected patients [

35,

36].

Host genetic variables influence the interaction between HIV and neurogenetics. HLA alleles determine the transport of viral antigens to T cells; HLA-B57 and HLA-B27 are linked with less disease progression and less neurological sequelae in HIV patients [

37,

38]. The CCR5 Delta32 mutation reduces the CCR5 receptor required for cellular entrance, rendering resistance to CCR5-tropic strains and highlighting the effect of genetic variants on susceptibility to HIV-related neurogenetic disorders [

39]. Genetic polymorphisms in immune response genes, like cytokines and chemokines, may increase immune activation and neuroinflammation, aggravating brain injury and cognitive impairment. Genetic susceptibility is vital in neurons as certain genetic variants in neuronal genes linked to survival and neurotransmission might cause neurocognitive impairments in HIV infection. Host genes and epigenetic changes, including DNA methylation and histone acetylation, may influence gene expression in response to HIV. Further, it can cause neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial malfunction resulting in neurocognitive impairment [

40]. Developing focused medications and treatments meant to reduce neurological problems in HIV-positive individuals depends on an understanding of these genetic and epigenetic mechanisms. Under HIV-associated neurocognitive diseases (HAND), neurodegeneration results from neuronal death. Neuronal loss in regions important for motor and cognitive abilities might cause functional disability and cognitive decline [

32,

39].

Usually occurring at CpG dinucleotides, DNA methylation is the process by which DNA methyltransferase enzymes (DNMTs) add methyl groups to DNA. Through changes in chromatin shape and transcription factor accessibility, this epigenetic process affects gene expression. Within the framework of HIV and neurogenetics, HIV infection may cause changes in DNA methylation patterns in immune cells and central nervous system tissues [

41,

42]. At certain genomic locations, inflammatory cytokines and viral proteins such as Tat and gp120 might cause hypermethylation or hypomethylation. These changes either activate inflammatory pathways or repress important genes, influencing neuronal genes linked with survival, inflammation, and death [

43]. Gene control via chromatin accessibility depends on histone modifications, including acetylation and methylation. HIV proteins interact with enzymes, including histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone methyltransferases (HMTs), therefore affecting histone modification patterns that control immune response genes and neuronal survival [

44]. By generating a pro-inflammatory milieu in the central nervous system, HIV's disturbance of histone alterations may aggravate neuronal malfunction and neurocognitive loss. Targeting histone-modulating enzymes to restore normal gene expression patterns and lower neuroinflammation might open therapeutic doors to help with HIV-associated neurological problems [

25,

45].

By invading neurons, the HIV Tat protein reduces mitochondrial activity, lowering membrane potential, raising reactive oxygen species production, and slowing ATP synthesis. This causes mitochondrial oxidative stress and DNA damage and activates death-causing pathways inside neurons, producing neuronal death. Dependent on mitochondrial ATP generation for energy, neurons have lowered ATP levels resulting from HIV-induced mitochondrial dysfunction, limiting their survival and usefulness [

46]. Mitochondrial failure aggravates neuroinflammation and neuronal damage by controlling oxidative stress and inflammation. Genetic differences in mitochondrial genes, particularly those about antioxidant defense like SOD2 or the preservation of mitochondrial DNA integrity, might influence sensitivity to HIV-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and accompanying neurological consequences. Antioxidants or stimulators of mitochondrial biogenesis are two possible treatment approaches aiming at mitochondrial activity that show great potential to reduce neuronal damage in HIV-infected people. Moreover, genetic screening of mitochondrial genes may make people prone to mitochondrial malfunction, guiding individualized treatment plans to protect neural function [

47].

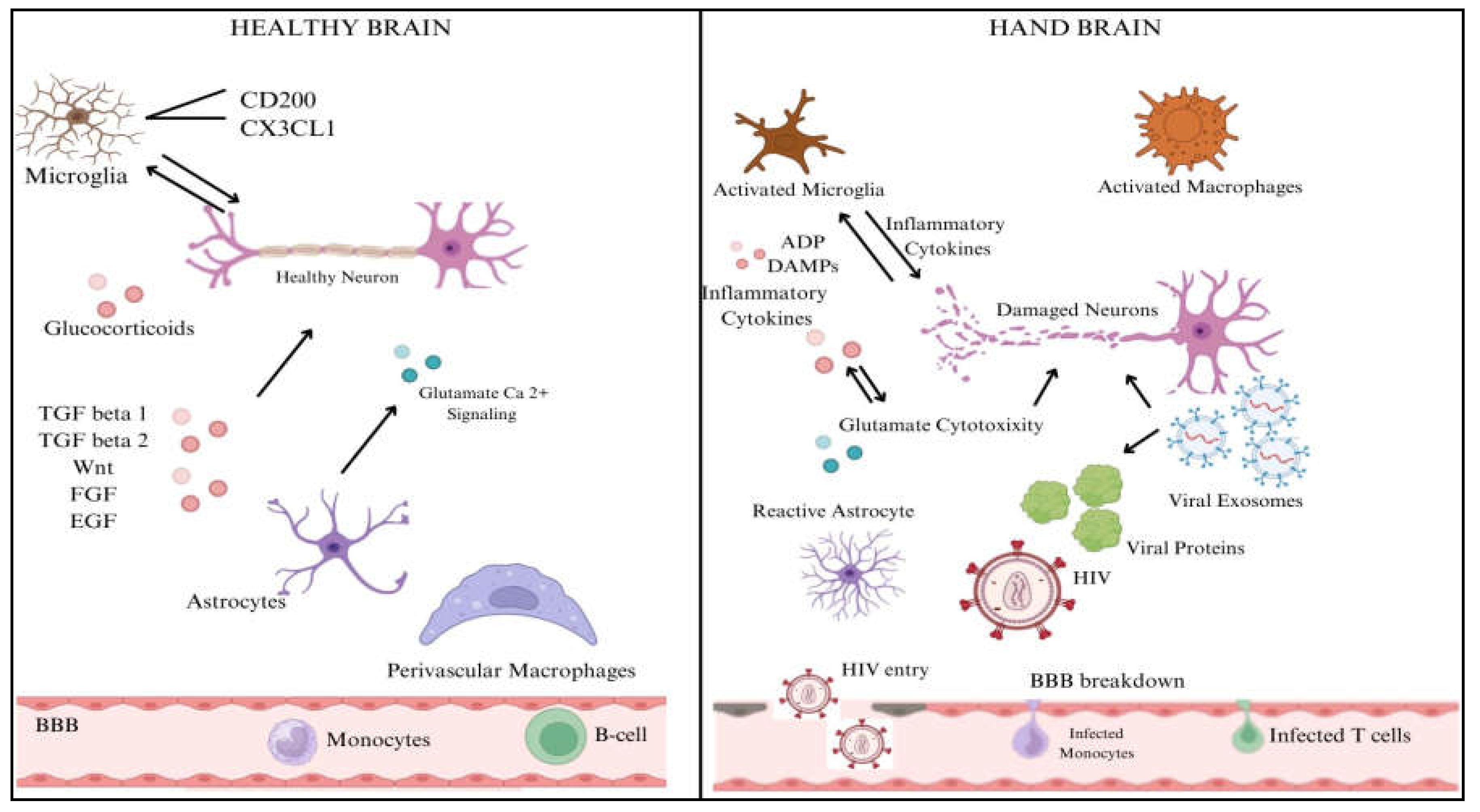

3. Detection Techniques in Neurogenetic Study

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is commonly employed for detecting infectious disease pathogens. However, it has certain limitations, such as requiring a minimum pathogen load in the blood, which may result in false-negative outcomes. Additionally, human bias in laboratory testing due to repetitive pathogen-based assays that improve sensitivity and specificity can affect results. In contrast, host response-based immunodiagnostic techniques offer a more personalized and precise approach to healthcare by tailoring treatments to individual patients. Advancements in omics technologies have identified various molecular host biomarkers as potential candidates for rapid diagnosis in critical conditions. Unlike pathogen-based tests, host immunodiagnostics can differentiate between infectious and non-infectious immune responses, such as sterile inflammation, autoimmune diseases, and malignancies. Techniques such as RT-PCR, RNA sequencing, host gene expression profiling, and metabolic and protein biomarker detection enhance diagnostic accuracy. Integrating genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenomics, lipidomics, and metabolomics has led to developing predictive models incorporating multiple biomarkers. While these novel approaches hold promise for improving infectious disease diagnostics, they have yet to undergo clinical trials or receive approval for clinical application [

48].

Table 1 outlines various detection techniques used to study HIV incorporation in the CNS, grouped into three categories: Molecular Biology and genetic approaches, functional assay techniques, and cell culture model studies. Molecular Biology and Genetic Techniques include PCR, ISH, Western Blotting, ELISA, NGS, and scRNA-seq, used to detect and quantify viral RNA/DNA, identify HIV proteins, assess immune responses, and study genetic factors related to HIV infection in the CNS. These methods have facilitated the identification of novel candidate disease loci and have paved the way for precision therapies, particularly highlighting the pivotal role of NGS in uncovering new genetic variants associated with various neurological conditions [

48,

49]. They help to find the molecular mechanisms behind HIV’s impact on the brain. Functional assay techniques, such as electrophysiology, behavioral tests, Neuroimaging and cellular assays, assess how HIV affects neuronal activity, behavior, brain structure, and function. They allow researchers to evaluate the neurological consequences of HIV infection and identify potential therapeutic targets [

50,

51]. Primary cell cultures, iPSCs, organotypic brain slice cultures, and animal models stimulate human CNS conditions. These models help explore HIV’s direct effects on neuronal and glial cells, neuroinflammation, and the development of neurocognitive disorders, bridging molecular insights with behavioral outcomes [

52]

4. Incorporation of Bioinformatics Techniques in Neurogenetic Study

Integrating bioinformatics techniques into neurogenetic research has revolutionized our understanding of the genetic basis of neurological disorders. Bioinformatics provides computational tools and methodologies to analyse vast amounts of genetic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data, enabling researchers to identify disease-associated genes, pathways, and molecular mechanisms underlying various neurological conditions. With the advancement of high-throughput sequencing technologies such as next-generation sequencing (NGS), whole-genome sequencing (WGS), whole-exome sequencing (WES), and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), bioinformatics has become indispensable for processing and interpreting complex neurogenetic datasets. These approaches help in identifying genetic variants, mutations, and expression patterns associated with neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, epilepsy, schizophrenia, and autism spectrum disorders (ASD) [

7]

.

One of the key applications of bioinformatics in neurogenetic studies is genome-wide association studies (GWAS), which allow researchers to identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and genetic risk factors linked to neurological diseases. To uncover significant gene-disease associations, GWAS datasets are processed using bioinformatics pipelines, including quality control, imputation, statistical analysis, and functional annotation. Moreover, functional genomics approaches such as chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) and assay for transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing (ATAC-seq) provide insights into epigenetic modifications and gene regulation mechanisms influencing neurodevelopment and neurodegeneration. Integrating GWAS with bioinformatics techniques enables the identification of potential therapeutic targets and biomarker discovery for precision medicine [

53]. In addition to genomics, bioinformatics plays a crucial role in transcriptomics in studying gene expression patterns in different neurological conditions. RNA sequencing and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) allow researchers to investigate gene expression differences in specific neuronal populations. Bioinformatics tools such as DESeq2, edgeR, and Seurat help analyze differential gene expression, pathway enrichment, and cell-type-specific gene regulatory networks. Understanding these molecular signatures aids in characterizing the heterogeneity of neurodegenerative diseases and identifying novel therapeutic targets [

54].

Another significant bioinformatics approach is proteomics and metabolomics, which provide complementary insights into the functional impact of genetic mutations in neurological diseases. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics enables identifying and quantifying protein expression changes in affected neurons, while metabolomics helps understand the biochemical pathways altered in neurological disorders. Bioinformatics platforms such as MaxQuant, Perseus, and MetaboAnalyst facilitate the processing and interpretation of these large-scale datasets. Integrating multi-omics data, including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, through systems biology approaches enhances our understanding of disease pathophysiology and aids in personalized medicine [

55]. Furthermore, machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) have emerged as powerful bioinformatics tools in neurogenetics. AI-driven models analyse complex genetic and clinical datasets to predict disease susceptibility, progression, and treatment outcomes. Deep learning algorithms classify neuroimaging data, recognize genetic patterns associated with neurodegeneration, and assist in drug discovery. Computational tools such as PolyPhen, SIFT, and MutationTaster predict the pathogenicity of genetic variants, at the same time, AI-driven integrative platforms like DeepVariant and AlphaFold contribute to the functional annotation of neurological disease-associated mutations [

56].

Moreover, neuroinformatics databases and bioinformatics repositories provide valuable resources for neurogenetic research. Databases such as GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus), ENCODE (Encyclopedia of DNA Elements), dbSNP (Database of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms), and NeuroVault offer extensive datasets for studying gene expression, regulatory elements, and neuroimaging-genetics correlations. These resources enable researchers to perform large-scale data mining, hypothesis testing, and validation of findings in independent cohorts. Despite the significant advancements, bioinformatics in neurogenetics faces challenges such as data heterogeneity, computational complexity, and ethical considerations. Integrating multi-omics datasets requires robust computational frameworks and standardized pipelines for reproducibility and accuracy [

57].

Additionally, the interpretation of genetic variants in clinical practice remains complex, necessitating collaborative efforts between geneticists, bioinformaticians, neurologists, and data scientists to translate findings into actionable clinical insights. Bioinformatics has transformed neurogenetic research by enabling large-scale analysis of genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data. Advanced computational tools and AI-driven approaches facilitate the discovery of genetic risk factors, molecular pathways, and potential therapeutic targets for neurological disorders. While challenges remain, continued progress in bioinformatics methodologies and interdisciplinary collaboration will further enhance our understanding of neurogenetic diseases, ultimately paving the way for precision medicine and personalized therapies [

58]

.

Table 2 summarizes those techniques used commonly to study HIV’s impact on neurogenetics, including genome sequencing, transcriptomics, proteomics, network analysis, machine learning, drug design, and genetic mapping [

59]. These methods help identify genetic variations, gene expression changes, and protein alterations linked to HIV infection in the CNS. They provide insights into neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, and cognitive impairment while guiding the development of personalized treatment strategies and therapeutic targets[

60]. By integrating genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data, these approaches advance our understanding of HIV neuropathogenesis and aid in drug design and disease progression prediction [

61,

62]

5. Clinical Relevance

The future clinical relevance of understanding how HIV impacts neurogenetics encompasses several critical areas poised to advance diagnosis, treatment, and care for HIV-infected individuals. Key advancements include early detection and monitoring through genetic and epigenetic biomarkers of neurocognitive impairment, alongside future neuroimaging innovations for precise visualization of HIV-induced brain changes [

63,

64]. Personalized medicine approaches could optimize treatment regimens by integrating genetic profiling and targeting epigenetic modifications to mitigate neuronal damage. Novel therapeutic targets may emerge from insights into genetic and molecular pathways, potentially leading to neuroprotective agents and immune modulation strategies to bolster CNS resilience. Integrative care models, incorporating neurogenetic insights, aim to enhance overall health outcomes and quality of life through tailored rehabilitation and psychosocial support [

65,

66]. Advances in research tools and longitudinal studies are pivotal, offering a deeper understanding of HIV-neurogenetics interactions and paving the way for innovative therapeutic discoveries and clinical applications in HIV care [

67].

Bioinformatics plays a crucial role in HIV neurogenetics by facilitating precision medicine through the identification of genetic markers and molecular signatures linked to neurocognitive impairment in HIV patients, which informs personalized treatment strategies. It also supports drug discovery efforts by pinpointing specific pathways and molecular targets for developing new therapies targeting HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) [

65,

68]. Additionally, bioinformatics enables early detection of neurologic complications in HIV-infected individuals by uncovering biomarkers and developing diagnostic tools based on genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenetic data [

69,

70]. Moreover, it provides valuable systems biology insights by integrating multi-omics data, enhancing our understanding of HIV-associated transcriptional and epigenetic alterations across multiple cell types, exploring intricate interactions between HIV and the central nervous system (CNS), and advancing knowledge of disease mechanisms and pathophysiology [

71].

6. Conclusion and Future Aspects

There is immense potential in advancing personalized medicine and improving therapeutic strategies for HIV-related neurological complications. As technologies like single-cell sequencing, advanced proteomics, and machine learning continue to evolve, they will enable more precise mapping of the molecular interactions between HIV and the CND. This will enhance our ability to identify novel biomarkers, uncover genetic variations that influence susceptibility and disease progression, and develop targeted treatments that address the underlying neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration caused by the virus. Moreover, integrating these findings into clinical practice could lead to better diagnostic tools, optimized antiretroviral therapies, and interventions tailored to individual genetic profiles, ultimately improving the quality of life for those living with HIV-related neurocognitive disorders.

Addressing knowledge gaps in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) requires a multifaceted future research approach. Longitudinal studies are essential to track HAND progression, distinguishing between reversible and permanent cognitive decline and identifying factors contributing to disease worsening despite viral suppression. Additionally, developing more accurate animal models for HAND is critical, as current models often fail to fully replicate the complexity of HIV’s effects on the human brain, particularly regarding chronic inflammation and synaptic dysfunction. Furthermore, with the ageing HIV-positive population, studies on the impact of ageing on HAND are increasingly important. Aging-related neurodegenerative processes may interact with HIV-associated neuroinflammation, exacerbating cognitive decline. Understanding these interactions can inform tailored interventions to improve cognitive outcomes and quality of life in older adults with HIV.

The development of new diagnostic and therapeutic tools is crucial for improving the management of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND). Identifying reliable biomarkers for early detection of HAND could enable timely intervention before a significant cognitive decline occurs. Advances in neuroimaging, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, and blood-based biomarkers are helping to refine diagnostic accuracy. Additionally, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are transforming HAND research by evaluating complex datasets to identify patterns in cognitive decline, predict disease progression, and optimize personalized treatment strategies. On the therapeutic front, a significant challenge remains the delivery of effective treatments across the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Developing novel drug formulations, such as nanoparticles and small-molecule therapies, that can efficiently penetrate the CNS while minimizing systemic toxicity could revolutionize HAND treatment and improve long-term outcomes for people living with HIV.

Author Contributions

S.J. as the first author to do literary survey about the review topic and write manuscript draft. S.N. contributed to writing manuscript and drawing Figures. V.N. is the corresponding author who had taken leadership in the conceptualization, supervision, and finalization of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to publish the manuscript.

Funding

This research has received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This narrative review synthesizes information from previously published studies, which are appropriately cited within the manuscript. No new data were generated or analysed in this study. Therefore, data sharing is not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ANI |

Asymptomatic Neurocognitive Impairment |

| ART |

Antiretroviral Therapy |

| ATAC-seq |

Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin Using Sequencing |

| BBB |

Blood-brain barrier |

| CCR5 |

Chemokine receptor 5 |

| CNS |

Central Nervous System |

| CND |

Central Nervous Diseases |

| CpG |

Cytosine phosphate Guanine |

| CRISPR |

Cas9 Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) - CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9). |

| CXCR4 |

C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4 |

| DNMT |

DNA Methyltransferase enzyme |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| fMRI |

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| HAD |

HIV-Associated Dementia |

| HAT |

Histone Acetyltransferases |

| HAND |

HIV Associated Neurocognitive Diseases |

| HIV |

Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| HMT |

Histone Methyltransferases |

| HLA |

Human Leukocyte Antigen |

| ISH |

In-situ Hybridization |

| MND |

Mild Neurocognitive Disorder |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NMDA |

N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| PET |

Positron Emission Tomography |

| ROS |

Reactive Oxygen Species |

| scRNA-seq |

Single Cell RNA sequencing |

| scDNA-seq |

Single Cell DNA sequencing |

| SOD |

Superoxide Dismutase |

| SMRT |

Single Molecule Real Time Sequencing |

References

- Takehisa J, Zekeng L, Ido E, et al. Various Types of HIV Mixed Infections in Cameroon. Virology. 1998; 245(1):1–10. [CrossRef]

- Abongwa LE, Nyamache AK, Torimiro JN, Okemo P, Charles F. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 ((HIV-1) subtypes in the northwest region, Cameroon. Virol J. 2019; 16(1):103. [CrossRef]

- Eberle J, Gürtler L. HIV Types, Groups, Subtypes and Recombinant Forms: Errors in Replication, Selection Pressure and Quasispecies. Intervirology. 2012; 55(2):79–83. [CrossRef]

- Hemelaar J, Elangovan R, Yun J, et al. Global and regional molecular epidemiology of HIV-1, 1990–2015: a systematic review, global survey, and trend analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2019; 19(2):143–155. [CrossRef]

- Hussain H, Fadel A, Garcia E, et al. HIV and dementia. The Microbe. 2024; 2:100052. [CrossRef]

- Avdoshina V, Mocchetti I. Recent Advances in the Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of gp120-Mediated Neurotoxicity. Cells. 2022; 11(10):1599. [CrossRef]

- Firdaus Z, Li X. Unraveling the Genetic Landscape of Neurological Disorders: Insights into Pathogenesis, Techniques for Variant Identification, and Therapeutic Approaches. IJMS. 2024; 25(4):2320. [CrossRef]

- Houlden H, Cortese A, Wild E. Neurogenetics. In: Howard R, Kullmann D, Werring D, Zandi M, editors. Neurology [Internet]. 1st ed. Wiley; 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 18]. p. 79–89. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781119715672.ch6. [CrossRef]

- Varatharajan L, Thomas SA. The transport of anti-HIV drugs across blood–CNS interfaces: Summary of current knowledge and recommendations for further research. Antiviral Research. 2009; 82(2):A99–A109. [CrossRef]

- Decloedt EH, Rosenkranz B, Maartens G, Joska J. Central Nervous System Penetration of Antiretroviral Drugs: Pharmacokinetic, Pharmacodynamic and Pharmacogenomic Considerations. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2015; 54(6):581–598. [CrossRef]

- Kang J, Wang Z, Zhou Y, Wang W, Wen Y. Learning from cerebrospinal fluid drug-resistant HIV escape-associated encephalitis: a case report. Virol J. 2023; 20(1):292. [CrossRef]

- Osborne O, Peyravian N, Nair M, Daunert S, Toborek M. The Paradox of HIV Blood–Brain Barrier Penetrance and Antiretroviral Drug Delivery Deficiencies. Trends in Neurosciences. 2020; 43(9):695–708. [CrossRef]

- Bogdan R, Hyde LW, Hariri AR. A neurogenetics approach to understanding individual differences in brain, behavior, and risk for psychopathology. Mol Psychiatry. 2013; 18(3):288–299. [CrossRef]

- Ferrell D, Giunta B. The impact of HIV-1 on neurogenesis: implications for HAND. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014; 71(22):4387–4392. [CrossRef]

- Lindl KA, Marks DR, Kolson DL, Jordan-Sciutto KL. HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorder: Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Opportunities. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2010; 5(3):294–309. [CrossRef]

- Kolanu ND. CRISPR–Cas9 Gene Editing: Curing Genetic Diseases by Inherited Epigenetic Modifications. Glob Med Genet. 2024; 11(01):113–122. [CrossRef]

- Jha NK, Chen W-C, Kumar S, et al. Molecular mechanisms of developmental pathways in neurological disorders: a pharmacological and therapeutic review. Open Biol. 2022; 12(3):210289. [CrossRef]

- Notaras M, Lodhi A, Dündar F, et al. Schizophrenia is defined by cell-specific neuropathology and multiple neurodevelopmental mechanisms in patient-derived cerebral organoids. Mol Psychiatry. 2022; 27(3):1416–1434. [CrossRef]

- Haorah J, Malaroviyam S, Iyappan H, Samikkannu T. Neurological impact of HIV/AIDS and substance use alters brain function and structure. Front Med. 2025; 11:1505440. [CrossRef]

- Mustafa M, Musselman D, Jayaweera D, Da Fonseca Ferreira A, Marzouka G, Dong C. HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorder (HAND) and Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis: Future Directions for Diagnosis and Treatment. IJMS. 2024; 25(20):11170. [CrossRef]

- Norcini-Pala A, Stringer KL, Kempf M-C, et al. Longitudinal associations between intersectional stigmas, antiretroviral therapy adherence, and viral load among women living with HIV using multidimensional latent transition item response analysis. Social Science & Medicine. 2025; 366:117643. [CrossRef]

- Adhikary K, Banerjee A, Sarkar R, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND): Optimal diagnosis, antiviral therapy, pharmacological treatment, management, and future scopes. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2025; 470:123410. [CrossRef]

- Putatunda R, Ho W-Z, Hu W. HIV-1 and Compromised Adult Neurogenesis: Emerging Evidence for a New Paradigm of HAND Persistence. AIDSRev. 2019; 21(1):1908. [CrossRef]

- Wu D, Chen Q, Chen X, Han F, Chen Z, Wang Y. The blood–brain barrier: Structure, regulation and drug delivery. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2023; 8(1):217. [CrossRef]

- Sreeram S, Ye F, Garcia-Mesa Y, et al. The potential role of HIV-1 latency in promoting neuroinflammation and HIV-1-associated neurocognitive disorder. Trends in Immunology. 2022; 43(8):630–639. [CrossRef]

- Graur A, Erickson N, Sinclair P, Nusir A, Kabbani N. HIV-1 gp120 Interactions with Nicotine Modulate Mitochondrial Network Properties and Amyloid Release in Microglia. Neurochem Res. 2025; 50(2):103. [CrossRef]

- Kandanearatchi A, Nath A, Lipton SA, Masliah, E, Everall IP. Protection against HIV-1 gp120 and HIV-1 Tat neurotoxicity. In: Gendelman HE, Grant I, Everall IP, Lipton SA, Swindells S, editors. The Neurology of AIDS [Internet]. Second edition. Oxford University PressOxford; 2005 [cited 2025 Mar 24]. p. 201–210. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/book/51035/chapter/422434483. [CrossRef]

- Smith LK, Babcock IW, Minamide LS, Shaw AE, Bamburg JR, Kuhn TB. Direct interaction of HIV gp120 with neuronal CXCR4 and CCR5 receptors induces cofilin-actin rod pathology via a cellular prion protein- and NOX-dependent mechanism. Wu Y, editor. PLoS ONE. 2021; 16(3):e0248309. [CrossRef]

- Jadhav S, Makar P, Nema V. The NeuroinflammatoryPotential of HIV-1 NefVariants in Modulating the Gene Expression Profile of Astrocytes. Cells. 2022; 11(20):3256. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui A, He C, Lee G, Figueroa A, Slaughter A, Robinson-Papp J. Neuropathogenesis of HIV and emerging therapeutic targets. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. 2022; 26(7):603–615. [CrossRef]

- McRae M. HIV and viral protein effects on the blood brain barrier. Tissue Barriers. 2016; 4(1):e1143543. [CrossRef]

- Jadhav S, Nema V. HIV-Associated Neurotoxicity: The Interplay of Host and Viral Proteins. Nilsen N, editor. Mediators of Inflammation. 2021; 2021:1–11. [CrossRef]

- Pisani A, Paciello F, Del Vecchio V, et al. The Role of BDNF as a Biomarker in Cognitive and Sensory Neurodegeneration. JPM. 2023; 13(4):652. [CrossRef]

- Smith LK, Babcock IW, Minamide LS, Shaw AE, Bamburg JR, Kuhn TB. Direct interaction of HIV gp120 with neuronal CXCR4 and CCR5 receptors induces cofilin-actin rod pathology via a cellular prion protein- and NOX-dependent mechanism. Wu Y, editor. PLoS ONE. 2021; 16(3):e0248309. [CrossRef]

- Nickoloff-Bybel EA, Festa L, Meucci O, Gaskill PJ. Co-receptor signalling in the pathogenesis of neuroHIV. Retrovirology. 2021; 18(1):24. [CrossRef]

- Freedman BD, Liu Q-H, Del Corno M, Collman RG. HIV-1 gp120 Chemokine Receptor-Mediated Signalling in Human Macrophages. IR. 2003; 27(2–3):261–276. [CrossRef]

- Lunardi LW, Bragatte MADS, Vieira GF. The influence of HLA/HIV genetics on the occurrence of elite controllers and a need for therapeutics geotargeting view. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2021; 25(5):101619. [CrossRef]

- Lobos CA, Downing J, D’Orsogna LJ, Chatzileontiadou DSM, Gras S. Protective HLA-B57: T cell and natural killer cell recognition in HIV infection. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2022; 50(5):1329–1339. [CrossRef]

- Jadhav S, Nema V. Association of Viral and Host Genetic Architecture with the Status of Neurocognitive Disorder in HIV-Infected Individuals. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2023; :aid.2022.0099. [CrossRef]

- Plaza-Jennings A, Akbarian S. Genomic Exploration of the Brain in People Infected with HIV—Recent Progress and the Road Ahead. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2023; 20(6):357–367. [CrossRef]

- Moore LD, Le T, Fan G. DNA Methylation and Its Basic Function. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013; 38(1):23–38. [CrossRef]

- Mackiewicz M (Mack), Overk C, Achim CL, Masliah E. Pathogenesis of age-related HIV neurodegeneration. J Neurovirol. 2019; 25(5):622–633. [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich M. DNA hypermethylation in disease: mechanisms and clinical relevance. Epigenetics. 2019; 14(12):1141–1163. [CrossRef]

- Nehme Z, Pasquereau S, Herbein G. Control of viral infections by epigenetic-targeted therapy. Clin Epigenet. 2019; 11(1):55. [CrossRef]

- Kong W, Frouard J, Xie G, et al. Neuroinflammation generated by HIV-infected microglia promotes dysfunction and death of neurons in human brain organoids. Abramov A, editor. PNAS Nexus. 2024; 3(5):pgae179. [CrossRef]

- El-Amine R, Germini D, Zakharova VV, et al. HIV-1 Tat protein induces DNA damage in human peripheral blood B-lymphocytes via mitochondrial ROS production. Redox Biology. 2018; 15:97–108. [CrossRef]

- Perry SW, Norman JP, Litzburg A, Zhang D, Dewhurst S, Gelbard HA. HIV-1 Transactivator of Transcription Protein Induces Mitochondrial Hyperpolarization and Synaptic Stress Leading to Apoptosis. The Journal of Immunology. 2005; 174(7):4333–4344. [CrossRef]

- Altindiş M, Kahraman Kilbaş EP. Managing Viral Emerging Infectious Diseases via Current and Future Molecular Diagnostics. Diagnostics. 2023; 13(8):1421. [CrossRef]

- Pinto WBVDR, Oliveira ASB, Carvalho AADS, Akman HO, Souza PVSD. Editorial: The expanding clinical and genetic basis of adult inherited neurometabolic disorders. Front Neurol. 2023; 14:1255513. [CrossRef]

- O’Connor EE, Sullivan EV, Chang L, et al. Imaging of Brain Structural and Functional Effects in People With Human Immunodeficiency Virus. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2023; 227(Supplement_1):S16–S29. [CrossRef]

- Mao S, Li C, Yuan B, Yu L, Shang H. Editorial: Neurogenetic disorders: from the tests to the clinic. Front Neurol. 2023; 14:1236350. [CrossRef]

- Donadoni M, Cakir S, Bellizzi A, Swingler M, Sariyer IK. Modeling HIV-1 infection and NeuroHIV in hiPSCs-derived cerebral organoid cultures. J Neurovirol. 2024; 30(4):362–379. [CrossRef]

- Uffelmann E, Huang QQ, Munung NS, et al. Genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Methods Primers. 2021; 1(1):59. [CrossRef]

- Awuah WA, Ahluwalia A, Ghosh S, et al. The molecular landscape of neurological disorders: insights from single-cell RNA sequencing in neurology and neurosurgery. Eur J Med Res. 2023; 28(1):529. [CrossRef]

- Vitorino R. Transforming Clinical Research: The Power of High-Throughput Omics Integration. Proteomes. 2024; 12(3):25. [CrossRef]

- Ahuja S, Zaheer S. Advancements in pathology: Digital transformation, precision medicine, and beyond. Journal of Pathology Informatics. 2025; 16:100408. [CrossRef]

- Nayak L, Dasgupta A, Das R, Ghosh K, De RK. Computational neuroscience and neuroinformatics: Recent progress and resources. J Biosci. 2018; 43(5):1037-1054. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field MA. Bioinformatic Challenges Detecting Genetic Variation in Precision Medicine Programs. Front Med. 2022; 9:806696. [CrossRef]

- Savvateeva-Popova EV, Nikitina EA, Medvedeva AV. Neurogenetics and neuroepigenetics. Russian Journal of Genetics. 2015; 51(5):518–528. [CrossRef]

- Johnson SD, Guda RS, Kumar N, Byrareddy SN. Host peripheral immune dynamics increase HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders incidence and progression. HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders [Internet]. Elsevier; 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 18]. p. 147–160. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780323997447000250. [CrossRef]

- Ojeda-Juárez D, Kaul M. Transcriptomic and Genetic Profiling of HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders. Front Mol Biosci. 2021; 8:721954. [CrossRef]

- Fields J, Dumaop W, Langford TD, Rockenstein E, Masliah E. Role of Neurotrophic Factor Alterations in the Neurodegenerative Process in HIV Associated Neurocognitive Disorders. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2014; 9(2):102–116. [CrossRef]

- Saxena SK, Sharma D, Kumar S, Puri B. Understanding HIV-associated neurocognitive and neurodegenerative disorders (neuroAIDS): enroute to achieve the 95-95-95 target and sustainable development goal for HIV/AIDS response. VirusDis. 2023; 34(2):165–171. [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Jiu X, Wang Z, Zhang Y. Neuroimaging advances in neurocognitive disorders among HIV-infected individuals. Front Neurol. 2025; 16:1479183. [CrossRef]

- Griñán-Ferré C, Bellver-Sanchis A, Guerrero A, Pallàs M. Advancing personalized medicine in neurodegenerative diseases: The role of epigenetics and pharmacoepigenomics in pharmacotherapy. Pharmacological Research. 2024; 205:107247. [CrossRef]

- Tonti E, Dell’Omo R, Filippelli M, et al. Exploring Epigenetic Modifications as Potential Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets in Glaucoma. IJMS. 2024; 25(5):2822. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y. Advances in HIV Research: Mechanisms, Transmission Routes, and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. HSET. 2024; 123:505–509. [CrossRef]

- Borrajo A, Pérez-Rodríguez D, Fernández-Pereira C, Prieto-González JM, Agís-Balboa RC. Genomic Factors and Therapeutic Approaches in HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders: A Comprehensive Review. IJMS. 2023; 24(18):14364. [CrossRef]

- Jang W-J, Lee S, Jeong C-H. Uncovering transcriptomic biomarkers for enhanced diagnosis of methamphetamine use disorder: a comprehensive review. Front Psychiatry. 2024; 14:1302994. [CrossRef]

- Du P, Fan R, Zhang N, Wu C, Zhang Y. Advances in Integrated Multi-omics Analysis for Drug-Target Identification. Biomolecules. 2024; 14(6):692. [CrossRef]

- Yang J, Agrawal K, Stanley J, et al. Multi-omic Characterization of HIV Effects at Single Cell Level across Human Brain Regions [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Mar 18]. Available from: http://biorxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2025.02.05.636707.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).