1. Introduction

The advent of social media has unlocked novel possibilities for marketers to forge connections with consumers [

1]. As a transformative marketing tool, social media marketing has redefined the paradigm of brand-consumer interactions, revolutionizing how businesses communicate and disseminate brand-related information [

2]. Concurrently, it has precipitated the evolution of promotional mix dynamics within marketing communications [

3]. While marketing strategies are increasingly shaped by social media, these platforms are simultaneously reshaping consumer communication patterns and exerting profound influences on purchasing behaviors [

4]. Consumers engage with social media for multifaceted purposes [

5]: some utilize it to seek product-specific information, while others leverage it to compare features, attributes, and pricing across brands [

6]. The inherent capacity of social media to enable both access to and generation of user-driven content ensures real-time information dissemination and peer-to-peer visibility [

7]. In contrast to the unidirectional communication and exorbitant costs associated with traditional media campaigns (e.g., print and broadcast channels), social media distinguishes itself through bidirectional information exchange and collaborative content sharing [

8]. Consequently, an expanding array of brands now strategically harness these platforms for marketing endeavors.

In recent years, rapid economic expansion has precipitated the excessive exploitation and depletion of natural resources, exacerbating global crises such as climate change, environmental degradation, ozone depletion, and other health-compromising ecological challenges [

9]. Against this backdrop, green consumption has emerged as a pragmatic imperative to mitigate resource constraints and environmental pressures, driven by escalating energy consumption and carbon emissions at the consumer level, thereby fostering sustainable socioeconomic development to a certain extent [

10]. Governments worldwide have intensified advocacy for green lifestyles, catalyzing a marked elevation in public green consumption awareness. Green products, characterized by their eco-friendliness, energy efficiency, and health benefits, have consequently gained traction among consumers [

11]. However, extant research reveals a persistent gap between consumers' professed positive attitudes toward green products and their actual purchasing behaviors [

12,

13]. When selecting green products, consumers typically undergo a value-based trade-off process, favoring items that deliver superior value propositions. This necessitates corporate emphasis on social responsibility to enhance green product offerings, coupled with consumer education to strengthen green consumption ethics and prioritize eco-conscious purchasing decisions [

14]. Green marketing, defined as the promotion of environmentally safe products through strategies that reshape consumer perceptions of brands, has thus gained strategic relevance [

15].

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Media Marketing

The conceptualization of social media marketing was first articulated by Mayfield, who defined social media as an online medium providing platforms for individuals to articulate and share perspectives, experiences, and opinions [

16]. Social media marketing has since evolved into a cornerstone for corporate green communication. Through meta-analytic synthesis, Kim et al. (2021) demonstrated that entertainment-oriented content enhances green advertisement recall, a phenomenon neurologically linked to dopamine reward mechanisms in the prefrontal cortex (Chen et al., 2022) [

17]. Breakthroughs in precision targeting technologies have overcome traditional mass communication limitations. Leveraging a natural experiment involving 2 million Twitter datapoints, Laroche et al. (2023) validated that location-based service (LBS) targeting tripled conversion rates for green product inquiries [

18]. The interactivity dimension exhibits bidirectional empowerment characteristics, with user-generated content (UGC) amplifying green brand trust through social identification mechanisms (Wang & Zhang, 2022) [

19].

The precision targeting dimension achieves communication optimization via big data profiling. Laroche et al. (2023), utilizing geo-tagged Twitter data, further demonstrated that LBS-driven campaigns significantly elevate green product consultation conversion rates [

18]. Machine learning algorithms have augmented predictive capabilities for user needs; Wang et al. (2022) empirically confirmed that personalized recommendations based on consumption histories boost green product click-through rates by 2.8-fold [

19]. Brands increasingly employ tailored social media messaging to engage niche audiences, as precision targeting enables the delivery of hyper-personalized information and products aligned with individual preferences [

20], thereby enhancing user experience and platform utility [

21]. Operationally, precision targeting quantifies the extent to which services are customized to meet consumer idiosyncrasies [

22].

Social media platforms serve as real-time conduits for trending information and topical discourse [

23]. By disseminating cutting-edge trend analyses, these platforms effectively capture consumer attention [

22]. The novelty dimension of social media marketing empowers marketers to deliver timely insights on emerging trends, creating consumer value through reduced information search costs [

24].

The entertainment dimension profoundly influences consumer attitudes via emotional arousal mechanisms. Kim et al. (2021) meta-analytically established that humor-infused green advertisements enhance memory retention [

25], a process neurologically mediated by dopamine reward circuit activation in the prefrontal cortex (Chen et al., 2022) [

17]. Neuroimaging studies further reveal that entertaining content reduces price sensitivity toward green premiums, thereby elevating payment willingness (Lee et al., 2021) [

26]. Conceptually, social media entertainment refers to marketers' strategic creation of enjoyable and playful user experiences during platform engagement (Ashley & Tuten, 2015) [

27]. Such entertainment-driven strategies foster brand affinity and strengthen purchase intentions (Gallaugher & Ransbotham, 2010) [

28]. Marketers effectively capture attention by sharing product visuals and narratives that fulfill hedonic needs, thereby achieving superior engagement (Merrilees, 2016) [

29].

Regarding interactivity, this dimension quantifies a platform's capacity to facilitate bidirectional opinion exchange and collaborative information sharing [

28]. As a catalyst for UGC creation, interactivity reinforces brand attitudes and purchase motivations [

30]. Experimental evidence from Zhang and Benoit (2023) illustrates that UGC elevates green brand trust through social validation mechanisms, particularly among Generation Z cohorts, where real-time comment interactions account for 19% variance in payment willingness [

31].

2.2. Green Premium

The economic essence of the green premium lies in the price internalization of environmental externalities. Porter and Kramer (2019) posit that green premiums should internalize lifecycle environmental costs, requiring pricing strategies that balance consumer affordability with ecological benefits [

32]. Empirical studies identify an inverted U-curve in premium acceptance: willingness plummets when premiums exceed 15% of benchmark prices [

33].

2.3. Willingness to Pay Green Premium (WTPGP)

WTPGP denotes the maximum monetary amount consumers are prepared to expend for environmentally advantageous products/services [

34]. This metric reflects consumers' proactive commitment to absorbing additional costs for ecological benefits. However, when green premiums surpass psychological accounting thresholds, even environmentally conscious consumers may defer purchases [

35]. Social media "green influencers" amplify WTPGP by 1.8-fold among followers through demonstration effects [

36]. Experimental data indicate that carbon footprint labeling increases premium payment likelihood by 37% [

37].

2.4. Green Marketing (GM)

GM fundamentally achieves synergy between environmental stewardship and market performance through value reconstruction. Hart and Dowell (2023), applying resource-based theory, identify GM's competitive advantage as deriving from dynamic integration of green knowledge repositories, exemplified by supply chain traceability technologies enhancing transparency [

38]. Green experiential marketing leverages embodied cognition mechanisms to intensify value perception; for instance, carbon-neutral travel programs utilizing immersive environmental education boost WTP by 22% [

39].

2.5. Research Model

Proposed by Mehrabian and Russell in 1974, the Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) theory has been widely applied in consumer behavior research [

40]. This theoretical framework posits that external environmental stimuli (S) such as brand or marketing initiatives can activate individuals' internal organismic variables (O), including perceptions or trust mechanisms, thereby eliciting behavioral responses (R) like purchasing decisions or product adoption.

Originating from communication studies, the Uses and Gratifications Theory was initially employed in traditional platforms and technological media as an analytical tool for understanding consumer emotions, cognitive processes, and emerging needs. It has been particularly utilized to examine specific cases where media successfully engage consumer audiences [

41]. With the advent of internet technologies and novel interactive platforms - including email, instant messaging, blogs, chat rooms, and other digital communication formats - this theoretical framework has been extensively applied to social media research as well.

3. Research Methodology

This study formulates hypotheses drawing upon the Uses and Gratifications (U&G) theory and Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) framework. The U&G theory stands as one of the most prevalent frameworks for examining media usage motivations. It posits that individuals proactively select specific media and content to achieve predetermined objectives or effects [

42]. Human behaviors are fundamentally driven by the pursuit of gratifications, with behavioral outcomes manifesting as attained satisfactions. The core impetus behind such behaviors resides in gratification-seeking motivations, wherein social media activities serve as instrumental means to obtain targeted satisfactions, while motivations activate goal-oriented actions [

43]. Grounded in U&G theory, consumers derive satisfaction from green products by fulfilling their ecological demands through social media marketing-enabled green premium payments.

The SOR paradigm contends that human information processing originates from external stimuli [

44]. Individuals exposed to environmental stimuli undergo psychological processes that culminate in behavioral responses. Within this theoretical context, social media marketing constitutes the "stimulus" triggering consumers' willingness to pay green premiums. Consumers' cognitive perceptions regarding green premium payments represent the "organism" component, whereas their final payment intentions correspond to the "response" element in the SOR model.

3.1. Hypotheses Development

3.1.1. Relationship Between Social Media Marketing and Green Marketing

Existing scholarship recognizes that brand communications incorporating entertainment elements are perceived as enjoyable and playful [

27], motivating consumers to invest greater effort in brand exploration [

45]. Entertainment-oriented social media marketing content serves dual functions: providing engaging information while reinforcing affective brand attachments [

46]. As a potent motivator for social media engagement, entertainment value stimulates user interactions with corporate brands [

47]. Consumers demonstrate willingness to like, comment on, and share platform content, collaboratively constructing shared experiences with like-minded peers [

48]. Hedonic motivations significantly drive content creation intentions, with pleasure-seeking users exhibiting heightened propensity for content uploads [

49]. These findings substantiate entertainment's pivotal role in advancing green marketing initiatives.

Social media marketing enables customized brand communication tailored to consumer needs [

50]. Through platform-based dissemination of product information aligned with consumer preferences - encompassing pricing, attributes, and functionalities - marketers enhance perceived brand value and cultivate brand trust [

51]. Precision-targeted marketing optimizes cognitive experiences and emotional connections, stimulating consumer engagement [

28] and predisposing brands to become primary choices during decision-making processes [

52].

Interactive social media features facilitate bidirectional brand-consumer communication, fostering positive brand perceptions [

51]. Branded platforms encourage user-generated content sharing to amplify interactivity [

53], while marketers incentivize participation through storytelling initiatives, brand advocacy campaigns, and subscription solicitations [

28]. Such participatory activities strengthen consumer-brand interactions [

54], ultimately enhancing comprehension of product attributes and brand advantages [

55]. Consumers actively consume and disseminate brand-related information to expand knowledge networks [

56], simultaneously fulfilling needs for social validation [

57].

Novelty-driven content consumption enables consumers to track brand innovations and industry trends [

58]. Social media information demonstrating temporal relevance proves particularly effective in consumer engagement [

28]. Fresh informational inputs capture attention, evoke positive affect, and reinforce loyalty intentions [

59]. As consumers increasingly rely on social media recommendations during decision-making processes, motivation to explore brand-related content intensifies accordingly [

60].

Synthesizing these theoretical perspectives, this study proposes the following hypotheses concerning social media marketing's impact on green marketing:

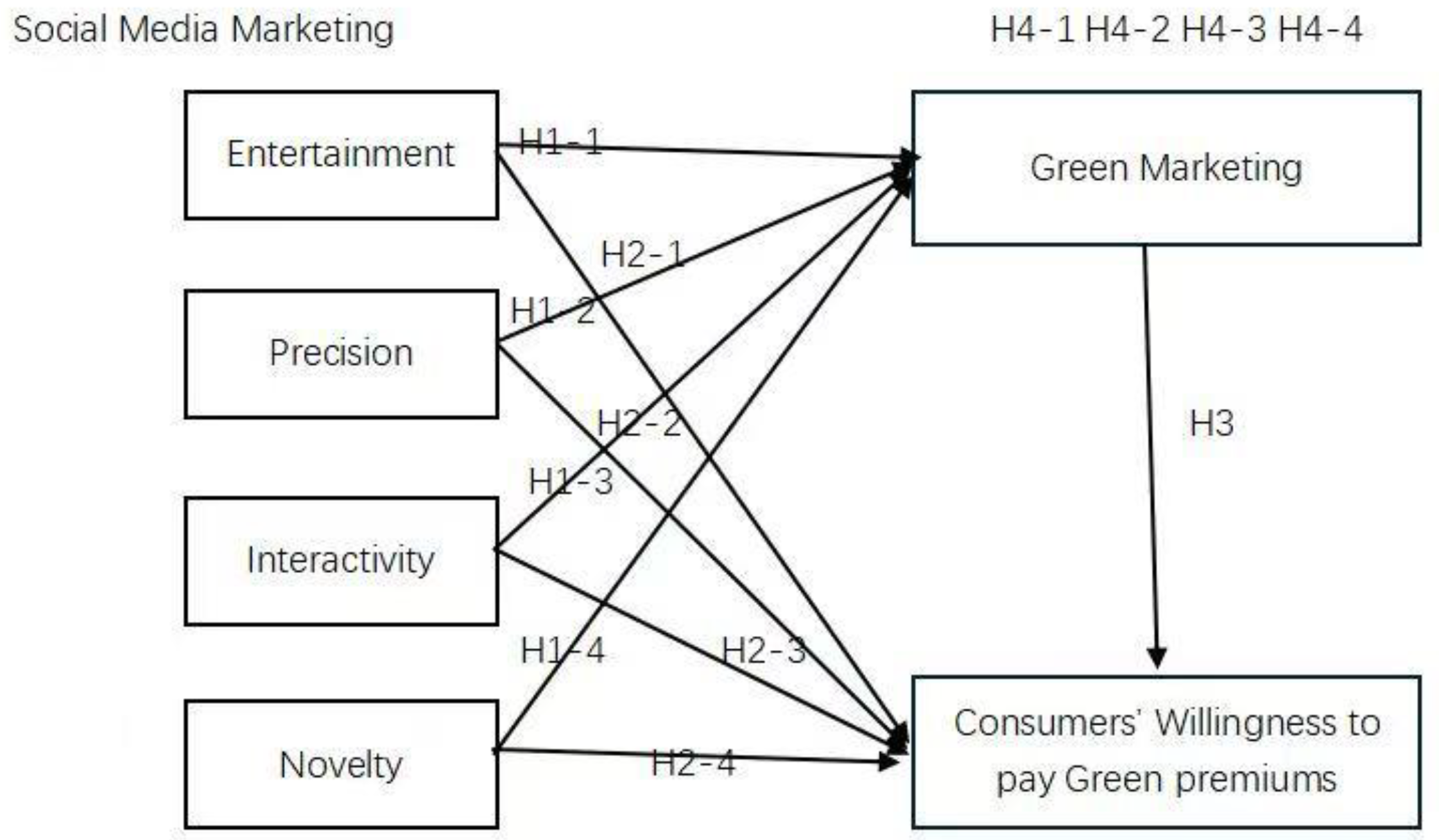

H1: Social media marketing exerts a positive influence on green marketing.

H1-1: The entertainment dimension of social media marketing positively affects green marketing.

H1-2: The precision dimension of social media marketing positively affects green marketing.

H1-3: The interactivity dimension of social media marketing positively affects green marketing.

H1-4: The novelty dimension of social media marketing positively affects green marketing.

3.1.2. Relationship Between Social Media Marketing and Consumers’ Green Premium Payment Willingness

Given consumers' growing reliance on social networks for decision-making, purchase intentions are profoundly shaped by brand-consumer interactions [

61]. Purchase intention—the psychological stage where consumers develop behavioral willingness toward a product or brand—is recognized as a primary objective of brand-driven social media campaigns [

62]. Empirical evidence indicates that heightened social media engagement correlates with increased likelihood of future brand purchases, thereby cementing critical consumer-brand relationships.

The entertainment dimension directly influences WTP through emotional transference mechanisms. Exposure to green information in pleasurable states triggers emotional generalization effects, enhancing premium acceptance [

33]. Precision targeting elevates WTP by reducing decision-making friction; personalized recommendations based on consumption histories amplify green premium payment willingness by 2.3-fold [

19]. Interactivity drives premium payments via social proof mechanisms: Zhang and Benoit's (2023) experiment revealed that real-time comment interactions boost WTP by 33%, particularly among "green-hesitant" consumers [

31]. Novelty enhances WTP through cognitive scarcity perceptions, as evidenced by limited-edition green products paired with AR launch ceremonies significantly elevating payment willingness [

39]. Neuroscientific findings further demonstrate that novel marketing stimuli activate the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, accelerating decision-making by amplifying symbolic value attribution to green premiums [

17].

Building on this evidence, the study proposes hypotheses regarding social media marketing’s impact on green premium payment willingness:

H2: Social media marketing positively influences consumers’ green premium payment willingness.

H2-1: The entertainment dimension of social media marketing positively affects green premium payment willingness.

H2-2: The precision dimension of social media marketing positively affects green premium payment willingness.

H2-3: The interactivity dimension of social media marketing positively affects green premium payment willingness.

H2-4: The novelty dimension of social media marketing positively affects green premium payment willingness.

3.1.3. Mediating Role of Green Marketing

Green marketing effectively strengthens green purchase intentions by enhancing consumers’ ecological product knowledge [

63]. As sustainable consumption norms gain societal traction, green brand images are more readily embraced, elevating consumer satisfaction, brand loyalty, and green purchase intentions [

64].

The entertainment dimension indirectly impacts WTP through green marketing’s affective reinforcement pathway. Green marketing mediates 52% of the relationship between entertainment and WTP, indicating that consumers first associate entertaining content with brands’ environmental stewardship before accepting premiums [

26]. Precision exerts full mediation via green marketing’s informational optimization pathway. When recommendations align with consumers’ eco-values, green marketing credibility scores rise, resulting in a 1.7-fold WTP increase [

19].

These findings suggest green marketing’s significant impact on green purchase intentions, potentially extending to green premium payment willingness. Consequently, the study posits green marketing as a mediator:

H3: Green marketing positively influences consumers’ green premium payment willingness.

H4-1: Green marketing mediates the relationship between social media marketing entertainment and green premium payment willingness.

H4-2: Green marketing mediates the relationship between social media marketing precision and green premium payment willingness.

H4-3: Green marketing mediates the relationship between social media marketing interactivity and green premium payment willingness.

H4-4: Green marketing mediates the relationship between social media marketing novelty and green premium payment willingness.

3.2. Research Model

Building upon the aforementioned theoretical foundation, this study constructs a conceptual research model (as illustrated in the diagrammatic framework). The model positions social media marketing as the independent variable, consumers’ green premium payment willingness as the dependent variable, and green marketing as the mediating variable.

3.3. Measurement Instruments

To empirically examine the relationships among social media marketing, green premium payment willingness, and green marketing, this study employs SPSS 26.0 for demographic profiling, reliability testing, and exploratory factor analysis (EFA), alongside AMOS 23.0 for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), path analysis, and mediation effect testing. Drawing from validated measurement scales in prior literature, a structured questionnaire was developed using Likert-type scales for all constructs. The instrument’s operationalization is summarized in the appended

Table 1.

The research targets active social media platform users as the study population. An online survey distributed via Wenjuanxing (a leading Chinese survey platform) yielded 345 initial responses, with 313 valid questionnaires retained after data cleansing, achieving a 90.7% validity rate.

4. Research Findings

4.1. Demographic Analysis

Table 2 presents the demographic profile of the 313 valid samples. The majority of respondents were female, with most participants aged between 23 and 40. Consumers reported an average daily social media usage duration of 3–4 hours. Detailed demographic characteristics are summarized in

Table 2.

4.2. Reliability Analysis

Reliability testing was conducted to assess the consistency, stability, and dependability of measurements. Using SPSS 26.0, Cronbach’s alpha values were calculated for each item and construct. As shown in

Table 3, all constructs exhibited Cronbach’s alpha values exceeding 0.7 (α > 0.7), confirming strong internal consistency and satisfactory questionnaire reliability.

4.3. Validity Analysis

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s tests were performed via SPSS 26.0 to evaluate the suitability of the model for factor analysis. Results (

Table 4) revealed a KMO value of 0.930 (> 0.7) and statistically significant Bartlett’s test results (p < 0.001), confirming robust validity and appropriateness for factor analysis.

4.4. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

EFA was conducted using SPSS 26.0 with principal component analysis (PCA) for factor extraction. The scree plot (

Table 5) identified six factors with eigenvalues >1, collectively explaining 74.077% of the total variance, indicating reasonable factor extraction.

Post-rotation via Varimax orthogonal rotation (

Table 6) demonstrated all measurement items exhibiting factor loadings >0.5, confirming strong construct validity.

4.5. Path Analysis

Following Hair et al.’s (2017) guidelines [

65], a covariance-based structural equation modeling (SEM) approach was adopted. Model fit indices (

Table 7) met established thresholds: χ²/df = 1.206, GFI = 0.913, AGFI = 0.896, CFI = 0.988, NFI = 0.933, TLI = 0.986, RMSEA = 0.026.

The entertainment, precision, and interactivity dimensions of social media marketing exhibited statistically significant positive effects on green marketing, while novelty demonstrated no significant influence. Hypotheses H1-1, H1-2, and H1-3 were empirically supported, whereas H1-4 was rejected. Concurrently, the entertainment, precision, and novelty dimensions significantly enhanced green premium payment willingness, though interactivity failed to exert a direct impact on green marketing. This pattern corroborated hypotheses H2-1, H2-2, and H2-4, while invalidating H2-3. Furthermore, green marketing demonstrated a robust positive correlation with consumers’ willingness to pay green premiums, thereby confirming Hypothesis H3.

4.6. Mediation Effect Analysis

The predominant method for testing mediation effects follows a three-step causal pathway approach: 1. Initial Correlation Testing: Verify significant correlations between (a) independent and mediating variables, (b) independent and dependent variables, and (c) mediating and dependent variables. 2. Mediation Model Integration: If all three correlations prove significant, incorporate the mediator into the relationship between independent and dependent variables. 3. Mediation Type Determination: Partial Mediation: Observed when the independent-dependent relationship attenuates yet remains statistically significant post-mediation inclusion. Full Mediation: Established if the independent-dependent relationship becomes non-significant after mediator introduction. No Mediation: Concluded when the independent-dependent relationship remains unchanged despite mediator integration.

Table 8.

| Path Relationships |

Path |

Estimate |

Lower |

Upper |

P |

| Direct Effects |

Entertainment → Green Premium Payment |

0.186 |

0.069 |

0.316 |

0.002 |

| Novelty → Green Premium Payment |

0.212 |

0.073 |

0.360 |

0.007 |

| Interactivity → Green Premium Payment |

0.095 |

-0.031 |

0.213 |

0.133 |

| Precision → Green Premium Payment |

0.176 |

0.046 |

0.306 |

0.010 |

| Indirect Effects |

Entertainment → Green Marketing→ Green Premium Payment |

0.030 |

0.005 |

0.075 |

0.021 |

| Novelty → Green Marketing→ Green Premium Payment |

0.007 |

-0.011 |

0.043 |

0.375 |

| Interactivity → Green Marketing→ Green Premium Payment |

0.026 |

0.004 |

0.062 |

0.025 |

| Precision → Green Marketing→ Green Premium Payment |

0.019 |

0.001 |

0.055 |

0.034 |

| Total Effects |

Entertainment → Green Premium Payment |

0.216 |

0.101 |

0.353 |

0.001 |

| Novelty → Green Premium Payment |

0.218 |

0.078 |

0.364 |

0.007 |

| Interactivity → Green Premium Payment |

0.121 |

0.004 |

0.231 |

0.040 |

| Precision → Green Premium Payment |

0.194 |

0.068 |

0.325 |

0.004 |

4.6.1. Direct Effects

Entertainment → Green Premium Payment: The 95% confidence interval excludes zero (95% CI: 0.069–0.316), thereby confirming the existence of a significant direct effect pathway.

Novelty → Green Premium Payment: The 95% confidence interval excludes zero (95% CI: 0.073–0.36), thus validating the presence of a direct effect.

Interactivity → Green Premium Payment: The 95% confidence interval includes zero (95% CI: −0.031–0.213), indicating no statistically significant direct effect.

Precision → Green Premium Payment: The 95% confidence interval excludes zero (95% CI: 0.046–0.306), confirming a significant direct effect pathway.

4.6.2. Indirect Effects

Entertainment → Green Marketing → Green Premium Payment: The 95% confidence interval excludes zero (95% CI: 0.005–0.075), establishing the presence of a significant indirect mediation pathway.

Novelty → Green Marketing → Green Premium Payment: The 95% confidence interval includes zero (95% CI: −0.011–0.043), demonstrating no statistically meaningful mediation effect.

Interactivity → Green Marketing → Green Premium Payment: The 95% confidence interval excludes zero (95% CI: 0.004–0.062), confirming a significant indirect mediation effect.

Precision → Green Marketing → Green Premium Payment: The 95% confidence interval excludes zero (95% CI: 0.001–0.055), supporting the existence of an indirect mediation pathway.

4.6.3. Total Effects

Entertainment → Green Premium Payment: The 95% confidence interval excludes zero (95% CI: 0.101–0.353), affirming a significant total effect.

Novelty → Green Premium Payment: The 95% confidence interval excludes zero (95% CI: 0.078–0.364), validating the presence of a total effect.

Interactivity → Green Premium Payment: The 95% confidence interval excludes zero (95% CI: 0.004–0.231), confirming a statistically significant total effect.

Precision → Green Premium Payment: The 95% confidence interval excludes zero (95% CI: 0.068–0.325), establishing a robust total effect pathway.

5. Research Conclusions

5.1. Research Conclusions

The hypotheses proposed in this study draw on the Uses and Gratifications theory (U&G) and the Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) model. With green marketing as the mediating variable, this study analyzes the influence and mechanism of social media marketing on consumers' willingness to pay a green premium. The research findings are as follows: (1) In the process of social media marketing, entertainment, precision, and interactivity all have significant positive impacts on green marketing. The main reason lies in that social media marketing conducts promotion, investment, and publicity in green marketing through the entertainment of its content, precise information push to consumers, as well as interactive participation and emotional resonance with consumers, which affects consumers' cognition of green brand images and acquisition of green knowledge. (2) Entertainment, precision, and novelty in social media marketing have significant positive impacts on consumers' willingness to pay a green premium. When consumers perceive that social media marketing is more entertaining, they are more likely to engage in information search and reading on social media, and learn more green knowledge, thus increasing their willingness to pay a green premium. When consumers see information that is more relevant to their interests and needs, it can better promote their behaviors related to the willingness to pay a green premium. (3) Regarding the mediating effect of green marketing, green marketing has a certain mediating effect in the process of how entertainment, interactivity, and precision influence the willingness to pay a green premium. Among them, green marketing plays a partial mediating role in the influence of entertainment and precision on the willingness to pay a green premium; green marketing plays a full mediating role in the influence of interactivity on the willingness to pay a green premium. In the process of information transmission, by accurately disseminating information such as green product certification, production process transparency, production technology, and environmental friendliness, consumers' cognition of green value is strengthened. At the same time, with the help of the pleasant and interesting content of social media marketing, the environmental image of the brand is constructed, stimulating consumers' sense of environmental responsibility and identity.

This study makes contributions both theoretically and practically. Firstly, through empirical analysis of the influence of green marketing on the relationship between social media marketing and consumers' willingness to pay a green premium, this study provides some theoretical references for future research. Secondly, by combining and applying the SOR model and the Uses and Gratifications theory (U&G) to the study of how social media marketing affects consumers' willingness to pay a green premium, and through this model and theory, it is possible to understand how social media marketing influences consumers' willingness to pay a green premium through green marketing. The combination of these two theories provides a new perspective for this study, which is more conducive to a deeper understanding of the mechanism by which social media marketing affects consumers' willingness to pay a green premium. Finally, as various brands enter social media platforms, they attach more and more importance to social media marketing, and the competition is becoming increasingly fierce. The costs of advertising on various social media platforms are also rising. This study can help various brands understand which marketing methods are more effective in increasing consumers' willingness to pay a green premium.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Although this study has certain contributions both theoretically and practically, there are still some limitations. Firstly, consumers can be divided into corporate consumers and individual consumers. The survey respondents are limited to individual consumers, which has certain limitations and geographical biases. If the respondents are expanded to include corporate consumers, it may be more persuasive. Secondly, this study takes green marketing as the mediating variable, which has certain limitations in its selection. If future research can consider incorporating mediating variables from other dimensions for analysis, such as green satisfaction, green trust, green perceived value, consumer loyalty, etc., it will be possible to have a more comprehensive understanding of the influence of social media marketing on consumers' willingness to pay a green premium.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Yuening Long.; methodology, Yuening Long.; software, Zhuo Qi; validation, Zhuo Qi.; formal analysis, Zhuo Qi; investigation, Cheng Wu.; resources, Yuening Long.; data curation, Zhuo Qi.; writing—original draft preparation,Chao Ding.; writing—review and editing, Jianwei XU.; supervision, Yuening Long.and Zhuo Qi.; project administration, Yuening Long.; funding acquisition, Yuening Long. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received China Ministry of Education Industry-Education-Research Project: Practical Training and System Construction of "Economic Law" Courses under the Demand-Oriented Innovation Entrepreneurship Talent Training funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lamberton, C.; Stephen, A. T. A Thematic Exploration of Digital, Social Media, and Mobile Marketing: Research Evolution from 2000 to 2015 and an Agenda for Future Inquiry. Journal of Marketing 2016, 80, 146–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, A.L.; Lepkowska-White, E. Social media marketing management: A conceptual framework. Journal of Internet Commerce 2018, 17, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, E.; Priporas, C.-V.; Migliano, G. Reshaping traditional marketing mix to include social media participation: Evidence from Italian firms. European Business Review 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutter, K.; Hautz, J.; Dennhardt, S. The impact of user interactions in social media on brand awareness and purchase intention: The case of MINI on Facebook. Journal of Product & Brand Management 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkmans, C.; Kerkhof, P.; Beukeboom, C.J. A stage to engage: Social media use and corporate reputation. Tourism Management 2015, 47, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkan, I.; Evans, C. Social media or shopping websites? The influence of eWOM on consumers’ online purchase intentions. Journal of Marketing Communications 2018, 24, 617–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tan, C.-H.; Sutanto, J. A media symbolism perspective on the choice of social sharing technologies. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 2018, 29, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Feng, Q. Social media marketing: A call for attention on the nature of marketing. Tsinghua Business Review 2017, 3, 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Scheel, C.; Eduardo, A.; Bello, B. Decoupling economic development from the consumption of finite resources using circular economy: A model for developing countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.; Onur, B.H. The green consumption effect: How using green products improves consumption experience. Journal of Consumer Research 2020, 47, 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. Research on the impact of green product logos and packaging environmental protection attributes on consumers' willingness to purchase green products. Doctoral dissertation,2018.

- Babutsidze, Z.; Chai, A. Look at me saving the planet! The imitation of visible green behavior and its impact on the climate value-action gap. Ecological Economics 2018, 146, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environmental Education Research 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershoff, A.D.; Frels, J.K. What makes it green? The role of centrality of green attributes in evaluation. Journal of Marketing 2015, 79, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottman, J.A.; et al. Avoiding green marketing myopia: Ways to improve consumer appeal for environmentally preferable products. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 2006, 48, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, M. What is social media. London: iCrossing, 2008.

- Chen, L.; Lee, J.; Wang, Y. Neural correlates of green consumption: An fMRI study on price premium acceptance. Journal of Marketing Research 2022, 59, 567–589. [Google Scholar]

- Laroche, M.; Bergero, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting precision in green marketing: Evidence from geo-located Twitter data. Journal of Interactive Marketing 2023, 58, 78–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, L. How user-generated content drives green trust: The role of social identity and peer influence. Journal of Retailing 2022, 98, 456–473. [Google Scholar]

- Godey, B.; Manthiou, A.; Pederzoli, D.; Rokka, J.; Aiello, G.; Donvito, R.; Wirtz, J. Social media marketing efforts of luxury brands: Influence on brand equity and consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research 2016, 69, 5833–5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.J.; Ko, E. Do social media marketing activities enhance customer equity? An empirical study of luxury fashion brand. Journal of Business Research 2016, 65, 1480–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmenner, R.W. How can service businesses survive and prosper? Sloan Management Review 1986, 27, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Naaman, M.; Becker, H.; Gravano, L. Hip and trendy: Characterizing emerging trends on Twitter. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 2011, 62, 902–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, H.; Naaman, M.; Gravano, L. Beyond trending topics: Real-world event identification on Twitter. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, F, 2011.

- Kim, S.; Park, G.; Lee, J. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of humorous appeals in green advertising. Journal of Advertising 2021, 50, 432–448. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Hsu, C. Humor sells: The neuroscience of entertainment in green ads. Journal of Consumer Neuroscience 2021, 18, 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley, C.; Tuten, T. Creative strategies in social media marketing: An exploratory study of branded social content and consumer engagement. Psychology & Marketing 2015, 32, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dessart, L.; Veloutsou, C.; Morgan-Thomas, A. Consumer engagement in online brand communities: A social media perspective. Journal of Product & Brand Management 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Merrilees, B. Interactive brand experience pathways to customer-brand engagement and value co-creation. Journal of Product & Brand Management 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hajli, N. Social commerce constructs and consumer’s intention to buy. International Journal of Information Management 2015, 35, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Benoit, S. Real-time interaction in green marketing: A dynamic systems approach. Journal of Marketing Communications 2023, 29, 145–163. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Hills, G.; Krueger, D. Creating shared value through green product co-creation. Harvard Business Review 2023, 101, 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Griskevicius, V.; Tybur, J.M.; Van den Bergh, B. Going green to be seen: Status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. Journal of Consumer Psychology 2023, 33, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B. A review of research on green consumption. Forest Ecology and Management 2014, 36, 178–189. [Google Scholar]

- Luchs, M.G.; Naylor, R.W.; Irwin, J.R.; Raghunathan, R. The Sustainability Liability: Potential Negative Effects of Ethicality on Product Preference. Journal of Marketing 2010, 74, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, J. Storytelling in green marketing: The role of narrative transportation. Psychology & Marketing 2023, 40, 901–918. [Google Scholar]

- Grewal, D.; Hulland, J.; Kopalle, P.K. The future of green marketing: Opportunities in sustainability-driven markets. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 2023, 51, 22–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, S.L.; Dowell, G. A resource-based view of green marketing strategies. Strategic Management Journal 2023, 44, 678–701. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, M.L.; Mende, M.; Bolton, L.E. Experiential green marketing: How immersive technologies drive sustainable consumption. Journal of Marketing 2022, 86, 56–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An approach to environmental psychology. Cambridge: MIT,1974.

- Ngai, E.W.; Tao, S.S.; Moon, K.K. Social media research: constructs, and conceptual frameworks. International journal of information management 2015, 35, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Feng, C. Branding with social media: User gratifications, usage patterns, and brand message content strategies. Computers in Human Bhavior 2016, 63, 868–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntinga, D.G.; Moorman, M.; Smit, E.G. Introducing COBRAs: Exploring motivations for brand-related social media use. International Journal of Advertising 2011, 30, 13–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.-T.; Oyunbazar, B.; Kang, T.-W. The Impact of Agricultural Food Retailers’ ESG Activities on Purchase Intention: The Mediating Effect of Consumer ESG Perception. Sustainability 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barger V,Peltier, J.W.; Schultz, D.E. Social media and consumer engagement: A review and research agenda. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeck, L.D.; Glynn, M.S.; Brodie, R.J. Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. Journal of Interactive Marketing 2014, 28, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, N.L.; Guillet, B.D. Investigation of social media marketing: how does the hotel industry in Hong Kong perform in marketing on social media websites? Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 2011, 28, 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, M.L.; Pires, G.D.; Rosenberger, I.I.I.P.J.; et al. Driving COBRAs: The power of social media marketing. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pichler, R.; Schade, M.; Kleine-Kalmer, B.; et al. Consumers’ online brand-related activities (COBRAs) on SNS brand pages: An investigation of consuming, contributing and creating behaviours of SNS brand page followers. European Journal of Marketing 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rohan, A.; Kalichera, V.D.; Milne, G.R. A mixed-method approach to examining brand-consumer interactions driven by social media. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, A.R. The influence of perceived social media marketing activities on brand loyalty: The mediation effect of brand and value consciousness. Aisa pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrigan, P.; Evers, U.; Miles, M.P.; et al. Customer engagement and the relationship between involvement, engagement, self-brand connection, and brand usage intentions. Journal of Business Research 2018, 88, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthiou, A.; Tang, L.R.; Bosselman, R. Factors and reactions: The dual range of the decision-making process on Facebook and news. Electronic Markets 2014, 54, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, R.; Rohm, A.; Crittenden, V.L. We’re all connected: The power of the social media ecosystem. Business Horizonss 2011, 54, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, L.; Gensler, S.; Leeflang, P.S. Popularity of brand posts on brand fan pages: An investigation of the effects of social media marketing. Journal of interactive marketing 2014, 26, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.L.; Pires, G.D.; Rosenberger, P.J.; et al. The role of consumer-consumer interaction and consumer-brand interaction in driving consumer engagement and behavioral intentions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, L.; Fernandes, T. Social media and sports efforts for engagement with football clubs on Facebook. Journal of Strategic Marketing 2018, 26, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallaugher, J.; Ransbotham, S. Social media and customer dialog management at Starbucks. MIS Quarterly Executive 2010, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Shin, H.; Burns, A.C. Examining the impact of luxury brand’s social media marketing on customer engagement: Using big data analytics and natural processing. Journal of Business Research 2021, 125, 815–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.; Swaminathan, V.; Brooks, G. Driving brand engagement through online social influencers: An empirical investigation of sponsored blogging campaigns. Journal of Marketing 2019, 83, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, O.; Skiera, B.; Barrot, C.; et al. Seeding strategies for marketing: An empirical comparison. Journal of marketing 2011, 75, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutter, K.; Hautz, J.; Dennhardt, S.; et al. The impact of user interactions in social media on brand awareness and purchase intention: the case of MINI on Facebook. Journal of Product & Brand Management 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Papadas, K.K.; Avlonitis, G.J.; Carrigan, M. Green marketing orientation: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. Journal of Business Research 2017, 80, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. Consumer attitude and purchase intention toward green energy brands: The roles of psychological benefits and environmental concern. Journal of Business Research 2012, 65, 1254–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

| Variable |

Question |

Code |

Survey Count |

| Entertainment |

Social media marketing content is enjoyable |

YYX1 |

4 |

| Social media marketing content is exciting |

YYX2 |

| Social media activities easily pass the time |

YYX3 |

| Social media activities easily pass the time |

YYX4 |

| Precision |

Recommends products I am interested in |

JZX1 |

4 |

| Recommends products based on my preferences |

JZX2 |

| Recommends products I want |

JZX3 |

| Captures my attention effectively |

JZX4 |

| Novelty |

Shares up-to-date information |

XYX1 |

4 |

| Shares trendy content |

XYX2 |

| Publishes creative video content |

XYX3 |

| Publishes novel video content |

XYX4 |

| Interactivity |

Enables information sharing |

HDX1 |

4 |

| Facilitates discussions and exchanges of opinions |

HDX2 |

| Makes it easy to express opinions |

HDX3 |

| Actively engages with audiences |

HDX4 |

| Green Marketing |

Enhances understanding of green environmental knowledge |

LSY1 |

10 |

| Promotes awareness of green consumption concepts |

LSY2 |

| Educates about green production technologies |

LSY3 |

| Educates about green product craftsmanship |

LSY4 |

| Provides access to green product information |

LSY5 |

| Adopts high-standard green production technologies |

LSY6 |

| Uses low-energy, pollution-free production processes |

LSY7 |

| Commits to high environmental standards |

LSY8 |

| Eco-friendly practices |

LSY9 |

| Healthy and environmentally conscious |

LSY10 |

| Green Premium Payment Willingness |

Willing to pay extra for green products |

YJZ1 |

4 |

| Worth purchasing despite higher prices |

YJZ2 |

| Plans to purchase in the future |

YJZ3 |

| Will recommend to friends |

YJZ4 |

Table 2.

| Demographics |

|---|

| Variable |

Group |

Frequency |

Ratio(%) |

| Gender |

Male |

158 |

45.8 |

| Female |

187 |

54.2 |

| Age |

≤ 22 years old |

39 |

11.3 |

| 23-30 years old |

145 |

42.03 |

| 31-40 years old |

106 |

30.72 |

| ≥ 41 years old |

55 |

15.94 |

| Occupation |

Student |

37 |

10.72 |

| Teacher |

78 |

22.61 |

| Freelancer |

122 |

35.36 |

| Corporate |

108 |

31.3 |

Daily Social

Media Usage |

≤ 2 hours |

86 |

24.93 |

| 3-4 hours |

151 |

43.77 |

| 5-6 hours |

72 |

20.87 |

| ≥ 7 hours |

36 |

10.43 |

Table 3.

| Cronbach's Alpha by Item |

|---|

| Variable |

Code |

Cronbach's Alpha if Item Deleted |

Cronbach's Alpha |

| Social Media Marketing |

Entertainment |

YYX1 |

0.899 |

0.916 |

| YYX2 |

0.883 |

| YYX3 |

0.895 |

| YYX4 |

0.889 |

| Precision |

JZX1 |

0.865 |

0.899 |

| JZX2 |

0.867 |

| JZX3 |

0.871 |

| JZX4 |

0.876 |

| Novelty |

XYX1 |

0.891 |

0.913 |

| XYX2 |

0.887 |

| XYX3 |

0.872 |

| XYX4 |

0.899 |

| Interactivity |

HDX1 |

0.888 |

0.919 |

| HDX2 |

0.893 |

| HDX3 |

0.901 |

| HDX4 |

0.897 |

| Green Marketing |

LSY1 |

0.931 |

0.937 |

| LSY2 |

0.929 |

| LSY3 |

0.933 |

| LSY4 |

0.927 |

| LSY5 |

0.932 |

| LSY6 |

0.931 |

| LSY7 |

0.929 |

| LSY8 |

0.928 |

| LSY9 |

0.929 |

| LSY10 |

0.932 |

Green Premium

Payment Willingness |

YJZ1 |

0.869 |

0.869 |

| YJZ2 |

0.862 |

| YJZ3 |

0.858 |

| YJZ4 |

0.877 |

Table 4.

| KMO and Bartlett's Tes |

|---|

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) |

0.930 |

| Bartlett's Test of Sphericity |

Approx. Chi-Square |

6780.060 |

| Degrees of Freedom |

435.000 |

| Significance |

0.000 |

Table 5.

| Total Variance Explained |

|---|

| Component |

Initial Eigenvalues |

Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings |

Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings (Varimax) |

| |

Total |

% of Variance |

Cumulative % |

Total |

% of Variance |

Cumulative % |

Total |

% of Variance |

Cumulative % |

| 1 |

11.071 |

36.903 |

36.903 |

11.071 |

36.903 |

36.903 |

6.500 |

21.665 |

21.665 |

| 2 |

3.735 |

12.449 |

49.352 |

3.735 |

12.449 |

49.352 |

3.211 |

10.703 |

32.368 |

| 3 |

2.182 |

7.274 |

56.625 |

2.182 |

7.274 |

56.625 |

3.200 |

10.665 |

43.034 |

| 4 |

1.872 |

6.239 |

62.864 |

1.872 |

6.239 |

62.864 |

3.132 |

10.441 |

53.475 |

| 5 |

1.756 |

5.853 |

68.717 |

1.756 |

5.853 |

68.717 |

3.119 |

10.396 |

63.871 |

| 6 |

1.608 |

5.360 |

74.077 |

1.608 |

5.360 |

74.077 |

3.062 |

10.206 |

74.077 |

| 7 |

0.549 |

1.831 |

75.908 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 8 |

0.545 |

1.816 |

77.724 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 9 |

0.518 |

1.725 |

79.450 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 10 |

0.469 |

1.562 |

81.012 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 11 |

0.425 |

1.415 |

82.427 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 12 |

0.420 |

1.401 |

83.828 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 13 |

0.401 |

1.337 |

85.165 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 14 |

0.372 |

1.241 |

86.406 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 15 |

0.358 |

1.193 |

87.599 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 16 |

0.350 |

1.168 |

88.767 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 17 |

0.337 |

1.124 |

89.891 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 18 |

0.316 |

1.053 |

90.944 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 19 |

0.307 |

1.023 |

91.968 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 20 |

0.295 |

0.985 |

92.953 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 21 |

0.289 |

0.962 |

93.914 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 22 |

0.262 |

0.873 |

94.787 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 23 |

0.233 |

0.776 |

95.563 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 24 |

0.225 |

0.749 |

96.313 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 25 |

0.213 |

0.711 |

97.024 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 26 |

0.209 |

0.697 |

97.721 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 27 |

0.183 |

0.611 |

98.331 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 28 |

0.180 |

0.601 |

98.932 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 29 |

0.162 |

0.540 |

99.472 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 30 |

0.158 |

0.528 |

100.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 6.

| Rotated Component Matrix |

|---|

| |

Component |

| |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

| YYX1 |

|

|

|

|

0.789 |

|

| YYX2 |

|

|

|

|

0.828 |

|

| YYX3 |

|

|

|

|

0.793 |

|

| YYX4 |

|

|

|

|

0.814 |

|

| JZX1 |

|

|

|

0.851 |

|

|

| JZX2 |

|

|

|

0.840 |

|

|

| JZX3 |

|

|

|

0.825 |

|

|

| JZX4 |

|

|

|

0.805 |

|

|

| XYX1 |

|

0.827 |

|

|

|

|

| XYX2 |

|

0.836 |

|

|

|

|

| XYX3 |

|

0.879 |

|

|

|

|

| XYX4 |

|

0.806 |

|

|

|

|

| HDX1 |

|

|

0.845 |

|

|

|

| HDX2 |

|

|

0.824 |

|

|

|

| HDX3 |

|

|

0.790 |

|

|

|

| HDX4 |

|

|

0.813 |

|

|

|

| LSY1 |

0.769 |

|

|

|

|

|

| LSY2 |

0.780 |

|

|

|

|

|

| LSY3 |

0.766 |

|

|

|

|

|

| LSY4 |

0.767 |

|

|

|

|

|

| LSY5 |

0.785 |

|

|

|

|

|

| LSY6 |

0.746 |

|

|

|

|

|

| LSY7 |

0.755 |

|

|

|

|

|

| LSY8 |

0.785 |

|

|

|

|

|

| LSY9 |

0.782 |

|

|

|

|

|

| LSY10 |

0.777 |

|

|

|

|

|

| YJZ1 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.797 |

| YJZ2 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.830 |

| YJZ3 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.814 |

| YJZ4 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.784 |

| Extraction Method:Principal Component Analysis. |

| Rotation Method:Varimax with Kaiser Normalization. |

| The rotation converged in 6 iterations. |

Table 7.

| Path Analysis Results |

|---|

| Path |

Estimate |

S.E. |

C.R. |

P |

Results |

| Entertainment → Green Marketing |

0.216 |

0.064 |

3.402 |

** |

Supported |

| Precision → Green Marketing |

0.133 |

0.630 |

2.112 |

0.035 |

Supported |

| Interactivity → Green Marketing |

0.188 |

0.610 |

3.098 |

0.002 |

Supported |

| Novelty → Green Marketing |

0.049 |

0.070 |

0.700 |

0.484 |

Not Supported |

| Entertainment → Green Premium Payment |

0.186 |

0.063 |

2.944 |

0.003 |

Supported |

| Precision → Green Premium Payment |

0.176 |

0.062 |

2.834 |

0.005 |

Supported |

| Interactivity → Green Premium Payment |

0.095 |

0.060 |

1.586 |

0.113 |

Not Supported |

| Novelty → Green Premium Payment |

0.212 |

0.069 |

3.055 |

0.002 |

Supported |

| Green Marketing → Green Premium Payment |

0.141 |

0.062 |

2.281 |

0.023 |

Supported |

| DF=390, X/DF=1.206, GFI=0.913, AGFI=0.896, CFI=0.988, NFI=0.933, RMSEA=0.026 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).