1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) continues to be the leading cause of death globally, with thrombotic events and endothelial dysfunction playing central roles in its pathophysiology [

1]. Despite the availability of several pharmacological interventions, a substantial proportion of patients remain at high residual risk due to mechanisms not fully addressed by conventional therapies, such as low-grade inflammation and platelet hyperreactivity. Thus, there is an ongoing need to explore new biological pathways and pharmacological targets that could complement or improve current cardiovascular treatments [

2].

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and its associated receptor family (EP1–EP4) are key regulators of vascular tone, inflammation, and platelet function [

3,

4]. Among these, the EP3 receptor has recently attracted attention for its unique role in promoting platelet aggregation and contributing to vasoconstriction and endothelial cell activation [

5,

6]. This G-protein-coupled receptor is expressed in multiple cardiovascular cell types, including endothelial cells and platelets, and mediates signaling events that favor a prothrombotic phenotype [

7]. However, the EP3 receptor has historically been understudied in comparison to EP2 and EP4, both of which are more widely investigated for their vasodilatory and anti-inflammatory effects in vascular biology [

8,

9].

Recent advances in chemical biology and computational drug discovery have provided new opportunities to explore EP3-targeted ligands, being useful for obesity and insulin resistance as well [

10,

11]. Modern screening approaches, such as virtual docking and pharmacophore modeling, allow for the rapid in silico evaluation of compound libraries. A previous study reported EP3 ligands such as misoprostol, L-798,106, and 9-D1t-PhytoP [

12]. Despite these technical advances, the field still lacks validated, selective EP3 ligands with clear in vitro activity in disease-relevant models [

13]. Moreover, the repurposing potential of existing compounds acting on EP3 has not been systematically investigated in cardiovascular contexts.

The present work builds upon this gap by proposing a computational-to-experimental pipeline to identify and validate novel EP3 ligands with potential utility in vascular therapy. We hypothesized that selected natural or clinically approved molecules could functionally activate EP3, producing measurable effects on key cardiovascular processes such as endothelial cell migration and platelet aggregation. To this end, we performed a (i) blind docking and (ii) high-throughput virtual screening of structurally diverse compound libraries, integrating ligand-based and structure-based approaches. A (iii) consensus from the obtained data was performed, promising candidates were further evaluated through ADME/Tox profiling and tested in (iv) biological assays using human endothelial cells and an ex vivo platelet model.

This study not only proposes a systematic strategy for EP3-targeted drug discovery but also provides novel insights into the cardiovascular roles of existing compounds, with direct implications for therapeutic repositioning. Together, these findings support the EP3 receptor as a valuable yet underexplored target in cardiovascular pharmacology.

Our results reveal several molecules—including taurocholic acid (TUCA), masoprocol (NOGA), and pravastatin—as potential EP3 ligands with relevant anti-migratory and antiaggregant properties.

2. Results

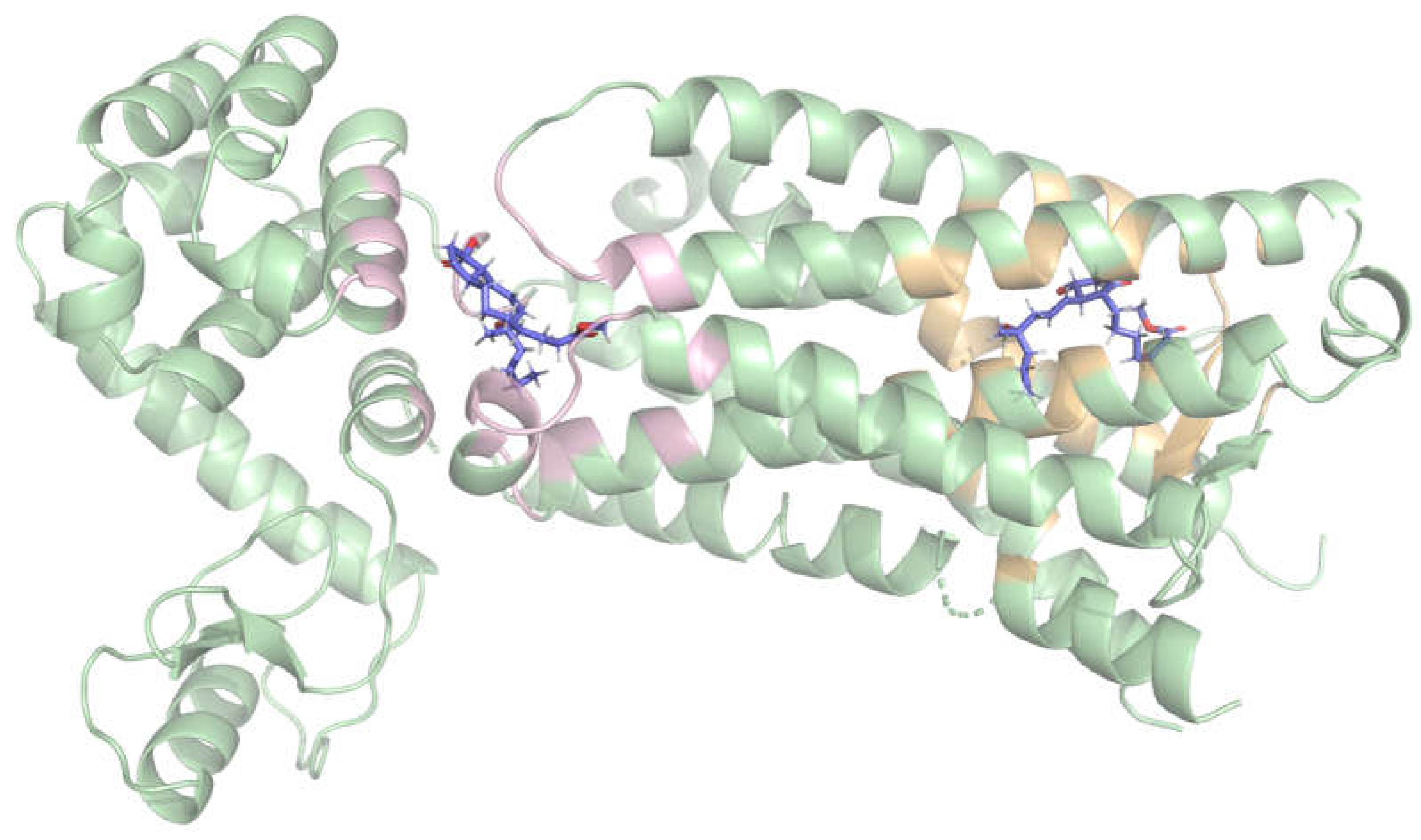

2.1. Blind Docking Revealed Two Distinct Potential Binding Sites on the EP3 Receptor

In order to detect potential binding hotspots beyond the predefined one and to compare them, an unrestricted (blind) docking was performed on the receptor surface. Three ligands were chosen for this technique: misoprostol, L-798,106, and 9-D1t-PhytoP. In all three cases, from the detected poses (

Table S1) two high-affinity binding regions (clusters) were consistently identified, with comparable docking scores on each case (

Figure 1):

The first binding region, which showed slightly better docking scores, was surrounded by the following residues: P55, M58, Q103, T106, T107, V110, F133, G141, T206, W207, L329, R333, S336, and Q339. This region corresponds to the extracellular side.

The second binding region was formed by residues K83, R84, S87, A158, Y165, A166, M169, T171, I1009, K1147, R1148, and A1160. This corresponds to the cytoplasmatic side.

These results suggest that the molecules may cross the membrane through this protein, which is consistent with the “transport” annotations [

14]. Based on its slightly higher docking scores and its relevance to extracellular ligand binding, only the first site was selected as the target region for subsequent structure-based virtual screening analyses.

2.2. Prediction of ligands by Virtual Screening

2.2.1. Selection of libraries

To obtain a fist set of results via screening, two compound libraries that contain known molecules were chosen: DrugBank, a database consisting of known drugs [

15], and FooDB, a database containing compounds present in food [

16]. These libraries were selected to explore both repurposing opportunities and natural product-based leads.

2.2.2. Ligand-Based Virtual Screening with LigandScout

For the ligand-based screening, up to two features were allowed to be omitted in the screening process, using a pharmacophoric model of misoprostol as the query. From the DrugBank database, with one feature allowed to be omitted, 10 candidate molecules emerged, including Beraprost, Alprostadil, Iopamidol and Misoprostol itself. With two features, the list expanded to 101 candidates. From the FooDB database, with one feature to be omitted, 17 molecules emerged, including Cyanidin 3-(caffeoyl glucoside), a flavonoid derivative. With two omitted features, the top-ranked hits from FooDB featured prostaglandin-like compounds.

2.2.3. Structure-Based Virtual Screening with LigandScout

The structure-based virtual screening was also performed allowing up to two omitted features. The query (pharmacophore model) was based on the EP3-misoprostol interaction in the previous docking step. From DrugBank, with no omitted pharmacophoric features, only Epoprostenol (a prostacyclin analog) was matched. By allowing for the omission of one pharmacophoric feature, Beraprost, Alprostadil, and Dinoprost were additionally identified. When two features were omitted, the number of potential hits increased to 19, including further prostaglandin derivatives. From FooDB, with zero or one omitted features, top hits were mainly prostaglandin derivatives. When allowing for two omitted features, more different hits emerged, like thromboxane-related molecules.

2.2.4. Structure-Based Virtual Screening with AutoDock Vina

The EP3 receptor structure was used for high-throughput docking using AutoDock Vina. From DrugBank, the top-ranked compounds (with binding scores around -12 kcal/mol) included several unnamed molecules. From FooDB, the results included Sesamolinol, Dolineone, and a series of glycosylated isoflavones such as acetyl-/malonyl- -daidzin/-genistin.

2.3. Consensus, QikProp and Compound Selection

In order to identify the most promising compounds, multiple criteria were taken into account. The table below shows the best overall compounds and their scores on all dockings (

Table 1). In order to choose compounds for experimental testing, several considerations were made, including existing literature about the compounds (especially if related to EP3), ADME/Tox predicted properties (to be more suitable as drugs) (

Table S2), commercial availabiliry and purchase price.

The molecules purchased for experimental testing included taurocholic acid (TUCA), hydrocortisone valerate, pravastatin sodium, and masoprocol (NOGA). The control molecules purchased were Iloprost, a stable prostaglandin I2 (PGI2) analog, and PGE2. Both are FDA-approved medications and known to have effects on platelets and endothelial cells.

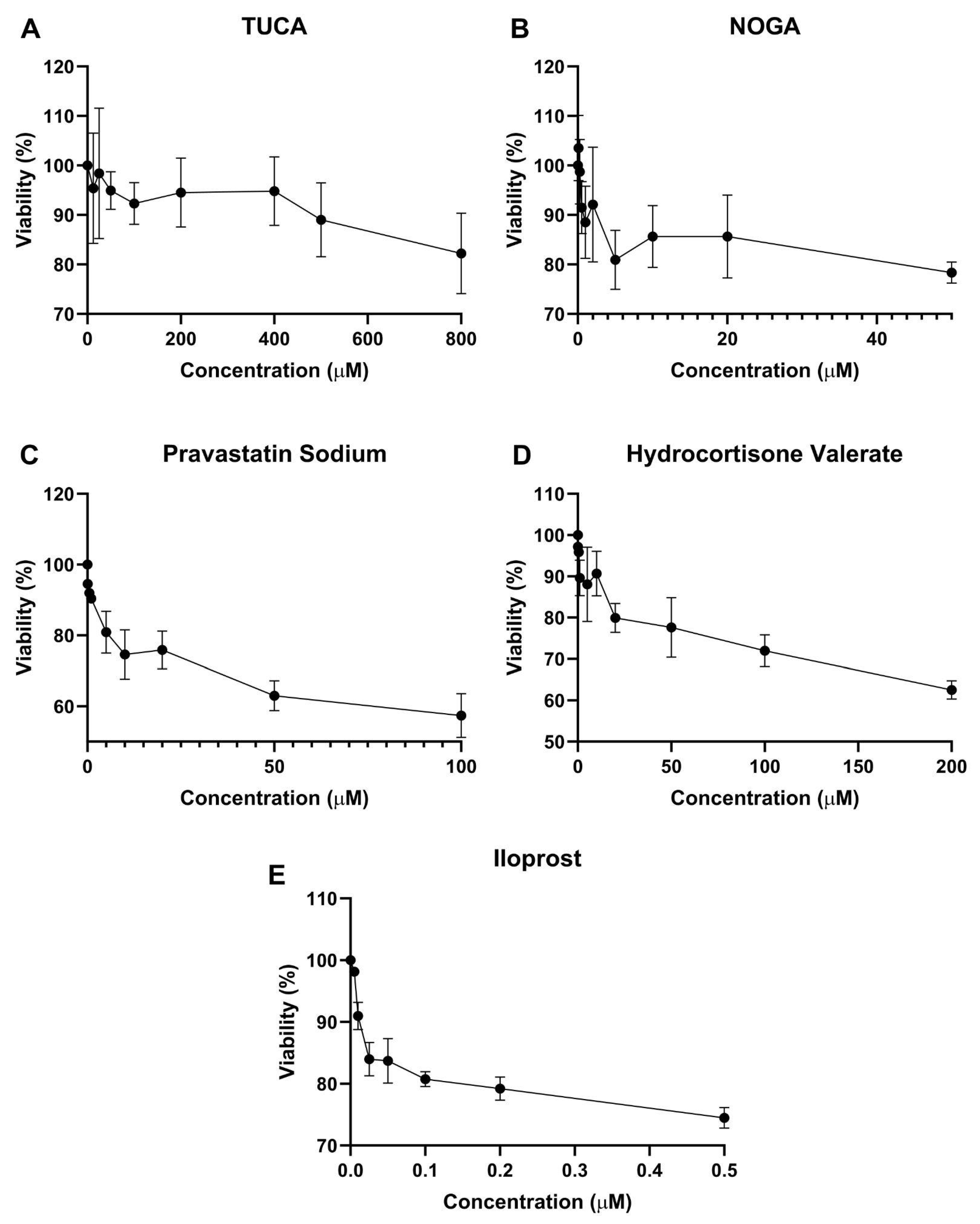

2.4. Cell Viability Assay

To assert the concentration ranges at which the compounds are not toxic to the cells, endothelial cells were treated with different concentrations and cell viability was tested using the MTT assay after 72h incubation. As shown in

Figure 2, maximal nontoxic concentration (above 80% cell viability) was found for 500 µM TUCA, 20 µM NOGA, 5 µM Pravastatin Sodium, and 20 µM Hydrocortisone valerate. Iloprost significantly decreased cell viability, and then 0.2 µM was used for further in vitro studies.

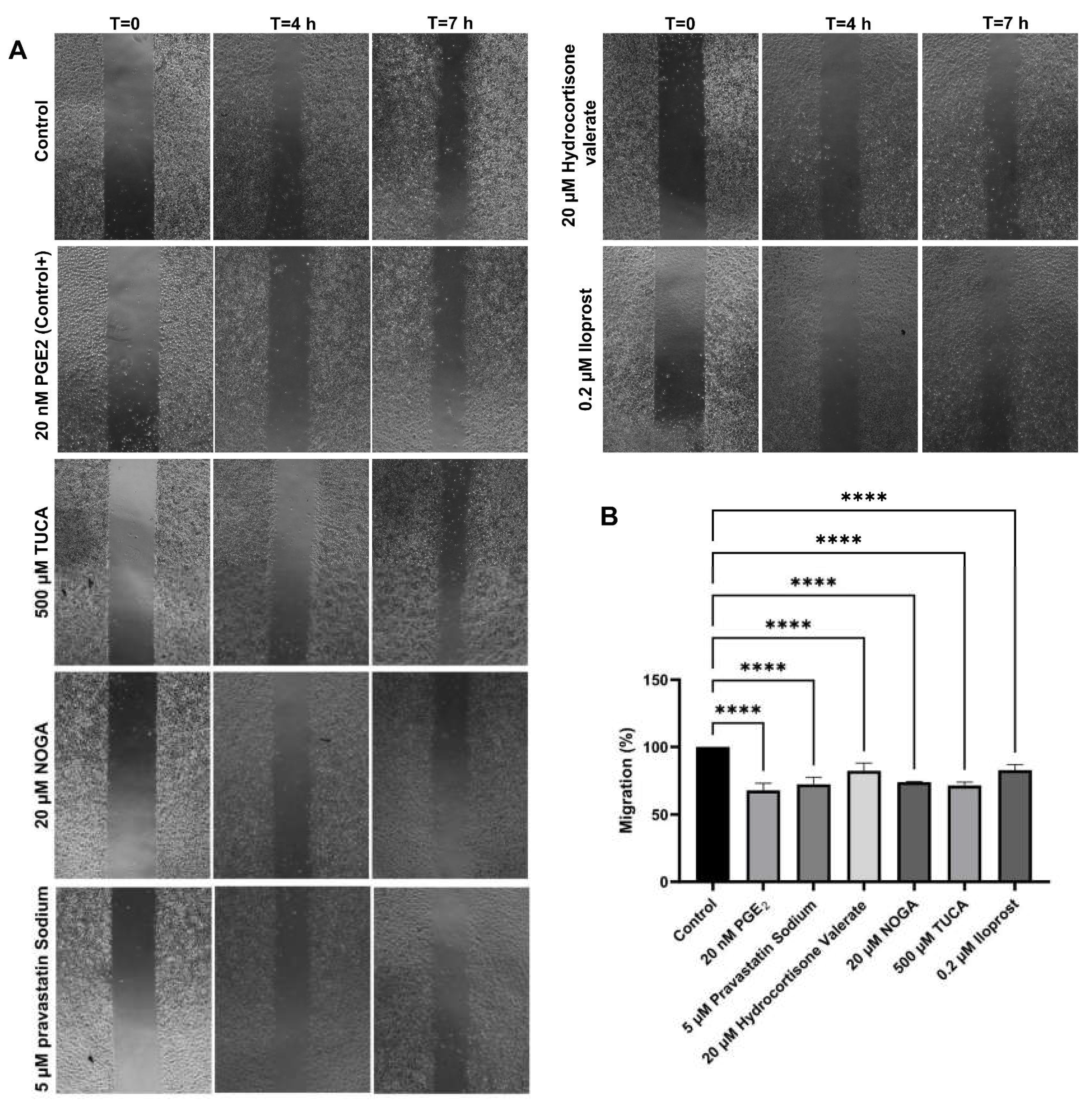

2.5. Cell Migration Assay

The migration capacity of endothelial cells in the presence of the selected EP3 ligands was detected by wound-healing. The positive control, 20 nM PGE2, showed the strongest inhibition of cell migration, which resulted in a 63% reduction of migration compared to baseline migration of non-treated cells. The results of the scratch assay also showed that the relative migration capacities of the cells were significantly decreased in the presence of 500 µM TUCA, 20 µM NOGA, 5 µM pravastatin Sodium and 20 µM Hydrocortisone valerate. The relative migration capacity was also found altered in the presence of 20 nM PGE2 (positive control) and 0.2 µM Iloprost (IP receptor analogue) (

Figure 3).

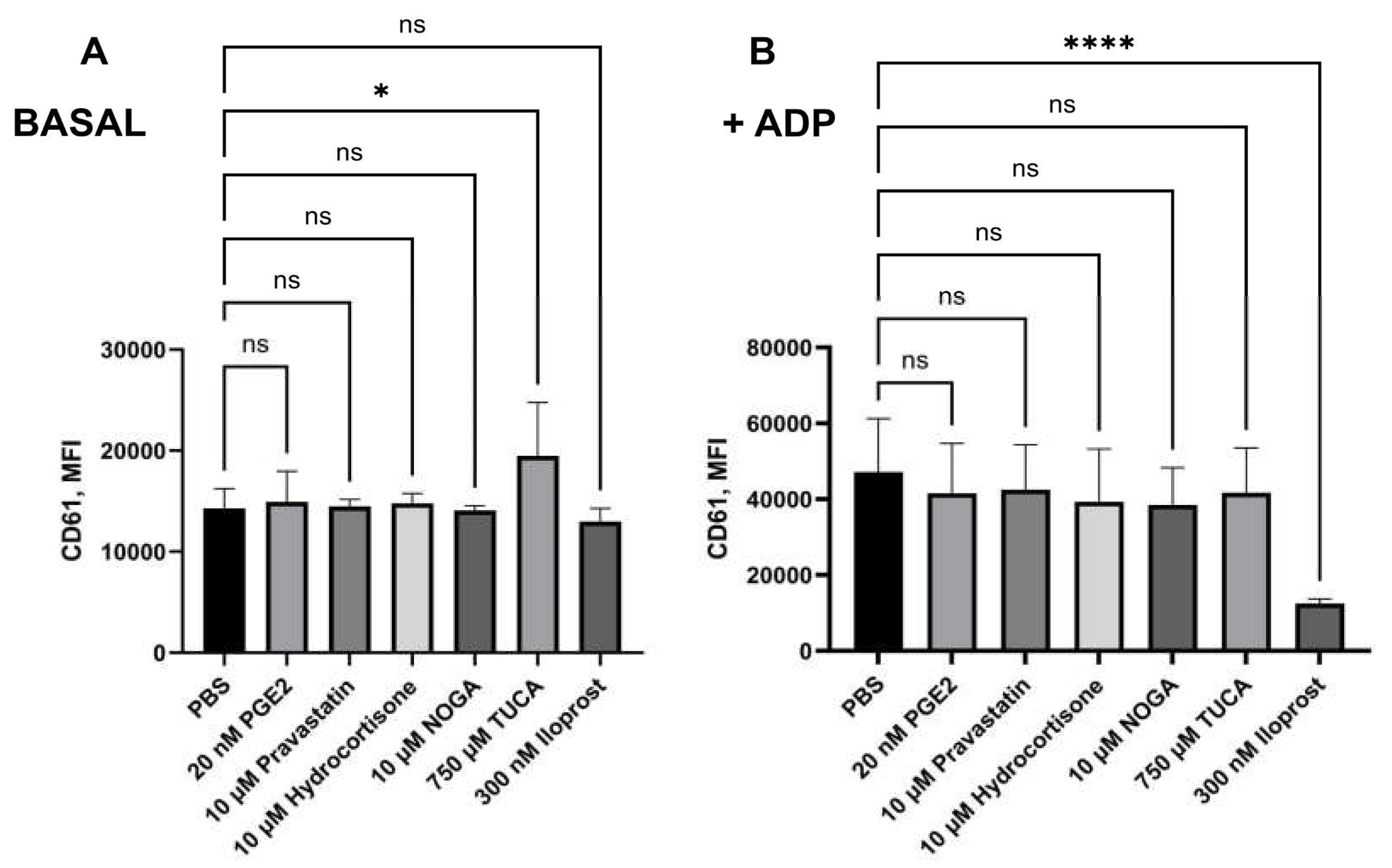

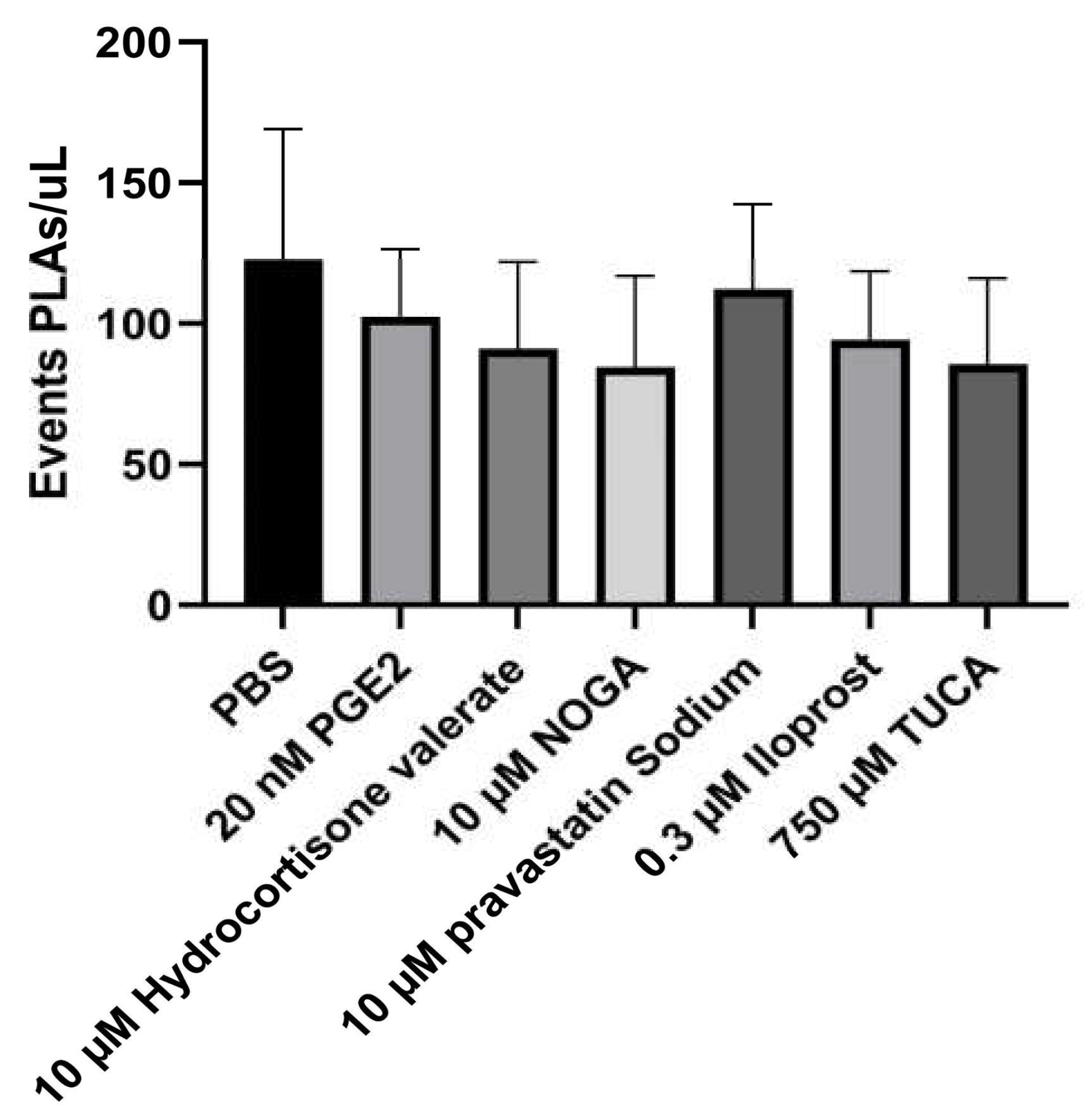

2.6. Platelet Activation and Leukocyte-Platelet-Aggregates Measurement Assay

We now incubated the potential EP receptor ligands for 10 min, in the presence of citrated whole blood in order to test their effects on platelet activation. Regarding CD61 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), only 750 µM TUCA was able to impair platelet aggregation in the absence of ADP (p= 0,0149). The presence of ADP increased platelet aggregation by its own, the preincubation of 20 nM PGE2, 10 µM NOGA, 10 µM Hydrocortisone valerate, 750 µM TUCA and 10 µM pravastatin Sodium did not significantly revert such effect. However, treatment with 300 nM Iloprost (IP3 inhibitor) was able to inhibit platelet aggregation (noted by a CD61 expression decrease) in the presence of ADP (p<0,0001,

Figure 4). Similar results were observed for CD61+ MPs, where CD61 expression levels were lower after ADP stimulation in the presence of iloprost (p<0.0001, data not shown). Regarding CD62P and AnV expression, none of the tested compounds were able to impair platelet activation (data not shown) in the presence or absence of ADP.

Hence, to decipher the individual contribution of each EP3 receptor ligand on the Platelet-Leukocyte aggregates (PLAs), the events/µL were measured using flow cytometry. The addition of none of the potential EP3 receptor ligands did not interfere with the number of PLA events (

Figure 5).

3. Discussion

3.1. Ligand Identification via Computational Screening

From the two sites identified in the blind docking, the extracellular one was already described in a previous work [

12] and used here for the screening, as it is the only one accessible to extracellular ligands. Although the intracellular site was not explored further in this study, future work could investigate it by performing a similar procedure of screening and experimental validation, followed by a comparative analysis with the results on the extracellular region.

In the virtual screenings performed with LigandScout, already known ligands [

17] were found among the top 20 hits, asserting the validity of the pharmacophorical models and screenings: Prostaglandin D2, Alprostadil and Dinoprost were in ligand-based; Gemeprost, Cloprostenol, Misoprostol (the query model), Alprostadil (again) and Bimatoprost were in structure-based. These hits reinforce the reliability of both approaches. Additionally, both also contained several other prostaglandin derivatives.

In the screening performed with AutoDock Vina, the top compounds included several unnamed molecules, but among the named ones were siramesine (a sigma-2 receptor ligand [

18]), sesamolinol (an antioxidant from sesame seeds [

19]), and Olinciguat (a soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator previously explored in cardiovascular trials [

20]). These findings indicate that the docking approach not only captured structurally related prostaglandins but also retrieved chemically diverse candidates with potential for repositioning.

Together, these in silico approaches not only yielded structurally diverse and pharmacologically plausible EP3 receptor ligands, but also enabled the rational selection of candidates for biological validation—described in the following section.

3.2. Biological Evaluation of Candidate Compounds

Building on the computational predictions, several compounds were selected for in vitro testing to evaluate their potential biological activity on key cardiovascular processes. These assays aimed to determine the influence of EP3-targeted ligands on endothelial cell migration, platelet aggregation, and platelet-leukocyte interactions, thereby validating their functional relevance.

The findings of this study indicate that these compounds may serve as modulators of cell migration and platelet function, through their potential interaction with the EP3 receptor. Several synthetic agonists and antagonists have been developed for the EP3 receptor. Whilst agonists are used to enhance platelet response [

12,

21], blocking EP3 ligands could decrease platelet or endothelial activation [

22,

23]. It is widely accepted that vascular prostaglandins, such as PGE2 and PGI2, play a role in the dual regulation (both enhancing and inhibiting) of cell migration through the involvement of EP3 and IP receptors, respectively [

4,

24]. PGE2 modulates angiogenesis, and 300 nM were found to promote endothelial cell migration [

12], however, in the current study 20 nM PGE2 hinders migration, as happened with the rest of the tested ligands. Iloprost, PGI2/prostacyclin analogue, has been shown to significantly reduce angiogenesis, although this effect was mediated through the IP receptor as CAY10449 was able to reverse this inhibition [

25]. From the current data, it is concluded that the prostacyclin mimetic iloprost could synergistically inhibit vascular cell migration, depending on a Gs-mediated increase of intracellular cAMP (IP receptor agonist and EP3 antagonist), as it could also potentially fit within the EP3 context. Iloprost has been shown to mediate vasodilatory functions via the EP4 receptor [

26], its potential binding to EP3 receptor is an unrecognized mechanism, and illustrates that the EP3 receptor may be a novel therapeutic approach for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Several papers investigate the effect of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibition through statins on angiogenesis in vitro [

27,

28]. They were able to demonstrate proangiogenic effects at low range concentrations and angiostatic effects at high-dose [

27]. In these articles, the mechanisms behind this dual and dose-dependent effect were not attributed, which makes our study even more significant, as it is the first to link the use of pravastatin with the inhibition of the EP3 receptor. On the other hand, the potent antiangiogenic action of glucocorticoids, such as hydrocortisone, is mainly due to VEGF and/or prostaglandin inhibition [

29]. In the present study, we found that hydrocortisone valerate could be interfering with the prostanoid receptor EP3 under basal conditions. This finding is particularly interesting, as there is no prior data available regarding this interaction. Bile acids have been postulated to regulate endothelial metabolism, as protective molecules [

30,

31]. Taurocholic acid (TUCA), a bile acid, has been shown to reduce endothelial migration of choroidal cells in vitro and potential reduction in potential neovascularization [

32]. Conversely, platelets showed inhibited responses to thrombin activation in the presence of bile acids [

33], in addition to increased fibrinolysis [

34]. As of yet, the mechanism through which this inhibition could occur has not been understood. The fact that TUCA could be a potential ligand for the EP3 receptor may shed light on these current and previous findings.

The compounds selected for in vitro testing are clinically applied compounds such as pravastatin, hydrocortisone and iloprost. Our study has found affinity for the EP3 receptor pocket, and given their clinical use, it is important to define their repositioning effects. Previous studies found that hydrocortisone administration had no significant influence on expression of CD62P, with and without ADP stimulation [

35,

36]. In line with previous results, our study suggests that hydrocortisone mediates endothelial migration without the activation of platelet function. Elevated PLA levels are linked to various acute and chronic thrombo-inflammatory conditions, including CVD [

37]. Therefore, they appear to be promising candidates for use as biomarkers in monitoring antiplatelet therapy. Interestingly, several bioactive compounds such as gallic acids, anthocyanins influence PLA percentage. However, there is only one previous study investigating a food-derived compound (phytoprostane) because of its ability to bind the EP3 receptor [

12]. When monitoring platelet function, PLA has proven to be significantly sensitive; however, the PLA levels did not change in blood from healthy populations after adding tirofiban and ADP or TRAP [

31]. Here PGE2 decreased platelet reactivity in response to ADP but had no effect on the levels of PLAs either, indicating the absence of platelet response to these compounds or the lack of sensitivity for the PLA measurement.

Understanding the application of the EP3 receptor clinical drugs -already used for other indications- can open the door to several interesting opportunities, especially in the context of drug repositioning and understanding side effects in various physiological and pathological processes. In contrast to previous findings [

12], in our study, EP3 receptor potential ligands had no significant effect on platelet reactivity but decreased the migration of endothelial cells. The mechanism underlying such relative effects, in turn, could be associated with the binding to the “pro-angiogenic” EP3 receptor as an antagonist.

Our observation allows us to speculate that the modulation of endothelial function might be one of the mechanisms underlying the beneficial effect of EP3 receptor ligands in a pathological context. Collectively, these findings suggest that EP3 receptor modulation can influence both angiogenic and inflammatory pathways, highlighting its therapeutic promise in cardiovascular disease. This dual functionality reinforces the relevance of EP3 as a pharmacological target and opens the door for repurposing clinically available agents as part of novel cardiovascular interventions.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Blind Docking

As the first step in the identification of novel EP3 receptor ligands, a blind molecular docking approach was employed to explore potential ligand-binding sites and assess interaction propensities in an unbiased manner. This allows for the systematic prediction of binding poses and affinities across the receptor surface, without prior assumptions about specific active sites, and offers a rational entry point to evaluate ligand compatibility and to guide the design of subsequent virtual screening and pharmacological assays.

The crystal structure of the human EP3 receptor (PDB ID: 6M9T) was prepared by removing crystallographic ions using PyMOL [

38], followed by the assignment of Gasteiger charges [

39] in AutoDock Tools [

40]. The receptor was then saved in PDBQT format for docking calculations.

Three previously reported EP3 ligands [

12]—misoprostol (CID 5282381), L-798,106 (CID 15551229), and 9-D1t-PhytoP (CID 126457309)—were downloaded from PubChem [

41] for comparison in the docking results. Ligand structures were processed and converted using MetaScreener to ensure compatibility with the docking pipeline. Blind docking (BD) simulations [

42] were carried out with AutoDock Vina [

43] though the MetaScreener suite [

44]. Default settings were used to maximize reproducibility and computational efficiency. The resulting binding poses were clustered based on the distribution of docking scores, providing an estimation of binding affinities and enabling structural grouping of potential binding modes. To further investigate receptor–ligand interactions, the Protein–Ligand Interaction Profiler [

45] was applied to the top-ranked complexes. This analysis facilitated the identification of key binding site residues and interaction types, which provided useful information in order to prepare the pharmacophoric models in the screening step.

4.2. Virtual Screenings

Virtual screening (VS) techniques can use the information about a ligand (ligand-based) or its interaction with a desired target (structure-based) in order to predict other molecules that may have the same properties. For the prediction of potential drug candidates, VS was performed against DrugBank (version 5.1.4) and FooDB (version pre-1.0) libraries. Various approaches were used in order to provide better results:

With LigndScout, ligand-based screening (using the pharmacophoric model of misoprostol) and structure-based screening (using the interactions between misoprostol and EP3).

With AutoDock Vina, a structure-based screening by restricted docking (scoring different poses of the ligand in the chosen region and comparing to other molecule’s scores).

Next, a consensus was performed to cohere all approaches.

4.2.1. LigandScout

The libraries used were converted using idbgen, command available as part of LigandScout [

46,

47] and saved in ldb format. The targets were prepared using LigandScout’s GUI, and saved in pmz format. For the ligand-based approach, the pharmacophoric model for misoprostol was generated after selecting the pose with minimal energy, and for the structure-based approach, the pharmacophorical model for the interaction of misoprostol with the EP3 receptor was used alongside the interaction details from the docking results. For each of those approaches, screenings were performed using MetaScreener and varying the number of features to be omitted (from 0 to 2). For each approach and number of omitted features, a table containing all compounds with their scores and rank was automatically generated.

4.2.2. AutoDock Vina

The libraries were prepared using AutoDockTools’ prepare_receptor4.py, saved in pdbqt format. The receptor used was the same as in the blind docking step. Virtual Screening was performed on the previously identified region of the EP3 receptor for both libraries using AutoDock Vina through MetaScreener’s scripts, also employing default parameters to maximize efficiency. A table containing all compounds with their scores and rank was automatically generated.

4.3. Consensus and Other Metrics

Combining the data of different VS techniques can provide overall better results [

48]. For this, the results of all screening techniques were joined into a single table, and reordered favoring compounds with higher ranks (top hits) on any screening and compounds with good scores among all screenings. Additional data such as existing evidence in literature about their targets or ADME/Tox properties was obtained for some compounds. After deliberation, we selected compounds available in stock from different vendors for experimental validation.

ADME/Tox properties were predicted using Maestro’s QikProp [

37], using default settings.

4.4. Cell Culture and Drugs

Human endothelial cell line (EAhy926) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD). The cell line was cultivated in high glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 50 U/ml penicillin and 50 µg/ml streptomycin (Sigma Aldrich Chemical Co., USA) in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% humidified air at 37°C. Subculture was performed when 90% confluence was obtained.

Nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NOGA, Masoprocol), Hydrocortisone Valearate, Pravastatin Sodium, Sodium Taurocholate (TUCA) and PGE2 were purchased via Molport (Letonia) dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich) up to 100 mM and stored at −20°C.

4.5. Cell Viability Assay

Exponentially growing cells were plated in triplicate in flat-bottomed 96-well plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) at 2000 cells/well. The day after, drugs were added in serial dilution at distinct concentrations. Control wells contained medium without drug plus 0.1% DMSO. Plates were incubated for 3 days in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator and assayed for cell viability.

30 µL/well of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT, Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (final concentration 1.9 mg/ml, pH 7.4) was added to the cells. After incubation at 37°C for 4 h, the unreacted dye was aspirated. The formazan crystals were dissolved in 200 µL DMSO for 30 min and the absorbance was read at a wavelength of 570 nm (test) and 690 nm (reference) in a microtitre plate reader (SpectraMax I3, Molecular Devices). Results were calculated as:

All the experiments were run three times.

4.6. Cell Migration Assay (Wound Healing Assay)

Cell migration was studied by performing wound healing assay. Human endothelial cells (80,000 cells) were plated in low 35-mm-dishes with culture inserts (Ibidi, Martinsried, Germany) in the presence of 10% FBS. After appropriate cell attachment for 24 h, inserts were then removed with sterile forceps to create a wound field of approximately 500 µm, according to the manufacturer protocol. Confluent cells were incubated with the following treatments: 20 µM NOGA, 0.75 mM TUCA, 5 µM Pravastatin sodium, 20 µM Hydrocortisone valerate and 0.2 µM Iloprost. Control dishes were incubated in the presence of 0.1% DMSO and 20 nM PGE2. Cells were then allowed to migrate in a cell culture incubator for 24h. At 0, 4, 7 and 24 h (linear growth phase), 10 fields of the injury area were photographed with an inverted and phase contrast microscopy at x10 magnification. For each timepoint, the area uncovered by cells was determined by analysis with the ImageJ software program. All experiments were repeated three times.

The migration speed of the wound closure is given as the percentage of the recovered area at each time point, relative to the initially covered area (0 h). The velocity of wound closure (%/h) was calculated according to the formula:

with slopes are then expressed as percentages relative to control conditions.

4.7. Ex vivo Assessment of Platelet Activation and Platelet-Leukocyte-Aggregates (PLAs)

Six healthy participants (without any treatment) were recruited among the staff of the Catholic University of Murcia (UCAM), after the UCAM Research Ethics Committee approval (CE02208). Fresh blood samples were collected in commercial 2 mL sodium citrate (32%) and EDTA Vacutainer tubes using a 20-gauge needle. The blood extractions were performed in accordance with the Helsinki declaration and participants provided written informed consent.

Selected ligands were dissolved in PBS up to 1 mM and then added to 150 µL of fresh citrated blood at 20 nM PGE2, 10 µM NOGA, 0.75 mM TUCA, 10 µM Pravastatin sodium, 10 µM Hydrocortisone valerate and 0.3 µM Iloprost for 10 min, followed by platelet activation marker analysis by flow cytometry (FCM). After incubation with EP receptor ligands for 10 min, whole blood (25 µL) was stimulated with adenosine-50-diphosphate (ADP, 0.02 mmol/L; Biodata Corporation, Horsham, PA, USA) for 2 min. Later, whole blood was labeled with mouse–anti-human CD61-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), mouse–anti-human CD62P-BV786 and mouse–anti-human CD42b-allophycocyanin (APC) (all from BD Biosciences, Oxford, UK) for 15 min, diluted with 1 mL of filtered PBS and then analyzed in a FACS Celesta flow cytometer (BD, Becton Dickinson, Oxford, UK) as already published [

12,

49].

Selected ligands were then added to 50 µL of fresh EDTA anticoagulated whole blood for 10 min. Mouse antihuman monoclonal fluorochrome-conjugated antibody anti-CD14-PE and CD42b-BUV395 were mixed with 50 µL of stimulated whole blood in TruCount tubes (all from BD). After incubation for 15 min of incubation, red blood cells were lysed by 450 µL of ACK (Ammonium-Chloride-Potassium) lysing solution (BD, Oxford, UK) for 15 min, followed by dilution in 1 mL of PBS and immediate flow cytometric analysis. Monocytes and other polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) were selected by gating strategies based on forward and side scatter to select monocytes and side scatter versus CD14 expression to exclude granulocytes (some lymphocytes and neutrophiles might be included in this gate too) [

12]. Absolute counts of CD14+ leukocytes (in cells per microliter) were obtained by calculating the number of gated events proportional to the number of the count beads according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. CD14+ platelet-leukocyte–aggregates (PLAs) were defined as events positive to CD14 and the platelet marker CD42b [

50]. Isotype controls for all the FCM assays were performed with different monoclonal anti-IgG1 (BD Biosciences).

4.8. Data Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Data were analyzed for statistical differences by the Student’s t-test for paired and unpaired data after testing for normal distribution of the data. For in vitro/ex vivo experiments, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed followed by a Tukey post hoc test to compare each group. Differences were considered significant at an error probability of p < 0.05. SPSS 22.0 software was used for the rest of statistical analyses (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the successful integration of computational and experimental strategies to identify novel EP3 receptor ligands with potential therapeutic applications in CVD. Ligand-based and structure-based virtual screening approaches, supported by the MetaScreener suite, enabled the prioritization of lead compounds with high docking scores and favorable predicted pharmacokinetic profiles. Experimental validation confirmed the biological relevance of the in silico predictions. Several compounds exhibited significant bioactivity in endothelial and platelet-based assays. Among these, TUCA, masoprocol, hydrocortisone and pravastatin sodium emerged as the most effective candidates, supporting the role of EP3 modulation as a viable cardiovascular strategy.

TUCA, in particular, demonstrated the strongest antimigratory activity, consistently outperforming other compounds in reducing endothelial cell migration. These results highlight its potential as a lead molecule, though further studies are required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of action. In the context of platelet function, only TUCA platelet aggregation in basal conditions, although reductions in CD61 and CD62P expression levels were not found in other conditions nor ADP stimulation.

These findings support the hypothesis that EP3 ligands may play a broader role in modulating vascular inflammation. The combined in silico and in vitro workflow not only streamlined candidate selection but also produced high-affinity ligands with minimal predicted off-target effects, reinforcing the need for subsequent pharmacodynamic and in vivo studies to advance these candidates toward clinical translation.

Finally, the study highlights the dual potential for both drug repurposing and novel ligands development. Together, these findings open promising avenues for structure–activity relationship studies and the rational design of next-generation EP3-targeted therapeutics.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. Top-ranked blind docking poses of misoprostol; Table S2: Predicted ADME/Tox properties.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, JR.AF., S.MG. and H.PS.; data curation, JR.AF.; formal analysis, JR.AF.; funding acquisition, H.PS.; investigation, JR.AF., S.MG., A.CS. and H.PS.; methodology, S.MG.; project administration, S.MG. and H.PS.; resources, A.P., A.CS. and H.PS.; software, JR.AF. and M.CB.; supervision, H.PS.; validation, H.PS.; visualization, JR.AF., S.MG., A.CS. and H.PS.; writing - original draft, JR.AF., S.MG. and H.PS.; writing - review and editing, JR.AF. and H.PS.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study formed part of the AGROALNEXT programme and was supported by MCIN with funding from European Union NextGenerationEU (PRTR-C17.I1) and by Fundación Séneca with funding from Comunidad Autónoma Región de Murcia (CARM); This research was funded through the Project NEOAGONCAR (nuevos agonistas del receptor EP3 para el tratamiento y la prevención cardiovascular), by GOURA INVESTIGACIONES, A.I.E. and its participants, under the call “Financiación estructurada de proyectos de I+D por Agrupaciones de Interés Económico (A.I.E.)”, in collaboration with INVENTIUM.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of UCAM - Universidad Católica San Antonio de Murcia (CE02208).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

Powered@NLHPC: This research was partially supported by the supercomputing infrastructure of the NLHPC (CCSS210001); During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT for the purposes of helping in the style of the redaction of the article. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADME/Tox |

Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion / Toxicity |

| GUI |

Graphical User Interface |

| TUCA |

Taurocholic Acid |

| CVD |

Cardiovascular Disease |

| PGE2 |

Prostaglandin E2 |

| NOGA |

Nordihydroguaiaretic acid (Masoprocol) |

| MTT |

Thiazolyl Blue Tetrazolium Bromide |

| PLA |

Leukocyte-Platelet Aggregate |

| EDTA |

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| PGI2 |

Prostaglandin I2 |

| HMG-CoA |

Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA |

| FBS |

Fetal bovine serum |

| DMSO |

Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| PBS |

Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PMN |

Polymorphonuclear leukocytes |

References

- Mahmood, S.S.; Levy, D.; Vasan, R.S.; Wang, T.J. The Framingham Heart Study and the Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Disease: A Historical Perspective. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2014, 383, 999–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, G.D. New Targets for Antithrombotic Medications: Seeking to Decouple Thrombosis from Hemostasis. J. Thromb. Haemost. JTH 2024, S1538-7836(24)00723-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, S.; Tilly, P.; Hentsch, D.; Vonesch, J.-L.; Fabre, J.-E. Vascular Wall-Produced Prostaglandin E2 Exacerbates Arterial Thrombosis and Atherothrombosis through Platelet EP3 Receptors. J. Exp. Med. 2007, 204, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrucci, G.; De Cristofaro, R.; Rutella, S.; Ranelletti, F.O.; Pocaterra, D.; Lancellotti, S.; Habib, A.; Patrono, C.; Rocca, B. Prostaglandin E2 Differentially Modulates Human Platelet Function through the Prostanoid EP2 and EP3 Receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2011, 336, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawhin, M.-A.; Tilly, P.; Fabre, J.-E. The Receptor EP3 to PGE2: A Rational Target to Prevent Atherothrombosis without Inducing Bleeding. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2015, 121, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.C.; May, J.A.; Johnson, A.; Hermann, D.; Strieter, D.; Hartman, D.; Heptinstall, S. Effects on Platelet Function of an EP3 Receptor Antagonist Used Alone and in Combination with a P2Y12 Antagonist Both In-Vitro and Ex-Vivo in Human Volunteers. Platelets 2013, 24, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Anderson, P.J.; Rajagopal, S.; Lefkowitz, R.J.; Rockman, H.A. G Protein-Coupled Receptors: A Century of Research and Discovery. Circ. Res. 2024, 135, 174–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasterk, L.; Philipose, S.; Eller, K.; Marsche, G.; Heinemann, A.; Schuligoi, R. The EP3 Agonist Sulprostone Enhances Platelet Adhesion But Not Thrombus Formation Under Flow Conditions. Pharmacology 2015, 96, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, T.D.; Harding, P. Prostaglandin E2 EP Receptors in Cardiovascular Disease: An Update. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022, 195, 114858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaid, M.D.; Wisinski, J.A.; Kimple, M.E. The EP3 Receptor/Gz Signaling Axis as a Therapeutic Target for Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. AAPS J. 2017, 19, 1276–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaid, M.D.; Harrington, J.M.; Kelly, G.M.; Sdao, S.M.; Merrins, M.J.; Kimple, M.E. EP3 Signaling Is Decoupled from the Regulation of Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion in β-Cells Compensating for Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Islets 2023, 15, 2223327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoro-García, S.; Martínez-Sánchez, S.; Carmena-Bargueño, M.; Pérez-Sánchez, H.; Campillo, M.; Oger, C.; Galano, J.-M.; Durand, T.; Gil-Izquierdo, Á.; Gabaldón, J.A. A Phytoprostane from Gracilaria Longissima Increases Platelet Activation, Platelet Adhesion to Leukocytes and Endothelial Cell Migration by Potential Binding to EP3 Prostaglandin Receptor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilly, P.; Charles, A.-L.; Ludwig, S.; Slimani, F.; Gross, S.; Meilhac, O.; Geny, B.; Stefansson, K.; Gurney, M.E.; Fabre, J.-E. Blocking the EP3 Receptor for PGE2 with DG-041 Decreases Thrombosis without Impairing Haemostatic Competence. Cardiovasc. Res. 2014, 101, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annotations: 6M9T. Available online: https://www.rcsb.org/annotations/6M9T#membrane-protein-annotations (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Wishart, D.S.; Feunang, Y.D.; Guo, A.C.; Lo, E.J.; Marcu, A.; Grant, J.R.; Sajed, T.; Johnson, D.; Li, C.; Sayeeda, Z.; et al. DrugBank 5.0: A Major Update to the DrugBank Database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D1074–D1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FooDB. Available online: https://foodb.ca/ (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Prostaglandin E2 Receptor EP3 Subtype | DrugBank Online. Available online: https://go.drugbank.com/bio_entities/BE0002375 (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Zeng, C.; Rothfuss, J.M.; Zhang, J.; Vangveravong, S.; Chu, W.; Li, S.; Tu, Z.; Xu, J.; Mach, R.H. Functional Assays to Define Agonists and Antagonists of the Sigma-2 Receptor. Anal. Biochem. 2014, 448, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osawa, T.; Nagata, M.; Namiki, M.; Fukuda, Y. Sesamolinol, a Novel Antioxidant Isolated from Sesame Seeds. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1985, 49, 3351–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, D.P.; Shea, C.M.; Tobin, J.V.; Tchernychev, B.; Germano, P.; Sykes, K.; Banijamali, A.R.; Jacobson, S.; Bernier, S.G.; Sarno, R.; et al. Olinciguat, an Oral sGC Stimulator, Exhibits Diverse Pharmacology Across Preclinical Models of Cardiovascular, Metabolic, Renal, and Inflammatory Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabre, J.E.; Nguyen, M.; Athirakul, K.; Coggins, K.; McNeish, J.D.; Austin, S.; Parise, L.K.; FitzGerald, G.A.; Coffman, T.M.; Koller, B.H. Activation of the Murine EP3 Receptor for PGE2 Inhibits cAMP Production and Promotes Platelet Aggregation. J. Clin. Invest. 2001, 107, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Zeller, W.; Zhou, N.; Hategan, G.; Mishra, R.K.; Polozov, A.; Yu, P.; Onua, E.; Zhang, J.; Ramírez, J.L.; et al. Structure-Activity Relationship Studies Leading to the Identification of (2E)-3-[l-[(2,4-Dichlorophenyl)Methyl]-5-Fluoro-3-Methyl-lH-Indol-7-Yl]-N-[(4,5-Dichloro-2-Thienyl)Sulfonyl]-2-Propenamide (DG-041), a Potent and Selective Prostanoid EP3 Receptor Antagonist, as a Novel Antiplatelet Agent That Does Not Prolong Bleeding. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Zeller, W.; Zhou, N.; Hategen, G.; Mishra, R.; Polozov, A.; Yu, P.; Onua, E.; Zhang, J.; Zembower, D.; et al. Antagonists of the EP3 Receptor for Prostaglandin E2 Are Novel Antiplatelet Agents That Do Not Prolong Bleeding. ACS Chem. Biol. 2009, 4, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blindt, R.; Bosserhoff, A.-K.; vom Dahl, J.; Hanrath, P.; Schrör, K.; Hohlfeld, T.; Meyer-Kirchrath, J. Activation of IP and EP(3) Receptors Alters cAMP-Dependent Cell Migration. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 444, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Womack, T.R.; Li, J.; Govyadinov, P.A.; Mayerich, D.; Eriksen, J.L. Prostacyclin as a Negative Regulator of Angiogenesis in the Neurovasculature 2021, 2021.04.28.441854.

- Lai, Y.-J.; Pullamsetti, S.S.; Dony, E.; Weissmann, N.; Butrous, G.; Banat, G.-A.; Ghofrani, H.A.; Seeger, W.; Grimminger, F.; Schermuly, R.T. Role of the Prostanoid EP4 Receptor in Iloprost-Mediated Vasodilatation in Pulmonary Hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 178, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, M.; Heeschen, C.; Glassford, A.J.; Cooke, J.P. Statins Have Biphasic Effects on Angiogenesis. Circulation 2002, 105, 739–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, S.Y.; Park, S.; Kim, H.; Lee, S.-J.; Jang, W.-S.; Kim, M.-J.; Lee, S.; Jang, W.I.; Kim, A.R.; Kim, E.H.; et al. Atorvastatin Inhibits Endothelial PAI-1-Mediated Monocyte Migration and Alleviates Radiation-Induced Enteropathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logie, J.J.; Ali, S.; Marshall, K.M.; Heck, M.M.S.; Walker, B.R.; Hadoke, P.W.F. Glucocorticoid-Mediated Inhibition of Angiogenic Changes in Human Endothelial Cells Is Not Caused by Reductions in Cell Proliferation or Migration. PloS One 2010, 5, e14476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, E.; Lettlova, S.; Jomard, A.; Wasilewski, G.; Osto, E. Bile Acids Promote Endothelial Cell Homeostasis via the Regulation of Cell Metabolism and Quiescence. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, ehad655.3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taoka, H.; Yokoyama, Y.; Morimoto, K.; Kitamura, N.; Tanigaki, T.; Takashina, Y.; Tsubota, K.; Watanabe, M. Role of Bile Acids in the Regulation of the Metabolic Pathways. World J. Diabetes 2016, 7, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warden, C.; Barnett, J.M.; Brantley, M.A. Taurocholic Acid Inhibits Features of Age-Related Macular Degeneration in Vitro. Exp. Eye Res. 2020, 193, 107974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiao, Y.J.; Chen, J.C.; Wang, C.N.; Wang, C.T. The Mode of Action of Primary Bile Salts on Human Platelets. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1993, 1146, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, G.; Moore, H.B.; Moore, E.E.; Gonzalez, E.; Diamond, S.; Zhu, S.; D’Alessandro, A.; Banerjee, A. Shock Releases Bile Acid Inducing Platelet Inhibition and Fibrinolysis. J. Surg. Res. 2015, 195, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuerholz, T.; Keil, O.; Wagner, T.; Klinzing, S.; Sümpelmann, R.; Oberle, V.; Marx, G. Hydrocortisone Does Not Affect Major Platelet Receptors in Inflammation in Vitro. Steroids 2007, 72, 609–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuerholz, T.; Keil, O.; Vonnemann, M.; Friedrich, L.; Marx, G.; Scheinichen, D. Influence of Hydrocortisone on Platelet Receptor Expression and Aggregation in Vitro. Crit. Care 2005, 9, P393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger Release 2024-3: QikProp, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2025.

- Schrödinger, LLC The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.6.2 2015.

- Gasteiger, J.; Marsili, M. A New Model for Calculating Atomic Charges in Molecules. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978, 19, 3181–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanner, M.F. Python: A Programming Language for Software Integration and Development. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 1999, 17, 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Chen, J.; Cheng, T.; Gindulyte, A.; He, J.; He, S.; Li, Q.; Shoemaker, B.A.; Thiessen, P.A.; Yu, B.; et al. PubChem 2025 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D1516–D1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Abellán, A.; Angosto-Bazarra, D.; Martínez-Banaclocha, H.; de Torre-Minguela, C.; Cerón-Carrasco, J.P.; Pérez-Sánchez, H.; Arostegui, J.I.; Pelegrin, P. MCC950 Closes the Active Conformation of NLRP3 to an Inactive State. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019, 15, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the Speed and Accuracy of Docking with a New Scoring Function, Efficient Optimization, and Multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MetaScreener (https://github.com/bio-hpc/metascreener).

- Adasme, M.F.; Linnemann, K.L.; Bolz, S.N.; Kaiser, F.; Salentin, S.; Haupt, V.J.; Schroeder, M. PLIP 2021: Expanding the Scope of the Protein–Ligand Interaction Profiler to DNA and RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W530–W534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolber, G.; Langer, T. LigandScout: 3-D Pharmacophores Derived from Protein-Bound Ligands and Their Use as Virtual Screening Filters. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2005, 45, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, A.; Giraldo-Ruiz, L.; Ramos, M.C.; Luque, I.; Ribeiro, D.; Postigo-Corrales, F.; Alburquerque-González, B.; Montoro-García, S.; Arroyo-Rodríguez, A.B.; Conesa-Zamora, P.; et al. Discovery of Z1362873773: A Novel Fascin Inhibitor from a Large Chemical Library for Colorectal Cancer 2024, 2024.08.13.606007.

- Nelen, J.; Carmena-Bargueño, M.; Martínez-Cortés, C.; Rodríguez-Martínez, A.; Villalgordo-Soto, J.M.; Pérez-Sánchez, H. ESSENCE-Dock: A Consensus-Based Approach to Enhance Virtual Screening Enrichment in Drug Discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 1605–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sánchez, S.M.; Minguela, A.; Prieto-Merino, D.; Zafrilla-Rentero, M.P.; Abellán-Alemán, J.; Montoro-García, S. The Effect of Regular Intake of Dry-Cured Ham Rich in Bioactive Peptides on Inflammation, Platelet and Monocyte Activation Markers in Humans. Nutrients 2017, 9, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polasky, C.; Wallesch, M.; Loyal, K.; Pries, R.; Wollenberg, B. Measurement of Leukocyte-Platelet Aggregates (LPA) by FACS: A Comparative Analysis. Platelets 2021, 32, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).