1. Introduction

Philadelphia remains at the leading edge of the opioid crisis, with high rates of fentanyl use and associated morbidity. In recent years, the local illicit opioid supply has been increasingly adulterated with potent sedatives, intensifying the clinical challenges associated with withdrawal management. [

1] Xylazine—a veterinary alpha-2 adrenergic agonist—emerged in 2022 as a frequent fentanyl adulterant, becoming present in up to 99% of the publicly checked dope samples by 2023.[

2] The combination of potent synthetic opioids and alpha-2 agonists wrought a series of challenges, including increasing reports of precipitated withdrawal, a serious and previously rare side effect when starting the medication buprenorphine. [

3] This promoted the creation of emergency department (ED) protocols specifically tailored to manage the resulting complex withdrawal syndrome. [

4]

A multimodal opioid withdrawal treatment protocol was implemented at two Philadelphia EDs to address xylazine-associated withdrawal. This approach used multiple pharmacologic classes targeting distinct symptom domains: short-acting opioids (e.g., oxycodone, hydromorphone) for opioid cravings and bridging to partial agonists (low dose buprenorphine), ketamine for NMDA antagonism and analgesia, droperidol or olanzapine for anxiolytic and antiemetic effects, and alpha-2 agonists (tizanidine or guanfacine) for replacement the xylazine. In an early evaluation, the protocol produced a median COWS score reduction from 12 to 4, with only 3.9% of patients leaving AMA compared to a 10.7% historical baseline [

4].

In mid-2024, toxicology surveillance and clinical observations indicated a shift in adulterants, with medetomidine supplanting xylazine as the dominant alpha-2 agonist in the local fentanyl supply [

5]. Medetomidine, an alpha-2 agonist sedative up to 20 times more potent than xylazine [

6,

7], entered the fray, possibly as a result of the scheduling of xylazine as a controlled substance by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. [

8] Clinicians noted increasingly severe and atypical withdrawal symptoms, including profound vomiting, hypertensive crises, tremor without clonus or seizure, hypoactive encephalopathy, and refractory symptoms to conventional treatment. These presentations often required ICU care and were poorly responsive to the previously successful xylazine-era protocol. Clinicians hypothesized that medetomidine-related withdrawal could mimic dexmedetomidine discontinuation syndrome, a well-documented phenomenon of sympathetic overactivity.[

9]

This study evaluated whether the novel opioid withdrawal protocol maintained effectiveness during and after the transition from the xylazine era (XE) to the medetomidine era (ME) in Philadelphia. We compared outcomes from the xylazine and medetomidine eras, hypothesizing a significant decline in treatment efficacy and increased rates of severe clinical outcomes following the emergence of medetomidine.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

We conducted a retrospective cohort study at two urban EDs in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, one academic and one community. The academic hospital, which sees approximately 76,000 visits annually, is a level 1 trauma center. The community hospital, which sees approximately 34,000 visits annually, is a stand-alone center 2.5 miles from the main hospital. Both sites serve large urban populations and care for a high volume of patients with opioid use disorder (OUD). Both hospitals were clinical sites for the retrospective analysis establishing evidence of order set efficacy, with the orders built into the electronic health record (EPIC Systems, Madison, WI). [

4]

The study protocol adhered to STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines for observational research, utilizing the guidelines prior to the development of the project. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained (IRB #1269), with a waiver of informed consent due to the retrospective nature and negligible risk of the study.

Two temporal cohorts were defined using August 1, 2024, as a transition point based on public health data identifying a shift from xylazine to medetomidine as the dominant fentanyl adulterant [

5]. The xylazine-era cohort included encounters from September 1, 2022, when the order set debuted, to July 31, 2024. The medetomidine-era cohort included encounters from August 1, 2024, to March 31, 2025.

On February 11, 2025, in response to local trends, the order sets were updated to address medetomidine adulteration. Doses of short acting opioids were doubled (oxycodone 10 mg > 20 mg, hydromorphone 2mg > 4 mg) and clonidine was added due to the rates of hypertensive crises (0.3 mg orally and 0.3 mg transdermal). Education about this change was made to staff during the standing faculty meeting and resident didactics as well as through virtual/asynchronous communication. While this period still represents part of the ME, given this defined change, it was analyzed both wholly and as a subgroup.

2.2. Population

This study included adult patients (≥18 years) treated in the ED, who received medications from the withdrawal protocol during the study period (September 1, 2022 – March 31, 2025). This represents the total cohort and includes all patients who were present on the database report.

The final cohort, are those from the total who had both pre- and post-treatment COWS scores and a disposition documented in their charts. Exclusion criteria included missing outcome data, pregnancy, and active enrollment in methadone or buprenorphine maintenance therapy.

Detection of xylazine and medetomidine exposure in humans is difficult and not performed routinely. Due to the conjoined nature of opioids and alpha-2 agonists in Philadelphia, fentanyl urine toxicology testing is used as a marker of street “dope” exposure. Adulterant classification was therefore based on temporal trends rather than individual toxicology testing, which was unavailable in the ED setting, aside from fentanyl testing.

2.3. Exposure Classification

Era classification was based on date of presentation and the predominant local adulterant as identified through citywide drug surveillance. Xylazine predominated before August 1, 2024, while medetomidine became the dominant adulterant thereafter. A subgroup analysis of patients treated after a protocol revision on February 11, 2025, was also performed.

2.4. Outcomes

The primary outcome was change in Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Scale (COWS) score from pre- to post-treatment. COWS is a multi-item scale used as the standardized means of assessing withdrawal severity in the United States. [

10] Notably, there are not standardized withdrawal severity tools for alpha-2 agonist withdrawal. [

11] In their absence, given that anxiety, and vital sign abnormalities are included in COWS, this was used as the sole criterion for fentanyl, xylazine and medetomidine withdrawal. Secondary outcomes included: (1) percentage of patients with COWS ≤ 4 post-treatment (which signifies no longer classifying as having withdrawal); (2) disposition from the ED, including AMA discharge, hospital admission, and ICU transfer; and (3) occurrence of serious adverse events during ED care.

The primary outcome was change in COWS score from pre-treatment to post-treatment. Secondary outcomes included the percentage of patients with post-treatment COWS scores ≤4 (defined as symptom resolution), ED disposition (including discharge, AMA, and ICU admission).

2.5. Measurements and Analysis

Data for this study was obtained by an automated database report. This report contains visit demographics, chief complaint and diagnostic data (urine fentanyl screen results), pre- and post-treatment COWS scores and disposition data.

Statistical analysis was performed using R statistical software (R Core Team, 2023). Descriptive statistics were calculated utilizing demographic information documented in the codebook including standard deviations for non-parametric data.

Continuous variables were summarized as medians with interquartile ranges and compared using Mann–Whitney U and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and compared using chi-square tests. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Monthly COWS trends and responder rates were graphed with key inflection points noted.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

A total of 1269 patient encounters met inclusion criteria, out of 1980 total encounters having received medications from the protocol during the period. Of the final cohort, 616 encounters were in the xylazine-era cohort (September 2022 – July 2024) and 653 in the medetomidine-era cohort (August 2024 – March 2025). The two cohorts were similar in demographic makeup both in their total and final cohort forms. The mean age was 39.8 years in the XE and 40.8 years in the medetomidine era, which was statistically but not practically different. Over 35% of patients in the xylazine cohort and 36.0% in the medetomidine cohort were female. Full demographics data, including race/ethnicity is included in

Table 1. Aside from age, no other demographic categories were different between cohorts.

Notably, xylazine is well known to be associated with severe skin ulceration and eventual infection. [

11] The chief complaints of all presentations are shown in

Table 2. They have been simplified for categorization sake, please see

Appendix A for a full list of chief complaints and which categories they were placed. It is therefore quite telling that rates of visit for skin and soft tissue visit fell from 32.1% to 15.2% (p < 0.001) between the eras and that volume was made up for with a commensurate rise in visits purely for opioid withdrawal (10.5% to 25.6%, p < 0.001).

At presentation, median initial COWS scores were higher in the medetomidine cohort (16.0, IQR 12–20) than in the xylazine cohort (13.0, IQR 10–17), which was statistically significant (p < 0.001). Of note, there were also significantly more presentations per month in the medetomidine era than in the XE. See full COWS score and encounter details in

Table 3.

3.2. Withdrawal Treatment and COWS Outcomes

The primary outcome of withdrawal severity improvement, measured by the change in COWS, differed markedly between the two eras.

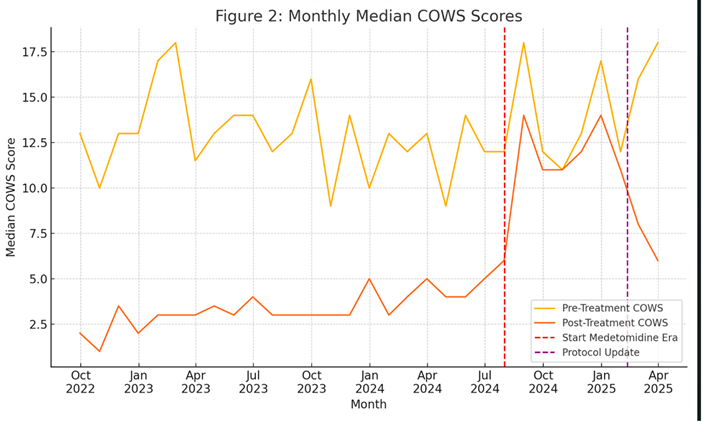

Figure 1 illustrates the COWS scores before and after treatment for each cohort (median and IQR). In the XE cohort, withdrawal scores improved substantially with protocol treatment. The median COWS decreased from 13.0 (IQR 10–17) on arrival to 4.0 (IQR 1–6) after treatment, a median reduction of –9 points (p < 0.001 for within-cohort pre/post comparison). This confirms the efficacy of the protocol in mitigating withdrawal signs and symptoms in the XE, consistent with previously published outcomes [

2].

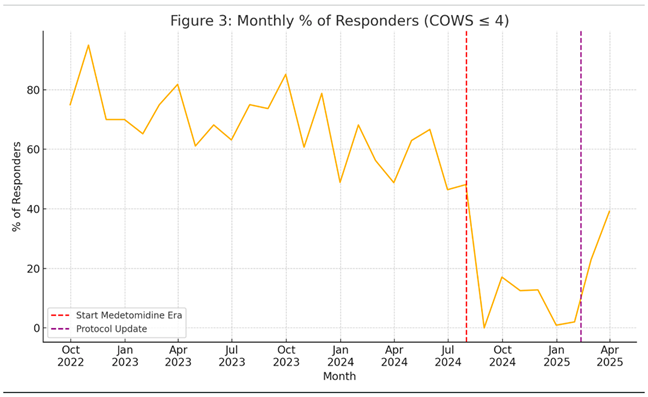

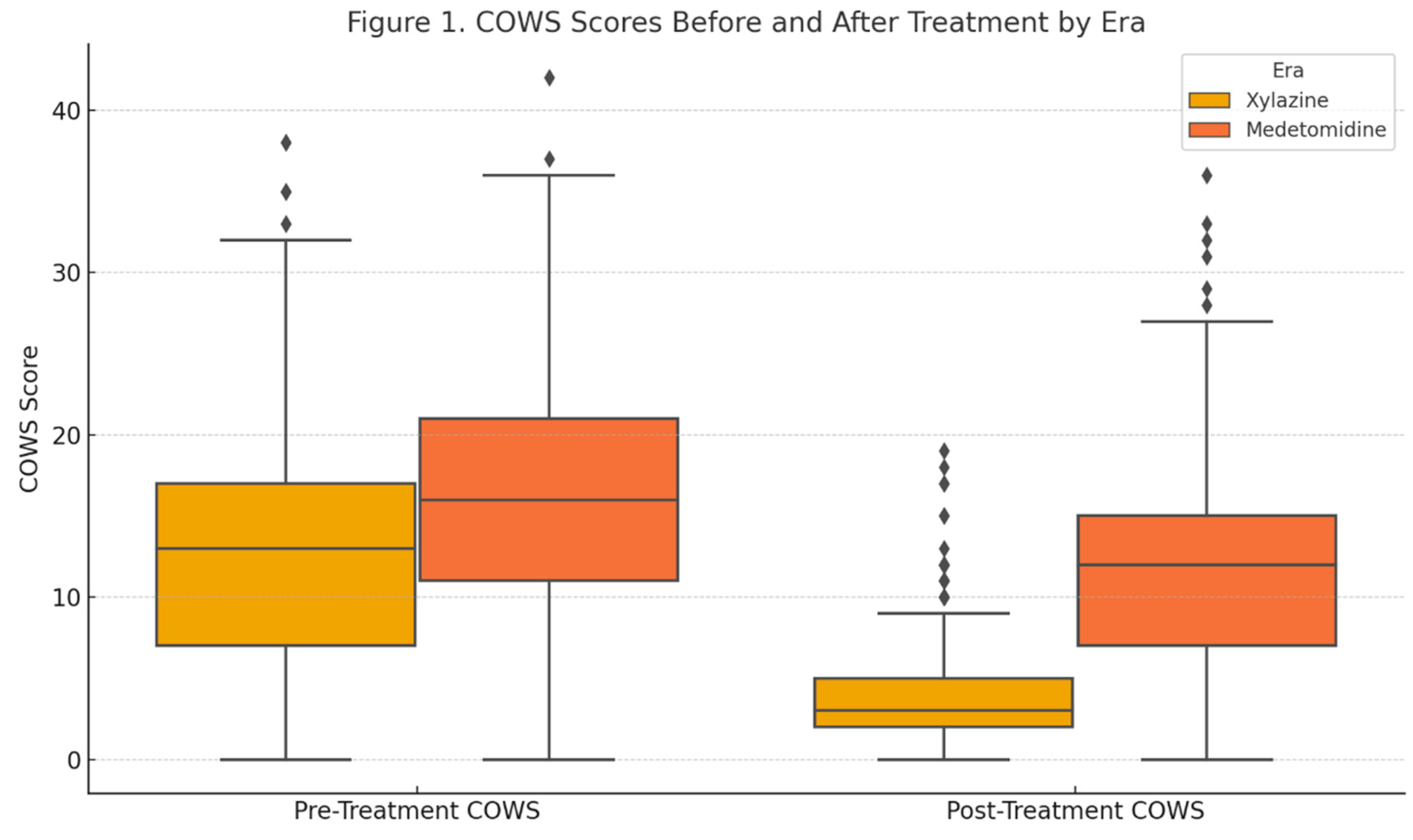

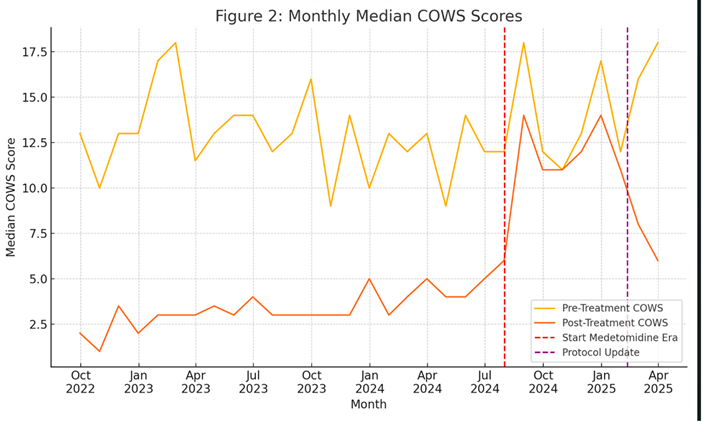

A large majority of XE patients achieved a post-treatment COWS score of < 5 (65.6%, indicating relief from withdrawal). In contrast, the ME cohort experienced more modest improvements. The median COWS in this group was 16.0 (IQR 12–20) before treatment and 12.0 (IQR 8–16) post-treatment, for a median reduction of only –4 points. While this reduction was still statistically significant compared to pre-treatment scores (p = 0.013), the magnitude of improvement was clearly smaller. Only 14.2% during the ME attained a post-treatment COWS < 5 (p < 0.001 vs XE). The between-cohort comparison of ∆COWS was highly significant (p < 0.001), indicating that the protocol’s effectiveness in reducing objective withdrawal scores was significantly blunted in the ME. See Figure 2 for monthly median COWS scores (pre- and post-treatment).

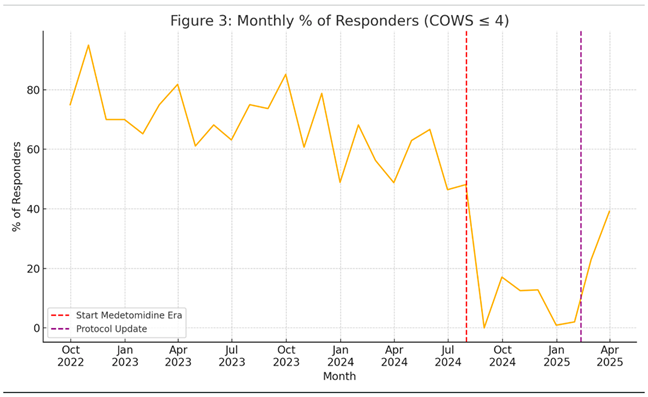

Figure 3 shows the % of patients who achieved a COWS score of 5 or lower (defined as no longer demonstrating symptoms of withdrawal), showing the dramatic change from XE to ME, starting in the months preceding the change in adulteration.

To account for any baseline differences, we performed a two-way analysis of variance on COWS scores with time (pre vs post) and era as factors. This analysis demonstrated a significant interaction effect (p < 0.001), corroborating that the improvement in COWS over time depended on which era (XE vs ME). In essence, patients in the ME did not respond as robustly to the standardized regimen as those in the XE did.

3.3. Secondary Outcomes: Subgroup, Disposition and Adverse Events

To assess the impact of the revised withdrawal protocol introduced on February 11, 2025, we performed a subgroup analysis of ME encounters before and after the protocol change. Among the 653 encounters in the ME, 174 (26.6%) occurred after the updated protocol was implemented. Patients in this subgroup showed modestly greater improvement in COWS scores compared to those treated earlier in the medetomidine era: median reduction in COWS was −6.0 (IQR: −9 to −3) post-revision vs −4.0 (IQR: −6 to −2) pre-revision (p < 0.001). Additionally, the proportion of patients achieving post-treatment COWS ≤4 increased from 11.0% to 21.1% after the protocol update (p = 0.003). While still substantially lower than XE outcomes, these findings suggest partial restoration of protocol efficacy following the revision.

We also examined clinical outcomes beyond COWS scores, studying dispositions. See

Table 4. Disposition from the ED differed between the two eras in several notable ways. The incidence of patients leaving against medical advice (AMA) was higher in the medetomidine cohort (6.5%) than in the xylazine cohort (3.6%), though the difference was only mildly statistically significant (p = 0.038). More notably, ICU-level admission occurred more frequently in the medetomidine cohort: 88 (18.4% of admissions) ME patients were admitted to the ICU from the ED, compared to 35 patients in the xylazine cohort (8.5% of admissions, p < 0.001). Adverse events were infrequent, and no serious adverse events were documented in either group.

In the subgroup analysis that separated the ME into before and after withdrawal protocols were changed, ICU and overall admission rates remained high (16.8%, 75.3%), although ICU rates were slightly but not significantly reduced compared to the pre protocol change ME period (18.4%, p = 0.107). AMA rates slightly improved after protocol change, did not significantly change either. See Figures 2 and 3 for monthly trends.

Hospital admissions for continued withdrawal management were more frequent in the ME. In the xylazine-era, nearly 30% of patients could be discharged home or to a treatment program after ED management. In contrast, in the medetomidine-era cohort, only around 20% were discharged from the ED, while a significantly higher proportion (~75%) required inpatient admission for ongoing care of withdrawal, including almost double the amount who needed ICU care.

Regarding adverse events, the protocol was generally well-tolerated in both groups, with no serious adverse events directly attributable to the medications. There were zero instances of respiratory arrest or cardiac arrest due to the treatment in either era.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that the emergence of medetomidine as an adulterant in illicit fentanyl coincided with a marked decline in the effectiveness of a novel opioid withdrawal management protocol developed during the XE. In the era when fentanyl was co-adulterated with xylazine (September 2022–July 2024), the protocol reliably reduced withdrawal severity, whereas during the ME (August 2024–March 2025) we observed significantly smaller improvements in COWS scores. Concurrently, ME patients saw higher rates of intensive care unit (ICU) admission for withdrawal-related complications and more patients leaving the emergency department against medical advice (AMA).

These disparities suggest that medetomidine adulteration introduced additional clinical challenges not adequately addressed by a protocol originally tailored to manage opioid withdrawal with another potent alpha-2 agonist (xylazine) as the primary adulterant. Xylazine, a veterinary alpha-2 agonist sedative, rose to prominence as a fentanyl adulterant in the mid-2010s and early 2020s. By 2019–2022, xylazine was detected in approximately 2.9–10.9% of fentanyl-involved overdose deaths in the United States[

12]. Clinicians recognized that xylazine’s presence complicates opioid overdoses because its central sedative effects (hypoventilation, bradycardia) are not reversed by naloxone[

12]. Medetomidine — a pharmacologically similar, though more potent alpha-2 agonist — has rapidly followed as a new adulterant over the past two years[

13]. The first confirmed cases of medetomidine exposure in U.S. overdose patients were reported in late 2023 in a CDC surveillance brief[

13], which called for heightened toxicologic screening and clinical awareness of this emerging adulterant[

13]. Shortly thereafter, public health alerts in early 2024 announced the detection of medetomidine in local fentanyl supplies in Philadelphia and New York[

14,

15]. These alerts noted that medetomidine was identified in street “dope” samples alongside fentanyl and xylazine [

14], and described overdose clusters involving profound sedation unresponsive to naloxone[

14,

15].

Forensic drug surveillance from mid-2024 further documented medetomidine’s proliferation, being identified in opioid samples across multiple states[

16]. Medetomidine was almost invariably found in combination with xylazine[

16], indicating a shift to an increasingly dynamic supply pattern in which fentanyl is co-mixed with multiple sedatives. This context likely contributed to the challenging clinical presentations observed during the ME. Patients were effectively exposed to two synergistic α_2-agonists (medetomidine plus xylazine) alongside fentanyl, a combination expected to produce more profound and prolonged CNS depression than either sedative alone[

16]. It is plausible that illicit suppliers introduced medetomidine as a more potent or longer-acting replacement for xylazine once awareness and regulation of xylazine increased, thereby sustaining the enhanced sedative “kick” of adulterated fentanyl.

Medetomidine’s pharmacologic properties help explain why its presence undermined our withdrawal protocol’s effectiveness. Medetomidine is a veterinary alpha-2 agonist sedative that is substantially more potent than xylazine, though most animal studies cite estimates of 10-20x greater potency [

6,

7], one clinical report estimates it to be on the order of 200 times more potent [

17]. Pharmacodynamically, medetomidine produces similar effects to xylazine – including sedation, analgesia, bradycardia, and hypotension[

18] – but tends to have a longer duration of action[

17,

19]. Critically, medetomidine’s CNS depressant effects are not reversed by the opioid antagonist naloxone[

13,

17]. Thus, an opioid user co-exposed to medetomidine may remain heavily sedated even after naloxone administration. A CDC case series documented exactly this scenario: patients with fentanyl–medetomidine exposure presented with prolonged unresponsiveness and hypotension that was unresponsive to naloxone[

13]. Frontline clinicians have similarly been cautioned to suspect medetomidine or other α_2-agonists when an apparent opioid overdose victim fails to awaken after naloxone[

17]. In our cohort, these pharmacologic effects likely contributed to the increased number of ED visits for withdrawal, as well as the increased need for ICU-level care during the ME, as patients often suffered more severe withdrawal, requiring higher intensity care.

In contrast to xylazine, which is notorious for causing necrotic skin ulcers in chronic users[

20], medetomidine has not been linked to such tissue injury. Its chief hazards are systemic, exerting powerful sedating effects that complicate both overdose resuscitation and withdrawal management. This is notable given the decreased number of visits related to skin and soft tissue infections in the ME.

Another key consideration is the potential for medetomidine to cause physiological dependence and a withdrawal syndrome, compounding the challenge of opioid withdrawal. Chronic exposure to alpha-2 agonists can induce adaptive changes; abrupt cessation precipitates a rebound hyperadrenergic state. In the critical care literature, prolonged infusions of dexmedetomidine (the active enantiomer of medetomidine) have been shown to produce significant withdrawal symptoms upon discontinuation[

21]. A recent meta-analysis reported that over one-third of patients developed hypertension and tachycardia after stopping long-term dexmedetomidine, and it advocated gradual weaning or adjunctive clonidine to mitigate such withdrawal effects[

21]. By analogy, individuals using medetomidine-adulterated opioids regularly may develop dependence on this sedative. When they present to the ED in opioid withdrawal (having not used for several hours), they plausibly could simultaneously be in medetomidine withdrawal.

This scenario would likely manifest as severe autonomic hyperactivity (anxiety, vomiting, tremors, hypertension, tachycardia) that overlaps with opioid withdrawal but does not fully respond to opioid agonist therapy, which is exactly what we found evidence to support. Indeed, health officials have noted that frequent xylazine users experience a distinct withdrawal syndrome (irritability, anxiety, palpitations, and elevated blood pressure) when xylazine is discontinued[

20]. It is likely that medetomidine causes a similar withdrawal phenomenon. Unrecognized alpha-2 agonist withdrawal in our medetomidine-era patients is likely therefore a key factor in the blunted COWS score improvements – since certain withdrawal signs (e.g., tachycardia, diaphoresis, agitation) could persist due to persistent autonomic activation.

After appreciating these issues, we modified our ED withdrawal protocol in February 2025 to better address medetomidine co-exposure. Although detailed outcomes of the new protocol are beyond the scope of this discussion, and will be published separately, we observed clear improvements following its implementation: withdrawal-symptom relief rates began to rise, and ICU admission and AMA discharge rates declined relative to earlier in the medetomidine era. The protocol revisions included measures to counteract medetomidine withdrawal, such as more aggressive management of autonomic symptoms by use of clonidine and sympatholysis with higher doses of short acting opioids. Clonidine is a more potent oral alpha-2 agonist than tizanidine or guanfacine, up to 50 times more vasoactive. [

21] In essence, we attempted to pharmacologically bridge the sudden loss of alpha-2 agonist input – an approach analogous to using clonidine to taper patients off dexmedetomidine or xylazine[

22].

The partial restoration of efficacy supports the notion that more aggressive management may improve outcomes. However, even with these adjustments, medetomidine-era outcomes did not return fully to the baseline seen in the xylazine era, indicating that significant challenges remain. Patients with medetomidine exposure may require prolonged observation, higher levels of care to completely normalize their withdrawal trajectory. Further work is needed to determine optimal strategies for managing withdrawal in the context of medetomidine and similar sedative adulterants. Overall, our findings highlight the necessity for clinicians to rapidly adapt withdrawal management protocols in response to changes in the adulterant profile of illicit opioids as well as the importance of community-based drug testing programs. A protocol that was effective for “tranq dope” (fentanyl + xylazine) had to be recalibrated for what some have termed “demon dope” (fentanyl + xylazine + medetomidine). Frontline providers should maintain a high index of suspicion for atypical sedative co-intoxication in opioid users – especially if a patient exhibits deeper-than-expected sedation, bradycardia, hypotension or withdrawal symptoms that are unusually refractory to standard treatment (with associated hypertension, tachycardia and sympathetic activation). In such cases, early use of adjunct therapies (targeted at the sedative component) and a low threshold for intensive monitoring may be warranted. These conclusions align with emerging guidance urging emergency and critical care providers to recognize and manage polysubstance opioid withdrawal, including the effects of alpha-2 agonist adulterants[

17]. By integrating clinical findings with public health intelligence on drug-supply trends, healthcare systems can better prepare for and respond to the next evolution of the opioid crisis.

5. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, as a retrospective analysis, it is inherently subject to confounding, selection bias, and limited generalizability beyond the two emergency departments studied. While both institutions serve a high volume of individuals with opioid use disorder in Philadelphia, the findings may not reflect experiences in other regions or healthcare systems.

Second, not all patients receiving withdrawal protocol treatment during the study period could be analyzed due to missing data. Specifically, patients lacking either pre- or post-treatment COWS scores or documented ED disposition were excluded from the final cohort. This may have introduced bias if these excluded encounters differed systematically from those included.

Third, individual toxicologic confirmation of xylazine or medetomidine exposure was not available. Neither compound is included in routine clinical toxicology screening, and their detection requires specialized analytical techniques that were not performed in real-time ED care. Era classification was therefore inferred based on temporal association with drug-supply trends reported by public health surveillance, which may misclassify some cases—especially during transition months.

Fourth, chief complaint data relied on structured text documentation, which introduces limitations in symptom categorization. Complaints related to opioid withdrawal may have been inconsistently documented or underreported if patients presented with overlapping symptoms such as vomiting or altered mental status. As a result, the frequency of opioid withdrawal presentations may be underrepresented in our analysis.

Additionally, the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) was the sole tool used to assess withdrawal severity, though it was developed for opioid withdrawal and may not fully capture the autonomic or neuropsychiatric features of alpha-2 agonist withdrawal. There are currently no validated tools for medetomidine or xylazine withdrawal, and this likely underestimates the true symptom burden in such patients.

Finally, while the protocol revision in February 2025 showed promising improvements, this subgroup had limited follow-up time, and further data are needed to confirm its long-term effectiveness and safety in the context of medetomidine exposure.

6. Conclusions

In summary, this retrospective cohort analysis found that our opioid withdrawal protocol was significantly less effective during the period when fentanyl was adulterated with medetomidine, compared to the earlier xylazine-dominant era. Patients in the medetomidine era experienced poorer withdrawal symptom relief and higher rates of ICU admission and AMA disposition, indicating more severe and complex withdrawal presentations. Implementation of a revised protocol (in February 2025), which incorporated adjustments to address medetomidine’s alpha-2 agonist effects, was associated with partial restoration of efficacy. This suggests that adapting treatment strategies to account for medetomidine co-exposure can mitigate some of the negative impact.

However, even after protocol changes, medetomidine-exposed patients remained more difficult to treat than those in the xylazine era, underscoring the formidable challenge posed by this new adulterant. For medical practice, these findings highlight the importance of dynamic protocol revisions in the face of an evolving drug supply. Standard opioid-centric withdrawal management approaches may fail when confronted with novel adulterants that produce additional non-opioid pharmacologic effects (such as profound sedation or autonomic instability). Clinicians should be alert to regional drug trends and be prepared to modify withdrawal treatment plans accordingly.

Looking ahead, enhanced surveillance of illicit drugs is crucial for early identification of emerging adulterants. Timely toxicological analysis of overdose cases and drug samples, coupled with rapid information-sharing through public health alerts, will enable clinicians to anticipate changes in withdrawal patient presentations[

13]. Future research should focus on developing tailored withdrawal protocols for multi-substance exposures. This includes investigating optimal management of alpha-2 agonist withdrawal in patients with OUD– such as the role of clonidine or other sympatholytics in treating medetomidine/xylazine withdrawal – and determining best practices to reduce ICU utilization and prevent AMA dispositions in these complex cases. In conclusion, a proactive, evidence-based approach to new opioid adulterants is needed to maintain effective withdrawal care. Ongoing collaboration between clinicians, addiction medicine and toxicology experts, as well as public health authorities, will be essential to stay ahead of emerging trends and to safeguard the outcomes of patients with opioid use disorder.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, K.L. and P.D..; methodology, K.L. ; software, K.L. ; validation, K.L. , Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, K.L. ; investigation, K.L. ; resources, K.L. ; data curation, K.L. ; writing—original draft preparation, K.L. ; writing—review and editing, K.L. ; visualization, K.L. ; supervision, K.L. ; project administration, K.L. ; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In this section, you should add the Institutional Review Board Statement and approval number, if relevant to your study. You might choose to exclude this statement if the study did not require ethical approval. Please note that the Editorial Office might ask you for further information. Please add “The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving humans. OR “The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving animals. OR “Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Data Availability Statement

Please reach out to authors if interest in data set exists.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used [ChatGPT, version 4o] for the purposes of assisting with formatting and literature review. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ED |

Emergency Department |

| ME |

Medetomidine Era |

| XE |

Xylazine Era |

| OUD |

Opioid Use Disorder |

| COWS |

Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Scale |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

Appendix A

Appendix A. Categorization of Chief Complaints by Assigned Presentation Category

| Chief Complaint |

Assigned Category |

| ABDOMINAL INJURY |

Trauma |

| ABDOMINAL PAIN |

General Medical/Other |

| ABNORMAL LAB |

General Medical/Other |

| ABRASION |

Trauma |

| ABSCESS |

Skin/Soft Tissue Infection |

| ABSCESS DRAINAGE |

Skin/Soft Tissue Infection |

| ALCOHOL INTOXICATION |

Psychiatric, Behavioral and Social Needs |

| ALTERED MENTAL STATUS |

General Medical/Other |

| ANGIOEDEMA |

General Medical/Other |

| ANKLE PAIN |

General Medical/Other |

| ANXIETY |

Psychiatric, Behavioral and Social Needs |

| ARM INJURY |

Trauma |

| ARM PAIN |

General Medical/Other |

| ARM SWELLING |

Skin/Soft Tissue Infection |

| ASSAULT |

Trauma |

| ASTHMA |

General Medical/Other |

| BACK PAIN |

General Medical/Other |

| BLACK OR BLOODY STOOL |

General Medical/Other |

| BLOOD INFECTION |

General Medical/Other |

| BURN |

Trauma |

| CAST CHECK |

General Medical/Other |

| CELLULITIS |

Skin/Soft Tissue Infection |

| CHEST PAIN |

General Medical/Other |

| CHEST TIGHTNESS |

General Medical/Other |

| CHILLS |

General Medical/Other |

| COLD EXPOSURE |

Psychiatric, Behavioral and Social Needs |

| CONSTIPATION |

General Medical/Other |

| COUGH |

General Medical/Other |

| COUGHING UP BLOOD |

General Medical/Other |

| CYST |

General Medical/Other |

| DEBRIDEMENT |

General Medical/Other |

| DENTAL PAIN |

General Medical/Other |

| DEPRESSION |

Psychiatric, Behavioral and Social Needs |

| DETOX |

Opioid Withdrawal |

| DIALYSIS TREATMENT |

General Medical/Other |

| DIARRHEA |

General Medical/Other |

| DIFFICULTY WALKING |

General Medical/Other |

| DIZZINESS |

General Medical/Other |

| DRUG OVERDOSE |

Psychiatric, Behavioral and Social Needs |

| DRUG PROBLEM |

Psychiatric, Behavioral and Social Needs |

| DYSURIA |

General Medical/Other |

| EARACHE |

General Medical/Other |

| ELBOW PAIN |

General Medical/Other |

| ENDOCARDITIS |

General Medical/Other |

| EXTREMITY WEAKNESS |

General Medical/Other |

| EYE DRAINAGE |

General Medical/Other |

| EYE INFECTION |

General Medical/Other |

| EYE PAIN |

General Medical/Other |

| EYE PROBLEM |

General Medical/Other |

| EYE TRAUMA |

Trauma |

| FACIAL SWELLING |

General Medical/Other |

| FAILURE TO THRIVE |

Psychiatric, Behavioral and Social Needs |

| FALL |

Trauma |

| FEVER |

General Medical/Other |

| FINGER INJURY |

Trauma |

| FINGER PAIN |

General Medical/Other |

| FLANK PAIN |

General Medical/Other |

| FLU SYMPTOMS |

General Medical/Other |

| FOOT BLISTER |

General Medical/Other |

| FOOT INJURY |

Trauma |

| FOOT PAIN |

General Medical/Other |

| FOOT SWELLING |

General Medical/Other |

| FOOT WOUND CHECK |

General Medical/Other |

| FOREIGN BODY |

General Medical/Other |

| FOREIGN BODY IN SKIN |

General Medical/Other |

| FROSTBITE |

Trauma |

| GENERALIZED BODY ACHES |

General Medical/Other |

| GENITAL WARTS |

General Medical/Other |

| GROIN PAIN |

General Medical/Other |

| GROIN SWELLING |

General Medical/Other |

| GUN SHOT WOUND |

Trauma |

| HAND INFECTION |

Skin/Soft Tissue Infection |

| HAND INJURY |

Trauma |

| HAND PAIN |

General Medical/Other |

| HEAD LICE |

General Medical/Other |

| HEADACHE |

General Medical/Other |

| HERNIA |

General Medical/Other |

| HIP PAIN |

General Medical/Other |

| HOMELESS |

Psychiatric, Behavioral and Social Needs |

| HYPERGLYCEMIA |

General Medical/Other |

| HYPERTENSION |

General Medical/Other |

| HYPOGLYCEMIA |

General Medical/Other |

| INFECTION |

Skin/Soft Tissue Infection |

| INGESTION |

Psychiatric, Behavioral and Social Needs |

| INTOXICATED |

Psychiatric, Behavioral and Social Needs |

| JAW PAIN |

General Medical/Other |

| JOINT SWELLING |

General Medical/Other |

| KNEE INJURY |

Trauma |

| KNEE PAIN |

General Medical/Other |

| LEG INJURY |

Trauma |

| LEG PAIN |

General Medical/Other |

| LEG PROBLEM |

General Medical/Other |

| LEG SWELLING |

General Medical/Other |

| MEDICAL COMPLAINT |

General Medical/Other |

| MEDICATION REFILL |

Psychiatric, Behavioral and Social Needs |

| MOTOR VEHICLE VS PEDESTRIAN |

Trauma |

| MOTOR VEHICLE CRASH |

Trauma |

| MRSA |

Skin/Soft Tissue Infection |

| MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS |

General Medical/Other |

| NASAL CONGESTION |

General Medical/Other |

| NAUSEA |

General Medical/Other |

| NECK INJURY |

Trauma |

| NECK PAIN |

General Medical/Other |

| NUMBNESS |

General Medical/Other |

| OPEN WOUND |

Skin/Soft Tissue Infection |

| OSTEOMYELITIS |

General Medical/Other |

| OTHER |

General Medical/Other |

| PAIN |

General Medical/Other |

| PAIN WITH BREATHING |

General Medical/Other |

| PALPITATIONS |

General Medical/Other |

| PNEUMONIA |

General Medical/Other |

| POOR APPETITE |

General Medical/Other |

| POST-OP PROBLEM |

General Medical/Other |

| PREGNANCY PROBLEM |

General Medical/Other |

| PSYCHIATRIC EVALUATION |

Psychiatric, Behavioral and Social Needs |

| RAPID HEART RATE |

General Medical/Other |

| RASH |

General Medical/Other |

| RECURRENT SKIN INFECTIONS |

Skin/Soft Tissue Infection |

| RESPIRATORY DISTRESS |

General Medical/Other |

| RIB INJURY |

General Medical/Other |

| RING REMOVAL |

General Medical/Other |

| RULE OUT STROKE |

General Medical/Other |

| SEIZURES |

General Medical/Other |

| SEPSIS OUTREACH |

General Medical/Other |

| SEXUAL ASSAULT |

Trauma |

| SHORTNESS OF BREATH |

General Medical/Other |

| SHOULDER PAIN |

General Medical/Other |

| SINUSITIS |

General Medical/Other |

| SKIN PROBLEM |

Skin/Soft Tissue Infection |

| SOCIAL DETERMINANTS SCREENING |

Psychiatric, Behavioral and Social Needs |

| SORE THROAT |

General Medical/Other |

| SPASMS |

General Medical/Other |

| STAB WOUND |

Trauma |

| STROKE ALERT |

General Medical/Other |

| SUICIDAL |

Psychiatric, Behavioral and Social Needs |

| SUICIDE ATTEMPT |

Psychiatric, Behavioral and Social Needs |

| SWELLING |

General Medical/Other |

| SWELLING HEAD/NECK |

General Medical/Other |

| SYNCOPE |

General Medical/Other |

| TRAUMA |

Trauma |

| URI |

General Medical/Other |

| URINARY PROBLEM |

General Medical/Other |

| VAGINAL BLEEDING |

General Medical/Other |

| VAGINAL BLEEDING - PREGNANT |

General Medical/Other |

| VASCULAR ACCESS PROBLEM |

General Medical/Other |

| VENOUS THROMBOSIS |

General Medical/Other |

| VOMITING |

General Medical/Other |

| VOMITING BLOOD |

General Medical/Other |

| WEAKNESS - GENERALIZED |

General Medical/Other |

| WELLNESS VISIT |

Psychiatric, Behavioral and Social Needs |

| WITHDRAWAL |

Opioid Withdrawal |

| WOUND CARE |

Skin/Soft Tissue Infection |

| WOUND CHECK |

Skin/Soft Tissue Infection |

| WOUND DEHISCENCE |

Skin/Soft Tissue Infection |

| WOUND INFECTION |

Skin/Soft Tissue Infection |

| WRIST PAIN |

General Medical/Other |

References

- Quijano T, Crowell J, Eggert K, Clark K, Alexander M, Grau L, Heimer R. Xylazine in the drug supply: Emerging threats and lessons learned in areas with high levels of adulteration. Int. J. Drug Policy 2023, 120, 104154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeBord JS, Shinefeld J, Russell R, Denn M, Quinter A, Logan BK, Teixeira da Silva D, Krotulski AJ. Drug Checking—Quarterly Report: Philadelphia, PA, USA. Center for Forensic Science Research and Education, 2023. Available online: https://www.cfsre.org/images/content/reports/drug_checking/2023_Q1_and_Q2_Drug_Checking_Quarterly_Report_CFSRE_NPS_Discovery.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Varshneya NB, Thakrar AP, Hobelmann JG, Dunn KE, Huhn AS. Evidence of buprenorphine-precipitated withdrawal in persons who use fentanyl. J. Addict. Med. 2022, 16, e265–e268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- London K, Li Y, Kahoud JL, Cho D, Mulholland J, Roque S, Stugart L, Gillingham J, Borne E, Slovis B. Tranq dope: Characterization of an ED cohort treated with a novel opioid withdrawal protocol in the era of fentanyl/xylazine. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 85, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira da Silva D, LaBoy C, Franklin F. Hospitals and behavioral health providers are reporting severe and worsening presentations of withdrawal among people who use drugs (PWUD) in Philadelphia. Philadelphia Department of Public Health, Health Alert 2024. Available online: https://hip.phila.gov/document/4874/PDPH-HAN-00444A-12-10-2024.pdf/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Virtanen R, Savola JM, Saano V, Nyman L. Characterization of the selectivity, specificity and potency of medetomidine as an α2-adrenoceptor agonist. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1988, 150, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaygıngül R, Belge A. The comparison of clinical and cardiopulmonary effects of xylazine, medetomidine and detomidine in dogs. Ankara Univ. Vet. Fak. Derg. 2018, 65, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugarman OK, Shah H, Whaley S, McCourt A, Saloner B, Bandara S. A content analysis of legal policy responses to xylazine in the illicit drug supply in the United States. Int. J. Drug Policy 2024, 129, 104472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukoyi AT, Coker SA, Lewis LD, Nierenberg DW. Two cases of acute dexmedetomidine withdrawal syndrome following prolonged infusion in the intensive care unit: Report of cases and review of the literature. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2013, 32, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesson DR, Ling W. The clinical opiate withdrawal scale (COWS). J. Psychoact. Drugs 2003, 35, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander R, Agwuncha C, Wilson C, Schrecker J, Holt A, Heltsley R. Withdrawal signs and symptoms among patients positive for fentanyl with and without xylazine. J. Addict. Med. 2025, 19, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kariisa, M.; O’Donnell, J.; Kumar, S.; Mattson, C.L.; Goldberger, B.A. Illicitly Manufactured Fentanyl–Involved Overdose Deaths with Detected Xylazine—United States, January 2019–June 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, E.S.; Buchanan, J.; Aldy, K.; Shulman, J.; Krotulski, A.J.; Walton, S.E.; Logan, B.K.; Wax, P.M.; Campleman, S.; Brent, J.A.; et al. Notes from the Field: Detection of Medetomidine Among Patients Evaluated in Emergency Departments for Suspected Opioid Overdoses—Missouri, Colorado, and Pennsylvania, September 2020–December 2023. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 672–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philadelphia Department of Public Health. Health Alert: Medetomidine Detected in Philadelphia’s Illicit Drug Supply. Published 13 May 2024. Available online: https://hip.phila.gov/document/4421/PDPH-HAN-0441A-05-13-24.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2024).

- New York State Office of Addiction Services and Supports. Another Potent Sedative, Medetomidine, Now Appearing in Illicit Drug Supply. Published 31 May 2024. Available online: https://oasas.ny.gov/advisory-may-31-2024 (accessed on 6 October 2024).

- Krotulski, A.J.; Shinefeld, J.; Moraff, C.; Wood, T.; Walton, S.E.; DeBord, J.S.; Denn, M.T.; Quinter, A.D.; Logan, B.K.; Medetomidine Rapidly Proliferating Across USA—Implicated in Recreational Opioid Drug Supply; Causing Overdose Outbreaks. CFSRE NPS Discovery Public Alert, 20 May 2024. Available online: https://www.cfsre.org/nps-discovery/public-alerts/medetomidine-rapidly-proliferating-across-usa-implicated-in-recreational-opioid-drug-supply-causing-overdose-outbreaks (accessed on 6 October 2024).

- Sood, N.; Dhillon, G.; Illicit Medetomidine Use with Fentanyl. The Hospitalist 2025, Published 1 January 2025. Available online: https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/38385/addiction-medicine/illicit-medetomidine-use-with-fentanyl/ (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Scheinin, H.; Virtanen, R.; MacDonald, E.; Lammintausta, R.; Scheinin, M. Medetomidine—A Novel Alpha2-Adrenoceptor Agonist: A Review of Its Pharmacodynamic Effects. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 1989, 13, 635–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papich, M.G. Medetomidine Hydrochloride. In Saunders Handbook of Veterinary Drugs, 4th ed.; Papich, M.G., Ed.; W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 481–483. [Google Scholar]

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. What Is Xylazine? (Frequently Asked Questions). Published May 2023. Available online: https://www.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/basas/xylazine-faq.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Suárez-Lledó, A.; Padullés, A.; Lozano, T.; Cobo-Sacristán, S.; Colls, M.; Jódar, R. Management of Tizanidine Withdrawal Syndrome: A Case Report. Clin. Med. Insights Case Rep. 2018, 11, 1179547618758022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knapp, T.; DiLeonardo, O.; Maul, T.; Hochwald, A.; Li, Z.; Hossain, J.; Lowry, A.; Parker, J.; Baker, K.; Wearden, P.; et al. Dexmedetomidine Withdrawal Syndrome in Children in the PICU: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 25, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).