1. Introduction

In palliative care, opioids are essential for improving patients’ quality of life by managing pain, particularly cancer-related pain. Their analgesic effects stem from agonist activity at the μ-opioid receptor (MOR) in the central nervous system [

1]. However, MORs are also expressed in peripheral organs, wherein their activation can lead to diverse side effects. For example, stimulation of MORs in the respiratory center can cause respiratory depression, while activation in the chemoreceptor trigger zone induces nausea and vomiting [

2,

3]. Additionally, opioids’ central effects can result in drowsiness, delirium, and somnolence [

4,

5]. Although these side effects are consistently associated with MOR agonist activity, their frequency varies markedly among different opioids [

6]. Therefore, when patients experience adverse effects during opioid therapy, switching to another opioid is often necessary to maintain their quality of life. Monitoring and managing these symptoms [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14] are critical aspects of clinical practice. However, owing to the limited comprehensive research on opioid-induced side effects, opioid switching is often guided by insufficient evidence.

In this study, we analyzed the side effects of “strong opioids” commonly used in palliative care in Japan using data from the Side Effect Resource (SIDER) database [

15]. Developed by the European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Germany and accessible online [

16,

17], SIDER compiles detailed drug side-effect data and is widely used in pharmaceutical research and drug safety evaluation. The latest version, SIDER 4.1, released on October 21, 2015, includes data on 1,430 drugs. SIDER is a valuable resource for researchers and healthcare professionals, offering critical insights into side-effect risks and facilitating the prediction of drug–drug interactions. It integrates adverse event data from clinical trials, package inserts, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Notably, SIDER includes adverse event incidence rates derived from clinical trials and package inserts, providing an analytical advantage over spontaneous reporting databases, such as VisiBase, FAERS, and JADER, which lack data on routine drug use cases and cannot calculate incidence rates.

A prior study using SIDER analyzed clinical events related to clozapine treatment, comparing side-effect data from SIDER with electronic health records [

18]. This study assessed the consistency of electronic health record–based text-mining methods and validated SIDER’s utility. Such studies highlight SIDER’s role in assessing real-world data corroborating study findings.

In summary, SIDER offers major benefits for understanding drug side effects, including their frequency and severity. Using SIDER to compare the safety profiles of different opioids, the present study aims to provide valuable insights for guiding opioid selection during switching and related treatments. Specifically, this study highlights the distinct side-effect profiles of five strong opioids, namely morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, hydromorphone, and tapentadol, providing objective insights to guide opioid switching and optimize pain management in clinical settings, ultimately improving therapeutic options.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Target Opioids

Using SIDER 4.1, we extracted data on strong opioids used in palliative care in Japan [

15]. Based on the Guidelines for the Management of Cancer Pain [

19] by the Japanese Society for Palliative Medicine, we identified morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, hydromorphone, tapentadol, and methadone as strong opioids for this analysis.

2.2. Incidence Rates of Side Effects Associated with the Target Opioids

SIDER contains data on 1,430 drugs and 5,880 side-effect terms, yielding 140,064 drug–side-effect pairs [

15]. Each drug–side-effect combination includes incidence rate information derived from package inserts and literature. Drugs in SIDER are uniquely identified by a compound identifier (CID) assigned by the PubChem database of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Linking the drug name table to the side-effect frequency table via the CID enables evaluation of side-effect incidence rates for each drug.

SIDER’s frequency table categorizes incidence rates as

very common,

very frequent,

common,

frequent,

uncommon,

infrequent,

rare, and

very rare, corresponding to a 0–1 range. For instance,

very common and

very frequent indicate an incidence range of 0.1–1,

common and

frequent indicate 0.01–1,

uncommon and

infrequent indicate 0.001–0.01,

rare indicates 0–0.001, and

very rare indicates 0–0.0001. Some incidence rates in the 0–1 range are provided as numeric values. Approximately 52% of the drugs listed in SIDER include incidence rate data [

15]. However, the diverse sources of these rates, encompassing different clinical trials and severity levels, introduce variability that must be accounted for. To enable comparisons across opioids, we standardized the side-effect incidence rates for cluster analysis and principal component analysis (PCA), with these analyses described in sections 2.4 and 2.5, respectively.

2.3. Calculation of Side-Effect Incidence Rates for Target Opioids

The side-effect terms in SIDER 4.1 are mapped to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA). In this study, we used the lowest level term (LLT) in MedDRA version 16.1 to define side-effect terms.

We extracted the target opioids from SIDER and obtained the lower and upper bounds of the incidence rate for each LLT linked to these opioids, calculating the mean value of these bounds. For example, for the rare category, the lower bound, upper bound, and mean would be 0, 0.001, and 0.0005, respectively. We converted the mean values to percentages and applied a base-10 logarithmic transformation for analysis. For side effects with multiple reports, we used the median to calculate the incidence rate.

2.4. Cluster Analysis

Using the incidence rates of the target opioids’ side effects, we performed hierarchical cluster analysis using Ward’s method [

20]. We first extracted all side-effect names with reported incidence rates for every opioid studied. Cluster analysis was then conducted to compare side-effect incidence rates across opioids. Incidence rates were standardized, setting the mean and variance to 0 and 1, respectively, before clustering.

2.5. PCA

Based on the cluster analysis results, we performed PCA [

21] on side effects identified as having higher risks among the target opioids. PCA reduces dataset dimensionality to identify principal component axes that best explain variance, enabling efficient data visualization and interpretation. By plotting the score plot and loading vectors for each opioid and side effect, we interpreted the principal components and clarified relationships between drugs and side effects. This analysis used the correlation matrix.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data handling in the SIDER database, cluster analysis, and PCA were conducted using JMP Pro 18.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

3. Results

3.1. Target Opioids and Side Effects

The strong opioids approved for use in Japan are morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, hydromorphone, tapentadol, and methadone. However, owing to the lack of incidence rate data on side effects for methadone in SIDER, we focused only on morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, hydromorphone, and tapentadol. For these five opioids, we extracted all side-effect names and their corresponding incidence rates from SIDER, resulting in 191 side-effect names (

Table S1). Among these, only 10 side effects were commonly listed across all 5 target opioids: nausea, dizziness, headache, somnolence, vomiting, constipation, dry mouth, hyperhidrosis, pruritus, and asthenia. The remaining 181 side effects lacked incidence information for at least one opioid. Thus, the 10 side effects, for which data were available across all studied opioids, were selected for further analysis, as they were the most useful for profiling side-effect differences. Accordingly, cluster analysis and PCA were conducted based on the incidence rates of these 10 side effects.

3.2. Cluster Analysis

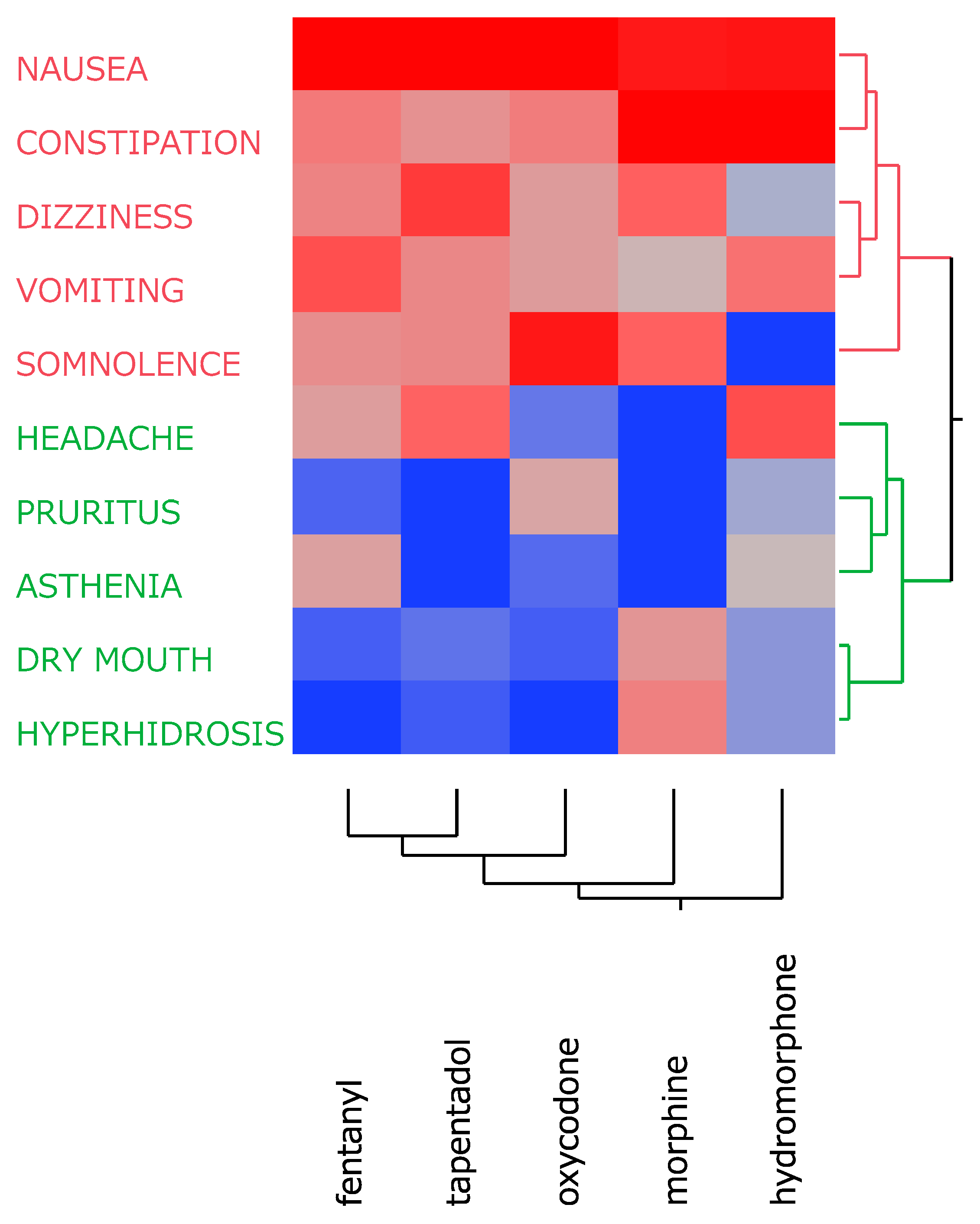

A cluster analysis based on the incidence rates of the 10 side effects divided them into two distinct clusters (

Figure 1). Cluster 1 (red) included side effects (nausea, constipation, dizziness, vomiting, and somnolence) with relatively high incidence rates across all opioids. Cluster 2 (green) comprised side effects (headache, pruritus, asthenia, dry mouth, and hyperhidrosis) that exhibited relatively low incidence rates. These classification results were further explored using PCA to better understand the relationships among these side effects and highlight the distinguishing characteristics of each opioid.

3.3. PCA

From the cluster analysis, five side effects (nausea, constipation, dizziness, vomiting, and somnolence) were identified as having relatively high incidence across all opioids. These side effects were further examined using PCA (

Figure 2). The first and second principal components explained 40.9% and 34.2% of the total variance, respectively, for a cumulative total of 75.0%. The loading vectors revealed that nausea, vomiting, constipation, and somnolence were strongly associated with these principal components. Based on the score plot and loading vectors, the analysis highlighted distinct opioid–side-effect relationships. Fentanyl was found to have a higher incidence of nausea and vomiting compared with the other opioids, whereas tapentadol showed a relatively strong tendency for nausea. Oxycodone was prominently associated with somnolence, whereas morphine was more likely to induce both constipation and somnolence. Hydromorphone was found to cause constipation and vomiting more frequently compared with the other opioids.

4. Discussion

The five strong opioids investigated in this study, namely morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, hydromorphone, and tapentadol, are administered in Japan, particularly for managing severe cancer pain in palliative care. In clinical practice, opioid switching, or adjusting the opioid based on the patient’s clinical status, is an important strategy for optimizing analgesia and side-effect management [

22]. For example, if an opioid causes severe constipation, switching to an alternative with a lower incidence of this side effect may improve the patient’s condition. This approach can be similarly applied to other side effects. Despite the wide variety of side effects reported for different opioids, few studies have comprehensively compared them. For instance, the “Guidelines for the Pharmacological Treatment of Cancer Pain (2020 Edition)” [

19] from the Japanese Society for Palliative Medicine note that tapentadol induces fewer instances of constipation, vomiting, and neurological symptoms compared with oxycodone or morphine [

23,

24,

25]. However, this provides only a limited perspective on the broader side-effect profiles of strong opioids. In contrast, the present study used the SIDER database to comprehensively analyze the incidence rates of major side effects for five strong opioids, providing objective data to support opioid switching decisions.

Because the incidence rate data in SIDER are compiled from various clinical trials and literature sources, they may vary in dosage and severity levels across study populations [

15,

16]. For example, morphine does not have a clear ceiling effect for its analgesic action, and higher doses may enhance pain relief [

26]. As such, datasets containing high-dose cases may indicate higher side-effect incidence rates. To address this, we standardized these rates for each opioid during our cluster analysis and PCA, allowing for more meaningful cross-opioid comparisons.

4.1. Comparison with Previous Studies by Side-Effect Category

4.1.1. Nausea/Vomiting

Cluster analysis divided the 10 side effects into high- and low-incidence groups. Among the high-incidence group, nausea and vomiting were common across all five opioids [

6,

27,

28], with these side effects being especially problematic in chronic pain management, as they can reduce therapeutic effectiveness [

27]. Nausea and vomiting triggered by central and peripheral MOR stimulation can result in major discomfort for patients [

6,

28]. Our PCA results showed that fentanyl and tapentadol were more likely to induce nausea and vomiting. Previous studies have reported an increased risk of vomiting within 24 h of fentanyl administration [

29,

30] and a higher incidence of nausea and vomiting during double-blind maintenance periods with tapentadol [

31], aligning with our findings.

4.1.2. Constipation

Constipation is primarily caused by the peripheral effects of MOR stimulation, which relaxes the smooth muscle in the gastrointestinal tract [

32,

33], making it one of the most common opioid side effects. Our study suggests that morphine and hydromorphone are more likely to induce constipation. Previous research has extensively documented morphine-induced constipation [

34,

35,

36], and our PCA reinforced morphine’s prominent association with this side effect. Conversely, switching to tapentadol may help reduce constipation incidence, making it a viable option for patients experiencing severe constipation.

4.1.3. Somnolence

Somnolence [

37], a central nervous system effect induced by opioids, was categorized in the high-incidence group, being particularly prominent with oxycodone and morphine. Previous studies [

38,

39,

40] have similarly reported more frequent oxycodone-induced central side effects, such as somnolence and vomiting, consistent with our PCA outcomes. In contrast, hydromorphone appears to cause relatively less somnolence, indicating that it may be a suitable option for cases where minimizing sedation is a priority [

41,

42].

4.1.4. Dizziness

Dizziness [

43] was also placed in the high-incidence group, reflecting another central nervous system effect of opioids. In our study, PCA positioned dizziness alongside nausea and somnolence in the positive direction of the first principal component, suggesting a correlation with other central nervous system side effects. However, as fewer prior studies have explicitly focused on dizziness, further clinical research is needed to deepen our understanding of this side effect.

4.1.4. Headache, Pruritus, Asthenia, Dry Mouth, and Hyperhidrosis

Headache, pruritus, asthenia, dry mouth, and hyperhidrosis were placed in the low-incidence group during cluster analysis. However, hydromorphone and tapentadol have been noted to induce headaches more frequently [

44], whereas morphine is associated with dry mouth [

45] and hyperhidrosis [

46]. Our findings support these observations and underscore the importance of close monitoring for these less common side effects in clinical practice.

4.2. Overall Implications from PCA

Our PCA focused on the five high-frequency side effects, namely nausea, vomiting, constipation, somnolence, and dizziness, identified through cluster analysis. The first and second principal components explained approximately 75% of the data variance, with the first distinguishing between central factors (nausea, vomiting, somnolence, and dizziness) and peripheral factors (constipation) while the second further separated vomiting and somnolence. This analysis allowed us to visualize the distinct risk profiles of each opioid. Morphine and hydromorphone were more strongly associated with constipation, fentanyl and tapentadol with nausea and vomiting, and oxycodone with somnolence (

Figure 2).

4.3. Application to Opioid Switching

These findings provide valuable guidance for clinicians when considering opioid switching strategies. For instance, patients experiencing severe constipation may benefit from switching to tapentadol, whereas those suffering from pronounced nausea or vomiting may find relief by transitioning to opioids with a lower incidence of these side effects. The comprehensive side-effect profiles revealed through our analysis can support the advancement of personalized medicine by optimizing opioid selection based on each patient’s specific clinical needs.

4.4. Limitations

Kuhn et al. [

16] noted that the SIDER database lacks incidence rate data for 39% of all drug–side-effect pairs, which may hinder a complete understanding of the full scope of side effects. In this study, we were also unable to obtain sufficient side-effect data for methadone, a commonly used opioid in palliative care, as well as for certain other drugs and side effects, resulting in notable data gaps. The SIDER database’s website [

15] states that many medical concepts not directly representing side effects have been excluded, emphasizing the need for further data accumulation, including real-world datasets, such as FAERS.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we used the pharmaceutical information in the SIDER database to comprehensively analyze side-effect incidence rates of five strong opioids commonly used in Japan: morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, hydromorphone, and tapentadol. Through cluster analysis and PCA, we identified the distinct side-effect profiles associated with each opioid. Although all opioids commonly induced central side effects, such as nausea and vomiting, specific opioids differed in their propensity for causing constipation or somnolence, with some also exhibiting higher or lower frequencies of headache and dry mouth incidences. PCA further highlighted opioids particularly prone to causing constipation (morphine and hydromorphone) or nausea and vomiting (fentanyl and tapentadol), as well as those associated with somnolence (oxycodone). These insights can serve as objective indicators for opioid switching decisions, helping reduce adverse effects, such as constipation or nausea/vomiting, and enabling continued pain management in clinical settings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Detailed Side Effects and Incidence Rates of Strong Opioids Based on Data from the SIDER Database.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.U.; methodology, Y.U.; software, Y.U.; validation, R.H. and Y.U.; formal analysis, R.H. and Y.U.; investigation, R.H. and Y.U.; resources, R.H. and Y.U.; data curation, R.H. and Y.U.; writing—original draft preparation, R.H.; writing—review and editing, R.H., M.K. and Y.U.; visualization, R.H. and Y.U.; supervision, Y.U.; project administration, Y.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LLT |

Lowest level term |

| PCA |

Principal component analysis |

| PPPD |

Persistent postural-perceptual dizziness |

| SIDER |

Side Effect Resource |

References

- Corder, G.; Doolen, S.; Donahue, R.R.; Winter, M.K.; Jutras, B.L.; He, Y.; Hu, X.; Wieskopf, J.S.; Mogil, J.S.; Storm, D.R. Constitutive μ-opioid receptor activity leads to long-term endogenous analgesia and dependence. Science 2013, 341, 1394–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeim, A.; Dy, S.M.; Lorenz, K.A.; Sanati, H.; Walling, A.; Asch, S.M. Evidence-based recommendations for cancer nausea and vomiting. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 3903–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japan Society of Clinical Oncology. Available online: http://www.jsco-cpg.jp/.

- Wiffen, P.J.; Wee, B.; Derry, S.; Bell, R.F.; Moore, R.A. Opioids for cancer pain – an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 7, CD012592. [Google Scholar]

- Els, C.; Jackson, T.D.; Kunyk, D.; Lappi, V.G.; Sonnenberg, B.; Hagtvedt, R.; Sharma, S.; Kolahdooz, F.; Straube, S. Adverse events associated with medium- and long-term use of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: an overview of cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 10, CD012509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Benyamin, R. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician 2008, 11, S105–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichter, I. Results of antiemetic management in terminal illness. J. Palliat. Care 1993, 9, 19–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passik, S.D.; Lundberg, J.; Kirsh, K.L.; Theobald, D.; Donaghy, K.; Holtsclaw, E.; Cooper, M.; Dugan, W. A pilot exploration of the antiemetic activity of olanzapine for the relief of nausea in patients with advanced cancer and pain. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2002, 23, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agra, Y.; Sacristán, A.; González, M.; Ferrari, M.; Portugués, A.; Calvo, M.J. Efficacy of senna versus lactulose in terminal cancer patients treated with opioids. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 1998, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mystakidou, K.; Tsilika, E.; Parpa, E.; Kouloulias, V.; Kouvaris, I.; Georgaki, S.; Vlahos, L. Long-term cancer pain management in morphine pre-treated and opioid naive patients with transdermal fentanyl. Int. J. Cancer 2003, 107, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitbart, W.; Marotta, R.; Platt, M. M.; Weisman, H.; Derevenco, M.; Grau, C.; Corbera, K.; Raymond, S.; Lund, S.; Jacobson, P. A double-blind trial of haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and lorazepam in the treatment of delirium in hospitalized AIDS patients. Am. J. Psychiat. 1996, 153, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candy, B.; Jackson, K.C.; Jones, L.; Leurent, B.; Tookman, A.; King, M. Drug therapy for delirium in terminally ill adult patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enting, R.H.; Oldenmenger, W.H.; van der Rijt, C.C.D.; Wilms, E.B.; Elfrink, E.J.; Elswijk, I.; Sillevis Smitt, P.A.E. A prospective study evaluating the response of patients with unrelieved cancer pain to parenteral opioids. Cancer 2002, 94, 3049–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawatari, H.; Shinjo, T.; Morita, T.; Kohara, H.; Yomiya, K. Revision of pharmacological treatment recommendations for cancer pain: clinical guidelines from the Japanese Society of Palliative Medicine. J. Palliat. Med. 2022, 25, 1095–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SIDER Side Effect Resource. Available online: http://sideeffects.embl.de/.

- Kuhn, M.; Letunic, I.; Jensen, L.J.; Bork, P. The SIDER database of drugs and side effects. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D1075–D1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M.; Campillos, M.; Letunic, I.; Jensen, L.J.; Bork, P. A side effect resource to capture phenotypic effects of drugs. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2010, 6, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, E.; Govind, R.; Romero, A.; Dzahini, O.; Broadbent, M.; Stewart, R.; Smith, T.; Kim, C.-H.; Werbeloff, N.; MacCabe, J.H. The side effect profile of clozapine in real world data of three large mental health hospitals. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidelines for the Pharmacological Treatment of Cancer Pain. Available online: https://www.jspm.ne.jp/publication/guidelines/individual.html?entry_id=85.

- Murtagh, F.; Legendre, P. Ward’s hierarchical agglomerative clustering method: which algorithms implement ward’s criterion? J. Classif. 2014, 31, 274–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: a review and recent developments. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercadante, S.; Bruera, E. Opioid switching in cancer pain: from the beginning to nowadays. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hemat. 2016, 99, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, M.; Upmalis, D.; Okamoto, A.; Lange, C.; Rauschkolb, C. Tolerability of tapentadol immediate release in patients with lower back pain or osteoarthritis of the hip or knee over 90 days: a randomized, double-blind study. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2009, 25, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etropolski, M.; Kelly, K.; Okamoto, A.; Rauschkolb, C. Comparable efficacy and superior gastrointestinal tolerability (nausea, vomiting, constipation) of tapentadol compared with oxycodone hydrochloride. Adv. Ther. 2011, 28, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imanaka, K.; Tominaga, Y.; Etropolski, M.; Ohashi, H.; Hirose, K.; Matsumura, T. Ready conversion of patients with well-controlled, moderate to severe, chronic malignant tumor–related pain on other opioids to tapentadol extended release. Clin. Drug Invest. 2014, 34, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.G.; Raymond, B.L. Lack of evidence for ceiling effect for buprenorphine analgesia in humans. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 127, 310–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, W.; Shahbaz, O.; Teskey, G.; Beever, A.; Kachour, N.; Venketaraman, V.; Darmani, N.A. Mechanisms of nausea and vomiting: current knowledge and recent advances in intracellular emetic signaling systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porreca, F.; Ossipov, M.H. Nausea and vomiting side effects with opioid analgesics during treatment of chronic pain: mechanisms, implications, and management options. Pain Med. 2009, 10, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Doo, A.R.; Son, J.-S.; Kim, J.-W.; Lee, K.-J.; Kim, D.-C.; Ko, S. Effects of intraoperative single bolus fentanyl administration and remifentanil infusion on postoperative nausea and vomiting. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2016, 69, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varrassi, G.; Celleno, D.; Capogna, G.; Costantino, P.; Emanuelli, M.; Sebastiani, M.; Pesce, A.F.; Niv, D. Ventilatory effects of subarachnoid fentanyl in the elderly. Anaesthesia 1992, 47, 558–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.; Etropolski, M.S.; Shapiro, D.Y.; Rauschkolb, C.; Vinik, A.I.; Lange, B.; Cooper, K.; Van Hove, I.; Haeussler, J. A pooled analysis evaluating the efficacy and tolerability of tapentadol extended release for chronic, painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Clin. Drug Invest. 2015, 35, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Chung, H.H.; Cheng, J. T. Opiate-induced constipation related to activation of small intestine opioid μ2-receptors. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmadi, M.; Ahmad, D.; Hewlett, A. Efficacy of naldemedine for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation: a meta-analysis. J. Gastrointestin. Liver Dis. 2019, 28, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbarali, H.I.; Inkisar, A.; Dewey, W.L. Site and mechanism of morphine tolerance in the gastrointestinal tract. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2014, 26, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kon, R.; Ikarashi, N.; Hayakawa, A.; Haga, Y.; Fueki, A.; Kusunoki, Y.; Tajima, M.; Ochiai, W.; Machida, Y.; Sugiyama, K. Morphine-induced constipation develops with increased aquaporin-3 expression in the colon via increased serotonin secretion. Toxicol. Sci. 2015, 145, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, G.R.; Gabra, B.H.; Dewey, W.L.; Akbarali, H.I. Morphine tolerance in the mouse ileum and colon. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008, 327, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.-T.; Hang, L.; Liu, T. Mu opioid receptor heterodimers emerge as novel therapeutic targets: recent progress and future perspective. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.S.; Lee, J.S.; Park, S.Y.; Ryu, A.; Chun, H.R.; Chung, H.S.; Kang, K.S.; Chung, J.H.; Jung, K.T.; Mun, S.T. Oxycodone versus fentanyl for intravenous patient-controlled analgesia after laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy: A prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017, 96, e6286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaskell, H.; Derry, S.; Moore, R.A.; McQuay, H.J. Single dose oral oxycodone and oxycodone plus paracetamol (acetaminophen) for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 8, CD002763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay, B. A double-blind comparison of morphine and buprenorphine in the prevention of pain after operation. Br. J. Anaesth. 1978, 50, 605–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.J.; Hou, W.; Kong, X.Y.; Yang, L.; Xia, J.; Hua, B.J.; Knaggs, R. Hydromorphone for cancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Tao, S.J. Effects of hydromorphone and morphine intravenous analgesia on plasma motilin and postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing total hysterectomy. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 5697–5703. [Google Scholar]

- Im, J.J.; Na, S.; Kang, S.; Jeong, H.; Lee, E.-S.; Lee, T.-K.; Ahn, W.-Y.; Chung, Y.-A.; Song, I.-U. A randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled trial of transcranial direct current stimulation for the treatment of persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD). Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 868976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalamachu, S.R.; Kutch, M.; Hale, M.E. Safety and tolerability of once-daily OROS® hydromorphone extended-release in opioid-tolerant adults with moderate-to-severe chronic cancer and noncancer pain: pooled analysis of 11 clinical studies. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2012, 44, 852–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glare, P.; Walsh, D.; Sheehan, D. The adverse effects of morphine: a prospective survey of common symptoms during repeated dosing for chronic cancer pain. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2006, 23, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kardaun, S.H.; de Monchy, J.G. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis caused by morphine, confirmed by positive patch test and lymphocyte transformation test. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2006, 55, S21–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).