Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

11 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Sigma-1 Receptor: Structure, Functions and Pharmacology

3. Sigma-1 Receptor in Nerve Injury

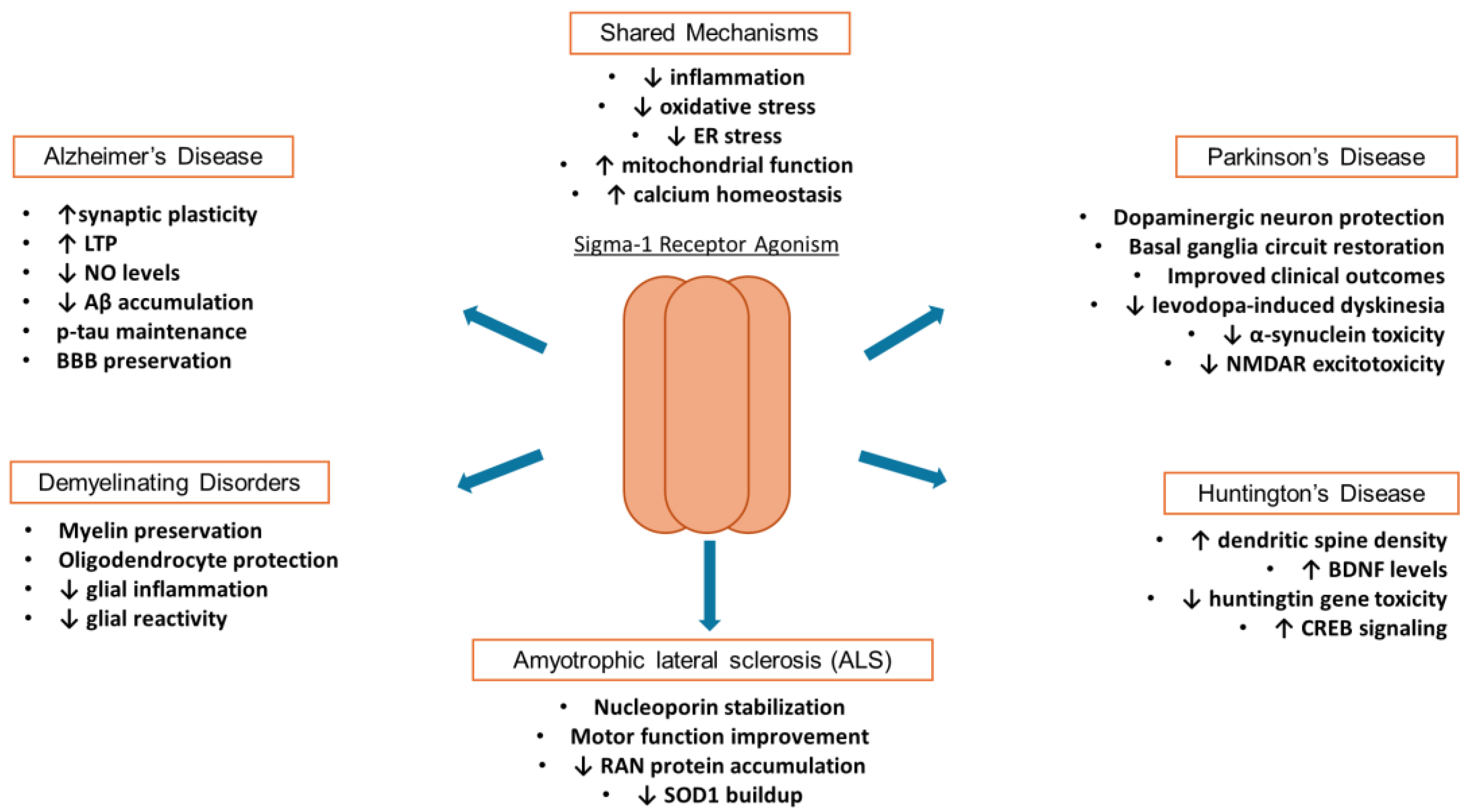

4. Sigma-1 Receptor in Neurodegenerative Disorders

4.1. Sigma-1 Receptor in Alzheimer’s Disease

4.2. Sigma-1 Receptor in Demyelinating Disorders

4.3. Sigma-1 Receptor in ALS

4.4. Sigma-1 Receptor in Huntington’s Disease

4.5. Sigma-1 Receptor in Parkinson’s Disease

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martin, W.R.; Eades, C.G.; Thompson, J.A.; Huppler, R.E.; Gilbert, P.E. The effects of morphine- and nalorphine- like drugs in the nondependent and morphine-dependent chronic spinal dog. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1976, 197, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, S.W.; Cook, L. Sigma opiates and certain antipsychotic drugs mutually inhibit (+)-[3H] SKF 10,047 and [3H]haloperidol binding in guinea pig brain membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1984, 81, 5618–5621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.P. Evidence for sigma opioid receptor: binding of [3H]SKF-10047 to etorphine-inaccessible sites in guinea-pig brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1982, 223, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirion, R.; Bowen, W.D.; Itzhak, Y.; Junien, J.L.; Musacchio, J.M.; Rothman, R.B.; Su, T.P.; Tam, S.W.; Taylor, D.P. A proposal for the classification of sigma binding sites. Trends Pharmacol Sci 1992, 13, 85–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanner, M.; Moebius, F.F.; Flandorfer, A.; Knaus, H.G.; Striessnig, J.; Kempner, E.; Glossmann, H. Purification, molecular cloning, and expression of the mammalian sigma1-binding site. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996, 93, 8072–8077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alon, A.; Schmidt, H.R.; Wood, M.D.; Sahn, J.J.; Martin, S.F.; Kruse, A.C. Identification of the gene that codes for the sigma(2) receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, 7160–7165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, T.P.; Hayashi, T. Understanding the molecular mechanism of sigma-1 receptors: towards a hypothesis that sigma-1 receptors are intracellular amplifiers for signal transduction. Curr Med Chem 2003, 10, 2073–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Su, T. The sigma receptor: evolution of the concept in neuropsychopharmacology. Curr Neuropharmacol 2005, 3, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C.P.; Mahen, R.; Schnell, E.; Djamgoz, M.B.; Aydar, E. Sigma-1 receptors bind cholesterol and remodel lipid rafts in breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Res 2007, 67, 11166–11175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, P.D.; Li, H.W.; Fei, Y.J.; Ganapathy, M.E.; Fujita, T.; Plumley, L.H.; Yang-Feng, T.L.; Leibach, F.H.; Ganapathy, V. Exon-intron structure, analysis of promoter region, and chromosomal localization of the human type 1 sigma receptor gene. J Neurochem 1998, 70, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekuda, R.; Prasad, P.D.; Fei, Y.J.; Leibach, F.H.; Ganapathy, V. Cloning and functional expression of the human type 1 sigma receptor (hSigmaR1). Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1996, 229, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seth, P.; Leibach, F.H.; Ganapathy, V. Cloning and structural analysis of the cDNA and the gene encoding the murine type 1 sigma receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1997, 241, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.R.; Zheng, S.; Gurpinar, E.; Koehl, A.; Manglik, A.; Kruse, A.C. Crystal structure of the human σ1 receptor. Nature 2016, 532, 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoni, M.; Kiefer, F.; Biasini, M.; Bordoli, L.; Schwede, T. Modeling protein quaternary structure of homo- and hetero-oligomers beyond binary interactions by homology. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 10480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.C. Distinct Regulation of sigma (1) Receptor Multimerization by Its Agonists and Antagonists in Transfected Cells and Rat Liver Membranes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2020, 373, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, G.; Moreno, E.; Bonaventura, J.; Brugarolas, M.; Farré, D.; Aguinaga, D.; Mallol, J.; Cortés, A.; Casadó, V.; Lluís, C.; et al. Cocaine inhibits dopamine D2 receptor signaling via sigma-1-D2 receptor heteromers. PLoS One 2013, 8, e61245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguinaga, D.; Medrano, M.; Vega-Quiroga, I.; Gysling, K.; Canela, E.I.; Navarro, G.; Franco, R. Cocaine Effects on Dopaminergic Transmission Depend on a Balance between Sigma-1 and Sigma-2 Receptor Expression. Front Mol Neurosci 2018, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontanilla, D.; Hajipour, A.R.; Pal, A.; Chu, U.B.; Arbabian, M.; Ruoho, A.E. Probing the steroid binding domain-like I (SBDLI) of the sigma-1 receptor binding site using N-substituted photoaffinity labels. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 7205–7217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Su, T.P. Sigma-1 receptors (sigma(1) binding sites) form raft-like microdomains and target lipid droplets on the endoplasmic reticulum: roles in endoplasmic reticulum lipid compartmentalization and export. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2003, 306, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Su, T.P. Sigma-1 receptors at galactosylceramide-enriched lipid microdomains regulate oligodendrocyte differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004, 101, 14949–14954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreselassie, D.; Bowen, W.D. Sigma-2 receptors are specifically localized to lipid rafts in rat liver membranes. Eur J Pharmacol 2004, 493, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zeng, C.; Chu, W.; Pan, F.; Rothfuss, J.M.; Zhang, F.; Tu, Z.; Zhou, D.; Zeng, D.; Vangveravong, S.; et al. Identification of the PGRMC1 protein complex as the putative sigma-2 receptor binding site. Nat Commun 2011, 2, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaupel, D.B. Naltrexone fails to antagonize the sigma effects of PCP and SKF 10,047 in the dog. Eur J Pharmacol 1983, 92, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, U.B.; Ruoho, A.E. Sigma Receptor Binding Assays. Curr Protoc Pharmacol 2015, 71, 1.34–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, T.; Su, T.P. Intracellular dynamics of sigma-1 receptors (sigma(1) binding sites) in NG108-15 cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2003, 306, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Su, T.P. Sigma-1 receptor chaperones at the ER-mitochondrion interface regulate Ca(2+) signaling and cell survival. Cell 2007, 131, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydar, E.; Palmer, C.P.; Klyachko, V.A.; Jackson, M.B. The sigma receptor as a ligand-regulated auxiliary potassium channel subunit. Neuron 2002, 34, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.P.; Hayashi, T.; Maurice, T.; Buch, S.; Ruoho, A.E. The sigma-1 receptor chaperone as an inter-organelle signaling modulator. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2010, 31, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brimson, J.M.; Brown, C.A.; Safrany, S.T. Antagonists show GTP-sensitive high-affinity binding to the sigma-1 receptor. Br J Pharmacol 2011, 164, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Blázquez, P.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, M.; Herrero-Labrador, R.; Burgueño, J.; Zamanillo, D.; Garzón, J. The calcium-sensitive Sigma-1 receptor prevents cannabinoids from provoking glutamate NMDA receptor hypofunction: implications in antinociception and psychotic diseases. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2014, 17, 1943–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilner, B.J.; John, C.S.; Bowen, W.D. Sigma-1 and sigma-2 receptors are expressed in a wide variety of human and rodent tumor cell lines. Cancer Res 1995, 55, 408–413. [Google Scholar]

- Bermack, J.E.; Debonnel, G. Distinct modulatory roles of sigma receptor subtypes on glutamatergic responses in the dorsal hippocampus. Synapse 2005, 55, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobos, E.J.; Entrena, J.M.; Nieto, F.R.; Cendán, C.M.; Del Pozo, E. Pharmacology and therapeutic potential of sigma(1) receptor ligands. Curr Neuropharmacol 2008, 6, 344–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, T.; Maurice, T.; Su, T.P. Ca(2+) signaling via sigma(1)-receptors: novel regulatory mechanism affecting intracellular Ca(2+) concentration. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2000, 293, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Su, T.P. Regulating ankyrin dynamics: Roles of sigma-1 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001, 98, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Su, T.P. Sigma-1 receptor ligands: potential in the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. CNS Drugs 2004, 18, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Fujimoto, M. Detergent-resistant microdomains determine the localization of sigma-1 receptors to the endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria junction. Mol Pharmacol 2010, 77, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnally, S.M.; Johannessen, M.; Henderson, R.M.; Jackson, M.B.; Edwardson, J.M. Demonstration of a direct interaction between sigma-1 receptors and acid-sensing ion channels. Biophys J 2010, 98, 1182–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crottès, D.; Martial, S.; Rapetti-Mauss, R.; Pisani, D.F.; Loriol, C.; Pellissier, B.; Martin, P.; Chevet, E.; Borgese, F.; Soriani, O. Sig1R protein regulates hERG channel expression through a post-translational mechanism in leukemic cells. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 27947–27958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasuriya, D.; Stewart, A.P.; Crottès, D.; Borgese, F.; Soriani, O.; Edwardson, J.M. The sigma-1 receptor binds to the Nav1.5 voltage-gated Na+ channel with 4-fold symmetry. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 37021–37029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourrich, S.; Hayashi, T.; Chuang, J.Y.; Tsai, S.Y.; Su, T.P.; Bonci, A. Dynamic interaction between sigma-1 receptor and Kv1.2 shapes neuronal and behavioral responses to cocaine. Cell 2013, 152, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, M.G.; Zager, E.L. Pathophysiology of peripheral nerve injury: a brief review. Neurosurg Focus 2004, 16, E1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.H.C.; Lee, M.H.H.; Wu, C.Y.C.; Couto, E.S.A.; Possoit, H.E.; Hsieh, T.H.; Minagar, A.; Lin, H.W. Cerebral ischemia and neuroregeneration. Neural Regen Res 2018, 13, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, S.Y.; Lee, A.Y.W. Traumatic Brain Injuries: Pathophysiology and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Front Cell Neurosci 2019, 13, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonfeld, E.; Johnstone, T.M.; Haider, G.; Shah, A.; Marianayagam, N.J.; Biswal, S.; Veeravagu, A. Sigma-1 receptor expression in a subpopulation of lumbar spinal cord microglia in response to peripheral nerve injury. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 14762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardai, S.; László, M.; Szabó, A.; Alpár, A.; Hanics, J.; Zahola, P.; Merkely, B.; Frecska, E.; Nagy, Z. N,N-dimethyltryptamine reduces infarct size and improves functional recovery following transient focal brain ischemia in rats. Exp Neurol 2020, 327, 113245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, M.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, P.; Yu, Z.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, J. Dexmedetomidine inhibits neuronal apoptosis by inducing Sigma-1 receptor signaling in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Aging (Albany NY) 2019, 11, 9556–9568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morihara, R.; Yamashita, T.; Liu, X.; Nakano, Y.; Fukui, Y.; Sato, K.; Ohta, Y.; Hishikawa, N.; Shang, J.; Abe, K. Protective effect of a novel sigma-1 receptor agonist is associated with reduced endoplasmic reticulum stress in stroke male mice. J Neurosci Res 2018, 96, 1707–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Naghavi, M.; Foreman, K.; Lim, S.; Shibuya, K.; Aboyans, V.; Abraham, J.; Adair, T.; Aggarwal, R.; Ahn, S.Y.; et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 2095–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, D.E.; Clifton, A.G.; Brown, M.M. Measurement of infarct size using MRI predicts prognosis in middle cerebral artery infarction. Stroke 1995, 26, 2272–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreihofer, D.A.; Dalwadi, D.; Kim, S.; Metzger, D.; Oppong-Gyebi, A.; Das-Earl, P.; Schetz, J.A. Treatment of Stroke at a Delayed Timepoint with a Repurposed Drug Targeting Sigma 1 Receptors. Transl Stroke Res 2024, 15, 1035–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Hao, X.; Zhou, L.; Song, Z.; Wei, T.; Chi, T.; Liu, P.; Ji, X.; et al. Sigma-1 Receptor Activation Improves Oligodendrogenesis and Promotes White-Matter Integrity after Stroke in Mice with Diabetic Mellitus. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, J.; Wang, R.; Jiang, M.; Ye, Q.; Smith, A.D.; Chen, J.; Shi, Y. Macrophages reprogram after ischemic stroke and promote efferocytosis and inflammation resolution in the mouse brain. CNS Neurosci Ther 2019, 25, 1329–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Li, Q.; Tao, W.; Qin, P.; Chen, J.; Yang, H.; Chen, J.; Liu, H.; Dai, Q.; Zhen, X. Sigma-1 receptor-regulated efferocytosis by infiltrating circulating macrophages/microglial cells protects against neuronal impairments and promotes functional recovery in cerebral ischemic stroke. Theranostics 2023, 13, 543–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabuki, Y.; Shinoda, Y.; Izumi, H.; Ikuno, T.; Shioda, N.; Fukunaga, K. Dehydroepiandrosterone administration improves memory deficits following transient brain ischemia through sigma-1 receptor stimulation. Brain Res 2015, 1622, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, T.; Suzuki, H.; Travis, Z.D.; Zhang, J.H. The Stroke-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption: Current Progress of Inspection Technique, Mechanism, and Therapeutic Target. Curr Neuropharmacol 2020, 18, 1187–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Yang, L.; Liu, P.; Ji, X.; Qi, X.; Wang, Z.; Chi, T.; Zou, L. Sigma-1 receptor activation alleviates blood-brain barrier disruption post cerebral ischemia stroke by stimulating the GDNF-GFRα1-RET pathway. Exp Neurol 2022, 347, 113867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Yu, S.; Ling, Y.; Hao, S.; Liu, J. The Protective Effects of Dexmedetomidine against Hypoxia/Reoxygenation-Induced Inflammatory Injury and Permeability in Brain Endothelial Cells Mediated by Sigma-1 Receptor. ACS Chem Neurosci 2021, 12, 1940–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Jin, H.; Zhu, Y.; Wan, Y.; Opoku, E.N.; Zhu, L.; Hu, B. Diverse Functions and Mechanisms of Pericytes in Ischemic Stroke. Curr Neuropharmacol 2017, 15, 892–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wei, Q.; Leng, S.; Li, C.; Han, B.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yao, H. Activation of Sigma-1 Receptor Enhanced Pericyte Survival via the Interplay Between Apoptosis and Autophagy: Implications for Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity in Stroke. Transl Stroke Res 2020, 11, 267–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dohmen, C.; Sakowitz, O.W.; Fabricius, M.; Bosche, B.; Reithmeier, T.; Ernestus, R.I.; Brinker, G.; Dreier, J.P.; Woitzik, J.; Strong, A.J.; et al. Spreading depolarizations occur in human ischemic stroke with high incidence. Ann Neurol 2008, 63, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leao, A.A. The slow voltage variation of cortical spreading depression of activity. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1951, 3, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, Í.; Varga, V.; Dvorácskó, S.; Farkas, A.E.; Körmöczi, T.; Berkecz, R.; Kecskés, S.; Menyhárt, Á.; Frank, R.; Hantosi, D.; et al. N,N-Dimethyltryptamine attenuates spreading depolarization and restrains neurodegeneration by sigma-1 receptor activation in the ischemic rat brain. Neuropharmacology 2021, 192, 108612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, R.O.S.; Losada, D.M.; Jordani, M.C.; Evora, P.; Castro, E.S.O. Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury Revisited: An Overview of the Latest Pharmacological Strategies. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.A.; Chen, X.Y.; Li, W.J.; Yang, J.H.; Lin, M.J.; Li, X.S.; Zeng, Y.F.; Chen, S.W.; Xie, Z.L.; Zhu, Z.L.; et al. Sigma-1 Receptor and Binding Immunoglobulin Protein Interact with Ulinastatin Contributing to a Protective Effect in Rat Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion. World Neurosurg 2022, 158, e488–e494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelfa, G.; Vavers, E.; Svalbe, B.; Serzants, R.; Miteniece, A.; Lauberte, L.; Grinberga, S.; Gukalova, B.; Dambrova, M.; Zvejniece, L. Reduced GFAP Expression in Bergmann Glial Cells in the Cerebellum of Sigma-1 Receptor Knockout Mice Determines the Neurobehavioral Outcomes after Traumatic Brain Injury. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; Liu, L.; Min, X.; Mi, L.; Chai, Y.; Chen, F.; Wang, J.; Yue, S.; Zhang, J.; Deng, Q.; et al. Activation of Sigma-1 Receptor Alleviates ER-Associated Cell Death and Microglia Activation in Traumatically Injured Mice. J Clin Med 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.; Ma, Y.; Ren, Z.; Xu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, B. Sigma-1 Receptor Modulates Neuroinflammation After Traumatic Brain Injury. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2016, 36, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Rosa, E.; Watson, M.R.; Sahn, J.J.; Hodges, T.R.; Schroeder, R.E.; Cintrón-Pérez, C.J.; Shin, M.K.; Yin, T.C.; Emery, J.L.; Martin, S.F.; et al. Neuroprotective Efficacy of a Sigma 2 Receptor/TMEM97 Modulator (DKR-1677) after Traumatic Brain Injury. ACS Chem Neurosci 2019, 10, 1595–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R.; Sui, C.; Diao, Y.; Shi, G.; Hu, X.; Hao, Z.; Li, C.; Hao, M.; Xie, M.; Zhu, T. Activation of the sigma-1 receptor ameliorates neuronal ferroptosis via IRE1α after spinal cord injury. Brain Res 2024, 1838, 149011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaja-Capdevila, N.; Hernández, N.; Yeste, S.; Reinoso, R.F.; Burgueño, J.; Montero, A.; Merlos, M.; Vela, J.M.; Herrando-Grabulosa, M.; Navarro, X. EST79232 and EST79376, Two Novel Sigma-1 Receptor Ligands, Exert Neuroprotection on Models of Motoneuron Degeneration. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny, E.M.; Fidan, E.; Yang, Q.; Anthonymuthu, T.S.; New, L.A.; Meyer, E.A.; Wang, H.; Kochanek, P.M.; Dixon, C.E.; Kagan, V.E.; et al. Ferroptosis Contributes to Neuronal Death and Functional Outcome After Traumatic Brain Injury. Crit Care Med 2019, 47, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurice, T.; Su, T.P. The pharmacology of sigma-1 receptors. Pharmacol Ther 2009, 124, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urani, A.; Romieu, P.; Roman, F.J.; Maurice, T. Enhanced antidepressant effect of sigma(1) (sigma(1)) receptor agonists in beta(25-35)-amyloid peptide-treated mice. Behav Brain Res 2002, 134, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, I.; Giamogante, F.; Barazzuol, L.; Battista, T.; Fiorillo, A.; Vicario, M.; D'Alessandro, G.; Cipriani, R.; Limatola, C.; Rossi, D.; et al. Sorcin is an early marker of neurodegeneration, Ca(2+) dysregulation and endoplasmic reticulum stress associated to neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Halliday, G.; Dobson-Stone, C.; Wang, Y.; Tang, H.D.; Cao, L.; Deng, Y.L.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Y.M.; et al. Genetic polymorphisms in sigma-1 receptor and apolipoprotein E interact to influence the severity of Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 2011, 8, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luty, A.A.; Kwok, J.B.; Dobson-Stone, C.; Loy, C.T.; Coupland, K.G.; Karlström, H.; Sobow, T.; Tchorzewska, J.; Maruszak, A.; Barcikowska, M.; et al. Sigma nonopioid intracellular receptor 1 mutations cause frontotemporal lobar degeneration-motor neuron disease. Ann Neurol 2010, 68, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saif, A.; Al-Mohanna, F.; Bohlega, S. A mutation in sigma-1 receptor causes juvenile amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2011, 70, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, M.A.; McCann, K.; Lalande, M.J.; Thivierge, J.P.; Bergeron, R. Sigma receptor type 1 knockout mice show a mild deficit in plasticity but no significant change in synaptic transmission in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. J Neurochem 2016, 138, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naia, L.; Ly, P.; Mota, S.I.; Lopes, C.; Maranga, C.; Coelho, P.; Gershoni-Emek, N.; Ankarcrona, M.; Geva, M.; Hayden, M.R.; et al. The Sigma-1 Receptor Mediates Pridopidine Rescue of Mitochondrial Function in Huntington Disease Models. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 1017–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisak, R.P.; Nedelkoska, L.; Benjamins, J.A. Sigma-1 receptor agonists as potential protective therapies in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol 2020, 342, 577188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francardo, V. Sigma-1 receptor: a potential new target for Parkinson's disease? Neural Regen Res 2014, 9, 1882–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.; Kaushal, N.; Robson, M.J.; Matsumoto, R.R. Sigma receptors as potential therapeutic targets for neuroprotection. Eur J Pharmacol 2014, 743, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Hegarty, E.; Sahn, J.J.; Scott, L.L.; Gökçe, S.K.; Martin, C.; Ghorashian, N.; Satarasinghe, P.N.; Iyer, S.; Sae-Lee, W.; et al. High-Content Microfluidic Screening Platform Used To Identify σ2R/Tmem97 Binding Ligands that Reduce Age-Dependent Neurodegeneration in C. elegans SC_APP Model. ACS Chem Neurosci 2018, 9, 1014–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenoir, S.; Lahaye, R.A.; Vitet, H.; Scaramuzzino, C.; Virlogeux, A.; Capellano, L.; Genoux, A.; Gershoni-Emek, N.; Geva, M.; Hayden, M.R.; et al. Pridopidine rescues BDNF/TrkB trafficking dynamics and synapse homeostasis in a Huntington disease brain-on-a-chip model. Neurobiol Dis 2022, 173, 105857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geva, M.; Kusko, R.; Soares, H.; Fowler, K.D.; Birnberg, T.; Barash, S.; Wagner, A.M.; Fine, T.; Lysaght, A.; Weiner, B.; et al. Pridopidine activates neuroprotective pathways impaired in Huntington Disease. Hum Mol Genet 2016, 25, 3975–3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Nagappan, G.; Guan, X.; Nathan, P.J.; Wren, P. BDNF-based synaptic repair as a disease-modifying strategy for neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013, 14, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyagi, T.; Goto, S.; Bhardwaj, A.; Dawson, V.L.; Hurn, P.D.; Kirsch, J.R. Neuroprotective effect of sigma(1)-receptor ligand 4-phenyl-1-(4-phenylbutyl) piperidine (PPBP) is linked to reduced neuronal nitric oxide production. Stroke 2001, 32, 1613–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagnerova, K.; Hurn, P.D.; Bhardwaj, A.; Kirsch, J.R. Sigma 1 receptor agonists act as neuroprotective drugs through inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Anesth Analg 2006, 103, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zampieri, D.; Fortuna, S.; Calabretti, A.; Romano, M.; Menegazzi, R.; Schepmann, D.; Wünsch, B.; Collina, S.; Zanon, D.; Mamolo, M.G. Discovery of new potent dual sigma receptor/GluN2b ligands with antioxidant property as neuroprotective agents. Eur J Med Chem 2019, 180, 268–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rui, M.; Rossino, G.; Coniglio, S.; Monteleone, S.; Scuteri, A.; Malacrida, A.; Rossi, D.; Catenacci, L.; Sorrenti, M.; Paolillo, M.; et al. Identification of dual Sigma1 receptor modulators/acetylcholinesterase inhibitors with antioxidant and neurotrophic properties, as neuroprotective agents. Eur J Med Chem 2018, 158, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.C.; Lin, S.H.; Lee, P.T.; Yeh, S.H.; Hsieh, T.H.; Chou, S.Y.; Su, T.P.; Hung, J.J.; Chang, W.C.; Lee, Y.C.; et al. The sigma-1 receptor-zinc finger protein 179 pathway protects against hydrogen peroxide-induced cell injury. Neuropharmacology 2016, 105, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrigiano, G. Homeostatic synaptic plasticity: local and global mechanisms for stabilizing neuronal function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2012, 4, a005736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, K.; Goda, Y. Unraveling mechanisms of homeostatic synaptic plasticity. Neuron 2010, 66, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepańska, K.; Bojarski, A.J.; Popik, P.; Malikowska-Racia, N. Novel object recognition test as an alternative approach to assessing the pharmacological profile of sigma-1 receptor ligands. Pharmacol Rep 2023, 75, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlholm, K.; Valle-León, M.; Fernández-Dueñas, V.; Ciruela, F. Pridopidine Reverses Phencyclidine-Induced Memory Impairment. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.S.; Koh, S.H. Neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disorders: the roles of microglia and astrocytes. Transl Neurodegener 2020, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Takemura, M.; Hisaoka-Nakashima, K.; Morioka, N. TLR4-TAK1-p38 MAPK pathway and HDAC6 regulate the expression of sigma-1 receptors in rat primary cultured microglia. J Pharmacol Sci 2020, 144, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orciani, C.; Do Carmo, S.; Foret, M.K.; Hall, H.; Bonomo, Q.; Lavagna, A.; Huang, C.; Cuello, A.C. Early treatment with an M1 and sigma-1 receptor agonist prevents cognitive decline in a transgenic rat model displaying Alzheimer-like amyloid pathology. Neurobiol Aging 2023, 132, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Gao, C.; Wang, Q.; Jia, X.; Tian, H.; Wei, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Guo, L. The sigma-1 receptor-TAMM41 axis modulates neuroinflammation and attenuates memory impairment during the latent period of epileptogenesis. Animal Model Exp Med 2025, 8, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Gao, T.; Jia, X.; Gao, C.; Tian, H.; Wei, Y.; Lu, W.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y. SKF83959 Attenuates Memory Impairment and Depressive-like Behavior during the Latent Period of Epilepsy via Allosteric Activation of the Sigma-1 Receptor. ACS Chem Neurosci 2022, 13, 3198–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiss, K.; Raffaele, M.; Vanella, L.; Murabito, P.; Prezzavento, O.; Marrazzo, A.; Aricò, G.; Castracani, C.C.; Barbagallo, I.; Zappalà, A.; et al. (+)-Pentazocine attenuates SH-SY5Y cell death, oxidative stress and microglial migration induced by conditioned medium from activated microglia. Neurosci Lett 2017, 642, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johri, A.; Beal, M.F. Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2012, 342, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavendish, J.Z.; Sarkar, S.N.; Colantonio, M.A.; Quintana, D.D.; Ahmed, N.; White, B.A.; Engler-Chiurazzi, E.B.; Simpkins, J.W. Mitochondrial Movement and Number Deficits in Embryonic Cortical Neurons from 3xTg-AD Mice. J Alzheimers Dis 2019, 70, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Lei, Z.G.; Chu, K.; Lam, O.J.H.; Chiang, C.Y.; Zhang, Z.J. N, N-Dimethyltryptamine, a natural hallucinogen, ameliorates Alzheimer's disease by restoring neuronal Sigma-1 receptor-mediated endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria crosstalk. Alzheimers Res Ther 2024, 16, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M.P.; LeVine, H. , 3rd. Alzheimer's disease and the amyloid-beta peptide. J Alzheimers Dis 2010, 19, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borbély, E.; Varga, V.; Szögi, T.; Schuster, I.; Bozsó, Z.; Penke, B.; Fülöp, L. Impact of Two Neuronal Sigma-1 Receptor Modulators, PRE084 and DMT, on Neurogenesis and Neuroinflammation in an Aβ(1-42)-Injected, Wild-Type Mouse Model of AD. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurice, T.; Volle, J.N.; Strehaiano, M.; Crouzier, L.; Pereira, C.; Kaloyanov, N.; Virieux, D.; Pirat, J.L. Neuroprotection in non-transgenic and transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease by positive modulation of σ(1) receptors. Pharmacol Res 2019, 144, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, H.; Iulita, M.F.; Gubert, P.; Flores Aguilar, L.; Ducatenzeiler, A.; Fisher, A.; Cuello, A.C. AF710B, an M1/sigma-1 receptor agonist with long-lasting disease-modifying properties in a transgenic rat model of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2018, 14, 811–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.; Bezprozvanny, I.; Wu, L.; Ryskamp, D.A.; Bar-Ner, N.; Natan, N.; Brandeis, R.; Elkon, H.; Nahum, V.; Gershonov, E.; et al. AF710B, a Novel M1/σ1 Agonist with Therapeutic Efficacy in Animal Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurodegener Dis 2016, 16, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahmy, V.; Long, R.; Morin, D.; Villard, V.; Maurice, T. Mitochondrial protection by the mixed muscarinic/σ1 ligand ANAVEX2-73, a tetrahydrofuran derivative, in Aβ25-35 peptide-injected mice, a nontransgenic Alzheimer's disease model. Front Cell Neurosci 2014, 8, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freyssin, A.; Carles, A.; Guehairia, S.; Rubinstenn, G.; Maurice, T. Fluoroethylnormemantine (FENM) shows synergistic protection in combination with a sigma-1 receptor agonist in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neuropharmacology 2024, 242, 109733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharyya, R.; Black, S.E.; Lotlikar, M.S.; Fenn, R.H.; Jorfi, M.; Kovacs, D.M.; Tanzi, R.E. Axonal generation of amyloid-β from palmitoylated APP in mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes. Cell Rep 2021, 35, 109134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, P.; Sehar, U.; Bisht, J.; Selman, A.; Culberson, J.; Reddy, P.H. Phosphorylated Tau in Alzheimer's Disease and Other Tauopathies. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.Y.; Pokrass, M.J.; Klauer, N.R.; Nohara, H.; Su, T.P. Sigma-1 receptor regulates Tau phosphorylation and axon extension by shaping p35 turnover via myristic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, 6742–6747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurice, T.; Strehaiano, M.; Duhr, F.; Chevallier, N. Amyloid toxicity is enhanced after pharmacological or genetic invalidation of the σ(1) receptor. Behav Brain Res 2018, 339, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Qi, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, C.; Jia, D. Activation of the sigma-1 receptor attenuates blood-brain barrier disruption by inhibiting amyloid deposition in Alzheimer's disease mice. Neurosci Lett 2022, 774, 136528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christmann, U.; Díaz, J.L.; Pascual, R.; Bordas, M.; Álvarez, I.; Monroy, X.; Porras, M.; Yeste, S.; Reinoso, R.F.; Merlos, M.; et al. Discovery of WLB-89462, a New Drug-like and Highly Selective σ(2) Receptor Ligand with Neuroprotective Properties. J Med Chem 2023, 66, 12499–12519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, B.; Sahn, J.J.; Ardestani, P.M.; Evans, A.K.; Scott, L.L.; Chan, J.Z.; Iyer, S.; Crisp, A.; Zuniga, G.; Pierce, J.T.; et al. Small molecule modulator of sigma 2 receptor is neuroprotective and reduces cognitive deficits and neuroinflammation in experimental models of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem 2017, 140, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uttara, B.; Singh, A.V.; Zamboni, P.; Mahajan, R.T. Oxidative stress and neurodegenerative diseases: a review of upstream and downstream antioxidant therapeutic options. Curr Neuropharmacol 2009, 7, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasbleiz, C.; Peyrel, A.; Tarot, P.; Sarniguet, J.; Crouzier, L.; Cubedo, N.; Delprat, B.; Rossel, M.; Maurice, T.; Liévens, J.C. Sigma-1 receptor agonist PRE-084 confers protection against TAR DNA-binding protein-43 toxicity through NRF2 signalling. Redox Biol 2022, 58, 102542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estévez-Silva, H.M.; Cuesto, G.; Romero, N.; Brito-Armas, J.M.; Acevedo-Arozena, A.; Acebes, Á.; Marcellino, D.J. Pridopidine Promotes Synaptogenesis and Reduces Spatial Memory Deficits in the Alzheimer's Disease APP/PS1 Mouse Model. Neurotherapeutics 2022, 19, 1566–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Suzuki, Y. Globoid cell leucodystrophy (Krabbe's disease): deficiency of galactocerebroside beta-galactosidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1970, 66, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papakyriakopoulou, P.; Valsami, G.; Dev, K.K. The Effect of Donepezil Hydrochloride in the Twitcher Mouse Model of Krabbe Disease. Mol Neurobiol 2024, 61, 8688–8701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, T.G.; Bundey, S.E. Wolfram (DIDMOAD) syndrome. J Med Genet 1997, 34, 838–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.T.; Nguyen, L.D.; Ehrlich, B.E. Boosting ER-mitochondria calcium transfer to treat Wolfram syndrome. Cell Calcium 2022, 104, 102572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouzier, L.; Danese, A.; Yasui, Y.; Richard, E.M.; Liévens, J.C.; Patergnani, S.; Couly, S.; Diez, C.; Denus, M.; Cubedo, N.; et al. Activation of the sigma-1 receptor chaperone alleviates symptoms of Wolfram syndrome in preclinical models. Sci Transl Med 2022, 14, eabh3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzmon, A.; Herrero, M.; Sharet-Eshed, R.; Gilad, Y.; Senderowitz, H.; Elroy-Stein, O. Drug Screening Identifies Sigma-1-Receptor as a Target for the Therapy of VWM Leukodystrophy. Front Mol Neurosci 2018, 11, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyes, K.; Weinstock-Guttman, B. Impact of diagnosis and early treatment on the course of multiple sclerosis. Am J Manag Care 2013, 19, s321–331. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Collina, S.; Rui, M.; Stotani, S.; Bignardi, E.; Rossi, D.; Curti, D.; Giordanetto, F.; Malacrida, A.; Scuteri, A.; Cavaletti, G. Are sigma receptor modulators a weapon against multiple sclerosis disease? Future Med Chem 2017, 9, 2029–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renton, A.E.; Majounie, E.; Waite, A.; Simon-Sanchez, J.; Rollinson, S.; Gibbs, J.R.; Schymick, J.C.; Laaksovirta, H.; van Swieten, J.C.; Myllykangas, L.; et al. A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron 2011, 72, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, S.; Ilieva, H.; Tamada, H.; Nomura, H.; Komine, O.; Endo, F.; Jin, S.; Mancias, P.; Kiyama, H.; Yamanaka, K. Mitochondria-associated membrane collapse is a common pathomechanism in SIGMAR1- and SOD1-linked ALS. EMBO Mol Med 2016, 8, 1421–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Horiuchi, M.; Murata, Y.; Komine, O.; Kawade, N.; Sobue, A.; Yamanaka, K. Sigma-1 receptor maintains ATAD3A as a monomer to inhibit mitochondrial fragmentation at the mitochondria-associated membrane in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Dis 2023, 179, 106031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, J.P.; De Calbiac, H.; Kabashi, E.; Barmada, S.J. Autophagy and ALS: mechanistic insights and therapeutic implications. Autophagy 2022, 18, 254–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.Y.; Wu, H.E.; Weng, E.F.; Wu, H.C.; Su, T.P.; Wang, S.M. Fluvoxamine Exerts Sigma-1R to Rescue Autophagy via Pom121-Mediated Nucleocytoplasmic Transport of TFEB. Mol Neurobiol 2024, 61, 5282–5294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez-Silva, H.M.; Mediavilla, T.; Giacobbo, B.L.; Liu, X.; Sultan, F.R.; Marcellino, D.J. Pridopidine modifies disease phenotype in a SOD1 mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur J Neurosci 2022, 55, 1356–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaja-Capdevila, N.; Hernández, N.; Navarro, X.; Herrando-Grabulosa, M. Sigma-1 Receptor is a Pharmacological Target to Promote Neuroprotection in the SOD1(G93A) ALS Mice. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 780588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, T.; Liu, Y.; Banez-Coronel, M.; Reid, T.; Pletnikova, O.; Lewis, J.; Miller, T.M.; Harms, M.B.; Falchook, A.E.; Subramony, S.H.; et al. RAN proteins and RNA foci from antisense transcripts in C9ORF72 ALS and frontotemporal dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, E4968–4977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.T.; Liévens, J.C.; Wang, S.M.; Chuang, J.Y.; Khalil, B.; Wu, H.E.; Chang, W.C.; Maurice, T.; Su, T.P. Sigma-1 receptor chaperones rescue nucleocytoplasmic transport deficit seen in cellular and Drosophila ALS/FTD models. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 5580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouleau, G.A.; Clark, A.W.; Rooke, K.; Pramatarova, A.; Krizus, A.; Suchowersky, O.; Julien, J.P.; Figlewicz, D. SOD1 mutation is associated with accumulation of neurofilaments in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol 1996, 39, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ionescu, A.; Gradus, T.; Altman, T.; Maimon, R.; Saraf Avraham, N.; Geva, M.; Hayden, M.; Perlson, E. Targeting the Sigma-1 Receptor via Pridopidine Ameliorates Central Features of ALS Pathology in a SOD1(G93A) Model. Cell Death Dis 2019, 10, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, J.B.; Gusella, J.F. Huntington's disease. Pathogenesis and management. N Engl J Med 1986, 315, 1267–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, C.; Naia, L.; Lopes, C.; Rego, A.C. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Huntington's Disease. Adv Exp Med Biol 2018, 1049, 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddings, C.R.; Arbez, N.; Akimov, S.; Geva, M.; Hayden, M.R.; Ross, C.A. Pridopidine protects neurons from mutant-huntingtin toxicity via the sigma-1 receptor. Neurobiol Dis 2019, 129, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenkman, M.; Geva, M.; Gershoni-Emek, N.; Hayden, M.R.; Lederkremer, G.Z. Pridopidine reduces mutant huntingtin-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress by modulation of the Sigma-1 receptor. J Neurochem 2021, 158, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusko, R.; Dreymann, J.; Ross, J.; Cha, Y.; Escalante-Chong, R.; Garcia-Miralles, M.; Tan, L.J.; Burczynski, M.E.; Zeskind, B.; Laifenfeld, D.; et al. Large-scale transcriptomic analysis reveals that pridopidine reverses aberrant gene expression and activates neuroprotective pathways in the YAC128 HD mouse. Mol Neurodegener 2018, 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bol'shakova, A.V.; Kraskovskaya, N.A.; Gainullina, A.N.; Kukanova, E.O.; Vlasova, O.L.; Bezprozvanny, I.B. Neuroprotective Effect of σ1-Receptors on the Cell Model of Huntington's Disease. Bull Exp Biol Med 2017, 164, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryskamp, D.; Wu, J.; Geva, M.; Kusko, R.; Grossman, I.; Hayden, M.; Bezprozvanny, I. The sigma-1 receptor mediates the beneficial effects of pridopidine in a mouse model of Huntington disease. Neurobiol Dis 2017, 97, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, A.; Auinger, P.; Kieburtz, K.; Geva, M.; Mehra, M.; Abler, V.; Grachev, I.D.; Gordon, M.F.; Savola, J.M.; Gandhi, S.; et al. Additional Safety and Exploratory Efficacy Data at 48 and 60 Months from Open-HART, an Open-Label Extension Study of Pridopidine in Huntington Disease. J Huntingtons Dis 2020, 9, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexoudi, A.; Alexoudi, I.; Gatzonis, S. Parkinson's disease pathogenesis, evolution and alternative pathways: A review. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2018, 174, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabresi, P.; Mechelli, A.; Natale, G.; Volpicelli-Daley, L.; Di Lazzaro, G.; Ghiglieri, V. Alpha-synuclein in Parkinson's disease and other synucleinopathies: from overt neurodegeneration back to early synaptic dysfunction. Cell Death Dis 2023, 14, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, B.; Chen, L. Sigma-1 receptor knockout increases α-synuclein aggregation and phosphorylation with loss of dopaminergic neurons in substantia nigra. Neurobiol Aging 2017, 59, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limegrover, C.S.; Yurko, R.; Izzo, N.J.; LaBarbera, K.M.; Rehak, C.; Look, G.; Rishton, G.; Safferstein, H.; Catalano, S.M. Sigma-2 receptor antagonists rescue neuronal dysfunction induced by Parkinson's patient brain-derived α-synuclein. J Neurosci Res 2021, 99, 1161–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetel, S.; Foucault-Fruchard, L.; Tronel, C.; Buron, F.; Vergote, J.; Bodard, S.; Routier, S.; Sérrière, S.; Chalon, S. Neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of a therapy combining agonists of nicotinic α7 and σ1 receptors in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Neural Regen Res 2021, 16, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wan, C.; He, T.; Han, C.; Zhu, K.; Waddington, J.L.; Zhen, X. Sigma-1 receptor regulates mitophagy in dopaminergic neurons and contributes to dopaminergic protection. Neuropharmacology 2021, 196, 108360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francardo, V.; Geva, M.; Bez, F.; Denis, Q.; Steiner, L.; Hayden, M.R.; Cenci, M.A. Pridopidine Induces Functional Neurorestoration Via the Sigma-1 Receptor in a Mouse Model of Parkinson's Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2019, 16, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Srivanitchapoom, P. Levodopa-induced Dyskinesia: Clinical Features, Pathophysiology, and Medical Management. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2017, 20, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, T.H.; Geva, M.; Steiner, L.; Orbach, A.; Papapetropoulos, S.; Savola, J.M.; Reynolds, I.J.; Ravenscroft, P.; Hill, M.; Fox, S.H.; et al. Pridopidine, a clinic-ready compound, reduces 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine-induced dyskinesia in Parkinsonian macaques. Mov Disord 2019, 34, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.H.; Metman, L.V.; Nutt, J.G.; Brodsky, M.; Factor, S.A.; Lang, A.E.; Pope, L.E.; Knowles, N.; Siffert, J. Trial of dextromethorphan/quinidine to treat levodopa-induced dyskinesia in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2017, 32, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Sukumaran, P.; Singh, B.B. Sigma1 Receptor Inhibits TRPC1-Mediated Ca(2+) Entry That Promotes Dopaminergic Cell Death. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2021, 41, 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.; Sha, S.; Zhou, L.; Wang, C.; Yin, J.; Chen, L. Sigma-1 receptor deficiency reduces MPTP-induced parkinsonism and death of dopaminergic neurons. Cell Death Dis 2015, 6, e1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).