Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

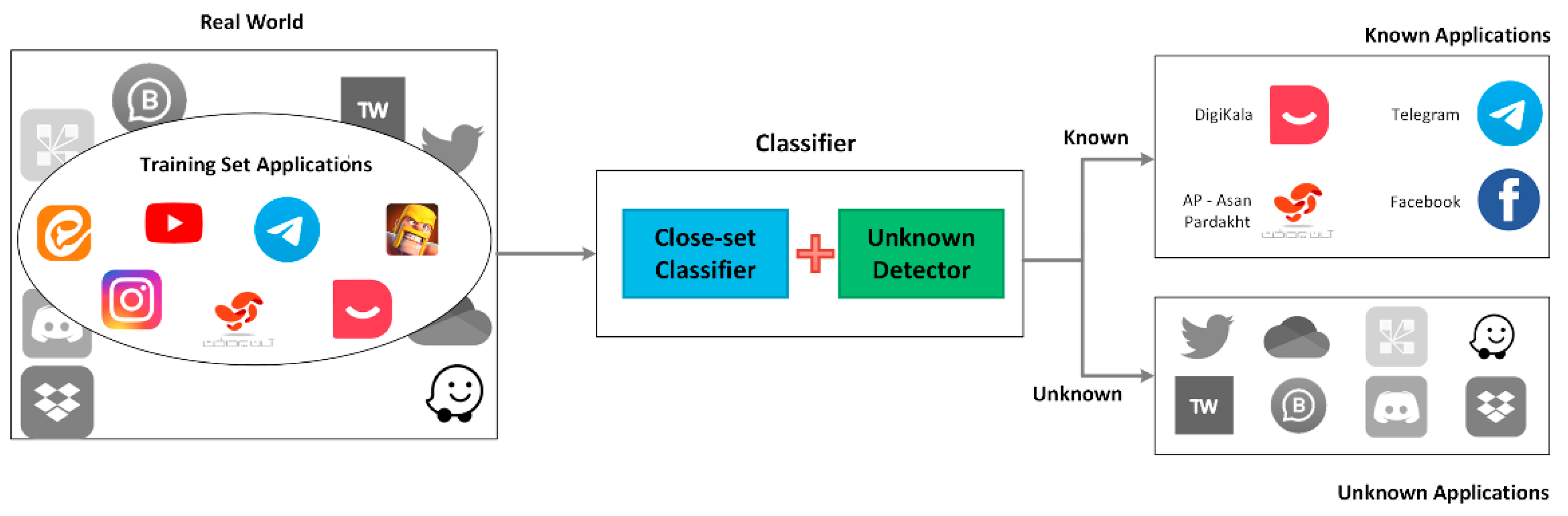

14 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset

3.2. Experimental Setup

3.2.1. Invariant Network Environment

3.2.2. Variant Network Environment

3.3. Model Architecture

3.3.1. Closed-Set Classifier

3.3.2. Unknown Detector

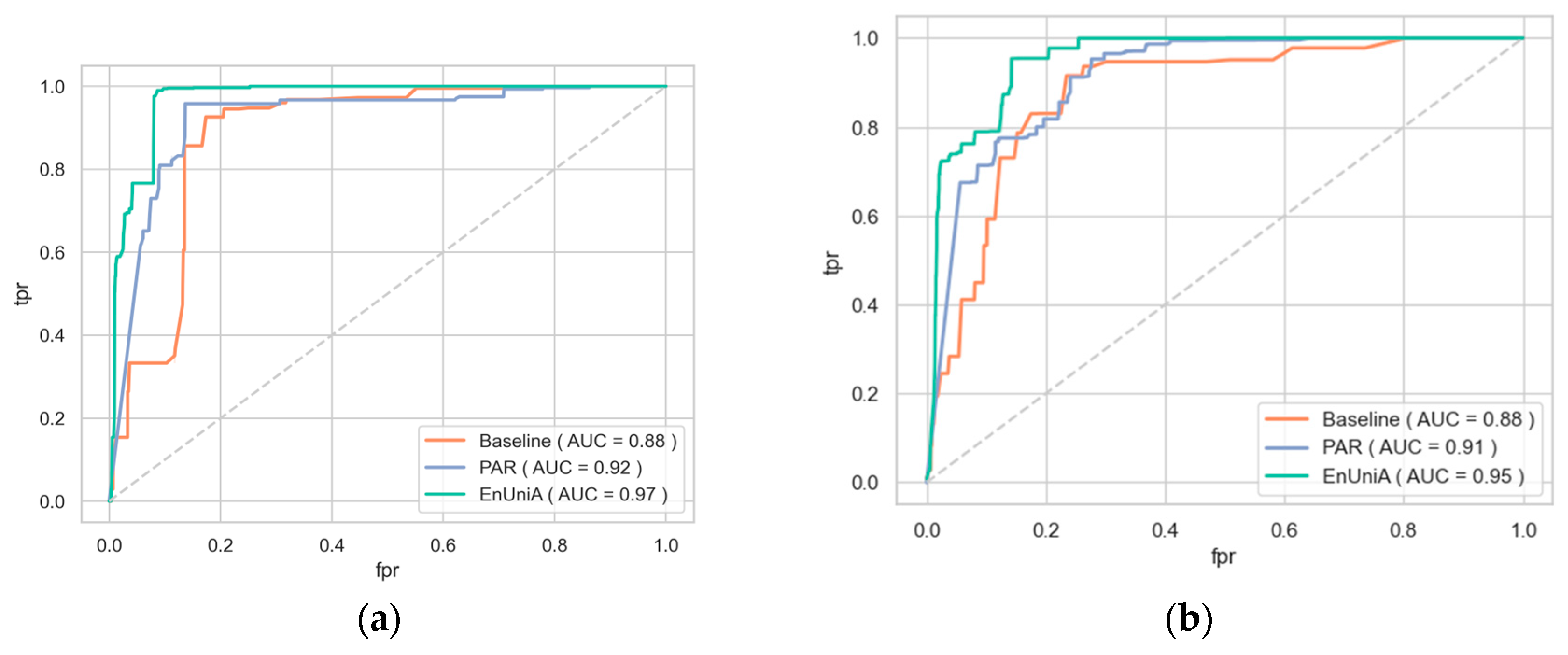

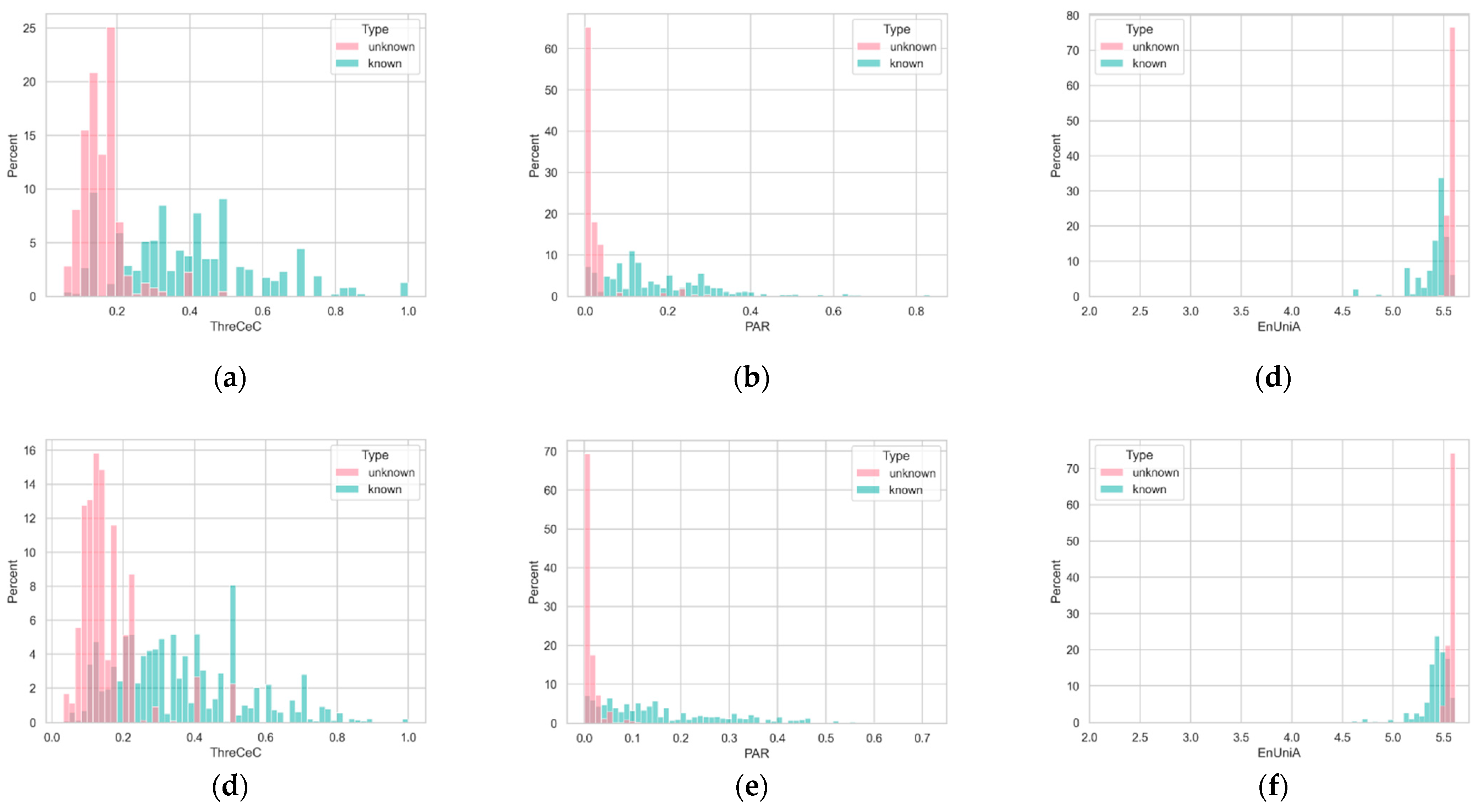

- Probability Anomaly Recognition (PAR): The PAR method, inspired by the Best versus Second Best (BvSB) approach in active learning, utilizes the disparity between the highest and second-highest classification probabilities to make decisions. When the disparity is small, it indicates uncertainty in the model’s prediction, with the highest probability being only slightly greater than the second-highest. This reduced disparity suggests that the sample is more likely to be unknown, as the model struggles to confidently distinguish between classes. The operation function of this detector is shown in equation (1) that ŷ1 and ŷ2 represent the classes with the highest and second highest estimated probabilities according to the θ model.

- Entropy-Based Uniformity Analysis (EnUniA): The EnUniA method, inspired by entropy-based techniques in active learning, calculates the classification probabilities for all classes. Higher entropy values indicate a uniform distribution over the classes, suggesting that the model is uncertain about the correct classification. This uniformity in probability distribution is a strong indicator of the likelihood that the sample is unknown. Entropy values range from zero (indicating a clear, confident classification) to the logarithm of the number of classes (indicating maximum uncertainty). The operation function of this detector is shown in equation (2).

3.4. Optimal Threshold Determination

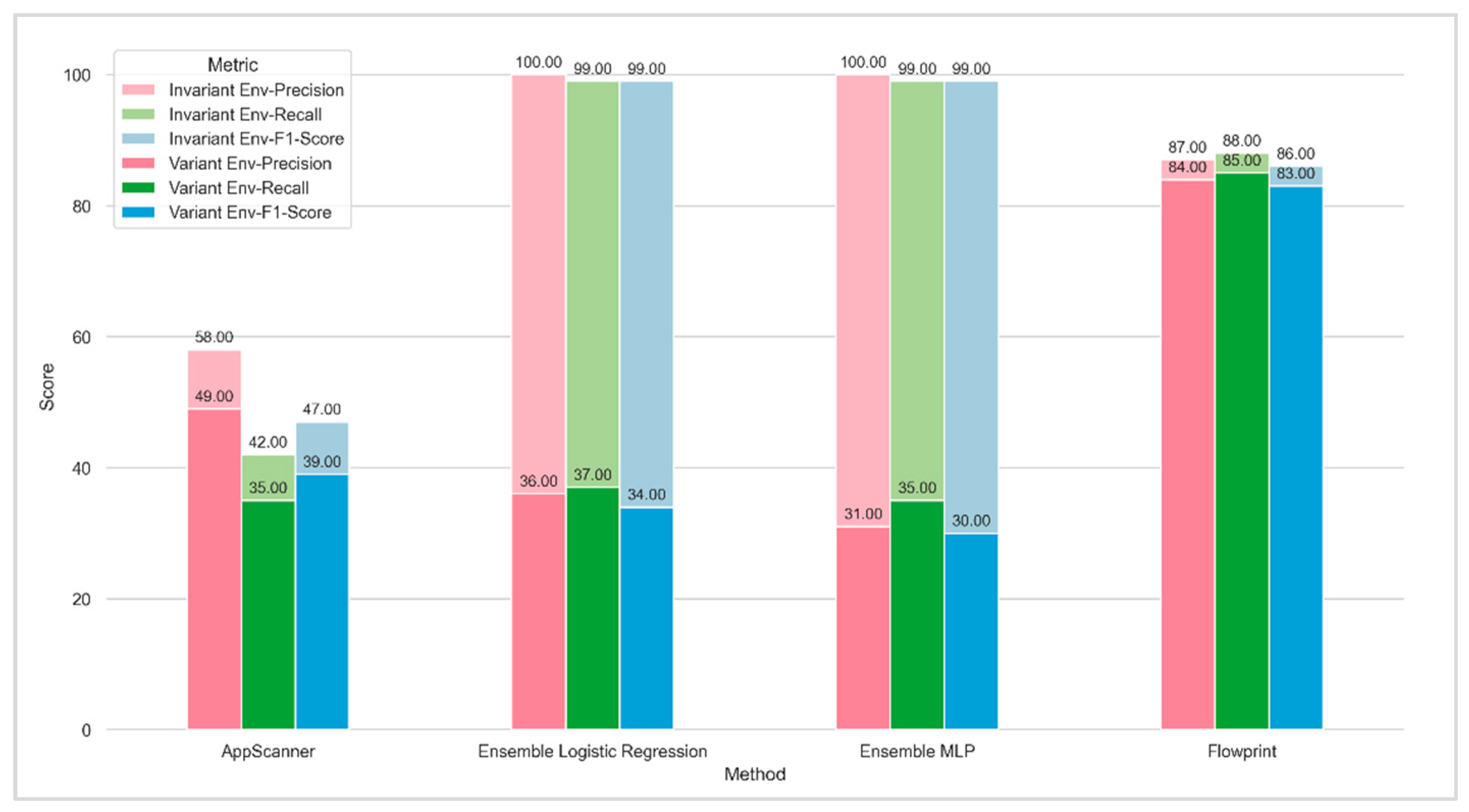

4. Simulation Results

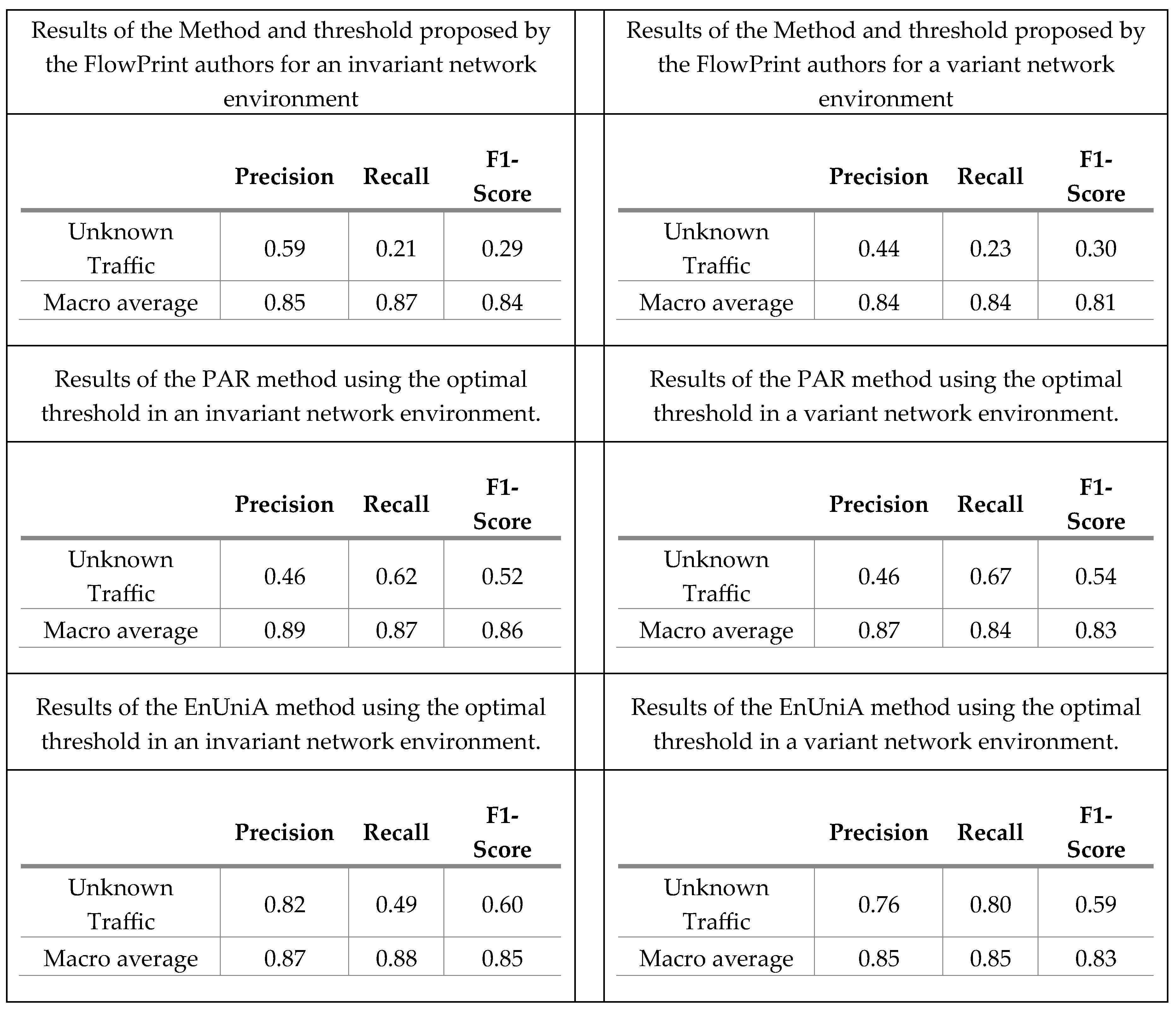

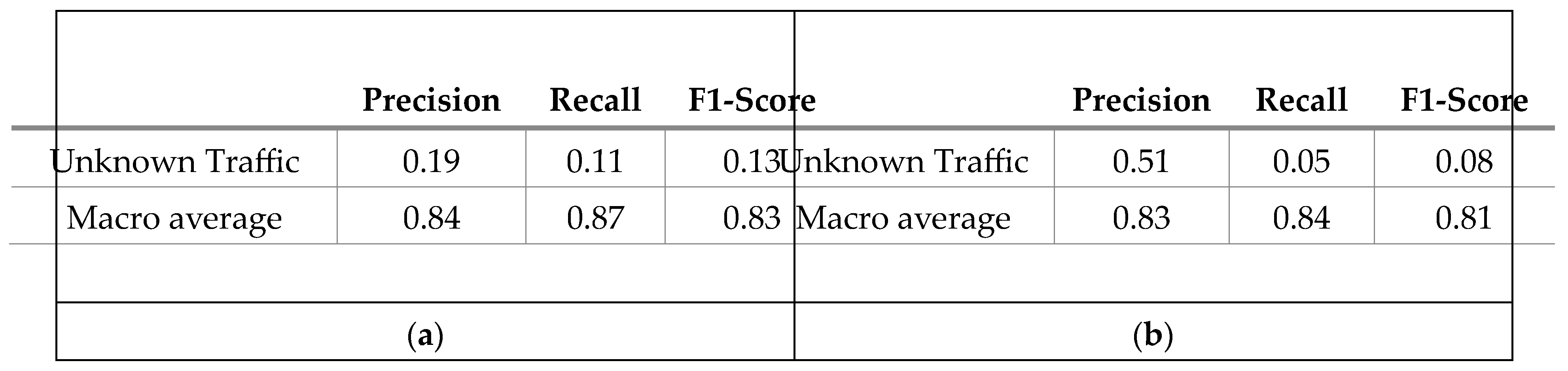

4.1. Expriment of Appearing New Applications (Unknown Classs)

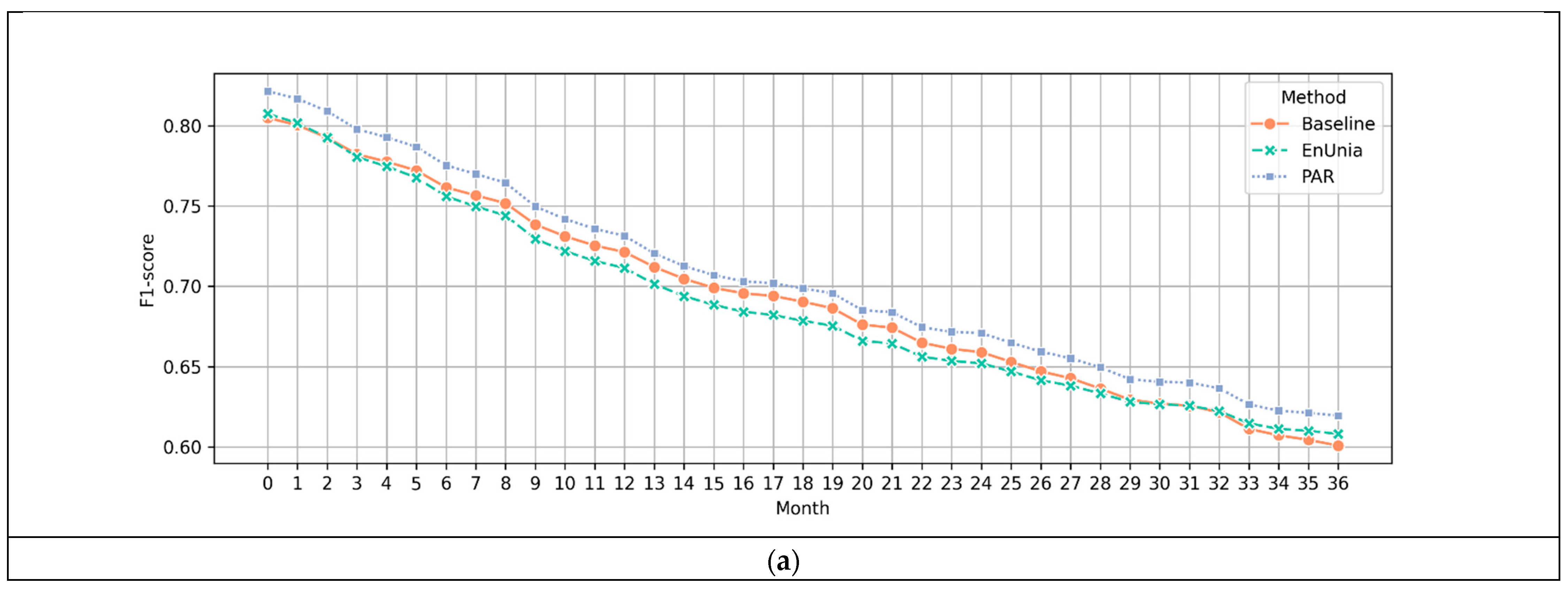

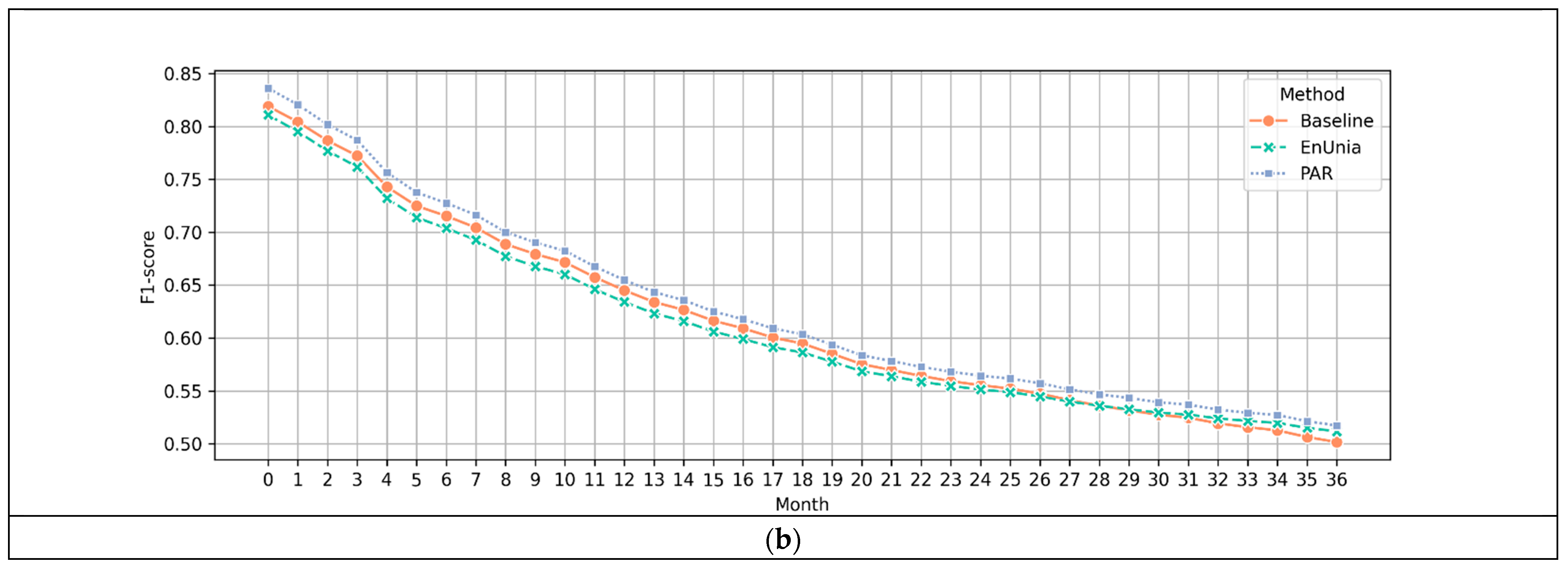

4.2. Simulation of Long-Term Performance

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ETI | Encrypted Traffic Intelligence |

| NTC | Network Traffic Classification |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| OSR | Open-set Recognition |

| OOD | Out-of-Distribution |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| MSP | Maximum SoftMax Probability |

| PAR | Proximity Ambiguity Resolver |

| EnUnia | Entropy-based Uncertainty Analyzer |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| BoF | Bag of Flow |

References

- Pathmaperuma, M.H.; Rahulamathavan, Y.; Dogan, S.; Kondoz, A.M. Deep Learning for Encrypted Traffic Classification and Unknown Data Detection. Sensors 2022, 22, 7643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, M.; Ye, K.; Liu, X.; Zhu, L.; Kang, J.; Yu, S.; Li, Q.; Xu, K. Machine Learning-Powered Encrypted Network Traffic Analysis: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2022, 25, 791–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Yan, T.; Qi, F.; Chen, G. Unknown Traffic Recognition Based on Multi-Feature Fusion and Incremental Learning. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azab, A.; Khasawneh, M.; Alrabaee, S.; Choo, K.-K.R.; Sarsour, M. Network traffic classification: Techniques, datasets, and challenges. Digit. Commun. Networks 2024, 10, 676–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. van Ede et al., “FlowPrint: Semi-supervised mobile-app fingerprinting on encrypted network traffic,” in Network and Distributed System Security Symposium (NDSS), 2020, vol. 27.

- Lotfollahi, M.; Siavoshani, M.J.; Zade, R.S.H.; Saberian, M. Deep packet: a novel approach for encrypted traffic classification using deep learning. Soft Comput. 2019, 24, 1999–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Li, J.; Mirkovic, J.; Wu, C.; Wang, C.; Ren, H.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y. Unmasking the Internet: A Survey of Fine-Grained Network Traffic Analysis. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2025, PP, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, M.S.; Peng, Y. Procedures, Criteria, and Machine Learning Techniques for Network Traffic Classification: A Survey. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 61135–61158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Bao, H.; Wang, Q.; Li, Z. Robust network traffic identification with graph matching. Comput. Networks 2022, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Bao, H.; Shi, H.; Wang, Q. ProGraph: Robust Network Traffic Identification With Graph Propagation. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2022, 31, 1385–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekghaini, N.; Akbari, E.; Salahuddin, M.A.; Limam, N.; Boutaba, R.; Mathieu, B.; Moteau, S.; Tuffin, S. Deep learning for encrypted traffic classification in the face of data drift: An empirical study. Comput. Networks 2023, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhou, K.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z. Generalized Out-of-Distribution Detection: A Survey. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2024, 132, 5635–5662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, F.; Ye, F.; Wu, H. Autonomous Unknown-Application Filtering and Labeling for DL-based Traffic Classifier Update. IEEE INFOCOM 2020 - IEEE Conference on Computer Communications. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, CanadaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 397–405.

- Mobile internet traffic as percentage of total web traffic in 25, by region.” statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/306528/share-of-mobile-internet-traffic-in-global-regions/ (accessed 25 March, 2025). 20 January.

- Zhang, C.; Patras, P.; Haddadi, H. Deep Learning in Mobile and Wireless Networking: A Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2019, 21, 2224–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, V.F.; Spolaor, R.; Conti, M.; Martinovic, I. Robust Smartphone App Identification via Encrypted Network Traffic Analysis. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2017, 13, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacki, A. Identification of adaptive video streams based on traffic correlation. Multimedia Tools Appl. 2019, 78, 18271–18291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Moore and D. Zuev, “Internet traffic classification using bayesian analysis techniques,” in Proceedings of the 2005 ACM SIGMETRICS international conference on Measurement and modeling of computer systems, 2005, pp. 50-60.

- Madhukar, A.; Williamson, C. A Longitudinal Study of P2P Traffic Classification. 14th IEEE International Symposium on Modeling, Analysis, and Simulation. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE;

- Taylor, V.F.; Spolaor, R.; Conti, M.; Martinovic, I. AppScanner: Automatic Fingerprinting of Smartphone Apps from Encrypted Network Traffic. 2016 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 439–454.

- Aouedi, O.; Piamrat, K.; Parrein, B. Ensemble-Based Deep Learning Model for Network Traffic Classification. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2022, 19, 4124–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, H.; Temelli, R.; Gurbuz, O.; Koksal, O.K.; Ipekoren, A.K.; Canbal, F.; Karahan, B.D.; Kuran, M.Ş. Multimedia traffic classification with mixture of Markov components. Ad Hoc Networks 2021, 121, 102608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Wei, M.; Zhu, L.; Wang, M. Classification of Encrypted Traffic With Second-Order Markov Chains and Application Attribute Bigrams. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2017, 12, 1830–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’angelo, G.; Palmieri, F. Network traffic classification using deep convolutional recurrent autoencoder neural networks for spatial–temporal features extraction. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2021, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Gu, H.; Wei, W. Tree-RNN: Tree structural recurrent neural network for network traffic classification. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Shen, J.; Du, X. A Method of Few-Shot Network Intrusion Detection Based on Meta-Learning Framework. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2020, 15, 3540–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Cruz, C. Coleman, E. M. Rudd, and T. E. Boult, “Open set intrusion recognition for fine-grained attack categorization,” in 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Technologies for Homeland Security (HST), 2017: IEEE, pp. 1-6.

- Zhang, Y.; Niu, J.; Guo, D.; Teng, Y.; Bao, X. Unknown Network Attack Detection Based on Open Set Recognition. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 174, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, M.; Garshasbi, J.; Mehdizadeh, M.; Nozari, N.; Khesal, A.R.; Dokhaei, M.; Teimouri, M. ITC-Net-blend-60: a comprehensive dataset for robust network traffic classification in diverse environments. BMC Res. Notes 2024, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Vaze, K. Han, A. Vedaldi, and A. Zisserman, “Open-Set Recognition: a Good Closed-Set Classifier is All You Need?,” in International Conference on Learning Representations, 2022.

- B. Settles, “Active learning literature survey,” 2009.

- Du, L.; Gu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Gao, C. Open World Intrusion Detection: An Open Set Recognition Method for CAN Bus in Intelligent Connected Vehicles. IEEE Netw. 2024, 38, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scenario ID | No. Apps | No. Bi-Flows1 | User | Device | Location2 | ISP3 | ||

| Vendor | Model | Android version | ||||||

| A | 59 | 108,370 | U1 | Xiaomi | Note10 Pro | 11 | L1, L2 | N1, N2 |

| B | 60 | 72,279 | U2 | Samsung | A50 | 11 | L1, L3 | N1, N3 |

| C | 59 | 141,957 | U3 | Samsung | A31 | 11 | L4 | N2, N4 |

| Tab A7 Lite | 11 | L4 | N2, N4 | |||||

| D | 59 | 106,652 | U4 | Samsung | J7 Prime 2 | 9 | L1, L2, L5 | N1, N2, N5 |

| E | 52 | 47,044 | U5 | Samsung | J7 | 6.0.1 | L6 | N2, N6 |

| A12 | 11 | L6 | N2, N6 | |||||

| Method | Condition | Optimal value | F1-score (%) |

| MSP | Invariant Environment | 0.089 | 81.41 |

| Variant Environment | 0.143 | 91.54 | |

| PAR | Invariant Environment | 0.005 | 82.25 |

| Variant Environment | 0.001 | 92.53 | |

| EnUniA | Invariant Environment | 5.601 | 81.37 |

| Variant Environment | 5.580 | 91.51 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).