1. Introduction

Across the UK an estimated 944,000 individuals are living with dementia (Alzheimer’s Research UK, 2023) with a further 55 million people affected worldwide (World Health Organisation, 2023). Whilst dementia has many different causes, all forms of dementia are characterised by a progressive loss of cognitive functioning which interferes with a person's daily life and activities. Consequently, people living with dementia experience a range of difficulties from the initial onset, when any cognitive decline may be barely noticeable, to the most severe stage, when the person comes to depend almost completely on others. While there are several pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments for dementia, none of the causes of dementia can, as yet, be cured.

Dementia, then, represents an existential threat to a person’s identity, creating profound challenges to those who are affected (Cheston and Christopher, 2019). One such challenge is that of adjusting to the psychological and social changes inherent within dementia (Brooker, Dröes, and Evans, 2017). Post-diagnostic social and emotional support can play an important role in supporting adjustment by validating experiences, promoting coping strategies, and helping people living with dementia to develop their understanding of the condition and how it impacts on them (Bamford et al., 2021)

Young onset dementia

The term ‘young onset dementia’ refers to those people who are aged under 65 when they receive a dementia diagnosis (Carter, Jackson, Gleisner and Verne, 2022). When compared to the impact of dementia in older age, young onset dementia causes a range of unique social and psychological challenges (Greenwood and Smith, 2016). An estimated 70,800 individuals are living with young onset dementia in the UK (Alzheimer’s Research UK, 2023). Younger adults are more likely to have a rarer form of dementia, such as frontotemporal dementia, to report significantly higher psychological and physical distress and to have caring responsibilities themselves (Young Dementia Network, 2025). Furthermore, the loss of meaningful activity, such as employment, is associated with diminished self-worth and disempowerment – all of which can lead to people with young onset dementia being reluctant to disclose their diagnosis and to avoid social contact (Greenwood and Smiht, 2016). Many younger people report intense fears about the future and even, at times, suicidal thoughts following the dementia diagnosis (Busted, Nielsen and Birkelund (2020).

While services that focus specifically on the needs of younger people living with dementia are beginning to emerge, these are still relatively limited. Consequently, the unique needs of younger adults living with dementia often continue to be over-looked (Rabanal, Chatwin, Walker, O’Sullivan and Williamson, 2018). While younger people living with dementia may well benefit from some of the opportunities for support aimed at older people such as cognitive behavioural therapy for depression and anxiety (El Baou et al., 2024) and dementia cafés (Greenwood, Smith, Akhtar and Richardson, 2017; De Luca et al., 2021), there is a clear demand for post-diagnostic support that has been specifically tailored for this population (Millenaar et al., 2016).

The LivDem post-diagnostic course

The Living Well with Dementia (LivDem) course is a psychologically informed group intervention run by trained facilitators that is aimed at supporting people living with dementia to adjust to, accept and come to terms with a dementia diagnosis. While LivDem is primarily a psychoeducational intervention it incorporates some elements from a psychotherapeutic framework and is designed to be delivered by non-psychologists (Cheston, Dodd and Woodstoke, 2023). It is an eight-week programme intended for around six-to-eight group members all of whom will have received a diagnosis of dementia.

LivDem takes a deliberately slow pace to discussing dementia with the initial sessions focusing on the symptoms experienced by group participants (e.g., short-term memory loss) but without explicitly associating this with a specific diagnosis. As the course progresses the group is encouraged to discuss their emotional responses to these cognitive changes, including how they cope with feelings such as embarrassment, anxiety and depression. Only in weeks five and six do facilitators directly address issues around diagnosis and prognosis, for instance by asking participants who they have told about the diagnosis. The final weeks address practical issues around living well. This design means that group participants are not forced to directly address the label of dementia in the first sessions when this might be too threatening and uncomfortable for them. Instead, this is left until later sessions when they have had a chance to build a relationship with other participants and the group itself has formed (Cheston and Marshall, 2019; Cheston, 2021). The group format enables people who have been diagnosed to realise that they are not alone and allows them to learn from others going through similar experiences (Cheston and Dodd, 2020).

Adapting LivDem for Younger Adults

As the LivDem workbook for facilitators (Cheston and Marshall, 2019) was designed to support groups for older people living with dementia it offers relatively little guidance about how the needs of younger people can be meaningfully addressed. Yet, younger adults living with dementia and their families often look for opportunities to develop their awareness of their condition, to have emotional support (Dementia UK, 2025), and greater contact with others who share their diagnosis (Greenwood and Smith, 2016), in order to adjust to the diagnosis and the associated changes (Chirico et al., 2022). While it might be possible for LivDem to meet these needs, post-diagnostic support needs to be age-appropriate if it is to provide positive experiences (Greenwood and Smith, 2016). This research therefore aims to how the current LivDem model could be adapted to address the unique challenges that younger adults living with dementia experience.

Research Questions

This study aimed to explore LivDem facilitator perspectives on adapting LivDem for younger adults, investigating two questions:

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

The LivDem 2024 online survey gathered both quantitative and qualitative data via a semi-structured, anonymous questionnaire that was open between 7th December 2023 and 12th March 2024. Target participants worked within healthcare settings in the UK and abroad, in both statutory and voluntary sectors. We specifically recruited LivDem facilitators as participants as they both had practical experience of delivering LivDem courses and were also likely to have experience of delivering this and other services to younger people living with dementia. This research was approved by the University of the West of England Psychology Ethics Committee on 20th November 2023 (ref: LB2023006).

2.2. Participants

Around two hundred LivDem facilitators, previously trained by the LivDem team at the University of the West of England, were approached to take part through advertisement in a newsletter and advertising on social media. Thirty-two respondents completed all or part of the survey and after participants who had not progressed past the demographic questions were removed, fifteen participants were included in the analysis (). The mean age of participants was 39.13 (SD=12.86) with fourteen out of the fifteen participants (93%) being women and thirteen identifying as white British (87%). All the names of participants have been altered.

Table 1.

Description of participant characteristics.

Table 1.

Description of participant characteristics.

| Pseudonym |

Age |

Gender |

Ethnicity |

Country of practice |

Job role |

Number of LivDem courses delivered or supervised |

| Antony |

55 |

Male |

White British |

UK |

Support Worker |

8 |

| Beth |

29 |

Female |

White |

UK |

Psychologist |

1 |

| Charlotte |

26 |

Female |

White British |

UK |

Assistant psychologist |

0 |

| Debbie |

23 |

Female |

White British |

UK |

Assistant psychologist |

0 |

| Eva |

59 |

Female |

White British |

UK |

Clinical psychologist |

5 |

| Fiona |

25 |

Female |

White British |

UK |

Assistant psychologist |

1 |

| Georgia |

23 |

Female |

White British |

UK |

Assistant psychologist |

3 |

| Heather |

26 |

Female |

British |

UK |

Assistant psychologist |

4 |

| Isabel |

42 |

Female |

White British |

UK |

Support worker |

2 |

| Jane |

49 |

Female |

White British |

UK |

Occupational therapist |

6 |

| Kiera |

36 |

Female |

White British |

UK |

Therapist |

4 |

| Layla |

46 |

Female |

White British |

UK |

Mental health nurse |

0 |

| Mary |

53 |

Female |

White British |

UK |

Therapist |

9 |

| Natalie |

49 |

Female |

White British |

UK |

Occupational therapist |

0 |

| Ophelia |

46 |

Female |

White British |

UK |

Occupational therapist |

4 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.3. Procedure

Following the completion of the survey, participants received a debrief that included information on the research aims and how they could withdraw their data, as well as the contact information of the researchers. The raw data were exported to an excel spreadsheet.

2.4. Analysis

Descriptive analysis of demographic and statistical data was carried out using JAMOVI 2.3. Qualitative responses were analysed using Reflexive Thematic Analysis which as Braun and Clarke (2019) have highlighted is flexible in the material it can be used to analyse, including data from online surveys. This analysis followed Braun and Clarke’s (2019) six-phase guide, and while analysis is described in chronological order, processes were dynamic and non-linear (Williams and Moser, 2019). During phase 1 (familiarisation), the data were read and re-read noting initial comprehensions within a reflexive journal. After preliminary immersion into the data, phase 2 (generating initial codes), was conducted using open coding, in which any interesting data was identified line-by-line, to represent meaning as communicated by participants (Braun and Clarke, 2013). In phase three (generating themes), codes were written onto post it notes, arranged by similarity, and copied into a table, moving analysis from semantic description to interpretation, by exploring broader meanings (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Central organizing concepts (Braun and Clarke, 2013) were produced to capture these clusters of codes and underpin initial themes produced. During phase 4 (reviewing themes), a preliminary thematic map (Javadi and Zarea, 2016) was used to organise how themes overlapped and interacted with one another, resulting in some themes being combined, removed, or split. Revised themes and thematic map were applied to codes and extracts to ensure they reflected the entire data set (Campbell et al., 2021) and to facilitate the transition to phase 5 (defining and naming themes) which attempted to capture the essence of findings. During phase 6 (producing the report), extracts from coded data were used to illustrate aspects of themes, and explore their meanings, using previous literature to further develop findings (Campbell et al., 2021).

2.5. Reflexive Statement

All of the authors have a background in psychology: GW has an undergraduate degree in psychology and co-created the survey as part of that degree where she was supervised by RC; NW and RC are both clinical psychologists; and ED is a researcher with a psychology and public health background. Along with Ann Marshall, RC is the co-author of the LivDem manual for groups whilst ED has worked on developing the LivDem approach for a number of years. NW has joined the LivDem team more recently. As an analytical team we attempted to be mindful of the balance between RC and ED’s commitment to the LivDem approach with a position of open enquiry as to whether the model needed to be adapted for those with younger onset dementia, and if so, what such an adaptation might look like. Collectively, we have been influenced by the social model of disability (Oliver, 2013) that is that we are “not disabled by our impairments but by barriers we face in society” (Oliver, 2013, p 1).

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results

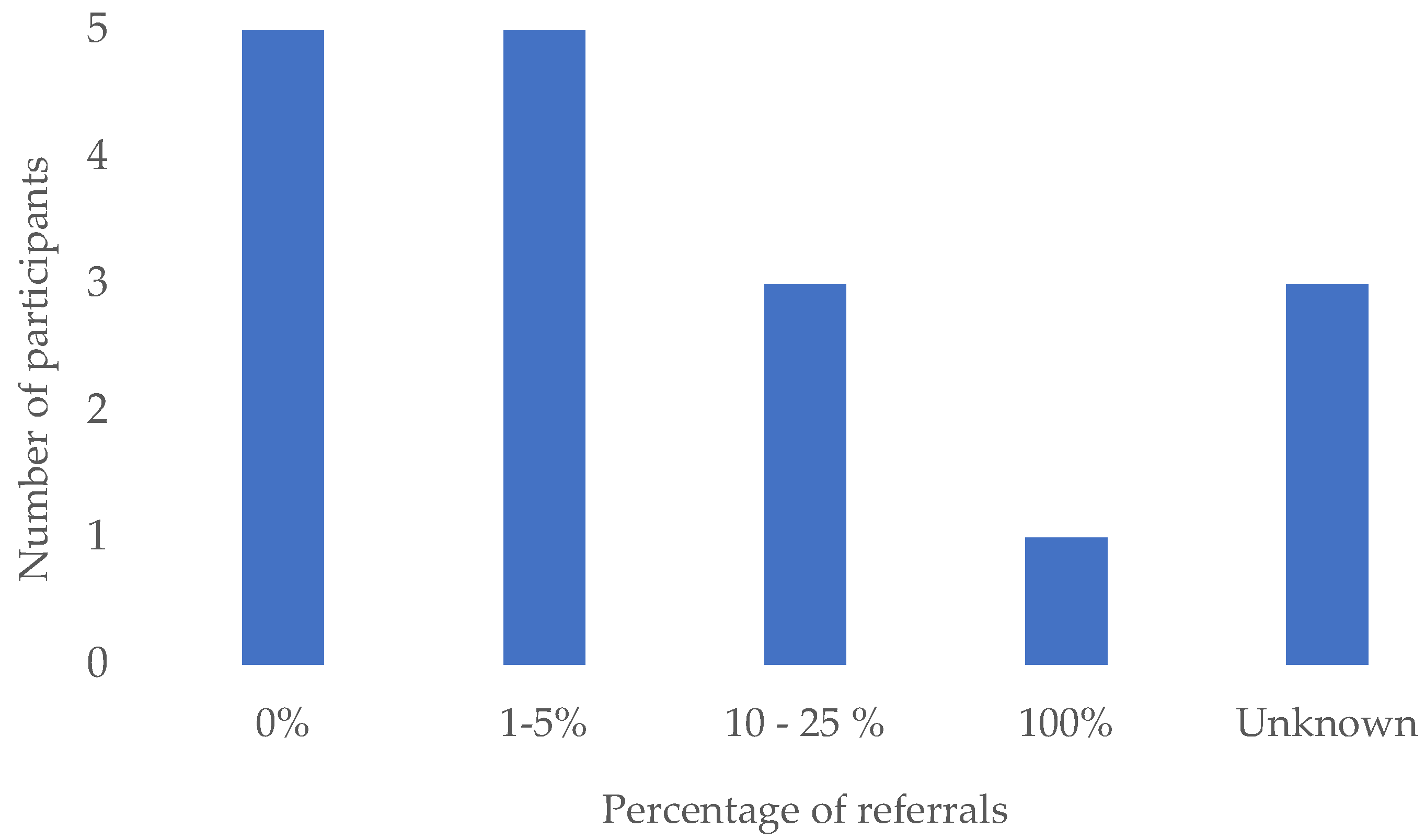

A forced-response 5-point Likert scale (Likert, 1932) indicated that almost all participants were either somewhat likely (44%) or extremely likely (44%) to recommend the LivDem course to younger adults living with dementia. None of the respondents reported that they would be unlikely to recommend it to younger adults. However, the proportion of referrals for people with young onset dementia to the services in which respondents worked was low (see

Figure 1). Indeed, ten of the fourteen participants reported receiving either no referrals for younger people or less than 5% of the total number. One respondent worked for a “specific service for younger people (under 65s)” and thus reported that 100% of their referrals were for younger adults.

We were aware that there can be challenges in delivering face-to-face services in areas where there are relatively few people with younger onset dementia and where it may be practically difficult to attend a group, for example in rural areas. Therefore, we asked respondents about online delivery of the course as a potentially more practical option for meeting the needs of younger adults. Facilitators were split on this, with 7 of 14 (50%) of respondents reporting that a hybrid model could be used and 6 (43%) stating that only in-person sessions should be offered.

3.2. Reflexive Thematic Analysis

Reflexive Thematic Analysis of survey responses generated two main themes (see

Table 2) associated with adapting the LivDem post-diagnostic course for younger adults living with dementia. Theme one: ‘

The domino effect’: Unique Challenges for Younger Adults details some of the ways dementia impacts daily life for those with an early onset of the condition. Theme two: ‘

Good to be with peers’: The Importance of Age-Appropriate Support offers insights into what content should be included within the LivDem course to tailor it to the experiences of younger adults.

3.2.1. Theme 1: “The domino effect”: Unique Challenges for Younger Adults

Theme one explores younger adults’ concerns relating to employment, driving, familial responsibilities, and relationships. Together, the two subthemes of “Life and Opportunities Stripped Away” and “Impacting on Everyone” suggest that facilitators are highly aware that the timing of a young onset diagnosis can heighten the sense of loss across many aspects of daily life.

3.2.1.1. Subtheme: ‘Life and opportunities stripped away’

Ten participants emphasised the multiple challenges and losses many younger adults face when they are diagnosed. For facilitators, the intensity of these losses appeared to be related to the relative stage of the life cycle that younger adults were at compared to older adults. For example, potential participants are still likely to be working and so a diagnosis of dementia may have financial and practical implications:

“Particularly concerned about employment and financial worries if they can no longer work (or drive) following diagnosis.” Antony

“Acknowledging the trauma of losing your job/fear of losing your job.” Natalie

Natalie’s use of the term trauma suggested that loss of employment evokes negative emotions and additional stressors that may impact ability to cope with a dementia diagnosis. Natalie went further in suggesting financial worries were not the only implications of losing one’s job, with identity and self-esteem also affected:

“Lack of role and sense of purpose (in addition to reduced finances) if they have to stop work.” Natalie

A lack of role and sense of purpose indicates employment is a large source of identity and structure for younger adults. As with working, participants described loss of driving as deeper than financial worry, specifically noting the impact on independence:

“Driving is also a key issue - where individuals may already [have] been advised to stop driving, which obviously impacts significantly on independence and access to occupations.” Ophelia

Participants proposed that the accumulation of these losses for younger adults is particularly intense due to the unexpected timing of diagnosis:

“A loss of self can often be more problematic for this age group as they are still in the thick of developing their various roles & positions societally. There’s often more anger & frustration at having life & opportunities stripped away.” Kiera

“Having this diagnosis in the "prime" of your life...” Natalie

“Shock at the diagnosis as it is ‘too early’ for this problem, it is something that happens to much older people." Antony

These three powerful extracts suggest that younger adults do not expect the diagnosis and are more shocked and intensely impacted by the associated losses.

3.2.1.2. Subtheme: ‘Impacting on everyone’: Changes in roles and relationships

Ten respondents spoke about their concerns that a dementia diagnosis extended beyond the self and the impact that this could have on the family unit as roles and relationships shifted:

“The decision about whether or not to tell the people around them carries even more significance, because of the additional impact it has on others … the knock-on effects on loved ones can be carried with guilt & shame.” Kiera

“Impact of changes of role within the family unit, having child, grandchild and/or elderly parent responsibilities. The domino effect of one element impacting on everyone (emotionally, practically and financially).” Natalie

Whilst Natalie highlights the multiple people to whom the individual may have responsibilities and thus the wide-ranging impact of a dementia diagnosis, Kiera refers to the guilt and shame that can be felt by individuals who observe the effects of the dementia on their loved ones. The use of the word “carried” in relation to these emotions conveys a weight to this experience and she observes these emotions may impact on whether people share their diagnosis even with those to whom they are closest.

Some participants specifically mentioned the concerns of those with young onset dementia about the impact on their children and grandchildren:

“Concerns about not being able to support their children or to get to know their grandchildren.” Debbie

“Uneasy that their adult children may be thrust into the role of caring for them so soon compared to someone diagnosed in their late 70s or 80s.” Antony

Some facilitators, then, were aware that as the families of many people with young onset dementia would be relatively young, so potential participants in a LivDem group would have to navigate how their relationship with their children might need to change. This highlights a clear difference between the challenges that younger and older adults with dementia face when adjusting to a dementia diagnosis. Thus, Antony’s use of ‘uneasy’ indicates an element of guilt that could be felt by younger adults, relating to the impact of their dementia on young children. Antony also noted that sexual intimacy and relationship with partner may be a more dominant concern for younger adults living with dementia:

“Particular dynamics which may be more prevalent in younger people's minds might include the effect on possible sexual intimacy and their relationship with partner/spouse.” Antony

While changes in their levels and patterns of sexual intimacy may impact on people living with dementia at all ages, it may be that this is of especial concern for younger adults. This has a number of implications for the current model of LivDem. For instance, facilitators may need to develop ways to enable group participants to discuss these sensitive issues together. Additionally, families may need to be further integrated into the model to give the opportunity for these relationship challenges to be explored and addressed (Woodstoke, Winter, Dodd and Cheston, 2024).

3.2.1. Theme Two: ‘Good to be with peers’: The Importance of Age-Appropriate Support

For many younger people attending a LivDem course typically involves being part of a group of perhaps six to eight other people, most or all of whom are considerably older than they are. The second theme concerned how this difference in ages of post-diagnostic support groups such as LivDem could impact on the success and appropriateness of sessions. There was a strong sense in participant’s accounts that bringing together people of a similar age was important and that this could potentially be achieved through online groups. Theme two is embodied by two subthemes: Groups ‘Full of Old People’ and Groups ‘Specifically for Younger People’.

3.2.1.1. Subtheme: Groups ‘Full of Old People’

This subtheme was present in the accounts of eight participants and captured the difficulties that can arise when a younger adult living with dementia joins a predominantly older support group, including concerns that their needs may not be addressed:

“For most part those with YOD have not gained a lot from joining a group of older adults. They tend to assign themselves as 'carers to the elderly participants' rather than being able to focus on their own struggles.” Eva

“Not age appropriate. Very much in the minority. Needs were over-shadowed by the majority attending (older people).” Natalie

Eva and Natalie both expressed their concern that as younger members are often in the minority within a group, their experiences are typically not at the forefront of group discussions. If younger adults were not able to ‘focus on their own struggles’ (Eva) or experienced their needs being ‘overshadowed’ (Natalie), then this would limit their opportunities to use the course to address the challenges they face in living with dementia. Furthermore, if younger individuals perceived that the group was for older people they might feel out of place, perhaps limiting the connections they could make with other group members.

Other participants expanded on the way in which younger people with dementia were at risk of feeling out of place within predominantly older groups and highlighted instances of isolation and fear. Thus, Layla described the groups being "full of old people" and how younger attendees "found it frightening (seeing people in more advanced stages of dementia)”. Ophelia identified similar issues:

“…some people report feeling alienated if other group members are much older than them or content is not suited to their age experiences.” Ophelia

The phrase “full of old people” (Layla) suggests younger attendees may feel excluded from and different to the rest of the group and thus experience a sense of “alienation” (Ophelia). This sense of alienation is likely to negatively affect both their experience of the group and their adjustment to the diagnosis, which LivDem aims to support.

3.2.1.2. Subtheme: Groups ‘specifically for younger people’

Subtheme two, present in the account of 14 participants, captures the potential benefits of bringing similar-aged people with dementia together:

“Good to be with peers / people their own age or of a similar age. Shared experience.” Natalie

“If there were enough people living with young onset dementia referred then I think it would be of great benefit to run a course specifically for this client group. Peer support is always the most beneficial outcome of the course cited by attendees.” Jane

“One specifically for younger people and their families. They feed back the value of meeting with others who are in a similar situation (for family members too) and also learning about information and resources that can help.” Ophelia

Jane and Ophelia suggest that for younger people being with others of a similar age could be beneficial as it would enable individuals in similar situations to share experiences and knowledge. Some participants felt that offering similar-aged groups was particularly important as younger adults may otherwise not have the opportunity to meet peers of their own age and could become isolated:

“It might be harder for people with younger onset dementia to adjust to their diagnosis because it might be more unexpected, and they could feel more isolated/disconnected from those around them due to their age and seeing that others of a similar age are not experiencing the same types of problems that they are.” Debbie

Debbie indicated that individuals with young onset dementia can become isolated from their peers, as those of a similar age rarely experience the same problems. Participants emphasised the desire to ensure similar-aged groups, but feel constrained by the fact that relatively few younger adults are referred to their services (see Figure 2):

“Although we do not have enough referrals for people with young onset dementia, we do try to stream referrals so that there will be at least one other person in the group who is a similar age (i.e. under 65).” Antony

This indicates that the relative scarcity of people with young onset dementia within services may impede the ability of facilitators to establish a LivDem group solely for younger people. One option to address this issue would be to offer LivDem online, which would enable it to be offered over a larger geographical area so the low referral rates would be less of an issue. This flexibility might also offer benefits for those participants who are still working:

“Younger people may still be in work and so do not have the time to attend sessions…hence why having the online sessions would be a useful option too. It also means you could reach people regardless of distance. Younger people are usually better gripped with technology to attend online sessions compared to older adults.” Charlotte

While Charlotte described the benefits of offering online courses, other participants highlighted the challenges inherent in delivering LivDem online – for instance online sessions may make it much harder to meet the emotional needs of course members:

“In person groups are more appropriate when trying to build trust & open up potentially weighty conversations. It’s easier to focus when you’re not online. You can comfort someone properly f2f if they become upset or overwhelmed.” Kiera

For Kiera supportive relationships were better fostered in-person than online. One potential solution that was suggested was for a mix of in-person and online sessions that permits more flexibility whilst still ensuring a comfortable environment for individuals to express difficult emotions:

“People prefer different ways so offering both may help with engagement. Sometimes having an online option is more convenient and easier to attend. Sometime people prefer the face-to-face interaction, and it is easier to interact and build relationships.” Fiona

4. Discussion

This mixed-methods study had two aims: to investigate the perspectives of LivDem facilitators on the challenges faced by younger adults living with dementia; and to understand how the LivDem course might be adapted to respond to some of these challenges. Importantly the quantitative findings show that facilitators would recommend LivDem to younger adults, thus supporting the idea of adapting the course.

Theme one, ‘The domino effect’: Unique Challenges for Younger Adults, described a range of ways in which a diagnosis can impact younger people and how this might be taken into consideration when adapting LivDem. Participants indicated that the time of diagnosis causes compounded stress due to being at working age and having more caring responsibilities. Previous research has similarly found that dementia related losses and changes occur at a time of high financial, familial, and occupational responsibilities (Cations, 2023), intensifying stress for younger adults.

Participants highlighted the financial and emotional concerns associated with job and driving loss, that can impede the ability of younger people to live well with dementia. This supports previous research reporting that loss of income and unplanned retirement can induce additional strain (Scott et al., 2023) and impact younger adults’ sense of self and purpose (Roach and Drummond, 2014). Furthermore, loss of driving can reduce independence (Tolhurst, Bhattacharyya and Kingston, 2014) and cause younger adults to perceive themselves as a burden, worsening depressive symptoms (Scott et al., 2023). The sense of identity and independence are important aspects of adulthood (Harris and Keady, 2009), however, as individuals age so there is some expected dependency (Harris and Keady, 2004). Therefore, whilst both older and younger adults report grief over an accumulation of losses (Cations, 2023), younger adults may feel this more intensely due to these changes happening at an earlier age than expected (Harris and Keady, 2009).

The first theme also demonstrated concerns about the impact of dementia on family roles and relationships, specifically parent-child relationships, and sexual and emotional intimacy with partners. Harris and Keady (2009) have proposed that when younger people with dementia are unable to perform expected family roles, such as parenting duties, then stress and conflict can occur, suggesting that family worries can impact on a person’s ability to live well with dementia. Furthermore, after diagnosis intimate relationships often change in favour of care relationships affecting perceived relationship quality (Chirico, 2002). Declines in relationship quality, where intimacy and sexuality are a lower priority, are associated with increased frustration, tension, and separation (Holdsworth and McCabe, 2018). This may impact on a person’s ability to live well with dementia as shared love and commitment may be integral aspects of coping mechanisms (Holdsworth and McCabe, 2018), while having quality time together is important to allow couples to relearn how to interact (Popok et al., 2022). Both the partners and children of those living with dementia have highlighted that communication about diagnosis is important for adaptive coping (Bannon et al., 2021; Svanberg, Stott and Spector, 2010), suggesting that encouraging conversations with family can facilitate families living as well as possible.

Theme 1 highlights that younger adults may have a wide range of concerns that could potentially impede their ability to accept and adjust to diagnosis. Unique challenges such as the loss of their job, the need to stop driving and changes to family roles and relationships, may be at the forefront of younger adult’s minds, provoking additional fear, guilt, and stress. As LivDem aims to facilitate discussing diagnosis, its implications, and reducing fear around dementia, these could be important topics to consider incorporating within a course tailored for younger adults living with dementia.

Theme two, ‘Good to be with peers’: The Importance of Age-Appropriate Support, offered insight into some of the difficulties in providing effective support for younger people. First, it highlighted how the predominantly older demographics of typical LivDem participants may impede access for younger adults and negatively impact on those who attend. Younger adults have previously reported viewing dementia support groups negatively (Tolhurst et al., 2014), as they mainly catered for older adults (Rabanal et al., 2018).

Alongside the concerns raised about predominantly older groups, results suggest that a LivDem course specifically for younger adults could potentially be beneficial. Prior research has also found that similar-aged groups are more inclusive, as they enable support from those who understand the unique situation (Stamou et al., 2021), thereby fostering empowerment (Rabanal et al., 2018) and allowing advice for specific daily challenges to be shared (Gerritzen, Kohl, Orrell and McDermott, 2023). However, the rarity of young onset dementia and lack of referrals to services reported here reiterates Giebel et al.’s (2020) concern that the limited flow of younger adults through services may restrict the number of specific groups for young people that post-diagnostic services can run.

One possible solution to this barrier may be the delivery of online sessions – however respondents in our study differed in how helpful they thought this might be. Online sessions were seen as ways of overcoming difficulties for potential participants in getting to sessions and would allow more flexibility, which younger adults may need due to their caring commitments and employment (Stamou et al., 2021). However, participants felt that either in-person or a mixture of online/in-person would be most appropriate. This echoes the work of Gerritzen et al. (2023) who found that individuals accessing online dementia peer support sessions enjoyed attending from the comfort of their own homes but missed in-person sessions. However, in contrast to these concerns LivDem has been successfully adapted online in Italy, where the group continued to meet a year after the course ended (Wright, 2023), suggesting that good group relations can indeed be fostered online.

4.1. Implications

This research could be utilised to inform adaptions to, or warrant future research into adapting, the LivDem course, so that it is more accessible and impactful for younger adults living with dementia. The reduced access to post-diagnostic support for younger adults living with dementia is widespread (Nwadiugwu, 2021), and is not just limited to LivDem, therefore this research may offer insight for other post-diagnostic courses seeking to tailor sessions for younger adults living with dementia.

This research also reinforces the need to move away from pharmacological approaches to emphasising wellbeing in dementia care (James and Jackman, 2017). Furthermore, acknowledging and respecting younger adult’s unique experiences enables person-centred support to be based on individual preferences and priorities (Berglund, Gillsjö and Svanström, 2019). Adapting post-diagnostic interventions for younger individuals is vital as they embed coping strategies early on in dementia progression (Bamford et al., 2021), a time where the experience of loss is especially prominent for younger adults (Van Vliet, 2017).

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

While LivDem facilitators are ideally placed to be able to comment on potential adaptations of LivDem, we only succeeded in recruiting a relatively low number of respondents. At the same time the use of qualitative analysis to complement the quantitative questions enabled us to potentially identify good practice (Campbell et al., 2021).

Most participants within this study were white British, female, and working in roles that require a degree - which perhaps reflects the over reliance of psychological sciences on WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) samples Muthukrishna et al., 2020).

4.3. Recommendations

Future research should explore younger adults’ own perspectives on adapting the LivDem course. Younger adults could offer insight and reflections about their experiences of adjusting following a diagnosis and thus shape an adapted LivDem intervention to ensure it meets the needs of those it aims to help.

5. Conclusions

This study explored some of the unique and sometimes overwhelming challenges faced by younger adults who are diagnosed with dementia. In line with previous research, the results support the need for post-diagnostic interventions to be tailored to the specific needs of this group. Failure to focus on the unique needs of younger adults for support, means that many will continue to struggle unnecessarily to adjust and cope following a dementia diagnosis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C., N.W., E.D. and G.W.; methodology, R.C. and G.W.; software, G.W.; validation, G.W. and R.C.; formal analysis, G.W.; investigation, GW; resources, G.W.; data curation, G.W.; writing—original draft preparation, G.W. and R.C.; writing—review and editing, N.W., R.C. E.D. and G.W.; supervision, R.C.; project administration, E.D.; funding acquisition, R.C.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding however this research was carried out as part of GW’s undergraduate final year dissertation where she received supervision from RC and the wider LivDem team of NW and ED.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of The University of the West of England on 20th November 2023 (reference LB2023006).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available from the lead author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Amy Power who supported the creation of the survey and completion of the ethics application for this study. We would also like to thank the course facilitators who took the time to complete the survey.

Conflicts of Interest

Richard Cheston is a co-author of The Living Well with Dementia Course – A Workbook for Facilitators and receives royalties from this.

References

- Alzheimer’s Research UK. (2023). Statistics about dementia. https://www.dementiastatistics.org/about-dementia/.

- Bamford, C., Wheatley, A., Brunskill, G., Booi, L., Allan, L., Banerjee, S., Harrison Dening, K., Manthorpe, J., & Robinson, L. (2021). Key components of post-diagnostic support for people with dementia and their carers: A qualitative study. Plos one, 16(12), 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Bannon, S. M., Grunberg, V. A., Reichman, M., Popok, P. J., Traeger, L., Dickerson, B. C., & Vranceanu, A. M. (2021). Thematic analysis of dyadic coping in couples with young-onset dementia. JAMA Network Open, 4(4), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Beresford, P. (2011). Supporting people: Towards a person-centred approach. Policy Press.

- Berglund, M., Gillsjö, C., & Svanström, R. (2019). Keys to person-centred care to persons living with dementia–experiences from an educational program in Sweden. Dementia, 18(7-8), 2695-2709. [CrossRef]

- Busted, L. M., Nielsen, D. S., & Birkelund, R. (2020). “Sometimes it feels like thinking in syrup”: The experience of losing sense of self in those with young onset dementia. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 15(1), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful Qualitative Research. Sage.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. [CrossRef]

- Brooker, D., Dröes, R. M., & Evans, S. (2017). Framing outcomes of post-diagnostic psychosocial interventions in dementia: The Adaptation-Coping Model and adjusting to change. Working with Older People, 21(1), 13-21. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K. A., Orr, E., Durepos, P., Nguyen, L., Li, L., Whitmore, C., Gehrke, P., Graham, L., & Jack, S. M. (2021). Reflexive thematic analysis for applied qualitative health research. The Qualitative Report, 26(6), 2011-2028. [CrossRef]

- Carter, J., Jackson, M., Gleisner, Z., & Verne, J. (2022). Prevalence of all cause young onset dementia and time lived with dementia: Analysis of primary care health records. Journal of Dementia Care, 30(3), 1-5. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10148679.

- Cations, M. A. (2023). A devastating loss: Driving cessation due to young onset dementia. Age and Ageing, 52(9), 1-3. [CrossRef]

- Cheston, R. (2021). Attended dementia: Managing the terror of dementia. Bulletin of the BPS Faculty of Psychology of Older People, 156, 8-12.

- Cheston, R., & Christopher, G. (2019). Confronting the existential threat of dementia: An exploration into emotion regulation. Springer.

- Cheston R. & Dodd, E. (2020) The LivDem model of post diagnostic support for people living with dementia: Results of a survey about use and impact. Psychology of Older People: the FPOP Bulletin 2020, April, 47-51.

- Dementia UK. (2025) What is dementia? https://www.dementiauk.org/information-and-support/about-dementia/what-is-dementia/.

- Cheston, R., Dodd, E. & Woodstoke, N.S., (2023). Using assimilation to track changes in talk during a Living Well with Dementia (LivDem) group. In Proceedings of the Society for Psychotherapy Research Annual Conference, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland (22nd June 2023).

- Cheston, R. & Marshall, A. (2019). The Living Well with Dementia Course: A Workbook for Facilitators. Routledge.

- Chirico, I., Ottoboni, G., Linarello, S., Ferriani, E., Marrocco, E., & Chattat, R. (2022). Family experience of young-onset dementia: The perspectives of spouses and children. Aging & Mental Health, 26(11), 2243-2251. [CrossRef]

- De Luca, R., De Cola, M. C., Leonardi, S., Portaro, S., Naro, A., Torrisi, M., Marra, A., Bramanti, A. & Calabrò, R. S. (2021). How patients with mild dementia living in a nursing home benefit from dementia cafés: A case-control study focusing on psychological and behavioural symptoms and caregiver burden. Psychogeriatrics, 21(4), 612-617. [CrossRef]

- El Baou, C., Saunders, R., Buckman, J. E., Richards, M., Cooper, C., Marchant, N. L., Desai, R., Bell, G., Fearn, C, Pilling, S., Zimmerman, N., Mansfield, V, Crutch, S., Brotherhood, E., John, A., & Stott, J. (2024). Effectiveness of psychological therapies for depression and anxiety in atypical dementia. Alzheimer's & Dementia, 20(12), 8844-8854. [CrossRef]

- Gerritzen, E.V., Kohl, G., Orrell, M., & McDermott, O. (2023). Peer support through video meetings: Experiences of people with young onset dementia. Dementia, 22, 218–234. [CrossRef]

- Giebel, C., Eastham, C., Cannon, J., Wilson, J.; & Pearson, A. (2020). Evaluating a young onset dementia service from two sides of the coin: Staff and service user perspectives. BMC Health Services Research, 20, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, N., & Smith, R. (2016). The experiences of people with young-onset dementia: A meta-ethnographic review of the qualitative literature. Maturitas, 92, 102–109. [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, N., Smith, R., Akhtar, F., & Richardson, A. (2017). A qualitative study of carers’ experiences of dementia cafés: A place to feel supported and be yourself. BMC Geriatrics, 17, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Harris, P. B. & Keady, J. (2004). Living with early onset dementia: Exploring the experience and developing evidence-based guidelines for practice. Alzheimer's Care Today, 5(2), 111-122.

- Harris, P.B. and Keady, J. (2009). Selfhood in younger onset dementia: Transitions and testimonies. Aging Mental Health, 13, 437–444. [CrossRef]

- Holdsworth, K. & McCabe, M. (2018). The impact of younger-onset dementia on relationships, intimacy, and sexuality in midlife couples: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(1), 15-29. [CrossRef]

- James, I. A., &; Jackman, L. (2017). Understanding behaviour in dementia that challenges: A guide to assessment and treatment. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Javadi, M., & Zarea, K. (2016). Understanding thematic analysis and its pitfalls. Journal of Client Care, 1(1), 34–40. https://doi:10.15412/J.JCC.02010107.

- Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 22(140), 55.

- Woodstoke, N.S., Winter, B., Dodd, E., & Cheston, R. (2024). “How can you think about losing your mind?”: A reflexive thematic analysis of adapting the LivDem group intervention for couples and families living with dementia. Dementia, 24(2), 269-289. [CrossRef]

- Millenaar, J. K., Bakker, C., Koopmans, R. T., Verhey, F. R., Kurz, A., & de Vugt, M. E. (2016). The care needs and experiences with the use of services of people with young-onset dementia and their caregivers: A systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(12), 1261-1276. [CrossRef]

- Muthukrishna, M., Bell, A. V., Henrich, J., Curtin, C. M., Gedranovich, A., McInerney, J. & Thue, B. (2020). Beyond Western, Educated, Industrial, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) psychology: Measuring and mapping scales of cultural and psychological distance. Psychological Science, 31(6), 678-701. [CrossRef]

- Nwadiugwu, M. (2021). Early-onset dementia: Key issues using a relationship-centred care approach. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 97(1151), 598-604. [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M. (2013). The social model of disability: Thirty years on. Disability & Society, 28(7), 1024-1026.

- Popok, P. J., Reichman, M., LeFeber, L., Grunberg, V. A., Bannon, S. M., and Vranceanu, A. M. (2022). One diagnosis, two perspectives: Lived experiences of persons with young-onset dementia and their care-partners. The Gerontologist, 62(9), 1311-1323. [CrossRef]

- Rabanal, L.I., Chatwin, J., Walker, A., O’Sullivan, M., & Williamson, T. (2018). Understanding the needs and experiences of people with young onset dementia: A qualitative study. BMJ Open, 8, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Roach, P., & Drummond, N. (2014). ‘It's nice to have something to do’: Early-onset dementia and maintaining purposeful activity. Journal of Psychiatric and Ment Health Nursing, 21(10), 889-895. [CrossRef]

- Scott, T. L., Rooney, D., Liddle, J., Mitchell, G., Gustafsson, L., Pachana, N. A. (2023). A qualitative study exploring the experiences and needs of people living with young onset dementia related to driving cessation: ‘It’s like you get your legs cut off’. Age and Aging, 52(7), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Stamou, V., Fontaine, J.L., O’Malley, M., Jones, B., Gage, H., Parkes, J., Carter, J., & Oyebode, J. (2021). The nature of positive post-diagnostic support as experienced by people with young onset dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 25, 1125–1133. [CrossRef]

- Svanberg, E., Stott, J., & Spector, A. (2010). ‘Just helping’: Children living with a parent with young onset dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 14(6), 740-751. [CrossRef]

- Tolhurst, E., Bhattacharyya, S. and Kingston, P. (2014). Young onset dementia: The impact of emergent age-based factors upon personhood. Dementia, 13(2), 193-206. [CrossRef]

- Van Vliet, D., Persoon, A., Bakker, C., Koopmans, R. T., de Vugt, M. E., Bielderman, A., Gerritsen, D. L. (2017). Feeling useful and engaged in daily life: exploring the experiences of people with young-onset dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 29(11), 1889-1898. [CrossRef]

- Williams, M. & Moser, T. (2019). The art of coding and thematic exploration in qualitative research. International Management Review 15(1), 45-55.

- Wright, L. (2023). The Living Well with Dementia course goes online co creation of an Italian. In Proceedings of Alzheimer Europe, Helsinki, Finland, 16th-28th October 2023.

- World Health Organization. (2023, March 15). Dementia. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia.

- Young Dementia Network. (2025). What is young onset dementia? www.youngdementianetwork.org/about-youngonset-dementia/what-is-young-onset-dementia.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).