1. Introduction

There are several types of eye movements that are used in everyday life: conjugate (saccades and smooth pursuit, which help to explore the two-dimensional visual field) and disjungate (vergence, which helps to explore the three-dimensional visual field). All these eye movements are of great importance in sports activities, especially in teams’ sports where athletes have to notice and follow not only dynamic target (ball, hockey puck, frill), but also the location and movements of their teammates. The accuracy of eye movements tends to vary from person to person. Some studies claim that persons who regularly engage in active sports as well as professional athletes have better eye movement accuracy than "novices" or non-athletes [

1]. Professional athletes also have better control of their eye movements [

2] and even use special viewing strategies [

3].

Various eye training complexes are developed to improve the speed and accuracy of eye movements, for example, a special training program called “Dr.Revien’s Eye Exercises for Athletes” [

4], the video package Eyerobics [

5], and the special program “Quiet eye” [

6]. The system RightEye can be used both for training and evaluating eye movements thanks to an eye tracking system that is implemented in the device.

The efficiency of these training programs and vision training in general has been studied not only in adults but also in children [

7,

8]. Evaluation of Dr.Revien’s Eye Exercises for Athletes and Eyerobics program [

9] revealed no significant effect on visual function and eye movements. However, Adolphe et al. [

10] compared eye movements for volleyball players before and after a six-month vision training complex. As a result, it was found that the accuracy of eye movements improved significantly after vision training. The accuracy of the volleyball shots improved by 7%; the achieved result was maintained for three years after vision training. The accuracy of basketball players' free throws improved significantly in the first year after vision training with a similar training program [

11]. Even after two years, the improvement in throw accuracy was 22% [

11]. The effect of vision training on the accuracy of free throws in basketball was also demonstrated in later studies [

12]. An improvement in athletic performance after a vision training complex was observed for football players [

13], skeet shooters [

14], and darts players [

15]. Thus, a number of studies show that eye movement training significantly improves performance in both amateur and professional sports.

Eye movements can be trained as a complex or separately for each type of movement. Santamaria and Story [

16] conducted a study training both horizontal saccades and smooth pursuit movements in two groups: young (17–31 years old) and elderly (60–78 years old) participants. As a result, no significant improvement in saccades was observed in any of the groups after a two-week training course. In turn, smooth pursuit movements improved in both age groups [

16]. Bibi and Edelman [

17] demonstrated an improvement in saccadic reaction time after 6-12 training sessions. Jóhannesson et al. [

18] specified that saccadic training improved not only the latency but also the peak velocity. The authors assumed that after a training session, the generation of saccades becomes more automatic and requires less effort.

The equipment used in vision training for athletes varies depending on its application form. For example, a special equipment is used for in-office training under professional optometrist supervision. One of the most popular in-office devices for saccadic training is the Wayne saccadic fixator (currently the Binovi Touch saccadic fixator). However, new systems appear on the market, such as the Reflextion system, which works in a similar manner as the Binovi Touch saccadic fixator. The COVID pandemic boosted the offer of home-based training for athletes. For example, RightEye and VisualEdge have an option for online training at home where stimulus is demonstrated on a computer screen. Most of the previously described systems and programs are high-cost systems. Therefore, some simple offers (with video explanations) are available, e.g., on the website of the International Sports Vision Association. However, there is a gap in terms of equipment that could be used in home-based training to improve eye movements and studies that demonstrate the efficiency of home-based training for athletes. The aim of our study was to test the application of a new vision training device, the EYE ROLL (SIA EyeRoll, Latvia), for home-based eye movement training in athletes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The main inclusion criteria were: (1) professional athletes that have sport training at least three times a week; (2) no general or ocular diseases; (3) no head or eye surgeries; and (4) no medication. To ensure sufficient eye tracking results, athletes had additional inclusion criteria: (1) binocular non-corrected visual acuity at near 0.4 (LogMAR) or better; no amblyopia, no extraocular muscle problems, no manifest strabismus, and no diplopia.

Sixty-seven participants (10 females and 57 males) were involved in the study.

Table 1 demonstrates the distribution of various sports disciplines included in the study. All participants were randomly (not considering their sport discipline) divided into three groups on the first visit (Visit 1): Group 1 – control group (no training); Group 2 – eye movement training with no device; and Group 3 – eye movement training with the new device (EYE ROLL) (see

Table 2). After four weeks (Visit 2), there was a 25% drop-out of participants; only 51 participants completed the study at least for four weeks. Therefore, we changed the study design and offered all participants an additional four weeks, but in different groups. If they were in Group 1 for the first four weeks, they can change to Group 2 or Group 3 for the following four weeks; if they were in Group 2 or Group 3 for the first four weeks, they changed to Group 1 (data were not analysed). To summarize, Group 1 had 11 participants (data evaluated only for Visit 1 and Visit 2; median, IQR: 24, 7 years, 18-41 years). In an 8-week period, Group 2E (enlarged Group 2) had 17 participants (median, IQR: 21, 8 years, 15-46 years; only 16 participants had useful data for statistical analyses) and Group 3E (enlarged Group 3) had 23 participants (median, IQR: 22, 9 years, 14-42 years; only 22 participants had useful data for statistical analyses). For Group 2E and Group 3E, we analysed results at pre-training and post-training visits (where training was for four weeks).

2.2. Study Procedure

Across all visits, participants underwent the same assessment procedure: (1) a comprehensive vision examination performed by three qualified optometrists and (2) saccadic eye movement recordings via the EyeLink 1000 Plus. Before the first visit, all participants filled a questionnaire capturing general information, information about vision correction, regular training activity, and associated information about sport performance (see Supplement 1).

2.4. Vision Examination

The vision examination included objective refraction (dry autorefractometry, Huvitz HRK-1), assessment of uncorrected visual acuity with the Snellen decimal chart, assessment of subjective refraction, and evaluations of both distance and near binocular functions. The latter included the Worth four-dot suppression test, stereovision assessed by the Ostenberg and Titmus tests, heterophoria measurement with the Maddox rod test, and both positive and negative fusional reserves measured with a prism ruler. We evaluated ocular motility, the near point of convergence using the RAF ruler, and saccadic and smooth pursuit with the NSUCO method. Accommodative function evaluation included positive and negative relative accommodation, binocular accommodative facility (±2.00 D flipper or Wick technique for participants aged 30 or older [

19]), dynamic retinoscopy MEM method, and monocular accommodative amplitude. A thorough examination of both anterior and posterior eye structures was performed to rule out any anterior or posterior ocular disorders, with particular attention to the dry eye syndrome. Based on the standards established by Scheiman and Wick [

19], normal values for visual functions and accommodative and non-strabismic binocular abnormalities were determined.

2.5. Questionnaire

The questionnaires had to be filled out online prior to the visits. It contained general questions about a participant, their vision and ocular condition, as well as their general health, previous treatments, surgeries, and medications. Participants had to describe their sport discipline, frequency of training, subjective state, stress level, and performance in sport. To track the compliance of participants, all participants were provided with a compliance table to capture their regular training activities and hours spent sleeping. Additionally, both training groups recorded the daily occurrences of their saccadic training time and duration.

2.6. Assessment of Saccadic Movements

The study used the high-resolution (500 Hz) infrared video-based EyeLink 1000 Plus (SR Research, Canada) eye-tracking device. This device detects the pupil using the dark pupil algorithm and captures corneal reflections [

20]. A BenQ Model XL2430B monitor with a 1920 x 1080 resolution and a 533 mm by 300 mm screen size was used to display visual stimuli. The camera was adjusted to be 60 cm from the participant's eye level and the monitor was placed 93 cm away. To ensure consistent head placement while collecting data, participants used a forehead-chin rest provided by SR Research. No glasses or contact lenses were worn during the measurements. The major cause of some participants' lack of saccadic movement data was eye makeup, such as mascara or eyeliner, which interfered with calibration and validation procedures, consequently compromising the accuracy of saccadic measurement.

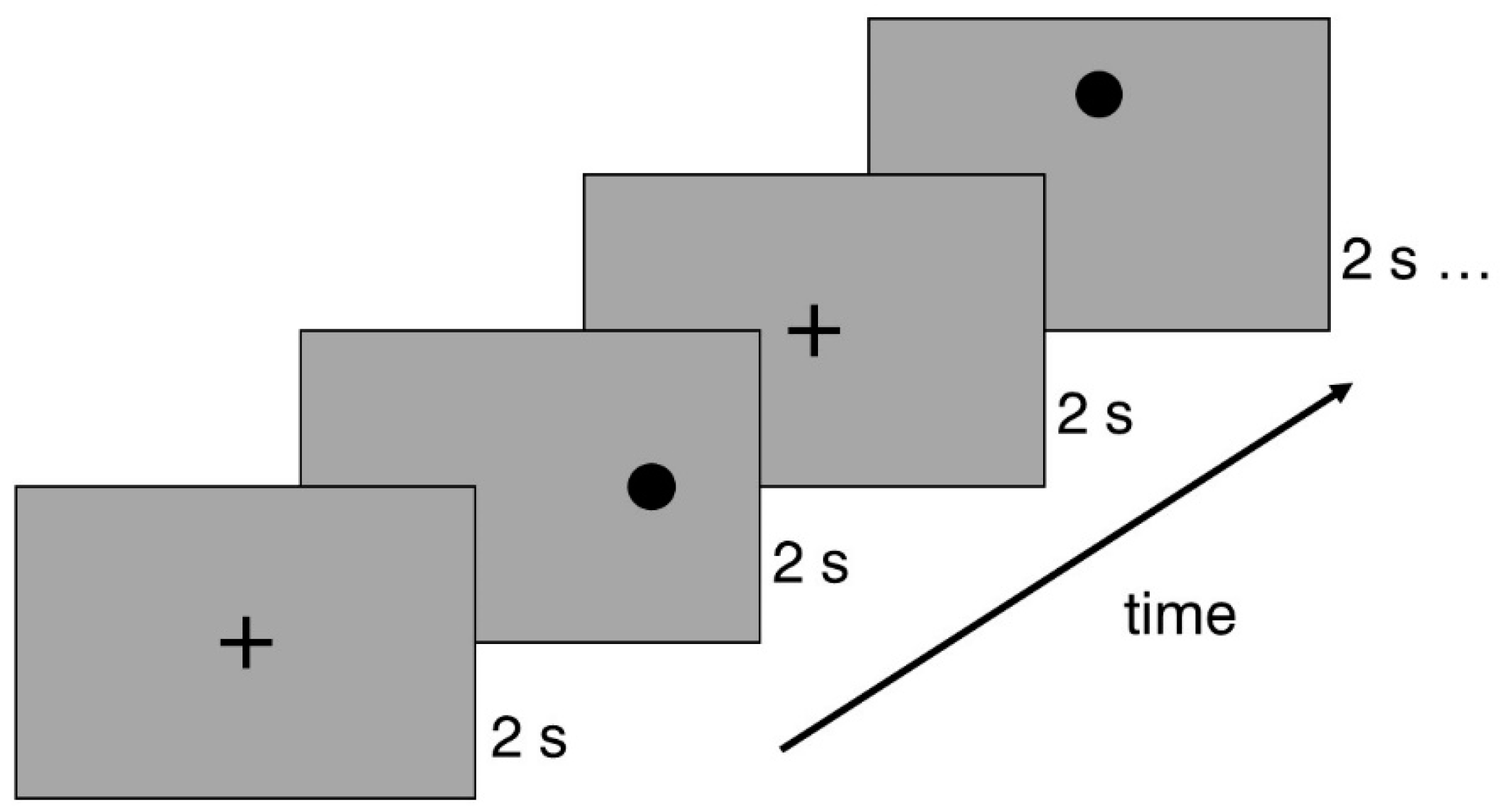

The Experiment Builder software (SR Research, Canada) was used to build the saccadic stimulus and its corresponding sequences. The saccadic stimulus was a black dot with a diameter of 1° (RGB 0; 0; 0), placed on a grey background (RGB 166; 166; 166) with an average luminance of 80 cd/m2. Each slide in the presentation sequence included a single point that was positioned either horizontally (5° or 10°) or vertically (3° or 6°) from the screen's center. The sequence began with a central cross displayed for two seconds, followed by the two-second stimulus presentation. Subsequently, the central cross slide reappeared after each stimulus presentation (see

Figure 1). The experiment was organized into three different sequences of saccadic stimuli, with each point position slide repeated three times. Thus, each sequence contained eight saccadic stimuli, arranged in a randomized order.

Prior to data collection, participants received verbal instructions to maintain a steady head position and focus on sequentially appearing dots and crosses without any head movements. The participant was also given the option to adjust their chair for optimal comfort. While blinking was permitted during the fixation phase, participants were told to avoid blinking during saccadic movement. The recordings were conducted in a well-illuminated room with an average illumination of 687 ± 3 lx (Illuminance Meter T-10WS).

2.7. Vision Training

Group 2 and Group 3 performed similar training with different types of realizations. Both saccadic and smooth pursuit stimuli were used in the training (see

Table 3). In Group 2, exercises were performed standing at a distance of 1 m from the wall. For saccadic stimuli, six A3 sheets with printed tasks were given to each participant in Group 2. Participants were instructed to attach the sheets to the wall at eye level or slightly below. During the exercises, the participant had to look at the stimuli without moving their head and quickly and accurately change their fixation in between targets. Smooth pursuit tasks were performed by using a red laser pointer that the participants themselves pointed to the wall. Without moving the heads, participants had to follow the flashlight with their eyes, moving the laser pointer in the described pattern.

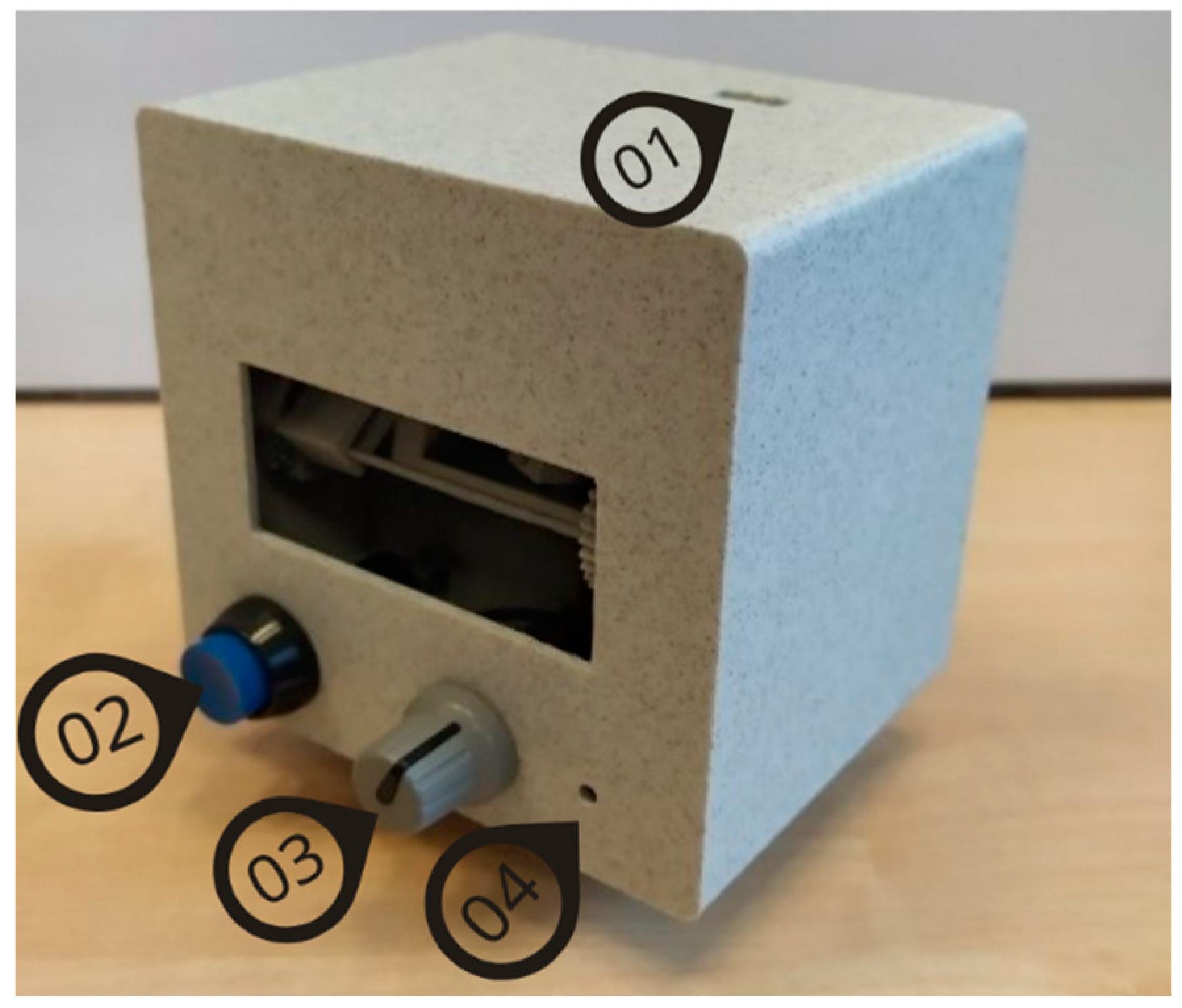

Group 3 used EYE ROLL, a novel device (see

Figure 2) designed to facilitate a complex of exercises that are analogous to manual vision relaxation exercises and eye movement improvement training exercises. The participants in this study used only exercises designed for eye movement training. They were instructed to ensure an ambient lighting level for better visibility of the laser dot. The dot must be projected on light-colored surfaces, such as grey or white, to ensure higher contrast. The device, when placed on a level surface using its stand, should be at least 2 meters away from the projection surface, with both the user and device maintaining this distance. The participant can take a stable standing position. The laser dot's movement amplitude in both horizontal and vertical directions can range from 10° to 50°. Although participants had the flexibility to adjust the amplitude based on the available projection area, the maximum amplitude was advised. By turning on the device, the training is started, and the participant has to follow with the eyes the pattern drawn with the laser dot: the dot appears in different locations for saccadic stimulation or moves with a defined speed and trajectory for smooth pursuit stimulation. By pressing the control button (see

Figure 2), the participant could stop the training. When this button was pressed again, the training from the previously paused exercise was resumed.

The device employs a widened laser beam to produce a sizable point (a 1.15° red laser dot), mitigating potential risks. The EYE ROLL features a Class 3R laser (650 nm, 5 mW), which is generally considered safe for the eyes. However, extended direct or reflected exposure can pose risks, while brief exposures or radiation dispersed from non-reflective surfaces, such as walls or doors, are considered harmless. Prior to initiating device utilization, participants were advised on safety precautions: (1) avoid direct gaze into the laser beam; and (2) ensure that the laser always points away from the user and other individuals and that the training surface is free from reflective objects and mirrors.

Participants in both training groups were instructed to undertake exercises at least once a day, five days a week. If participants had problems keeping the head still, it was recommended that they place a book on the head to control head movements.

2.8. Data Analysis

The following data were analyzed from a comprehensive vision examination: uncorrected visual acuity, subjective refraction (expressed as a spherical equivalent), phoria at distant and near fixation, fusional reserves, near point of convergence, positive and negative relative accommodation, binocular accommodative facility, and accommodative amplitude. Visual acuity was transformed from decimal units to LogMAR units for simpler analyses of visual acuity taking mistakes (missed or incorrectly named optotypes) into account.

DataViewer (SR Research) was used to export the saccadic movement data for each participant on each visit as Excel files. We took the binocular amplitude (in degrees), mean velocity (in degrees per second, later called velocity), duration, and peak velocity of the initial saccade from the created data file. For each stimulus location, the results of three repetitions were averaged. If the system recorded a blink during saccadic movement, the results of this saccadic movement were excluded from the analyses. The data from repeated measures were averaged to be used in statistical analyses.

2.9. Statistical Analyses

The IBM SPSS software package version 20.0 was used for statistical analyses. Shapiro-Wilk test was used as normality tests. Mean and standard deviation, as well as the paired t-test and ANOVA (with the Bonferroni post hoc test) were used if majority of the data (50% or more) were normally distributed [

21]. Median, interquartile range (IQR), and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test were used for related data if most of the data (50% or more) were not normally distributed [

21]. Levene’s test for equality of variance was used to evaluate homogeneity of variances. One-way ANOVA was used to evaluate the impact of one parameter (saccadic stimulus) while the data had a homogeneous distribution of variances [

21]. Mixed model ANOVA was used to evaluate changes in saccadic parameters in relation to various affecting factors (group as a between-subjects factor and direction, visit, sport discipline, and eye dominance as within-subject factors).

3. Results

3.1. Visual Functions Comparing Results on Visit 1 and Visit 2

The visual function of 51 participants was evaluated by comparing data before (Visit 1) and after a 4-week period (Visit 2) (see

Table 4). All participants had no motility problems, good binocular single vision both at far and near, and stereovision at far and near (40-400 arc sec; median = 40 arc sec (IQR = 10)). The range of refractive error (evaluated based on the spherical equivalent of the subjective refraction) was -4.38 D to +5.25 D in the right eye and -3.63 D to +5.50 D in the left eye. The best corrected visual acuity at distant and near fixation was 0.0 (LogMAR) in all participants. Only two participants demonstrated head movements during saccades and smooth pursuits tested by the NSUCO method (2-3 points in a 5-point scale: moderate movement of the head at any time or slight movement of the head for more than 50% of the testing time) [

19]. On the following visit, both improved and demonstrated either no head movements (5 points out of 5) or slight head movements (slight movement of the head less than 50% of the testing time) (4 points out of 5).

Group 1 showed statistically significant changes in phorias at distant fixation (esophoric shift) (Wilcoxon singed-rank test: Z = -2.081, P = 0.037), worsening of near point of convergence (Wilcoxon singed-rank test: Z = -2.069, P = 0.039), increase in accommodative amplitude only for the right eye (Wilcoxon singed-rank test: Z = -2.516, P = 0.012), and worsening of positive fusional reserves at far (Wilcoxon singed-rank test: Z = -4.657, P < 0.001). Group 2 showed a statistically significant myopic shift in refractive error for the right eye (Wilcoxon singed-rank test: Z = -2.388, P = 0.017) and a decrease in positive fusional reserves at distance (Wilcoxon singed-rank test: Z = -2.572, P = 0.01). There were only six participants in Group 3 on Visit 1. Therefore, we applied nonparametric methods to see the changes in visual functions. There was an increase only in the accommodative amplitude of both eyes on Visit 2 (Wilcoxon singed-rank test: the right eye Z = -2.032, P = 0.042; the left eye Z = -2.2.1, P = 0.028).

3.2. Visual Functions in Enlarged Training Groups

To see the effect of eye movement training on visual functions in a larger group of participants, we analyzed the results of enlarged groups Group 2E and Group 3E (see

Table 5). Group 2E (N = 17) showed a statistically significant myopic shift in refractive error for the right eye (Wilcoxon singed-rank test: Z = -2.536, P = 0.011) and worsening of positive fusional reserves at far (Wilcoxon singed-rank test: Z = -2.549, P = 0.011). Group 3E (N = 23) showed an esophoric shift of phoria at near (Wilcoxon singed-rank test: Z = -2.644, P = 0.008) and improvement of the near point of convergence (Wilcoxon singed-rank test: Z = -2.034, P = 0.042).

3.3. Saccadic Movements Difference Depending on the Sports Discipline

Fifty participants had useful saccadic data on the first visit (see

Table 6). Most of the data (amplitude, mean velocity, duration and peak velocity) were not normally distributed; therefore, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare saccadic parameters in horizontal and vertical directions in all participants. The data demonstrated larger and faster saccadic movements to the right compared to the left both for large and small amplitude saccades (10° amplitude Z = -1.82, P(1-tailed) = 0.034, mean velocity Z = -2.99, P(2-tailed) = 0.001, duration: Z = -2.046, P(2-tailed) = 0.04, peak velocity Z = -4,079, P(2-tailed) < 0.001; 5° amplitude Z = -3.84, P(2-tailed) < 0.001, mean velocity Z = -4.38, P(2-tailed) < 0.001, peak velocity Z = -4,156, P(2-tailed) < 0.001) in all participants. However, saccadic amplitude and velocity were symmetrical in the vertical direction both for large and small saccades (P > 0.05) if all participants were evaluated.

Since athletes representing different sports disciplines participated in our study, they were divided by sports discipline groups, taking into account the specifics of the sports discipline: 15 participants in Discipline 1 (hockey, floorball, and football), 29 participants in Discipline 2 (basketball, handball, and volleyball), and six participants in Discipline 3 (shooting). More than 50% of the data (from three disciplines x four directions x two amplitudes) demonstrated a normal distribution at Visit 1 (amplitude, mean velocity, duration, peak velocity, Shapiro-Wilk test: P > 0.05). Therefore, parametric methods were applied. All data demonstrated equal variance (Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances: P > 0.05). There was no difference between disciplines in horizontal and vertical saccade amplitude, mean velocity and peak velocity (one-way ANOVA: P > 0.05) if one direction was analyzed. However, there was statistically significant difference between discipline and vertical 3° downward saccadic duration (one-way ANOVA: F(2,47) = 4.141, P = 0.022) In Discipline 3, the participants showed shorter saccadic duration compared to Discipline 1 (P = 0.031).

Certain variations across disciplines were evident if opposite directions were compared (pairwise comparisons in mixed model ANOVA with direction as a within-subject factor and discipline as a between-subject factor). The impact of direction was observed only for peak velocity of the initial saccade on the horizontal 10° saccadic stimulus (F(1,47) = 12.035, P = 0.001), where rightward saccades peak velocity is faster compared to leftward, there was no difference between disciplines (P > 0.05); however, the largest difference was observed in Discipline 2 (pairwise comparison: P < 0.001). For a horizontal 5° saccadic stimulus, initial saccades to the right were statistically significantly larger and faster than to the left (amplitude: F(1,47) = 12.126, P = 0.001; mean velocity: F(1,47) = 12.231, P = 0.001; peak velocity: F(1,47) = 17.088, P < 0.001). There was no difference between disciplines (P > 0.05); however, the largest difference was observed in Discipline 2 (pairwise comparison: P(amplitude) = 0.001; P(mean velocity) < 0.001, P(peak velocity) < 0.001 ).

The impact of both direction and discipline was observed for a vertical 6° saccadic stimulus (amplitude: F(2,47) = 3.779, P = 0.03; mean velocity: F(2,47) = 4.416, P = 0.017; peak velocity: F(2,47) = 6.545, P = 0.003). Discipline 1 demonstrated a larger and faster downward saccade than an upward saccade (amplitude: P = 0.02; peak velocity: P = 0.003); no difference in amplitudes was observed in Discipline 2 and Discipline 3 (P > 0.05). Discipline 3 did, however, show a faster upward saccade than a downward saccade (P = 0.014); whereas Discipline 1 and Discipline 2 showed no difference in velocities (P > 0.05). No difference between disciplines was observed for a vertical 3° saccadic stimulus, neither in amplitudes nor velocities (P > 0.05).

There was no difference between disciplines for saccadic duration (P > 0.05); however, the largest difference was observed for a vertical 3° saccadic stimulus, initial downward saccade in Discipline 3 were statistically significant lower duration compared to Discipline 1 (pairwise comparison: P = 0.031).

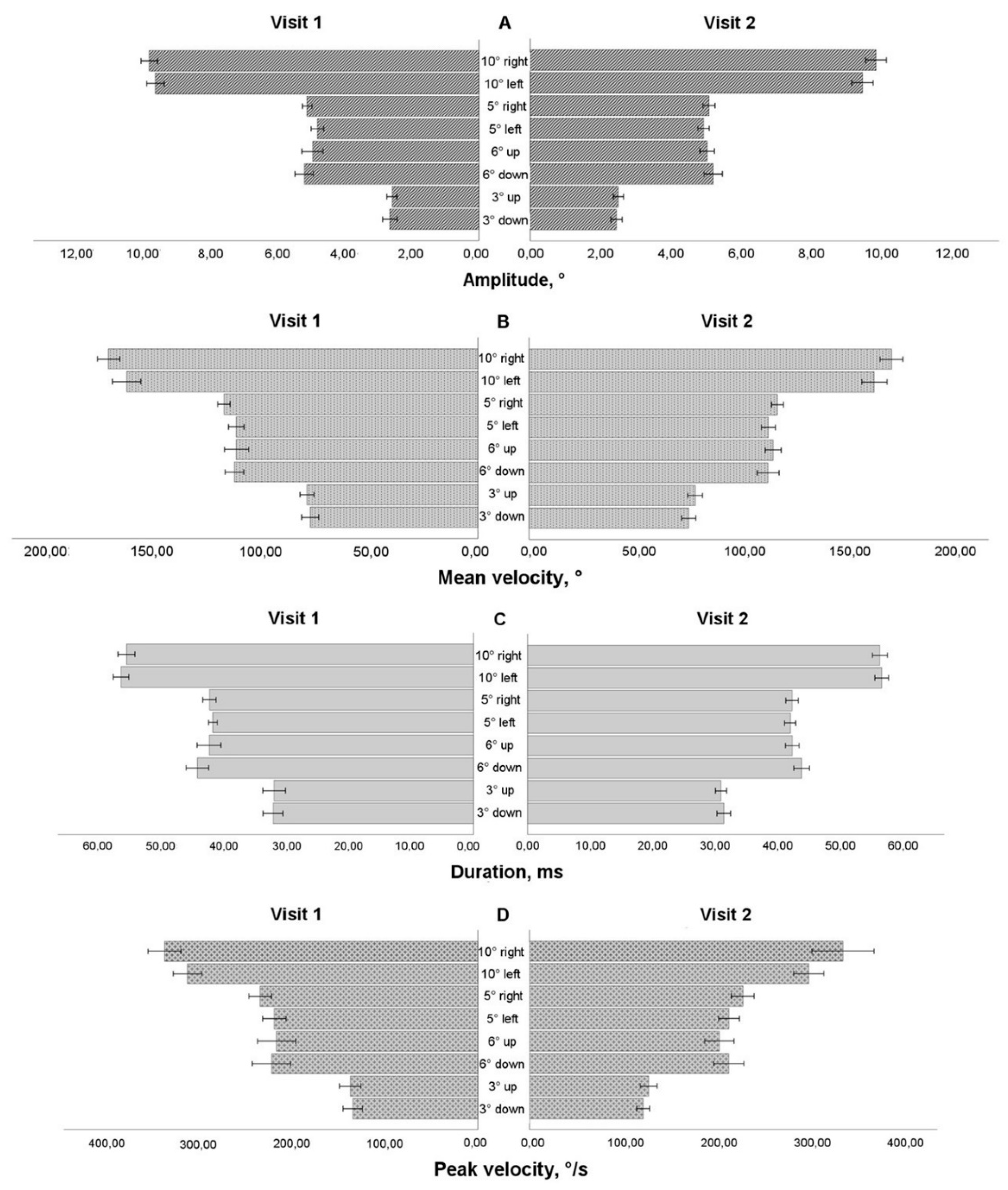

3.4. Results of Saccadic Response for Group 1 on Visit 1 and Visit 2

On the second visit, 30 participants had useful saccadic data, to determine how saccadic characteristic changed after 4 weeks in control group (Group 1), we utilized paired t-test (more than 50% of the data demonstrated normal distribution in the Shapiro-Wilk test). For horizontal saccades on the 10° left saccadic stimulus (see

Figure 4 A), there were shorter saccades compared on Visit 2 compared to Visit 1 (amplitude: t(29) = 2.053, P=0.049 (two-sided)). For vertical 3° downward saccade, the data demonstrated shorter and faster saccadic movements on Visit 2 (amplitude: t(29) = 1.945, P=0.031 (one-sided), peak velocity: t(29) = 2.096, P=0.045 (two-sided). For the duration and mean velocity, there were no statistically significant differences between Visit 1 and Visit 2.

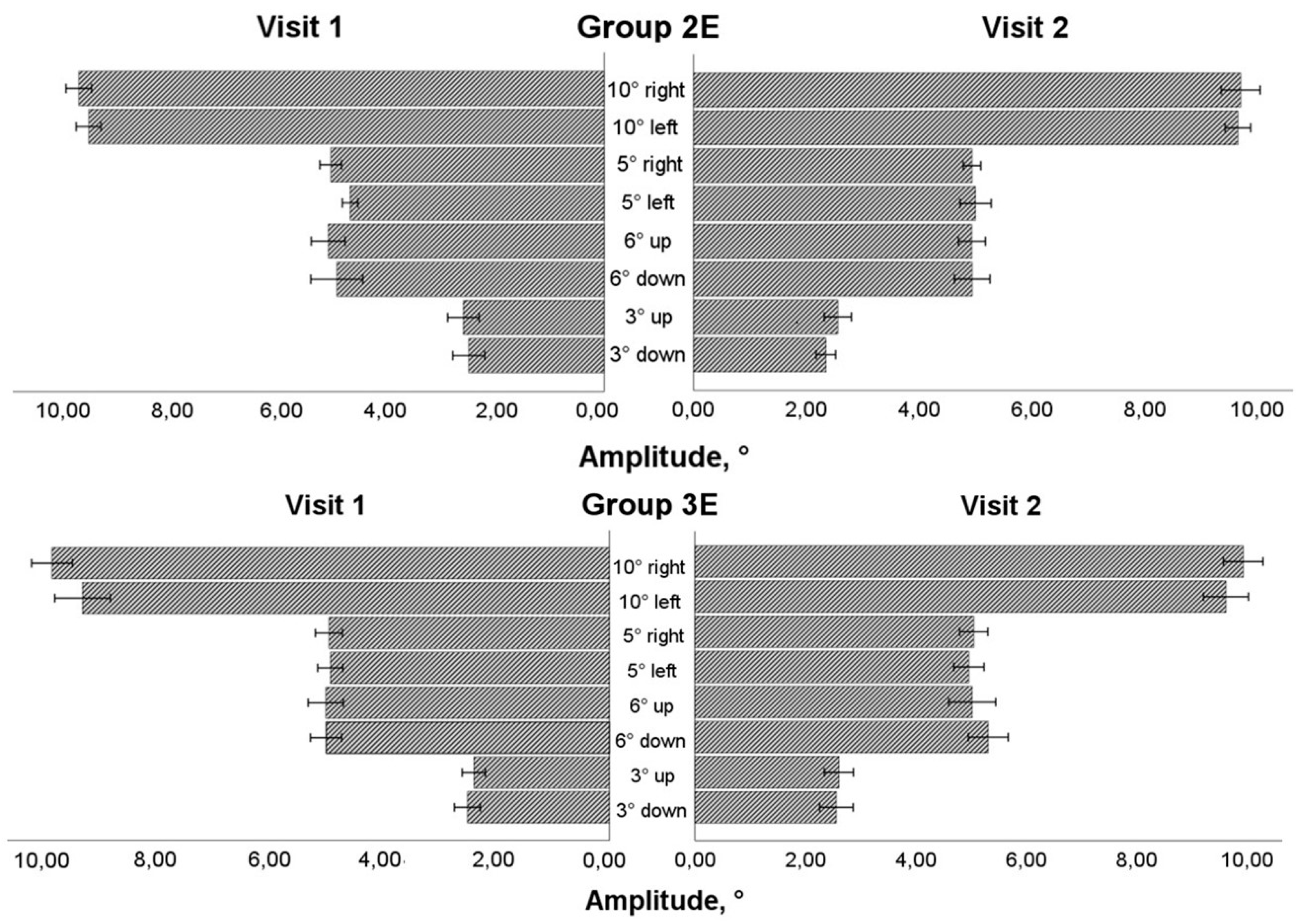

3.5. Saccadic Response in Enlarged Training Groups

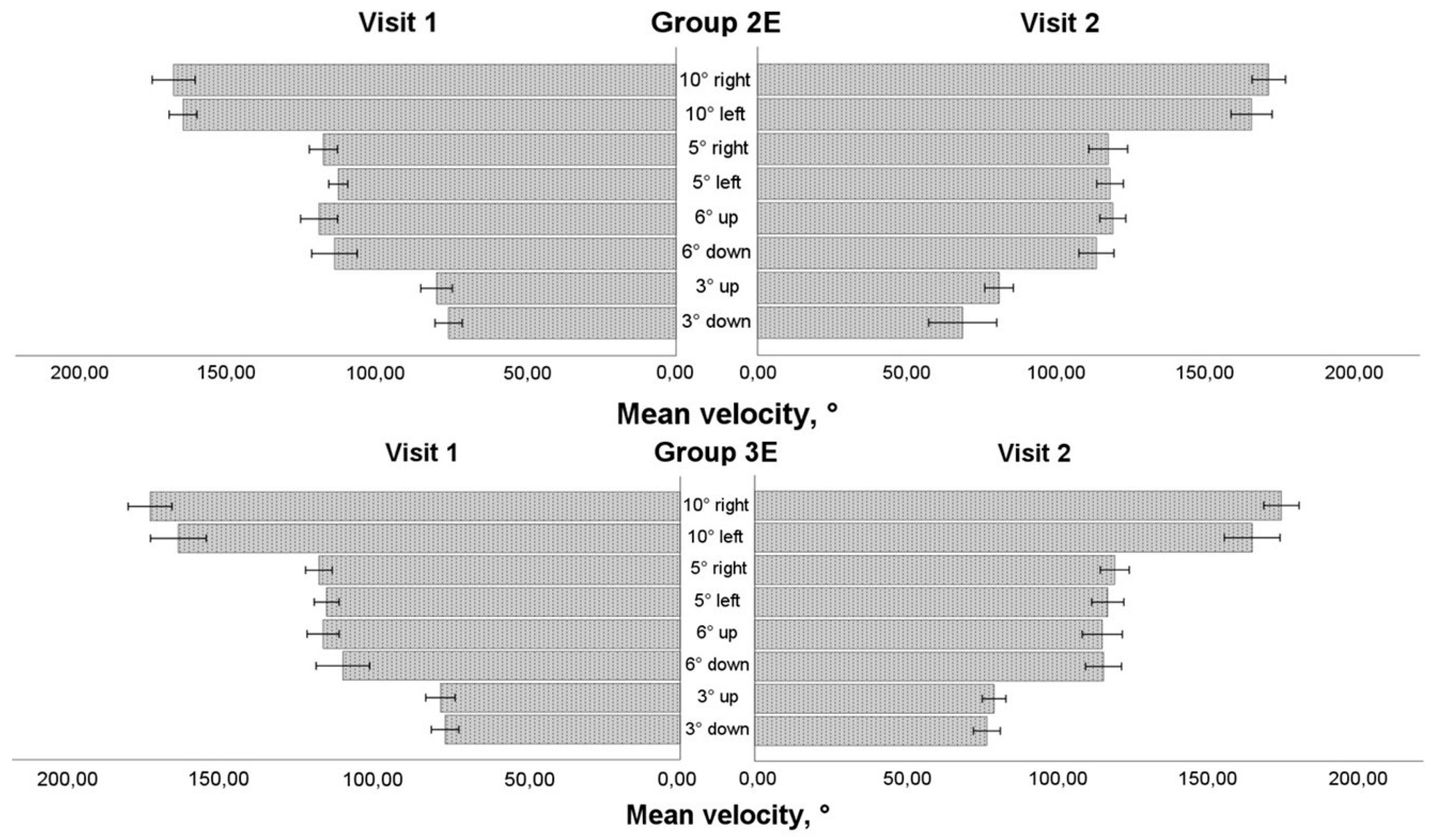

We assessed data solely for individuals who had eye movement training, regardless of the training period (the first or second 4-week period), in order to see the impact of eye movement training in an enlarged sample group (see

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). More than 50% of the data was normally distributed. The results of the mixed model ANOVA test (visit as a within-subject component and group as a between-subject factor) revealed that eye movement training increased the saccadic amplitude while looking to the left for the 10° stimulus and the 5° stimulus (F(1,36) = 4.774, P = 0.035 and F(1,36) = 4.163, P = 0.049, respectively). On the post-training visit, the mean velocity increased (F(1,36) = 6.132, P = 0.018) for the horizontal 5° stimulus. There was no significant difference between the groups; however, a larger increase in amplitude was observed for smaller amplitude or mean velocity on the pre-training visit: Group 3E for the 10° stimulus (changes only in the amplitude) and Group 2E for the 5° stimulus (changes both in amplitude and mean velocity). No changes were observed in vertical directions, both for the 6° and 3° stimuli (P > 0.05).

After 4-week period, no impact of eye movement trainings was observed in duration and peak velocity (P > 0.05). However, in Group 3E, a larger increase in saccade peak velocity was observed for the 10° leftward stimulus in data with smaller peak velocity on the pre-training visit (pairwise comparison: P = 0.017). Conversely, for saccadic duration, larger decrease was observed in Group 2E for smaller peak velocity on the pre-training visit: for horizontal 5° rightward stimulus (pairwise comparison: P = 0.041), and vertical 6° upward stimulus (pairwise comparison: P = 0.037).

Two within-subject characteristics (visit and direction) were employed in the mixed model ANOVA to check for any alterations in the asymmetry of the saccadic response. Both amplitude and mean velocity (See

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) for the horizontal 10° stimulus showed a difference in direction factor with no group differences (amplitude: F(1,36) = 6.122, P = 0.018; mean velocity: F(1,36) = 9.896, P = 0.003). In both training groups, the rightward saccade was larger and faster during pre- and post-training visits. Due to an increase in amplitude and a decrease in horizontal response asymmetry in Group 2E, all variables (visit, direction, and group) had a statistically significant influence on amplitude changes for the horizontal 5° stimulus (F(1,36) = 4.436, P = 0.042). For the vertical 6° stimulus, neither the amplitude nor the mean velocity changed (P > 0.05). There was no difference in the vertical 3° stimulus's amplitude (P > 0.05), but there was a difference in the direction for the saccade's mean velocity on both visits, with the upward saccade moving more quickly than the downward one without a group difference (F(1,36) = 6.426, P = 0.016).

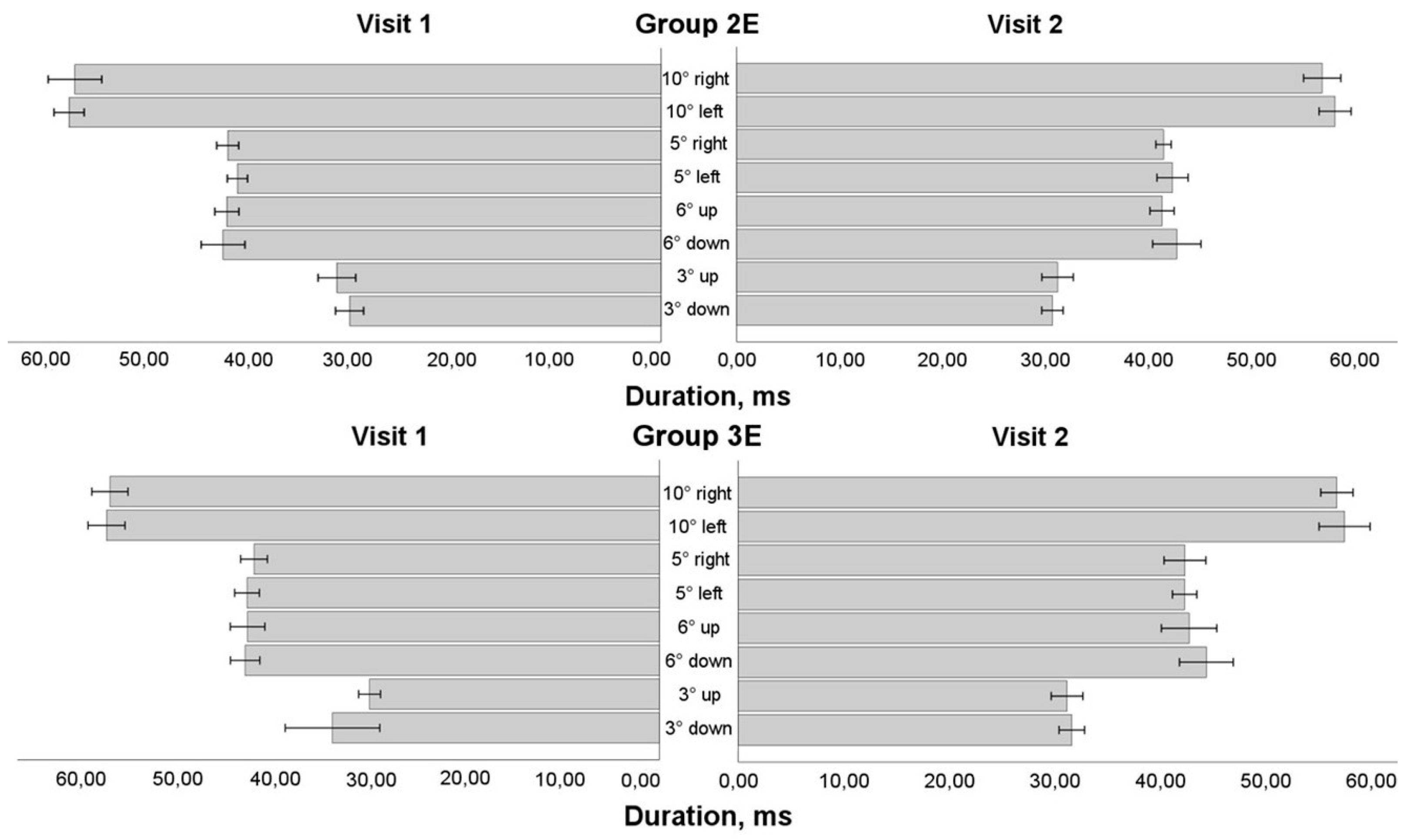

There was no difference for saccadic duration (See

Figure 6) in the horizontal 10° stimulus's amplitude (P > 0.05), but all variables (visit, direction, and group) had a statistically significant influence on duration changes for the horizontal 5° stimulus (F(1,36) = 4.665, P = 0.038), in Group 2E rightward 5° saccades duration statistically significant decreasing in post-training visit. There was no difference for saccadic duration in the vertical direction neither for 6° nor 3° stimulus's amplitude (P > 0.05), however, larger decrease in saccadic duration was observed in 6° upward saccade in post-training visit for Group 2E.

For the horizontal 10° and 5° stimulus amplitude only direction factor showed a difference in peak velocity (See

Figure 7) without group factor differences (10° stimulus: F(1,36) = 12.579, P = 0.001; 5° stimulus: F(1,36) = 23.570, P < 0.001), the rightward saccade was faster during pre- and post-training visits. For the vertical 6° stimulus amplitude statistically significant influence was observed in combination of direction and group factor (F(1,36) = 5.568, P < 0.024).

4. Discussion

The study results demonstrate that a 4-week home-based training program may considerably enhance saccadic symmetry, both for horizontal saccadic response amplitude and mean velocity. When participants were not engaged in any exercises (Group 1), their initial saccade’s amplitude looking to the left (for large saccadic stimuli) reduced and became less accurate. The discrepancy between stimulus and saccadic amplitude was larger than the assumed accuracy (0.5°). In contrast, Group 3 improved, attaining better accuracy in the leftward saccadic amplitude. However, more accurate analyses of accuracy would be useful in the following studies. We think this observation is not occasional. When participants from Group 1 were involved in eye movement training, the amplitude of their left-ward saccades improved. Both enlarged training groups demonstrated improvements in horizontal saccades after exercising, with no difference between groups. Our findings are consistent with those of a previous study [

18], where participants had in-office training (18 sessions) and showed improvement in saccadic amplitude and peak velocity, as well as a reduction in saccadic response asymmetry. As a consequence, even after four weeks of training, our home-based training can ensure comparable outcomes to in-office training, with the EYE ROLL device being just as effective as manual eye movement training. Therefore, we can conclude that the EYE ROLL device can ensure saccadic amplitude and velocity improvement.

One of the key elements for successful home-based training is compliance. If someone trains at home, it is impossible to manage the intensity and length of the workout. The specialist can only hope the training is performed as indicated. In our study, the compliance tables helped to somewhat ensure the frequency and duration of eye movement training. According to the findings shown in these tables, both training groups' compliance rates were high (Group 2E: 75%; Group 3E: 79%). Some participants noted that it was occasionally difficult to find time to complete the training. Some participants observed that they only remembered to complete the training just before leaving for their sports training. In such a scenario, eye movement training would be carried out less effectively and for a shorter period of time. According to compliance tables, Group 2E had one training per day (median; IQR = 0.2) for 10 minutes (IQR = 6 minutes). Group 3E had the training less often than prescribed (median 0.8 times a day; IQR = 0.4) for 13 minutes (median; IQR = 11 minutes). Previous studies demonstrated that the training session should last no less than 3 minutes [

16]. However, better results are reached if training session is 10 minutes [

23], 20 minutes [

17], or 30 minutes [

1] with one or more short breaks for about 20 seconds up to 5 minutes in between exercises [

16,

23]. For office-based training, the required number of sessions is 5-8 [

24] to see the initial gains. Eye movement improvement training should be done for at least 6 to 8 weeks to see a visible impact [

24]. After 6–12 training sessions, for instance, a considerable improvement in saccadic latency (or response time) was noted [

17]. As a result, both training groups in our study received adequate training duration and frequency. However, in our study, four weeks is the bare minimum to show early improvement but not long enough to see meaningful improvements in saccadic parameters. In order to guarantee improvements, longer training is required.

On the first visit, all participants demonstrated a larger and faster initial saccade to the right than to the left, both for small and large amplitude saccades, but no such difference was seen in the vertical directions. Even after eye movement training, the horizontal asymmetry persisted, albeit in a reduced size. According to certain research [

26], asymmetry in horizontal saccades is connected to hand dominance; in the right-handed group, the saccadic latencies for the rightward saccade were considerably shorter than those for the leftward saccade, and no asymmetry was noticed in the left-handed group. We can neither confirm nor deny this statement since there were only two left-handed participants in our study. Therefore, the predominance of right-handed participants in our study might be the cause of the asymmetry in the horizontal saccadic response. The most recent research [

26] shows that horizontal saccadic asymmetry could be due to naso-temporal differences in some participants and eye dominance in other participants. We can only look at eye dominance since we had no facial asymmetry measurements. Twenty-five percents of our participants had left-eye dominance (assessed by the Dolman test). No association between eye dominance and saccadic response asymmetry for amplitude and mean velocity, neither in the horizontal nor vertical directions, was found by the mixed model ANOVA (P > 0.05). Additional studies are required to better explain such asymmetries in saccadic response.

Another intriguing finding was regarding saccadic response difference in presented sports disciplines. Usually, there is only one sports discipline presented in the studies [

7,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. In Latvia, sports vision training is a young and emerging optometric field. Due to the low response rate, it was challenging to recruit volunteers for the study. This explains why there was such a wide range of sporting disciplines (see

Table 3). The largest group presented team sports, where eye movements, especially saccades, are crucial to view teammates and a moving item (such as a ball or hockey puck). Small group of participants were in a shooting discipline. Athletes whose attention is downward during sports activity (hockey, floorball) showed larger downward saccades (only for 6° stimuli), but shooters who must react rapidly to shooting targets (half of shooters were professional military persons) showed quicker upward saccades (only for 6° stimuli). Athletes who played basketball, volleyball, and handball showed no discernible difference. Such an observation has not been made in earlier investigations. We can only presume that the initial vertical saccade has something to do with the requirements of the activity. To support this assertion, bigger research with more participants would be helpful.

There was statistically significant variation in clinical findings in each group during all study periods. Some changes cannot be considered clinically significant because they did not follow any logical clinical pattern. For example, there was myopic shift only in the right eye for participants in Group 2 (2E) but not in the left eye. There were no changes in uncorrected visual acuity. Thus, eye movement training cannot explain why there were no changes in the other eye. The only clinically logical change was in convergence and phoria in Group 3E, where the near point of convergence improved and an esophoric shift was observed for near phoria, that means exophoria decreased. That demonstrates convergence improvement at near fixation. However, the participants already had normal values of convergence on their pre-training visit. In most participants, the observed variations were in a range of corresponding measurement errors and could be considered systematic errors of the measurements or variations in repeated measurements [

27,

28]. For good repeatability, the measurements must be taken under the same conditions [

27]. However, in our study, the daytime varied for initial and follow-up visits (adapting to the time when the participant could arrive), as well as the visual function, which assessment was performed by three optometrists. Even if the techniques applied were the same, we noticed slight variability in the data even due to the optometrist factor. The range of exercises used was not initially intended to improve clinically evaluable visual functions. Based on the observed fluctuations in visual function, we cannot claim that these changes are due to eye movement exercises.

5. Conclusions

To conclude, the EYE ROLL device can be successfully used as a substitute training tool for saccadic enhancements. Following four weeks of home-based training with at least one 13-minute training session each day, the EYE ROLL device can enhance the symmetry of horizontal saccadic movements. The results are comparable to those of manual eye movement training. It is unavoidable that continued usage of eye movement training might have a greater effect on the saccadic response.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.S. and A:K..; methodology: A.S. and A.K.; formal analysis: A.S, A.K., A.G., J.B., A.P.; investigation: A.K.., L.P., A.G., J.B., M.M., S.S., A.S.; writing—original draft preparation: A.S. and A.G.; writing—validation, review and editing: D.D.G., A.K; visualization: L.G., A.G.; supervision: A.S.; project administration: A.S.; funding acquisition: A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was conducted as the contract study (Contract Study on the Application Methodology Development of a New Preventive Eye Muscle Training and Strengthening Device) ordered by the Ltd EYE ROLL and funded by the European Regional Development Fund Project No. 1.1.1.1/20/A/038 (Research and Application Methodology Development of a New Preventive Eye Muscle Training and Strengthening Device EYE ROLL).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All study procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committees. The Life and Medical Sciences Research Ethics Committee of the University of Latvia granted approval for the study, ensuring compliance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments or equivalent ethical guidelines. Prior to their involvement, all participants and their legal guardian (only in the case of children’s participation) provided written informed consent.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Di Russo F, Pitzalis S, Spinelli D. Fixation stability and saccadic latency in élite shooters. Vision Res 2003, 43(17): 1837-1845. [CrossRef]

- Kishita Y, Ueda H, Kashino M. Eye and head movements of elite baseball players in real batting. Front Sports Act Living 2020, 2: 3:1-12. [CrossRef]

- Kato T. Using “Enzan No Metsuke” (Gazing at the Far Mountain) as a visual search strategy in Kendo. Front Sports Act Living 2020, 2: 40:1-10. [CrossRef]

- Revien L, Gabor M. Sports Vision: Dr. Revien’s Eye Exercises for Athletes. Workman Publishing, New York, 1981.

- Revien L. Eyerobics (videotape). Great Neck, Visual Skills Inc., New York, 1987.

- Vickers JN. Visual control when aiming at a far target. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform 1996, 22: 342-354. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed MF. Efficiency of the program of visual training on some visual skills and visual perceptual skills and their relationship to performance level synchronized swimming juniors. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2010, 5: 2082-2088. [CrossRef]

- Miles CAL, Vine SJ, Wood G, Vickers JN, Wilson MR. Quiet eye training improves throw and catch performance in children. Psychol Sport Exerc 2014, 15(5): 511-515. [CrossRef]

- Abernethy B, Wood JM. Do generalized visual training programmes for sport really work? An experimental investigation. J Sports Sci 2001, 19(3): 203-222. [CrossRef]

- Adolphe RM, Vickers JN, Laplante G. The effects of training visual attention on gaze behaviour and accuracy: A pilot study. Int J Sports Vis 1997, 4(1): 28-33.

- Harle KS, Vickers JN. Training Quiet eye improves accuracy in the basketball free throw. Sport Psychol 2001, 15(3): 289-305. [CrossRef]

- Vine JS, Wilson MR. The influence of quiet eye training and pressure on attention and visuo-motor control. Acta Psychol 2011, 136(3): 340-346. [CrossRef]

- Wood G, Wilson MR. Quiet-eye training for soccer penalty kicks. Cogn Process 2011 12: 257-266. [CrossRef]

- Causer J, Holmes PS, Williams AM. Quiet eye training in a visuomotor control task. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011, 43(6): 1042-1049. [CrossRef]

- Neugebauer J, Baker J, Schorer J. Looking to learn better – training of perception-specific focus of attention influences Quiet Eye duration but not throwing accuracy in darts. Front Sports Act Living 2020, 2: 79:1-9. [CrossRef]

- Santamaria L, Story I. The effect of training on horizontal saccades and smooth pursuit eye movements. Aust Orthop J 2004, 38: 9-15.

- Bibi R, Edelman JA. The influence of motor training on human express saccade production. J Neurophysiol 2009, 102: 3101–3110. [CrossRef]

- Jóhannesson Ó, Edelman JA, Sigurþórsson BD, Kristjánsson Á. Effects of saccade training on express saccade proportions, saccade latencies, and peak velocities: an investigation of nasal/temporal differences. Exp Brain Res 2018, 236: 1251–1262. [CrossRef]

- Scheiman M, Wick B. Clinical management of binocular vision, 4th eds. Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2014.

- Hutton S B. Eye tracking methodology. In: Klein C, Ettinger U (ed) Eye movement research: An introduction to its scientific foundation and applications (Studies in neuroscience, psychology and behavioral economics), 1st edn. Springer, pp 287-316, 2019.

- Lix L M, Keselman J C, Keselman H J. Consequences of assumption violations revisited: a quantitative review of alternatives to the oneway analysis of variance ‘‘F’’ test. Rev Educ Res 1996, 66(4): 579-619. [CrossRef]

- Maples WC, Atchley J, Ficklin T. Northeastern State University College of Optometry’s oculomotor norms. J Behav Optom 1992, 3(6): 143-150.

- Lee T L, Yeung M K, Sze S L, Chan A S. Computerized eye-tracking Training improves the saccadic eye movements of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Brain Sci 2020, 10(12): 1016. [CrossRef]

- Press LJ. Applied concepts in vision therapy. Optometric Extension Program Foundation, Inc., 2013.

- Hutton JT, Palet J. Lateral saccadic latencies and handedness. Neuropsychologia 1986, 24(3): 449-451. [CrossRef]

- Vergilino-Perez D, Fayel A, Lemoine C, Senot P, Vergne J, Dore-Mazars K. Are there any left-right asymmetries in saccade parameters? Examination of latency, gain, and peak velocity. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012, 53: 3340-3348. [CrossRef]

- Hamed M M, Mario C B, Ali Y A, Reza S M. Accommodative amplitude using the minus lens at different near distances. Indian J Ophthalmol 2017, 65(3): 223-227. [CrossRef]

- Svede A, Batare A, Krumina G. The effect of visual fatigue on clinical evaluation of vergence. Percept 2015, 44(S1): 299-299.

Figure 1.

Example of a saccadic stimulus presentation sequence. The experiment started with a cross that was demonstrated for 2 seconds. Each saccadic stimulus was presented for two seconds, and then the fixation returned to the central cross.

Figure 1.

Example of a saccadic stimulus presentation sequence. The experiment started with a cross that was demonstrated for 2 seconds. Each saccadic stimulus was presented for two seconds, and then the fixation returned to the central cross.

Figure 2.

The prototype of the EYE ROLL device used in the study for Group 3 (3E): (1) USB socket; (2) control button to pause the exercise; (3) projection screen amplitude adjustment handle; (4) velocity adjustment element.

Figure 2.

The prototype of the EYE ROLL device used in the study for Group 3 (3E): (1) USB socket; (2) control button to pause the exercise; (3) projection screen amplitude adjustment handle; (4) velocity adjustment element.

Figure 3.

Horizontal and vertical saccade parameters for Group 1 on Visit 1 and Visit 2. (A) Amplitude, (B) Velocity, (C) Duration, (D) Peak velocity.

Figure 3.

Horizontal and vertical saccade parameters for Group 1 on Visit 1 and Visit 2. (A) Amplitude, (B) Velocity, (C) Duration, (D) Peak velocity.

Figure 4.

Horizontal and vertical saccade amplitude before and after eye movement training in extended training groups.

Figure 4.

Horizontal and vertical saccade amplitude before and after eye movement training in extended training groups.

Figure 5.

Horizontal and vertical saccadic velocity before and after eye movement training in extended training groups.

Figure 5.

Horizontal and vertical saccadic velocity before and after eye movement training in extended training groups.

Figure 6.

Horizontal and vertical saccadic duration before and after eye movement training in extended training groups.

Figure 6.

Horizontal and vertical saccadic duration before and after eye movement training in extended training groups.

Figure 7.

Horizontal and vertical saccadic peak velocity before and after eye movement training in extended training groups.

Figure 7.

Horizontal and vertical saccadic peak velocity before and after eye movement training in extended training groups.

Table 1.

Number of participants and their represented sports disciplines on the first, second (a 4-week period), and third (an 8-week period) visits.

Table 1.

Number of participants and their represented sports disciplines on the first, second (a 4-week period), and third (an 8-week period) visits.

| Sport disciplines |

First visit

N = 67

|

After 4 weeks

N = 51

|

After 8 weeks

N = 37

|

| Basketball |

14 |

8 |

4 |

| Volleyball |

18 |

16 |

13 |

| Handball |

9 |

6 (4 goalkeepers) |

3 (3 goalkeepers) |

| Floorball |

14 |

11 (5 goalkeepers) |

10 (5 goalkeepers) |

| Hockey |

4 |

4 (2 goalkeepers) |

3 (2 goalkeepers) |

| Football |

2 |

0 |

0 |

| Shooting |

6 |

6 |

4 |

Table 2.

Number of participants and their represented sports disciplines on the first, second (a 4-week period), and third (an 8-week period) visits.

Table 2.

Number of participants and their represented sports disciplines on the first, second (a 4-week period), and third (an 8-week period) visits.

| Research group |

After 4 weeks

N = 51

|

After 8 weeks

N = 37

|

| Only Group 1 |

11 |

1* |

| Basketball |

4 |

|

| Volleyball |

3 |

|

| Floorball |

2 |

1 |

| Shooting |

1 |

|

| Group 1/Group 2 |

4 |

4 |

| Basketball |

2 |

2 |

| Floorball |

1 |

1 |

| Shooting |

1 |

1 |

| Group 2/Group 1 |

13 |

11 |

| Basketball |

1 |

1 |

| Volleyball |

3 |

3 |

| Floorball |

4 |

4 |

| Hockey |

2 |

1 |

| Shooting |

3 |

2 |

| Group 1/Group 3 |

17 |

17 |

| Basketball |

1 |

1 |

| Volleyball |

10 |

10 |

| Floorball |

4 |

4 |

| Hockey |

1 |

1 |

| Shooting |

1 |

1 |

| Group 3/Group 1 |

6 |

4 |

| Handball |

5 |

3 |

| Hockey |

1 |

1 |

Table 3.

Number of participants and their represented sports disciplines on the first, second (a 4-week period), and third (an 8-week period) visits.

Table 3.

Number of participants and their represented sports disciplines on the first, second (a 4-week period), and third (an 8-week period) visits.

| No |

Exercise |

Group 2 (2E) |

Group 3 (3E) |

| 1 |

Horizontal saccades |

Black horizontally displaced numbered dots on two white pages (A3). Placing pages next to each other, dots made 28°, 19°, and 8° amplitude stimuli for saccades (if a participant was at 1 m distance). The participant changed fixation sequentially and quickly from left to right and back, going through all amplitudes and naming numbers. The duration of the exercise was 1 minute. |

Started with the largest horizontal amplitude and decreased up to the smallest one with regular steps (largest amplitude/5). The dot was demonstrated for 500 ms, starting from the left side. Each amplitude was repeated twice. The exercise was repeated three times. |

| 2 |

Vertical saccades |

Black vertically displaced numbered dots on two white pages (A3). Placing pages one below each other, dots made 28°, 19°, and 8° amplitude stimuli for saccades (if a participant was at 1 m distance). The participant changed fixation sequentially and quickly from up to down and back, going through all amplitudes and naming numbers. The duration of the exercise was 1 minute. |

Started with the largest vertical amplitude and decreased up to the smallest one with regular steps (largest amplitude/5). The dot was demonstrated for 500 ms, starting from the upper part. Each amplitude was repeated twice. The exercise was repeated three times. |

| 3 |

Diagonal saccades |

One white A3-size page with five squares (positioned in a star shape) with 4x4 symbols (capital letters and numbers). The distance between squares was 12-17° if a participant was at 1 m distance. The participant changed fixation sequentially and quickly, following the star shape and reading one symbol in squares. The duration of the exercise was 1 minute.

|

Started with the largest amplitude. The dot was demonstrated on the left side for 500 ms. Then, the dot disappeared and appeared on the right side. During the exercise, the dot followed a star shape. The exercise was repeated three times with the largest, medium, and smallest amplitudes. |

| 4 |

Saccades in different directions |

One white A3-size page with randomly positioned black numbers (with a distance of 2.5°-11° from the centre if a participant was standing at 1 m distance) with a black cross in the centre. The participant changed fixation sequentially and quickly from the centre to any symbol and back to the centre. The duration of the exercise was 1 minute. |

The dot was demonstrated in the centre of the surface for 500 ms. Then, the dot appeared for 500 ms randomly at any of 16 programmed positions 25° or 12.5° from the centre and reappeared in the central position afterwards. |

| 5 |

Horizontal smooth pursuit in one direction |

|

The dot appeared on the left side for 500 ms and started to move to the right with constant velocity (20°/s) making the largest amplitude. At the end, the dot stopped for 500 ms and disappeared, reappearing on the left side again. The movement was repeated five times. After a 1-second break, the movement was repeated, with the dot moving from right to left. After a 1.5-second break, the exercise was repeated with the dot moving with increased velocity: 30°/s and 40°/s. |

| 6 |

Vertical smooth pursuit in one direction |

|

The dot appeared on the upper side for 500 ms and started to move to down with constant velocity (20°/s) making the largest amplitude. At the end, the dot stopped for 500 ms and disappeared, reappearing on the upper part again. The movement was repeated five times. After a 1-second break, the movement was repeated, with the dot moving vertically up. After a 1.5-second break, the exercise was repeated with the dot moving with increased velocity: 30°/s and 40°/s. |

| 7 |

Horizontal smooth pursuit in both direction |

The participant held a laser pointer and drew horizontal lines on the wall. He/she started to follow the moving laser point with the eyes at a velocity that was most suitable for the eyes, gradually increasing the velocity. The duration of the exercise was 1 minute. |

Started with the largest horizontal amplitude and decreased up to the smallest one with regular steps (largest amplitude/5). The dot was demonstrated for 500 ms on the left side and started to move to the right with constant velocity (20°/s) making the largest amplitude. Each amplitude was repeated twice. The exercise was repeated three times, with the dot moving with increased velocity: 30°/s and 40°/s on each repetition. |

| 8 |

Vertical smooth pursuit in both direction |

The participant held a laser pointer and drew vertical lines on the wall. He/she started to follow the moving laser point with the eyes at a velocity that was most suitable for the eyes, gradually increasing the velocity. The duration of the exercise was 1 minute. |

Started with the largest vertical amplitude and decreased up to the smallest one with regular steps (largest amplitude/5). The dot was demonstrated for 500 ms on the upper side and started to move down with constant velocity (20°/s) making the largest amplitude. Each amplitude was repeated twice. The exercise was repeated three times, with the dot moving with increased velocity: 30°/s and 40°/s on each repetition. |

| 9 |

Diagonal smooth pursuit |

The participant held a laser pointer and drew a star on the wall. He/she started to follow the moving laser point with the eyes at a velocity that was most suitable for the eyes, gradually increasing the velocity. The duration of the exercise was 1 minute. |

Started with the largest amplitude. The dot was demonstrated for 500 ms on the left side and starts to move to the right with stationary velocity (20°/s), making the largest amplitude. The direction of motion changed following a star shape with a constant amplitude. The exercise was repeated three times, with the dot moving with increased velocity: 30°/s and 40°/s on each repetition. |

| 10 |

Smooth pursuit in different directions |

The participant held a laser pointer and drew any forms on the wall. He/she started to follow the moving laser point with the eyes at a velocity that was most suitable for the eyes, gradually increasing the velocity. The duration of the exercise was 1 minute. |

The dot was demonstrated in the centre position for 500 ms. Then, the dot started to move in random directions and amplitudes. Duration of the exercise was 1 minute. The exercise was repeated three times, with the dot moving with increased velocity: 30°/s and 40°/s on each repetition. |

| Recommended duration |

15 min (with self-regulated short breaks changing the exercise) |

15 min (with self-regulated short breaks by pressing the stop button) |

Table 4.

Visual function results of 51 participants at Visit 1 and Visit 2.

Table 4.

Visual function results of 51 participants at Visit 1 and Visit 2.

| Visual function |

Group 1 (N = 32) |

Group 2 (N = 13) |

Group 3 (N = 6) |

| Visit 1 |

Visit 2 |

Visit 1 |

Visit 2 |

Visit 1 |

Visit 2 |

| VA (OU) F (LogMAR) |

-0.07 (0.49) |

-0.10 (0.40) |

-0.14 (0.48) |

-0.13 (0.55) |

-0.04 (0.33) |

-0.04 (0.29) |

| SE (RE) (D) |

-0.25 (0.97) |

-0.25 (0.97) |

0.07 (1.47) |

-0.07 (1.57)* |

0.00

(0.38) |

0.13

(0.63) |

| SE (LE) (D) |

-0.38 (1.19) |

-0.38 (1.19) |

-0.19 (1.26) |

-0.19 (1.44) |

0.00 (0.45) |

0.00 (0.63) |

| Phoria F (Δ) |

0.0 (1.9) |

1.0 (2.8)* |

-1.0 ± 2.6 |

-0.9 ± 2.6 |

0.0 (2.0) |

1.0 (2.8) |

| Phoria N (Δ) |

0.0 (4.0) |

-1.0 (5.5) |

-5.0 (9.0) |

-7.0 (9.0) |

0.0 (4.0) |

0.0 (4.5) |

| NPC (cm) |

4.5 (0.5) |

4.5 (0.5)* |

5.0 (2.3) |

4.5 (1.5) |

5.0 (2.5) |

5.0 (1.0) |

| NFR F (Δ) |

8 (4) |

8 (4) |

8 (2) |

8 (4) |

8 (4) |

8 (3) |

| PFR F (Δ) |

35 (0) |

25 (10) *** |

35 (3) |

25 (17)

**

|

35 (0) |

25 (15) |

| NFR N (Δ) |

12 ± 6 |

12 ± 5 |

13 ± 5 |

14 ± 7 |

12 (6) |

12 (9) |

| PFR N (Δ) |

30 (17) |

25 (11) |

33 (13) |

35 (16) |

16 (21) |

35 (13) |

| NRA (D) |

2.25 (0.50) |

2.25 (0.44) |

2.21 ± 0.40 |

2.23 ± 0.42 |

2.25 (0.75) |

2.50 (0.88) |

| PRA (D) |

-3.13 ± 1.80 |

-2.99 ± 1.56 |

-3.56 ± 1.78 |

-3.50 ± 1.58 |

-4.00 (2.38) |

-2.75 (2.50) |

| AA (RE) (D) |

9 (3) |

11 (3)* |

9 (7) |

11 (5) |

9 (4) |

12 (7)* |

| AA (LE) (D) |

11 ± 4 |

11 ± 3 |

10 (7) |

14 (6) |

10 (5) |

13 (6)* |

| BAF (c/min) |

6 (10) |

7 (11) |

2 (11) |

3 (12) |

0 (12) |

9 (14) |

Table 5.

Visual function results of participants involved in vision training for four weeks throughout an 8-week period.

Table 5.

Visual function results of participants involved in vision training for four weeks throughout an 8-week period.

| Visual function |

Group 2 (N = 17) |

Group 3 (N = 23) |

| Pre-training |

Post-training |

Pre-training |

Post-training |

| VA (OU) F (LogMAR) |

-0.14 (0.49) |

-0.14 (0.55) |

-0.08 (0.50) |

-0.16 (0.48) |

| SE (RE) (D) |

0.13 (1.44) |

0.13 (1.32)* |

0.00 (1.00) |

0.00 (1.25) |

| SE (LE) (D) |

0.00 (1.44) |

-0.13 (1.44) |

0.00 (1.13) |

0.00 (1.38) |

| Phoria F (Δ) |

0.0 (3.5) |

0.0 (3.0) |

1.0 (2.0) |

1.0 (2.0) |

| Phoria N (Δ) |

-4.0 (8.0) |

-6.0 (10.0) |

-1.0 (4.0) |

0.0 (4.0)** |

| NPC (cm) |

4.5 (1.5) |

4.5 (1.5) |

5.0 (0.5) |

4.5 (0.5)* |

| NFR F (Δ) |

8 (2) |

8 (2) |

8 (2) |

8 (2) |

| PFR F (Δ) |

35 (8) |

25 (16)* |

30 (15) |

25 (15) |

| NFR N (Δ) |

13 ± 4 |

14 ± 7 |

14 ± 5 |

13 ± 6 |

| PFR N (Δ) |

30 (15) |

35 (18) |

25 (24) |

30 (20) |

| NRA (D) |

2.00 (0.50) |

2.25 (0.50) |

2.25 (0.50) |

2.25 (0.25) |

| PRA (D) |

-3.33 ± 1.90 |

-3.25 ± 2.03 |

-3.50 (2.75) |

-3.25 (2.25) |

| AA (RE) (D) |

10 (8) |

11 (5) |

10 ± 3 |

11 ± 3 |

| AA (LE) (D) |

10 (8) |

13 (4) |

11 ± 3 |

12 ± 3 |

| DR (LE) (D) |

0.75 (0.25) |

0.75 (0.50) |

0.75 (0.25) |

0.75 (0.00) |

| BAF (c/min) |

4 (11) |

7 (10) |

7 (12) |

9 (13) |

Table 6.

Horizontal and vertical saccade parameters on the first visit for all participants.

Table 6.

Horizontal and vertical saccade parameters on the first visit for all participants.

| Discipline |

Horizontal |

Vertical |

| 10° right |

10° left |

5° right |

5° left |

6°

up |

6° down |

3°

up |

3° down |

| Amplitude |

| Discipline 1 (N =15) |

9.6 (1) |

9.9 (0.8) |

5.0 ± 0.4 |

4.8 ± 0.3 |

4.9 ± 0.8 |

5.5 ± 0.7 |

2.6 ± 0.5 |

2.9 ± 0.6 |

Discipline 2

(N = 29) |

9.9 ± 0.6 |

9.5 ± 0.8 |

5.1 ± 0.4 |

4.8 ± 0.5 |

5.0 ± 0.7 |

5.0 ± 0.8 |

2.5 ± 0.4 |

2.5 (0.6) |

Discipline 3

(N = 6) |

9.9 ± 0.5 |

9.8 ± 0.2 |

5.3 ± 0.2 |

4.9 ± 0.3 |

5.5 ± 0.7 |

4.9 ± 0.5 |

2.8 ± 0.6 |

2.4 ± 0.3 |

| All (N = 50) |

9.8 ± 0.6 |

9.7 (0.9) |

5.1 ± 0.4 |

4.8 (0.5) |

5.0 ± 0.8 |

5.1 ± 0.8 |

2.6 ± 0.5 |

2.6 (0.6) |

| Velocity |

| Discipline 1 (N = 15) |

169 ± 13 |

169 (15) |

116 ± 7 |

113 ± 7 |

116 ± 13 |

122 ± 14 |

79 ±

10 |

83 ±

9 |

Discipline 2

(N = 29) |

175 ± 16 |

167 (15) |

121 ± 9 |

114 ± 10 |

114 ± 14 |

113 ± 12 |

80 ±

9 |

77 ± 11 |

Discipline 3

(N = 6) |

176 ± 7 |

173 ± 9 |

124 ±6 |

120 (7) |

127 ± 15 |

111 ± 8 |

83 ± 11 |

79 ±

7 |

| All (N = 50) |

173 ± 14 |

168 (16) |

120 ± 8 |

116 (12) |

116 ± 14 |

116 ± 13 |

80 ±

9 |

79 (11) |

| Duration |

| Discipline 1 (N =15) |

57.0 ± 5.0 |

57.6 ± 3.4 |

42.8 ± 2.3 |

42.7 ± 2.6 |

42.0 ± 4.9 |

44.7 ± 5.7 |

32.8 ± 6.8 |

34.1 ± 4.5 |

Discipline 2

(N = 29) |

56.5 ± 4.0 |

57.4 ± 4.4 |

42.1 ± 3.0 |

42.2 ± 1.9 |

43.2 ± 4.9 |

43.5 ± 4.8 |

30.9 ± 2.6 |

31.4 ± 4.0 |

Discipline 3

(N = 6) |

56.2 ± 2.6 |

56.8 ± 3.0 |

42.3 ± 1.4 |

40.7 ± 1.9 |

43.7 ± 1.9 |

44.4 ± 3.4 |

32.7 ± 3.6 |

29.0 ± 1.4 |

| All (N = 50) |

56.6 ± 4.1 |

57.4 ± 3.9 |

42.3 ± 2.7 |

42.2 ± 2.2 |

42.9 ± 4.6 |

44.0 ± 4.9 |

31.7 ± 4.4 |

31.9 ± 4.2 |

| Peak velocity |

| Discipline 1 (N =15) |

313 ± 52 |

299 ±34 |

220 ± 36 |

206 ± 31 |

198 ± 48 |

248 ± 96 |

134 ± 40 |

140 ± 29 |

Discipline 2

(N = 29) |

332 ± 47 |

308 ± 41 |

231 ± 33 |

216 ± 32 |

215 ± 52 |

214 ± 41 |

131 ± 23 |

140 ± 54 |

Discipline 3

(N = 6) |

330 ±37 |

315 ± 36 |

239 ± 24 |

223 ± 34 |

231 ± 51 |

182 ± 32 |

144 ± 37 |

112 ± 13 |

| All (N = 50) |

326 ± 47 |

306 ± 38 |

229 ± 33 |

214 ± 31 |

212 ± 50 |

220 ± 65 |

133 ± 31 |

136 ± 45 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).