1. Introduction

Oculomotor control is fundamental for postural stability and the precise execution of movement, particularly in sports disciplines that demand high coordination, such as rhythmic gymnastics. Eye movements allow athletes to gather relevant visual information from the most critical areas of the visual scene, facilitating optimal motor control and faster decision-making [

1]. It has been shown that expert athletes display more efficient visual search patterns than less skilled performers (characterized by fewer but longer fixations] reflecting a more effective integration between perception and motor action [

1].

Gaze stabilization is maintained through vestibular reflexes, visual feedback, and cervical motion, while its orientation depends on rapid saccades and smooth pursuits [

2]. Furthermore, coordination between ocular, head, and body movements determines visual behavior patterns during complex motor actions [

3]. In acrobatic sports, several studies have demonstrated that visual stabilization is essential for spatial orientation during spins and rotations, as seen in trampoline and artistic gymnastics [

4,

5,

6]. These findings reinforce the notion that vision not only guides action but also optimizes motor performance under conditions of high coordinative demand.

In parallel, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful tool for modeling and predicting performance in sports sciences. ML refers to the development of systems capable of learning from experience and autonomously adapting to generate predictive analyses without explicit instructions [

7]. Its applications include sports data monitoring [

8], activity recognition [

8], injury prediction [

7,

8,

9], and the exploration of cognitive and motor differences among athletes of different competitive levels [

10]. It has also been used to estimate performance in specific disciplines such as marathon running [

11]. A recent review emphasized the transformative potential of artificial intelligence in applied sports research [

12].

This study compares visual attention patterns between rhythmic gymnasts and school-aged students using an eye-tracking system combined with machine learning algorithms. Spatiotemporal gaze metrics were analyzed to identify perceptual strategy differences between both groups and to explore the potential of these technologies for predicting visuocognitive performance. Several supervised models (SVM, k-NN, Decision Tree, Random Forest, XGBoost, and Convolutional Neural Networks) were trained and evaluated using a hold-out validation protocol (70/30).

Within this context, optometric assessments add value by enabling the analysis of visual functions that are critical for athletic performance. The prediction of specific optometric parameters through artificial intelligence further extends the scope of such studies, providing implications for both sports and clinical practice.

The aim of this study is to compare visual attention patterns between rhythmic gymnasts and school-aged students through eye-tracking and machine learning algorithms, to identify differences in perceptual strategies and assess the potential of these technologies in predicting visuocognitive performance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

The study included 299 rhythmic gymnasts and 696 primary school students. Participant selection was carried out with the authorization of the Sports Department of the Madrid City Council and the Educare Valdefuentes School. The protocol adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid, Spain (No. 21/766-E, December 20, 2021). Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of all minors.

The tests were conducted in various sports centers across Madrid (where rhythmic gymnastics clubs trained) and at a school facility. Participants were placed in a controlled environment free from external light interference, and the room was maintained under low ambient illumination to enhance the infrared sensitivity of the eye-tracking system. Each participant completed the test in approximately five minutes. These environmental conditions were standardized across all sessions to ensure experimental reproducibility for future replications.

2.2. Equipment

The DIVE system (Devices for an Integral Visual Examination) was used, equipped with a 12-inch display (visual angle: 22.11° horizontal; 14.81° vertical) and an eye-tracking module operating at 120 Hz temporal resolution. Three specific test protocols were applied:

DIVE Long Saccades Test: evaluates wide and rapid eye movements, relevant for tracking moving objects.

DIVE Short Saccades Test: assesses the accuracy of small-amplitude eye movements, essential for hand–eye coordination.

DIVE Fixation with Eye-Tracking Test: measures visual fixation stability.

2.3. Data

Gaze recordings were stored in tabular (CSV) format. The target variable was binary, while an unspecified number of predictors (denoted as p, to preserve confidentiality) were used. The header row was removed, separating the feature matrix (all columns except the last) from the label vector (last column).

2.4. Experimental Protocol

• Data partitioning: Hold-out method, with 70% for training and 30% for testing, using a fixed random seed to ensure reproducibility.

• Performance metrics: Accuracy and F1-macro, complemented by confusion matrices for each model.

• Implementation: Scikit-learn for SVM, k-NN, Decision Tree, and Random Forest; XGBoost for gradient boosting; TensorFlow/Keras for the neural network.

• Preprocessing: Standardized feature scaling was applied to the neural network, while classical models used unscaled data.

The test set remained blind throughout the entire process. Although a hold-out split was employed in this study for practical reasons, future research should incorporate stratified cross-validation to enhance the robustness of the results.

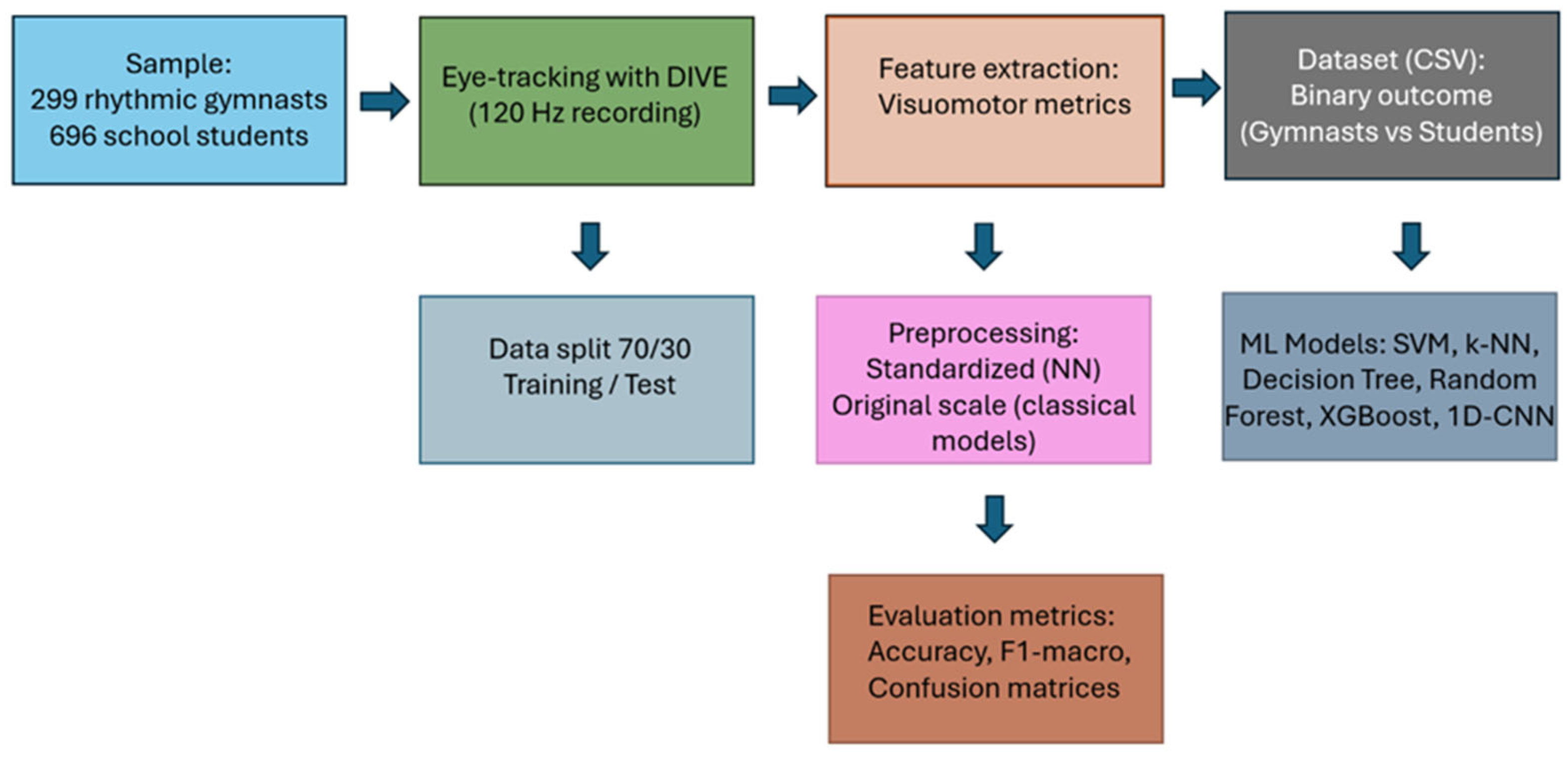

To facilitate understanding of the methodology,

Figure 1 summarizes the experimental workflow, outlining the main stages of the study: sample selection, eye-tracking recording using the DIVE system, extraction of visuomotor features, dataset preparation, training–test split, preprocessing, model implementation, and performance evaluation using the selected metrics.

2.5. Models and Parameters

The following supervised algorithms were evaluated:

SVM (SVC): Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel.

k-NN: k = 3, Euclidean distance.

Decision Tree (CART): Direct implementation of the C4.5 algorithm.

Random Forest: 100 trees.

XGBoost: Multinomial logistic loss, default parameters.

-

Neural Network (1D-CNN):

- ○

Input: Standardized features.

- ○

Convolutional blocks: 64 filters (kernel = 2) + Batch Normalization (BN) + Dropout (0.3); 32 filters (kernel = 2) + BN + Dropout (0.2).

- ○

Classifier: Flatten → Dense (128) + BN + LeakyReLU (α = 0.1) + Dropout (0.3) → Dense (64) → Dense (32) → Dense (16) → Dense (2, softmax).

- ○

Optimization: Adam optimizer, batch size = 128, 450 epochs, loss function = sparse categorical cross-entropy.

2.6. Justification of Key Decisions

Hold-out (70/30): Provides an independent estimate of generalization performance with low computational cost and allows direct comparison between models. The structured organization of the dataset prevented the use of cross-validation since classes were sequentially grouped.

F1-macro: Mitigates class imbalance by averaging F1 scores across both classes.

k-NN (k = 3): Offers a robust local inductive bias with moderate variance, serving as a non-parametric baseline.

Random Forest and XGBoost: Capture nonlinear interactions and include implicit regularization; using 100 trees is an efficient and widely accepted standard.

1D-CNN: Short convolutions detect local patterns in tabular data, while Batch Normalization and Dropout improve model stability and regularization

3. Results

The full dataset (N = 995) was randomly partitioned using a 70/30 hold-out scheme into a training set (n = 696) and a test set (n = 299), with a fixed random seed to ensure reproducibility. This split is independent of group membership (gymnasts: n = 299; students: n = 696).

| |

Age (m±sd) |

Sex (M/F) |

DLFT (logDeg2) |

DSFT (logDeg2) |

DSETT |

| Gymnastic |

11.72±3.85 |

4/324 |

0.00±0.00 |

-0.37±0.36 |

0.97±0.06 |

| Primarty School Students |

8.47±1.74 |

328/317 |

0.80±0.51 |

-0.23±0.43 |

0.97±0.07 |

Overall, XGBoost was the best-performing classifier, achieving an accuracy of 94.6% and an F1-macro score of 0.945, followed closely by Random Forest, which obtained 94.0% accuracy and an F1-macro of 0.937. The one-dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (1D-CNN) achieved intermediate performance (accuracy = 89.3%; F1-macro = 0.888), while the individual Decision Tree produced acceptable results (accuracy = 86.6%; F1-macro = 0.862).

In contrast, simpler algorithms such as SVM and k-NN exhibited lower performance, with accuracies of 77.9% and 71.9%, and F1-macro scores of 0.761 and 0.694, respectively. These results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Accuracy and F1-macro results of the models used.

Table 1.

Accuracy and F1-macro results of the models used.

| Model |

Accuracy |

F1-macro |

| SVM (RBF kernel) |

0.779 |

0.761 |

| k-NN (k = 3) |

0.719 |

0.694 |

| Decision Tree (CART) |

0.866 |

0.862 |

| Random Forest (100 trees) |

0.940 |

0.937 |

| XGBoost |

0.946 |

0.945 |

| Neural Network (1D-CNN) |

0.893 |

0.888 |

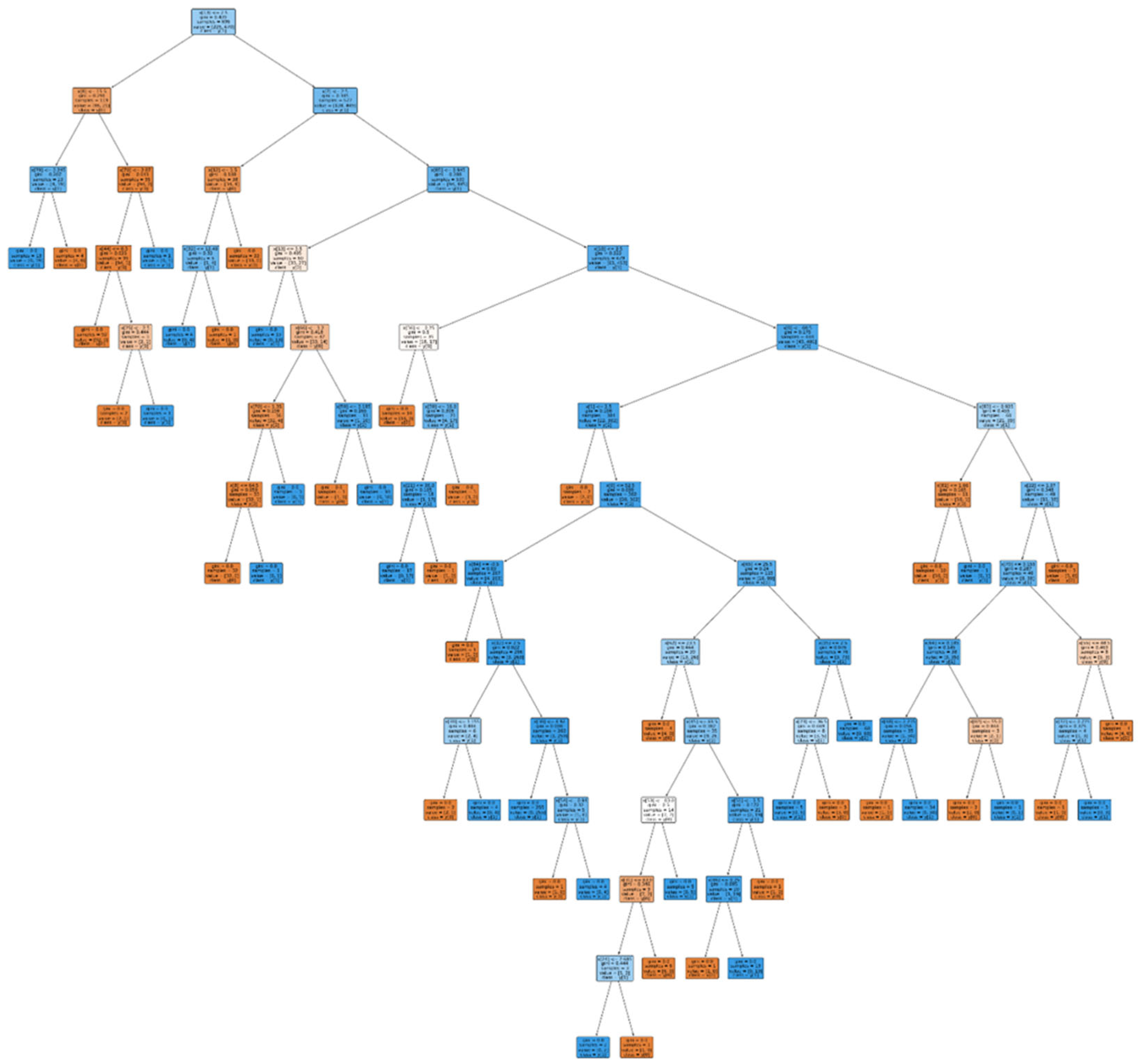

The graphical representation of the decision tree (

Figure 2) illustrates how the model segments gaze patterns based on spatiotemporal features, highlighting the relevance of specific oculomotor metrics in distinguishing between gymnasts and students. This analysis adds interpretability to the classification process by showing which variables contribute most directly to the final decision.

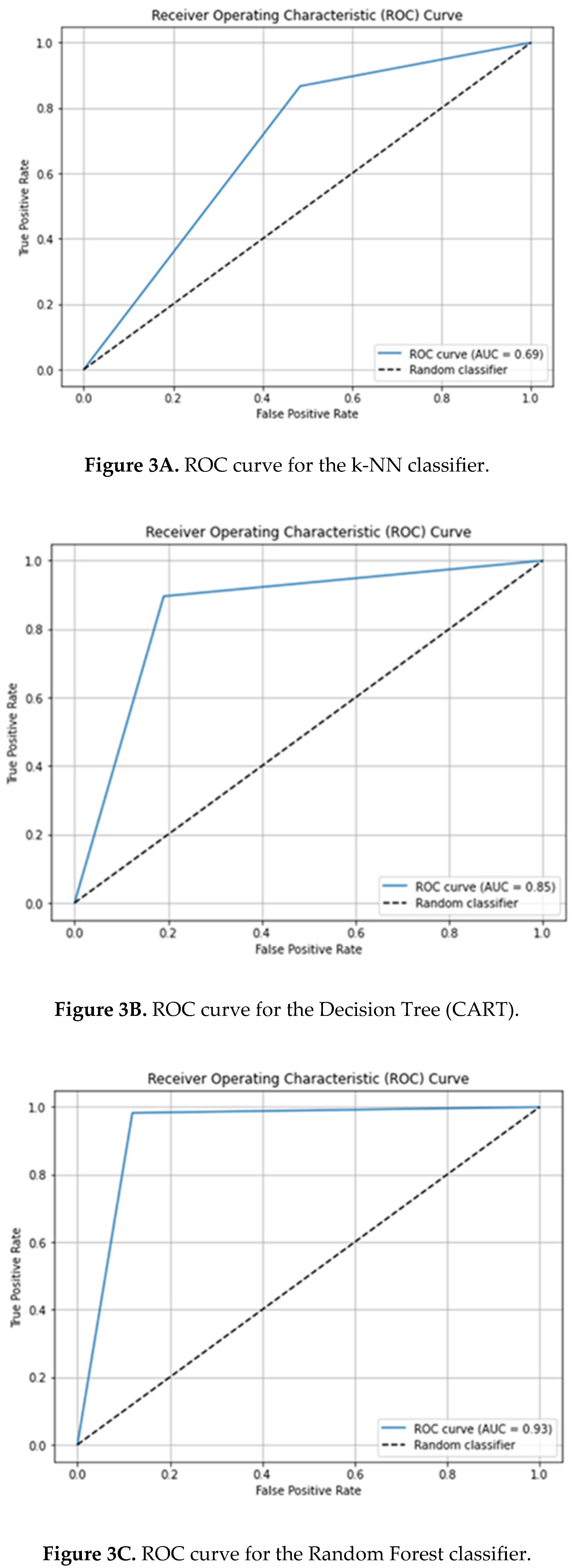

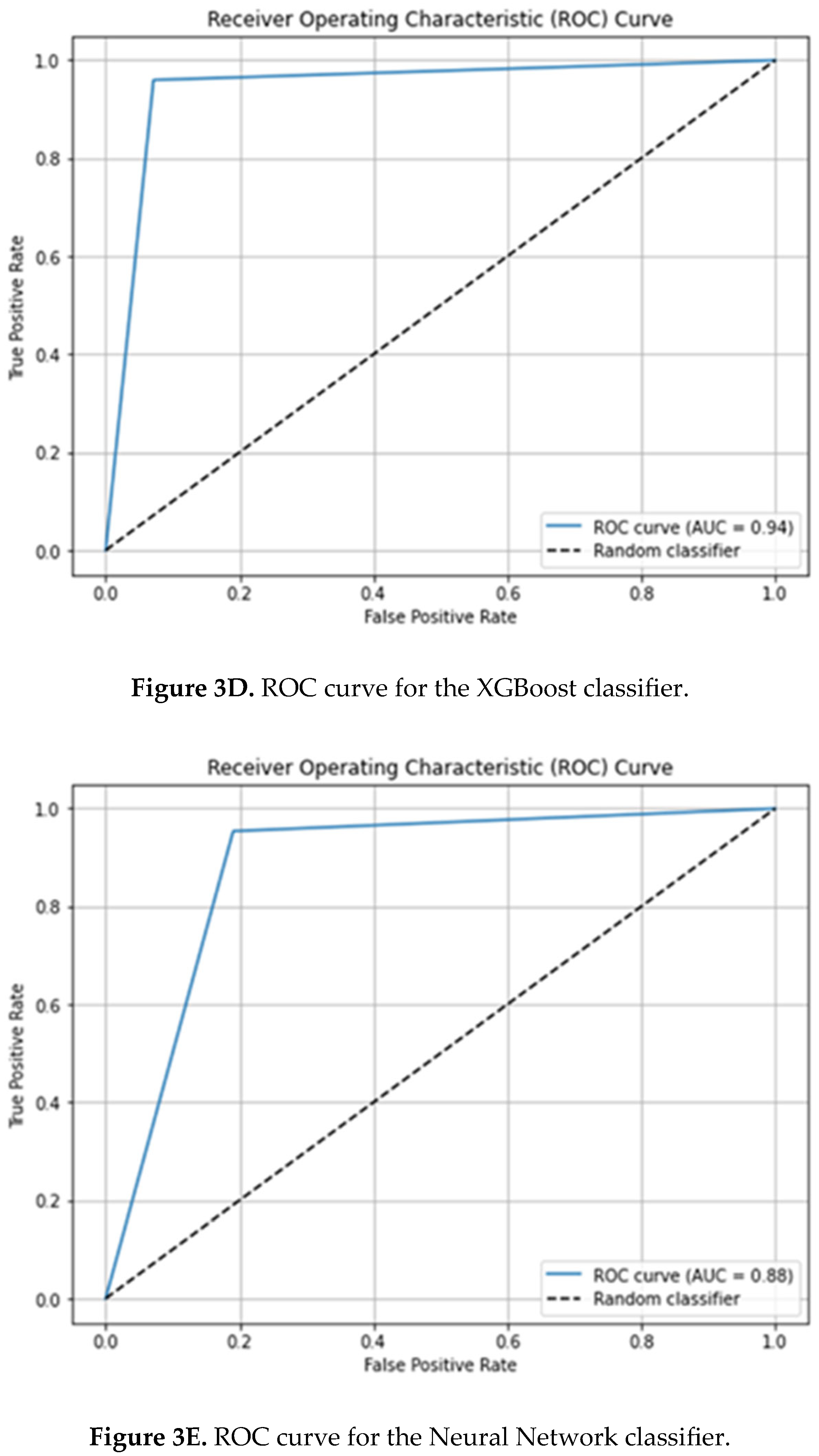

Likewise, the analysis of the ROC curves confirmed the superiority of the ensemble models. XGBoost achieved an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.94 and Random Forest an AUC of 0.93, both indicating excellent discriminative capability. The neural network also demonstrated good discrimination (AUC = 0.88), while the decision tree showed acceptable performance (AUC = 0.85). In contrast, k-NN and SVM yielded lower values (AUC = 0.69 and 0.77, respectively), consistent with the accuracy and F1-macro results previously described in

Figure 3 (A–E).

Beyond the performance indicators of the models, the analysis of oculomotor metrics revealed clear differences in visual patterns between the two groups. Rhythmic gymnasts exhibited more efficient gaze behavior, characterized by longer fixations and more precise saccadic movements, suggesting more goal-directed and stable perceptual strategies. In contrast, students displayed a more exploratory and dispersed gaze pattern, with shorter fixations and less consistent saccades, reflecting a lower degree of visuomotor control compared to the athletes.

4. Discussion

Unlike previous studies focused exclusively on either athletic or school populations, this work introduces an innovative comparative approach by simultaneously analyzing the visual attention patterns of rhythmic gymnasts and school-aged students using eye-tracking and artificial intelligence.

To the best of our knowledge, no previous research has applied this comparative methodology to both populations. Furthermore, the integration of optometric metrics and AI-based models not only provides a valuable framework for assessing sports performance but also opens the door to clinical applications such as the early detection of visual dysfunctions and the design of personalized training programs.

The results show that gymnasts exhibit longer fixations and more precise saccadic movements, suggesting more efficient and goal-directed perceptual strategies. This pattern is consistent with the findings of Natrup et al. [

4,

5] and Sato et al. [

6], who reported greater oculomotor stability during acrobatic movements. Similarly, Ramyarangsi et al. [

13] compared gymnasts, soccer players, and eSports athletes, finding that gymnasts displayed significantly longer fixation durations in response to dynamic stimuli. This supports the hypothesis that rhythmic training promotes more stable and anticipatory visual control. These adaptations reflect the interaction between vestibular control, visuomotor integration, and motor planning in elite rhythmic performance contexts, processes previously described by Cullen [

2] and von Laßberg et al. [

3].

From a computational perspective, ensemble models (XGBoost and Random Forest) achieved superior performance, with accuracy and F1-macro values close to 95%. This result aligns with recent research highlighting the robustness of these algorithms in predicting physiological and sports-related patterns [

7,

9,

12]. Reis et al. [

12] reported that gradient-boosting models such as XGBoost are particularly effective at detecting nonlinear relationships in complex biomechanical data, while Calderón-Díaz et al. [

9] demonstrated their applicability in predicting muscle injuries based on kinematic analyses. Taken together, our findings confirm the suitability of tree-based ensemble models for characterizing complex visual patterns and their potential for visuocognitive performance analysis.

The intermediate performance of the one-dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (1D-CNN) is consistent with the results obtained by Gao et al. [

14] and Lerebourg et al. [

11], who observed that deep learning models tend to overfit when trained on limited datasets. Nevertheless, its ability to capture temporal dependencies suggests considerable potential for future studies with larger samples and higher temporal resolution eye-tracking data.

Compared with the model proposed by Liu et al. [

15], which achieved an accuracy of 72.9% in predicting sports behavior using logistic regression, our XGBoost-based approach (94.6%) represents a substantial improvement. This enhancement can be attributed both to the nonlinear nature of the algorithm and to the inclusion of oculomotor variables as functional predictors.

From an applied perspective, the integration of eye-tracking and artificial intelligence not only enables the differentiation of visual strategies between groups but also facilitates the design of personalized visual training programs. Recent studies, such as those by Formenti et al. (10] and the systematic review Training Vision in Athletes to Improve Sports Performance (16], confirm that specific visual training programs can significantly enhance both perceptual–cognitive skills and motor performance across different sports disciplines.

In that review, Lochhead et al. [

16] analyzed 126 studies and observed consistent improvements in variables such as dynamic visual acuity, hand–eye coordination, selective attention, and reaction time following structured visual interventions. However, the authors emphasized the methodological heterogeneity and limited number of randomized controlled trials, highlighting the need for more standardized protocols that directly relate perceptual improvements to measurable gains in sports performance.

In this context, our findings could serve as a foundation for developing adaptive visual assessment and training systems for young athletes, integrating quantitative metrics derived from eye-tracking and predictive models based on artificial intelligence.

Furthermore, recent reviews on eye-tracking technology [

17] underline the scarcity of studies applying these methods in experimental settings that replicate real training conditions. The present work helps address these limitations by combining objective visual metrics and machine learning within an environment more representative of competitive training, thus providing a reproducible framework for future research.

Taken together, our results confirm that oculomotor control constitutes a sensitive marker of visuomotor performance and that AI-based techniques offer a reliable and objective means of analysis. This integrated approach expands the current evidence on the relationship between vision, cognition, and motor performance, with relevant implications for training optimization, clinical evaluation, and the development of adaptive human–machine interfaces.

Despite the robustness of the results, certain methodological limitations should be acknowledged. The hold-out protocol, although efficient and computationally inexpensive, may be sensitive to data partitioning, potentially affecting the stability of performance metrics. Similarly, the absence of systematic hyperparameter tuning in the SVM and k-NN models may have limited their predictive capacity compared to ensemble algorithms. Finally, although the sample size was adequate for the analyses performed, expanding the dataset and incorporating stratified cross-validation would improve the robustness and generalizability of the findings, thereby consolidating the applicability of this approach in future investigations.

5. Conclusions

The integration of eye-tracking sensors with machine learning algorithms enables precise, objective, and quantitative assessment of visuocognitive performance. Rhythmic gymnasts exhibited more goal-directed and efficient gaze patterns than school-aged students, underscoring the influence of specialized training on visual attention strategies and oculomotor control.

Among the evaluated models, XGBoost and Random Forest demonstrated high predictive capacity and stability in classifying visual patterns, whereas the one-dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (1D-CNN) requires further optimization to improve its generalization ability.

Future studies should incorporate stratified cross-validation procedures, systematic hyperparameter tuning, and larger sample sizes to enhance the robustness and reproducibility of the results. Overall, the findings of this study underscore the promise of integrating eye-tracking and artificial intelligence as valuable tools in sports sciences, cognitive assessment, and the development of adaptive human–machine interfaces.6. Patents

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.J.P.-M., R.B.-V., and J.R.T.; methodology, F.J.P.-M. and J.R.T.; software, J.R.T.; validation, F.J.P.-M., R.B.-V., and J.R.T.; formal analysis, F.J.P.-M. and R.B.-V., ; investigation, F.J.P. and R.B.-V -M., R.G.-J., C.O.-C., and G.M.-F.; resources, F.J.P.-M. and J.E.C.-S.; data curation, R.G.-J., C.O.-C., and G.M.-F.; writing—original draft preparation, F.J.P.-M.; writing—review and editing, F.J.P.-M., R.B.-V., J.E.C.-S., and J.R.T.; visualization, F.J.P.-M.; supervision, F.J.P.-M. and J.R.T.; project administration, F.J.P.-M.; funding acquisition, F.J.P.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínico San Carlos (Madrid, Spain) (protocol code 21/766-E, approval date 20 December 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the conclusions of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. Due to ethical and privacy restrictions, the data are not publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| AUC |

Area Under the Curve |

| BN |

Batch Normalization |

| CART |

Classification and Regression Tree |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| DIVE |

Devices for an Integral Visual Examination |

| F1-macro |

Macro-Averaged F1 Score |

| k-NN |

k-Nearest Neighbors |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| ROC |

Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SVM |

Support Vector Machine |

| 1D-CNN |

One-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Network |

| XGBoost |

Extreme Gradient Boosting |

| RF |

Random Forest |

| RBF |

Radial Basis Function |

| ReLU |

Rectified Linear Unit |

| BN |

Batch Normalization |

| Dropout |

Dropout Regularization Technique |

| Adam |

Adaptive Moment Estimation Optimizer |

References

- Barbieri, F.A.; Rodrigues, S.T. Editorial: The Role of Eye Movements in Sports and Active Living. Front. Sports Act. Living 2020, 2, 603206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullen, K.E. Vestibular Motor Control. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2023, 195, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Laßberg, C.; Beykirch, K.A.; Mohler, B.J.; Bülthoff, H.H. Intersegmental Eye–Head–Body Interactions during Complex Whole-Body Movements. PLoS ONE 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natrup, J.; Bramme, J.; de Lussanet, M.H.E.; Boström, K.J.; Lappe, M.; Wagner, H. Gaze Behavior of Trampoline Gymnasts during a Back Tuck Somersault. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2020, 70, 102589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natrup, J.; de Lussanet, M.H.E.; Boström, K.J.; Lappe, M.; Wagner, H. Gaze, Head, and Eye Movements during Somersaults with Full Twists. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2021, 75, 102740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, Y.; Torii, S.; Sasaki, M.; Heinen, T. Gaze-Shift Patterns during a Jump with Full Turn in Male Gymnasts. Percept. Mot. Skills 2017, 124, 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amendolara, A.; Pfister, D.; Settelmayer, M.; Shah, M.; Wu, V.; Donnelly, S.; et al. An Overview of Machine Learning Applications in Sports Injury Prediction. Cureus 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, P. System Design and Simulation for Square Dance Movement Monitoring Based on Machine Learning. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 1994046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderon-Diaz, M.; Silvestre Aguirre, R.; Vasconez, J.P.; Yanez, R.; Roby, M.; Querales, M.; et al. Explainable Machine Learning Techniques to Predict Muscle Injuries in Professional Soccer Players through Biomechanical Analysis. Sensors 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formenti, D.; Duca, M.; Trecroci, A.; Ansaldi, L.; Bonfanti, L.; Alberti, G.; et al. Perceptual Vision Training in a Non-Sport-Specific Context: Effect on Performance Skills and Cognition in Young Females. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerebourg, L.; Saboul, D.; Clemencon, M.; Coquart, J.B. Prediction of Marathon Performance Using Artificial Intelligence. Int. J. Sports Med. 2023, 44, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, F.J.J.; Alaiti, R.K.; Vallio, C.S.; Hespanhol, L. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Approaches in Sports: Concepts, Applications, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2024, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramyarangsi, P.; Bennett, S.; Nanbancha, A.; Noppongsakit, P.; Ajjimaporn, A.; et al. Eye Movements and Visual Abilities Characteristics in Gymnasts, Soccer Players, and Esports Athletes: A Comparative Study. J. Exerc. Physiol. Online 2024, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Ma, C.; Su, H.; Wang, S.; Xu, X.; Yao, J. [Research on Gait Recognition and Prediction Based on Optimized Machine Learning Algorithm]. Sheng Wu Yi Xue Gong Cheng Xue Za Zhi 2022, 39, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Hou, W.; Emolyn, I.; Liu, Y. Building a Prediction Model of College Students’ Sports Behavior Based on Machine Learning Method: Combining the Characteristics of Sports Learning Interest and Sports Autonomy. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lochhead, L.; Feng, J.; Laby, D.M.; Appelbaum, L.G. Training Vision in Athletes to Improve Sports Performance: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2024, 17, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klatt, S.; Noël, B.; Memmert, D. Eye Tracking in High-Performance Sports: Evaluation of Its Application in Expert Athletes. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Sport 2018, 17, 182–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).